Abstract

This qualitative study conducted by a community-research partnership used multiple types of data collection to examine variables relevant for LGBTQ older adults who wished to age in place in their urban Denver neighborhood. Focus groups, interviews, and a town hall meeting were used to identify barriers and supports to aging in place. Participants (N=73) primarily identified as lesbian or gay, aged 50–69, and lived with a partner. Ageism, heterosexism, and/or cisgenderism emerged as cross-cutting themes that negatively impact access to healthcare, housing, social support, home assistance and legal services. Resilience from weathering a lifetime of discrimination was identified as a strength to handle aging challenges. Recommendations for establishing an aging in place model included: establishing welcoming communities, resource centers, and increasing cultural competence of service providers. This study provides a unique contribution to understanding the psychosocial, medical, and legal barriers for successfully aging in place.

Keywords: qualitative methods, LGBTQ, aging in place, community-research partnership, older adults, Community-based participatory research

The Center for Disease Control defines aging in place as “the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level” (CDC, 2013). As we age, formal and informal support systems become increasingly important to maintain independence. Although older adults are the fastest growing segment of the US population (Hobbs, 2011) and strong advocacy organizations exist (e.g., AARP), older adults frequently face barriers when attempting to access health and social services necessary to age in place (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al 2011; Met Life, 2006). Examples of ageism are pervasive and include negative stereotypes of older adults (Masotti et al, 2006; Levy & Banaji, 2002) and under-treatment of medical conditions based on patient age (Peake, et al 2003; Kemeny et al., 2003). Variation in availability of suitable living alternatives (e.g., assisted living, long-term care) within communities amplifies the need to support older adults’ ability to live safely in their homes (Calmus, 2013; Ball et al 2004). However, limited or inaccessible services may undermine their ability to age in place (Colorado Department of Human Services, 2004; Vasunilashorn et al., 2012).

It is estimated that there are currently 2.7 million adults age 50 years or older who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) in the US (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016). This estimate is expected to double by 2060 and is likely an underestimate when considering same-sex behavior or romantic relationships among those who don’t identify as LGBTQ. Despite recent state and federal legal victories in the US (Obama Administration, 2011), lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) older adults, will still face significant challenges. LGBTQ older adults are disproportionately more likely to live alone than heterosexual seniors and are at a much higher risk for disability, poverty, homelessness, social isolation, depression, alcohol dependence, financial disparity, housing deficiencies and premature institutionalization (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al, 2011; Zelle & Arms, 2015; Espinoza, 2011; Witten, 2014; de Vries, 2014; policy institute, 2000). LGBTQ older adults are often childless or estranged from family members, setting up a scenario where older adults are the sole support of other older adults (de Vries, 2014; Family Caregiver Alliance, 2009). A focus group study identified key life areas of importance for older lesbian, gay and bisexual adults, which are similar to their straight contemporaries, including: physical health, legal rights, housing, spirituality, family, mental health, and social networks (Orel, 2004).

Lesbian, gay and bisexual adults have concerns about discrimination in care facilities, senior centers, transportation, and home care services (Stein, Beckerman, & Sherman, 2010;). One study found that 73% of LGBTQ older adults living in the community believed that discrimination exists in assisted living facilities (from both staff and residents), and 34% would hide their sexual orientation if they had to move to such a facility (Johnson et al, 2005). A survey of heterosexual residents demonstrated little awareness about the discrimination experienced by LGBTQ older adults living in the same retirement setting (Johnson, 2008).

Similarly, healthcare providers who fail to ask about sexual orientation may overlook important preventative care procedures such as HIV screening (Coon, 2007; Shankle, 2003; Cahill, South, & Spade, 2000). It is not uncommon for LGBTQ older adults to avoid accessing these services due to fear and anxiety about the treatment they will receive, even when it puts their health, safety and security at risk (Brotman, et al., 2007; MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2006). These challenges indicate a need for well-coordinated, accessible and effective support service systems that will maximize health outcomes and promote the ability to age safely at home.

Life experiences of “pre-liberation” LGBTQ older adults

The baby boomer and silent generations of LGBTQ older adults born prior to 1960,grew up during a time of pre-liberation (Brotman, Ryan, & Cormier, 2003). Pre-liberation refers to an era when homosexuality was listed as a mental health disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (through 1974) and the concept of gay civil rights was not widely recognized in the US (emerged during the Stonewall riots of 1969). The life experience of pre-liberation LGBTQ older adults has been characterized by disapproval from biological family, a lack of children, feelings of shame or internalized homophobia from discrimination experiences, and smaller social networks (Fokkema & Kuyper, 2009). This pre-liberation group is distinct because they are not well understood by general service providers for older adults (Addis et al, 2009) or by LGBTQ-specific organizations that typically cater to younger generations (Slusher, Mayer, & Dunkle, 1996). This group may be more in need of services but less likely to access those services as a result of experienced and/or anticipated discrimination from providers (Brotman et al., 2003).

Alternatively, LGBTQ older adults may have resiliencies acquired through life experiences that are related to the coming out process (Schope, 2005), where strategies for disclosing sexual orientation to friends and family and dealing with victimization may have become necessary (Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011). There is evidence of thriving and “out” LGBTQ older adults with loving partners, large social networks or “families of choice” and extensive coping skills (Genke, 2004). These skills, such as self-advocacy and resilience may empower some LGBTQ older adults in the future when they encounter aging related obstacles.

Aging in place

As the proportion of adults over the age of 65 continues to grow, the concept of “aging in place,” where older adults continue to live at home within their communities, is becoming increasingly discussed (Bookman, 2008). Successful aging in place models promote independence, include older adults in decision-making, create an environment of personal and physical safety, facilitate social support, and provide services to enhance the health and quality of life of older adults within the communities in which they live (The Jewish Federations of North America, 2013). There is evidence of physical and mental health benefits for older adults to remain in their own homes, and significant cost savings for individuals, families and the public health care system (MacLaren, Landberg & Schwartz, 2007). Assuring access to appropriate aging services without requiring relocation to age-segregated retirement communities is important to assure that all older adults are able to age safely within their existing community settings.

There are two well-known aging in place models: The Village Model and Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities (NORCs). Villages and NORCs are typically non-profit organizations with a combination of paid staff and volunteers offering a range of services which include, but are not limited to: referrals to home health agencies, social services, transportation services, assistance with household tasks, and educational activities (Accius, 2010; NORC Blueprint, 2013). Villages started in Boston, MA with the Beacon Hill Village, and today, there are upward of 93 Villages throughout the nation (Fried, 2013). Villages typically have membership costs and attract middle to upper economic class members.

NORCs are defined as the purposeful coordination and provision of health and social services in communities where older adults live that were not originally designated as a neighborhood for older adults. NORCs occur where older residents have lived in their homes over several decades and aged together, or from migrations of older adults into neighborhoods where they intend to live for the rest of their life. NORCs are a cost effective way to promote the positive health of older adults (Masotti, et al, 2006). NORCs are similar in their mission and tasks to Villages, but are more commonly located within a housing or apartment complex or within a defined neighborhood. NORCs do not typically have membership dues and usually emphasize community engagement and empowerment of older adult community members (NORC Blueprint, 2013). A NORC aging in place model may be a particularly good fit for LGBTQ older adults with its focus on enhancing both formal and informal community connections, community engagement and empowerment.

Purpose

The purpose of this investigation was to assess the perceptions of urban dwelling LGBTQ older adults on aging in place to inform the development and implementation of an aging in place model. This study a) examined the barriers to aging in place experienced by LGBTQ older adults, b) described the strengths and potential unique competencies of the aging LGBTQ community to address barriers, and c) identified LGBTQ older adult recommendations for aging in place program design and implementation.

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted as part of a larger community-research partnership effort called SUSTAIN (Seniors Using Supports To Age In Neighborhoods), established in 2009 with the ultimate goal of developing and adapting an aging in place model in a Denver-metropolitan neighborhood that is home to a high concentration of LGBTQ individuals. SUSTAIN partners include representatives from: social service agencies; local LGBTQ community members; the county Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Commission; a regional affiliate of Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Elders (SAGE); the LGBTQ community center; a church leader; an area agency on aging; a non-profit healthcare and research organization; and university researchers specializing in aging. The SUSTAIN partnership jointly developed the research design and partners were involved in all aspects of the research process including interview and focus group recruitment, question development, interviewing, analysis, dissemination back to the community, and manuscript preparation. All study related procedures were approved by the Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Recruitment

Study participants were a convenience sample who was identified and recruited during community events (e.g., 2010 Pridefest in Denver), existing LGBTQ community (advocacy and social) groups, and SUSTAIN partner networks. Data collection was iterative as new information became available about sources of recruitment or new topics of interest were identified to explore with future participants. Study staff used email and follow-up phone calls to invite potential participants to attend a focus group or interview. Snowball sampling assisted with identifying more isolated and under-served individuals in the community through SUSTAIN partners with positions in local social service agencies. Due to concerns from the institutional review board regarding discomfort of individuals being asked to disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity in a group setting, personal identifying information was not collected from focus group or town hall participants, therefore some individuals possibly participated in more than one data collection activity.

Prior to specific data collection activities, several steps were taken by the research team to increase trustworthiness and study validity. Interviewers were trained using an immersion technique which included their observing and participating in older adult activities (e.g., discussion groups) which were held at the local LGBTQ community center. The purpose of these observations was to build a community-research partnership, to gain trust within the community, and immerse researchers in the experience of being a LGBTQ older adult.

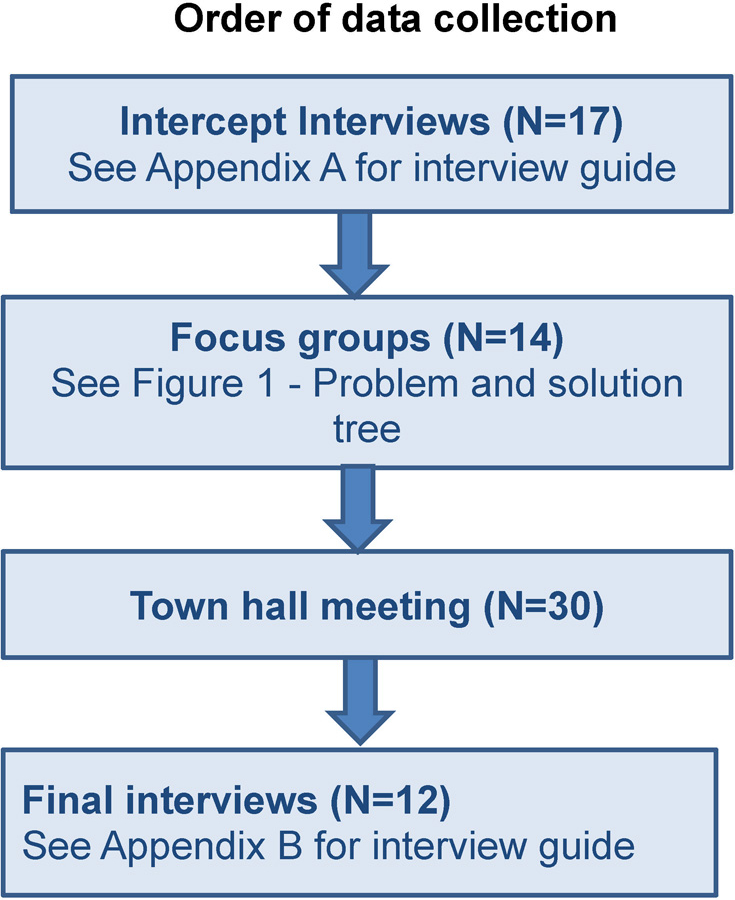

Data Collection (See Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Order of data collection

Intercept Interviews.

Intercept interviews lasting 10–15 minutes, were conducted first by SUSTAIN partners at a local 2010 Pridefest festival to identify key concepts of interest for older LGBTQ adults about aging in place (see Appendix A).

Focus groups.

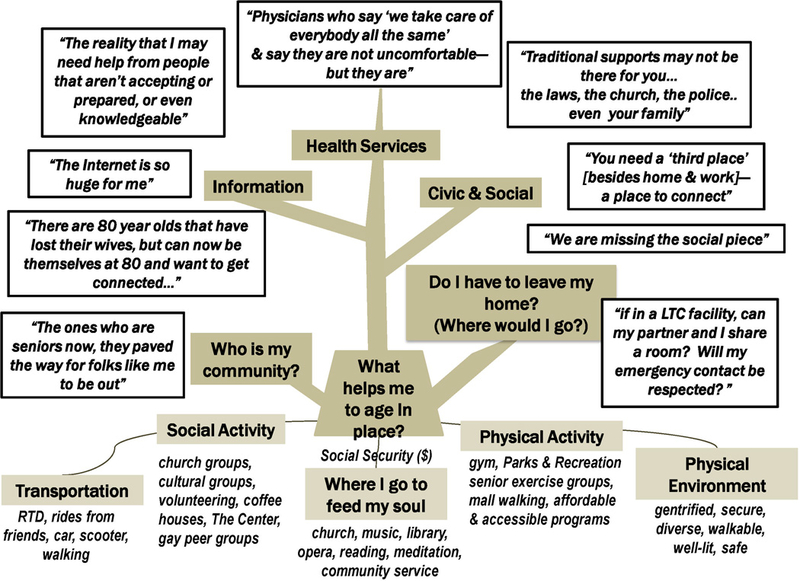

Focus groups were conducted in 2010 with two community groups, one identifying as a gay social group and the other as a lesbian advocacy group. A problem and solution tree (Figure 2) methodology was used to facilitate discussion and aid participants in identifying multi-level influences on aging in place while simultaneously increasing their awareness about this issue (Snowdon, Schultz, & Swinburn, 2008; King & King, 2010). To assure the method would stimulate useful discussion in focus groups with community members, the tree was first piloted by a research assistant facilitator with the SUSTAIN partners to formalize the broad problems and sub-problems that would make up the tree branches. Subsequent focus groups worked collaboratively to create their own problem and solution tree that clarified the root causes of issues identified by the SUSTAIN partners and to develop possible interventions to optimize aging in place.

Figure 2.

Problem-solution tree. Example of a completed problem-solution tree used for focus groups.

Town hall.

After analyzing the feedback from the focus groups and intercept interviews using a problem and solution tree that compiled the themes and solutions, summary results were presented at a town hall meeting, held in conjunction with a regional SAGE conference in October, 2010. The purpose of the town hall was to validate the interpretation of the initial results, collect additional data and discuss ideas for next steps. The process of member checking, or validating the research staff interpretation of qualitative interpretations from data collected, was used to identify if town hall participants agreed with the findings (Saldana, 2009). In addition to supporting the results, participants shared their own experiences and perspectives about aging in place, and these notes were added to the qualitative database and included in our final analyses.

Final Interviews.

In depth, 60 minute interviews were completed to further explore the key concepts identified during intercept interviews, focus groups, and the town hall meeting (see Appendix B). These interviews were used to establish a deeper understanding of the impact of barriers and facilitators identified through the focus groups, town hall, and intercept interviews, to better understand individual experiences.

Analysis

The focus groups and final interviews were audio-taped, while the town hall and intercept interviews used hand-written notes and flipcharts to document participant comments. Hand-written notes were taken during all events, and problem and solution trees were completed on flipcharts. Final interviews were transcribed, focus group problem and solution trees were compiled to make one large visual, and town hall poster board notes were assembled generating one list of participant feedback. Notes, visuals and transcripts were analyzed and coded for key themes related to major topics that reflected the project’s primary areas of interest. Coding was performed by two research assistants and verified iteratively with the SUSTAIN partners.

Two cycles of coding took place separately by the research assistants and were compared at the conclusion of analysis. The first cycle coding was conducted on compiled focus group, town hall and all interview data using an a priori approach of evaluation coding. Evaluation coding is a technique commonly used for program evaluations or community needs assessment where codes are structured by the questions that initiated the evaluation process (Saldana, 2009). Evaluation codes included the strengths of the LGBTQ older adult community as well as the gaps and barriers related to social and health services. A second cycle of coding used process codes (referred to as “action codes” in some qualitative texts), which involved bottom-up coding of observed actions (i.e. reading, attending, fighting) and conceptual action (i.e. negotiating, struggling, adapting) taken by participants. Process coding is particularly appropriate for qualitative studies examining emotions and actions of a group encountering a challenge with a goal of overcoming the problem (Saldana, 2009). Process codes were transformed into more meaningful large categories organized within the evaluation codes of strengths, gaps, and barriers (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996). Coding comparisons of the process codes resulted in the same categorical results for both research assistants. The partnership engaged in peer-debriefing of these themes which assisted with summarization and categorization of findings.

Results

Participants

Seventy-three individuals participated in at least one data collection event: intercept surveys (n=17); focus groups (n=14); town hall meeting (n=30); final interview (n=12). Individual-level demographics were not available for the focus groups and town hall participants due to institutional review board restrictions. Group facilitator observations identified the focus group participants primarily as gay males in their 70’s and lesbian females in their 60’s. Self-reported demographics were provided for intercept and final interviews (Table 1). Due to the majority of participants identifying as cisgender gay or lesbian individuals, we are limited in our ability to make inferences about the applicability of our findings to the bisexual or transgendered communities.1

Table 1. Demographics of Individual Interviewees (n=29).

| Who do you live with? | Live alone |

13 |

| Live with partner |

13 |

|

| Live with family | 3 | |

| How do you identify? | Lesbian |

16 |

| *Participants could choose more than one category, thus total exceeds 29 |

Bisexual |

2 |

| Straight |

1 |

|

| Gay |

9 |

|

| Transgender |

2 |

|

| Queer |

1 |

|

| Female |

20 |

|

| Male |

9 |

|

| Pansexual | 1 | |

| Age | 40–49 |

1 |

| 50–59 |

12 |

|

| 60–69 |

13 |

|

| 70–79 | 3 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (n=10) | White |

8 |

| Hispanic |

1 |

|

| African American | 1 | |

| Residence | Years at current address (mean±SD; n=18) |

18±14 |

| Residence type: house |

19 |

|

| Residence type: apartment/condo/townhome | 10 | |

Barriers to Aging in place

Identified barriers to aging in place for LGBTQ older adults included discrimination, stigmatization, and gaps in social and health services such as healthcare, legal services and rights, housing, and home assistance.

Discrimination and stigmatization.

While discrimination was evident in every data collection activity when discussed historically, current experiences and perceptions varied. Some felt well accepted in their neighborhood, while others still strongly experienced the impact of discrimination from the community. A lesbian woman reports distrust from recent experiences:

I don’t trust the police, they call all the time for money [donation] and I tell them ‘you never once help me, we been robbed twice, no three times. They cited us for feeding the squirrels, but no help when we were robbed.

This woman went on to describe a story of her partner who was verbally and physically attacked by a neighbor shouting homophobic comments and they did not contact the police because they did not trust them.

Participants reported that they are stigmatized for their age, sexual and gender identities. Fears about aging were expressed, particularly the risk of increased isolation (especially for those who were non-partnered), social and health care needs, support and caregiving needs, poverty, and depression. A lesbian woman describes her fear of needing help as she ages:

Just talking about how you are different and challenges about being different in the sense of being just GLBT, and then to talk about your aging, which you know, some people may embrace that and some people may fear that. And then to talk about the reality, that I may need, sooner or later, I may need help from people that aren’t accepting or prepared, or even knowledgeable.

Participants felt that their aging situation was more complex in regards to social and health service needs than non-LGBTQ older adults. For example, a transgender woman expressed fear about cisgenderism in the context of the need for help with personal hygiene and activities of daily living from a health care worker who may be uncomfortable attending to someone who has physical differences due to aging and gender affirming surgery.

Social support.

Participants used the term family to describe a system of partners, neighbors and/or friends, as opposed to traditional concepts of parents, children and siblings. Participants described that they cannot frequently rely on traditional family supports and may not benefit from traditional forms of caregiving. One example of a more pro-active planning approach was self-described by a socially isolated participant who lacked any social support. He developed an action plan with a human resource manager to do a welfare check in the occasion he missed work; otherwise no one would know that something might have happened. In addition to family supports, religious and spiritual supports were often lacking. While some churches were found to be accepting of LGBTQ older adults, many were not, enforcing reluctance to seek spiritual/religious guidance or support. A gay man compares the experience of a traditional aging experience in a family with children to a LGBTQ older adult:

The other piece with elders is that the things that aren’t there traditionally isn’t the same: your kids, you may not be connected to your kids if you had kids, you may not have kids, that generation often does not have kids. The church isn’t there for you. Blood relatives may not be there for you, the institute; the laws of the state may not be there for you. And then, even like, police and all of that may not be there for you.

Healthcare.

Participants indicated that social and health service agencies continue to rely on models of practice that exclude sexual orientation, gender identity and family context, and may fail to address the specific needs of LGBTQ older adults. A gay man described how his long-time health care provider may not be screening for health risks related to him being a gay male such as HIV.

I don’t know, maybe they did [ask about his sexual identity] and it’s just such a non-important thing… he [doctor] isn’t stupid, but I don’t feel the urge to say anything, I probably will just plain old mention it at some point, it isn’t anything that came up.

Others described experiences with physicians that are aware of their sexual or gender identity but not comfortable with it: “Physicians say ‘we take care of everybody all the same’. Some of them are uncomfortable, some of them say they are not uncomfortable but they are. I mean you can just tell.”

Legal services and rights.

Participants explained that political and legal rights of sexual minorities are limited, especially in terms of marriage. At the time of the study in 2010, Colorado did not recognize same-sex marriage and had not enacted civil unions. The US Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined marriage as a union between one man and one woman, was still upheld in 2010. However, the Colorado Designated Beneficiary Agreement Act of 2009, which granted rights for partners to make funeral arrangements, receive death benefits, and inherit property without a will was fully enacted. Interviewers observed that participants lacked knowledge about their legal rights under Colorado’s Designated Beneficiary Agreement, some of which had previously been denied. With shifting legislation, long-term care and estate planning is a challenge, particularly as new legislation is enacted. Having access to knowledgeable legal and financial advisors was noted as a key for older LGBTQ adults to stay current with the ever changing status of their legal rights.

Housing.

Although safe and affordable housing was identified as a major barrier to aging in place, many participants were reluctant to leave their residence or neighborhood. This hesitancy was due to a strong connection to their community and fear of living in a nursing home or assisted living facility. Those who felt unwelcome in their community tended to be more isolated and expressed a strong desire to connect with other LGBTQ older adults. Two gay male partners discussed increased isolation after negative experiences with other residents in their low-income housing apartment:

When I get home, I stay home, I don’t want to run into any of these people, I don’t want to be trapped on the elevator with anyone…you wouldn’t want anybody to know that you were gay in this building. You would be in trouble; there would be consequences.

Despite reluctance to leave neighborhoods or homes, many participants recognized that it would be necessary at some point. When that time came, communal living, co-housing or assisted living situations that were exclusively for LGBTQ older adults were desired, although some were open to the inclusion of straight allies. One particularly hesitant lesbian woman stated, “If I had to go to assisted living, having a partner would make it ok.”

Home assistance.

Participants expressed reservations about allowing care providers into their home, a lesbian woman participant expressed: “I will do my utmost to not have to access any services for as long as possible.” She was reluctant to allow in-home assistance due to a prior experience of homophobic physical violence toward her partner from neighbors. An interview participant who was a gay man mentioned reluctance to ask for any assistance with basic maintenance from their apartment manager because of past discriminatory experience where the manager said: “Well you are lucky you have a place to live.” Furthermore, when a lesbian woman was asked about her feelings regarding someone else helping care for her partner, she said: “It would be dire, but I would probably end up doing double duty, not that I don’t trust people, but I would probably keep it in-house, do it myself.” However, there were participants who were very happy in their neighborhoods, had friendly relationships with neighbors, and were well connected to social service organizations that provided home assistance. The local HIV/AIDS organization had assisted some participants to acquire housing within the same apartment building, and also provided home assistance services with groceries and cleaning.

Strengths of the LGBTQ Aging Community

Community strengths identified included: enthusiasm, activism, resiliency, and available resources. Participants were enthusiastic about efforts to support LGBTQ aging in place, and excited about the potential to contribute to community efforts that support successful aging. The LGBTQ community was viewed as a generation of individuals that “paved the way” for progress toward equality: “The ones who are seniors now, are the ones who paved the way for younger folks to be able to be out, to at least have some of the safeguards and security to be more open about sexual orientation.” Participants were proud of their social justice accomplishments and wanted to maintain the momentum. Resiliency was a theme, with participants indicating that if a LGBTQ individual could live a long life, they could do anything. “The fact that they have made it to a certain age basically tells you they have coping skills that they have the ability to get through life in one piece. If you have lived to this age, somehow you must have been doing something right.”

Participant’s Recommendations for Aging in place Model

Recommendations in support of an aging in place model for the local community included: a resource center, advocates, a buddy program, competent providers, and establishment of a welcoming community.

Resource center.

Participants desired a resource that was both aging and LGBTQ specific, such as the SAGE program. Participants emphasized the importance of a trusted source of information and education for LGBTQ seniors; a source that would be updated with information and explanation of changing LGBTQ rights and policies and how the changes impact LGBTQ seniors. At this time, SAGE was just coming on the scene, with the newly affiliated SAGE of the Rocky Mountains. At the town hall and focus groups, it was suggested that the local LGBTQ community center would be an excellent place to house LGBTQ aging resources.

A few participants from the final interviews indicated a reluctance to attend any events or show up at the local LGBTQ community center due to discomfort with being “out” or discomfort with the younger LGBTQ population. Those that were less comfortable going to the LGBTQ community center mentioned that they would like to receive printed materials or use web resources, which highlights the importance of maintaining a searchable library that includes up-to-date, senior-specific information about LGBTQ rights on the SAGE of the Rockies website, with potential to request information from a live person or join an online discussion on a relevant topic

Advocacy Efforts.

Focus groups and the town hall participants recognized a need for organized advocacy efforts for older adults. Many felt that LGBTQ older adults were natural activists who had made it possible for youth to be safer living “out” today. Participants recommended increased advocacy among traditional aging organizations such as the local Commission on Aging, Area Agencies on Aging, and other advocacy organizations to heighten awareness of LGBTQ older adults as a group with unique needs.

Buddy programs.

A few participants spoke highly of the local HIV/AIDS advocacy organization where they received home assistance and established social relationships with community volunteers from their buddy program. One man described his “buddy” as a good friend who went out to lunch with him every Saturday and then took him grocery shopping. Buddy programs were said to be ways to connect with younger LGBTQ and straight allies, and a way to provide both social support and home assistance. Participants’ familiarity and comfort with the buddy program suggests this model could provide a beneficial support mechanism for LGBTQ seniors experiencing social isolation and home-health attention. LGBTQ-Competent providers. Participants described providers who were aware of and comfortable with LGBTQ orientation and asked informed questions pertinent to LGBTQ health risks as competent and welcoming. Some participants were very open with their providers, sought care from specific providers who were openly LGBTQ themselves or LGBTQ affirming. Those with LGBTQ-competent providers feared possible changes to their health insurance plan (i.e. from commercial insurance plan through an employer to a federal Medicare program) as they aged that may require a change of provider.

Establish a welcoming community.

There was a strong theme throughout the interviews for a desire to connect with other LGBTQ older adults in a community setting. But there was variability in the sample between those who felt connected currently to a welcoming community and those who did not. For different reasons, some mentioned that they did not feel comfortable with the younger LGBTQ community (lack of appreciation of the older generation’s fight for civil liberties and social change) or the older straight community (lack of acceptance). Interestingly, some interviewees said they were more comfortable playing a mentoring or educational role with youth.

During the town hall member checking session the idea of a “3rd place” was raised as a physical place to connect with a welcoming community after people retire from their jobs. A participant explained that the 1st place is your home, the 2nd place is your job, and the 3rd place is where LGBTQ older adults could connect with a community to maintain social connections. An example of a 3rd place for heterosexual older adults would be a senior center; however, LGBTQ older adults were skeptical of being welcomed there. The LGBTQ community center was discussed as an ideal 3rd place to gather, but some participants from the interviews who were less comfortable being “out,” expressed reluctance towards involvement at a LGBTQ community center. Other 3rd places discussed included a local welcoming church or neighborhood coffee shop.

While a majority of participants in focus groups, interviews and the town hall expressed a desire to connect with other LGBTQ older adults, a minority of interviewees were less enthusiastic about such engagement. This viewpoint could be due to fears about being “out” in their community due to past or current experiences with discrimination or possibly internalized homophobia. One woman indicated that she had been invited to participate in events at the local LGBTQ community center, but just did not feel comfortable attending. Another man, who lived in very close proximity to the local LGBTQ center, described that he had not had any connections with the gay community for many years and fears involvement now from possible retaliation if his neighbors found out. It is important to mention this finding as community members who are less “out” and comfortable in the LGBTQ community have a point of view that is harder to reach through research studies or community projects. However, as more isolated individuals, they may benefit the most from community aging in place initiatives.

Discussion

This study provides an important contribution to extend our knowledge about the unique strengths and needs of LGBTQ older adults when it comes to being able to safely age in place. We offer an exploratory investigation of key barriers, strengths and recommendations that could inform the adaptation of a NORC or Village Model to support LGBTQ older adults. While we focused on one metropolitan area, the barriers, strengths and recommendations identified are consistent with similar investigations of aging LGBTQ adults (Van Wagenen et al, 2013; Croghan et al , 2014; Orel, 2014; Brennan-Ing et al, 2014), indicating that our findings may be broadly applied to other locations.

Barriers, strengths, and recommendations for successful aging in place

The support categories that LGBTQ older adults identified as necessary for successful aging in place were similar to those typically identified by heterosexual older adults including access to healthcare, legal services, finances, transportation, and home assistance related to functional limitations. Unique and heightened barriers specific to being LGBTQ were consistently acknowledged, particularly increased isolation and fears about accessing home assistance. Without traditional family supports from children, the aging population of LGBTQ older adults, even those with full social networks, will be providing support to their own aging cohort, perhaps limiting the support available and increasing stress among aging caregivers. Lesbian, bisexual and transgender women are more likely to be caregivers compared to gay, bisexual or transgender men (Croghan et al, 2014). Furthermore, recent survey data have shown that gay cisgender and transgender men are more likely to live alone and be childless; thus, the probability of living alone increases as age increases (Croghan et al, 2014)

Our findings also highlighted trepidation about future housing options with regard to assisted living facilities that may be run by religious institutions or may not accept a same sex partner. It was suggested that an aging in place model could expand the buddy programs to increase the connection between the older and younger LGBTQ generations to provide social support and home assistance.

As pervasive homophobic and heterosexist beliefs have been found to provoke fear and anxiety in the LGBTQ aging population (Coon, 2007), our results support that discrimination, including ageism, heterosexism and cisgenderism are barriers to accessing social and health services. Even in situations where an older adult has the ability to access a service, concerns about ignorant, uncompassionate, and inadequate care are still present. Providers are often seen as unprepared and lacking necessary training to manage the complex realities faced by LGBTQ elders. Professional education to raise awareness of unique social and health issues, skill building on how to ask about these issues as a part of routine care, and knowledge of available resources are needed (Portz et al, 2014).

Our study also identified several important strengths that recurred as themes among our LGBTQ respondents including enthusiasm, activism, and resiliency. Consistent with our findings, resiliency achieved from living in a heterosexist culture was identified by Orel et al (2014) as a key strength for negotiating aging challenges. These characteristics could be harnessed when implementing an aging in place model that requires participation, partnership and empowerment. Several specific clinics, agencies, centers, and other neighborhood features were identified by participants as welcoming places that could partner with the LGBTQ community to improve community health and social outcomes. We are encouraged that these diverse agencies could eventually be affiliated with a LGBTQ affirming aging in place organization in the neighborhood.

Older adults are a diverse group in regard to ability, class, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity. It cannot be assumed that as a community ages, members will need the same services or supports. It is important to investigate the specific needs and wishes of a community before implementing service models. Because social workers hold positions in social and health agencies, they should be aware of the unique situation of LGBTQ older adults, such as their increased risk of isolation and fears about seeking services, to guide care and improve individual and community outcomes.

Limitations

Our findings were consistent with previous literature, suggesting that the experiences of our study participants would be similar in other US metropolitan areas. We are unable to report experiences from suburban and rural communities, who may experience increased discrimination compared to this sample of urban participants from a community with a high concentration of LGBTQ residents. Our study was particularly hampered by a lack of representation from the bisexual, intersex or transgender community, lack of ethnic/racial diversity and we do not know the demographic information for focus group or town hall participants. Other limitations include our use of convenience sampling from a single community and small numbers of participants.

Conclusions

Our study goes beyond identifying barriers, given our use of a problem and solution tree to identify root causes and potential solutions. Based on our findings, an aging in place NORC model would be recommended for the LGBTQ community and should include: 1) community-based advocates within the LGBTQ community who can identify isolated individuals and connect them to services; 2) a centralized knowledge resource center that is housed within a welcoming community setting and contains information that LGBTQ adults can easily access; 3) a safe “3rd place” where LGBTQ older adults can gather for social interaction and information; and 4) efforts to educate service providers to increase awareness and acknowledgement that older individuals may have experienced a long history of oppression and may therefore be wary of disclosing their sexual orientation, despite efforts to create welcoming, safe environments.

In the US, there has been a strong political movement recently with significant gains in legal rights with the United States Supreme Court decision ruling the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) unconstitutional and the federal legalization of same-sex marriage. While this important policy shift is a victory, it remains important to acknowledge the lag of cultural change that follows in light of generations of discrimination. This novel political climate presents new challenges and difficulties that LGBTQ older adults will need to navigate in the coming years, but aging in place organizations could help educate and inform the aging LGBTQ community of complex policies. While resilience and coping skills developed at younger ages can continue to be leveraged in later years, LGBTQ older adults are vulnerable to the unique challenges presented by the intersection of ageism, cisgenderism and/or heterosexism. Future research needs to focus on developing capacity for providing LGBTQ older adults with culturally competent, welcoming services and social supports in environments of their choosing.

Acknowledgments:

We want to wholeheartedly thank all LGBTQ community members who offered their insightful input as participants for this investigation. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the support of additional SUSTAIN community partners: Debra Angell, Kay Gilchrist, Carlos Martinez, Rene Hickman, William Lundgren, and Shari Wilkins. Finally, we would like to dedicate this work to the late Cathy Grimm. Cathy was a tireless advocate and leader in the development of aging in place models as the Director of Senior Solutions at Jewish Family Service. Cathy was a founding partner of SUSTAIN who was integral in finding and engaging community members across multiple disciplines.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000154. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Appendix A. Intercept Interviews

I’d like to start out by asking you a few things about where you currently live.

What neighborhood do you live in now? (Where do you live now?)

What type of residence do you live in? (home, apartment, senior living community, assisted living, etc)

About how long have you lived at your current address?

Does anyone live with you? If so whom? (partner, spouse, children, parent, other relatives, non-relatives, caregiver)

Now, and as you grow older, what will be the most important things that will help you remain in your home or neighborhood if you want? (affordability, access to transportation, access to health services, neighbors, friends, family, safety, easy to walk around, internet, companionship, culture, place of worship, laws, social services, home aides/caregiver etc.)

In general, for elder GLBT people, what do you think are the most important things they need to live independently, where they choose? (affordability, access to transportation, access to health services, neighbors, friends, family, safety, easy to walk around, internet, companionship, culture, place of worship, laws, social services, home aides/caregiver, etc.)

What are your main information sources when it comes to medical care, social services, finances, safety? (the Center, my doctor, my family, the internet, hair dresser, social group, community group, etc.)

Appendix B. Interview guide – In depth follow up interviews

I’d like to start out by asking you a few things about where you currently live.

What neighborhood do you live in now? (Where do you live now?)

What type of residence do you live in? (home, apartment, senior living community, assisted living, etc)

About how long have you lived at your current address?

Does anyone live with you? If so whom? (partner, spouse, children, parent, other relatives, non-relatives, caregiver)

Who helps you if you need help? (when you are sick, need transportation, need help around the house/yard)?

Now, and as you grow older, what will be the most important things that will help you remain in your home or neighborhood if you want? (affordability, access to transportation, access to health services, neighbors, friends, family, safety, easy to walk around, internet, companionship, culture, place of worship, laws, social services, home aides/caregiver etc.)

What are your main information sources when it comes to medical care, social services, finances, safety? (The Center, my doctor, my family, the internet, hair dresser, social group, community group, etc.)

Thinking specifically about health and health care, where do you get your care now? What about as you age? Have you discussed your orientation or gender-identity with your provider?

Are there any aspects about your culture or race/ethnicity that make it easier or harder for you to remain in your home and neighborhood now if you want? As you age?

Are there any aspects about your culture or race/ethnicity that make it easier or harder for you to get assistance from service providers, health care providers, and others in your neighborhood/local community?

In general, for elder GLBT people, what do you think are the most important things they need to live independently, where they choose? (affordability, access to transportation, access to health services, neighbors, friends, family, safety, easy to walk around, internet, companionship, culture, place of worship, laws, social services, home aides/caregiver, etc.)

Anything else you would like to add?

Footnotes

A note on terminology

The terminology used to describe the LGBTQ community is constantly evolving. Many terms used by older adults to describe their gender identity or sexual orientation are different than terminology used by younger generations or in academic literature. A recent survey of older and younger LGBTQ community members found that older females tend to use the term “gay” to describe themselves, while younger females described themselves as “lesbian” (de Vries, 2014). Older men tended to describe themselves as “homosexual,” while younger men use “gay” or “queer.” Our study was limited to only a few individuals who identified themselves as transgender, none identified as intersex, and no participants used the term heterosexism or cisgender to explain their experience. However, the research team later assigned the term “cisgenderism” to describe discrimination encountered by a transgender participant from another person who was unaccepting of their non-cisgender behavior (i.e. an appearance that is not homogenously female or male).

References

- Accius JC (2010). AAARP – Village Model Washington DC: AARP Public Policy Institute, Retrieved from: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/liv-com/fs177-village.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Addis S, Davies M, Greene G, MacBride Stewart S, & Shepherd M (2009). The health, social care and housing needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender older people: A review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 17, 647–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ (2004). Managing decline in assisted living: the key to aging in place. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, 59(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookman A (2008). Innovative models of Aging in Place: Transforming our communities for an aging population. Community Work and Family, 11, 419–438. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Ing M, Seidel L, Larson B, Karpiak SE (2014). Social Care Networks and Older LGBT Adults: Challenges for the Future. Journal of Homosexuality, 61: 21–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, Collins S, Chamberland L, Cormier R, Julien D, & Richard B (2007). Coming out to care: Caregivers of gay and lesbian seniors in Canada. The Gerontologist, 47(4), 490–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, & Cormier R (2003). The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian older adults and their families in Canada. The Gerontologist, 43, 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmus D (2013). The Long-Term Care Financing Crisis. Center for Policy Innovation Discussion Paper #7 on Health Care Retrieve from: http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2013/02/the-long-term-care-financing-crisis [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, South K, Spade J. Outing age: Public policy issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender elders. The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Foundation. 2000. Retrieved from http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/OutingAge.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Healthy Places Terminology Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/terminology.htm

- Coffey A & Atkinson P (1996). Making sense of qualitative data: Complementary research strategies Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Coon DW (2007). Exploring interventions for LGBTQ caregivers. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 18(3):109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Croghan CF, Moone RP, Olson AM (2014). Friends, Family and Caregiving Among Midlife and Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adults. Journal of Homosexuality, 61: 79–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries B (2014). LG(BT) persons in the second half of life: The intersectional influences of stigma and cohort. LGBT Health 1(1) 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza R (2011). The diverse elders coalition and LGBT aging: Connecting communities, issues, and resources in a historic moment. Public Policy & Aging Report, 21(3), 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema T & Kuyper L (2009). The relation between social embeddedness and loneliness among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the Netherlands. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 264–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Emlet CA, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Hoy-Ellis, & Petry H (2011). The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Institute for Multigenerational Health Retrieved from http://caringandaging.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Full-Report-FINAL-11-16-11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Goldsen J, Shiu C, & Emlet CA (2016). Addressing Social, Economic, and Health Disparities of LGBT Older Adults & Best Practices in Data Collection. LGBT+ National Aging Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA: Retrieved from: http://caringandaging.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/2016-Disparities-Factsheet-Final-Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fried C (2013). Village People: Community Networks Help Boomers ‘Age in Place.’ Bloomberg January 24, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-24/village-people-community-networks-help-boomers-age-in-place-.html [Google Scholar]

- Genke J (2004). Resistance and resilience: The untold story of gay men aging with chronic illnesses. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 17, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM (2010). Outing age: Public policy issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender elders. The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Foundation Retrieved from http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/outingage_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich T (2009). Neighbors Helping Neighbors: A Qualitative Study of Villages Operating in the District of Columbia Fact Sheet 177, March 2010 Washington, DC: AARP Knowledge Management; . Retrieved from: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/dcvillages.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs FB (2011). Popluation Profile of the United States: The Older adultly Population. US Census Bureau

- HUD: US Department of Housing and Urban Development (2015). Fair Housing http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/LGBT_Housing_Discrimination

- Johnson MJ (2008). The potential impact of discrimination fears of older gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender individuals living in small-to moderate-sized cities on long-term health care. Journal of homosexuality, 54, 325–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MJ, Jackson NC, Arnette JK, & Koffman SD (2005). Gay and lesbian perceptions of discrimination in retirement care facilities. Journal of Homosexuality, 49, 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny MM, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, Muss HB, Wheeler J, Levine E et al. (2003). Barriers to clinical trial participation by older women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21, 2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A & King D (2010). Physical activity for an aging population. Physical Health Reviews, 32(2), 401–426. [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR & Banaji MR (2002). Implicit Ageism. In Ageism: Stereotypes and prejudice against older persons Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren C, Landsberg G, Schwartz H (2007). History, accomplishments, issues and prospects of supportive service programs in naturally occurring retirement communities in New York State: Lessons learned. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 49, 127–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masotti PJ, Fick R, Johnson-Masotti A, & MacLeod S (2006). Healthy naturally occurring retirement communities: A low-cost approach to facilitating healthy aging. American Journal of Public Health, 96(7), 1164–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MetLife Mature Market Institute (2006). Out and aging: The MetLife study of lesbian and gay baby boomers Retrieved from https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/mmi-out-aging-lesbian-gay-retirement.pdf

- Mustanski B, Newcomb M, & Garofalo R (2011). Mental health of lesbian, gay and bisexual youth: A developmental resilency perspective. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 23, 204–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obama Administration (2011). Obama Administration Record for the LGBT Community https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/lgbt_record.pdf

- Orel N (2004). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 43, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Orel N (2014). Investigating the Needs and Concerns of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adult: The Use of Qualitative and Quantitative Methodology. Journal of Homosexuality, 61: 53–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORC Blueprint. (2013). About NORC: What is a NORC? New York: United Hospital Fund; Retireved from: http://www.norcblueprint.org/about/ [Google Scholar]

- Peake MD, Thompson S, Lowe D, & Pearson MG (2003). Ageism in the management of lung cancer. Age and Ageing, 32, 171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portz JD, Retrum JH, Wright LA, Boggs JM, Wilkins S, Grimm C, Gilchrist K, Gozansky WS (2014). Assessing Capacity for Providing Culturally Competent Services to LGBT Older Adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57(0), 305–321. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2013.857378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Schope RD (2005). Who’s afraid of growing old? Gay and lesbian perceptions of aging. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 45, 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusher MP, Mayer CJ, & Dunkle RE (1996). Gays and lesbians older and wiser (GLOW): A support group for older gay people. The Gerontologist, 36, 118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankle MD, Maxwell CA, Katzman ES, & Landers S (2003). An invisible population: older lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Clinical Research and Regulatory Affairs 20(2). 159–182. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon W, Schultz J, & Swinburn B (2008). Problem and solution trees: a practical approach for identifying potential interventions to improve population nutrition. Health Promotion International, 23, 345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Beckerman NL, & Sherman PA (2010). Lesbian and gay elders and long-term care: Identifying the unique psychosocial perspectives and challenges. Journal of Gernotological Social Work, 53, 421–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Jewish Federations of North America. (2013). NORC: An Aging In Place Initiative Retrieved from: http://www.norcs.org/index.aspx

- Vasunilashorn S, Steinman BA, Liebig PS and Pynoos J (2012). Aging in Place: Evolution of a Research Topic Whose Time Has Come. Journal of Aging Research Volume 2012, Article ID 120952. Retrieve from: 10.1155/2012/120952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagenen A, Driskell J, Bradford J (2013) “I’m still raring to go” Successful aging among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Journal of Aging Studies 27: 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, & Ford CL (2011). The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Retrieved from http://www.healthpolicy.ucla.edu/pubs/files/aginglgbpb.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten TM (2014). Its not all darkness: Robust, resilience, and successful transgender aging. LGBT Health 1(1) 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelle A, Arms T (2015). Psychosocial Effects of Health Disparities on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 53(7). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]