Abstract

Chlorobaculum tepidum, a green sulfur bacterium, utilizes chlorobactene as its major carotenoid, and this organism also accumulates a reduced form of this monocyclic pigment, 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene. The protein catalyzing this reduction is the last unidentified enzyme in the biosynthetic pathways for all of the green sulfur bacterial pigments used for photosynthesis. The genome of C. tepidum contains two paralogous genes encoding members of the FixC family of flavoproteins: bchP, which has been shown to encode an enzyme of bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis; and bchO, for which a function has not been assigned. Here we demonstrate that a bchO mutant is unable to synthesize 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene, and when bchO is heterologously expressed in a neurosporene-producing mutant of the purple bacterium, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the encoded protein is able to catalyze the formation of 1,2-dihydroneurosporene, the major carotenoid of the only other organism reported to synthesize 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids, Blastochloris viridis. Identification of this enzyme completes the pathways for the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments in Chlorobiaceae, and accordingly and consistent with its role in carotenoid biosynthesis, we propose to rename the gene cruI. Notably, the absence of cruI in B. viridis indicates that a second 1,2-carotenoid reductase, which is structurally unrelated to CruI (BchO), must exist in nature. The evolution of this carotenoid reductase in green sulfur bacteria is discussed herein.

Keywords: photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigment, carotenoid, bacterial genetics, energy metabolism, Blastochloris viridis, Chlorobaculum tepidum, green sulfur bacterium, Rhodobacter sphaeroides

Introduction

Carotenoids are ubiquitous pigments of photosynthesis, and together with the modified tetrapyrrole molecules chlorophyll (Chl)4 and/or bacteriochlorophyll (BChl), are found in all naturally occurring Chl-dependent phototrophs (i.e. chlorophototrophs) (1) discovered to date. These isoprenoid molecules are used to harvest light by absorption of wavelengths in the 400–550-nm range of the solar spectrum and subsequently transfer excitation energy to (B)Chls in photochemical reaction center (RC) complexes where charge separation occurs (2). Carotenoids also play roles in photoprotection (via quenching of (B)Chl triplet states and scavenging of harmful radicals and singlet oxygen) and the stabilization of pigment-protein interactions in photosynthetic complexes of chlorophototrophic prokaryotes and plants (2–4). Carotenoids can also be synthesized by nonphototrophic organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and, surprisingly, insects (5). Remarkably, more than 1100 variants of these usually C40 isoprenoid compounds have been described thus far (6).

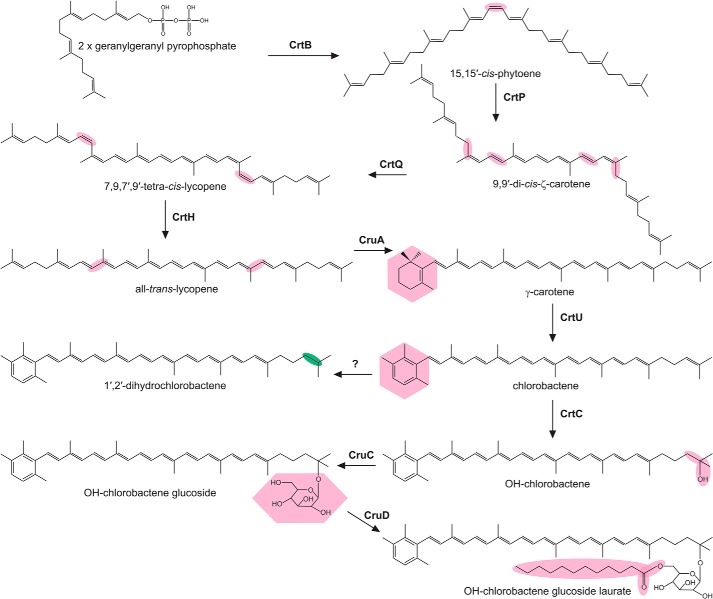

The phototrophic green sulfur bacteria (GSB) are major primary producers of biomass in anoxic environments and contribute significantly to the biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur on Earth (7). They are anoxygenic chlorophototrophs that support photosynthesis at extremely low irradiance by using specialized light-harvesting structures, chlorosomes, in which BChls c, d, or e molecules self-aggregate to form highly efficient yet elegantly simple antenna complexes (8). The major carotenoids found in GSB have cyclic, aromatic end groups (9, 10), and >90% of the carotenoids found in Chlorobaculum tepidum are located in the interior of the chlorosome (11, 12). GSB species with chlorosomes composed of BChl c (such as C. tepidum) or BChl d (such as Chlorobaculum parvum) mostly produce a monocyclic aromatic carotenoid, chlorobactene. Brown-colored GSB species, such as Chlorobaculum limnaeum, which synthesize BChl e as their main antenna BChl and can grow at greater depths in stratified lakes, primarily make the dicyclic carotenoids isorenieratene and/or β-isorenieratene (7). Using a combination of genetic manipulation and heterologous expression approaches, the majority of the enzymes involved in carotenoid biosynthesis in GSB have been identified (13–16). The carotenoid biosynthesis pathway in C. tepidum is summarized in Fig. 1, and the structures of the major carotenoids of C. limnaeum are shown in Fig. S1. Only the enzyme catalyzing the reduction of chlorobactene to produce 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene in C. tepidum remained to be identified. The only other organism reported to synthesize 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids is the purple bacterium Blastochloris viridis, which contains 15,15′-cis-1,2-dihydroneurosporene in its RC (17).

Figure 1.

Simplified carotenoid biosynthesis pathway in C. tepidum. Enzymes catalyzing known steps are next to arrows, and respective modifications are highlighted in pink. Some enzymes can modify multiple substrates, e.g. OH-γ-carotene glucoside laurate can be formed by sequential modifications to γ-carotene by CrtC, CruC, and CruD, respectively. The enzyme catalyzing the formation of 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene is unknown; the modification introduced by this enzyme is highlighted in green.

In this study we identify the 1′,2′-carotenoid reductase responsible for the synthesis of dihydrocarotenoids in C. tepidum via mutation and heterologous expression in a purple bacterial host. The identification of this gene completes the biosynthetic pathways for the carotenoids, and, together with the recent completion of the pathways for (B)Chls in GSB (18, 19), the pathways for the synthesis of all of the photopigments found in chlorophototrophic members of this phylum are now complete. Furthermore, bioinformatic analyses of the genome of B. viridis, and subsequent genetic manipulations reveal that a second, independently evolved carotenoid 1,2-reductase must exist in nature.

Results

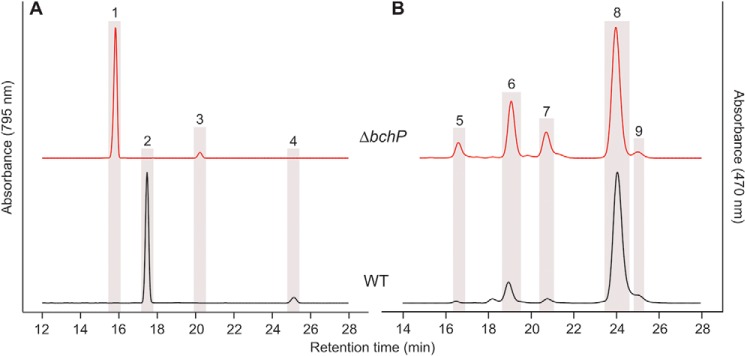

Disruption of bchO prevents the synthesis of 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene in C. tepidum

A previous study demonstrated that, of the two paralogs of the BChl biosynthesis gene, bchP, ORF CT2256 encodes an active BchP enzyme, whereas the role of the protein encoded by CT1232 (annotated as bchO) could not be established (20). The BchP and BchO proteins group with the FixC superfamily of electron-transfer, flavin-dependent reductases (21) and are members of the larger NAD(P)-binding Rossmann fold superfamily. BchP sequentially reduces three C=C bonds of the isoprenoid alcohol attached to a bacteriochlorin macrocycle, and ChlP performs the same function in the biosynthesis of Chls, converting the geranylgeranyl moiety to phytyl (22) (Fig. S2). C40 carotenoids are synthesized from two molecules of the isoprenoid compound, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, and thus the reaction to reduce the 1,2 (or 1′,2′) C=C bond, such as that carried by 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene in C. tepidum, is reminiscent of the reduction reactions catalyzed by BchP. To determine whether bchO encodes a carotenoid 1,2-reductase, the CT1232 ORF was interrupted by insertional inactivation with an aadA cassette that confers resistance to spectinomycin; the interruption was confirmed by colony PCR (Fig. S3) and subsequent sequencing of the DNA amplicon. The resulting strain, ΔbchO, was grown in liquid medium, the accumulated pigments were extracted, and, along with those from the WT, were analyzed by HPLC (Fig. 2). As expected, 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene was detected in the WT. Disruption of bchO abolished the production of 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene, indicating that BchO plays a role in the reduction of the 1′,2′ double bond in carotenoids of C. tepidum. The synthesis of all other carotenoids in C. tepidum was unaffected.

Figure 2.

HPLC elution profiles of carotenoids extracted from C. tepidum strains. Highlighted peaks indicate the following carotenoids: peak 1, chlorobactene; peak 2, OH-chlorobactene glucoside laurate; peak 3, 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene; peak 4, OH-γ-carotene glucoside laurate; and peak 5, γ-carotene. Carotenoids are identified as in Ref. 13, and two peaks for each pigment are present because of the existence of trans- and cis-conformations of each.

Expression of certain GSB bchO genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides results in the accumulation of 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids

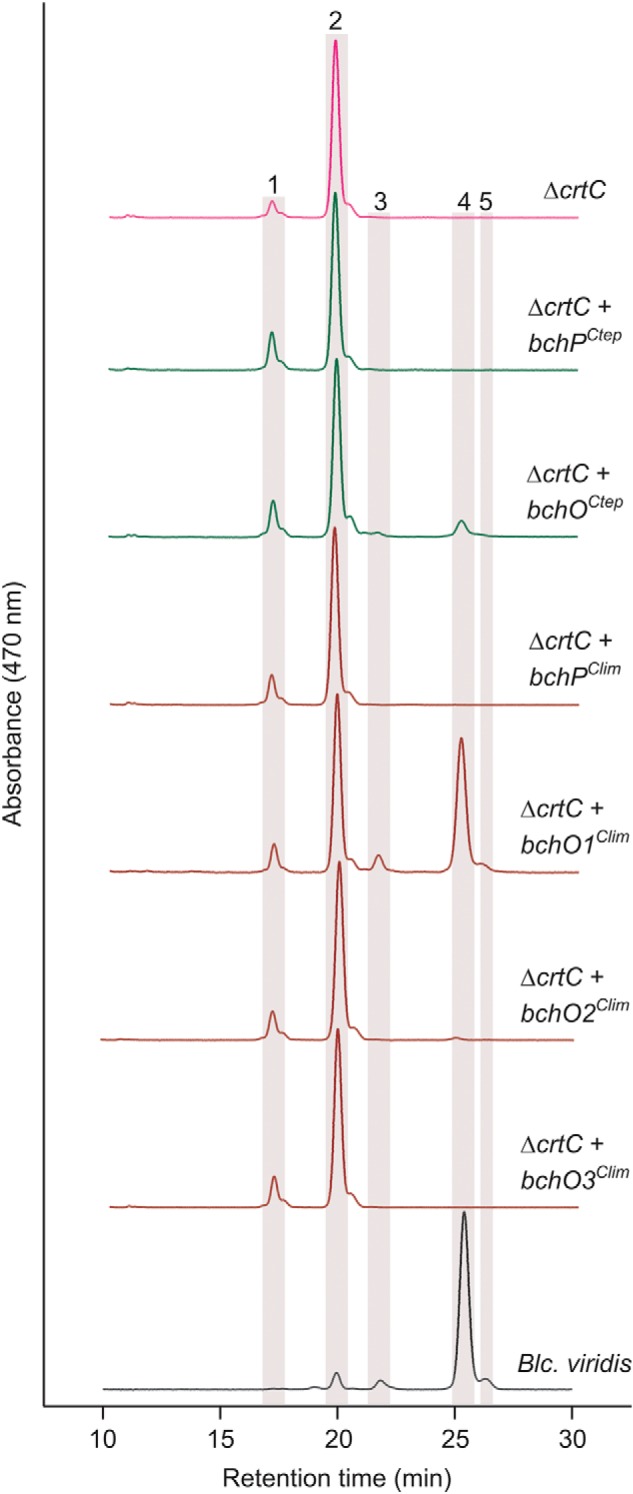

The purple phototrophic bacterium B. viridis is the only organism other than C. tepidum that has been documented to produce 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids, utilizing 1,2-dihydroneurosporene as its major carotenoid (23). The 15,15′-cis isomer of this carotenoid is found in the RC, and 1,2-dihydrolycopene is also detected as a minor pigment (24) (Fig. S4). The presumptive precursor for the major carotenoid of B. viridis, neurosporene, accumulates to high levels in a ΔcrtC mutant of the model purple phototrophic bacterium, R. sphaeroides (25). This mutant can serve as a platform in which to test whether the gene products of GSB bchO genes are sufficient to reduce the 1,2 C=C bonds of a carotenoid, by using pigments extracted from B. viridis as standards for the product(s) of the reaction. The bchP and bchO genes from C. tepidum (bchPCtep and bchOCtep), along with bchP and the three bchO paralogs found in the genome of the brown-colored, BChl e-producing C. limnaeum (bchPClim and bchO1-3Clim, where bchO1Clim encodes a protein most similar to BchOCtep), were cloned into the pBBRBB–Ppuf843–1200 plasmid (26), in which transcription is controlled by the promoter found upstream of the genes encoding the core light-harvesting antenna (LH1) and RC subunits in R. sphaeroides (27). These plasmids were conjugated into the ΔcrtC mutant of R. sphaeroides, the resulting strains were grown in liquid medium, and carotenoids were extracted and analyzed by HPLC (Fig. 3). As expected, the ΔcrtC mutant primarily accumulated neurosporene, as well as a smaller amount of lycopene. The strains expressing bchPCtep and bchPClim made the same carotenoids as the ΔcrtC mutant. The strains expressing bchOCtep and bchO2Clim made small amounts of 1,2-dihydroneurosporene, the level in the latter strain being just above the limit of detection. The strain expressing bchO1Clim accumulated 1,2-dihydroneurosporene at close to the same level as neurosporene, and both 15,15′-cis-1,2-dihydroneurosporene and 1,2-dihydrolycopene were also detected (Fig. 3). Dihydrocarotenoids were not detected in the strain expressing bchO3Clim.

Figure 3.

HPLC elution profiles of carotenoids extracted from R. sphaeroides ΔcrtC strains expressing GSB bchP and bchO paralogs. Carotenoids extracted from B. viridis are included for comparison. Highlighted peaks indicate the following carotenoids: peak 1, lycopene; peak 2, neurosporene; peak 3, 1,2-dihydrolycopene; peak 4, 1,2-dihydroneurosporene; and peak 5, 15,15′-cis-1,2-dihydroneurosporene.

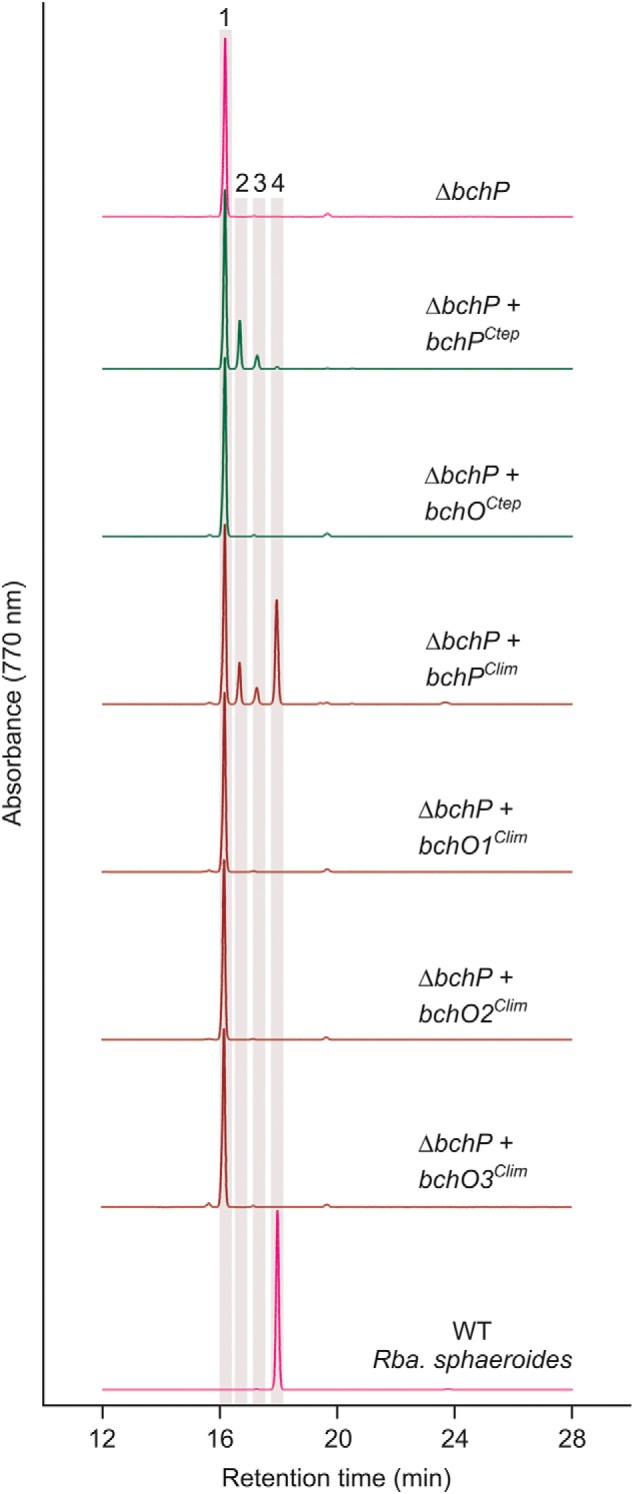

To confirm the activities of these BchP proteins as BChl reductases and to test any potential activity of BchO on BChl, these plasmids were transformed into a ΔbchP mutant of R. sphaeroides (28) that accumulates BChl a carrying a polyunsaturated geranylgeraniol moiety (Fig. 4). Expression of GSB bchP genes in this background restored synthesis of BChl a esterified with phytol, although complete conversion to the mature pigment was not achieved; products with one and two reduced double bonds were also detected. The elution profiles from strains expressing bchO orthologs were identical to that of the ΔbchP mutant, indicating that these GSB genes do not encode enzymes able to reduce the alcohol moieties of BChl a. These results establish that BchO can act as a carotenoid 1,2-reductase and indicate that the enzyme is not involved in the biosynthesis of BChls. A conserved ORF found in the photosynthesis gene clusters of many purple phototrophic bacteria is also annotated as bchO (29), although the encoded proteins share no similarity to BchO of GSB. We therefore propose, according to Demerec nomenclatural rules, that the GSB bchO genes be renamed cruI to reflect their herein established role in carotenoid biosynthesis. We further propose to eliminate the use of bchO with respect to the paralogous ORFs in those GSB for which no function can currently be assigned. We suggest that only locus tags be used to identify those ORFs.

Figure 4.

HPLC elution profiles of BChl species extracted from R. sphaeroides ΔbchP strains expressing GSB bchP and bchO paralogs. BChl a extracted from WT R. sphaeroides is included for comparison. Highlighted peaks indicate BChl a species esterified with the following isoprenoid alcohols: peak 1, geranylgeraniol; peak 2, dihydrogeranylgeraniol; peak 3, tetrahydrogeranylgeraniol; and peak 4, phytol.

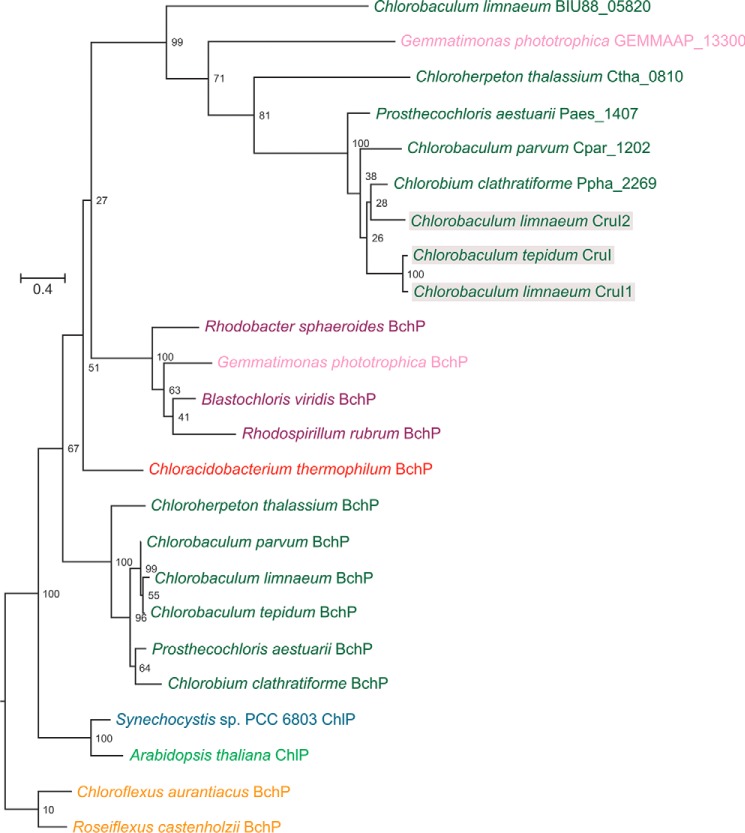

Phylogenetic analysis of BchP, CruI, and paralogous proteins

To investigate the evolutionary relationship between BchP and CruI, orthologs of each were identified in the species listed in Table S1, through the use of the C. tepidum protein sequences as queries in Blastp searches of the respective proteomes. The phylogenetic relationships among BchP, CruI, and their paralogs are shown in Fig. 5. The tree supports the assertion that cruI is paralogous to bchP but that it may have arisen through horizontal gene transfer from a purple phototrophic bacterium, because the GSB CruIs are more closely related to purple bacterial BchPs than those within GSB. Interestingly, the only cruI-like gene identified in an organism other than GSB was found in Gemmatimonas phototrophica, a recently discovered member of the Gemmatimonadetes, the seventh bacterial phylum to contain a chlorophototroph (30). G. phototrophica acquired its phototrophic capability via horizontal gene transfer of the photosynthesis gene cluster from a purple chlorophototroph (31); the presence of this paralog in G. phototrophica raises interesting questions about its origin.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationships of BchP/ChlP and CruI (BchO) paralogs. The maximum likelihood tree was constructed from amino acid alignments using the PROTGAMMAAUTO model in RAxML version 8.2.4. The numbers on the branches indicate the percentage of bootstrap support from 100 replicates, and the scale bars indicate the specified number of amino acid substitutions per site. Example organisms from green sulfur bacteria (green), purple bacteria (purple), green filamentous bacteria (Chloroflexi; amber), Acidobacteria (red), and Gemmatimonadetes (pink) are included. Cyanobacterial (cyan) and plant (light green) ChlP proteins are included for reference. CruI proteins for which activity has been detected are shaded in gray.

R. sphaeroides strains expressing additional GSB cruI homologs do not synthesize 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids

The phylogenetic analysis detailed above identified homologs of cruI in additional GSB, although these genes are not completely conserved in this phylum. This suggested that other GSB may contain active carotenoid 1′,2′-reductases. To test this hypothesis, the identified ORFs (from C. parvum, Chloroherpeton thalassium, Prosthecochloris aestuarii, and Chlorobium clathratiforme) were subsequently tested in the R. sphaeroides ΔcrtC mutant in the same manner described above. Additionally, an apparent bchP paralog present in the genome of G. phototrophica was also tested (Fig. S5). The expression of these bchP/cruI homologs in the ΔcrtC mutant did not result in the production of 1,2-dihydroneurosporene. It may be that these proteins display stricter substrate specificity than those from C. tepidum and C. limnaeum, only catalyzing the reduction of chlorobactene, γ-carotene, or some other compound (e.g. Chl a or a lipid). However, 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids have not been reported in these GSB strains, and dihydrocarotenoids do not seem to be present in G. phototrophica (32).

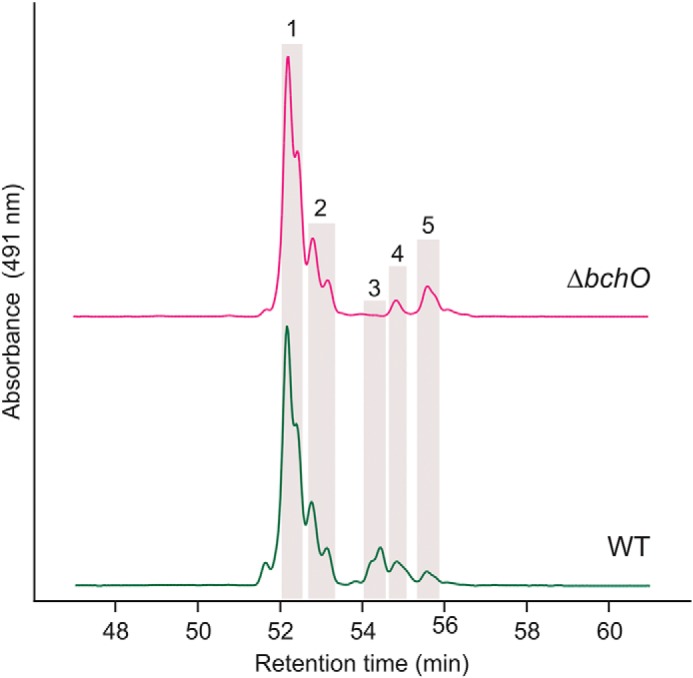

The B. viridis carotenoid 1,2-reductase is unrelated to CruI

The recently sequenced genome of B. viridis, the only strain outside the GSB documented to produce carotenoids reduced at the 1,2 position, does not contain cruI (33). In addition to the carotenoids depicted in Fig. S4, B. viridis utilizes BChl b as its primary photopigment (34) and bacteriopheophytin (BPheo) b, a demetallated analog of its parent BChl that acts as the primary electron acceptor in type-2 RCs (35). Both of these pigments carry a reduced phytyl moiety (36), and thus B. viridis must contain an active BchP. Because cruI is a paralog of bchP and catalyzes a similar reductive reaction, the B. viridis bchP (BVIR_564) gene was deleted to determine whether the encoded protein is a bifunctional BChl/carotenoid reductase. The gene was replaced at its start codon with the aadA gene, and this replacement was confirmed by colony PCR (Fig. S6) and subsequent sequencing of the DNA amplicon. The resulting strain, ΔbchP, was cultured in liquid medium, and the accumulated pigments were extracted and, along with those from the WT, analyzed by HPLC (Fig. 6). Deletion of bchP results in shifts in retention for both the major BChl b peak and the minor BPheo b peak to shorter times, consistent with the effect of mutations of chlP/bchP genes in organisms synthesizing Chl a/BChl a (37, 38) (Fig. 4). The BChl b and BPheo b in the ΔbchP mutant should now be esterified with geranylgeraniol rather than phytol, indicating that the activity of BchP has been abolished. The carotenoids from this strain were also analyzed; although the levels of lycopene and 1,2-dihydrolycopene are reduced in ΔbchP relative to the WT, both carotenoids were still detected. The major carotenoid in ΔbchP is 1,2-dihydroneurosporene. These results indicate that BchP in B. viridis is solely utilized for the synthesis of BChl b carrying a reduced esterifying alcohol moiety and that it is not responsible for the production of 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids in this organism.

Figure 6.

HPLC elution profiles of BChls (A) and carotenoids (B) extracted from B. viridis strains. Highlighted peaks indicate the following pigments: peak 1, BChl b esterified with geranylgeraniol; peak 2, BChl b esterified with phytol; peak 3, BPheo b esterified with geranylgeraniol; peak 4, BPheo b esterified with phytol; peak 5, lycopene; peak 6, neurosporene; peak 7, 1,2-dihydrolycopene; peak 8, 1,2-dihydroneurosporene; peak 9, 15,15′-cis-1,2-dihydroneurosporene.

Discussion

Our identification of CruI as a 1,2-carotenoid reductase in C. tepidum completes the pathways for the biosynthesis of carotenoids in GSB, and thus the pathways for the synthesis of all photosynthetic pigments in the Chlorobiaceae (GSB) are now known. Orthologs of cruI are irregularly found throughout the GSB, although the detection of 1,2-dihydrocarotenoids has not been reported for any additional GSB species. It may be that these cruI genes are redundant in these species. C. clathratiforme is a brown-colored GSB, synthesizing BChl e as well as dicyclic carotenoids such as those depicted in Fig. S1; these carotenoids do not have ψ-end groups available for reduction, so redundancy of cruI from this strain is unsurprising. However, C. limnaeum also accumulates BChl e and dicyclic carotenoids (10), but we have demonstrated that this strain contains at least two active CruI carotenoid reductases. C. parvum, C. thalassium (Chloroherpetonaceae), and P. aestuarii are green-colored GSB and, like C. tepidum, synthesize monocyclic carotenoids with chlorobactene or γ-carotene backbones (39, 40), but the CruI proteins from these strains may have lost function during their evolution. Alternatively, the substrate provided to these proteins may be unsuitable to determine their activities as carotenoid reductases; they may have stricter substrate specificities and only reduce carotenoids with chlorobactene or γ-carotene backbones. It is also possible that the proteins encoded by these genes have alternative functions, e.g. biosynthesis of other isoprenoid molecules or the reduction/desaturation of fatty acids. The role of the CruI proteins for which an activity has not been demonstrated will require further study, including heterologous expression in the cruI mutant of C. tepidum, which may produce more suitable substrates for these orthologs. This will require the development of a plasmid-based expression system or the identification of a neutral site in the genome in which a foreign gene and a promoter sequence can be inserted.

The absence of a cruI gene in B. viridis, which synthesizes 1,2-dihydro-derivatives of neurosporene and lycopene, suggests that an additional carotenoid 1,2-reductase exists in nature, and it must be structurally unrelated to those found in GSB. This independent evolution of unrelated enzymes catalyzing the same reaction is not uncommon in nature (41) and is in fact quite prevalent in pathways for pigment biosynthesis; unrelated enzymes catalyzing three of the intermediate steps of (B)Chl biosynthesis are known to exist (42–45), and GSB and cyanobacteria utilize three or four enzymes to produce lycopene from phytoene, whereas purple phototrophs use a single phytoene desaturase enzyme (16, 46) (see Fig. 1 and Fig. S4).

Phylogenetic analysis of BchP and CruI paralogs suggested that GSB CruI proteins are more closely related to members of the purple bacterial BchP family than the BchP proteins within GSB. It could be that an ancestral GSB acquired a purple bacterial bchP gene that would have been redundant and that this gene accumulated mutations leading to its evolutionary conversion into a gene encoding a carotenoid reductase. Similarly, G. phototrophica acquired a purple bacterial photosynthesis gene cluster via lateral transfer and contains both bchP and a cruI-like gene; the bchP gene encodes a protein that groups with the purple bacterial BchP sequences as expected, but cruI genes are absent in purple bacteria. This raises the possibility that a gene duplication occurred in a purple bacterium, and G. phototrophica acquired two copies of bchP, one of which was also transferred to GSB at some point, or even that the duplication occurred in G. phototrophica and that cruI evolved in this phylum and was subsequently transferred to the GSB. It is possible that as more genome data are acquired, cruI-like genes will be identified in diverse phyla, such as the purple bacteria, which may clarify the evolutionary history of this enzyme.

The phylogenetic relationship between BchP and CruI proteins makes it of interest to elucidate the necessity for the evolution of carotenoid 1,2-reductases. 1′,2′-Dihydrochlorobactene is a minor carotenoid in C. tepidum. It only accounts for ∼6% of total carotenoids in the WT (13), and a null mutation of cruI has no detectable effect on growth (20). C. limnaeum contains two or possibly three active 1,2-reductases, even though it exclusively synthesizes carotenoids that cannot be reduced at these positions. Additionally, cruI genes are common in GSB genomes, but 1′,2′-dihydrocarotenoids have not been documented in these strains. It may be that 1′,2′-dihydrocarotenoids play an important role in light harvesting or quenching under as-yet-untested growth conditions in GSB, which may induce their synthesis in the strains that appear not to produce them under laboratory growth regimes. In C. tepidum, reduction of the 1′,2′ double bond would prevent hydroxylation by CrtC and thus prevent further modification, such as glucoside esterification (Fig. 1), which may be advantageous at irradiances analogous to those found deep in the water column. Similarly, in brown-colored GSB like C. limnaeum, the reduction of this bond may prevent cyclization at the ψ-end, resulting in the accumulation of monocyclic carotenoids; this method may be employed to tailor the absorption properties of the organism under specific growth conditions in which dicyclic carotenoids do not provide a growth advantage. We intend to explore this further in both green- and brown-colored GSB.

1,2-Dihydroneurosporene and 1,2-dihydrolycopene, found in B. viridis, have identical spectral properties to the common neurosporene and lycopene carotenoids found in purple phototrophic bacteria. This suggests that the necessity to reduce the 1,2 C=C bonds of these carotenoids may be structural rather than spectroscopic. Saturation of this bond would make the carotenoid more flexible at the reduced end, which may be required for assembly of the RC–LH1 complex; thus, loss of the gene encoding the carotenoid 1,2-reductase unrelated to CruI in the obligate phototroph B. viridis may be lethal. The native BChl a biosynthesis pathway of R. sphaeroides can be diverted toward the production of BChl b (47), and we have demonstrated that the expression of an active GSB cruI (in particular cruI1Clim) in a ΔcrtC background of the same organism results in the production of the same complement of carotenoids produced by B. viridis. Thus, it may be possible to test the assembly of the B. viridis RC–LH1 complex in a strain of R. sphaeroides producing BChl b and dihydrocarotenoids and thereby determine the effect of the loss of a carotenoid 1,2-reductase in this background.

Experimental procedures

Growth conditions

Strains of GSB were grown in liquid CL medium or on solid CP medium as previously described (13, 48) and were incubated at 25 °C (or 42 °C for C. tepidum) under incandescent illumination (150 μmol photons·m−2·s−1). Cells for pigment analysis were grown in 25-ml cultures to early stationary phase before analysis. All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2.

R. sphaeroides strains were grown under microoxic conditions in the dark in a rotary shaker at 30 °C in liquid M22+ medium (49) supplemented with 0.1% casamino acids, and kanamycin at 30 μg·ml−1 when required, with agitation at 150 rpm. Escherichia coli strains α-Select (Bioline) and S17-1 (50) transformed with plasmids described in the text were grown in a rotary shaker at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with 30 μg·kanamycin ml−1.

B. viridis was grown phototrophically in anoxic sodium succinate medium 27 (N medium) (51) under incandescent illumination (100 μmol·photons·m−2·s−1) at 30 °C as previously described (47). When required, the medium was supplemented with kanamycin or spectinomycin at 30 μg·ml−1.

Construction of a bchO mutant of C. tepidum

Sequences encompassing the upstream and 5′ end, the 3′ end and the downstream regions, of the CT1232 locus of C. tepidum were amplified with primer pair CT1232UpF and CT1232UpR and primer pair CT1232DownF and CT1232DownR, respectively. An aadA cassette, encoding aminoglycoside 3″-adenylyltransferase and conferring resistance to streptomycin and spectinomycin, was amplified together with the promoter region from pSRA81 (13) with primer pair CT1232aadAF and CT1232aadAR. The three resulting amplicons were fused by overlap extension PCR, and the linear DNA fragment was transformed into C. tepidum as previously described (52, 53). The resulting transformants were analyzed for complete segregation by PCR analysis and sequencing with primer pair CT1232UpF and CT1232DownR.

Cloning of GSB bchP genes and their paralogs

GSB bchP genes and paralogous open reading frames were amplified from genomic DNA of described GSB strains (see text and Table S1) or from gBlocks synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) with the relevant primer pairs (Table S3), digested with BglII/BamHI and SpeI, and ligated in place of the DsRed gene in pBBRBB–Ppuf843–1200–DsRed (26) digested with BglII and SpeI.

Transformation of R. sphaeroides

Sequenced clones in the pBBRBB–Ppuf843–1200 vector backbone were conjugated into R. sphaeroides from E. coli S17-1, and transconjugants were selected on M22+ medium supplemented with kanamycin.

Construction of a bchP mutant of B. viridis

Sequences ∼600 bp upstream and downstream of BVIR_564 were amplified with primer pair bchPBvUpF and bchPBvUpR and primer pair bchPBvDownF and bchPBvDownR, respectively. The resulting amplicons were fused by overlap extension PCR, digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and ligated into similarly digested pK18mobsacB (54). The aadA gene was amplified from pSRA81 with bchPBvaadAF and bchPBvaadAF, digested with NdeI and XbaI, and ligated between these sites in the overlap between the upstream and downstream regions of BVIR_564 in the pK18mobsacB construct, such that BVIR_564 would be precisely replaced with aadA between the corresponding start and stop codons. The resulting plasmid was verified by DNA sequencing and conjugated into B. viridis using a method previously described (55). Transconjugants in which the plasmid had integrated into the genome by homologous recombination were selected on N medium supplemented with kanamycin and spectinomycin (see above). A second recombination event was then promoted by sacB-mediated selection on N medium supplemented with 5% (w/v) sucrose, containing spectinomycin but lacking kanamycin. Sucrose- and spectinomycin-resistant, kanamycin-sensitive colonies had excised the allelic exchange vector through the second recombination event, and replacement of BVIR_564 with aadA was confirmed by colony PCR and sequencing using bchPBvCheckF and bchPBvCheckR primers.

Extraction of pigments

Pigments were extracted from cell pellets with 7:2 acetone/methanol (v/v) as previously described (56). Carotenoids were further processed by addition of a drop of 5 m NaCl and an equal volume of hexane to the clarified acetone/methanol extract. The sample was mixed, and the phases were allowed to separate (57). The upper hexane phase was transferred to a glass vial, dried in a vacuum concentrator at 30 °C, and reconstituted in a small volume of 0.2% (v/v) ammonia in methanol (for analysis of carotenoids in GSB) or acetonitrile (for analysis of carotenoids in R. sphaeroides or B. viridis) prior to analysis by reversed-phase, HPLC.

Analysis of pigments by reversed-phase HPLC

Pigments were separated at a flow rate of 1 ml·min−1 at room temperature on a Supelco Discovery HS C18 (5-μm particle size, 120 Å pore size, 250 × 4.6 mm) on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system. BChl b species were separated using a method modified from that of Ortega-Ramos et al. (28). Solvents A and B were 64:16:20 (v/v/v) methanol/acetone/H2O and 80:20 (v/v) methanol/acetone, respectively. Pigments were eluted with a linear gradient of 50–100% solvent B over 10 min, followed by further elution with 100% solvent B for 25 min. Elution of species of BChl b was monitored by checking the absorbance at 795 nm.

Carotenoids extracted from C. tepidum were separated and identified as previously described (13). Solvents A and B were 42:33:25 (v/v/v) methanol/acetonitrile/H2O and 50:20:30 (v/v/v) methanol/acetonitrile/ethyl acetate, respectively. Pigments were eluted with a linear gradient of 30% to 100% solvent B over 52 min, followed by further elution with 100% solvent B for 6 min. Elution of carotenoid species was monitored by monitoring the absorbance at 490 nm.

Carotenoids extracted from R. sphaeroides and B. viridis were separated using a method modified from that of Magdaong et al. (58). Pigments were eluted on an isocratic gradient of 58:35:7 (v/v/v) acetonitrile/methanol/THF. Elution of carotenoid species was monitored at 470 and 505 nm.

Phylogenetic analysis of BchP paralogs

BchP and paralogous protein sequences from six GSB, three purple bacteria, two green filamentous bacteria (Chloroflexi), one acidobacterium (Chloracidobacterium thermophilum), and one member of the Gemmatimonadetes were used, with ChlP sequences from one higher plant and one cyanobacterium used as outgroup members (Table S1). The obtained amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (59) with default settings, and phylogenies were obtained with RAxML (60) version 8.2.4, using the automated protein model assignment algorithm and a gamma model of rate heterogeneity (-m PROTGAMMAAUTO).

Author contributions

D. P. C. and D. A. B. conceptualization; D. P. C., J. L. T., A. G. M. C., C. N. H., and D. A. B. resources; D. P. C. and D. A. B. formal analysis; D. P. C., C. N. H., and D. A. B. funding acquisition; D. P. C. validation; D. P. C. visualization; D. P. C. and A. G. M. C. methodology; D. P. C. writing-original draft; J. L. T. and A. G. M. C. investigation; J. L. T., A. G. M. C., C. N. H., and D. A. B. writing-review and editing; D. A. B. supervision; D. A. B. project administration.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by European Commission Marie Skłodowska-Curie Global Fellowship 660652 (to D. P. C.), by Grant DE-FG02–94ER20137 from the Photosynthetic Systems Program, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy (to D. A. B.), by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BB/M000265/1 (to C. N. H.), and Advanced Award 338895 from the European Research Council (to C. N. H.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S6.

- Chl

- chlorophyll

- BChl

- bacteriochlorophyll

- RC

- reaction center

- GSB

- green sulfur bacteria

- BPheo

- bacteriopheophytin.

References

- 1. Bryant D. A., and Frigaard N.-U. (2006) Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated. Trends Microbiol. 14, 488–496 10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frank H. A., and Cogdell R. J. (1996) Carotenoids in photosynthesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 63, 257–264 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paulsen H. (1999) Carotenoids and the assembly of light-harvesting complexes. In The Photochemistry of Carotenoids (Frank H. A., Young A. J., Britton G., and Cogdell R. J., eds) pp. 123–135, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gisriel C., Sarrou I., Ferlez B., Golbeck J. H., Redding K. E., and Fromme R. (2017) Structure of a symmetric photosynthetic reaction center-photosystem. Science 357, 1021–1025 10.1126/science.aan5611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moran N. A., and Jarvik T. (2010) Lateral transfer of genes from fungi underlies carotenoid production in aphids. Science 328, 624–627 10.1126/science.1187113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yabuzaki J. (2017) Carotenoids database: structures, chemical fingerprints and distribution among organisms. Database bax004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Gemerden H., and Mas J. (1995) Ecology of phototrophic sulfur bacteria. In Photosynthesis and Respiration: Vol. 2. Anoxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria (Blankenship R. E., Madigan M. T., and Bauer C. E., eds) pp. 49–85, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bryant D. A., and Canniffe D. P. (2018) How nature designs light-harvesting antenna systems: design principles and functional realization in chlorophototrophic prokaryotes. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 51, 033001 10.1088/1361-6455/aa9c3c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takaichi S., Wang Z. Y., Umetsu M., Nozawa T., Shimada K., and Madigan M. T. (1997) New carotenoids from the thermophilic green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum: 1′,2′-dihydro-γ-carotene, 1′,2′-dihydrochlorobactene, and OH-chlorobactene glucoside ester, and the carotenoid composition of different strains. Arch. Microbiol. 168, 270–276 10.1007/s002030050498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hirabayashi H., Ishii T., Takaichi S., Inoue K., and Uehara K. (2004) The role of carotenoids in the photoadaptation of the brown-colored sulfur bacterium Chlorobium phaeobacteroides. Photochem. Photobiol. 79, 280–285 10.1562/WB-03-11.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frigaard N.-U., Takaichi S., Hirota M., Shimada K., and Matsuura K. (1997) Quinones in chlorosomes of green sulfur bacteria and their role in the redox-dependent fluorescence studied in chlorosome-like bacteriochlorophyll c aggregates. Arch. Microbiol. 167, 343–349 10.1007/s002030050453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takaichi S., and Oh-oka H. (1999) Pigment composition in the reaction center complex from the thermophilic green sulfur bacterium, Chlorobium tepidum: carotenoid glucoside esters, menaquinone and chlorophylls. Plant Cell Physiol. 40, 691–694 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frigaard N.-U., Maresca J. A., Yunker C. E., Jones A. D., and Bryant D. A. (2004) Genetic manipulation of carotenoid biosynthesis in the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum. J. Bacteriol. 186, 5210–5220 10.1128/JB.186.16.5210-5220.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maresca J. A., and Bryant D. A. (2006) Two genes encoding new carotenoid-modifying enzymes in the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6217–6223 10.1128/JB.00766-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maresca J. A., Graham J. E., Wu M., Eisen J. A., and Bryant D. A. (2007) Identification of a fourth family of lycopene cyclases in photosynthetic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11784–11789 10.1073/pnas.0702984104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maresca J. A., Romberger S. P., and Bryant D. A. (2008) Isorenieratene biosynthesis in green sulfur bacteria requires the cooperative actions of two carotenoid cyclases. J. Bacteriol. 190, 6384–6391 10.1128/JB.00758-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Michel H., Epp O., and Deisenhofer J. (1986) Pigment-protein interactions in the photosynthetic reaction centre from Rhodopseudomonas viridis. EMBO J. 5, 2445–2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harada J., Mizoguchi T., Satoh S., Tsukatani Y., Yokono M., Noguchi M., Tanaka A., and Tamiaki H. (2013) Specific gene bciD for C7-methyl oxidation in bacteriochlorophyll e biosynthesis of brown-colored green sulfur bacteria. PLoS One 8, e60026 10.1371/journal.pone.0060026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thweatt J. L., Ferlez B. H., Golbeck J. H., and Bryant D. A. (2017) BciD is a radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) enzyme that completes bacteriochlorophyllide e biosynthesis by oxidizing a methyl group into a formyl group at C-7. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 1361–1373 10.1074/jbc.M116.767665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gomez Maqueo Chew A., Frigaard N.-U., and Bryant D. A. (2008) Identification of the bchP gene, encoding geranylgeranyl reductase in Chlorobaculum tepidum. J. Bacteriol. 190, 747–749 10.1128/JB.01430-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Edgren T., and Nordlund S. (2004) The fixABCX genes in Rhodospirillum rubrum encode a putative membrane complex participating in electron transfer to nitrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 186, 2052–2060 10.1128/JB.186.7.2052-2060.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Addlesee H. A., Gibson L. C., Jensen P.-E., and Hunter C. N. (1996) Cloning, sequencing and functional assignment of the chlorophyll biosynthesis gene, chlP, of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett. 389, 126–130 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00549-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malhotra H. C., Britton G., and Goodwin T. W. (1970) Occurrence of 1,2-dihydro-carotenoids in Rhodopseudomonas viridis. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. 127–128 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qian P., Siebert C. A., Wang P., Canniffe D. P., and Hunter C. N. (2018) Cryo-EM structure of the Blastochloris viridis LH1-RC complex at 2.9 Å. Nature 556, 203–208 10.1038/s41586-018-0014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chi S. C., Mothersole D. J., Dilbeck P., Niedzwiedzki D. M., Zhang H., Qian P., Vasilev C., Grayson K. J., Jackson P. J., Martin E. C., Li Y., Holten D., and Hunter C. N. (2015) Assembly of functional photosystem complexes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides incorporating carotenoids from the spirilloxanthin pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 189–201 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tikh I. B., Held M., and Schmidt-Dannert C. (2014) BioBrick™ compatible vector system for protein expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 3111–3119 10.1007/s00253-014-5527-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gong L., and Kaplan S. (1996) Translational control of puf operon expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Microbiology 142, 2057–2069 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ortega-Ramos M., Canniffe D. P., Radle M. I., Hunter C. N., Bryant D. A., and Golbeck J. H. (2018) Engineered biosynthesis of bacteriochlorophyll gF in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1859, 501–509 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kumka J. E., and Bauer C. E. (2015) Analysis of the FnrL regulon in Rhodobacter capsulatus reveals limited regulon overlap with orthologues from Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Escherichia coli. BMC Genomics 16, 895 10.1186/s12864-015-2162-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeng Y., Feng F., Medová H., Dean J., and Koblížek M. (2014) Functional type 2 photosynthetic reaction centers found in the rare bacterial phylum Gemmatimonadetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 7795–7800 10.1073/pnas.1400295111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeng Y., and Koblížek M. (2017) Phototrophic Gemmatimonadetes: a new “purple” branch on the bacterial tree of life. In Modern Topics in the Phototrophic Prokaryotes: Environmental and Applied Aspects (Hallenbeck P. C., ed) pp. 163–192, Springer, Cham, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zeng Y., Selyanin V., Lukeš M., Dean J., Kaftan D., Feng F., and Koblížek M. (2015) Characterization of the microaerophilic, bacteriochlorophyll a-containing bacterium Gemmatimonas phototrophica sp. nov., and emended descriptions of the genus Gemmatimonas and Gemmatimonas aurantiaca. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65, 2410–2419 10.1099/ijs.0.000272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu L. N., Faulkner M., Liu X., Huang F., Darby A. C., and Hall N. (2016) Revised genome sequence of the purple photosynthetic bacterium Blastochloris viridis. Genome Announc. 4, e01520–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Drews G., and Giesbrecht P. (1966) Rhodopseudomonas viridis, nov. spec., ein neu isoliertes, obligat phototrophes Bakterium. Arch. Mikrobiol. 53, 255–262 10.1007/BF00446672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klimov V. V. (2003) Discovery of pheophytin function in the photosynthetic energy conversion as the primary electron acceptor of photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 76, 247–253 10.1023/A:1024990408747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scheer H., Svec W. A., Cope B. T., Studier M. H., Scott R. G., and Katz J. J. (1974) Structure of bacteriochlorophyll b. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96, 3714–3716 10.1021/ja00818a092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shpilyov A. V., Zinchenko V. V., Shestakov S. V., Grimm B., and Lokstein H. (2005) Inactivation of the geranylgeranyl reductase (ChlP) gene in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1706, 195–203 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Addlesee H. A., and Hunter C. N. (1999) Physical mapping and functional assignment of the geranylgeranyl-bacteriochlorophyll reductase gene, bchP, of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 181, 7248–7255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gibson J., Pfennig N., and Waterbury J. B. (1984) Chloroherpeton thalassium gen. nov. et spec. nov., a non-filamentous, flexing and gliding green sulfur bacterium. Arch. Microbiol. 138, 96–101 10.1007/BF00413007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Permentier H. P., Schmidt K. A., Kobayashi M., Akiyama M., Hager-Braun C., Neerken S., Miller M., and Amesz J. (2000) Composition and optical properties of reaction centre core complexes from the green sulfur bacteria Prosthecochloris aestuarii and Chlorobium tepidum. Photosynth. Res. 64, 27–39 10.1023/A:1026515027824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Galperin M. Y., Walker D. R., and Koonin E. V. (1998) Analogous enzymes: independent inventions in enzyme evolution. Genome Res. 8, 779–790 10.1101/gr.8.8.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ouchane S., Steunou A. S., Picaud M., and Astier C. (2004) Aerobic and anaerobic Mg-protoporphyrin monomethyl ester cyclases in purple bacteria: a strategy adopted to bypass the repressive oxygen control system. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6385–6394 10.1074/jbc.M309851200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Suzuki J. Y., Bollivar D. W., and Bauer C. E. (1997) Genetic analysis of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31, 61–89 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu Z., and Bryant D. A. (2011) Multiple types of 8-vinyl reductases for (bacterio)chlorophyll biosynthesis occur in many green sulfur bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 193, 4996–4998 10.1128/JB.05520-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bryant D. A., Liu Z., Li T., Zhao F., Garcia Costas A. M., Klatt C. G., Ward D. M., Frigaard N.-U., and Overmann J. (2012) Comparative and functional genomics of anoxygenic green bacteria from the taxa Chlorobi, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteria. In Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration: Vol. 35. Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems (Burnap R. L., and Vermaasl W., eds) pp. 47–102, Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 46. Armstrong G. (1999) Carotenoid genetics and biochemistry. In Isoprenoids including Carotenoids and Steroids (Cane D. E., ed) Vol. 2, pp. 321–352, Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 47. Canniffe D. P., and Hunter C. N. (2014) Engineered biosynthesis of bacteriochlorophyll b in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 1611–1616 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wahlund T. M., and Madigan M. T. (1995) Genetic transfer by conjugation in the thermophilic green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum. J. Bacteriol. 177, 2583–2588 10.1128/jb.177.9.2583-2588.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hunter C. N., and Turner G. (1988) Transfer of genes coding for apoproteins of reaction centre and light-harvesting LH1 complexes to Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134, 1471–1480 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Simon R., Priefer U., and Pühler A. (1983) A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1, 784–791 10.1038/nbt1183-784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Claus D., and Schaub-Engels C. (eds) (1977) German Collection of Microorganisms: Catalogue of Strains, 2nd ed., pp. 279–280 DSMZ Catalogue of Microorganisms, Braunschweig, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 52. Frigaard N.-U., and Bryant D. A. (2001) Chromosomal gene inactivation in the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum by natural transformation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2538–2544 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2538-2544.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Frigaard N.-U., Sakuragi Y., and Bryant D. A. (2004) Gene inactivation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 and the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum using in vitro-made DNA constructs and natural transformation. Methods Mol. Biol. 274, 325–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schäfer A., Tauch A., Jäger W., Kalinowski J., Thierbach G., and Pühler A. (1994) Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145, 69–73 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chen G. E., Canniffe D. P., Martin E. C., and Hunter C. N. (2016) Absence of the cbb3 terminal oxidase reveals an active oxygen-dependent cyclase involved in bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 198, 2056–2063 10.1128/JB.00121-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hitchcock A., Jackson P. J., Chidgey J. W., Dickman M. J., Hunter C. N., and Canniffe D. P. (2016) Biosynthesis of chlorophyll a in a purple bacterial phototroph and assembly into a plant chlorophyll-protein complex. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 948–954 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Canniffe D. P., Chidgey J. W., and Hunter C. N. (2014) Elucidation of the preferred routes of C8-vinyl reduction in chlorophyll and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis. Biochem. J. 462, 433–440 10.1042/BJ20140163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Magdaong N. C., Niedzwiedzki D. M., Goodson C., and Blankenship R. E. (2016) Carotenoid-to-bacteriochlorophyll energy transfer in the LH1-RC core complex of a bacteriochlorophyll b containing purple photosynthetic bacterium Blastochloris viridis. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 5159–5171 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b04307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Edgar R. C. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stamatakis A. (2014) RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.