Significance

The early frog embryo provides a classical model system for the isolation of secreted molecules that regulate long-range cell–cell communication. Extensive screens of a region with embryonic induction activity, called Spemann organizer, have revealed a large number of secreted growth factor antagonists. Here, we used high-throughput sequencing of differentiating ectodermal explants to isolate yet another potent Wnt inhibitor expressed in Spemann organizer tissue. Bighead is a secreted protein that inhibits Wnt by causing the endocytosis and degradation in lysosomes of the Wnt coreceptor Lrp6. Its overexpression induces embryos with larger heads, and its knockdown reduces head development through the regulation of Wnt signaling. Many Wnt inhibitors exist, and we find that endocytosis regulation is crucial for function.

Keywords: neural induction, head development, animal cap dissociation, endocytosis regulation, lysosomes

Abstract

The Xenopus laevis embryo has been subjected to almost saturating screens for molecules specifically expressed in dorsal Spemann organizer tissue. In this study, we performed high-throughput RNA sequencing of ectodermal explants, called animal caps, which normally give rise to epidermis. We analyzed dissociated animal cap cells that, through sustained activation of MAPK, differentiate into neural tissue. We also microinjected mRNAs for Cerberus, Chordin, FGF8, BMP4, Wnt8, and Xnr2, which induce neural or other germ layer differentiations. The searchable database provided here represents a valuable resource for the early vertebrate cell differentiation. These analyses resulted in the identification of a gene present in frog and fish, which we call Bighead. Surprisingly, at gastrula, it was expressed in the Spemann organizer and endoderm, rather than in ectoderm as we expected. Despite the plethora of genes already mined from Spemann organizer tissue, Bighead encodes a secreted protein that proved to be a potent inhibitor of Wnt signaling in a number of embryological and cultured cell signaling assays. Overexpression of Bighead resulted in large head structures very similar to those of the well-known Wnt antagonists Dkk1 and Frzb-1. Knockdown of Bighead with specific antisense morpholinos resulted in embryos with reduced head structures, due to increased Wnt signaling. Bighead protein bound specifically to the Wnt coreceptor lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (Lrp6), leading to its removal from the cell surface. Bighead joins two other Wnt antagonists, Dkk1 and Angptl4, which function as Lrp6 endocytosis regulators. These results suggest that endocytosis plays a crucial role in Wnt signaling.

In 1924, Spemann and Mangold (1) showed that the dorsal lip of the amphibian blastopore, the Spemann organizer, could induce a twinned body axis when transplanted to the ventral side of a host embryo. The transplanted tissue contributed to the notochord and somites of the secondary axis and, remarkably, induced a new central nervous system (CNS) entirely derived from ectoderm of the host that would otherwise had given rise to epidermis (2). For this discovery of embryonic induction, Spemann was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1935. Neural induction, also called primary induction, has been an intense focus of research in developmental biology (3). Exhaustive screens on Spemann organizer tissues led to the isolation of many novel secreted growth factor antagonists that can promote neural induction. These include the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) inhibitors Noggin, Chordin, and Follistatin; the Wnt antagonists Frzb-1, Dickkopf 1 (Dkk1), Crescent, secreted Frizzled-related protein 2 (sFRP2), and angiopoietin-like 4 (Angptl4); the Nodal antagonist Lefty-1/Antivin; and Cerberus, a multivalent inhibitor of Nodal, Wnt, and BMP (4–6).

Explants of Xenopus blastula ectoderm, called animal caps, develop into epidermis but can be induced to become anterior neural tissue by microinjection of Chordin, Noggin, or Follistatin mRNA (7). Fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8) and Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) also have potent neural induction properties in many systems through the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (8–10), which down-regulates the activity of the transcription factors Smad1/5/8 and Smad4 by priming inhibitory phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) (10, 11). Suppression of both the BMP/Smad1 and the TGF-β/Smad2 pathways is required for sustained neural induction (12), and FGF8 facilitates this process. Importantly, in the chicken embryo, it has been shown that Wnt inhibition is required in epiblast for FGF and BMP antagonists to be able to induce neural tissue (13).

Despite this plethora of potential neural inducers, Barth (14) and Holtfreter (15) showed decades ago that axolotl animal caps could be coaxed to form neural tissue in the complete absence of any inducers simply by culturing them attached to glass, and, much later, we found this was due to sustained activation of MAPK (16). In Xenopus, neural differentiation can be triggered in the complete absence of organizer by simply dissociating animal cap cells and culturing them for 3 h or longer in saline solution (17, 18). Cell dissociation causes a sustained activation of MAPK, which is required for neural differentiation (19).

The recent completion of the Xenopus laevis genome (20) has made it possible to analyze the expression of 43,673 protein-coding annotated genes by high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). In previous work, we used this to analyze gene expression in organizer tissue and mRNA-injected embryos (21, 22) and identified two Wnt antagonists, protein kinase domain containing cytoplasmic/vertebrate lonesome kinase (PKDCC/Vlk) (21) and Angptl4 (6).

In the present study, we investigated neural induction in dissociated animal caps cultured until the late gastrula stage (stage 12), and compared it with neural induction mediated by a number of microinjected neural-inducing mRNAs. Here, we provide searchable databases in the supplementary datasets (Datasets S1–S3) that represent a rich resource for embryologists interested in vertebrate neural differentiation. From these studies, we identified a transcript that was increased by cell dissociation, Cerberus, Chordin, and Wnt treatments. This gene, which we call Bighead, encodes a secreted Wnt antagonist protein of 276 aa that is required for head development.

Results

Identifying Genes That Regulate Neural and Epidermal Cell Fate.

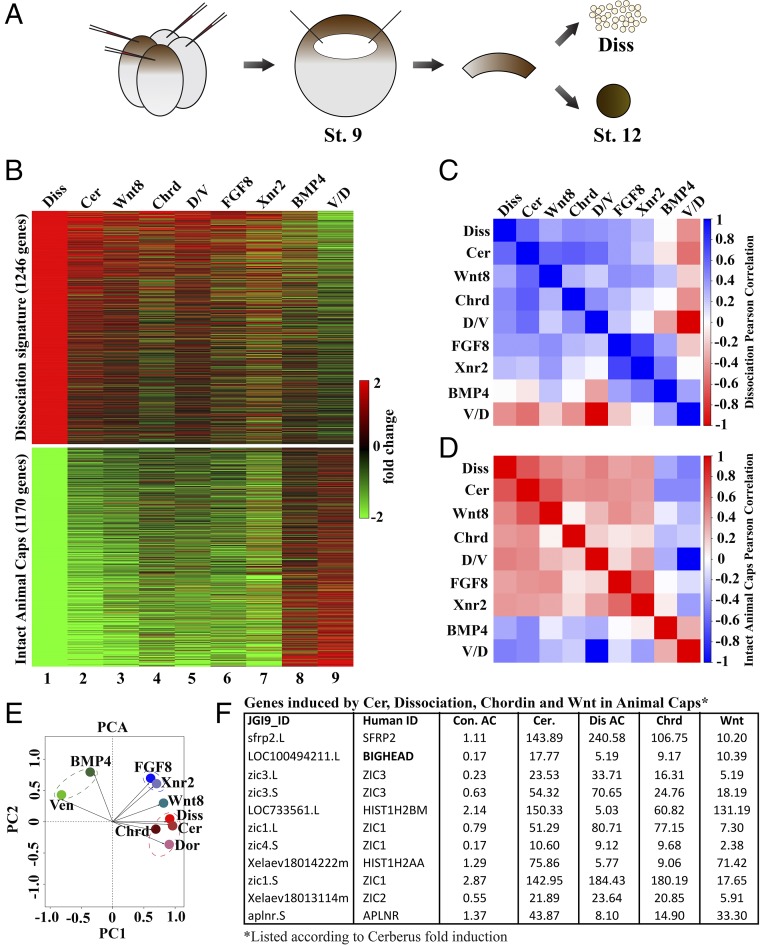

The amphibian embryo animal cap system is ideal to study the choice between neural and epidermal differentiation (19). In this study, animal caps were excised at blastula (stage 9) and cultured until late gastrula (stage 12), a period of about 8 h (23) (Fig. 1A). In some cases, mRNAs were microinjected into the animal (top) region of the embryo at the four-cell stage harvested at late gastrula (Fig. 1A). RNA-seq of dissociated versus intact caps identified a signature of genes up-regulated by dissociation (indicating neural induction) of 1,246 genes defined by transcripts induced twofold and increased by a minimum of 2 reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKMs), eliminating all genes with an average below 1 RPKM (Fig. 1B). An atypical epidermis signature of 1,170 genes was also defined using the same criteria (Fig. 1B). (Epidermis in undissociated animal caps is called atypical because it contains small cavities of poorly organized basement membrane surrounded by keratinized cells.) The RPKM values for all annotated X. laevis JGI9.1 genome transcripts for intact or dissociated animal cap cells in triplicate experiments are shown in Dataset S1.

Fig. 1.

Transcriptome analysis of stage 12 animal cap explants. (A) Illustration of mRNA injection four-cell and animal cap excision at stage (St.) 9. Animal caps were cultured until St. 12 and collected for RNA-seq with or without cell dissociation (Diss). (B) Heat map showing fold changes of the cell dissociation and atypical epidermis signatures. Atypical epidermis corresponds to uninjected animal caps cut at stage 9 and cultured until stage 12; these controls and the dissociated cells correspond to experiment 1 shown in Dataset S1 and are from the same experiment. These gene signatures were also compared with Cerberus, Wnt8, Chordin, FGF8, or BMP4 mRNA-injected animal caps, or with D/V half-embryos derived from the same clutch of embryos. V/D, ventral/dorsal. Rows and columns were left unclustered. Note that many genes induced by dissociation were induced in all conditions, except for BMP4 mRNA-injected animal caps and ventral halves. Genes in the atypical epidermis signature were only induced by BMP4 injection and in ventral halves. A correlation matrix of the animal cap dissociation (C) and atypical epidermis signatures in the RNA-seq libraries (D) are shown. Correlation scores were calculated as Pearson correlation coefficients and color-coded as shown in the scale bar on the right of the panel. These results show that the animal cap signatures obtained via RNA-seq readily distinguish neural- and epidermal-inducing conditions. (E) Dissociation signature examined via PCA to analyze dimensionality in nine experimental conditions (BMP/con AC, Ven/Dor, FGF8/con AC, Xnr2/con AC, Wnt8/con AC, Cer/con AC, Diss/con, Dor/Ven, and Chrd/con AC). AC, animal cap; con, control; Dor, dorsal; Ven, ventral. Each axis represents a principal component (PC1 and PC2), with the first one showing the most variation. PCA clustered epidermal-forming conditions (Ven and BMP), neural-inducing conditions (Diss, Cer, Chrd, and D/V), and mesoderm-forming conditions (FGF8 and Xnr2) without systemic bias. Note that epidermal and dissociation conditions lie on opposing quadrants, indicating the greatest differences. (F) Table of genes induced by Cer mRNA, dissociation, Chrd mRNA, and Wnt mRNA in animal caps listed according to Cerberus fold induction. Because Bighead was induced in all neuralizing conditions and ranked second in the list, it was chosen for further analysis.

The dissociation and epidermal signatures were most similar to those of Cerberus-overexpressing animal caps in heat map analyses (Fig. 1B, compare columns 1 and 2). This was consistent with neural induction, as Cerberus is a multivalent antagonist of Nodal, BMP, and Wnt signaling that causes potent anterior neural induction in Xenopus animal caps (24, 25). We also compared these signatures with those of xWnt8 mRNA (26) and Chordin mRNA (7) injected caps; FGF8 (27), Xnr2 (28), and BMP4 (29) mRNA injected caps; and dorsal-ventral (D/V) transcripts of embryos cut in half at stage 10 and allowed to regenerate until stage 12 (30). All these results are integrated in the heat map of Fig. 1B. The RPKMs for over 15,000 transcripts are available by opening the tabs at the bottom of Dataset S2, and the raw data for all 16 RNA-seq libraries analyzed in this paper are publicly available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (accession no. GSE106320). These data offer the community a rich open resource for investigating neural, mesodermal, and endodermal germ layer differentiation.

In Pearson correlations, the genes of the dissociation signature positively correlated with all conditions, except for BMP4 and ventral-half embryos (Fig. 1C). Mesoderm inducers such as Xnr2 induce neural tissue secondarily to endomesoderm induction, and Chordin and FGF8 can induce neural tissue directly (10, 31). A surprise was that xWnt8, which was thought to act merely as a competence modifier of the response to activin in animal caps lacking inducing activity of their own (32), strongly up-regulated many cell dissociation-activated genes in the present RNA-seq experiments (Fig. 1 B and C). The atypical epidermis signature correlated with BMP4 and ventral genes, and strongly anticorrelated with the other conditions (Fig. 1D). As shown in Fig. 1E, principal component analysis (PCA) of the cell dissociation signature clustered together epidermal-inducing conditions (BMP and ventral genes), mesoderm-inducing factors (FGF8 and Xnr2), and neural-inducing conditions (dissociation, Cerberus, and Chordin). Dorsal was 180° from ventral (as expected), while Wnt8 mRNA-injected caps were in between the mesodermal and neural clusters (Fig. 1E).

Next, we sorted genes coordinately up-regulated in the neural/dorsal cluster to identify common genes (Fig. 1F and Dataset S3). The top match was sFRP2, a Wnt antagonist we had previously identified in the early neural plate (33). The second most up-regulated gene shared by dissociated, Cerberus, Chordin, and Wnt8 animal caps was a gene of unknown function designated as LOC100494211.L (Fig. 1F), which we renamed Bighead due to its overexpression phenotype. This gene is the subject of the rest of this study.

Bighead Is a Secreted Factor Expressed in Dorsal Endomesoderm and Neural Tissue.

Bighead mRNA was expressed from stage 9 onward as determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, in situ hybridization showed that at stage 10, Bighead mRNA expression was strongest in the Spemann organizer (Fig. 2B). In bisected embryos, it was expressed throughout the endoderm but appeared stronger in the superficial yolk plug endoderm during gastrula, including at stage 12, when RNAs were harvested (Fig. 2B). At tadpole stages, Bighead transcripts were detected in the neural tube (in the midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord alar plate) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A–E). Analysis of the 276-aa predicted protein indicated the presence of a putative signal peptide within its first 20 aa (34).

Fig. 2.

Bighead is a Spemann organizer-secreted protein. (A) RT-PCR assay showing Bighead (BH) expression across different developmental stages. Histone 4 (H4) was used as a loading control. H2O and –RT served as negative controls. (B) In-situ hybridization of Bighead shows its prominent localization in the Spemann organizer in stage 10 whole embryos and stage 10.5–12 hemisected embryos. Note that there is prominent pan-endodermal localization, particularly in nuclei of the superficial yolk plug region. Embryo pictures were taken at 25× magnification. (C) Wild-type Bighead was secreted into the culture medium by transfected HEK293T cells (lane 5), while a mutant Bighead (ΔBighead) lacking the signal peptide was not (lane 6). Tubulin served as a loading control. IB, immunoblot. (D) Crystal structure of myostatin/GDF8 dimer (38), showing in red the C-terminal part of one of its prodomains that may share structural similarities with Bighead. The amino-terminal part of the myostatin prodomain is shown in gray, and the mature growth factor dimer is shown in yellow. (E) Close-up view of the conserved pro-myostatin structural domain, showing that the deletions (cyan) and insertions (yellow) found in Bighead homologs (Dataset S4) fall within loops without perturbing the β-sheet and α-helical structures.

To show that Bighead was a secreted factor, we analyzed the culture medium of transfected HEK293T cells or frog animal cap cells overexpressing a carboxyl (C)-terminal HA-tagged form of Bighead. Western blots confirmed the secretion of Bighead into the extracellular milieu, and that deletion of the signal peptide eliminated its secretion (Fig. 2C, lanes 5 and 6 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). Similarly, a recombinant Bighead protein containing an HA-tagged constant region of IgG 1 (IgG1) was secreted and efficiently pulled down from the medium of cultured cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1G), providing a useful tool for the biochemical analyses below.

X. laevis is allotetraploid (the result of a genome duplication of a species hybrid) (20) and contains two Bighead genes, namely, Bighead.L (longer chromosomes) and Bighead.S (short chromosomes), which encode two proteins sharing 85% amino acid sequence identity. Animal cap RNA-seq showed that Bighead was increased by microinjections of all mRNAs, and their combinations, tested in this study (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (35) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C) confirmed that the Bighead-induced gene set correlated with the Spemann organizer marker Chordin. Using RT-qPCR analysis on animal caps, we found that Bighead, like Siamois, was increased by xWnt8 mRNA, indicating that Bighead was a potential Wnt target (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B). RT-PCR analysis of Xenopus embryo D/V marginal zone explants also showed that microinjection of xWnt8 mRNA induced Bighead expression in the ventral marginal zone, while β-catenin morpholino (MO) prevented its expression in the dorsal marginal zone (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D). The results indicate that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is sufficient and required for Bighead transcription, suggesting Bighead might function as a Wnt-negative feedback regulator (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E).

Surprisingly, National Center for Biotechnology Information Position-Specific Iterated BLAST searches for Bighead homologs using amino acid sequences retrieved many fish and frog homologs, but no significantly conserved sequences were found in amniotes or invertebrates (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and E and Dataset S4). In the Xenopus genome, Bighead is flanked by the genes aspartate beta-hydroxylase domain containing 2 (Asphd2) and Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome 4 (Hps4); synteny is maintained in the mouse genome, but Bighead was deleted. Bighead was not conserved in any invertebrates; therefore, this gene appears to be an invention that appeared in fish, both cartilaginous and bony. However, a SWISS-MODEL (36) search for structural templates, which is based on HHblits (37), suggested the proregion of myostatin/growth and differentiation factor 8 (GDF8) as one of the templates for the C terminus of Bighead (Fig. 2 D and E). Myostatin is a member of the TGF-β superfamily. In TGF-β, the proregion that precedes the mature growth factor keeps signaling activity in a latent form and also mediates binding to the extracellular matrix (38, 39). The identity between pro-myostatin (amino acids 135–257) and Bighead (amino acids 157–275) is weak (16%) in terms of primary sequence, but a match to the complete myostatin prodomain, and compatibility of the pattern of insertions and deletions in 62 fish and frog Bighead homologs with the secondary structure elements of myostatin (Fig. 2E and Dataset S4) suggests the homology match may be relevant. Prodomains of TGF-β differ greatly in amino acid sequence, but the tertiary structures of the domain shown in Fig. 2E can be aligned among myostatin, BMP9, activin A, and TGF-β1 (38, 40).

Taken together, these results indicate that Bighead encodes a novel secreted protein expressed in the frog Spemann organizer that is conserved in many fish and amphibians. It is possible that Bighead might have evolved from the proregion of an ancestral TGF-β homolog and that the gene was subsequently lost in amniotes.

Bighead Is a Potent Inhibitor of Wnt Signaling.

To test for biological activity in vivo, Bighead mRNA was injected into the animal region of all four blastomeres of four-cell–stage Xenopus embryos. Its overexpression caused a striking enlargement of the anterior region, particularly of the head and cement gland (compare Fig. 3 A and A′). The phenotype was immediately reminiscent of that induced by the Wnt inhibitors Dkk1 (41) and Frzb-1 (42). The S and L Bighead mRNAs generated similar phenotypes (and required secretion, since signal peptide deletion eliminated all activity) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–E). Bighead mRNA substantially expanded expression of the early brain markers Rx2a, Otx2, and BF1/FoxG1 (Fig. 3 B–D′). Further supporting the possibility that Bighead encodes a Wnt inhibitor, expression of the zygotic Wnt target gene Engrailed 2 (En2) at the midbrain-hindbrain border was specifically inhibited at the neurula stage, while the rhombomere 3 and 5 marker Krox20 was unaffected (arrowhead in Fig. 3 E and E′). Similar results were observed by unilateral injection of Bighead mRNA in two-cell-stage embryos (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 F–I′).

Fig. 3.

Bighead promotes head formation and is a Wnt antagonist. Embryos were injected four times into the animal pole with 800 pg of Bighead mRNA at the four-cell stage. All embryo pictures were taken at 25× magnification. (A and A′) Bighead mRNA injection enlarges the head and cement gland at the tail bud stage; arrowheads indicate the cement gland. Ctrl, control. (B–D′) In situ hybridizations showing that Bighead mRNA injection expands Rx2a (88%, n = 35), Otx2 (93%, n = 28), and BF1/FoxG1 (79%, n = 48); arrowheads delimit the extent of expansion. (E and E′) Wnt target gene En2 (arrowhead) at the midbrain-hindbrain border is inhibited by Bighead, whereas Krox20 marking rhombomeres 3 and 5 remains largely unaffected (92%, n = 50). (F–J) Coinjection of Bighead mRNA inhibited xWnt8 mRNA ectopic axis-inducing activity, but not β-catenin mRNA activity, in axial duplication assays. Embryos were injected at the four-cell stage into a ventral-vegetal cell with the indicated mRNAs and collected for in situ hybridization for Sox2 at the tail bud stage. The following doses of mRNA were used: 1 pg of xWnt8, 500 pg of sGFP (a secreted form of GFP without phenotypic activity) or 500 pg of Bighead, and 80 pg of β-catenin. (K) Quantification of the experiments shown in F–J; n indicates the number of embryos analyzed for each experimental condition. (L and M) Bighead inhibits xWnt8-induced Siamois and Xnr3 expression. Embryos were injected into the animal pole with 8 pg of xWnt8 mRNA with or without 800 pg of sGFP or Bighead mRNA into four cells at the four-cell stage. Animal caps were dissected at stage 9 and processed for RT-qPCR for the early Wnt targets Siamois (L) and Xnr3 (M). Note that Bighead significantly inhibits both Wnt targets; the experiment was performed in triplicate (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

We next tested whether Bighead was a Wnt antagonist in Xenopus (43). Coinjection of Bighead mRNA together with xWnt8 mRNA inhibited the formation of secondary axes, but had no effect on axes induced by β-catenin mRNA (Fig. 3 F–K). Similarly, RT-qPCR analysis on animal caps showed that Bighead inhibited the induction of the early targets Siamois and Xnr3 by xWnt8, but not by β-catenin (Fig. 3 L and M and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 J and K).

These results indicate that the secreted protein Bighead promotes head development and inhibits Wnt signaling upstream of β-catenin.

Bighead Is Required for Head Formation.

To study the loss of function of Bighead, we designed antisense translation-blocking MOs (44) targeting Bighead.L and Bighead.S (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). We also designed a recombinant HA-Bighead.S construct resistant to the MOs (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). When injected into embryos, Bighead.L MO and Bighead.S MO blocked the translation of Bighead.L-HA and Bighead.S-HA mRNA, respectively, while a combination of these two MOs failed to block MO-resistant HA-Bighead.S translation (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B–D).

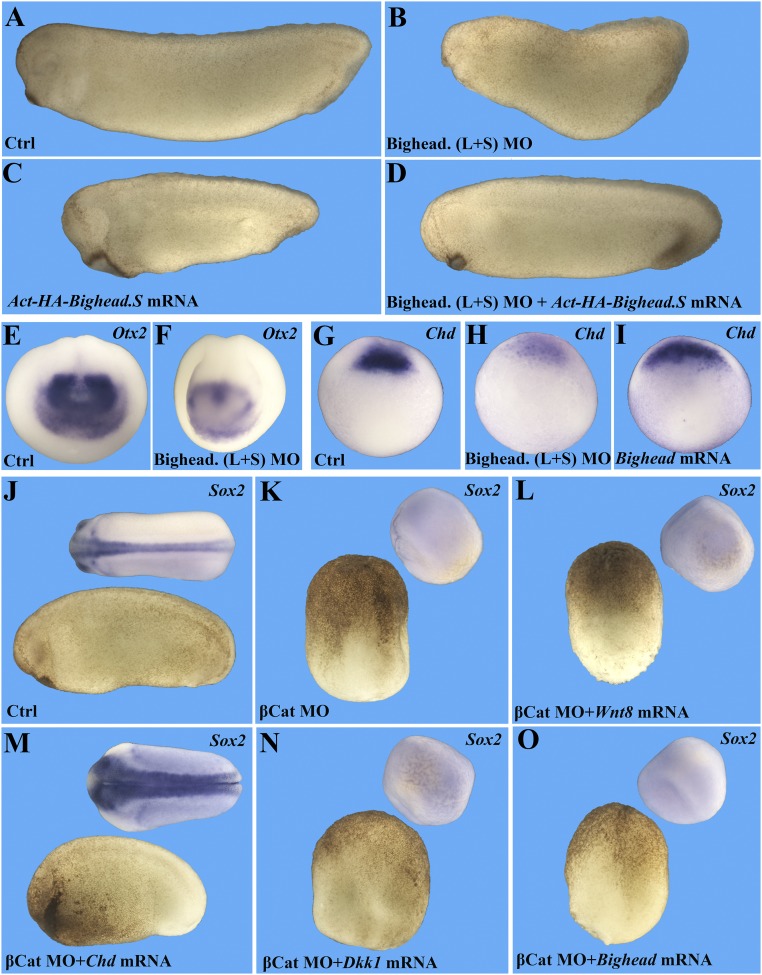

We then examined the knockdown phenotype in vivo by injecting Bighead.L and Bighead.S MOs, individually or in combination, into the dorsal blastomeres of four-cell–stage embryos (targeting the two dorsal injections produced stronger phenotypes and was less toxic than injections into all four blastomeres). Compared with controls, morphant embryos displayed microcephaly and expanded ventral tissues (compare Fig. 4 A and B). In the most affected cases, the head was absent (SI Appendix, Fig. S5J). Importantly, the head defects induced by Bighead knockdown could be rescued by MO-resistant HA-Bighead.S mRNA, indicating that these phenotypes were due specifically to Bighead depletion (Fig. 4 C and D). Interestingly, no defects on head development were observed when the MOs were injected ventrally (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 G and I), the region in which Bighead was less expressed. Consistent with the reduced head phenotype, Bighead MOs decreased the expression of the forebrain marker Otx2 (Fig. 4 E and F).

Fig. 4.

Bighead is required for head development in a BMP-independent way. All embryo pictures were taken at 25× magnification. (A–D) Bighead knockdown inhibits head formation, which is rescued by coinjection of MO-resistant Bighead mRNA. Embryos were injected two times dorsal-marginal at the four-cell stage as indicated and collected at the tailbud stage. The dosages for MO and mRNA were as follows: 32 ng of Bighead (L+S) MOs (directed against the L and S Bighead genes) and 800 pg of Act-HA-Bighead.S mRNA. Numbers of embryos analyzed were as follows: Controls (Ctrl), n = 153, 100% normal; Bighead MOs, n = 122, 93% with a small head phenotype; MO-resistant HA-Bighead mRNA, n = 109, 95% with a dorsalized phenotype; rescue by coinjection of MO and Bighead mRNA, n = 94, 87% rescued. (E and F) In situ hybridization for Otx2 confirming that Bighead knockdown inhibits forebrain development. Embryos were injected two times dorsal-marginal at the four-cell stage with 32 ng of Bighead MO and collected at stage 15. Ctrl, n = 35, 100% normal; Bighead mRNA, n = 48, 83% with enlarged brain phenotype. (G) Expression of the organizer marker chordin at gastrula stage 10.5. (H) Chordin expression was decreased by Bighead MOs. (I) Chordin expression was increased by injection of 800 pg of Bighead mRNA into the animal pole. Note the reduction of Chordin by Bighead MO (n = 34, 100% with phenotype) and expansion of Chordin by Bighead mRNA (n = 47, 93% with increased chordin). (J–O) Experiments with β-catenin–depleted embryos demonstrating that Bighead is not a BMP antagonist but, instead, behaves as a Wnt antagonist. (K) Embryos were injected with 24 ng of β-catenin MO four times into the marginal-vegetal region at the two-cell stage. Then, at the four-cell stage, one dorsal-marginal cell was injected with 1 pg of xWnt8 mRNA (L), 100 pg of Chordin mRNA (M), 50 pg of Dkk1 mRNA (N), or 400 pg of Bighead mRNA (O). Embryos were collected for in situ hybridization with the neural marker Sox2 at stage 18. Note that β-catenin MO completely ventralized embryos and that only the BMP antagonist Chordin could rescue an axis. xWnt8 mRNA was entirely inactive in β-catenin–depleted embryos, as were Dkk1 and Bighead. Numbers of embryos analyzed were as follows: J, n = 47, 100%; K, n = 52, 100% with a ventralized phenotype; L, n = 29, 100% ventralized; M, n = 34, 92% with rescued CNS; N, n = 29, 97% ventralized; O, n = 32, 97% completely ventralized.

The phenotype of Bighead depletion resembled the ventralization caused by knockdown of the BMP antagonist Chordin, with a small head and expanded ventral-posterior tissues (45). This raised the possibility that Bighead depletion might cause the phenotype by increasing BMP signaling rather than by inhibiting Wnt signaling. In fact, microinjection of Bighead MOs decreased Chordin expression, while Bighead mRNA increased it (Fig. 4 G–I). To eliminate the possibility that Bighead was a BMP antagonist (like Chordin), we designed an experiment using β-catenin MO (46). When β-catenin is depleted, Xenopus embryos lack Spemann organizer dorsal mesoderm and all neural development marked by Sox2 (Fig. 4 J and K). In the absence of β-catenin, Wnt8 mRNA microinjection was entirely without effect, as β-catenin protein is required for all transcriptional effects of Wnt (Fig. 4L). In β-catenin–depleted embryos, injection of Chordin mRNA rescued formation of an axis and CNS (Fig. 4M), consistent with the ability of BMP inhibitors to induce dorsal development. In contrast, injection of Dkk1 mRNA was inconsequential in the same setting, and injection of Bighead mRNA behaved like Dkk1 (Fig. 4 N and O). In addition, the microcephaly caused by Bighead MOs was reversed by Dkk1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 K–M), suggesting that these secreted proteins are functionally interchangeable.

Taken together, these results show that Bighead, a Wnt antagonist, is required in vivo for head development.

Bighead Promotes Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 6 Endocytosis and Lysosomal Degradation.

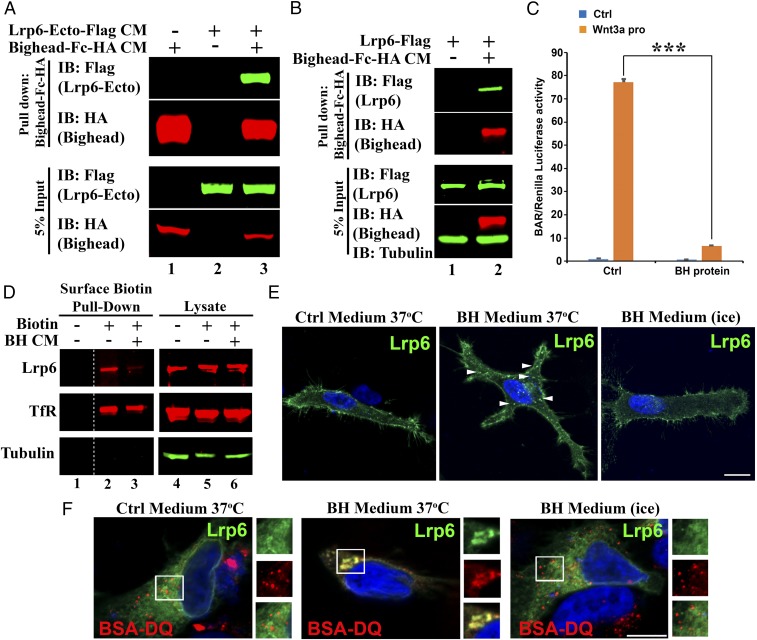

We next examined the molecular mechanism by which Bighead inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Pulldown assays using Bighead-Fc-HA protein and protein A/G agarose beads revealed that Bighead robustly bound with a secreted form of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (Lrp6) Wnt coreceptor consisting of the entire extracellular domain (Fig. 5A), but not to a secreted Cysteine-rich domain of xFrizzled8 (Fz8) or to the ligand xWnt itself (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A, lanes 3, 5, and 7). Bighead-Fc also bound to full-length Lrp6-Flag from solubilized cell lysates (Fig. 5B). Next, we tested the effect of Bighead on Wnt signaling using a stably transfected HEK293T β-catenin–activated reporter (BAR/Renilla) cell line. Both affinity-purified Bighead-Fc protein and Bighead conditioned medium (CM) efficiently inhibited signaling induced by Wnt3a (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). These results indicate that Bighead inhibits Wnt signaling at the extracellular level through its interaction with the Lrp6 coreceptor.

Fig. 5.

Bighead binds to Lrp6 and promotes its endocytosis. (A) Bighead bound to the Lrp6 extracellular domain. CM for a secreted form of LRP6 ectodomain-Flag and Bighead-Fc-HA was allowed to bind as indicated, and subjected to protein A/G agarose pull-down followed by immunoblotting (IB). Total protein expression in the CM was confirmed by IB of the input. (B) Bighead also bound to full-length Lrp6. HEK293T cells transfected with full-length Lrp6-Flag were incubated with control or Bighead-Fc-HA CM for 3 h, and cell lysates were subjected to protein A/G agarose pull-down followed by IB. Total protein expression in the lysate was confirmed by IB of 5% of the input. Tubulin served as a cell lysate loading control. (C) Bighead (BH) protein inhibits Wnt3a protein-induced β-catenin–activated reporter (BAR) reporter expression. HEK293T BAR-Luc/Renilla stably transfected cells were pretreated with or without BH-Fc-HA affinity-purified protein for 6 h, and 100 ng/mL Wnt3a protein was then added to the CM. Cells were further cultured for 16 h, and Luciferase/Renilla activity was measured. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and data are represented as the mean ± SD after normalization to Renilla activity (***P < 0.005). Ctrl, control. (D) BH treatment reduces cell-surface levels of endogenous Lrp6. HEK293T cells were treated with control or BH CM for 1 h at 37 °C, and endogenous cell surface proteins were labeled with sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were subjected to pulldown with Streptavidin-agarose beads followed by IB. Total protein expression in the lysate was confirmed by IB of the input. Transferrin Receptor (TfR) was used as a control receptor that is recycled independent of the Wnt pathway. Tubulin served as a loading control. Note that BH reduced cell surface Lrp6, but not TfR (compare lanes 2 and 3). The dashed line indicates noncontiguous lanes. (E) BH induces LRP6 endocytosis. HeLa cells transfected with LRP6-Flag were treated with Ctrl or BH CM for 1 h at 4 °C or 37 °C as indicated, and processed for immunofluorescence. Arrowheads indicate internalized Lrp6+ vesicles. Note that BH induced Lrp6+ vesicles at 37 °C, but not at 4 °C. Another Lrp6 endocytosis experiment is presented in SI Appendix, Fig. S6D. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (F) BH induces Lrp6 internalization into endolysosomes. HeLa cells transfected with LRP6-Flag were preincubated with BSA-DQ. Cells were then treated with Ctrl or BH CM for 1 h at 37 °C or 4 °C as indicated. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) Squared areas are shown in individual channels as enlarged Insets (1.5× digital enlargement) on the right of each immunofluorescence panel. Note that Lrp6 was endocytosed into lysosomes containing BSA-DQ internalized from the culture medium and that Lrp6 vesicles were eliminated on ice, which prevents endocytosis.

We then asked whether Bighead CM affected Lrp6 localization on the plasma membrane. Cell surface levels of endogenous Lrp6 protein detected by a cell membrane-impermeable Biotin reagent in HEK293T cells on ice were reduced by incubation with Bighead CM for 1 h, followed by pulldown with streptavidin beads (Fig. 5D, compare lanes 2 and 3). In addition, treatment of HEK293T cells for 6 h with Bighead CM, but not with control CM, reduced endogenous Lrp6 protein levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C, lanes 1 and 2). Lrp6 degradation seemed to require lysosome activity, because it was inhibited by a lysosomal inhibitor, Bafilomycin A1, but not by the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C, lanes 3 and 4).

We next tested whether Bighead CM induced the translocation of Lrp6 into intracellular vesicles in an assay using HeLa cells transfected with Lrp6-Flag. With control CM, Lrp6-Flag was found predominantly in the plasma membrane, but it translocated into intracellular vesicles after 1 h of treatment with Bighead CM at 37 °C (arrowheads in Fig. 5E; a 30-min time point is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6D). Importantly, no internalization was observed when cells were incubated on ice, which blocks endocytosis (Fig. 5E, Right). The intracellular Lrp6 vesicles indeed resulted from endocytosis, because they colocalized with BSA-DeQuenched (BSA-DQ) red, a tracer protein that is incorporated into endosomes by non–receptor-mediated endocytosis and fluoresces only after it has been degraded by proteases in the lysosomes (Fig. 5F). Colocalization between BSA-DQ and Lrp6 was observed after 1 h of treatment with Bighead CM at 37 °C, but not on ice (Fig. 5F). Bighead-induced Lrp6 puncta also colocalized with the lysosomal marker Lamp1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6E). These immunolocalization studies on Lrp6-Flag are strongly supported by the more quantitative biochemical assays using cell surface biotinylation (Fig. 5D, lanes 2 and 3) and degradation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C) of endogenous Lrp6 in the presence of Bighead CM.

The results support a molecular mechanism by which Bighead, upon binding to Lrp6, promotes endocytosis and degradation of this receptor in lysosomes. Removal of Lrp6 from the plasma membrane by endocytosis is also observed in the case of two other Wnt antagonists, Dkk1 (47) and Angptl4 (6).

Discussion

The Xenopus Spemann organizer has provided a fertile fishing ground for the discovery of secreted proteins that regulate development. It was expected that new growth factors might be isolated; however, instead, it was found that the Spemann organizer mediates embryonic induction through the secretion of a mixture of growth factor antagonists (4, 5). In the present study, we used deep sequencing to investigate the choice between epidermis and neural tissue.

A Rich Transcriptomic Resource.

The transcriptome of animal cap cells that had been dissociated for several hours (causing neutralization), as well as that of ectodermal explants microinjected with a number of mRNAs that induce neural tissue, such as Chordin, Cerberus, and FGF8, was determined by RNA-seq. We also examined the effect of the endomesoderm inducer Xnr2, the epidermal inducer BMP4, and the mesoderm induction competence modifier xWnt8 (32). These data, which comprise a minimum of 45 × 109 sequenced nucleotides of RNA, are provided in Datasets S1–S3, which can be readily mined by the research community. This constitutes an important open resource for developmental biologists interested in germ layer differentiation.

Isolation of a Wnt Inhibitor.

By searching for neural induction genes activated by cell dissociation (which causes MAPK activation) (19) and by searching for Cerberus, Chordin, and xWnt8 mRNAs, we identified a protein that we designated as Bighead due to its overexpression phenotype. Unexpectedly, this molecule was not expressed in the ectoderm of late gastrula stage 12 when the RNA-seq libraries were prepared. At this stage, Bighead mRNA is expressed in the endoderm, particularly in the dorsal Spemann organizer. Organizer expression is found in the deep endoderm but does not overlap with the leading-edge anterior endoderm (which gives rise to the foregut and liver), which expresses Cerberus and Dkk1 (24, 41). In light of the requirement of Bighead for head development, it appears that Wnt antagonists must emanate also from the most posterior endoderm regions of the organizer to fully empower its head-inducing properties.

It is unlikely that dissociation of animal caps induces endoderm, since the pan-endodermal marker Sox17 is not expressed (Dataset S1). It seems likely that dissociation of animal caps leads to premature activation of the neural domains of Bighead expression, which, in the undisturbed embryo, are observed at later neurula stages. The identification of Bighead was fortunate, because it proved an interesting protein.

Since X. laevis is allotetraploid, Bighead is encoded by two genes from the S and L forms (20). Both encode proteins of about 270 aa with a signal peptide and are secreted. In overexpression experiments, Bighead caused phenotypes very similar to the archetypal Wnt antagonist Dkk1 (41). Bighead mRNA expanded the expression of a number of head markers, blocked expression of the En2 Wnt target gene, prevented secondary axis formation after a single injection of xWnt8 mRNA, and decreased induction of the early Wnt targets Siamois and Xnr3. Further, addition of Bighead protein inhibited canonical Wnt signaling in luciferase reporter gene assays. Thus, Bighead behaves as a canonical Wnt signaling antagonist, many of which are known to promote development of the head (48).

Extensive searches for homologs of Bighead in other organisms showed that it is only present in fish and amphibians. For example, in zebrafish, Bighead corresponds to LOC571755, a protein of unknown function. The protein evolved rapidly, but its six cysteines were conserved throughout many species. SWISS-MODEL prediction suggests that the C-terminal region of Bighead is compatible with the crystal structure of the prodomain of TGF-βs such as myostatin/GDF8 (38, 40); perhaps part of Bighead derived from a structural domain in the proregion of an ancient TGF-β.

No homologs were found in reptiles, birds, or mammals. Gene loss is very common during evolution. For example, we have described an ancient self-organizing network of Chordin/BMP/Tolloid that regulates D/V patterning in vertebrates and invertebrates (49). However, despite this deep conservation, some components of the network were lost. Anti-dorsalizing morphogenetic protein (ADMP) is a BMP that was lost in the platypus (Ornithorhynchus) (50). The sFRPs Crescent and Sizzled are present in birds and the platypus, but not in higher mammals, which have lost the egg yolk. In addition, sFRPs are not present in any invertebrates (51). It appears that the embryonic requirement for the level of regulation provided by Bighead was lost together with the invention of the amnion. Despite this, our studies with Bighead depletion by MOs demonstrate a remarkably strong requirement for this gene in head formation during frog development.

Why so Many Wnt Antagonists?

Bighead adds to a large list of secreted Wnt antagonists. These include the Dkk proteins (48), sFRPs, Wnt-inhibitory factor 1 (WIF-1) (52), SOST/Sclerostin (53), Notum (a hydrolase that removes palmitoleoylate from Wnt in the extracellular space) (54), and Angptl4 (6). In addition, transmembrane proteins such as Shisa (a protein involved in trafficking of Frizzled receptor to the cell surface) (55), Tiki (a protease that cleaves the amino terminus of Wnts) (56) and Znrf3/RNF43 (a ubiquitin ligase that targets Frizzled and Lrp6 receptors for lysosomal degradation) (57, 58) down-regulate Wnt signaling.

As shown in this study, Bighead binds to Lrp6, inducing its rapid endocytosis into lysosomes. As a result, Lrp6 is removed from the surface of the cell and degraded in endolysosomes. This molecular mechanism is very similar to that of the Wnt antagonists Dkk1 and Angptl4. Dkk1 binds to Lrp6 and Kremen1/2, and the complex is internalized. Angptl4 is a secreted protein best known for its role as an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), the key enzyme in the removal of triglycerides from blood plasma (59). Studies in Xenopus have shown that Angptl4 binds to cell surface syndecans (which are transmembrane proteoglycans) and that this interaction triggers endocytosis of Lrp6 (6). In the case of Bighead, it is not known whether a coreceptor is required for Lrp6 internalization. What is clear, however, is that these three Wnt antagonists lead to the internalization of Lrp6 into an endolysosomal population that is not involved in signal generation.

The existence of so many regulators underscores the rich complexity of the Wnt signaling pathway. We usually think of canonical Wnt as a signal that merely increases nuclear β-catenin levels to regulate transcription by T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF). However, Wnt has additional effects. For example, in Wnt-dependent stabilization of proteins, hundreds of cellular proteins become stabilized, leading to an increase in the size of the cell (60, 61). This is caused by the sequestration of GSK3 inside late endosomes/multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (62, 63), decreasing the phosphorylation of phosphodegrons in cytosolic proteins that normally lead to their degradation in proteasomes. In addition to GSK3, another important cytosolic enzyme, protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1), is sequestered inside MVBs when the Wnt coreceptors are endocytosed together with their Wnt ligand (64). The recent realization that Wnt3a greatly stimulates non–receptor-mediated endocytosis of BSA-DQ from the extracellular medium (64) suggests that Wnt is a major regulator of membrane trafficking. We propose that Lrp5/6 is a major regulator not only of the trafficking of Wnts but also of the overall cellular fluid and nutrient uptake. Endocytosis is a universal cellular property that could be regulated by Dkk1, Angptl4, and Bighead. Much remains to be learned about the physiology of the remarkable Wnt signaling pathway (65, 66).

Materials and Methods

Embryo Manipulations.

X. laevis frogs were purchased from the Nasco Company. Embryos were obtained through in vitro fertilization and cultured in 0.1× Marc’s modified Ringer’s solution and staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber (23).

For animal caps cell dissociation, animal caps were dissected at stage 9 from uninjected embryos. Cell dissociations were performed in Ca2+, Mg2+ free 1× Steinberg’s solution [58 mM NaCl, 0.67 mM KCl, 4.6 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mg/L kanamycin] containing 0.1% BSA at stage 9. The outer layer of cells was discarded, and the inner layer was disaggregated into a single-cell suspension by gentle pipetting. All steps were carried out in 35 × 10-mm plastic plates (Fisher) coated with 6% PolyHema (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) in ethanol (Polysciences) and allowed to dry for 30 min.

To prepare animal caps injected with mRNAs, the following doses of mRNA were injected into all cells into the animal region at the four-cell stage: 12 pg of xWnt8, 200 pg of xBMP4, 200 pg of xFGF8, 400 pg of xChordin, and 100 pg of Xnr2. Animal caps were dissected at stage 9.

For both dissociated animal caps and intact animal caps injected with or without mRNAs, samples were collected for RNA-seq at stage 12. Differential gene expression analysis on dissociated animal caps and mRNA-injected animal caps was performed using intact animal caps as a control. The animal cap dissociation experiment was performed in triplicate. The mRNA-injected animal caps and the first animal cap dissociation experiment shown in Fig. 1B were performed from the same clutch of embryos and shared the same uninjected animal cap control, as indicated in Datasets S1 and S3.

cDNA Library Preparation, RNA Sequencing, and Data Analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from animal caps injected with or without mRNAs or dissociated animal cap cells using an Absolutely RNA Miniprep Kit (Agilent). RNA sequencing and data processing were as described previously (21, 22). All RNA-seq data reported in this paper have been deposited in the GEO database (accession no. GSE106320).

Cloning.

The X. laevis genome contains two Bighead alleles: Bighead.L (LOC100494211.L) and Bighead.S (LOC100494211.S). To clone the full length of Bighead or mutant Bighead without signal peptide (ΔBighead), forward and reverse PCR primers were designed according to the genomic sequences deposited in Xenbase (www.xenbase.org/entry/). These oligos also contained upstream sequences for Gateway-mediated cloning. PCR was performed on cDNA of stage 10.5 X. laevis embryos, resulting in an amplification product migrating at the expected size. The PCR product was purified, cloned in a pDonr221 vector, and cloned subsequently in a homemade Gateway-compatible pCS2 vector containing HA, Flag, or IgG Fc tags suitable for antisense probe and mRNA in vitro synthesis.

Protein A/G Agarose Pulldown Assays.

Conditioned media were prepared from cells transfected with pCS2-Lrp6-Ecto-3XFlag (consisting of the Lrp6 extracellular domain), pCS2-xWnt8-Flag, or pCS2-Fz8-CRD-Flag (Frizzled 8 extracellular domain/cysteine-rich domain). Media were collected 48–72 h after transfection and incubated with Bighead-Fc-HA CM as indicated, overnight at 4 °C. Pulldown was performed with the media using protein A/G PLUS agarose beads (sc-2003; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). In addition, to confirm the interaction between Bighead and full-length Lrp6, HEK293T cells were transfected with pCS2-Lrp6-3XFlag. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells in 12-well plates were incubated with control or Bighead-Fc-HA medium for 3 h at 37 °C, washed twice in PBS, and lysed in 400 μL of TNE lysis buffer (Tris-NaCl-EDTA, 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). Pulldown was then performed with 300 μL of the cell lysates using protein A/G PLUS agarose beads. Protein A/G PLUS agarose beads were incubated with media or cell lysate for 3 h at 4 °C with head-over-head rotation. Beads were then washed in lysis buffer at least three times and finally heated for 5 min at 95 °C in 60 μL of 2× Laemmli buffer to elute protein complexes, followed by analysis through SDS/PAGE and Western blotting.

mRNA and MO Injections.

For in vitro mRNA synthesis, pCS2-Bighead.L-HA, pCS2-Bighead.S-HA, pCS2-Bighead.S-Flag, pCS2-ΔBighead.L-HA, pCS2-ΔBighead.S-HA, pCS2-Act-HA-Bighead.S, pCS2-xWnt8, pCS2-xDkk1, pCS2-xChrd, pCS2-xFGF8, pCS2-xCerburus, pCS2-Xnr2, and pCS2-BMP4 were linearized with NotI and transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase using an Ambion mMessage mMachine kit. For Figs. 3 and 4 and Figs. S3–S5, the amount of mRNAs injected per embryo is indicated in the corresponding figure legends. Xenopus β-catenin antisense MO oligonucleotide has been described previously (46). Bighead MOs were designed and synthesized by Gene Tools. Bighead.L MO was as follows: 5′-ATATCCCGAGCCAAACTGTAGCCAT-3′. Bighead.S MO was as follows: 5′-ATCCAGAGCCAAACTGTACCCATCT-3′. Bighead.L MO, Bighead.S MO, or a mixture of both (32 ng per embryo) was injected two times into the marginal region of the two dorsal blastomeres at the four-cell stage. Injection into all four blastomeres produced similar phenotypes but more toxicity.

Heat Maps, PCA, and Statistical Analyses.

Heat maps were generated in R-Studio. For Fig. 1B, logarithmic fold changes were used as inputs. Fold changes were obtained by dividing the RPKM of one gene by its expression in another condition. The rows/genes were left unclustered, as were the columns/conditions. GSEA was performed using GSEA software from the Broad Institute (software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp) (35). Statistical significance was measured with a permutation-based Kolmogorov–Smirnoff nonparametric rank test (1,000 permutations). PCA was generated in R-Studio by comparing log2 fold change in all libraries for transcripts identified in our dissociation gene signature. The statistical significance of differences in gene expression levels between pairwise sets of genes was tested using the Mann–Whitney U test and indicated as *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.005.

Discussion of additional methods, including RT-qPCR, sequence alignments, cell culture, Western blots, CM preparation, immunofluorescence, and cell surface Biotin labeling, is available in SI Appendix, Supplemental SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the E.M.D.R. laboratory for comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Kelvin Zhang and Dr. Pengpeng Liu for bioinformatics instruction. This work was supported by the Norman Sprague Endowment and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, of which E.M.D.R. is an investigator. E.A.S. was supported by the MARC program (Grant NIH T34 GM008563-21), and L.S. was supported by Grant NIH R01 GM123126.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE106320).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1812117115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Spemann H, Mangold H. Induction of embryonic primordia by implantation of organizers from a different species. Roux’s Arch Entwicklungsmech Org. 1924;100:599–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spemann H. 1938. Embryonic Development and Induction (Yale Univ Press, New Haven, CT), reprinted (1967) (Hafner Publishing Company, New York)

- 3.De Robertis EM, Kuroda H. Dorsal-ventral patterning and neural induction in Xenopus embryos. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:285–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.011403.154124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harland R, Gerhart J. Formation and function of Spemann’s organizer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:611–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Robertis EM. Spemann’s organizer and the self-regulation of embryonic fields. Mech Dev. 2009;126:925–941. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsch N, et al. Angiopoietin-like 4 is a Wnt signaling antagonist that promotes LRP6 turnover. Dev Cell. 2017;43:71–82.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasai Y, Lu B, Steinbeisser H, De Robertis EM. Regulation of neural induction by the Chd and Bmp-4 antagonistic patterning signals in Xenopus. Nature. 1995;376:333–336. doi: 10.1038/376333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson SI, Edlund T. Neural induction: Toward a unifying mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1161–1168. doi: 10.1038/nn747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern CD. Induction and initial patterning of the nervous system - the chick embryo enters the scene. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:447–451. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pera EM, Ikeda A, Eivers E, De Robertis EM. Integration of IGF, FGF, and anti-BMP signals via Smad1 phosphorylation in neural induction. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3023–3028. doi: 10.1101/gad.1153603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demagny H, Araki T, De Robertis EM. The tumor suppressor Smad4/DPC4 is regulated by phosphorylations that integrate FGF, Wnt, and TGF-β signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;9:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang C, Harland RM. Neural induction requires continued suppression of both Smad1 and Smad2 signals during gastrulation. Development. 2007;134:3861–3872. doi: 10.1242/dev.007179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson SI, et al. The status of Wnt signalling regulates neural and epidermal fates in the chick embryo. Nature. 2001;411:325–330. doi: 10.1038/35077115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barth LG. Neural differentiation without organizer. J Exp Zool. 1941;87:371–383. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtfreter J. Neural differentiation of ectoderm through exposure to saline solution. J Exp Zool. 1944;95:307–343. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurtado C, De Robertis EM. Neural induction in the absence of organizer in salamanders is mediated by MAPK. Dev Biol. 2007;307:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson PA, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Induction of epidermis and inhibition of neural fate by Bmp-4. Nature. 1995;376:331–333. doi: 10.1038/376331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muñoz-Sanjuán I, Brivanlou AH. Neural induction, the default model and embryonic stem cells. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:271–280. doi: 10.1038/nrn786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroda H, Fuentealba L, Ikeda A, Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Default neural induction: Neuralization of dissociated Xenopus cells is mediated by Ras/MAPK activation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1022–1027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1306605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Session AM, et al. Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature. 2016;538:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature19840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of dorsal and ventral transcriptomes of the Xenopus laevis gastrula. Dev Biol. 2017;426:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding Y, et al. Spemann organizer transcriptome induction by early beta-catenin, Wnt, Nodal, and Siamois signals in Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E3081–E3090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700766114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. 1967. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin): A Systematic and Chronological Survey of the Development from the Fertilized Egg till the End of Metamorphosis (North-Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam), reprinted (1994) (Garland Publishing, Inc., New York)

- 24.Bouwmeester T, Kim S, Sasai Y, Lu B, De Robertis EM. Cerberus is a head-inducing secreted factor expressed in the anterior endoderm of Spemann’s organizer. Nature. 1996;382:595–601. doi: 10.1038/382595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piccolo S, et al. The head inducer Cerberus is a multifunctional antagonist of Nodal, BMP and Wnt signals. Nature. 1999;397:707–710. doi: 10.1038/17820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christian JL, Moon RT. Interactions between Xwnt-8 and Spemann organizer signaling pathways generate dorsoventral pattern in the embryonic mesoderm of Xenopus. Genes Dev. 1993;7:13–28. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardcastle Z, Chalmers AD, Papalopulu N. FGF-8 stimulates neuronal differentiation through FGFR-4a and interferes with mesoderm induction in Xenopus embryos. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1511–1514. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00825-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osada SI, Wright CV. Xenopus nodal-related signaling is essential for mesendodermal patterning during early embryogenesis. Development. 1999;126:3229–3240. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones CM, Dale L, Hogan BL, Wright CV, Smith JC. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP-4) acts during gastrula stages to cause ventralization of Xenopus embryos. Development. 1996;122:1545–1554. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Regulation of ADMP and BMP2/4/7 at opposite embryonic poles generates a self-regulating morphogenetic field. Cell. 2005;123:1147–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasai Y, De Robertis EM. Ectodermal patterning in vertebrate embryos. Dev Biol. 1997;182:5–20. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon RT, Christian JL. Competence modifiers synergize with growth factors during mesoderm induction and patterning in Xenopus. Cell. 1992;71:709–712. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90545-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pera EM, De Robertis EM. A direct screen for secreted proteins in Xenopus embryos identifies distinct activities for the Wnt antagonists Crescent and Frzb-1. Mech Dev. 2000;96:183–195. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waterhouse A, et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Remmert M, Biegert A, Hauser A, Söding J. HHblits: Lightning-fast iterative protein sequence searching by HMM-HMM alignment. Nat Methods. 2011;9:173–175. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotton TR, et al. Structure of the human myostatin precursor and determinants of growth factor latency. EMBO J. 2018;37:367–383. doi: 10.15252/embj.201797883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi M, et al. Latent TGF-β structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinck AP, Mueller TD, Springer TA. Structural biology and evolution of the TGF-β family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8:a022103. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glinka A, et al. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature. 1998;391:357–362. doi: 10.1038/34848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leyns L, Bouwmeester T, Kim SH, Piccolo S, De Robertis EM. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell. 1997;88:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McMahon AP, Moon RT. Ectopic expression of the proto-oncogene int-1 in Xenopus embryos leads to duplication of the embryonic axis. Cell. 1989;58:1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blum M, De Robertis EM, Wallingford JB, Niehrs C. Morpholinos: Antisense and sensibility. Dev Cell. 2015;35:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oelgeschläger M, Kuroda H, Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Chordin is required for the Spemann organizer transplantation phenomenon in Xenopus embryos. Dev Cell. 2003;4:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heasman J, Kofron M, Wylie C. Beta-catenin signaling activity dissected in the early Xenopus embryo: A novel antisense approach. Dev Biol. 2000;222:124–134. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mao B, et al. Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2002;417:664–667. doi: 10.1038/nature756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cruciat CM, Niehrs C. Secreted and transmembrane wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a015081. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bier E, De Robertis EM. EMBRYO DEVELOPMENT. BMP gradients: A paradigm for morphogen-mediated developmental patterning. Science. 2015;348:aaa5838. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warren WC, et al. Genome analysis of the platypus reveals unique signatures of evolution. Nature. 2008;453:175–183, and erratum (2008) 455:256. doi: 10.1038/nature06936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Robertis EM. Evo-devo: Variations on ancestral themes. Cell. 2008;132:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsieh JC, et al. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activities. Nature. 1999;398:431–436. doi: 10.1038/18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Semënov M, Tamai K, He X. SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26770–26775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X, et al. Notum is required for neural and head induction via Wnt deacylation, oxidation, and inactivation. Dev Cell. 2015;32:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamoto A, Nagano T, Takehara S, Hibi M, Aizawa S. Shisa promotes head formation through the inhibition of receptor protein maturation for the caudalizing factors, Wnt and FGF. Cell. 2005;120:223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X, et al. Tiki1 is required for head formation via Wnt cleavage-oxidation and inactivation. Cell. 2012;149:1565–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hao HX, et al. ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature. 2012;485:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature11019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koo BK, et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 2012;488:665–669. doi: 10.1038/nature11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang R. The ANGPTL3-4-8 model, a molecular mechanism for triglyceride trafficking. Open Biol. 2016;6:150272. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Acebron SP, Karaulanov E, Berger BS, Huang YL, Niehrs C. Mitotic wnt signaling promotes protein stabilization and regulates cell size. Mol Cell. 2014;54:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim H, Vick P, Hedtke J, Ploper D, De Robertis EM. Wnt signaling translocates Lys48-linked polyubiquitinated proteins to the lysosomal pathway. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taelman VF, et al. Wnt signaling requires sequestration of glycogen synthase kinase 3 inside multivesicular endosomes. Cell. 2010;143:1136–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vinyoles M, et al. Multivesicular GSK3 sequestration upon Wnt signaling is controlled by p120-catenin/cadherin interaction with LRP5/6. Mol Cell. 2014;53:444–457. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Albrecht LV, Ploper D, Tejeda-Muñoz N, De Robertis EM. Arginine methylation is required for canonical Wnt signaling and endolysosomal trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E5317–E5325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804091115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loh KM, van Amerongen R, Nusse R. Generating cellular diversity and spatial form: Wnt signaling and the evolution of multicellular animals. Dev Cell. 2016;38:643–655. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.