Abstract

Introduction:

Cabozantinib is a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that initially showed activity in medullary thyroid cancer and was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma after progression on first line therapy.

Areas Covered:

In the METEOR trial, cabozantinib demonstrated significantly improved efficacy in all three endpoints; response rates, progression free survival and overall survival in a randomized trial with everolimus as an active comparator. Cabozantinib also showed activity in the front line setting in RCC within the CABOSUN trial. The study randomized untreated metastatic RCC patients to either cabozantinib or sunitinib and the former showed improved progression free survival which was the primary endpoint. The future holds promise for indications in other malignancies, given the preliminary efficacy and unique mechanism of action of cabozantinib.

In this review we address the mechanism of action, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of cabozantinib, and also review the development pathway of this agent in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. The potential benefit in specific patient populations, such as poor risk patients and bone metastases subgroups is also discussed.

Expert Commentary:

The clinical applications of cabozantinib will be addressed within the context of the current competitive therapeutic landscape of RCC.

Keywords: cabozantinib, Renal cell carcinoma, targeted therapy, RCC, METEOR, MET, CABOSUN

1. Introduction

Kidney and renal pelvis cancer cases constitute 4% of all new cancer cases in the United States and the disease was responsible for more than 14 thousand cancer deaths comprising about 2% of all cancer deaths in 2016. 70–80% of kidney cancers demonstrate clear cell histology and about 16% present with metastatic disease at diagnosis and 30% of localized cases will recur after resection [1–2].

Over the course of the last decade eight new treatments were approved for advanced renal cell carcinoma encompassing three main mechanisms of action; namely antiangiogenic therapy, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition therapy and immune therapy. One of these is a targeted agent called cabozantinib, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April of 2016 [3].

Cabozantinib/XL184 (Exelixis, Inc.) is a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2, MET and rearranged during transfection (RET) as well as KIT, AXL, and FLT3. All of these pathways have been found to be important for tumor growth, angiogenesis, survival and metastasis in multiple tumor types [4].

Isolated inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) without MET, leads to increased tumor growth and metastasis as seen in multiple animal models most notably reported in the work of Pàez-Ribes et al. [5] The hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and MET pathways have been implicated in resistance to VEGFR inhibitors like sunitinib, as noted in multiple preclinical studies [6]. A dual inhibition of VEGFR and MET provides a method to overcome VEGFR inhibitor resistance as well as reinduces antitumor effect. This phenomenon was initially observed and reported in preclinical animal models [7] and now has proven clinical antitumor efficacy in a randomized trial conducted in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) population pretreated with anti angiogenic therapy [8, 9]. Additionally, the inhibition of Axl by cabozantinib results in impaired angiogenesis and enhancement of antiangiogenic effect [10]. This review is written with a view to discuss the clinical data and the detailed pharmacokinetics and dosing and drug interactions of cabozantinib to enable safe and optimal use of the medication.

2. Importance of VEGF pathway in RCC:

Angiogenesis is a hallmark of cancer development. In tumors, angiogenesis is frequently induced by tumor hypoxia that is caused by rapid tumor proliferation and poorly developed blood vessels. For example mean Partial pressure of Oxygen (PO2) in breast cancer tissue is 10 mmHg as compared to 65 mmHg in normal breast tissue [8]. In RCC the pathologic cause for angiogenesis is the inactivation of Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene on chromosome 3p25. This is commonly associated with overexpression of VEGF and leads to activation of hypoxia inducible factors like HIF-1α and HIF 2α, which stimulate blood vessel formation and promote tumor proliferation and metastasis. There are more than 800 target genes of HIF and the most important one is VEGF. Loss of tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 3p is frequently implicated in sporadic cases of clear cell RCC [9]. Some examples of other gene alterations involved in RCC pathogenesis include BRCA1-associated protein1, SET domain-containing 2, and polybromo 1.

Understanding the molecular features of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) gave rise to anti-VEGFR small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) development as front line therapies in advanced RCC. Agents like sunitinib and pazopanib have proven efficacy and are well accepted therapies for RCC[11–13]. Although these therapies are effective for a median time interval of nine to eleven months, majority of the patients demonstrate progression and resistance to anti-VEGF therapy. This led to a need for subsequent therapy options. A mTOR inhibitor, everolimus was the first agent to demonstrate a modest benefit in that space, with a median progression free survival of only 4.5 months and a response rate of 3% [14]. Clearly there remained an unmet need for more effective therapies post anti-VEGF therapy.

3. HGF/MET pathway:

MET tyrosine kinase receptor is expressed on the surface of epithelial and endothelial cells and is bound by HGF, an inactive serine protease analog [5]. Both are responsible for multiple physiological functions involving organogenesis in embryonic development and adult tissue regeneration. In cancer thses are implicated in proliferation, cell differentiation, cytoskeletal rearrangement, apoptosis protection and cell invasion [15].

In papillary RCC, both germline and somatic mutations in the MET proto-oncogene are described [16] and higher level of expression of MET was associated with worse outcomes in clear cell and non-clear cell RCC [17].

Combined VEGFR-2 and MET inhibition was first studied in a clinical trial in papillary RCC reported by Choueiri et al, evaluating foretinib [18]. In another study conducted in two animal models, one anti-VEGFR TKI (sunitinib) resistant and the other sensitive, combined blockade of both VEGF and HGF/MET pathways enhanced the anti-tumor effect in both models. This effect was found irrespective of MET expression [19]. In the same study it is worth noting that in sunitinib resistant model; MET expression was significantly increased, which highlights HGF/MET pathway as an important mechanism of resistance to antiangiogenesis therapy. Other studies also demonstrate the HGF/MET pathway as the culprit in antiangiogenesis therapy resistance [6]. With overwhelming preclinical rationale, clinical assessment of combined blockade of VEGFR and HGF/MET pathways was a logical step in both TKI resistant and naïve patients. Inhibition of Axl by Cabozantinib impairs tube formation hence increasing anti angiogenic effect, and has direct apoptotic effects on tumor cells [10]. The distinct mechanism of action holds the promise of overcoming resistance to anti-VEGF TKI therapies such as sunitinib and pazopanib. The preclinical results were noteworthy and led to multiple clinical trials evaluating the clinical efficacy of cabozantinib in advanced RCC.

4. Cabozantinib drug development:

Cabozantinib was first studied in murine cancer models of breast cancer, lung cancer, medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) as well as prostate cancer [4,20, 21]. A phase I dose escalation trial in medullary thyroid cancer concluded that the maximum tolerated dose was 175 mg per day based on the molecular weight of the salt form which is equivalent to 140 mg of free based drug thus the recommended phase II dose was 140 mg daily of the commercially available preparation called Cometriq [22]. A subsequent phase III study established 140 mg dose in MTC and led to its FDA approval for that indication [23].

In advanced renal cell carcinoma cabozantinib was first studied clinically in heavily pretreated patients and showed a promising activity with a partial response rate of 28%. 25 patients were enrolled in this phase I study, all patients had at least one prior line of therapy of which 88% had anti-VEGF therapy (14 patients were taking sunitinib) and 50% had three or more prior lines of therapy [24].

The dosage of cabozantinib was 140 mg orally daily, which was determined to be the maximum tolerated dose. Twenty-one of 25 patients were in the intermediate risk group per Heng criteria, three were in the poor prognosis category and only one was in the favorable risk category. The response rate in this study was very promising with seven (28 %) achieving partial responses and 13 patients showing stable disease (52 %). Only one patient (4 %) had disease progression. Median progression-free survival was 12.9 months, and median overall survival was 15.0 months. Four patients had bone metastases and, of these, three out of four demonstrated an objective response. Two patients had bone pain and cabozantinib induced significant symptom relief in both. On the basis of this relatively preliminary, but promising efficacy observed in a drug-drug interaction trial in advanced RCC, the plan for a phase III registration trial was formed. The dose level of 60 mg was selected based on a dose de-escalation trial conducted in metastatic prostate cancer that showed comparable efficacy and better tolerability [25].

5. Phase III METEOR Trial (NCT 018657470) [Table 1]

Table 1.

Summary of The METEOR Trial Results With Subgroup Analyses

| Subgroups (no of pts) (cabozantinib/everolimus) | Overall Survival: Median HR (95%CI) | Progression free survival Median HR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Cabozantinib (330) | 21.4 months (18.4-NR) | 7.4 months (5.6–9.1) |

| Everolimus (328) | 16.5 months(14.7–18.8) | 3.8 months (3.7–5.1) |

| HR= 0·66 [0·53–0·83] | HR= 0·58 [0·45–0·75] | |

| MSKCC risk groups | ||

| Favorable (150/150) | 0.66(0.46–0.96) | 0.51(0.38–0.69) |

| Intermediate (139/135) | 0.67(0.48–0.94) | 0.47(0.35–0.65) |

| Poor (41/43) | 0.65(0.39–1.07) | 0.70(0.42–1.16) |

| IMDC risk groups | ||

| Favorable (66/62) | 0.70(0.34–1.41) | 0.47(0.30–0.76) |

| Intermediate (210/214) | 0.65(0.49–0.85) | 0.48(0.37–0.62) |

| Poor (54/52) | 0.74(0.48–1.15) | 0.67(0.48–1.04) |

| Prior Nephrectomy | ||

| No (47/49) | 0.75(0.44–1.27) | 0.51(0.30–0.86) |

| Yes (283/279) | 0.66(0.52–0.84) | 0.51(0.41–0.64) |

| Bone Mets | ||

| No (253/263) | 0.71(0.55–0.91) | 0.57(045–0.71) |

| Yes (77/65) | 0.54(0.34–0.84) | 0.33(0.21–0.51) |

| Number of previous VEGFR TKI | ||

| 1 (235/229) | 0.65(0.50–0.85) | 0.52(0.41–0.66) |

| 2 or more (95/99) | 0.73(0.48–1.10) | 0.51(0.35–0.74) |

| Duration of first VEGFR | ||

| 6 months or less (88/102) | 0.69(0.47–1.01) | 0.62(0.44–0.89) |

| >6 months (242/224) | 0.69(0.52–0.90) | 0.48(0.38–0.62) |

Study Design and eligibility

A pivotal phase III study was conducted in advanced RCC patients, pretreated with VEGFR inhibitor therapy. Patients were required to have a clear cell component, performance status of 0–2 and adequate liver, renal and bone marrow function. In this open-label, randomized phase 3 trial, adult patients with advanced or metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma, measurable disease, and previous treatment with one or more VEGFR tyrosine-kinase inhibitors were randomized to receive oral 60 mg cabozantinib daily, or 10 mg everolimus once a day. Stratification factors consisted of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center risk group, and number of prior therapies with VEGFR tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival as assessed by an independent radiology review committee in the first 375 randomly assigned patients with an anticipated hazard ratio of 0.667, and the study was expanded to a total of 658 patients to evaluate the OS endpoint [26–27]. Secondary endpoints consisted of objective response rate and safety profile.

Cabozantinib treatment resulted in a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (HR 0·51 [95% CI 0·41–0·62]; p<0·0001) and objective response rate of 17% [95% CI 13–22%] as compared to 3% [95% CI 2% −6 %] with everolimus (p<0·0001) per independent radiology review. Median PFS was 7.4 months with cabozantinib as compared to that with everolimus was 3.8 months. The median duration of follow-up for OS and safety at last report was 18·7 months. Median overall survival was 21·4 months (95% CI 18·7–not estimable) with cabozantinib and 16·5 months (14·7–18·8) with everolimus (hazard ratio [HR] 0·66 [95% CI 0·53–0·83]; p=0·00026).

Predominant adverse events reflected the anti VEGF activity of cabozantinib. The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were hypertension 15%, diarrhea 13%, fatigue 11%, hand foot syndrome 8%, anemia 6%, hyperglycemia 1% and hypomagnesaemia 5%. Serious adverse events grade 3 or worse occurred in 130 (39%) patients in the cabozantinib group and in 129 (40%) in the everolimus group. One treatment-related death occurred in the cabozantinib group of unclear etiology and two deaths were noted in the everolimus group (one aspergillus infection and one aspiration pneumonia). Other significant side effects include dysphonia, stomatitis, headache, dizziness, rash, elevated transaminases, increased serum creatinine and hypothyroidism.

In addition to supportive care and symptom control, dose reduction is an effective way to manage toxicities. The dose levels of cabozantinib are 40 mg daily and 20 mg daily. It is important to note that about 60% of the patients on the METEOR study required dose reductions secondary to side effects.

6. Pharmacodynamics of cabozantinib:

Cabozantinib is a potent inhibitor of VEGFR 2 and MET in multiple tumor models in vivo, and it results in blockade of phosphorylation of oncogenic mutant RET in human xenografts models of medullary thyroid cancer [28]. It also inhibits ROS1, FLT3 and AXL [29].

In preclinical models cabozantinib blocked angiogenesis, metastasis and induced tumor regression in multiple tumor models including RCC, MTC, lung cancer, breast cancer, neuroblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma and gastrointestinal stromal cancers [30].

In the phase III MTC trial the effect of cabozantinib at the 140 mg daily dose on the QTc interval was evaluated. A mean increase in QTc of 10 – 15 ms was observed at 4 weeks after initiating cabozantinib. A concentration and QTc relationship could not be definitively established. Changes in cardiac wave form morphology or new rhythms were not observed. No cabozantinib treated patients in this study had a confirmed QTc > 500 ms and nor did any cabozantinib-treated patients in the RCC study (at a dose of 60 mg)[31].

7. Pharmacokinetics of cabozantinib

Cabozantinib is commercially available in 2 formulations; the capsule called Cometriq is approved for medullary thyroid cancer and the tablet called Cabometyx is approved for metastatic RCC. Cabometyx (tablet, used in RCC) did not meet bioequivalence criteria of 80–125% of Cmax level achieved by Cometriq (capsule used in medullary thyroid cancer). This is likely secondary to differences in rates of absorption in healthy volunteers which were noted to be higher in the tablet formulation than in the capsule by 19% and the upper limit of the confidence interval was 131.5% which lay beyond the range of 125% [32]. In a subsequent study a dose proportional increase in levels was observed with dose escalation ranging from 20mg, 40mg to 60mg daily dose tablets.

Single dose pharmacokinetics were evaluated in 8 patients with mild or moderate liver dysfunction and in 10 patients with mild or moderate renal impairment [33]. Comparisons of levels to matched controls with normal function showed an increase of upto 31% in renal impairment cases and 81% in hepatic dysfunction. No clear trends for increased risk of toxicities were noted but extreme caution and close monitoring for adverse events is advised if cabozantinib is used in patients with mild or moderate renal or liver impairment. In severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, no safety data is available.

A food effect study revealed that a high fat meal can increase the Cmax by about 40% and hence administration in a fasting state (at least 2 hours after and 1 hour before a meal) is recommended.

Proton pump inhibitors did not significantly impact drug levels and hence can be used in conjunction with cabozantinib [34]. Cabozantinib was shown to be substrate for CYP3A4. It was studied with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor; ketoconazole which led to significantly increased plasma levels of cabozantinib. Thus a reduced starting dose is recommended when concurrently administered with a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor. Examples of potent inhibitors are protease inhibitors such as antivirals atazanavir, darunavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir and tipranavir and antifungals like ketoconazole and itraconazole. Of note other moderate inhibitors of CYP3A4 include amiodarone and grape fruit juice. A dose decrease of 20 mg is advised if these medications have to be administered concurrently with Cabozantinib.

Strong inducers of CYP3A4 like rifampin and phenytoin also have a significant effect on reducing cabozantinib levels and possibly decreasing its efficacy. A dose increase by 20 mg in the daily dose is recommended when the patient is anticipating receiving cabozantinib is treated with a concurrent CYP3A4 inducer. Dexamethasone, St Johns wort, nafcillin and carbamazepine are among the other most notable examples of inducers.

Dose modification with co administration of strong inhibitors and inducers of CYP3A4 is specific for the US labeling of Cabozantinib but these drug interactions should be considered during clinical management worldwide.

8. Cabozantinib in Subset Populations of RCC

a. Bone Metastases:

RCC patients with bone metastasis have a particularly poor prognosis. A retrospective analysis of more than 2000 patients with mRCC from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) showed significantly decreased OS and time to treatment failure respectively (Median TTF of 5.7 vs 7.6 months; p < 0.0001) of patients with bone metastases when compared to patients without bone involvement (Median OS of 14.9 vs 25.1 months; p < 0.0001) [35]. Cabozantinib showed activity on tumor xenografts implanted in bone, in preclinical studies [36]. By inhibiting both VEGFR and MET it affects osteoclast and osteoblast function and alters the bone microenvironment. A phase II trial in multiple solid tumors showed that 59 of 68 patients with bone metastases who received cabozantinib had partial or complete bone scan resolution and symptomatic improvement [37]. Similar results were noted on bone scans in metastatic prostate cancer [38]. Within the patients with bone metastases enrolled on the METEOR trial, (77 or 20% randomized to cabozantinib) the hazard ratios of progression and death in comparison to everolimus were 0.54 and 0.31 respectively, which demonstrated a significantly favorable outcome for cabozantinib in this subset of RCC with an otherwise dismal prognosis. [26, 27] In the METEOR trial evaluation of the subset of patients with bone metastases was not preplanned and should be viewed with caution due to small sample size and lack of stratification for this factor. In the CABOSUN trial however presence of bone metastases was a stratification factor along with prognostic risk group per Heng criteria. In the METEOR trial the stratification consisted of Memorial Sloan Kettering criteria risk groups and number of prior anti-VEGF therapies (one versus two or more).

b. Brain metastases:

Multiple ongoing and reported phase I and II trials are evaluating the activity of Cabozantinib in high grade gliomas and brain metastases of various tumor types [39]. Cabozantinib crosses the blood brain barrier and has potential for clinical activity in patients with brain metastases. In whole-brain lysates of non-tumor-bearing mice, cabozantinib attained 20% of peak plasma levels, suggesting its ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. This finding has not been confirmed in human trials [40]. Although the METEOR study allowed stable and treated brain metastases, only three patients with brain metastases were enrolled.

c. Nephrectomy:

In cases without nephrectomy, another patient population that is under-represented in clinical trials and has known poor outcomes, the efficacy of cabozantinib was noted in the 47 patients without nephrectomy that were enrolled. The HR for PFS was 0.51(95% CI.0.30–0.86). The HR for OS was 0.75, also favoring cabozantinib, the 95% confidence interval crossed 1.0 (0.44–1.27). Caution needs to be exercised in drawing conclusions from post hoc subset analyses especially given the sample size limitations.

9. First line treatment of advanced RCC: CABOSUN trial [NCT01835158] [Table 2]

Table 2.

Summary of The CABOSUN Trial Results With Subgroup Analyses

| Median progression free survival (Months) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Total (Cabozantinib/Sunitinib) | Cabozantinib | Sunitinib | HR (95% CI)/pvalue | |

| All patients | 157 (79/78) | 8.2 | 5.6 | 0.66 (0.46–0.95) p=0.012 |

| Poor | 30 (15/15) | 6.1 | 2.8 | 0.75 (0.35–1.65) |

| No | 100 (50/50) | 8.6 | 7.6 | 0.78 (0.48–1.21) |

CABOSUN is a randomized, open-label phase 2 trial that was designed to enroll 150 patients with advanced RCC determined to be intermediate- or poor-risk by the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) criteria [41]. CABOSUN was conducted by The Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology as part of Exelixis’ collaboration with the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (NCI-CTEP). Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive cabozantinib (60 mg once daily) or sunitinib (50 mg once daily, 4 weeks on followed by 2 weeks off). The randomization was stratified by the IMDC risk strata (intermediate or poor risk) and presence of bone metastasis (yes, no). Enrollment was completed in March 2015. The primary endpoint was PFS, defined as time from randomization to disease progression or death, whichever occurs first. Positive PFS results have formed the basis for previous regulatory approvals of treatments in the first-line setting, including sunitinib. Secondary endpoints included overall survival and objective response rate. Eligible patients were required to have locally advanced or metastatic clear-cell RCC, ECOG performance status 0–2, and had to be intermediate or poor risk, per the IMDC Criteria. Prior systemic treatment for RCC was not permitted. With 123 events (disease progression or death), the log-rank statistic has 85 percent power (with a one-sided type I error rate=0.12) to detect a hazard ratio of 0.67. Between July 9, 2013 and April 6, 2015, 157 patients were randomized: 79 patients on the cabozantinib arm and 78 patients on the sunitinib arm. The preliminary results announced in a press release by Exelixis on May 23, 2016 revealed superior efficacy of cabozantinib as compared to sunitinib therapy in the front line setting in clear cell RCC. The data were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in February 2017 [41]. The trial met its primary endpoint, demonstrating a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) for cabozantinib compared with sunitinib in patients with advanced intermediate- or poor-risk RCC. The safety data in the cabozantinib-treated arm of the study were consistent with those observed in previous studies in patients with advanced RCC. The results of this study reveal that Cabozantinib improved RR, and PFS as compared to that achieved with sunitinib in the intermediate and poor risk patient population with clear cell RCC as well as showed a trend towards improvement in OS, although not statistically significant. The 57 patients with bone metastases were evaluated in a preplanned subset analysis and consistently demonstrated a statistically significant hazard ratio of 0.51 for the PFS endpoint, favoring Cabozantinib. [Table 2]. Independent review is ongoing to confirm the response and progression results within CABOSUN and if this confirms the investigator assessed results, then FDA submission of cabozantinib can be anticipated for the front line therapy of metastatic RCC.

The CABOSUN results have the potential to change the entire therapeutic paradigm in advanced RCC where cabozantinib will be used front line and followed by consideration of other VEGFR TKI or immune therapy. However front line immune therapy combination trials are also expected to report results within the next 12 months. Two large randomized trials include the combination of ipilimumab+ nivolumab as compared to sunitinib as the control arm, and the combination of bevacizumab and atezolizumab also compared to sunitinib in untreated advanced RCC. Whether in the front line or second line setting, the dilemma in systemic therapy decisions will remain between the use of immune therapy or TKI based therapy. Predictive biomarkers to help guide therapy will be of critical importance. To date the clinical utility of biomarkers in RCC has been disappointing. The PD-1 expression has not been predictive of nivolumab efficacy. The MET expression has not been predictive of benefit with cabozantinib. Large databases such as IMDC need to be explored to develop clinical biomarkers until molecular biomarkers are validated and reproducible. A clinical trial of cabozantinib and nivolumab, with or without ipilimumab [NCT02496208] in all genitourinary tumors, is active at the National Cancer Institute. The dose escalation phase is ongoing and safety and efficacy of combinations needs to be determined.

10. Cabozantinib in non-clear cell RCC:

Papillary renal cancer (pRCC) constitutes about 10–15% of RCC and usually harbors a MET mutation. Therefore MET inhibition is a logical step and cabozantinib with MET inhibition properties has clear rationale in papillary RCC. Cabozantinib is under investigation in the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOGPAPMET) 1500 trial, which is a phase II trial comparing efficacy of three distinct MET inhibitors; Cabozantinib, Crizotinib and Savolitinib with a control arm of sunitinib in the treatment of metastatic papillary RCC. The study does not select patients based on MET mutations; however testing will be conducted on archival tissue for all patients enrolled. No formal clinical trial testing has been conducted in other non-clear cell histologies such as sarcomatoid, collecting duct, translocation RCC but cabozantinib may be considered for clinical use in the second line setting.

11. The landscape of second line treatment in advanced RCC:

Multiple treatment options exist in patients who progress on first line therapy with antiangiogenic agents which are summarized in table 3.

Table 3.

Randomized Trials in Advanced Renal Cancer Pretreated with VEGFR TKI therapy

| Arms (Ref) | No of pts | MSKCC risk group Fav/Int/poor | ORR | Med PFS (months) | Med OS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everolimus | 272 | 29%/56%/15% | 1% | 4.9 | 14.8 |

| Axitinib | 361 | 28%/37%/35% | 19% | 6.7 | 20.1 |

| Nivolumab | 406 | 35%/49%/16% | 5% | 4.4 | 25 |

| Cabozantinib | 330 | 43%/43%/15% | 17% | 7.4 | 21.4 |

| Lenvatinib+everolimus | 51 | 24%/37%/39% | 43% | 14.6 | 25.5 |

Everolimus (mTOR inhibitor) was the first drug approved in patient who progressed after anti VEGFR TKI therapy with a longer progression free survival when compared with placebo in a phase III clinical study by Motzer et al [14]. This trial involved patients who had disease progression on sunitinib, sorafenib or both. Axitinib which is a potent inhibitor of VEGFR also improved PFS as a second line agent when compared with sorafenib [42]. But the benefit was less profound when first line treatment was the other VEGFR sunitinib when compared with cytokines as first line (median of 1.4 months with sorafenib vs 5.6 months with axitinib).

Combination lenvatinib (a dual inhibitor of VEGFR and FGFR) and everolimus also showed improved PFS (when compared with everolimus only) [43] at the cost of increased incidence of diarrhea, hypertension and fatigue in the combination arm and proteinuria, hypertension and diarrhea in the lenvatinib only arm. The difference in OS was not statistically significant and the clinical outcomes in the single agent lenvatinib arm were not siginificantly different from those in the everolimus arm.

Nivolumab is a fully human IgG4 programmed death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitor antibody demonstrated improved OS but no difference in PFS, when compared to everolimus, in a randomized trial conducted in VEGF pretreated patients with advanced RCC [44].

12. Cabozantinib in other tumor types:

As mentioned in our review cabozantinib has preclinical activity in a multitude of tumor types. This is reflected within the broad range of clinical trials that are currently ongoing evaluating its efficacy in treating multiple malignancies. One of the examples is a recently reported trial of cabozantinib in hepatocellular carcinoma patients who have progressed on prior therapies. Cabozantinib achieved a relatively promising median PFS and OS of 5.2 and 11.5 months, respectively. [45] Trials are ongoing in non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer and hematologic malignancies such as multiple myeloma and acute myeloid leukemia.

13. Conclusions

Cabozantinib is an oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is currently FDA approved in medullary thyroid cancer, and in advanced renal cancer that has progressed after at least one prior anti VEGF therapy. It has revealed superior efficacy in comparison with sunitinib in front line therapy of advanced RCC and is likely to receive FDA approval for this indication. The agent has shown promise across a multitude of other malignancies and is very likely to have other clinical applications in the future.

14. Expert Commentary

Cabozantinib is an oral inhibitor of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, including RET, MET and VEGFR2. This agent has demonstrated an intriguing path in the drug development process. The initial evaluation in medullary thyroid cancer was based on the mechanism of action which included RET inhibition. As only 4% of thyroid cancers are medullary, cabozantinib achieved orphan drug status. The randomized placebo controlled trial in medullary thyroid cancer demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (Median 11.2 vs 4.0 months; P < .0001) and response rates (27% with cabozantinib and 0% in placebo arm). The study results led to FDA approval for advanced medullary thyroid cancer in November 2012. Cabozantinib exhibits anticancer activity through receptor kinase inhibition of metastasis tumor angiogenesis and tumor microenvironment. It affects multiple resistance pathways such as the VEGF. The remarkable responses in bone metastases and normalizing bone scans in metastatic prostate cancer led to two randomized registration trials being launched in metastatic CRPC. Unfortunately both of those studies yielded no evidence of benefit as compared to control arm and despite tremendous promise, FDA approval in metastatic prostate cancer was not translated into reality. The dose evaluated in advanced prostate cancer was 60 mg daily in contrast to the 140 mg daily dose assessed in medullary thyroid cancer. This dose was essential to improve patient tolerability and in the randomized discontinuation trial conducted in prostate cancer appeared to maintain efficacy.

In RCC the phase III trial (METEOR) stemmed from results of response noted in a small drug drug interaction trial. The study showed a promising response rate especially in a pretreated refractory patient group. The promise held by cabozantinib in metastatic RCC was realized by METEOR results and enhanced by the CABOSUN trial. It is ironic that despite the large phase II experience in prostate cancer the phase III trial yielded negative results, in contrast to the trials within RCC where a phase III trial was launched directly after a phase I study and yielded positive results. CABOSUN has demonstrated the potential for efficacy cabozantinib in the frontline metastatic RCC setting. The response rates and PFS are significantly improved in the intermediate and poor risk population enrolled into the study. If the independent response assessment is feasible and confirms the investigator assessed PFS results then it is possible that the medication could receive an indication in frontline advanced RCC.

The rapid drug development in advanced RCC has led to the availability of a number of therapies that have received FDA approval within the last 24 months. The three regimens that were recently approved include, nivolumab, cabozantinib and combination of lenvatinib and everolimus. None of these therapies have been compared to each other and the choice of agent poses a therapeutic dilemma. In the absence of validated biomarkers or genomic tests to guide therapy in RCC the decision is mainly based on clinical assessments. At present the differences in toxicity profiles, the duration and toxicities of prior TKI therapy, presence of brain metastases, immunosuppressive therapies or auto immune conditions are the clinical factors that are taken into account when choosing therapies in the second and third line setting. Clinical and molecular, validated biomarkers are hence urgently needed to guide therapeutic decision making in renal cancer.

Cabozantinib has the potential for drug development across a broad range of malignancies as the mechanism of action encompasses multi targeted effects. Single agent studies are ongoing in triple negative breast cancer, non small cell lung cancer, endocrine malignancies, urothelial cancer, multiple myeloma and brain tumors. The combination studies have stimulated great interest especially those of cabozantinib with either immune checkpoint inhibitors or PT-2385, a HIF-1 alpha inhibitor or with the glutaminase inhibitor, CB-839 in RCC.

15. Five Year View

There is likely to be a paradigm shift in RCC therapy. CABOSUN trial has demonstrated superior PFS and response rates for cabozantinib as compared to sunitinib in untreated intermediate or poor risk RCC. It is likely that cabozantinib will become the front line therapy of choice if independent review confirms the findings and if the agent receives FDA approval. In addition immune based regimens such as the combinations of nivolumab + ipilimumab, and bevacizumab + atezolizumab are phase III trials that have completed enrollment, comparing each of these regimens to sunitinib, and results are awaited. In the future the nuances of eligibility in each of these trials, and patient comorbidities will remain important factors. Consequently a domino effect will alter the second and third line therapies. The questions of optimal sequencing, and predictive biomarkers, for patients who are eligible for both therapies need to be incorporated in future clinical trials within RCC. Ultimately, increasing the complete remission rate should be the main goal to aspire to in this terminal condition.

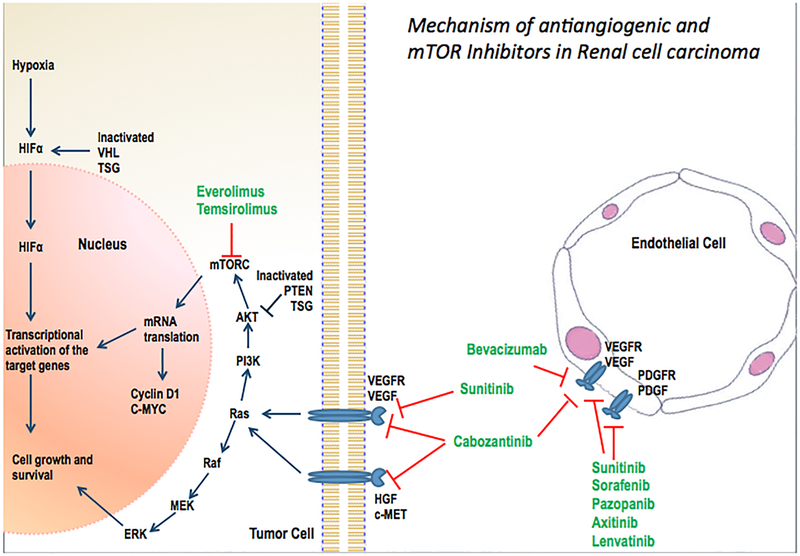

Figure 1.

Mechanism of antiangiogenic and mTOR inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma.

Information Resources:

-

1)

METEOR Trial report: Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1814–23. The registration trial that established the efficacy of Cabozantinib as compared to everolimus in pretreated advanced kidney cancer.

-

2)

CABOSUN: Choueiri TK, Halabi S, Sanford BL, et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma of poor or intermediate risk: The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Nov 14:JCO-2016. Phase II randomized trial of Cabozantinib compared to sunitinib in the front line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors were supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grant P30 CA022453

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

U Vaishampayan has received research support, and honoraria from Exelixis Inc. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References:

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Kidney and Renal Pelvis. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/kidrp.html.

- [3]. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm497483.htm.

- [4].Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Molecular cancer therapeutics.;10:2298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pàez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T,et al. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer cell. 2009;15:220–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shojaei F, Lee JH, Simmons BH, et al. HGF/c-MET acts as an alternative angiogenic pathway in sunitinib-resistant tumors. Cancer research. 2010;70:10090–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Xie Z, Lee YH, et al. MET Inhibition in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Cancer.2016;,7: 1205–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vaupel P, Mayer A, & Höckel M (2004). Tumor hypoxia and malignant progression. Methods in enzymology, 381, 335–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gossage L, Eisen T, Maher ER. VHL, the story of a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017; 15:55–64.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li Y, Ye X, Tan C, et al. Axl as a potential therapeutic target in cancer: role of Axl in tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis Oncogene 2009; 28:3442–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sternberg CN, Hawkins RE, Wagstaff J, et al. A randomised, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in patients with advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final overall survival results and safety update. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1287–96.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:722–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. The Lancet. 2008;372:449–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Corso S, & Giordano S Cell-autonomous and non–cell-autonomous mechanisms of HGF/MET–driven resistance to targeted therapies: from basic research to a clinical perspective. Cancer discovery 2013;3:978–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schmidt L, Duh FM, Chen F, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nature Genetics. 1997;16:68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gibney GT, Aziz SA, Camp RL, et al. c-MET is a prognostic marker and potential therapeutic target in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:343–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Choueiri TK, Vaishampayan U, Rosenberg JE, et al. A phase II and biomarker study (MET111644) of the dual MET/VEGFR-2 inhibitor foretinib in patients with papillary renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;43:3383–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ciamporcero E, Miles KM, Adelaiye Ret al. Combination strategy targeting VEGF and HGF/c-MET in human renal cell carcinoma models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:101–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bentzien F, Zuzow M, Heald N, et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of cabozantinib (XL184), an inhibitor of RET, MET, and VEGFR2, in a model of medullary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2013;23:1569–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Graham TJ, Box G, Tunariu N, et al. Preclinical evaluation of imaging biomarkers for prostate cancer bone metastasis and response to cabozantinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106: dju033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kurzrock R, Sherman SI, Ball DW, et al. Activity of XL184 (Cabozantinib), an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2660–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Elisei R, Schlumberger MJ, et al. (2013). Cabozantinib in Progressive Medullary Thyroid Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 3639–3646. JCO.2012; 48: 4659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24*].Choueiri TK, Pal SK, McDermott DF, et al. A phase I study of cabozantinib (XL184) in patients with renal cell cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25: 1603–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vaishampayan U Cabozantinib as a novel therapy for renal cell carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15:76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26**].Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373: 1814–23.The trial that established the efficacy of cabozantinib.

- [27**].Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016; 17:917–27.The trial results established the efficacy of cabozantinib for overall survival.

- [28].Bentzien F, Zuzow M, Heald N, et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of cabozantinib (XL184), an inhibitor of RET, MET, and VEGFR2, in a model of medullary thyroid cancer. Thyroid, 2013; 23, 1569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Katayama R, Kobayashi Y, Friboulet, et al. (2015). Cabozantinib overcomes crizotinib resistance in ROS1 fusion–positive cancer. Clinical cancer research, 21, 166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lacy SA, Miles, et al. (2016). Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cabozantinib. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cometriq™ (cabozantinib) capsules. US prescribing information. Exelixis, Inc. November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nguyen L, Benrimoh N, Xie Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cabozantinib tablet and capsule formulations in healthy adults. Anticancer Drugs. 2016;27: 669–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nguyen L, Holland J, Ramies D, et al. Effect of Renal and Hepatic Impairment on the Pharmacokinetics of Cabozantinib. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016; 56:1130–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nguyen L, Holland J, Mamelok R, et al. Evaluation of the effect of food and gastric pH on the single-dose pharmacokinetics of cabozantinib in healthy adult subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55:1293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McKay RR, Kroeger N, Xie W, et al. Impact of bone and liver metastases on patients with renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy. Eur Urol. 2014;65:577–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Nguyen HM, Ruppender N, Zhang X, et al. Cabozantinib inhibits growth of androgen-sensitive and castration-resistant prostate cancer and affects bone remodeling. PloS one. 2013; 8: e78881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gordon MS, Vogelzang NJ, Schoffski P, et al. Activity of cabozantinib (XL184) in soft tissue and bone: Results of a phase II randomized discontinuation trial (RDT) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. Abstract, ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings 2011. May 20 (Vol. 29, No. 15_suppl, p. 3010) [Google Scholar]

- [38].Smith DC, Smith MR, Sweeney C, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced prostate cancer: results of a phase II randomized discontinuation trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:412- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schiff D, Desjardins A, Cloughesy T, et al. Phase 1 dose escalation trial of the safety and pharmacokinetics of cabozantinib concurrent with temozolomide and radiotherapy or temozolomide after radiotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with high‐grade gliomas. Cancer. 2016;122:582–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhang Y, Guessous F, Kofman A, Schiff D, Abounader R. XL-184, a MET, VEGFR-2 and RET kinase inhibitor for the treatment of thyroid cancer, glioblastoma multiforme and NSCLC. Drugs. 2010;13:112–21 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41**].Choueiri TK, Halabi S, Sanford BL, et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma of poor or intermediate risk: The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:591–7.Trial established the benefit of Cabozantinib in the first line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma

- [42].Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2011;378:1931–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Glen H, et al. Lenvatinib, everolimus, and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, phase 2, open-label, multicentre trial. The Lancet oncology 2015;16, 1473–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott D, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. New Engl J Med, 2015; 373, 1803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kelley RK, Verslype C, Cohn AL et al. Cabozantinib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Results of a Phase 2 Placebo-Controlled Randomized Discontinuation Study. Ann Oncol 2016; 28: 528–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]