Abstract

Purpose

The Internet is a fully integrated part of young people’s life and it is pivotal that online resources are developed to maximize the potential of the Internet to support those living with and beyond cancer. We sought to understand how young people with a cancer diagnosis use the Internet and to what extent information and support needs are met by existing online resources.

Patients and methods

This was a participatory action research study involving 21 young people participating in workshops and individual interviews. Participants aged 13–24 years were diagnosed with a range of cancers. Young people were on treatment or had completed treatment; some had experienced relapse. Workshops consisted of participatory methods including focus group discussions, interactive activities, and individual thought, encompassing online resources used; when, how and what they were searching for, whether resources were helpful and how they could be improved.

Results

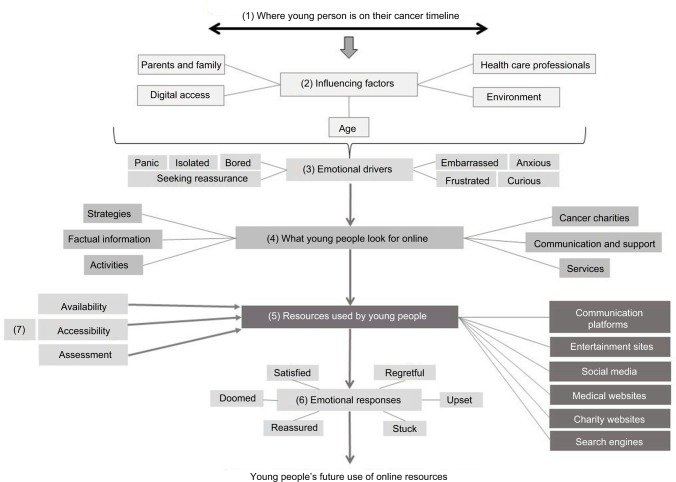

Young people reported using communication platforms, entertainment sites, social media, medical websites, charity websites, and search engines to find information and support. Different online use and needs were described throughout their cancer timeline and online use was generally driven by negative emotions. Seven factors influenced access and engagement: 1) where young people were on their cancer timeline; 2) external influencing factors, such as family and environments; 3) emotional drivers; 4) what young people search for online; 5) resources, websites, and digital platforms used by young people; 6) availability, accessibility, and assessment of online information and resources; 7) emotional responses to using online resources.

Conclusion

The way young people access and engage with online resources is complex with multiple influencing factors including powerful emotional drivers and responses to Internet searching. There is a need to develop resources that support the holistic needs of young people and this should be done in collaboration with young people.

Keywords: teenagers, adolescents, young adults, Internet, social media

Video abstract

Introduction

Teenage and young adulthood is a significant time of personal, psychological, social, and physical development, and a cancer diagnosis and treatment significantly interrupts this developmental process.1,2 Additionally, cancer treatment can involve periods of isolation from peer networks, which can have a significant and long-lasting impact on young people’s social maturity and relationships.3 An increasing focus on cancer in young people has led to increased understanding of the unmet psychosocial needs of this group and subsequent development of tools and networks to ensure that these unique needs are being met.4

The Internet is a fully integrated part of daily life for young people; thus, it is important that online services are developed to maximize the potential of the Internet to support young people with cancer. Patients turn to online resources for information and support, partly due to round-the-clock accessibility, anonymity, and availability of smart phones.5 Social media platforms are ever-evolving and expanding, providing an accessible medium for young people with cancer to socialize, communicate with peers, and to share information and experiences both during and after treatment. The Internet offers support in several ways: seeking information about their cancer and treatment; learning healthy coping mechanisms and behaviors; and gaining support/advice from peers with similar experiences.6

Despite increasing use, the online information needs of young people with cancer and how much these needs are being met by current resources has not been systematically investigated. Previous consultation carried out by Teenage Cancer Trust, a UK charity supporting young people with cancer (personal communication), demonstrated variation in preferences of how information is delivered. For example, information about cancer types was preferentially delivered by text, information about “being diagnosed” was preferentially delivered by a film featuring a health care professional, and information about “what to expect during treatment” by a film featuring a young person sharing his/her own experiences. This indicates that a uniform approach to the format and delivery of information would not suit this population. We have previously shown that the “who, what and when” of information delivery is one of the “arts” of “age-appropriate care”, and the tenet of specialist teenage and young adult (TYA) cancer care in England.7

In addition to online information seeking, there is expanding use among young people of engaging with online resources and platforms to access peer support.8,9 Previous studies have shown that young people use online social networking platforms to gather and share stories and provide emotional support for each other.1,6,10 While existing social media platforms, such as Facebook, host many of these interactions, little is understood about how the use of social media can be optimized to encourage and enhance social support for young people living with and beyond cancer.1 The challenges of providing online/digital support for young people are numerous, and multiple disease types and a wide range of life stage commitments considerably increase the amount of information sought as well as creating a diversity of emotional needs.

We aimed to find out when, how, and what information and support young people with cancer were searching for, whether these resources were helpful, and how they could be improved.

Materials and methods

This was a Participatory Action Research study.11 This method facilitates feedback to stakeholders in a responsive framework, which ensures that recommendations generated from the study were acceptable to young people with cancer.

User involvement

The BRIGHTLIGHT Young Advisory Panel (YAP) is a group of 20 young people with a previous cancer diagnosis, who are integral in the design and conduct of BRIGHTLIGHT, the national evaluation of TYA cancer services in England.9,12 We held a workshop with the YAP utilizing their research experience and these data were used to establish suitable data collection methods.

Study participants

This was a multicenter study recruiting young people from three TYA cancer services in England. We aimed to recruit 30 young people aged 13–24 years with a cancer diagnosis within the last 5 years. Young people were eligible to take part in the study if they were aged 13–24 years at cancer diagnosis and could communicate in English. Eligible young people were identified and recruited by their health care teams. Written consent was obtained at the time of workshop/interview.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Health Research Authority, London Brent National Health Service Research Ethics Committee (16/LO/1661) and Research & Development Departments at each participating hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants, and where the young person was <16 years old, parental consent was also obtained.

Data collection

Data were collected through workshops and individual interviews. The workshops were held in a mix of clinical and nonclinical environments. The interviews were all conducted in the clinical environment. Workshops/interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Workshops

The workshops consisted of interactive activities and individual thought. The workshop discussions/activities centered around the following: which online resources young people accessed and when and how they used them; what they searched/used online resources for; whether these resources were helpful to them; and how they could be improved. Young people worked in small groups on a printed timeline (from the point of cancer diagnosis up to living beyond treatment) to identify what they were using the Internet for and why this was significant at that time point. This was followed by a wider group discussion, facilitated by the research team with prompts and probing for deeper insight.

Interviews

Individual interviews were conducted with younger adolescents (aged 13–16 years) and those receiving treatment, as these specific subpopulations were not represented in the workshops. These were directed by a semi-structured topic guide based on the structure and content of the workshops (Supplementary material).

Analysis

The interviews and workshops were analyzed using framework analysis.13 The transcripts were read initially for overall understanding of content and context. Initial categories and codes were identified and mapped out by one researcher (SL), which were used to build a framework for analysis. The interviews were then coded, with each reference to a specific category charted using the framework. Where additional categories or subcategories emerged, these were added to the framework iteratively. Analysis was validated by three researchers (AM, LAF, RMT). Themes were developed from the framework and a conceptual model was developed from these themes.

Results

A total of 21 young people participated in the study: 15 in the workshops and six in individual interviews (Table 1). Some young people had experienced relapse after their initial diagnosis. Young people reported using communication platforms, entertainment sites, social media, medical websites, charity websites, and search engines to find information and support. Different online use and needs were described throughout their cancer timeline. Seven factors influenced accessing online resources:

Where young people were on their cancer timeline

External influencing factors, such as family and the environment

Emotional drivers

What young people search for online

Resources, websites, and digital platforms used by young people

Availability, accessibility, and assessment of online information and resources

Emotional responses to using online resources

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 6 (29) |

| Female | 15 (71) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |

| <13a | 1 (4) |

| 13–15 | 6 (29) |

| 16–18 | 4 (19) |

| 19–24 | 10 (48) |

| Cancer type | |

| Leukemia | 6 (29) |

| Lymphoma | 8 (37) |

| Sarcoma | 6 (29) |

| Other solid tumors | 1 (5) |

| Status at participation | |

| On treatment | 13 (62) |

| Off treatment | 8 (38) |

| Time since treatment ended, years (n=8) | |

| <1 | 1 (12) |

| 1–2 | 2 (25) |

| >2 | 5 (63) |

Note:

Diagnosed <13 and relapsed as teenage and young adult.

These are presented in Figure 1 before being discussed in detail with anonymized, supporting quotes from young people.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing young people’s decision making and actions when accessing online resources.

Where young people were on their cancer timeline

The cancer timeline was proposed by the YAP, in preference to traditional descriptors such as “journey” or “trajectory”. The timeline included prediagnosis, diagnosis, treatment, end of treatment, and living beyond treatment. Young people had varying online needs across their cancer timeline accessed a range of websites, with particular websites notable at certain time points. Young people on treatment sought factual information from their treatment, which was distinct to those who had finished treatment.

Everything medical has definitely come from the hospital. [Interview, young person 3]

They reported satisfaction with the information they had received from their health care team and felt that their information needs had been met:

Everybody here has been so informative and so engaging […] I don’t feel like I’m missing out on anything. I don’t feel like I’m not in the know. [Interview, young person 3]

Young people on treatment spoke of using social media to keep in contact with peers, most frequently through Facebook and WhatsApp. However, they recognized that their needs may differ in the future. For those coming to the end of treatment or who had finished treatment, their online searching focused on wider holistic needs such as fertility, depression, and anxiety as well as practical information, such as advice about travel insurance.

External influencing factors

Various external influencing factors influenced whether a young person engaged with online information and resources: health care professionals; parents and family; the environment; age; and online access.

Health care professionals

Health care professionals were the main source of information for young people during their cancer treatment and influenced their online use. Three subthemes emerged relating to health care professionals and young people’s online searching: attitude; sign-posting and education; and leaflets/resource provision. Health care professionals’ attitude affected young people’s approach to looking for information online and how they felt about it. Young people described health care professionals accepting that young people may want to look for information online, while some encouraged young people to be cautious if searching online and others actively discouraged young people to look at information on the Internet.

I was told, like, be careful of what you read…because a lot of things can be untruthful sort of thing. If I had a question, not to Google it, to go straight to my Consultant and ask him […] [Workshop 1, young person 7]

If young people were instructed not to search online for information by a health care professional they tended to follow this advice. In contrast, some health care professionals gave advice about which websites to access or if there were social media groups or sites that they could join, such as a Facebook group for the hospital. Professionals signposting young people to look at resources were predominantly youth support co-ordinators (YSCs). Young people talked about their YSCs directing them to cancer charity websites such as Little Princess Trust for information about getting a wig (http://www.webcitation.org/6ytVMQjPm); relevant Facebook or WhatsApp groups to help young people stay connected with the social activities of the unit; or to helpful online resources, such as “Headspace” (http://www.webcitation.org/6ytVyvrUq). Social workers also signposted young people to online resources, for example, the Macmillan mobile app (http://www.webcitation.org/6ytWBb7gk). Although this was thought to be a useful tool for reminding young people to take their medication, the app was tailored toward more adult cancers and did not contain the correct drugs for TYA cancer patients to enable use.

While young people valued the Internet as an information resource, it was clear that at all stages of their cancer timeline, face-to-face interactions with health care professionals to obtain information and answer their questions were important. This was mentioned frequently by young people:

I think I just wanted an explanation from a doctor, someone who was actually there with me, rather than reading or watching a video. [Workshop 1, young person 9]

Face-to-face interactions were an important source of information and support for young people. Moreover, leaflets provided by professionals served as a useful prompt for young people to search for specific information or charities when they got home, or at a later stage in their timeline. This highlighted the challenge for young people who are beyond treatment and not having regular interactions with health care professionals to access face-to-face support.

Parents and family

Interactions that occurred between young people and their parents/extended family in relation to online information varied widely. Parental attitudes toward the Internet influenced young people’s online information seeking, with some parents sharing information found online with their children:

My dad’s very into the Internet […] he will always try to search for medical journals and he’ll send me a link to the medical journal […] [Workshop 1, young person 7]

Other young people did not share or discuss online resources with their parents. In some instances, young people actively discouraged their parents from looking online and ignored online information their family wanted to share with them. In addition to information seeking, young people described their parents’ use of the Internet for communication and support and to stay in touch with family and friends, particularly during extended periods of time spent in hospital with their children. Young people reported the challenges their parents came across when using the Internet to look for information and how they struggled to find the information that they wanted:

My parents were doing a lot of research, and I do not think it helped them either, because they wanted answers just as much as I did, but neither of them could find anything. [Workshop 3, young person 18]

The environment

In some circumstances, the environment stimulated young people to look at websites. For example, prominent branding on charity-funded units generated impetus for searching online:

On the ward I was on, it was mainly Teenage Cancer Trust, so it was all around us […] I thought I’d have a look at it. [Workshop 1, young person 8]

Other environmental triggers prompted young people to search for specific resources. For example, young people also searched for “Macmillan” because of its familiarity as a cancer charity and strong branding presence in hospitals, including uniforms of funded staff:

The first person I spoke to was a Macmillan nurse […] it put the word into my head, and it’s like, “I’ll go onto their website.” [Workshop 1, young person 9]

Age

Young people’s age influenced the relationship they had with online resources and how they accessed them. Young people in the study spanned ages 13–24 years at diagnosis. Although young people generally had similar experiences and views in relation to their online needs, there were nuances in what they looked at and where they looked online. Younger patients discussed online computer games and using social media to speak to friends. Less of their discussion was about cancer-related information online. Those in their late TYA years demonstrated greater understanding and awareness of the challenges and risks associated with searching for information on the Internet.

Online access

The difficulties of connecting to the Internet were a recurrent issue for young people on treatment. The wireless Internet in the cancer units was reported as unreliable and slow, which affected use of certain digital platforms, such as messenger programs, video streaming, and gaming websites. These were all activities young people enjoyed as a distraction from feeling unwell and being bored in hospital. Unreliable or unusable Internet access, therefore, affected young people’s hospital experience:

I’ve not heavily relied on it [online resources] because the Internet’s not been too great […] I’d be using my data straight away on my phone. [Interview, young person 2]

Emotional drivers for using online resources

Emotions emerged as a driving force that mobilized young people to use the Internet to access specific information or resources. Emotional drivers were predominantly negative emotions (Table 2). For example, feeling isolated and needing to talk to someone, or feeling anxious and in need of more information.

Table 2.

Emotional drivers for using online resources in young people with cancer

| Emotion | Example of how it drives use of online resources |

|---|---|

| Panic | “a lot of the time, when I was searching with things to do with cancer, it’s like I’m in a panic, I’m upset, I just need to know this even though I know it will make me upset to find out.” [Workshop 1, Young Person 10] |

| Bored | “I actually think physical wellbeing was more of a thing that, say if I was on, like, the Teenage Cancer Trust website, that I would just look at when I was bored.” [Workshop 3, Young Person 19] |

| Frustrated | “I guess I was frustrated because obviously friends and family… they can only understand to a certain extent… sometimes you need someone to actually relate to how you feel.” [Workshop 3, Young Person 17] |

| Curious | “I started to get curious and I went onto the Cancer Research website to see how people survive and what your odds are basically.” [Workshop 2, Young Person 15] |

| Anxious | “I was depressed and, like, really anxious about the future, so I looked it up, ‘Is that normal? What can help with it?’” [Workshop 3, Young Person 18] |

| Seeking reassurance | Discussing why the young people needed to look up information after they have been diagnosed: “Reassurance…it’s just nice to see that other people have, like reacted in the same way.” [Workshop 1, Young Person 13] |

| Isolated | Talking about her experience of being treated on an adult unit: “Even the nurses are all, kind of, older…you just feel isolated. So yes, at that point I was Googling…” [Interview, Young Person 4] Also, young people who were undergoing treatment on the ward described how they turned to social media and online communication platforms when they felt isolated from their peers |

| Embarrassed | Talking and having questions about fertility: “Looking it up on the Internet, you’re a bit more anonymous, aren’t you? …It’s not like having a conversation about it…if your Mum and Dad are there, it’s more awkward.” [Workshop 3, Young Person 17] |

What young people look for online

Young people had several types of information needs, as well as using online applications to access peer support. The uses of online resources fell into six categories: strategies, factual information, activities, communication and support, cancer charities, and services.

Strategies

Young people explained how they would use the Internet to look for strategies and advice on coping with their cancer. Strategies were related to cancer and treatment or to young people’s more general holistic needs, such as social, spiritual, and psychological needs. Young people looked for strategies from information websites or from other young people through sharing advice either directly or indirectly. Reading or hearing about other young people’s experiences of similar treatment helped them to know the problems they had experienced to understand how they coped. Strategies to help young people cope were frequently searched for. These included managing body image issues, insomnia, dietary and nutrition advice, their thoughts and feelings, and relationships with family and friends while going through their cancer timeline.

Factual information

Young people searched for factual information about their cancer diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, tests, and procedures. This was predominantly at the diagnosis and early treatment phases of the cancer timeline:

I looked up the success rate, which I saw was really high, but I knew that anyway. [Interview, young person 1]

Young people frequently spoke about Cancer Research UK, Macmillan, and National Health Service (NHS) Choices as being useful sources of cancer-related information around cancer diagnosis and treatments. However, young people with rare cancers or facing relapse reported factual information as hard to find or missing entirely:

I think it was because I’ve got a rare kind and I wanted to know specifically about my drug and specifically about my tumour. That kind of information isn’t available at Macmillan because it’s so rare. [Workshop 1, young person 8]

Activities

There were several online activities that young people reported using: playing games; watching TV, films, and video clips; and using social media, messaging “Apps”, and blogging. Participation in online activities was driven by the emotion of boredom and young people accessed these online resources as a means of distraction while in hospital. Additionally, young people described sharing stories and experiences with others on social media as being therapeutic:

I’ve just been sharing a blog […] I guess everything I am producing through Instagram is not photos of me partying […] It’s just channelling it in a different way…it’s definitely felt very natural to just continue that normally in these new circumstances. [Interview, Young Person 3]

Communication and support

Young people used the Internet to communicate with their family, existing peers, and new peers met along their cancer timeline. This was most commonly through social networking applications such as WhatsApp, Facebook, Facebook messenger, and Skype. They sought online support from peers, particularly when on treatment because of geographical distances when hospitalized. Three types of peer support emerged: keeping in touch with existing peers; communicating with other patients with a cancer diagnosis who they had met during their cancer timeline; searching online for other young people with a cancer diagnosis to get support and share experiences.

Young people sought the support of someone who had the same diagnosis as them through social media or through cancer charity websites:

I did try and find people who had my same thing through Macmillan, and I did find someone who I could talk to, who had almost the exact same thing. [Workshop 3, young person 19]

Conversely, some young people reported having no interest in looking for peer support online. This was often young people on treatment who felt that they did not need it.

I just have really, really good friends around me, that I would not really need it. [Interview, young person 1]

Peer support was not always actively sought: young people found and made friends “accidentally” through online resources such as charity Facebook pages. Overall, it was down to the young person and their individual character, preferences, and circumstance as to whether they had, or thought they would access an online peer support system.

Cancer charities

Young people searched the Internet for cancer charities to see what they offered. They found reading or listening to the stories of other young people who had been through cancer helpful and reassuring. Holistic information about young people’s psychosocial needs on Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support seemed to address some, but not all their support needs. Young people explored cancer charity forums to learn and seek reassurance from others with cancer, but described not being reassured and sometimes having a negative experience while reading the charity forums.

Services

Young people searched online for information about their treating hospital or cancer unit. Often this information was not available:

I definitely looked up that a lot, because I wanted to see how the rooms looked […] rather than having to wonder if it’s going to be nice […] I’m sure other people like my friends would probably want to see pictures of it [hospital hotel], and family. [Interview, young person 1]

Additionally, young people referred to searching for services that were available in their local area, such as things to do while on chemotherapy.

Resources, websites, and digital platforms used by young people

Young people accessed a wide variety of types of online websites, resources, and applications: communication platforms, entertainment sites, social media, medical websites, charity websites, and search engines. The time these were accessed, reasons for accessing, and satisfaction with the content were variable (Table 3). We specifically asked young people whether they had looked for available research they could participate in but none of the participants had looked for this online.

Table 3.

Frequently mentioned resources, websites, and digital platforms used by young people

| Website, resource, or application | When are they using it? | Why are they using it? | Comments from young people |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Research UK | Throughout the whole cancer timeline, from prediagnosis to the end of and beyond treatment | • To search for all types of information: facts (about their cancer, treatment, drugs, procedures), holistic information (about body image, moods, body image) • To search for advice and strategies on how to cope • To search for peer support from other cancer patients |

“The Cancer Research website is really good as well. The statistics.” [Workshop 1, young person 8] “I’ve seen people. They’re like, ‘I’ve beat cancer after this amount of time,’ that makes me quite happy… charity events to help people, so that inspires me. I want to do the marathon.” (Specific reference to Cancer Research UK Instagram page) [Interview, young person 5] |

| Throughout the whole cancer timeline, from prediagnosis to the end of and beyond treatment | • To communicate with friends and family • To fundraise • To search for peer support from other cancer patients • Access Hospital/Unit Facebook pages to learn about social events that were happening • Cancer charity Facebook pages to find out other people’s experiences and helpline numbers (Shine, Teenage Cancer Trust, Teens Unite) |

“I also enjoy Facebook. I also do use it throughout the whole day…when I was diagnosed we did loads of fundraising and Facebook just got it out there.” [Workshop 2, young person 15] “Facebook to give you contact with friends and stuff, I used that quite a lot during.” [Workshop 4, young person 21] “I know the Teenage Cancer Trust have a Facebook page because I remember meeting people through that as well. That was quite cool.” [Workshop 1, young person 7] |

|

| Throughout the whole cancer timeline, from pre-diagnosis to the end of and beyond treatment. | • The main search engine used • Young people using it by looking at the “Top hits” and conducting “quick searches” • Used it as a link to other websites • To search for all types of information: facts (about their cancer, treatment, drugs, procedures), holistic information (about body image, moods) • To search for advice and strategies on how to cope • To search for peer support from other cancer patients |

Google was a gateway to other sites and resources: “I think I probably used Google to get to all the other websites.” [Workshop 1, young person 9] Young people acknowledged that they could not always trust everything in a Google search “I will use Google but I’ll check several different tabs just to make sure that all of them are saying the same that it’s not just taken from a random website…” [Workshop 3, young person 17] Young people used Google to double-check information they have been given elsewhere “I just wanted to see what IAM [integrated assessment map] was saying, compared to Google…” [Workshop 3, young person 18] |

|

| Little Princess Trust website | On treatment, end of treatment and beyond | • To search for wigs • To find out how to donate their hair |

Young people said they would have liked a gallery of wigs and what they look like: “What I did notice was that on the Princess Trust website, I would have wanted to see a gallery of wigs, to see, try and get an idea of what they look like, or what I could get myself, but I couldn’t find that.” [Interview, young person 1] |

| Macmillan Cancer Support website | Throughout the whole cancer timeline, from pre-diagnosis to the end of and beyond treatment. | • To search for all types of information: factual information (about their cancer, treatment, drugs, procedures), holistic information (about body image, thoughts and feelings, how to tell your family and friends you have cancer) • To search for advice and strategies on how to cope • To search for peer support from other cancer patients • To find out information relating to moving on after treatment finishes, such as travel and getting back to work |

Macmillan was described by young people to be a trustworthy resource to seek information: “I would go to it because it’s a trusted site.” [Workshop 1, young person 12] “I use the Macmillan support website to check stuff that I do not know. Sometimes I want to know what chemo does, what it’s for and then I’d go on that kind of website.” [Workshop 1, young person 10] The Macmillan website was described as user-friendly to young people: “I think I understood everything on the Macmillan website. I do not think any of it was too difficult.” [Workshop 1, young person 11] |

| Macmillan Cancer Support app | On treatment | • Information and scheduling of when to take their tablets • Use it to schedule their appointments and as an organizer/diary |

Young people liked the concept of the app, and said that they would in theory use it; however, unfortunately, it did not offer the specific information relating to their drugs: “There’s a diary thing, isn’t there? Macmillan app… it’s like a diary-based-, it’s just to keep you updated…When I tapped in my own tablet what I take, nothing comes up. So, there’s no point in having it.” [Workshop 4, young person 20] |

| Macmillan Cancer Support Forum | On treatment and beyond treatment | • To search for advice and strategies on how to cope • To search for peer support from other cancer patients |

There were mixed feelings expressed about using the Macmillan forum. It was described as good, even though “there’s lots of scary cancer related things.” [Workshop 1, young person 13] “What I didn’t like about the Macmillan forums, which I accept is necessary, but there were lots of pages on the Macmillan forums which were like relatives or, like, widows and things, and it made me feel like I was doomed… most of the titles of the posts were like, ‘My husband has died and I do not know what to do,’ or, like, ‘My little girl’s about to die,’ it was kind of upsetting.” [Workshop 1, young person 11] |

| NHS website | Prediagnosis, at diagnosis, and throughout treatment | • Prior to diagnosis to look up symptoms • To look up information and facts related to their cancer and treatment, including prognosis, drugs, and procedures |

Young people were reassured by the NHS logo accompanying the website and the information that was there was helpful, although it did not address some of the more young people specific holistic issues. “Before I knew what was wrong and you’re looking up symptoms, the NHS website was good.” [Workshop 1, young person 8] “If I’m unsure about a procedure, like before I got my PICC [peripherally inserted central catheter] line put in, I looked it up on NHS and Cancer Research UK, just what does that entail? How is that done? How would I feel about it? Does that make things easier?” [Workshop 2, young person 16] |

| Teenage Cancer Trust website | On treatment | • To search for other patients’ stories • How to manage their relationships with their parents/siblings/friends • To search for peer support from other cancer patients • Knowing what to expect when going through cancer |

Young people had not used Teenage Cancer Trust website prior to diagnosis and tended to seek factual information from other websites. “The Teenage Cancer Trust have got quite a good part on their website about how to talk to people.” [Workshop 4, young person 21] “They had some videos on their homepage…looking at other patients’ stories…there could have been more, but there were some.” [Workshop 1, young person 9] |

| Throughout the whole cancer timeline, from prediagnosis to the end of and beyond treatment | • To keep in touch with family and existing friends • A group chat for talking to and organizing social events with new friends met through the hospital |

WhatsApp was praised for keeping up with existing friends and family and new friends. “Talking to my mum and my sister, especially on days when I’m not happy with the way I look. Especially when I lost my eyebrows, when I just feel poorly and I’m by myself, that is definitely a very big help.” [Workshop 2, young person 15] “There’s a WhatsApp group from the hospital here and I think they do monthly things, like this Friday we’re going for burgers.” [Workshop 4, young person 20] |

|

| YouTube | Throughout the whole cancer timeline, from prediagnosis to the end of and beyond treatment | • To watch videos related to cancer, such as patient stories or procedures • To look up strategies related to holistic well- being, such as makeup techniques or tying headscarves |

“I used YouTube a lot… watched other people doing videos about their things… it’s nice to see people, like, living after cancer… It gives you a sense of joy, when you look at their life instead of yours… takes your mind off what is happening. It relaxes you a bit.” [Workshop 1, young person 10] “I would use YouTube to find out more about what was happening, because people would talk about their cancer and you could Google tests that you were having and just watch it on YouTube if you want to.” “I had to have a bronchoscopy, so I decided to watch one on YouTube before having it done.” [Workshop 1, young person 14] |

Abbreviation: NHS, National Health Service.

Availability, accessibility, and assessment of online information and resources

Young people spoke about the availability of information (whether they were able to find what they were looking for), the accessibility (how easy it was to find), and their assessment of the reliability and trustworthiness of information. These three core aspects influenced young people’s emotional response to the resource, how they engaged with it, and potentially how they will use online resources in the future.

Availability

Availability of information was an issue highlighted by young people with rare types of cancer. They sought information about their disease and treatment on trustworthy websites specifically for cancer information, but this was often not successful because of the rarity of their cancer. Specific holistic information was often not available, for example, young people described struggling to find information about wigs. Similarly, young people reported that practical information about funding and financial support was not available to them online. This could be that this information was not available or that young people were not sure where to find it.

Accessibility

The accessibility of certain digital resources or particular information was described as challenging in some cases:

I tried to look up the Facebook page for the [hospital-specific service], because I wanted to see pictures […] which was slightly difficult […] I do not think I found, maybe I did find a Facebook page […] it wasn’t that easy though. [Interview, young person 1]

As described earlier, Google was the main search engine used by young people. They felt that Google was useful for navigating the online world and was, therefore, a pertinent part of their connection with the Internet.

Google is perennial in everyone’s life, but I definitely think that Google was a major part of my research, because it’s the only accessible thing. [Workshop 1, young person 10]

Often more accessible information was described in terms of its ease to find. Young people openly recognized that they often looked at the most accessible places when seeking information: the “top hits” and “top searches” on Google. Young people felt that having round-the-clock, anytime, anywhere access to information/support was a noteworthy advantage of the Internet. They accessed online resources at all times of the day and night and this influenced how they used it. For example, young people connected with cancer patients in other countries in the middle of the night.

Assessment

Young people naturally assessed the quality of the information found online and made an assessment of the credibility of the source of that information. This happened on different levels: making a reference to how well known the website was, showing some caution with trusting online information, or full awareness and understanding of the risks associated with trusting the Internet. While Google was mentioned and used regularly, there were young people who recognized that the information that they found could be false or irrelevant.

I’ve kind of taken the attitude from day one of not Googling anything […] I would rather just consume what is relevant to me rather than bog myself down in information that might not apply to me and might give me unrealistic expectations. [Interview, Young Person 3]

This understanding of individual differences in terms of cancer, stage, and personal needs was described as a reason to be cautious when searching for resources online. Some young people had the strong view that they could not trust the Internet for information:

I don’t know if its false information […] online you dont know if its true or not. There’s just so much information like that online. [Workshop 3, Young Person 19]

Others used Google to look up certain questions and queries but expressed anxieties about doing so. Some used Google as a way of linking to several information sources and, therefore, validating or discrediting the information that they found through a process of “cross-checking” information across sources. Young people were aware and understood that the Internet was an unfiltered environment, where information may or may not be true. Young people talked about preferring to visit “official sites” with “official information” which they could fully trust, influenced by being signposted to certain trustworthy websites by health care professionals.

Emotional responses to using online resources

Young people described an array of different emotions that followed an interaction online. Positive emotional responses included feeling better, reassured, or relaxed. Young people described positive feelings of satisfaction with what they found online when it met their needs. Moreover, they described feeling reassured by the information that they found online. They enjoyed social media and communication platforms, such as Facebook, which provided them with opportunity to connect with others, particularly when they were in hospital and in a place where they were disconnected from peers and family. Other digital resources provided both entertainment and “a sense of joy” for young people, which detracted from their illness.

In contrast, young people expressed negative emotions such as feeling doomed, scared, upset, stuck, and regret for going online all emerged through the discussions with young people. As well as with finding information online, use of communication platforms to find and talk to other cancer patients, such as forums and social networking sites, caused some young people to feel a sense of fear and anxiety:

…I regret asking her […] this girl was telling me stuff that happened to her, and then I was waiting for that to happen to me […] makes me more panicky about it. [Workshop 1, young person 12]

There was also an addictive element of looking online, that once young people started, it was like a spiral and regardless of the emotional response it could be hard for them to stop looking for information online:

Looking up information can be helpful, but a lot of the time […] you feel worse and then you look it up more. You keep going back to look it up. It’s like an addiction. [Workshop 3, young person 19]

Young people’s content, formatting, and usability preferences

Young people reported what information or resources they would like to find online and how they would like it to look. Young people’s ideal online resources would be personalized, simple, have real-life case studies, create opportunities for peer support, and have accessible holistic information and strategies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Key features of young people’s online information and resources

| Key feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Personalized | Bespoke/tailored service recognizing differences in cancer and individual situations |

| Online platform at the end of treatment to request personalized advice | |

| Health care professionals providing direct answers to personal queries in a safe online forum | |

| Simple | Factual information about cancer and treatments to be presented in a simple format |

| Real-life case studies | Provide examples of coping strategies for holistic issues, such as dealing with thoughts and feelings that are not easily conveyed through text |

| Opportunities for peer support | Online social network to have peer support from other young people and not older adults |

| Accessible holistic information and strategies | Areas where information was required included help with fertility questions and concerns, anxiety and depression, brain fog, and tips to help manage these issues An app to help organization of appointments and medications would be helpful and would provide autonomy and independence |

Discussion

The results of this study underline several key findings. The Internet is an integral part of a young person’s experience of cancer encompassing diagnosis, treatment, and the accompanying holistic and practical needs that young people experience and this persists after treatment has finished. This is consistent with previous studies where it has been shown that young people with cancer are active online and accessing a range of health care-related online resources.11,14,15 For the first time we have shown distinct patterns of online use dependent on where young people are on their cancer timeline and that Internet searching is often driven by negative emotion. Factual information needs about cancer were generally well met by reputable cancer charity sites; however, young people had substantial unmet needs around peer support and holistic and practical information.

Young people on treatment had their information needs met by their treatment team. This corroborated a previous study where the majority of young people acquired information about their diagnosis and managing their cancer from the multidisciplinary team caring for them.14 In our study young people on treatment predominantly used the Internet for entertainment, playing games, and watching television and films. Young people discussed the positive impact this had on their time in hospital. Little is discussed in previous studies about the importance of the Internet for entertainment which is a key study finding. Young people on treatment also used the Internet to keep in touch with family and friends, both existing friends and people they had met during treatment.

Young people in our study used the Internet to search for factual information about their cancer diagnosis, prognosis, side effects, and treatment. Other studies have reported that young people with cancer and other forms of ongoing health needs look online to seek this type of information.8,14,16–18 and that learning about this was an important coping strategy.8,14 In this study young people sought factual information about cancer and cited readily available and accessible useful resources such as Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support (both nationwide charitable organizations) and NHS Choices. Our findings are supported by other research where the two most commonly accessed websites were Macmillan and a local hospital service.14 Young people recognized that there was myriad of websites available and that it was easier to use a search engine such as Google to pursue specific information. Conversely, some young people in our study could not remember what websites they had looked at and those with a rare cancer type struggled to find any information at all. This shows that despite the existence of many cancer-specific websites, navigating the current online landscape is not always straightforward for young people with cancer, particularly those with rare cancers.

Our study has shown that as young people progress toward the end/finish treatment their online information and support needs increase. This was the phase of the cancer timeline where young people most actively sought psychosocial, holistic support and a network of peer support. Young people searched for strategies to help manage issues such as body image, nutrition, and wellbeing and described frequently struggling to find the information they were looking for. This suggested an important unmet need of holistic information, such as psychosocial, emotional, and practical lifestyle-related information for this group, particularly when young people end treatment and have less contact with health care professionals. This aligned with previous reports of young people requiring education and support around healthy lifestyles, ongoing self-care, and screening.8,14,16,19–21 Similar to other studies,21,22 we found that after cancer treatment, young people want more practical information related to issues surrounding health insurance and financial support.

Our findings showed that at the end of cancer treatment and beyond, young people felt concern about their peer networks, even though they may have been reluctant to participate in peer support programs during treatment. This supports previous findings that some young people do not want to be part of a group that clearly identifies them as having cancer.8 Their desire to access cancer information and support changes over time and goes through phases.4,8

We identified a number of drivers of online searching including age and external factors such as the attitudes of health care professionals and parents to using the Internet, and their environment. In our study, young people discussed being signposted to specific websites by health care professionals and being more likely to look at a resource as a result of being signposted to it. Similarly, Abrol et al14 found that young people used online resources that were recommended to them by the health care professionals from their cancer service. In addition to differences depending on cancer timeline our findings showed differences across the age range in terms of online use, needs, and preferences of online resources. Further work is required to understand the differences across the TYA age range. Potential influencing factors could be increased autonomy, resilience, confidence, and experience in digital environments.8

A key finding of our study is that online use was driven by negative emotions such as fear, embarrassment, isolation, and panic. This can assist us to better understand the motivators for young people seeking online information or support and, therefore, support them in their searching. To date, little is known on how emotions influence how young people with cancer interact with the Internet. Previous studies have recognized isolation as an emotion driving young people to search for peer support.15,16,23

Young people spoke about the challenges of availability, accessibility, and the reliability of information online. They expressed uncertainty around the validity of information, or whether it was relevant to their situation and disease. Likewise, reliability of the information available online was acknowledged in other studies as being challenging with an additional challenge being confusing medical “jargon”.8,18 Challenges about jargon did not emerge in our study findings as the cancer websites commonly cited by young people in our study were described to be clear and understandable.

Young people did not express a particular desire for audiovisual content online as we may have anticipated; however, they wanted online information to be presented in a simple way and to include real-life examples and case studies, particularly to help them to deal with their thoughts and feelings. One way of meeting these needs would be the production of videos where young people explore their own real-life experiences of such issues. Young people have previously expressed wanting a medium to connect and share experiences with other young people as a source of emotional support.8 The lack of good quality information available online written at a level targeted toward the TYA age group is recognized,8 and young people would like information available in different ways such as audiovisual content.18

Strengths and limitations

Our study had a number of limitations; we aimed to include 30 young people and managed to recruit 21; therefore, some experiences may not have been captured. Despite this, 70% target recruitment for this population is impressive. Additionally, a number of young people declined to participate as they did not use the Internet to seek information and thought the study was not relevant to them; consequently we have not captured the views of those who do not seek information on the Internet and why they chose not to.

The majority of our participants were treated at TYA Principal Treatment Centers in England and the experiences of those treated outside of a Principal Treatment Center may differ particularly on treatment needs. However, despite these limitations the findings from our study make an important contribution to the evidence, most notably the model of influencing factors for online use. We managed to capture a range of ages, treatment experiences, and cancer types, and while the study population may be small the data collection methods enabled in-depth data collection.

Conclusion

Our study showed that there is significant unmet need for satisfactory holistic information and strategies surrounding issues such as fertility, anxiety and depression, and brain fog. Young people wanted online resources where they could meet others with similar experiences. Particularly, young people would like to do this earlier on in their cancer timeline rather than toward the end of or beyond their treatment. Young people who were undergoing treatment exhibited significantly different online use patterns than those who had finished treatment, in that they used the Internet to keep in touch with friends and family and pass the time. In this study, young people on treatment had their information needs met by their treatment teams so did not require online resources.

Despite general satisfaction with a number of online resources and a willingness to provide suggestions for improvements a key message was that any online resource would be unlikely to be superior or take preference to a face-to-face consultation with a knowledgeable expert. However, this could be another young person with relevant experience and not just a professional. Moreover, it is important to note that digital and online needs and preferences are individual, so one format of information delivery will not apply to all.

Research and practice implications

Understanding how young people’s information and support needs change in different phases of their cancer timeline is critical to tailoring online cancer information for their use. This can inform professionals and developers of online materials to tailor resources to provide young people with the most useful information at the time when they require it most. Online resources need to be highly visible, provided by accredited providers and easily accessible through search engines to ensure young people find and use them.

We cannot assume that young people are digital natives or that online support and information are preferable. The Internet should therefore be used as a tool to enhance face-to-face interactions with professionals. Given the pivotal role of health care professionals as mediators of online searching, an accredited list of online resources to guide young people through dependent on where they are on their timeline would be beneficial. Being aware of the emotional drivers and responses that young people have to online information and using online resources could assist us in shaping online platforms that are sensitive to this. Further, as health care professionals if young people tell us they have been searching online then being responsive to the emotion which is driving the searching may assist in diminishing that negative emotion.

Further research is required around the online needs of young people being treated outside of TYA Principal Treatment Centers as their needs may differ to those young people in our study. The information and support needs of the parents and caregivers of young people are also worthy of exploration as a number of young people spoke about managing their parents’ Internet searching and a lack of suitable resource for them. Further research examining different needs across the TYA age range would also be beneficial to further tailoring online needs of this group.

In conclusion, suitably tailored online resources would harness existing cancer information and develop young person-focused holistic and practical information. A well-designed resource has the potential to reduce anxiety, improve patient well-being and ultimately outcomes for young people with cancer.

Supplementary material

Focus group topic guide

Explain purpose of discussion. Cover confidentiality allowing all young people to have view. Challenge the idea, not the person, and please try not to mention hospital names or health care professionals.

-

Experiences of using the Internet to look for information Tell us a little of how you used the Internet to look for information and support for your cancer.

Prompts:

What was most helpful, sites, format.

Any difficulties encountered

Which ones they use the most

Timing (eg, current use vs past use)

Frequency of use (eg, multiple times per day or per week vs once or twice ever)

Level of engagement (eg, passively browsing vs posting one’s own content)

Purpose of use (eg, to seek support for oneself vs provide support for others)

-

Optimizing online information for young people with cancer

What are the main changes you would make for online information more accessible for young people?

Prompts: Cover each part of the cancer trajectory-

–Cancer symptoms

-

–Cancer facts about types of cancer

-

–Cancer treatments and procedures

-

–Accessing information, formats such as websites, apps

-

–

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Teenage Cancer Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of Teenage Cancer Trust. None of the funding bodies have been involved with study concept, design, or decision to submit the manuscript. This manuscript has not been published or submitted elsewhere but it has been presented in part at the second Global AYA Cancer Congress in Atlanta in December 2017. The presentation is not publicly available.

Footnotes

Disclosure

LAF, SM, and JC are funded by Teenage Cancer Trust. RMT and SL are funded by NIHR, and AM is funded by Sarcoma UK. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Author contributions

RMT and LAF designed and co-ordinated the study; all the authors were involved in data collection; RMT, LAF, SL, and AM performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Wicks L, Mitchell A. The adolescent cancer experience: loss of control and benefit finding. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19(6):778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dieluweit U, Debatin KM, Grabow D, et al. Social outcomes of long-term survivors of adolescent cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(12):1277–1284. doi: 10.1002/pon.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zebrack BJ, Mills J, Weitzman TS. Health and supportive care needs of young adult cancer patients and survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(2):137–145. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119(1):201–214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson F, Hibbins S, Grew T, et al. How young people describe the impact of living with and beyond a cancer diagnosis: feasibility of using social media as a research method. Psychooncology. 2016;25(11):1317–1323. doi: 10.1002/pon.4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Conner-von S. Coping with cancer: a Web-based educational program for early and middle adolescents. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2009;26(4):230–241. doi: 10.1177/1043454209334417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fern LA, Taylor RM, Whelan J, et al. The art of age-appropriate care: reflecting on a conceptual model of the cancer experience for teenagers and young adults. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(5):E27. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318288d3ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moody L, Turner A, Osmond J, Hooker L, Kosmala-Anderson J, Batehup L. Web-based self-management for young cancer survivors: consideration of user requirements and barriers to implementation. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):188–200. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor RM, Mohain J, Gibson F, Solanki A, Whelan J, Fern LA. Novel participatory methods of involving patients in research: naming and branding a longitudinal cohort study, BRIGHTLIGHT. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(20):20. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treadgold CL, Kuperberg A. Been there, done that, wrote the blog: the choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4842–4849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergold J, Thomas S. Participatory research methods: a methodological approach in motion. Qualitative Social Research. 2012;13(1):30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor RM, Fern LA, Solanki A, et al. Development and validation of the BRIGHTLIGHT Survey, a patient-reported experience measure for young people with cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:107. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrol E, Groszmann M, Pitman A, Hough R, Taylor RM, Aref-Adib G. Exploring the digital technology preferences of teenagers and young adults (TYA) with cancer and survivors: a cross-sectional service evaluation questionnaire. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(6):670–682. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0618-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou W-Yings, Moskowitz M. Social media use in adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;9:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dominguez M, Sapina L. “Others Like Me”. An approach to the use of the internet and social networks in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32(4):885–891. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lal S, Nguyen V, Theriault J. Seeking mental health information and support online: experiences and perspectives of young people receiving treatment for first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(3):324–330. doi: 10.1111/eip.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stinson J, Gupta A, Dupuis F, et al. Usability testing of an online self-management program for adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2015;32(2):70–82. doi: 10.1177/1043454214543021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen A, Howell D, Edwards E, Warde P, Matthew A, Jones J. (Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations).The Experience of Patients with Early-Stage Testicular Cancer During the Transition from Active Treatment to Follow-up Surveillance. 2016;34 doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keegan TH, Fau LD, Kato I. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. Journal of cancer survivorship: research and practice. 2012;6(3):239–250. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson K, Palmer S, Dyson G, Adolescents DG. Adolescents & young adults: issues in transition from active therapy into follow-up care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roper K, Cooley ME, Mcdermott K, Fawcett J. Health-related quality of life after treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma in young adults. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(4):349–360. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.349-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson P, Mcdonald FE, Orchard P. A new Australian online and phone mental health support service for young people living with cancer. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(2):165–169. doi: 10.1177/1039856213519144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]