Abstract

Background

Awareness of decisions perceived as serious by diverse older adults and their surrogate decision makers would allow clinicians to provide support in the decision-making process.

Objectives

To elicit decisions perceived as serious, difficult, or important by diverse older adults and surrogates and explore what helped them make those decisions.

Design

Focus groups with diverse English- and Spanish-speaking older adults and surrogates, in which participants were asked to recall serious, difficult, or important medical decisions and what helped them make those decisions.

Setting

Participants were recruited from clinics, support groups and senior centers.

Participants

We conducted 13 focus groups, including 69 adults. Mean patient age was 78 (range 64 – 89), and that of surrogates was 57 (range 33 – 76); 29% were African American, 26% white, 26% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 19% were Latino.

Measurements

We used thematic analysis to analyze transcripts.

Results

We identified 168 decisions. Patients across all racial/ethnic groups frequently recalled cancer treatment decisions and decisions about chronic illness management. Surrogates described decisions about transitions in care and medical crises. Patients valued self-sufficiency, maximizing survival, and relied on personal experiences as often as medical advice. Across all racial/ethnic groups, surrogates valued avoiding suffering for loved ones.

Conclusion

Diverse older adults and surrogates perceive both life-threatening illness and day-to-day decisions about chronic disease as serious, difficult, or important. Surrogates’ goal to avoid patient suffering may differ from patients’ priorities of self-sufficiency and maximizing survival. Clinicians should support patients and surrogates to identify decisions that are important or difficult, and learn about the values and information sources they bring to decision making. With this knowledge, clinicians can tailor decision support and achieve patient-centered care.

Keywords: medical decision-making, advance care planning, serious illness, patient-centered care

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine identifies patient-centeredness (i.e., aligning care to the values and preferences of individuals) as an aim of high-quality healthcare.1 Clinicians can promote patient-centeredness by supporting patients and surrogate decision-makers in the process of shared decision making.2 Yet, for clinicians to support shared decision making, all parties (i.e., clinicians, patients, and surrogates) must first identify that they face a decision with options, and choose to make the decision together.3

Although many patients and surrogates would like to engage in shared decision making,4–6 engagement is often hampered by limited health literacy and English proficiency, mistrust among diverse populations, poor communication with clinicians, and disempowerment.7–10 Clinicians may choose not to involve patients in certain decisions,11 or not appreciate all the decisions with which older adults and surrogates struggle. Greater awareness of the kinds of decisions patients and surrogates perceive as serious may help clinicians decide when to engage in shared decision making. Furthermore, by learning the values and information sources on which older adults and surrogates rely, clinicians can better tailor their decision making guidance, leading to more patient-centered care.

Prior studies have examined how characteristics of patients12–14 or clinical situations15–17 affect how much of a role patients desire in decision making. Other studies have explored health-related values for patients with cancer, such as self-sufficiency and spirituality, that patients apply to decision making,18,19 and described how surrogates approach advance care planning or end-of-life decisions, such as by applying surrogate’s own values.20,21 However, no prior study has explored the kinds of decisions that older adults and surrogate decision makers perceive as serious, difficult, or important and what helps patients and surrogates make these decisions.

We undertook this qualitative study to learn more about serious decisions that older, English- and Spanish-speaking adults from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds and their surrogates made, and what helped them make those decisions. We aimed to describe themes that patients and surrogates had in common and where they diverged, and to describe variation across racial and ethnic groups.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Thirteen focus groups were conducted at three urban hospitals between 2010 and 2011, as previously described.22,23 A convenience sample was recruited from clinics, support groups, and senior centers affiliated with safety-net and veterans’ hospitals. Participants were contacted as part of a larger research participation recruitment effort, first via mailed opt-out cards, then by phone.

Participants provided demographic information via a phone eligibility screen. English- and Spanish-speaking participants were eligible if they were 65 years of age or older and had made a serious medical decision for themselves, or were 18 years of age or older and had made a serious medical decision for another person. We excluded participants with dementia, deafness, or blindness, and those who demonstrated moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment (<19/50 on the Telephone Interview Cognitive Status Questionnaire24). Participants were asked to self-report their health status, and their health literacy, defined by a well-validated question concerning their confidence filling out medical forms.25,26 Participants who answered “not at all,” “a little,” or “somewhat” confident were categorized as “limited health literacy,” versus those who responded “confident” to “very confident.” The institutional review boards of participating institutions approved this study and participants provided written informed consent.

When we designed this study, we conceived the patient and surrogate roles as separate, and our recruitment strategy and data collection reflect that separation. However, >80% of participants discussed experiences as both a patient and a surrogate. Therefore, we combined both groups in the analysis and report participants’ contributions according to the perspective from which they spoke. When participants described decisions for themselves they are referred to as “patients,” and when they described decisions for others they are referred to as “surrogates.” We have also included ID numbers, with ID S1-S31 assigned to surrogates and ID P1-P38 assigned to patients. Participants could report more than one decision; thus, the number of decisions identified could exceed the number of participants.

Focus Groups

We created a focus group guide with input from experts in the fields of geriatrics, decision making, health literacy, and advance care planning. Participants in both the groups that were focused on the patient and surrogate experience were asked to describe serious medical decisions they had made and that they perceived as significant, important, or difficult, hereafter called “serious decisions.” Examples of serious decisions included decisions about emergency surgery, chemotherapy, or life-prolonging procedures such as mechanical ventilation. They were further probed to describe what helped them make serious decisions and who was involved in the decision-making process (see Supplemental Table for focus group guide). The moderators frequently summarized participants’ comments and asked for confirmation of the moderators’ understanding. Groups lasted 90 minutes, and were moderated by an advance care planning specialist (RS), a native Spanish speaker for Spanish language groups, and co-moderated by a co-author (RM), none of whom had a physician-patient relationship with any of the participants. We continued to conduct focus groups until we reached thematic saturation.

Data Analysis

All focus groups were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. We used thematic analysis, including transcript data familiarization, codebook development, transcript indexing and coding using NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd, authors R.S., R.M.) and manual coding (author L.P.), and synthesizing overarching themes. All quotes that described decision making experiences and how participants made decisions were excerpted and coded.3,27 The constant comparative method was used to refine the coding scheme.28 We determined that thematic saturation was reached when a stable set of themes emerged, and subsequent focus groups did not yield new themes.29 Trustworthiness of methods was achieved by clear inclusion/exclusion criteria, a standardized focus group outline and coding manual, as well as an audit trail for coding. Coders achieved 84% agreement and disagreements were resolved by consensus. Themes were analyzed and presented as 1) specific to the patient perspective, 2) specific to the surrogate perspective, 3) common to the patient and surrogate perspective, and 4) trends by race/ethnicity.

Results

A total of 301 adults were contacted by mail for participation in a series of research studies, 31 of whom refused by opt-out cards. We then contacted a consecutive sample of 114 participants by phone, of which 32 refused to participate and 13 were ineligible, thus our study sample included 69 adults. We conducted 7 focus groups where participants were recruited as patients (n = 38, 4 mixed race/ethnicity and 3 Latino-only groups, group size range 3 to 6 participants) and 6 focus groups where participants were recruited as surrogates (n = 31, 2 mixed race/ethnicity groups, 2 African-American, and 2 Asian-American, group size range 3 to 8 participants). The mean age of patient enrollees was 78 years (range 64-89), and of surrogates, 57 years (range 33-76), and 74% of the cohort were non-white (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| All (n = 69) |

|

|---|---|

| Age, mean [range]; standard deviation (SD) | |

| Patients | 78 [64 – 89]; SD 8 |

| Surrogates | 57 [33 – 76]; SD 10 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| African American | 20 (29) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 18 (26) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 13 (19) |

| White | 18 (26) |

| Female, n (%) | 18 (48) |

| Spanish-speaking, n (%) | 13 (19) |

| Self-Reported Health Status, n (%) | |

| Excellent to Good | 44 (64) |

| Fair to Poor | 25 (36) |

| Limited Health Literacy, n (%) | 15 (22) |

Participants recalled 168 serious decisions, including 99 (59%) as patients, and 69 (41%) as surrogates. Five overarching decision themes were identified: decisions about cancer treatment, chronic illness, advance care planning, acute medical crises, and transitions (e.g. from acute care to hospice) (Table 2). Two themes of what helped participants make decisions were values and information sources (Table 3).

Table 2.

Categories and sample quotes of kinds of decisions participants considered serious, difficult or important. Quotes for each decision type are from either a patient perspective or surrogate decision-maker perspective.

| Decision Type | Patient or surrogate | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer treatment | ||

| Medical cancer treatment | Surrogate | The doctor examined her and took some blood tests and was telling me that she had a hidden cancer of some sort, that her life expectancy was pretty short.... So the real question was whether or not to do something about it and to talk it over with my brother. ... Do you want to put your mother through a lot of tests for—that are very inpatient and she’s had a great life and all that. It’s kind of like getting me to think maybe about just not doing anything which I finally decide not to do anything. – ID P28, Man, White, age range 80-89 |

| Cancer Surgery | Patient | The one that was most difficult for me was when I got a blood test showed that I had prostate cancer and so the physician I went to wanted to wait and watch… I decided to have surgery. – ID P29, Man, White, age range 80-89 |

| Chronic illness management | ||

| Chronic medical treatment | Patient | Regarding my pills, I have made a decision to take a medicine that comes from vegetables. The doctor doesn’t know this. He always finds my blood fine and so, I believe that I am doing fine. – ID P33, Man, Latino, age range 60-69 |

| Elective surgery | Surrogate | Well, I had to make a decision for my wife. I decided that she should have a hernia surgery and surgery on both of her knees. And I am the one who makes all the decisions for her. – ID P25, Man, Latino, age range 70-79 |

| Transitions at the end of life | ||

| Surrogate | We made a decision all of us, as a family, because she was hospitalized due to her stroke … whether to leave her in the hospital or take her home. We decided to take her home and made the commitment to take care of her in shifts. – ID P18, Woman, Latina, age range 80-89 | |

| Advance Care Planning | ||

| Treatment Preferences | Patient | So my directive basically says, “I don’t want to be kept alive artificially. If the doctors say there’s not going to be any quality of life going forward, you know, just end it.” - ID S7, Man, White, age range 70-79 |

| Choice of surrogate | Patient | I knew that I had to have somebody and it happens to be my nephew and he agrees with me that I could take care of myself as long as I could, of course. – ID P14, Man, White, age range 80-89 |

| Acute Medical Crisis | ||

| Life-sustaining treatment | Surrogate | So I have to make a decision then. She was on the life support too… So the doctor explained… there’s no way; she’s not going to make it, right. Don’t let her suffer... So I had to sign papers to pull the plug out. – ID S11, Woman, African-American, age range 40-49 |

| Acute Surgery | Patient | I’ve had gallbladder surgery a while ago, but nobody helped me in making that decision because the doctor told me that it was necessary to do it and I couldn’t live without doing that surgery. – ID P18, Woman, Latina, age range 80-89 |

| Acute medical treatment | Surrogate | 18 years ago, my first grandson was born. And I had to make a decision on the spot because my daughter couldn’t give birth to her child. So, I told the doctor- He needed to give her a shot in her hip and yes, I made that decision. – ID P20, Woman, Latina, age range 60-69 |

Table 3.

Categories and representative quotes about how participants made serious or difficult decisions. Quotes are organized into “values” or “information sources,” and by patient or surrogate perspective.

| How Patients Made Decisions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patient or Surrogate | Quote | |

|

Values Self sufficiency |

Patient | When it’s time for me to decline, Lord, just let me go and just go, but I don’t want to wake up – somebody saying, “Keep her.” Keep me for what? If I can’t get up and do for myself, I don’t want to be here. –ID S22, Woman, African-American, age range 50-59 |

| Surrogate | His independence is very important to him. So I would say you need to know as much as you can about that person. –ID S8, Woman, African-American, age range 60-69 | |

| Survival | Patient | But the biggest thing that I had was a spirit of survival. I wasn’t afraid; if I was born to die why would I be afraid? So, I said, “I want this one [treatment],” since it was the only one that guaranteed me a bit more life. – ID P24, Man, Latino, age range 70-79 |

| Surrogate | You know, eventually a few months later, he died but I didn’t like that doctor said, “He’s old. We should just let him go.” It’s–to me then, it was like murder. If you can save it, you should save it, rather than just say, “Oh, he’s 90 years old. Let him go.” – ID S14, Woman, Asian, age range 60-69 | |

| Avoiding suffering | Patient | I don’t believe in unnecessary prolongation of life just if it hasn’t any quality and the end is going to be the same. – ID P8, Woman, White, age range 80-89 |

| Surrogate | Concerning my mother, she was suffering a lot…I asked God to take her, because I didn’t want to see her suffering. If it would have been that they were giving her life artificially, I would have said to remove everything and to let her go in peace. –ID P24, Man, Latino, age range 70-79 | |

|

Information Medical advice |

Patient | Yes, the doctor’s opinion. I always like it because…they have to give me options, that is why they have studied to be doctors. –ID P26, Man, Latino, age range 70-79 |

| Family opinion | Patient | Yes, my children gave me advice. But I had already decided to do it. –ID P17, Woman, Latina, age range 70-79 |

| Surrogate | So she made me the executrix and then the advance directive had to be put in place…I tried to take into consideration that my mother—that was my mother’s mother–and then also my siblings as well, so I did allow them to help to make the decision.–ID S13, Woman, African-American, age range 50-59 | |

| Independent research | Patient | I go to every publication I could and I just did reading and that helped me make up my mind. – ID P29, Man, White, age range 80-89 |

| Experience | Patient | But anyway, my mother passed in 2000 and she had cancer for like three years, lung cancer, and she didn’t know she had cancer…the little clinic and staff was treating her for asthma. …they never did an x-ray on her chest. So that’s how I know to get x-rays… and when I found out that I had cancer. – ID S11, Woman, African-American, age range 40-49 |

| Surrogate | These things are related to old age. We have seen them in our parents, our grandparents and the thing is that now it’s our turn, it is logic. That is how the human body works; everything that is born must die. – ID P26, Man, Latino, age range 70-79 | |

Kinds of Serious Decisions

Patients

Cancer decisions, particularly about surgical management of breast or prostate cancer, were frequently perceived as serious by patients. A Latino male patient (ID P25) recalled, “Two weeks ago the doctors have detected that I have prostate cancer. Right now it is stable and they told me that I had three options: Chemotherapy, to get checked every three months, … [or] radiation. So, I decided to get checked every three months and well, so far I have no problem.”

Decisions about chronic illness, such as osteoporosis or diabetes, were also identified as serious by many participants in our study. A Latino man (ID P23) said, “I am not taking any diabetes medicines because…I don’t know how right they are. I don’t feel that I have diabetes.” An African-American man (ID P37) recognized the gravity of his decision to skip medications in retrospect: “I think I outsmarted myself in thinking that I was taking too many pills and I could outsmart my evaluation and my medication. So I started slipping a little. I wouldn’t take it every day.” Decisions about chronic illness management were almost exclusively described by participants enrolled in the study as patients.

Surrogates

Surrogates often described decisions about transitions in care, such as changes in healthcare goals (e.g., from acute care to comfort-focused) or care settings (e.g., from home to nursing home). Only surrogates reported this kind of decision. One African-American woman (ID S3) recalled, “In the end when his body could no longer take food or fluids artificially, that was the time to stop it and disconnect…It’s time to let him go and that was a hard decision, too.”

Patients and Surrogates

Patients and surrogates alike recalled decisions about advance care planning, including preferences about future care and naming surrogate decision-makers. One white female patient (ID P8) said, “I make my own decisions and I already have on record here what I want done at end of life. I don’t want any unusual resuscitation or anything.” Decisions about acute medical crises were also common to both patients and surrogates. Patients described decisions about emergency surgery, such as cholecystectomy. A Latina female patient (ID P18) said, “I’ve had gallbladder surgery a while ago, but nobody helped me in making that decision because the doctor told me that it was necessary to do it and I couldn’t live without doing that surgery.” Other patients described seeking medical attention for acute symptoms. A Latino male patient (ID P33) said, “I started feeling a sharp pain here. The pain was so strong that I had trouble walking. So I thought, ‘I must consult this to my doctor because I can’t be with this pain the entire time.’ I went to the emergency [room].” Surrogates typically described emergency decisions about life-sustaining treatment. An African-American male surrogate (ID S30) recalled, “My mom’s had an aneurysm, but they say she was brain-dead, they wanted to pull the plug. I said, ‘No’.”

Themes by Race/Ethnicity

Patients and surrogates across all racial and ethnic groups in our study consistently reported the same decision types. However, decisions about advance care planning were more commonly described by white patients than patients of other race/ethnicities. Among surrogates, African-American participants often reported decisions for loved ones in acute medical crises. An African-American female surrogate (ID S31) recalled, “My son got hit with a hit-and-run and we had to make a decision within 24 hours… [to] take him off the life support.” African-American and Asian surrogates frequently described decisions about transitions in care for loved ones, a topic that was less common among Latino and white surrogates.

Factors that Helped Participants Make Serious Decisions: Values

Patients

Patients frequently cited the value of self-sufficiency, the ability to make independent decisions or care for themselves, as important in decision making. For example, an Asian male patient (ID P27) said, “I think if I’m going to be the one who’s dying, I want my decision to stay. I mean I don’t want my family tell me, ‘No, you can’t do it that. You have to do it our way.’” Patients also valued maximizing survival, spiritual or religious beliefs and avoiding suffering. One African-American female patient (ID S13) described, “The goal was to do whatever it takes to stay alive and so I made that decision.” A white male patient (ID P11) said, “In my case, there was my faith and my trust in the scriptures at the time of my decision and I was nudged in the direction I went.”

Surrogates

The dominant value reported by surrogates in our study was avoiding suffering for the patient. A white male surrogate (ID P28) explained, “Her quality of life was very good to the end. She died in her sleep… putting her through the severity of the tests and the invasion of whatever surgery that might be following from all that would have made her a miserable person and she would have died in a lot of agony.”

Some surrogates felt that religion played a role in their decisions. Many surrogates described feeling like decisions were out of their hands because their fate had been decided by God. A Latino male surrogate (ID P26) said, “The Lord is the Lord of my life, at least mine and my wife’s, and He is the One who decides the day He takes us.” Similarly, an Asian female surrogate (ID S29) said, “If I’m the wife and my husband is suffering, you know, I think my God will not let him suffer that much, you know, as I believe that He loves everyone by taking off the tube or stop the pain or the suffering that’s killing him.”

Factors that Helped Participants Make Serious Decisions: Information Sources

Patients

Patients frequently described relying on their personal experience, as well as medical advice, family opinion and their personal research. An African-American female patient (ID S3) recalled, “The experience I had with my husband, my brother… made me get my paperwork in order.” A Latino male patient (ID P33) stated, “It is very positive to talk to your doctor because the doctor encourages us,” and a white male patient (ID P9) said, “My daughter is the one that pushed me on this.” An African-American female patient (ID S16) commented, “I was looking up everything as it relates to cancer.”

Surrogates

Surrogates’ information sources were similar to patients’ except they did not describe researching decisions. Surrogates relied on personal experience, especially knowledge of the patient. An African-American female surrogate (ID S25) said, “I kind of got to know my grandmother in a way that I hadn’t known her before for spending so much more time with her.” Family opinion was also important to surrogates. “I have four siblings and so we’re all strong willed and so we definitely had a difference of opinion,” recalled an African-American female surrogate (ID S16). Surrogates also relied on medical advice. An Asian female surrogate (ID S27) recalled, “Of course, I want to try my best to keep him alive, but the doctors say, ‘Oh, at that age, if you put the tube in and something will even hurt him more.’ So then, you know, when the doctor explained to me more details about that and that kind of changed—and I changed my mind and I say, ‘O.K., so don’t revive him.’” Some surrogates sought multiple information sources. An African-American female surrogate (ID S5) said, “My husband left the final decisions to me and I prayed on it; I spoke with people in the medical profession, my mom, nurse friends, to explain what the DNR meant.”

Themes by Race/Ethnicity

Participants across racial and ethnic groups described similar values and information sources. Self-sufficiency in decision making was the most commonly cited value for all patients except Latino patients, whose main goals were maximizing survival and honoring religion in decision making. Both African-American and Latino patients discussed how personal experiences guided them more often than medical advice, whereas Asian patients frequently mentioned relying on medical advice.

All surrogate groups emphasized the importance of avoiding suffering for loved ones, incorporating medical advice and relying on religion. African-American and Asian surrogates also described respecting their loved ones’ autonomy, such as an African-American female surrogate (ID S5) who said, “And, of course, the advance directive helps because everything’s in black and white and when the person made a decision prior, they, you know, had a clear mind.”

Discussion

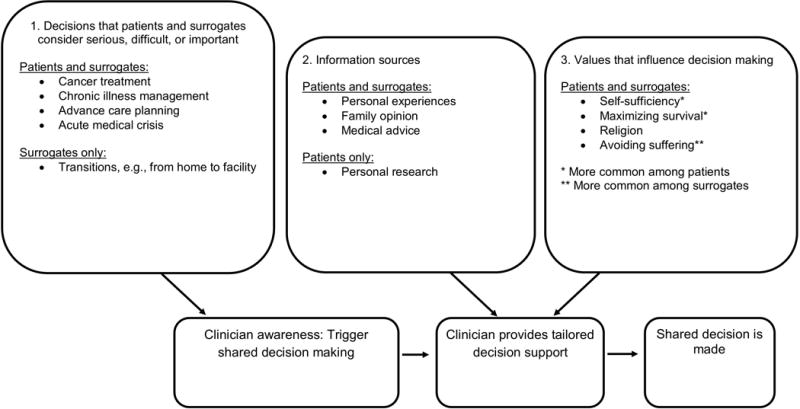

Diverse English- and Spanish-speaking older adults and surrogate decision makers reported making a range of decisions they perceived as serious, difficult, or important, and a range of values and information sources that helped them make these decisions. Most clinicians may be aware of the need to support patients and surrogates in decisions such as cancer treatment and for life-threatening illness. They may not be aware that diverse patients and their surrogates perceive as serious, and need support for, other decisions such as day-to-day chronic illness management or transitions to nursing home care, as our novel results demonstrate. Awareness of the decisions that older adult patients and surrogates perceive as serious is essential to trigger clinicians to engage in shared decision making (Figure 1). Using the framework of the “collaborative care” model, clinicians can help patients and surrogates identify the problems for which they need support.42 Then, based on patients and surrogates desired role in decision making, clinicians may tailor a plan to help with problem-solving skills while ensuring patient/surrogate values and personal and social context, as described in this study, are incorporated into the shared decision making process to achieve patient-centered care.43

Figure 1.

A schematic that demonstrates how knowledge of the kinds of decisions that patients and surrogates find to be serious, difficult, or important (Box 1) triggers clinicians to engage patients in shared decision making. Appreciation of the information sources (Box 2) and values (Box 3) on which patients and surrogates rely also allows clinicians to provide tailored decision making support.

Surrogate decision-makers for older adults in our study commonly, and uniquely, recalled decisions about transitions in care, such as nursing home placement, as well as making substitute decisions during medical crises. These findings are consistent with the reality that most patients lose decision-making capacity at the end of life. Among surrogates, decisions about care transitions were particularly common among African-American and Asian participants. The less frequent discussion about advance care planning among non-white participants than among white participants in this cohort is consistent with the literature on advance directive completion.30 Less advance care planning among non-white groups may explain increased difficulty with decisions about transitions and acute medical crises among surrogates. This and other studies demonstrate the importance of preparing surrogates for substitute decision making, which may reduce surrogates’ decisional conflict with end of life decisions.31 It also underscores the need for shared decision making models of support for both patients and surrogates.27,32 Future studies to better characterize how decisions about transitions in care are made and how to best honor patient preferences in these circumstances are warranted.

Participant perceptions of clinician involvement in decision making were generally positive. However, in our cohort, advice from clinicians was only one thread in the tapestry of values, experiences, and trusted sources that informed diverse older adults’ and surrogates’ serious decisions. Many of the values and information sources participants named in our study were consistent with prior research in specific settings. For example, the importance to patients of maintaining control over decisions were echoed in prior studies of veterans with cancer.18,19,33 Furthermore, expression by patients and surrogates that their fates were decided by God has previously been observed in patients across a range of ethnic groups.19,34 In addition, the observation that lived experiences are key to how individuals approach decisions is consistent with a prior study among women deciding about participation in a breast cancer prevention trial,35 and surrogates making end-of-life decisions.20 That African Americans and Latino patients in this cohort discussed how personal experiences guided them more often than medical advice may reflect the well-documented mistrust of the medical system by historically marginalized populations. 36,37 Despite the presence of these similar themes in specific populations in prior studies, our study contributes the novel finding that these values are consistent in a diverse group of older adults and surrogate decision makers, and across a wide range of decision types.

This study also highlighted an important mismatch in the goals of decision making among older adult patients, who emphasized self-sufficiency and control, versus surrogates, who emphasized minimizing suffering. The use of surrogates’ own values and goals may hinder substituted judgment when making decisions for older adult patients.20,21,38 Discussion of values among patients and surrogates in advance may help to reconcile these differences through mutual understanding, as well as allow patients and surrogates to discuss possible leeway in surrogate decision making in advance of a medical crisis.39

Strengths of this study include the diversity of race, ethnicity, and health status of participants, the inclusion of both patient and surrogate perspectives, and the inclusion of decisions across the illness trajectory, not just at the end of life. The open-ended, focus group format may have also allowed participants to recall more experiences than they might have in questionnaires. However, several considerations are important in the interpretation of our findings. Participants were recruited from one geographic area, limiting the generalizability of our results. In addition, given the qualitative nature of this study, we did not survey participants about every important decision or everything that helped their decision making. Our results were limited to the decisions that participants felt comfortable sharing.

In conclusion, diverse older patients and surrogates perceive a range of decisions as serious, difficult, or important, including decisions about day-to-day chronic illness management and transitions in care. With awareness of diverse older adults’ and surrogates’ perceptions of serious decisions, clinicians may provide support in the decision-making process that is tailored to individual needs. Clinicians should also explore the range of values, experiences, sources of advice and cultural beliefs that patients and surrogates use to make serious decisions, and be mindful of possible differences in values between patients and surrogates in serious decision making.40 Appreciation of the values and information sources on which diverse older adults and surrogates rely should also guide the development of decision support tools for serious medical decisions.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table. The focus group guide, including specific directions to patient and surrogate groups. For additional findings from these groups, please see Su et al. and McMahan et al.22,23

Impact statement.

We certify that this work is novel clinical research. The potential impact of this research on clinical care or health policy includes the following: Knowledge of the kinds of medical decisions that diverse older adults and surrogate decision makers perceive as serious will help clinicians identify opportunities to support them in decision-making. Understanding the values and information sources that diverse older adults and surrogates rely on will also guide the development of decision support tools for serious medical decisions.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Dr. Petrillo was supported by a Veterans Affairs Quality Scholar fellowship. Dr. Sudore was supported by a VA Investigator Initiated Research grant, 11-110-2, an NIA R01 AG045043, a PCORI career development award (CDR-1306-01500, and grants from the UCSF Tideswell Foundation, American Cancer Society, and John and Wauna Harman Foundation.

Sponsor’s role: The funding sources that supported the authors had no role in the design or analysis of the study, nor in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Presentations: This work was presented at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Annual Assembly in March 2016.

Conflict of Interest: All authors report no personal or financial conflicts of interest.

Author contributions: Dr. Sudore designed and conducted the focus groups. Dr. Petrillo designed and conducted the qualitative analysis. Mr. McMahan assisted with the focus groups and qualitative analysis. All authors were involved in the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared Decision Making — The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gravel K, Légaré F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp K. Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol ESMO. 2010;21(6):1145–1151. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruera E, Sweeney C, Calder K, Palmer L, Benisch-Tolley S. Patient Preferences Versus Physician Perceptions of Treatment Decisions in Cancer Care. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2883–2885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Bibbins-Domingo K, Williams BA, Schillinger D. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient–physician communication. Bridg Int Divide Health Lit Res. 2009;75(3):398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer AM, Parker MM, Schillinger D, et al. Associations Between Antidepressant Adherence and Shared Decision-Making, Patient–Provider Trust, and Communication Among Adults with Diabetes: Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(8):1139–1147. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2845-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li DJ, Park Y, Vachharajani N, Aung WY, Garonzik-Wang J, Chapman WC. Physician-Patient Communication is Associated With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening in Chronic Liver Disease Patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(5) doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000747. http://journals.lww.com/jcge/Fulltext/2017/05000/Physician_Patient_Communication_is_Associated_With.14.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams BA, Lindquist K, Sudore RL, Covinsky KE, Walter LC. Screening mammography in older women: Effect of wealth and prognosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):514–520. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitney SN, McCullough LB. Physicians’ Silent Decisions: Because Patient Autonomy Does Not Always Come First. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7(7):33–38. doi: 10.1080/15265160701399735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brom L, Pasman HRW, Widdershoven GAM, et al. Patients’ Preferences for Participation in Treatment Decision-Making at the End of Life: Qualitative Interviews with Advanced Cancer Patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R. Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: A narrative review. Patient Educ Couns. 60(2):102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson SC, Pitts JS, Schwankovsky L. Preferences for involvement in medical decision-making: situational and demographic influences. Patient Educ Couns. 1993;22(3):133–140. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(93)90093-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, Moskowitz MA. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy: decision making and information-seeking preferences among medical patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(1):23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02596485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butow PN, Maclean M, Dunn SM, Tattersall MHN, Boyer MJ. The dynamics of change: Cancer patients’ preferences for information, involvement and support. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(9):857–863. doi: 10.1023/a:1008284006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naik AD, Martin LA, Moye J, Karel MJ. Health Values and Treatment Goals of Older, Multimorbid Adults Facing Life-Threatening Illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):625–631. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karel MJ, Mulligan EA, Walder A, Martin LA, Moye J, Naik AD. Valued life abilities among veteran cancer survivors. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2016;19(3):679–690. doi: 10.1111/hex.12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vig EK, Taylor JS, Starks H, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Beyond Substituted Judgment: How Surrogates Navigate End-of-Life Decision-Making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1688–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Surviving surrogate decision-making: what helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1274–1279. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su CT, McMahan RD, Williams BA, Sharma RK, Sudore RL. Family Matters: Effects of Birth Order, Culture, and Family Dynamics on Surrogate Decision Making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(1):175–182. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, Sudore RL. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook SE, Marsiske M, McCoy KJM. The use of the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M) in the detection of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;22(2):103–109. doi: 10.1177/0891988708328214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shadbolt B, Barresi J, Craft P. Self-rated health as a predictor of survival among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;20(10):2514–2519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar U, Schillinger D, López A, Sudore R. Validation of Self-Reported Health Literacy Questions Among Diverse English and Spanish-Speaking Populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):265–271. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared Decision Making: A Model for Clinical Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaser B, Strauss A. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guest Greg, Bunce Arwen, Johnson Laura. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison KL, Adrion ER, Ritchie CS, Sudore RL, Smith AK. Low completion and disparities in advance care planning activities among older Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1872–1875. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiarchiaro J, Buddadhumaruk P, Arnold RM, White DB. Prior Advance Care Planning Is Associated with Less Decisional Conflict among Surrogates for Critically Ill Patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(10):1528–1533. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201504-253OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torke AM, Petronio S, Sachs GA, Helft PR, Purnell C. A Conceptual Model of the Role of Communication in Surrogate Decision Making for Hospitalized Adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun UK, Beyth RJ, Ford ME, Espadas D, McCullough LB. Decision-making styles of seriously ill male Veterans for end-of-life care: Autonomists, Altruists, Authorizers, Absolute Trusters, and Avoiders. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkins HS, Cortez JD, Hazuda HP. Cultural Beliefs About a Patient’s Right Time to Die: An Exploratory Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1240–1247. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1115-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmberg C, Waters EA, Whitehouse K, Daly M, McCaskill-Stevens W. My lived experiences are more important than your probabilities: The role of individualized risk estimates for decision making about participation in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2015;35(8):1010–1022. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15594382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and Trust in the Health Care System. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):358–365. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith AK, Lo B, Sudore R. When previously expressed wishes conflict with best interests. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1241–1245. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “Planning” in Advance Care Planning: Preparing for End-of-Life Decision Making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crawley LM, Marshall PA, Lo B, Koenig BA. Strategies for Culturally Effective End-of-Life Care. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(9):673–679. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table. The focus group guide, including specific directions to patient and surrogate groups. For additional findings from these groups, please see Su et al. and McMahan et al.22,23