Abstract

Introduction

Persistence with basal insulin therapy can be suboptimal, despite recent improvements in insulin formulations and delivery systems. Patient support programs may help increase adherence. This study evaluated the impact of the Toujeo® COACH support program, which provides patients with continuing and individualized education and advice on lifestyle changes, by assessing its effect on number of refills and days on therapy.

Methods

The study population included 1724 patients with diabetes who filled a first prescription for insulin glargine 300 U/mL (Gla-300) between April and December 2015 and received a welcome call from a Guide, and 1724 matched control patients from the Symphony Health Integrated Dataverse® prescription claims database. Control patients received Gla-300 but did not enroll in the program. These patients were matched based on age, gender, location, prior use of insulin, insulin dose, number of concomitant drugs, and copay tier.

Results

The COACH and control groups comprised 52% men and 48% women; 22% were aged 18–47 years, 23% were 48–55 years, 27% 56–61 years, and 28% ≥ 62 years. Most (99%) had used insulin in the year before receiving the welcome call. At 6 months, patients in the COACH group had refilled their prescription 3.2 times on average, compared with 2.4 times for control patients (P < 0.0001); at 9 months, the average number of refills was 4.7 and 3.6, respectively (P < 0.0001). The average number of days on therapy at 6 months was 102.2 days in the COACH group and 81.5 days in the control group (P < 0.0001); at 9 months, the average number of days on therapy was 151.9 and 121.6, respectively (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Patients in the COACH program were significantly more likely to refill their prescriptions and stay on therapy. Patient support programs such as the COACH program could be an effective way to help improve diabetes care.

Funding

Sanofi US, Inc. and McKesson Corporation.

Keywords: COACH program, Diabetes, Insulin glargine, Patient support, Treatment engagement

Introduction

Glycemic control remains the cornerstone of diabetes management, and therefore the prevention of diabetes-related microvascular complications [1]. Although early implementation of insulin therapy improves clinical outcomes in the long term [2], treatment with insulin has traditionally been associated with risk of hypoglycemia and increased body weight [3, 4], which may negatively affect patient persistence [5, 6]. Insulin glargine 300 U/mL (Gla-300) is a long-acting basal insulin analog that has been available in the USA since April 2015 and is indicated for the improvement of glycemic control in adult patients with diabetes [7]. Gla-300 offers the convenience of a once-daily injection with lower nocturnal hypoglycemia compared with insulin glargine 100 U/mL, NPH insulin, and premixed insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [8–10].

Despite significant improvements in insulin formulations and delivery systems, persistence with basal insulin treatment among patients with T2D ranges from approximately 62% for new users to 68% for experienced users in the USA [11]. Real-world studies have shown that only 20% of patients initiating insulin persist with treatment without interruptions after 1 year [12]. Patient-related and health-care provider-associated factors can contribute to poor compliance to an insulin regimen, and patient education and support can play a meaningful role in treatment implementation and continuation [6, 13].

Patient-support programs, led by either health-care professionals or lay health coaches, are known to increase therapy adherence and consequently improve clinical outcomes and reduce health-care resource utilization and costs [14], and the current American Diabetes Association treatment guidelines emphasize the role of patient education and support in the prevention of diabetes-related complications [1]. The Toujeo® COACH support program provides support for patients with diabetes initiating Gla-300 by delivering individualized educational materials and encouraging lifestyle changes for better glycemic control [15]. This analysis specifically evaluated the impact of the COACH support program on number of refills and days on therapy.

Methods

Study Design

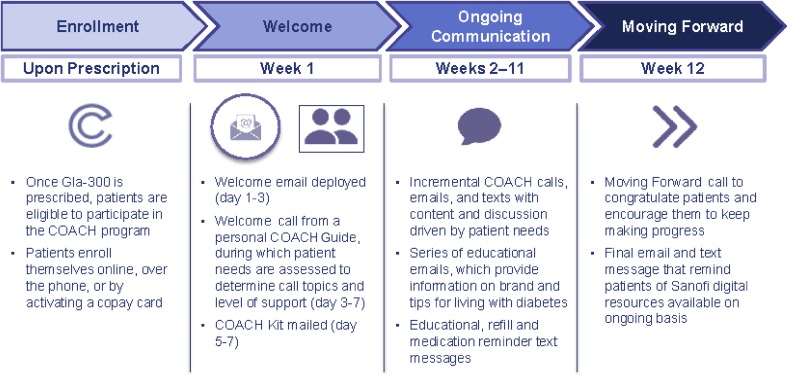

The COACH program was introduced to patients at the point of care by health providers when a prescription for Gla-300 was written. Patients who enrolled in the COACH program received a welcome call from a Guide—who, when the program started in 2015, did not have specific medical qualifications for the role of coach (registered nurses have played this role since 2017)—to identify specific disease/therapy management needs. This call was followed by a face-to-face or virtual educational session (i.e., a prerecorded webinar) presented by a certified diabetes educator. Patients had the opportunity to discuss their treatment schedules during a second dose-administration call from the Guide. Ongoing support included further contact with the Guide (e.g., additional calls/emails/text messages) to reinforce treatment goals and health-care provider recommendations, as well as webinars and access to digital tools (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the COACH support program

Patients who enrolled in the program and completed the welcome call (“enrolled patients”) between April 1, 2015 and December 31, 2015, who filled a first prescription for Gla-300 on the same day or up to 180 days after the date of the welcome call (welcome call date occurring on or before December 31, 2015), were matched 1:1 to control patients from the Symphony Health Integrated Dataverse® (IDV) prescription claims database [16] based on demographic attributes (age, gender, geographic location, prior use of insulin, insulin dose, number of concomitant drugs, and copay tier for Gla-300). The IDV database contains longitudinal patient data capturing adjudicated prescription, medical, and hospital claims across the USA, and includes > 10 billion prescription claims linked to > 220 million individual patients and claims from hospitals and physician practices for > 190 million patients [16].

Eligible patients who enrolled in the COACH program and subsequently responded to > 1 text message, or logged onto the online platform more than once, were deemed “engaged patients” for the purposes of the study. Control patients received Gla-300 but did not engage in the COACH program, although they could have enrolled in the program.

This research study used nonidentifiable data obtained by the COACH support program (COACH cohort) and the Symphony Health IDV prescription claims database (control cohort); therefore, informed consent was not required. A release form was obtained in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Outcomes Measured and Statistical Analysis

Number of refills and days on therapy were determined at 6 months and 9 months. The number of refills was calculated based on the number of claims after the first eligibility claim in the qualifying period of April 1, 2015 to December 31, 2015, whereas days on therapy (i.e., the estimated number of days that the prescription will last) were calculated as the days of Gla-300 supply summed for all product prescriptions for each qualifying patient divided by the total number of patients. A refill of the prescription would therefore indicate that the previous one was exhausted. The previous refill’s days supply were not counted in the total supply sum. Patients with only one refill had 0 days supply, which was counted in both the sum of days supply of all claims and the total number of patients.

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the COACH and control cohorts were compared using the chi-square test, whereas Student’s t test was used to compare the outcomes for the two cohorts at 6 months and 9 months of follow-up. Where applicable, the Satterthwaite approximation for degrees of freedom was used.

Patients in the study could have commercial health insurance, be enrolled in government-run programs, or pay in cash for their medication. Low-income patients or those ineligible for public programs could have received assistance with their prescriptions, including coupons, discount cards, and privately or state-funded assistance. In order to assess the impact of health insurance type on outcomes, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with interaction terms for patient type by health insurance type was used to compare patient type (COACH or control cohort) while taking into account health insurance plan type (received assistance versus no assistance).

Results

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 8523 eligible patients completed the welcome call, and 2752 completed the dose administration call (Table 1). The analyzed population included 1724 patients in the COACH program, who met all the inclusion criteria, and 1724 matched controls from the IDV database.

Table 1.

Distribution of the welcome and dose administration call outcomes during the study period

| Outcome | Welcome call | Dose administration call |

|---|---|---|

| Invalid number | 2509 | 52 |

| Wrong number | 1535 | 17 |

| Blocked number | 68 | 3 |

| Line busy | 52 | 12 |

| No answer | 117 | 39 |

| Call dropped | 488 | 64 |

| Call interrupted | 1201 | 259 |

| Requested call back | 0 | 20 |

| Voicemail | 31,081 | 3308 |

| Not available on 3rd attempt | 1428 | 188 |

| Underaged | 46 | 0 |

| Ill | 3 | 2 |

| Deceased | 23 | 2 |

| Discontinued therapy | 22 | 3 |

| Othera | 9006 | 10 |

| Eligible | 8523 | 2752 |

Values are expressed as number of patients

aCall-back time given, ineligible discontinued/no prescription, opt out, patient calling back, patient with other person

Patient baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2. The COACH cohort included 52% men and 48% women. A total of 22% of patients were aged 18–47 years, 23% were aged 48–55 years, 27% 56–61 years, and 28% ≥ 62 years. Almost all patients (99%) had used insulin in the 1-year period prior to the welcome call: 45% had used insulin glargine 100 U/mL, 54% had used another insulin, including basal or mixed formulations, and 1% were insulin naive. A total of 71% of patients in both cohorts had a copay of US $15 on their first paid Gla-300 prescription claim, with 15% having a copay of > $15, 6% having a copay of $0.01–14.99, and 8% a copay of $0. No significant differences in these variables were observed between the COACH and control cohorts. Compared with control patients, fewer COACH patients had commercial health insurance (34% vs 42%) and Medicare coverage (5% vs 12%) (P < 0.0001 for both types of coverage). Overall, 58% and 43% of COACH and control patients, respectively, received coupons/discount cards or payment aids (P < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the COACH support program and matched control patients

| COACH (n = 1724) | Control (n = 1724) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender,a n (%) | ||

| Female | 824 (48) | 824 (48) |

| Male | 900 (52) | 900 (52) |

| Age group,a n (%) | ||

| 18–47 years | 378 (22) | 378 (22) |

| 48–55 years | 404 (23) | 404 (23) |

| 56–61 years | 460 (27) | 460 (27) |

| ≥ 62 years | 482 (28) | 482 (28) |

| Pre-study insulin use,a n (%) | ||

| Insulin glargine 100 U/mL | 783 (45) | 783 (45) |

| Other insulin | 923 (54) | 923 (54) |

| Insulin naive | 18 (1) | 18 (1) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | ||

| Type 1 | 115 (6.7) | 127 (7.4) |

| Type 2 | 814 (47) | 869 (50) |

| Unknown | 795 (46) | 728 (42) |

| Health insurance plan, n (%) | ||

| Assistanceb | 1,007 (58)** | 741 (43) |

| Commercial | 579 (34)** | 720 (42) |

| Medicare | 87 (5)** | 204 (12) |

| Cash | 32 (2)** | 20 (1) |

| Managed Medicaid | 13 (1)** | 26 (2) |

| Medicaid | 6 (0.4)** | 13 (1) |

| Copay for first prescription of insulin glargine,a,c n (%) | ||

| US $0 | 141 (8.0) | 141 (8.0) |

| US $0.01–14.99 | 109 (6.0) | 109 (6.0) |

| US $15 | 1,222 (71) | 1,222 (71) |

| > US $15 | 251 (15) | 251 (15) |

| Practitioner specialty, n (%) | ||

| Endocrinology | 567 (33) | 555 (32) |

| Family medicine | 445 (26) | 443 (26) |

| Internal medicine | 296 (17) | 345 (20) |

| Family practice | 217 (13) | 174 (10) |

| Nurse practitioner | 38 (2) | 24 (1) |

| Emergency medicine | 19 (1) | 16 (1) |

| Physician assistant | 16 (1) | 24 (1) |

| Diabetes | 15 (1) | 26 (2) |

| Internal medicine/pediatrics | 15 (1) | 12 (1) |

| General practice | 12 (1) | 23 (1) |

| Unknown | 13 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Other | 0 (0)* | 68 (4) |

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding

*P < 0.05 vs control patients and **P < 0.0001 vs control patients for chi-square test

aCharacteristic used for matching patients in the COACH cohort with control patients

bIncludes coupons, discount cards, and privately or state-funded assistance programs for uninsured, low-income patients or those who are ineligible for public programs

cCopay data were missing for 1 patient in the COACH cohort, who was matched to a patient in the control cohort with missing copay data

Prescription Refills

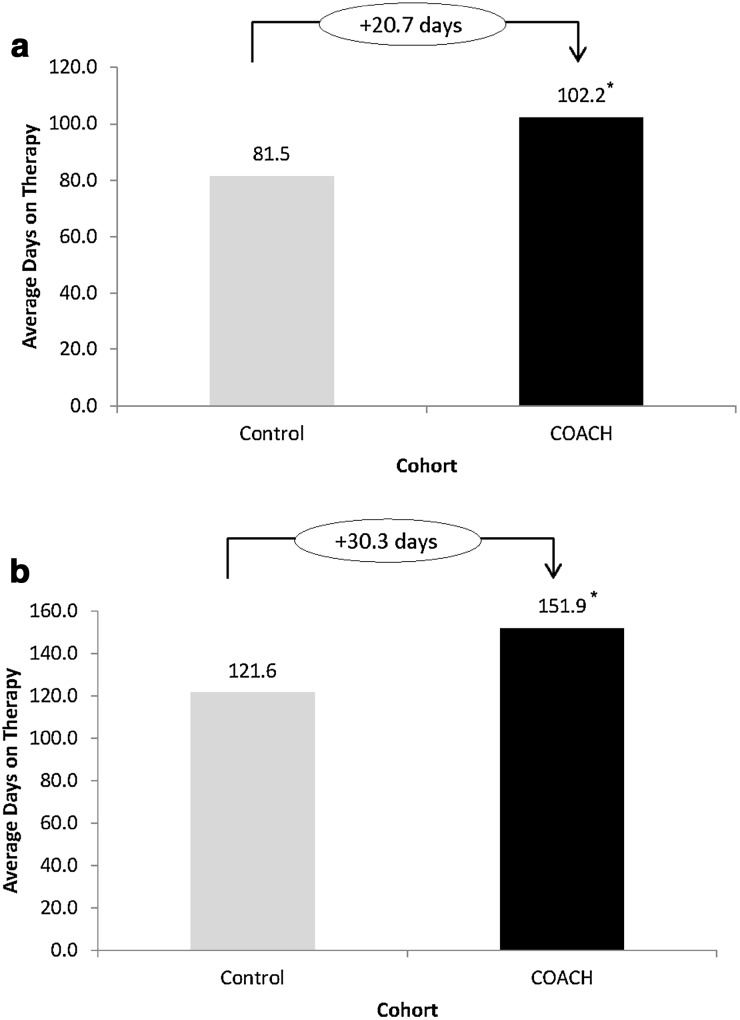

After 6 months, patients in the COACH program refilled their prescription on average 3.2 times, compared with 2.4 times for control patients; at 9 months, the average number of refills was 4.7 for the COACH cohort versus 3.6 for the control cohort (P < 0.0001 for both time points) (Fig. 2). To assess the potential impact of plan type (assistance versus no assistance) on the outcomes, an adjusted analysis of data at 9 months was also performed, which showed an absence of significant interaction between patient type and plan type (P > 0.5), and also demonstrated that the number of refills was consistently greater for patients in the COACH program than those in the control cohort across insurance plan types (P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001 for patients in the COACH cohort versus the control cohort for the assistance and no assistance groups, respectively) (Table 3).

Fig. 2a–b.

Average number of refills for patients in the COACH support program vs control patients after 6 months (a) and 9 months (b). *P < 0.0001 vs control patients

Table 3.

Average number of refills and days on therapy at 9 months for patients enrolled in the COACH support program and matched control patients who received assistance vs no assistance

| Mean number of prescription refills | Mean days on therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COACH (n = 1724) | Control (n = 1724) | COACH (n = 1724) | Control (n = 1724) | |

| Health insurance plan | ||||

| Assistance, LS mean | 4.86* (n = 1007) | 3.86 (n = 741) | 154.86** (n = 1007) | 127.76 (n = 741) |

| No assistance,a LS mean | 4.47** (n = 717) | 3.33 (n = 983) | 147.85** (n = 717) | 117.00 (n = 983) |

| Interaction term P valueb | 0.5175 | 0.5281 | ||

LS least squares

*P < 0.001 and **P < 0.0001 for COACH vs the control cohort. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the SAS® implementation of the Tukey–Kramer method

aThe no assistance subgroup included patients who had commercial insurance, who were on Medicare/Medicaid and managed Medicaid, and those who paid cash for their medication

bP interaction term for patient type (COACH, control) by health insurance plan (assistance, no assistance)

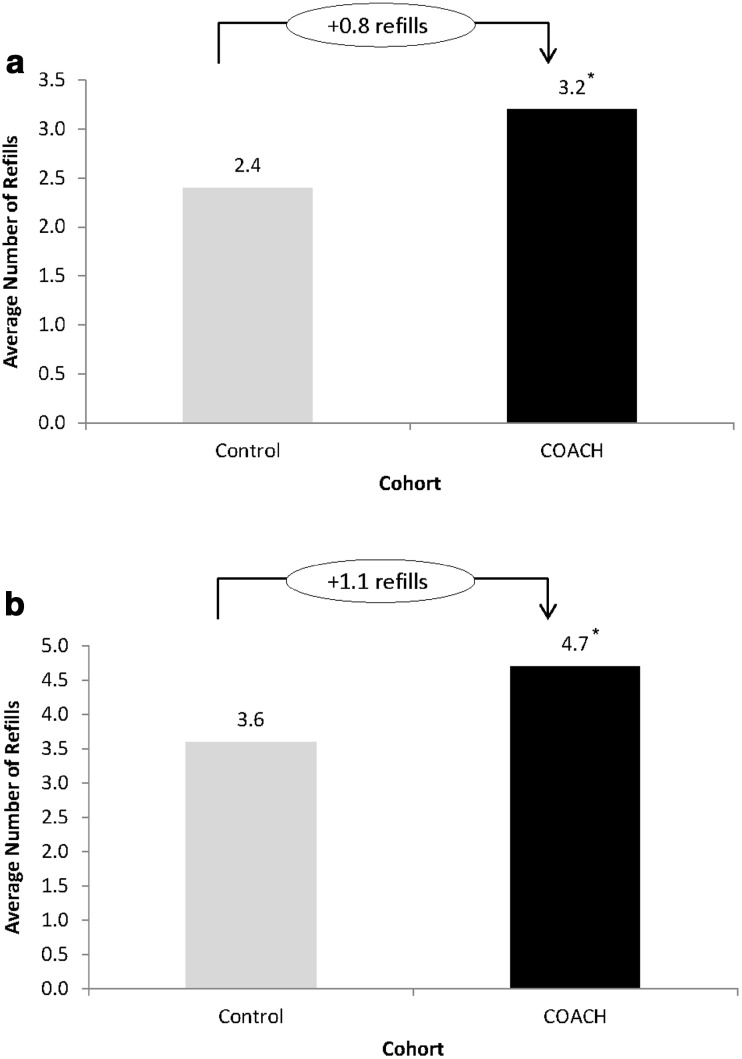

Days on Therapy

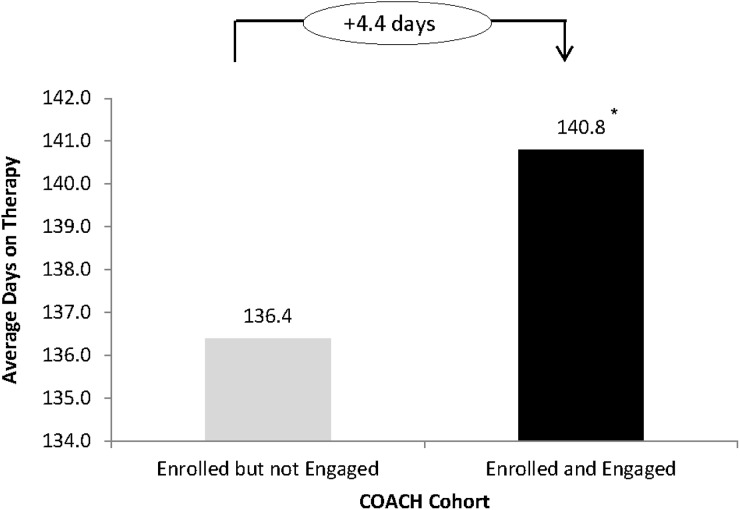

The average number of days on therapy at 6 and 9 months of follow-up was 102.2 and 151.9, respectively, for patients in the COACH cohort, and 81.5 and 121.6, respectively, for control patients (P < 0.0001 for both time points) (Fig. 3). An analysis of patients enrolled between April 2015 and August 2015 showed that “engaged” patients continued on therapy for longer than patients who “enrolled but did not engage” in the program (140.8 vs 136.4 days, respectively) (P < 0.0005) (Fig. 4). Similar to the results obtained for prescription refills, the ANOVA at 9 months showed no interaction (P > 0.5) between patient type and the two health insurance plan types (assistance versus no assistance), with a consistently higher average number of days on therapy seen with the COACH program (P < 0.0001 for patients in the COACH cohort versus the control cohort for both the assistance and no assistance groups) (Table 3).

Fig. 3a–b.

Average number of days on therapy for patients in the COACH support program vs control patients after 6 months (a) and 9 months (b). *P < 0.0001 vs control patients

Fig. 4.

Average number of days on therapy for patients in the COACH support program according to level of engagement after 6 months. 1923 COACH patients enrolled between April 2015 and August 2015 were matched based on behavioral and demographic attributes (age, gender, geographic location, prior use of insulin, insulin dose, number of concomitant drugs, and copay for Gla-300). Engaged patients completed the welcome call and responded to > 1 text message or logged on to the online platform more than once. *P < 0.0005 vs control patients

Discussion

Our findings show increased treatment engagement among patients receiving Gla-300 who enrolled in a support program with a telephone-based component designed to meet individual needs. Improvements in patient self-management and knowledge of the disease, glycemic control, and quality of life were previously reported for community-based support programs targeting different ethnicities and socioeconomic groups, as well as for individualized and culturally appropriate telephone-based interventions involving case management by nurse practitioners [17–20]. Moreover, it has been observed that coaching interventions do not necessarily need to be administered by live coaches or by health-care professionals involved in the treatment of diabetes to result in meaningful improvements in glycemic levels. The use of mobile and wireless technologies may also reduce the costs associated with the implementation of these types of programs, and expand their reach to traditionally underserved regions, such as rural areas [21–23].

A recent systematic review of mobile and wireless technologies showed that more than half of a total of 24 support programs for patients with diabetes or obesity resulted in improved outcomes, but most of them involved a small number of patients and short interventional and follow-up periods [24]. Another systematic review and network meta-analysis revealed that self-management programs without added support, or with ≤ 10 h of contact with coaches or other counselors, had practically no effect on glycemic control [25]. Our study involved more than 1700 patients enrolled in the COACH program who were followed for up to 9 months and showed increased refills and number of days on therapy.

Due to the nature of the database, no clinical outcomes such as glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and fasting blood glucose could be collected over time, hence the relationships between number of refills/days on therapy and glycemic control could not be assessed. In addition, common side effects of insulin therapy (i.e., hypoglycemia, weight gain) were not evaluated. The insulin doses patients were prescribed at 6 months and 9 months may have impacted the frequency of refills, and it is not known how insulin doses were titrated; better insulin titration in patients who received counseling and support via the COACH program may have resulted in the higher number of prescription refills. In addition, an increased number of prescription refills does not necessarily mean that the insulin was administered or dosed according to recommendations, or that the insulin was in fact used.

The use of coupons or discounts can have an impact on the utilization of a drug [26], and type of health insurance plan may also affect persistence to treatment. In fact, more patients in the COACH cohort versus the control cohort received assistance with their prescriptions in our study. To assess this impact, drug utilization and persistence were examined after consideration was taken as to whether assistance or no assistance was received. The data after adjustment continued to show that patients in the COACH cohort did significantly better in terms of average number of refills and days on therapy versus patients in the control group regardless of whether they received assistance.

It should be noted that the data collected were based on the first eligible claim, and patient status regarding type of plan could have changed during the study; moreover, it is possible for a patient to have had commercial insurance and receive assistance such as coupons. Since there was a possibility that overlap of commercial insurance with coupon use might have an impact on outcomes, additional details on how many patients had this overlap were extracted from the database. Out of 1724 patients in the COACH cohort, 579 patients (34%) had commercial insurance; of these, 140 patients (8%) had at least one claim using coupons or copay in the study period. In this group of patients with commercial insurance and using coupons or copay, all but one had a $15 copay card, with this patient having a 0$ copay. We believe that this low incidence would not greatly influence the study findings.

In addition, although most patients in the COACH cohort had used insulin in the 1-year period prior to the welcome call, it is not known if they switched to Gla-300 from another basal insulin, or if they discontinued their insulin therapy and started Gla-300 later on, as well as the reasons behind switching/discontinuation (e.g., suboptimal glycemic control, difficulty maintaining regimen, economic reasons). It is also possible that the patients who enrolled in the program were already highly committed to their treatments, resulting in improved prescription refill and days on therapy. Finally, level of “engagement” (i.e., number of text messages/log-ins to the platform, visualization of webinars, and access to digital tools) and treatment satisfaction could not be determined, and the number of patients enrolled is limited, reflecting common difficulties in recruiting patients to these types of support programs.

Future studies of the impact of the COACH program should evaluate long-term clinical benefits as well as costs and health-care resource utilization, and should determine whether persistence/adherence is sustained once patients disengage or withdraw from the program.

Conclusions

Persistence with basal insulin therapy can vary during the course of treatment, and depends on the engagement of both patients and health-care providers. Patients treated with Gla-300 who received support through the COACH program were more likely to refill their prescriptions and stay on therapy, which may result in significant clinical benefit in the long term. In addition, initiatives such as the COACH program can provide a valuable tool for all health-care professionals involved in the care of patients with diabetes by providing continuing education and support, encouraging patients to take an active role in their treatment, and alleviating resource and time constraints that are often common in clinical practice. Enrollment in programs with a phone-support component may contribute to improved therapy outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants in the study and Louise Traylor and John Stewart of Sanofi US, Inc. for assistance with the adjusted analysis.

Funding

The Toujeo® COACH support program is a patient support program funded by Sanofi US, Inc. The analysis reported here was funded by McKesson Corporation. Publication processing charges were covered by Sanofi US, Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors received writing/editorial support from Patricia Fonseca, Ph.D., of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi US, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

The data in this manuscript have been partially presented as a poster presentation at the 26th Annual Scientific and Clinical Congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE); Austin, TX, USA; May 3–7, 2017; the 2017 American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE); Indianapolis, IN, USA; August 4–7, 2017; the 53rd Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); Lisbon, Portugal; September 11–25, 2017; the 2017 American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) Annual Meeting; Phoenix, AZ, USA; October 7–10, 2017; and the Metabolic and Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS); Orlando, FL, USA; October 11–14, 2017.

Disclosures

J.D. Goldman: member of the speakers bureau for Sanofi US, Inc., and Novo Nordisk, Inc.; consultant for Becton, Dickinson and Company. J. Gill: employee and stockholder of Sanofi US, Inc. T. Horn: employee of Symphony Health, Inc., under agreement with Sanofi US, Inc. T. Reid: member of the speakers bureau and/or consultant for Sanofi US, Inc., Novo Nordisk, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Eli Lilly and Company. J. Strong: member of the advisory board/panel for Ascensia Diabetes Care US, Inc., Sanofi US, Inc., and Novo Nordisk, Inc.; member of the speakers bureau for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Novo Nordisk, Inc., and Sanofi US, Inc.; consultant for the American Diabetes Association, Novo Nordisk, Inc., and Sanofi US, Inc.; authorship support from Novo Nordisk, Inc., and Sanofi US, Inc. W.H. Polonsky: consultant for Sanofi US, Inc., Novo Nordisk, Inc., and Eli Lilly and Company.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This research study used nonidentifiable data obtained by the COACH support program (COACH cohort) and the Symphony Health IDV prescription claims database (control cohort), so informed consent was not required. A release form was obtained in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7028402.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S1–S159. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kesavadev J, Joshi S, Saboo B, et al. Improved short term and long term outcomes of early insulin initiation in type 2 diabetes over 10 years. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(Suppl 3):50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140–149. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91–120. doi: 10.4158/CS-2017-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polonsky William H., Arsenault Joyce, Fisher Lawrence, Kushner Pamela, Miller Eden M., Pearson Teresa L., Tracz Mariusz, Harris Stewart, Hermanns Norbert, Scholz Bernd-M., Pollom Robyn K., Perez-Nieves Magaly, Pollom Roy Daniel, Hadjiyianni Irene. Initiating insulin: How to help people with type 2 diabetes start and continue insulin successfully. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2017;71(8):e12973. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyrot M, Perez-Nieves M, Ivanova J, et al. Correlates of basal insulin persistence among insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes: results from a multinational survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1843–1851. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1341868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanofi US, Inc. Toujeo (package insert). Bridgewater: Sanofi US, Inc.; 2015.

- 8.Riddle MC, Yki-Järvinen H, Bolli GB, et al. One-year sustained glycaemic control and less hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes using basal plus meal-time insulin: the EDITION 1 12-month randomized trial, including 6-month extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:835–842. doi: 10.1111/dom.12472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yki-Järvinen H, Bergenstal RM, Ziemen M, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using oral agents and basal insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 2) Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3235–3243. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freemantle N, Chou E, Frois C, et al. Safety and efficacy of insulin glargine 300 u/mL compared with other basal insulin therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009421. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei W, Jiang J, Lou Y, Ganguli S, Matusik MS. Benchmarking insulin treatment persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes across different U.S. payer segments. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:278–290. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.16227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Nieves M, Kabul S, Desai U, et al. Basal insulin persistence, associated factors, and outcomes after treatment initiation among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:669–680. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1135789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller ED. Basal insulin in primary care. J Fam Pract. 2016;65(Suppl 10):S3–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganguli A, Clewell J, Shillington AC. The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: a targeted systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:711–725. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S101175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanofi US, Inc. Toujeo COACH support program. https://www.toujeo.com/toujeo-savings-and-support. Accessed 24 May 2018.

- 16.Symphony Health, LLC. Integrated Dataverse. http://symphonyhealth.com/product/idv/. Accessed 24 May 2018.

- 17.Kim KB, Kim MT, Lee HB, Nguyen T, Bone LR, Levine D. Community health workers versus nurses as counselors or case managers in a self-help diabetes management program. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1052–1058. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts Sharon A., Sood Ajay. Diabetes nurse case management: Improving glucose control: 10years of quality improvement follow-up data. Applied Nursing Research. 2016;29:202–205. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philis-Tsimikas A, Gallo LC. Implementing community-based diabetes programs: the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute experience. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Gary TL, Batts-Turner M, Yen HC, et al. The effects of a nurse case manager and a community health worker team on diabetic control, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations among urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2009;169:1788–1794. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piette JD, Weinberger M, Kraemer FB, McPhee SJ. Impact of automated calls with nurse follow-up on diabetes treatment outcomes in a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:202–208. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacco WP, Morrison AD, Malone JI. A brief, regular, proactive telephone “coaching” intervention for diabetes: rationale, description, and preliminary results. J Diabetes Complicat. 2004;18:113–118. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(02)00254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacLean LG, White JR, Broughton S, et al. Telephone coaching to improve diabetes self-management for rural residents. Clin Diabetes. 2012;30:13–16. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.30.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Xue H, Huang Y, Huang L, Zhang D. A systematic review of application and effectiveness of mHealth interventions for obesity and diabetes treatment and self-management. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:449–462. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pillay J, Armstrong MJ, Butalia S, et al. Behavioral programs for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:848–860. doi: 10.7326/M15-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daubresse M, Andersen M, Riggs KR, Alexander GC. Effect of prescription drug coupons on statin utilization and expenditures: a retrospective cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37:12–24. doi: 10.1002/phar.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.