Abstract

Multidrug resistance (MDR) poses a major challenge to medicine. A principle cause of MDR is through active efflux by MDR transporters situated in the bacterial membrane. Here we present the crystal structure of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) drug/H+ antiporter MdfA from Escherichia coli in an outward open conformation. Comparison with the inward facing (drug binding) state shows that, in addition to the expected change in relative orientations of the N- and C-terminal lobes of the antiporter, the conformation of TM5 is kinked and twisted. In vitro reconstitution experiments demonstrate the importance of selected residues for transport and molecular dynamics simulations are used to gain insights into antiporter switching. With the availability of structures of alternative conformational states, we anticipate that MdfA will serve as a model system for understanding drug efflux in MFS MDR antiporters.

The multidrug resistance transporter mediated efflux of antibiotics from the bacterial cytoplasm represents a major challenge to medicine. Here authors solve the X-ray crystallographic structure of the drug/H+ antiporter MdfA from Escherichia coli and shed light on the conformational switching mechanism.

Introduction

Efflux transport of antibiotics and other potentially harmful compounds from the bacterial cytoplasm by multidrug resistance (MDR) transporters represents an increasing challenge for the treatment of pathogenic bacterial infection1–3. A large number of MDR transporters belong to the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS), found in both Gram-positive and -negative organisms1,2. Typical MFS transporters possess 12 transmembrane helices (TMs) divided into two pseudo-symmetrical 6TM N- and C-terminal lobes. Changes in relative orientation of the two lobes within the plane of the bilayer (the rocker-switch mechanism4) allow alternating access to the cytoplasmic and extracellular/periplasmic sides of the membrane, facilitating directed transport of substrates across the membrane, with the transporter cycling between outward open (Oo), inward open (Io) and intermediary occluded states5–7. Despite progress in structural determinations of these states for uniporter and symporter MFS transporters, few such data are available for antiporters.

MdfA, an MFS-MDR transporter from E. coli with homologs in many pathogenic bacteria, is an extensively characterized drug/H+ antiporter8. It transports lipophilic, cationic, and neutral substrates, in each case driven by the proton motive force9,10. Two acidic residues within TM1, Glu26TM1 and Asp34TM1, have been implicated in proton (H+) and substrate transport coupling11–13, and it has been proposed that changes in their protonation could lead to local structural changes within the binding pocket upon H+/substrate binding11. The recently reported structure of chloramphenicol-bound MdfA in an inward facing (If) conformation14 reveals the antibiotic bound in the immediate vicinity of Asp34TM1, in line with earlier biochemical data12,13.

In order to gain a complete picture of the efflux mechanism, however, structural data for alternative states are required. Here we report the crystal structure of MdfA in the Oo state and identify conformational changes that accompany transitions between the If and Oo states. With the availability of structures of alternative conformational states, we anticipate that MdfA will serve as a model system for understanding drug efflux in MFS MDR antiporters.

Results

Overall structure of MdfA in the outward open (Oo) state

The crystal structure of Fab-bound MdfA presented here reveals the transporter in the outward open (Oo) state, with the N- and C-lobes approaching each other closely at the intracellular face of the transporter (Fig. 1). The N-terminus of TM5 juxtaposes the C-termini of TM8 and TM10 and the N-terminus of TM11 nestles between the C-termini of TM2 and TM4. Access to the transporter cavity from the cytoplasmic face is sealed off by formation of a hydrophobic plug through intercalation of sidechains from each of these helices centered around Phe340TM10 (Fig. 2). These contacts are supported by mutually favorable interactions between the side chain of Arg336TM10 and the C-terminal dipole of TM4, and Asp77TM2 and the N-terminal dipole of TM11. Asp77TM2 (from conserved motif A) is in addition part of an electrostatic cluster involving Arg81TM3 and Glu132TM5, with an adjacent cluster including Arg78TM2 and residues of the intermediate loop (Arg198α6–7) and helix (Asp211α6–7).

Fig. 1.

Overall structure of MdfA in the outward open (Oo) and inward facing (If) states. a The transporter in the Oo conformation (this work); b MdfA in the ligand-bound If state (ref. 14). The N- (white/gray) and C-terminal (yellow) six transmembrane helical domains are shown in ribbon representation, with transmembrane helices (TMs) numbered. Note the difference in relative orientation of the two domains by 33.5°. TM5, whose conformation differs between the two states, is shown in green (Oo) or orange (If); the TM1–TM2 termini are in corresponding light colors. The position of chloramphenicol bound in the If state is depicted using blue sticks

Fig. 2.

Cytoplasmic and periplasmic faces of MdfA in the outward open conformation. a The cytoplasmic entrance to the ligand-binding pocket is closed in the Oo conformation by numerous interactions between the N- and C-lobes (view obtained by rotating Fig. 1 90° about a horizontal x-axis). The N-terminus of TM5 juxtaposes the C-termini of TM8 and TM10, and the N-terminus of TM11 nestles between the C-termini of TM2 and TM4. Hydrophobic sidechains from each of these helices pack against each other to form a hydrophobic plug that seals off access to the transporter cavity from the cytoplasmic face, supported by additional mutually favorable electrostatic interactions. b View from the periplasmic face (following a 180° rotation about a horizontal x-axis), demonstrating the deep cavity between the two domains in the outward open conformation. Dotted line denotes approximate boundary delineated by the bacterial membrane outer leaflet head groups

In the ligand bound If state, in which the two lobes rotate largely as rigid bodies by 33.5° about an axis parallel to the plane of the membrane bilayer, these multiple interactions are replaced by predominantly hydrophobic contacts between the periplasmic halves of TMs 1, 2, and 5 of the N-terminal domain and TMs 7, 8, and 11 of the C-terminal domain. This is effected by a sliding of TM11 along TM2 and a significant rearrangement of TM5 (see below), closing the transporter cavity to the periplasm. The drug binding pocket observed in the If state is disrupted in the Oo state through displacement of Ala150TM5 and Leu151TM5 (see below) as well as lateral movement of C-terminal domain residues from TMs 7 and 8 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

MdfA helix TM5 is kinked and twisted in the Oo state

Superposition of the individual domains of MdfA in the If and Oo conformations reveals significant deviations in the N-terminal domain (Supplementary Fig. 2). The largest of these are found in TM5, which ends in the antiporter motif C 153AlaProXaaXaaGlyPro158 that is absent in symporters and uniporters15. Whereas TM5 in the If structure adopts an α-helical conformation of almost ideal geometry up to motif C, residues 136 to 153 in the Oo structure exhibit a profound 15° kink, accompanied by a ca. 45° clockwise twist parallel to the helix axis that terminates with the two-proline-containing motif C (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Movie). This results in a repositioning of the hydrophobic side chains Ile142TM5, Leu145TM5, Met146TM5, and Val149TM5 with respect to the N-terminal domain core. Leu145TM5, which in the If conformation associates with the N-terminal domain, engages instead with residues of the C-terminal domain in the Oo state. The carboxamide of conserved Asn148TM5 is removed from a (presumably hydrophobic) membrane exposed location in the If state to form hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Asn272TM8 and the main chain carbonyl of Ile269TM8 in the Oo conformation. The largest deviation in TM5 is found at residue Met146TM5, the side chain of which rests against the aromatic moiety of Tyr127TM4 in the present structure. In turn, the side chain hydroxyl of Tyr127TM4 is found within hydrogen bonding distance (2.5 Å) of the carboxylate of Glu26TM1 in the Oo structure. Crucially, the space occupied by the Tyr127TM4 side chain in the Oo state is in the If structure replaced by that of Met146TM5.

Fig. 3.

The Oo and If conformations differ by local twisting of TM5. a In the Oo state, TM5 (green) in the N-terminal domain is partially distorted, resulting in Cα displacements compared to the If state of up to 2.9 Å (Met146TM5). The side chain of Met146TM5 rests against the phenolic side chain of Tyr127TM4, whose hydroxyl moiety is ca. 2.5 Å from the side chain carboxylate group of Glu26TM1. b TM5 adopts an almost ideal α-helical conformation in the If state through displacement of the Tyr127TM4 side chain by that of Met146TM5. TM5 straightens, rotating around its axis such that its hydrophobic side chains can engage/disengage the C-terminal domain. c Electron density for TM5 in the Oo conformation, superimposed with coordinates of the final (green) and initial (orange) models. See also Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Movie

Rearrangements in the N-terminal domain hydrophobic core

Also of note are small yet significant changes in the region Leu41TM1–Val54TM2, which runs from the C-terminus of TM1 and the N-terminus of TM2 (Supplementary Fig. 4). The side chains of residues Val43TM1, Tyr47TM1, and Trp53TM2 form part of a hydrophobic cluster near the periplasmic face of MdfA that includes Met40TM1, Ile105TM4, and Phe108TM4 from TM4, and Trp170TM6 and Phe174TM6 at the N-terminus of TM6. This cluster, which juxtaposes the buried guanidinium moiety of Arg112TM4 that is absolutely conserved among MFS homologs (motif B), exhibits a small but significant expansion in the present structure compared to that in the If conformation. While the structural differences may appear to be small, we note that the transporter MdfA is stabilized by ligand binding14,16, so that the transporter in the unbound Io state could well differ from the ligand bound MdfA If structures presented by Heng et al.14,17.

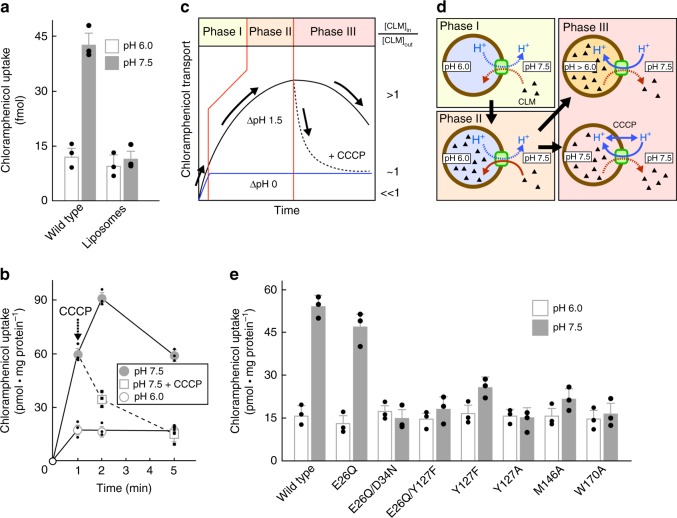

In order to test the effect of amino acid substitutions on chloramphenicol transport experimentally, MdfA and its variants were reconstituted in proteoliposomes following procedures described for the chloroquine resistance transporter from Plasmodium falciparum18 (Fig. 4). Purified reconstituted wild-type MdfA was able to transport 50 pmol chloramphenicol (per mg protein per minute), which compares favorably with the 3 pmol mg−1 min−1 determined using crude membrane preparations19, whereas transport proved unaffected by mutation of Glu26TM1 to Gln, suggesting that the charge state of this residue is not crucial for chloramphenicol transport. The variants Tyr127TM4Phe, Met146TM5Ala, and Trp170TM6Ala of the hydrophobic core all showed significant reductions in transport in the presence of a pH gradient. As expected, chloramphenicol transport was low in the absence of ΔpH, arising from downhill transport due to the initial infinite substrate gradient.

Fig. 4.

Chloramphenicol transport by MdfA reconstituted in proteoliposomes. a Chloramphenicol transport into reconstituted proteoliposomes is dependent upon the presence of MdfA and a pH gradient. b Time course for uptake using reconstituted MdfA. In the absence of a pH gradient (open circles), downhill-like transport (with the substrate gradient) occurs rapidly due to the small volume of the proteoliposomes. In the presence of a pH gradient, however, chloramphenicol uptake (filled circles) involves at least three phases: following a rapid initial downhill transport phase (not visible), uphill accumulation of the substrate in the liposomal lumen against the concentration gradient takes place at the expense of proton export (II). Within a few minutes, the situation is reversed due to lumen acidification, leading to chloramphenicol efflux (phase III). Crucially, collapse of the pH gradient through administration of the H+-ionophore CCCP (open squares) results in rapid chloramphenicol efflux (downhill transport) until the luminal concentration reaches that observed in the absence of a pH gradient. c, d Schematic diagram illustrating the phases of chloramphenicol (CLM) uptake in the reconstituted system. e Uptake by proteoliposomes containing purified MdfA variants in the presence (closed bars) and absence (open bars) of a pH gradient at 1 min. Data are mean values ± s.d., n = 3

Molecular dynamics simulations

To gain further insights into the transport cycle, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed with all possible combinations of Glu26TM1 and Asp34TM1 protonation states, starting from either the Oo structure without Fab or the If structure without chloramphenicol. Initial trials with the present structure assuming both acidic residues to be deprotonated [Oo(E26−/D34−)] indicated that the overall structure remained unchanged during the MD simulation. The C-terminal lobe is more rigid than the N-terminal lobe, and the cytoplasmic halves of the TM helices (relative to the center of the lipid bilayer) showed smaller root mean square deviation (RMSD) values than those of the periplasmic halves of the TM helices (Supplementary Table 1)—despite the fact that the Fab binds to the cytoplasmic face of MdfA. We therefore conclude that the outward-open conformation of MdfA is little affected by Fab binding (corroborated by low-resolution data from crystals of MdfA alone20) and is stably maintained in a solvated membrane environment.

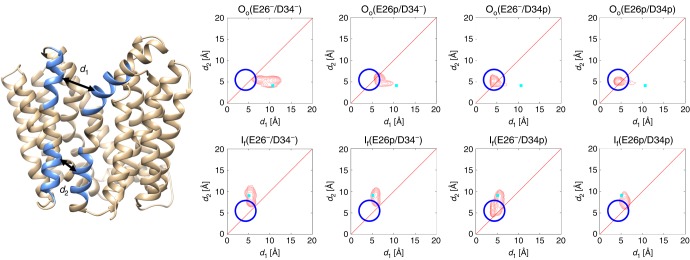

To monitor the degree of conformational change, two distances were used to describe the opening and closing of the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides of the transporter (d1 and d2 respectively) (Fig. 5). Starting from the Oo state, the largest divergence from the crystal structure was observed when Asp34TM1 was protonated [Oo(E26−/D34p) and Oo(E26p/D34p)], resulting in small values of d1 and d2. This state corresponds to an occluded conformation, as both the periplasmic and cytoplasmic entrances are closed. Analysis of the free energy landscape for this transition (Supplementary Fig. 5a) indicates that upon protonation of Asp34TM1, the Oo state is much less stable than the occluded state, suggesting that the transition occurs rapidly and is in effect irreversible. During the simulations, the hydrogen bond between Glu26TM1 and Tyr127TM4 was for the most part maintained, although the carboxylate at times also hydrogen bonded to Tyr30TM1 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Conformational distributions of MdfA obtained following MD simulations. Starting from each initial conformation (Oo vs. If) and Glu26/Asp34 protonation state, the conformational distributions of the MD simulations were calculated as a function of d1 and d2 (d1: minimum distance between Cα atoms of residues 156–165 (TM5) and those of residues 253–262 (TM8); d2: minimum distance between Cα atoms of residues 139–148 (TM5) and those of residues 270–279 (TM8)). Cyan squares indicate the corresponding distances in the initial conformations (Oo: this study; If PDB 4ZOW), and the blue circles indicate the position of the peak in the plot for Oo(E26−/D34p)

In the occluded state adopted following Asp34TM5 protonation, the acidic side chain juxtaposes an internal cavity bounded by the conserved residues Tyr257TM8, Gln261TM8 as well as the hydrophobic side chains of Ile239TM7 and Phe265TM8; this cavity is also observed in the If crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 7). TM5 is straighter than in the Oo and If structures, although it adopts a twisted conformation as in the Oo structure.

Starting from the If crystal structure after removal of the ligand and replacement of Arg131TM4 by the wild-type Gln, a similar occluded state was obtained during the MD run If(E26−/D34p). In contrast to the transition from the Oo state, however, the If and the occluded states are in a flat free-energy well (Supplementary Fig. 5b), suggesting that these two states can co-exist when Asp34TM5 is protonated and that the transition between the If state and the occluded state is reversible. As we observed only a one-way transition from the If state to the occluded state in the 1 μs MD simulation, the transition must be slow, presumably due to the complex and rugged nature of the original multi-dimensional energy surface. During this simulation, TM5 twisting was observed due to the close approach of the cytoplasmic halves of TM5 and TM8 (i.e. decreasing d2), following accommodation of Leu151TM5 in the space between Leu268TM8 and Ile269TM8 (Supplementary Fig. 7). During the simulations where Glu26TM1 was protonated [If(E26p/D34−) and If(E26p/D34p)], Tyr127TM4 moved toward Glu26TM1 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Discussion

The structure of MdfA presented here reveals features of the Oo conformation and allows comparison with the previously determined ligand bound If state14. Going from the If to the Oo state, the N- and C-terminal domains of the transporter reorient in the membrane largely as rigid bodies, with the exception of three regions: (i) transmembrane helix TM5 kinks and twists, (ii) the periplasm-proximal hydrophobic core of the N-terminal domain reorganizes, and (iii) a cytoplasmic loop of the C-terminal domain rearranges to accommodate closure of the cytoplasmic entrance (see Supplementary Movie). The twisting of the helix in the Oo conformation appears to be prevented from transiting to a straight-form as seen in the If state by juxtaposition of the Tyr127TM4 and Met146TM5 side chains, with the aromatic side chain hydroxyl of Tyr127TM4 held in place by a hydrogen bond to Glu26TM1. Our reconstitution experiments demonstrate the importance of Tyr127TM4 and Met146TM5 for transport, and suggest that the charge state of Glu26TM1 is of little significance for chloramphenicol transport in the presence of a pH gradient, which is consistent with previous results19. It should be noted that, strictly speaking, the conclusions presented here apply only to chloramphenicol transport (for which structural data of the If form are available); whereas we expect them to be generally valid for other neutral MdfA substrates, the situation may differ for other substrates.

To gain further insights into the transport process, we performed MD simulations involving different protonation states of the two acidic residues identified previously as being important in in vivo studies11,16,21, Asp34TM1 and Glu26TM1. Within the timescale of our simulations, protonation of Asp34TM1 through exposure to the low pH periplasmic space leads to an occluded state in which the acidic side chain becomes enclosed in an internal cavity that recapitulates its environment in the If conformation. TM5 continues to be twisted in this occluded state and the Glu26TM1–Tyr127TM4 hydrogen bond remains intact, although the charge state of Glu26TM1 does not appear to play a role in this. Nevertheless, previous in vivo studies have shown that Glu26TM1 is critical for the transport of cationic substrates11,16, so that the situation may be different for cationic and lipophilic substrates, in which the initial If state assumed here might not apply.

MD simulations also demonstrate that an occluded state and a twisted TM5 conformation can be obtained starting from the If state. The fact that the transporter is stabilized by ligand binding14,16 however means that the If structures presented by Heng et al.14,17 might not provide an accurate representation of MdfA in the unbound Io state (moreover, these ligand-bound structures were obtained using a mutated variant Gln131TM4Arg, which has recently been reported to be transport inactive22,23). Thus TM5 untwisting might occur on going from the occluded to the Io state, or upon ligand binding to form the If state.

Recent structure determinations of other transporters5–7 indicate that individual helices within each domain can exhibit significant variability upon conformation switching. For MdfA, the existence of structurally underdetermined Io and intermediate occluded states (whereby ligand bound and unbound occluded states are likely to be different) thus precludes a detailed description of the complete transport cycle. Nevertheless, the combination of data presented here suggests an important role for the interaction between Glu26TM1 and Tyr127TM4. We note that through their common location on helix TM4, the orientation of the Tyr127TM4 side chain could couple with the environment of the motif B Arg112TM4 side chain. The buried guanidinium moiety is involved in an elaborate hydrogen bonding network involving the even more buried Gln115TM4, the carbonyl carbon of Gly32TM1, and (via a solvent molecule identified in the high-resolution structure14) Asn33TM1 and Asp34TM1. Residues Arg112TM4, Asp34TM1, Gln115TM4, and Gly32TM1 have all been shown to be important for MdfA action11,14,16,19,24, and a role of the surrounding hydrophobic cluster is confirmed by the deleterious effect on chloramphenicol transport of the Trp170TM6Ala mutation. Changes in the chemical environment of Asp34TM1 (e.g. by ligand binding or changes in protonation) could therefore lead to the observed reorganization of the hydrophobic cluster immediately adjacent to Arg112TM4. In turn, communication of this change through TM4 could influence the orientation of the Tyr127TM4 side chain, dictating the position of that of Met146TM5 and thereby the degree of TM5 twist. Releasing the twist of TM5 from the Oo to the If conformation would result in a repositioning of the hydrophobic side chains Ile142TM5, Leu145TM5, Met146TM5, and Val149TM5 with respect to the N-terminal domain core, allowing Leu145TM5 to dissociate from the N-terminal domain to engage the C-terminal domain.

Support is provided by MdfA rescue mutants. Selection for drug transport rescue in cells harboring the otherwise inactive TM1 variants Glu26TM1Thr/Asp34TM1Met and Glu26TM1Thr resulted in the detection of mutants containing the acidic side chains Ala150TM5Glu and Val335TM10Glu11,25. These residues would be well positioned to make hydrogen bonds to Tyr127TM4 in the outward open structure (Supplementary Fig. 8). Recent thermodynamic calculations and molecular dynamic simulations have led in principle to similar conclusions for the L-fucose/H+ symporter FucP26. Using computational methods, it was proposed that protonation of FucP Glu135TM4 in TM4 allows surmounting of a ca. 2 kcal mol−1 energy barrier between the inward and outward open states. An intermediate state in which TM11 is distorted is postulated, although a causative link between Glu135TM4 (de)protonation and TM11 distortion has not been described. Inspection of the FucP structure27 suggests that Glu135TM4 could form a hydrogen bond with Tyr365TM10 of C-terminal domain TM10 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Interestingly, C-terminal domain TM11 is the counterpart of TM5 in the (inverted topology) N-terminal domain28, reflecting the pseudosymmetry of the two domains, so that the antiporter MdfA and symporter FucP might be thought of as examples of repeat swapping to yield similar transport mechanisms.

The presence of the MFS-antiporter motif C would appear to be central to transporter switching—restricting the twist of TM5 to a small localized helical segment to facilitate relative rotation of the two domains, and transmitting these perturbations to an adjacent pliable hydrophobic cluster. As other structurally well-characterized antiporter families (such as the amino acid/polyamine/organocation (APC) transporter superfamily29 and cation/H+ antiporter family30) have been shown to utilize other mechanisms, this may be a property specific to MFS-antiporters. The Oo structure presented here could serve as a template for the design of novel MFS inhibitors that are able to access their target directly from the bacterial exterior.

Methods

Crystal structure solution

Isolation of Fab fragments that recognize native conformations of MdfA in proteoliposomes has been described elsewhere31. Co-crystals of MdfA in complex with Fab fragments grew in the lipidic cubic phase and diffracted to 3.4 Å resolution20,31. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K at a wavelength of 1.0 Å on the SLS beamline PXI (X06SA) using the 16M Eiger detector. In order to resolve the very long c-axis (929 Å), the crystal was mounted so that the rotation axis was ca. 30° to the crystallographic c-axis. The synchrotron beam (with beam size increased from 10 to 100 µm) was defocused from the crystal to the detector. Data sets (180° in 0.1° steps) were processed using the program XDS32. The crystal belongs to the space group P6122 with one complex in the asymmetric unit. Phases were determined by molecular replacement with PHASER MR33 using the separated N- and C-lobes of MdfA in the inward open conformation (PDBID: 4ZP0)14 and an Fab fragment (PDBID:1IBG)34 as individual search models. The replacement model was rebuilt manually using COOT35 and refined using PHENIX36 with TLS refinement (three groups per polypeptide chain) to an Rfree value of 28.3%. The final model consists of MdfA residues Gln14–Lys400, Fab heavy chain residues Leu4–Pro216, and Fab light chain residues Asp1–Arg211, as well as one sulfate ion. Ramachandran analysis demonstrates that 94.4% of the residues are in the favorable regions and 5.5% in the allowed regions. One residue (Ser65 in the Fab fragment heavy chain) was in the outlier regions. Atoms for difference density corresponding to solvent molecules, lipids, and/or detergents were not added to the model in accordance with the low resolution of the data. The Fab binds to the cytoplasmic side of MdfA, where it may stabilize the outward open state and enhances crystal contacts20. Data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table 1. RMSDs in Cα in positions between Oo and If states (Supplementary Fig. 2) were calculated as a function of residue number after separate superposition of the N- and C-terminal domains using the programme LSQKAB from the CCP4 suite37. The kink of α-helix TM5 was calculated using Kink Finder38. Figures and movies were prepared using PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| MdfA–Fab YN1074 | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P6122 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 73.26, 73.26, 927.92 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 90.00, 120.00 |

| Resolution (Å) | 49–3.4 (3.61–3.4)a |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 25.4 (166.9) |

| I /σI | 11.57 (1.59) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.9) |

| Redundancy | 17.3 (16.03) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 49–3.4 |

| No. of reflections | 22216 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 25.8/28.3 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 6,134 |

| Ion | 5 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 113.3 |

| Ion | 136.8 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.596 |

aValues in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell

Reconstitution of MdfA

MdfA mutants were generated using a PCR site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) with the primers listed in the Supplementary Table 2, and purified as for wild-type MdfA. Forty micrograms of purified wild type or mutant MdfA was mixed with 500 μg of azolectin liposomes (Sigma type IIS), frozen at 193 K for at least 10 min18. The mixture was thawed quickly by holding the sample tube in the hand and diluted 60-fold with reconstitution buffer containing 20 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 0.1 M sodium chloride, 5 mM magnesium chloride. Reconstituted proteoliposomes were pelleted by centrifugation at 200,000 × g at 277 K for 1 h, and suspended in 0.2 mL of same buffer.

Transport assay

The transport assay mixture (0.2 mL) containing 20 mM MOPS-Tris (pH 7.5) or 20 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 0.1 M sodium chloride, 5 mM magnesium chloride, and 2 μM [ring-3,5 3H] chloramphenicol (0.5 MBq μmol−1, PerkinElmer) was incubated at 300 K for 3 min. Proteoliposomes containing MdfA (0.5 μg protein per assay) (or liposomes as control) were added to the mixture to initiate transport, and incubated for a further 1 min. Aliquots (130 μL) were taken and centrifuged through a Sephadex G-50 (fine) spin column at 760 × g for 2 min. Radioactivity in the eluate was counted using a liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). As a control, the ionophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) was added to the assay (final concentration 1 μM) after 1 min to collapse the pH gradient. Bovine serum albumin was used as a protein concentration standard39.

MD simulations

Initial coordinates of MdfA in the Oo conformation were taken from those of the crystal structure of the MdfA–Fab complex. N- and C-terminal MdfA residues were capped with acetyl and N-methyl groups, respectively. All histidine residues were protonated on the Nδ1 atom. All acidic residues (excluding Glu26TM5 and Asp34TM5) and all basic residues were deprotonated and protonated, respectively (see Supplementary Table 3). Glu26TM5 was protonated in the initial structure of the Oo(E26p/D34−) and Oo(E26p/D34p) simulation runs and Asp34TM5 was protonated for the Oo(E26−/D34p) and Oo(E26p/D34p) simulation runs. After filling the large cavity on the periplasmic side of the protein with water molecules to prevent placement of lipid molecules there, the structure was embedded in a lipid bilayer and solvated with water and ions using CHARMM-GUI40. The orientation of MdfA relative to the lipid bilayer was determined analogously to that of MdfA in the If state (PDB ID: 4ZP0) as deposited in the Orientations of Proteins in Membranes (OPM) database41 by alignment of the Cα atoms of residues 203–400. The rectangular simulation system generated by CHARMM-GUI (90.76 Å × 90.76 Å × 96.98 Å) was subjected to periodic boundary conditions. The system was composed of one protein, 223 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE), 40 or 41 K+, 44 or 45 Cl–, and about 14,000 water molecules. The CHARMM36 force-field parameters42,43 were used for protein, lipid, and ions, and the TIP3P model44 was used for water. Initial coordinates for the simulations starting from the If conformation were generated in a similar manner. Here, the coordinates of the chloramphenicol-bound, If form of MdfA (PDB ID: 4ZOW) was used after the ligand coordinates were removed and Arg131 was replaced with the wild-type Gln residue. The system size was 92.01 Å × 92.01 Å × 98.11 Å and was composed of 233 POPE, 41 or 42 K+, 47 or 48 Cl−, and about 14,700 water molecules.

After energy minimization and equilibration, a production MD run was performed for 1.6 μs (starting from the Oo conformation) or 1.0 μs (starting from the If conformation). During the simulation, the temperature was kept at 303.15 K using the Nosé–Hoover thermostat45,46, and the pressure was kept at 1.0 × 105 Pa using the semi-isotropic Parrilello-Rahman barostat47,48. Bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the LINCS algorithm49,50 to allow the use of a large time step (2 fs). Electrostatic interactions were calculated with the particle mesh Ewald method51,52. All MD simulations were performed with Gromacs 5.0.5 (ref. 53), with coordinates recorded every 10 ps.

Time evolutions of RMSDs in the Oo(E26–/D34p) and If(E26–/D34p) MD runs were calculated using their respective initial and final structures as reference (Supplementary Fig. 9). The average values of the RMSDs from the final structures of the Oo(E26–/D34p) and If(E26–/D34p) runs calculated for the last 2.7μs trajectory of the Oo(E26–/D34p) MD run were 1.24 ± 0.14 and 1.21 ± 0.08 Å, respectively. Corresponding values calculated for the last 0.5μs trajectory of the If(E26–/D34p) MD run were 1.48 ± 0.16 and 1.23 ± 0.26 Å, respectively. Thus the two simulations converged to similar states.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Vincent Oleric and Takashi Tomizaki of the Swiss Light Source (SLS, Villingen) for assistance in data collection and Toshiya Senda for helpful discussions and support. This work was supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) program ZIK HALOmem (FKZ 03Z2HN21 to M.T.), by the European Regional Development Fund ERDF (1241090001 to M.T.S.), and in part by the Platform Project for Supporting in Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics and Structural Life Science (PDIS) and Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant number JP18am0101107 (to T.T.), JP18am0101079 (to S.I. and N.N), and JP18am0101071 (to M.T), the ERATO Human Receptor Crystallography Project of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) (to S.I.), by the Strategic Basic Research Program, JST (to S.I. and N.N), by the Targeted Proteins Research Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (to S.I.), and by Grants-in-Aids for Scientific Research from the MEXT (No. 22570114 to N.N.). Crystallographic data were collected at the SLS with support from the European Community’s 7th Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under BioStruct-X (grant agreement No. 283570, project ID: BioStructx_5450 to M.T.).

Author contributions

K.N., F.J. and M.T. purified and crystallized MdfA and collected diffraction data. Fab YN1074 was produced by Y.N.-N., K.L., Y.H. and N.N. using the antibody production platform for membrane proteins developed by S.I. and N.N. The structure was solved by K.N. and C.P. and analyzed together with M.T.S. and M.T. Reconstitution experiments were performed by N.J., T.M., H.O. and M.T. MD simulations were carried out by T.T. The project was conceived and designed by M.T. and supervised together with M.T.S. All authors participated in analysis and discussion of the results and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Coordinates of the MdfA–Fab complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 6GV1 (10.2210/pdb6GV1/pdb).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Milton T. Stubbs, Email: stubbs@biochemtech.uni-halle.de

Mikio Tanabe, Email: mikio.tanabe@kek.jp.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06306-x.

References

- 1.Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier MH. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Putman M, van Veen HW, Konings WN. Molecular properties of bacterial multidrug transporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:672–693. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.672-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikaido H. Multidrug resistance in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:119–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082907.145923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramson J, et al. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science. 2003;301:610–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1088196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaback HR. A chemiosmotic mechanism of symport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:1259–1264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419325112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang X, et al. Crystal structure of a LacY-nanobody complex in a periplasmic-open conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:12420–12425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615414113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quistgaard EM, Löw C, Guettou F, Nordlund P. Understanding transport by the major facilitator superfamily (MFS): structures pave the way. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:123–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bibi E, Adler J, Lewinson O, Edgar R. MdfA, an interesting model protein for studying multidrug transport. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;3:171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edgar R, Bibi E. MdfA, an Escherichia coli multidrug resistance protein with an extraordinarily broad spectrum of drug recognition. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:2274–2280. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2274-2280.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewinson O, et al. The Escherichia coli multidrug transporter MdfA catalyzes both electrogenic and electroneutral transport reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1667–1672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0435544100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sigal N, Fluman N, Siemion S, Bibi E. The secondary multidrug/proton antiporter MdfA tolerates displacements of an essential negatively charged side chain. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6966–6971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808877200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fluman N, Cohen-Karni D, Weiss T, Bibi E. A promiscuous conformational switch in the secondary multidrug transporter MdfA. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:32296–32304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fluman N, Ryan CM, Whitelegge JP, Bibi E. Dissection of mechanistic principles of a secondary multidrug efflux protein. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:777–787. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heng J, et al. Substrate-bound structure of the E. coli multidrug resistance transporter MdfA. Cell Res. 2015;25:1060–1073. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varela MF, Sansom CE, Griffith JK. Mutational analysis and molecular modelling of an amino acid sequence motif conserved in antiporters but not symporters in a transporter superfamily. Mol. Membr. Biol. 1995;12:313–319. doi: 10.3109/09687689509072433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adler J, Bibi E. Determinants of substrate recognition by the Escherichia coli multidrug transporter MdfA identified on both sides of the membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8957–8965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu M, Heng J, Gao Y, Wang X. Crystal structures of MdfA complexed with acetylcholine and inhibitor reserpine. Biophys. Rep. 2016;2:78–85. doi: 10.1007/s41048-016-0028-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juge N, et al. Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter is a H+-coupled polyspecific nutrient and drug exporter. Proc. . Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3356–3361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417102112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler J, Lewinson O, Bibi E. Role of a conserved membrane-embedded acidic residue in the multidrug transporter MdfA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:518–525. doi: 10.1021/bi035485t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagarathinam K, et al. The multidrug-resistance transporter MdfA from Escherichia coli: crystallization and X-ray diffraction analysis. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2017;73:423–430. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X17008500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigal N, Molshanski-Mor S, Bibi E. No single irreplaceable acidic residues in the Escherichia coli secondary multidrug transporter MdfA. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:5635–5639. doi: 10.1128/JB.00422-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yardeni, E. H., Zomot, E. & Bibi, E. The fascinating but mysterious mechanistic aspects of multidrug transport by MdfA from Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.09.004 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Zomot E, et al. A new critical conformational determinant of multidrug efflux by an MFS transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 2018;430:1368–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigal N, et al. 3D model of the Escherichia coli multidrug transporter MdfA reveals an essential membrane-embedded positive charge. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14870–14880. doi: 10.1021/bi051574p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler J, Bibi E. Promiscuity in the geometry of electrostatic interactions between the Escherichia coli multidrug resistance transporter MdfA and cationic substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2721–2729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Ke M, Gong H. Protonation of Glu135 facilitates the outward-to-inward structural transition of fucose transporter. Biophys. J. 2015;109:542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dang S, et al. Structure of a fucose transporter in an outward-open conformation. Nature. 2010;467:734–738. doi: 10.1038/nature09406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radestock S, Forrest LR. The alternating-access mechanism of MFS transporters arises from inverted-topology repeats. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;407:698–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krammer EM, Ghaddar K, André B, Prévost M. Unveiling the mechanism of arginine transport through AdiC with molecular dynamics simulations: the guiding role of aromatic residues. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0160219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drew D, Boudker O. Shared molecular mechanisms of membrane transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016;85:543–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaenecke F, et al. Generation of conformation-specific antibody fragments for crystallization of the multidrug resistance transporter MdfA. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1700:97–109. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7454-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabsch Wnbsp. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeffrey PD, et al. Structure and specificity of the anti-digoxin antibody 40-50. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;248:344–360. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilman HR, Shi J, Deane CM. Helix kinks are equally prevalent in soluble and membrane proteins. Proteins. 2014;82:1960–1970. doi: 10.1002/prot.24550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaffner W, Weissmann C. A rapid, sensitive, and specific method for the determination of protein in dilute solution. Anal. Biochem. 1973;56:502–514. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J, et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM simulations using the CHARMM36 additive force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:405–413. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lomize MA, Lomize AL, Pogozheva ID, Mosberg HI. OPM: orientations of proteins in membranes database. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:623–625. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klauda JB, et al. Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Best RB, et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–11. doi: 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nosé S. A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 2006;52:255–268. doi: 10.1080/00268978400101201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoover WG. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A. 1985;31:1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parrinello M, Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. doi: 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nosé S, Klein ML. Constant pressure molecular dynamics for molecular systems. Mol. Phys. 2006;50:1055–1076. doi: 10.1080/00268978300102851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hess B. P-LINCS: a parallel linear constraint solver for molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:116–122. doi: 10.1021/ct700200b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen H. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199709)18:12<1463::AID-JCC4>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Essmann U, et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. doi: 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Coordinates of the MdfA–Fab complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 6GV1 (10.2210/pdb6GV1/pdb).