Abstract

Pathogens have developed particular strategies to infect and invade their hosts. Amongst these strategies’ figures the modulation of several components of the innate immune system participating in early host defenses, such as the coagulation and complement cascades, as well as the fibrinolytic system. The components of the coagulation cascade and the fibrinolytic system have been proposed to be interfered during host invasion and tissue migration of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and more recently, helminths. One of the components that has been proposed to facilitate pathogen migration is plasminogen (Plg), a protein found in the host’s plasma, which is activated into plasmin (Plm), a serine protease that degrades fibrin networks and promotes degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM), aiding maintenance of homeostasis. However, pathogens possess Plg-binding proteins that can activate it, therefore taking advantage of the fibrin degradation to facilitate establishment in their hosts. Emergence of Plg-binding proteins appears to have occurred in diverse infectious agents along evolutionary history of host–pathogen relationships. The goal of the present review is to list, summarize, and analyze different examples of Plg-binding proteins used by infectious agents to invade and establish in their hosts. Emphasis was placed on mechanisms used by helminth parasites, particularly taeniid cestodes, where enolase has been identified as a major Plg-binding and activating protein. A new picture is starting to arise about how this glycolytic enzyme could acquire an entirely new role as modulator of the innate immune system in the context of the host–parasite relationship.

Keywords: enolase, fibrinolytic system, host/parasite relationship, immune evasion, Plasminogen

Introduction

Infectious agents migrate to their predilection sites in the host tissues, sometimes requiring to trespass physical barriers of the host such as epithelia, extracellular matrices (ECM), basement membranes, or circumvent several effector systems along their journey through the bloodstream [1–3]. They evade innate and adaptive host’s immune responses, involving the participation of multiple proteins, including proteolytic enzymes, receptors, immunomodulatory molecules, amongst many other factors that facilitate their dissemination and establishment in host’s tissues [4–8]. Infectious agents can uptake and use host proteins for their benefit [9–11]. In particular, it has been proposed that they can take advantage of the host’s coagulation cascade through the activation of plasminogen (Plg) to be converted into an active proteolytic enzyme (plasmin (Plm)). Plm participates indirectly in the degradation of ECM proteins and cell-junction proteins, thus facilitating invasion and establishment [12,13].

The goal of the present review is to list, summarize, and analyze different examples of Plg-binding proteins used by infectious agents to invade and establish in its host. These appear to be adaptive mechanisms of those infectious agents taking advantage of host’s proteins. To facilitate the analysis, the review was divided in bacterial and fungal infectious agents and protozoal and helminth parasites. A short section also considers tumor cells as invasive agents. Special emphasis was given to the mechanisms that helminth parasites, particularly cestodes, use to migrate and establish into predilection tissues in the host. Understanding these mechanisms might result in strategies for the prevention and control of infectious pathogens.

Coagulation, complement, and fibrinolysis

The coagulation cascade and the fibrinolytic system

The coagulation cascade is a complex sequence of proteolytic reactions that ends with the formation of the fibrin clot. The coagulation cascade involving cellular (platelets) and proteolytic factors is activated when the endothelium of a blood vessel is damaged. The immediate goal is to stop bleeding, facilitating and promoting other mechanisms for damage control and repair. The coagulation cascade proceeds in two pathways: the intrinsic, formed by factors VIII, IX, XI, XII and the extrinsic, regulated by tissue thromboplastin and factor VII (Figure 1). Both pathways merge through factors V and X, that require calcium and platelet phospholipids, resulting in the formation of fibrin networks known as clots [14,15].

Figure 1. Relationship of coagulation and complement cascades with the fibrinolytic system.

The coagulation cascade has two pathways: the intrinsic and the extrinsic. Both pathways merge through factors V and X, resulting in the formation of clots. The fibrinolytic system relates with the final stage of the coagulation cascade, and its primary function is the proteolytic elimination of clots on blood vessels. Complement C5 can be activated by several coagulation enzymes (thrombin, factor IXa, factor Xa, factor XIa, and kallikrein). Plm can also activate complement through C5 degradation.

The fibrinolytic system participates in the final stage of the coagulation cascade and its primary function is the elimination of clots deposited in the blood vessels mainly through proteolytic action. The central reaction of the fibrinolytic system is the activation of Plg to Plm [16]. Degradation of clots depends on the binding of Plg/Plm to lysine residues located at the C-terminal end and to some internal lysine residues in fibrin networks (and other receptors); Plg binding requires lysine-binding sites (Figure 1) located in Kringle domains [17].

Plm is a broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades fibrin, ECM, and connective tissue through the participation of other proteolytic enzymes, including metalloproteases and collagenase [3]. A large number of pathogens including parasites express Plg receptors that immobilize Plg on their surface resulting in its activation; it has been proposed that the activation of Plg facilitates migration and invasion of these pathogens to different tissues in the host, as well as evasion mechanisms of the immune response, mostly through activation of the complement cascade [18–23].

The coagulation cascade and the complement system

The coagulation and complement cascades are closely associated. A number of studies have demonstrated that coagulation and complement share several activators and inhibitors [24–28]. The complement cascade activation occurs by three distinct but interrelated pathways: the classical, the lectin, and the alternative (Figure 1). The classical pathway is initiated by immune complexes, the lectin pathway is initiated through the binding of the mannose-binding protein (MBP) to bacterial surfaces, and the alternative pathway is initiated by bacterial endotoxin present in the outer surface of bacteria and yeasts [29]. All pathways merge at the level of the C3 convertase before resulting in the formation of the membrane attack complex (C5b-9 or MAC) and the release of several active anaphylatoxins, opsonins, and other active molecules. The complement C5 can be activated by several coagulation enzymes including thrombin, factor IXa, factor Xa, factor XIa, and kallikrein (Figure 1). Plm can also activate complement but degrade C5, thereby preventing C5b deposition and MAC formation, which is a powerful lytic agent in bacterial infections. Both cascades contain a sequence of serine-proteases present in the plasma and serve important roles in innate host defense and hemostasis.

Structure of Plg

Plg is synthesized in the liver as a glycoprotein of 810 amino acids and approximately 90 kDa, also known as Glu-Plg. When secreted into plasma, the signal peptide in the N-terminal end (19 amino acid residues) is lost to become the mature form [30]. Plg can be found in two forms: the Glu-Plg that has a residue of glutamic acid at the N-terminal end and the Lys-Plg having a Lys77 residue at the N-terminal end [31]. Glu-Plg is converted into Lys-Plg by exogenous Plm that removes a 77 amino-terminal peptide [32]. Lys-Plg is more efficiently activated by fibrinolytic activators than Glu-Plg [33,34]. Both forms of Plg are made up of seven structural domains, an activation peptide in the N-terminal region known as the PAp domain (1–77 aa), five Kringle domains (KR1–5), and an SP serine protease domain (562–791 aa) (Figure 2) [35,36]. The Kringle domains mediate Plg-binding by lysine-binding sites (see above), to substrates and to cell surface receptors. The PAp domain interacts with KR4 and KR5, this interaction is critical to maintain a closed conformation of Plg. However, Plg can also be present in its open conformation (pre-activation), suggesting that a conformational rearrangement exposes the cleavage site for the Plg activators (PAs), whose action will result in the formation of Plm, the active protease [36,37].

Figure 2. The structure of human Plg.

Domains are labeled and colored as follows: Pap, blue; KR1, pink; KR2, yellow; KR3, orange; KR4, green; KR5, purple; SP, cyan. The chloride ions (Cl) 1 and 2 are in the interface KR4/PAp and KR2/SP, respectively, and are shown as spheres. Two other chloride ions 3 and 4, bind to the KR2 and SP domain, respectively. The position of the activation loop is marked with a red sphere. The LR of KR1 is marked with an asterisk (*). Figure taken from Law et al. (2012) [38].

Activators and physiological inhibitors of Plg/Plm

The activation of Plg to Plm is mediated by the proteolytic action of two major types of PAs, the tissue-type (tPA) and the urokinase-type (uPA); both activate Plg by cutting specifically between Arg560–Val561 residues, in the SP domain [38]. However, some bacteria secrete different PAs, such as streptokinase (Streptococci, groups A, C, and G), staphylokinase (Staphylococcus aureus lysogenic), Pla (Yersinia pestis), PauA (secreted by Streptococcus uberis), and PadA (Streptococcus dysgalactiae) [39–44]. On the other hand, fibrinolysis is a highly regulated process involved in hemostasis, requiring participation of different inhibitors; best known are α2-antiplasmin and α2-macroglobulin (Plm inhibitors), PAI-1, PAI-2, and PAI-3 (inhibitors of Plg activators) [45–49].

Participation of Plg/Plm in other cellular processes

In addition to its interaction with fibrin, Plg/Plm can act on other proteins such as cell surface receptors, coagulation components (factors V, VIII, and X), metalloproteases, as well as structural components of the ECM, including laminin, fibronectin, complement factors (C3 and C5), vitronectin etc. [13,50–54]. Therefore, Plg/Plm have been associated with several physiological and pathological functions in fibrinolysis and hemostasis, degradation of ECM, tumor growth, invasion, migration, tissue remodeling, wound healing, angiogenesis, and evasion of the immune response [13,55,56].

Role of Plg receptors in sterile and non-sterile conditions

Plg receptors in cancer

Cellular Plg/Plm receptors are ubiquitous, show high affinity for their ligand, and are usually expressed on cell surfaces [1,57,58]. Neoplastic cells behave in several aspects like infectious agents, indeed, Plg-binding proteins have also been involved as a mechanism to evade the innate response against tumor cells. Degradation of ECM is a crucial step in tumor cell invasion and thus, in metastasis. Plg is one of several proteases that facilitate tumor cell motility by disrupting the basement membrane and stromal barriers [59,60]. The presence of actin, enolase-1, cytokeratin 8, and annexin 2 have been associated with poor prognosis and resistance to chemotherapy of malignant tumors in patients. These proteins are overexpressed in cancer cells and have the ability to bind Plg/Plm, making them good diagnostic and prognostic markers, for example in breast, lung, and pancreas carcinomas [58,61]. The critical role of the Plg/Plm system in cancer biology is supported by in vitro and in vivo studies; α-enolase has been identified as a potentially useful candidate for diagnosis and prognosis as well as for therapy using antibodies [55]. In vitro treatment of lung and bone cancer cells with antibodies against α-enolase, as well as with shRNA plasmids, appears to be a promising approach to suppress tumor metastasis, as it inhibits ECM degradation and invasion of cancer cells [13,55]. Moreover, in vivo studies of cancer utilizing Plg-deficient mice, demonstrated a markedly reduced angiogenesis and decreased metastatic potential [62–64].

Plg receptors in bacteria

Recruitment of host proteases on the bacterial surface represents a particularly effective mechanism for increasing invasiveness [65]. One of the protease systems involved is the Plg/Plm; for which over 40 binding proteins have been reported in bacterial species (Table 1) [57]. These proteins include metabolic enzymes, components of signaling pathways, structural proteins, amongst others. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis 13 proteins have been reported, 11 in Borrelia burgdorferi, and 13 in Leptospira interrogans, to mention a few examples. Several models have been proposed in bacterial infections to explain the involvement of these proteins during invasion [2,57]. The degradation of ECM proteins in different bacteria was also evaluated, for example: in Leptospira, bound Plg is converted into Plm by uPA, for degradation of fibronectin and laminin, as evaluated by ELISA [66]. Also, Leptospira enolase-bound Plg has been described to degrade vitronectin [12]. Several examples of Plg receptors have also been described for Mycoplasma species [67,68].

Table 1. Plg-binding proteins in pathogenic bacteria.

| Plg-binding proteins | Bacterial species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 fimbriae | Escherichia coli | [71] |

| OspA | Borrelia burgdorferi | [72] |

| BBA70 | [73] | |

| OspC | [74] | |

| CRASP-1, 3, 4, and 5 | [75] | |

| ErpP, ErpA, and ErpC | [76] | |

| Erp63 | Borrelia spielmanii | [77] |

| DnaK, GroES, GlnA1, Ag85 complex, Mpt51, Mpt64, PrcB, MetK, SahH, Lpd, Icl, Fba, and EF-Tu | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | [78,79] |

| LenA | Leptospira interrogans | [80] |

| Leptospiral surface adhesion, Lsa66 and Lp30 | [81] | |

| LIC12238, LIC10494, LIC12730, LipL32, LipL40, Lp29, Lp49, Lsa20 and Lsa6 | [82] | |

| EF-Tu | [83] | |

| Lsa44 and Lsa45 | [84] | |

| GAPDH | Group A streptococci | [85] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | [86,87] | |

| Bacillus anthracis | [88] | |

| Lactobacillus crispatus | [89] | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | [90] | |

| Clostridium perfringens | [91] | |

| Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae | [92] | |

| Riemerella anatipestifer | [93] | |

| Escherichia coli | [94] | |

| Enolase | Neisseria meningitidis | [95] |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | [96] | |

| Mycoplasma gallisepticum | [67] | |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | [97] | |

| Candida albicans | [98] | |

| Lactobacillus crispatus | [89] | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | [99] | |

| Leptospira interrogans | [12] | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | [100] | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | [101] | |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | Staphylococcus aureus | [102] |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | Group B Stretococcus | [103] |

| Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | [78,79] |

| Neisseria meningitidis | [104] | |

| DNaK and Peroxiredoxin | Neisseria meningitidis | [105] |

| PdhA-C, GAPDH-A, Ldh, Pgm, Pyk, and Tkt | Mycoplasma pneumoniae | [68] |

| Skizzle | Streptococcus agalactiae | [106] |

Abbreviations: Antigen 85, mycolyltransferase, Fn binding protein, Ag85A, Ag85B, and Ag85C; DnaK, heat shock protein 70 or protein chaperone DnaK; EF-Tu, iron-regulated elongation factor TU; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GlnA1, glutamine synthetase A1; GroES, 10-kDa chaperonin; CRASP, surface protein that acquires the complement regulator; Icl, isocitrate lyase; Ldh, lactate dehydrogenase; LHP, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase; MetK, methionine adenosyltransferase; Mpt51, related Ag85 complex protein, with mycolil transferase, Fn binding protein D; Mpt64, immunogenic protein; OspA, outer surface protein A; OspC, outer surface protein C; PdhA-C, pyruvate dehydrogenases A to C; Pgm, phosphoglycerate mutase; PrcB, proteasome β subunit;Pyk, pyruvate kinase; Tkt, transketolase.

Plg/Plm regulates both, coagulation and complement cascades in bacterial infections; interaction with the complement system may help bacteria to evade host’s immune system, facilitating invasion. Plm cleaves human complement proteins C3b and C5 in the presence of L. interrogans proteins: LigA and LigB [69]. Moreover, Lsa23 can block activation of both, alternative and classical pathways of complement. PLG bound to Lsa23 could be converted into Plm, which in turn degrades C3b and C4b [70]. These results suggest that Lsa23 might be involved in complement evasion processes by acting on three different mechanisms and could assist Leptospira to overcome lysis promoted by the MAC.

Plg receptors in fungi

Several fungal pathogenic species express molecules that interact with host proteins during pathogen invasion, colonization, and growth. The ability to interact with host components, including blood, ECM proteins, and human complement regulators, appears to be essential for pathogen survival. Fungal parasite species express Plg-binding proteins (Table 2). Candida species have been reported to exhibit numerous Plg-binding proteins: eight proteins have been reported in Candida albicans: phosphoglycerate mutase, alcohol dehydrogenase, thioredoxin peroxidase, catalase, the transcription elongation factor, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), phosphoglycerate kinase, and fructose bisphosphate aldolase [107]; four proteins have been reported in C. parapsilosis: CPAR2_404780, CPAR2_404800, Ssa2, and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 1 [108]. In the case of Cryptococcus neoformans, 18 proteins have been identified as capable of binding host’s Plg system to allow the fungus to cross tissue barriers, supporting the hypothesis that Plg binding may contribute to trespass the blood–brain barrier [109]. The role of enolase in pathogenicity has also been studied in fungal parasites including Aspergillus nidulans, C. albicans [110], Paracoccidioides brasiliensis [111,112], and Pneumocystis carinii [113]. However, only the role of enolase in the processes of invasion and dissemination of fungal infections has been hypothesized, since no functional studies have been done yet.

Table 2. Plg-binding proteins in pathogenic fungi.

| Plg-binding proteins | Fungi species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pgm, alcohol dehydrogenase, thioredoxin peroxidase,catalase, transcription elongation factor, GAPDH, phosphoglycerate kinase, and fructose bisphosphate aldolase | Candida albicans | [107] |

| Pra1 | [114] | |

| Pgm | [115] | |

| CPAR2_404780, CPAR2_404800, Ssa2, and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 1 | Candida parapsilosis | [108] |

| Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase | Paracoccidioides sp. | [116] |

| Enolase | Aspergillus nidulans and Candida albicans | [110] |

| Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | [111,112] | |

| Pneumocystis carinii | [113] | |

| Thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductade, heparinase | Trichosporon asahii | [117] |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | Cryptococcus neoformans | [118] |

| Not identified | [119] | |

| Hsp70, Cpn60, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, ATP synthase subunit β, Pyk, ATP synthase subunit α, response to stress-related protein, phosphoglycerate kinase, putative uncharacterized protein, ATP synthase γ chain, ATP synthase δ chain, Putative uncharacterized protein, ketol-acid reductoisomerase, Transaldolase, inorganic diphosphatase, dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, glutamate dehydrogenase, enolase | [109] |

Abbreviations: Cpn60, heat shock protein 60; Hsp70, heat shock protein 70; Pgm, phosphoglycerate mutase; Pyk, pyruvate kinase.

Plg receptors in protozoan parasites

The role of Plg for intracellular parasites has been less documented (Table 3). However, involvement of Plg in invasiveness and pathogenesis of some parasites has been clearly shown. For example, it has been reported that binding of Plg/Plm contributes to virulence in Leishmania mexicana. Furthermore, Plg binding has been shown to be highly heterogeneous amongst different morpho-phenotypes of promastigotes, including a Plg-binding increase related to the differentiation of the promastigotes [120]. The course of the infection was also evaluated in a Plg-deficient mice, demonstrating that Plg has an effect on the distribution pattern of these parasites in the lesion produced by L. mexicana, but does not have an effect on the dissemination of the parasite to other organs [121]. L. mexicana enolase has been described to interact with Plg on the surface of the parasite through an internal motif: 249AYDAERKMY257 [122,123]. An activated C-kinase (LACK, Leishmania homolog of receptors for activated C-kinase) also binds Plg; this is a homologous receptor of Leishmania sp. that binds and activates Plg in the presence of tPA through an internal motif similar to that in enolase (260VYDLESKAV268); this being a new function of the protein that could contribute to the invasiveness of the parasite [124].

Table 3. Plg-binding proteins in protozoan parasites.

| Proteins | Parasite species | Binding characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enolase | Leishmania mexicana | - Heterogeneous binding between the morpho-phenotypes of promastigotes - Enolase binds through an internal motif (249AYDAERKMY257) | [120,122] |

| LACK | LACK binds through an internal motif similar to that of enolase (260VYDLESKAV268) | [124] | |

| Enolase | Plasmodium yoelii | The oocysts bind the Plg | [125] |

| Enolase | Plasmodium falciparum | The enolase of the oocysts binds Plg through an internal motif (DKSLVK) | [126] |

| Plasmodium berghei | |||

| Not identified | Trypanosoma cruzi | The trypomastigote and epimastigote bind Plg on its surface | [127,128] |

| Not identified | Trypanosoma evansi | The Plg have greater bonding capacity compared with others from the same family | [129] |

| GAPDH | Trichomonas vaginalis | Natural GAPDH and the recombinant bound to immobilized Plg, FN, and collagen | [130] |

On the other hand, Trypanosoma cruzi during its life cycle alternates between different morphological types: epimastigote, metacyclic trypomastigote in the insect vector, amastigote, and the blood trypomastigote in the mammalian host. The trypomastigote and the epimastigote thrive outside a host cell, which means that they interact directly with host fluids; both show the ability to interact with Plg [127]. This has also been demonstrated and quantitated in epimastigotes [129]. However, T. evansi possess receptors with higher Plg-binding affinity, unlike T. cruzi and other parasites of this family [121].

In the Plasmodium species, the oocysts play an important role in the host’s invasion. The oocysts have to trespass two physical barriers in the insect host: the peritrophic matrix and the midgut epithelium [126]. Enolase in Plasmodium yoelii is associated with nuclear elements, cell membrane, and cytoskeleton, suggesting that it may play non-glycolytic functions such as participating in the host invasion through Plg binding [125]. It was recently reported that the superficial enolase of the P. berghei and P. falciparum oocysts appear to facilitate attachment of the oocysts to the midgut epithelium in the insect, as well as of recruiting Plg through binding to an internal enolase motif (DKSLVK); this interaction is essential for the invasion of the parasite (activated Plg) and for the formation of oocysts [126]. In addition, other components of the fibrinolytic system have been involved in the infection of P. falciparum, such as uPA, which binds on the surface of malaria-infected erythrocytes and could be involved in the merozoite release process [131]. The uPA has also been involved in Toxoplasma gondii infection through a specific receptor (uPAR: uPA receptor), which could be implicated in macrophage rolling and infection through the expression and secretion of MMP-9 metallopeptidase complexes [132].

Plg receptors in helminth parasites

The study of Plg-binding proteins in helminth parasites has been addressed in recent years (Table 4). Most of the studied parasite diseases have a life stage in the circulatory system, in contact with proteins of the fibrinolytic system of the host. Parasites have developed different strategies to evade the immune response of the host; one of them appears to be the recruitment of Plg on the worm’s surface. Plg-binding has been studied in Dirofilaria immitis; an E/S antigen extract of adult worms allowed identification of ten Plg-binding proteins: HSP60, actin-1/3, actin, actin 4, transglutaminase, GAPDH, Ov87, LOAG 14743, galectin, and P22U [7]. Moreover, an extract of surface proteins from adult worms of D. immitis identified eleven proteins, including only two of the abovementioned group: actin-5C, actin-1, enolase, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, GAPDH, MSP protein domain, MSP 2, β-binding lectin-galactosidase, galectin, protein containing the immunoglobulin I-set domain, and cyclophilin Ovcyp-2. It has been suggested that they interact with the host’s fibrinolytic system during invasion [8]. GAPDH and galectin (rDiGAPDH and rDiGAL) recombinants of D. immitis were analyzed as Plg-binding proteins. Results indicated that rDiGAPDH and rDiGAL are able to bind Plg and stimulate the generation of Plm by tPA; this interaction requires participation of lysine residues. They also increased the expression of uPA in canine endothelial cells in culture, which suggests that they promote a favorable habitat free of clots in the intravascular environment of the parasite [133].

Table 4. Plg-binding proteins in helminth parasites.

| Proteins | Parasite species | Binding characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enolase | Onchocerca volvulus | Ov-ENO binds Plg | [134] |

| GAPDH | Ov-GAPDH | [135] | |

| GAPDH | Clonorchis sinensis | rCsGAPDH and rCsANXB30 were able to interact with human Plg in a dose-dependent manner. The interaction could be inhibited by lysine | [136] |

| Annexin B30 | [137] | ||

| Enolase | Fasciola hepatica | Present in the E/S products | [138] |

| HSP60, actin-1/3, actin, actin 4, transglutaminase, GAPDH, Ov87, LOAG 14743, Galectina and P22U | Dirofilaria immitis | In an extract of excretion/secretion antigens of adult worm of D. immitis | [7] |

| Actin-5C, actin-1, enolase, Fba, GAPDH, protein domain MSP, MSP 2, β-galactosidase binding lectin, Galectina, and cyclophilin Ovcyp-2 | In a surface protein extract of adult worms | [8] | |

| Enolase, Actin, GAPDH, ATP: guanidine kinase, Fba, Pgm, Triosephosphate isomerase, adenylate kinase | Schistosoma bovis | In a total extract of worm proteins | [139] |

| Enolase | Echinostoma caproni | Present in the E/S products | [20] |

| Enolase | Taenia multiceps | TmEno is a Plg receptor | [140] |

| Enolase | Taenia pisiformis | rTpEno could bind to Plg and could be converted into active Plm using host-derived activators. Its binding ability was inhibited by ɛACA | [22] |

| Enolase | Taenia solium | Plg-binding proteins of cysticerci; TsEnoA is a Plg receptor | [141,142] |

| Fascicilin-1, Fasciclin-2, MAPK, Annexin, Actin, and cMDH | [142] |

Abbreviations: cMDH, cytosolic malate dehydrogenase; Fba, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; Pgm, phosphoglycerate mutase; ɛACA, ɛ-aminocaproic acid.

On the other hand, in a total protein extract of Schistosoma bovis adult worms, ten Plg-binding proteins were identified: enolase, actin, GAPDH, ATP: guanidine kinase, fructose bisphosphate aldolase, phosphoglycerate mutase, triosephosphate isomerase, adenylate kinase and two hypothetical proteins of S. japonicum [139]. Recombinant annexin and enolase possess the ability to bind and activate Plg, suggesting that they play a role in the maintenance of hemostasis within the blood vessels [21,143]. In the case of cestodes, seven Plg-binding proteins were identified in Taenia solium cysticerci: fascicilin-1, fasciclin-2, enolase, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), annexin, actin, and cytosolic malate dehydrogenase [142]. Recombinant enolase was characterized and showed a strong Plg-binding and activating activity in vitro, suggesting that enolase could play a role in parasite invasion [141,142].

Other examples of helminth infections where parasite proteins have been involved in Plg/Plm binding as an evasion mechanism of the host’s innate defensive response are Clonorchis sinensis, in which GAPDH [136] and annexin B30 have been reported as Plg-binding proteins [137]. Enolases have also been reported as Plg-binding proteins in Onchocerca volvulus [134], Fasciola hepatica [138], Taenia multiceps [140], and T. pisiformis [22].

Plg–enolase interaction

Enolase is perhaps the most studied Plg-binding protein in different organisms. Enolase has been identified as an octamer on the surface of group A streptococci; molecular docking analysis have revealed the fine detail of the Plg-enolase binding. Interaction with KR1 and KR5 domains of Plg occurs through lysine residues located at the C-terminal end of enolase, as well as on another internal binding site. Plg undergoes a conformational change to expose the cut site for PAs in order to induce Plm formation [144].

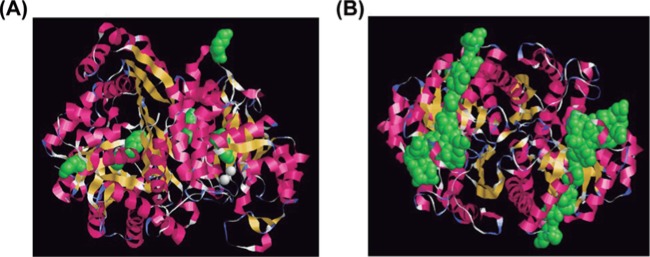

Molecular docking studies have not been carried out for Plg–enolase in parasites; putative Plg-binding sites have been proposed by their similarity with described bacterial binding sites. T. solium enolase (TsEnoA) has been shown to bind Plg [142]; apparently, the internal site of Plg is involved but not the lysine residues at the C-terminal end. This idea is supported by results of assays using ɛ-aminocaproic acid (ɛACA), a synthetic inhibitor of the Plm–Plg system which binds to accessible lysine residues. In order to find out the spatial distribution of Plg-binding sites on TsEnoA, we used the amino acid sequence to predict the protein structure using Swiss-Model and RasMol programs. The lysine residues at the C-terminal end were not exposed (Figure 3A), in contrast with the internal site that appears entirely accessible (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Molecular modeling of T. solium enolase A (TsEnoA) showing Plg binding sites.

(A) Identification of the C-terminal lysine residues are shown in green; (B) identification of the internal Plg-binding motif of T. solium enolase (also shown in green). The modeling was done in: http://www.openrasmol.org/.

Modulation of Plg/Plm function by enolase as a mechanism against host’s innate responses in taeniid parasites

Parasites have developed an intimate molecular relationship with their hosts through evolution, thus requiring a number of host proteins for survival, for example to complement their metabolism [10,133]. It is also well known that although parasites have a vast repertoire of proteases [145,146], they also appear to take advantage of host’s proteases. We have localized TsEnoA binding of Plg/Plm on the surface of T. solium cysticerci [141,142]. As Plm has been involved in the degradation of fibrin clots and ECM, we proposed that binding and activation of Plg might help the parasite to colonize host tissues. Recruitment and activation of Plg has been proposed as a mechanism involved in survival or establishment for other helminths [7,8,139].

Human and porcine cysticercosis is acquired by ingestion of T. solium eggs. Poor hygiene conditions and domestic management of human feces and especially, cohabitation with an adult-worm carrier are factors that facilitate transmission of the disease. Eggs contain hexacanth embryos surrounded by an impermeable and highly resistant envelope called embryophore, which allows survival under adverse environmental conditions. Once in the host’s gut, proteolytic enzymes and bile salts trigger the release and activation of the hexacanth embryo (also known as oncosphere). Activated embryos trespass the host intestinal wall and reach lymphatic and blood capillaries, through which they are distributed to a wide variety of predilection organs and tissues (subcutaneous tissue, skeletal and cardiac muscle, brain, eyes etc.) [147]. Although events occurring after embryos trespassing the intestinal wall remain mostly unexplored, it is known that few weeks are required for an oncosphere to transform into a metacestode known as cysticercus. The mechanisms by which the parasite reaches a predilection tissue, like the central nervous system, where cysticerci causes neurocysticercosis, are also unknown.

Taeniids possess adhesion molecules and metalloproteases able to degrade ECM [148]. Two previous reports have shown that enolase from T. multiceps and T. psiformis bind and activate Plg [22,140]. Enolase of T. solium was also found to be Plg-binding and activating protein [141,142]. Therefore, it appears that binding and activation of Plg might help early larval forms colonize host tissues, as Plm could aid degradation of fibrin clots and ECM. An interesting experiment would be to test treatment of T. crassiceps cysticerci embedded in Matrigel, using antibodies against α-enolase or shRNA plasmids to find out if cysticerci degrade ECM, following a similar strategy to that currently being tested against cancer treatment [13,55]. Thus, the role of parasite proteins that can bind and activate Plg, along with the extensive expression of proteases such as a chymotrypsin-like peptidase, trypsin-like and cathepsin B-like peptidases [149], could be more related to the capacity of parasites to enter through the intestinal mucosa and invade host tissues. We can speculate that Plm can exert an initial role during parasite invasion to host tissues; once established, it is possible that Plm and other proteases could participate in ECM degradation, allowing parasite establishment, growth, and development, as it has been reported for bacteria, protozoan, and helminth parasites. Moreover, no proteases capable of degrading fibrin clots have been found in parasites. T. solium being the only taeniid reaching the CNS, shows the expression of adhesion molecules specific for brain ligands that might be the main factors involved in this tissue-specific parasite invasion.

T. solium and other taeniids possess at least four enolase genes [142]. Except for TsEno4, tapeworm enolase amino acid sequences are not orthologs of vertebrate isoforms; thus, the origin of enolase isoforms in vertebrates and invertebrates is not monophyletic. TsEnoA has been characterized and expressed in bacteria showing a strong Plg-binding and activating activity in vitro. TsEno4 is considerably smaller: 28 compared with 46–49 kDa of the other three T. solium enolases. Preliminary results have shown that TsEno4 lacks enolase activity as well as Plg-binding activity (Ayón-Núñez et al., unpublished). As TsEno4 is the ancestral enolase in cestodes, the fact that it lacks enolase activity suggests that other isoforms fulfilled the need for a glycolytic enzyme function; TsEno4 lost its enzyme activity and perhaps is now involved in other moonlighting functions that are relevant for the parasite. Our current efforts are directed to explore this possibility. Regardless of the TsEno4 case, as Plg has also been implicated as a modulator of fibrinolysis, complement or even the immune response involved in the survival of a number of pathogens, a tantalizing question would be if this is also an adaptive mechanisms in taeniid parasites.

Conclusion

Plg/Plm seems to play a relevant role in several examples of infectious agent relationships, including bacteria as well as protozoan, helminth, and perhaps taeniid parasites; possibly involved in the invasion and migration of the parasites through the tissues of the host. Understanding the interactions of different Plg-binding proteins in parasites will allow realizing a new mechanism of invasion, migration, and/or establishment that has not been addressed.

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- PA

plasminogen activator

- Plg

plasminogen

- Plm

plasmin

- tPA

tissue-type PA

- uPA

urokinase-type PA

Author contribution

D.A.A.-N., G.F., R.J.B. and J.P.L. participated intellectually, practically and approved this manuscript for publication through a one semester special course. D.A.A.-N., R.J.B. and J.P.L. edited the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) [grant number 61334]; the PAPIIT-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) [grant numbers IN 213711, IG200616 (to J.P.L.), IN211217 (to R.J.B.)]; D.A.A.N. is a doctoral student at Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas with fellowship No. 280263 from CONACYT.

References

- 1.Figuera L., Gómez-Arreaza A. and Avilán L. (2013) Parasitism in optima forma: Exploiting the host fibrinolytic system for invasion. Acta Trop. 128, 116–123 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raymond B.B. and Djordjevic S. (2015) Exploitation of plasmin(ogen) by bacterial pathogens of veterinary significance. Vet. Microbiol. 178, 1–13 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.González-Miguel J., Siles-Lucas M., Kartashev V., Morchón R. and Simón F. (2016) Plasmin in parasitic chronic infections: friend or foe? Trends Parasitol. 32, 325–335 10.1016/j.pt.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansell E., Braschi S., Medzihradszky K.F., Sajid M., Debnath M., Ingram J. et al. (2008) Proteomic analysis of skin invasion by blood fluke larvae. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e262 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harnett W. (2014) Secretory products of helminth parasites as immunomodulators. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 195, 130–136 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Y., Wen Y.J., Cai Y.N., Vallée I., Boireau P., Liu M.Y. et al. (2015) Serine proteases of parasitic helminths. Korean J. Parasitol. 53, 1–11 10.3347/kjp.2015.53.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Miguel J., Morchón R., Mellado I., Carretón E., Montoya-Alonso J.A. and Simón F. (2012) Excretory/secretory antigens from Dirofilaria immitis adult worms interact with the host fibrinolytic system involving the vascular endothelium. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 181, 134–140 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González-Miguel J., Morchón R., Carretón E., Montoya-Alonso J.A. and Simón F. (2013) Surface associated antigens of Dirofilaria immitis adult worms activate the host fibrinolytic system. Vet. Parasitol. 196, 235–240 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Counihan N., Chisholm S.A., Bullen H.E., Srivastava A., Sanders P.R., Jonsdottir T.K. et al. (2017) Plasmodium falciparum parasites deploy RhopH2 into the host erythrocyte to obtain nutrients, grow and replicate. Elife 6, e23217 10.7554/eLife.23217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarrete-Perea J., Toledano-Magaña Y., De la Torre P., Sciutto E., Bobes R.J., Soberón X. et al. (2016) Role of porcine serum haptoglobin in the host-parasite relationship of Taenia solium cysticercosis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 207, 61–67 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2016.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aldridge J.R., Jennette M.A. and Kuhn R.E. (2006) Uptake and secretion of host proteins by Taenia crassiceps metacestodes. J. Parasitol. 92, 1101–1102 10.1645/GE-835R.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salazar N., Souza M.C., Biasioli A.G., Silva L.B. and Barbosa A.S. (2017) The multifaceted roles of Leptospira enolase. Res. Microbiol. 168, 157–164 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao K.C., Shih N.Y., Fang H.L., Huang T.S., Kuo C.C., Chu P.Y. et al. (2013) Surface α-enolase promotes extracellular matrix degradation and tumor metastasis and represents a new therapeutic target. PLoS ONE 19, e69354 10.1371/journal.pone.0069354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman M. (2003) Remodeling the blood coagulation cascade. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 16, 17–20 10.1023/B:THRO.0000014588.95061.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapin J.C. and Hajjar K.A. (2015) Fibrinolysis and the control of blood coagulation. Blood Rev. 29, 17–24 10.1016/j.blre.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collen D., Van Hoef B., Schlott B., Hartmann M., Guhrs K.H. and Lijnen H.R. (1993) Mechanisms of activation of mammalian plasma fibrinolytic systems with streptokinase and with recombinant staphylokinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 216, 307–314 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marti D.N., Hu C.K., An S.S., von Haller P., Schaller J. and Llinás M. (1997) Ligand preferences of kringle 2 and homologous domains of human plasminogen: canvassing weak, intermediate, and high-affinity binding sites by 1H-NMR. Biochemistry 30, 11591–11604 10.1021/bi971316v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pancholi V. and Chhatwal G.S. (2003) Housekeeping enzymes as virulent factors for pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293, 391–401 10.1078/1438-4221-00283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xolalpa W., Vallecillo A.J., Lara M., Mendoza-Hernandez G., Comini M., Spallek R. et al. (2007) Identification of novel bacterial plasminogen-binding proteins in the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proteomics 7, 3332–3341 10.1002/pmic.200600876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcilla A., Pérez-García A., Espert A., Bernal D., Muñoz-Antolí C., Esteban J.G. et al. (2007) Echinostoma caproni: identification of enolase in excretory/secretory products, molecular cloning, and functional expression. Exp. Parasitol. 117, 57–64 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De la Torre-Escudero E., Manzano-Román R., Pérez-Sánchez R., Siles-Lucas M. and Oleaga A. (2010) Cloning and characterization of a plasminogen-binding surface-associated enolase from Schistosoma bovis. Vet. Parasitol. 173, 76–84 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S., Guo A., Zhu X., You Y., Hou J., Wang Q. et al. (2015) Identification and functional characterization of alpha-enolase from Taenia pisiformis metacestode. Acta Trop. 144, 31–40 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siqueira G.H., Atzingen M.V., de Souza G.O., Vasconcellos S.A. and Nascimento A.L. (2016) Leptospira interrogans Lsa23 protein recruits plasminogen, factor H and C4BP from normal human serum and mediates C3b and C4b degradation. Microbiology 162, 295–308 10.1099/mic.0.000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber-Lang M., Sarma J.V., Zetoune F.S., Rittirsch D., Neff T.A., McGuire S.R. et al. (2006) Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat. Med. 12, 682–687 10.1038/nm1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krarup A., Wallis R., Presanis J.S., Gál P. and Sim R.B. (2007) Simultaneous activation of complement and coagulation by MBL-associated serine protease 2. PLoS ONE 18, e623 10.1371/journal.pone.0000623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amara U., Flierl M.A., Rittirsch D., Klos A., Chen H., Acker B. et al. (2010) Molecular intercommunication between the complement and coagulation systems. J. Immunol. 185, 5628–5636 10.4049/jimmunol.0903678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulla K.C., Gupta K., Krarup A., Gal P., Schwaeble W.J., Sim R.B. et al. (2010) Activation of mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases leads to generation of a fibrin clot. Immunology 129, 482–495 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03200.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanse S.M., Declerck P.J., Ruf W., Broze G. and Etscheid M. (2012) Factor VII-activating protease promotes the proteolysis and inhibition of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 427–433 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.238394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amara U., Rittirsch D., Flierl M., Bruckner U., Klos A., Gebhard F. et al. (2008) Interaction between the coagulation and complement system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 632, 71–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castellino F.J. and Powell J.R. (1981) Human plasminogen. Methods Enzymol. 80, 365–378 10.1016/S0076-6879(81)80031-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forsgren M., Råden B., Israelsson M., Larsson K. and Hedén L.O. (1987) Molecular cloning and characterization of a full-length cDNA clone for human plasminogen. FEBS Lett. 213, 254–260 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81501-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horrevoets A.J., Smilde A.E., Fredenburgh J.C., Pannekoek H. and Nesheim M.E. (1995) The activation-resistant conformation of recombinant human plasminogen is stabilized by basic residues in the amino-terminal hinge region. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 15770–15776 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L., Gong Y., Grella D.K., Castellino F.J. and Miles L.A. (2003) Endogenous plasmin converts Glu-plasminogen to Lys-plasminogen on the monocytoid cell surface. J. Thromb. Haemost. 1, 1264–1270 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markus G., Evers J.L. and Hobika G.H. (1978) Comparison of some properties of native (Glu) and modified (Lys) human plasminogen. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 733–739 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novokhatny V.V., Kudinov S.A. and Privalov P.L. (1984) Domains in human plasminogen. J. Mol. Biol. 179, 215–232 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90466-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Law R.H., Caradoc-Davies T., Cowieson N., Horvath A.J., Quek A.J., Encarnacao J.A. et al. (2012) The X-ray crystal structure of full-length human plasminogen. Cell Rep. 1, 185–190 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponting C.P., Marshall J.M. and Cederholm-Williams S.A. (1992) Plasminogen: a structural review. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 3, 605–614 10.1097/00001721-199210000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rijken D.C. and Lijnen H.R. (2009) New insights into the molecular mechanisms of the fibrinolytic system. J. Thromb. Haemost. 7, 4–13 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lähteenmäki K., Kuusela P. and Korhonen T.K. (2001) Bacterial plasminogen activators and receptors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25, 531–552 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collen D., Van Hoef B., Schlott B., Hartmann M., Guhrs K.H. and Lijnen H.R. (1993) Mechanisms of activation of mammalian plasma fibrinolytic systems with streptokinase and with recombinant staphylokinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 216, 307–314 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X., Lin X., Loy J., Tang J. and Zhang X. (1998) Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of human plasmin complexed with streptokinase. Science 281, 1662–1665 10.1126/science.281.5383.1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dentovskaya S.V., Platonov M.E., Svetoch T.E., Kopylov P.K., Kombarova T.I., Ivanov S.A. et al. (2016) Two isoforms of Yersinia pestis plasminogen activator Pla: intraspecies distribution, intrinsic disorder propensity, and contribution to virulence. PLoS ONE 11, e0168089 10.1371/journal.pone.0168089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosey E.L., Lincoln R.A., Ward P.N., Yancey R.J. and Leigh J.A. (1999) PauA: a novel plasminogen activator from streptococcus uberis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 180, 353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh S., Bhando T. and Dikshit K.L. (2014) Fibrin-targeted plasminogen activation by plasminogen activator, PadA, from Streptococcus dysgalactiae. Protein Sci. 23, 714–722 10.1002/pro.2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kruithof E.K. (1988) Plasminogen activator inhibitors. Enzyme 40, 113–121 10.1159/000469153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rijken D.C. (1995) Plasminogen activators and plasminogen activator inhibitors: biochemical aspects. Baillieres Clin. Haematol. 8, 291–312 10.1016/S0950-3536(05)80269-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pawse A.R. and Tarachand U. (1997) Clot lysis: role of plasminogen activator inhibitors in haemostasis and therapy. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 35, 545–552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicholl S.M., Roztocil E. and Davies M.G. (2006) Plasminogen activator system and vascular disease. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 4, 101–116 10.2174/157016106776359880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rijken D.C. and Lijnen H.R. (2009) New insights into the molecular mechanisms of the fibrinolytic system. J. Thromb. Haemost. 7, 4–13 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kost C., Benner K., Stockmann A., Linder D. and Preissner K.T. (1996) Limited plasmin proteolysis of vitronectin. Characterization of the adhesion protein as morphoregulatory and angiostatin-binding factor. Eur. J. Biochem. 236, 682–688 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0682d.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pryzdial E.L., et al. (1999) Plasmin converts factor X from coagulation zymogen to fibrinolysis cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 8500–8505 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cesarman-Maus G. and Hajjar K.A. (2005) Molecular mechanisms of fibrinolys. Br. J. Haem. 129, 307–321 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05444.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ogiwara K., Nogami K., Nishiya K. and Shima M. (2010) Plasmin-induced procoagulant effects in the blood coagulation: a crucial role of coagulation factors V and VIII. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 21, 568–576 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32833c9a9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barthel D., Schindler S. and Zipfel P.F. (2012) Plasminogen is a complement inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 18831–18842 10.1074/jbc.M111.323287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Principe M., Borgoni S., Cascione M., Chattaragada M.S., Ferri-Borgogno S., Capello M. et al. (2017) Alpha-enolase (ENO1) controls alpha v/beta 3 integrin expression and regulates pancreatic cancer adhesion, invasion, and metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 10, 16 10.1186/s13045-016-0385-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miles L.A. and Parmer R.J. (2013) Plasminogen receptors: the first quarter century. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 39, 329–337 10.1055/s-0033-1334483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanderson-Smith M.L., De Oliveira D.M., Ranson M. and McArthur J.D. (2012) Bacterial plasminogen receptors: mediators of a multifaceted relationship. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 272148 10.1155/2012/272148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Didiasova M., Wujak L., Wygrecka M. and Zakrzewicz D. (2014) From plasminogen to plasmin: role of plasminogen receptors in human cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 21229–21252 10.3390/ijms151121229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwaan H.C. and McMahon B. (2009) The role of plasminogen-plasmin system in cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. 148, 43–66 10.1007/978-0-387-79962-9_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Godier A. and Hunt B.J. (2013) Plasminogen receptors and their role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory, autoimmune and malignant disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 11, 26–34 10.1111/jth.12064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ceruti P., Principe M., Capello M., Cappello P. and Novelli F. (2013) Three are better than one: plasminogen receptors as cancer theranostic targets. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2, 12 10.1186/2162-3619-2-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oh C.W., Hoover-Plow J. and Plow E.F. (2003) The role of plasminogen in angiogenesis in vivo. J. Thromb. Haemost. 1, 1683–1687 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perides G., Zhuge Y., Lin T., Stins M.F., Bronson R.T. and Wu J.K. (2006) The fibrinolytic system facilitates tumor cell migration across the blood-brain barrier in experimental melanoma brain metastasis. BMC Cancer 6, 56 10.1186/1471-2407-6-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Almholt K., Juncker-Jensen A., Lærum O.D., Johnsen M., Rømer J. and Lund L.R. (2013) Spontaneous metastasis in congenic mice with transgenic breast cancer is unaffected by plasminogen gene ablation. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 30, 277–288 10.1007/s10585-012-9534-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martínez-García S., Rodríguez-Martínez S., Cancino-Diaz M.E. and Cancino-Diaz J.C. (2018) Extracellular proteases of Staphylococcus epidermidis: roles as virulence factors and their participation in biofilm. APMIS 126, 177–185 10.1111/apm.12805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vieira M.L., Atzingen M.V., Oliveira R., Mendes R.S., Domingos R.F., Vasconcellos S.A. et al. (2012) Plasminogen binding proteins and plasmin generation on the surface of Leptospira spp.: the contribution to the bacteria-host interactions. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 758513 10.1155/2012/758513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen H., Yu S., Shen X., Chen D., Qiu X., Song C. et al. (2011) The Mycoplasma gallisepticum α-enolase is cell surface-exposed and mediates adherence by binding to chicken plasminogen. Microb. Pathog. 51, 285–290 10.1016/j.micpath.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gründel A., Friedrich K., Pfeiffer M., Jacobs E. and Dumke R. (2015) Subunits of the pyruvate dehydrogenase cluster of Mycoplasma pneumoniae are surface-displayed proteins that bind and activate human plasminogen. PLoS ONE 10, e0126600 10.1371/journal.pone.0126600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castiblanco-Valencia M.M., Fraga T.R., Pagotto A.H., Serrano S.M., Abreu P.A., Barbosa A.S. et al. (2016) Plasmin cleaves fibrinogen and the human complement proteins C3b and C5 in the presence of Leptospira interrogans proteins: a new role of LigA and LigB in invasion and complement immune evasion. Immunobiology 221, 679–689 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Siqueira G.H., Atzingen M.V., de Souza G.O., Vasconcellos S.A. and Nascimento A.L. (2016) Leptospira interrogans Lsa23 protein recruits plasminogen, factor H and C4BP from normal human serum and mediates C3b and C4b degradation. Microbiology 162, 295–308 10.1099/mic.0.000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kukkonen M., Saarela S., Lähteenmäki K., Hynönen U., Westerlund-Wikström B., Rhen M. et al. (1998) Identification of two laminin-binding fimbriae, the type 1 fimbria of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and the G fimbria of Escherichia coli, as plasminogen receptors. Infect. Immun. 66, 4965–4970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fuchs H., Wallich R., Simon M.M. and Kramer M.D. (1994) The outer surface protein A of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi is a plasmin (ogen) receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 12594–12598 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koenigs A., Hammerschmidt C., Jutras B.L., Pogoryelov D., Barthel D., Skerka C. et al. (2013) BBA70 of Borrelia burgdorferi is a novel plasminogen-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 25229–25243 10.1074/jbc.M112.413872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Önder Ö., Humphrey P.T., McOmber B., Korobova F., Francella N., Greenbaum D.C. et al. (2012) OspC is potent plasminogen receptor on surface of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 16860–16868 10.1074/jbc.M111.290775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hallström T., Haupt K., Kraiczy P., Hortschansky P., Wallich R., Skerka C. et al. (2010) Complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 1 of Borrelia burgdorferi binds to human bone morphogenic protein 2, several extracellular matrix proteins, and plasminogen. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 490–498 10.1086/653825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brissette C.A., Haupt K., Barthel D., Cooley A.E., Bowman A., Skerka C. et al. (2009) Borrelia burgdorferi infection-associated surface proteins ErpP, ErpA, and ErpC bind human plasminogen. Infect. Immun. 77, 300–306 10.1128/IAI.01133-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seling A., Siegel C., Fingerle V., Jutras B.L., Brissette C.A., Skerka C. et al. (2010) Functional characterization of Borrelia spielmanii outer surface proteins that interact with distinct members of the human factor H protein family and with plasminogen. Infect. Immun. 78, 39–48 10.1128/IAI.00691-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xolalpa W., Vallecillo A.J., Lara M., Mendoza-Hernandez G., Comini M., Spallek R. et al. (2007) Identification of novel bacterial plasminogen binding proteins in the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proteomics 7, 3332–3341 10.1002/pmic.200600876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.De la Paz Santangelo M., Gest P.M., Guerin M.E., Coinçon M., Pham H., Ryan G. et al. (2011) Glycolytic and non-glycolytic functions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, an essential enzyme produced by replicating and non-replicating bacilli. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40219–40231 10.1074/jbc.M111.259440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Verma A., Brissette C.A., Bowman A.A., Shah S.T., Zipfel P.F. and Stevenson B. (2010) Leptospiral endostatin-like protein A is a bacterial cell surface receptor for human plasminogen. Infect. Immun. 78, 2053–2059 10.1128/IAI.01282-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oliveira R., Maria de Morais Z., Gonçales A.P., Romero E.C., Vasconcellos S.A. and Nascimento A.L.T.O. (2011) Characterization of novel OmpA-like protein of Leptospira interrogans that binds extracellular matrix molecules and plasminogen. PLoS ONE 6, e21962 10.1371/journal.pone.0021962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vieira M.L., Atzingen M.V., Oliveira T.R., Oliveira R., Andrade D.M., Vasconcellos S.A. et al. (2010) In vitro identification of novel plasminogen-binding receptors of the pathogen Leptospira interrogans. PLoS ONE 5, e11259 10.1371/journal.pone.0011259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wolff D.G., Castiblanco-Valencia M.M., Abe C.M., Monaris D., Morais Z.M., Souza G.O. et al. (2013) Interaction of Leptospira elongation factor Tu with plasminogen and complement factor H: a metabolic leptospiral protein with moonlighting activities. PLoS ONE 8, e81818 10.1371/journal.pone.0081818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fernandes L.G., Vieira M.L., Alves I.J., de Morais Z.M., Vasconcellos S.A., Romero E,C. et al. (2014) Functional and immunological evaluation of two novel proteins of Leptospira spp. Microbiology 160, 149–164 10.1099/mic.0.072074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pancholi V. and Fischetti V.A. (1992) A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. J. Exp. Med. 176, 415–426 10.1084/jem.176.2.415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bergmann S., Rohde M. and Hammerschmidt S. (2004) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a surface-displayed plasminogen-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 72, 2416–2419 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2416-2419.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moreau C., Terrasse R., Thielens N.M., Vernet T., Gaboriaud C. and Di Guilmi A.M. (2017) Deciphering key residues involved in the virulence-promoting interactions between Streptococcus pneumoniae and human plasminogen. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 2217–2225 10.1074/jbc.M116.764209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matta S.K., Agarwal S. and Bhatnagar R. (2010) Surface localized and extracellular Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Bacillus anthracis is a plasminogen binding protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 2111–2120 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hurmalainen V., Edelman S., Antikainen J., Baumann M., Lähteenmäki K. and Korhonen T.K. (2007) Extracellular proteins of Lactobacillus crispatus enhance activation of human plasminogen. Microbiology 153, 1112–1122 10.1099/mic.0.2006/000901-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Glenting J., Beck H.C., Vrang A., Riemann H., Ravn P., Hansen A.M. et al. (2013) Anchorless surface associated glycolytic enzymes from Lactobacillus plantarum 299v bind to epithelial cells and extracellular matrix proteins. Microbiol. Res. 168, 245–253 10.1016/j.micres.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Matsunaga N., Shimizu H., Fujimoto K., Watanabe K., Yamasaki T., Hatano N. et al. (2018) Expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase on the surface of Clostridium perfringens cells. Anaerobe 51, 124–130 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu W., Zhang Q., Li J., Wei Y., Cai C., Liu L. et al. (2017) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase acts as an adhesin in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae adhesion to porcine endothelial cells and as a receptor in recruitment of host fibronectin and plasminogen. Vet. Res. 48, 16 10.1186/s13567-017-0421-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gao J.Y., Ye C.L., Zhu L.L., Tian Z.Y. and Yang Z.B. (2014) A homolog of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Riemerella anatipestifer is an extracellular protein and exhibits biological activity. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 15, 776–787 10.1631/jzus.B1400023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aguilera L., Ferreira E., Giménez R., Fernández F.J., Taulés M., Aguilar J. et al. (2012) Secretion of the housekeeping protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by the LEE-encoded type III secretion system in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44, 955–962 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Knaust A., Weber M.V.R., Hammerschmidt S., Bergmann S., Frosch M. and Floden O.K. (2007) Cytosolic proteins contribute to surface plasminogen recruitment of Neisseria meningitides. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3246–3255 10.1128/JB.01966-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Floden A.M., Watt J.A and Brissette C.A. (2011) Borrelia burgdorferi enolase is a surface-exposed plasminogen binding protein. PLoS ONE 6, e27502 10.1371/journal.pone.0027502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mundodi V., Kucknoor A.S. and Alderete J.F. (2008) Immunogenic and plasminogen-binding surface-associated α-enolase of Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect. Immun. 76, 523–531 10.1128/IAI.01352-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jong A.Y., Chen S.H., Stins M.F., Kim K.S., Tuan T.L. and Huang S.H. (2003) Binding of Candida albicans enolase to plasmin (ogen) results in enhanced invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 52, 615–622 10.1099/jmm.0.05060-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vastano V., Capri U., Candela M., Siciliano R.A., Russo L., Renda M. et al. (2013) Identification of binding sites of Lactobacillus plantarum enolase involved in the interaction with human plasminogen. Microbiol. Res. 168, 65–72 10.1016/j.micres.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rahi A., Matta S.K., Dhiman A., Garhyan J., Gopalani M., Chandra S. et al. (2017) Enolase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a surface exposed plasminogen binding protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1861, 3355–3364 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thomas C., Jacobs E. and Dumke R. (2013) Characterization of pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit B and enolase as plasminogen-binding proteins in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Microbiology 159, 352–365 10.1099/mic.0.061184-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Furuya H. and Ikeda R. (2011) Interaction of triosephosphate isomerase from Staphylococcus aureus with plasminogen. Microbiol. Immunol. 55, 855–862 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2011.00392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Boone T.J. and Tyrrell G.J. (2012) Identification of the actin and plasminogen binding regions of group B streptococcal phosphoglycerate kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29035–29044 10.1074/jbc.M112.361261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shams F., Oldfield N.J., Lai S.K., Tunio S.A., Wooldridge K.G. and Turner D.P.J. (2016) Fructose‐1,6‐bisphosphate aldolase of Neisseria meningitidis binds human plasminogen via its C‐terminal lysine residue. Microbiol. Open 5, 340–350 10.1002/mbo3.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Knaust A., Weber M.V., Hammerschmidt S., Bergmann S., Frosch M. and Kurzai O. (2007) Cytosolic proteins contribute to surface plasminogen recruitment of Neisseria meningitidis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3246–3255 10.1128/JB.01966-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wiles K.G., Panizzi P., Kroh H.K. and Bock P.E. (2010) Skizzle is a novel plasminogen- and plasmin-binding protein from Streptococcus agalactiae that targets proteins of human fibrinolysis to promote plasmin generation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21153–21164 10.1074/jbc.M110.107730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Crowe J.D., Sievwright I.K., Auld G.C., Moore N.R., Gow N.A. and Booth N.A. (2003) Candida albicans binds human plasminogen: identification of eight plasminogen-binding proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 1637–1651 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Karkowska-Kuleta J., Zajac D., Bras G., Bochenska O., Rapala-Kozik M. and Kozik A. (2017) Binding of human plasminogen and high-molecular-mass kininogen by cell surface-exposed proteins of Candida parapsilosis. Acta Biochim. Pol. 64, 391–400 10.18388/abp.2017_1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stie J., Bruni G. and Fox D. (2009) Surface-associated plasminogen binding of Cryptococcus neoformans promotes extracellular matrix invasion. PLoS ONE 4, e5780 10.1371/journal.pone.0005780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Funk J., Schaarschmidt B., Slesiona S., Hallström T., Horn U. and Brock M. (2016) The glycolytic enzyme enolase represents a plasminogen-binding protein on the surface of a wide variety of medically important fungal species. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 306, 59–68 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Marcos C.M., de Fátima da Silva J., de Oliveira H.C., Moraes da Silva R.A., Mendes-Giannini M.J. and Fusco-Almeida A.M. (2012) Surface-expressed enolase contributes to the adhesion of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis to host cells. FEMS Yeast Res. 12, 557–570 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2012.00806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nogueira S.V., Fonseca F.L., Rodrigues M.L., Mundodi V., Abi-Chacra E.A., Winters M.S. et al. (2010) Paracoccidioides brasiliensis enolase is a surface protein that binds plasminogen and mediates interaction of yeast forms with host cells. Infect Immun. 78, 4040–4050 10.1128/IAI.00221-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fox D. and Smulian A.G. (2001) Plasminogen-binding activity of enolase in the opportunistic pathogen Pneumocystis carinii. Med. Mycol. 39, 495–507 10.1080/mmy.39.6.495.507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Luo S., Poltermann S., Kunert A., Rupp S. and Zipfel P.F. (2009) Immune evasion of the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans: Pra1 is a factor H, FHL-1 and plasminogen binding surface protein. Mol. Immunol. 47, 541–550 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Poltermann S., Kunert A., von der Heide M., Eck R., Hartmann A. and Zipfel P.F. (2007) Gpm1p is a factor H-, FHL-1-, and plasminogen-binding surface protein of Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37537–37544 10.1074/jbc.M707280200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chaves E.G., Weber S.S., Báo S.N., Pereira L.A., Bailão A.M., Borges C.L. et al. (2015) Analysis of Paracoccidioides secreted proteins reveals fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase as a plasminogen-binding protein. BMC Microbiol. 27, 53 10.1186/s12866-015-0393-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ikeda R., Ichikawa T., Miyazaki Y., Shimizu N., Ryoke T., Haru K. et al. (2014) Detection and characterization of plasminogen receptors on clinical isolates of Trichosporon asahii. FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 1186–1195 10.1111/1567-1364.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ikeda R. and Ichikawa T. (2014) Interaction of surface molecules on Cryptococcus neoformans with plasminogen. FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 445–450 10.1111/1567-1364.12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stie J. and Fox D. (2014) Blood-brain barrier invasion by Cryptococcus neoformans is enhanced by functional interactions with plasmin. Microbiology 158, 240–258 10.1099/mic.0.051524-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Calcagno M., Avilan L., Colasante C., Berrueta L. and Salmen S. (2002) Interaction of different Leishmania mexicana morphotypes with plasminogen. Parasitol. Res. 88, 972–978 10.1007/s00436-002-0688-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Maldonado J., Calcagno M., Puig J., Maizo Z. and Avilan L. (2006) A study of cutaneous lesions caused by Leishmania mexicana in plasminogen-deficient mice. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 80, 289–294 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vanegas G., Quiñones W., Carrasco-López C., Concepción J.L., Albericio F. and Avilán L. (2007) Enolase as a plasminogen binding protein in Leishmania mexicana. Parasitol. Res. 101, 1511–1516 10.1007/s00436-007-0668-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Quiñones W., Peña P., Domingo-Sananes M., Cáceres A., Michels P.A., Avilan L. et al. (2007) Leishmania mexicana: molecular cloning and characterization of enolase. Exp. Parasitol. 116, 241–251 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gómez-Arreaza A., Acosta H., Barros-Álvarez X., Concepción J.L., Albericio F. and Avilan L. (2011) Leishmania mexicana: LACK (Leishmania homolog of receptors for activated C-kinase) is a plasminogen binding protein. Exp. Parasitol. 127, 752–761 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bhowmick I.P., Vora H.K. and Jarori G.K. (2007) Sub-cellular localization and post-translational modifications of the Plasmodium yoelii enolase suggest moonlighting functions. Malar. J. 16, 45 10.1186/1475-2875-6-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ghosh A.K., Coppens I., Gårdsvoll H., Ploug M. and Jacobs-Lorena M. (2011) Plasmodium ookinetes coopt mammalian plasminogen to invade the mosquito midgut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17153–17158 10.1073/pnas.1103657108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Almeida L., Vanegas G., Calcagno M., Concepción J.L. and Avilan L. (2004) Plasminogen Interaction with Trypanosoma cruzi. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 99, 63–67 10.1590/S0074-02762004000100011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rojas M., Labrador I., Concepción J.L., Aldana E. and Avilan L. (2008) Characteristics of plasminogen binding to Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Acta Trop. 107, 54–58 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Acosta H., Rondón-Mercado R., Avilán L. and Concepción J.L. (2016) Interaction of Trypanosoma evansi with the plasminogen-plasmin system. Vet. Parasitol. 226, 189–197 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lama A., Kucknoor A., Mundodi V. and Alderete J.F. (2009) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is a surface-associated, fibronectin-binding protein of Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect. Immun. 77, 2703–2711 10.1128/IAI.00157-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Roggwiller E., Fricaud A.C., Blisnick T. and Braun-Breton C. (1997) Host urokinase-type plasminogen activator participates in the release of malaria merozoites from infected erythrocytes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 86, 49–59 10.1016/S0166-6851(97)02848-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Schuindt S.H., Oliveira B.C., Pimentel P.M., Resende T.L., Retamal C.A., DaMatta R.A. et al. (2012) Secretion of multi-protein migratory complex induced by Toxoplasma gondii infection in macrophages involves the uPA/uPAR activation system. Vet. Parasitol. 186, 207–215 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.González-Miguel J., Morchón R., Siles-Lucas M., Oleaga A. and Simón F. (2015) Surface-displayed glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and galectin from Dirofilaria immitis enhance the activation of the fibrinolytic system of the host.. Acta Trop. 145, 8–16 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jolodar A., Fischer P., Bergmann S., Büttner D.W., Hammerschmidt S. and Brattig N.W. (2003) Molecular cloning of an alpha-enolase from the human filarial parasite Onchocerca volvulus that binds human plasminogen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1627, 111–120 10.1016/S0167-4781(03)00083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Erttmann K.D., Kleensang A., Schneider E., Hammerschmidt S., Büttner D.W. and Gallin M. (2005) Cloning, characterization and DNA immunization of an Onchocerca volvulus glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Ov-GAPDH). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1741, 85–94 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hu Y., Zhang E., Huang L., Li W., Liang P., Wang X. et al. (2014) Expression profiles of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Clonorchis sinensis: a glycolytic enzyme with plasminogen binding capacity. Parasitol. Res. 113, 4543–4553 10.1007/s00436-014-4144-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.He L., Ren M., Chen X., Wang X., Li S., Lin J. et al. (2014) Biochemical and immunological characterization of annexin B30 from Clonorchis sinensis excretory/secretory products. Parasitol. Res. 113, 2743–2755 10.1007/s00436-014-3935-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bernal D., de la Rubia J.E., Carrasco-Abad A.M., Toledo R., Mas-Coma S. and Marcilla A. (2004) Identication of enolase as a plasminogen-binding protein in excretory/secretory products of Fasciola hepatica. FEBS Lett. 563, 203–206 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00306-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ramajo-Hernández A., Pérez-Sánchez R., Ramajo-Martín V. and Oleaga A. (2007) Schistosoma bovis: plasminogen binding in adults and the identification of plasminogen-binding proteins from the worm tegument. Exp. Parasitol. 115, 83–91 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Li W.H., Qu Z.G., Zhang N.Z., Yue L., Jia W.Z., Luo J.X. et al. (2015) Molecular characterization of enolase gene from Taenia multiceps. Res. Vet. Sci. 102, 53–58 10.1016/j.rvsc.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhang S., You Y., Luo X., Zheng Y. and Cai X. (2018) Molecular and biochemical characterization of Taenia solium α-enolase. Vet. Parasitol. 254, 36–42 10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ayón-Núñez D.A., Fragoso G., Espitia C., García-Varela M., Soberón X., Rosas G. et al. (2018) Identification and characterization of Taenia solium enolase as a plasminogen-binding protein. Acta Trop. 182, 69–79 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Figueiredo B.C., Dádara A.A., Oliveira S.C. and Skelly P.J. (2015) Schistosomes enhance plasminogen activation: the role of tegumental enolase. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005335 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Cork A.J., Ericsson D.J., Law R.H., Casey L.W., Valkov E., Bertozzi C. et al. (2015) Stability of the octameric structure affects plasminogen-binding capacity of streptococcal enolase. PLoS ONE 10, e0121764 10.1371/journal.pone.0121764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Akpunarlieva S., Weidt S., Lamasudin D., Naula C., Henderson D., Barrett M. et al. (2017) Integration of proteomics and metabolomics to elucidate metabolic adaptation in Leishmania. J. Proteomics 155, 85–98 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.White A.C. Jr, Molinari J.L., Pillai A.V. and Rege A.A. (1992) Detection and preliminary characterization of Taenia solium metacestode proteases. J. Parasitol. 78, 281–287 10.2307/3283475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Flisser A., Rodríguez-Canul R. and Willingham A.L. III (2006) Control of the taeniosis/cysticercosis complex: future developments. Vet. Parasitol. 139, 283–292 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Singh S.K., Singh A.K., Prasad K.N., Singh A., Singh A., Rai R.P. et al. (2015) Expression of adhesion molecules, chemokines and matrix metallo- proteinases (MMPs) in viable and degenerating stage of Taenia solium metacestode in swine neurocysticercosis. Vet Parasitol. 214, 59–66 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zimic M.J., Infantes J., López C., Velásquez J., Farfán M., Pajuelo M. et al. (2007) Comparison of the peptidase activity in the oncosphere excretory/secretory products of Taenia solium and Taenia saginata. J. Parasitol. 93, 727–734 10.1645/GE-959R.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]