Abstract

Migrations from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP) to other temperate regions represent one of the main biogeographical patterns for the Northern Hemisphere. However, the ages and routes of these migrations are largely not known. We aimed to reconstruct a well-resolved and dated phylogeny of Hippophae L. (Elaeagnaceae) and test hypothesis of a westward migration of this plant out of the QTP across Eurasian mountains in the Miocene. We produced two data matrices of five chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) and five nuclear DNA markers for all distinct taxa of Hippophae. These matrices were used to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships in the genus. In dating analyses, we first estimated the stem node age of Elaeagnaceae using five fossil records evenly distributed across a tree of Rosales. We used this estimate and two fossil records to calibrate the cpDNA and nDNA phylogenies of Hippophae. The same phylogenies were used to reconstruct ancestral areas within the genus. The monophyly of Hippophae, all five species, and most of subspecies was strongly supported by both plastid and nuclear data sets. Diversification of Hippophae likely started in central Himalayas/southern Tibet in the early Miocene and all extant distinct species had probably originated by the middle Miocene. Diversification of Hippophae rhamnoides likely started in the late Miocene east of the QTP from where this species rapidly expanded to central and western Eurasia. Our findings highlight the impact of different stages in uplift of the QTP and Eurasian mountains and climatic changes in the Neogene on diversification and range shifts in the highland flora on the continent. The results provide support to the idea of an immigration route for some European highland plants from their ancestral areas on the QTP across central and western mountain ranges of Eurasia in the late Miocene.

Keywords: Asian mountains, ecological opportunity, long-distance dispersal, molecular dating, range expansion, Rosales, vicariance

Introduction

The Neogene geological processes and climatic changes had tremendous impact on the evolution of biota in different regions of Eurasia (e.g., Comes and Kadereit, 2003; Hewitt, 2004). The Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP) was a central part of these processes (Tang and Shen, 1996; Zheng et al., 2000; An et al., 2001; Li et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2002; Molnar, 2005). It is also one of the most important global biodiversity and evolutionary hot spots (Myers et al., 2000; Mittermeier et al., 2005; López-Pujol et al., 2011). Recent phylogenetic analyses suggest that many genera of the Northern Hemisphere (NH) temperate plants with the highest diversity in the highlands of Asia originated in the QTP and adjacent regions, and then expanded their ranges to other NH regions (e.g., Wang Y.J. et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2013; Roquet et al., 2013). These studies support in general the hypothesis that the QTP has served for long as a major source of migrants to west Eurasia and a craddle of diversification (Wulff, 1943; Axelrod et al., 1996; Comes and Kadereit, 2003). However, ages of disjunction and migration from the QTP to west Eurasia for different ecological groups are not clear yet. Few phylogenetic analyses of taxa with Eurasian ranges have been reported (for a recent review, see Kadereit et al., 2008) and even less studies used dated phylogenies and explicit ancestral area reconstructions for these taxa. Lack of detailed information on direction and ages of migrations in Eurasia, thus prevents studying impact of changes in geology and climate on evolution of different ecological groups of Eurasian flora.

Ecology and distribution of Hippophae L. are highly relevant to the problem of migrations of NH highland plants and their evolutionary responses to the Neogene orogeneses and climatic changes across Eurasia. This shrub or small tree is dioecious, wind-pollinated, and fruits of most species in the genus are juicy favoring long-distance dispersal by birds (Rousi, 1971; Lian et al., 1998). Roots of Hippophae form nitrogen-fixing nodules (Bond et al., 1956) and possess an efficient dual symbiosis with mycorrhiza and Frankia (Tian et al., 2002). The symbiosis enables Hippophae to colonize infertile and bare soil after disturbance (e.g., landslides, flash floods, and dune migration), stabilizing riverbanks, steep slopes, and dunes (Bartish and Swenson, 2004; Bartish, 2016). These plants are therefore early-successional pioneers with habitat engineering function for their communities. Hippophae can also serve as a representative of Eurasian distribution and east-central-west disjunctions for mountainous plants (Rousi, 1971; Hyvönen, 1996; Jia et al., 2012). According to the latest detailed revision of the genus by Swenson and Bartish (2002), Hippophae includes 15 infraspecific taxa in seven species, two of which are putative hybrids with uncertain taxonomic status (H. goniocarpa and H. litangensis). All species in the genus are restricted to the QTP region and adjacent areas, except for H. rhamnoides that is distributed widely but fragmentally in Asia and Europe (see Figure 1). Based on floristic, paleobotanical, and geological inferences, Bobrov (1962) suggested east to west migrations of Myricaria germanica (L.) Desv. (Tamaricaceae) and H. rhamnoides L. along Eurasian mountain ranges in the Sarmatian, which corresponds to a geological age from the middle to late Miocene (Berggren and Van Couvering, 1974). In contrast, using phylogenetic analyses of morphological characters Hyvönen (1996) suggested a west to east migration followed by range fragmentation and vicariance. Jia et al. (2012) were the first to reconstruct ancestral areas and migration routes for all taxa in H. rhamnoides and found support for the hypothesis of the east QTP origin and westward migration. They also estimated ages of diversification within H. rhamnoides and suggested that it diversified mostly in the Quaternary. However, this study lacked sufficient power to resolve the relationships among the western subspecies; and its age estimates relied exclusively on secondary calibrations, which can result in considerable age underestimates (Sauquet et al., 2012). The oldest fossil records of H. rhamnoides for long were known only from the late Pleistocene (Lang, 1994). Nevertheless, in a recent study, fossil pollen grains of the species that range in age from the late Miocene to the early Pleistocene were reported from several localities in southern Europe (Biltekin, 2010). In view of these latest advances in paleobotany, it becomes obvious that ages of diversifications within the genus, and of the putative migration from the east QTP to west Eurasia should be reconsidered. Given the range and ecological characteristics of Hippophae, we assume that application of robust phylogenetic reconstructions and accurate dating across the whole genus can provide useful insights into floristic turnovers on the continent in the Neogene.

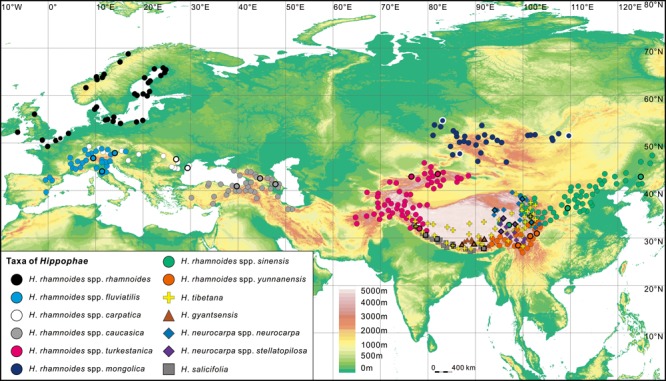

FIGURE 1.

Geographic distribution range of Hippophae L. (see Materials and Methods) and the sampling sites (thick outlines; details in Table 1).

Here, we report molecular phylogenetic, fossil-calibrated dating, and ancestral area reconstructions in a thorough sample of all distinct taxa (species/subspecies) of Hippophae accepted by Swenson and Bartish (2002). We sampled three populations per taxon across its range, and five DNA fragments each from chloroplast and nuclear genome. Due to the lack of fossil records and unkonwn age of the stem node of Hippophae, we performed the molecular dating analysis in two stages. The first used five deep fossil calibration points in a multi-gene data set including all genera of Elaeagnaceae and all families of Rosales. The second used chloroplast and nuclear sequences of Hippophae, two fossils, and a secondary calibration point of Elaeagnaceae stem node derived from the first stage. We believe this sampling effort and dating strategy are both necessary and sufficient to answer the following questions. (1) When and where did all distinct taxa in Hippophae originate? (2) When and how exactly did the evolutionary processes in these taxa result in their current disjunct ranges across Eurasia from East Asia to Europe? We discuss later how answering these questions can contribute to a better understanding of the impact of the Neogene orogeneses and climatic changes on evolutionary processes in biota of Eurasian highlands.

Materials and Methods

Data Set of Rosales

We used an earlier published multi-gene data set of 25 Rosales taxa (Zhang et al., 2011) and extended it by including six more species (Hippophae tibetana and salicifolia, Shepherdia argentea and canadensis, and Elaeagnus angustifolia and umbellata) from Elaeagnaceae and one more plastid region (trnL-F). The final data set comprised 11 plastid (rbcL, atpB, matK, the psbBTNH region (=4 genes), rpoC2, ndhF, rps4, and trnL-F) and two nuclear genes (18S and 26S nuclear ribosomal DNA) for 31 species of Rosales. Individual gene alignments were concatenated into a supermatrix of characters with unsampled values coded as missing data. We chose Begonia (Begoniaceae) as outgroup to root the tree of Rosales based on Zhang et al. (2011). Details of GenBank accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Data Sets of Hippophae L.

Based on the key of Swenson and Bartish (2002) and geographic information, we sampled three populations for each distinct taxon of the genus Hippophae. This sampling design aimed to obtain representatives across whole ranges and/or main lineages of each taxon, and to allow us robust tests of reciprocal monophyly and ancestral area reconstructions for all taxa. Geographic representation of the main lineages within the following taxa was inferred from the literature: H. tibetana (Wang et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2011), H. neurocarpa (Kou et al., 2013), H. gyantsensis (Jia et al., 2016), and H. rhamnoides ssp. yunnanensis and sinensis (Jia et al., 2012). Within H. salicifolia and several subspecies of H. rhamnoides (ssp. caucasica, fluviatilis, mongolica, and turkestanica), phylogeographic relationships have not yet been resolved using informative sequences from a comprehensive sample of populations. We therefore selected three representative populations across geographic range of each of these taxa. Finally, H. rhamnoides ssp. carpatica and rhamnoides were shown to be closely related with a broad sharing of the same cpDNA haplotype among multiple populations (Bartish et al., 2002, 2006), we thus used three populations to represent the two subspecies across their joint range. Three species from the other two genera of the family Elaeagnaceae (Elaeagnus triflora, E. umbellata, and Shepherdia argentea) were also used in our phylogenetic and dating analyses on Hippophae. Included materials, voucher information and sources are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sampling information of Hippophae L. Three species from Shepherdia Nutt. and Elaeagnus L. were included.

| Taxon | Population | Herbarium | Voucher | Location | Collector | Year of collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. salicifolia | 4079 | IBP | PRA-00004079 | Hildum, Humla, Nepal | R. Maan | 2009 |

| 09XZ040 | LZU | LiuJQ-09XZ-LZT-040 | Gongri, Xizang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2009 | |

| P | AMU | P | Chamoli, Uttaranchal, India | S. Raina | 2011 | |

| H. gyantsensis | 06252 | LZU | Liu-06252 | Tingri, Xizang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2006 |

| 06217 | LZU | Liu-06217 | Khangmar, Xizang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2006 | |

| 2568 | LZU | 2568 | Lhasa, Xizang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2004 | |

| H. neurocarpa | ||||||

| ssp. neurocarpa | YNG1 | LZU | YNG1/4 | Golmud, Qinghai, China | J-Q. Liu | 2003 |

| 1522 | LZU | 1522 | Qilian, Qinghai, China | J-Q. Liu | 2003 | |

| MM-31 | LZU | MM-31 | Jiuzhi, Qinghai, China | J-Q. Liu | 2007 | |

| ssp. stellatopilosa | Ao129 | LZU | Ao129 | Dingqing, Xizang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2005 |

| QML1 | LZU | QML1-2 | Qumalai, Qinghai, China | J-Q. Liu | 2003 | |

| Ao111 | LZU | Ao111 | Shiqu, Sichuan, China | J-Q. Liu | 2005 | |

| H. tibetana | 07138 | LZU | Liu-07138 | Jilong, Xizang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2007 |

| Henan | LZU | Henan | Henan, Qinghai, China | J.-Q. Liu | 2008 | |

| ST | AMU | ST | Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, India | S. Raina | 2011 | |

| H. rhamnoides | ||||||

| ssp. yunnanensis | 06309 | LZU | Liu-06309 | Deqin, Yunnan, China | J-Q. Liu | 2006 |

| 06321 | LZU | Liu-06321 | Daofu, Sichuan, China | J-Q. Liu | 2006 | |

| 06324 | LZU | Liu-06324 | Xiaojin, Sichuan, China | J.-Q. Liu | 2006 | |

| ssp. sinensis | Ao96 | LZU | Ao96 | Yushu, Qinghai, China | J-Q. Liu | 2005 |

| 05276 | LZU | Liu-05276 | Ganquan, Shaanxi, China | J-Q. Liu | 2005 | |

| 05179 | LZU | Liu-05179 | Xifeng, Liaoning, China | J-Q. Liu | 2005 | |

| H. rhamnoides | ||||||

| ssp. turkestanica | GL | LZU | GL | Gongliu, Xinjiang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2005 |

| SKZ | AMU | SKZ | Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, India | S. Raina | 2011 | |

| 12413 | S | S08-12413 | Almaty, Kazakhstan | L. Stenberg | 2008 | |

| ssp. mongolica | 05047 | LZU | Liu-05047A | Bu’erjin, Xinjiang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2005 |

| 6667 | IBP | PRA-00006667 | Novokizhiginsk, Buryatiya, Russia | I. Bartish; A. Borisyuk | 2012 | |

| 6657 | IBP | PRA-00006657 | Berdsk, Novosibirskaya, Russia | I. Bartish; A. Borisyuk | 2012 | |

| ssp. caucasica | 0402 | SUA | 0402-1-36 | Usukhchay, Dagestan, Russia | M. Rabadanov | 1998 |

| 21286 | S | S09-21286 | Kazbegi, Georgia | J. Klakenberg | 1993 | |

| 9835 | SUA | 2898492 | Hazi Mehmet, Turkey | M. Kucuk | 1996 | |

| ssp. fluviatilis | SW1 | LZU | Liu-SW1 | Wildhaus, Switzerland | Y-M. Yuan | 2005 |

| 6757 | IBP | PRA-00006757 | Il Mulino, Firenzuola, Italy | I. Bartish; I. Schanzer | 2012 | |

| 6682 | IBP | PRA-00006682 | Kirchdorf an der Krems, Austria | I. Bartish; I. Schanzer | 2012 | |

| ssp. carpatica | 9897 | SUA | 9897-13-5 | Gheorghe, Romania | P. Mladin | 1998 |

| 9898 | SUA | 9898-13-16 | Serpeni, Romania | P. Mladin | 1998 | |

| ssp. rhamnoides | 6672 | IBP | PRA-00006672 | Oostduinkerke, Belgium | F. Verloove | 2012 |

| Elaeagnus triflora | IVB-29 | S | IVB-29 | Glen Allyn, Queensland, Australia | I. Bartish; A. Ford | 2004 |

| Elaeagnus umbellata | 07078 | LZU | Liu-07078 | Jilong, Xizang, China | J-Q. Liu | 2007 |

| Shepherdia argentea | 6777 | IBP | PRA-00006777 | Canadaa | P. Sekerka | 2011 |

Herbarium: IBP, Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic; LZU, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China; AMU, Amity University, New Delhi, India; S, Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden; SUA, Balsgård research station, University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, Sweden. aCultivated in Botanical Garden of Prague City, Troja, Czech Republic. ACCID: 1993.00168, Canada IS 237.

We used DNeasyTM Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany) to isolate total genomic DNA from silica gel dried leaves. We sequenced five chloroplast DNA (cpDNA: trnCGCA-ycf6, trnDGUC-trnTGGU, trnLUAA-trnFGAA, trnSUGA-trnfMCAU, and trnSGCU-trnGUCC) and five nuclear DNA regions (nDNA: At103, G3pdh, ITS, Ms, and Tpi) for all taxa. Primers used for amplification and sequencing of these regions are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in 25 μL reaction mixture volumes using reagents and manufacturer’s instruction for Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific, United States) in a Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Germany). PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany) and sequencing reactions were conducted with ABI Prism BigdyeTM Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, United States). Sequences were obtained using an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). MEGA v.4 (Tamura et al., 2007) was used to align produced sequences and adjust them manually.

Chloroplast and nuclear sequences were concatenated separately to make two data sets. We chose Rhamnus davurica (Rhamnaceae) as outgroup to root the tree, according to Zhang et al. (2011) and our results (Supplementary Figure S1). Available outgroup sequences were taken from GenBank. Newly generated sequences were deposited in GenBank (Supplementary Table S3). GAPCODER (Young and Healy, 2003) was used to edit indels as separate characters for inclusion in Bayesian analyses.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Partitioned Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses were conducted on the three concatenated data sets. Bayesian inference was performed in MRBAYES v.3.2.1 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). We determined the best fitting model of sequence evolution for each individual region using the Akaike Information Criterion (Akaike, 1974) as employed in JMODELTEST v.2.1.3 (Darriba et al., 2012). Two independent runs with one cold and three incrementally heated Monte Carlo Markov chains (MCMCs) were run for 5,000,000 generations, with trees sampled every 500th generation. A standard discrete model (Lewis, 2001) was applied to the indel matrix. Model parameters were unlinked across partitions. We discarded the first 2,500 trees out of the 10,001 trees as burn-ins and used the remaining trees to build a 50% majority rule consensus tree.

Maximum likelihood analyses were performed using RAxML v.7.2.7 (Stamatakis, 2006). A separate General Time Reversible + Gamma model (GTR + G) of nucleotide substitution was specified for each data partition, and 500 independent searches were conducted. Support values for nodes in the phylogenetic tree were estimated across 1,000 pseudoreplicates using the GTR + CAT model (Stamatakis et al., 2008) and mapped thereafter onto the best-scoring tree from the 500 independent searches.

Selection of Fossils for Calibration

We constrained the maximum age of the crown node of Rosales using maximum age estimate for this node (103 Ma) from Wang H. et al. (2009). This study was based on a comprehensive sample of families from Rosids (represented by 104 species), sequences of 12 genes (10 cpDNA and two nDNA), and on seven fossil records to calibrate the tree. This sampling effort indicates that estimates of ages of diversification among the sampled orders, including the stem and crown nodes of Rosales, can be fairly robust. We selected from paleobotanical literature five fossil records, which can define the minimum ages of the stem nodes of respective taxa and clades in our tree (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S4). Celtis aspera (Newberry) Manchester, Akhmetiev, and Kodrul was selected based on well-preserved endocarps and leaves from numerous localities in North America and Asia in the late Paleocene and leaves throughout the Paleocene in North America (Manchester et al., 2002). We used the late Paleocene records of this fossil species in our analyses to calibrate the stem node of Celtis. Triorites minutipori Muller was selected based on pollen from Turonian–Senonian (Coniacian) of Malaysia (Muller, 1968), which was considered later as a reliable representative of Ulmaceae (Muller, 1981). This fossil was used therefore to calibrate the stem node of Ulmaceae. Paliurus clarnensis Burge & Manchester has a set of morphological apomorphies to assign this fossil species reliably to extant Paliurus (Burge and Manchester, 2008). We calibrated by this fossil the stem node of Hovenia, which in our sample represents the crown node of Paliureae (Richardson et al., 2000; Islam and Simmons, 2006). Compound drupes of Ficus L. were described from the early Eocene London Clay Flora by Chandler (1962) and can be used to calibrate the stem node of Ficus in our sample. Leaves of Shepherdia weaveri Becker were described from the late Eocene flora of southwestern Montana (Becker, 1960) and recently included into a revised list of paleotaxa from this locality by Lielke et al. (2012), who also provided revised geochronology for the locality. We used this fossil species and age of its geological stratum to calibrate the stem node of Shepherdia in our sample. Fossil pollen grains of H. rhamnoides from the late Miocene (Melinte-Dobrinescu et al., 2009) of Anatolia and south of the Balkan peninsula document the earliest records of the genus (Biltekin, 2010). The fossil cannot be reliably assigned to any subspecies within H. rhamnoides due to the lack of diagnostic characters (Sorsa, 1971). Nevertheless, molecular phylogenetic analyses (Bartish et al., 2000; Jia et al., 2012) and ancestral area reconstructions (Jia et al., 2012) suggested that geographic localities of these records can represent an ancestral area of the strongly supported monophyletic group of the four western subspecies (ssp. carpatica, caucasica, fluviatilis, and rhamnoides). We used therefore this fossil record to calibrate the minimum age of the stem node of the group (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S4).

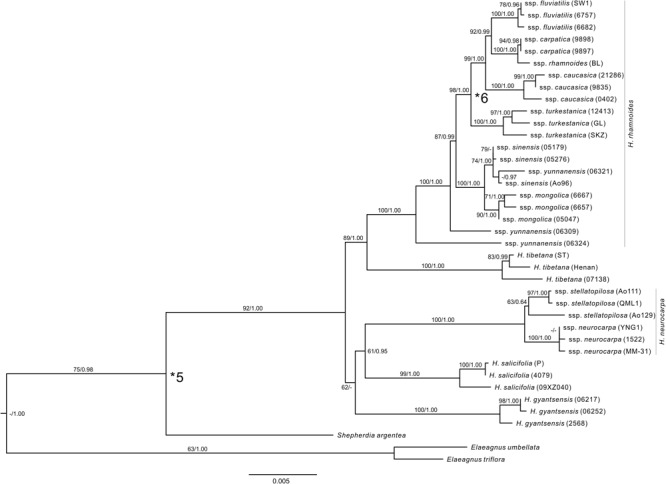

FIGURE 2.

The ML tree of Hippophae L. from the combined cpDNA fragments. Support values (ML Bootstrap percentage/Bayesian posterior probability) are provided at nodes. Fossil calibrations were used at nodes indicated with asterisks (see Supplementary Table S4).

Divergence Time Estimation in Rosales and Hippophae

We used penalized likelihood (PL) and Bayesian inference methods, implemented in R8S v.1.71 (Sanderson, 2002, 2003) and BEAST v.1.7.5 (Drummond et al., 2012), respectively, to infer divergence times in both Rosales and Hippophae phylogenies. For PL analyses, the ML trees with branch lengths (phylograms) obtained with RAXML were used. The outgroups were pruned from the trees prior to all analyses. The smoothing parameters (λ) were determined by cross-validation analysis. We used the truncated-Newton (TN) algorithm as recommended for PL in R8S manual and chose the additive penalty over the log penalty due to our balanced calibrations in the trees. All fossil constraints were applied as minimum ages, while secondary calibrations were enforced as maximum age constraints. Confidence intervals for the divergence date estimates were obtained in a bootstrap-based approach. We used the best-scoring ML tree as a fixed topology and estimated sets of branch lengths from 1,000 bootstrap replicates using the software RAXML (Sauquet et al., 2012). Divergence dates were estimated from the resulting 1,000 trees using the software R8S. Settings were as described above, except that the smoothing parameters were fixed to the values obtained for the original data sets.

For Bayesian analyses, two different uncorrelated lognormal (UCLN) relaxed clock models with fossils treated as being drawn from either a uniform distribution (UCLN-uniform) or a lognormal distribution (UCLN-lognormal) were implemented. For uniform priors, fossil constraints were implemented as hard minimum bounds. For lognormal priors, the ages of the fossils were set as offset values with Log (mean) = 0 and Log (SD) = 1. Age ranges for secondary calibrations were all implemented as uniform priors. The optimal model of molecular evolution selected in JMODELTEST was specified for each partition, and a Yule prior was specified for the tree. We initiated MCMC analyses from ultrametric starting tree with branch lengths that satisfied the calibration constraints. We sampled all parameters once every 1,000 steps from 10,000,000 MCMC steps, with the first 25% of samples discarded as burn-in. The program TRACER v.1.5.0 (Rambaut and Drummond, 2007) was used to examine convergence of chains to the stationary distribution. Trees then were compiled into a maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree using TREEANNOTATOR v.1.7.5 (Drummond et al., 2012) to display mean node ages and highest posterior density (HPD) intervals at 95% (upper and lower) for each node.

Ancestral Area Reconstructions in Hippophae

We ran Bayesian dispersal-vicariance analyses (Bayes-DIVA) using RASP v.3.1 (Yu et al., 2015) to infer the biogeographical history of Hippophae based on both cpDNA and nDNA data sets. In this analysis, we defined nine regions across the range of Hippophae (Figure 1; Rousi, 1971; Chinese Virtual Herbarium1; Global Biodiversity Information Facility2) according to the floristic regionalization of China (Wu et al., 2011) and the world (Takhtajan, 1986): (A) the south QTP (the central Himalayas and southern Tibet); (B) the east QTP (the Hengduan); (C) the north QTP (Tangut); (D) the west QTP (including Tianshan, Pamir, Hindu Kush, and Karakoram); (E) northern China; (F) the Mongolian Plateau (including Altai-Sayan and South Siberian Plain); (G) the Caucasus and Anatolian highlands; (H) Carpathians and Europe north of Alps; and (I) the Alps, Apennines, and Pyrenees. We loaded 10,001 trees previously produced in BEAST and chose the F81 model for the Bayesian MCMC analyses, allowing for different rates of change among ancestral areas. Additionally, for comparative purposes, we implemented the dispersal-extinction-cladogenesis model in RASP v.3.1 as well, with maximum range size set to two.

Results

Phylogenetic Relationships of Rosales and Elaeagnaceae

Based on the data set consisting of 18,335 aligned nucleotide sites for the 13 gene partitions (Supplementary Table S5), we reconstructed the phylogeny of Rosales. ML and BI approaches yielded an identical topology with slightly different support values (Supplementary Figure S1). Within the family Elaeagnaceae, the three genera were each strongly (BP = 100%; PP = 1.00) supported as monophyletic, and Elaeagnus were sister to the well-supported (BP = 100%; PP = 1.00) clade of Hippophae and Shepherdia.

Phylogenetic Relationships of Hippophae Based on cpDNA

The combined cpDNA matrix of Hippophae included a total of 5,462 aligned base pairs (Supplementary Table S6). The ML analysis with RAXML yielded a well-resolved phylogenetic tree (Figure 2). The monophyly of Hippophae was strongly supported (BP = 92%). All taxa of Hippophae except for H. rhamnoides ssp. sinensis and yunnanensis were recovered as monophyletic with strong statistical support (BP > 90% for all taxa except H. neurocarpa ssp. stellatopilosa with BP = 63%). H. gyantsensis, H. salicifolia, and H. neurocarpa formed a clade with a low support (BP = 62%). This clade was sister to the moderately (BP = 89%) supported clade composed of H. tibetana and H. rhamnoides. Within H. rhamnoides, two lineages of ssp. yunnanensis were placed basal to the clade including the other taxa. The latter clade consisted of two sub-clades, both receiving strong support (BP > 98%). One of these sub-clades included ssp. sinensis and mongolica, the second one included ssp. turkestanica, and the four other Asia Minor/European subspecies (ssp. caucasica, carpatica/rhamnoides, and fluviatilis, all listed here as ordered in the grade). Tree topology recovered from Bayesian analysis was largely congruent with the ML tree. The main discrepancy regarded the unresolved relationships between H. gyantsensis and the other two clades containing H. neurocarpa/H. salicifolia and H. tibetana/H. rhamnoides, respectively (Figure 2).

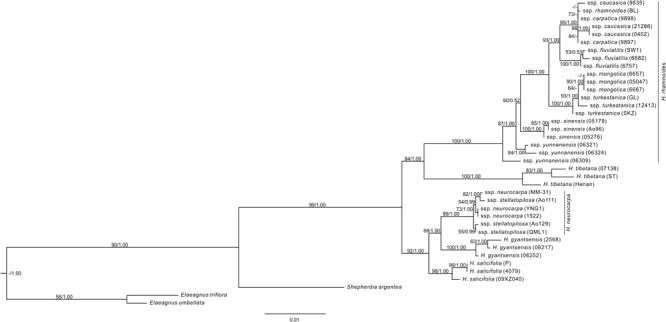

Phylogenetic Relationships of Hippophae Based on Nuclear DNA

The aligned length of the combined nuclear DNA matrix of Hippophae was 2,958 base pairs (Supplementary Table S6). The monophyly of Hippophae was strongly supported by both the ML and Bayesian methods (BP = 99%, PP = 1.00; Figure 3). The clade of H. gyantsensis, H. neurocarpa, and H. salicifolia received strong support (BP = 92%; PP = 1.00), in which H. salicifolia was sister to the sub-clade of the other two taxa, and all species were monophyletic with strong support (BP > 98%; PP = 1.00). H. tibetana was placed sister to H. rhamnoides in the moderately (BP = 84%) to strongly (PP = 1.00) supported clade where each species is monophyletic with strong support (BP = 100%; PP = 1.00). Within H. rhamnoides, we found incongruence with cpDNA phylogenetic placement of H. rhamnoides ssp. mongolica: it formed a strongly supported (BP = 90%; PP = 1.00) clade within ssp. turkestanica. Additionally, monophyly of ssp. carpatica, caucasica, and yunnanensis was not supported.

FIGURE 3.

The ML tree of Hippophae L. from the combined nDNA fragments. Support values (ML Bootstrap percentage/Bayesian posterior probability) are provided at nodes.

Divergence Time Estimates Within Elaeagnaceae

In general, PL and two Bayesian analyses (performed in MRBAYES v.3.2.1 and in BEAST v.1.7.5) yielded similar estimates of ages with largely overlapping confidence intervals (Supplementary Tables S7–S9). We thus report the divergence times estimated under the Bayesian UCLN-lognormal model in the following text. Ages of the stem and crown nodes for Elaeagnaceae were estimated to 89.3 (95% HPD: 85.7–93.0) and 40.6 (95% HPD: 36.9–44.0) Ma, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S7). We enforced 44.1 Ma (upper 95% HPD interval under the UCLN-uniform model) as maximum age of the crown node of Elaeagnaceae in the dating analyses of Hippophae.

Estimation of Ages and Ancestral Area Reconstructions Within Hippophae

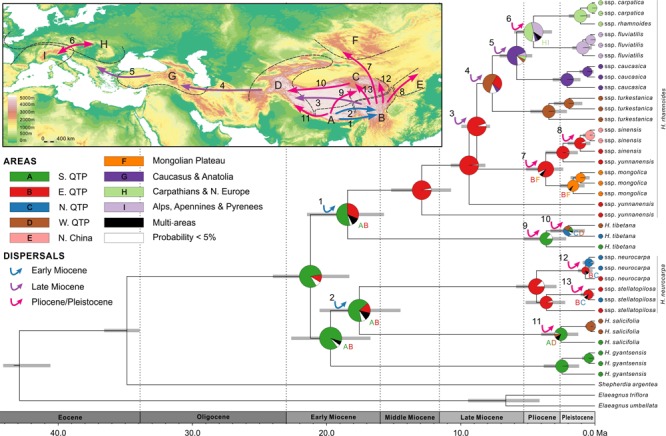

According to our age estimates based on cpDNA, all species within Hippophae had diversified in the early Miocene (21.2–17.6 Ma; Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S8). RASP Bayes-DIVA analyses provided relatively strong evidence that the ancestral area for Hippophae was in the south QTP with a marginal probability (MP) of 81.1% (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S8). The ancestral areas of H. neurocarpa and H. tibetana were inferred to be the east QTP (MP = 87.4%) and the south QTP (MP = 86.4%), respectively. Additionally, results of our dating analyses suggested that ages of diversification within most taxa in the genus were not older than the late Pliocene or Pleistocene (3.6–0.2 Ma).

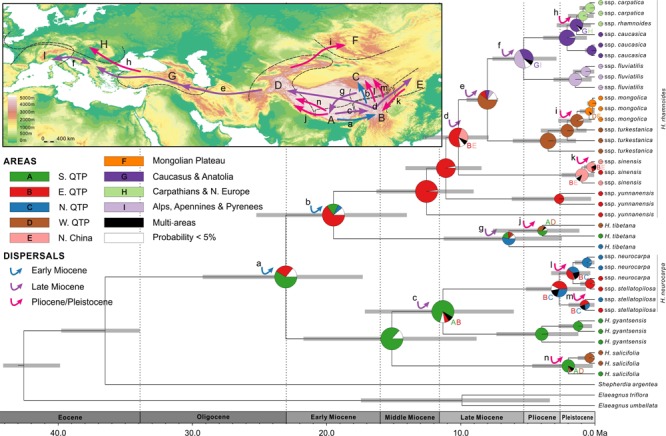

FIGURE 4.

Combined chronogram and biogeographical analysis of Hippophae L. based on cpDNA data. Divergence times were derived from Bayesian analysis treating priors on fossils as being drawn from a lognormal distribution. Gray bars represent 95% credible intervals. Node charts show the marginal probabilities of alternative ancestral distributions from Bayesian dispersal-vicariance analysis (Bayes-DIVA) implemented in RASP. Multiple area distributions were labeled with respective colored characters. The detected dispersal events by Bayes-DIVA analysis are shown with colorful arrows on the chronogram and map. See Table 2 for age and probability estimates of the inferred dispersals.

Diversification within H. rhamnoides started in the middle Miocene and proceeded to the early Pliocene (12.9–3.7 Ma). This species had a high probability (MP = 96.7%) of ancestral area in the east QTP, from where several lineages had dispersed to the west QTP (dispersal 3: 8.8 Ma), north to the Mongolian Plateau (dispersal 7: 3.7 Ma), and northeast to Northern China (dispersal 8: 1.1 Ma) (Figure 4 and Table 2). Our analyses also indicated subsequent westward dispersals out of the west QTP (dispersal 4: 7.6 Ma) and Asia Minor (dispersal 5: 5.8 Ma). Finally, the species dispersed from Carpathians to Alps (dispersal 6: 4.6 Ma). All dispersals were followed by vicariance events, according to the RASP analyses. Additionally, we inferred three local extinction events for ancestors of H. neurocarpa, H. rhamnoides ssp. turkestanica, and a clade of Asia Minor/European subspecies of H. rhamnoides, occurring in the south, east, and west QTP, respectively. We also noted some different biogeographical scenarios at nodes with the lowest relative probabilities. In particular, results of these analyses indicated two roughly contemporaneous dispersals from the west QTP to Asia Minor and Europe, respectively. However, these uncertainties do not influence our main conclusions specified in Discussion.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of the 13 dispersal events detected in the Hippophae cpDNA phylogeny using Bayesian dispersal-vicariance analysis implemented in RASP.

| Dispersal events | AAR of parent node |

AAR of daughter node |

Age of parent node (Ma) |

Age of daughter node (Ma) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MP | 2 | MP | 1 | MP | 2 | MP | Mean | 95% HPD | Mean | 95% HPD | |

| 1 | A | (52.7) | B | (31.8) | B | (96.7) | AB | (2.6) | 18.4 | (15.7–21.5) | 12.9 | (10.7–15.2) |

| 2 | A | (67.0) | B | (15.0) | B | (87.4) | AB | (4.3) | 17.6 | (14.5–20.5) | 4.4 | (2.9–5.9) |

| 3 | B | (94.4) | BD | (1.4) | D | (53.6) | B | (27.3) | 8.8 | (7.8–10.0) | 7.6 | (7.2–8.2) |

| 4 | D | (53.6) | B | (27.3) | G | (69.9) | I | (7.4) | 7.6 | (7.2–8.2) | 5.8 | (4.7–7.1) |

| 5 | G | (69.9) | I | (7.4) | H | (44.2) | I | (37.4) | 5.8 | (4.7–7.1) | 4.6 | (3.2–6.0) |

| 6 | H | (44.2) | I | (37.4) | I | (98.6) | HI | (1.0) | 4.6 | (3.2–6.0) | 0.9 | (0.2–1.7) |

| 7 | B | (88.5) | BF | (6.7) | F | (93.3) | BF | (5.6) | 3.7 | (2.4–5.1) | 1.6 | (0.8–2.6) |

| 8 | B | (93.3) | BE | (4.7) | E | (94.5) | BE | (4.7) | 1.1 | (0.3–2.0) | 0.4 | (0.01–0.9) |

| 9 | A | (86.4) | B | (2.8) | C | (43.1) | D | (28.6) | 3.6 | (2.1–5.3) | 2.0 | (0.8–3.3) |

| 10 | C | (43.1) | D | (28.6) | D | – | – | – | 2.0 | (0.8–3.3) | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | A | (75.9) | AD | (11.0) | D | (97.4) | AD | (2.2) | 2.5 | (1.2–4.0) | 0.3 | (0.003–0.7) |

| 12 | B | (79.0) | BC | (11.7) | C | (95.7) | BC | (3.7) | 0.7 | (0.2–1.3) | 0.5 | (0.05–0.9) |

| 13 | B | (84.6) | BC | (10.8) | C | – | – | – | 0.5 | (0.05–1.1) | 0 | 0 |

Dispersal numbers and area codes refer to Figure 4. For ancestral area reconstructions (ARR), the first two areas with the highest marginal probability (MP; in percent) are reported for both the parent and daughter nodes of each dispersal event. Age estimates are derived from Bayesian relaxed clock analysis treating priors on fossils as being drawn from a lognormal distribution. The mean date in million years ago (Ma) and the 95% highest posterior density intervals are given for each parent and daughter node.

RASP analysis based on nDNA well supported the diversification within Hippophae in the early Miocene and its origination in the south QTP (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S9). The detected 14 dispersal events (dispersals a-n; Table 3) were estimated to have occurred in the early Miocene, late Miocene, and the Pliocene/Pleistocene, respectively. However, unlike the reconstructions based on cpDNA, a dispersal from the west QTP to the Mongolian Plateau was indicated instead (dispersal i: 1.3 Ma). Besides, an additional dispersal from the north QTP to the south QTP was detected (dispersal g: 6.6 Ma).

FIGURE 5.

Combined chronogram and biogeographical analysis of Hippophae L. based on nDNA data. Divergence times were derived from Bayesian analysis treating priors on fossils as being drawn from a lognormal distribution. Gray bars represent 95% credible intervals. Node charts show the marginal probabilities of alternative ancestral distributions from Bayesian dispersal-vicariance analysis (Bayes-DIVA) implemented in RASP. Multiple area distributions were labeled with respective colored characters. The detected dispersal events by Bayes-DIVA analysis are shown with colorful arrows on the chronogram and map. See Table 3 for age and probability estimates of the inferred dispersals.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of the 14 dispersal events detected in the Hippophae nDNA phylogeny using Bayesian dispersal-vicariance analysis implemented in RASP.

| Dispersal events | AAR of parent node |

AAR of daughter node |

Age of parent node (Ma) |

Age of daughter node (Ma) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MP | 2 | MP | 1 | MP | 2 | MP | Mean | 95% HPD | Mean | 95% HPD | |

| a | A | (58.7) | B | (27.1) | B | (65.3) | A | (16.9) | 22.9 | (17.1–28.4) | 18.9 | (13.7–24.5) |

| b | B | (65.3) | A | (16.9) | C | (53.0) | A | (20.8) | 18.9 | (13.7–24.5) | 6.6 | (2.3–11.9) |

| c | A | (78.5) | AB | (7.6) | B | (41.7) | C | (30.3) | 11.6 | (6.1–17.7) | 2.9 | (0.8–5.7) |

| d | B | (58.3) | E | (25.6) | E | (84.5) | BE | (11.2) | 10.2 | (8.0–12.6) | 1.1 | (0.1–2.7) |

| D | (61.1) | < 5% | – | 7.9 | (7.2–8.9) | |||||||

| e | D | (61.1) | < 5% | – | I | (45.5) | G | (36.2) | 7.9 | (7.2–8.9) | 5.3 | (3.1–7.6) |

| f | I | (45.5) | G | (36.2) | G | (96.7) | <5% | – | 5.3 | (3.1–7.6) | 2.2 | (0.5–4.0) |

| g | C | (53.0) | A | (20.8) | A | (49.2) | D | (33.0) | 6.6 | (2.3–11.9) | 3.6 | (0.9–7.4) |

| h | G | (90.2) | GH | (5.9) | H | (94.7) | <5% | – | 1.5 | (0.3–3.1) | 0.9 | (0.04–2.1) |

| i | D | (95.4) | <5% | – | F | (93.5) | DF | (5.5) | 1.3 | (0.2–2.7) | 0.4 | (0.01–1.1) |

| j | A | (49.2) | D | (33.0) | D | – | – | – | 3.6 | (0.9–7.4) | 0 | 0 |

| k | E | (71.7) | BE | (17.8) | B | – | – | – | 0.3 | (0–0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| l | B | (38.6) | C | (36.0) | C | (96.2) | <5% | – | 1.8 | (0.4–3.7) | 0.4 | (0–1.2) |

| m | B | (45.4) | BC | (30.3) | C | – | – | – | 1.3 | (0.1–2.8) | 0 | 0 |

| n | A | (81.6) | AD | (9.1) | D | (96.9) | <5% | – | 2.3 | (0.2–5.5) | 0.4 | (0–1.4) |

Dispersal numbers and area codes refer to Figure 5. For ancestral area reconstructions (AAR), the first two areas with the highest marginal probability (MP; in percent) are reported for both the parent and daughter nodes of each dispersal event. Age estimates are derived from Bayesian relaxed clock analysis treating priors on fossils as being drawn from a lognormal distribution. The mean date in million years ago and the 95% highest posterior density intervals are given for each parent and daughter node.

Discussion

Divergence Ages Within Elaeagnaceae

Our results provided the first estimates for the stem and crown nodes of Elaeagnaceae (mean ages were estimated as 89.3 and 40.6 Ma, respectively). We note that the oldest known fossil of Elaeagnaceae (pollen of Elaeagnacites sp.) is from the Taizhou Formation in North Jiangsu Basin (Song and Qian, 1989), which in China corresponds to the Maastrichtian (Song et al., 2004). Our age estimate for this family thus predates its earliest known fossil record by some 20–30 Myr, indicating a considerable gap in the fossil record, similar to many other families of angiosperms (Crepet et al., 2004).

Phylogenetic Relationships Among Species of Hippophae

We reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships of Hippophae based on thorough sampling across lineages/distribution ranges and a relatively large amount of sequence data of both cpDNA and nuclear DNA. The genus was strongly supported as monophyletic and can be divided into two distinct sub-clades: one comprising H. rhamnoides and H. tibetana and the other comprising H. gyantsensis, H. neurocarpa, and H. salicifolia (Figures 2, 3). The relationship between H. rhamnoides and H. tibetana was uncertain in earlier studies (Bartish et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2002; Jia et al., 2011). However, it received a strong Bayesian (PP = 1.00) and moderate ML bootstrap (BP > 84%) support in both phylogenies. The relationships among the three species within the other sub-clade are still poorly resolved in the cpDNA phylogeny and incongruent between the two data sets. This could probably result from the homoploid hybridizations between species falling into the two sub-clades, i.e., H. neurocarpa and H. rhamnoides, as indicated by our previous work based on population genetic data and niche modeling (Jia et al., 2016).

Biogeographical Patterns in Hippophae

Early Diversification in Hippophae (Stage I)

The south QTP (the central Himalaya and southern Tibet) was suggested as the ancestral area of the genus in our reconstructions (Figures 4, 5). Early diversification within the genus most likely started in this region in the late Oligocene/early Miocene. This placement in time and space corresponds to the uplift-stage C of the QTP occurring at 25–20 Ma (Zhang et al., 2013). Reports from dated molecular phylogenies of plant taxa indicated additional cases of initial diversification in the south or east QTP at this period or soon after in Androsace (Roquet et al., 2013) and Lepisorus (Wang et al., 2012). It is tempting to link the earliest diversification in Hippophae and the other genera mentioned above with the rise of the southern QTP in the early Miocene. Nonetheless, we note that reconstruction of ages and paleoaltitudes of the QTP uplifts is still a controversial area of research (Harris, 2006; Molnar et al., 2010). For example, the central QTP has been argued to be already near its present elevation at least 40 Ma (Rowley and Currie, 2006; DeCelles et al., 2007; Wang C. et al., 2008), at least 15 Ma (Spicer et al., 2003), or no older than 2–3 Ma (Wang Y. et al., 2008). Only when this controversy has been resolved and robust models for early orogeneses of the QTP have been developed, can linking geological and biogeographical events around this plateau in the Paleogene and early Neogene be meaningful.

Diversification and Expansion of H. rhamnoides (Stage II)

After a period of initial diversification in the central Himalaya/southern QTP in the early to middle Miocene and differentiation of all species, diversification in the genus likely shifted to the eastern QTP (Figures 4, 5). This area was inferred as the ancestral area of H. rhamnoides and several oldest lineages of this species are distributed there. As indicated by our RASP analysis (Figures 4, 5), differentiation of a common ancestor of ssp. sinensis and turkestanica was followed by a dispersal event across the QTP in the earliest late Miocene (the Tortonian age) and an extinction event in the ancestral area of ssp. turkestanica. These events might be associated with uplift of the western QTP (Zhang et al., 2013) and concomitant paleoclimatic changes in the area, such as advance of more open and arid environments across the QTP (Tang and Shen, 1996; Hui et al., 2011).

Unlike in the early Neogene, links among paleoecology, climatic shifts, and orogeneses in the late Neogene (the last 10 Ma) are relatively well-studied. Considerable climatic and landscape modifications in area between the west QTP and Europe in the late Miocene have been indicated by geological (Ramstein et al., 1997; Trifonov et al., 2012), paleozoological (Koufos et al., 2005; Fortelius et al., 2006; Eronen et al., 2009), and paleobotanical (Mosbrugger et al., 2005; Kovar-Eder et al., 2008) data. These processes were coincident with ecosystem turnovers of this age in the area: degradation of tropical and subtropical laurophyllous forests, expansion of warm temperate sclerophyllous woodlands, scrubs, and savannas (Mosbrugger et al., 2005; Kovar-Eder et al., 2008; Biltekin, 2010), and expansion of grasses (Strömberg et al., 2007). Reconstructions of evolution of bovid and Hipparion megafauna (Barry et al., 1995; Fortelius et al., 2006; Eronen et al., 2009; Liu L. et al., 2012) and contemporary turnovers in small mammalian fauna (Mein, 2003; Maridet et al., 2007) across central parts of Eurasia provided a detailed evidence for these ecological and evolutionary processes in the late Miocene. Our results indicated that H. rhamnoides was involved in these processes. After dispersal to the west QTP, this species expanded across Karakoram, Hindu Kush, Pamir, and Tianshan, giving rise to extant ssp. turkestanica. Orogeneses during that geological epoch resulted in relatively close positioning of the western ranges of Hindu Kush, Kopet Dag, Elburz, and Caucasus (Trifonov et al., 2012). Their orientation created more or less a continuous belt of mountain ranges, which thus served as an ecological bridge between highland habitats in Central Asia, Anatolia, and Balkans. After differentiation within the ancestral area of the clade of Asia Minor/European subspecies in the west QTP, one or two of the diverged lineages could use this ecological opportunity for westward expansion. Our age estimates of the putative dispersals followed by local extinctions corresponded to a period of considerable orogenic, climatic, and ecological modifications in the Central Asia, eastern Anatolia, and eastern Europe (Mosbrugger et al., 2005; Fortelius et al., 2006; Trifonov et al., 2012). Taken together, our results implicated that H. rhamnoides originated in the middle Miocene in the east QTP and reached the west Europe in three long-distance dispersals in the late Miocene (Figures 4, 5). The main trigger of these dispersals seems to be arising of a relatively continuous belt of mountain ranges west of the QTP and opening of landscape through deforestation of these areas. Ecological and physiological characteristics of the species (see Introduction) allow it an efficient colonization of mountain landscapes and survival in these unstable ecosystems. Although H. rhamnoides is easily outcompeted from stable lowland forested ecosystems, this species can become dominant in ruderal and mostly arid ecosystems of mountain slopes and valleys (Igor V. Bartish, personal observations during field trips across Caucasus, Central Asia, Himalayas, and southern Siberia in 2012–2014).

Apart from Hippophae, other plants with ecological niches in open landscapes and relatively dry and cold climates have also been shown to disperse westwards out of the QTP at this period by molecular phylogenetic analyses, e.g., Lilium (Gao et al., 2013) and Saussurea (Wang Y.J. et al., 2009). We suggest additional molecular phylogenetic studies focusing on clades with Eurasian ranges and putative ancestral areas in the QTP and using dating and dispersal-vicariance analyses should be carried out to test the generality of this migration route in the late Miocene. For example, one can test the hypothesis of Bobrov (1962) that ancestors of M. germanica (L.) Desv., which currently shares with H. rhamnoides similar ranges and ecological niches, could have migrated to Europe from Central Asia taking the same route in the same geological epoch. On the other hand, testing directions and comparing ages of migrations across Eurasia of representatives of different ecological groups can lead to deeper insights into mechanisms of biotic turnovers on the continent.

Diversification and Dispersals Within Taxa (Stage III)

Our dating analyses revealed an interesting pattern: regardless of the age of each taxon, differentiation within all taxa (except the paraphyletic ssp. yunnanensis) was largely temporally coincident and relatively recent, in the late Pliocene/Pleistocene (Figures 4, 5 and Supplementary Tables S8, S9). Specifically, results of our dating and ancestral area reconstructions from cpDNA (Figure 4) suggested two dispersal/vicariance events within taxa in the Pliocene: from the southern to north-eastern QTP in H. tibetana (dispersal 9) and from the eastern QTP to the Mongolian Plateau in H. rhamnoides (ssp. sinensis/yunnanensis clade and ssp. mongolica; dispersal 7). We note that both dispersals were in a northward direction. Three more northward dispersals from the eastern QTP, followed by vicariance, were inferred lately in the Pleistocene: one to northern China (ssp. sinensis, dispersal 8), and the other two to the northern QTP (H. neurocarpa ssp. neurocarpa and stellatopilosa; dispersals 12 and 13, respectively). Finally, our results suggested two almost coincident westward dispersals in the late Pliocene/early Pleistocene along opposite slopes of the Himalayas: northern slopes in H. tibetana (dispersal 10) and southern slopes in H. salicifolia (dispersal 11). The pattern of coincident biogeographical events in Hippophae in the Pliocene and Pleistocene with similar directions of dispersals (mostly from south to north) within different regions of the QTP is conspicuous. Noteworthy, this pattern was also found in European subspecies of H. rhamnoides in the Late Quaternary (Bartish et al., 2006). A growing number of molecular studies suggest diversifications within species and dispersals across or around the QTP at this period (for recent reviews, see Qiu et al., 2011; Liu J.Q. et al., 2012). Results of our study, together with the earlier reports, indicate a strong impact of the last stage of the QTP uplift since 5 Ma (Zhang et al., 2013) and concomitant climatic fluctuations on evolutionary processes in this hot spot of biodiversity (Myers et al., 2000; Mittermeier et al., 2005). It is likely that species responded to geological and climatic changes around the QTP by range expansions and fragmentations, long-distance dispersals, and local extinctions. General trends of these responses within different ecological groups of plants are still poorly known, but they likely depend on ecological characteristics of particular lineages. Spatial and temporal resolution of analyses on taxa with their highest diversity in the QTP area are increasing fast. These efforts will undoubtedly provide new insights into mechanisms of evolutionary responses of species with different ecological characteristics to climatic and geological processes in the late Neogene/Quaternary of Eurasia.

Conclusion

Taxa with Eurasian ranges, centers of diversity around the QTP and different ecological characteristics can represent useful model systems to study the mechanisms of biotic responses to climatic fluctuations and orogeneses on the continent. However, few of these taxa have been included into comprehensive biogeographical analyses using ancestral area reconstructions and molecular dating, preventing development of a general understanding of the detailed mechanisms. In present study, we integrated phylogenetic, molecular dating, and biogeographical methods to reconstruct the evolutionary history of Hippophae, a pioneer plant with an extremely wide range of climatic niches in Eurasia and the highest intra-generic diversity around the QTP. Our results supported an old biogeographical hypothesis and suggested that multiple dispersals should have contributed to the observed biogeographical patterns of Hippophae. These dispersals can be grouped into three stages: (i) dispersals from ancestral area of the genus in the south QTP to the east QTP in the early Miocene; (ii) long-distance dispersals from the east QTP to Europe along rising mountain systems across Eurasia in the late Miocene; and (iii) mostly intraspecific northward and westward dispersals around the QTP and other mountain ranges in the Pliocene/Pleistocene. Additionally, at least three cases of possible extinctions were inferred in different parts of the QTP. We argue that biotic responses to environmental changes in the Neogene/Quaternary of Eurasia can depend on ecological characteristics of evolutionary lineages and result in different biogeographical patterns. To advance our understanding of mechanisms of association between paleoclimatic and macro-evolutionary processes, further studies should focus on comparison of evolutionary histories of lineages from ecologically and geographically similar groups.

Author Contributions

D-RJ and IB conceived the ideas. D-RJ collected and analyzed the data. D-RJ and IB wrote the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

D-RJ was supported by the China Scholarship Council. IB was supported by the J. E. Purkynĕ Fellowship of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. Alexey Kudrin Foundation is greatly acknowledged for financial support of this study. We are grateful to Jan Kirschner for his support at the early stages of this study. We thank J-Q. Liu, S. Raina, A. Borisyuk, I. Schanzer, P. Mladin, A. Ford, F. Verloove, J. Klakenberg, L. Stenberg, M. Kucuk, M. Rabadanov, P. Sekerka, R. Maan, and Y-M. Yuan for providing samples.

Funding. This study was co-supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31560112) and Alexey Kudrin Foundation.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01400/full#supplementary-material

References

- Akaike H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 19 716–723. 10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An Z., Kutzbach J. E., Prell W. L., Porter S. C. (2001). Evolution of Asian monsoons and phased uplift of the Himalaya–Tibetan plateau since Late Miocene times. Nature 411 62–66. 10.1038/35075035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D. I., Al S. I., Raven P. H. (1996). “History of the modern flora of China,” in Floristic characteristics and diversity of East Asian plants eds Zhang A. L., Wu S. G. (Berlin: Springer; ) 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Barry J. C., Morgan M. E., Flynn L. J., Pilbeam D., Jacobs L. L., Lindsay E. H., et al. (1995). Patterns of faunal turnover and diversity in the Neogene Siwaliks of northern Pakistan. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 115 209–226. 10.1016/0031-0182(94)00112-L [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartish I. V. (2016). “An ancient medicinal plant at the crossroads of modern horticulture and genetics: genetic resources and biotechnology of sea buckthorn (Hippophae L., Elaeagnaceae),” in Gene Pool Diversity and Crop Improvement, Sustainable Development and Biodiversity eds Rajpal V., Rao S., Raina S. (Cham: Springer; ) 415–446. 10.1007/978-3-319-27096-8_14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartish I. V., Jeppsson N., Bartish G. I., Lu R., Nybom H. (2000). Inter- and intraspecific genetic variation in Hippophae (Elaeagnaceae) investigated by RAPD markers. Plant Systemat. Evol. 225 85–101. 10.1007/BF00985460 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartish I. V., Jeppsson N., Nybom H., Swenson U. (2002). Phylogeny of Hippophae (Elaeagnaceae) inferred from parsimony analysis of chloroplast DNA and morphology. Systemat. Bot. 27 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bartish I. V., Kadereit J. W., Comes H. P. (2006). Late Quaternary history of Hippophae rhamnoides L. (Elaeagnaceae) inferred from chalcone synthase intron (Chsi) sequences and chloroplast DNA variation. Mol. Ecol. 15 4065–4083. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03079.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartish I. V., Swenson U. (2004). “Elaeagnaceae,” in The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants ed. Kubitzki K. (Berlin: Springer; ) 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Becker H. F. (1960). The tertiary mormon creek flora from the upper ruby river basin in southwestern Montana. Palaeontogr. Abt. B 107 83–126. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren W. A., Van Couvering J. A. (1974). The Late Neogene: Biostratigraphy, Geochronology, and Paleoclimatology of the Last 15 Million Years in Marine And Continental Sequences. eds Berggren W. A., Van Couvering J. A. (New York, NY: Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company; ). [Google Scholar]

- Biltekin D. (2010). Vegetation and Climate of North Anatolian and North Aegean Region Since 7 Ma According to Pollen Analysis. Ph D. thesis, Université Claude Bernard-Lyon I; Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrov E. G. (1962). Obzor roda Myricaria Desv. i jego istorija. Botanicheskij Zhurnal 52 924–936. [Google Scholar]

- Bond G., MacConnell J., McCallum A. (1956). The nitrogen-nutrition of Hippophaë rhamnoides L. Ann. Bot. 20 501–512. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a083539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burge D. O., Manchester S. R. (2008). Fruit morphology, fossil history, and biogeography of Paliurus (Rhamnaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 169 1066–1085. 10.1086/590453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M. E. J. (1962). The Lower Tertiary Floras of Southern England. II. Flora of the Pipe-Clay Series of Dorset (Lower Bagshot). London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Comes H. P., Kadereit J. W. (2003). Spatial and temporal patterns in the evolution of the flora of the European Alpine system. Taxon 52 451–462. 10.2307/3647445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crepet W. L., Nixon K. C., Gandolfo M. A. (2004). Fossil evidence and phylogeny: the age of major angiosperm clades based on mesofossil and macrofossil evidence from Cretaceous deposits. Am. J. Bot. 91 1666–1682. 10.3732/ajb.91.10.1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D., Taboada G. L., Doallo R., Posada D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9 772–772. 10.1038/nmeth.2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCelles P. G., Kapp P., Ding L., Gehrels G. (2007). Late Cretaceous to middle Tertiary basin evolution in the central Tibetan Plateau: changing environments in response to tectonic partitioning, aridification, and regional elevation gain. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 119 654–680. 10.1130/B26074.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Suchard M. A., Xie D., Rambaut A. (2012). Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29 1969–1973. 10.1093/molbev/mss075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eronen J. T., Ataabadi M. M., Micheels A., Karme A., Bernor R. L., Fortelius M. (2009). Distribution history and climatic controls of the Late Miocene Pikermian chronofauna. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 11867–11871. 10.1073/pnas.0902598106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortelius M., Eronen J., Liu L., Pushkina D., Tesakov A., Vislobokova I., et al. (2006). Late Miocene and Pliocene large land mammals and climatic changes in Eurasia. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 238 219–227. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.03.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. D., Harris A. J., Zhou S. D., He X. J. (2013). Evolutionary events in Lilium (including Nomocharis, Liliaceae) are temporally correlated with orogenies of the Q-T plateau and the Hengduan Mountains. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 68 443–460. 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Ruddiman W. F., Hao Q., Wu H., Qiao Y., Zhu R. X., et al. (2002). Onset of Asian desertification by 22 Myr ago inferred from loess deposits in China. Nature 416 159–163. 10.1038/416159a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris N. (2006). The elevation history of the Tibetan Plateau and its implications for the Asian monsoon. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 241 4–15. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt G. M. (2004). Genetic consequences of climatic oscillations in the Quaternary. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 359 183–195. 10.1098/rstb.2003.1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui Z., Li J., Xu Q., Song C., Zhang J., Wu F., et al. (2011). Miocene vegetation and climatic changes reconstructed from a sporopollen record of the Tianshui Basin, NE Tibetan Plateau. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 308 373–382. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.05.043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvönen J. (1996). On phylogeny of Hippophae (Elaeagnaceae). Nord. J. Bot. 16 51–62. 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1996.tb00214.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. B., Simmons M. P. (2006). A thorny dilemma: testing alternative intrageneric classifications within Ziziphus (Rhamnaceae). Syst. Bot. 31 826–842. 10.1600/036364406779695997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D. R., Abbott R. J., Liu T. L., Mao K. S., Bartish I. V., Liu J. Q. (2012). Out of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau: evidence for the origin and dispersal of Eurasian temperate plants from a phylogeographic study of Hippophaë rhamnoides (Elaeagnaceae). New Phytol. 194 1123–1133. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D. R., Liu T. L., Wang L. Y., Zhou D. W., Liu J. Q. (2011). Evolutionary history of an alpine shrub Hippophae tibetana (Elaeagnaceae): allopatric divergence and regional expansion. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 102 37–50. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2010.01553.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D. R., Wang Y. J., Liu T. L., Wu G. L., Kou Y. X., Cheng K., et al. (2016). Diploid hybrid origin of Hippophae gyantsensis (Elaeagnaceae) in the western Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 117 658–671. 10.1111/bij.12707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit J. W., Licht W., Uhink C. H. (2008). Asian relationships of the flora of the European Alps. Plant Ecol. Divers. 1 171–179. 10.1080/17550870802328751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kou Y. X., Wu Y. X., Wang Y. J., Jia D. R., Li Z. H. (2013). Range expansion, genetic differentiation, and phenotypic adaption of Hippophaë neurocarpa (Elaeagnaceae) on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. J. Syst. Evol. 10.1111/jse.12063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koufos G. D., Kostopoulos D. S., Vlachou T. D. (2005). Neogene/Quaternary mammalian migrations in eastern Mediterranean. Belg. J. Zool. 135 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kovar-Eder J., Jechorek H., KvačEk Z., Parashiv V. (2008). The integrated plant record: an essential tool for reconstructing Neogene zonal vegetation in Europe. Palaios 23 97–111. 10.2110/palo.2006.p06-039r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang G. (1994). Quartäre Vegetationsgeschichte Europas. Jena: Gustav Fischer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P. O. (2001). A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst. Biol. 50 913–925. 10.1080/106351501753462876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. J., Fang X. M., Pan B. T., Zhao Z. J., Song Y. G. (2001). Late cenozoic intensive uplift of Qinghai-Xizang Plateau and its impacts on environments in surrounding area. Quat. Sci. 21 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Lian Y. S., Chen X. L., Lian H. (1998). Systematic classification of the genus Hippophae L. Seabuckthorn Res. 1 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lielke K., Manchester S., Meyer H. (2012). Reconstructing the environment of the northern Rocky Mountains during the Eocene/Oligocene transition: constraints from the palaeobotany and geology of south-western Montana, USA. Acta Palaeobot. 52 317–358. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Q., Sun Y. S., Ge X. J., Gao L. M., Qiu Y. X. (2012). Phylogeographic studies of plants in China: Advances in the past and directions in the future. J. Syst. Evol. 50 267–275. 10.1111/j.1759-6831.2012.00214.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Puolamäki K., Eronen J. T., Ataabadi M. M., Hernesniemi E., Fortelius M. (2012). Dental functional traits of mammals resolve productivity in terrestrial ecosystems past and present. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279 2793–2799. 10.1098/rspb.2012.0211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Pujol J., Zhang F. M., Sun H. Q., Ying T. S., Ge S. (2011). Centres of plant endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? J. Biogeogr. 38 1267–1280. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02504.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manchester S. R., Akhmetiev M. A., Kodrul T. M. (2002). Leaves and fruits of Celtis aspera (Newberry) comb. nov.(Celtidaceae) from the Paleocene of North America and eastern Asia. Int. J. Plant Sci. 163 725–736. 10.1086/341513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maridet O., Escarguel G., Costeur L., Mein P., Hugueney M., Legendre S. (2007). Small mammal (rodents and lagomorphs) European biogeography from the Late Oligocene to the mid Pliocene. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 16 529–544. 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00306.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mein P. (2003). On Neogene rodents of Eurasia: distribution and migrations. Deinsea 10 407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Melinte-Dobrinescu M. C., Suc J. P., Clauzon G., Popescu S. M., Armijo R., Meyer B., et al. (2009). The Messinian Salinity Crisis in the Dardanelles region: chronostratigraphic constraints. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 278 24–39. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier R. A., Gil P. R., Hoffman M., Pilgrim J., Brooks T., Mittermeier C. G., et al. (2005). Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. Monterrey: Cemex. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar P. (2005). Mio-Pliocene growth of the Tibetan Plateau and evolution of East Asian climate. Palaeontol. Electron. 8 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar P., Boos W. R., Battisti D. S. (2010). Orographic controls on climate and paleoclimate of Asia: thermal and mechanical roles for the Tibetan Plateau. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 38 77–102. 10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbrugger V., Utescher T., Dilcher D. L. (2005). Cenozoic continental climatic evolution of Central Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 14964–14969. 10.1073/pnas.0505267102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J. (1968). Palynology of the Pedawan and plateau sandstone formations (Cretaceous-Eocene) in Sarawak, Malaysia. Micropaleontology 14 1–37. 10.2307/1484763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J. (1981). Fossil pollen records of extant angiosperms. Bot. Rev. 47 1–142. 10.1007/BF02860537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers N., Mittermeier R. A., Mittermeier C. G., Da Fonseca G. A., Kent J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403 853–858. 10.1038/35002501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y.-X., Fu C.-X., Comes H. P. (2011). Plant molecular phylogeography in China and adjacent regions: Tracing the genetic imprints of Quaternary climate and environmental change in the world’s most diverse temperate flora. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 59 225–244. 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A., Drummond A. J. (2007). Tracer v 1.5. Available at: http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer [Google Scholar]

- Ramstein G., Fluteau F., Besse J., Joussaume S. (1997). Effect of orogeny, plate motion and land-sea distribution on Eurasian climate change over the past 30 million years. Nature 386 788–795. 10.1038/386788a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. E., Fay M. F., Cronk Q. C. B., Chase M. W. (2000). A revision of the tribal classification of Rhamnaceae. Kew Bull. 55 311–340. 10.2307/4115645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roquet C., Boucher F. C., Thuiller W., Lavergne S. (2013). Replicated radiations of the alpine genus Androsace (Primulaceae) driven by range expansion and convergent key innovations. J. Biogeogr. 40 1874–1886. 10.1111/jbi.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousi A. (1971). The genus Hippophae L. A taxonomic study. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 8 177–227. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley D. B., Currie B. S. (2006). Palaeo-altimetry of the late Eocene to Miocene Lunpola basin, central Tibet. Nature 439 677–681. 10.1038/nature04506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M. J. (2002). Estimating absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times: a penalized likelihood approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 101–109. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson M. J. (2003). r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 19 301–302. 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauquet H., Ho S. Y., Gandolfo M. A., Jordan G. J., Wilf P., Cantrill D. J., et al. (2012). Testing the impact of calibration on molecular divergence times using a fossil-rich group: the case of Nothofagus (Fagales). Syst. Biol. 61 289–313. 10.1093/sysbio/syr116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z. C., Qian Z. S. (1989). “Palynological study of Taizhou Formation in North Jiangsu Basin,” in Stratigraphy and Palaeontology of the Taizhou Formation and the First member of the Funing Formation, North Jiangsu Basin eds Institute of Geology-Jiangsu Oil Exploration and Development Corporation & Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology-Academia Sinica. (Nanjing, China: Nanjing University Press; ) 33–109. [Google Scholar]

- Song Z. C., Wang W. M., Huang F. (2004). Fossil pollen records of extant angiosperms in China. Bot. Rev. 70 425–458. 10.1663/0006-8101(2004)070[0425:FPROEA]2.0.CO;2 23360930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsa P. (1971). Pollen morphological study of the genus Hippophae L., including the new taxa recognised by A. Rousi. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 8 228–236. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer R. A., Harris N. B., Widdowson M., Herman A. B., Guo S., Valdes P. J., et al. (2003). Constant elevation of southern Tibet over the past 15 million years. Nature 421 622–624. 10.1038/nature01356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22 2688–2690. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A., Hoover P., Rougemont J. (2008). A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst. Biol. 57 758–771. 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strömberg C. A., Werdelin L., Friis E. M., Saraç G. (2007). The spread of grass-dominated habitats in Turkey and surrounding areas during the Cenozoic: phytolith evidence. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 250 18–49. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K., Chen X., Ma R., Li C., Wang Q., Ge S. (2002). Molecular phylogenetics of Hippophae L. (Elaeagnaceae) based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences of nrDNA. Plant Syst. Evol. 235 121–134. 10.1007/s00606-002-0206-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson U., Bartish I. V. (2002). Taxonomic synopsis of Hippophae (Elaeagnaceae). Nord. J. Bot. 22 369–374. 10.1111/j.1756-1051.2002.tb01386.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takhtajan A. (1986). Floristic Regions of the World. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007). MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 1596–1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L., Shen C. (1996). Late Cenozoic vegetational history and climatic characteristics of Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Acta Micropalaeontol. Sin. 13 321–337. [Google Scholar]

- Tian C., He X., Zhong Y., Chen J. (2002). Effects of VA mycorrhizae and Frankia dual inoculation on growth and nitrogen fixation of Hippophae tibetana. For. Ecol. Manag. 170 307–312. 10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00781-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trifonov V. G., Ivanova T. P., Bachmanov D. M. (2012). Recent mountain building of the central Alpine-Himalayan Belt. Geotectonics 46 315–332. 10.1134/s0016852112050068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zhao X., Liu Z., Lippert P. C., Graham S. A., Coe R. S., et al. (2008). Constraints on the early uplift history of the Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 4987–4992. 10.1073/pnas.0703595105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Moore M. J., Soltis P. S., Bell C. D., Brockington S. F., Alexandre R., et al. (2009). Rosid radiation and the rapid rise of angiosperm-dominated forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 3853–3858. 10.1073/pnas.0813376106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Qiong L., Sun K., Lu F., Wang Y. G., Song Z. P., et al. (2010). Phylogeographic structure of Hippophae tibetana (Elaeagnaceae) highlights the highest microrefugia and the rapid uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Mol. Ecol. 19 2964–2979. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04729.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Schneider H., Zhang X. C., Xiang Q. P. (2012). The rise of the Himalaya enforced the diversification of SE Asian ferns by altering the monsoon regimes. BMC Plant Biol. 12:210. 10.1186/1471-2229-12-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang X., Xu Y., Zhang C., Li Q., Tseng Z. J., et al. (2008). Stable isotopes in fossil mammals, fish and shells from Kunlun Pass Basin, Tibetan Plateau: paleo-climatic and paleo-elevation implications. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 270 73–85. 10.1016/j.epsl.2008.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. J., Susanna A., Von Raab-Straube E., Milne R., Liu J. Q. (2009). Island-like radiation of Saussurea (Asteraceae: Cardueae) triggered by uplifts of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 97 893–903. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01225.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Y., Sun H., Zhou Z. K., Li D. Z., Peng H. (2011). Floristics of Seed Plants from China. Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wulff E. V. (1943). An Introduction to Historical Plant Geography. Waltham, MA: Chronica Botanica Company. [Google Scholar]

- Young N. D., Healy J. (2003). GapCoder automates the use of indel characters in phylogenetic analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 4:6. 10.1186/1471-2105-4-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Harris A. J., Blair C., He X. J. (2015). RASP (Reconstruct Ancestral State in Phylogenies): A tool for historical biogeography. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 87 46–49. 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Wang G., Xu Y., Luo M., Ji J., Xiao G., et al. (2013). Sedimentary evolution of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau in Cenozoic and its Response to the Uplift of the Plateau. Acta Geol. Sin. 87 555–575. 10.1111/1755-6724.12068 26666501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. D., Soltis D. E., Yang Y., Li D. Z., Yi T. S. (2011). Multi-gene analysis provides a well-supported phylogeny of Rosales. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 60 21–28. 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. L., Wang Y. J., Ge X. J., Yuan Y. M., Yang H. L., Liu J. Q. (2009). Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of Gentiana sect. Cruciata (Gentianaceae) based on four chloroplast DNA datasets. Taxon 58 862–870. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Powell C. M., An Z., Zhou J., Dong G. (2000). Pliocene uplift of the northern Tibetan Plateau. Geology 28 715–718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.