Abstract

Brachytherapy with 106Ru eye plaques is the most common treatment modality for small to medium-sized uveal melanomas in Europe. So far, no standardized or widely accepted dose prescription protocol for the irradiation of intraocular tumors with 106Ru eye plaques has been defined. For 125I plaques, the minimum dose required for tumor control should be at least 85 Gy. Concerning 106Ru plaques, the dose prescriptions at the University Hospital of Essen foresees minimum doses of 700 Gy to the tumor base and 130 Gy to the tumor apex. These dose prescriptions are expected to ensure sufficient treatment margins. We apply these dose prescriptions to different eye plaque types and tumor sizes and discuss the resulting treatment margins. These investigations are based on Monte Carlo simulations of dose distributions of 3 different eye plaque types. The treatment margin in apical direction has an expansion of at least 0.8 mm for all investigated eye plaques. For symmetrically formed eye plaques, the treatment margin at the base of the tumor goes beyond the visible edge of the plaque. This study focuses on the shape of 85-Gy isodose lines and on treatment margins for different eye plaque types and tumor sizes and shall help exchange knowledge for ocular brachytherapy.

Keywords: Brachytherapy, Ruthenium, Eye plaque, Treatment planning, Treatment margin, Dosimetry, Uveal melanoma

Introduction

For treatment of small to medium-sized uveal melanomas (tumor thickness of up to 6 mm), brachytherapy with 106Ru eye plaques is the most common treatment modality in Europe [1]. In experienced centers, the local tumor control rate reaches over 90% [2]. To prevent therapy failure, accurate treatment planning is necessary. In general, there is no widely accepted dose prescription protocol, only dose recommendations are given [3, 4]. In the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) using 125I eye plaques, a mandated minimum dose of 85 Gy was specified [3, 5]. Hence, for 106Ru eye plaques, we have assumed the same minimum dose of 85 Gy to be applied to the entire target volume. This model, however, does not take into consideration the much steeper gradient of the progression of the isodose curves for 106Ru.

The gross tumor volume (GTV) corresponds to the macroscopic tumor dimensions, which are defined by findings from sonography, ophthalmoscopy, and the tumor's transillumination shadow. For the definition of the clinical target volume (CTV), the sclera thickness is added in apical direction and a margin of 1–2 mm is added in all directions to the tumor base diameter [6]. There are several uncertainties which have to be considered, such as dosimetric uncertainties [7], impreciseness of the determination of the tumor height [8, 9, 10, 11], and positioning inaccuracies [12, 13]. For this reason, an additional radiation therapy treatment margin (or safety margin) has to be added to the defined CTV. For ocular brachytherapy, currently the only recommended margin is an overall basal margin of 2–3 mm. Following this recommendation, eye plaques with a diameter larger than the maximal tumor base dimension are chosen. There are no requirements for the size of the apex margin [14]. By simply adding a margin to the CTV, it is not exactly defined a priori where the 85-Gy isodose line is located. Among other things, it depends on the prescribed dose and the shape and the size of the chosen eye plaque. Until now, no visualization of the 3-D shape of treatment margins was published. Therefore, on the base of an eye model, we want to present treatment margins resulting from the dose prescriptions established at the University Hospital of Essen.

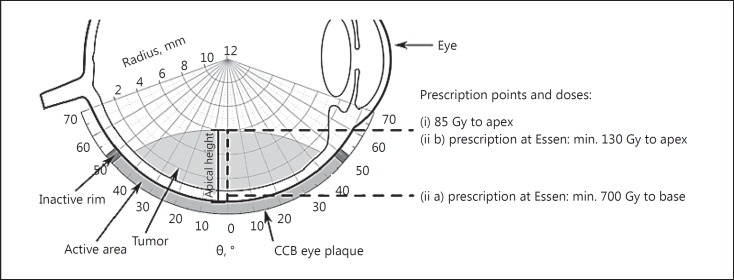

At the University Hospital of Essen, the prescribed dose to the tumor apex is at least 130 Gy. Additionally, a minimum dose of 700 Gy to the base is required (Fig. 1). A restraint is given by a maximal sclera dose of 1,500 Gy [15], which is taken into account for all considerations in this study. These dose prescriptions (ii) are expected to ensure sufficient treatment margins at the base and apex of the tumor for different tumor thicknesses and plaque sizes. It should be noted that the dose calculations are only executed along the central depth dose profile. The goal of this concept is to attain tumor control considering the mentioned uncertainties while simultaneously saving as much healthy tissue as possible, independent from tumor heights and plaque sizes.

Fig. 1.

General setup with the 2 marked prescription points and dose prescriptions (CCB eye plaque type as an example). Θ in ° describes the opening angle, and the radius in mm can be understood as the distance from the surface of the eye plaque. The distance between the plaque surface and the tumor apex is marked as the apical height.

The determination of 3-D dose distributions is a current field of research [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. This study is based on Monte Carlo simulated dose distributions of 3 eye plaque types. Our aim is to raise awareness of the location of the 85-Gy isodose line with regard to the eye plaque type and the prescribed dose and discuss resulting treatment margins.

Materials and Methods

Eye Plaques

The manufacturer BEBIG offers a variety of eye plaques with the same basic design but different sizes and shapes [25]. The plaques are molded to form a calotte and consist of 3 layers: a convex silver backing with a thickness of 0.7 mm, a concave silver window with a thickness of 0.1 mm, and a 0.2-mm-thick silver target, which is electrochemically coated with the radioactive 106Ru in contact with the silver window. All plaques have an inactive rim with a minimum width of 0.75 mm. At the rim, 2 or more eyelets are placed to suture the plaque to the sclera. The eye plaques considered in this study have a radius of curvature of 12 mm, but different diameters at the base of the calotte, namely 21.5 mm for the CCB and 11.5 mm for the CCX. The COB is a notched plaque for treating tumors close to or beyond the optic nerve. A sketch of the investigated eye plaques in top view can be seen in Figures 2 and 3. More exact descriptions and illustrations of the different eye plaque types can be found in [7, 26].

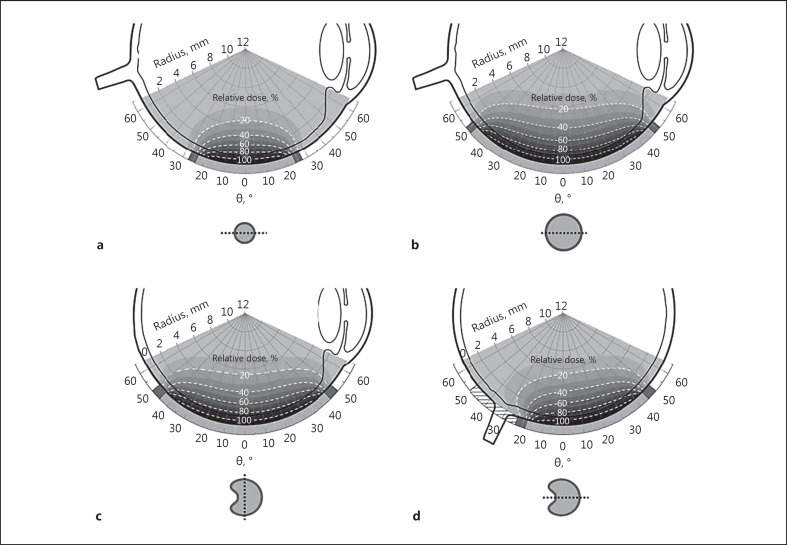

Fig. 2.

Section planes of dose distributions inside the eye of CCX eye plaque (a), CCB eye plaque (b), COB eye plaque perpendicular to the cutout (c), and COB eye plaque through the cutout (d; hatched area symbolizes the cutout). The dose values are given in relative dose in % and are standardized to 100% at a distance of 0.5 mm on the central axis, which takes the thickness of the sclera into account. Isodose lines are illustrated as dashed lines by steps of 20% and the gray scales change with an increment of 10%. The section planes of the different eye plaques are marked with dotted lines in top view.

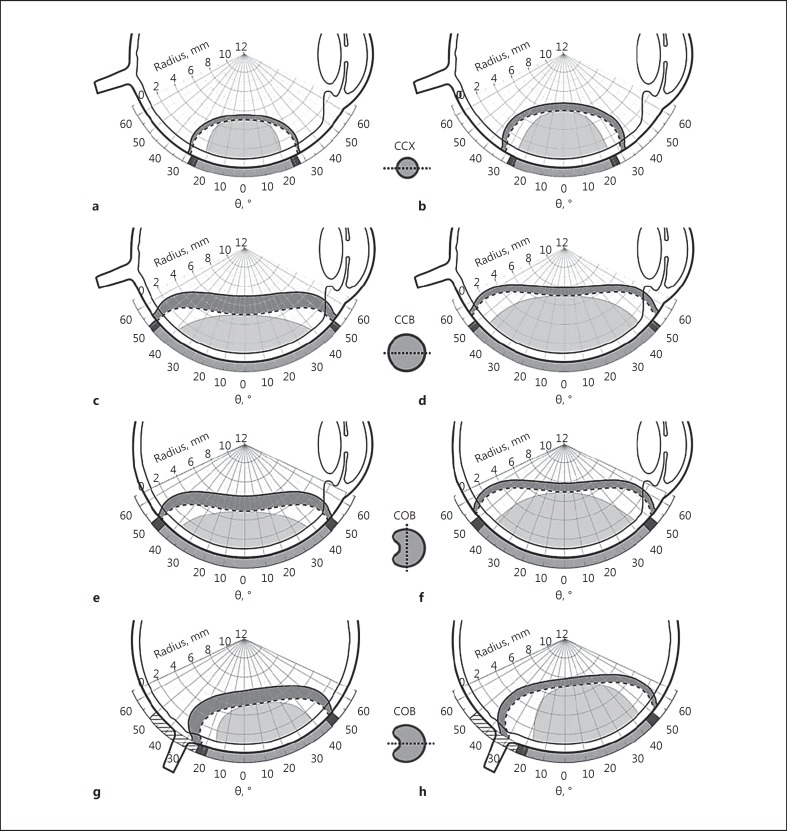

Fig. 3.

Treatment margins arising out of the 85-Gy-to-apex prescription (i) and dose prescription ii of Essen. On the left side, the treatment margins for the 700-Gy-to-base prescription of Essen (ii a) for tumors with an apical height of 5 mm are shown. The dashed line describes the 85-Gy isodose line resulting from the 85-Gy-to-apex prescription (i) and the solid line describes the 85-Gy isodose line resulting from the 700-Gy-to-base prescription of Essen (ii a). On the right side, the treatment margins for the 130-Gy-to-apex prescription of Essen (ii b) for tumors with an apical height of 7 mm (6 mm for CCX) are shown. The dashed line describes the 85-Gy isodose line resulting from the 85-Gy-to-apex prescription (i) and the solid line describes the 85-Gy isodose line resulting from the 130-Gy-to-apex prescription of Essen (ii b). The dark grey areas mark the treatment margins. a, b CCX eye plaque. c, d CCB eye plaque. e, f COB eye plaque perpendicular to the cutout. g, h COB eye plaque through the cutout.

The radioactive isotope 106Ru is a β emitter and decays into 106Rh with a maximal energy of 39 keV and a half-life of 371.5 days. 106Rh subsequently decays with a half-life of 30 s into 106Pd emitting electrons with a maximal energy of 3.54 MeV, the therapeutically relevant radiation [27].

The Geometrical Model of the Eye Containing the Tumor

All following considerations are based on an eye model with a diameter of 24 mm containing a dome-shaped tumor model, which is a common assumption for ocular tumors. The scleral thickness is variable, the mean thickness ranges between 0.40 mm at the equator and 0.86 mm at the posterior pole [11]. For reasons of simplicity, we assumed a thickness of the sclera of 1 mm. Hence, we defined the distance between the surface of the eye plaque and the tumor apex as the apical tumor height. So our definition of the apical tumor height is independent from the assumed thickness of the sclera. It is distinguished between 2 different medium-sized tumors: apical height at 5 mm and at 7 mm from the plaque surface (at 6 mm for the CCX) and the 3 mentioned eye plaque types (CCX, CCB, COB).

Simulations

The geometry of the different eye plaque types as well as the radioactive decay was implemented in Geant4 (version 10.2-p1) [28]. The framework Geant4 can be used to perform Monte Carlo simulations for radiation transport in tissue. The general setup and physics settings for this investigation are based on findings by Sommer et al. [24]. For the radioactive decay and the composition of the different components of the eye plaque, internal Geant4 databases were used. Simulations were performed with the eye plaque surrounded by a cubic water volume with an edge length of 10 cm. The absorbed dose to water was scored in a cylinder, 1 mm in diameter and 0.5 mm in height, chosen correspondingly to the dimensions of the scintillating detector used by the dedicated dosimetry system of the TU Dortmund University [21, 22]. For each setup, 109 decays were generated, ensuring a statistical uncertainty of less than 1%. The results of the simulations were in good agreement with Eichmann [29] and measurements performed with our high-precision dosimetry system as well [21, 22, 23].

Obtained dose distributions were superimposed with the described eye and tumor model.

Dose Prescription

This study focuses on the 85-Gy isodose line assuming this to be the minimum dose required in the target volume for tumor control. The investigated 85-Gy isodose lines arise out of the following prescription points and doses: (i) 85 Gy to the tumor apex, (ii) prescribed dose at Essen: (ii a) not less than 700 Gy to the tumor base and (ii b) 130 Gy to the tumor apex (Fig. 1). The presented treatment margins result from the 2 dose prescriptions (i and ii) in regard to the 85-Gy isodose line.

Results and Discussion

Figure 2 shows section planes of dose distributions of the CCX (Fig. 2a), CCB (Fig. 2b) and COB (Fig. 2c, d) plaque. The shape of the dose distributions strongly depends on the size of the eye plaque. For small eye plaques like CCX, the dose directly decreases from the active center towards the inactive rim (Fig. 2a). For larger eye plaques like CCB, the isodose lines run parallel to the active surface before falling off near the inactive rim (Fig. 2b). The COB eye plaque has an asymmetrical dose distribution, caused by the cutout for the optic nerve. The cross-sectional plane perpendicular to the cutout (Fig. 2c) looks similar to the dose distribution of the CCB plaque. The area enclosed by the isodose lines of the COB plaque is smaller than the one enclosed by the isodose lines of the CCB plaque caused by the smaller active surface of the COB compared to the CCB. In the cross-sectional plane through the cutout (Fig. 2d), the asymmetrical shift of the isodose lines of the COB plaque becomes obvious.

In Figure 3, treatment margins are illustrated for tumors with an apical height (distance between plaque surface and tumor apex) of 5 mm on the left side and 7 mm (6 mm for CCX) on the right side.

For target volumes with an apical height of 5 mm (Fig. 3, left side), the prescribed dose of 700 Gy to the tumor base (cf. Fig. 1, prescription ii a) is sufficient to result in a dose larger than 130 Gy to the apex of the tumor (cf. Fig. 1, prescription ii b). The prescription point is set at a distance of 0.5 mm from the surface of the eye plaque, taking the thickness of the sclera into account. In Figure 3 on the left side, the solid 85-Gy isodose line arising out of prescription (ii a) and the dashed one out of prescription (i) are shown. The area (dark grey) between these 2 isodose lines can be understood as the treatment margin for tumors with an apical height of 5 mm. For the symmetrically formed plaques (Fig. 3a, c), a basal treatment margin is ensured, which is larger than the diameter of the eye plaques. For the CCX, the expansion of the treatment margin is clearly smaller (Fig. 3a) than the one for the CCB (Fig. 3c) due to the smaller active area. For the asymmetric COB plaque in the plane perpendicular to the cutout (Fig. 3e), the basal treatment margin only extends to the visible edge of the plaque and does not go beyond as expected from the dose distributions in Figure 2. In the plane through the cutout (Fig. 3g), none of the 85-Gy isodose lines reach the optic nerve head, which should be taken into account for tumors touching the optic nerve head. The 700-Gy-to-base prescription dose leads to a decreasing margin at the apex for increasing tumor heights.

For target volumes with apical heights of 7 mm (6 mm for CCX; Figure 3, right side), the prescribed dose of 700 Gy to the tumor base (ii a) is not sufficient to result in a dose larger than 130 Gy to the apex of the tumor (ii b). Thus, the tumor apex is chosen as the prescription point and is dosed with 130 Gy (ii b) to ensure a sufficient large margin in apical direction. In Figure 3 on the right side, the solid 85-Gy isodose line arising out of prescription (ii b) and the dashed one out of prescription (i) are shown. The area (dark grey) between these 2 isodose lines defines the treatment margin for tumors with apical heights of 7 mm (6 mm for CCX). A prescription of 130 Gy to the apex (ii b) ensures a margin of 0.8 mm in apical direction for all presented eye plaques. The basal treatment margins are clearly larger than the diameters of the eye plaques (Fig. 3, right side). Because of the higher doses at the base of the tumor, now the 85-Gy isodose line of the COB plaque in the plane through the cutout (Fig. 3h) reaches the optic nerve head.

The dose prescriptions of the University Hospital of Essen ensure treatment margins to the base and apex to cover uncertainties of ocular brachytherapy. Tumors which are irradiated with the COB eye plaque may show a growth over the optic nerve. As shown in Figure 3g and h, for both dose prescriptions, the treatment margin does not cover the whole area above the optic nerve. In the case of a widely expanded tumor, it may be possible that not every part of the tumor receives the required tumor control dose of 85 Gy. Dose adjustments could be necessary. Also, irregular formed tumors can reduce the presented treatment margins.

The size of treatment margins is dependent on the assumed dose required for tumor control. We assumed a minimum dose required of 85 Gy, other centers assume 80 Gy [4]. Lower assumed control doses lead to a wider expanded treatment margin as long as the prescription from Essen is followed. For clinical purposes, it is important to take the very steep dose gradients from 106Ru into account, which can be seen in Figure 2. It should also be remembered that our concept of a “minimal dose to cure the tumor” of 85 Gy is not established for 106Ru plaques but for 125I plaques with much larger irradiated volumes and hence much larger treatment margins. Furthermore, there is no standard established concerning treatment margins in brachytherapy for eye tumors. If the same tumor would be irradiated by protons, most of the proton centers would add a margin of 2.5 mm [15], which results in a larger irradiated volume compared to the models presented in this article.

Differences in the heterogeneous distribution of the emitter substance are not considered in this study and have to be taken into account for clinical treatment planning. Eye plaques can have hot and cold spots and deviate from an ideal distribution [20, 21]. Especially hot or cold spots in the peripheral areas close to the inactive rim can affect the shape of the dose distribution and the resulting treatment margins. Thus, especially if considering treatment of large tumors, it is important to have knowledge of the complete 3-D dose distribution of every individual eye plaque and pay attention to the maximal sclera dose of 1,500 Gy. For this purpose, surface dose distributions [21] in addition with Monte Carlo [20] simulations can be used to get 3-D dose information. In difficult cases, measurements of the complete irradiated volume can be necessary [22].

Conclusion

The dose prescriptions of the University Hospital of Essen ensure sufficient treatment margins for the represented symmetrical eye plaques in the case of a regular dome-shaped tumor. For both eye plaque types, CCX and CCB, the treatment margin at the base of the tumor reaches beyond the visible edge of the eye plaques. This result is independent from the observed eye plaque and can save sufficient treatment margins, taking into account that the only recommendation which is given is a 2- to 3-mm basal margin. Following this recommendation, eye plaques with a diameter larger than the maximal tumor base dimension are chosen [14]. The prescription dose of 700 Gy to the tumor base ensures that in the case of a small to medium-sized tumor, a sufficient treatment margin at the tumor base is formed. In the case of large tumors with apical heights up to 7 mm from the eye plaque surface, the prescription dose of 130 Gy to the tumor apex ensures a treatment margin with an apical expansion of 0.8 mm in addition to the sonographically measured tumor thickness. All findings are based on the assumed tumor control dose of 85 Gy.

Further investigations are necessary to determine the exact dose required for tumor control and the influence of dose inhomogeneities on the resulting treatment margins of individual eye plaques.

This study shows that small tumors of up to 4 mm in tumor thickness can be treated very safely with 106Ru plaques. A safe treatment of tumors with tumor thicknesses of up to 6 mm needs a very detailed knowledge of the dose distribution of the used eye plaque type.

Statement of Ethics

This work does not involve studies on humans, animals, or biological materials.

Disclosure Statement

The authors do not have any conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (project EI869/1–3).

References

- 1.Pe'er J, Ruthenium-106 brachytherapy Jager MJ, Desjardins L, Kivelä T, Damato BE, editors. Current Concepts in Uveal Melanoma. Dev Opthalmol. Basel, Karger. 2012:pp 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damato B, Patel I, Campbell IR, Mayles HM, Errington RD. Local tumor control after 106Ru brachytherapy of choroidal melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson ER, Gallie B, Laperrierre N, Beiki-Ardakani A, Kivelä T, Raivio V, et al. The American Brachytherapy Society consensus guidelines for plaque brachytherapy of uveal melanoma and retinoblastoma. Brachytherapy. 2014;13:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nag S, Quivey JM, Earle JD, Followill D, Fontanesi J, Finger PT. The American brachytherapy society recommendations for brachytherapy of uveal melanomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:544–555. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Collaborative., Ocular Melanoma Study Group The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma, III: initial mortality findings. COMS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:969–982. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pötter R, van Limbergen E, Uveal melanoma . GEC ESTRO Handbook of Brachytherapy. In: Gerbaulet A, Pötter R, van Limbergen E, Mazeron JJ, Meertens H, editors. ESTRO. 2002. pp. pp 591–610. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebrauchsanweisung Ru-106 Augenapplikatoren. Eckert & Ziegler BEBIG GmbH, Berlin, 2013.

- 8.Diener-West M, Albert DM, Frazier Byrne S, Davidorf FH, Followill D, Green RK, et al. Comparison of clinical, echographic, and histopathological measurements from eyes with medium-sized choroidal melanoma in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 21. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1163–1171. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.8.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman DJ, Rondeau MJ, Silverman RH, Lizzi FL. Computerized ultrasonic biometry and imaging of intraocular tumors for the monitoring of therapy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1987;85:49–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook D, Kreutzer TC, Wolf A, Haritoglou C. Variability of standardized echographic ultrasound using 10 mHz and high-resolution 20 mHz B scan in measuring intraocular melanoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;86:1390–1394. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S18513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vurgese S, Panda-Jonas S, Jonas JB. Scleral thickness in human eyes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harbour JW, Murray TG, Byrne SF, Hughes JR, Gendron EK, Ehlies FJ, et al. Intraoperative echographic localization of iodine 125 episcleral radioactive plaques for posterior uveal melanoma. Retina. 1996;16:129–134. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almony A, Breit S, Zhao H, Garcia-Ramirez J, Mansur DB, Harbour JW. Tilting of radioactive plaques after initial accurate placement for treatment of uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:65–70. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison H, Menon G, Larocque MP, Hans HS, Weis E, Sloboda RS. Delivered dose uncertainty analysis at the tumor apex for ocular brachytherapy. Med Phys. 2016;43:4891–4902. doi: 10.1118/1.4959540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sauerwein W, Zehetmayer M. Strahlentherapie intraokularer Tumoren. Onkologe. 1999;5:781–791. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermida-López M. Calculation of dose distributions for 12 106Ru/106Rh ophthalmic applicator models with the PENELOPE Monte Carlo code. Med Phys. 2013;40:101705. doi: 10.1118/1.4820368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brualla L, Zaragoza FJ, Sauerwein W. Monte Carlo simulation of the treatment of eye tumors with 106Ru plaques: a study on maximum tumor height and eccentric placement. Ocul Oncol and Pathol. 2015;1:2–12. doi: 10.1159/000362560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbosa NA, da Rosa LAR, Facure A, Braz D. Brachytherapy treatment simulation of strontium-90 and ruthenium-106 plaques on small size posterior uveal melanoma using MCNPX code. Radiat Phys Chem. 2014;95:224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brualla L, Sempau J, Zaragoza FJ, Sauerwein W. Accurate estimation of dose distributions inside an eye irradiated with 106Ru plaques. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189:68–73. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaragoza FJ, Eichmann M, Flühs D, Sauerwein W, Brualla L. Monte Carlo estimation of absorbed dose distributions obtained from heterogeneous 106Ru eye plaques. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2017;3:204–209. doi: 10.1159/000456717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eichmann M, Flühs D, Spaan B. Development of a high precision dosimetry system for the measurement of surface dose rate distribution for eye applicators. Med Phys. 2009;36:4634–4643. doi: 10.1118/1.3218762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eichmann M, Krause T, Flühs D, Spaan B. Development of a high-precision xyz measuring table for the determination of the 3D dose rate distributions of brachytherapy sources. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:N421–N429. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/22/N421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flühs D, Eichmann M, Kirov A. 2D and 3D scintillation dosimetry for brachytherapy. In: Beddar S, Beaulieu L, Scintillation Dosimetry, editors. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2016. pp. pp 250–269. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sommer H, Ebenau M, Spaan B, Eichmann M. Monte Carlo simulation of ruthenium eye plaques with Geant4: influence of multiple scattering algorithms, the spectrum and the geometry on depth dose profiles. Phys Med Biol. 2017;62:1848–1864. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa5696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckert & Ziegler BEBIG GmbH, Berlin, Germany www.bebig.com.

- 26.Fact Sheet Ru-106 Eye Applicators. Eckert & Ziegler BEBIG GmbH. Berlin, 2016. Available from: http://www.bebig.com/fileadmin/bebig_neu/user_uploads/Products/Ophthalmic_Brachytherapy/Fact_sheet_Ru-106_Eye_Applicators_Rev.05_English.pdf.

- 27.Laboratoire National Henri Becquerel. 2012 Available from http://www.nucleide.org/DDEP_WG/DDEPdata.htm.

- 28.Geant4 Software Download vailable from http://www.geant4.org/geant4/support/download.shtml.

- 29.Eichmann M. Entwicklung eines hochpräzisen Dosimetriesystems zur Messung der Oberflächendosisverteilung von Augenapplikatoren [dissertation] Dortmund, TU Dortmund University. 2009 [Google Scholar]