Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress plays a crucial role in aging-related phenomenon, including skin aging and photoaging. This study investigated the protective role and possible mechanism of Terminalia catappa L. methanolic extract (TCE) in human fibroblasts (Hs68) against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced oxidative damage.

Methods

Various in vitro antioxidant assays were performed in this study. The effect and mechanisms of TCE on oxidative stress-induced oxidative damage were studied by using western blotting.

Results

The IC50 of TCE was 8.2 μg/mL for 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging, 20.7 μg/mL for superoxide anion radical scavenging, 173.0 μg/mL for H2O2 scavenging, 44.8 μg/mL for hydroxyl radical scavenging, and 427.6 μg/mL for ferrous chelation activities. Moreover, TCE inhibited the H2O2-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, resulting in the inhibition of c-Jun, c-Fos, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1, MMP-3, MMP-9, and cyclooxygenase-2 expression. TCE also increased hemeoxygenase-1 expression inhibited by H2O2. Finally, TCE was demonstrated reverse type I procollagen expression in fibroblasts after H2O2 treatment.

Conclusions

According to our findings, TCE is a potent antioxidant and protective agent that can be used in antioxidative stress-induced skin aging.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12906-018-2308-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, Reactive oxygen species, Aging, Hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1), Extracellular matrix

Background

Aging can be divided into two basic processes: intrinsic aging, which is related to age, and extrinsic aging, which is generally due to long-term exposure to environmental factors, including ultraviolet (UV) light and pollutants. Oxidative stress plays a crucial role in aging-related disorders, including atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases and skin aging [1]. High levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion, and singlet oxygen, can cause oxidative damage to cellular DNA, protein, and lipids, resulting in the initiation or development of various disorders and diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cancer [2]. In addition, free transition metal ions combine with H2O2 and can cause extensive oxidative damage to biomolecules such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, leading to age-related disorders [3].

Skin aging is characterized by a sagging appearance, wrinkles, and pigmentary changes, and principally manifests as the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, including type I collagen, elastin, proteoglycans, and fibronectin [4, 5]. Type I collagen is the most abundant structural protein in skin connective tissue and is primarily synthesized by fibroblasts, whereas collagen in the dermis is responsible for skin strength and resiliency [6, 7]. Oxidative stress or inflammation can cause collagen degradation resulting in wrinkle formation and sagging skin [8]. In addition, ROS activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which subsequently induces the expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in human skin [9]. The activation of MAPK and MMPs may cause damage and aging of the skin [10, 11]. Agents that can elevate ECM protein levels or downregulate collagen-degrading enzymes, such as MMPs, may prove useful in the development of effective antiaging agents [12, 13].

Terminalia catappa L. belongs to the family Combretaceae, and in Southeast Asia, it is commonly used as a folk medicine for treating hepatoma and hepatitis [14, 15]. The leaf and bark extracts of T. catappa have been reported to exhibit chemopreventive, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and anti-inflammatory activities [16, 17]. T. catappa includes the phytochemicals of flavanoids (rutin, isoorientin, vitexin, and isovitexin), tannins (chebulagic acid, punicalagin, punicalin, and terflavins A and B), and triterpenoids (asiatic acid and ursolic acid) [14, 18]. In addition, the T. catappa extract exhibits antifungal and antidepressant activities [19, 20]. Topical application of ointment containing T. catappa was shown to promote wound healing in rats [21], and our previous study demonstrated that the T. catappa L. hydrophilic extract exerts protective effects on UVB-induced photoaging by inhibiting MMPs expression and upregulating type I procollagen expression [22]. However, the activity and related mechanisms of T. catappa against oxidative stress-induced skin damaging are unclear. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of T. catappa methanolic extract (TCE) on H2O2-induced skin damage and on the protein expression of MAPKs, which activate protein-1 (AP-1), MMPs, and type I procollagen in human skin fibroblasts (Hs68).

Methods

Chemicals

Fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, trypsin-EDTA, and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) were purchased from Gibco, Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The Bradford reagent was supplied by Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA), and Tris and MTT were purchased from USB (Cleveland, OH, USA). Methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide, doxycycline hyclate, calcium chloride (CaCl2), DPPH, DL-dithiothreitol, and all other reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Preparation and quantitation of TCE

T. catappa leaves were collected in Wufeng, Taichung City, Taiwan, as previously described [22]. The leaves were identified by Professor KC Wen, a professor in Department of Cosmeceutics, China Medical University and a voucher specimen of this material (FCRDSAL-Plants-0003) has been deposited in Functional Cosmeceutics Research & Development and Safety Assessment Laboratory, China Medical University, Taiwan. The dried leaves (150 g) were ground and then extracted twice with 2 L of methanol for 1 h by using ultrasonication. The extraction liquid was filtrated, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness in a vacuum to obtain TCE.

The total phenolic content of TCE was measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu reaction, as previously described [23]. Briefly, TCE was mixed with the Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagent and sodium carbonate, and absorbance was measured at 760 nm. The phenolic content is expressed as microgram GAE/microgram T. catappa leaf dry weight herein.

The total flavonoid content of TCE was determined using the aluminum chloride colorimetric assay, as described elsewhere [23]. Briefly, TCE was mixed with aluminum chloride hexahydrate, potassium acetate, and deionized water, and the absorbance of the mixture was measured at 405 nm on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Tecan, Grödig, Austria). The flavonoid content is expressed as microgram QE/microgram T. catappa leaf dry weight herein.

DPPH radical scavenging activity assay

DPPH was mixed with various concentrations of TCE. The mixture was added to a 96-well microplate and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. Subsequently, absorbance was measured at 492 nm on the ELISA reader. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control [24, 25].

Superoxide anion radical scavenging activity assay

Dihydronicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide, phenazinemethosulfate, and nitroblue tetrazolium were prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), after which TCE was added. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm on the ELISA reader.

Determination of peroxide scavenging activity

The peroxide scavenging activity of TCE was spectrophotometrically detected using a previously described method [23, 26]. H2O2 was prepared in PBS and mixed with various concentrations of TCE. Then, after incubation, absorption was measured at 230 nm on the ELISA reader.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity assay

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity assay was performed by mixing TCE, ascorbic acid, deoxyribose, iron (III) chloride, EDTA, H2O2, a monopotassium phosphate–potassium hydroxide buffer, and distilled water; the mixture was then incubated at 100 °C for 15 min and centrifuged. The absorbance of the supernatant was subsequently measured at 532 nm on a microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Mannitol was used as a positive control, and the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of TCE was obtained as the percentage inhibition of deoxyribose degradation [3, 27].

Ferrous ion chelating activity assay

Various concentrations of TCE were mixed with an iron (II) chloride solution. The reaction was initiated after ferrozine was added. Absorbance was then spectrophotometrically measured at 562 nm on the microplate reader. The results are expressed as the percentage inhibition of the generation of the ferrozine–ferrous complex herein [24].

Measurement of reducing power

The reducing power of TCE was determined using a previously described method [24, 28]. Various concentrations of TCE were mixed with ferrocyanate and trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed with ferric chloride and absorbance was measured at 700 nm. Ascorbic acid and distilled water were used as the positive and negative controls, respectively.

Cell cultures

Hs68, HaCaT cells, and B16F0 cells were purchased from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center in Hsinchu, Taiwan. These cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin in an incubator set at 37 °C.

Cell viability assay for three skin cell lines

To understand the cytotoxicity of TCE on the skin, Hs68, HaCaT cells, and B16F0 cells were applied to study the cell viability. The cells were seeded in the plate, allowed to attach overnight, and were treated with 1 mL of various concentrations of TCE dissolved in DMEM for 24 h. The cytotoxicity of TCE was then evaluated using the MTT assay, as described elsewhere [22].

Fluorescence assay for IntracellularROS generation in fibroblasts

Intracellular ROS generation was measured using a previously detailed method [22]. In brief, fibroblasts were added to a 24-well plate and then incubated with various concentrations of TCE for 24 h. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 150 μM H2O2 for 1 h. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with 10 μM DCFDA in DMEM for 30 min, after which they were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMIL, Wetzlar, Germany). Fluorescence (emission wavelength: 520 nm; excitation wavelength: 488 nm) was measured on a microplate reader (Thermo Electron Corporation, Vantaa, Finland).

Western blotting

The cells were incubated with TCE (5–50 μg/mL) for 4 h, followed by incubation with 150 μM H2O2 for 1 h. The cells were collected and lysed with protein extraction buffer, as previously described [22]. An equal amount of protein was loaded, separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels, and then electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was incubated with specific antibodies against MMP-1, − 3, and − 9; type I procollagen; HO-1; MAPKs; c-Jun; c-Fos; and COX-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The blots were then incubated with anti-immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase and chemiluminescent detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Finally, immunoreactive bands were detected using a chemiluminescent detection system (LAS-4000, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), and the density of the bands was determined using a densitometric program (Multi Gauge V2.2, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analyses

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. The results were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Scheffe’s test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Extraction yield and quantitation of TCE

The extraction yield of TCE from leaves was 11.5%. The total phenolic content of the extract was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method, and the regression coefficient of the calibration curve was 0.9995. Specifically, the total phenolic content of TCE was 220.2 ± 0.2 μg/mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE). Additionally, the total flavonoid content of TCE was determined using the aluminum chloride colorimetric method, and the regression coefficient of the calibration curve was 0.9991. The total flavonoid content was 109.0 ± 0.8 μg/mg quercetin equivalent (QE). The content of gallic acid was 74.62 μg/mL by HPLC/UV analysis (Additional file 1: S1).

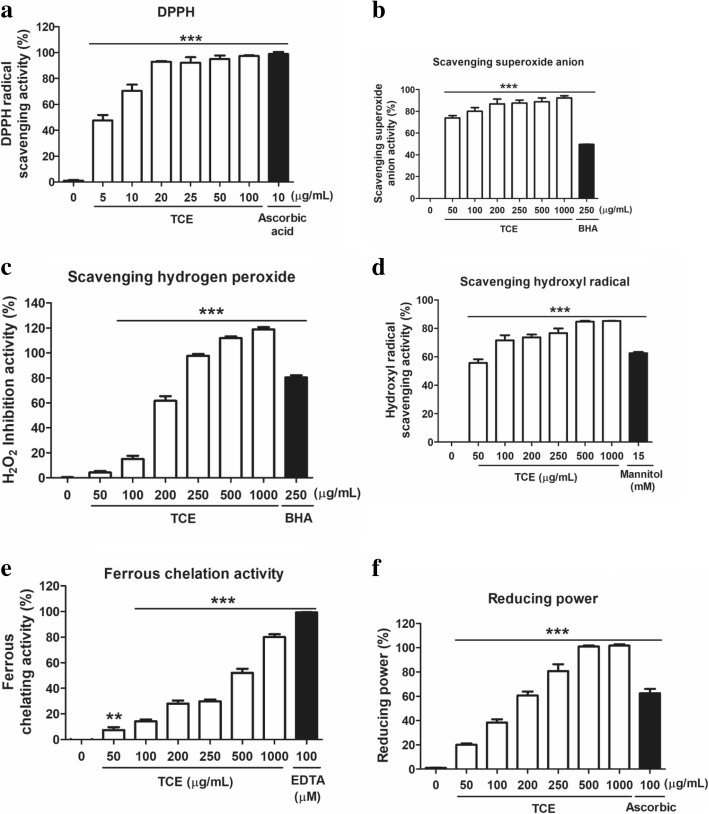

The antioxidant activity of TCE

The antioxidant activity of TCE was study by using free radical scavenging assay and chelating assay. Figure 1a shows the DPPH radical scavenging activity of TCE and 10 μg/mL ascorbic acid (positive control). The results indicated that 10 μg/mL TCE exhibited a scavenging activity of 70.4% ± 4.9%, and that the activity was 99.0% ± 1.6% for the same concentration of ascorbic acid. The IC50 of TCE for DPPH scavenging activity was 5.6 μg/mL; in other words, TCE preparations exhibited potent DPPH free radical scavenging activity. As shown in Fig. 1b, the superoxide anion radical scavenging activity was 49.5% ± 0.2% for 250 μg/mL beta hydroxyl acid (BHA) (positive control), and ranged from 73.9% ± 2.1% to 92.4% ± 2.0% for 50–1000 μg/mL TCE. The IC50 of TCE for superoxide anion radical scavenging was 20.6 μg/mL. Thus, the superoxide anion radical scavenging activity of TCE was superior to that of BHA. The peroxide scavenging activities of TCE (50–1000 μg/mL) and the positive control BHA (250 μg/mL) are shown in Fig. 1c. Specifically, the peroxide scavenging activity ranged from 4.2% ± 1.2% to 111.8% ± 1.3% for various concentrations of TCE, and was 80.4% ± 1.8% for BHA. Notably, the peroxide scavenging activity of TCE was superior to that of BHA (IC50 = 166.1 μg/mL). The hydroxyl radical scavenging activities of TCE (50–1000 μg/mL) and the positive control mannitol (15 mM) are shown in Fig. 1d. Specifically, the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity ranged from 55.7% ± 2.6% to 85.3% ± 0.1% for various concentrations of TCE, and was 62.0% ± 0.9% for mannitol. The IC50 of TCE for hydroxyl radical scavenging was 39.6 μg/mL.

Fig. 1.

The aioxidant activity of Terminalia catappa L. methenolic extract (TCE). a 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging activity of TCE; b Superoxide anion radical scavenging activity of TCE; c Peroxide scavenging activity of TCE; d Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of TCE; e Ferrous chelating activity of TCE; and f Reducing power of TCE. Significant difference versus control (without extract): *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Figure 1e shows the metal chelating activities of TCE and the positive control ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). The activities ranged from 7.5% ± 2.1% to 80.0% ± 2.3% for various concentrations of TCE (50–1000 μg/mL), and was 99.4% ± 0.1% for EDTA (100 μM). The IC50 of TCE was 427.6 μg/mL for metal chelation. The reducing power ranged from 20.1% ± 1.0% to 101.7% ± 1.2% for 50–1000 μg/mL TCE, whereas the reducing power for 100 μg/mL ascorbic acid (positive control) was 62.6% ± 3.5% (Fig. 1f). The IC50 of TCE was 128.5 μg/mL.

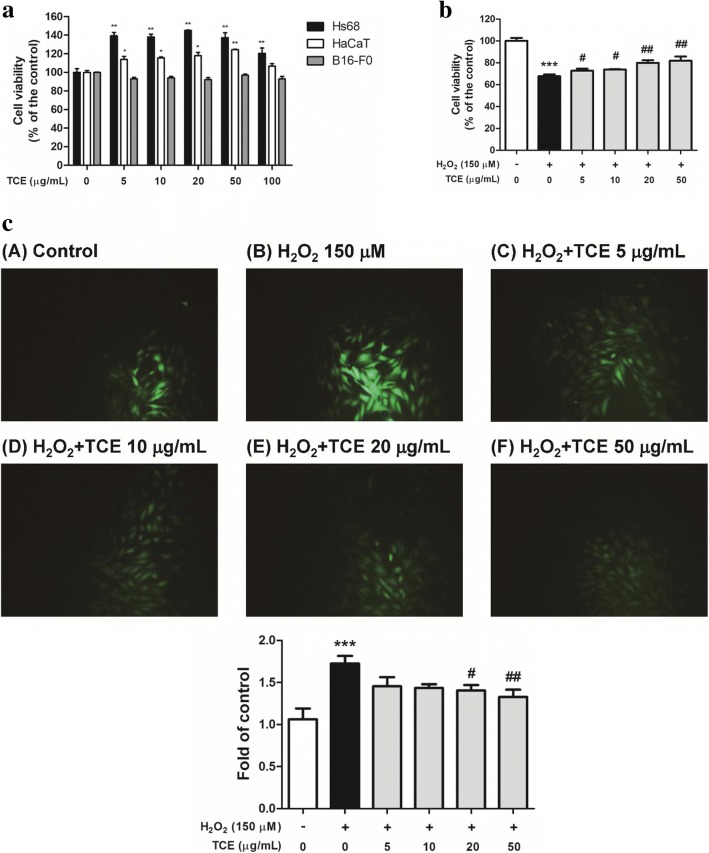

TCE inhibited H2O2−Induced cytotoxicity and intracellular ROS generation

Human fibroblasts (Hs68), human keratinocytes (HaCaT), and mouse melanoma cells (B16F0) were treated with various concentrations of TCE (5–100 μg/mL), and their cell viability was measured using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. As shown in Fig. 2a, the results indicated that TCE did not exhibit cytotoxic effects in the three skin cell lines; these concentrations were thus applied in subsequent experiments.

Fig. 2.

The cytotoxicity and effect on intracellular oxidative stress in Hs68 of TCE. a Cell viability (%) of human fibroblasts (Hs68), human keratinocytes, and mouse melanoma cells treated with TCE; b Cell viability of Hs68 after treatment with TCE with or without 150 μM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) exposure. c Repressive effect of TCE on H2O2-induced intracellular oxidative stress in Hs68. Significant difference versus control: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Significant inhibition versus H2O2-exposed group: #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01

As shown in Fig. 2b, cell viability was 67.6% ± 1.7% after H2O2 treatment. Cell viability ranged from 72.7% ± 1.8% to 81.9% ± 3.9% for 5–50 μg/mL TCE. These results indicated that TCE protects the skin from oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity.

The 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) fluorescence assay was used to qualitatively characterize intracellular ROS generation. As shown in Fig. 2c, ROS levels were markedly higher in H2O2-exposed fibroblasts than in control cells. Moreover, this increase in ROS generation was attenuated in H2O2-exposed fibroblasts pretreated with various concentrations of TCE (5–50 μg/mL). ROS generation in H2O2-exposed fibroblasts increased to 1.7-fold compared with control cells, and significantly decreased to 1.3-fold compared with control cells. TCE at 50 μg/mL decreased H2O2-induced intracellular ROS generation by 23.1%. Thus, TCE protects the skin from ROS damage.

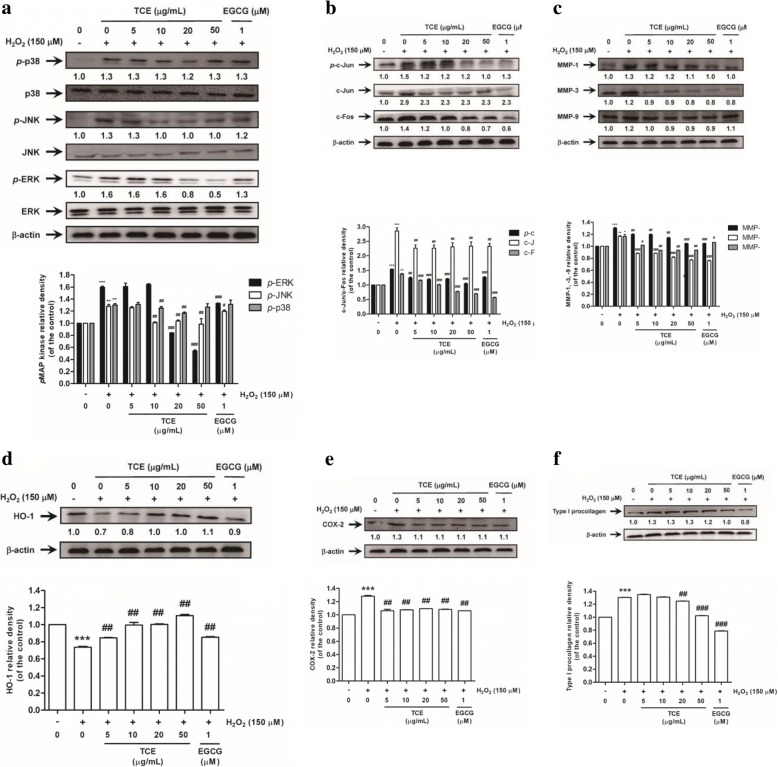

Inhibition of MAPK phosphorylation through TCE

As shown in Fig. 3a, H2O2 induced the phosphorylation of p38, extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). TCE (5–50 μg/mL) dose-dependently inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK, and the effect was significant in the cells treated with > 20 μg/mL TCE. Similar to the effect on ERK, TCE inhibited JNK and p38 activation, which were significantly suppressed when TCE concentration was 20 μg/mL.

Fig. 3.

Effect of TCE on the H2O2-induced (a) phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases, (b) c-Jun phosphorylation and c-Fos, (c) matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1, − 3, − 9, (d) hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1), (e) cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and (f) type I procollagen protein expressions in Hs68. Significant difference versus control: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Significant inhibition versus H2O2-exposed group: #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001. EGCG: (−)-epigallocatechin gallate was used as a positive control

TCE inhibited phosphorylation of AP-1 in Hs68

As shown in Fig. 3b, H2O2 increased c-Jun and p-c-Jun expression to 1.5- and 2.9-fold that of the control, respectively, whereas > 5 μg/mL TCE significantly reduced the effect. In addition, H2O2 induced c-Fos expression, but TCE reduced the effect. These results further indicated that TCE protects the skin from oxidative stress-induced damage.

Effect of TCE on MMP expression in Hs68

To examine whether TCE protects H2O2-exposed Hs68 from oxidative stress-induced damage, the expression of cellular MMP-1, − 3, and − 9 proteins was measured. As depicted in Fig. 3c, H2O2 significantly elevated the expression of MMP-1, − 3, and − 9 proteins by 1.3-, 1.2-, and 1.2-fold compared with controls in Hs68, respectively. By contrast, TCE attenuated H2O2-induced MMP expression. Specifically, treatment with > 5 μg/mL TCE significantly reduced H2O2-induced MMP-1, − 3, and − 9 expression. These results indicated that TCE prevents the H2O2-induced elevation of MMP-1, − 3 and − 9 levels, thus protecting the skin from oxidative stress-induced damage.

Effect of TCE on H2O2-induced Hemeoxygenase-1 expression

The hemeoxygenase (HO)-1 gene and protein play a pivotal role in the modulation of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic activities. This study revealed that H2O2 significantly reduces HO-1 protein expression in Hs68, whereas TCE treatment dose-dependently increases HO-1 expression (Fig. 3d).

Effect of TCE on H2O2-induced Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in Hs68

Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 levels were 1.3-fold higher in fibroblasts exposed to 150 μM H2O2 than in control cells (Fig. 3e). In addition, various concentrations of TCE (5–50 μg/mL) reduced COX-2 expression; the effect was significant in the cells treated with > 5 μg/mL TCE. These results further confirmed that TCE protects the skin from damage by inhibiting inflammation.

Reversal of H2O2-induced upregulation of type I procollagen expression in Hs68 through TCE

After treatment with 150 μM H2O2, the expression of type I procollagen increased to 1.3-fold compared with that in control cells, whereas TCE inhibited this effect (Fig. 3f). Notably, treatment of the cells with 50 μg/mL TCE decreased type I procollagen expression to a level similarly expressed in the control cells.

Discussion

Polyphenols are the second most abundant metabolic products in plants. Notably, plants with high polyphenolic content exhibit potent antioxidant activity [29]. Free radical scavenging activity is related to the polyphenic and flavonoid content of plants. In a previous study, the total phenol content of Rosa hemisphaerica was 138.3 μg/mg GAE [30]. In the present study, the total phenolic content was 220.2 μg/mg GAE dry leaves, the total flavonoid content was 109.0 μg/mg QE dry leaves, and the IC50 of TCE for DPPH radical scavenging was 5.6 μg/mL. In addition, TCE exhibited strong scavenging activity for ROS including superoxide, peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. Peroxide is the primary product of initial oxidation, and it can react with ferrous ions, producing more toxic hydroxyl radicals. Iron also has high reactivity and is the pivotal factor in lipid peroxidation catalyzed by transition metals [3]. Furthermore, TCE exhibits potent metal chelating activity and reducing power attenuating features; in the present study, TCE attenuated H2O2-induced metal chelation, reducing power, ROS generation, and free radical scavenging. Our results suggest that the high polyphenic and flavonoid content of TCE contribute to it potent antioxidant activity.

Molecules such as glutathione, catalase, and HO-1 provide cells, and the body overall, with defense systems against intrinsic and extrinsic oxidative stress. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and Keap1 are redox-sensitive transcription factors and key intracellular modulators of antioxidant defense against environmental stresses. For example, Nrf2 has been reported to protect skin cells from UV- and pollutant-induced oxidative damage and cellular dysfunction [31]. On exposure to oxidative stress, Nrf2 is translocated to the cell nucleus and binds to antioxidant elements, activating phase II detoxification enzymes such as HO-1 and glutathione [32]. In the present study, H2O2 was found to reduce HO-1 expression; however, TCE treatment increased HO-1 expression, alleviating H2O2-induced oxidative stress in the skin cells. In other words, TCE may repair or protect skin from the damage caused by superoxide peroxide and hydroxyl radicals.

Exposure of the skin to UV induces ROS generation and regulates the expression of genes and proteins, resulting in photodamage and photocarcinogenesis [7]. In addition, H2O2 has been reported to cause skin aging by inducing oxidative stress and MMP expression [33], while UVB-induced ROS generation triggers ERK, JNK, and p38 phosphorylation, AP-1 activation, and MMP expression, leading to collagen degradation [7]. In addition, H2O2 disrupts transforming growth factor beta transduction and subsequently inhibits collagen biosynthesis, inducing skin aging [8]. In the present study, H2O2 was determined to upregulate the phosphorylation of MAPKs, c-Jun, c-Fos, and MMP-1, − 3, and − 9 proteins, whereas TCE inhibited these effects. This finding suggests that TCE activity is dependent on this signaling transduction. MMPs mediate degradation of ECM and play an important role in tissue homeostasis and remodeling including angiogenesis and tissue repair. Over suppression of MMPs may cause abnormal accumulation of ECM.

The results are consistent with those of our previous study, in which the T. catappa water extract protected skin from photodamage by inhibiting the MAPK/AP-1/MMP pathway [22]. UVB rays inhibited collagen synthesis and induced collagen degradation, whereas T. catappa water extract elevated the collagen content in Hs68 [22]. Similarly, in the present study, H2O2 was found to increase the collagen content in Hs68, whereas TCE reversed the effect. One previous study showed that H2O2 also reduces mRNA expression of type I collagen (COL1A1) in fibroblasts [34], although these results are inconsistent with those reported elsewhere. For example, researchers demonstrated that H2O2 induces oxidative stress damage to cells and the body, which can trigger the repair process of the skin, thereby increasing the collagen content. However, excessive collagen synthesis may cause collagen fibrosis and scleroderma [35]. Overall, our results here indicate that TCE can regulate the collagen content within a normal range.

Conclusion

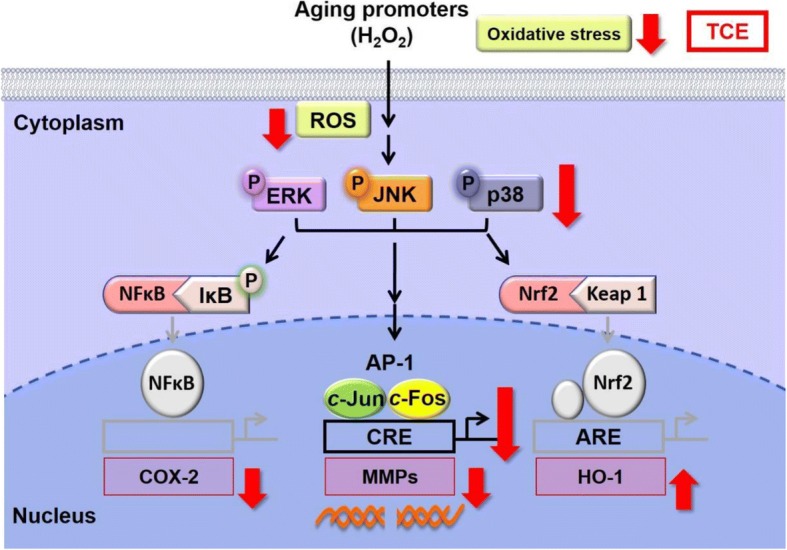

The present study indicated that TCE with high polyphenic and flavonoid content exhibits potent free radical scavenging and antioxidant activity. Specifically, we determined that TCE protects against H2O2-induced skin damage by inhibiting the protein expression of MMP, AP-1, MAPKs, and COX-2 (Fig. 4). The antioxidant and antiaging activities of TCE make it suitable for application in skin care products.

Fig. 4.

Scheme for TCE inhibition of oxidative stress-induced skin damage. (↑: upregulation; ↓inhibition)

Additional file

S1. The active components in Terminalia catappa L. methanolic extract (TCE). (DOCX 134 kb)

Acknowledgments

Experiments and data analysis were partly performed at the Medical Research Core Facilities Center, Office of Research & Development, at China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C. Authors would like to express our very great appreciation to Ms. Jia-Ling Lyu, Ms. Yi-Jung Liu and Mr. Jyun-Shing Wu for their support in data analysis.

Funding

This study was sponsored by China Medical University (CMU103-ASIA-11; CMU105-ASIA-08), Taichung and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 104–2320-B-039-006), Taipei, Taiwan.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

Activate protein-1

- BHA

Beta hydroxyl acid

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- DCFDA

2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ERK

Extracellular signal–regulated kinase

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GAE

Gallic acid equivalent

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- HO-1

Hemeoxygenase-1

- JNK

C-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- QE

Quercetin equivalent

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TCE

Terminalia catappa L. methanolic extract

- UV

Ultraviolet

Authors’ contributions

YHH performed the cell culture and experiments and analyzed the data; PYW, KCW, CYL and HMC conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination; and PYW, KCW, CYL, and HMC wrote and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ya-Han Huang, Email: hedy9088723@hotmail.com.

Po-Yuan Wu, Email: wu.poyuan@gmail.com.

Kuo-Ching Wen, Email: kcwen0520@mail.cmu.edu.tw.

Chien-Yih Lin, Email: yihlin@asia.edu.tw.

Hsiu-Mei Chiang, Phone: +886-4-22053366, Email: hmchiang@mail.cmu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Chen L, Hu JY, Wang SQ. The role of antioxidants in photoprotection: a critical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):1013–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilca GE, Stefanescu G, Badulescu O, Tanase DM, Bararu I, Ciocoiu M. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: current approach and potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:1310265. doi: 10.1155/2017/1310265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ak T, Gulcin I. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;174(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee DH, Oh JH, Chung JH. Glycosaminoglycan and proteoglycan in skin aging. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83(3):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uitto J. The role of elastin and collagen in cutaneous aging: intrinsic aging versus photoexposure. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(2 Suppl):s12–s16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher GJ, Shao Y, He T, Qin Z, Perry D, Voorhees JJ, Quan T. Reduction of fibroblast size/mechanical force down-regulates TGF-beta type II receptor: implications for human skin aging. Aging Cell. 2016;15(1):67–76. doi: 10.1111/acel.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kammeyer A, Luiten RM. Oxidation events and skin aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;21:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch R, Philips N, Suarez-Perez JA, Juarranz A, Devmurari A, Chalensouk-Khaosaat J, Gonzalez S. Mechanisms of photoaging and cutaneous photocarcinogenesis, and photoprotective strategies with phytochemicals. Antioxidants. 2015;4(2):248–268. doi: 10.3390/antiox4020248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher GJ, Wang ZQ, Datta SC, Varani J, Kang S, Voorhees JJ. Pathophysiology of premature skin aging induced by ultraviolet light. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(20):1419–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo YH, Chen CW, Chu Y, Lin P, Chiang HM. In vitro and in vivo studies on protective action of n-phenethyl caffeamide against photodamage of skin. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo Yueh-Hsiung, Lin Tzu-Yu, You Ya-Jhen, Wen Kuo-Ching, Sung Ping-Jyun, Chiang Hsiu-Mei. Antiinflammatory and Antiphotodamaging Effects of Ergostatrien-3β-ol, Isolated from Antrodia camphorata, on Hairless Mouse Skin. Molecules. 2016;21(9):1213. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae JS, Han M, Shin HS, Kim MK, Shin CY, Lee DH, Chung JH. Perilla frutescens leaves extract ameliorates ultraviolet radiation-induced extracellular matrix damage in human dermal fibroblasts and hairless mice skin. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;195:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanlayavattanakul Mayuree, Lourith Nattaya. An update on cutaneous aging treatment using herbs. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2015;17(6):343–352. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2015.1039036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen PS, Li JH, Liu TY, Lin TC. Folk medicine Terminalia catappa and its major tannin component, punicalagin, are effective against bleomycin-induced genotoxicity in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;152(2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00395-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinoshita S, Inoue Y, Nakama S, Ichiba T, Aniya Y. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective actions of medicinal herb, Terminalia catappa L. from Okinawa Island and its tannin corilagin. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(11):755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abiodun OO, Rodriguez-Nogales A, Algieri F, Gomez-Caravaca AM, Segura-Carretero A, Utrilla MP, Rodriguez-Cabezas ME, Galvez J. Antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory activity of an ethanolic extract from the stem bark of Terminalia catappa L. (Combretaceae): in vitro and in vivo evidences. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;192:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anuracpreeda P, Chankaew K, Puttarak P, Koedrith P, Chawengkirttikul R, Panyarachun B, Ngamniyom A, Chanchai S, Sobhon P. The anthelmintic effects of the ethanol extract of Terminalia catappa L. leaves against the ruminant gut parasite, Fischoederius cobboldi. Parasitology. 2016;143(4):421–433. doi: 10.1017/S0031182015001833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dikshit M, Samudrasok RK. Nutritional evaluation of outer fleshy coat of Terminalia catappa fruit in two varieties. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62(1):47–51. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2010.500610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandrasekhar Y, Ramya EM, Navya K, Phani Kumar G, Anilakumar KR. Antidepressant like effects of hydrolysable tannins of Terminalia catappa leaf extract via modulation of hippocampal plasticity and regulation of monoamine neurotransmitters subjected to chronic mild stress (CMS) Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;86:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tercas AG, Monteiro AS, Moffa EB, Dos Santos JRA, de Sousa EM, Pinto ARB, Costa P, Borges ACR, Torres LMB, Barros Filho AKD, Fernandes ES, Monteiro CA. Phytochemical characterization of Terminalia catappa Linn. Extracts and their antifungal activities against Candida spp. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:595. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan AA, Kumar V, Singh BK, Singh R. Evaluation of wound healing property of Terminalia catappa on excision wound models in wistar rats. Drug Res. 2014;64(5):225–228. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1357203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wen KC, Shih IC, Hu JC, Liao ST, Su TW, Chiang HM. Inhibitory effects of Terminalia catappa on uvb-induced photodamage in fibroblast cell line. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:904532. doi: 10.1155/2011/904532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiang HM, Chiu HH, Liao ST, Chen YT, Chang HC, Wen KC. Isoflavonoid-rich Flemingia macrophylla extract attenuates UVB-induced skin damage by scavenging reactive oxygen species and inhibiting MAP kinase and MMP expression. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:12. doi: 10.1155/2013/696879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moein MR, Moein S, Ahmadizadeh S. Radical scavenging and reducing power of Salvia mirzayanii subfractions. Molecules. 2008;3(11):2804–2813. doi: 10.3390/molecules13112804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esmaeili MA, Sonboli A. Antioxidant, free radical scavenging activities of Salvia brachyantha and its protective effect against oxidative cardiac cell injury. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48(3):846–853. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruch RJ, Cheng SJ, Klaunig JE. Prevention of cytotoxicity and inhibition of intercellular communication by antioxidant catechins isolated from Chinese green tea. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10(6):1003–1008. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.6.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen KC, Chiu HH, Fan PC, Chen CW, Wu SM, Chang JH, Chiang HM. Antioxidant activity of Ixora parviflora in a cell/cell-free system and in UV-exposed human fibroblasts. Molecules. 2011;16(7):5735–5752. doi: 10.3390/molecules16075735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Po-Yuan, Huang Chi-Chang, Chu Yin, Huang Ya-Han, Lin Ping, Liu Yu-Han, Wen Kuo-Ching, Lin Chien-Yih, Hsu Mei-Chich, Chiang Hsiu-Mei. Alleviation of Ultraviolet B-Induced Photodamage by Coffea arabica Extract in Human Skin Fibroblasts and Hairless Mouse Skin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(4):782. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nichols JA, Katiyar SK. Skin photoprotection by natural polyphenols: anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and DNA repair mechanisms. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(2):71–83. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-1001-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serteser A, Kargioglu M, Gok V, Bagci Y, Ozcan MM, Arslan D. Determination of antioxidant effects of some plant species wild growing in Turkey. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2008;59(7–8):643–651. doi: 10.1080/09637480701602530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaiprasongsuk A, Lohakul J, Soontrapa K, Sampattavanich S, Akarasereenont P, Panich U. Activation of Nrf2 reduces UVA-mediated MMP-1 upregulation via MAPK/AP-1 signaling cascades: the photoprotective effects of sulforaphane and hispidulin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;360(3):388–398. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.238048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim YG, Sumiyoshi M, Sakanaka M, Kimura Y. Effects of ginseng saponins isolated from red ginseng on ultraviolet B-induced skin aging in hairless mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;602(1):148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park MJ, Bae YS. Fermented Acanthopanax koreanum root extract reduces UVB- and H2O2-induced senescence in human skin fibroblast cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26(7):1224–1233. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1602.02049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park G, Jang DS. Oh MS. Juglans mandshurica leaf extract protects skin fibroblasts from damage by regulating the oxidative defense system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421(2):343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGaha TL, Phelps RG, Spiera H, Bona C. Halofuginone, an inhibitor of type-I collagen synthesis and skin sclerosis, blocks transforming-growth-factor-beta-mediated Smad3 activation in fibroblasts. J Investig Dermatol. 2002;118(3):461–470. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S1. The active components in Terminalia catappa L. methanolic extract (TCE). (DOCX 134 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.