Abstract

Background

To predict the prognosis by observing the dynamic change of C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) for hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

Methods

The data were collected from January to December 2017 from the first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. Demographic and clinical patient information including age, length of hospital stay and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were recorded. Blood samples were taken for CRP, PCT, and white blood cell count (WBC). Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was used to verify each biomarker’s association with the prognosis of pneumonia.

Results

A total of 350 patients were enrolled in the study. The 30-day mortality was 10.86%. Serial serum CRP3, CRP5, PCT3, PCT5 and PCT5c levels were statistically lower in CAP survivors than non-survivors. CRP3c < 0, CRP5c < 0 and PCT5c < 0 were observed with a statistically lower frequency in patients with 30-day mortality and initial treatment failure. The AUC for 30-day mortality for serial CRP levels combined with CRP clearances was 0.85 (95% CI 0.77–0.92), as compared to an AUC of 0.81 (95% CI 0.73–0.9) for serial PCT levels combined with PCT clearances.

Conclusions

Serum serial CRP and PCT levels had moderate predictive value for hospitalized CAP prognosis. The dynamic CRP and PCT changes may potentially be used in the future to predict hospitalized CAP prognosis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12931-018-0877-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Serial serum CRP, PCT, Predictive value, CAP prognosis

Background

Diagnosis of pneumonia in critically ill patients is usually challenging. Signs and symptoms with enormous heterogeneity, such as dyspnea, may be non-diagnostic or atypical, chest X-ray results may be uncertain, also complications may be confounding factors [1–3]. Thus, biomarkers of inflammation or infection, such as procalcitonin (PCT) and C-reactive protein (CRP), have been proposed as a guide in the diagnostic process [4–6]. Elevated serum PCT and CRP were associated with community-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) [5, 7].

CRP is a well-established biomarker in many clinical settings, but has been traditionally considered insufficient as a useful marker in the diagnosis of pneumonia. In fact, all infections, stress reactions, autoimmunity and tumor disease can contribute to the increase in serum CRP values [8].

PCT is a 116-amino acid long precursor of calcitonin, which is produced by the thyroid. In sepsis, macrophages and the monocytic cells of the liver are involved in the synthesis of PCT,which is elevated in sepsis [9, 10]. The degree of induction of PCT correlates with the severity of systemic infection and the presence of organ dysfunction.

Due to multiple confounding factors, several studies have reported controversial results on the role of CRP and PCT in the diagnosis of pneumonia in multiple elderly patients [1, 11, 12]. The importance of serum CRP and PCT levels on diagnosis is well established [5, 7, 13, 14], The mean values of certain cytokines are statistically different from patients with treatment failure vs patients without treatment failure, the wide range of values for particular cytokines make it difficult to use the value of a single patient to predict clinical outcomes. A dynamic approach of assessing biomarkers may provide additional survival information. Markers of the inflammatory response and their kinetics have been studied in the prediction of outcomes in sepsis [15] and VAP [16, 17]. As reported by Huang MY, et al., PCT clearance (PCTc) has been introduced in a previous studies as a tool for monitoring the changes of PCT levels during severe sepsis [18, 19]. Similar to PCTc in the previous study, in our study we introduced CRP clearance (CRPc) to monitor the changes of CRP levels during the treatment of hospitalized CAP. Since PCTc and CRPc measures the relative changes in PCT and CRP to the baseline levels, they are postulated to be a better predictor of prognosis. However, both PCTc and CRPc are not common in clinical practice.

Therefore, the hypothesis of this study is whether CRP and PCT levels and their clearance could serve as prognostic biomarkers for hospitalized CAP patients. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the usefulness of CRP and PCT levels and their clearance as prognostic biomarkers for hospitalized CAP patients.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This was a single-center, prospective observational study. Hospitalized pneumonia patients with a radiological confirmation were recruited. The informed consents were obtained from all subjects or their guardians. The study was approved by ethic committee of Zhengzhou University and met the declaration of Helsinki. Diagnosis of CAP required the presence of at least one respiratory symptom in addition to one auscultatory finding or signs of infection (WBC > 10 × 109/L or < 4 × 109/L cells, shivers, core body temperature > 38.0 °C) and a new infiltrate on chest radiograph. The respiratory symptoms included cough, expectoration, dyspnea, tachypnea, or pleuritic chest pain [20]. Radiological findings were verified with results of the real-time PCR tests on blood samples and nasopharyngeal swabs. The Clinical severity of the hospitalized CAP was evaluated by the CURB-65 score, which including confusion, urea, respiratory, and blood pressure plus age > 65 years.

Measurement of biomarkers

Followed our study design, WBC counts were measured as a part of routine tests using Beckman-coulter LH750 hematology analyzer. Serum CRP and PCT levels were measured on hospital days 1, 3, and 5 in patients. The blood was drawn in vacuum tube filled with separation gel and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 min, and then CRP and PCT were analyzed by Roche cobas 8000 automatic biochemistry analyzer within 30 min. Concentrations of CRP were determined by an immunoturbidimetric assay. The diagnostic cut-off value of CRP was set by manufacturer at 5 mg/L. PCT (ng/mL) levels were measured by electro chemiluminescence immunoassay with a lower limit of detection of 0.02 ng/ml. CRP and PCT levels measured on day 1, day 3 and day 5 were defined as CRP1 and PCT1, CRP3 and PCT3, CRP5 and PCT5, respectively. PCTc was calculated based on the previously reported formula [19], (PCTday3/day5-PCTday1)/PCTday1 × 100% = PCT3c /day5c (%). The calculation of CRPc was referred to the PCTc formula. CRPc on day3 and day5 were abbreviated as CRP3c and CRP5c.

The detection of CAP pathogen

Viral RNA or DNA was extracted from the respiratory secretions within 24 h, and was then tested using respiratory virus panel (Shanghai ZJ Bio-Tech Co., Ltd) fast assay to detect influenza A/B virus (lot: RR-0226-02), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-A (RR-0160-01) and -B (lot:RR-0160-02), parainfluenzavirus-1, − 2, − 3 and − 4 (lot: RR-0156-01,02,03,04), adenovirus (lot:RD-0195-02), human metapneumovirus (hMPV) (lot: RR-0162-02) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

The autolysin-A (LytA) and wzg (cpsA) genes of S. pneumoniae were tested using real-time PCR from blood and swab samples for pneumococcal cases according to the manufacture instructions. M. pneumoniae was looked for in blood and nasopharyngeal swabs with nested PCR, as described previously [21]. Routine microbiological examinations were also performed at the Microbiology laboratory and included blood culture, sputum culture, and antigenuria.

Statistical analysis and data management

Data were analyzed using SPSS v.17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows. Frequency comparison was done using the χ2-test. The two-group comparison for continuous data was done with the Mann-Whitney U-test. We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis to study the association between biomarker levels and outcome adjusting the models for the CAP severity score CURB-65 and age. ROC curves were used to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of PCT and CRP vs pneumonia prognosis. The areas under the curve (AUC) were reported with its 95% confidence interval (CI). All p-values were two-tailed and were considered significant for p < 0.05.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was 30-day mortality and the secondary endpoint was initial treatment failure. Both endpoints were assessed by seven medical students, blinded to the goal and design of the study, by conducting standardized follow-up interviews by telephone at 30 days after baseline. Initial treatment failure was defined as occurring in patients whose antimicrobial agents were changed by the attending physicians because they were ineffective referring to the CAP guideline in China [22]. Serial changes in PCT, CRP, and WBC were analyzed for their potential to estimate the clinical prognosis/outcome.

Results

Demographics and clinical presentations

Baseline characteristics of survivors and non-survivors were presented in Table 1. This study included a total of 350 patients with a median age of 58.53 years (58.3% males). The 30-day mortality was found in 10.86% (38/350) of all patients. Patients had a high burden of comorbidities including chronic heart disease (n = 100), chronic liver disease (n = 22), chronic renal disease (n = 47), malignant disease (n = 26), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD, n = 22) and diabetes (n = 30). Cough (n = 268, 76.6%) and dyspnea (n = 249, 71.1%) were the most frequent symptoms. No significant differences of comorbidities and symptoms were found between survivors and non-survivors. CAP was ascribed to bacteria in 176 (50.29%) patients and to one or more viruses in 115 (32.86%) patients (Additional file 1: Table S1). Serial serum CRP3, CRP5, PCT3, PCT5 and PCT5c levels were statistically lower in CAP survivors than non-survivors (Table 1). CRP3c < 0, CRP5c < 0 and PCT5c < 0 were observed with a statistically lower frequency in patients with 30-day mortality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of survivors and non-survivors

| All patients (%) n=350 |

Survivors (%) n=312 |

Non-Survivors (%) n=38 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 58.53±19.1 | 58.59±19.2 | 58.03±18.9 | 0.86 |

| Males | 204 (58.3) | 181(58.0) | 23(60.5) | 0.7 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 30(8.57) | 27(8.6) | 3(7.8) | 0.87 |

| Chronic heart disease | 100(28.57) | 91(29.1) | 9(23.6) | 0.48 |

| Chronic liver disease | 22(6.29) | 20(6.4) | 2(5.2) | 0.78 |

| Chronic renal disease | 47(13.43) | 40(12.8) | 7(18.4) | 0.34 |

| Malignant disease | 26(7.43) | 24(7.6) | 2(5.2) | 0.59 |

| History of Shock | 17(4.86) | 15(4.8) | 2(5.2) | 0.9 |

| COPD | 22(6.29) | 18(5.7) | 4(10.5) | 0.25 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 39(11.14) | 35(11.2) | 4(10.5) | 0.9 |

| Antimicrobial treatment before admission | 79(22.6) | 70(22.4) | 9(23.7) | 1 |

| Signs and symptoms | ||||

| Cough | 268(76.6) | 260(83.3) | 28(73.6) | 0.14 |

| Chest pain | 116(33.1) | 106(33.9) | 10(26.3) | 0.34 |

| Expectoration | 168(48) | 148(47.4) | 20(52.6) | 0.54 |

| Dyspnea | 249(71.1) | 221(70.8) | 28(73.6) | 0.72 |

| Chills | 124(35.4) | 109(34.9) | 15(39.4) | 0.58 |

| Headaches | 75(21.4) | 58(18.5) | 17(44.7) | <0.001 |

| Myalgia | 79(22.6) | 71(22.7) | 8(21) | 0.8 |

| Crackles | 114(32.6) | 102(32.6) | 12(31.5) | 0.89 |

| Fever | 110(31.4) | 96(30.7) | 14(36.8) | 0.45 |

| Confusion | 5(1.4) | 1(0.3) | 4(10.5) | <0.001 |

| CCI class | ||||

| 0-2 | 129(36.8) | 116(37.1) | 13(34.2) | 0.7 |

| 3-5 | 180(51.4) | 161(51.6) | 19(50) | |

| >5 | 41(11.7) | 35(11.2) | 6(15.7) | |

| CRP1 (mg/L) | 65.3±84.7 | 66.3±85.2 | 57.1±81.3 | 0.53 |

| CRP3 (mg/L) | 56.4±77.4 | 50±66.4 | 109.1±128.4 | <0.001 |

| CRP3c | 556.6±5056.3 | 575.2±5334.2 | 401.2±1242.4 | 0.843 |

| CRP3c<0 | 223(63.7) | 214(68.5) | 9(23.6) | <0.001 |

| CRP5(mg/L) | 44.8±68.5 | 37.9±61 | 102.1±96.9 | <0.001 |

| CRP5c | 429.2±3489.6 | 429.2±3670.1 | 429.3±1207.6 | 0.999 |

| CRP5c<0 | 222(63.4) | 213(68.2) | 9(23.6) | <0.001 |

| PCT1 (ng/mL) | 1.8±7.1 | 1.8±7.3 | 1.9±5.5 | 0.96 |

| PCT3 (ng/mL) | 1.7±6.3 | 1.4±4.4 | 4.1±14.5 | 0.012 |

| PCT3c | 791.2±2653.8 | 793.3±2672.6 | 774.1±2528.7 | 0.966 |

| PCT3c<0 | 174(49.7) | 157(50.3) | 17(44.7) | 0.52 |

| PCT5 (ng/mL) | 1.2±3.7 | 0.8±2 | 4.3±9.3 | <0.001 |

| PCT5c | 695.3±2463 | 589.9±2298.2 | 1555±3454.4 | 0.022 |

| PCT5c<0 | 179(51.1) | 170(54.4) | 9(23.6) | <0.001 |

| WBC1 | 10.4±8 | 10.1±7.2 | 12.6±12.8 | 0.081 |

| WBC3 | 9.5±5 | 9.2±5 | 10.8±4.7 | 0.112 |

| WBC5 | 10.5±6.6 | 10.4±7 | 10.6±4.7 | 0.932 |

| CURB class | ||||

| 0-2 | 289 | 256 | 33 | 0.46 |

| 3-5 | 61 | 56 | 5 | |

Data are presented as means ±SD, or n (%), CRP, C-reactive protein; CURB-65, confusion, urea > 7 mmol/L, respiratory rate≥30 breaths/min, low blood pressure (systolic<90mm Hg or diastolic≤60 mm Hg) and age≥65 years

PCT procalcitonin, COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, SD standard deviation, WBC white blood cell, CRP3c 5c: CRP clearance on day3, day5 PCT3c, 5c PCT clearance on day 3, day 5

Statistic analysis for clinical factors and CAP

WBCs, CRP, and PCT levels on hospital days 1, 3, and 5 and their clearance were compared in all groups. The average mean value of these biomarkers comparison is reported in Tables 2, 3 and Additional file 2: Table S2. ANOVA analysis showed that the CAP patients with bacteria pathogens had significantly higher values of CRP and PCT (P < 0.05) than those with other causative pathogens (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of biomarkers for 30-day mortality

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Univariate P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Multivariate P-value | |

| CRP1 (mg/L) | 0.998(0.994–1.003) | −0.001 | 0.53 | |||

| CRP3 (mg/L) | 1.006(1.003–1.01) | 0.006 | < 0.001 | 1.013 (1–1.025) | 0.012 | 0.002 |

| CRP3c | 0.999(0.999–1) | 0 | 0.845 | |||

| CRP3c < 0 | 1.02(0.991–1.049) | 0.019 | 0.174 | |||

| CRP5(mg/L) | 1.008(1.004–1.01) | 0.008 | < 0.001 | 1.011 (1–1.021) | 0.011 | 0.028 |

| CRP5c | 1(0.999–1) | 0 | 0.999 | |||

| PCT1 (ng/mL) | 1.001(0.955–1.05) | 0.001 | 0.96 | |||

| PCT3 (ng/mL) | 1.036(0.998–1.07) | 0.035 | 0.06 | |||

| PCT3c | 0.999(0.999–1) | 0 | 0.966 | |||

| PCT5 (ng/mL) | 1.21(1.08–1.357) | 0.191 | < 0.001 | 1.277 (1.004–1.624) | 0.244 | 0.046 |

| PCT5c | 1(0.999–1) | 0 | 0.052 | |||

| WBC1 | 1.025(0.993–1.059) | 0.025 | 0.117 | |||

| WBC3 | 1.061(0.985–1.143) | 0.059 | 0.118 | |||

| WBC5 | 1.004(0.906–1.113) | 0.004 | 0.931 | |||

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of biomarkers for initial treatment failure

| Initial treatment failure | Univariate Odds ratio(95% CI) | Univariate P-value | Multivariate Odds ratio(95% CI) | Multivariate P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| CRP1 (mg/L) | 71±88.7 | 64±83.9 | 0.999(0.996-1.003) | 0.55 | 1.008(1.001-1.013) | 0.009 |

| CRP3 (mg/L) | 89.2±107.6 | 48.9±66.8 | 0.995(0.991-0.998) | 0.001 | 0.992(0.985-0.999) | 0.035 |

| CRP3c | 801.8±3644.9 | 501±5328.5 | 1 | 0.673 | 1(0.999-1) | 0.33 |

| CRP5(mg/L) | 79.7±96.3 | 37.2±58.3 | 0.993(0.989-0.997) | <0.001 | 0.996(0.989-1.001) | 0.15 |

| CRP5c | 682.9±2888.4 | 371.7±3614.2 | 1 | 0.534 | 1(0.999-1) | 0.299 |

| PCT1 (ng/mL) | 4.6±13.6 | 1.2±4.2 | 0.936(0.892-0.983) | 0.009 | 0.89(0.82-0.965) | 0.005 |

| PCT3 (ng/mL) | 2.8±11.2 | 1.4±4.5 | 0.975(0.941-1.01) | 0.163 | 1.134(1.017-1.263) | 0.022 |

| PCT3c | 469.1±1972.7 | 865.2±2784.4 | 1 | 0.293 | 1(0.999-1) | 0.403 |

| PCT5 (ng/mL) | 2.8±7.3 | 0.8±2.1 | 0.868(0.892-0.983) | 0.005 | 0.851(0.751-0.963) | 0.01 |

| PCT5c | 1013.8±2761.2 | 622.1±2388.7 | 1 | 0.268 | 1(0.999-1) | 0.658 |

a Variable(s) entered on step 1: CRP1, CRP3, CRP3c, CRP5, CRP5c, PCT1, PCT3, PCT3c, PCT5, PCT5c, and CURB65

We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression models to investigate associations between serum biomarker levels and outcome (Table 2). In univariate analysis, no significant association of CRP1 [OR (95% CI): 0.998(0.994–1.003)] and PCT1 levels [OR (95% CI): 1.001(0.955–1.05)] or WBC counts with 30-day mortality was found. Significant predictive ability was found for 30-day mortality with CRP3 [OR (95% CI): 1.006(1.003–1.01)], CRP5 [OR (95% CI): 1.008(1.004–1.01)] and PCT5 [OR (95% CI): 1.21(1.08–1.357)] levels respectively. The significance did not disappear after adjust for age, sex and CURB-65 in multivariate logistic regression model.

This study did not show that patients with initial treatment failure had significant higher CRP1 levels than others (71 vs 64, P = 0.55). On the other hand, patients with initial treatment failure had significantly higher levels of CRP3, CRP5, PCT1, PCT3 and PCT5 than others (Table 3), which indicated that serial measurements of these serum biomarker levels were also useful for predicting whether initial CAP treatment would be successful.

Correlation between PCT and CRP and their clearance

Assessment of correlation between biomarkers was performed by Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. Table 4 showed correlations of CRP, PCT and their clearance in the overall population. At baseline, day 3 and day 5, we found significant correlations between PCT and CRP, no correlations were found for PCT3c and CRP3c (R2 = 0.09, P = 0.11). However, the maximum correlation coefficient was 0.35, which is smaller than 0.8, indicating the low level of multicollinearity among each biomarker.

Table 4.

Correlation of biomarkers characteristics at different time

| PCT1(ng/ml) | PCT3(ng/ml) | PCT5(ng/ml) | PCT3c | PCT5c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP1 (mg/L) |

R2=0.35 P=0.0001* |

||||

| CRP3 (mg/L) |

R2=0.19 P=0.0001* |

||||

| CRP3c |

R2=0.09 P=0.11 |

||||

| CRP5(mg/L) |

R2=0.21, P=0.0001* |

||||

| CRP5c |

R2=0.17 P=0.002* |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

*Pearson Correlation was used to test the correlation between biomarkers

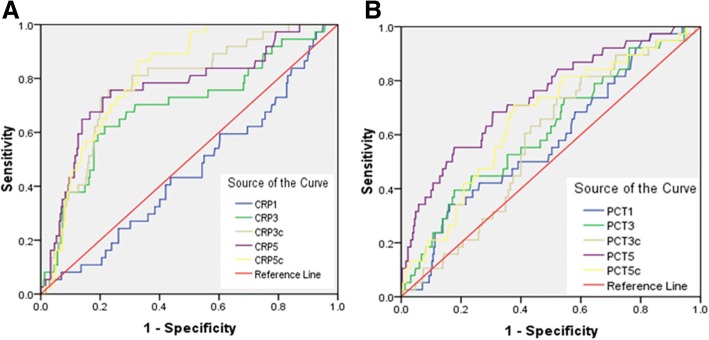

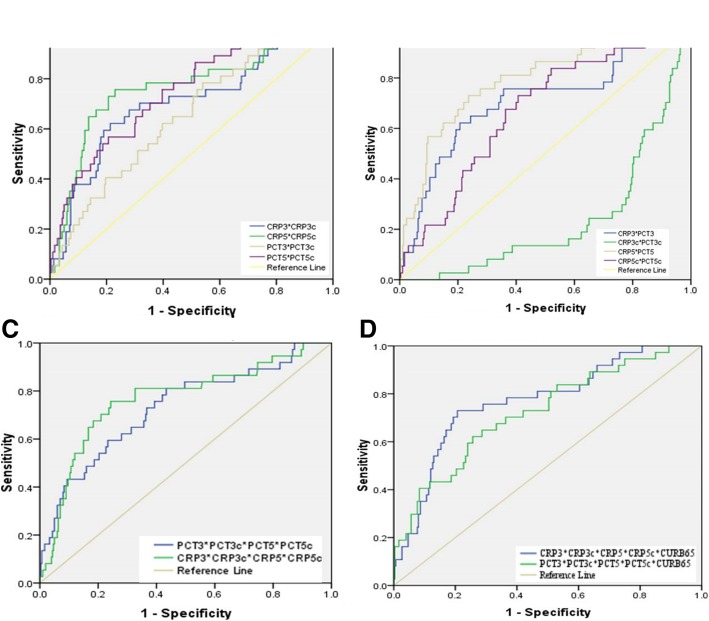

Prognostic accuracy of serial values of PCT and CRP

Table 5 showed the ROC curve of each biomarker and each biomarker combined. For the single biomarker, the peak areas under the ROC curve of CRP5c and PCT5 to predict 30-day mortality was 0.81 (95%CI: 0.75–0.87; P < 0.001) and 0.73 (95%CI: 0.65–0.82; P < 0.001), respectively (Table 5, Fig. 1a, b). The capacity of serial serum biomarkers combined to predict 30-day mortality was higher than only one biomarker or a combination of two of the biomarkers. The AUC for 30-day mortality for serial CRP levels combined with CRP clearances was 0.85 (95% CI 0.77–0.92), as compared to an AUC of 0.81 (95% CI 0.73–0.9) for serial PCT levels combined with PCT clearances. Furthermore, their AUC-ROC did not increase if they were used in combination with CURB65 (Table 5, Fig. 2c, d).

Table 5.

Prognostic performance of Biomarkers and CURB-65 in predicting pneumonia prognosis

| Variable(s) | AUC | SE | P value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP1 (mg/L) | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.36-0.55 |

| CRP3 (mg/L) | 0.69 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.6-0.8 |

| CRP3c | 0.77 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.7-0.85 |

| CRP5(mg/L) | 0.76 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.67-0.85 |

| CRP5c | 0.81 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.75-0.87 |

| PCT1 (ng/mL) | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.49-0.67 |

| PCT3 (ng/mL) | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.52-0.71 |

| PCT3c | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.49-0.66 |

| PCT5 (ng/mL) | 0.73 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.65-0.82 |

| PCT5c | 0.65 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.57-0.75 |

| CRP1*PCT1 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.45-0.65 |

| CRP3*CRP3c | 0.7 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.6-0.8 |

| CRP5*CRP5c | 0.77 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.68-0.86 |

| PCT3*PCT3c | 0.65 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.56-0.74 |

| PCT5*PCT5c | 0.74 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.66-0.83 |

| CRP3*PCT3 | 0.7 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.6-0.81 |

| CRP3c*PCT3c | 0.76 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.68-0.84 |

| CRP5*PCT5 | 0.79 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.71-0.87 |

| CRP5c*PCT5c | 0.67 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.58-0.76 |

| CRP5*CRP5c*PCT5*PCT5c | 0.79 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.71-0.87 |

| CRP3*CRP3c* CRP5*CRP5c | 0.85 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.77-0.92 |

| PCT3*PCT3c*PCT5*PCT5c | 0.81 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.73-0.9 |

| CRP3*CRP3c* CRP5*CRP5c* PCT3*PCT3c*PCT5*PCT5c | 0.81 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.73-0.88 |

| CURB-65 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 0.44-0.63 |

| CRP3*CRP3c*CRP5*CRP5c*CURB-65 | 0.77 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.69-0.85 |

| PCT3*PCT3c*PCT5*PCT5c*CURB-65 | 0.72 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.64-0.81 |

aUnder the nonparametric assumption

bNull hypothesis: true area = 0.5

cROC receiver operating characteristic, AUC area under the curve, SE standard error, CI confidence interval

Fig. 1.

ROC curve of CRP, PCT levels and their clearance vs pneumonia prognosis

Fig. 2.

Prognostic performances of Biomarkers and CURB-65 in predicting pneumonia prognosis

Discussions

In accordance with the current literature, the clinical characteristics of the patients included in this study frequently had a comorbidity of respiratory disorders, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure and cancer [23]. So far, most studies focused on the diagnostic performance of serum biomarkers, especially CRP and PCT on the pneumonia diagnosis [1, 5, 7, 11, 24, 25]. Only very few research studied the predictive value of serum biomarkers in the pneumonia outcomes [6, 14, 17, 26–28]. A dynamic approach to biomarkers could capture the progression of disease and might be more effective in evaluating pneumonia prognosis.

In this context, we observed serum CRP and PCT levels measured at different time points after admission. The main findings of this study are threefold. First, circulating CRP and PCT levels were significant different in the pneumonia patients infected with different pathogens. However, there was no significance of the serum CRP1 and PCT1 levels between survivors and non-survivors. This indicated that the initial CRP and PCT levels could not provide useful information to assist with mortality prediction in hospitalized CAP patients, which was consistent with the results from previous studies. Previous studies had showed that simply measuring the initial CRP and PCT levels did not improve clinical score for mortality but that following the kinetics of PCT did so [6, 29]. However, Akihiro ITO’s study found that the initial CRP and PCT levels were significant different between survivors and non-survivors [30]. Furthermore, they found that PCT levels on day3/day1 ≥ 1, CRP levels on day1 ≥ 100 mg/L and CURB-65 ≥ 3 were prognostic variables in CAP. The different basic characteristics of research groups in these studies were the main reasons for the different results. The average age in our study was younger than Akihiro ITO’s study (58.53 vs. 73.2), while composition ratio of CURB-65 class was similar (Class 0–2: 82.6 vs. 75.9, Class 3–5: 17.4 vs. 24.1). Similar proportion of CURB-65 in the population aged below and above 65 years old, indicating the more complicate comorbidities or more severe CAP disease in our study which resulting the similar initial CRP and PCT levels between survivors and non-survivors.

Second, consistent with the previous report [6], CRP levels were independent prognostic predictors of CAP clinical outcomes. PCT has been used as a biomarker for initiating or terminating antibiotic therapy in various clinical settings in the previous studies [31, 32]. In this work, we confirmed the predictive role of CRP and PCT in CAP prognosis. Serial serum CRP3, CRP5, PCT3, PCT5 and PCT5c levels were statistically lower in CAP survivors than non-survivors. CRP3c < 0, CRP5c < 0 and PCT5c < 0 were observed with a statistically lower frequency in patients with 30-day mortality and initial treatment failure. Significant predictive ability was found for 30-day mortality with CRP3, CRP5 and PCT5 levels.

Third, there was low level of multicollinearity among each biomarker. The capacity of serial serum biomarkers combined to predict 30-day mortality was higher than only one biomarker or a combination of two of the biomarkers. Though the CRP and PCT clearances were not directly associated with the CAP prognosis, when combined with the serum biomarker levels, the increased AUC-ROC indicated the greater prognosis capacity. This was consistent with previous report [33], CRP kinetics can be used to identify ventilator-associated pneumonia patients with poor outcome. This also highlighted the necessary to measure the values of serum biomarkers serially. However, the combination with CURB65 did not increase the predictive AUC-ROC of serum biomarker.

There were some limitations in our study. Firstly, the missing data for laboratory biomarkers in some patients, potential classification bias in the etiologic diagnosis. However, our evaluation has been done in a large study population even excluding missing data. Secondly, since the average age of the patients in our study was near 60 years old, whether these results are generalizable to CAP patients in children or aged greater than 80 years old needs further evaluation. Finally, the objects studied usually combined with other diseases, which might affect the serum CRP and PCT levels. But the complicated diseases were the true status for most hospitalized CAP patients. Thus, further studies with a prospective design are needed to explore the influence of other comorbidity on the biomarkers level and hospitalized CAP prognosis.

Conclusions

This is a large and comprehensive study focused on the predictive value of serum dynamic CRP, PCT levels and their clearance in hospitalized CAP outcomes. The low correlations between the two biomarkers and the only moderate prognostic accuracy calls for a head-to-head trial comparing the ability of both markers to monitor the therapeutic effect and to answer the question which marker is superior in the prognosis prediction

Key messages

The dynamic serum CRP and PCT levels have moderate predictive value on the prognosis of hospitalized CAP.

Additional files

Table S1. Viral and bacterial data for patients classified as “definite CAP. (DOCX 13 kb)

Table S2. Comparisons of biomarkers characteristics within pneumonia patients infected by different pathogens. (DOCX 15 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou university but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou university.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Areas under the curve

- CAP

Community-acquired pneumonia

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CRPc

CRP clearance

- PCT

Procalcitonin

- PCTc

PCT clearance

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- VAP

Ventilator- associated pneumonia

- WBC

White blood cell count

Authors’ contributions

SG and XM contributed to designing the study, interpreting data, drafting the manuscript. ML contributed to designing the study, acquisition of and interpreting data and approving the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by local ethics committee. All phases of the study were carried out in conformity with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained according to Chinese law.

Consent for publication

The study was approved by ethic committee of Zhengzhou University. The informed consents were obtained from all subjects or their guardians.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nouvenne A, Ticinesi A, Folesani G, Cerundolo N, Prati B, Morelli I, Guida L, Lauretani F, Maggio M, Aloe R, et al. The association of serum procalcitonin and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein with pneumonia in elderly multimorbid patients with respiratory symptoms: retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:16. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Castillo J, Martin-Sanchez FJ, Llinares P, Menendez R, Mujal A, Navas E, Barberan J, Spanish Society of Emergency M. Emergency C. Spanish Society of G et al. Guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly patient. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2014;27:69–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faverio P, Aliberti S, Bellelli G, Suigo G, Lonni S, Pesci A, Restrepo MI. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng CW, Chien MH, Su SC, Yang SF. New markers in pneumonia. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;419:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agnello L, Bellia C, Di Gangi M, Lo Sasso B, Calvaruso L, Bivona G, Scazzone C, Dones P, Ciaccio M. Utility of serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in severity assessment of community-acquired pneumonia in children. Clin Biochem. 2016;49:47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhydkov A, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, Hoess C, Henzen C, Werner Z, Mueller B, Schuetz P. Pro HSG: Utility of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein and white blood cells alone and in combination for the prediction of clinical outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53:559–566. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habib SF, Mukhtar AM, Abdelreheem HM, Khorshied MM, El Sayed R, Hafez MH, Gouda HM, Ghaith DM, Hasanin AM, Eladawy AS, et al. Diagnostic values of CD64, C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in ventilator-associated pneumonia in adult trauma patients: a pilot study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54:889–895. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballou SP, Kushner I. C-reactive protein and the acute phase response. Adv Intern Med. 1992;37:313–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabral L, Afreixo V, Almeida L, Paiva JA. The use of Procalcitonin (PCT) for diagnosis of Sepsis in burn patients: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan ST, Sun LC, Jia HB, Gao W, Yang JP, Zhang GQ. Procalcitonin levels in bloodstream infections caused by different sources and species of bacteria. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:579–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porfyridis I, Georgiadis G, Vogazianos P, Mitis G, Georgiou A. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, clinical pulmonary infection score, and pneumonia severity scores in nursing home acquired pneumonia. Respir Care. 2014;59:574–581. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steichen O, Bouvard E, Grateau G, Bailleul S, Capeau J, Lefevre G. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin in acutely hospitalized elderly patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1471–1476. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0807-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meili M, Kutz A, Briel M, Christ-Crain M, Bucher HC, Mueller B, Schuetz P. Infection biomarkers in primary care patients with acute respiratory tract infections-comparison of Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:43. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan Faheem, Owens Mark B, Restrepo Marcos, Povoa Pedro, Martin-Loeches Ignacio. Tools for outcome prediction in patients with community acquired pneumonia. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 2016;10(2):201–211. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2017.1268051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yentis SM, Soni N, Sheldon J. C-reactive protein as an indicator of resolution of sepsis in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:602–605. doi: 10.1007/BF01700168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luyt CE, Guerin V, Combes A, Trouillet JL, Ayed SB, Bernard M, Gibert C, Chastre J. Procalcitonin kinetics as a prognostic marker of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:48–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-746OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abula A, Wang Y, Ma L, Yu X. The application value of the procalcitonin clearance rate on therapeutic effect and prognosis of ventilator associated pneumonia. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2014;26:780–784. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang MY, Chen CY, Chien JH, Wu KH, Chang YJ, Wu KH, Wu HP. Serum Procalcitonin and Procalcitonin clearance as a prognostic biomarker in patients with severe Sepsis and septic shock. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1758501. doi: 10.1155/2016/1758501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz-Rodriguez JC, Caballero J, Ruiz-Sanmartin A, Ribas VJ, Perez M, Boveda JL, Rello J. Usefulness of procalcitonin clearance as a prognostic biomarker in septic shock. A prospective pilot study. Med Int. 2012;36:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, Huchon G, Ieven M, Ortqvist A, Schaberg T, Torres A, van der Heijden G, Verheij TJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:1138–1180. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00055705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Principi N, Esposito S, Blasi F, Allegra L. Mowgli study g: role of mycoplasma pneumoniae and chlamydia pneumoniae in children with community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1281–1289. doi: 10.1086/319981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao B, Huang Y, She DY, Cheng QJ, Fan H, Tian XL, Xu JF, Zhang J, Chen Y, Shen N, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Chinese thoracic society, Chinese Medical Association. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:1320–1360. doi: 10.1111/crj.12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, Hanusa BH, Weissfeld LA, Singer DE, Coley CM, Marrie TJ, Kapoor WN. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Bel J, Hausfater P, Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Blanc FX, Benjoar M, Ficko C, Ray P, Choquet C, Duval X, Claessens YE. Group Es: diagnostic accuracy of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in suspected community-acquired pneumonia adults visiting emergency department and having a systematic thoracic CT scan. Crit Care. 2015;19:366. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colak A, Yilmaz C, Toprak B, Aktogu S. Procalcitonin and CRP as biomarkers in discrimination of community-acquired pneumonia and exacerbation of COPD. J Med Biochem. 2017;36:122–126. doi: 10.1515/jomb-2017-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ugajin M, Yamaki K, Hirasawa N, Yagi T. Predictive values of semi-quantitative procalcitonin test and common biomarkers for the clinical outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Care. 2014;59:564–573. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez JF, Sibila O, Restrepo MI. Predicting ICU admission in community-acquired pneumonia: clinical scores and biomarkers. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2012;5:445–458. doi: 10.1586/ecp.12.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim MW, Lim JY, Oh SH. Mortality prediction using serum biomarkers and various clinical risk scales in community-acquired pneumonia. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2017;77:486–492. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2017.1344298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuetz P, Suter-Widmer I, Chaudri A, Christ-Crain M, Zimmerli W, Mueller B. Prognostic value of procalcitonin in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:384–392. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00035610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito A, Ishida T, Tachibana H, Ito Y, Takaiwa T. Serial procalcitonin levels for predicting prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2016;21:1459–1464. doi: 10.1111/resp.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouadma L, Luyt CE, Tubach F, Cracco C, Alvarez A, Schwebel C, Schortgen F, Lasocki S, Veber B, Dehoux M, et al. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients' exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:463–474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61879-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mokart D, Leone M. Procalcitonin in intensive care units: the PRORATA trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Povoa P, Martin-Loeches I, Ramirez P, Bos LD, Esperatti M, Silvestre J, Gili G, Goma G, Berlanga E, Espasa M, et al. Biomarkers kinetics in the assessment of ventilator-associated pneumonia response to antibiotics - results from the BioVAP study. J Crit Care. 2017;41:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Viral and bacterial data for patients classified as “definite CAP. (DOCX 13 kb)

Table S2. Comparisons of biomarkers characteristics within pneumonia patients infected by different pathogens. (DOCX 15 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou university but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of The first affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou university.