Abstract

Background

This research article addresses the relationships among personality, risk perception, and health perception. The personality construct has been one of the main topics of research in psychology throughout history and is understood as the set of traits or cognitive, affective and behavioral characteristics that an individual possesses. Important relationships have been found that show the impact of personality on people’s health as well as the impact of health conditions on the configuration of personality. This research investigates the perception of risk as a mediating trait between personality and perception of health.

Materials and methods

To achieve this, a cross-sectional study was conducted in which 398 Colombians from all regions of the country were evaluated. The NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and Health Risk Perception Test (HRPT) tests were used.

Results

The data were analyzed with multiple regression and path analysis. The findings using multiple regression show that neuroticism and the personal meaning of risk affect the perception of health; however, using path analysis, model fit with the proposed model was not achieved with no mediator effect of perception of risk.

Conclusion

It is necessary to focus on relationships between neuroticism and perception of health in future research.

Keywords: personality, health perception, risk perception, health psychology

Introduction

Perceiving a risk to one’s health is a complex psychological process1 in which the assumption or knowledge of the threat and the personal perception of risk are involved. On the one hand, people can have a personal perception of absolute risk with a double possibility of bias: optimistic or pessimistic. The optimistic bias is an alteration of the comparative risk judgement, is the undervaluation of risk when the risk concerns their selves,2 compared with epidemiological estimates, a person may perceive that they have a greater or lesser probability of being affected by a disease, although this does not correspond to objective data. On the other hand, a person may have a personal perception of comparative risk, based on which, also with an optimistic or pessimistic bias, one’s health risk can be compared with that of one or a group of people.1–4

The configuration of risk perception occurs in all contexts of individual performance, from office work to the practice of extreme sports. However, one of the main contexts for the individual is assumed to be that of health. Risk and the perception of health risk directly address the possibility of physical injury that usually manifests in diseases.5 For example, Peters et al6 show the importance of understanding perceptions of risk and concern regarding health as predictive factors for the execution of preventive actions, specifically to reduce medical errors, although they show that it is the concern factor that functions as the best predictor.

Sjöberg7 defined the perception of risk as the subjective assessment of the probability that a certain type of accident will happen and the level of concern regarding the consequences. “Risk” is only risk to the extent that it is perceived,8 and this perception implies an active commitment to the object, person or situation. This “perception” represents the recognition of the likelihood of injury. This likelihood arises from the acceptance of uncertainty, and the acceptance of the possibility of injury arises to the extent that vulnerability is assumed.9 Vulnerability is the product of an evaluation that takes into account three factors: 1) knowledge about risk; 2) the personal meaning of risk; and 3) management skills. In these three factors, a combination of objective knowledge (information), subjective knowledge (intuition), interests (personal values and motivations) and beliefs (ideas or unconfirmed knowledge) coexist. These components make up the perception of risk.

The perception of risk is a central aspect of theories of health behavior.9 However, it is necessary to investigate specific effects with empirical methods and establish relationships with other variables that are known to affect health and the perception of health, specifically personality, which has an important predictive role in the perception of alterations in health.10

Multiple studies have shown the relationship between the dimensions of the Big Five personality model and the health-disease process.11 Bogg and Roberts12 established that conscientiousness is a central trait in the configuration of health, and Chauvin et al13 showed that there were strong links between risk perception and conscientiousness. It was also found that the trait of agreeableness has no relation with medical problems or the perception of health,14,15 while there is a large amount of supporting evidence showing the relationship between the trait of neuroticism and various health conditions.10,16–19 Furthermore, some studies have established a relationship between extraversion and openness to experience and various health variables,15,18,19 while in others this relationship is unclear or absent.16 Finally, some studies show that the trait of agreeableness is not related to medical problems or the perception of health.14,15

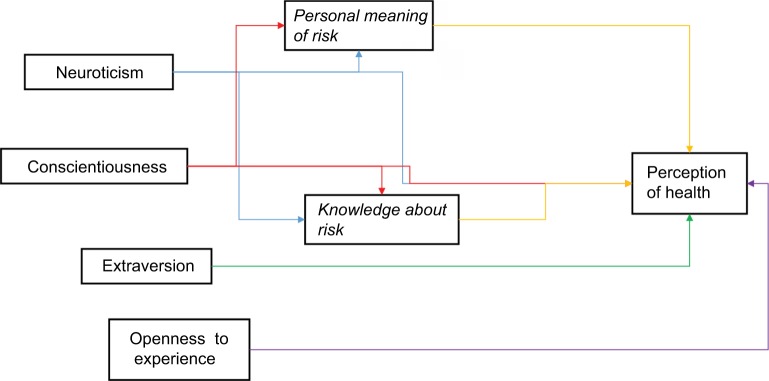

Thus, there is a very strong relationship between the traits of low neuroticism, high extraversion, high openness to experience and high conscientiousness with good perception of health, while the agreeableness factor does not seem to have a consistent relationship with such perception. In addition, there is evidence showing that the perception of risk is a central element in the perception of health, while some findings also indicate links between the factors of neuroticism and conscientiousness and the perception of risk, not the openness to experience or extraversion traits. These relationships are not likely to be linear in nature, as some may act as mediators, so our hypotheses are 1) the personal meaning of risk moderates the relationship between neuroticism, conscientiousness, and perception of health; 2) knowledge about risk moderates the relationship between neuroticism, conscientiousness, and health perception; 3) openness to experience and extraversion are related to the perception of health. This is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed model of relationships among personality, risk perception, and health perception.

Some authors argue that one of the challenges for psychology in the coming years will be to devote more intellectual and empirical work to the study of the positive aspects of human experience in order to understand and strengthen those factors that allow individuals, communities, and societies to thrive, to improve quality of life, and to prevent the pathologies that arise from adverse life conditions.20

Given that personality has an important influence on health perception, mediated by risk perception, verifying the associations between the two variables will allow us to identify the characteristics that represent a risk or protection factor as well as the mediation of the risk perception among these variables, so that they can be managed or modulated to produce positive results with regard to the general welfare of the individual.

Finally, an awareness of personality characteristics, risk perception, and elements associated with health may enable the creation, planning, and implementation of prevention strategies, promotion and intervention in the Colombian population, which could ultimately have a positive impact on general health.

Methodology

Study design

Using a quantitative approach, this research has a transversal design. The method is correlational because it seeks to account for the relationship among personality, risk perception, and health perception.

Population and sample

The population in the present study consists of Colombians living in Medellín and its area of influence as well as migrants from multiple Colombian cities residing in that city. The sample was ultimately composed of 398 people.

The criteria for inclusion of individuals were adults whose age ranged between 18 and 60 years, who were relatively healthy, that is, who did not have chronic or infectious diseases in the acute phase. This project has been approved by the bioethics committee of the Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Colombian regulations, especially Law 1,090 of 2016. All participants were given a copy of the informed consent to be signed, accepting their voluntary participation and the right to withdraw from the study if they wanted to.

Methods of collection and statistical analysis

Instruments

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)

Designed by Goldberg,21 the questionnaire consists of 12 items, of which six are positive sentences and six are negative sentences. The test is interpreted such that a high score shows altered or negative health perception, while a low score indicates an adequate perception of health. The items are answered using a four-point Likert scale (0-1-2-3). The response options used in this study followed the indications of Villa et al.22 For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.775.

NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI)

This is a personality measurement instrument that addresses five factors: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. It is a short version of the NEO-PI that was originally developed in the United States and adapted and validated in different countries of the world. For this study the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are 0.703 for neuroticism, 0.698 for extraversion, 0.621 for openness, 0.624 for agreeableness, and 0.705 for conscientiousness.

Health Risk Perception Test (HRPT)

To measure the perception of risk, an instrument was designed for this study based on three components: risk knowledge, personal meaning of risk, and risk management skills. The 42 items were based on common situations that were established as a risk to health, and the degree to which they represented a risk (none, some, a lot) was investigated on a three-point Likert scale. The reliability of the instrument for risk knowledge was 0.979, for personal meaning of risk 0.973, and for risk management skills 0.980.

Analysis plan

The analysis of the data was carried out using SPSS 24. Correlation analyses were carried out as well as multiple linear regression. A path analysis was also carried out using AMOS, and the standardized least squares method was used.

Results

The personality traits of the sample are similar to those of the general Colombian population, based on the data of Contreras-Torres et al,23 as are the health perception scores.24 Regarding the perception of risk, there are no additional normative data because it is an ad-hoc test (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of personality, perception of health, and perception of risk

| Mean | SD | Colombian mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 22.07 | 6.525 | 21.06 |

| Extraversion | 28.90 | 6.830 | 31.62 |

| Openness to experience | 27.94 | 5.681 | 30.73 |

| Agreeableness | 27.28 | 5.948 | 28.00 |

| Conscientiousness | 31.55 | 6.814 | 30.94 |

| Health perception | 13.98 | 6.561 | 12.41 |

| Knowledge of risk | 88.79 | 26.473 | – |

| Personal meaning of the risk | 86.41 | 28.283 | – |

| Risk management skills | 92.11 | 26.515 | – |

Correlations

Upon observing the relationships between variables, it was found that almost all personality traits correlate significantly with perception of health, with the exception of openness to experience. The findings show that while higher neuroticism scores are linked to a more negative health perception, as extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness scores increase, health perception is more positive. In relation to the risk perception variables, it was found that openness to experience and agreeableness correlate significantly with all of them; openness to experience does so negatively, that is, increasing mental flexibility is correlated with a lower perception of risk; and agreeableness correlates positively, that is, perception of risk increases when agreeableness is higher. For the variable extraversion, a significant relationship only appears with risk management skills and the personal meaning of risk, which indicates that the greater the tendency to seek external stimulation, the greater the perception of risk management and personal involvement. The variables of risk perception and neuroticism did not present any significant relationships. Finally, significant negative correlations were found between perception of health and all the variables of risk perception, which shows that perception of health is worse when perception of risk is higher (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations among personality, perception of risk and perception of health

| Health perception | Knowledge of risk | Personal meaning of the risk | Risk management skills | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 0.239a | −0.049 | −0.012 | −0.095 |

| Extraversion | −0.170a | 0.041 | 0.102b | 0.153a |

| Openness to | −0.024 | −0.137a | −0.167a | −0.116b |

| experience | ||||

| Agreeableness | −0.214a | 0.197a | 0.158a | 0.285a |

| Conscientiousness | −0.160a | 0.015 | −0.011 | 0.067 |

| Health perception | 1 | −0.254a | −0.301a | −0.293a |

Notes:

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Regressions

To prove causal relationships, a multiple regression analysis was carried out with perception of health as the dependent variable. With a statistically significant regression model, it was found that neuroticism and the personal meaning of risk may predict health perception (F [8.389]=9.640, P≤0.000) with an R2 of 0.165. Personal meaning of risk displays negative beta coefficients, which indicates a negative relationship, that is, when scores are high, negative health perception is predicted to be low, namely, there would be an adequate perception of health (Table 3). This is because the interpretation of health perception scores is inversed, as explained in the methodology section.

Table 3.

Regression model of personality and risk perception on health perception

| Coefficientsa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Standardized coefficients

|

t | Sig. | 95% CI for β

|

|

| Beta | Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| (Constant) | 7.386 | 0.000 | 16.392 | 28.285 | |

| Neuroticism | 0.182 | 3.555 | 0.000 | 0.082 | 0.285 |

| Extraversion | −0.045 | −0.876 | 0.382 | −0.141 | 0.054 |

| Openness to experience | −0.043 | −0.869 | 0.385 | −0.162 | 0.063 |

| Agreeableness | −0.086 | −1.656 | 0.098 | −0.208 | 0.018 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.042 | −0.773 | 0.440 | −0.143 | 0.062 |

| Knowledge about risk | 0.019 | 0.202 | 0.840 | −0.042 | 0.051 |

| Personal meaning of risk | −0.272 | −3.064 | 0.002 | −0.104 | −0.023 |

| Skills management of risk | −0.037 | −0.357 | 0.721 | −0.060 | 0.042 |

Note:

Dependent Variable: Health perception.

Path analysis

The asymmetries of all the variables were less than 3, and the kurtosis coefficients of all the variables were less than 8. It was thus evidenced that there was no violation of normality.

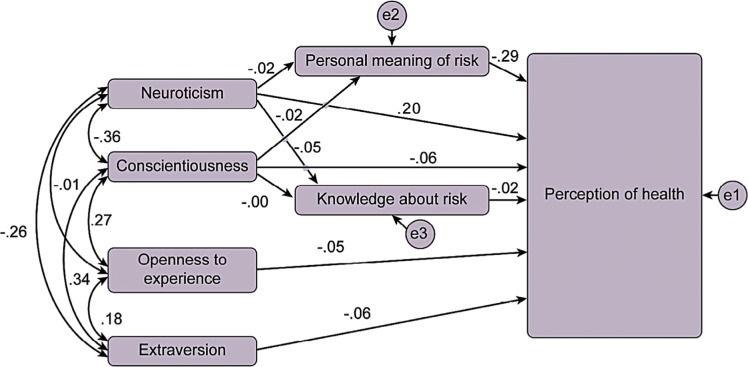

The path coefficients were calculated based on the hypothesized model. The final results are presented in Figure 2. The final model did not exhibit a good fit, with chi-squared =431.219 (df=5, P=0.000), GFI=0.831, AGFI=0.054, NFI=0.340, RFI=−1.773, IFI=0.342, TLI=−1.832, CFI=0.326 and RMSEA=0.463. Neuroticism (b=0.20) and the personal meaning of risk (b=−0.29) had direct effects on the perception of health. The results also showed that conscientiousness (b=−0.36) and extraversion (b=−0.26) had an indirect effect on health perception with the moderation of neuroticism (b=0.20).

Figure 2.

Path analysis of model of relationships among personality, perception of risk and perception of health.

Discussion

The results between neuroticism and negative perception of health are as expected because there is abundant evidence pointing to this relationship, even establishing neuroticism as one of the strongest predictors of health25 and psychological well-being at older ages.15 These findings replicate those of other studies, thus generating more confidence in the conclusions regarding the relationship between neuroticism and health. However, the basis for this relationship is not clear; the strongest hypothesis is that the trait of neuroticism may increase the perception of poor health.14

Our results with regard to the agreeableness trait, which is not related to health perception, are consistent with Goodwyn and Engstrom14 but inconsistent with Olivares-Tirado et al.15 One hypothesis would be that this trait is linked to health in older people but not throughout life, which makes it an element dependent on the life cycle and not on health-disease circumstances.

The extraversion trait does not appear linked to the perception of health, a finding consistent with Chico-Librán,16 although it contradicts other studies.14,15,18,19 These data could suggest that extraversion may play a more important role in the health characteristics that depend more on social relationships (such as certain mental disorders and situations in old age) than on the global perception of health. This may also be the case with regard to the conscientiousness trait.25

The evidence thus points to a single personality trait, neuroticism, as a mediating factor in the perception of health and not as a central factor.26,27 However, a future question to solve would be which facets of this trait would mediate or moderate on health perception.

Neuroticism is linked to the hyper-excitation of the limbic system, which is related to the processing of emotions. Evans et al28 conducted a study on cortisol levels, stress and traits of neuroticism and extraversion in adolescents and found that in people with neuroticism there is greater reactivity of cortisol and physiological stress, while people with high extraversion are less physiologically sensitive to stress, also due to their ability to regulate their emotions, experience positive affect and be less inhibited in social situations. This is what would cause neuroticism to be related to health perception.

When examining the relationships between health perception and risk perception, it was found that only the personal meaning of risk influences the perception of health. This personal meaning involves more affective aspects than the other two variables of risk perception (risk knowledge and management skills). This relationship thus seems to indicate that the most important element in the perception of health risk is the emotional component, while cognitive and procedural aspects may not have an effect on the perception of health. This hypothesis would be in line with the approaches of Brewer et al,9 Ferrer and Klein5 and Peters et al.6

In the present study, the traits of neuroticism and conscientiousness are not significantly related to the variables of risk perception, which is consistent with the findings of Chauvin et al.13 However, the latter study does not have the same risk conceptualization as the present investigation, so the implications of both investigations could differ.

The absence of a link between conscientiousness and the variables of risk perception mentioned could stem from the fact that this personality trait is associated more with following general rules and regulations than with personalized norms or values.13

Regarding neuroticism, it is precisely anxiety that would be at the basis of risk knowledge, as well as the strategies to manage it. Hypothetically, this trait would be compatible with excessive concern regarding multiple aspects that could affect health. These links appear in other studies.7,13,29

The importance of this personality trait is also seen in other studies where personality variables are grouped into prototypes,11 focusing on the importance of the “resilient” prototype characterized by a low neuroticism score.

The clearest outcome of this study is that personality in a multidimensional way is that it seems to be overvalued as a predictor of health, focusing on neuroticism would be more appropriate, at least in the population of this study. Similarly, the consideration of multiple variables of risk perception does not impact the perception of health; rather, the main elements are only the personal and affective involvement in risk.

There are relationships between personality and health perception and between risk perception and health perception, which leads to the understanding that the perception of risk does not seem to mediate between personality and health perception; however, the underlying causes of these relationships are not clear. Nevertheless, it seems that emotional processing is a variable that may streamline the explanation of these relationships; one could even think of the heuristic of affectivity,30,31 an aspect that would share both neuroticism and the personal meaning of risk, so that this heuristic could be the most important factor for work in prevention, promotion and treatment of health-disease.

Hagger-Johnson and Pollard-Whiteman32 questioned the importance and usefulness of the evidence of the relationships between personality and health, although they argued that it was interesting for researchers. Considering these questions, they proposed the working model of the five T’s: 1) targeting; 2) tailoring; 3) training; 4) treatment; and 5) transformation. The first aspect is targeting, the second is tailoring, the third aspect is training, the fourth is treatment, and the last is transformation. Our recommendations would be in line with this proposal.

Despite these findings and the background presented, a lack of experimental studies constitutes a key methodological difficulty. The cross-sectional design is our main limitation, therefore, it is necessary to expand experimental work in personality-risk-health relationships. This would remedy the strong presence of speculation in the recommendations of professionals as well as the rise of pseudoscientific models in the field of health psychology.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Renner B, Gamp M, Schmälzle R, Schupp H. Health risk perception. In: Wright D, editor. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 702–709. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstein ND. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science. 1989;246(4935):1232–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.2686031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renner B, Schupp H. The perception of health risks. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 637–665. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepperd JA, Klein WM, Waters EA, Weinstein ND. Taking stock of unrealistic optimism. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(4):395–411. doi: 10.1177/1745691613485247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrer R, Klein WM. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;5:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters E, Slovic P, Hibbard JH, Tusler M. Why worry? Worry, risk perceptions, and willingness to act to reduce medical errors. Health Psychol. 2006;25(2):144–152. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjöberg L. Distal factors in risk perception. J Risk Res. 2003;6(3):187–211. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slovic P. Perception of risk: reflections on the psychometric paradigm. In: Krimsky SS, Golding D, editors. Social Theories of Risk. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1992. pp. 117–152. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007;26(2):136–145. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orejudo-Hernández S, Froján-Parga MX. Síntomas somáticos: Predicción diferencial a través de variables psicológicas, sociodemográficas, estilos de vida y enfermedades [Somatic symptoms: differential prediction by psychological and sociodemographic variables, lifestyle and diseases] Anales de psicología. 2005;21(2):276–285. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solís-Cámara P, Meda-Lara R, Moreno-Jiménez B, Palomera-Chávez A, Juárez-Rodríguez P. Comparación de la salud subjetiva entre prototipos de personalidad recuperados en población general de México [Comparison of subjective health between personality prototypes extracted from the general population of Mexico] Acta Colombiana de Psicología. 2017;20(2):214–226. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogg T, Roberts BW. The case for conscientiousness: evidence and implications for a personality trait marker of health and longevity. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(3):278–288. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9454-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chauvin B, Hermand D, Mullet E. Risk perception and personality facets. Risk Anal. 2007;27(1):171–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin R, Engstrom G. Personality and the perception of health in the general population. Psychol Med. 2002;32(2):325–332. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701005104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivares-Tirado P, Leyton G, Salazar E. Personality factors and self-perceived health in Chilean elderly population. Health. 2013;5(12):86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chico Librán E. Personality dimensions and subjective well-being. Span J Psychol. 2006;9(1):38–44. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600005953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández JC, Pérez JA, Fernández B. Estudio transversal sobre la relación entre neuroticismo y curso clínico en pacientes con enfermedades inflamatorias intestinales [Cross-sectional study on the relationship between neuroticism and clinical course in patients with inflammatory bowel disease] Clin Salud. 2010;21(1):49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambrano R. Revisión sistemática del Inventario de Personalidad NEO (NEO-PI) [Systematic review of NEO Personality Inventory (NEO–PI)] Psicología desde el Caribe. 2011;27:179–198. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zambrano R. Revisión sistemática del Cuestionario de Personalidad de Eysenck (Eysenck Personality Questionnarie – EPQ) [Systematic review from Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ)] Liberabit. 2011;17(2):147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopkins N, Reicher S. The psychology of health and well-being in mass gatherings: a review and a research agenda. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2016;6(2):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg D. General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER Publishing; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villa I, Zuluaga C, Restrepo L. Propiedades psicométricas de Cuestionario de Salud General de Goldberg GHQ-12 en una institución hospitalaria de la ciudad de Medellín [Psychometric properties of the General Health Goldberg GHQ-12 questionnaire applied at a hospital facility in the city of Medellin] Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana. 2013;31(3):532–545. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contreras-Torres F, Espinosa-Méndez J, Esguerra-Pérez G. Personalidad y afrontamiento en estudiantes universitarios [Personality and coping in college students] Universitas Psychologica. 2009;8(2):311–322. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruiz FJ, García-Beltrán DM, Suárez-Falcón JC. General Health Questionnaire-12 validity in Colombia and factorial equivalence between clinical and nonclinical participants. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duggan KA, Friedman HS, McDevitt EA, Mednick SC. Personality and healthy sleep: the importance of conscientiousness and neuroticism. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srivastava K, Das RC. Personality and health: road to well-being. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24(1):1–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.160905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Restrepo JE. Correlatos cognitivos y neuropsicológicos de los cinco grandes: una revisión en el área de la neurociencia de la personalidad [The big five cognitive and neuropsychological correlates: a review in the field of neuroscience of personality] Pensando Psicología. 2015;11(18):107–127. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans BE, Stam J, Huizink AC, et al. Neuroticism and extraversion in relation to physiological stress reactivity during adolescence. Biol Psychol. 2016;117:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouyer M, Bagdassarian S, Chaabanne S, Mullet E. Personality correlates of risk perception. Risk Anal. 2001;21(3):457–466. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.213125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slovic P, Finucane M, Peters E, MacGregor D. The affect heuristic. Eur J Oper Res. 2007;177:1333–1352. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML, MacGregor DG. Affect, risk, and decision making. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4 Suppl):S35–S40. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagger-Johnson G, Pollard-Whiteman M. Personality and health − so what? Psychologist. 2008;21:594–597. [Google Scholar]