Abstract

Background

Nanoparticulate titanium dioxide (nano-TiO2) enters the body through various routes and causes organ damage. Exposure to nano-TiO2 is reported to cause testicular injury in mice or rats and decrease testosterone synthesis, sperm number, and motility. Importantly, nano-TiO2 suppresses testosterone production by Leydig cells (LCs) and impairs the reproductive capacity of animals.

Methods

In an attempt to establish the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of nano-TiO2 on testosterone synthesis, primary cultured rat LCs were exposed to varying concentrations of nano-TiO2 (0, 10, 20, and 40 µg/mL) for 24 hours, and alterations in cell viability, cell injury, testosterone production, testosterone-related factors (StAR, 3βHSD, P450scc, SR-BI, and DAX1), and signaling molecules (ERK1/2, PKA, and PKC) were investigated.

Results

The data show that nano-TiO2 crosses the membrane into the cytoplasm or nucleus, triggering cellular vacuolization and nuclear condensation. LC viability decreased in a time-dependent manner at the same nano-TiO2 concentration, nano-TiO2 treatment (10, 20, and 40 µg/mL) decreased MMP (36.13%, 45.26%, and 79.63%), testosterone levels (11.40% and 44.93%), StAR (14.7%, 44.11%, and 72.05%), 3βHSD (26.56%, 50%, and 79.69%), pERK1/2 (27.83%, 63.61%, and 78.89%), PKA (47.26%, 70.54%, and 85.61%), PKC (30%, 50%, and 71%), SR-BI (16.41%, 41.79%, and 67.16%), and P450scc (39.41%, 55.26%, and 86.84%), and upregulated DAX1 (1.31-, 1.63-, and 3.18-fold) in primary cultured rat LCs.

Conclusion

Our collective findings indicated that nano-TiO2-mediated suppression of testosterone in LCs was associated with regulation of ERK1/2–PKA–PKC signaling pathways.

Keywords: nanoparticulate titanium dioxide, primary cultured rat Leydig cells, mitochondrial injury, testosterone, ERK1/2-PKA-PKC signaling pathways

Introduction

Nanoparticulate titanium dioxide (nano-TiO2) is characterized by a large surface-area ratio, strong mechanical properties, low melting point, and magnetism. The compound has numerous applications in industry, coating systems, medicine, everyday lives, and the environment.1–6 Due to its widespread usage and specific physical and chemical properties,7 nano-TiO2 is transferred to the human body through various routes, including inhalation, environmental intake (food additives or packaging components), and biomedical applications (gastrointestinal absorption or skin exposure),1,6,8 and subsequently travels through the blood circulation into the liver, brain, spleen, heart, kidneys, lungs, and ovaries.3,9–12 We have reported nano-TiO2 deposition in various organs of mice after exposure for 14 consecutive days in the following order: liver > kidney > spleen > lung > brain > heart.13 Nano-TiO2 has additionally been shown to enter the testis through the blood–testis barrier and migrate to the testicular microenvironment composed of Sertoli cells, spermatids, and Leydig cells (LCs),14–16 leading to inhibition of >90% testosterone production, spermatozoa degeneration, and consequent reduction in LCs and sperm number, sperm motility, and male fertility.17–25 However, the mechanisms underlying the suppressive effects of nano-TiO2 on testosterone production are yet to be established.8,26

Testosterone synthesis is a complex process in which cholestenone is transferred from the cytoplasm to mitochondria via StAR, followed by acceleration of the cholesterol side-chain-cleavage process via the P450scc enzyme in LCs. Cholestenone is metabolized to pregnenolone, and subsequently testosterone is generated through a reaction catalyzed by 3βHSD and 17βHSD.27 StAR plays an important role in testosterone synthesis,28 and is regulated by ERK1/2. Association of the MAPK–ERK signaling cascade with steroid biosynthesis is suggested through regulation of StAR expression via multiple pathways and factors in mouse LCs.29 ERK1/2 exerts stimulatory effects on steroidogenesis.30 StAR modulates the transfer of cholesterol from the cytoplasm to mitochondria, regarded as the rate-limiting step in steroid-hormone synthesis.31–36 Limited studies to date have focused on the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of nano-TiO2 on testosterone generation.

Here, we hypothesized that inhibition of testosterone biosynthesis by nano-TiO2 is achieved by regulation of testosterone-related factors through the ERK1/2–PKA–PKC signaling pathways in LCs. To examine this theory, rat primary cultured LCs were exposed to different concentrations of nano-TiO2, and changes in mitochondrial membrane potential and testosterone secretion were detected to evaluate the effects on cell viability, ultrastructure, and function. We additionally examined the effects of nano-TiO2 on expression of proteins involved in testosterone generation, including StAR, 3βHSD, P450scc, SR-BI, and DAX1, and signaling molecules, such as ERK1/2, pERK1/2, PKA, and PKC, and whether the ERK1/2–PKA–PKC pathways participate in nano-TiO2-mediated impairment of testosterone generation in LCs.

Methods

Chemicals

Nano-TiO2 (anatase type, TiO2 content >99.5%) was kindly provided by Professor Yang Ping (College of Chemistry, Soochow University, China) and characterized according to previous reports.37,38 Nano-TiO2 powder was dispersed in DMEM and Ham’s F12 nutrient mixture (DMEM-F12; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) containing 10% PBS (Solarbio, Beijing, China), following which the suspensions (5 mg/L) were treated ultrasonically for 30 minutes and mechanically vibrated for 5 minutes. Particle sizes of nano-TiO2 suspended in DMEM-F12 were determined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Tecnai G2 Spirit; FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operating at 100 kV. In brief, suspended nano-TiO2 particles were deposited onto carbon-film TEM grids and allowed to dry in air. Mean particle size was determined by measuring more than 100 individual particles that were randomly sampled. X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained at room temperature with diffractometry (Mercury; Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK) using Ni-filtered CuK radiation. The surface area of each sample was determined via Brunauer–Emmett–Teller adsorption measurements on an ASAP 2020 instrument (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). Hydrodynamic diameter distribution of nano-TiO2 suspended in DMEM-F12 solution (5 mg/mL) was measured via dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano ZS90; Malvern Instruments, Malvern, England) and ζ-potential detected via analysis with 173° backscatter and MPT2 autotitration (Zetasizer Nano ZS90).

Primary culture of LCs

All rats were purchased from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Soochow University. All animal experiments were conducted during the light phase and approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Soochow University (ethical approval 2111270). Procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Sprague Dawley male rats were housed in stainless-steel cages in a ventilated animal room in specific-pathogen-free conditions in which the temperature was strictly controlled at 18°C–25°C, humidity maintained at 50%–80%, and the room was on a 12-hour light–dark cycle. Both distilled water and sterilized food were allowed freely. After three weeks, testes were collected from male Sprague Dawley rats. LCs were isolated and cultured as described previously.39

Briefly, rats were killed via cervical dislocation and the abdominal cavity cut open to obtain the testes, followed by washing twice in precooled HBSS. Next, capsules and blood vessels were simultaneously stripped. Decapsulated testes were digested enzymatically in DMEM-F12 (HyClone; Sigma-Aldrich) containing 0.25 mg/mL collagenase (type I; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in a shaking water bath (80 cycles/minute). After 20 minutes, 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was added to terminate the digestion reaction and incubated for 10 minutes, causing seminiferous tubules to settle down under gravity. The supernatant containing LCs was collected and incubated for another 10 minutes. Two collected supernatant fractions were passed through a 70 µm cell strainer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove small tubular fragments and the filtrate centrifuged for 10 minutes under 280× g at room temperature. The fluid was removed and washed once with PBS (Solarbio). For purification, cells were added slowly to contain gradients of 30%, 40%, 60%, and 90% Percoll and centrifuged at 180× g for 30 minutes. The third layer of liquid was removed, resus-pended in DMEM-F12 containing 10% FBS, and seeded in six-well plates on glass coverslips at a density of 106 cells/well, followed by treatment with different nano-TiO2 concentrations (0, 10, 20, and 40 µg/mL). LC culture medium containing nano-TiO2 was prepared by nano-TiO2 powder being dispersed in DMEM-F12 with 10% PBS (Solarbio) solution, followed by ultrasonic treatment for 30 minutes and mechanical vibration for 5 minutes. LCs were cultured in vitro and maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. After 24 hours, cells were used for subsequent experiments.

CCK8 assay

The CCK8 assay (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) is used widely to examine cell viability and proliferation. LC activity was determined using the CCK8 and a nano-TiO2-concentration gradient (0, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 120 µg/mL) set over a time course of 12, 24, or 48 hours. Three blanks and five experimental groups were set up for each nano-TiO2 concentration. LCs were plated in 96-well culture plates at a density of 105 cells/well in 100 µL medium and 100 µL CCK8 added to each well for both experimental and blank groups. After 2-hour incubation at 5% CO2 and 37°C, a microplate reader was used to assess the OD450. LC50 was calculated based on: cell viability = (ODexperimental − ODblank wells)/(ODcontrol − ODblank). To ensure appropriate nano-TiO2 concentration within the suspension, ultrasonic treatment was performed for 30 minutes, followed by mechanical vibration for 5 minutes.

Nano-TiO2 internalization

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–nano-TiO2 was produced according to a previously reported method.40 Briefly, FITC-nano-TiO2 was prepared and added to cells at various concentrations (0, 10, or 40 µg/mL) for 24 hours after further selective staining of the cell skeleton and nuclei using rhodamine phalloidin and DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Cells were observed under laser-scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM; FV1200; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Next, cells were washed with PBS three times in the dark to remove FITC-labeled nano-TiO2, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 37°C for 30 minutes, and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100. After 10 minutes, cells were washed three times with PBS. To stain the cell skeleton, 100 nM rhodamine phalloidin was added and DAPI labeling performed for nuclear staining after 30 minutes. Internalization of nano-TiO2 in LCs was observed using LSCM.

Observation of LC ultrastructure

Following treatment with 10, 20, or 40 µg/mL nano-TiO2 for 24 hours, primary cultured LCs were fixed in a fresh solution of 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% formaldehyde, followed by 2-hour fixation at 48°C with 1% osmium tetroxide in 50 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 7.2–7.4). Staining was performed overnight with 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate. Specimens were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (75%, 85%, 95%, and 100%) and embedded in Epon 812. Ultrathin sections were obtained, contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and observed via TEM with a Hitachi H600. LC apoptosis was determined based on changes in morphology.

Assay of mitochondrial membrane potential

After treatment with different nano-TiO2 concentrations for 24 hours, an mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)-assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology) was used to measure MMP of primary cultured LCs via flow cytometry (FACSVerse; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).41 The MMP-assay kit contains 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanine iodide (JC-1), an ideal voltage-sensitive fluorescence probe that displays dual fluorescence and mitochondrial membrane permeability and passively enters mitochondria to form aggregates, leading to red fluorescence. Upon collapse of mitochondrial potential, the dye no longer accumulates in mitochondria and remains in the cytoplasm in the form of a monomer displaying green fluorescence. For the MMP assay, LCs (105 cells/well) were harvested, washed with PBS, and incubated with 10 µM JC-1 dye in culture medium for 15 minutes at 37°C. Cells were rewashed with PBS and resuspended in 400 µL PBS. At high MMP, the JC-1 polymer accumulates in the matrix and shows red fluorescence with excitation at 585 nm and emission at 590 nm. Conversely, under conditions of low MMP, green fluorescence (representing monomer) is evident with excitation at 514 nm and emission at 530 nm, owing to shortage of the JC-1 polymer in the matrix. The ratio of mitochondrial depolarization is measured based on the relative proportion of JC-1 polymer:monomer.

Measurement of testosterone levels

After treatment with different nano-TiO2 concentrations for 24 hours, testosterone levels in cell-culture supernatants were determined with a rat testosterone kit (Yaunye Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After subtraction of baseline testosterone data before exposure to nano-TiO2, resultant data are represented as data processed by nano-TiO2. Testosterone values for five sets of replicates were acquired and averaged.

Immunocytochemistry analysis

To assess expression levels of ERK1/2–PKA–PKC pathway-related proteins, immunocytochemistry was performed. After exposure to nano-TiO2, a clean poly-l-lysine-coated glass slide containing primary cultured LCs was washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio) for 30 minutes at 4°C, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Solarbio) in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cells were blocked with 5% BSA (BBI Life Sciences, Shanghai, China) for 1 hour, rewashed with PBS, and incubated with primary antibodies against ERK1/2 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), pERK1/2 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific), PKA (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific), or PKC (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 hours at room temperature. Cells were subsequently incubated with FITC-conjugated antirabbit IgG (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. After rewashing of slides, protein expression was examined via LSCM (FV1200) and data analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0.

Western blotting

After treatment of cells with different nano-TiO2 concentrations for 24 hours, expressions of ERK1/2, pERK1/2, PKA, PKC, 3βHSD, StAR, P450scc, SR-BI, and DAX1 proteins were detected via Western blotting. Briefly, after being washed with precooled PBS three times to remove dead cells and nano-TiO2, primary cultured LCs were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation-assay buffer including protease and phosphatase inhibitors at 4°C for 40 minutes. Total proteins were obtained by 138,000× g centrifugation at 4°C for 5 minutes and protein concentrations measured using a BCA-assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein were loaded for each sample, separated via 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis, and transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose membranes under a constant current of 300 mA for 2 hours. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (BBI Life Sciences) diluted with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) at room temperature for 2 hours, followed by treatment with anti-ERK1/2 (1:2,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-pERK1/2 (1:2,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-PKA (1:1,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-PKC (1:1,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-3βHSD (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-StAR (1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-P450scc (1:1,000; Abcam), anti-SR-BI (1:2,000; Abcam), anti-DAX1, and anti-β-actin (reference, 1:5,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted with PBST at 4°C overnight. After three washes in PBST, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP (1:5,000) at room temperature for 2 hours. Immunoreactive signals were detected via enhanced chemiluminescence and visualized using X-rays. Finally, images were analyzed using ImageJ to obtain gray values of protein expression for further comparison. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Statistical analysis

All results were based on at least three replicate experiments (five or more repetitions for each treated group) and are expressed as mean ± SD. SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was applied to analyze multigroup data. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate statistical significance. Data were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

Nano-TiO2 characteristics

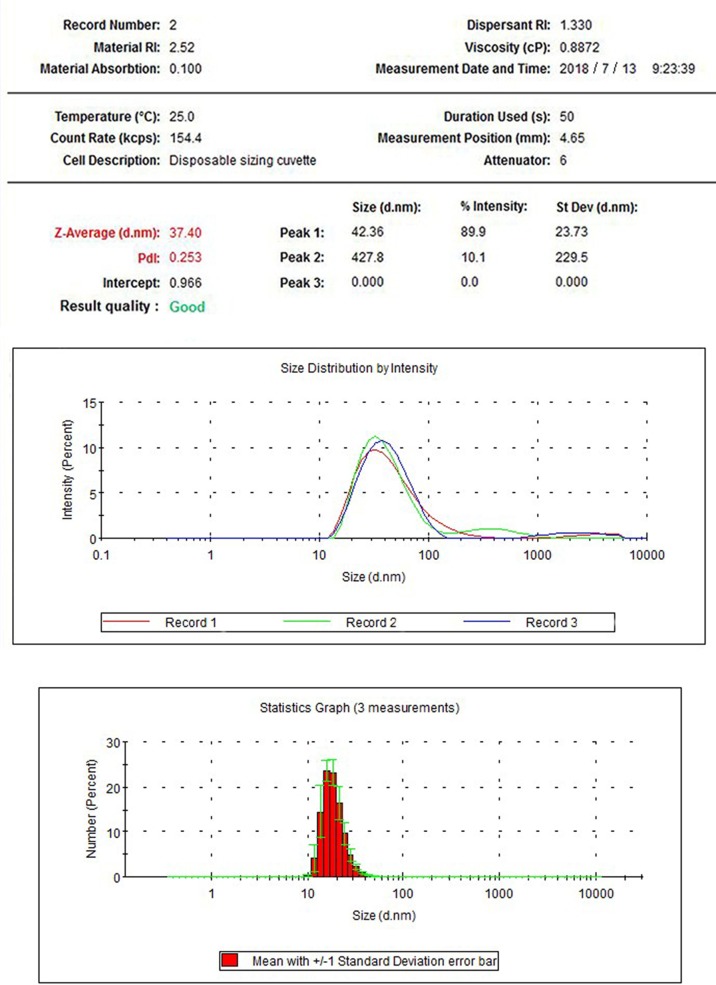

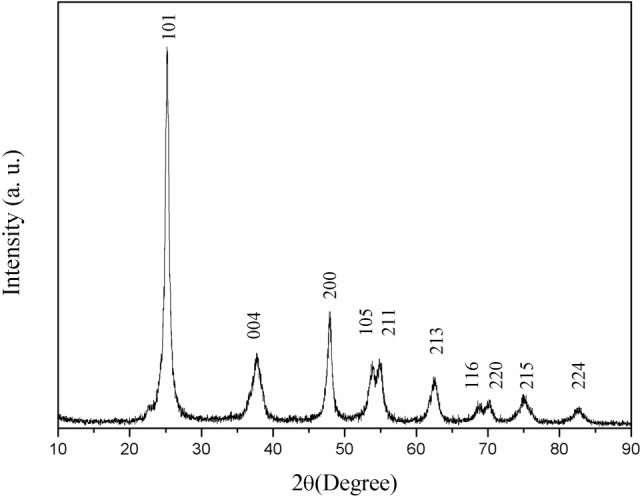

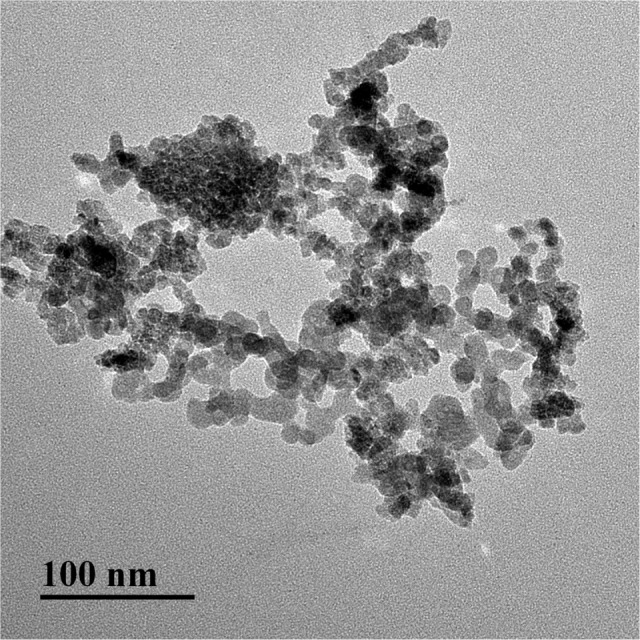

X-ray-diffraction patterns of nano-TiO2 and its phase (101 peak) attributable to the anatase structure are presented in Figure 1. The average size of nano-TiO2 suspended in DMEM-F12 was determined aŝ6.5 nm via TEM (Figure 2). The mean hydrodynamic diameter of nano-TiO2 in DMEM-F12 was 42.36 nm, suggesting that the majority of nano-particles formed clusters and aggregated in the medium (Figure 3). The ζ-potential of nano-TiO2 in DMEM-F12 was 42.8 mV, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 1.

(101) X-ray diffraction peak of nanoparticulate TiO2, showing anatase structure.

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopy images of anatase nanoparticulate TiO2. Nanoparticulates suspended in DMEM-F12 were 6–7 nm in size.

Figure 3.

Hydrodynamic diameter distribution of nanoparticulate TiO2 in DMEM-F12, showing diameter of 338.9 nm and aggregation of the nanoparticles in medium.

Abbreviations: RI, refractive index; PdI, polymer dispersity index.

Figure 4.

ζ-Potential of nanoparticulate TiO2 in DMEM-F12 of 0.136 mV.

Abbreviation: RI, refractive index.

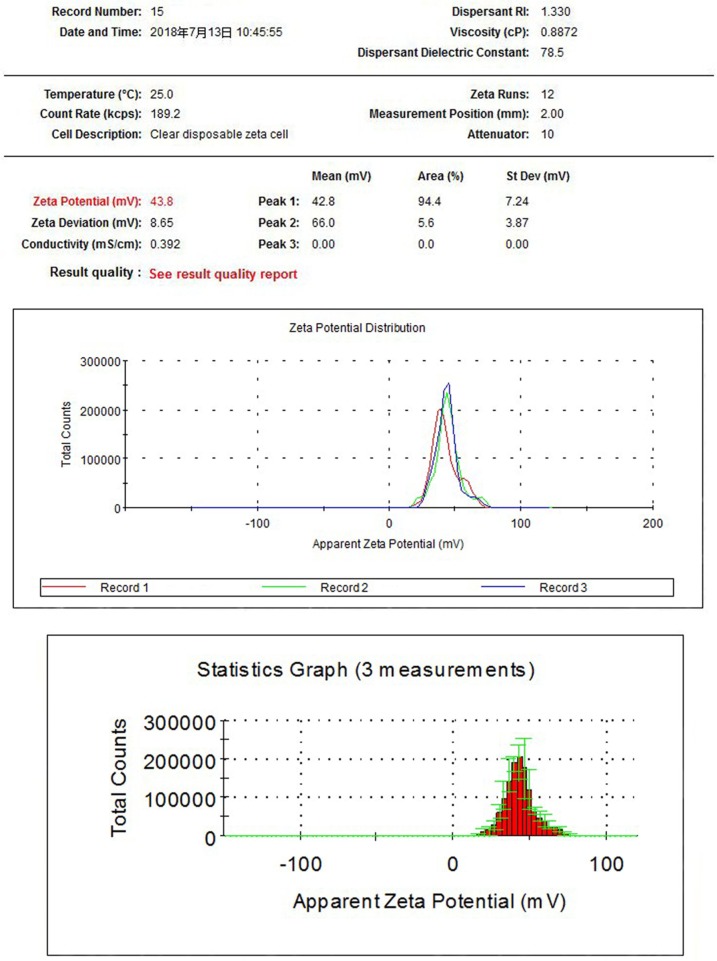

Purity of primary LCs

The purity of primary cultured rat LCs, determined based on immunostaining with 3βHSD, was 95% (n=200; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Identification of primary cultured Leydig cells (LCs).

Notes: LCs were characterized via immunochemistry for 3βHSD (an LC-specific protein). (A) Optical microscopy and (B) fluorescence microscopy showing 95% purity of primary cultured rat LCs.

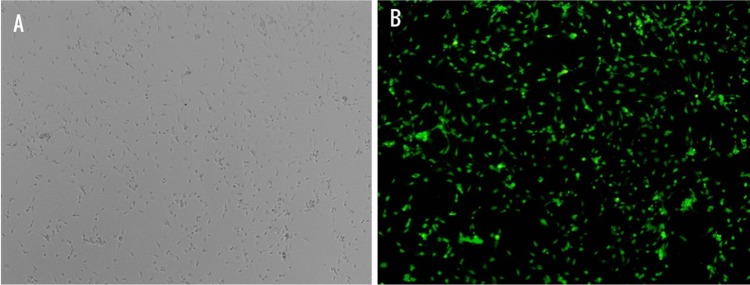

Cell viability

We examined the viability of LCs treated with nano-TiO2 at different concentrations and time points (Figure 6). Notably, LC viability decreased in a time-dependent manner at the same nano-TiO2 concentration (P<0.05). Upon exposure of LCs to different doses of nano-TiO2 (5, 7.5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 120 µg/mL) for 12, 24, and 48 hours, LC50 values of 76.08, 53.96, and 21.45 µg/mL were obtained, respectively. Based on these values, LCs were treated with 10, 20, or 40 µg/mL nano-TiO2 for 24 hours in subsequent experiments.

Figure 6.

Effects of nanoparticulate TiO2 on viability of primary cultured rat Leydig cells.

Notes: The data show reduction of Leydig-cell viability in a time-dependent manner at the same nanoparticulate TiO2 concentration. Values represent mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

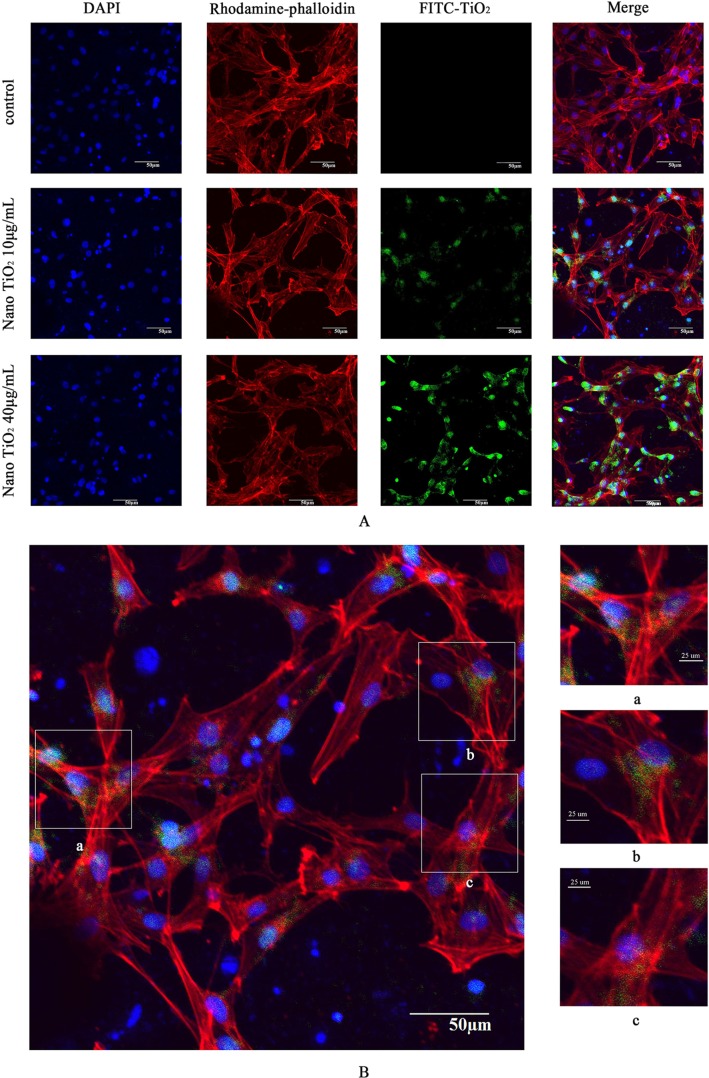

Nano-TiO2 internalization

To explore the potential toxicity of nano-TiO2 to cells and further clarify the distribution in LCs, nanoparticles were labeled with FITC, the cell skeleton with rhodaminephalloidin, and nuclei with DAPI. Owing to its small size, nano-TiO2 readily entered the cytoplasm and nuclei of cells (Figure 7). Experiments with different concentrations of nano-TiO2 revealed that at a treatment dose of 40 µg/mL, a higher number of particles entered nuclei relative to treatment with 10 µg/mL nano-TiO2.

Figure 7.

Confocal microscopy images of primary cultured rat LCs: cell nuclei (blue); F-actin cytoskeleton network (red); and FITC–nano-TiO2 (green).

Notes: (A) LCs were treated with 0, 10, and 40 µg/mL FITC–nano-TiO2 for 24 hours. (B) After treatment of LCs with 10 µg/mL FITC–nano-TiO2 for 24 hours, nanoparticles were distributed in the F-actin cytoskeleton network. (C) After treatment with 40 µg/mL FITC–nano-TiO2 for 24 hours, nanoparticles were distributed in both the F-actin cytoskeleton network and nuclei of LCs, indicating entry into both cytoplasm and nuclei.

Abbreviations: LCs, Leydig cells; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; nano-TiO2, nanoparticulate TiO2.

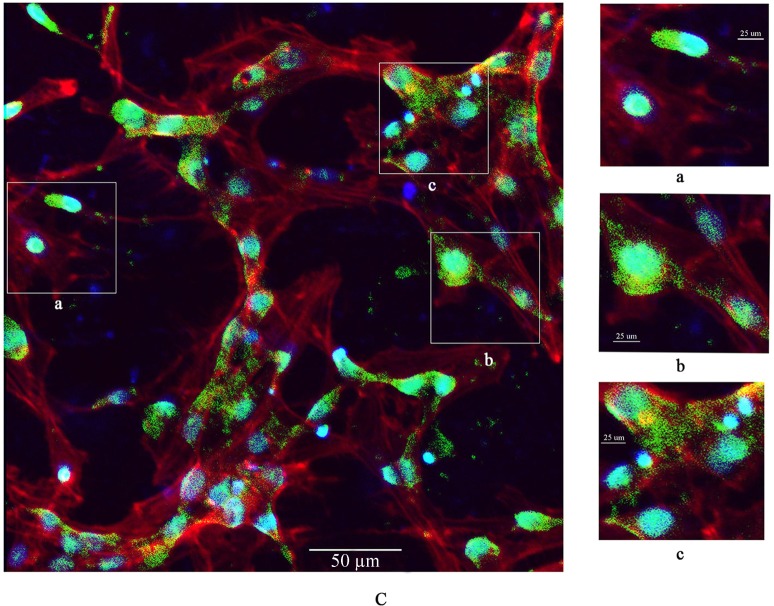

Ultrastructural changes induced by nano-TiO2

Changes in the primary cultured LC ultrastructure are depicted in Figure 8. LCs of the control group exhibited normal architecture, while cellular vacuolization and nuclear condensation were evident in cells treated with nano-TiO2. Significant nano-TiO2 deposition was observed in the cytoplasm of treated LCs, clearly suggestive of cellular entry.

Figure 8.

Effects of nanoparticulate TiO2 (nano-TiO2) on apoptosis of primary cultured Leydig cells (LCs).

Note: Yellow ovals represent deposition of nano-TiO2 particles, signifying accumulation in cytoplasm and LC injury.

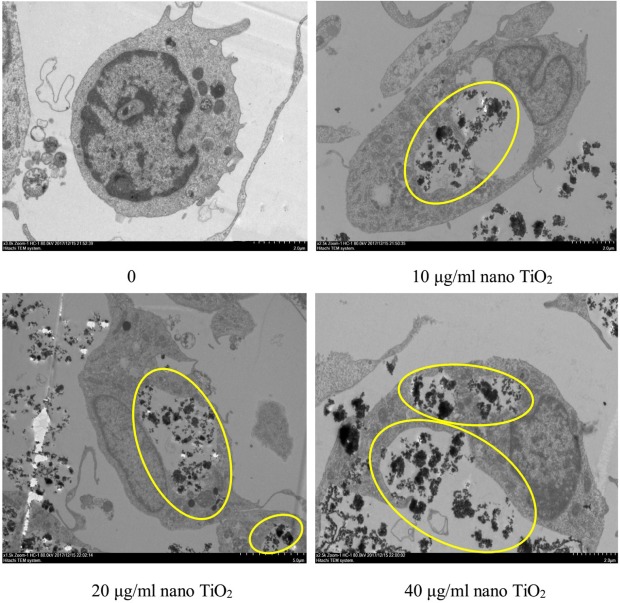

MMP assays

MMP decrease is a marker of mitochondrial damage. Accordingly, to establish whether mitochondrial damage was caused by nano-TiO2, flow cytometry was employed to examine potential changes in MMP. Notably, compared with the control group, MMP of the different nanoparticle-treated groups (10, 20, and 40 µg/mL) decreased by 36.13%, 45.26%, and 79.63%, respectively (P<0.05; Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Effects of nano-TiO2 on MMP in primary cultured LCs.

Notes: (A) Flow-cytometry images of mitochondrial injury in LCs treated with different nano-TiO2 concentrations. (B) MMP levels calculated as JC-1 polymer vs JC-1 monomer in LCs treated with different nano-TiO2 concentrations (***P<0.001). MMP reduction in LCs was observed in the presence of nano-TiO2. Values represent means ± SD (n=5).

Abbreviations: JC-1, 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-imidacarbocyanine iodide; LCs, Leydig cells; nano-TiO2, nanoparticulate TiO2; UL, upper left; UR, upper right; LL, lower left; LR, lower right; PE, P-phycoerythrin; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential.

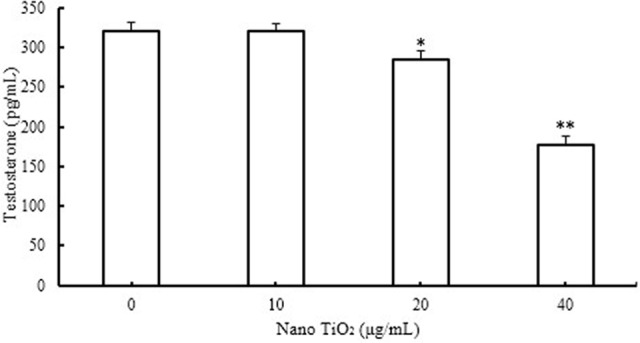

Effects of nano-TiO2 on testosterone levels

Testosterone content was not significantly altered in the presence of 10 µg/mL nano-TiO2, as shown in Figure 10. However, in groups treated with 20 and 40 µg/mL nano-TiO2, testosterone levels were markedly decreased by 11.40% and 44.93%, respectively, compared with the control group (P<0.05).

Figure 10.

Effects of nano-TiO2 on testosterone level in LCs (*P<0.05 and **P<0.01).

Notes: Testosterone production in LCs was suppressed in the presence of nano-TiO2. Values represent mean ± SD (n=5).

Abbreviations: LCs, Leydig cells; nano-TiO2, nanoparticulate TiO2.

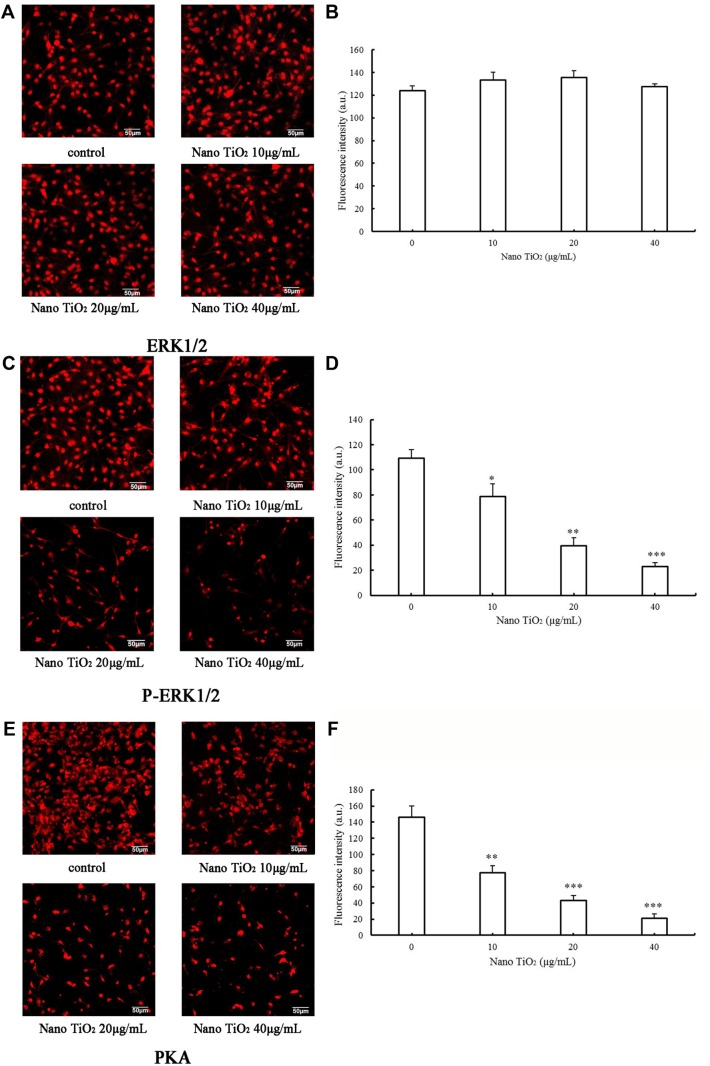

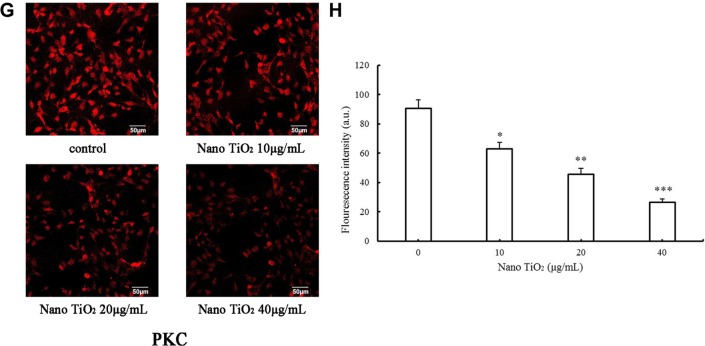

Assay of proteins involved in the ERK1/2-signaling pathway

To determine the effects of nano-TiO2 on ERK1/2 signaling, pathway-related protein expression was measured via immunocytochemistry and Western blot (Figures 11 and 12). In the presence of increasing nano-TiO2 concentrations (10, 20, and 40 µg/mL), the expression of specific proteins was remarkably altered, with decreases of 27.83% in Figure 11 (5.95% in Figure 12), 63.61% in Figure 11 (37.93% in Figure 12), and 78.89% in Figure 11 (55.53% in Figure 12), respectively, for pERK1/2, 47.26% in Figure 11 (13.75% in Figure 12), 70.54% in Figure 11 (19.89% in Figure 12), and 85.61% in Figure 11 (65.69% in Figure 12), respectively, for PKA, and 30% in Figure 11 (22.07% in Figure 12), 50% in Figure 11 (40.57% in Figure 12), and 71% in Figure 11 (56.55% in Figure 12), respectively, for PKC compared to the control group. In contrast, the total ERK1/2 level was not significantly affected by nano-TiO2 (Figure 11A and B).

Figure 11.

Effects of nano-TiO2 on ERK1/2 signaling pathway-related proteins involved in testosterone synthesis in primary cultured rat LCs for 24 hours determined via ICC.

Notes: (A) Representative result determined via ICC of ERK1/2 in LCs. (B) Fluorescence intensity of ERK1/2 in LCs (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001). (C) Representative result determined via ICC of pERK1/2 in LCs. (D) The fluorescence intensity of pERK1/2 in LCs (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001). (E) Representative result determined via ICC of PKA in LCs. (F) Fluorescence intensity of PKA in LCs (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001). (G) Representative result determined via ICC of PKC in LCs. (H) Fluorescence intensity of PKC in LCs (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001). Results, presented as mean ± SD (n=5), clearly indicate dysfunction of the ERK1/2 pathway in LCs treated with nano-TiO2.

Abbreviations: ICC, immunocytochemistry; LCs, Leydig cells; nano-TiO2, nanoparticulate TiO2.

Figure 12.

Effects of nano-TiO2 on ERK1/2 signaling pathway-related proteins involved in testosterone synthesis in primary cultured rat LCs for 24 hours determined via Western blotting.

Notes: (A) Representative Western blots of proteins in LCs. (B) Integrated value of pERK1/2/ERK1/2 from representative blots of proteins in LCs (*P<0.05 and ***P<0.001). (C) β-Actin density values from representative blots of proteins in LCs (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001). Consistent with ICC data, the results support dysfunction of the ERK1/2 pathway in LCs treated with nano-TiO2. Values represent mean ± SD (n=5).

Abbreviations: LCs, Leydig cells; nano-TiO2, nanoparticulate TiO2; ICC, immunocytochemistry.

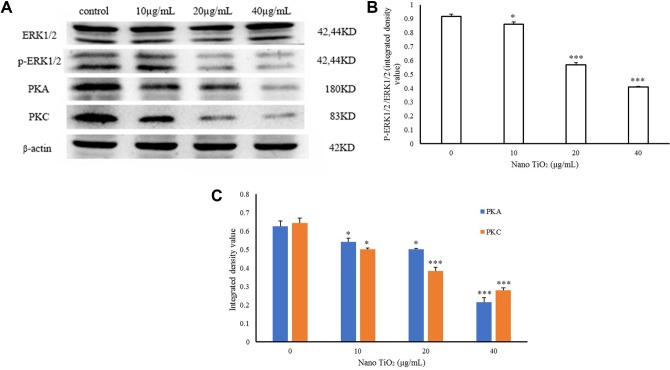

Effects of TiO2 on expression of testosterone-related proteins

The effects of nano-TiO2 on 3βHSD, StAR, P450scc, SR-BI, and DAX1 proteins in primary cultured rat LCs are shown in Figure 13. In the presence of increasing nano-TiO2 concentrations (10, 20, and 40 µg/mL nano-TiO2), significant alterations in protein expression were observed, with reductions of 26.56%, 50%, and 79.69% (Figure 13B), respectively, for 3βHSD, 14.7%, 44.11%, and 72.05% (Figure 13B), respectively, for StAR, 39.41%, 55.26%, and 86.84% (Figure 13B), respectively, for P450scc, and 16.41%, 41.79%, and 67.16% (Figure 13B), respectively, for SR-BI, along with 1.31-, 1.63-, and 3.18-fold increase (Figure 13B), respectively, in DAX1 expression.

Figure 13.

Effects of nano-TiO2 on proteins involved in testosterone synthesis in primary cultured rat LCs for 24 hours.

Notes: (A) Representative Western blots of proteins in LCs. (B) β-Actin density values from representative blots of proteins in LCs (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001). The results indicate impairment of testosterone synthesis in LCs due to nano-TiO2. Values represent mean ± SD (n=5).

Abbreviations: LCs, Leydig cells; nano-TiO2, nanoparticulate TiO2.

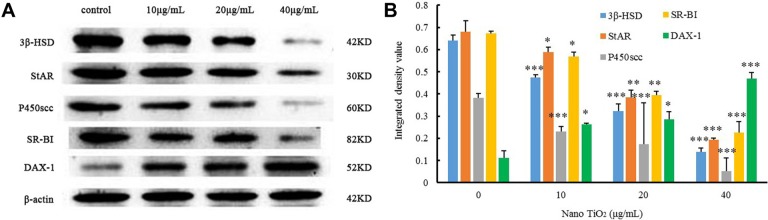

Discussion

Our experiments clearly demonstrated that nano-TiO2 reduced the activity of primary cultured rat LCs (Figure 6), entered the cytoplasm and nuclei of cells (Figures 7 and 8), and caused mitochondrial membrane injury (Figure 9), consistent with results obtained with primary cultured mouse or rat Sertoli cells.42,43 Simultaneously, testosterone production in LCs was significantly lowered following nano-TiO2 treatment (Figure 10). Mitochondrial damage is associated with dysfunction of LCs, which are involved mainly in the production and secretion of testosterone.32,33 Dysfunction of primary cultured rat LCs induced by nano-TiO2 may be triggered via downregulation of ERK-pathway-related factor proteins, such as pERK1/2, PKA, and PKC (Figures 11C–H and 12C), steroidogenic factor proteins, such as StAR, 3βHSD, P450scc, and SR-BI, and concomitant upregulation of DAX1 (Figure 13).

LCs distributed in loose connective tissue between seminiferous tubules are the major androgen-producing cells that maintain normal male development and reproductive function.24,44–46 The main function of testes is to produce sperm and synthesize androgens, the former within spermatocytes and the latter in LCs. Testosterone, a major component of androgens, is essential for expression of the male phenotype. The hormone is transported to target organs throughout the body and contributes to important physiological functions via binding to receptors, such as emergence of secondary sexual characteristics in males and protein synthesis of reproductive organs. Testosterone defi-ciency caused by exposure to nano-TiO2 directly triggers an imbalance in androgen:estrogen ratio, testicular dysfunction, inhibition of sexual differentiation, and spermatogenesis, ultimately leading to decreased sperm number and quality and fertility injuries.9,16,20–22,47,48 Therefore, impairment of male mouse or rat fertility and serum testosterone levels by nano-TiO2 is proposed to be closely associated with suppression of LC testosterone production.

Testosterone synthesis and secretion are mediated by StAR, 3βHSD, P450scc, SR-BI, and DAX1 in LCs. In brief, cholesterol is transported from the outer to inner mitochondrial membrane through StAR. After a series of enzymatic reactions, cholesterol is bioconverted into pregnenolone by P450scc in LCs, which is further transformed into progesterone by 3βHSD, and then into testosterone.34,49 SR-BI functions to maintain high levels of free cholesterol in the mitochondria and supports constitutive steroid-hormone synthesis,50 and reduction in steroid-hormone production results from lack of cholesterol substrate via suppression of SR-BI.29 DAX1, a regulator of multiple steps in the steroidogenic cascade, also suppresses the expression of several proteins and enzymes involved in steroidogenesis, including StAR, P450scc, 3βHSD, and 17β-hydroxylase (CYP17), in LCs.33,51 Accordingly, nano-TiO2-induced upregulation of DAX1 expression may contribute to downregulation of StAR, 3βHSD, P450scc, and SR-BI, in turn reducing testosterone production in LCs.

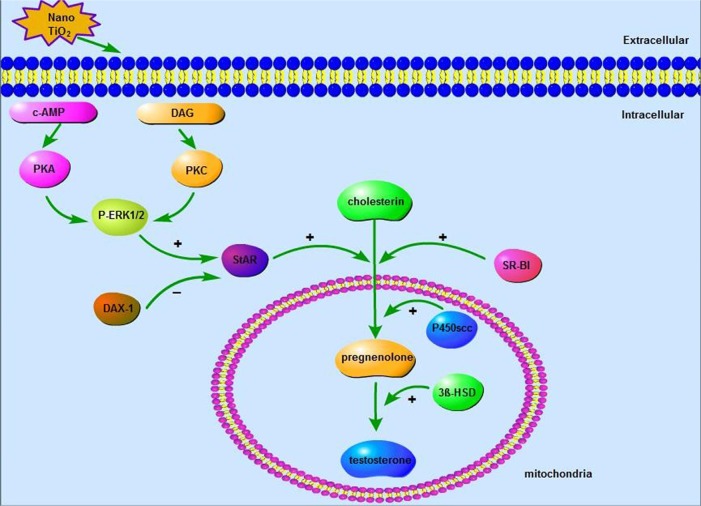

Treatment with a PKA inhibitor has been shown to suppress StAR and SR-BI mRNA expression and ultimately progesterone production, while significant increases in StAR and SR-BI are associated with activation of PKA, indicating that steroid-hormone production is dependent on the PKA-signaling pathway.50 IGF1-mediated StAR expression and steroid synthesis depend additionally on the PKC pathway,49 and expression of StAR is modulated by ERK1/2 accompanied by the PKA and PKC pathways.29,52,53 Furthermore, both pathways are able to rapidly phosphorylate ERK1/2, influencing steroidogenesis to different extents.50 ERK1/2 is suggested to promote transcription of the STAR gene and is potentially involved in steroid synthesis,54 while DAX1 negatively regulates StAR expression and steroid synthesis and is also modulated by PKA and PKC signaling in LCs.29,34 Our data indicated that reduction in StAR and SR-B1 and concomitant increase in DAX1 expression were associated with decreases in PKA, PKC, and pERK1/2 expression. Moreover pERK1/2 reduction may be linked to suppression of PKA and PKC in LCs, leading to decreased testosterone production that contributes to nano-TiO2- induced toxicity. The proposed mechanism underlying nano-TiO2-mediated suppression of testosterone production involving the ERK1/2–PKA–PKC signaling pathways is depicted in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Schematic representation of nanoparticulate TiO2-mediated inhibition of testosterone production via the ERK1/2–PKA–PKC signaling pathway. Taken together, data from the current study suggest that nano-TiO2 enters the cytoplasm and nuclei of LCs, causing structural damage and decreased cell activity and testosterone generation or secretion. Furthermore, suppression of testosterone production in LCs by nano-TiO2 may be associated with dysfunction of ERK1/2–PKA–PKC signaling pathways, with downregulation of StAR, P450scc, 3βHSD, SR-BI, PKA, PKC, and pERK/1/2 and upregulation of DAX1. The complex dynamic pathway of nano-TiO2-mediated inhibition of testosterone synthesis or secretion in LCs requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31871013, 81473007, 31671033, 81273036), National Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant BK20161306), and Top-Notch Academic Programs Project of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PPZY2015A018).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chen Z, Wang Y, Zhuo L, et al. Interaction of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with glucose on young rats after oral administration. Nanomedicine. 2015;11(7):1633–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Z, Wang Y, Zhuo L, et al. Effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the cardiovascular system after oral administration. Toxicol Lett. 2015;239(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaté L, Disdier C, Cosnier F, et al. Biopersistence and translocation to extrapulmonary organs of titanium dioxide nanoparticles after subacute inhalation exposure to aerosol in adult and elderly rats. Toxicol Lett. 2016;265:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linkov I, Satterstrom FK, Corey LM. Nanotoxicology and nanomedicine: making hard decisions. Nanomedicine. 2008;4(2):167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weir A, Westerhoff P, Fabricius L, Hristovski K, von Goetz N, Goetz NV. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles in food and personal care products. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(4):2242–2250. doi: 10.1021/es204168d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu X, Hong F, Zhang YQ. Bio-effect of nanoparticles in the cardiovascular system. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2016;104(11):2881–2897. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei X, Skomski R, Balamurugan B, Sun ZG, Ducharme S, Sellmyer DJ. Magnetism of TiO and TiO2 nanoclusters. J Appl Phys. 2009;105(7):854. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pujalté I, Dieme D, Haddad S, Serventi AM, Bouchard M. Toxicokinetics of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles after inhalation in rats. Toxicol Lett. 2017;265:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreyling WG, Holzwarth U, Schleh C, et al. Quantitative biokinetics of titanium dioxide nanoparticles after oral application in rats: Part 2. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11(4):443–453. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1306893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreyling WG, Holzwarth U, Haberl N, et al. Quantitative biokinetics of titanium dioxide nanoparticles after intratracheal instillation in rats: Part 3. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11(4):454–464. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1306894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong F, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Sheng L, Wang L. Maternal exposure to nanosized titanium dioxide suppresses embryonic development in mice. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:6197–6204. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S143598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong F, Wang L. Nanosized titanium dioxide-induced premature ovarian failure is associated with abnormalities in serum parameters in female mice. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:2543–2549. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S151215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Ma L, Zhao J, et al. Biochemical toxicity of nano-anatase TiO2 particles in mice. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;129(1–3):170–180. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong F, Yu X, Wu N, Zhang YQ. Progress of in vivo studies on the systemic toxicities induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Toxicol Res. 2017;6(2):115–133. doi: 10.1039/c6tx00338a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong F, Wang Y, Zhou Y, et al. Exposure to TiO2 nanoparticles induces immunological dysfunction in mouse testitis. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(1):346–355. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tremblay JJ. Molecular regulation of steroidogenesis in endocrine Leydig cells. Steroids. 2015;103:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong F, Si W, Zhao X, et al. TiO2 Nanoparticle Exposure Decreases Spermatogenesis via Biochemical Dysfunctions in the Testis of Male Mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(31):7084–7092. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boekelheide K, Schoenfeld HA. Spermatogenesis by Sisyphus: proliferating stem germ cells fail to repopulate the testis after ‘irreversible’ injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;500:421–428. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0667-6_64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haider SG. Cell biology of Leydig cells in the testis. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;233:181–241. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)33005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Midzak AS, Chen H, Papadopoulos V, Zirkin BR. Leydig cell aging and the mechanisms of reduced testosterone synthesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;299(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao GD, Yg Z, Zhao XY, et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle-induced testicular damage, spermatogenesis suppression, and gene expression alterations in male mice. J Hazard Mater. 2013;16:258–259. 133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khorsandi L, Orazizadeh M, Moradi-Gharibvand N, Hemadi M, Mansouri E. Beneficial effects of quercetin on titanium dioxide nano-particles induced spermatogenesis defects in mice. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24(6):5595–5606. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-8325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia F, Sun Z, Yan X, Zhou B, Wang J. Effect of pubertal nano-TiO2 exposure on testosterone synthesis and spermatogenesis in mice. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88(3):781–788. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meena R, Kajal K, Paulraj R. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in testicular cells of male wistar rat. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;175(2):825–840. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orazizadeh M, Khorsandi L, Absalan F, Hashemitabar M, Daneshi E. Effect of beta-carotene on titanium oxide nanoparticles-induced testicular toxicity in mice. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31(5):561–568. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0184-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alaee S, Ilani M. Effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on male and female reproductive systems. J Advanced Medical Sci Applied Technol. 2017;3(1):3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payne AH, Youngblood GL, Sha L, Burgos-Trinidad M, Hammond SH. Hormonal regulation of steroidogenic enzyme gene expression in Leydig cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;43(8):895–906. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90317-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manna PR, Cohentannoudji J, Counis R, et al. Mechanisms of action of hormone-sensitive lipase in mouse Leydig cells: its role in the regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(12):8505–8518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manna PR, Jo Y, Stocco DM. Regulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2: role of protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling. J Endocrinol. 2007;193(1):53–63. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pao HY, Pan BS, Leu SF, Huang BM. Cordycepin stimulated steroidogenesis in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells through the protein kinase C Pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(19):4905–4913. doi: 10.1021/jf205091b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azhar S, Reaven E. Scavenger receptor class BI and selective cholesteryl ester uptake: partners in the regulation of steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;195(1–2):1–26. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manna PR, Stetson CL, Slominski AT, Pruitt K. Role of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in health and disease. Endocrine. 2016;51(1):7–21. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0715-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendoza-Villarroel RE, Robert NM, Martin LJ, Brousseau C, Tremblay JJ. The nuclear receptor NR2F2 activates star expression and steroidogenesis in mouse MA-10 and MLTC-1 Leydig cells. Biol Reprod. 2014;91(1):26. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.115790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalli E, Melner MH, Stocco DM, Sassone-Corsi P. DAX-1 blocks steroid production at multiple levels. Endocrinology. 1998;139(10):4237–4243. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manna PR, Wang XJ, Stocco DM. Involvement of multiple transcription factors in the regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression. Steroids. 2003;68(14):1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zazopoulos E, Lalli E, Stocco DM, Sassone-Corsi P. DNA binding and transcriptional repression by DAX-1 blocks steroidogenesis. Nature. 1997;390(6657):311–315. doi: 10.1038/36899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang P, Lu C, Hua N, du Y. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles co-doped with Fe3+ and Eu3+ ions for photocatalysis. Mater Lett. 2002;57(4):794–801. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong FS, Zhao XY, Cheng M, et al. TiO2 nanoparticles induced apoptosis of primary cultured Sertoli cells of mice. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2016;104(1):122–133. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raucci F, D’Aniello A, di Fiore MM. Stimulation of androgen production by D-aspartate through the enhancement of StAR, P450scc and 3β-HSD mRNA levels in vivo rat testis and in culture of immature rat Leydig cells. Steroids. 2014;84:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen J, Zhou H, Santulli AC, Wong SS. Evaluating cytotoxicity and cellular uptake from the presence of variously processed TiO2 nano-structured morphologies. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23(5):871–879. doi: 10.1021/tx900418b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xb L, Sq X, Zhang ZR, Hermann JS. Apoptosis induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in cultured murine microglia N9 cells. Chin Sci Bull. 2009;54(20):3830–3836. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu N, Hong F, Zhou Y, Wang Y. Exacerbation of innate immune response in mouse primary cultured sertoli cells caused by nanoparticulate TiO2 involves the TAM/TLR3 signal pathway. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2016;105(1):198–208. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lq Y, Hong FS, Ze X, Lj L, Zhou YM, Yg Z. Toxic effects of TiO2 nanoparticles in primary cultured rat sertoli cells are mediated via a dysregulated Ca2+/PKC/p38 MAPK/NF-κB cascade. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2017;105(5):1374–1382. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, Tang X, Li Y, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid inhibits the apoptotic responses in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;588(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Payne AH, Youngblood GL. Regulation of expression of steroidogenic enzymes in Leydig cells. Biol Reprod. 1995;52(2):217–225. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharpe RM, Maddocks S, Kerr JB. Cell-cell interactions in the control of spermatogenesis as studied using Leydig cell destruction and testosterone replacement. Am J Anat. 1990;188(1):3–20. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001880103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamindrani Mendis-Handagama SML, Siril Ariyaratne HB. LCs, thyroid hormones and steroidogenesis. Ind J Exp biol. 2005;43(11):939–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong F, Zhao X, Si W, Wh S, et al. Decreased spermatogenesis led to alterations of testis-specific gene expression in male mice following nano-TiO2 exposure. J Hazard Mater. 2015;300:718–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stocco DM, Wang X, Jo Y, Manna PR. Multiple signaling pathways regulating steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: more complicated than we thought. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(11):2647–2659. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao RM, Jo Y, Leers-Sucheta S, et al. Differential regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis in R2C and MA-10 Leydig tumor cells: role of SR-B1-mediated selective cholesteryl ester transport. Biol Reprod. 2003;68(1):114–121. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.007518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manna PR, Chandrala SP, Jo Y, Stocco DM. cAMP-independent signaling regulates steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig cells in the absence of StAR phosphorylation. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;37(1):81–95. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perrett RM, Mcardle CA. Molecular mechanisms of gonadotropin-releasing hormone signaling: integrating cyclic nucleotides into the network. Front Endocrinol. 2013;4:180. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinelle N, Holst M, Söder O, Svechnikov K. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases are involved in the acute activation of steroidogenesis in immature rat Leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology. 2004;145(10):4629–4634. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poderoso C, Maloberti P, Duarte A, et al. Hormonal activation of a kinase cascade localized at the mitochondria is required for StAR protein activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;300(1–2):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]