Abstract

Objective

To compare the risk of serious infections associated with use of systemic steroids, non-biologic agents, or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) inhibitors in pregnancy.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting

Public (Medicaid, 2001-10) or private (Optum Clinformatics, 2004-15) health insurance programs in the US.

Participants

4961 pregnant women treated with immunosuppressive drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, or inflammatory bowel disease.

Exposure for observational studies

Exposure was classified into steroid, non-biologic, or TNF inhibitors on first filled prescription during pregnancy. Because TNF inhibitors are not used to treat systemic lupus erythematosus, patients with this condition were excluded from comparisons involving TNF inhibitors.

Main outcome measure

The main outcome was occurrence of serious infections during pregnancy, defined by hospital admission for bacterial or opportunistic infections. Hazard ratios were derived using Cox proportional hazard regression models after adjustment for confounding with propensity score fine stratification. A logistic regression model was used to conduct a dose-response analysis among women filling at least one steroid prescription.

Results

71 out of 4961 pregnant women (0.2%) treated with immunosuppressive agents experienced serious infections. The crude incidence rates of serious infections per 100 person years among 2598 steroid users, 1587 non-biologic users, and 776 TNF inhibitors users included in this study were 3.4 (95% confidence interval 2.5 to 4.7), 2.3 (1.5 to 3.5), and 1.5 (0.7 to 3.0), respectively. No statistically significant differences in the risk of serious infections during pregnancy were observed among users of the three immunosuppressive drug classes: non-biologics v steroids, hazard ratio 0.81 (95% confidence interval 0.48 to 1.37), TNF inhibitors v steroids 0.91 (0.36 to 2.26), and TNF inhibitors v non-biologics 1.36 (0.47 to 3.93). In the dose-response analysis, higher steroid dose was associated with an increased risk of serious infections during pregnancy (coefficient for each unit increase in average prednisone equivalent mg daily dose=0.019, P=0.02).

Conclusions

Risk of serious infections is similar among pregnant women with systemic inflammatory conditions using steroids, non-biologics, and TNF inhibitors. However, high dose steroid use is an independent risk factor of serious infections in pregnancy.

Introduction

Autoimmune inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease affect approximately 3-4 million Americans.1 2 These conditions are known to have a female predominance and affect many women during their childbearing years. Contemporary research studies indicate that disease flares are relatively common during pregnancy among women with these conditions.3 4 5 High disease activity during pregnancy may be associated with adverse neonatal outcomes, including higher risk of preterm births, intrauterine growth restriction, and spontaneous abortions.6 7 Therefore, controlling disease activity with immunosuppressive agents is often necessary during pregnancy to prevent adverse outcomes.

Increased risk of infections is one of the most important concerns associated with immunosuppressive agents as they substantially interfere with the functioning of patients’ immune systems.8 9 While the risk of serious infections attributable to use of these agents is well characterized in the overall patient populations with autoimmune inflammatory conditions,10 11 12 information on this risk is lacking in pregnant women as they are usually excluded from clinical trials for ethical reasons and are underrepresented in observational studies.13 Pregnancy, being a state of altered immunologic responses, is a particularly vulnerable period and women taking immunosuppressive drugs may be more susceptible to acquire new and more severe infections.14 Understanding the comparative risk of infections in women exposed to various immunosuppressive classes during pregnancy is critically important to guide treatment selection in pregnant women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions. Using data from two large US health insurance databases, Medicaid and Optum Clinformatics, we compared the risk of serious infections in women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions receiving steroids, non-biologic immunosuppressive agents, or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) inhibitors during pregnancy.

Methods

Data sources and study population

For this study we used Medicaid Analytical eXtract files for enrollees in 46 US states and Washington, DC for 2000 to 2010 (excluding Arizona, Connecticut, Michigan, and Montana because of incomplete data) and Optum Clinformatics files for enrollees in United Healthcare from all 50 states and Washington, DC for 2004 to 2015. Comprehensive data on demographics, diagnoses, and procedures performed during outpatient visits or inpatient stays, and outpatient filled prescription records are available in these files and can be tracked longitudinally. Since all prescription drugs are recorded in the pharmacy dispensing databases on insurance payment, missing information on exposure is expected to be low. For outcomes and other medical conditions used as covariates, these administrative databases capture diagnosis data coded electronically during routine care medical visits. Since pregnancy is a condition that requires frequent contact with the healthcare system, missingness is expected to be low.

The study population consisted of women aged 12 to 55 years with completed pregnancies resulting in liveborn infants. We linked mothers with their infants in both data sources deterministically using family identifiers and delivery dates corresponding to birth dates.15 16 We then identified the date of the last menstrual period based on the delivery date after applying a validated algorithm to term and pre-term deliveries separately.17 To prevent incomplete capture of information about the exposure, outcomes, and other study variables we excluded women who did not have continuous eligibility in their health insurance plan between three months before the date of the last menstrual period and one month after the delivery date. Finally, we restricted the study population to women with a recorded diagnosis of the systemic inflammatory conditions of interest (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, or inflammatory bowel disease), who filled at least one outpatient prescription for an immunosuppressive agent during pregnancy. See supplementary eTable1 for a list of ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, ninth revision) diagnosis codes and immunosuppressive agents considered for inclusion.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for recruitment, design, or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Drug exposure and follow-up

The date when the women filled an immunosuppressive prescription for the first time during pregnancy was defined as the index date. We categorized the women into one of three mutually exclusive groups hierarchically based on the index prescription: steroids, non-biologic agents, and TNF inhibitors. Because TNF inhibitors are not indicated for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus we excluded patients with the disease and no concomitant rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease from the comparisons involving TNF inhibitors. After the index prescription, we allowed for use of steroids in the non-biologics group and use of steroids or non-biologics in the TNF inhibitors group to reflect routine clinical practice. To maintain the prespecified hierarchical structure throughout the follow-up period, however, we did not allow for use of non-biologics or any biologics in the steroids group and use of any biologics in the non-biologics group. Consequently, we censored the follow-up on the following switches: steroids to any non-biologic agent or TNF inhibitor and non-biologic agents to a TNF inhibitor. Owing to a small number of patients using a non-TNF inhibitor biologic agent (abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, anakinra, natalizumab, alefacept, and ustekinumab), we were not able to study their effects on risk of infection. We thus stopped the follow-up time when patients from any of the three exposure groups switched to any of the non-TNF inhibitor agents. eFigure 1 contains a schematic representation of the study design. In the primary approach, we followed patients for the outcome of serious infection until the end of pregnancy if they did not switch treatments as described. In a sensitivity analysis, we only conducted comparisons across monotherapy users of steroids, non-biologics, and TNF inhibitors. In another sensitivity analysis, patients were censored when they discontinued their index treatment. Discontinuation was defined as no new filled prescription for the index treatment for one month after accounting for the day supply of the most recent prescription.

Study outcome

The outcome of interest was occurrence of serious infections during pregnancy after the index date. The outcome was defined as a composite of bacterial infection (meningitis, encephalitis, cellulitis, endocarditis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and bacteremia) or opportunistic infections (tuberculosis, systemic candidiasis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis) and identified using discharge diagnosis codes from hospital admission records. To dentify these infections we used a previously validated algorithm, which is reported to have a high positive predictive value (80%) in administrative claims.18

Covariates

We measured several sets of factors for risk adjustment: patient demographic variables—maternal age, geographic region, and insurance program (Public (Medicaid) or private (Optum Clinformatics)); diagnosis of the specific autoimmune inflammatory conditions—systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, or inflammatory bowel disease; other medical conditions and medication use during the baseline period of three months before the last menstrual period and the index date as measures of patients’ comorbidity burden; and healthcare utilization factors recorded during three months before the index date as measures of general patient health and contact with the healthcare system. Other medical conditions included anemia, chronic respiratory illness, cancer, pre-existing diabetes, renal disease, drug misuse or dependence, and recorded obesity or smoking. Drugs included for risk adjustment were opioids, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antihypertensive agents, insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, and antidepressants. The healthcare utilization factors considered were number of distinct prescription drugs used, number of hospital admissions, and number of outpatient visits. In addition, we also identified diagnosis of serious bacterial or opportunistic infections between three months before the last menstrual period and the index date, as previous infection is one of the most important risk factors for future infections.19 20 Use of immunosuppressive drugs before pregnancy was not included as a covariate for risk adjustment because it was strongly associated with the index exposure but had no association with the outcome. Adjusting for such variables is known to result in reduced precision and potential amplification of bias.21 22

Statistical analyses

Primary analysis

For all comparisons in the combined cohort of women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions we provide unadjusted incidence rates, incident rate differences, and incident rate ratios along with 95% confidence intervals. To account for confounding factors, we used propensity score based approaches for risk adjustment. Propensity scores were defined as the predicted probability of receiving the exposure of interest (exposure to non-biologics in the non-biologics versus steroids comparison and exposure to TNF inhibitors in the comparisons involving TNF inhibitors) conditional on patients’ covariate distributions and were derived using logistic regression models containing factors described in the section on covariates, as well as calendar year of last menstrual period, and month of pregnancy in which the follow-up started, as independent variables. Next, we trimmed the non-overlapping portions of the propensity score distribution to exclude non-comparable patients before creating 50 strata based on the distribution of the exposed patients and weighted reference patients proportional to the distribution of the exposed in the stratum into which they fell.23 Finally, we used weighted Cox proportional hazard regression models to derive the adjusted hazard ratios between immunosuppressive treatment and the risk of serious infections. We also plotted propensity score weighted cumulative incidence of serious infections for all three comparisons.24 We further presented crude estimates for the risk of serious infections by the month of pregnancy in each of the three treatment groups.

Secondary analyses

To evaluate the possibility of effect measure modification by diagnoses of underlying autoimmune disease, we conducted an alternate analysis using stratification by indications. Accordingly, we conducted comparisons among three groups of patients defined hierarchically: inflammatory bowel disease (steroids, non-biologics, and TNF inhibitors), systemic lupus erythematosus (steroids and non-biologics), and rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis (steroids, non-biologics, and TNF inhibitors). In each stratum, we used the same propensity score based approach for risk adjustment to derive adjusted associations between use of immunosuppressive treatment and serious infections. To provide a summary hazard ratio for each comparison of interest, we pooled the adjusted estimates for non-biologic versus steroids, TNF inhibitors versus steroids, and TNF inhibitors versus non-biologics across indications using an inverse variance random effects meta-analytic method.25

As opposed to non-biologics or TNF inhibitors, which are used at a standard dose or weight based doses, steroids are used in wide dose ranges. Therefore to evaluate steroid dose as an independent risk factor of infections we conducted a dose-response analysis among women in our cohort who filled at least one steroid prescription in pregnancy. In this analysis we used a logistic regression model to evaluate the association between average daily steroid dose during pregnancy and the risk of serious infections, with adjustment for the underlying systemic inflammatory conditions (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease), additional immunosuppressive drugs use during pregnancy (non-biologics or TNF inhibitors), and the data source (Medicaid or Optum Clinformatics). The average daily dose was calculated as the total cumulative dose in prednisone equivalent milligrams divided by the total number of days of follow-up.

Subgroup analyses

To evaluate the differential risk of infection in important subpopulations, we conducted two subgroup analyses. In the first analysis, we included a subgroup of patients at a higher risk of serious infections. This subgroup was defined by the presence of at least one additional risk factor, including previous serious infection, diabetes mellitus, white blood cell disorders, cancer, chronic lung disease, ischemic heart disease, renal disease, drug misuse, tobacco use, and obesity.19 In the second subgroup analysis, we compared the risk of serious infections between users of non-biologic monotherapy and those of non-biologic and steroid combination therapy to evaluate the additional risk with steroid use among users of non-biologic agents. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient population

This study included a total of 4961 (0.2%) pregnant women drawn from a source population of over two million pregnancies identified from Medicaid and OptumClinformatics data, who had been treated for systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease (see supplementary eFigure 2). The mean age of the included women was 29 (SD 6) years. Most of the women included in our cohort had a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (n=1826 (36.8%)), followed by rheumatoid arthritis (n=1797 (36.2%)), inflammatory bowel disease (n=1123 (22.6%)), ankylosing spondylitis (n=583 (11.7%)), and psoriatic arthritis (n=143 (2.9%)). The crude incidence rates of serious infections per 100 person years among 2598 steroid users, 1587 non-biologic users, and 776 TNF inhibitor users were 3.4 (95% confidence interval 2.5 to 4.7), 2.3 (1.5 to 3.5), and 1.5 (0.7 to 3.0), respectively (table 1). Distribution of most of the patient characteristics was noticeably different across the treatment groups in all our comparisons (see supplementary eTable 2). Weighting by the propensity score substantially reduced imbalances in all the covariates across all comparisons (table 2).

Table 1.

Crude absolute and relative risk estimates for serious infections in pregnant women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions treated with immunosuppressive agents, Medicaid data 2000-10 and Optum Clinformatics data 2004-15

| Population and drug exposure | No of exposed pregnancies | Person years | Serious infection events* | Incidence rate/100 person years (95% CI) | Incidence rate difference/100 person years (95% CI) | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions†: | ||||||

| Steroid | 2598 | 1162 | 40 | 3.4 (2.5 to 4.7) | Ref | Ref |

| Non-biologics | 1587 | 991 | 23 | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.5) | −1.1 (−2.5 to 0.3) | 0.68 (0.41 to 1.14) |

| Patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions† other than SLE: | ||||||

| Steroid | 1879 | 856 | 29 | 3.4 (2.3 to 4.9) | Ref | Ref |

| Non-biologics | 816 | 509 | 11 | 2.2 (1.1 to 3.9) | −1.2 (−3.0 to 0.6) | 0.65 (0.32 to 1.3) |

| TNF inhibitors | 776 | 522 | <11‡ | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.0) | −1.9 (−3.5 to −0.3) | 0.44 (0.20 to 0.96) |

TNF=tumor necrosis factor α; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus.

Serious infections: a composite outcome consisting of patients admitted to hospital for bacterial (meningitis, encephalitis, cellulitis, endocarditis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis, and bacteremia) or opportunistic infections (tuberculosis, systemic candidiasis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis).

Conditions included ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and SLE. TNF inhibitors are not indicated for the treatment of SLE and therefore patients with only SLE were excluded from comparisons concerning TNF inhibitors.

Actual numbers are suppressed for counts <11 as required by data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Table 2.

Covariate distribution among patients included in each comparison after propensity score weighting, Medicaid data 2000-10 and Optum Clinformatics data 2004-15. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Covariates | Patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions* | Patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions* other than SLE | Patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions* other than SLE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-biologics (n=1578) | Steroids (n=2527) | Standardized difference† | TNF inhibitors (n=759) | Steroids (n=1647) | Standardized difference† | TNF inhibitors (n=752) | Non-biologics (n=804) | Standardized difference† | |||

| Demographics | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 29 (6.1) | 29 (6.1) | −2.4 | 30 (5.4) | 31 (5.6) | −3.3 | 30 (5.5) | 30 (5.5) | 1.7 | ||

| Region: | |||||||||||

| Midwest | 424 (26.9) | 683 (27) | −0.4 | 225 (29.6) | 493 (29.9) | −0.6 | 229 (30.5) | 262 (32.6) | −4.6 | ||

| North east | 273 (17.3) | 434 (17.2) | 0.4 | 102 (13.4) | 220 (13.4) | 0.2 | 102 (13.6) | 91 (11.3) | 6.8 | ||

| South | 578 (36.6) | 912 (36.1) | 1.1 | 278 (36.6) | 590 (35.8) | 1.7 | 267 (35.5) | 269 (33.5) | 4.2 | ||

| West | 303 (19.2) | 498 (19.7) | −1.3 | 154 (20.3) | 344 (20.9) | −1.4 | 154 (20.5) | 181 (22.6) | −5.1 | ||

| Insurance type: | |||||||||||

| Medicaid | 743 (47.1) | 1202 (47.6) | −1 | 194 (25.6) | 420 (25.5) | 0.1 | 193 (25.7) | 196 (24.4) | 3 | ||

| Optum Clinformatics | 835 (52.9) | 1325 (52.4) | 1 | 565 (74.4) | 1227 (74.5) | −0.1 | 559 (74.3) | 608 (75.6) | −3 | ||

| Autoimmune inflammatory condition diagnoses | |||||||||||

| Ankylosing spondilitis | 44 (2.8) | 73 (2.9) | −0.5 | 58 (7.6) | 131 (7.9) | −1.1 | 57 (7.6) | 67 (8.3) | −2.6 | ||

| Psoriatic arthritis | 17 (1.1) | 29 (1.2) | −0.7 | 77 (10.1) | 161 (9.8) | 1.2 | 58 (7.7) | 52 (6.5) | 4.9 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 495 (31.4) | 829 (32.8) | −3 | 365 (48.1) | 851 (51.7) | −7.2 | 363 (48.3) | 438 (54.5) | −12.5 | ||

| SLE | 925 (58.6) | 1471 (58.2) | 0.8 | 12 (1.6) | 32 (1.9) | −2.7 | 13 (1.7) | 18 (2.2) | −3.3 | ||

| Irritable bowel disease | 295 (18.7) | 480 (19) | −0.8 | 322 (42.4) | 675 (41) | 2.9 | 333 (44.3) | 331 (41.1) | 6.4 | ||

| Other medical conditions and medication use at baseline | |||||||||||

| Anemia | 136 (8.6) | 232 (9.2) | −2 | 45 (5.9) | 80 (4.9) | 4.7 | 45 (6) | 39 (4.8) | 5.2 | ||

| Chronic respiratory conditions | 23 (1.5) | 37 (1.5) | 0 | <11‡ | 24 (1.5) | −5.1 | <11‡ | <11‡ | 1.3 | ||

| Pre-existing diabetes mellitus | 29 (1.8) | 52 (2) | −1.5 | <11‡ | 22 (1.3) | 0.1 | <11‡ | <11‡ | 2.9 | ||

| Drug misuse or dependence | 43 (2.7) | 64 (2.5) | 1.3 | 11 (1.4) | 22 (1.3) | 0.9 | 11 (1.5) | <11‡ | 2.4 | ||

| Renal disease | 77 (4.9) | 147 (5.8) | −4.1 | <11‡ | <11‡ | 2.8 | <11‡ | <11‡ | 2.1 | ||

| Previous infections | 17 (1.1) | 33 (1.3) | −2.1 | <11‡ | <11‡ | −1.4 | <11‡ | <11‡ | −0.8 | ||

| Insulin | 18 (1.1) | 25 (1) | 1.4 | <11‡ | 20 (1.2) | −2.6 | <11‡ | <11‡ | 1.5 | ||

| Oral hypoglycemic drugs | 27 (1.7) | 53 (2.1) | −3 | <11‡ | 17 (1) | 1.3 | <11‡ | 13 (1.6) | −3.3 | ||

| Opioids | 421 (26.7) | 651 (25.8) | 2.1 | 192 (25.3) | 434 (26.4) | −2.4 | 186 (24.7) | 212 (26.4) | −3.8 | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 109 (6.9) | 181 (7.2) | −1 | 67 (8.8) | 153 (9.3) | −1.5 | 63 (8.4) | 70 (8.7) | −1.2 | ||

| Antidepressants | 282 (17.9) | 448 (17.7) | 0.4 | 127 (16.7) | 269 (16.3) | 1.1 | 128 (17) | 153 (19.1) | −5.3 | ||

| Antihypertensive drugs | 183 (11.6) | 293 (11.6) | 0 | 33 (4.3) | 65 (3.9) | 2 | 33 (4.4) | 34 (4.2) | 1.1 | ||

| Healthcare use characteristics | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) No of distinct prescription drugs | 3 (2.9) | 3 (2.7) | 1.4 | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.8) | −5.3 | 2 (2.8) | 3 (2.8) | −8.8 | ||

| Mean (SD) No of hospital admission | 0 (0.3) | 0 (0.3) | −0.8 | 0 (0.2) | 0 (0.2) | 1.9 | 0 (0.2) | 0 (0.2) | 3.9 | ||

| Mean (SD) No of outpatient visits | 6 (6.1) | 6 (6.2) | −1.8 | 6 (5.5) | 6 (5.9) | −0.7 | 6 (5.5) | 6 (5.5) | −5.4 | ||

TNF=tumor necrosis factor α; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus.

Conditions included ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and SLE. TNF inhibitors are not indicated for the treatment of SLE and therefore patients with only SLE were excluded from comparisons concerning TNF inhibitors.

Standardized differences ≥10 indicate substantial imbalance in a particular covariate between the two treatment groups. Variables with standardized differences >10 after propensity score weighting were also added to the Cox proportional hazards regression model for risk adjustment.

Actual numbers are suppressed for counts <11 as required by data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

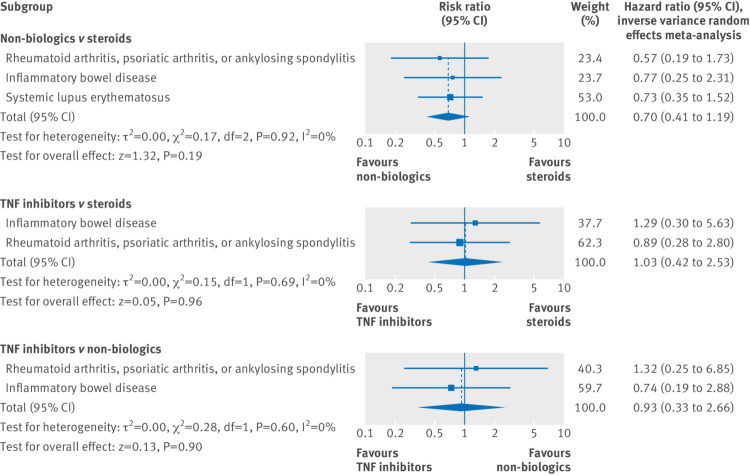

Comparative infection risk

In the adjusted primary analyses, no statistically significant differences in the risk of serious infections during pregnancy were observed among users of the three immunosuppressive drug classes (hazard ratios: non-biologics v steroids 0.81 (95% confidence interval 0.48 to 1.37), TNF inhibitors v steroids 0.91 (0.36 to 2.26), and TNF inhibitors v non-biologics 1.36 (0.47 to 3.93), table 3). Figure 1 shows the propensity score weighted cumulative incidence over follow-up. Estimates from sensitivity analyses using the alternative follow-up approach and exposure definitions were consistent with the primary analysis but had lower precision because of decreased sample sizes (table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted relative risk estimates for serious infections after exposure to immunomodulatory treatments during pregnancy in women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions, Medicaid data 2000-10 and Optum Clinformatics data 2004-15

| Comparison | Adjusted* hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis | Analysis only including patients receiving monotherapy | Analysis truncating follow-up on index treatment discontinuation† | |

| Non-biologics versus steroids in patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions‡ | 0.81 (0.48 to 1.37) | 0.85 (0.44 to 1.61) | 0.71 (0.33 to 1.56) |

| TNF inhibitors versus steroids in patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions‡ other than SLE | 0.91 (0.36 to 2.26) | 0.85 (0.28 to 2.56) | 0.61 (0.12 to 3.16) |

| TNF inhibitors versus non-biologics in patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions‡ other than SLE | 1.36 (0.47 to 3.93) | 1.44 (0.39 to 5.31) | — |

TNF=tumor necrosis factor α; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus.

Adjusted with propensity score weighting in Cox proportional hazard regression models. Variables with standardized differences >10 after propensity score weighting were also added to these models.

Discontinuation defined as no new filled prescription for one month after accounting for day supply of most recent prescription. This approach resulted in insufficient event counts for the TNF inhibitor versus non-biologics comparison to calculate hazard ratios.

Autoimmune inflammatory conditions included ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and SLE. TNF inhibitors are not indicated for the treatment of SLE and therefore patients with only SLE were excluded from comparisons concerning TNF inhibitors.

Fig 1.

Adjusted cumulative incidence plots for serious infections after exposure to immunosuppressive treatments during pregnancy in women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions, Medicaid data 2000-10 and Optum Clinformatics data 2004-15. Comparison of non-biologics versus steroids done in patients with autoimmune inflammatory conditions, including ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) inhibitors are not indicated for the treatment of SLE and therefore patients with only SLE were excluded from comparisons concerning TNF inhibitors

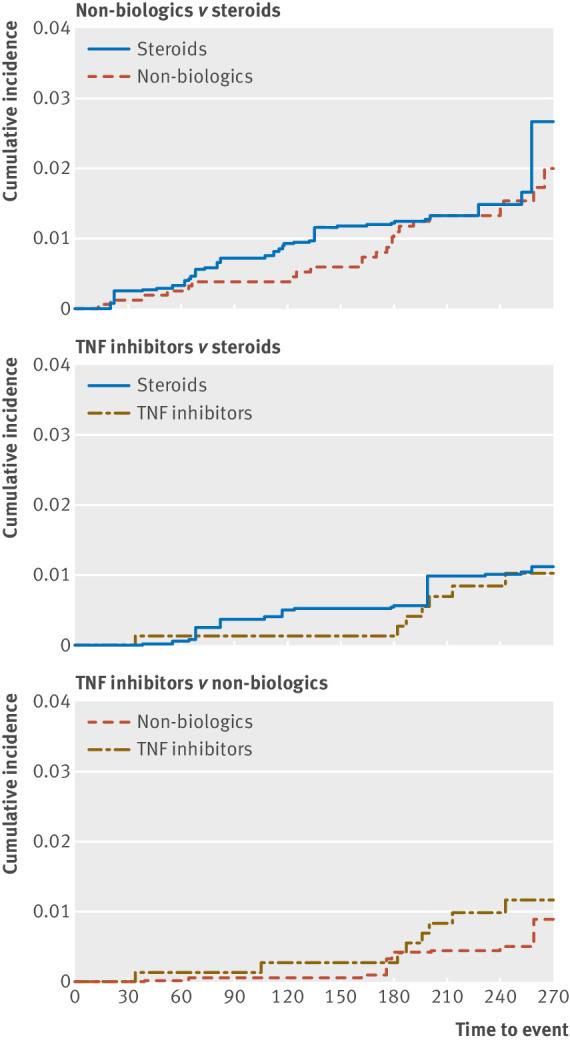

In the secondary analysis using stratification by indications, we observed findings indicating no apparent effect measure modification by underlying diagnoses (fig 2). Consequently, the pooled hazard ratio estimates using inverse variance methods were similar to the findings from the main analysis. See supplementary eTables 3 and 4 for crude incidence rates and covariate balance pertaining to this analysis.

Fig 2.

Adjusted comparative risk estimates for serious infections after exposure to immunosuppressive treatments in pregnancy stratified by disease types, and pooled using inverse variance meta-analysis, Medicaid data 2000-10 and Optum Clinformatics data 2004-15. TNF=tumor necrosis factor α

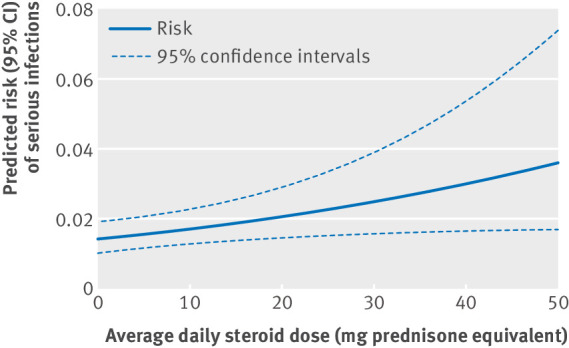

In the dose-response analysis (fig 3), a higher average daily dose of steroids during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of serious infections (coefficient for each unit increase in average prednisone equivalent mg daily dose=0.019, P=0.02). The risk of serious infections was noticeably higher during the later months of pregnancy in all three treatment groups (see supplementary eFigure 3).

Fig 3.

Dose-response analysis for average daily dose of steroids (in prednisone milligram equivalents) during pregnancy in women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions and serious infection risk, Medicaid data 2000-10 and OptumClinformatics data 2004-15. Plotted lines derived from a model that adjusted for indications (ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus), additional immunosuppressive drugs used in pregnancy (non-biologics or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors), and the insurance program. The average daily dose variable was statistically significant (coefficient=0.019 per 1 mg, P=0.02), indicating increasing risk of serious infections with increasing steroid doses

Subgroup analyses

Among patients at a higher risk of serious infections, the hazard ratio for non-biologic versus steroid was 0.66 (95% confidence interval 0.38 to 1.16). Owing to small sample size in the TNF inhibitor group, we were not able to compute effect estimates. In the second subgroup analysis, the hazard ratio for non-biologic and steroid combination therapy versus non-biologic monotherapy was 1.22 (0.54 to 2.78).

Discussion

In this population based cohort study of pregnant women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions, we observed no meaningful difference in the risk of serious infections among users of steroid monotherapy, non-biologics (monotherapy or in combination with steroids), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF) inhibitors (monotherapy or in combination with steroids or non-biologics). However, steroid dose was found to be an independent risk factor of serious infections during pregnancy.

Comparison with other studies

Our current investigation adds critical comparative safety data summarizing the risk of serious infections, which is a known and clinically significant adverse event of immunosuppressive treatments, in a vulnerable patient population of pregnant women.

The crude rates of serious infections reported in the literature among users of specific classes of immunosuppressive drugs in the general patient population are higher than the rates we observed (3 to 8 per 100 person years for TNF inhibitors and 1.4 to 7.8 for non-biologics,10 compared with 1.5 for TNF inhibitors and 2.3 for non-biologics in this study). These differences might be attributable to major variations in the age and comorbidity distribution between our study, which only included younger women with relatively low comorbidity burden during their pregnancies, and the previous studies, which tended to include a majority of older patients with a high burden of comorbidities. Further, we also noted that the risk of serious infections was higher in all three treatment groups during the later months of pregnancy. This observation is in line with the previously suggested hypothesis of lower immune activity leading to greater severity of certain infectious events in late pregnancy14 and suggests that late pregnancy may be a particularly vulnerable period for risk of serious infections associated with immunosuppressive treatments among women with autoimmune diseases.

Clinical implications

Our finding of higher steroid dose during pregnancy being an independent risk factor for infections is in keeping with published data from the general patient populations with autoimmune inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis,26 systemic lupus erythematosus,27 and inflammatory bowel disease.28 This finding is especially relevant because in a previous investigation we reported that steroids are the most commonly used agents during pregnancy in women with rheumatologic autoimmune conditions.16 However, the absolute risk of serious infections was noted to be low at low doses of steroids (0.014 to 0.017 at <10 mg average daily doses). Therefore, low steroid doses with appropriate monitoring may provide a favorable risk-benefit balance for the management of acute flares in pregnant women with autoimmune inflammatory conditions.

We also observed no apparent increase in the risk associated with use of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy compared with non-biologics or steroids. While this finding may be due to insufficient statistical power in our study to detect a small effect size, it does allow us to rule out the possibility of a large increase in risk of serious infection with use of TNF inhibitors. Based on the upper bounds of our 95% confidence intervals from the adjusted comparisons between TNF inhibitors and steroids or non-biologics in our primary analysis, we can exclude the possibility of the risk of serious infections being higher than approximately twofold to fourfold with TNF inhibitors compared with other treatment options (upper confidence limit 2.26 and 3.93 versus steroids and non-biologics, respectively, table 3). However, continuing research efforts are needed to examine the differences in the risk of serious infections with TNF inhibitor use during pregnancy compared with other treatment options.

It must also be noted that selection of an appropriate course of immunosuppressive treatment for managing active autoimmune conditions in pregnancy is a complex task that requires consideration of maternal and fetal safety for multiple outcomes, not only serious infections. One of the most important considerations is the teratogenic potential of drugs being considered. It is noteworthy that certain non-biologic immunosuppressive agents, including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and leflunomide, are known to be teratogenic and therefore should be completely avoided in pregnancy. Other non-biologic agents, including hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and thiopurines (azathioprine and mercaptopurine), are reported to be safe for congenital malformations.29 30 31 32 A potential signal for increased risk of oral clefts with steroid use has been reported.33 Additional concerns, including gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension, have been noted with steroid use during pregnancy.9 34 Evidence for safety of TNF inhibitor use during pregnancy is limited. Although some early reassuring data have been reported regarding their teratogenic potential,35 more research is required to confirm these observations. Based on well studied fetal safety reported in previous investigations and results from our study suggesting low potential for serious infections, hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine for systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis, and thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease can be considered as treatments of choice during pregnancy. Use of low dose steroids seems relatively safe for serious infections in pregnancy; however, women should be closely monitored for serious infections if high dose steroids are used for managing otherwise uncontrolled disease activity.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study has several strengths. It is the first comparative study that systematically evaluates the risk of serious infections after treatment with immunosuppressive agents during pregnancy in a population based nationwide cohort representing women from both higher (Optum Clinformatics) and lower (Medicaid) socioeconomic status. Owing to the availability of longitudinal data on patients’ medical diagnoses and prescription claims, we were able to account for a variety of confounding factors and present risk adjusted estimates for each comparison. Because of a relatively large sample size available for analysis, we were able to conduct additional stratified analysis by underlying inflammatory conditions and eventually pool the results using meta-analytic methods.

Some important limitations to our study also deserve discussion. Firstly, we only included women with a liveborn infant, which may have underrepresented the use of some non-biologic agents that are known to result in abortions, including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and leflunomide. Though this is certainly a limitation, use of these agents in pregnancy should be minimal as they are known teratogens and therefore evaluating the risk of infections with these agents has limited clinical relevance. Secondly, since we did not have measures of disease activity explicitly recorded in our data sources, our study might be subject to residual confounding by these factors. It is possible that patients using steroids may have initiated these agents in pregnancy because of more active disease flares compared with patients using non-biologic agents, and therefore residual confounding by disease activity is possible. It is also noteworthy that the current study focuses on use of steroids in pregnancy for management of maternal chronic autoimmune inflammatory conditions and the associated risk of infection in mothers during pregnancy. Therefore our findings are not generalizable to the population of women at high risk of preterm delivery, where short term use of prenatal corticosteroids is known to be associated with improved neonatal outcomes.36

Conclusion

Findings from this large scale population based cohort study of pregnant women with systemic inflammatory conditions suggest that risk of serious infections is similar among users of steroids, non-biologics, and TNF inhibitors. However, the use of high dose steroids is an independent risk factor of serious infections in pregnancy.

What is already known on this topic

Autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease have a female predominance and affect many women during pregnancy

Increased risk of infections is one of the most important concerns associated with the use of immunosuppressive agents as they substantially interfere with the functioning of patients’ immune systems

Pregnancy, being a state of altered immunologic responses, is a particularly vulnerable period during which patients taking immunosuppressive agents may be more susceptible to acquire new and more severe forms of infections

What this study adds

Use of steroids, non-biologics, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in pregnant women with SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease is associated with similar risk of serious infections

Steroid dose is an independent risk factor of serious infections in pregnancy

Women receiving high dose steroids during pregnancy should be monitored closely for development of serious infections

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: eFigures1-3 and eTables1-4

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare the following interests: KFH is supported by a career development award from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH099141). BTB is supported by a career development award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the NIH (K08HD075831). SH-D is supported by the NIH grant R01 MH100216 and has consulted for AstraZeneca (London, UK) for unrelated projects. YP was supported by a training grant from PhRMA. SCK has received research support from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Lilly on unrelated projects. RJD has received research support from Merck on unrelated projects. BTB, KFH, SH-D report receiving research funding from Pfizer, Lilly, and GSK and BTB form Baxalta for unrelated projects. EP has received research funding from GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim.

Contributors: RJD had full access to all the data in this study and takes full responsibility as a guarantor for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RJD, BTB, KFH, SCK, EP, SH-D, YP, SZD, and JC conceived and designed the study. RJD and HM analysed the data. RJD, BTB, KFH, EP, SH-D, YP, SZD, JC, HM, and SCK interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript.

Funding: The investigators conducted the research independently through funding from internal sources of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, and a data use agreement was in place

Transparency: The manuscript’s guarantor (RJD) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. National Arthritis Data Workgroup Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:15-25. 10.1002/art.23177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1424-9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Man YA, Hazes JM, van der Heide H, et al. Association of higher rheumatoid arthritis disease activity during pregnancy with lower birth weight: results of a national prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:3196-206. 10.1002/art.24914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Østensen M, Fuhrer L, Mathieu R, Seitz M, Villiger PM. A prospective study of pregnant patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis using validated clinical instruments. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1212-7. 10.1136/ard.2003.016881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clowse ME. Lupus activity in pregnancy. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2007;33:237-52, v. 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM, et al. Predictors of Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients With Lupus: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:153-63. 10.7326/M14-2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mecacci F, Pieralli A, Bianchi B, Paidas MJ. The impact of autoimmune disorders and adverse pregnancy outcome. Semin Perinatol 2007;31:223-6. 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:762-84. 10.1002/art.23721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoes JN, Jacobs JW, Boers M, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1560-7. 10.1136/ard.2007.072157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Winthrop KL. Infections and biologic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: our changing understanding of risk and prevention. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2012;38:727-45. 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, Nam JL, et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:529-35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn’s disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:621-30. 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesko SM, Mitchell AA. The use of randomized controlled trials for pharmacoepidemiology studies. In: Strom BL, Kimmel SE, eds. Textbook of Pharmacoepidemiology: Wiley and Sons; 2006:311-9. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kourtis AP, Read JS, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy and infection. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2211-8. 10.1056/NEJMra1213566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Palmsten K, Huybrechts KF, Mogun H, et al. Harnessing the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) to Evaluate Medications in Pregnancy: Design Considerations. PLoS One 2013;8:e67405. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desai RJ, Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, et al. Brief Report: Patterns and Secular Trends in Use of Immunomodulatory Agents During Pregnancy in Women With Rheumatic Conditions. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Margulis AV, Setoguchi S, Mittleman MA, Glynn RJ, Dormuth CR, Hernandez-Diaz S. Algorithms to estimate the beginning of pregnancy in administrative databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:16-24. 10.1002/pds.3284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schneeweiss S, Robicsek A, Scranton R, Zuckerman D, Solomon DH. Veteran’s affairs hospital discharge databases coded serious bacterial infections accurately. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:397-409. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crowson CS, Hoganson DD, Fitz-Gibbon PD, Matteson EL. Development and validation of a risk score for serious infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2847-55. 10.1002/art.34530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Predictors of infection in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2294-300. 10.1002/art.10529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Myers JA, Rassen JA, Gagne JJ, et al. Effects of adjusting for instrumental variables on bias and precision of effect estimates. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:1213-22. 10.1093/aje/kwr364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pearl J. Invited commentary: understanding bias amplification. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:1223-7, discussion 1228-9. 10.1093/aje/kwr352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Desai RJ, Rothman KJ, Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF. A Propensity score based fine stratification approach for confounding adjustment when exposure is infrequent. Epidemiology 2017;28:249-57. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cole SR, Hernán MA. Adjusted survival curves with inverse probability weights. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2004;75:45-9. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manager R. (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

- 26. Dixon WG, Suissa S, Hudson M. The association between systemic glucocorticoid therapy and the risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analyses. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R139. 10.1186/ar3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Olivares N, Ruiz-Arruza I, Martinez-Berriotxoa A, Egurbide M-V, Aguirre C. Predictors of major infections in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R109. 10.1186/ar2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aberra FN, Lewis JD, Hass D, Rombeau JL, Osborne B, Lichtenstein GR. Corticosteroids and immunomodulators: postoperative infectious complication risk in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterology 2003;125:320-7. 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00883-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clowse ME, Magder L, Witter F, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine in lupus pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3640-7. 10.1002/art.22159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaplan YC, Ozsarfati J, Nickel C, Koren G. Reproductive outcomes following hydroxychloroquine use for autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;81:835-48. 10.1111/bcp.12872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Akbari M, Shah S, Velayos FS, Mahadevan U, Cheifetz AS. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of thiopurines on birth outcomes from female and male patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:15-22. 10.1002/ibd.22948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Viktil KK, Engeland A, Furu K. Outcomes after anti-rheumatic drug use before and during pregnancy: a cohort study among 150,000 pregnant women and expectant fathers. Scand J Rheumatol 2012;41:196-201. 10.3109/03009742.2011.626442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bjørn AMB, Ehrenstein V, Nohr EA, Nørgaard M. Use of inhaled and oral corticosteroids in pregnancy and the risk of malformations or miscarriage. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2015;116:308-14. 10.1111/bcpt.12367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kavanaugh A, Cush JJ, Ahmed MS, et al. Proceedings from the American College of Rheumatology Reproductive Health Summit: the management of fertility, pregnancy, and lactation in women with autoimmune and systemic inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:313-25. 10.1002/acr.22516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nielsen OH, Loftus EV, Jr, Jess T. Safety of TNF-α inhibitors during IBD pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Med 2013;11:174. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crowther CA, McKinlay CJ, Middleton P, Harding JE. Repeat doses of prenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth for improving neonatal health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(7):CD003935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: eFigures1-3 and eTables1-4