Abstract

Parents' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions are thought to promote children's social adjustment. Research heretofore has implicitly assumed that such reactions are equally supportive of children's adjustment across ages. Recent findings challenge this assumption, suggesting that during middle childhood, socialization practices previously understood as supportive may in fact impede children's social adjustment. We explored this possibility in a sample of 203 third-grade children and their mothers. Using structural equation modeling, we tested associations between mothers' supportive (i.e., problem- and emotion-focused) reactions to children's negative emotions and children's social skills and problems as reported by mothers and teachers. Mothers' supportive reactions predicted greater social adjustment in children as reported by mothers. Inverse associations, however, were found with teachers' reports of children's social adjustment: mothers' supportive reactions predicted fewer socioemotional skills and more problem behaviors. These contrasting patterns suggest potential unperceived costs associated with mothers' supportiveness of children's negative emotions for third-grade children's social adjustment in school and highlight the importance of considering associations between socialization practices and children's various social contexts. The findings also highlight a need for greater consideration of what supportiveness means across different developmental periods.

Keywords: socialization, emotion, middle childhood, social competence, teachers

Theoretical models and empirical reports of parental emotion socialization emphasize the adaptive utility of responding to children's negative emotions with support (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996; Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg, & Madden-Derdich, 2002). This reasoning is based primarily on research with young children between the ages of 3 and 5. However, for older children between the ages of 7 and 11, factors associated with emotion-related supportiveness (e.g., the belief that parents should guide children's emotional development) appear to relate negatively to various social and emotional competencies (Castro, Halberstadt, Lozada, & Craig, 2015; Dunsmore, Her, Halberstadt, & Perez-Rivera, 2009). The degree to which emotion socialization practices that were supportive in early childhood remain beneficial in older children is unclear. The present study employed a multi-reporter approach to test the effects of mothers' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions on third-grade children's social adjustment as reported by mothers and teachers. Because mothers' primary sources of information about their children are largely derived from the family context, and teachers' primary sources of information are derived from the school context, these differing perspectives help to assess the impact of mothers' supportive reactions in two social contexts: family and school.

Parents' Supportive Emotion Socialization

Emotion socialization broadly refers to the host of behaviors that parents (and other caregivers) engage in to influence children's abilities to understand, experience, and regulate their own and others' emotions (Denham, Bassett, & Wyatt, 2007; Eisenberg et al., 1998). One socialization domain that has received substantial attention is parents' reactions to children's negative emotions. These reactions are thought to include supportive reactions, such as when parents are responsive to children's negative emotions in their efforts to resolve both the antecedent causes and ensuing feelings, and nonsupportive reactions, such as when parents deny, minimize, or punish children's negative emotions (Eisenberg et al., 1996). Through supportive reactions, parents may co-regulate—and potentially down regulate—negative emotional experiences with their children. Supportive parental reactions may also guide children's thoughts and behaviors as they move through and process their negative emotional experience. Consequently, supportive reactions are expected to bolster children's socioemotional skill development by providing opportunities and strategies for children to learn about and manage their own and others' emotions. In contrast, nonsupportive reactions serve to explicitly (e.g., “Stop crying.”) or implicitly (“You're fine.”) invalidate children's negative emotions. Nonsupportive reactions are hypothesized to increase children's own personal distress (Eisenberg, Fabes, Schaller, & Carlo, 1991), resulting in limited opportunities for socioemotional learning and development. Many studies indicate that parents' supportive reactions constitute an adaptive pathway to children's social adjustment (Blair et al., 2014; Dunbar, Perry, Cavanaugh, & Leerkes, 2015; Eisenberg et al., 1996; Fabes et al., 2002). However, whether parents' supportive reactions are uniformly adaptive across development has not been well-tested.

The challenges of defining support developmentally

An underlying assumption of the many studies confirming associations between parents' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions and children's socioemotional development is that these reactions remain beneficial (i.e., supportive) for children of all ages. However, as noted above, two studies assessing a related construct—parents' belief in guiding children's emotion-related experiences and skills—reported negative associations with children's emotional skills in middle childhood (Castro et al., 2015; Dunsmore et al., 2009). Even seemingly benign parenting practices, such as conditional positive regard, can promote maladaptive or negative outcomes by adolescence (Israeli-Halevi, Assor, & Roth, 2015). Thus, definitions of support may require greater consideration of children's changing needs and abilities. Static definitions that assume continuity in the meaning and consequences of supportive practices over time neglect the possibility that parents need to adapt their socialization practices (Stettler & Katz, 2014) in response to changes in children's socioemotional skills and potential variations in the developmental needs of children as they mature (Shipman, Zeman, Nesin, & Fitzgerald, 2003).

Indeed, human development is characterized by changes over time across levels of systems, both internal to the child and external to the child's environment (Cairns, Elder, & Costello, 2001). Consequently, children may require different types of socialization behaviors from parents at different ages. Older children who have developed some modicum of socioemotional skill may require less parental support of their negative emotions than younger children who are still learning about emotions and thus require more active guidance. There is some evidence to support this possibility; parents of older adolescents provide less support in response to children's negative emotions as compared to parents of younger adolescents (Klimes-Dougan & Zeman, 2007). Alternatively, some children may experience developmental difficulties which require different types of socialization practices as in the case with children who are prone to intense negative displays of emotion (Jones, Eisenberg, Fabes, & MacKinnon, 2002). Parents who respond to children's dispositional negative emotionality with encouragement or comfort may inadvertently perpetuate emotional maladjustment. These children may continue to experience and express their emotions in intensely negative ways rather than learning ways to manage or control their emotions, which are adaptive strategies for other settings (e.g., school). Thus, socialization research may need to conceptualize supportive reactions in a more dynamic and developmentally-sensitive way.

Middle childhood and parental support

Middle childhood in particular appears to be an important developmental period in which to observe potential shifts in the definition of supportive emotion socialization behaviors. Between the ages of 7 and 11, children experience important cognitive, emotional, and social gains (Eccles, 1999; Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Halberstadt, Parker, Castro, 2013; Zelazo, Carlson, & Kesek, 2008), which likely contribute to greater interpersonal skill as well as increased autonomy from parents. Simultaneous with these gains, children may require less direct emotional guidance and support from parents (Shipman et al., 2003) than that needed during early childhood. More importantly, children may also benefit from parents working toward coordinated problem-solving and co-regulatory efforts with their children as well as supporting children's greater autonomy and self-direction whenever possible. In addition, other adults (e.g., teachers) and peers likely expect older children to better manage their own emotions and engage with others in behaviorally regulated ways independent of parental guidance and support (Lane, Wehby, & Cooley, 2006; McDowell & Parke, 2005; Mostow, Izard, Fine, & Trentacosta, 2002). Parents might also adjust their socialization efforts during middle childhood in ways that acknowledge children's changing abilities and needs. For example, parents tend to decrease their awareness and acceptance of children's emotions in middle childhood, as compared to the early childhood and pre-adolescent periods (Stettler & Katz, 2014). When parents adjust or alter their socialization efforts to match older children's socialization expectations, social adjustment is more likely to flourish.

If this match does not occur, for example, in situations in which parents continue to guide children's emotional development despite children's abilities to function effectively without that guidance, we may expect non-significant or even inverse associations between older children's social adjustment more broadly defined and parents' supportive socialization practices. Indeed, such findings are increasingly more common when children above the age of 7 are sampled (e.g., Baker, Fenning, & Crnic, 2011; Castro et al., 2015; Dunsmore et al., 2009; Garrett-Peters, Castro, & Halberstadt, 2016).

Our conceptualization has thus far alluded to a causal pathway: Parents could potentially hinder children's continued social development by providing in essence too much guidance and support. However, a consequential pathway is also possible; parents of children who present with social or emotional delays may respond to children's difficulties with increased support. At present, no research has teased apart these pathways. Although causality can only be tested longitudinally, it is important to recognize both potential pathways when conducting cross-sectional research.

Parent and Teacher Perspectives of Children's Social Adjustment

Parents and teachers of third-grade children may occasionally confer with each other (e.g., during school drop-offs and pick-ups or during parent-teacher conferences). However, these observers also have unique first-hand experiences with their children/students, and these experiences, derived largely from different contexts, may then reflect unique perspectives of children's behaviors and skills. Indeed, parents and teachers appear to have very different views about children's social adjustment, including differences in mean level ratings as well as a lack of strong association regarding which children are well-adjusted versus not (e.g., Kolko & Kazdin, 1993; Rudasill et al., 2014). This divergence between parent and teacher perspectives may reflect differences in goals—parents may focus on children's self-esteem whereas teachers may focus on children's academics. Alternatively, parents and teachers may share similar goals for children (e.g., obedience), which require different behaviors with which to comply (e.g., obedience in the family context may involve doing things such as chores, treating siblings with respect, and using one's free time autonomously, whereas in the classroom context obedience may involve not doing things such as jumping out of one's seat, speaking out of turn, or doing what one wants for a few moments), or which require different amounts of time for compliance (e.g., children at home may have more options as to what to do and how, whereas school time may be more regulated). Parent and teacher perspectives may also vary simply because parents have a comparatively smaller number of children to rate, and teachers likely observe a wider spectrum of behaviors. For these reasons, it may be important to examine both parent and teacher assessments of children's social adjustment in relation to parents' supportive reactions, thereby allowing for the assessment of different perspectives and contexts.

Present Study

Our study extends the literature by examining associations between parental supportiveness and child social adjustment across two contexts in middle childhood. We utilized structural equation modeling to test the impact of mothers' support of children's negative emotions on their third-grade children's social adjustment as reported by mothers and teachers. Given developmental shifts in children's social adjustment (Eccles, 1999; Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Halberstadt et al., 2013) and socialization needs (Shipman et al., 2003), as well as evidence for different associations between parental supportiveness of older children's emotions and those children's social adjustment (e.g., Baker et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2015; Dunsmore et al., 2009; Garrett-Peters et al., 2016), we hypothesized that mothers' supportive reactions would negatively predict children's social skills but positively predict children's problem behaviors. We were not sure, however, whether these patterns would be observed for both mothers' and teachers' reports, given that parent and teacher reports of children's social adjustment are so weakly correlated (Kolko & Kazdin, 1993) and may be differentially predicted (Rudasill et al., 2014). Thus, we explored these patterns across mother and teacher reports.

Method

Participants

Participants were 203 third-grade children (117 African American, 82 European American, 4 Biracial; 48.3% female; Mage=8.75 years, SD=0.34 years) and their mothers. Most of these families (N = 127) were participating in the Durham Child Health and Development Study, a larger, longitudinal study of children's biological, cognitive, and socioemotional development conducted in and around Durham, NC. To increase power and generalizability, 76 additional families were recruited from the same community via fliers and postings at schools, doctor's offices, and grocery stores, and through participant referral; this resulted in the total sample of 203 families. Families varied in income (range: $800 to $420,000; Mediansample =$75,000; Mediancommunity=$52,083) and maternal education level (range: 9th grade to post-college education; Median=14.00 years, some college education), with most families residing in the middle class. Children's third-grade teachers also provided assessments of children's social adjustment.

Procedure

Maternal consent and child assent were obtained from each family. Prior to the lab visit, mothers completed a self-report measure of emotion socialization behaviors and questionnaires assessing children's social adjustment. At the lab visit (completed between August and April of the same school year), mothers and children completed questionnaires and tasks not relevant to the present study. Mothers were paid for their time, and children selected a toy as compensation for their time. A set of social adjustment questionnaires—comparable to those mailed to mothers—were then mailed to the third-grade teachers of children for whom mothers provided consent to contact. Teachers' reports were returned approximately 3.5 months after the lab visit (N=165; 81% of total sample).

Measures

Demographic covariates

Given previous evidence that children's social adjustment is affected by family income and education levels (Masten, Burt, & Coatsworth, 2006; Patterson, Kupersmidt, & Vaden, 1990), we included these variables as covariates in our analyses. Total household income was assessed through detailed maternal self-report at the lab visit. For maternal education, mothers indicated the highest grade they completed; most mothers completed at least some college education (N=159), fewer mothers completed high school (N=24) or less (N=12), and eight mothers did not report their education level.

Maternal supportive emotion socialization

Mothers completed a revised version of the Coping with Children's Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES; Fabes, Eisenberg, & Bernzweig, 1990; Stelter & Halberstadt, 2010; see supplemental materials). The original scale includes 12 types of frequently-occurring situations in home life, and measures six types of parents' reactions to children's negative emotions in these situations. The revised version adds four more situations suitable for older children that evoke angry or frustrated feelings, which the original scale lacks. For each situation, mothers rated the degree to which they would use each of six types of reactions using a 7-point scale (Very Unlikely to Very Likely). To assess whether the scale demonstrated different psychometric properties in our sample of older children, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses to determine whether there were any areas of measurement misfit. Based on these analyses one situation from the original CCNES was dropped (similarly to Brown, Craig, & Halberstadt, 2015) because it did not load well on the predicted factors as indicated by a factor loading below .30 and poor model fit. Both the original and the revised versions of the CCNES have demonstrated adequate reliability and construct validity in similar samples of elementary-school-age children (e.g., Jones et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2016; Rogers, Halberstadt, Castro, MacCormack, & Garrett-Peters, 2016).

To test our hypothesis, we used the two types of clearly supportive reactions. Problem-focused reactions assessed mothers' efforts to teach children about the management of emotions or emotional situations (e.g., “help my child think of places he/she hasn't looked yet”, α=.83). Emotion-focused reactions assessed mothers' attempts to comfort or distract the child (e.g., “distract my child by talking about happy things”, α=.85). Because these subscales are conceptually and empirically related (r=.62, p< .001), we averaged them into a single supportive reactions subscale (as done elsewhere, e.g., McElwain, Halberstadt, & Volling, 2007; Wong, McElwain, & Halberstadt, 2009; α= .90).1

Child social adjustment

Mothers and teachers independently completed three questionnaires assessing children's social skills and problems. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for each measure.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Children's Social Adjustment as Reported by Mothers and Teachers.

|

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Report | Teacher Report | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| N | Range | M | SD | N | Range | M | SD | |

| Social Skills Rating System | ||||||||

| Cooperation | 193 | 0.30-2.00 | 1.24 | 0.32 | 164 | 0.30-2.00 | 1.51 | 0.45 |

| Assertion | 193 | 0.60-2.00 | 1.59 | 0.30 | 164 | 0.00-2.00 | 1.36 | 0.46 |

| Self-control | 193 | 0.27-2.00 | 1.35 | 0.35 | 164 | 0.00-2.00 | 1.46 | 0.47 |

| Responsibility1 | 193 | 0.50-2.00 | 1.36 | 0.29 | ||||

| Hyperactivity | 192 | 0.00-2.00 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 165 | 0.00-2.00 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| Internalizing Behaviors | 192 | 0.00-1.67 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 165 | 0.00-2.00 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Externalizing Behaviors | 192 | 0.00-2.00 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 165 | 0.00-2.00 | 0.35 | 0.49 |

| Social Cognitive Skills Rating Scale | ||||||||

| Empathy1 | 193 | 1.67-4.00 | 3.27 | 0.65 | ||||

| Strengths2 | 163 | 0.00-3.00 | 1.92 | 0.77 | ||||

| Cognitive Deficits1 | 194 | 1.00-3.17 | 1.63 | 0.45 | ||||

| Goal Deficits1 | 194 | 1.00-3.33 | 1.40 | 0.50 | ||||

| Problem Solving Difficulties1 | 193 | 1.00-3.75 | 1.94 | 0.56 | ||||

| Deficits2 | 163 | 0.00-2.80 | 0.53 | 0.56 | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Checklist | ||||||||

| Emotion Regulation | 195 | 2.13-4.00 | 3.33 | 0.39 | 165 | 1.50-4.00 | 3.19 | 0.52 |

| Emotional Lability | 195 | 1.00-3.20 | 1.67 | 0.39 | 165 | 1.00-3.40 | 1.58 | 0.51 |

Note

Subscale assessed only in parent version (SSRS-P, SCSRS-P);

Subscale assessed only in teacher version (SCSRS-T)

The Social Skills Rating System parent and teacher versions (SSRS-P, SSRS-T; Gresham & Elliott, 1990) for this age group assess three domains of children's social skill: cooperation (10 items), assertion (10 items), and self-control (10 items). An additional social skill domain—responsibility (10 items)—is measured in the parent version only. The SSRS-P and SSRS-T also include three 6-item subscales to assess children's problem behaviors: hyperactivity, internalizing, and externalizing. Mothers and teachers responded to each item on a 3-point scale (0 = Never, 1 = Sometimes, and 2 = Very Often). Items were averaged across subscales to compute composite scores for social skills (αmother=.89, αteacher=.97) and social problems (αmother=.87, αteacher=.92). Several studies provide evidence of internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity for both versions of the SSRS (Burchinal, Roberts, Zeisel, & Rowley, 2008; Castro, Halberstadt, & Garrett-Peters, 2016; Elliot, Gresham, Freeman, & McCloskey, 1998; Gresham & Elliott, 1990).

The parent version of the Social Cognitive Skills Rating Scale (SCSRS-P; Kupersmidt, Stelter, & Parker, 2014) assesses parents' perceptions of elementary school-age children's social cognitive ability in four domains: empathy (3 items), cognitive deficits (6 items), goal deficits (3 items), and problem solving difficulties (4 items). We considered empathy an indicator of social skill, and the latter three domains as indicators of social problems. The teacher version (SCSRS-T) measures children's social cognitive functioning with peers in the classroom on two domains: social cognitive strengths/skills (6 items) and social cognitive deficits/problems (5 items). Despite the calculation of different subscales, the parent and teacher versions of the SCSRS include eight of the same items and demonstrate considerable conceptual and measurement continuity across versions. Mothers and teachers rated each item as to the frequency of occurrence on 4-point Likert scales (Not at All to Very Often). Reliability in this study ranged from .65 to .87 for maternal reports and .84 to .95 for teacher reports. Recent findings illustrate construct validity for the SCSRS-P and SCSRS-T through associations with teacher reports of children's aggression, hyperactivity, and a variety of social skills and prosocial behaviors (Kupersmidt et al., 2014).

The Emotion Regulation Checklist for parents and teachers of elementary school-age children (ERC-P, ERC-T; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997) consists of two subscales assessing children's emotion regulation ability (8 items) and emotional lability/negativity (15 items). Mothers and teachers indicated how characteristic each item was of the target child on 4-point Likert scales (Rarely/Never to Almost Always). In this study, reliability estimates ranged from .68 to .86 for mothers and .82 to .92 for teachers. The ERC has demonstrated good reliability, construct validity, and discriminant validity (Kim & Cicchetti, 2010; Rogers et al., 2016).

Results

All variables met univariate and multivariate assumptions for statistics based on the general linear model (e.g., normal distributions, homoscedasticity; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Results were first analyzed using bivariate correlations between mothers' supportive reactions and mother- and teacher-reported social adjustment (see Table 2). For mothers' reports of children's social adjustment, findings were consistent with those from early childhood; mothers' supportive reactions were positively correlated with children's socioemotional skills and negatively—albeit, nonsignificantly—correlated with socioemotional problems. However, inverse correlations were found with teachers' reports; mothers' supportive reactions were negatively associated with children's socioemotional skills and positively associated with socioemotional problems.

Table 2. Correlations between Mothers' Supportive Reactions, Children's Social Adjustment, and Covariates.

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Maternal Emotion Socialization | ||

|

|

|||

| Measure | Total Family Income | Maternal Education | Supportive Reactions (CCNES) |

| Mother-Reported Social Skills | |||

| Cooperation (SSRS-P) | .23** | .14† | .18* |

| Assertion (SSRS-P) | .32*** | .18* | .08 |

| Self-control (SSRS-P) | .33*** | .16* | .11 |

| Responsibility (SSRS-P) | .31*** | .26*** | .18* |

| Empathy (SCSRS-P) | .27*** | .22** | .17* |

| Emotion Regulation (ERC-P) | .34*** | .23** | .17* |

| Mother-Reported Social Problems | |||

| Hyperactivity (SSRS-P) | -.19** | -.15* | -.06 |

| Internalizing Behaviors (SSRS-P) | -.04 | -.07 | -.04 |

| Externalizing Behaviors (SSRS-P) | -.13† | -.05 | -.11 |

| Cognitive Deficits (SCSRS-P) | -.04 | -.17* | -.02 |

| Goal Deficits (SCSRS-P) | -.13† | -.04 | -.11 |

| Problem Solving Difficulties (SCSRS-P) | -.26*** | -.29*** | -.15* |

| Emotional Lability (ERC-P) | -.30*** | -.21** | -.09 |

| Teacher-Reported Social Skills | |||

| Cooperation (SSRS-T) | .40*** | .34*** | -.17* |

| Assertion (SSRS-T) | .31*** | .23** | -.14† |

| Self-control (SSRS-T) | .35*** | .35*** | -.22** |

| Social Cognitive Strengths (SCSRS-T) | .35*** | .27** | -.17* |

| Emotion Regulation (ERC-T) | .29*** | .20* | -.13† |

| Teacher-Reported Social Problems | |||

| Hyperactivity (SSRS-T) | -.20* | -.16* | .23** |

| Internalizing (SSRS-T) | -.33*** | -.35*** | .25** |

| Externalizing (SSRS-T) | -.31*** | -.30*** | .13† |

| Social Cognitive Deficits (SCSRS-T) | -.18* | -.17* | .28*** |

| Emotional Lability (ERC-T) | -.32*** | -.31*** | .24** |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01. p < .001.

Intracorrelations among social skills and problems subscales were moderate to high in strength for both mothers (rs for skills: .39 to .66, problems: .24 to .69; ps< .001) and teachers (rs for skills: .57 to .80, problems: .31 to .80; ps< .001). However, intercorrelations between mother and teacher ratings for the same subscales/measures were weak; the lowest associations were found between mothers' and teachers' reports of children's social cognitive difficulties and self-control (rs=.07 & .16, ps=.385 & .043) and the highest associations between mothers' and teachers' reports of children's assertion and internalizing problems (rs=.47 & .35, ps< .001). The low median association (r=.28) replicates previous research (Kolko & Kazdin, 1993; Rudasill et al., 2014). These results supported the modeling of mother- and teacher-reported skills and problems as independent latent variables in subsequent structural analyses. Moreover, as shown in Table 2, correlations with covariates revealed significant associations between total family income and maternal education and several of the indicators of children's social adjustment, providing empirical justification to include these variables as covariates in subsequent analyses.

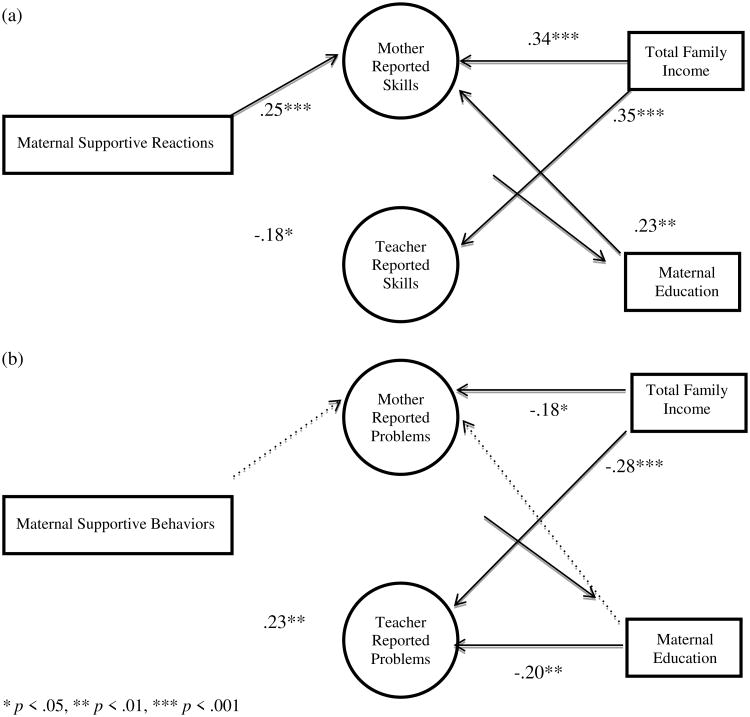

We next employed structural equation modeling using Mplus 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015) to test the effects of mothers' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions on mothers' and teachers' reports of children's social skills and problems (see Figure 1). To ensure sufficient power to detect effects, separate models were tested for social skills and problems by reporter, resulting in four tested models. We controlled for the influence of total family income and maternal education on children's social skills and problems in each model. A covariance parameter was also modeled between total family income and maternal education given that these constructs are highly interrelated. Mothers' supportive reactions, education, and total family income were modeled as observed variables, and children's social skills and problems as reported by mothers and teachers were modeled as latent variables. Specifically, latent variable indicators included cooperation, assertion, self-control, responsibility (SSRS-P), empathy (SCSRS-P), and emotion regulation (ERC-P) for mother-reported skills; hyperactivity, internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors (SSRS-P), cognitive deficits, goal deficits, problem solving difficulties (SCSRS-P), and emotional lability (ERC-P) for mother-reported problems; cooperation, assertion, self-control (SSRS-T), social cognitive strengths (SCSRS-T), and emotion regulation (ERC-T) for teacher-reported skills; and hyperactivity, internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors (SSRS-T), social cognitive deficits (SCSRS-T), and emotional lability (ERC-T) for teacher-reported problems.

Figure 1.

Structural equation models of mothers' supportive reactions predicting mothers' and teachers reports of children's (a) social skills and (b) social problems. Four separate models were tested (skills and problems for mothers and teachers, respectively); standardized estimates are presented here together for simplicity and comparative purposes. Skills and problems were modeled as latent variables. Supportive behaviors, total family income, and maternal education were modeled as manifest variables. Covariance paths and estimates are omitted to aid presentation. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. Solid lines indicate significant paths, and include the standardized regression coefficient.

Missing data occurred an average of 5.35% across models and resulted from failure to return mother and teacher questionnaire packets and demographic survey information. Missing data were addressed by maximum likelihood estimation. Following statistical recommendations by Muthén and Muthén (1998-2015), the variances of the predictors (maternal education, total family income, and supportive reactions) were estimated in the model to allow for the estimation of missing data, and thus, full model estimation. Model fit was assessed using the chi-square statistic (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewin Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the 90% confidence interval around RMSEA (90% CI), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Good model fit to the data is indicated by a nonsignificant χ2, CFI and TLI ≥ .90 and RMSEA and SRMR ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006). Because χ2 is sensitive to sample size, we report the relative chi-square ratio (χ2/df; Wheaton, Muthen, Alwin, & Summers, 1977) where appropriate; ratios between 1 and 5 indicate adequate model fit (Bentler & Chou, 1987). Modification indices were also calculated to identify potential areas of model misfit; values above 10 indicated parameters that, if estimated, may reduce the overall χ2 and improve model fit (Brown & Moore, 2012).

Measurement models were first estimated for the latent variables to ensure proper estimation of social skills and problems latent variables for the final predictive models. The measurement model for teacher-reported problems was adequate (χ2(5)=9.85, p=.08, CFI=.99, TLI=.98, RMSEA=.08, 90% CI=.00-.15, SRMR=.02). The remaining models were improved following modification indices. The structure of mother-reported skills was improved by adding a covariance between empathy and emotion regulation (χ2(8)=10.19, p=.252, CFI=1.00, TLI=.99, RMSEA=.04, 90% CI=.00-.10, SRMR=.02). The structure of mother-reported problems was improved by adding a covariance between problem solving deficits and cognitive deficits, between problem solving deficits and lability, and between externalizing behaviors and social goals deficits (χ2(11)=28.25, p=.003, χ2/df=2.57, CFI=.97, TLI=.94, RMSEA=.09, 90% CI=.05-.13, SRMR=.04). Finally, the structure of teacher-reported skills was improved by adding a covariance between cooperation and assertion and between assertion and emotion regulation (χ2(3)=1.13, p=.770, CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, RMSEA=.00, 90% CI=.00-.09, SRMR=.00). These modifications were included in subsequent structural equation models; standardized factor loadings are presented in Table 3. Importantly, these modifications not only improved model fit empirically, but also made theoretical sense given methodological and conceptual overlap of these variables. Because mothers and teachers rated the same child on similar behaviors, we expected shared methodological variance between subscales of the same measure (e.g., SSRS) as reported by the same person (e.g., teachers). Moreover, given overlap among core emotional, physiological, and situational processes across social domains, we expected shared variance between subscales assessing related skills or behaviors (e.g., empathy and emotion regulation; hyperactivity and emotional lability).

Table 3. Standardized Factor Loadings for Social Skills and Problems Latent Variable Indicators.

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Variable | Manifest Indicator (and Measure) | β | SE | p |

| Mother-Reported Skills | Cooperation (SSRS-P) | 0.75 | 0.04 | .000 |

| Assertion (SSRS-P) | 0.66 | 0.05 | .000 | |

| Self-control (SSRS-P) | 0.83 | 0.03 | .000 | |

| Responsibility (SSRS-P) | 0.66 | 0.05 | .000 | |

| Empathy (SCSRS-P) | 0.65 | 0.05 | .000 | |

| Emotion Regulation (ERC-P) | 0.70 | 0.04 | .000 | |

| Mother-Reported Problems | Hyperactivity (SSRS-P) | 0.81 | 0.03 | .000 |

| Internalizing Behaviors (SSRS-P) | 0.61 | 0.05 | .000 | |

| Externalizing Behaviors (SSRS-P) | 0.80 | 0.03 | .000 | |

| Cognitive Deficits (SCSRS-P) | 0.59 | 0.05 | .000 | |

| Goal Deficits (SCSRS-P) | 0.57 | 0.06 | .000 | |

| Problem Solving Difficulties (SCSRS-P) | 0.48 | 0.06 | .000 | |

| Emotional Lability (ERC-P) | 0.80 | 0.04 | .000 | |

| Teacher-Reported Skills | Cooperation (SSRS-T) | 0.77 | 0.04 | .000 |

| Assertion (SSRS-T) | 0.81 | 0.03 | .000 | |

| Self-control (SSRS-T) | 0.87 | 0.03 | .000 | |

| Social Cognitive Strengths (SCSRS-T) | 0.90 | 0.02 | .000 | |

| Emotion Regulation (ERC-T) | 0.76 | 0.04 | .000 | |

| Teacher-Reported Problems | Hyperactivity (SSRS-T) | 0.82 | 0.03 | .000 |

| Internalizing (SSRS-T) | 0.43 | 0.07 | .000 | |

| Externalizing (SSRS-T) | 0.89 | 0.02 | .000 | |

| Social Cognitive Deficits (SCSRS-T) | 0.79 | 0.03 | .000 | |

| Emotional Lability (ERC-T) | 0.96 | 0.01 | .000 | |

Four predictive models were then tested examining the impact of mothers' supportive reactions on children's social skills and problems as reported by mothers and teachers. Good model fit to the data was observed for all four predictive models: mothers' reports of children's social skills (χ2(23)=23.72, p=.420, CFI=1.00, TLI=1.02, RMSEA=.00, 90% CI=.00-.05, SRMR=.03) and problems (χ2(29)=73.36, p<.001, χ2/df=2.53, CFI=.93, TLI=.90, RMSEA=.09, 90% CI=.06-.11, SRMR=.06); teachers' reports of children's social skills (χ2(15)=12.68, p=.627, CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, RMSEA=0.00, 90% CI=.00-.06, SRMR=.03) and problems (χ2(17)=28.86, p=.036, χ2/df=1.68, CFI=.98, TLI=.97, RMSEA=.06, 90% CI=.02-.09, SRMR=.04). Estimates from these four predictive models are collectively depicted for simplicity and comparative purposes in Figure 1.

Structural equation modeling results mirrored correlational analyses. Controlling for the influence of total family income and maternal education on children's social adjustment, mothers' supportive reactions predicted greater skill (β=.25, p< .001, 95% CI= [.12, .39]) and fewer problems (β= -.12, p= .124, 95% CI= [-.27, .03]) when reported by mothers; however, mothers' supportive behaviors predicted fewer skills (β= -.18, p= .015, 95% CI= [-.33, -.04]) and more problems (β= .23, p= .002, 95% CI= [.08-, 37]) when reported by teachers. Replicating past research (Masten et al., 2006; Patterson et al., 1990), total family income and maternal education were positively related to children's social skills (βs= .17 to .35, ps< .05) and negatively related to children's social problems (βs= -.15 to -.28, ps< .08) across models. In all models, total family income and maternal education were moderately positively associated (βs= .31-.32, ps< .001).

In addition, because two measures (SSRS, SCSRS) included different variants of subscales for mothers and teachers, the four models were replicated with only those subscales that were administered to both reporters. The model fit parameters were essentially the same (i.e., indicating good fit), and the path estimates were all in the same direction and were identical or highly similar in magnitude. Thus, it cannot be said that the reporter differences are due to subscale differences. We retained the models with the larger set of subscales, as they provide greater stability and a more comprehensive assessment of children's social adjustment.

Discussion

In our study of children in middle childhood, maternal-report data replicated previous emotion socialization findings with young children: greater maternal support predicted greater social adjustment. In contrast, teacher-report data showed inverse associations: greater maternal support predicted less social adjustment. These results add to the growing body of work suggesting age-related shifts in the utility of supportive emotion socialization practices (Baker et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2015; Dunsmore et al., 2009; Garrett-Peters et al., 2016; Mirabile, Oertwig, & Halberstadt, 2016; [omitted]). In the next sections, we discuss how our results inform competing explanations of underlying mechanisms and delineate areas for future research on the conceptualization and measurement of supportive emotion socialization in childhood.

Supportive Emotion Socialization: Consequence or Cause of Children's Social Adjustment?

One possible explanation for the negative associations observed between mothers' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions and children's social adjustment as reported by teachers involves an evocative transaction between children and mothers: Mothers may respond to children's socioemotional difficulties with increased support as a means to redirect children towards social and emotional adaptation. In this way, mother's supportive reactions are a consequence of children's socioemotional difficulties.

Given the positive associations between mothers' supportive reactions and their reports of children's social adjustment, however, it is unlikely that mothers were responding to perceived socioemotional difficulties in children; if they were, we would expect greater support to predict lower ratings of social adjustment by mothers. An alternative causal explanation exists, whereby mothers' over-supportiveness may contribute to children's social and emotional maladjustment over time. The very different patterns observed in our study between maternal support and children's social adjustment by reporter suggest a causal mechanism and indicate that mothers with children who are challenged in school (according to teachers) perceive benefits of emotional supportiveness that do not translate to the school context. It may be that continued parental support of children's negative emotions over time constrains children's abilities to independently manage their emotions. That is, if older children become overly reliant on their parents for emotional support, they may not develop the skill sets needed to independently generate appropriate ways of managing their negative emotions (Calkins & Hill, 2007). To the extent that parents fail to perceive or value children's developing emotional autonomy, parents may not alter their socialization practices to match the developmental needs of their children, thereby contributing to children's continued maladjustment. Future longitudinal work with larger samples is needed to more fully explore these underlying mechanisms (for recent example, see [omitted]) and to better determine whether and in which contexts parents' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions are contributing or responding to children's socioemotional deficits over time.

A third possibility is that mothers' supportive reactions are associated with benefits at home, but not at school, due to the different contextual opportunities and demands afforded in these two different contexts. For example, schools are increasingly implementing social and emotional learning (SEL) policies and curricula that focus on building teacher-student relationships, promoting cooperation and conflict reduction in the classroom, and/or establishing a greater sense of school safety (e.g., prevention of bullying), among others (Greenberg et al, 2003; Zins, Weissberg, Wang, & Walberg, 2004). Given that these SEL goals may be school specific, parents' supportive reactions may not facilitate the development of children's SEL competencies most relevant to teachers' perceptions of school adjustment. In addition, teachers have to manage the emotional experiences of a large group of children and may focus on proactive classroom management rather than “after the fact” supportive reactions. In contrast, parents may have different opportunities to scaffold children's emotional development. For example, although it may be challenging to sit through a child's emotional outburst, parents scoring high in supportiveness may view an outburst as an opportunity to teach their child about emotions or a necessary relief-valve following over-stimulation or tiredness that is not desirable, but which simply requires waiting for completion before moving along. The same emotional outburst in a classroom, however, may have more severe immediate consequences (e.g., creating a poor learning environment for the many other children in the class) and thus requires disciplinary responses. As the contexts in which children reside differentiate, it is likely that the quality of supportive socialization practices will vary for different children in different contexts. Our results highlight the need to consider the differential impact of parental supportiveness on the multiple contexts in which children develop

One interesting question emerging from the divergence between mother and teacher reports of children's social adjustment is whether the low coherence reflects differences in reporter perspective rather than context. That is, do teachers and parents observe the same social and emotional behaviors in their respective contexts but differentially evaluate these behaviors or do parents and teachers observe different behaviors thus resulting in different ratings? Parents may, for example, evaluate a child's current behavior with respect to the child's previous behavior and at younger ages. In contrast, teachers may evaluate a child's behavior relative to the many other same-age students in a given classroom or across classrooms. Future work should aim to explain the divergence in ratings, including whether there are developmental transition points at which ratings diverge and why, and to explore how parents' socialization processes may impact the divergence as observed in the present study. To further illuminate interpretations of children's behavior and how perceptions of typicality or what is most of value to parents and teachers, future work might also want to compare parent and teacher assessments of the “typical” and/or “ideal” child.

Conceptual and Methodological Considerations of Supportive Emotion Socialization

Our results highlight a need for researchers to reconsider the conceptualization of supportive reactions to older children's negative emotions. Our findings do not challenge the many studies that find a positive association between parents' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions and young children's adaptive outcomes. Rather, the results indicate that the conceptualization and subsequent measurement of supportive reactions need to be dynamic with age; what is promotive early in development—when children are between the ages of 3 and 5—may not be equally promotive later in development. This conclusion suggests a need for future research to consider why certain behaviors might elicit more or less support for different children at different ages rather than simply relying on static conceptualizations of support.

Supportive behaviors as defined by problem- and emotion-focused reactions to children's negative emotions may be most beneficial for young children and/or children requiring continued parental guidance due to emotional and social difficulties. Reactions that are supportive for young children may impede more sophisticated skill development in the same domain as children grow older and encounter more complex situations. Thus, different socialization practices may become more relevant in shaping older children's social and emotional development, suggesting a need to refine what we consider to be “supportive” at different developmental periods.

Refinement of the definition of support could occur at both the conceptual and measurement levels. At the conceptual level, recent work has demonstrated that for older children, seemingly “maladaptive” socialization practices like the belief that children's emotions are problematic or dangerous predict higher levels of emotional skill in children, whereas traditionally “adaptive” practices like valuing and guiding children's emotions do not (Castro et al., 2015; Garrett-Peters et al., 2016). This may also explain a shift found in the literature on family expressiveness; young children's recognition of others' emotions benefits from expressive families, but a shift as children enter school indicates that older children from less expressive families are more skilled at emotion recognition over time (Halberstadt & Eaton, 2002). Thus, research should aim to identify and examine other domains and socialization practices to determine whether similar age-related shifts exist.

At the measurement level, it may be necessary to revise existing parental emotion socialization measures for conceptual continuity across childhood. In the present study, we used a revised version of a common parental emotion socialization questionnaire (CCNES; Fabes et al., 1990; Stelter & Halberstadt, 2010) to allow for the assessment of more complex and developmentally-oriented emotional situations. The CCNES has been similarly revised in other recent studies (e.g., Brown et al., 2015; Nelson et al., 2013). However, it may not be enough to simply revise situations; rather, the reactions themselves likely require revision. The emotion-focused reactions subscale of the CCNES includes items in which parents distract the child from their emotions or seek to calm the child. However, distraction and soothing may be inappropriate socialization strategies for older children who are developing more mature, adult-like levels of emotion regulation knowledge and skill (Castro et al., 2016; Pons, Harris, & de Rosnay, 2004; Eisenberg & Morris, 2002). Because distraction is a less sophisticated regulatory strategy (Gross & Thompson, 2007), parental use of distraction may constrain older children's opportunities for emotional growth. Parental supportiveness of older children may include instead: acknowledgement of a child's negative feelings without actively trying to resolve the underlying problem; a guided reframing of the problem by asking children to reinterpret the situation in their own words or to see the silver lining; and/or a query to the child about how the child might himself or herself solve the problem, thereby suggesting that the child has the ability to search for a solution while also being simultaneously available for joint brainstorming about various solutions.

Such measurement revisions would also parallel common research practices that assume methodological discontinuity in socialization behaviors. That is, observational assessments often include different situations as well as different coding schemes for children of different ages to reflect developmentally-appropriate forms of behavior. The same degree of developmental differentiation should be reflected in self-report measures of emotion socialization.

Lastly, conceptualizations of supportive emotion socialization behaviors—particularly in older children—may benefit from the assessment of children's perceptions of parents' socialization. Comparisons between child and parent ratings reveal modest correlations at best (Kolko & Kazdin, 1993; Pelegrina, Garcia-Linares, & Casanova, 2003). Moreover, children may perceive parents' supportive socialization behaviors as less supportive relative to parents' perceptions (Gaylord, Kitzmann, & Coleman, 2003), which could negatively impact the development of children's social skills. Studies that include both parent and child assessments of socialization behaviors are likely to reveal important distinctions between the underlying mechanisms driving inverse associations between parents' supportive reactions to children's negative emotions and children's social adjustment.

Strengths and Limitations

Although our study demonstrates several important strengths including a focus on emotion socialization in older children ages 7-to-9 and multiple reporters, we note some limitations. First, because we used a revised version of the CCNES (Fabes et al., 1990), it could be argued that our findings reflect the use of an altered measure. However, the revised scale shared 80% of the same items with the original scale, maintaining both conceptual and at least partial measurement continuity. Moreover, this critique does not explain the differential patterns observed for mother- and teacher-reported social adjustment. Second, our cross-sectional study cannot speak fully to explorations regarding underlying mechanisms or transactions between children and parents. Indeed, because mothers and teachers rated children's social skills and problems at different times (although within the same school year), it is possible that differences in ratings reflect time-related changes in children's behaviors. Given the findings presented in this special issue, a natural extension would be to explore these associations at multiple time points throughout childhood to determine at what point in development a shift in the utility of supportive reactions to children's negative emotions occurs and why. Third, estimates obtained from structural equation modeling are sample and method specific and thus should be replicated in diverse samples using additional methods. Because our study relied entirely on self-report from mothers and teachers, it is unclear whether our findings would extend to behavioral measures of parental emotion socialization and children's social adjustment. Finally, as noted briefly above, further explorations differentiating between the effects of contextual demands (i.e., family vs. school) and effects of reporter (i.e., mother vs. teacher) perspectives are needed to better understand how, why, at what ages, and in which contexts the support of children's negative emotions is adaptive.

In sum, our findings suggest that traditional conceptualizations of supportive parental emotion socialization are too static; definitions of support should be revised to be more dynamic and developmentally-sensitive. Moreover, our findings shed some light on potential differences in the perception of how supportive reactions influence children across family and school contexts. We hope that our study will serve as a spring board for additional developmentally-driven explorations of the conceptualization and measurement of supportive emotion socialization across childhood.

Footnotes

We omitted the “expressive encouragement” subscale of the CCNES—which has been linked to socioemotional problems in some samples (e.g., Nelson et al., 2013)—because it includes items assessing parents' encouragement of visible expressions of distress (crying, trembling) or disappointment in public settings. These items fail to recognize the powerful peer display rules against vulnerable emotions in third grade and might confound parental emotional supportiveness with parental confusion about what might be appropriate emotional displays in public settings.

Contributor Information

Vanessa L. Castro, Department of Psychology, Northeastern University

Amy G. Halberstadt, Department of Psychology, North Carolina State University

Patricia T. Garrett-Peters, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References

- Baker JK, Fenning RM, Crnic KA. Emotion socialization by mothers and fathers: Coherence among behaviors and associations with parent attitudes and children's social competence. Social Development. 2011;20:412–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair BL, Perry NB, O'Brien M, Calkins SD, Keane SP, Shanahan L. The indirect effects of maternal emotion socialization on friendship quality in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:566–576. doi: 10.1037/a0033532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Craig AB, Halberstadt AG. Parent gender differences in emotion socialization behaviors vary by ethnicity and child gender. Parenting. 2015;15:135–157. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2015.1053312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Moore MT. Confirmatory factor analysis. In: Hoyle R, editor. Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, Zeisel SA, Rowley SJ. Social risk and protective factors for African American children's academic achievement and adjustment during the transition to middle school. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:286–292. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Elder GH, Costello EJ. Cambridge University Press. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2001. Developmental science. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins S, Hill A. Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Castro VL, Halberstadt AG, Garrett-Peters P. A three-factor structure of emotion understanding in third-grade children. Social Development. 2016;25:602–622. doi: 10.1111/sode.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro VL, Halberstadt AG, Lozada FT, Craig AB. Parents' emotion-related beliefs, behaviors, and skills predict children's recognition of emotion. Infant and Child Development. 2015;24:1–22. doi: 10.1002/icd.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Bassett HH, Wyatt T. The socialization of emotional competence. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 614–637. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar AS, Perry NB, Cavanaugh AM, Leerkes EM. Maternal punitive reactions to children's negative emotions and young adult trait anger: Effect of gender and emotional closeness. Marriage & Family Review. 2015;51:229–245. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2015.1031421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Her P, Halberstadt AG, Perez-Rivera MB. Parents' beliefs about emotions and children's recognition of parents' emotions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2009;33:121–140. doi: 10.1007/s10919-008-0066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS. The development of children ages 6 to 14. The Future of Children. 1999;9:30–44. doi: 10.2307/1602703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Parents' reactions to children's negative emotions: Relations to children's social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development. 1996;37:2227–2247. doi: 10.2307/1131620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes R, Schaller M, Carlo G. The relations of parental characteristics and practices to children's vicarious emotional responding. Child Development. 1991;62:1393–1408. doi: 10.2307/1130814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Morris AS. Children's emotion-related regulation. In: Kail RV, editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 30. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 189–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot SN, Gresham FM, Freeman T, McCloskey G. Teacher and observer ratings of children's social skills: Validation of the social skills rating scales. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1998;6:152–161. doi: 10.1177/073428298800600206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Bernzweig J. The Coping with Children's Negative Emotions Scale: Procedures and scoring. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg N, Madden-Derdich DA. The Coping with Children's Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Psychometric properties and relations with children's emotional competence. Marriage & Family Review. 2002;34:285–310. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett-Peters PT, Castro VL, Halberstadt AG. Parents' belief about emotions, children's emotion situation knowledge, and classroom adjustment in third grade. Social Development in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord NK, Kitzmann KM, Coleman JK. Parents' and children's perceptions of parental behavior: Associations with children's psychosocial adjustment in the classroom. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:23–47. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0301_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O'Brien MU, Zins JE, Fredericks L, Resnik H, Elias MJ. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist. 2003;58:466–474. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliot SN. Social skills rating system: Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Eaton KL. A meta-analysis of family expressiveness and children's emotion expressiveness and understanding. Socialization of emotion expression and understanding in the family. Marriage and Family Review. 2002;34:35–62. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Parker AE, Castro VL. Nonverbal communication: Developmental perspectives. In: Hall JA, Knapp ML, editors. Handbook of Communication Science. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; 2013. pp. 93–128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israeli-Halevi M, Assor A, Roth G. Using maternal conditional positive regard to promote anxiety suppression in adolescents: A benign strategy? Parenting: Science and Practice. 2015;15 doi: 10.1080/15295192.2015.1053324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, MacKinnon DP. Parents' reactions to elementary school children's negative emotions: Relations to social and emotional functioning at school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48:133–159. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2002.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:706–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, Zeman J. Introduction to the special issue of social development: Emotion socialization in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2007;16:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00380.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Kazdin AE. Emotional/Behavioral problems in clinic and nonclinic children: Correspondence among child, parent and teacher reports. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:991–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt J, Stelter RL, Parker AE. Social Cognitive Skills Rating System. 2014 Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Lane KL, Wehby JH, Cooley C. Teacher expectations of students' classroom behavior across the grade span: Which social skills are necessary for success? Exceptional Children. 2006;72:153–167. doi: 10.1177/001440290607200202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Burt K, Coatsworth JD. Competence and psychopathology in development. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol 3: Risk, disorder and psychopathology. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 696–738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell DJ, Parke RD. Parental control and affect as predictors of children's display rule use and social competence with peers. Social Development. 2005;14:440–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabile SP, Oertwig D, Halberstadt AG. Parent emotion socialization and children's socioemotional adjustment: When is supportiveness no longer supportive? Social Development. 2016 doi: 10.1111/sode.12226. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mostow AJ, Izard CE, Fine S, Trentacosta CJ. Modeling emotional, cognitive, and behavioral predictors of peer acceptance. Child Development. 2002;73:1775–1787. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Halberstadt AG, Volling BL. Mother- and father-reported reactions to children's negative emotions: relations to young children's emotional understanding and friendship quality. Child Development. 2007;78:1407–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JA, Leerkes EM, Perry NB, O'Brien M, Calkins SD, Marcovitch S. European-American and African-American mothers' emotion socialization practices relate differently to their children's academic and social-emotional competence. Social Development. 2013;22:485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JA, Perry NB, O'Brien M, Calkins SD, Keane SP, Shanahan L. Mothers' and fathers' reports of their supportive responses to their children's negative emotions over time. Parenting. 2016;16:56–62. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2016.1116895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB, Vaden NA. Income level, gender, ethnicity, and household composition as predictors of children's school-based competence. Child Development. 1990;61:485–494. doi: 10.2307/1131109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrina S, Garcia-Linares MC, Casanova PF. Adolescents and their parents' perceptions about parenting characteristics. Who can better predict the adolescent's academic competence? Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:651–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(03)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons F, Harris PL, de Rosnay M. Emotion comprehension between 3 and 11 years: Developmental periods and hierarchical organization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2004;1:127–152. doi: 10.1080/17405620344000022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M, Halberstadt AG, Castro VL, MacCormack JK, Garrett-Peters P. Mothers' emotion regulation skills and beliefs about children's emotions predict children's emotion regulation skills. Emotion. 2016;16:280–291. doi: 10.1037/emo0000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudasill KM, Prokasky A, Tu X, Frohn SR, Sirota K, Molfese VJ. Parent vs. teacher ratings of children's shyness as predictors of language and attention skills. Learning and Individual Differences. 2014;34:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2014.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research. 2006;99:323–338. doi: 10.3200/joer.99.6.323-338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:906–916. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Zeman J, Nesin AE, Fitzgerald M. Children's strategies for displaying anger and sadness: What work with whom? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:100–122. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stelter RL, Halberstadt AG. The Coping with Children's Negative Emotions Scale. North Carolina State University; 2010. Coping with Children's Negative Emotions Scale: Revised with Sad and Angry. Unpublished scale adapted from Fabes, R.A., Eisenberg, N., & Bernzweig, J. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stettler N, Katz LF. Changes in parents' meta-emotion philosophy from preschool to early adolescence. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2014;14:162–174. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2014.945584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6th. Boston: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Carlson SM, Kesek A. The development of executive function in childhood. Handbook of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;2:553–574. doi: 10.1002/9780470996652.ch20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MS, McElwain N, Halberstadt AG. Parent, family, and child characteristics as predictors of mother- and father-reported emotion socialization practices. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:452–463. doi: 10.1037/a0015552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zins JE, Weissberg RP, Wang MC, Walberg HJ. Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? New York: Teachers College Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]