Introduction

For over a century, trans-vaginal hysterectomy (TVH) was the original minimally invasive surgical procedure before these terms were conceived and popularized to both patients and physicians. Today, many identify “minimally invasive hysterectomy” as laparoscopic and robotic assisted approaches despite the fact that TVH is without any incisions on the anterior abdominal wall and its structures. Therefore, perhaps it should be referred to as the “non-invasive hysterectomy.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), and committees on behalf of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) all vocalize their support of vaginal hysterectomy as the preferred approach for benign disease through position statements and other commentary reports.1–3 Reflected in the literature is a plethora of data that firmly support these groups’ assertions that vaginal hysterectomy offers the greatest benefit to patients with significantly lower rates of morbidity and mortality and to society with less cost.4–5 This article will review the historical evolution of hysterectomy and the evidence supporting vaginal hysterectomy for benign disease while emphasizing the absolute need to continue to develop residency and post-graduate training in the techniques.

A Historical Perspective

For most of the 20th century, the two modalities used to perform surgical removal of the uterus included the trans-abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) and the TVH. The evidence detailing the differences in patient experience between these two approaches was notable. With significantly lower rates of morbidity and mortality, encompassing outcomes such as febrile episodes, surgical blood loss and length of hospital stay, TVH remained the preferred modality.4 In 1984 the first laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) was reported in Germany by Kurt Semm ushering in a new era in hysterectomy.6 The further evolution toward total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) was published by Harry Reich and unleashed a move toward increased utilization of minimally invasive approaches to complete hysterectomy7 and for the next decade, laparoscopic approaches were added to the armamentarium of the gynecologist to remove uteri. However, during this time, the literature on costs, quality of life, and healthcare resource utilization remained in favor of the vaginal approach.8 In 2002, a case series of eleven patients was reported using laparoscopic hysterectomy with robotic assistance, thus broadening the methods available to remove uteri. Shortly thereafter, an intense marketing campaign was launched to persuade physicians to utilize technology in place of their vaginal and conventional laparoscopic skills without strong Level I evidence to support this change in surgical approaches.9

Defining “Technically Feasible”

In the ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444, the Committee on Gynecologic Practice concluded, “Vaginal hysterectomy is the approach of choice whenever feasible, based on its well-documented advantages and lower complication rates.”1 An important element to advancing the frequency of vaginal hysterectomy is a discussion of factors affecting the feasibility of the vaginal approach. Many physicians have incorrectly accepted certain patient characteristics as absolute contraindications in part due to the persuasive marketing campaigns that have been put forward to popularize other approaches, particularly robotic hysterectomy.

There are several common clinical conditions that physicians use to support a non-vaginal approach to hysterectomy, including large uteri, nulliparity or lack of previous vaginal delivery, and prior cesarean section or pelvic surgery. (See Figures 1–3.) The evidence in the literature, however, reports that these factors are not contraindications to vaginal hysterectomy.10–14 Further studies have shown that dedicated efforts to increase the utilization of the vaginal approach for hysterectomy have been notably successful and also refute that there are clinical criteria that are contraindications.15–16 Interestingly, the conclusion of Varma, et al, stated, “A major determinant of the route of hysterectomy is not the clinical situation but the attitude of the surgeon. There is no need for extra training and special skills or complicated equipment for vaginal hysterectomy.”16

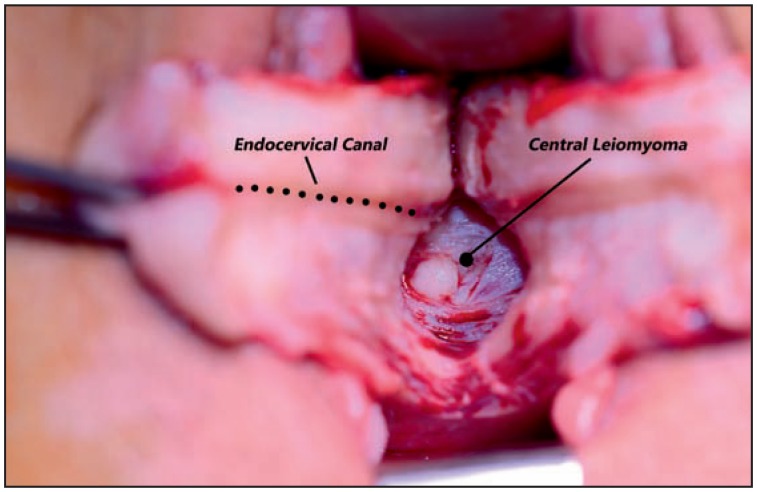

Figure 1.

shows a large leiomyoma with a bivalve approach to extraction.

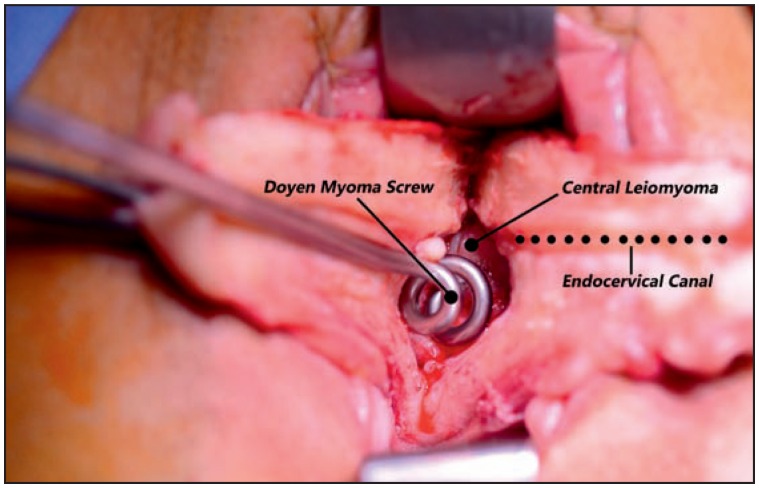

Figure 2.

shows the Doyen myoma screw that is essential for extraction.

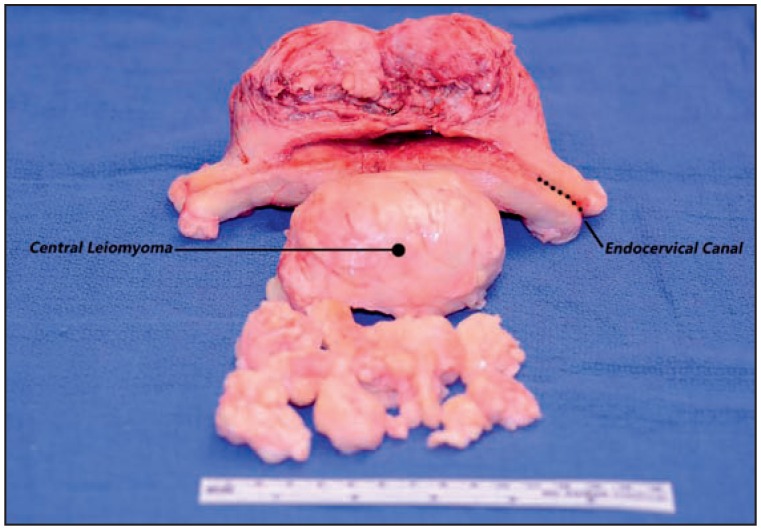

Figure 3.

shows the removed uterus and leiomyoma.

Advocating for the Best Outcomes and Value

The literature supports both the feasibility of vaginal hysterectomy, but also reveals the improved outcomes of this non-invasive approach. The most recent Cochrane review on hysterectomy in benign disease reports several statistically significant advantages of TVH over other approaches.4 Findings from the Cochrane review report improved outcomes with TVH including a quicker return to normal activities, shorter length of stay, and decreased reported pain ratings as opposed to TAH.4 In addition, it revealed advantages of TVH over TLH such as shorter operative times, a decrease in significant bleeding, and decreases in urinary tract injuries.4

Other studies report a decrease in vaginal cuff dehiscence with vaginal approaches over laparoscopic or robotic modalities. Although this is a rare complication, it can have dramatic implications for the patient, both physically and emotionally.17

When considering the most common gynecologic procedure performed in the United States, quality of outcomes, as well as the cost associated to achieve the quality, become critical elements. The concept of “value” in health care is one that physicians, patients, hospitals, and payers should have a vested interest in understanding yet documenting the link between healthcare dollars spent and patient outcomes remains an elusive task across many areas of medicine. However, large cross-sectional queries of national databases reveals that vaginal hysterectomy has the lowest mean charge per case with laparoscopic and abdominal approaches costing an additional ~$5000 per case and robotic approaches an astonishingly higher $16,000 per case.18 A large cohort study reported the average total cost of a robotic hysterectomy approached an additional $2200 per case over conventional laparoscopic methods without benefit of improved outcomes.19

Research on same-day vaginal hysterectomy has been performed revealing few perioperative complications and hospital readmissions, further establishing the financial benefit of vaginal hysterectomy in the setting of today’s finite supply of health care dollars.20 Indeed, payers have noted the relationship in this instance between outcomes and cost. United Healthcare recently took the initiative to cite the advantages for vaginal hysterectomy over laparoscopic or abdominal and announced their new policy effective April 2015 to require prior authorizations for all hysterectomies, except vaginal hysterectomy, performed on an outpatient basis.21

Residency and Post-Graduate Training in Vaginal Hysterectomy

In a society of medical professionals who rely heavily on the principles of evidence-based medicine, why must vaginal hysterectomy continue to be an “exception” to the decision-making algorithm?22 Given the evidence, what would lead surgeons to conclude that the best modality for benign indications is something other than the vaginal approach? The Education Committee for the SGS postulated three factors leading to the decline in performance of TVH, including inadequate residency surgical training, low volumes to maintain vaginal hysterectomy skill sets, and the marketing campaign that exists to promote other alternatives, potentially creating the façade that vaginal hysterectomy is “less attractive as a surgical option.”3

It is not surprising that Obstetrics and Gynecology (OBGYN) residents who report more training and performance of cases in residency indicate their training was adequate for future practice based on a recent survey of Chief residents in OBGYN US residency programs.23 They appear to understand the evidence in their 76% response that vaginal hysterectomy is the least invasive route for hysterectomy yet only 41% plan to utilize TVH as their preferred route once in future practice.23

Unfortunately, despite the existence of the Accreditation Committee for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the OBGYN Residency Review Committee (RRC) requirements for training in vaginal hysterectomy and the absence of any requirements for robotic hysterectomy training, the numbers of TVH procedures are declining.24–25 A multicenter retrospective cohort study conducted by the SGS Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network reported on the proportion of benign hysterectomies performed vaginally before and after introduction of robotic technology.25 Despite the clearly defined purpose of robotic technology as a way to replace abdominal hysterectomy modalities only, the authors actually described a decline in the performance of TVH from 42% to 30% after initiation of robotic hysterectomy.25 ACOG has recognized this educational crisis and need to devote a serious commitment to performance of TVH and developed a CME-accredited educational skills module and faculty development opportunities to guide teachers in training residents to perform TVH.26

Gynecologic patient volume for most physicians early in their practice is low, which further compounds the problem for the newly graduated resident to continue to refine and develop their vaginal hysterectomy skills. When new graduates have a senior partner proficient in TVH, they have a benefit of continuing to develop their skills under the guidance of more experienced hands. Furthermore, studies examining surgical volume reveal that perioperative morbidity and surgical complications were significantly lower in patients who were treated by high-volume vaginal surgeons.27 In addition, the cost and resources utilized by high volume surgeons are less compared to low volume surgeons.27 An acceptable practice might be an expectation or standard where patients are referred within networks to surgeons who have better expertise and are established as high-volume surgeons. Other authors and groups have previously made this recommendation, yet it remains to be seen if this framework will be adopted by the larger population of practicing OBGYN physicians.3, 28

Conclusion

Our surgical community must maintain its focus on sound rigorous research studies and not on the voices of the technology sales personnel or marketing campaigns when making appropriate decisions about the best surgical approaches for our patients. While it may seem intuitive that the marriage of improved technology with excellent surgeon technical skills would drive innovative health care that benefits our patients, a review of the history uncovers the need for our vigilance to maintain our reliance on evidence-based medicine. As David Nichols stated in the preface to the first edition of Vaginal Surgery, “A heritage all too readily lost, the techniques of vaginal surgery must be sought for, recorded carefully, and practiced, if competence and skills are to be maintained.”29 The educating surgeons and those mentoring practitioners newly in practice must remain committed and steadfast in their resolve to advance the preservation of technical skills in our residency graduates and practicing surgeons.

Biography

Dionysios K. Veronikis, MD, FACOG, FACS, MSMA member since 2010, is in the Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Mercy Hospital-St. Louis.

Contact: dveronikis@stlgynsurgery.com

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1156–1158. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c33c72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AAGL Advancing Mininally Invasive Gynecology World-wide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moen M, Walter A, Harmanli O, Cornella J, Nihira M, Gala R, Zimmerman C, Richter R. Considerations to improve the evidence-based use of vaginal hysterectomy in benign gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:585–588. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieboer T, Johnson N, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(3) Art. No.: CD003677. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dayaratna S, Goldberg J, Harrington C, Leiby B, McNeil J. Hospital costs of total vaginal hysterectomy compared with other minimally invasive hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:120, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparic R, Hudelist G, Beriasava M, Gudovic A, Buzadzic S. Hysterectomy throughout history. Acta Chir Lugosl. 2011;58(4):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reich H, DePaprio J, McGlynn F. Laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Surg. 1989;5:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Eeden S, Glasser M, Mathias S, Colwell H, Pasta D, Kunz K. Quality of life, health care utilization, and costs among women undergoing hysterectomy in a managed-care setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70633-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz-Arrastia C, Jurnalov C, Gomez G, Townsend C. Laparoscopic hysterectomy using a computer-enhanced surgical robot. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(9):1271–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8523-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doucette R, Sharp H, Alder S. Challenging generally accepted contraindications to vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1386–1391. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tohic A, Dhainaut C, Yazbeck C, et al. Hysterectomy for benign uterine pathology among women without previous vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:829–837. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181656a25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benassi L, Rossi T, Kaihura C, Ricci L, Bedocchi L, Galanti B, et al. Abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy for enlarged uteri: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1561–1565. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purohit R, Sharma J, Singh S, Giri D. Vaginal hysterectomy by electrosurgery for benign indications associated with previous cesarean section. J Gynecol Surg. 2013;29(1):7–12. doi: 10.1089/gyn.2012.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paparella P, Sizzi O, Rossetti A, De Benedittis F, Paparella R. Vaginal hysterectomy in generally considered contraindications to vaginal surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;270(2):104–109. doi: 10.1007/s00404-003-0505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosson M, Querleu D, Subtil D. The feasibility of vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:95–99. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varma R, Tahseen S, Lokugamage A, Kunde D. Vaginal route as the norm when planning hysterectomy for benign conditions: change in practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(4):613–616. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hur H, Guido R, Mansuria S, Hacker M, Sanfilippo J, Lee T. Incidence and patient characteristics of vaginal cuff dehiscence after different modes of hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(3):311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen S, Vitonis A, Einarsson J. Updated hysterectomy surveillance and factors associated with minimally invasive hysterectomy. JSLS. 2014;18(3) doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright J, Ananth C, Lwein S, Burke W, Lu Y, Neugut A, Herzog T, Hershman D. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA. 2013;309(7):689–698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zakaria M, Levy B. Outpatient vaginal hysterectomy: optimizing perioperative management for same-day discharge. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1355–1361. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e3182732ece. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United Healthcare Network Bulletin. Jan, 2015. Available from https://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/News/January_2015_Network_Bulletin.pdf.

- 22.Julian T. Vaginal hysterectomy. An apparent exception to evidence-based decision making. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:812–3. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816bfe45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antosh D, Gutman R, Iglesi C, Sokol A, Park A. Resident opinions on vaginal hysterectomy training. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17(6):314–317. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31823a08bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burkett D, Horwitz J, Kennedy V, Murphy D, Graziano S, Kenton K. Assessing current trends in resident hysterectomy training. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:210–214. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3182309a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeppson P, Rahimi S, Gattoc L, Westermann L, Cichowski S, Raker C, Lebrun E, Sung V. Impact of robotic technology on hysterectomy route and associated implications for resident education. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):196.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosworth T. ACOG taking steps to increase vaginal hysterectomy rates. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.obgynnews.com/focus-on/single-view/acog-taking-steps-to-increase-vaginal-hysterectomy-rates/d78b8bea4aa3483c10dc5d843207d211.html.

- 27.Rogo-Gupta L, Lewin S, Kim J, Burke W, Sun X, Herzog T, Wright J. The effect of surgeon volume on outcomes and resource use for vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1341–1347. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fca8c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vree F, Cohen S, Chavan N, Einarsson J. The impact of surgeon volume on perioperative outcomes in hysterectomy. JSLS. 2014;18(2):174–181. doi: 10.4293/108680813X13753907291594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nichols D. Vaginal Surgery. The Williams and Wilkins Company; 1976. [Google Scholar]