Abstract

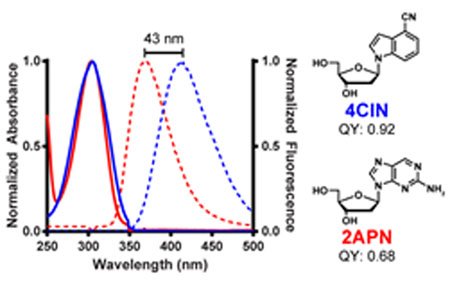

The synthesis and characterization of a universal and fluorescent nucleoside, 4-cyanoindole-2ʹ-deoxyribonucleoside (4CIN), and its incorporation into DNA is described. 4CIN is a highly efficient fluorophore with quantum yields >0.90 in water. When incorporated into duplex DNA, 4CIN pairs equivalently with native nucleobases and has uniquely high quantum yields ranging from 0.15–0.31 depending on sequence and hybridization contexts, and surpassing that of 2-aminopurine, the prototypical nucleoside fluorophore. 4CIN constitutes a new isomorphic nucleoside for diverse applications.

Graphical abstract

Fluorescent nucleosides are powerful tools for a variety of applications in chemical biology.1,2 The isomorphic and fluorescent nucleoside analogue, 2-aminopurine (2APN, Figure 1), is arguably the most widely utilized of such compounds. 2APN’s environment sensitive fluorescence has been used to study polymerases,3–5 base-flipping enzymes,6 DNA dynamics,7 DNA mismatches,8 riboswitches,9,10 and electron transfer in DNA,11 and its continual use has sustained experimental and computational studies of the molecule itself.12–19 Limitations of 2APN include a 5-step chemical synthesis from guanosine (one step synthesis from thioguanosine),20,21 a modest Stokes shift, and strong fluorescence quenching in DNA.11,18,22 Consequently, highly fluorescent isomorphic nucleosides with improved fluorescence properties in DNA are desired, with notable recent advances.1,2,23–25

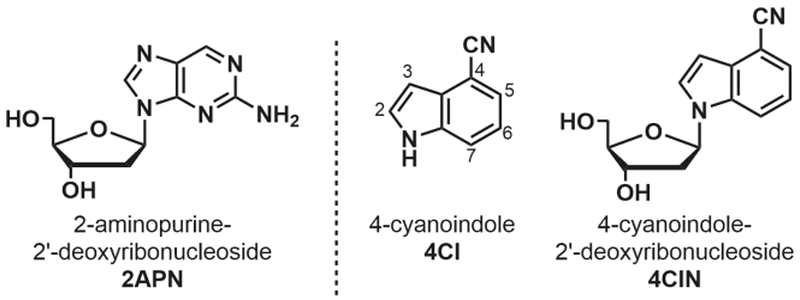

Figure 1.

Structures of 2APN, 4CI (with indole numbering) and 4CIN

Indole is a privileged sc affold for native nucleobases (e.g., adenine and guanine),26,27 and amino acids (e.g., tryptophan). Recently, cyano-functionalized indoles have proven interesting as fluorescent tryptophan mimics.28–31 4-cyanoindole (4CI, Figure 1) has demonstrated the most impressive properties among the cyanoindoles in terms of fluorescence intensity, red-shifted excitation and emission wavelengths, and Stokes shift.28 Herein, we report the application of the 4CI fluorophore to the development of a fluorescent, isomorphic nucleoside analogue, 4-cyanoindole-2ʹ-deoxyribonucleoside (4CIN, Figure 1), with significantly enhanced fluorescence properties compared to 2APN.

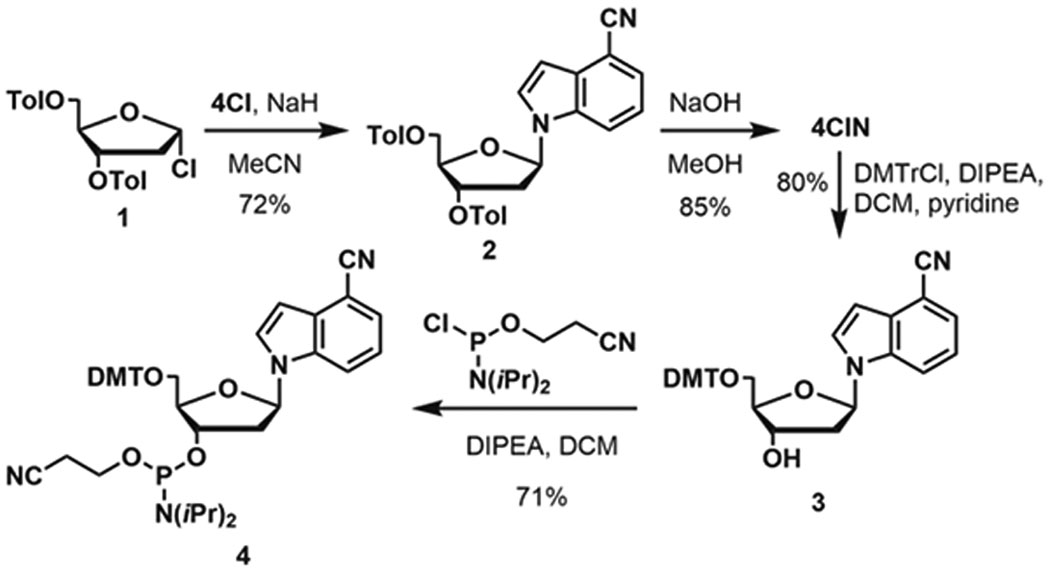

4CIN is synthesized in two steps starting from 4CI and commercially available 3,5-di-O-toluoyl-α−1-chloro-2-deoxy-D-ribofuranose (1) (Scheme 1).33 Elaboration to the phosphoramidite for oligonucleotide synthesis follows a two-step sequence of 4,4ʹ-dimethoxytrityl protection of the 5ʹ-alcohol to yield 3, followed by formation of phosphoramidite 4 using 2-cyanoethyl-N,Nʹ-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite. The 4CIN phosphoramidite can be synthesized in four steps at 35% overall yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 4CIN and phosphoramidite 4.

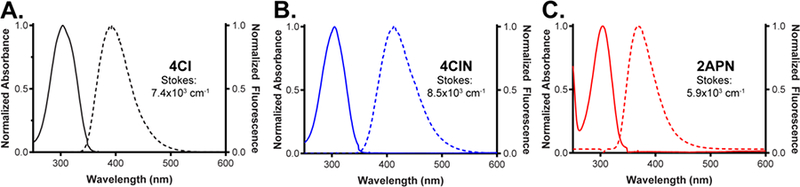

We first studied 4CIN and benchmarked it to 2APN by evaluating absorption and emission spectra (Figure 2, maxima in Table 1). Nucleobases 4CI (Figure 2A) and 2-aminopurine base (Figure S1A) share similar maximum absorbance wavelengths (304 nm and 305 nm, respectively), but 4CI emits at 393 nm in comparison to 2-aminopurine base at 373 nm. In a nucleoside context, 2APN (Figure 2C) has no change in its absorbance or emission properties relative to the nucleobase, whereas 4CIN has a large emission shift with a maximum at 412 nm.18,34

Figure 2.

Normalized absorbance (left axis, solid curve) and fluorescent emission (right axis, dotted curve) spectra of compounds and Stokes shifts.32 Fluorescence spectra were collected by exciting at the absorption maximum. All compounds were dissolved in distilled and deionized H2O.

Table 1.

Spectral and fluorescent properties of 4CI, 4CIN, and 2APN.

| sample | solvent | λex, maxa | λem, max | ε305 nm (M−1cm−1) | τ (ns) | QY (270 nm)b | QY (305 nm)c | QY (325 nm)c | Φεd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4CI | H2O | 304 | 393 | 8056e | 9.0f | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 5880 |

| 4CIN | H2O | 305 | 412 | 7790 ± 320 | 10.1 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 7160 |

| 4CIN | PBS | 305 | 412 | 7880 ± 120 | 10.0 | ND | 0.90 ± 0.01 | ND | 7100 |

| 4CIN | THF | 305 | 381 | 8030 ± 180 | 5.6 | ND | 0.64 ± 0.02 | ND | 5140 |

| 2APN | PBS | 303 | 369 | 5000–6000g | 11h | ND | 0.61 ± 0.01i | ND | ND |

Only local maxima greater than 250 nm are listed.

Calculated relative to Trp in water.

Calculated relative to QS in aqueous 0.105 M HClO4 (pH =1).

Brightness is calculated by multiplying ε305 and QY305.

Literature value for 4CI in water.31

Our measurement is listed. Literature value for 4CI in water is 9.1 ns.31

Literature value for 2APN in water.13

Our measurement is listed. Literature value in buffered solution is 0.68.18

ND = not determined. PBS used at pH = 7. See Supporting Information for experimental details.

4CIN was then evaluated to determine molar extinction coefficients (ε), fluorescence lifetimes (τ), and relative quantum yields (QYs) in multiple solvents. The extinction coefficient at 305 nm for 4CI was previously reported as 8056 M−1cm−1.31 We calculated the ε305 for 4CIN (H2O) to be 7790 ± 320 M−1cm−1 (Table 1). We also calculated ε305 for 4CIN in different solvents (e.g., PBS and THF), finding similar absorbance properties. Fluorescent lifetimes were measured on a time-resolved fluorometer35 by exciting at 355 nm, and relative to 4CI31 we found 4CIN observed only a small lengthening of τ to approximately 10 ns in aqueous solutions, although in THF, the lifetime drops to 5.6 ns. Relative QYs were collected for 4CI, 4CIN, and 2APN utilizing previously described protocols and L-tryptophan (Trp, Figure S1B) and quinine sulfate (QS, Figure S1C) as standards.36 Our measurements for 4CI (0.86 at 270 nm; 0.73 at 305 nm; 0.76 at 325 nm) were consistent with a previous report (0.85 at 270 nm; 0.78 at 325 nm).31 Commercial 2APN was also subjected to this procedure yielding a relative QY of 0.61 at 305 nm, which agrees well with the accepted value of 0.68.18 4CIN yielded remarkably improved QY properties over 4CI, with marked increases in QY at both 305 nm and 325 nm to 0.92, while at 270 nm no change was observed (0.85 at 270 nm). In PBS-buffered conditions, we found minimal changes relative to deionized water and again in THF we observed fluorescence quenching (Table 1).

Phorphoramidite 4 was next utilized to synthesize 4CIN-functionalized oligonucleotides ODN1 and ODN2 (Figure 3A), where sequences were chosen to complement our previous studies of other nucleotides.37 First, the relative thermal stabilities of model DNA sequences containing X = 4CIN, 2APN, and 5-NO2-indole and Y = A, C, G, or T were determined using UV thermal melting experiments (data shown in Table S1).37 While no ODN1 DNA duplex was more stable than those containing either a central G-C or A-T pair (Tms = 57.3 °C and 52.6 °C, respectively), modified ODN1 duplexes showed similar thermal stabilities to that of G- and A- mismatches which range from 42.5 – 47.4 °C. 4CIN modified ODN1 duplexes showed thermal stability in the narrow range of 41.4 – 43.5 °C, while 2APN-modified ODN1 duplexes yielded a similar melting temperature range of 43.4 – 44.5 °C, with the exception of 2APN’s preferred pair with Y = T (Tm = 49.8 °C).38,39 These data suggests that 4CIN exhibits similar, non-discriminatory hybridization properties as 5-NO2-indole, a universal hydrophobic base,40 which hybridizes with all base pairs in a similar thermal range (Tm range: 44.7 – 49.8 °C). Given the similarities between 4CI and 5-NO2-indole nucleobases (e.g. hydrophobic and lack of H-bond donors and acceptors), we hypothesize that 4CI adopts similar duplex DNA conformations as 5-NO2-indole,26 but with the nitrile positioned towards the DNA major groove. ODN2 was evaluated similarly (Figure 3A, Table S1), but modifications were made only on the 5ʹ-terminus and paired only against T. All modified ODN2 duplexes were similarly stable to that containing a natural A-T pair (Tm range: 52.0 – 54.9 °C)

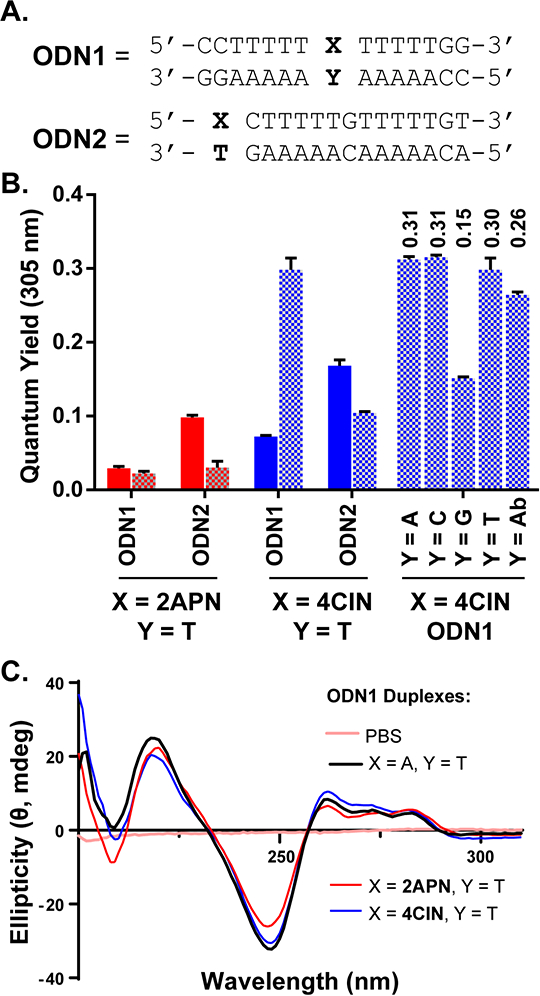

Figure 3.

A. DNA utilized as either single- or double-stranded. Double-stranded DNA was annealed in PBS (pH = 7). B. Quantum yields (305 nm) of ODN1 and ODN2 single-strands (top strand only) and duplexes. QYs measured in PBS (pH = 7) at 25 °C relative to QS in aqueous 0.105 M HClO4 (pH = 1). Mean ± SD (n = 3) is shown. Single-stranded DNA in solid bars. Double-stranded DNA in patterned bars. C. Circular dichroism spectra (200 nm – 310 nm) of ODN1 duplexes (15 nmol) in PBS (pH = 7).

The fluorescent properties of nucleosides can change in a DNA context, and thus we analyzed modified duplex ODN1 and ODN2 for changes in emissive properties. 2APN is known to have shifted emission properties when incorporated into oligonucleotides,18 and we observed similar results with 4CIN. While both single- and double-stranded ODN2 modified with 4CIN saw little change in fluorescence maxima, 4CIN-modified ODN1 observed a lowered fluorescence maximum to 403 nm in single-stranded DNA and between 380–390 nm in duplex DNA depending on the base pair (Figure S2). The fluorescent DNAs were then evaluated to ascertain relative QYs at 305 nm in PBS buffer, both as a single-strand and in a double-stranded helix (Figure 3B). 2APN, like most fluorescent nucleoside analogues, observes significant quenching in DNA,18 lowering its nucleoside QY of 0.68 to 0.029 and 0.098 depending on whether it is placed centrally or terminally in our model single-stranded DNAs. In duplex DNA, a similar trend follows, where quenching is enhanced, resulting in lowered QYs for both 2APN modified duplexes. 4CIN modified single-stranded DNAs follow a similar trend, with QYs lowered to 0.072 and 0.168 in ODN1 and ODN2, respectively, although these values are a two-fold enhancement relative to those modified with 2APN (Figure 3B). In a DNA duplex, however, 4CIN follows a remarkably different trend. While both modified ODN2 duplexes observe an expected QY reduction, 4CIN-modified ODN1 (duplex) observes a QY increase to 0.30. Investigation of the sequence dependence of this trend, pairing ODN1 (X = 4CIN) against Y = A, C, G, and T (Figure 3B, right), revealed the QY remains constant, with the exception of when 4CIN is paired against G, which is consistent with other reports that G can quench fluorescence.43,44 Against a 2ʹ-deoxyribose spacer meant to mimic an abasic site (Y = Ab, see Supporting Information; Tm = 39.9 °C for ODN1 X = 4CIN, Y = Ab), 4CIN remains highly fluorescent. Given the expected trend of enhanced quenching in duplex DNA, these properties of 4CIN are unique. Further evaluations of sequence effects on 4CIN’s fluorescence properties are needed in future studies since the 3ʹ and 5ʹ nucleotides to a fluorophore in an oligonucleotide can have various effects on the fluorescent reporter.22,45–48

To rule out gross changes in duplex DNA structure as a result of 4CIN incorporation, we performed circular dichroism (CD) measurements of modified ODN1 (Figure 3C). CD analysis complements the thermal stability data and again shows these DNAs are quite stable and their overall helicity is not changed. The CD spectra of duplex ODN1 (X = A, Y = T) resembles that of a typical poly[A]poly[T] sequence (deep 245 nm band and weaker 260–280 nm bands),49 and with only minor perturbations observed between ODN1 modified with either X = 2APN or 4CIN paired against Y = T. We conclude that no gross changes in DNA structure occurred with these modifications. However, more quantitative studies of 4CIN akin to those reported with 2APN50 would be useful to characterize those perturbations to duplex DNA structure resulting from 4CIN incorporation that are not evident in CD and thermal melting experiments. Nonetheless, our investigation has demonstrated that 4CIN modified oligonucleotides may be able to discriminate between single- and double-stranded DNA, as 4CIN fluorescence increases when hybridized (and not positioned at a terminus). Additional studies are needed to further interrogate this promising application of 4CIN since our conclusions are based on data from two 4CIN-modified DNA sequences.

In summary, we have shown that 4CIN is a readily synthesized, highly fluorescent nucleoside analogue with a red-shifted maximum emission (412 nm) and high quantum yield (>0.90 at 305 nm). In addition, 4CIN has unique fluorescence characteristics when incorporated (non-terminally) into oligonucleotides, including enhanced QYs (range: 0.15 – 0.31) when incorporated into our model double-stranded sequences in comparison to single-stranded sequences. Taken together, 4CIN’s impressive fluorescence properties give it the potential to serve as a useful probe for various chemical and biological studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank David Cullen (University of Minnesota, UMN) for assistance performing the DNA thermal melting experiments shown in Table S1. This work was supported by NIH R01-GM110129 and R01-GM118000 and a 3M Graduate Research Fellowship to KTP. Mass spectrometry was performed at the Analytical Biochemistry Core Facility of the UMN Masonic Cancer Center, which is supported by the NIH (P30-CA77598). Fluorescence lifetime and circular dichroism experiments were performed at the UMN Biophysical Technology Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.Supporting figures and table, experimental procedures, and spectral characterization data (PDF)

REFERENCES

- 1.Xu W; Chan KM; Kool ET Nat. Chem 2017, 9, 1043–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinkeldam RW; Greco NJ; Tor Y Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 2579–2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyce CM; Potapova O; DeLucia AM; Huang XW; Basu VP; Grindley ND F. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 6103–6116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochstrasser RA; Carver TE; Sowers LC; Millar DP Biochemistry 1994, 33, 11971–11979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandwar RP; Patel SS J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276, 14075–14082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holz B; Klimasauskas S; Serva S; Weinhold E Nucleic Acids Res 1998, 26, 1076–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordlund TM; Andersson S; Nilsson L; Rigler R; Graslund A; Mclaughlin LW Biochemistry 1989, 28, 9095–9103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guest CR; Hochstrasser RA; Sowers LC; Millar DP Biochemistry 1991, 30, 3271–3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert SD; Stoddard CD; Wise SJ; Batey RT J. Mol. Biol 2006, 359, 754–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemay JF; Penedo JC; Tremblay R; Lilley DMJ; Lafontaine DA Chem. Biol 2006, 13, 857–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley SO; Barton JK Science 1999, 283, 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rachofsky EL; Osman R; Ross JB A. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 946–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lobsiger S; Blaser S; Sinha RK; Frey HM; Leutwyler S Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jean JM; Hall KB Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans K; Xu D; Kim Y; Nordlund TM J. Fluoresce 1992, 2, 209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broo A J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 526–531. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmen A; Norden B; Albinsson BJ Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 3114–3121. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward DC; Reich E; Stryer LJ Biol. Chem 1969, 244, 1228–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smagowicz J; Wierzchowski KL J. Lumin 1974, 8, 210–232. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doudna JA; Szostak JW; Rich A; Usman N J. Org. Chem 1990, 55, 5547–5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mclaughlin LW; Leong T; Benseler F; Piel N Nucleic Acids Res 1988, 16, 5631–5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben Gaied N; Glasser N; Ramalanjaona N; Beltz H; Wolff P; Marquet R; Burger A; Mely Y Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, 1031–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin D; Sinkeldam RW; Tor Y J.Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 14912–14915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sholokh M; Sharma R; Shin D; Das R; Zaporozhets OA; Tor Y; Mely Y J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 3185–3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilin V; Gavvala K; Barthes NPF; Michel BY; Shin DW; Baudier C; Mauffret O; Yashchuk V; Mousli M; Ruff M; Granger F; Eiler S; Bronner C; Tor Y; Burger A; Mely Y J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2520–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loakes D; Hill F; Brown DM; Salisbury SA J. Mol. Biol 1997, 270, 426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loakes D Nucleic Acids Res 2001, 29, 2437–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilaire MR; Mukherjee D; Troxler T; Gai F Chem. Phys. Lett 2017, 685, 133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talukder P; Chen SX; Roy B; Yakovchuk P; Spiering MM; Alam MP; Madathil MM; Bhattacharya C; Benkovic SJ; Hecht SM Biochemistry 2015, 54, 7457–7469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markiewicz BN; Mukherjee D; Troxler T; Gai FJ Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilaire MR; Ahmed IA; Lin CW; Jo H; DeGrado WF; Gai F Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6005–6009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stokes shift was calculated by converting the maximum absorption wavelength and maximum emission wavelength into wavenumber (cm−1) and then subtracting the two values.

- 33.Girgis NS; Cottam HB; Robins RK J. Heterocyclic Chem 1988, 25, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The quantum yield (QY) standards utilized in this study were also analyzed and shown in Figure S1.

- 35.Muretta JM; Kyrychenko A; Ladokhin AS; Kast DJ; Gillispie GD; Thomas DD Rev. Sci. Instrum 2010, 81,103101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wurth C; Grabolle M; Pauli J; Spieles M; Resch-Genger U Nat. Protoc 2013, 8, 1535–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Struntz NB; Harki DA ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 1631–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe SM; Goodman MF Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1981, 78, 2864–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sowers LC; Fazakerley GV; Eritja R; Kaplan BE; Goodman MF Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 5434–5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loakes D; Brown DM Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4039–4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mikhaylov A; de Reguardati S; Pahapill J; Callis PR; Kohler B; Rebane A Biomed. Opt. Express 2018, 9, 447–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albert A; Taguchi H J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 2 1973, 1101–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seidel CAM; Schulz A; Sauer MH M. J. Phys. Chem 1996, 100, 5541–5553. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinlein T; Knemeyer JP; Piestert O; Sauer MJ Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 7957–7964. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawkins ME; Pfleiderer W; Jungmann O; Balis FM Anal. Biochem 2001, 298, 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wranne MS; Fuchtbauer AF; Dumat B; Bood M; El-Sagheer AH; Brown T; Graden H; Grotli M; Wilhelmsson LM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9271–9280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandin P; Wilhelmsson LM; Lincoln P; Powers VEC; Brown T; Albinsson B Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, 5019–5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burns DD; Teppang KL; Lee RW; Lokensgard ME; Purse BW J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 1372–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kypr J; Kejnovska I; Renciuk D; Vorlickova M Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 1713–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dallmann A; Dehmel L; Peters T; Mugge C; Griesinger C; Tuma J; Ernsting NP Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 5989–5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.