Abstract

Cholesterol-containing soft drusen and subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDDs) occur at the basolateral and apical side of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), respectively, in the chorioretina and are independent risk factors for late age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Cholesterol in these deposits could originate from the RPE as nascent HDL or apoB-lipoprotein. We characterized cholesterol efflux and apoB-lipoprotein secretion in RPE cells. Human RPE cells, ARPE-19, formed nascent HDL that was similar in physicochemical properties to nascent HDL formed by other cell types. In highly polarized primary human fetal RPE (phfRPE) monolayers grown in low-lipid conditions, cholesterol efflux to HDL was moderately directional to the apical side and much stronger than ABCA1-mediated efflux to apoA-I at both sides; ABCA1-mediated efflux was weak and equivalent between the two sides. Feeding phfRPE monolayers with oxidized or acetylated LDL increased intracellular levels of free and esterified cholesterol and substantially raised ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux at the apical side. phfRPE monolayers secreted apoB-lipoprotein preferentially to the apical side in low-lipid and oxidized LDL-feeding conditions. These findings together with evidence from human genetics and AMD pathology suggest that RPE-generated HDL may contribute lipid to SDDs.

Keywords: adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter A1, apolipoprotein B, high density lipoproteins, oxidized lipids, age-related macular degeneration, soft drusen, subretinal drusenoid deposits, cell polarization

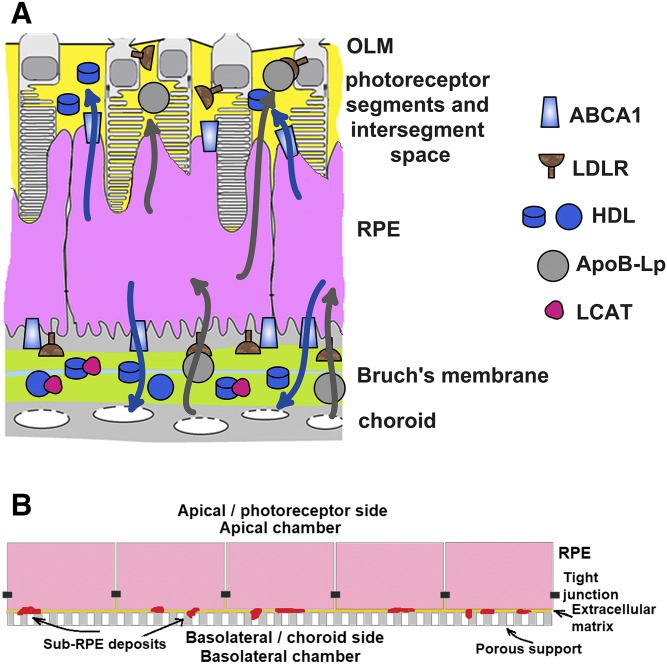

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of vision loss in individuals 50 years of age and older (1). The pathogenesis of AMD involves abnormal deposition of lipid in the chorioretina (1–3). Soft drusen and subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDDs) form, respectively, at the basolateral side of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the Bruch’s membrane and at the apical side of the RPE in the photoreceptor segment layer (PSL) (Fig. 1A; Refs. 2–5). In transmission electron microscopy images, both types of deposit appear to consist mostly of membranous material (6–8). Soft drusen contain large amounts of phospholipid and esterified and free cholesterol and immunologically stain for apoE, apoB, and apoA-I (9–13). SDDs contain free cholesterol and stain for apoE (14, 15). Soft drusen usually reside in the cone photoreceptor-dominated center of the macula, while SDDs are located in the outer macula, which is dominated by rod photoreceptors (16, 17). Soft drusen and SDDs can occur together in the same eye or alone and are independent risk factors for late AMD (16–19).

Fig. 1.

The RPE in vivo and in a polarized culture in vitro. A: Tissues surrounding the RPE in the eye and the proposed flow of lipid in HDL (blue arrows) and LDL (gray arrows) particles. A multi-layer extracellular matrix called the Bruch’s membrane separates the basolateral membrane of the RPE from the basolateral membrane of choroid endothelium. The Bruch’s membrane consists of the basement membranes of the RPE and of the choroid endothelium, the inner and outer collagenous layers (ICL and OCL, respectively), and a central band of elastic fibers (not labeled in the schematic). Plasma lipoproteins (i.e., HDL and LDL) and enzymes (e.g., LCAT) can readily enter the Bruch’s membrane through the fenestrae in the choroid endothelium and reach the RPE basolateral membrane. The apical membrane of the RPE faces the PSL, which contains photoreceptor outer segments (gray) imbedded in the interphotoreceptor matrix (yellow). The PSL milieu is isolated by tight junctions between RPE cells and between photoreceptor cell bodies and Müller cell processes. Photoreceptor cell bodies and Müller cell processes form the external limiting membrane (OLM). B: The RPE grown on inserts in a polarized culture in vitro.

Recent studies indicate that deposition of lipid in the chorioretina is an etiologic factor in AMD (20, 21). The causal candidate genes in four (ABCA1, APOE, CETP, and LIPC) of the 34 loci associated with AMD have well-established functions in the metabolism of HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) (22). The AMD-associated variants at those four loci are also associated with HDL-C levels (23, 24). A Mendelian randomization study has found a direct relationship between HDL-C levels and AMD risk (24). However, HDL-C is not always associated with AMD risk in epidemiologic studies, possibly because the relationship between the two is not continuous over the whole range of HDL-C concentrations (25). A similarly multifaceted relationship exists between HDL-C and cardiovascular disease: HDL-C is a biomarker of HDL functional properties in the normal range of concentrations and a causative atherogenic factor at high concentrations (26, 27).

RPEs are exposed to different lipoprotein environments at the basolateral and apical sides. Lipoprotein from the systemic circulation enters the Bruch’s membrane through the fenestrated endothelium of the choriocapillaris and contacts the basolateral side of the RPE (4). Tight junctions between RPE cells comprise the outer blood-retinal barrier and, together with tight junctions between photoreceptor bodies and Müller cell processes, limit access to the PSL (Fig. 1A; Refs. 28, 29). A large fraction of the PSL by volume consists of the interphotoreceptor matrix, which contains lipoprotein secreted by the RPE, photoreceptors, and Müller cells (30, 31). The PSL lipoprotein contacts the apical side of the RPE. The oxidative environment may facilitate rapid chorioretinal lipid oxidation (32). RPE cells avidly take-up oxidized LDL (oxLDL) (33–35). Cholesterol taken-up with oxLDL can be stored as cholesteryl ester, catabolized to hydroxycholesterol (primarily 5-cholestenoic acid in the RPE), or released back into the extracellular milieu (21, 36). Cholesterol can be released with nascent HDL or with apoB-lipoprotein. The RPE expresses ABCA1 for nascent HDL formation and apoB and microsomal transfer protein (MTP) for apoB-lipoprotein secretion (21). ABCA1 is present in the basolateral and apical membranes of the RPE (31, 37). In several epithelial cell types that contain ABCA1 in both membranes (e.g., MDCK), ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to the basolateral side is stronger than to the apical side (38–40). Whether this is the case in RPE cells has not been determined. The directionality of apoB secretion is also not known, although a preferential release to the basolateral side has been suggested (20, 21). We investigated cholesterol efflux in primary human fetal RPE (phfRPE) monolayers. In phfRPE monolayers kept in a regular medium, ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux at the basolateral side was equivalent to ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux at the apical side, while apoB secretion was stronger at the apical side. In phfRPE monolayers fed with either oxLDL or acetylated LDL (acLDL) to elevate intracellular cholesterol levels, ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux at the apical side was significantly stronger than at the basolateral side, while apoB secretion remained stronger at the apical than at the basolateral side. These findings illuminate cholesterol metabolism in the RPE and contribute to our understanding of AMD pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ARPE-19 and primary RPE culture

ARPE-19 cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-2302) and routinely maintained in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Highly-polarized primary RPE monolayers were established using donor fetal eyes as previously described (41). Each eye was placed in an antibiotic-antimycotic solution and rinsed with Hank’s buffered salt solution. The eyes were pinned onto a dissection stage, and the corneas, vitreous, and lenses were removed. The open eyes were transferred into room temperature Dispase solution and incubated in RPE medium/5% FBS for 90 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. The RPE medium was prepared as previously described (41). The retina was removed, and the RPE was peeled off the choroid-scleral tissue. The RPE layer was collected into a 15 ml conical tube, gently shaken, and trypsinized to release RPE cells. The cells were centrifuged, washed, transferred to a T-25 flask, and cultured in RPE medium/15% FBS for 1 week and then in RPE medium/5% FBS for 1 month. By this time, the RPE cells were highly pigmented and confluent at about 500,000 cells/cm2. The cells were transferred onto 0.4 μm pore size polycarbonate 12-well plate inserts (Corning Transwell) that were coated with human extracellular matrix, cultured for 5 weeks in RPE medium/15% FBS and then maintained in RPE medium/2% FBS. The barrier function of the RPE monolayer was assessed by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER). Only bilayers with TEER >450 Ω·cm2 were used in experiments.

Phagocytosis assays

phfRPE cells were plated on Matrigel (Corning)-coated 8-well chamber slides and allowed to grow for 4 weeks. Phagocytosis assay was performed using pHrodo Red Escherichia coli BioParticles Conjugate (Thermo Fisher). pHrodo particles were resuspended at 1 mg/ml in the RPE medium, vortexed, sonicated, and then added to phfRPE monolayers and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The pHrodo particle-containing medium was removed, and the cells were washed thrice with PBS and incubated in fresh RPE medium for an additional 24 h. The slides were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min, washed with PBS, treated with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen), and imaged on an inverted microscope (Leica DI8; Leica instruments).

Cell cholesterol efflux assays for ARPE-19 cells

Cholesterol efflux assays were conducted as previously described (42). ARPE-19 cells were plated in 24-well plates at 1/7 dilution from confluent flasks in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% FBS, allowed to attach overnight, and labeled with 1 μCi/ml [1,2-3H(N)]cholesterol (PerkinElmer) in DMEM/F12/2.5% FBS overnight. The cells were then incubated with 2 μM T0901317 in DMEM/F12/0.2% BSA (fraction V, fatty acid free; EMD Millipore) for 18 h to upregulate ABCA1 expression, pretreated with an efflux inhibitor (20 μM probucol or 1 μM BLT-1) or with a corresponding vehicle for 1 h in DMEM/F12, and exposed to a cholesterol acceptor (10 μg/ml human lipid-free apoA-I or 100 μg/ml human HDL; HDL was used within a month of preparation) in the presence of T0901317 and the same cholesterol efflux inhibitor or vehicle as during the pretreatment in DMEM/F12 for 4 h. apoA-I and HDL were isolated by the guanidine hydrochloride method (43) and by ultracentrifugation (42), respectively. At the end of the efflux period, subsamples of cell medium were filtered through a 0.45 μm MultiScreen-HV filter plate (EMD Millipore) and read in a scintillation counter. Cell lipids were extracted with hexane-isopropanol (3:2, v/v) and, after evaporating the solvent, read in a scintillation counter. Cellular cholesterol efflux was calculated as the percent of counts released to medium from the total counts in medium and cells.

Nascent HDL formation and analysis by gel filtration

ARPE-19 cells were plated in T-75 flasks (five flasks per treatment) in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, incubated overnight, labeled with 0.12 μCi/ml [4-14C]cholesterol and 1.3 μCi/ml [methyl-3H]choline chloride or kept without a radiolabel in DMEM/F12/2.5% FBS for 24 h and then grown in the presence of either 2 μM T0901317 or vehicle in DMEM/F12/0.2% BSA for 18 h. In some cases, the cells were then pretreated with 20 μM probucol or vehicle for 1 h in DMEM/F12 and then exposed to 5–10 μg/ml human radiolabel-free or [14C]-labeled apoA-I (labeled to ∼1 μCi/mg as described previously; Ref. 42) for 8 or 18 h in the presence of T0901317, probucol, or vehicle in DMEM/F12. In other cases, the pretreatment with probucol was omitted. At the end of the HDL formation period, cell medium was collected, filtered through a 0.45 μm PVDF syringe filter (EMD Millipore), and concentrated 33× to 1.5 ml using 10,000 NMWL PLGC centrifugal filters (EMD Millipore). The samples were stored at 4°C for no longer than 2 weeks before further processing. The concentrated samples (1.2 ml) were resolved according to size on a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 gel-filtration column operated by an ÄKTA FPLC system with an automatic fraction collector (all from GE Healthcare). TBS/EDTA buffer [10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4)] was the mobile phase. One milliliter elution fractions were collected and read in a scintillation counter. Spill-overs of 3H counts into the 14C energy window and vice versa were reduced by minimizing the 3H and 14C energy windows. Counts per minute values were further adjusted to account for the 3H and 14C energy spectra overlap.

Simultaneous cholesterol efflux to the basolateral and apical media from the phfRPE monolayer

RPE monolayers were labeled with 1–2 μCi/ml [1,2-3H(N)]cholesterol in the RPE medium (41) supplemented with 2–5% FBS overnight, incubated with 2 μM T0901317 in RPE medium supplemented with 2% FBS or 0.2% BSA for 16–18 h, and exposed to 10 μg/ml apoA-I, 100 μg/ml HDL, or medium without cholesterol acceptors for 4 h. The same amount of medium (900 μl) containing the same concentration of [1,2-3H(N)]cholesterol, T0901317, or cholesterol acceptor was added to the basolateral and apical chambers. In some instances, the monolayer was pretreated with 20 μM probucol for 1 h and then efflux proceeded in the presence of the same concentration of probucol for 4 h. Medium with probucol was added to both chambers. Medium from the basolateral chamber and medium from the apical chamber were collected separately, filtered, and read in a scintillation counter. Hexane-isopropanol (3:2, v/v) was added to the apical chamber for 15 min, and then the monolayer was breached with a scalpel, permitting the solvent to drain into the basolateral chamber, followed by further incubation for 15 min. The solvent was collected, evaporated, and the remaining extracted lipids were read in a scintillation counter. Cholesterol efflux to the basolateral and apical side was expressed as the percent of radiolabel counts in the basolateral or apical chamber from the total counts in both chambers and cells. For oxLDL and acLDL feeding experiments, radiolabeled RPE bilayers were incubated with 50 μg/ml oxLDL, 50 μg/ml acLDL, or 2–5% FBS in both chambers for 28 h and then cholesterol efflux measurements were conducted as above, except media from the basolateral and apical chambers were treated with phosphotungstate to precipitate apoB-lipoprotein (see below) and then read in a scintillation counter.

oxLDL and acLDL preparation

oxLDL was prepared by incubating human LDL with CuSO4. LDL was isolated by ultracentrifugation in NaBr/KBr, dialyzed in phosphate buffer (MWCO 12,000–14,000), measured for protein content (using a BCA kit), and incubated overnight in a wide dish at 2–4 mg/ml in 40 μM CuSO4 at 37°C. oxLDL was then extensively dialyzed in TBS-EDTA [10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4)] and filter-sterilized. oxLDL was tested for the ability to inhibit ABCA1-mediated efflux in J774 cells. J774 cells were radiolabeled, exposed to 50 μg/ml oxLDL for 18 h, and then treated as in a regular cholesterol efflux assay (42).

To prepare acLDL, LDL was dialyzed in 0.15 M NaCl, measured for protein content (using a BCA kit), and added to a saturated (10 M) sodium acetate solution at a 1:1 vol ratio in an improvised water-ice bath with continuous stirring. Acetic anhydride (density 1.087 g/cm3, purity ≥97.0%; Fisher Scientific) was added to the LDL/sodium acetate mixture while it was being stirred in the water-ice bath in seven aliquots every 10 min to the final amount of 1.4 μl per milligram of LDL (e.g., a total of 14 μl of acetic anhydride in 2 μl aliquots would be added to 10 mg of LDL). After addition of the seventh aliquot, the mixture was stirred on ice for 30 min, extensively dialyzed in TBS-EDTA, and filter-sterilized.

GC-MS measurement of cell total and esterified cholesterol

phfRPE monolayers on transwell inserts were incubated with 50 μg/ml oxLDL, 50 μg/ml acLDL, or 2% FBS for 28 h and then washed with PBS twice. D7-cholesterol (5 μl of 3.3 mg/ml) was pipetted onto the monolayers as an internal standard. The inserts were then cut out with a scalpel and transferred to 1 ml hexane/isopropanol (3:2 v/v) with forceps. The inserts remained in the lipid solvent for 25 min and then were transferred to empty wells of a 24-well plate, briefly dried, and lysed in 400 μl of 0.1 N NaOH overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking. The solvent was evaporated in nitrogen, and free and total cholesterol mass were respectively determined before and after saponification and derivatization by GC-MS at the IDOM Metabolic Tracer Resource (University of Pennsylvania). Esterified cholesterol was calculated as the difference between total and free cholesterol. Cell cholesterol was normalized to cell protein.

apoB-lipoprotein precipitation

apoB-lipoprotein was precipitated by a modified phosphotungstate method (44) using a commercially available reagent (Thermo Scientific reagent 1335-250).

Preparation of POPC small unilamellar vesicles

POPC (Avanti Polar Lipids) in chloroform was dried in a stream of nitrogen onto the sides of a glass culture tube and kept in vacuum overnight. Dry POPC was rehydrated in TBS by five cycles of freeze-thaw (dry ice/ethanol, 37°C water bath) and extensive vortexing after each thaw to derive multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) at 2–5 mg/ml. POPC MLVs were then extensively sonicated in a water-bath sonicator; formation of small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) was monitored visually by the disappearance of milky MLV suspension.

Immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting

Tight junctions were visualized using a polyclonal anti-zonula occludens-1 (ZO1) antibody (ab59720; Abcam). RPE transwells were sectioned in 100 μm slices using a vibratome and stained for apoE with a polyclonal antibody (178479; CalBioChem) as previously described by Fernandez-Godino, Garland, and Pierce (45). Cell media from the basolateral and apical chambers were concentrated 10–20 times using 10 kDa NMWL, 0.5 ml centrifugal filters (EMD Millipore), and apoB was detected on Western blots using a polyclonal antibody (ab20737; Abcam). The antibody detected apoB in as little as 70 ng of LDL and was sensitive to 3× differences in apoB content between LDL samples in a dilution series. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies, NB400-105 and NB400-113 (both from Novus Biologicals), were used to detect ABCA1 and scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), respectively.

ELISA

apoB in conditioned medium was measured using a human apoB ELISA kit (ab108807; Abcam) without dilution and at a 1/5 dilution. apoA-I in conditioned medium was measured using a human apoA-I ELISA kit (DAPA10; R&D Systems) without dilution and at a 1/5 dilution.

Statistical analysis and data presentation

GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) was used to prepare graphs and perform statistical analysis. The t-test, which retains robustness when data are not normally distributed (46), was employed throughout to identify significant differences between data sets.

RESULTS

Cholesterol efflux pathways operating in ARPE-19 cells

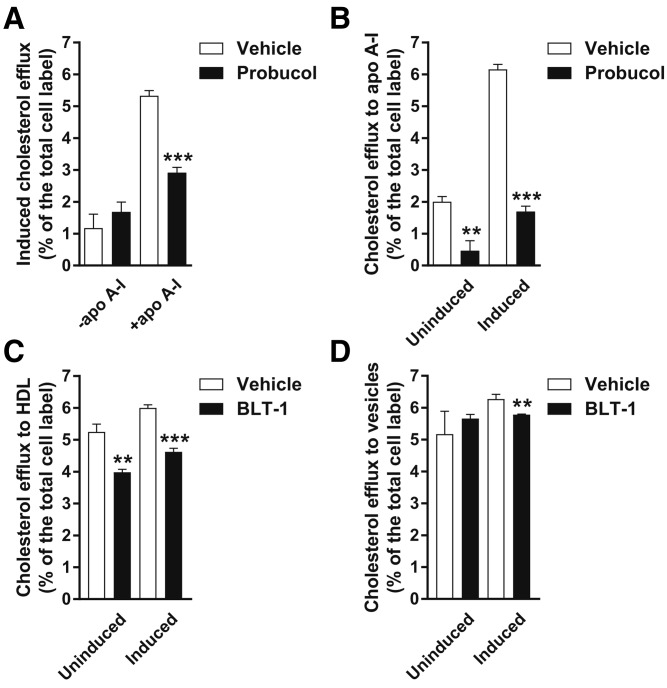

To assess cholesterol efflux pathways operating in the RPE, we first used a human immortalized RPE cell line, ARPE-19, which recapitulates many features of primary RPE cells (47). Cells can release cholesterol by forming nascent HDL particles using plasma membrane phospholipid and cholesterol and extracellular lipid-poor apoA-I or by promoting desorption-diffusion and direct transfer of plasma membrane cholesterol to extracellular acceptors, such as mature HDL or phospholipid vesicles (48). ABCA1 mediates nascent HDL formation (48). RPE cells strongly express LXRβ, a regulator of ABCA1 expression (37). Probucol inhibits ABCA1-mediated efflux to apoA-I, but has no effect on the desorption and transfer pathways of cholesterol efflux (49, 50). When apoA-I was not added to LXR agonist-treated ARPE-19 cells, cholesterol efflux was minimal and insensitive to treatment with probucol; addition of exogenous apoA-I to LXR agonist-treated cells promoted cholesterol efflux, which was sensitive to probucol inhibition (Fig. 2A). These observations suggest that LXR-agonist-treated ARPE-19 cells express functional ABCA1, but not a functionally significant amount of apoA-I or other apolipoprotein acceptor of cholesterol. To determine whether ABCA1 expression occurs in the absence of upregulation via LXRβ, ARPE-19 cells were treated with probucol, but not an LXR agonist, and then exposed to apoA-I. Probucol significantly inhibited cholesterol efflux in this case, indicating that ABCA1 is expressed in unstimulated ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 2B).

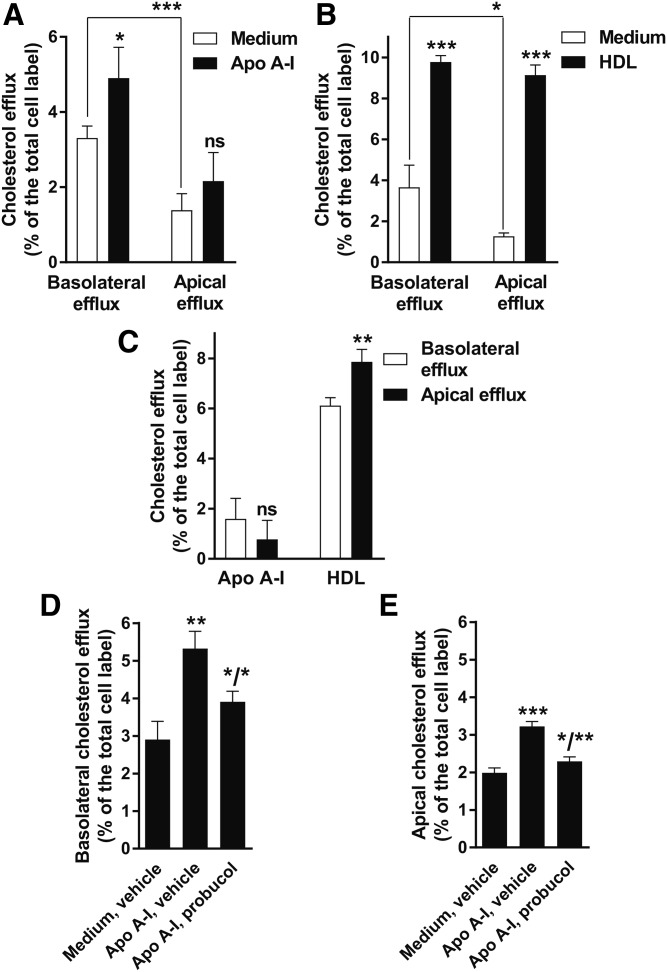

Fig. 2.

Cholesterol efflux by the ABCA1-dependent and SR-BI-dependent pathways from ARPE-19 cells. A: Cholesterol efflux from induced, i.e., LXR agonist-treated, ARPE-19 cells to medium without a cholesterol acceptor and to medium with added apoA-I. LXR agonists increase ABCA1 expression. apoA-I addition was required for robust cholesterol efflux even when ABCA1 levels were upregulated, suggesting that these cells do not express apoA-I or other cholesterol acceptors by the ABCA1-mediated pathway. A treatment with probucol, an ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux inhibitor, significantly suppressed cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. B: Cholesterol efflux to apoA-I from induced and uninduced ARPE-19 cells. A significant amount of probucol-sensitive, i.e., ABCA1-mediated, efflux took place without induction of ABCA1 expression with an LXR agonist. Treatment with an LXR agonist substantially increased probucol-sensitive efflux. C: BLT-1, a specific inhibitor of SR-BI-mediated efflux, mildly but significantly suppressed cholesterol efflux to HDL, regardless of LXR agonist treatment. D: BLT-1 did not have a substantial effect on cholesterol efflux to POPC vesicles. Mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis, t-test (**P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001).

SR-BI increases the rate of plasma membrane cholesterol desorption and diffusion to extracellular acceptors, such as HDL and phospholipid vesicles; it also binds mature HDL and mediates net transfer of plasma membrane cholesterol to this acceptor (48). BLT-1 inhibits SR-BI-mediated cholesterol efflux, but has no effect on ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux and non-SR-BI-mediated cholesterol desorption (49, 51). To assess cholesterol efflux by SR-BI-mediated desorption and direct transfer to mature HDL, ARPE-19 cells were treated with BLT-1 and exposed to mature HDL. Cholesterol efflux to mature HDL was robust and mildly, but significantly, inhibited by BLT-1, suggesting that SR-BI contributes to cell cholesterol efflux in ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 2C). To assess specifically the desorption component of SR-BI-mediated cholesterol efflux, ARPE-19 cells were treated with BLT-1 and then exposed to POPC SUVs. SR-BI does not bind neutral phospholipid, but has been shown to promote cell cholesterol efflux to POPC SUVs by increasing cholesterol desorption (52). Cholesterol efflux to POPC vesicles was not substantially inhibited by BLT-1 (Fig. 2D). This suggests that in ARPE-19 cells, SR-BI does not increase the rate of plasma membrane cholesterol desorption and only actuates direct cholesterol transfer to HDL. ARPE-19 cells overall employed the same cholesterol efflux pathways as those available to macrophages (49).

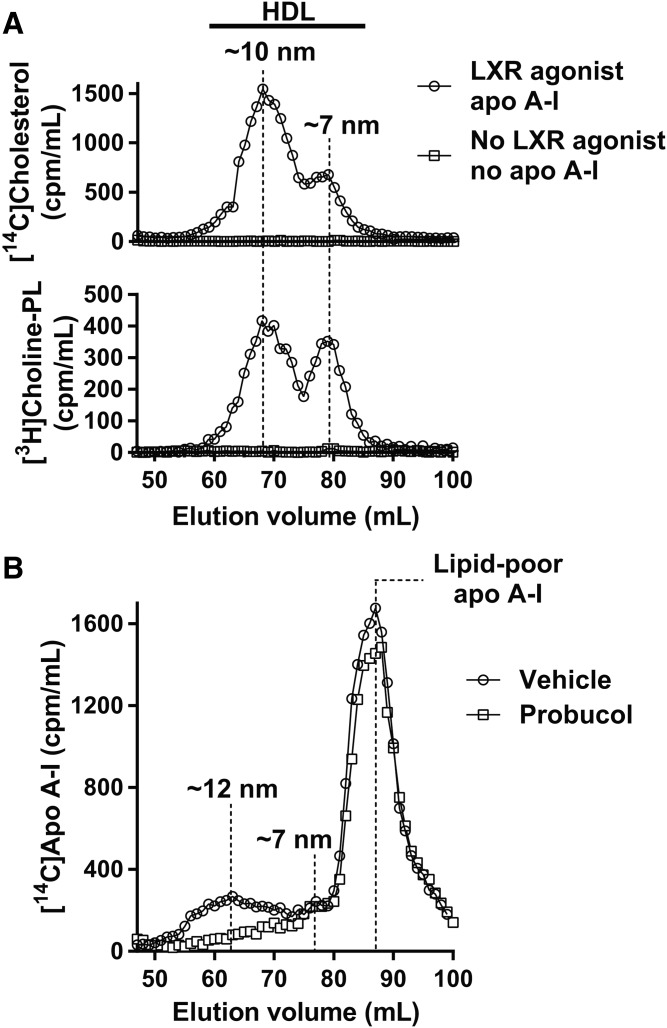

HDL particle species formed by ARPE-19 cells

To characterize the assortment of nascent HDL particles formed by ARPE-19 cells, HDL was produced in large-scale cultures of ARPE-19 cells labeled with [14C]cholesterol and [3H]choline-phospholipid and resolved by size using a gel filtration column. Without treatment with an LXR agonist and addition of apoA-I, the cells did not produce any detectable HDL particles (i.e., no [14C]cholesterol and [3H]choline-phospholipid peaks in the HDL size range; Fig. 3A). With an LXR agonist treatment and addition of a saturating amount of exogenous apoA-I, ARPE-19 cells formed two species of the HDL particle. The presence of two HDL species was evident from two [14C]cholesterol and two [3H]choline-phospholipid peaks located in the HDL size range. The faster-migrating [14C]cholesterol and [3H]choline-phospholipid peaks overlapped and were ∼10 nm in hydrodynamic diameter at the peak center (larger particles migrate faster in gel filtration columns). The slower-migrating [14C]cholesterol and [3H]choline-phospholipid peaks also overlapped and were ∼7 nm in hydrodynamic diameter at the peak center. The larger-sized particles dominated over the smaller-sized particles in the amount of cholesterol and choline-phospholipid. The overlap between the [14C]cholesterol and [3H]choline-phospholipid peaks indicated that both particle species consisted of cholesterol and choline-phospholipid. The nascent HDL generation experiment using [14C]cholesterol- and [3H]choline-phospholipid-labeled ARPE-19 cells was repeated, and the results were the same (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Formation of nascent HDL particles by ARPE-19 cells. A: Gel filtration elution profiles of HDL particles formed after incubation of radiolabeled ARPE-19 cells with exogenous apoA-I for 8 h. Approximate hydrodynamic diameters of the two major HDL species are shown. B: Gel filtration elution profiles of HDL particles formed after incubation of the cells with exogenous radiolabeled apoA-I for 18 h. Treatment with probucol suppressed HDL formation.

To demonstrate that apoA-I was also part of the particles formed by ARPE-19 cells, large-scale cultures of ARPE-19 cells were grown in the presence of an LXR agonist, treated with probucol or vehicle, and then exposed to a saturating amount of [14C]apoA-I. While in the first experiment nascent HDL formation proceeded for 8 h, in this case nascent HDL formation continued for 18 h. This change was introduced to generate more HDL. After an 18 h incubation with the cells, [14C]apoA-I segregated into three peaks on the gel filtration column (Fig. 3B): the two faster migrating peaks (∼12 and ∼7 nm in hydrodynamic diameter) were in the HDL size range, while the slowest-migrating peak (∼5 nm in hydrodynamic diameter) corresponded to lipid-poor apoA-I (42). The large-sized HDL peak dominated over the smaller-sized HDL peak in the amount of apoA-I. Probucol dramatically inhibited formation of the larger-sized HDL species, but had no effect on the formation of the smaller-sized HDL species (Fig. 3B). This is consistent with our previous observations in other cell types that probucol suppresses formation of the larger-sized HDL species and leaves unaffected or increases formation of the smaller-sized species (50). When radiolabeled cholesterol was used in the 18 h HDL formation assay, the results were the same as with radiolabeled apoA-I: two HDL particle species, ∼12 and ∼7 nm in hydrodynamic diameter, could be detected (data not shown). We (42, 50) and others (53) have previously shown that macrophages, hepatocytes, and other cell types that express either endogenous or exogenous ABCA1 form nascent HDL in two species that differ in size: the hydrodynamic diameter of the larger species at the peak center varies from 10 to >13 nm, depending on cell type, cholesterol loading, cell density, and other factors, while the hydrodynamic diameter of the smaller species at the peak center is confined to a more narrow range of 7–8 nm; the larger-sized species normally dominates over the smaller-sized species in the amount of apoA-I, cholesterol, and choline-phospholipid. Nascent HDL formation by ARPE-19 cells closely follows this general paradigm.

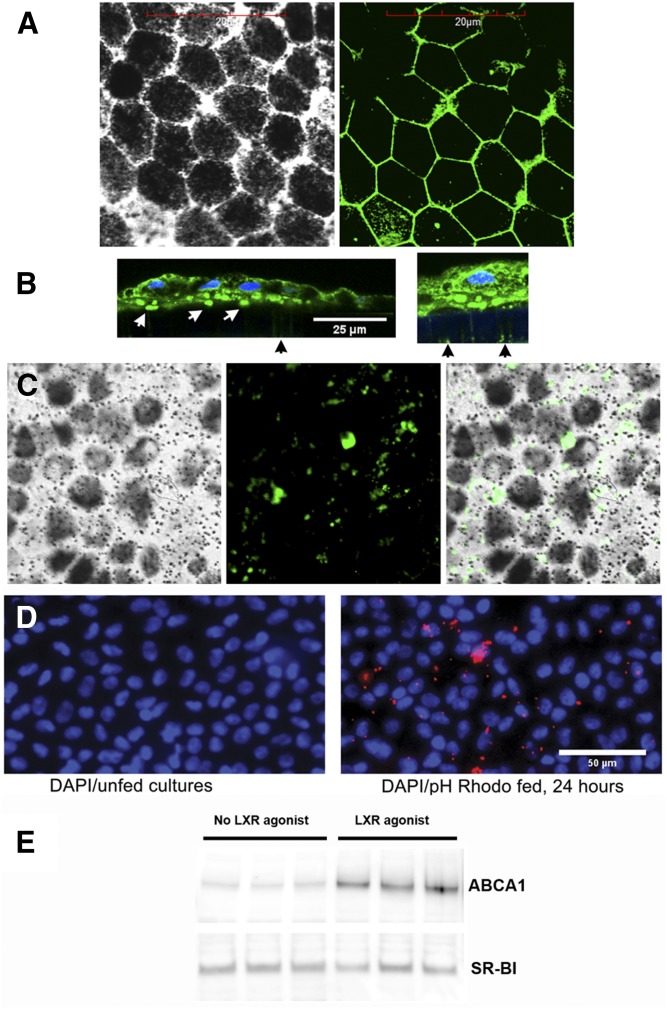

Establishment of the phfRPE monolayer model

Highly-polarized monolayers composed of phfRPE cells have been shown to deposit apoE-containing membranous material, hydroxyapatite, and other components found in soft drusen (54, 55). We have established a polarized phfRPE culture model to further characterize lipoprotein production in the RPE (Fig. 1B). After a 5 week growth on transwell inserts, phfRPE monolayers consisted of hexagonal cells rich in melanosomes (Fig. 4A, C). Immunostaining with an antibody against ZO1, a tight junction protein, revealed the presence of abundant tight junctions between RPE cells (Fig. 4A). TEER of the monolayers was >450 Ω·cm2. The monolayers secreted apoE to the basolateral and apical sides, but apoA-I could not be detected in conditioned medium on either side with either Western immunoblotting or a sensitive ELISA (data not shown). The phfRPE monolayers preserved hexagonal cell morphology, rich melanosome content, and high TEER when maintained for five additional months; ZO1 immunostaining detected numerous tight junctions in 6-month-old cultures (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of phfRPE cultures. A: Fluorescent immunohistochemistry with a ZO1 antibody showed the presence of abundant tight junctions between hexagonally shaped cells in phfRPE monolayers (left panel, light microscopy; right panel, fluorescence microscopy). B: apoE-rich sub-RPE deposits in a phfRPE culture. Fluorescent immunohistochemistry of sections across the phfRPE monolayer and underlying porous support with an apoE antibody. Numerous apoE-containing deposits (white arrows in the left panel) were visible at the basolateral side of the phfRPE, between phfRPE cells and the insert support. The support was not fluorescent, except for faint fluorescence inside pores (black arrow). The right panel shows a portion of the image in the left panel at a longer exposure. With longer exposures, apoE deposits could be seen inside pores. C: En face fluorescent immunohistochemistry of the phfRPE with an apoE antibody. Melanosomes could be seen as dark spots in light microscopy (left panel). Fluorescent microscopy showed variously sized focal apoE deposits (middle panel and light and fluorescent microscopy merged image in the right panel). D: Phagocytosis of fluorescently labeled E. coli particles by phfRPE cells. E: Expression of ABCA1 and SR-BI before and after treatment with an LXR agonist by phfRPE monolayers that had been in culture for 2 months.

apoE immunohistochemistry of sections across the phfRPE monolayer and transwell support showed abundant apoE-containing deposits located at the basolateral side of the phfRPE, between phfRPE cells and the support (Fig. 4B, left panel). apoE-containing material could be detected in the pores of the support with longer exposure times (Fig. 4B, right panel). En face immunofluorescence revealed that apoE-containing deposits were focal and variable in size (Fig. 4C). The apical membrane of the phfRPE stained for apoE, but apoE-containing deposits were not observed on the apical surface of phfRPE cells (Fig. 4B). phfRPE cell morphology and deposition of extracellular material in our RPE model were similar to those previously reported for the same type of RPE monolayer by other groups (54, 55).

phfRPE cells avidly engulfed fluorescently labeled E. coli particles (Fig. 4D). Phagocytosis is a vital function of the RPE. The ability of phfRPE cells to phagocytose in vitro indicates a healthy and high-polarized state of these cells (41).

phfRPE monolayers that had been in culture for 2 months were evaluated for expression of ABCA1 and SR-BI before and after treatment with an LXR agonist. ABCA1 was expressed in phfRPE monolayers not stimulated with an LXR agonist; an LXR agonist treatment significantly elevated ABCA1 expression (Fig. 4E). Expression of SR-BI in phfRPE monolayers was strong and independent of LXR agonist treatment (Fig. 4E). These findings show that ABCA1 expression in the RPE is upregulated by LXR agonists, just as in many other cell types (49, 50).

Cholesterol efflux to apoA-I and HDL in the phfRPE model in regular growth conditions

In vivo, the RPE is exposed to apoA-I, apoE, and HDL from the systemic circulation at the basolateral side and to apoA-I, apoE, and likely HDL from the PSL at the apical side (Fig. 1A; Refs. 4, 31). Thus, in the RPE, cholesterol efflux could occur at both sides simultaneously. We first set out to characterize cholesterol efflux to apoA-I and HDL at the apical and basolateral sides of highly-polarized phfRPE monolayers under the regular optimal growth conditions. phfRPE monolayers were labeled with [3H]cholesterol, treated with an LXR agonist, and exposed to medium without cholesterol acceptors, 10 μg/ml apoA-I or 100 μg/ml HDL, for 4 h. The same amount of medium with the same concentrations of the reagents was added to the basolateral and to the apical chamber of the well (Fig. 1B). Cholesterol efflux to medium without cholesterol acceptors was significantly higher at the basolateral than at the apical side (Fig. 5A, B). Addition of apoA-I effected a small, but significant, increase in cholesterol efflux at the basolateral side and a trend toward higher efflux at the apical side (Fig. 5A). The percent efflux to medium was subtracted from the percent efflux to medium with apoA-I separately on each side; the resultant adjusted efflux values to apoA-I were small and trended (not significantly) to be higher at the basolateral side than at the apical side (Fig. 5C). Addition of HDL significantly increased cholesterol efflux at both sides (Fig. 5B). The percent efflux to medium was subtracted from the percent efflux to medium with HDL separately on each side; the resultant adjusted efflux values to HDL were significantly higher (48 ± 36%; mean ± SD, n = 6) at the apical side than at the basolateral side (Fig. 5C). Probucol significantly inhibited efflux to apoA-I at the basolateral side and completely suppressed efflux to apoA-I at the apical side (Fig. 5D, E). These results show that, in the regular low-lipid conditions, efflux by the ABCA1-dependent pathway to apoA-I from the RPE is weak and hardly polarized, while efflux by diffusion and transfer to HDL is more robust and moderately directional, with a preference to the apical side.

Fig. 5.

Cholesterol efflux in the phfRPE model in regular low-lipid growth conditions. A: ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to apoA-I. phfRPE monolayers were labeled with radiocholesterol, pretreated with an LXR agonist, and exposed to 10 μg/ml apoA-I for 4 h. Radiocholesterol, LXR agonist, and apoA-I were present at the same concentration in both chambers of the well. Medium was collected and read separately from the basolateral and apical chambers. B: Cholesterol efflux to HDL. phfRPE monolayers were treated the same as in A, except 100 μg/ml HDL were added. C: Comparison of cholesterol efflux to the basolateral versus apical side. The data shown in panels A and B were processed as the following: the average percent efflux to medium (white bars in A and B) was subtracted from the individual percent efflux values to medium with apoA-I or HDL (black bars in A and B) separately on each side. The resultant adjusted efflux values were plotted side-by-side basolateral versus apical efflux by acceptor. D, E: Suppression of cholesterol efflux to apoA-I with probucol. In a different set of experiments, phfRPE monolayers were treated as in A, except probucol was added to the monolayers 1–2 h before addition of apoA-I, and cholesterol efflux to apoA-I occurred in the presence of probucol. The increase in efflux to apoA-I at the apical side was similar in magnitude to the increase in A, but also reached statistical significance because of reduced variability in this set of cells. Mean ± SD (n = 3–6). Statistical analysis, t-test (ns, not significant; *P < 0.1; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Elevated cholesterol levels in phfRPE monolayers fed oxLDL or acLDL

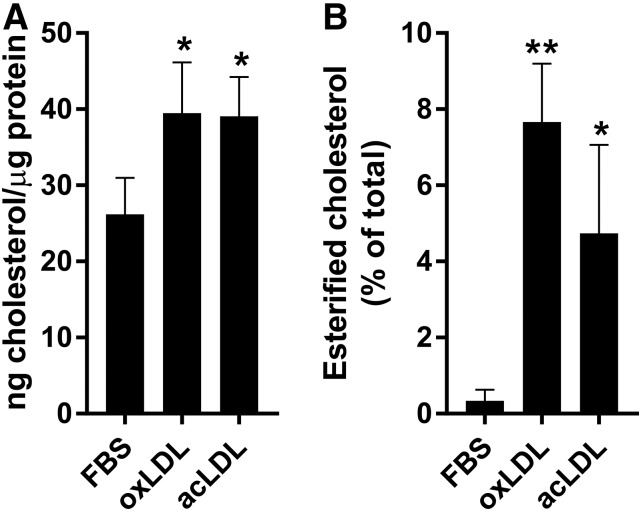

To determine the effect of exposure to oxLDL or acLDL on the intracellular cholesterol levels in the RPE, phfRPE monolayers were incubated in regular medium, 50 μg/ml oxLDL, or 50 μg/ml acLDL for 28 h. oxLDL was prepared by copper-mediated oxidation and was tested using J774 cells. Our preparation of oxLDL inhibited ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux in J774 cells by ∼94%, indicating that LDL was oxidized substantially (56). phfRPE inserts were then excised and extracted with a lipid solvent system; the cells on the inserts were lysed and measured for protein content, while the lipid extracts were analyzed for free and esterified cholesterol. Intracellular cholesterol concentration was expressed as nanograms of cholesterol per microgram of cell protein (Fig. 6A). Incubation with oxLDL and acLDL significantly increased total intracellular cholesterol by similar amounts: 51 ± 26% and 49 ± 20% (mean ± SD, n = 3; Fig. 6A), respectively. While phfRPE cells grown in regular medium had virtually no esterified cholesterol (i.e., <1%), after feeding with oxLDL or acLDL, esterified cholesterol comprised 4.7 ± 2.3% and 7.6 ± 1.5% (mean ± SD, n = 3; Fig. 6B), respectively, of the total cell cholesterol. Furthermore, esterified cholesterol represented 17.4 ± 9.0% and 22.8 ± 2.1% (mean ± SD, n = 3) of the cholesterol acquired with oxLDL or acLDL, respectively. These results show that oxLDL and acLDL are similarly effective at raising intracellular cholesterol levels in the RPE.

Fig. 6.

Intracellular total and esterified cholesterol levels after feeding phfRPE monolayers with oxLDL or acLDL. Polarized phfRPE monolayers were incubated in regular medium, oxLDL, or acLDL, followed by measuring monolayer cholesterol and protein content. A: Total intracellular cholesterol levels. B: Intracellular esterified cholesterol as the percent of total cell cholesterol. Mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis, t-test (*P < 0.1; **P < 0.01).

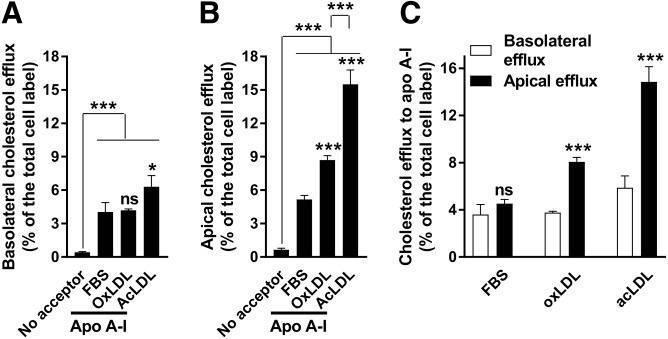

Preferential ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to the apical side in phfRPE monolayers after lipid loading with oxLDL or acLDL

We next determined how high levels of intracellular lipid and oxidized lipid affect ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux in the phfRPE model. phfRPE monolayers were maintained in 5% FBS for 2 weeks to acclimate cell metabolism to a higher level of lipid in the medium, then labeled with radiocholesterol overnight, exposed to 5% FBS, 50 μg/ml oxLDL, or 50 μg/ml acLDL for 28 h, and treated with an LXR agonist for 18 h. phfRPE monolayers kept in FBS were exposed to medium or medium with a saturating concentration of apoA-I for 4 h; monolayers fed oxLDL or acLDL were exposed to apoA-I for 4 h. Basolateral and apical media were collected separately and treated with phosphotungstate to remove phfRPE-secreted apoB-lipoprotein (44). Phosphotungstate treatment was introduced because lipid loading with oxLDL or acLDL could differentially affect apoB-lipoprotein secretion and skew ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux values. Cholesterol efflux to medium without cholesterol acceptors from phfRPE monolayers kept in FBS was low (0.4–0.8%) at the basolateral and apical sides; addition of apoA-I significantly increased cholesterol efflux at both sides (Fig. 7A, B). At the basolateral side, cholesterol efflux to apoA-I from oxLDL- and acLDL-fed monolayers was the same and moderately higher, respectively, in comparison with efflux to apoA-I from FBS-kept monolayers (Fig. 7A). However, at the apical side, cholesterol efflux to apoA-I was much stronger from oxLDL- and acLDL-fed monolayers than from FBS-kept monolayers, and cholesterol efflux to apoA-I from acLDL-fed monolayers was much stronger than from oxLDL-fed monolayers (Fig. 7B). The average percent efflux to medium without apoA-I was subtracted from individual values of the percent efflux to medium with apoA-I at both sides; the resultant adjusted cholesterol efflux values to apoA-I from FBS-kept phfRPE monolayers did not differ significantly between the basolateral and apical sides (Fig. 7C). Cholesterol efflux to apoA-I from oxLDL- and acLDL-fed phfRPE monolayers was 115 ± 10% and 153 ± 22% (mean ± SD, n = 3), respectively, stronger at the apical side than at the basolateral side (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that lipid loading of phfRPE cells with oxLDL or acLDL increases cholesterol efflux to apoA-I preferentially at the apical side and that phfRPE cells are less efficient at release of cholesterol taken-up with oxLDL than with acLDL.

Fig. 7.

Increased ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux at the apical side from phfRPE monolayers fed oxLDL or acLDL. A: Cholesterol efflux from phfRPE monolayers at the basolateral side. phfRPE monolayers were labeled with radiocholesterol, incubated with 5% FBS, 50 μg/ml oxLDL, or 50 μg/ml acLDL, treated with an LXR agonist, and exposed to medium or medium with apoA-I. Efflux medium was treated with phosphotungstate to remove apoB-lipoprotein, because oxLDL and acLDL could affect apoB-lipoprotein secretion and skew apoA-I cholesterol efflux values. In comparison with efflux to apoA-I from phfRPE monolayers kept in FBS, efflux to apoA-I from oxLDL- and acLDL-fed monolayers was the same and moderately, but significantly, elevated, respectively. B: Cholesterol efflux from phfRPE monolayers at the apical side. These are the same monolayers as in panel A, only efflux at the apical side is shown. In comparison to efflux to apoA-I from phfRPE monolayers kept in FBS, efflux to apoA-I from oxLDL- and acLDL-fed monolayers was significantly stronger; furthermore, efflux from phfRPE monolayers fed acLDL was significantly stronger than efflux from monolayers fed oxLDL. C: Comparison of cholesterol efflux to apoA-I between the basolateral and apical side by the feeding status. The average percent efflux to medium was subtracted from individual values of the percent efflux to apoA-I; the resultant adjusted values were plotted basolateral versus apical efflux. Mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis, t-test (ns, not significant; *P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

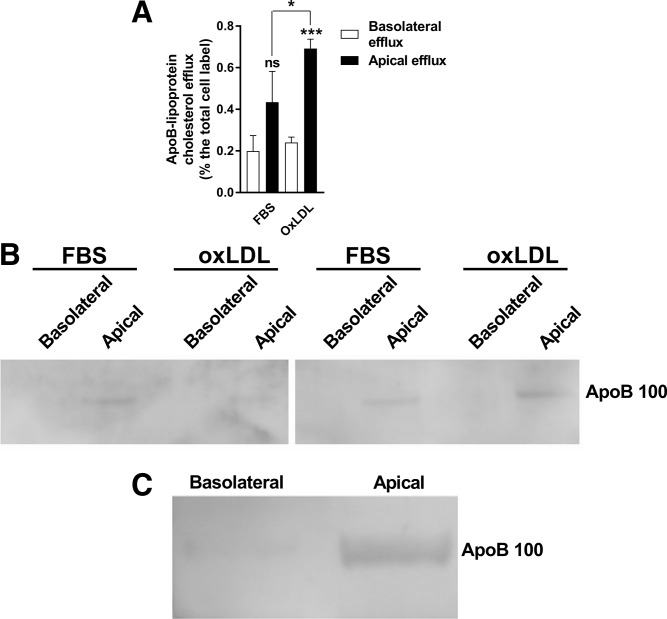

Preferential secretion of apoB-lipoprotein to the apical side

Phosphotungstate-precipitated radiocholesterol counts in the high-lipid high-oxidized lipid experiments were higher in the apical medium than in the basolateral medium regardless of whether the phfRPE was exposed to FBS, oxLDL, or acLDL (data not shown). This suggested that apoB-lipoprotein was preferentially secreted to the apical side. To further explore this possibility, radiocholesterol-labeled phfRPE monolayers were incubated in 2.5% FBS or 50 μg/ml oxLDL for 28 h and then allowed to secrete lipoprotein in lipid-free medium for 8 h in the absence of any cholesterol acceptors. Radiocholesterol counts in an aliquot of efflux medium were read, then the aliquot was treated with phosphotungstate to precipitate apoB-lipoproteins, and radiocholesterol counts in the aliquot were read again; the difference in counts before and after phosphotungstate treatment was attributed to apoB-lipoprotein. The remaining efflux medium was concentrated and analyzed by apoB immunoblotting. The FBS- and oxLDL-fed phfRPE monolayers tended to secrete more and secreted significantly more, respectively, of radiocholesterol in apoB-lipoprotein to the apical side than to the basolateral side (Fig. 8A). Immunoblotting analysis confirmed the presence of apoB100 in the apical medium of FBS- and oxLDL-fed phfRPE monolayers, but no apoB could be detected in the basolateral medium from the same monolayers (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Preferential secretion of apoB-lipoprotein to the apical side of phfRPE monolayers. A: apoB-lipoprotein-associated (i.e., phosphotungstate-precipitated) radiocholesterol counts in the basolateral and apical medium of phfRPE monolayers fed FBS or oxLDL. Mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis, t-test (ns, not significant; *P < 0.1; ***P < 0.001). B: apoB100 in the basolateral and apical media of phfRPE monolayers fed FBS or oxLDL. Results from two independent experiments. C: apoB100 secretion to the basolateral and apical side by a phfRPE monolayer maintained in FBS-free conditions for 72 h.

To investigate apoB-lipoprotein secretion over long time periods, phfRPE monolayers maintained in 2% FBS medium were transferred to lipid-free medium for 72 h. Conditioned media from both sides were concentrated and immunoblotted with an apoB antibody. apoB100 could be detected in the media from both sides; however, the signal in the apical medium was much stronger than in the basolateral medium (Fig. 8C). A different set of phfRPE monolayers were kept in FBS-free medium for 48 h, and then apoB levels were measured in the conditioned media using a sensitive ELISA. No apoB signal could be detected in the basolateral medium, the apical medium contained 20.1 ± 0.9 ng apoB per insert (mean ± SD, n = 3). These observations suggest that the phfRPE secretes apoB-lipoprotein preferentially to the apical side under normal growth conditions and after exposure to high levels of oxLDL.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we addressed cholesterol metabolism in the RPE using an immortalized RPE cell line, ARPE-19, and highly-polarized phfRPE monolayers. ARPE-19 cells produced lipoprotein particles that contained cholesterol, phospholipid, and apoA-I, the same components as nascent HDL, and were the same in hydrodynamic diameter and particle assortment (i.e., two types of the particle were formed) as nascent HDL produced by other cell types; production of these particles by ARPE-19 cells was sensitive to an ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux inhibitor, probucol (42, 50, 53). Based on this evidence, lipoprotein produced by ARPE-19 cells is genuine nascent HDL. In the optimal growth conditions of low-lipid, phfRPE monolayers relied on diffusion and transfer to HDL as the main means of cell cholesterol release. ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to apoA-I was weak. Cholesterol efflux to HDL was moderately polarized to the apical side, while cholesterol efflux to apoA-I was essentially equivalent at the two sides. After intracellular cholesterol levels were elevated by feeding phfRPE cells with oxLDL or acLDL, cholesterol efflux to apoA-I rose by more than two times at the apical side, but remained largely the same at the basolateral side. apoB-lipoprotein secretion occurred preferentially to the apical side in low-lipid conditions and after phfRPE feeding with oxLDL. These results reveal a complex dynamic of cholesterol release by the RPE in response to different lipid availabilities.

Cholesterol efflux in the RPE has many similarities to the corresponding process in macrophages. In cholesterol-normal macrophages, desorption-diffusion is the dominant pathway of cholesterol release, while ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux to apoA-I contributes little to the total cell cholesterol removal (57). Efflux to apoA-I becomes a dominant means of cholesterol elimination in macrophages loaded with cholesterol by feeding with acLDL (57). phfRPE cells use the desorption-diffusion and ABCA1-mediated pathways of cholesterol efflux essentially in like manner, except ABCA1-mediated efflux in these cells rises only at the apical side. Feeding macrophages with oxLDL fails to increase or even suppresses ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux, depending on macrophage type (56, 58). We used inhibition of ABCA1-mediated efflux to apoA-I in J774 cells as a test of the potency of our oxLDL preparations. RPE cells preserve viability at greater concentrations of oxLDL than macrophages (35, 56, 58–60). oxLDL- and acLDL-fed phfRPE cells accumulated the same amount of cholesterol. phfRPE cells fed oxLDL still exhibited an increase in cholesterol efflux to apoA-I, although this increase was smaller than in the phfRPE cells fed acLDL. Greater resistance to oxLDL is likely an evolutionary adaptation on the part of the RPE to oxidizing conditions in the retina.

As a rule, the basolateral and apical membranes of epithelial cells differ in protein and phospholipid composition, cholesterol content, physical properties, and function (61). Preferential efflux of cholesterol by the ABCA1-mediated pathway and other pathways to either the basolateral or apical side has been described in several types of epithelium (e.g., Refs. 38–40). In this regard, the RPE should not be an exception. Directional protein secretion by RPE cells has been well-established (62). We here document directional desorption-diffusion and ABCA1-mediated efflux in the RPE layer. The directionality of cholesterol efflux can arise owing to preferential localization of the efflux mediator, differences in membrane lipid composition and cholesterol content, or some combination of the two (61). Presently, it is not clear which of these factors are at work in the RPE. Several studies have reported expression of SR-BI and ABCA1 in the RPE and described cholesterol efflux from RPE cells (21, 31, 37, 63–66). A recent investigation documented ABCA1 localization to the basolateral and apical membranes and demonstrated ABCA1-mediated efflux at both sides of phfRPE monolayers, but did not directly compare basolateral and apical efflux (66). Ananth et al. (64) showed a preferential localization of ABCA1 to the apical membrane in mouse RPE using immunohistochemistry. Further research will determine how the preferential efflux to the apical side by the ABCA1-mediated pathway arises in response to oxLDL and acLDL uptake.

Several tissues outside of the digestive system secrete apoB-lipoprotein. In cardiomyocytes and tubular epithelial cells of the kidney, apoB-lipoprotein secretion regulates intracellular levels of triglyceride (67–69). It has been suggested that apoB-lipoprotein secreted by the RPE transports DHA to photoreceptor inner segments, which express the LDL receptor (37, 70). DHA comprises 15% of the fatty acid in the human retina and is critical to vision (12, 71). DHA is especially abundant in the outer segments, which are continuously shed by photoreceptors and are engulfed by RPE cells (71). Tracer studies have shown that DHA from the systemic circulation and shed outer segments transiently resides in the RPE and is then delivered from the RPE to photoreceptors (71). RPE cells contain little DHA in the plasma membrane and are thus unlikely to release it in sufficient amounts by the ABCA1-mediated pathway (12). Preferential apoB secretion to the apical, i.e., photoreceptor, side is consistent with the hypothesis that apoB-lipoprotein is the vehicle of DHA transport in the PSL.

The RPE is exposed to lipoprotein from the systemic circulation at the basolateral side and to lipoprotein from the PSL at the apical side (31, 33). Owing to oxidative conditions in the retina, LDL undergoes oxidation by the free radical-mediated mechanism, and local concentrations of lipid oxidation products, such as 7-ketocholesterol, in the vicinity of the RPE can rise to levels that would be lethal in RPE cell culture (72, 73). The RPE expresses cluster of differentiation 36, a scavenger receptor for modified LDL, including oxLDL and acLDL, on both the basolateral side and the apical side and can avidly take-up modified LDL (33, 74, 75). RPE cells express enzymes and transporters required for cholesterol esterification, catabolism to hydroxycholesterol, release in apoB-lipoprotein and HDL, and enhanced diffusion to extracellular acceptors (21, 37, 76). It is important to understand cholesterol metabolism in the RPE, especially its release in apoB-lipoprotein and HDL. RPE-synthesized lipoprotein may contribute cholesterol to cholesterol-rich soft drusen and SDDs, which form, respectively, in the Bruch’s membrane at the basolateral side and in the PSL at the apical side of the RPE, which are key pathogenic factors in AMD (2). The RPE could be a major source of lipid in one or both deposits. Preferential ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux, i.e., nascent HDL synthesis, to the apical side in lipid-loaded phfRPE monolayers suggests that RPE-generated HDL could, under certain conditions, contribute lipid to SDDs. However, it is plausible that, in the absence of extracellular cholesterol acceptors at the apical side, cholesterol diffuses to the basolateral side and is released by the ABCA1-mediated pathway into the Bruch’s membrane, contributing lipid to soft drusen. Lipid conditions at the basolateral side of the RPE can differ significantly from the lipid conditions at the apical side. Furthermore, there could be numerous combinations of lipid conditions at both sides, e.g., high concentrations of cholesterol acceptors at both sides or high concentrations of cholesterol acceptors on the basolateral side, but not on the apical side, or vice versa. The present work demonstrates a great utility of phfRPE monolayers as a study system for lipid metabolism in the chorioretina and only begins investigating the scope of lipid conditions to which the RPE could be exposed in vivo. Our present goal is to find lipid conditions at the basolateral and apical side that bring about deposition of material bearing all the key hallmarks of soft drusen and SDDs, i.e., apoE, cholesteryl ester, and free cholesterol for soft drusen and apoE and free cholesterol for SDDs.

Human genetic studies and pathologic evidence support an etiologic role for HDL, but not apoB-lipoprotein, in AMD. Variants at the ABCA1 locus that reduce plasma HDL-C levels and hence likely impair ABCA1 activity in all ABCA1-expressing tissues, including the RPE, are protective for AMD (23, 24). When ABCA1 is less active, RPE cells will release less HDL and may instead catabolize cholesterol to hydroxycholesterol (21). This would reduce HDL particle content in the PSL and Bruch’s membrane and slow down soft drusen and SDD accretion. Variants at the apoB locus are associated with LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, but not with AMD (22, 77). apoB-lipoprotein secreted by nondigestive tissues contains triglyceride as a major component, while soft drusen and SDDs are completely devoid of triglyceride (21, 68, 69). apoE is found in nearly all soft drusen as well as in SDDs, while apoB is present only in a fraction of soft drusen (4, 14). AMD may be a disease in which HDL, but not LDL, plays a pathogenic role.

The present study has several limitations. An immortalized cell line, ARPE-19, was used to generate nascent HDL for analysis by gel filtration because it is not feasible to grow large-scale cultures of phfRPE cells for production of nascent HDL in sufficient amounts. Concentrations of oxLDL, acLDL, apoA-I, and HDL were the same at the basolateral and apical sides of phfRPE monolayers; the RPE is likely exposed to different concentrations of oxLDL and cholesterol acceptors at the two sides in vivo. Human genetic studies suggest that high levels of ABCA1 expression are pathogenic in AMD (22, 23); phfRPE monolayers were treated with an LXR agonist to upregulate ABCA1 expression and address cholesterol metabolism when ABCA1 was expressed strongly; cholesterol metabolism in phfRPE monolayers at low ABCA1 expression levels remains to be investigated. This study used pharmacologic inhibitors of ABCA1- and SR-BI-mediated efflux. We and others have shown that probucol and BLT-1 specifically inhibit ABCA1- and SR-BI-mediated efflux, respectively, and do not affect other cholesterol efflux pathways (49–51).

In summary, cholesterol metabolism in the RPE is similar to cholesterol metabolism in macrophages. Evidence from ARPE-19 cells suggests that the RPE forms nascent HDL particles that are similar in physicochemical properties to nascent HDL formed by macrophages and other cell types. Reminiscent of macrophages, in low-lipid growth conditions, phfRPE monolayers release cholesterol primarily by desorption-diffusion and transfer to extracellular acceptors, such as mature HDL, with a moderate preference to the apical side, while ABCA1-mediated efflux of apoA-I is weak and equivalent between the two sides. Feeding phfRPE cells with oxLDL or acLDL significantly increases total and esterified intracellular cholesterol levels and dramatically raises ABCA1-mediated efflux at the apical side, while leaving ABCA1-mediated efflux at the basolateral side largely unaffected. apoB-lipoprotein secretion is directed preferentially to the apical side in low-lipid conditions and after oxLDL feeding. These results suggest that modified LDL and nascent HDL generated by the ABCA1-mediated pathway may contribute lipid to the formation of SDDs, which are located on the apical side of the RPE, and provide evidence against involvement of apoB-lipoprotein in the formation of soft drusen, which are located at the basolateral side of the RPE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kevin Trindade for performing ELISA assays, Donna Conlon for advice regarding apoB immunoblotting, Nicholas Lyssenko III for assistance with Western immunoblotting and manuscript proofreading, Fiona La for assistance with cell culture, Dr. Jeffrey Billheimer for helpful comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Gui-shuang Ying for a consultation on statistics. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Sheldon Miller and Dr. Arvydas Maminishkis from National Eye Institute/National Institutes of Health for their inputs in establishing phfRPE cultures.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- acLDL

- acetylated LDL

- AMD

- age-related macular degeneration

- HDL-C

- HDL cholesterol

- MLV

- multilamellar vesicle

- oxLDL

- oxidized LDL

- phfRPE

- primary human fetal retinal pigment epithelium

- PSL

- photoreceptor segment layer

- RPE

- retinal pigment epithelium

- SDD

- subretinal drusenoid deposit

- SR-BI

- scavenger receptor class B type I

- SUV

- small unilamellar vesicle

- TEER

- transepithelial electrical resistance

- ZO1

- zonula occludens-1

This work was supported by American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 14SDG20230024 (N.N.L.), National Eye Institute Grant 1R21EY028273-01A1 (V.R.M.C.), National Eye Institute Vision Core Grant P30 EY01583-26 (V.R.M.C.), a Genentech Age-related Macular Degeneration Fellowship (V.R.M.C.), BrightFocus Foundation Grant M2013122 (V.R.M.C.), Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant Funds to Scheie Eye Institute, the F. M. Kirby Foundation (V.R.M.C.), and the Paul MacKall and Evanina Bell MacKall Trust (V.R.M.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bird A. C. 2017. Pathogenetic mechanisms in age-related macular degeneration. In Ryan’s Retina. A. P. Schachat, S. R. Sadda, D. R. Hinton, et al., editors. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam. 1285–1292. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenick A. S., Bressler S. B., and Bressler N. M.. 2017. Age-related macular degeneration: non-neovascular early AMD, intermediate AMD, and geographic atrophy. In Ryan’s Retina. A. P. Schachat, S. R. Sadda, D. R. Hinton, et al., editors. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam. 1293–1344. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong P. T. 2006. Age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 355: 1474–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curcio C. A., and Johnson M.. 2017. Structure, function, and pathology of Bruch’s membrane. In Ryan’s Retina. A. P. Schachat, S. R. Sadda, D. R. Hinton, et al., editors. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam. 522–543. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saade C., and Smith R. T.. 2014. Reticular macular lesions: a review of the phenotypic hallmarks and their clinical significance. Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 42: 865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spaide R. F., and Curcio C. A.. 2010. Drusen characterization with multimodal imaging. Retina. 30: 1441–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarks J. P., Sarks S. H., and Killingsworth M. C.. 1994. Evolution of soft drusen in age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond.). 8: 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curcio C. A., Presley J. B., Millican C. L., and Medeiros N. E.. 2005. Basal deposits and drusen in eyes with age-related maculopathy: evidence for solid lipid particles. Exp. Eye Res. 80: 761–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curcio C. A., Millican C. L., Bailey T., and Kruth H. S.. 2001. Accumulation of cholesterol with age in human Bruch’s membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42: 265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li C. M., Chung B. H., Presley J. B., Malek G., Zhang X., Dashti N., Li L., Chen J., Bradley K., Kruth H. S., et al. 2005. Lipoprotein-like particles and cholesteryl esters in human Bruch’s membrane: initial characterization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46: 2576–2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curcio C. A., Presley J. B., Malek G., Medeiros N. E., Avery D. V., and Kruth H. S.. 2005. Esterified and unesterified cholesterol in drusen and basal deposits of eyes with age-related maculopathy. Exp. Eye Res. 81: 731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bretillon L., Thuret G., Grégoire S., Acar N., Joffre C., Bron A. M., Gain P., and Creuzot-Garcher C. P.. 2008. Lipid and fatty acid profile of the retina, retinal pigment epithelium/choroid, and the lacrimal gland, and associations with adipose tissue fatty acids in human subjects. Exp. Eye Res. 87: 521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L., Li C. M., Rudolf M., Belyaeva O. V., Chung B. H., Messinger J. D., Kedishvili N. Y., and Curcio C. A.. 2009. Lipoprotein particles of intraocular origin in human Bruch membrane: an unusual lipid profile. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50: 870–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oak A. S., Messinger J. D., and Curcio C. A.. 2014. Subretinal drusenoid deposits: further characterization by lipid histochemistry. Retina. 34: 825–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudolf M., Malek G., Messinger J. D., Clark M. E., Wang L., and Curcio C. A.. 2008. Sub-retinal drusenoid deposits in human retina: organization and composition. Exp. Eye Res. 87: 402–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein M. L., Ferris F. L. 3rd, Armstrong A., Hwang T. S., Chew E. Y., Bressler S. B., and Chandra S. R.; AREDS Research Group. 2008. Retinal precursors and the development of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 115: 1026–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivaprasad S., Bird A., Nitiahpapand R., Nicholson L., Hykin P., Chatziralli I.; and Moorfields UCL AMD Consortium . 2016. Perspectives on reticular pseudodrusen in age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 61: 521–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huisingh C., McGwin G. Jr., Neely D., Zarubina A., Clark M., Zhang Y., Curcio C. A., and Owsley C.. 2016. The association between subretinal drusenoid deposits in older adults in normal macular health and incident age-related macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57: 739–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarubina A. V., Neely D. C., Clark M. E., Huisingh C. E., Samuels B. C., Zhang Y., McGwin G. Jr., Owsley C., and Curcio C. A.. 2016. Prevalence of subretinal drusenoid deposits in older persons with and without age-related macular degeneration, by multimodal imaging. Ophthalmology. 123: 1090–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curcio C. A., Johnson M., Rudolf M., and Huang J. D.. 2011. The oil spill in ageing Bruch membrane. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 95: 1638–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pikuleva I. A., and Curcio C. A.. 2014. Cholesterol in the retina: the best is yet to come. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 41: 64–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritsche L. G., Igl W., Bailey J. N., Grassmann F., Sengupta S., Bragg-Gresham J. L., Burdon K. P., Hebbring S. J., Wen C., Gorski M., et al. 2016. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat. Genet. 48: 134–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Surakka I., Horikoshi M., Mägi R., Sarin A. P., Mahajan A., Lagou V., Marullo L., Ferreira T., Miraglio B., Timonen S., et al. ; ENGAGE Consortium. 2015. The impact of low-frequency and rare variants on lipid levels. Nat. Genet. 47: 589–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgess S., and Davey Smith G.. 2017. Mendelian randomization implicates high-density lipoprotein cholesterol-associated mechanisms in etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 124: 1165–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pennington K. L., and DeAngelis M. M.. 2016. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): associations with cardiovascular disease phenotypes and lipid factors. Eye Vis. (Lond.). 3: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenson R. S., Brewer H. B. Jr., Barter P. J., Björkegren J. L. M., Chapman M. J., Gaudet D., Kim D. S., Niesor E., Rye K. A., Sacks F. M., et al. 2018. HDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: genetic insights into complex biology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15: 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanoni P., Khetarpal S. A., Larach D. B., Hancock-Cerutti W. F., Millar J. S., Cuchel M., DerOhannessian S., Kontush A., Surendran P., Saleheen D., et al. 2016. Rare variant in scavenger receptor BI raises HDL cholesterol and increases risk of coronary heart disease. Science. 351: 1166–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armbrust K. R., and Nussenblatt R. B.. 2017. Blood-retinal barrier, immune privilege, and autoimmunity. In Ryan’s Retina. A. P. Schachat, S. R. Sadda, D. R. Hinton, et al., editors. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam. 656–666. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omri S., Omri B., Savoldelli M., Jonet L., Thillaye-Goldenberg B., Thuret G., Gain P., Jeanny J. C., Crisanti P., and Behar-Cohen F.. 2010. The outer limiting membrane (OLM) revisited: clinical implications. Clin. Ophthalmol. 4: 183–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishikawa M., Sawada Y., and Yoshitomi T.. 2015. Structure and function of the interphotoreceptor matrix surrounding retinal photoreceptor cells. Exp. Eye Res. 133: 3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tserentsoodol N., Gordiyenko N. V., Pascual I., Lee J. W., Fliesler S. J., and Rodriguez I. R.. 2006. Intraretinal lipid transport is dependent on high density lipoprotein-like particles and class B scavenger receptors. Mol. Vis. 12: 1319–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handa J. T., Cano M., Wang L., Datta S., and Liu T.. 2017. Lipids, oxidized lipids, oxidation-specific epitopes, and age-related macular degeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1862: 430–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordiyenko N., Campos M., Lee J. W., Fariss R. N., Sztein J., and Rodriguez I. R.. 2004. RPE cells internalize low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and oxidized LDL (oxLDL) in large quantities in vitro and in vivo. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45: 2822–2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joffre C., Leclère L., Buteau B., Martine L., Cabaret S., Malvitte L., Acar N., Lizard G., Bron A., Creuzot-Garcher C., et al. 2007. Oxysterols induced inflammation and oxidation in primary porcine retinal pigment epithelial cells. Curr. Eye Res. 32: 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gnanaguru G., Choi A. R., Amarnani D., and D’Amore P. A.. 2016. Oxidized lipoprotein uptake through the CD36 receptor activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57: 4704–4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orban T., Palczewska G., and Palczewski K.. 2011. Retinyl ester storage particles (retinosomes) from the retinal pigmented epithelium resemble lipid droplets in other tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 17248–17258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng W., Reem R. E., Omarova S., Huang S., DiPatre P. L., Charvet C. D., Curcio C. A., and Pikuleva I. A.. 2012. Spatial distribution of the pathways of cholesterol homeostasis in human retina. PLoS One. 7: e37926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Remaley A. T., Farsi B. D., Shirali A. C., Hoeg J. M., Brewer H. B., and Jr H. B.. 1998. Differential rate of cholesterol efflux from the apical and basolateral membranes of MDCK cells. J. Lipid Res. 39: 1231–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J., Shirk A., Oram J. F., Lee S. P., and Kuver R.. 2002. Polarized cholesterol and phospholipid efflux in cultured gall-bladder epithelial cells: evidence for an ABCA1-mediated pathway. Biochem. J. 364: 475–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ontsouka E. C., Huang X., Stieger B., and Albrecht C.. 2013. Characteristics and functional relevance of apolipoprotein-A1 and cholesterol binding in mammary gland tissues and epithelial cells. PLoS One. 8: e70407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maminishkis A., Chen S., Jalickee S., Banzon T., Shi G., Wang F. E., Ehalt T., Hammer J. A., and Miller S. S.. 2006. Confluent monolayers of cultured human fetal retinal pigment epithelium exhibit morphology and physiology of native tissue. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47: 3612–3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lyssenko N. N., Nickel M., Tang C., and Phillips M. C.. 2013. Factors controlling nascent high-density lipoprotein particle heterogeneity: ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 activity and cell lipid and apolipoprotein AI availability. FASEB J. 27: 2880–2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nichols A. V., Gong E. L., Blanche P. J., Forte T. M., and Anderson D. W.. 1976. Effects of guanidine hydrochloride on human plasma high density lipoproteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 446: 226–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burstein M., Scholnick H. R., and Morfin R.. 1970. Rapid method for the isolation of lipoproteins from human serum by precipitation with polyanions. J. Lipid Res. 11: 583–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez-Godino R., Garland D. L., and Pierce E. A.. 2016. Isolation, culture and characterization of primary mouse RPE cells. Nat. Protoc. 11: 1206–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganju J. 2006. Diagnostics for assumptions in moderate to large simple clinical trials: do they really help? Stat. Med. 25: 1799–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn K. C., Aotaki-Keen A. E., Putkey F. R., and Hjelmeland L. M.. 1996. ARPE-19, a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line with differentiated properties. Exp. Eye Res. 62: 155–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillips M. C. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of cellular cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 24020–24029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luthi A. J., Lyssenko N. N., Quach D., McMahon K. M., Millar J. S., Vickers K. C., Rader D. J., Phillips M. C., Mirkin C. A., and Thaxton C. S.. 2015. Robust passive and active efflux of cellular cholesterol to a designer functional mimic of high density lipoprotein. J. Lipid Res. 56: 972–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quach D., Vitali C., La F. M., Xiao A. X., Millar J. S., Tang C., Rader D. J., Phillips M. C., and Lyssenko N. N.. 2016. Cell lipid metabolism modulators 2-bromopalmitate, D609, monensin, U18666A and probucol shift discoidal HDL formation to the smaller-sized particles: implications for the mechanism of HDL assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1861: 1968–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nieland T. J., Chroni A., Fitzgerald M. L., Maliga Z., Zannis V. I., Kirchhausen T., and Krieger M.. 2004. Cross-inhibition of SR-BI- and ABCA1-mediated cholesterol transport by the small molecules BLT-4 and glyburide. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1256–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de la Llera-Moya M., Rothblat G. H., Connelly M. A., Kellner-Weibel G., Sakr S. W., Phillips M. C., and Williams D. L.. 1999. Scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) mediates free cholesterol flux independently of HDL tethering to the cell surface. J. Lipid Res. 40: 575–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu B., Gillard B. K., Gotto A. M. Jr., Rosales C., and Pownall H. J.. 2017. ABCA1-derived nascent high-density lipoprotein-apolipoprotein AI and lipids metabolically segregate. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37: 2260–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pilgrim M. G., Lengyel I., Lanzirotti A., Newville M., Fearn S., Emri E., Knowles J. C., Messinger J. D., Read R. W., Guidry C., et al. 2017. Subretinal pigment epithelial deposition of drusen components including hydroxyapatite in a primary cell culture model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58: 708–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson L. V., Forest D. L., Banna C. D., Radeke C. M., Maloney M. A., Hu J., Spencer C. N., Walker A. M., Tsie M. S., Bok D., et al. 2011. Cell culture model that mimics drusen formation and triggers complement activation associated with age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108: 18277–18282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Favari E., Zimetti F., Bortnick A. E., Adorni M. P., Zanotti I., Canavesi M., and Bernini F.. 2005. Impaired ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated sterol efflux from oxidized LDL-loaded macrophages. FEBS Lett. 579: 6537–6542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adorni M. P., Zimetti F., Billheimer J. T., Wang N., Rader D. J., Phillips M. C., and Rothblat G. H.. 2007. The roles of different pathways in the release of cholesterol from macrophages. J. Lipid Res. 48: 2453–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hakamata H., Miyazaki A., Sakai M., Sakamoto Y. I., and Horiuchi S.. 1998. Cytotoxic effect of oxidized low density lipoprotein on macrophages. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 5: 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Du M., Wu M., Fu D., Yang S., Chen J., Wilson K., and Lyons T. J.. 2013. Effects of modified LDL and HDL on retinal pigment epithelial cells: a role in diabetic retinopathy? Diabetologia. 56: 2318–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamada Y., Tian J., Yang Y., Cutler R. G., Wu T., Telljohann R. S., Mattson M. P., and Handa J. T.. 2008. Oxidized low density lipoproteins induce a pathologic response by retinal pigmented epithelial cells. J. Neurochem. 105: 1187–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trimble W. S., and Grinstein S.. 2015. Barriers to the free diffusion of proteins and lipids in the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 208: 259–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kay P., Yang Y. C., and Paraoan L.. 2013. Directional protein secretion by the retinal pigment epithelium: roles in retinal health and the development of age-related macular degeneration. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 17: 833–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duncan K. G., Hosseini K., Bailey K. R., Yang H., Lowe R. J., Matthes M. T., Kane J. P., LaVail M. M., Schwartz D. M., and Duncan J. L.. 2009. Expression of reverse cholesterol transport proteins ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) and scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 93: 1116–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ananth S., Gnana-Prakasam J. P., Bhutia Y. D., Veeranan-Karmegam R., Martin P. M., Smith S. B., and Ganapathy V.. 2014. Regulation of the cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 in retina in hemochromatosis and by the endogenous siderophore 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1842: 603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ishida B. Y., Duncan K. G., Bailey K. R., Kane J. P., and Schwartz D. M.. 2006. High density lipoprotein mediated lipid efflux from retinal pigment epithelial cells in culture. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90: 616–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Storti F., Raphael G., Griesser V., Klee K., Drawnel F., Willburger C., Scholz R., Langmann T., von Eckardstein A., Fingerle J., et al. 2017. Regulated efflux of photoreceptor outer segment-derived cholesterol by human RPE cells. Exp. Eye Res. 165: 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kienesberger P. C., Pulinilkunnil T., Nagendran J., and Dyck J. R.. 2013. Myocardial triacylglycerol metabolism. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 55: 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu Y., Conlon D. M., Bi X., Slovik K. J., Shi J., Edelstein H. I., Millar J. S., Javaheri A., Cuchel M., Pashos E. E., et al. 2017. Lack of MTTP activity in pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes and cardiomyocytes abolishes apoB secretion and increases cell stress. Cell Reports. 19: 1456–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krzystanek M., Pedersen T. X., Bartels E. D., Kjaehr J., Straarup E. M., and Nielsen L. B.. 2010. Expression of apolipoprotein B in the kidney attenuates renal lipid accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 10583–10590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fliesler S. J., and Bretillon L.. 2010. The ins and outs of cholesterol in the vertebrate retina. J. Lipid Res. 51: 3399–3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bazan N. G., Molina M. F., and Gordon W. C.. 2011. Docosahexaenoic acid signalolipidomics in nutrition: significance in aging, neuroinflammation, macular degeneration, Alzheimer’s, and other neurodegenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 31: 321–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rodriguez I. R., Clark M. E., Lee J. W., and Curcio C. A.. 2014. 7-Ketocholesterol accumulates in ocular tissues as a consequence of aging and is present in high levels in drusen. Exp. Eye Res. 128: 151–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodriguez I. R., and Fliesler S. J.. 2009. Photodamage generates 7-keto- and 7-hydroxycholesterol in the rat retina via a free radical-mediated mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 85: 1116–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ryeom S. W., Sparrow J. R., and Silverstein R. L.. 1996. CD36 participates in the phagocytosis of rod outer segments by retinal pigment epithelium. J. Cell Sci. 109: 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Picard E., Houssier M., Bujold K., Sapieha P., Lubell W., Dorfman A., Racine J., Hardy P., Febbraio M., Lachapelle P., et al. 2010. CD36 plays an important role in the clearance of oxLDL and associated age-dependent sub-retinal deposits. Aging (Albany NY). 2: 981–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rajapakse D., Peterson K., Mishra S., and Wistow G.. 2017. Serum starvation of ARPE-19 changes the cellular distribution of cholesterol and Fibulin3 in patterns reminiscent of age-related macular degeneration. Exp. Cell Res. 361: 333–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nelson C. P., Goel A., Butterworth A. S., Kanoni S., Webb T. R., Marouli E., Zeng L., Ntalla I., Lai F. Y., Hopewell J. C., et al. 2017. Association analyses based on false discovery rate implicate new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 49: 1385–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]