Abstract

Regulating blood cholesterol (Chol) levels by pharmacotherapy has successfully improved cardiovascular health. There is growing interest in the role of Chol precursors in the treatment of diseases. One sterol precursor, desmosterol (Des), is a potential pharmacological target for inflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders. However, elevating levels of the precursor 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) by inhibiting the enzyme 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase is linked to teratogenic outcomes. Thus, altering the sterol profile may either increase risk toward an adverse outcome or confer therapeutic benefit depending on the metabolite affected by the pharmacophore. In order to characterize any unknown activity of drugs on Chol biosynthesis, a chemical library of Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs was screened for the potential to modulate 7-DHC or Des levels in a neural cell line. Over 20% of the collection was shown to impact Chol biosynthesis, including 75 compounds that alter 7-DHC levels and 49 that modulate Des levels. Evidence is provided that three tyrosine kinase inhibitors, imatinib, ponatinib, and masitinib, elevate Des levels as well as other substrates of 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase, the enzyme responsible for converting Des to Chol. Additionally, the mechanism of action for ponatinib and masitinib was explored, demonstrating that protein levels are decreased as a result of treatment with these drugs.

Keywords: cholesterol/biosynthesis, drug therapy, mass spectrometry, sterols, 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase, 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase, high-throughput screening

Maintenance of blood cholesterol (Chol) levels through deliberate change in diet or the use of pharmacotherapy is frequently undertaken to improve health. For example, the results from a meta-analysis of statin use in human populations aimed to lower total Chol levels showed a decreased mortality associated with cardiovascular disease (1). More recently, a debate has arisen concerning the effect of statins on the CNS with clinical observations showing both positive and negative outcomes on neurological disorders as a result of statin use (2). Indeed, it is not surprising that modifying lipid metabolism could impact neurological health, because the brain consists of more than 25% of all the Chol in the human body. Additionally, because Chol cannot freely cross the blood-brain barrier, the CNS is required to maintain a separate pool of Chol that is independent from that of the rest of the body. Whether the neurological changes associated with statin use are caused by reducing Chol levels or by another pleiotropic mechanism is not known (3).

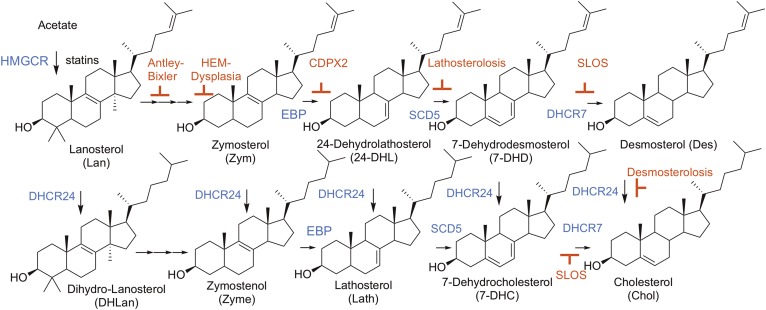

Statins target Chol formation at the transformation promoted by HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR), the first committed step of biosynthesis. But there are over a dozen subsequent steps required to produce the final product (4), see Fig. 1. Drugs that modulate any of these subsequent steps will perturb sterol homeostasis and provide a potential approach to reduce Chol levels. For example, a compound that inhibits 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR24) would reduce Chol levels, but a consequence of such an approach would also be to increase levels of the substrate for DHCR24, desmosterol (Des). By the same token, inhibitors of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) would increase 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) at the expense of Chol.

Fig. 1.

Chol biosynthetic pathway. Chol and key sterol precursor structures are shown with relevant enzymes indicated in blue. Shown in red are the syndromes caused by inborn errors of Chol biosynthesis at the associated step in Chol biosynthesis.

While there may be instances in which manipulation of post-lanosterol (Lan) sterol levels is therapeutically desirable (5), these potential therapies are clinically tempered by the fact that perturbing sterol homeostasis during fetal and neuronal development will likely have pathological consequences (6). A number of known syndromes (Fig. 1) are the result of defects in genes that encode the enzymes involved in the Chol biosynthetic pathway. Two such recessive disorders that clinically present with hypocholesterolemia, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and desmosterolosis, are caused by mutations in the DHCR7 and DCHR24 genes, respectively.

The severity of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome is directly linked to specific mutations in the gene that encodes DHCR7, the enzyme responsible for the conversion of 7-DHC to Chol (7–9). Over 150 known pathogenic mutations of DHCR7 have been reported (9–11), and a carrier frequency up to 3% has been suggested (12). Patients with defective DHCR7 that survive in utero, clinically present with craniofacial deformities and CNS malformations, and are often diagnosed with neurobehavioral deficits (6). Even though low Chol levels may impair normal neuronal development by disrupting cell division and the development of myelin sheathes (13), elevated 7-DHC levels may also contribute to the pathological outcomes. The 7-DHC has the potential to induce cell stress responses because it is highly oxidizable and can contribute to the exaggerated formation of free radicals that are known to damage nucleotides, proteins, and other lipids (14, 15). In support of the pathological potential of targeting DHCR7, it has been demonstrated that chemically modulating 7-DHC and Chol levels with the known DHCR7 inhibitor, AY-9944, leads to numerous developmental and behavioral deficits in rodent models (16, 17).

Desmosterolosis, a syndrome resulting from defects in DHCR24, is an even more rare syndrome with only a handful of reported cases (18). DHCR24 is known to act on multiple metabolites within the Chol biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1) with some tissue specificity. The brain, for example, is reported to have an affinity to metabolize zymosterol (Zym) (19). Any defect or inhibition of DHCR24 function would ultimately lead to reduced levels of all sterols that are immediate products of that enzyme, including Chol, with a corresponding increased level of Des. It should be noted that there is growing interest in the role of Des in translational science because this sterol has been linked to a variety of neurological and cardiovascular disorders, as well as increased susceptibility to viral infections (20–22). Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that specifically targeting Des levels could confer regulation over inflammatory signaling processes in macrophages (23, 24).

There have been several studies that have individually identified a handful of small molecules that modulate levels of 7-DHC and Des in cell culture. Recently a neuroblastoma cell line [Neuro2a (WT-N2a)] and a Dhcr7-deficient derivative of that cell [Dhcr7-deficient Neuro2a (D7-N2a)] have been used to identify active compounds in a National Institutes of Health library of clinically relevant molecules (25, 26). High-throughput screening methods developed in those studies permitted us to evaluate a collection of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved prescription drugs more relevant to public health. A majority of these compounds had not been previously assessed for their potential beneficial or detrimental impact on human health by compromising Chol biosynthesis. Here, we report the outcome of that study; a screen of a chemical library of 1,003 FDA-approved drugs in which more than 100 compounds were found to have a significant effect on levels of 7-DHC or Des in WT-N2a or D7-N2a cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). HPLC grade solvents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA). All cell culture reagents were from Mediatech (Manassas, VA), Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY), and Greiner Bio-One (Monroe, NC). All natural and isotopically labeled sterol standards used in this study are available from Kerafast, Inc. (Boston, MA). Other materials were purchased as follows: 10% NuPage Novex Bis-Tris® precast mini gel (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), PVDF membrane and Simply Blue (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), IRDye® 800CW streptavidin (925-32230; Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE), and blocking buffer (Rockland, Gillbertsville, PA or Odyssey blocking buffer). Antibodies of DHCR24 (anti-seladin-1, ab40490) and actin (ab8299) were purchased from Abcam and Santa-Cruz, respectively. Appropriate secondary antibodies (anti-mouse and anti-rabbit) that can be visualized at either 700 nm or 800 nm were purchased from either Li-Cor or Life Technology.

Cell culture

The neuroblastoma cell line, WT-N2a, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). N2a cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with l-glutamine, 10% FBS (VWR/Seradigm, Radnor, PA), and penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. D7-N2a cells were generated as previously described (27). All cells were subcultured every 4–5 days up to ten passages, and the culture medium was changed every 2 days.

Chemical screening and exposures

All screening experiments were conducted in the Vanderbilt University High-Throughput Screening Facility as previously described (25, 26). Briefly, 2.5 nl of each compound (dissolved in DMSO) from the FDA-approved Drug Library (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX) were deposited in a single well of a black 384-well cell culture plate using a Labcyte Echo 550/555 (Sunnyvale, CA). N2a cells were trypsinized, counted, resuspended in DMEM medium with reduced serum (0.5% FBS), and 25 μl of cell suspension were dispensed to 384-well plates (on top of predeposited compounds) using Multidrop Combi (Thermo Scientific) at a final plating density of 1.00 × 104 WT-N2a cells per well and 1.25 × 104 D7-N2a cells per well. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, Hoechst dye (Molecular Probes) was added using Agilent Velocity 11 Bravo and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. Cells were imaged using ImageXpress Micro XL (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with a 4× objective. Following imaging, the medium was removed and 80 μl of methanol containing internal standards (0.0166 nmol for d7-7-DHC, 0.125 nmol for 13C3-Des, 0.115 nmol for 13C3-Lan, and 0.0434 nmol for d7-Chol per well) were added using the Multidrop Combi. The 384-well plate was placed on a rotary shaker for 20 min at room temperature and then centrifuged for 10 min using a Sorvall swing rotor. The supernatant was transferred by an automated liquid handler, Agilent Velocity 11 Bravo, to a plate (Waters #186002631, 100 μl flat bottomed) with 50 μg of 4-phenyl-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione (PTAD) predeposited in each well. The plates were immediately sealed with Easy Pierce Heat Sealing Foil (Thermo Scientific; AB-1720), followed by 20 min of agitation at room temperature. The sealed plates were kept at −80°C until LC-MS analysis. For verification experiments, WT-N2a and D7-N2a cells were seeded onto black 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) in DMEM supplemented with l-glutamine and 10% FBS (VWR/Seradigm) at 0.75 × 104 WT-N2a cells per well and 1.00 × 104 D7-N2a cells per well. Lead-hit chemical exposure plates containing exposures at 2× were created by depositing known concentrations of chemical on a 96-well plate backfilled to 40 nl with DMSO using Labcyte Echo 550/555 followed by the addition of 200 μl of DMEM supplemented with l-glutamine and N-2 supplement (Thermo Fisher). After 24 h from initial seeding, medium on cells was replaced with 50 μl of DMEM supplemented with l-glutamine and N-2 supplement (Thermo Fisher) followed by the addition of 50 μl of exposure medium from the lead-hit chemical master plate, as indicated for each experiment. After an additional 24 h, 50 μl of medium were collected for cytotoxicity analysis, as determined by LDH release with the CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Subsequently, cells were prepped for mass spectrometric analysis as with the 384-well plates, but to each well in the 96-well plate the internal standards were added (10 μl of stock solution in methanol: 0.087 nmol of d7-Chol, 0.033 nmol of d7-7-DHC, 0.25 nmol of 13C3-Des, and 0.23 nmol of 13C3-Lan) and methanol (100 μl). The plate was gently shaken on an orbital shaker for 20 min at room temperature to lyse the cells and extract the sterols. The supernatant was transferred to a PTAD-predeposited 96-well plate (0.2 mg per well). The plates were sealed with Easy Pierce heat sealing foil (Thermo Scientific; AB-1720) and allowed to react for 30 min at room temperature. The sealed plates were kept at −80°C until LC-MS analysis.

LC-MS analysis

The sealed plates were analyzed on an Acquity UPLC system equipped with an ANSI-compliant well plate holder. The sterols (10 μl injection) were analyzed on an UPLC C18 column (Acquity UPLC BEH C18, 1.7 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm) with 100% methanol (0.1% v/v acetic acid) mobile phase at a flow rate of 500 μl/min and runtime of 1.2 min. A TSQ Quantum Ultra tandem mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) was used for MS detections, and data were acquired with a Finnigan Xcalibur software package. Selected reaction monitoring (SRM) of the PTAD derivatives was acquired in the positive ion mode using atmospheric pressure chemical ionization. MS parameters were optimized for the 7-DHC-PTAD adduct and were as follows: auxiliary nitrogen gas pressure at 55 psi and sheath gas pressure at 60 psi; discharge current at 22 μA and vaporizer temperature at 342°C. Collision-induced dissociation was optimized at 12 eV under 1.0 mTorr of argon. The SRM transitions of precursors (sterol with PTAD moiety) metabolite m/z → product ions m/z included: 7-DHC m/z 560 → 365, d7-7-DHC m/z 567 → 372, Des m/z 592 → 365, Lan m/z 634 → 602, 13C3-Des m/z 595 → 368, and 13C3-Lan m/z 637 →605. Pseudo-SRM transitions of m/z 369 → 369 and m/z 376 → 376 were utilized to monitor Chol and d7-Chol, respectively, because Chol does not react with PTAD. Final sterol numbers are reported as nanomoles per million cells.

GC-MS analysis

The remaining underivatized 100 μl of the supernatant of the verification experiments from each sample in each well were transferred to vials and concentrated on a SpeedVac concentrator for GC-MS analysis (Agilent Technologies; 7890B). To each vial, N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)-trifluoroacetamide (50 μl) was added, vortexed well, and allowed to react for 30 min. The sample (5 μl) was injected onto the column (SPB-5, 0.25 μm, 0.32 mm × 30 m) with a temperature program of 220–300°C (5 min) at 20°C/min and helium flow rate of 2.0 ml/min. The data were collected in full scan mode and the following ions extracted for quantitation relative to d7-Chol: 458 for Chol, zymostenol, and lathosterol; 456 for Zym and dehydrolathosterol (DHL); 349 (M-105) for dehydrodesmosterol; 393 (M-105) for Lan; 395 (M-105) for dihydrolanosterol (DHLan); 486 for dimethylzymostenol; and 465 for d7-Chol. Des and 7-DHC were not analyzed by GC-MS because they co-elute. The remaining sterol intermediates were not detected. Final sterol numbers are reported as nanomoles per million cells.

Immunoblot analysis

N2a-cells were grown in 60 mm plates (Genesee Scientific) for 24 h in complete medium followed by incubation with chemicals (100 nM) dissolved in DMSO in N-2-supplemented medium for 24 h. Experimental conditions were optimized so that at the conclusion of the experiment, ∼1.5 × 106 cells were harvested for immunoblot analysis. Cells were washed twice in ice-cold 1× PBS, lysed with lysis buffer, and then normalized by protein concentration as determined by DC™ protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Samples were then resolved by 10% NuPAGE Novex BisTris® gel and then transferred to PVDF membrane. The transferred proteins were incubated with antibodies of DHCR24 and actin, (1:1,000) overnight in the cold room at 4°C. Alexa Fluor 680®-labeled secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse was used to detect target proteins. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using Image Studio (version 5.2) (Li-Cor).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) in combination with spreadsheet-based software including Excel® (Microsoft®, Redmond, WA). P values <0.05 were considered significant; specific analyses used are indicated with each set of data and experiment. In addition, we calculated screening window coefficients, “Z” and “Z score”. (28) These factors reflect the assay dynamic range and data variation associated with the measurements. Unless otherwise noted, at least three replicates of all experiments were undertaken.

RESULTS

High-throughput screening of FDA drugs targeting Chol biosynthesis

One thousand and three FDA-approved drugs were screened in WT-N2a and D7-N2a cells for their potential to affect late-stage Chol biosynthesis. The use of a high-sensitivity UPLC-MS-(SRM) analytical protocol and a high-throughput screening platform permitted the rapid analysis of 7-DHC, Des, Lan, and Chol following a 24 h exposure to the FDA drugs at 1 μM (29). In addition to the library compounds, a number of positive controls were utilized during the screening procedure to assess the functional health and activity of the Chol biosynthetic pathway in both neural cell lines. These controls included simvastatin (to inhibit HMGCR), econazole (to inhibit Cyp51), and aripiprazole (to inhibit DHCR7). Lead-hit chemicals were determined by utilizing the 24 vehicle control wells (0.01% DMSO) on each plate as a reference for each compound’s exposure effect resulting in a Z score. The screen was conducted in duplicate for each cell line. The outcome of the high throughput screen across both cell lines demonstrated that over 200 of the compounds in the library impacted Chol biosynthesis significantly, as determined by a Z score found to be greater than or less than three standard deviations from the mean, i.e., Z greater than +3 or Z less than −3 (see the supplemental material). For additional comparison, WT- and D7-N2a cells were exposed to 100 nM AY-9944 and 1,000 nM triparanol to demonstrate inhibition of DHCR7 and DHCR24 with prototypical Chol biosynthesis inhibitors, respectively (supplemental Fig. S1). When Z scores were calculated for these compounds at their optimal effect, AY-9944 exposed to WT-N2a cells resulted in a Z score of 160.1 for an increase in 7-DHC levels, whereas triparanol exposed to D7-N2a cells resulted in a Z score of 3.7 with respect to Des.

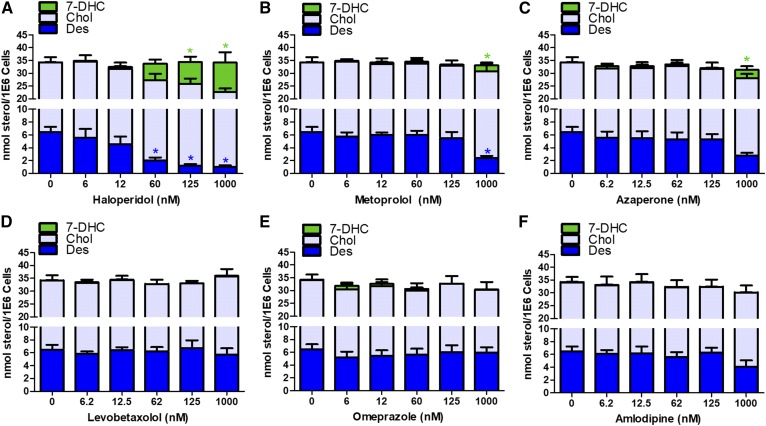

FDA drugs elevate 7-DHC levels

Of the lead hits, 75 of the drugs altered the levels of 7-DHC in one or both cell lines (Table 1). Compounds that reduced 7-DHC levels (Z score less than −3) were found exclusively in those experiments that used D7-N2a, while drugs that increased 7-DHC with Z scores greater than +3 were found, for the most part, in the WT-N2a cultures. With one exception, the most potent drugs found in WT-N2a were found to have Z scores greater than +3 in the D7-N2a cells. Nine compounds in the library were very potent, increasing levels of 7-DHC with a Z score greater than 100. Of these nine drugs, haloperidol, aripiprazole, and domiphen had previously been reported to affect 7-DHC levels in cell culture studies and/or in vivo (30). Six of the compounds (nebivolol, rotigotine, iloperidone, ziprasidone, dyclonine, and penfluridol) had not been previously linked to elevated 7-DHC. In order to verify the results of the initial screen, we examined these six potent drugs in cultures of WT-N2a and D7-N2a cells across a range of concentrations from 6 to 1,000 nM. No cytotoxicity was found in any of these exposures (data not shown) and the experiments confirmed the effect on 7-DHC for each of the six drugs at 1,000 nM in the WT-N2a cell line (Fig. 2). Nebivolol and rotigotine had a significant effect on sterol homeostasis in WT-N2a cells at concentrations as low as 60 nM, while dyclonine affected sterol levels at 125 nM (Fig. 2A, B, E). In all exposures in which 7-DHC was significantly elevated, Des levels were significantly reduced and Chol levels unchanged. Although the drugs perturbed sterol homeostasis, they did not affect the total sterol cellular levels (Chol + 7-DHC + Des) measured for any of the drugs at any of the concentrations tested. The six drugs that had a Z score of more than 100 in WT-N2a cells were also cultured with the cell line deficient in Dhcr7, D7-N2a, but no significant perturbation of sterol levels was found even at the highest concentrations of the drugs tested, 1,000 nM (see supplemental Fig. S2).

TABLE 1.

Lead-hit compounds in FDA-approved chemical library altering levels of 7-DHC

| WT-N2a Cells Only | Common | D7-N2a Cells Only | ||||

| Drug | Z score | Drug | Z Score | Drug | Z score | |

| WT-N2a | D7-N2a | |||||

| Dyclonine | 109.4 | Nebivolol | 233.6 | 7.9 | Bromhexine | 3.8 |

| Dronedarone | 46.6 | Haloperidol | 224.8 | 6.2 | Econazole | −3.0 |

| Pramoxine | 26.7 | Rotigotine | 220.4 | 9.3 | Hydroxyzine | −3.1 |

| Vitamin D3 | 12.9 | Aripiprazole | 202.8 | 4.5 | Sorafenib | −3.1 |

| Alverine | 12.9 | Iloperidone | 163.7 | 8.1 | Ciclopirox | −3.3 |

| Buflomedil | 12.6 | Domiphen | 112.0 | 5.5 | Bortezomib | −3.3 |

| Nafamostat | 9.4 | Ziprasidone | 112.0 | 6.6 | Imatinib | −3.4 |

| Mirabegron | 8.9 | Penfluridol | 105.2 | 7.3 | Progesterone | −3.4 |

| Esmolol | 8.8 | Procaine | 97.2 | 6.6 | Trimebutine | −3.4 |

| Clorprenaline | 7.3 | Azaperone | 77.4 | 6.1 | Clotrimazole | −3.5 |

| Alexidine | 6.3 | Ibutilide | 72.3 | 5.5 | Cetylpyridinium | −3.5 |

| Tetracaine | 6.1 | Metoprolol | 62.8 | 6.3 | Amorolfine | −3.5 |

| Droperidol | 5.2 | Oxybutynin | 50.1 | 3.9 | Sulconazole | −3.6 |

| Levetiracetam | 5.2 | Naftopidil | 47.0 | 5.5 | Tamoxifen | −3.7 |

| Camylofin | 5.1 | Pergolide | 34.5 | 3.6 | Rosuvastatin | −3.9 |

| Cleviprex | 5.0 | Dofetilide | 17.2 | 3.7 | Masitinib | −3.9 |

| Levobetaxolol | 4.7 | Cinacalcet | 17.0 | 6.0 | Mevastatin | −4.1 |

| Articaine | 4.5 | Lofexidine | 13.5 | 3.0 | Pregnenolone | −4.1 |

| Betaxolol | 4.2 | Ritodrine | 8.9 | 3.6 | Clomiphene | −4.1 |

| Sulfamethizole | 4.0 | Toremifene | −4.1 | |||

| Geniposide | 3.8 | Bazedoxifene | −4.1 | |||

| Butenafine | 3.7 | Evista | −4.1 | |||

| Formoterol | 3.3 | Fenticonazole | −4.2 | |||

| Dapoxetine | 3.3 | Emetine | −4.2 | |||

| Amfenac | 3.3 | Butoconazole | −4.2 | |||

| Zaltoprofen | 3.2 | Fluvastatin | −4.2 | |||

| Terbinafine | 3.1 | Simvastatin | −4.2 | |||

| Tropisetron | 3.1 | Pitavastatin | −4.3 | |||

Fig. 2.

Verification of 7-DHC elevating lead-hit compounds. WT-N2a cells were exposed to lead hits at the indicated concentrations for 24 h followed by sterol analysis normalized by cell count. Des (blue, bottom), Chol (gray, middle), 7-DHC (green, top) levels are shown as average (n = 3) with SEM (*P < 0.05, as determined by Dunnett’s posttest of one-way ANOVA, is shown immediately above its respective bar in linked color).

FDA drugs elevating Des levels

All lead-hit compounds identified in the screens that increased Des levels in WT- and D7-N2a cells had a Z score less than 12, see Table 2. This is in marked contrast to the lead hits that elevate 7-DHC, which had Z scores as high as 230. Ten compounds were found to increase levels of Des in both the WT- and D7-N2a cells (Table 2) under the conditions of the high-throughput screen exposure paradigm. These drugs were subjected to further study to determine the nature of the perturbation on sterol levels and to examine their dose-response effect in relation to Chol homeostasis. Chol levels were significantly lowered by all drugs in the WT-N2a cell line at the 62 nM exposure, except for vandetanib and darifenacin, which only lowered Chol levels at the highest exposure of 1,000 nM (supplemental Fig. S3). Des levels were elevated in WT-N2a cells in at least one dose for all tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (imatinib, masinitinb, ponatinib, and vandetanib) and steroids (pregnenolone and progesterone) tested (supplemental Fig. S3). When these compounds are exposed to D7-N2a cells, the absolute levels of Des increase or, in a few cases, the fraction of Des in the sterols measured was found to increase (supplemental Fig. S4). Chol levels did not change significantly as a function of drug concentration, but the total sterols measured (Chol + 7-DHC + Des) decreased with increasing drug concentration, principally because of a loss of 7-DHC in the cells (supplemental Fig. S4). Subsequent GC-MS studies in both WT-N2a and D7-N2a provide additional insight, as illustrated in Tables 3 and 4, respectively, with the TKIs, masitinib and ponatinib, and the steroid, pregnenolone. While Des levels were elevated by each drug at 62 nM in the WT-N2a cells (Table 3), the most significant change observed was in the D7-N2a cells as an increase of 7-dehydrodesmosterol (7-DHD), a precursor to both Des and 7-DHC, see Fig. 1. These results confirmed the previous conclusions that the steroid, pregnenolone, impacts DHCR24 function (31). Additionally, the two TKIs utilized in this experiment also appear to impact the function of DHCR24, which would be similar to previous findings associated with another TKI, imatinib (25). In support of this notion, both ponatinib and masitinib significantly caused elevated levels of 24-DHL in addition to 7-DHD and Des in the D7-N2a cell line (Table 4), wherein all three sterols are known to be substrates of DHCR24 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Lead-hit compounds in FDA chemical library altering levels of Des

| WT-N2a Cells Only | Common | D7-N2a Cells Only | ||||

| Drug | Z score | Drug | Z Score | Drug | Z score | |

| WT-N2a | D7-N2a | |||||

| Amfenac | 11.7 | Imatinib | 9.4 | 8.5 | Bazedoxifene | 7.9 |

| Sulfamethizole | 9.5 | Pregnenolone | 10.3 | 9.9 | Clomiphene | 4.8 |

| Gefitinib | 8.8 | Masitinib | 8.0 | 5.5 | Orphenadrine | 4.2 |

| Bosutinib | 8.3 | Progesterone | 8.8 | 7.8 | Tolmetin | 3.3 |

| Natamycin | 4.7 | Vandetanib | 5.5 | 3.7 | Idoxuridine | 3.3 |

| Carmofur | 4.3 | Ponatinib | 4.7 | 4.4 | Rosuvastatin | −3.0 |

| Asenapine | 4.1 | Clemastine | 3.7 | 5.4 | Cabozantinib | −3.1 |

| Zaltoprofen | 4.1 | Raloxifene | 3.5 | 8.0 | ||

| Dutasteride | 4.0 | Darifenacin | 3.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Teniposide | 3.9 | Toremifene | 3.0 | 6.2 | ||

| Mepivacaine | 3.9 | Simvastatin | −3.2 | −4.0 | ||

| Fulvestrant | 3.7 | Mevastatin | −3.9 | −3.6 | ||

| Etoposide | 3.6 | Sulconazole | −4.0 | −3.1 | ||

| Methylprednisolone | 3.6 | Amorolfine | −4.5 | −3.9 | ||

| Estradiol cypionate | 3.4 | Fluvastatin | −4.6 | −4.2 | ||

| Mercaptopurine | 3.4 | Fenticonazole | −4.6 | −4.0 | ||

| Topotecan | 3.3 | Butoconazole | −4.7 | −4.1 | ||

| Amlodipine | 3.1 | Pitavastatin | −4.7 | −4.2 | ||

| Domiphen | −3.0 | |||||

| Cetrimonium | −3.2 | |||||

| Trimebutine | −3.5 | |||||

| Bifonazole | −3.6 | |||||

| Econazole | −3.9 | |||||

| Clotrimazole | −4.0 | |||||

TABLE 3.

Measurements of sterols analyzed following WT-N2a cells’ exposure to DHCR24 inhibitors for 24 h at the indicated concentrations

| Sterol | Vehicle | Masitinib (nM) | Ponatinib (nM) | Pregnenolone (nM) | ||||||

| 62 | 125 | 1,000 | 62 | 125 | 1,000 | 62 | 125 | 1,000 | ||

| Lan | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| DHLan | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Zym | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Zyme | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 24-DHL | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Lath | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 7-DHD | 0.21 ± 0.05 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.17 | 0.29 ± 0.14 | 0.25 ± 0.18 | 0.50 ± 0.36 | 0.51 ± 0.23 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.03 |

| 7-DHC | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.1 ± 0.01 |

| Des | 6.2 ± 0.16 | 7.7 ± 0.41a | 8.0 ± 0.50a | 5.9 ± 0.22 | 8.8 ± 0.79a | 7.0 ± 0.71 | 4.4 ± 0.21a | 9.1 ± 0.36a | 11 ± 0.54a | 8.8 ± 0.29a |

| Chol | 13 ± 0.28 | 11 ± 0.80a | 8.9 ± 0.53a | 9.1 ± 0.24a | 9.4 ± 0.69a | 8.8 ± 0.50a | 12 ± 0.51a | 8.9 ± 0.42a | 9.5 ± 0.25a | 8.9 ± 0.73a |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Zyme, zymostenol; Lath, lathosterol; n.d., not detected.

Significant difference to control, P < 0.05.

TABLE 4.

Measurements of sterols analyzed following D7-N2a cells’ exposure to DHCR24 inhibitors for 24 h at the indicated concentrations

| Sterol | Vehicle | Masitinib [nM] | Ponatinib [nM] | Pregnenolone [nM] | ||||||

| 62 | 125 | 1,000 | 62 | 125 | 1,000 | 62 | 125 | 1,000 | ||

| Lan | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| DHLan | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Zym | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Zyme | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 24-DHL | 0.51 ± 0.23 | 0.73 ± 0.31 | 1.4 ± 0.16a | 0.46 ± 0.15 | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 1.4 ± 0.6a | 0.68 ± 0.25 | 0.97 ± 0.21 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.14 |

| Lath | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 7-DHD | 5.3 ± 0.33 | 9.2 ± 2.1 | 11 ± 2.2a | 12 ± 0.57a | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 10 ± 2.5a | 7.1 ± 2.0a | 15 ± 2.4a | 10 ± 3.0 | 10 ± 1.2 |

| 7-DHC | 7.0 ± 0.23 | 3.4 ± 0.31a | 2.4 ± 0.19a | 0.82 ± 0.07a | 1.7 ± 0.01a | 0.73 ± 0.03a | 0.75 ± 0.14a | 2.2 ± 0.77a | 1.1 ± 0.09a | 0.89 ± 0.15a |

| Des | 1.4 ± 0.04 | 3.3 ± 0.45a | 4.2 ± 0.44a | 3.0 ± 0.12a | 3.2 ± 0.19a | 3.0 ± 0.28a | 3.2 ± 0.21a | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 4.4 ± 0.03a | 5.2 ± 1.1a |

| Chol | 12 ± 0.28 | 14 ± 1.8 | 15 ± 0.50 | 13 ± 0.19 | 13 ± 0.39 | 12 ± 0.09 | 13 ± 0.26 | 12 ± 0.38 | 14 ± 0.29 | 13 ± 0.20 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Zyme, zymostenol; Lath, lathosterol; n.d., not detected.

Significant difference to control, P < 0.05.

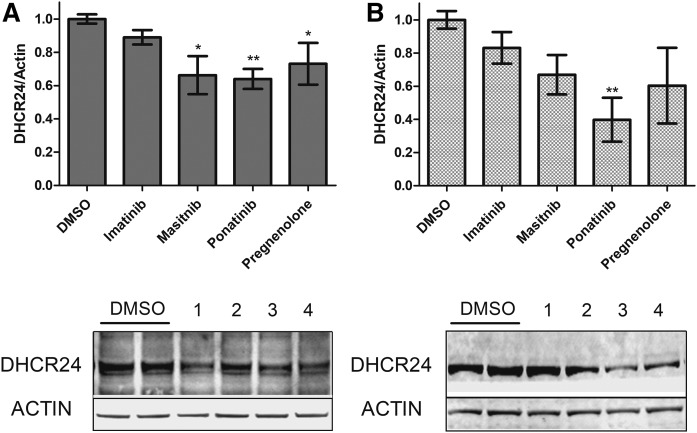

Masitinib and ponatinib impact DHCR24 protein expression

It is possible that these DHCR24-active compounds cause an elevation of Des by altering transcription of the gene DHCR24. There are contradictory reports that TKIs, including imatinib, increase transcription of DHCR24 (32, 33), thus we examined the effect of TKIs on Dhcr24 mRNA expression. We utilized a uniform dose of 100 nM for all compounds, as this concentration is lower than the majority of the Cmax of TKIs in humans (34). No significant change in mRNA levels was observed in the WT-N2a cells (supplemental Fig. S5). We then measured DHCR24 protein levels to provide an additional perspective by conducting DHCR24 immunoblot analyses at the same drug exposure times that were used for determination of sterol levels. Cells exposed to pregnenolone had significantly lower DHCR24 protein levels compared with vehicle control in WT-N2a cells (Fig. 3A). Masitinib and ponatinib decreased protein expression as well (Fig. 3A). When D7-N2a cells were similarly tested, only ponatinib was observed to lower DHCR24 protein expression (Fig. 3B); however, it should be noted that the D7-N2a cell line had significantly elevated levels of DHCR24 protein levels compared with its WT-N2a counterpart (supplemental Figs. S5, S6) and, as such, is likely confounding the effect of masitinib and pregnenolone on DHCR24 expression in this particular cell line. In contrast, imatinib had no statistically significant impact on the expression of DHCR24 in either cell line, suggesting that this TKI may have an alternate means to regulate DHCR24 activity.

Fig. 3.

Impact of verified Des elevators on DHCR24 protein expression. WT-N2a cells (A) and D7-N2a cells (B) were exposed to the indicated DHCR24 active compounds at 100 nM for 24 h followed by immunoblot analysis. Representative immunoblots for each experiment are shown below the graphs with the following key: 1, imatinib; 2, masitinib; 3, ponatinib; and 4, pregnenolone. DHCR24 expression was normalized to actin and then averaged (n = 3) with SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, as determined by Dunnett’s posttest of one-way ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

High-throughput screening for compounds that target Chol biosynthesis

Multiple analytical methods were used to screen compounds in a chemical library of FDA-approved drugs in two variants of the N2a cell line: the background cell type or “WT” (WT-N2a) and a Dhcr7-deficient cell line (D7-N2a). Our primary analytical protocol makes use of a derivatization procedure (PTAD) to provide sensitive, selective, and rapid assays of the penultimate sterols in the Chol biosynthetic pathway, Des and 7-DHC. This method was adapted to the use of high-throughput screening instruments to semi-automate the experimental procedures from cell culture to analysis. The protocol provides absolute levels of Des, 7-DHC, and Chol normalized to cell count in UPLC/MS runs of 1 min, making possible the ability to screen commercial chemical libraries for drugs that impact Chol biosynthesis. For the data presented here, less than 3 days of mass spectrometer instrument time were used to provide the lead-hit prioritization of compounds that affect some step in Chol biosynthesis, from HMGCR to DHCR7 or DHCR24. A first-pass screen using the PTAD protocol identifies an initial lead-hit list, which can then be verified by the use of established analytical methods to provide a more complete sterol profile. These established methods (35, 36) consume more instrument time making them less amenable for use with high throughput screening. It should be noted that the experimental conditions of the screening procedures do involve the use of a medium with a known quantity of Chol, a known component of serum. Thus follow-up multiday experiments involving the conditioning of cells to serum-free, and thus Chol-free, medium were conducted to minimize confounding sources of Chol detected in the analysis.

N2a cells are exceptionally useful for screening purposes because they are relatively rich in Chol (16 nmol per million cells) and Des (2.5 nmol per million cells), but 7-DHC is found at much lower levels (0.1 nmol per million cells). The PTAD method uses a multiple reaction mass spectrometric method that is particularly selective for 7-DHC, making it possible to readily identify library compounds that affect DHCR7 by detecting increases in the levels of 7-DHC. Analysis of 7-DHC in D7-N2a cells provides complimentary information to the screens of compounds in WT-N2a cells. D7-N2a cells have much higher levels of 7-DHC (4 nmol per million cells) than N2a and lower levels of Des (1 nmol per million cells) than the WT cell line (supplemental Fig. S1). A compound that affects any of the transformations that precede the formation of 7-DHC in Chol biosynthesis is detected by a reduction in the levels of 7-DHC present in the D7-N2a cells. Thus, compounds that inhibit HMGCR are readily detected by a decrease in levels of 7-DHC in D7-N2a cells without a compensatory increase in Chol. In a similar way, DHCR24 inhibitors decrease levels of 7-DHC in these cells, as do compounds that affect other transformations between HMGCR and DHCR24.

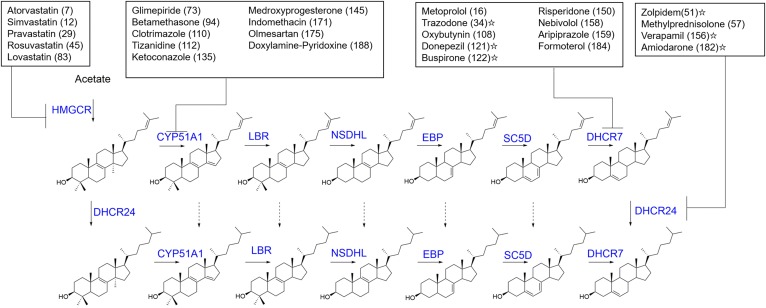

In this study, one in five of the FDA-approved drugs screened was identified to have an impact on Chol biosynthesis in some manner. A number of the lead-hit compounds are well-known, such as the statins, which inhibit HMGCR (37), or azole fungicides (38) that target Cyp51. Additionally, twenty-one of the lead hits identified in this screen, including the antipsychotic, aripiprazole (30), were similarly identified in a screen of a National Institutes of Health clinical collection chemical library (25, 26) with similar Z scores (R2 > 0.95). It is nevertheless of interest that 82 of the drugs that were identified in this study had an effect on levels of Des or 7-DHC that was previously unreported. It is also of interest to put the percentage of hit compounds found in this screen in perspective with drugs that are being routinely prescribed. Utilizing the 2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (39), we conclude that 27 of the top 200 most prescribed drugs affect Chol biosynthesis and, of this set of drugs, 13 target either DHCR7 or DHCR24 (Fig. 4). It should also be noted that a number of the top 200 drugs have yet to be tested for their effect on sterol biosynthesis, including compounds with high abuse potential that are not readily available for screening purposes (39).

Fig. 4.

Common prescription drugs identified as Chol biosynthetic active compounds. Shown are the top 27 prescription drugs determined to inhibit Chol biosynthesis at the indicated enzyme (blue). Next to each drug in parentheses is the rank of drug utilization in the US based on the number of individuals with a purchase of that drug (39). Drugs identified beyond the current screen are indicated with a star from either screening experiments (26) or targeted studies, as in the case of verapamil (54) and amiodarone (55).

The potential risks of elevated levels of 7-DHC

Perturbing DHCR7 activity has been a known human health risk since the 1960s when the DHCR7 inhibitor, AY-9944, was demonstrated to be teratogenic in rodent models (17). Since that time, a number of other chemicals have been identified as DHCR7 inhibitors and, similarly, their use is cautioned and/or altogether discontinued during pregnancy (30). In addition to increased risk of birth defects and perturbed fetal development, there is also the potential for DHCR7 inhibitors to pose increased health risks for adult patients as well. The 7-DHC is one of the most highly oxidizable organic molecules and it accumulates upon administration of a DHCR7 inhibitor (40, 41). The increased level of 7-DHC may not in itself pose immediate toxicity, but it seems likely that 7-DHC could prime a system for a severe insult when an oxidative stress is initiated. The 7-DHC molecules are readily oxidized to form highly reactive oxysterols that have diverse biological activities and that can readily form adducts to proteins (42). In addition to the previously identified DHCR7 inhibitors, such as aripiprazole and haloperidol, this screen identified a number of antidepressants, anesthetics, antiseptics, and β-blockers, as well as many other antipsychotic medications not previously known to affect DHCR7. Of those drugs identified as DHCR7 inhibitors here, the β-blockers, metoprolol and nebivolol, are two of the most heavily prescribed and utilized drugs in the US to treat hypertension (39). Nebivolol is the next generation β-blocker with improved physiological outcomes compared with metoprolol while still maintaining clinical efficacy, with one attributable benefit of Nebivolol being a lower efficacious steady state concentration in the blood of ∼20 nM (43). However, the findings reported herein suggest that more extensive studies of the effects of these drugs on development during pregnancy should be undertaken to understand their potential risk.

Aspects to consider in the regulation of Des levels

Of the 49 compounds identified to potentially impact Des levels, focus was directed toward the TKIs, as many of them elevated Des levels in both the WT- and D7-N2a cell line screens. Of particular interest were the drugs masitinib and ponatinib, as they were shown to be potent modulators of multiple biomolecules associated with DHCR24 beyond Des, including 7-DHD and 24-DHL. The effect of these two TKIs are likely translatable to human populations, as the concentrations utilized in this project for masitinib and ponatinib are similar to their known Cmax values of 51 nM and 145 nM, respectively (44, 45). In contrast, the other TKI utilized in this study, imatinib, may be even more efficacious, as it can be tolerated in humans at blood concentrations in the micromolar range (34). The only other set of compounds that affected Des levels in both cell lines were the progestin steroids (progesterone and pregnenolone), which have previously been reported to affect DHCR24 activity (31), a conclusion that our findings support. However, DHCR24 activity and protein stability have been shown to be posttranslationally regulated by two distinct tyrosine residues (46), and it is possible that these specific residues may be the targets of the TKIs examined in our study.

Future studies with in vivo models seem to be called for because regulating DHCR24 activity may have some therapeutic benefits. In this regard, targeting Des levels as a therapy for neurodegeneration has been proposed, and masitinib is being repurposed as an adjuvant therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (47) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (48–50). Evidence suggests that masitinib is beneficial to patients with mild to moderate AD by normalizing neuronal signaling to support dendritic health (48). Yet, there are many findings that demonstrate that AD patients have perturbed sterol profiles (51) characterized by low Des levels in neuronal tissues (52, 53). This study provides evidence that masitinib is a potent elevator of Des by lowering DHCR24 protein expression levels. These findings suggest that masitinib may, in addition to the already determined pharmacological effects in AD patients, also normalize sterol homeostasis and provide additional physiological benefits in these patients. If this is indeed the case, then it may prove beneficial to identify means to normalize Des levels in all AD patients as adjuvant therapy.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Chol is an essential biological molecule, and when pathologies lead to elevations or reductions of it or one of its precursors, there can be severe health consequences. Thus, it is essential to determine regulatory mechanisms of maintaining sterol homeostasis. This is a prerequisite for evaluating the risk of altering sterols or using pharmacotherapy to normalize levels of sterols. This work has sought to accomplish this goal by identifying a more complete pharmacopeia of Chol biosynthesis disruptors that should prove useful for researchers, translational scientists, and clinicians alike. Additionally, the results of the study provide a chemical tool set to begin exploring the mechanistic involvement of the entire Chol biosynthetic pathway in a number of disorders, including AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Selleck Chemicals Food and Drug Administration-approved library was provided by the Vanderbilt CTSA (National Institutes of Health Grant UL1TR00044) and distributed by the Vanderbilt High-Throughput Screening Core Facility with assistance from Paige Vinson, Joshua Bauer, and Corbin Whitwell. The Vanderbilt High-throughput Screening Core Facility receives support from the Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology and the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AD

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Chol

- cholesterol

- Des

- desmosterol

- DHCR7

- 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase

- DHCR24

- 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase

- DHL

- dehydrolathosterol

- DHLan

- dihydrolanosterol

- D7-N2a

- Dhcr7-deficient Neuro2a cell

- 7-DHD

- 7-dehydrodesmosterol

- 7-DHC

- 7-dehydrocholesterol

- FDA

- Food and Drug Administration

- HMGCR

- HMG-CoA reductase

- Lan

- lanosterol

- N2a

- Neuro2a

- PTAD

- 4-phenyl-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione

- SRM

- selected reaction monitoring

- TKI

- tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- WT-N2a

- Neuro2a cell

- Zym

- zymosterol

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grants ES024133 (N.A.P., Z.K.) and ES000267 (P.A.W.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor F., Huffman M. D., Macedo A. F., Moore T. H. M., Burke M., Davey Smith G., Ward K., and Ebrahim S.. 2013. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1: CD004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling Q., and Tejada-Simon M. V.. 2016. Statins and the brain: new perspective for old drugs. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 66: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarland A. J., Anoopkumar-Dukie S., Arora D. S., Grant G. D., McDermott C. M., Perkins A. V., and Davey A. K.. 2014. Molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of statins in the central nervous system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15: 20607–20637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nes W. D. 2011. Biosynthesis of cholesterol and other sterols. Chem. Rev. 111: 6423–6451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J., and Liu Q.. 2015. Cholesterol metabolism and homeostasis in the brain. Protein Cell. 6: 254–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter F. D., and Herman G. E.. 2011. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 52: 6–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witsch-Baumgartner M., Fitzky B. U., Ogorelkova M., Kraft H. G., Moebius F. F., Glossmann H., Seedorf U., Gillessen-Kaesbach G., Hoffmann G. F., Clayton P., et al. 2000. Mutational spectrum in the Delta7-sterol reductase gene and genotype-phenotype correlation in 84 patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66: 402–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witsch-Baumgartner M., Schwentner I., Gruber M., Benlian P., Bertranpetit J., Bieth E., Chevy F., Clusellas N., Estivill X., Gasparini G., et al. 2008. Age and origin of major Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS) mutations in European populations. J. Med. Genet. 45: 200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterham H. R., and Hennekam R. C. M.. 2012. Mutational spectrum of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 160C: 263–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balogh I., Koczok K., Szabo G. P., Torok O., Hadzsiev K., Csabi G., Balogh L., Dzsudzsak E., Ajzner E., Szabo L., et al. 2012. Mutational spectrum of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome patients in Hungary. Mol. Syndromol. 3: 215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellingson M. S., Wick M. J., White W. M., Raymond K. M., Saenger A. K., Pichurin P. N., Wassif C. A., Porter F. D., and Babovic-Vuksanovic D.. 2014. Pregnancy in an individual with mild Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Clin. Genet. 85: 495–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cross J. L., Iben J., Simpson C. L., Thurm A., Swedo S., Tierney E., Bailey-Wilson J. E., Biesecker L. G., Porter F. D., and Wassif C. A.. 2015. Determination of the allelic frequency in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome by analysis of massively parallel sequencing data sets. Clin. Genet. 87: 570–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaoua W., Wolf C., Chevy F., Ilien F., and Roux C.. 2000. Cholesterol deficit but not accumulation of aberrant sterols is the major cause of the teratogenic activity in the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome animal model. J. Lipid Res. 41: 637–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korade Z., Xu L., Harrison F. E., Ahsen R., Hart S. E., Folkes O. M., Mirnics K., and Porter N. A.. 2014. Antioxidant supplementation ameliorates molecular deficits in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Biol. Psychiatry. 75: 215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L., Korade Z., and Porter N. A.. 2010. Oxysterols from free radical chain oxidation of 7-dehydrocholesterol: product and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132: 2222–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung S., Seo J. S., Kim B. S., Lee D., Jung K. H., Chu K., Lee S. K., and Jeon D.. 2013. Social deficits in the AY-9944 mouse model of atypical absence epilepsy. Behav. Brain Res. 236: 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roux C., Wolf C., Mulliez N., Gaoua W., Cormier V., Chevy F., and Citadelle D.. 2000. Role of cholesterol in embryonic development. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71: 1270S–1279S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohanizadegan M., and Sacharow S.. 2018. Desmosterolosis presenting with multiple congenital anomalies. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 61: 152–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitsche M. A., McDonald J. G., Hobbs H. H., and Cohen J. C.. 2015. Flux analysis of cholesterol biosynthesis in vivo reveals multiple tissue and cell-type specific pathways. eLife. 4: e07999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato Y., Bernier F., Yamanaka Y., Aoshima K., Oda Y., Ingelsson M., Lannfelt L., Miyashita A., Kuwano R., and Ikeuchie T.. 2015. Reduced plasma desmosterol-to-cholesterol ratio and longitudinal cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst.). 1: 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezzikouri S., Kimura K., Sunagozaka H., Kaneko S., Inoue K., Nishimura T., Hishima T., Kohara M., and Tsukiyama-Kohara K.. 2015. Serum DHCR24 auto-antibody as a new biomarker for progression of hepatitis C. EBioMedicine. 2: 604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costello D. A., Villareal V. A., and Yang P. L.. 2016. Desmosterol increases lipid bilayer fluidity during hepatitis C virus infection. ACS Infect. Dis. 2: 852–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muse E. D., Yu S., Edillor C. R., Tao J., Spann N. J., Troutman T. D., Seidman J. S., Henke A., Roland J. T., Ozeki K. A., et al. 2018. Cell-specific discrimination of desmosterol and desmosterol mimetics confers selective regulation of LXR and SREBP in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115: E4680–E4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spann N. J., Garmire L. X., McDonald J. G., Myers D. S., Milne S. B., Shibata N., Reichart D., Fox J. N., Shaked I., Heudobler D., et al. 2012. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 151: 138–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korade Z., Kim H. Y., Tallman K. A., Liu W., Koczok K., Balogh I., Xu L., Mirnics K., and Porter N. A.. 2016. The effect of small molecules on sterol homeostasis: measuring 7-dehydrocholesterol in Dhcr7-deficient Neuro2a cells and human fibroblasts. J. Med. Chem. 59: 1102–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim H. Y., Korade Z., Tallman K. A., Liu W., Weaver C. D., Mirnics K., and Porter N. A.. 2016. Inhibitors of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase: screening of a collection of pharmacologically active compounds in Neuro2a cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29: 892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korade Z., Kenworthy A. K., and Mirnics K.. 2009. Molecular consequences of altered neuronal cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Neurosci. Res. 87: 866–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J. H., Chung T. D., and Oldenburg K. R.. 1999. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 4: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W., Xu L., Lamberson C., Haas D., Korade Z., and Porter N. A.. 2014. A highly sensitive method for analysis of 7-dehydrocholesterol for the study of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 55: 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korade Ž., Liu W., Warren E. B., Armstrong K., Porter N. A., and Konradi C.. 2017. Effect of psychotropic drug treatment on sterol metabolism. Schizophr. Res. 187: 74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindenthal B., Holleran A. L., Aldaghlas T. A., Ruan B., Schroepfer G. J. Jr., Wilson W. K., and Kelleher J. K.. 2001. Progestins block cholesterol synthesis to produce meiosis-activating sterols. FASEB J. 15: 775–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avilés-Vázquez S., Chávez-González A., Hidalgo-Miranda A., Moreno-Lorenzana D., Arriaga-Pizano L., Sandoval-Esquivel M. A., Ayala-Sánchez M., Aguilar R., Alfaro-Ruiz L., and Mayani H.. 2017. Global gene expression profiles of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the effect of in vitro culture with or without imatinib. Cancer Med. 6: 2942–2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandyopadhyay S., Li J., Traer E., Tyner J. W., Zhou A., Oh S. T., and Cheng J. X.. 2017. Cholesterol esterification inhibition and imatinib treatment synergistically inhibit growth of BCR-ABL mutation-independent resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia. PLoS One. 12: e0179558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J., Salminen A., Yang X., Luo Y., Wu Q., White M., Greenhaw J., Ren L., Bryant M., Salminen W., et al. 2017. Effects of 31 FDA approved small-molecule kinase inhibitors on isolated rat liver mitochondria. Arch. Toxicol. 91: 2921–2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald J. G., Smith D. D., Stiles A. R., and Russell D. W.. 2012. A comprehensive method for extraction and quantitative analysis of sterols and secosteroids from human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 53: 1399–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffiths W. J., and Wang Y.. 2009. Sterol lipidomics in health and disease: methodologies and applications. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 1: 14–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharpe L. J., and Brown A. J.. 2013. Controlling cholesterol synthesis beyond 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR). J. Biol. Chem. 288: 18707–18715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heeres J., Meerpoel L., and Lewi P.. 2010. Conazoles. Molecules. 15: 4129–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Accessed April 7, 2018, at https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu L., Liu W., Sheflin L. G., Fliesler S. J., and Porter N. A.. 2011. Novel oxysterols observed in tissues and fluids of AY9944-treated rats: a model for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 52: 1810–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu L., Davis T. A., and Porter N. A.. 2009. Rate constants for peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and sterols in solution and in liposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131: 13037–13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tallman K. A., Kim H. H., Korade Z., Genaro-Mattos T. C., Wages P. A., Liu W., and Porter N. A.. 2017. Probes for protein adduction in cholesterol biosynthesis disorders: alkynyl lanosterol as a viable sterol precursor. Redox Biol. 12: 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velasco A., Solow E., Price A., Wang Z., Arbique D., Arbique G., Adams-Huet B., Schwedhelm E., Lindner J. R., and Vongpatanasin W.. 2016. Differential effects of nebivolol vs. metoprolol on microvascular function in hypertensive humans. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 311: H118–H124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soria J. C., Massard C., Magne N., Bader T., Mansfield C. D., Blay J. Y., Bui B. N., Moussy A., Hermine O., and Armand J. P.. 2009. Phase 1 dose-escalation study of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor masitinib in advanced and/or metastatic solid cancers. Eur. J. Cancer. 45: 2333–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye Y. E., Woodward C. N., and Narasimhan N. I.. 2017. Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of [(14)C]ponatinib after a single oral dose in humans. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 79: 507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luu W., Zerenturk E. J., Kristiana I., Bucknall M. P., Sharpe L. J., and Brown A. J.. 2014. Signaling regulates activity of DHCR24, the final enzyme in cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 55: 410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petrov D., Mansfield C., Moussy A., and Hermine O.. 2017. ALS clinical trials review: 20 years of failure. Are we any closer to registering a new treatment? Front. Aging Neurosci. 9: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Folch J., Petrov D., Ettcheto M., Abad S., Sanchez-Lopez E., Garcia M. L., Olloquequi J., Beas-Zarate C., Auladell C., and Camins A.. 2016. Current research therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Neural Plast. 2016: 8501693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Folch J., Petrov D., Ettcheto M., Pedros I., Abad S., Beas-Zarate C., Lazarowski A., Marin M., Olloquequi J., Auladell C., et al. 2015. Masitinib for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 15: 587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piette F., Belmin J., Vincent H., Schmidt N., Pariel S., Verny M., Marquis C., Mely J., Hugonot-Diener L., Kinet J. P., et al. 2011. Masitinib as an adjunct therapy for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 3: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Popp J., Meichsner S., Kolsch H., Lewczuk P., Maier W., Kornhuber J., Jessen F., and Lutjohann D.. 2013. Cerebral and extracerebral cholesterol metabolism and CSF markers of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 86: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wisniewski T., Newman K., and Javitt N. B.. 2013. Alzheimer’s disease: brain desmosterol levels. J. Alzheimers Dis. 33: 881–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kölsch H., Heun R., Jessen F., Popp J., Hentschel F., Maier W., and Lütjohann D.. 2010. Alterations of cholesterol precursor levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1801: 945–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Field F. J., Born E., Murthy S., and Mathur S. N.. 1998. Transport of cholesterol from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane is constitutive in CaCo-2 cells and differs from the transport of plasma membrane cholesterol to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Lipid Res. 39: 333–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simonen P., Lehtonen J., Lampi A. M., Piironen V., Stenman U. H., Kupari M., and Gylling H.. 2018. Desmosterol accumulation in users of amiodarone. J. Intern. Med. 283: 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.