Structured Abstract

Background

Atrial arrhythmias, particularly atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, can coexist with drug-induced type 1 Brugada ECG pattern (DI-Type1-BrP). The present study was designed to determine the prevalence of DI-Type1-BrP in patients with atrioventricular accessory pathways (AV-APs) and to investigate the clinical, electrocardiographic, electrophysiologic and genetic characteristics of these patients.

Methods

One-hundred-twenty-four consecutive cases of AV-APs and 84 controls underwent an ajmaline challenge test to unmask DI-Type1-BrP. Genetic screening and analysis was performed in 55 of the cases (19 with and 36 without DI-Type1-BrP).

Results

Patients with AV-APs were significantly more likely than controls to have a Type1-BrP unmasked (16.1 versus 4.8%, p=0.012). At baseline, patients with DI-Type1-BrP had higher prevalence of chest pain, QR/rSr′ pattern in V1 and QRS notching/slurring in V2 and aVL during pre-excitation, rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 and QRS notching/slurring in aVL during orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) compared to patients without DI-Type1-BrP. Abnormal QRS configuration (QRS notching/slurring and/or fragmentation) in V2 during pre-excitation was present in all patients with DI-Type1 BrP. The prevalence of spontaneous pre-excited atrial fibrillation (AF) and history of AF were similar (15% versus 18.3%, p=0.726) in patients with and without DI-Type1-BrP, respectively. The prevalence of mutations in Brugada-susceptibility genes was higher (36.8% versus 8.3%, p=0.02) in patients with DI-Type1-BrP compared to patients without DI-Type1-BrP.

Conclusions

DI-Type1-BrP is relatively common in patients with AV-APs. We identify 12-lead ECG characteristics during pre-excitation and orthodromic AVRT that point to an underlying type1-BrP, portending an increased probability for development of malignant arrhythmias.

Keywords: Brugada Syndrome, Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, Pre-excitation, Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia, Genetics

Introduction

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited cardiac arrhythmia syndrome characterized by a distinct ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads in the absence of structural heart disease.1 Type-1 (“coved type”) ST-segment elevation is considered diagnostic of BrS and it is present either spontaneously or induced by fever or by sodium channel blockers.2

Drug-induced type 1 Brugada ECG pattern (DI-Type 1 BrP) has been shown to be associated with atrial arrhythmias, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) in particular.3 Patients diagnosed with BrS show a higher prevalence of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), including Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome and concealed atrioventricular accessory pathways (AV-APs) with spontaneous atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), compared to general population (1.7% versus ~0.09%).4–6 In view of this association, we hypothesized that a BrP phenotype may be more easily unmasked in patients with AV-APs. The present study was designed to determine the prevalence of DI-Type 1 BrP in patients with AV-APs and to investigate the clinical, electrocardiographic, electrophysiologic and genetic characteristics of these patients.

Methods

Study Populations

One hundred twenty-four consecutive patients (50 women/74 men; mean age 36.4±12.6 years; range 18 to 75) with AV-APs who underwent electrophysiologic study and catheter ablation between November 2011 and July 2017 formed the patient population and their characteristics were compared with a control group (n=84, 42 women/42 men; mean age 39±11.3 years; range 18 to 63). All patients and control subjects underwent an ajmaline challenge test. All study subjects were of Turkish (Anatolian Caucasian) descent. Study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Ege University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for ajmaline challenge test and genetic testing.

Data Acquisition

A detailed medical history including age of onset of AVRT and/or pre-excited atrial fibrillation (AF), age at time of coincidentally detected pre-excitation, associated symptoms (palpitation, chest pain, syncope, and cardiac arrest), presence of systemic diseases (systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, migraine headaches) was obtained in all patients. Syncope was classified as reflex (vasovagal or situational), orthostatic hypotension, arrhythmia-related cardiac syncope, and unexplained syncope. The diagnosis of migraine headache was based on the international classification of headache disorders-II criteria.7

Presence of additional atrial (pre-excited AF, AVNRT, focal atrial tachycardia) and ventricular arrhythmias (frequent [>10/hour], monomorphic premature ventricular contractions and/or ventricular tachycardia), family history of WPW syndrome, WPW “pattern” and AVRT (documented in ≥2 family members) and sudden unexpected death (≤50 years of age) in the first degree relatives was obtained in all patients. Patients with spontaneous and clinical pre-excited AF and AF with concealed AV-APs are considered to have history of AF.

All study subjects underwent transthoracic echocardiography for evaluation of valves, right and left ventricular size and function.

Definition of Electrocardiographic Parameters

WPW syndrome was defined as ventricular pre-excitation in the presence of spontaneous and/or inducible AVRT or spontaneous pre-excited AF.8 WPW “pattern” was defined as coincidentally detected ventricular pre-excitation. Concealed AV-AP was defined as an accessory pathway which conducts only in retrograde direction resulting in normal QRS complex during sinus rhythm.8

Prior to catheter ablation, all patients had a baseline 12-lead ECG analysis for measurements of heart rate, PR interval, QRS duration, frontal plane QRS axis. All available, prior 12-lead ECGs from patients with pre-excitation were analyzed for QRS fragmentation and early repolarization patterns (notching/slurring) in the inferior, lateral and right precordial (V1–V2) leads, QRS fragmentation in V2, QR/rSr′ pattern in V1 with and without ST-segment elevation (≥ 0.05 mV), and QRS notching/slurring (≥ 0.1 mV) in lead aVL.

After successful catheter ablation, all patients had a 12-lead ECG with leads in the standard lead position and a high precordial lead ECG with V1 and V2 moved up to the third and second intercostal space.2 Twelve-lead ECGs were checked for the presence of type 1, 2 and 3 BrP, QRS fragmentation and early repolarization patterns in the inferior and lateral leads. Type 1 BrP, QRS fragmentation, and early repolarization patterns were defined according to previously described criteria.2,9,10

Every patient had a 12-lead ECG during their index clinical arrhythmia. Twelve-lead ECGs during orthodromic AVRTs were analyzed for the rate of AVRT, the timing of the P-wave with respect to QRS complex, presence of aberrancy and QRS alternans, rSr′ pattern in V1-V2, and QRS notching/slurring (≥ 0.1 mV) in lead aVL.8

Electrophysiologic Study and Catheter ablation

All patients underwent electrophysiologic study and catheter ablation for AV-APs. The diagnosis of AVRT was made based on previously described criteria.8 Baseline AH and HV intervals during pre-excitation, antegrade and retrograde AV-AP effective refractory periods, 1:1 AV-AP antegrade conduction, direction of conduction of AV-APs, presence of multiple AV-APs, rate of AVRT and post-ablation AH and HV intervals were determined in each patient. Location of AV-APs were determined based on previously described criteria.11 Radiofrequency energy was used as the energy source in all patients.

Definition of Drug-Induced Type 1 Brugada ECG Pattern and Brugada Syndrome

Type 1 BrP in at least one right precordial lead during ajmaline challenge test was defined as DI-Type 1 BrP.2 BrS was defined according to the J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report.2

Definition of Control Group

The control group is an extension of our previously described control group (n=66) with 18 additional enrolled subjects.3 The control group consisted of unrelated subjects with structurally normal hearts and no history of any type of atrial arrhythmia including AVRT, AVNRT, or any form of ventricular arrhythmia.

Ajmaline Challenge Test

Ajmaline (Gilurytmal®, CARINOPHARM GmbH, Germany) challenge test was performed according to the J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report.2 Ajmaline was administered as continuous intravenous infusion at a rate of 1 mg/kg bodyweight over 5 minutes. Criteria for discontinuation of ajmaline infusion were the development of diagnostic type 1 BrP, ventricular arrhythmias or QRS widening to ≥130% of baseline. Patients with AV-APs underwent ajmaline challenge the following day after the electrophysiologic study and catheter ablation. All tests were performed by the same investigator in the same center using the same equipment with the same standard settings. Twelve-lead ECG recordings were performed by a standard electrocardiograph (ECG-9132K, Nihon Kohden Corporation, Nakano-Ku, TKY, Japan) with standard settings (paper speed of 25 mm/s and a gain setting of 10mm/mV) and summary report (showing median P-QRS-T complexes for each lead) in all subjects. PR and corrected QT intervals, QRS duration and QRS axis were automatically analyzed, and P-wave duration was measured manually in lead II at baseline and after ajmaline challenge.

Genetic Screening and In Silico Functional Prediction of Variants

Genetic screening and analysis was performed in 55 patients (24 women/31 men; mean age 37±13 years): 19 with DI-Type 1 BrP and 36 without DI-Type 1 BrP. A total of 33 genes for BrS (ABCC9, CACNA1C, CACNA2D1, CACNB2, CAV3, FGF12 [FHAF1], GPD1L, HCN4, HEY2, KCNB2, KCND3, KCNE1-5, KCNH2, KCNJ8, KCNJ16, KCNT1, PKP2, RANGRF [encodes MOG1], SCN1B-3B, SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN9A, SCN10A, SCNN1A, SEMA3A, SLMAP, TRPM4) were screened and analyzed by target gene in-depth sequencing by using the Agilent SureSelect Target Enrichment Kit (Agilent Genomics, Santa Barbara, California, USA) and the Illumina Hi-Seq 4000 machine. The identified variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. We compared the allele frequency of each identified variant in public databases including 1000G, gnomAD version 2.0.2 and NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Functional prediction with three well-known bioinformatics algorithms were used to assess the potential functional impacts of identified mutations, including Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT), Protein Variation Effect Analyzer (Provean), and Polymorphism Phenotyping-2 (PolyPhen-2). A variant was defined as a pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation according to the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACGM) Standards and Guidelines.12

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as range and mean ± SD. Differences between means were tested by t test, or Mann-Whitney test, where appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for the relationship of two numeric data. P < 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Prevalence of Drug-Induced Type 1 Brugada ECG Pattern and Patient Characteristics

DI-Type 1 BrP was detected in 20 out of 124 (16.1%) patients with AV-APs, and in 4 out of 84 control subjects (4.8%) (odds ratio 3.84; 95% confidence interval 1.265–11.698; p=0.012).

The patient population was matched to the control group in terms of age (36.4±12.6 years versus 39±11.3 years, p=0.133), male gender (59.7% versus 50%, p=0.168), and left ventricular ejection fraction (62.8±4.6% versus 64.5±3.9%, p=0.061). The patient population presented with a higher prevalence of palpitations (89.5% versus 8.3%, p=<0.001) and migraine headaches (31.5% versus 19%, p=0.047) compared to the control group. The prevalence of chest pain (12.9% versus 13.1%, p=0.968) and syncope (15.3% versus 15.5%, p=0.976) were similar between the patient population and the control group.

Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP had higher prevalence of chest pain (35% versus 8.7%, p=0.001) and tendency to have higher prevalence of migraine headaches (50% versus 27.9%, p=0.051) compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Mean age (39.1±13.8 years versus 35.9±12.4 years, p=0.304), mean age of diagnosis of palpitation/AVRT/pre-excited AF (27±13.3 years versus 25.7±11.3 years, p=0.678), male gender (55% versus 60.6%, p=0.641), prevalence of palpitations (85% versus 90.4%, p=0.472), prevalence of syncope (25% versus 13.5%, p=0.190), presence of systemic hypertension (5% versus 4.8%, p=0.971), presence of diabetes mellitus (none versus 6.7%, p=0.232), and mean left ventricular ejection fraction (64.4±4.8% versus 62.4±4.5%, p=0.114) were similar between patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP, respectively. Structural heart disease was present in 1 (rheumatic heart disease) and 4 patients (mitral valve prolapse [n=1], bicuspid aortic valve [n=1], left ventricular systolic dysfunction due to Wegener’s granulomatosis [n=1], and secundum type ASD [n=1]) with and without DI-Type 1 BrP, respectively. None of the patients had ST-T wave changes during their chest pain episodes. None of the patients had history of suspected arrhythmic syncope, unexplained syncope or cardiac arrest. None of the patients with DI-Type 1 BrP pattern underwent defibrillator implantation.

Baseline 12-lead ECG and Electrophysiologic Characteristics

All patients were in normal sinus rhythm. Clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics of patients with DI-Type 1 BrP are presented in Table 1. A comparison of baseline 12-lead ECG characteristics during pre-excitation and AV-AP characteristics in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP is presented in Table 2. The median number of available 12-lead ECGs displaying pre-excitation per patient were 3 (interquartile range, 1–9) and 2 (interquartile range, 1–6) (p=0.103) in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP, respectively. Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP had higher prevalence of QR/rSr′ pattern in V1 with (56.2% versus 13.7%, p=0.001 – odds ratio 8.1; 95% confidence interval 2.459–26.677) and with or without (68.8% versus 37%, p=0.020 – odds ratio 3.74; 95% confidence interval 1.176–11.944) ST-segment elevation, QRS notching/slurring in V2 (75% versus 37%, p=0.006) and QRS notching/slurring in lead aVL (81.2% versus 50.7%, p=0.026) compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Combination of QRS fragmentation, notching or slurring in V2 was more prevalent (100% versus 57.5%, p=0.001) in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP had higher prevalence (31.2% versus 10.9%, p=0.037) of rSr′ in V1 after successful catheter ablation compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. After ablation, the prevalence of QRS notching/slurring in V2 (25% versus 11%, p=0.136) was no different in patients with or without DI-Type 1 BrP but QRS notching/slurring in lead aVL was more prevalent (68.8% versus 34.2%, p=0.011) in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Representative examples of the diagnostic, baseline 12-lead ECG characteristics during pre-excitation and after successful catheter ablation in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP are illustrated in Figure 1. The dynamic nature of the degree of QRS notching/slurring in V2 and aVL is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Clinical and Electrophysiologic Characteristics of Patients with Drug-Induced Type 1 Brugada Pattern

| Patient Number | Age | Age of Onset of Palpitation/AVRT/AF | Sex | Chest Pain | Syncope | Migraine Headache | Variants of Ventricular Pre-excitation | Type of Arrhythmia | Location of Accessory Pathway(s) | Spontaneous AVRT Cycle Length (ms) | Associated Arrhythmias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 | 8 | M | Yes | Yes | No | WPW syndrome | Pre-excited AF | Left Posteroseptal | - | None |

| 2 | 75 | - | M | Yes | Yes | No | WPW “pattern” | None | Left Posteroseptal | - | PVCs |

| 3 | 37 | 15 | M | No | No | Yes | Concealed AP | O-AVRT | Left Lateral | 295 | None |

| 4 | 41 | 30 | F | No | No | No | Concealed AP | O-AVRT | Left Anterolateral | 325 | AF |

| 5 | 40 | 30 | M | Yes | No | No | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Left Posteroseptal | 340 | None |

| 6 | 24 | - | F | No | No | Yes | WPW “pattern” | None | Left Posteroseptal | - | None |

| 7 | 40 | - | M | No | No | No | WPW “pattern” | None | Right Anteroseptal | - | PVCs |

| 8 | 28 | 27 | M | No | No | Yes | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Right Anterior | 420 | None |

| 9 | 35 | - | M | No | No | No | WPW “pattern” | None | Left Posterolateral | - | None |

| 10 | 42 | 32 | F | No | No | Yes | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Left Posterolateral | 370 | None |

| 11 | 42 | 12 | M | No | No | No | Concealed AP | O-AVRT | Left Posterolateral | 270 | AF |

| 12 | 19 | 15 | F | Yes | No | No | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Right Anteroseptal | 330 | None |

| 13 | 27 | 20 | F | No | No | No | Concealed AP | O-AVRT | Left Lateral | 310 | None |

| 14 | 39 | 29 | M | No | Yes | Yes | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Left Posterior | 320 | None |

| 15 | 54 | - | M | Yes | No | Yes | WPW “pattern” | None | Right Posterior | - | None |

| 16 | 53 | - | F | Yes | No | Yes | WPW “pattern” | None | Left Posteroseptal | - | PVCs |

| 17 | 28 | 28 | M | No | Yes | No | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Left Posterolateral Left Lateral |

310 | None |

| 18 | 60 | 45 | F | No | No | Yes | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Left Posterolateral | 330 | None |

| 19 | 22 | 9 | F | No | No | Yes | WPW syndrome | O-AVRT | Right Anterolateral | 290 | None |

| 20 | 30 | - | F | Yes | Yes | Yes | WPW “pattern” | None | Right Posteroseptal | - | None |

AF = Atrial Fibrillation, AP = Accessory Pathway, AVRT = Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia, O-AVRT = Orthodromic Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia, PVC = Premature Ventricular Contraction, WPW = Wolff-Parkinson-White.

Table 2.

Comparison of Electrocardiographic and Electrophysiologic Characteristics of Patients with and without Drug-Induced Type 1 Brugada ECG Pattern at Baseline and during Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia

| Variable | Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP (n=20) | Patients without DI-Type 1 BrP (n=104) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline 12-lead ECG Characteristics during Pre-excitation | |||

| - Heart Rate (bpm): | 68±13 | 72.8±11.4 | 0.153 |

| - PR Interval (ms): | 115.4±10.9 | 118.9±12.9 | 0.348 |

| - QRS Duration (ms): | 130.6±12.8 | 122.9±17 | 0.107 |

| - QRS Axis (°): | 27 (Median-/Range -58 to 63) | 18 (Median-/Range -68 to 118) | 0.516 |

| - QRS fragmentation in inferior leads (%): | 62.5 | 53.4 | 0.509 |

| - QRS fragmentation in lateral leads (%): | 12.5 | 13.7 | 0.899 |

| - QRS fragmentation in V2 (%): | 31.2 | 30.1 | 0.930 |

| - QRS notching/slurring in inferior leads (%): | 0 | 11 | 0.165 |

| - QRS notching/slurring in lateral leads (%): | 37.5 | 52.1 | 0.292 |

| - QRS notching/slurring in aVL (%): | 81.2 | 50.7 | 0.026 |

| - QRS notching/slurring in V2 (%): | 75 | 37 | 0.006 |

| - QRS fragmentation/notching/slurring in V2 (%): | 100 | 57.5 | 0.001 |

| - QR/rSr′ pattern in V1 with or without ST-segment elevation (%): | 68.8 | 37 | 0.020 |

| - QR/rSr′ pattern in V1 with ST-segment elevation (%): | 56.2 | 13.7 | 0.001 |

| Baseline Electrophysiology/Accessory Pathway Characteristics | |||

| - Baseline AHHis Interval (ms) during pre-excitation: | 56.8±22 | 60.1±17.3 | 0.581 |

| - Baseline HVHis Interval (ms) during pre-excitation: | 11±12.6 | 9.4±19.7 | 0.794 |

| - Post-ablation AHHis interval (ms): | 56.5 (Median-/Range 45 to 96) | 63.5 (Median-/Range 38 to 115) | 0.414 |

| - Post-ablation HVHis interval (ms): | 41.1±4.9 | 41.5±7 | 0.888 |

| - 1:1 Accessory Pathway antegrade conduction (ms): | 340 (Median-/Range 240 to 650) | 340 (Median-/Range 270 to 650) | 0.682 |

| - Antegrade Accessory Pathway ERP (ms): | 290 (Median-/Range 210 to 290) | 280 (Median-/Range 200 to 450) | 0.756 |

| - Retrograde Accessory Pathway ERP (ms): | 325±26.6 | 303±30.4 | 0.141 |

| - Variants of Ventricular Pre-exciation: | |||

| - Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (%): | 9 (45) | 57 (54.8) | 0.467 |

| - Wolff-Parkinson-White “pattern” (%): | 7 (35) | 23 (22.1) | NS |

| - Concealed Accessory Pathway (%): | 4 (20) | 24 (23.1) | NS |

| - Atriofascicular (Mahaim) Accessory Pathway (%): | 0 | 4 (3.8) | NS |

| - PJRT (%): | 0 | 1 (0.9) | NS |

| - Fasciculoventricular Accessory Pathway (%): | 4 (20) | 8 (7.7) | 0.088 |

| - Location of Accessory Pathways: | |||

| - Left Free Wall (%): | 9 (45) | 59 (56.7) | 0.451 |

| - Posteroseptal (%): | 6 (30) | 26 (25) | NS |

| - Anteroseptal/Right Anterior Paraseptal/Midseptal (%): | 2 (10) | 13 (12.5) | NS |

| - Right Free Wall (%): | 3 (15) | 6 (5.8) | NS |

| - Direction of Conduction of Accessory Pathways: | |||

| - Antegrade and Retrograde (%): | 9 (45) | 61 (58.7) | 0.194 |

| - Antegrade Only (%): | 7 (35) | 18 (17.3) | NS |

| - Retrograde Only (%): | 4 (20) | 25 (24) | NS |

| - Multiple Accessory Pathways (%): | 1 (5) | 7 (6.7) | 0.773 |

| - Familial Accessory Pathway (%): | 1 (5) | 4 (3.8) | 0.810 |

| AVRT Characteristics | |||

| - Antidromic AVRT (%): | 0 | 1 (0.9) | NS |

| - Orthodromic AVRT (%): | 12 (60) | 71 (68.2) | NS |

| - Spontaneous orthodromic AVRT Rate (cycle length/ms): | 315±27.2 | 301±33.7 | 0.245 |

| - Presence of Aberrancy (%): | 16.7 | 12.7 | 0.706 |

| - Presence of QRS Alternans (%): | 8.3 | 19.2 | 0.361 |

| - rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 during orthodromic AVRT (%): | 90 | 23.9 | <0.001 |

| - Notching/slurring in aVL during orthodromic AVRT (%): | 90 | 20.9 | <0.001 |

| Coexisting Atrial and Ventricular Arrhythmias | |||

| - Spontaneous, Clinical Pre-excited Atrial Fibrillation (%): | 1 (5) | 15 (14.4) | 0.250 |

| - History of Atrial Fibrillation (%): | 3 (15) | 19 (18.3) | 0.726 |

| - Spontaneous/Inducible AVNRT (%): | 0 | 5 (4.8) | 0.317 |

| - Ventricular Arrhythmias (PVC and/or VT) (%): | 3 (15) | 9 (8.7) | 0.379 |

Data are given as mean ± SD, number of patients and percentages. P < 0.05 considered to be significant. AVNRT = Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia, AVRT = Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia, ERP = Effective Refractory Period, PJRT = Permanent form of Junctional Reciprocating Tachycardia, PVC = Premature Ventricular Contraction, VT = Ventricular Tachycardia.

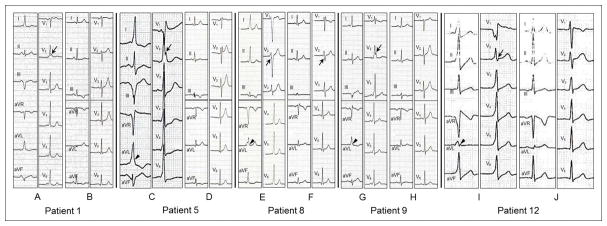

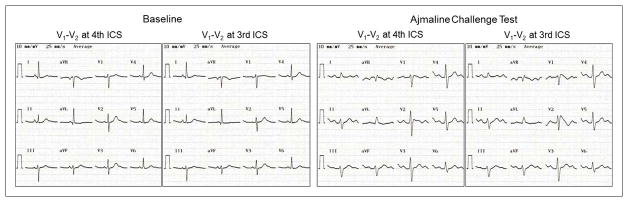

Figure 1.

Twelve-lead electrocardiograms during pre-excitation (A/C/E/G/I) and after catheter ablation (B/D/F/H/J) of five patients (Patients 1, 5, 8, 9 and 12 in Table 1) with drug-induced type 1 Brugada pattern. Patient 1 with a left posteroseptal accessory pathway had rSr′ pattern with ST-segment elevation (0.062 mV) in V1 and QRS notching in V2 (arrow) during pre-excitation (A) and type 3 Brugada pattern in V2 after catheter ablation (B). Patient 5 with a left posteroseptal accessory pathway had rSr′ pattern with ST-segment elevation (0.085 mV) in V1, QRS notching in V2 (arrow) and QRS slurring in lead aVL (arrow head) during pre-excitation (C) and rSr′ pattern with ST-segment elevation in V1 and V2 after catheter ablation (D). Patient 8 with a right anterior accessory pathway had QRS fragmentation in V2 (arrow) and QRS slurring in lead aVL (arrow head) during pre-excitation (E) and QRS fragmentation in V2 (arrow) after catheter ablation (F). Patient 9 with a left posterolateral accessory pathway had rSr′ pattern without ST-segment elevation in V1, QRS notching in V2 (arrow) and QRS slurring in lead aVL (arrow head) during pre-excitation (G) and unremarkable QRS pattern in V1 and V2 after catheter ablation (H). Patient 12 with a right anteroseptal accessory pathway had QR pattern with ST-segment elevation (0.156 mV) in V1, QRS notching in V2 (arrow) and in lead aVL (arrow head) during pre-excitation (I) and type 3 Brugada pattern in V1 and V2 after catheter ablation (J). All electrocardiograms were recorded at a paper speed of 25 mm/s and a gain setting of 10mm/mV.

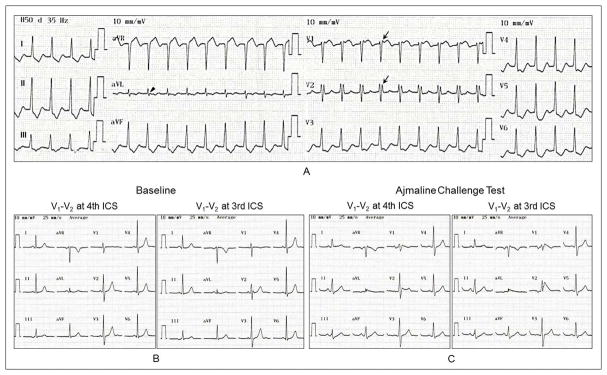

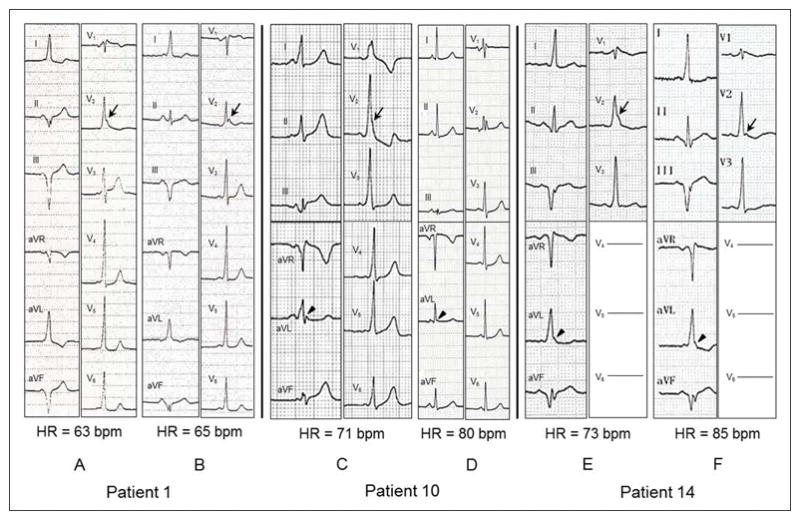

Figure 2.

Dynamic nature of QRS notching and slurring during pre-excitation in leads V2 and aVL in three patients (Patients 1, 10 and 14 in Table 1) with drug-induced type 1 Brugada pattern. Patient 1 with a left posteroseptal accessory pathway had accentuated QRS notching in V2 (arrow) with more pronounced pre-excitation (A) compared to attenuated QRS notching in V2 (arrow) with lesser degree of pre-excitation (B) with similar heart rates. Patient 10 with a left posterolateral accessory pathway had accentuated QRS slurring/notching in V2 (arrow) and aVL (arrow head) with more pronounced pre-excitation (C) compared to disapperance of QRS slurring in V2 and attenuated QRS slurring in aVL (arrow head) with lesser degree of pre-excitation and faster heart rate (D). Patient 14 with a left posterior accessory pathway had accentuated QRS slurring in V2 (arrow) and aVL (arrow head) with slower heart rate (E) compared to attenuated QRS slurring/notching in V2 and unchanged QRS slurring in aVL (arrow head) with faster heart rate and similar degree of pre-excitation (F). All electrocardiograms were recorded at a paper speed of 25 mm/s and a gain setting of 10mm/mV. HR = Heart Rate.

The prevalence of spontaneous and clinical pre-excited AF (5% versus 14.4%, p=0.250) and history of AF (15% versus 18.3%, p=0.726) prior to catheter ablation were similar in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP (Table 2).

None of the patients in the study population had spontaneous type 1 BrP on baseline, standard 12-lead ECGs during pre-excitation or after successful catheter ablation. The prevalence of type 2 or 3 BrP after successful catheter ablation (20% versus 8.8%, p=0.139) was not different in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP, respectively. None of the patients in the study population developed ventricular fibrillation (VF) during catheter ablation of the accessory pathway.

Twelve-lead ECG Characteristics during Orthodromic AVRT

A comparison of 12-lead ECG characteristics during orthodromic AVRT in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP is presented in Table 2. Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP had higher prevalence of rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 (90% versus 23.9%, p=<0.001 – odds ratio 28.6; 95% confidence interval 3.372–244.06) and QRS notching/slurring in lead aVL (90% versus 20.9%, p=<0.001) during orthodromic AVRT compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Among those patients, the prevalence of rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 (44% versus 56%, p=NS) and QRS notching/slurring in lead aVL (67% versus 71%, p=NS) after catheter ablation was similar in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP, respectively. Representative examples of the diagnostic 12-lead ECG characteristics during orthodromic AVRT and the ajmaline challenge test in 2 patients with DI-Type 1 BrP are illustrated in Figures 3 and 4.

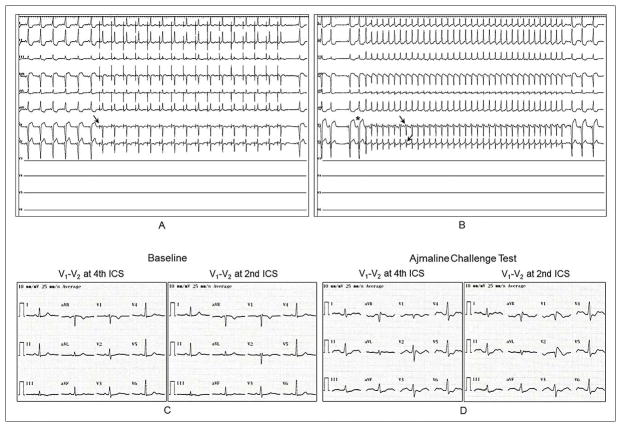

Figure 3.

Twelve-lead electrocardiograms during orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (O-AVRT)(A), at baseline (B) and after ajmaline challenge test (C). Patient was a 42-year-old female who presented with a 10-year history of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (Patient 10 in Table 1). She had structurally normal heart. She had rSr′ pattern in V1 and V2 (arrow) with ST-segment elevation in V1 (0.094 mV) and QRS notching in lead aVL (arrow head) during O-AVRT with a rate of 370 ms. Electrophysiologic study revealed a left posterolateral accessory pathway conducting in antegrade and retrograde directions, inducible O-AVRT and a fasciculoventricular accessory pathway. She underwent successful accessory pathway ablation. Genetic analysis revealed an insertion mutation in SCN4A. Ajmaline challenge test resulted in prolongation of PR interval (156 ms), QRS duration (126 ms) with nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay, QRS axis of 41°, and type 1 Brugada pattern in V1 and V2.

Figure 4.

Twelve-lead electrocardiograms during sinus rhythm with pre-excitation and coronary sinus pacing (A), during orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (O-AVRT)(B), at baseline (C) and after ajmaline challenge test (D). Patient was a 22-year-old female who presented with a 13-year history of palpitations (Patient 19 in Table 1). She had structurally normal heart. Coronary sinus pacing with a rate of 650 ms resulted in loss of her pre-excitation (arrow) with rS waves in V1 and V2 (A). Right after stopping coronary sinus pacing, a catheter-induced premature atrial contraction (asterisk) initiated O-AVRT (rate of 290 ms) with rSr′ pattern in V1 and V2 (arrows) without ST-segment elevation (B). Electrophysiologic study revealed a right anterolateral accessory pathway conducting in antegrade and retrograde directions. She underwent successful accessory pathway ablation. Genetic analysis did not reveal any mutation in screened Brugada-susceptibility genes. Ajmaline challenge test resulted in prolongation of PR interval (235 ms), QRS duration (130 ms) with nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay, QRS axis of 50°, and type 1 Brugada pattern in V1 and V2. Lead V3 through V6 were not recorded during electrophysiologic study because of placement of a cardioversion patch in that region.

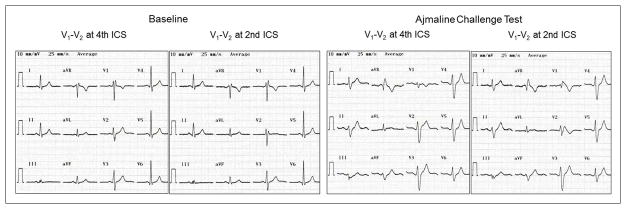

Ajmaline Challenge Test Characteristics

Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP had more pronounced PR interval prolongation (54.5±23.1 versus 44.2±14.5 and 41.4±14.1 ms, p=0.005), wider QRS duration (125.9±15 versus 119.8±13.4 and 117.4±11.5 ms, p=0.032) and more pronounced QTc interval prolongation (452.9±17.5 versus 437.5±19.4 and 437±17.7 ms, p=0.003) with ajmaline compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP and control subjects. Prevalence and type of conduction disturbances with ajmaline were similar in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP and control subjects. Representative examples of 12-lead ECG characteristics at baseline and after the ajmaline challenge test in 2 genotype-positive and 1 genotype-negative patients are illustrated in Figures 5, 6 and 7.

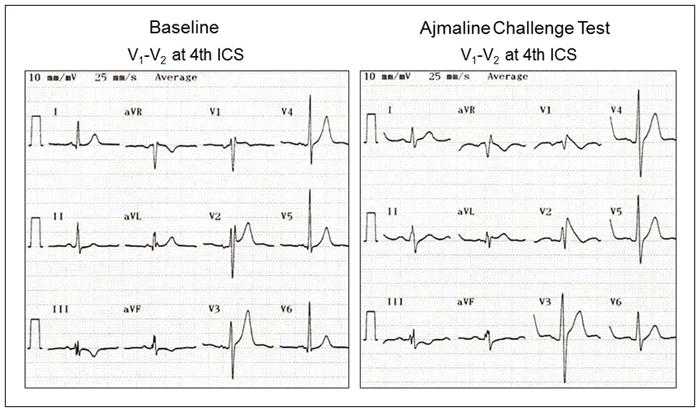

Figure 5.

Twelve-lead electrocardiograms at baseline and after ajmaline challenge test. Patient was a 40-year-old male who presented with a 10-year history of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (Patient 5 in Table 1). He had mild mitral stenosis and mitral regurgitation due to rheumatic heart disease with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Electrophysiologic study revealed a left posteroseptal accessory pathway conducting in antegrade and retrograde directions and inducible orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia. He underwent successful accessory pathway ablation. Genetic analysis revealed a missense mutation in SCN5A (p.Val1597Met). Ajmaline challenge test resulted in prolongation of PR interval (180 ms), QRS duration (130 ms) with right bundle branch block, QRS axis of −15°, and type 1 Brugada pattern in V2.

Figure 6.

Twelve-lead electrocardiograms at baseline and after ajmaline challenge test. Patient was a 28-year-old male who presented with a 1-year history of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (Patient 8 in Table 1). He had mild left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 51% prior to catheter ablation. Electrophysiologic study revealed a right anterior accessory pathway conducting in antegrade and retrograde directions and inducible orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia. He underwent successful accessory pathway ablation. His left ventricular ejection fraction improved to 58% within 6 months of catheter ablation. Genetic analysis revealed a missense mutation in KCND3 (p.Arg549His). Ajmaline challenge test resulted in prolongation of PR interval (168 ms), QRS duration (178 ms) with right bundle branch block and left anterior fascicular block, QTc interval (479 ms), QRS axis of −68°, and type 1 Brugada pattern in V1 and V2.

Figure 7.

Twelve-lead electrocardiograms at baseline and after ajmaline challenge test. Patient was a 60-year-old female who presented with a 15-year history of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (Patient 18 in Table 1). She had history of breast cancer and underwent surgery and radiotherapy. She had mild mitral regurgitation with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Electrophysiologic study revealed a left posterolateral accessory pathway conducting in antegrade and retrograde directions and inducible orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia. She underwent successful accessory pathway ablation. Genetic analysis did not reveal any mutation in screened Brugada-susceptibility genes. Ajmaline challenge test resulted in prolongation of PR interval (224 ms), QRS duration (132 ms) with left anterior fascicular block, QTc interval (464 ms), QRS axis of −45°, and type 1 Brugada pattern in V1 and V2.

Genetic Characteristics

The prevalence of putative mutations in BrS susceptibility genes was higher in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP (36.8% versus 8.3%, p=0.02). We identified 8 putative mutations in 6 different genes (SCN5A:1, SCN10A:1, SCN4A:3, SCNN1A:1, KCNJ8:1 and KCND3:1) in 7 patients with DI-Type 1 BrP. We identified 3 putative mutations in 3 different genes (SLMAP:1, SCN4A:1 and SCN10A:1) in 3 patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Genetic characteristics of patients with DI-Type 1 BrP are presented in Table 3. One out of 19 (5.2%) patients with DI-Type 1 BrP was also found to carry a second potentially pathogenic BrS mutation (Table 3). Due to the lack of availability of family members, it is uncertain which genetic variant (or both) is causative in this case where two variants were uncovered.

Table 3.

Summary of Putative Mutations in Patients with Drug-Induced Type 1 Brugada Pattern

| Patient No. |

Gene | Exon | Type of Mutation |

Change in Nucleotide |

Change in Amino Acid |

Pathogenicity† | MAF (1000genome) |

MAF (ESP) |

MAF (gnomAD) |

SIFT- Prediction |

Polyphen-2 Prediction |

Provean prediction |

Gene References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | KCNJ8 | 3 | Non-sense | c.1231C>T | p.Gln411* | Pathogenic | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Barajas-Martínez H, et al. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:548–555 |

| 5 | SCN5A | 27 | Missense | c.4789G>A | p.Val1597Met | Pathogenic | NA | NA | 0.0000177 | Damaging | Probably Damaging | Deleterious | Hedley PL, et al. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1486–1511. |

| 8 | KCND3 | 3 | Missense | c.1646G>A | p.Arg549His | Likely pathogenic | NA | NA | 0.0000955 | Damaging | Probably Damaging | Neutral | Giudicessi JR, et al. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1024–1032. |

| 10 | SCN4A | 14 | Insertion | c.2599_2616dupGCTGGAGAGGCGGGGGAG | p.Glu872_Thr873insAlaGlyGluAlaGlyGlu | Likely pathogenic | NA | NA | 0.0000154 | NA | NA | NA | Bissay V, et al. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:400–407. |

| 12 | SCN4A | 1 | Missense | c.296G>T | p.Gly99Val | Likely pathogenic | NA | NA | NA | Damaging | Probably Damaging | Deleterious | Bissay V, et al. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:400–407. |

| 16 | SCN4A | 1 | Missense | c.307T>G | p.Phe103Val | Likely pathogenic | NA | NA | 0.0000198 | Damaging | Probably Damaging | Deleterious | Bissay V, et al. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:400–407. |

| SCNN1A | 7 | Missense | c.1435T>C | p.Cys479Arg | Pathogenic | NA | NA | 0.0000956 | Damaging | Probably Damaging | Deleterious | Juang JM, et al. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6733. | |

| 17 | SCN10A | 23 | Missense | c.4138C>T | p.Arg1380Trp | Likely pathogenic | NA | 0.00007 | 0.0000318 | Damaging | Probably Damaging | Deleterious | Hu D, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:66–79. |

Stop Codon,

According to 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACGM) Standards and Guidelines, 1000 genome = The 1000 Human Genome Project Database, ESP = Exome Sequencing Project, gnomAD = The Genome Aggregation Database, MAF = Minor Allele Frequency, Polyphen-2 = Polymorphism Phenotyping 2, Provean = Protein Variation Effect Analyzer, SIFT = Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant

Discussion

AV-APs are the second most common cause of PSVT.8 The coexistence of AV-APs and BrS has been previously reported by Borggrefe’s group.4,5 There are several important aspects of the relationship between AV-APs and DI-Type 1 BrP. First is the higher prevalence of DI-Type 1 BrP among patients with AV-APs and the epidemiology of DI-Type 1 BrP; second is the clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics of patients who exhibit both features, which helps clinicians predict the presence of DI-Type 1 BrP rather than BrS and arrive at decisions regarding management of these patients, avoidance of unjustified defibrillator implantations and long-term follow-up; third is the lack of relationship between DI-Type 1 BrP and the occurrence of spontaneous, clinical AF; fourth is the development of J-point elevation and appearance of type 1 BrP associated with VF during catheter ablation of AV-APs; and fifth is the underlying genetic characteristics and the mechanistic link between AV-APs and DI-Type 1 BrP, as discussed below.

Epidemiology of DI-Type 1 BrP

The prevalence of DI-Type 1 BrP among patients presenting primarily with AV-APs was 16.1% in our study population. This high prevalence has important implications in terms of epidemiology of DI-Type 1 BrP. The prevalence of PSVT (AVNRT and AVRT) in general population in the U.S. is reported to be approximately 2.25/1,000 individuals.6 If these results could be extrapolated to the entire U.S. population, we estimate that there would be nearly 112,000 new PSVT cases each year. AVRT comprises 40% of all PSVT. If high prevalence of DI-Type 1 BrP in patients with AV-APs is confirmed with further studies, the prevalence of DI-Type 1 BrP may approach ~7,200 new cases per year.

The world-wide prevalence of a Brugada ECG pattern (type 1, 2 and 3) in the general population is estimated to be 0.5 to 1.6 per 1000.2 The prevalence of DI-Type 1 BrP in the general population is unknown. The prevalence of DI-Type 1 BrP in our control group was 4.8%. Our results are consistent with a recently published study showing that the prevalence of fever-induced type-1 Brugada pattern in otherwise asymptomatic patients is 2%, suggesting that fever-induced Type 1 BrP is more prevalent than previously thought.13

Clinical Relevance of DI-Type 1 BrP

Type 1 BrP is usually concealed in patients with AV-APs. As documented in our study, certain clinical and electrocardiograpic characteristics such as presence of chest pain and migraine headaches, and presence of QR/rSr′ pattern in V1 with or without ST-segment elevation, QRS notching/slurring in V2 and lead aVL during pre-excitation and rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 and QRS notching/slurring in lead aVL during orthodromic AVRT should raise the possibility of DI-Type 1 BrP in patients with AV-APs.

Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP do not meet criteria for BrS based on the current J-Wave syndromes expert consensus report Shanghai score system.2 In that many of the patients with DI-Type 1 BrP were asymptomatic, it could be argued that the ajmaline test is a false-positive in all of these cases. We do not subscribe to this hypothesis because it is very difficult to determine beyond doubt whether a positive test result is a true-positive or false-positive with such a short follow-up period. The recent meta-analysis by Sroubek and co-workers reported a risk ranging between 0.27% and 3.2% per year with long-term follow-up in a similar cohort of patients (positive for DI-Type 1 BrP and either asymptomatic or with a history of syncope).14

The coexistence of AV-APs and clinical, spontaneous AVRT and DI-Type 1 BrP is of potential clinical relevance for the appropriate management of those patients in terms of cautious use of certain anti-arrhythmic agents known to exacerbate the Brugada phenotype (Class IC sodium channel blockers, propranolol and calcium-channel blockers), avoidance of Brugada pattern-inducing non-cardiac drugs such as certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and anti-epileptic agents, consideration of standard preventive measures such as use of antipyretics during fever, avoidance of unjustified defibrillator implantations and long term follow-up of these patients.2,15

Clinical Presentation of Patients with DI-Type 1 BrP

There are limited data in terms of relationship between chest pain and migraine headaches and DI-Type 1 BrP. Higher prevalence of chest pain and migraine headache in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP and BrS has been previously reported.3,16 Every patient with AV-APs should be questioned in history taking for the presence of chest pain and/or migraine headache. Further studies are required in order to determine the prevalence, underlying mechanism(s) and characteristics of chest pain and migraine headaches in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP.

Twelve-lead ECG Characteristics During Pre-excitation

Several algorithms have been developed for determining the location of AV-APs mainly based on the polarity of delta waves.11 Besides these previously described, traditional 12-lead ECG characteristics, several, novel 12-lead ECG characteristics during pre-excitation such as QR/rSr′ pattern in V1 with or without ST-segment elevation, QRS notching/slurring in V2 and/or in lead aVL for predicting underlying DI-Type 1 BrP are described in this study (Figure 1). Abnormal QRS configuration (QRS notching/slurring and/or fragmentation) in V2 during pre-excitation was present in all patients with DI-Type 1 BrP. The degree of QRS notching/slurring in V2 and/or in lead aVL have been found to be dynamic and are typically accentuated with higher degrees of pre-excitation (Figure 2). Since the degree of pre-excitation and newly described 12-lead ECG characteristics are dynamic findings, it is important to review of all available, prior 12-lead ECGs for these characteristics.

Prevalence of early repolarization pattern is reported to be ~40–50% in patients with WPW syndrome prior to catheter ablation.17 Following ablation of the accessory pathway, early repolarization pattern persists in 25% of patients, disappears in 18% of patients and appears de novo in 10–15% of patients.17 The clinical and prognostic significance of the high prevalence of early repolarization in patients with WPW syndrome is currently unknown.

In our study, patients with DI-Type 1 BrP had a higher prevalence of an rSr′ in V1 (31.2% versus 10.9%) after successful catheter ablation compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Therefore, an rSr′ pattern in V1 during pre-excitation is due in part to the presence of an rSr′ pattern during sinus rhythm after catheter ablation. Other potential cause(s) for an rSr′ pattern in V1 include higher placement of electrodes in V1-V2 and J-point elevation. Prevalence of QRS notching/slurring in aVL (68.8% versus 34.2%) but not in V2 (25% versus 11%) after successful catheter ablation was significantly higher in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP. Therefore, the higher prevalence of QRS notching/slurring in aVL during pre-excitation is due in part to the higher prevalence of QRS notching/slurring in aVL during sinus rhythm after catheter ablation in patients with DI-Type 1 BrP. Our finding suggest that, pre-excitation is associated with an underlying QRS notching/slurring particularly in V2.

Twelve-lead ECG Characteristics During Orthodromic AVRT

Overall, patients with orthodromic AVRT typically have certain characteristics on 12-lead ECG including separation of P-waves (> 90 ms) from QRS complexes (~ 80%), ST-segment depression (≥2mm) and/or T-wave inversions (~ 60%) and QRS alternans (~ 20–25%).8 In addition to these previously described 12-lead ECG characteristics, our study population with DI-Type 1 BrP had higher prevalence of rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 and QRS notching/slurring in lead aVL during orthodromic AVRT compared to patients without DI-Type 1 BrP (Figures 3 and 4).

An rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 during orthodromic AVRT can be due to presence of rSr′ pattern during sinus rhythm, higher placement of electrodes in V1-V2, tachycardia-induced functional right bundle branch block, J-point elevation and retrograde P waves distorting the QRS complex. An rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 during sinus rhythm after catheter ablation was present in 44% of patients with DI-Type 1 BrP and orthodromic AVRT in our study. An rSr′ pattern in V1-V2 during orthodromic AVRT is often a tachycardia-related phenomenon as shown in Figures 3 and 4. It has been previously reported that the ECG phenotype in patients with BrS accentuated during recovery form exercise, due to vagal influences.18 Retrograde P waves distorting the QRS complex is probably an unlikely explanation since the P waves during orthodromic AVRT often located further away from the QRS complexes.

DI-Type 1 BrP: The Link Between AV-APs and Occurrence of Spontaneous, Clinical Atrial Fibrillation?

Patients with AV-APs have an increased propensity to develop AF.19 Male gender, older age, multiple AV-APs, presence of pre-excitation and spontaneous AVRT, presence of structural heart disease, intrinsic atrial vulnerability due to developmental defects, and arrhythmogenic pulmonary veins have been proposed as the underlying mechanisms for this propensity. On the other hand, the prevalence of AF in patients with BrS has been reported to be higher than in the general population of the same age. More recent studies with larger cohorts reported a prevalence of ~5 to 10%.2 The prevalence of history of AF prior to catheter ablation was similar in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP in our study population. This may well be due to the modulatory influence of underlying mutations. The role of SCN5A mutations in the development of AF in patients with BrS has been extensively studied.20 Because of the lack of long-term follow-up we are unable to determine definitively whether patients with DI-Type 1 BrP and AV-APs are more or less prone to develop AF.

The mechanism of sudden cardiac arrest and sudden death in most patients with WPW syndrome and WPW “pattern” is thought to be due to AF with pre-excitation resulting in a very rapid ventricular rate that can lead to VF.21,22 Electrophysiologic risk factors for the development of VF include presence of spontaneous and/or inducible AVRT, presence of multiple accessory pathways, shortest pre-excited R-R interval (< 250 ms) during pre-excited AF and a short (≤ 250 ms) antegrade effective refractory period of the accessory pathway.19 Successful catheter ablation of AV-APs in resuscitated patients with WPW syndrome has been reported to prevent recurrences of cardiac arrest.23 Prior to ablation of the accessory pathway, VF developed spontaneously in 32 of 48 resuscitated patients and after intravenous administration of antiarrhythmic agents in 16 patients. Six out of 48 (12.5%) patients were on antiarrhythmic agents (propafenone [n=4] and prajmaline [n=2]) known to exacerbate the Brugada phenotype at the time of the cardiac event. After ablation, none of the patients showed any other ECG abnormalities suggesting additional electrical disease such as long QT syndrome or BrS.23

The prevalence of spontaneous, clinical pre-excited AF was similar in patients with and without DI-Type 1 BrP and none of the patients had a history of cardiac arrest in our study population. The percentage of patients with spontaneous, clinical pre-excited AF developing VF, the underlying myocardial substrate for the development of VF and the role of DI-Type 1 BrP in those patients is largely unknown. The presence of structural heart disease (particularly congenital heart diseases and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) has been reported to be a risk factor for the development of VF.24,25 Based on our findings, underlying DI-Type 1 BrP can unmask a myocardial substrate for malignant ventricular arrhythmias in these patients. We recommend that patients with WPW syndrome or WPW “pattern” and cardiac arrest undergo drug challenge to rule out the possibility of DI-Type 1 BrP.

J-point Elevation and Appearance of Type 1 BrP During Catheter Ablation of AV-APs

It was recently reported that J-point elevation and type 1 BrP associated with polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and/or VF can be induced (in the presence of normal coronary arteries) by catheter ablation of AV-APs.26 The study included 4 patients (2M/2F, age range 21 to 72 years) all with left-sided accessory pathways undergoing catheter ablation.26 Each patient developed chest pain during radiofrequency catheter ablation of the AV-APs followed by J-point elevation, type 1 BrP and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and VF. Chest pain and ECG changes were resolved by intravenous atropine. None of the patients underwent an ajmaline challenge test. We recommend that patients with J-point elevation and appearance of type 1 BrP associated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias during catheter ablation of AV-APs should undergo drug challenge test in order to rule out the possibility of BrS and need for close follow-up.

Genetics and The Mechanistic Link Between AV-APs and DI-Type 1 BrP

AV-AP formation underlying ventricular pre-excitation seem to arise as a consequence of erroneous development of the AV canal myocardium.27–29 After the formation of the primitive heart tube during early embryonic development, the AV canal myocardium develops between the atrial and ventricular myocardium. The AV canal myocardium gives rise to several cardiac components, including the future AV valves, ventricular septum, outflow tracts, and atrial part of the AV conduction axis. Notch and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways, transcription factors such as Tbx5/Tbx3/Tbx2, Hey1/Hey2, BMP2/4, Gata4 and Nkx2.5 play a regulatory role in the normal patterning and functional maturation of the AV canal myocardium.27–29 Activation of Notch signaling and Tbx2 deficiency within murine myocardium result in AV-AP formation and ventricular pre-excitation, similar to WPW syndrome.27–29

It is tempting to speculate that the genetic defects giving rise to the accessory pathways during embryological development also predispose the RVOT to development of the substrate for BrS.30

Genetic variants in proteins in the signaling pathways and/or transcription factors can potentially cause DI-Type 1 BrP or BrS.31,32 Loss-of-function mutation in Tbx5 (G145R) has been shown to cause BrS in humans.31 Tbx5 and Tbx3 have been also shown to regulate the BrS susceptibility genes “SCN5A-SCN10A” locus and effect the expression of SCN5A.33 Hey2 has been recently shown to be a BrS susceptibility gene by modulating cardiac transmural ion channel patterning and electrical heterogeneity.32 In addition, activation of canonical Wnt signaling has been shown to decrease SCN5A mRNA levels, Nav1.5 protein and Na+ current density in rat ventricular myocytes.34

The putative mutations in BrS susceptibility genes (e.g., SCN5A, SCN10A, SCN4A, SCNN1A, KCNJ8 and KCND3) identified in this study likely contribute to the DI-Type 1 BrP, although further study is needed to reach this conclusion.

Study limitations

The follow-up period was short therefore we are not able to report the long-term outcomes. None of the patients had history of cardiac arrest in our study population. Patients with WPW syndrome and WPW “pattern” had different degrees of cardiac memory after catheter ablation at the time of ajmaline challenge tests. The interpretation of the ajmaline challenge was not performed in a blinded fashion in the study. Additional functional expression studies are needed to ascertain the degree to which the novel mutations uncovered lead to loss of function of inward current or gain of function of outward currents known to predispose to the J wave syndromes.

Conclusions

DI-Type 1 BrP is relatively common in patients with AV-APs. We identify 12-lead ECG characteristics during pre-excitation and orthodromic AVRT that point to the presence of underlying type 1 BrP. Because of the lack of long-term follow-up, we are unable to determine definitively whether patients with DI-Type 1 BrP and AV-APs are more or less prone to develop AF.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to the staff of the Sixth Core Laboratory, Department of Medical Research, National Taiwan University Hospital for technical support.

Sources of Funding: We acknowledge support from the NIH (Grant # HL47678) and from the Wistar and Martha Morris fund. Financial support for this research was also provided partially through grants NTUH 106-S3469, NTUH106-S3458, NTUH 105-012, NTUH 106-018, and NTUH 105-S2995 from National Taiwan University Hospital, National Taiwan University, and MOST 104 - 2314 - B - 002 - 193 - MY3, MOST 106-2314-B-002 -047 -MY3, MOST 106-2314-B-002 -134 -MY2 and MOST 106-2314-B-002-206 from the Ministry of Science and Technology and Taiwan Health Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

Authors’ Contributions

Can Hasdemir: Concept/design, Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Jimmy Jyh-Ming Juang: Concept/design, Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Sedat Kose: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Umut Kocabas: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Mehmet N. Orman: Concept/design, Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article, Statistics.

Serdar Payzin: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Hatice Sahin: Data analysis/interpretation, Data collection, Approval of article.

Candan Celen: Data analysis/interpretation, Data collection, Approval of article.

Emin E. Ozcan: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Ching-Yu Julius Chen: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Ramazan Gunduz: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Oguzhan E. Turan: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Oktay Senol: Data analysis/interpretation, Data collection, Approval of article.

Elena Burashnikov: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

Charles Antzelevitch: Concept/design, Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article, Critical revision of article, Data collection, Approval of article.

References

- 1.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antzelevitch C, Yan GX, Ackerman MJ, et al. J-Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: Emerging concepts and gaps in knowledge. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:e295–e324. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasdemir C, Payzin S, Kocabas U, et al. High prevalence of concealed Brugada syndrome in patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1584–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckardt L, Kirchhof P, Loh P, et al. Brugada syndrome and supraventricular tachyarrhythmias: a novel association? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:680–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schimpf R, Giustetto C, Eckardt L, et al. Prevalence of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in a cohort of 115 patients with Brugada syndrome. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2008;13:266–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2008.00230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orejarena LA, Vidaillet H, Jr, DeStefano F, Nordstrom DL, Vierkant RA, Smith PN, et al. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:150–157. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chugh A, Morady F. Preexcitation, Atrioventricular Reentry, and Variants. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, Stevenson WG, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology From Cell to Bedside. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc; 2017. pp. 755–765. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Take Y, Morita H. Fragmented QRS: What Is the Meaning? Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2012;12:213–225. doi: 10.1016/s0972-6292(16)30544-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huikuri HV, Marcus F, Krahn AD. Early repolarization: an epidemiologist’s and a clinician’s view. J Electrocardiol. 2013;46:466–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arruda MS, McClelland JH, Wang X, et al. Development and validation of an ECG algorithm for identifying accessory pathway ablation site in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adler A, Topaz G, Heller K, et al. Fever-induced Brugada pattern: how common is it and what does it mean? Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1375–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sroubek J, Probst V, Mazzanti A, et al. Programmed Ventricular Stimulation for Risk Stratification in the Brugada Syndrome: A Pooled Analysis. Circulation. 2016;133:622–630. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Postema PG, Wolpert C, Amin AS, et al. Drugs and Brugada syndrome patients: review of the literature, recommendations, and an up-to-date website (www.brugadadrugs.org) Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1335–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu D, Barajas-Martínez H, Pfeiffer R, et al. Mutations in SCN10A are responsible for a large fraction of cases of Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizumaki K, Nishida K, Iwamoto J, et al. Early repolarization in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: prevalence and clinical significance. Europace. 2011;13:1195–1200. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin AS, de Groot EA, Ruijter JM, Wilde AA, Tan HL. Exercise-induced ECG changes in Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:531–539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.862441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obeyesekere MN, Klein GJ. Application of the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines for risk stratification for sudden death in adult patients with asymptomatic pre-excitation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28:841–848. doi: 10.1111/jce.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin AS, Boink GJ, Atrafi F, et al. Facilitatory and inhibitory effects of SCN5A mutations on atrial fibrillation in Brugada syndrome. Europace. 2011;13:968–975. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreifus LS, Haiat R, Watanabe Y, Arriaga J, Reitman N. Ventricular fibrillation. A possible mechanism of sudden death in patients and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Circulation. 1971;43:520–527. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein GJ, Bashore TM, Sellers TD, Pritchett EL, Smith WM, Gallagher JJ. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1080–1085. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197911153012003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antz M, Weiss C, Volkmer M, et al. Risk of sudden death after successful accessory atrioventricular pathway ablation in resuscitated patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:231–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cain N, Irving C, Webber S, Beerman L, Arora G. Natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome diagnosed in childhood. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:961–965. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Behr ER, Sharma S, Sheppard M. Sudden Cardiac Death in Pre-Excitation and Wolff-Parkinson-White: Demographic and Clinical Features. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1644–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang GS, Park JS, Yang HM, et al. Noncoronary ST elevation and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia during left-sided accessory pathway ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24:1240–1245. doi: 10.1111/jce.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rentschler S, Harris BS, Kuznekoff L, et al. Notch signaling regulates murine atrioventricular conduction and the formation of accessory pathways. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:525–533. doi: 10.1172/JCI44470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aanhaanen WT, Boukens BJ, Sizarov A, et al. Defective Tbx2-dependent patterning of the atrioventricular canal myocardium causes accessory pathway formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:534–544. doi: 10.1172/JCI44350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aanhaanen WT, Moorman AF, Christoffels VM. Origin and development of the atrioventricular myocardial lineage: insight into the development of accessory pathways. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:565–577. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antzelevitch C. Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:1130–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bersell KR, Yang T, Hong CC, et al. Genomic editing in iPSCS establishes that a rare Tbx5 variant causes Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2016;(Supplement Issue 5) “Abstracts”. AB04-02. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veerman CC, Podliesna S, Tadros R, et al. The Brugada Syndrome Susceptibility Gene HEY2 Modulates Cardiac Transmural Ion Channel Patterning and Electrical Heterogeneity. Circ Res. 2017;121:537–548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Boogaard M, Barnett P, Christoffels VM. From GWAS to function: genetic variation in sodium channel gene enhancer influences electrical patterning. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2014;24:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang W, Cho HC, Marbán E. Wnt signalling suppresses voltage-dependent Na+ channel expression in postnatal rat cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2015;593:1147–1157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.285551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]