Workers in the fish processing industry have increased risk of developing respiratory diseases due to occupational exposure to bioaerosols and related allergens [1–4]. The literature reports more occupational asthma in workers handling salmon [2, 5], and an exposure–response relationship between total protein exposure and cross-shift changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and lower respiratory tract symptoms [6]. To our knowledge, there are no published reports on hypersensitivity pneumonitis from this industry. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a complex disease for which there are no generally accepted diagnostic criteria, particularly at earlier stages of the disease. We present the case of a fish processing worker diagnosed with hypersensitivity pneumonitis caused by proteins from salmon, in which the aetiology was established using specific inhalation challenge (SIC) as a diagnostic tool.

Short abstract

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis may be caused by occupational exposure in the fish processing industry http://ow.ly/GbEf30lFnyk

To the Editor:

Workers in the fish processing industry have increased risk of developing respiratory diseases due to occupational exposure to bioaerosols and related allergens [1–4]. The literature reports more occupational asthma in workers handling salmon [2, 5], and an exposure–response relationship between total protein exposure and cross-shift changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and lower respiratory tract symptoms [6]. To our knowledge, there are no published reports on hypersensitivity pneumonitis from this industry. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a complex disease for which there are no generally accepted diagnostic criteria, particularly at earlier stages of the disease. We present the case of a fish processing worker diagnosed with hypersensitivity pneumonitis caused by proteins from salmon, in which the aetiology was established using specific inhalation challenge (SIC) as a diagnostic tool.

Processing of salmon includes two main processes: 1) in the slaughtering department, the fish are slaughtered, sorted, automatically or manually gutted, and washed before further processing; and 2) in the filleting department, the salmon is filleted and skinned by machines before manual trimming of the fillets [2]. The main source of exposure to fish proteins is by inhalation of wet bioaerosols containing a heterogeneous mixture of proteins, enzymes, endotoxins and moulds [1, 2, 6, 7].

A never-smoking man in his 40s with no history of allergies or respiratory symptoms/disease started experiencing cough, wheezing, dyspnoea, and general symptoms including fatigue, nausea and fever (38–40°C) at work, after being employed at a salmon processing plant for ∼3 years. The symptoms typically started 3–4 h after starting a work shift, and continued throughout the afternoon, evening and night. He felt better the next morning, and during weekends and holidays. He also experienced suspected pneumonias up to four times a year and eventually, increasing dyspnoea during physical activity. When he was referred to our clinic, he had been employed as a process worker for 6 years, mainly in the slaughtering department as a gutter. He had no known exposure to other causative factors of hypersensitivity pneumonitis during his spare time [8].

At the time of referral, two other patients from the same plant had been diagnosed with occupational asthma caused by exposure to salmon proteins. The airborne concentration of total protein in the slaughtering department (inlet, automatically or manually gutting) ranged between not detected and 20.4 µg·m−3 (six full-shift stationary measurements), compatible with the higher range of previously reported exposure levels (personal samples) in this industry [6].

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an inflammatory disease involving the small airways and interstitium that can be caused by sensitisation to a wide array of antigens, mostly proteins. The clinical presentation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis is variable and there is no consensus regarding disease definition [8]. Proposed diagnostic criteria include: 1) exposure to an offending agent; 2) clinical, radiographic and physiological findings compatible with hypersensitivity pneumonitis; 3) bronchoalveolar lavage reveals lymphocytosis; 4) positive SIC; and 5) compatible histopathology [9]. SIC is a well-established method for the diagnosis of occupational asthma [10] and a modified protocol is used to diagnose hypersensitivity pneumonitis. This protocol is less standardised [11] and a variety of diagnostic criteria for test positivity has been proposed [12]. We used criteria proposed by Morell et al. [13], defining a test positive for hypersensitivity pneumonitis as follows: 1) forced vital capacity (FVC) decrease >15% or diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) decrease >20% compared with baseline values; or 2) FVC decrease 10–15% and at least one of a) white blood cell increase ≥20%, b) peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) decrease ≥3%, c) significant radiological changes, d) rise in body temperature >0.5°C and e) clinical symptoms (e.g. cough or dyspnoea); or 3) FVC decrease <10% and at least three of criteria 2a–e.

To reproduce the patient's working conditions and to ensure a sufficient level of bioaerosol in the challenge chamber, the patient filleted salmon in the chamber for 15 min and subsequently sprayed a dispersion of salmon meat on a surface ∼30 cm from his face for 5 min. Following the challenge, spirometry, DLCO, symptoms, physical examination, temperature and SpO2 were recorded after 30 min, and then hourly for the next 6 h. A white blood cell count was performed before and after the challenge.

At baseline, a physical examination including auscultation did not show abnormalities. Pulmonary function tests were within the normal range; however, there was a tendency for low DLCO (74% of predicted) [14] and spirometry indicating a restrictive pattern (FEV1 3.29 L, 81% of predicted; FVC 3.91 L, 80% of predicted; FEV1/FVC 84%) [15]. The patient had no symptoms, total IgE 7 kU·L−1, and negative specific IgE towards parvalbumin and common airways allergens. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the lungs showed localised slight ground-glass opacities and mild traction bronchiectasis in the lower lobes, compatible with hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

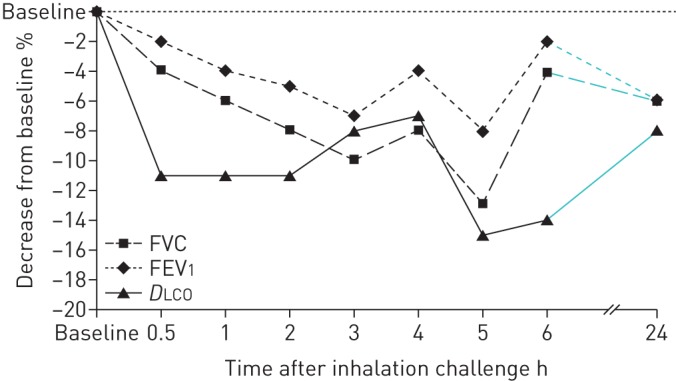

After inhalation challenge with salmon, the patient developed influenza-like symptoms and dyspnoea. Compared to baseline values, he experienced a fall in DLCO and FVC of 15% and 13%, respectively, 5 h post-challenge (figure 1). SpO2 decreased by 4% and fine crackles were heard by auscultation. There were no significant changes in white blood cell count or temperature.

FIGURE 1.

Changes in forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) during 24 h following exposure to salmon in a challenge chamber.

The day after exposure, the patient was asymptomatic and lung function tests approached pre-test values.

This patient working in the fish processing industry was referred for possible occupational asthma ∼3 years after the onset of respiratory symptoms. He had a spirometric pattern suggesting a restrictive lung function deficit and exertional dyspnoea. Due to a clinical picture suggestive of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, he was evaluated using a SIC protocol developed for diagnosing hypersensitivity pneumonitis [12]. Following challenge to salmon, he developed influenza-like symptoms, fine crackles upon auscultation of the lungs, and reduced DLCO and FVC, a response compatible with diagnostic criteria for hypersensitivity penumonitis [12, 13].

Asthma is probably the most frequent respiratory disease associated with the fish processing industry. However, hypersensitivity pneumonitis should be considered if the patient exhibits a clinical picture with influenza-like symptoms and dyspnoea. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a complex syndrome characterised by a variable combination of inflammation and fibrosis in the airways and the lung parenchyma, and may lead to chronic respiratory disability. Early diagnosis and removal of exposure are therefore critical [8].

We chose to establish an occupation–disease relationship and a possible aetiological diagnosis, since conventional methods such as HRCT and histological findings cannot establish the aetiology of the disease. In the absence of SIC, recommendations with regard to further work will usually be based on symptom history.

Based on the results from the SIC, we recommended the patient stop working in the fish processing industry. During a follow-up period of 1 year after he left this industry, he did not experience any cough or fever but still had exertional dyspnoea and a spirometric pattern suggesting a restrictive lung function deficit. The radiological findings were normalised on a computed tomography performed >2 years later.

There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for hypersensitivity pneumonitis in the literature. Conventional methods such as HRCT and histological findings are most appropriate in the diagnosis of later stage disease, while SIC has proven useful as a diagnostic tool in the earlier stages. Application of the criteria formulated by Morell et al. [13] may contribute to an early diagnosis and hence to a better prognosis [8]. However, the SIC criteria for hypersensitivity pneumontis need validation.

Acknowledgements

Lene Svendsen (Dept of Thoracic Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway) performed the lung function measurements and Gaute Wathle (Dept of Radiology, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway) contributed to the discussion of the HRCT of the lungs.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.Bang B, Aasmoe L, Aamodt BH, et al. Exposure and airway effects of seafood industry workers in northern Norway. J Occup Environ Med 2005; 47: 482–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlman-Hoglund A, Renstrom A, Larsson PH, et al. Salmon allergen exposure, occupational asthma, and respiratory symptoms among salmon processing workers. Am J Ind Med 2012; 55: 624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopata AL, Jeebhay MF. Airborne seafood allergens as a cause of occupational allergy and asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2013; 13: 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharp MF, Lopata AL. Fish allergy: in review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2014; 46: 258–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas JD, McSharry C, Blaikie L, et al. Occupational asthma caused by automated salmon processing. Lancet 1995; 346: 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiryaeva O, Aasmoe L, Straume B, et al. Respiratory effects of bioaerosols: exposure-response study among salmon-processing workers. Am J Ind Med 2014; 57: 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeebhay MF, Cartier A. Seafood workers and respiratory disease: an update. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 10: 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quirce S, Vandenplas O, Campo P, et al. Occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an EAACI position paper. Allergy 2016; 71: 765–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morell F, Villar A, Ojanguren I, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: challenges in diagnosis and management, avoiding surgical lung biopsy. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 37: 395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandenplas O, Suojalehto H, Aasen TB, et al. Specific inhalation challenge in the diagnosis of occupational asthma: consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1573–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz X, Sanchez-Ortiz M, Torres F, et al. Diagnostic yield of specific inhalation challenge in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 1658–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz X, Morell F, Cruz MJ. The use of specific inhalation challenge in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 13: 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morell F, Roger A, Reyes L, et al. Bird fancier's lung: a series of 86 patients. Medicine 2008; 87: 110–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulsvik A, Bakke P, Humerfelt S, et al. Single breath transfer factor for carbon monoxide in an asymptomatic population of never smokers. Thorax 1992; 47: 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulsvik A, Tosteson T, Bakke P, et al. Expiratory and inspiratory forced vital capacity and one-second forced volume in asymptomatic never-smokers in Norway. Clin Physiol 2001; 21: 648–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]