The crystal structure of glyoxysomal malate dehydrogenase (MDH3) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was determined at 2.1 Å resolution in complex with NAD+ and oxaloacetate. The structure of the active-site loop in MDH3 differed from those of mitochondrial and cytosolic malate dehydrogenases.

Keywords: malate dehydrogenase, glyoxysome, fatty-acid β-oxidation, X-ray crystallography, MDH3, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Abstract

Malate dehydrogenase (MDH), a carbohydrate and energy metabolism enzyme in eukaryotes, catalyzes the interconversion of malate to oxaloacetate (OAA) in conjunction with that of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to NADH. Three isozymes of MDH have been reported in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: MDH1, MDH2 and MDH3. MDH1 is a mitochondrial enzyme and a member of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, whereas MDH2 is a cytosolic enzyme that functions in the glyoxylate cycle. MDH3 is a glyoxysomal enzyme that is involved in the reoxidation of NADH, which is produced during fatty-acid β-oxidation. The affinity of MDH3 for OAA is lower than those of MDH1 and MDH2. Here, the crystal structures of yeast apo MDH3, the MDH3–NAD+ complex and the MDH3–NAD+–OAA ternary complex were determined. The structure of the ternary complex suggests that the active-site loop is in the open conformation, differing from the closed conformations in mitochondrial and cytosolic malate dehydrogenases.

1. Introduction

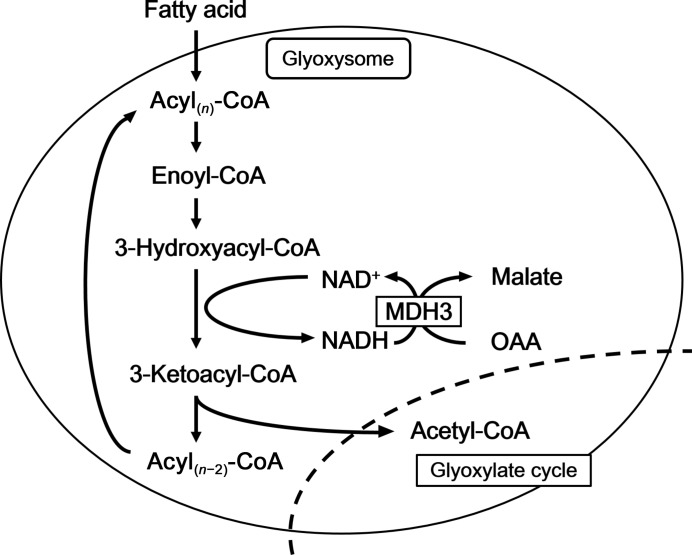

Malate dehydrogenase (MDH) reversibly catalyzes the oxidation/reduction of malate/oxaloacetate (OAA) in the presence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)/NADH as a coenzyme (Minárik et al., 2002 ▸). In eukaryotic cells, the malate–OAA conversion represents an important step in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) and glyoxylate cycles. Three isozymes of MDH (MDH1, MDH2 and MDH3) have been reported in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. MDHs play important roles in various cellular processes. MDH1 is a mitochondrial isozyme and functions in the TCA cycle (Minard & McAlister-Henn, 1991 ▸). MDH2 is a predominantly cytosolic isozyme which oxidizes malate to OAA in the glyoxylate cycle (Minard & McAlister-Henn, 1991 ▸) and participates in the malate/aspartate shuttle. MDH3 is a glyoxysomal isozyme (Steffan & McAlister-Henn, 1992 ▸) which is an essential component of the gluconeogenesis pathway that generates glucose from noncarbohydrate carbon substrates and is involved in the reoxidation of NADH produced by fatty-acid β-oxidation in glyoxysomes (Figs. 1 ▸ and 2 ▸; van Roermund et al., 1995 ▸). In plants and fungi, the glyoxylate cycle and fatty-acid β-oxidation play multiple roles in growth. In Arabidopsis thaliana, glyoxysomal MDH is required in fatty-acid β-oxidation but not in the glyoxylate cycle (Pracharoenwattana et al., 2007 ▸).

Figure 1.

MDH3 regenerates NAD+ by reducing OAA to malate during fatty-acid β-oxidation. The glyoxysomal membrane is impermeable to large molecules such as NAD+. NAD+ is supplied from intra-glyoxysomal NADH by MDH3.

Figure 2.

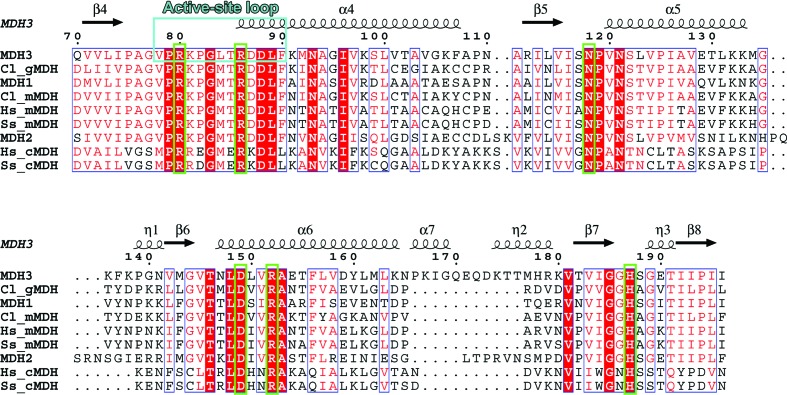

Amino-acid sequence alignment around the active-site loop and active-site residues in yeast MDHs and those from other organisms. The secondary-structure elements and sequence numbering correspond to those of MDH3. The active-site loop and active-site residues are shown in cyan and green boxes, respectively. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994 ▸). The secondary-structure assignment and figure were produced using ESPript (Robertson, 2014 ▸). Cl, Citrullus lanatus; Hs, Homo sapiens; Ss, Sus scrofa; g, glyoxysomal; m, mitochondrial; c, cytosomal.

The yeast mitochondrial enzyme (MDH1) is more closely related to its glyoxysomal counterpart (MDH3) than to the cytoplasmic enzyme (MDH2) (Minárik et al., 2002 ▸). Sequence similarity is highest between MDH1 and MDH3 (49%), followed by that between MDH1 and MDH2 (46%), and that between MDH2 and MDH3 (41%) (Fig. 2 ▸). MDH3 is a 37.2 kDa homodimer. The apparent K m value of MDH3 for OAA (0.3 mM) is almost four times higher than those of MDH1 and MDH2 (both 0.07 mM) (Steffan & McAlister-Henn, 1992 ▸). Additionally, the isoelectric point (pI) of MDH3 is basic, whereas those of MDH1 and MDH2 are acidic (Steffan & McAlister-Henn, 1992 ▸). Crystal structures have been elucidated of porcine mitochondrial and cytoplasmic MDHs (Roderick & Banaszak, 1986 ▸; Birktoft et al., 1989 ▸), the precursor and mature forms of glyoxysomal MDH from watermelon (Cox et al., 2005 ▸), and some bacterial MDHs.

The structural properties of MDH3 that are required for fatty-acid β-oxidation are currently unknown. In this study, we determined the structures of apo MDH3, the MDH3–NAD+ complex and the MDH3–NAD+–OAA ternary complex at resolutions of 2.1, 2.0 and 2.1 Å, respectively. The elucidated structures provide an explanation for the unique properties of MDH3.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

To create a construct encoding N-terminally hexahistidine–small ubiquitin-related modifier 1 (SUMO1)-tagged MDH3, the yeast MDH3 cDNA was amplified by PCR from yeast genomic DNA and cloned into pCold I vector using BamHI and SalI restriction endonucleases. The recombinant vector was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. The bacterial culture was grown at 37°C. Once an optical density of 0.5–0.6 at 600 nm absorbance (OD600) had been attained, expression of the MDH3 gene was induced by adding isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM and the bacterial culture was incubated at 16°C for 24 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5053g for 15 min, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and lysed by sonication. The cell lysate was loaded onto an Ni2+ Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) and the bound protein was eluted from the column using elution buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole). For the purification of MDH3, the tag was proteolytically cleaved by adding ubiquitin-like-specific protease 1 (Ulp1) and incubating overnight at 4°C. Further purification was performed using a HiLoad Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) in gel-filtration buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol). A summary of the macromolecule-production information is given in Table 1 ▸.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | S. cerevisiae (strain W303) |

| DNA source | Genomic DNA |

| Forward primer† | 5′-CTCCTGGATCCATGGTCAAAGTCGCAATT-3′ |

| Reverse primer‡ | 5′-CCAGCGTCGACTCATAGCTTGGAAGAGTC-3′ |

| Cloning vector | pCold I |

| Expression vector | pCold I |

| Expression host | E. coli BL21 (DE3) |

| Complete amino-acid sequence of the construct produced§ | MNHKVHHHHHHIEGRHMDSEVNQEAKPEVKPEVKPETHINLKVSDGSSEIFFKIKKTTPLRRLMEAFAKRQGKEMDSLRFLYDGIRIQADQAPEDLDMEDNDIIEAHREQIGGGSMVKVAILGASGGVGQPLSLLLKLSPYVSELALYDIRAAEGIGKDLSHINTNSSCVGYDKDSIENTLSNAQVVLIPAGVPRKPGLTRDDLFKMNAGIVKSLVTAVGKFAPNARILVISNPVNSLVPIAVETLKKMGKFKPGNVMGVTNLDLVRAETFLVDYLMLKNPKIGQEQDKTTMHRKVTVIGGHSGETIIPIITDKSLVFQLDKQYEHFIHRVQFGGDEIVKAKQGAGSATLSMAFAGAKFAEEVLRSFHNEKPETESLSAFVYLPGLKNGKKAQQLVGDNSIEYFSLPIVLRNGSVVSIDTSVLEKLSPREEQLVNTAVKELRKNIEKGKSFILDSSKL |

The BamHI site is underlined.

The SalI site is underlined.

The hexahistidine–SUMO tag is italicized.

2.2. Crystallization

Purified MDH3 was concentrated to 16.2 mg m1−1 in a buffer consisting of 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Crystallization experiments were performed by the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method at 20°C using various commercial screening kits. Several screening conditions produced plate-shaped crystals, and promising crystals were identified in three conditions: condition No. 26 from Wizard Classic 2 (Rigaku Reagents, Tokyo, Japan) (apo form); condition No. 82 from Index (Hampton Research, California, USA) (NAD+-bound form); and condition No. 48 from Wizard Classic 3 (Rigaku Reagents, Tokyo, Japan) (NAD+/OAA-bound form). Crystals of MDH3 complexed with NAD+ (MDH3–NAD+) were prepared by soaking apo MDH3 crystals with 20 mM NAD+ in 25%(w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350, 0.1 M bis-Tris pH 5.5, 0.2 M MgCl2. Crystals of MDH3 in complex with NAD+ and OAA (MDH3–NAD+–OAA) were prepared by soaking apo MDH3 crystals with 20 mM NAD+ and 150 mM OAA in 20%(w/v) PEG 10 000, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5. A summary of the crystallization conditions is given in Table 2 ▸.

Table 2. Crystallization.

| Apo form | NAD+ complex | NAD+/OAA complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Sitting-drop vapor diffusion | ||

| Plate type | 96-well 2-drop MRC crystallization plates | ||

| Temperature (K) | 293 | ||

| Protein concentration (mg ml−1) | 16.2 | ||

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT | ||

| Composition of reservoir solution | 0.1 M CHES pH 9.5, 30%(v/v) PEG 400 | 0.1 M bis-Tris pH 5.5, 0.2 M MgCl2, 25%(w/v) PEG 3350 | 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5,20%(w/v) PEG 10 000 |

| Volume and ratio of drop | 1 µl:1 µl | ||

| Volume of reservoir (µl) | 50 | ||

2.3. Data collection and processing

Apo MDH3, MDH3–NAD+ and MDH3–NAD+–OAA crystals were soaked in reservoir solution containing 20% glycerol and subsequently flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data sets for apo MDH3, MDH3–NAD+ and MDH3–NAD+–OAA were collected at 100 K on BL44XU at SPring-8, Hyogo, Japan. The data sets were processed using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▸). Data-collection and processing statistics for the crystals are given in Table 3 ▸.

Table 3. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Apo form | NAD+ complex | NAD+/OAA complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffraction source | BL44XU, SPring-8 | BL44XU, SPring-8 | BL44XU, SPring-8 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.900 | 0.900 | 0.900 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Detector | MX300-HE CCD | MX300-HE CCD | MX300-HE CCD |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 300 | 280 | 250 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Space group | P212121 | P21 | P212121 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 57.5, b = 86.6, c = 132.9 | a = 45.1, b = 92.6, c = 82.1, β = 99.9 | a = 57.1, b = 86.7, c = 135.1 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.65–0.83 | 1.46–1.85 | 0.6–1.06 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–2.10 (2.14–2.10) | 50–2.00 (2.03–2.00) | 50–2.10 (2.14–2.10) |

| Total No. of reflections | 261381 | 157113 | 279474 |

| No. of unique reflections | 39231 | 44896 | 40043 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (100.0) | 99.8 (100.0) | 99.9 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 6.7 (6.3) | 3.5 (3.4) | 7.0 (6.8) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 60.1 (10.5) | 30.4 (4.0) | 40.0 (5.7) |

| R p.i.m. | 0.034 (0.143) | 0.048 (0.329) | 0.028 (0.186) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 29.3 | 22.0 | 27.0 |

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

The structure of MDH3 was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser (McCoy, 2007 ▸) using the MDH structure with PDB code 1mld (Gleason et al., 1994 ▸) as a search model. The apo MDH3 model was built using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸) and refined using REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸). The structures of the MDH3–NAD+ and MDH3–NAD+–OAA complexes were determined by molecular replacement with Phaser using the refined model of apo MDH3. Model validations were performed using the wwPDB Validation Service (Gore et al., 2017 ▸). Structure-solution and refinement statistics for the crystals are listed in Table 4 ▸. Structural figures were generated using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▸). Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as entries 5zi3, 5zi2 and 5zi4 for apo MDH3 and the MDH3–NAD+ and MDH3–NAD+–OAA complexes, respectively.

Table 4. Structure solution and refinement.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Apo form | NAD+ complex | NAD+/OAA complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) | 43.50–2.10 (2.16–2.10) | 50.00–2.00 (2.05–2.00) | 47.75–2.10 (2.15–2.10) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.8 (99.6) | 99.5 (97.2) | 99.7 (97.1) |

| No. of reflections, working set | 37057 (2714) | 42491 (3085) | 37905 (2698) |

| No. of reflections, test set | 1899 (149) | 2246 (160) | 2015 (122) |

| Final R cryst | 0.202 (0.255) | 0.175 (0.283) | 0.196 (0.259) |

| Final R free | 0.265 (0.336) | 0.230 (0.312) | 0.266 (0.366) |

| No. of non-H atoms | |||

| Protein | 5172 | 5189 | 5164 |

| Ion | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Ligand | 0 | 71 | 106 |

| Glycerol | 12 | 6 | 0 |

| Water | 92 | 203 | 157 |

| Total | 5276 | 5471 | 5427 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.016 |

| Angles (°) | 1.764 | 1.953 | 1.910 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | |||

| Overall | 43.6 | 31.5 | 40.4 |

| Protein | 43.6 | 31.3 | 40.7 |

| Ion | 26.8 | ||

| Ligand | 35.8 | 35.0 | |

| Glycerol | 60.0 | 54.3 | |

| Water | 38.3 | 33.2 | 33.8 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| Most favored (%) | 97 | 98 | 97 |

| Allowed (%) | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

3. Results

3.1. MDH3 structure

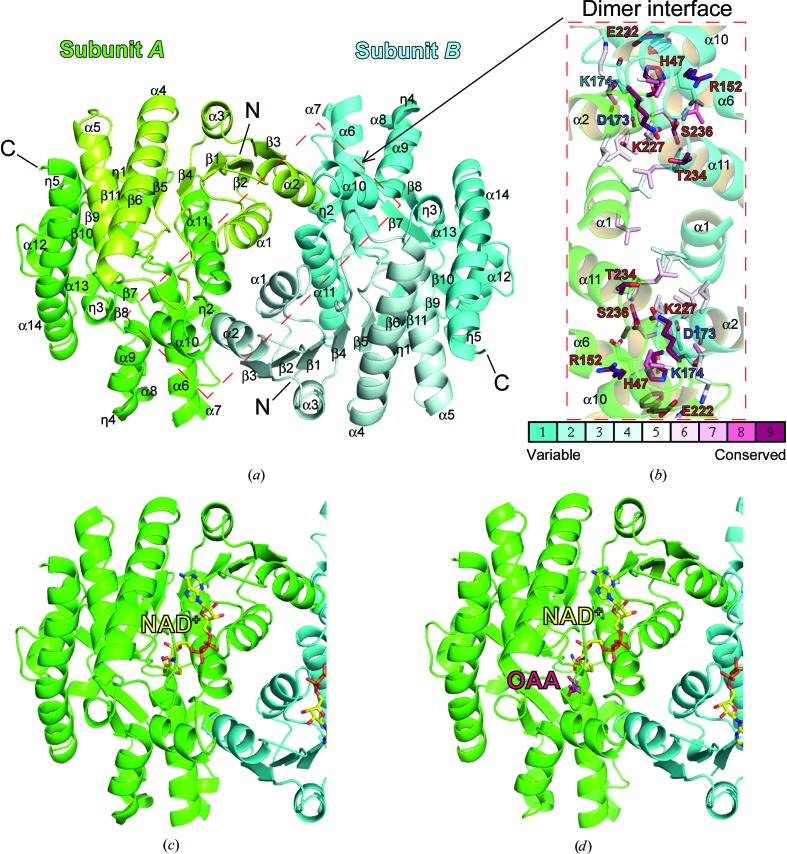

The structure of apo MDH3 was determined at 2.1 Å resolution by the molecular-replacement method using the structure of porcine mitochondrial MDH as a model (Fig. 3 ▸ a). The crystallographic asymmetric unit contained two subunits that formed a homodimer: subunit A (amino-acid residues 1–339) and subunit B (amino-acid residues 1–339). The overall structures of molecules A and B showed a root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 0.47 Å for 339 Cα atoms. Similar to other MDHs, MDH3 harbors an N-terminal NAD+-binding domain (amino-acid residues 1–145) and a C-terminal catalytic domain (amino-acid residues 146–339) and comprises 14 helices, 11 β-strands and five 310-helices. The N-terminal domain comprises a six-stranded parallel β-sheet (β1–β6) and five α-helices (α1–α5). The C-terminal domain contains the amino acids necessary for catalysis and the substrate-binding site, which comprises a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (β7–β11) surrounded by nine α-helices (α6–α14) (Fig. 3 ▸ a). The dimer interface mainly consists of interacting α-helices with an interface of approximately 1583.6 Å2, as calculated using the PISA web server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/prot_int/cgi-bin/piserver; Krissinel & Henrick, 2007 ▸). The dimeric interface of MDH3 contains 23 hydrogen bonds and extensive hydrophobic interactions. The catalytic residues and three-dimensional structures of the MDHs show considerable conservation, whereas a multiple sequence alignment of the MDHs shows a low similarity among different subcellular organelles (Fig. 2 ▸; Goward & Nicholls, 1994 ▸). The fundamental structure of the yeast MDH3 monomer was similar to those of the porcine mitochondrial (PDB entry 1mld; Gleason et al., 1994 ▸) and cytoplasmic (PDB entry 4mdh; Birktoft et al., 1989 ▸) MDHs, with r.m.s.d. values of 1.27 and 2.32 Å, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). In addition, the dimeric architecture and the structure of the interfaces were similar, and the charged polar amino-acid residues (for example histidine, arginine, lysine and glutamine) at the interface were conserved among the MDHs (Fig. 3 ▸ b).

Figure 3.

Structures of yeast apo MDH3 and the MDH3–NAD+ and MDH3–NAD+–OAA complexes. (a) Dimeric apo MDH3 with each monomer (subunits A and B) highlighted in a different color. α-Helices are labeled α1–α14, β-strands are labeled β1–β11, 310-helices are labeled η1–η5 and the N-terminal NAD+-binding domain is indicated in light colors. (b) Conservation of the amino-acid residues involved in the interaction between subunits A and B of the MDH3 dimer. Amino-acid residues contributing to interactions are represented by stick models. A total of 44 sequences of all types of MDH (mitochondrial, glyoxysomal and cytosolic) were analyzed using the ConSurf server (Ashkenazy et al., 2010 ▸). The conservation grades of amino-acid residues are indicated using a color-coded scale from turquoise to maroon. The residues with the highest and lowest conservation score in the interaction surface are labeled in red and blue, respectively. The sequences used for ConSurf analysis are listed in Supplementary Table S1. (c) Structure of the MDH3–NAD+ complex. (d) Structure of the MDH3–NAD+–OAA complex. NAD+ and OAA are shown as yellow and magenta sticks, respectively.

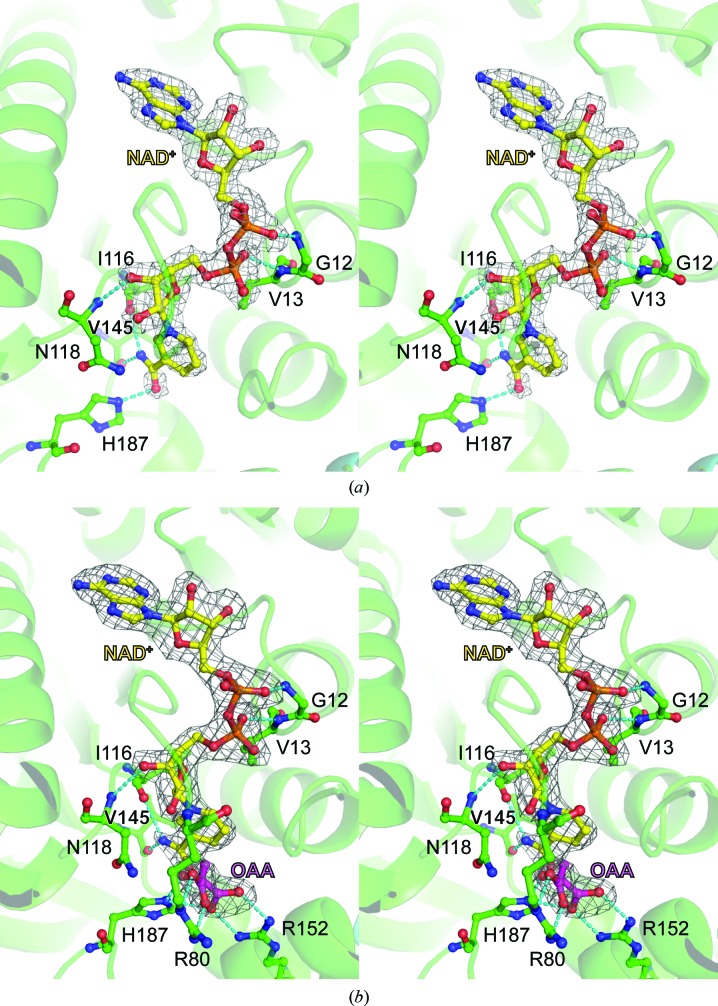

3.2. Structure of the MDH3–NAD+ complex

To understand the structural basis for the substrate binding of MDH3, apo MDH3 crystals were soaked with NAD+ and the structure of the MDH3–NAD+ complex was determined (Fig. 3 ▸ c). Unlike apo MDH3, the crystal structure of the MDH3–NAD+ complex belonged to space group P21 with one dimer in the asymmetric unit. In the NAD+-bound MDH3 dimer one monomer contained NAD+, whereas in the opposing monomer the nicotinamide portion of NAD+ was disordered in the difference electron-density map (Fig. 4 ▸ a and Supplementary Fig. S2). It is possible that the bound molecule is ADP, a hydrolysis product of NAD+. The overall structure of MDH3 in complex with NAD+ was highly similar to those of apo MDH3 (r.m.s.d. of 0.50 Å), human mitochondrial MDH (PDB entry 4wlv; Y. M. Eo, B. G. Han & H. C. Ahn, unpublished work) and porcine cytosolic MDH (Supplementary Fig. S3). In the MDH3–NAD+ complex, NAD+ was stabilized via hydrophobic interactions (between the adenine portion of NAD and MDH3) and hydrogen bonds to the amino acids lining the cofactor-binding pocket (between the nicotinamide and phosphate portions of NAD and MDH3), including Gly12, Val13, Ile116, Asn118, Val145 and His187 (Fig. 4 ▸ a and Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 4.

Stereoviews of the NAD+- and OAA-binding sites of MDH3. Close-up views of NAD+-bound MDH3 (a) and NAD+/OAA-bound MDH3 (b) are shown. NAD+ and OAA were modeled using an F o − F c OMIT electron-density map contoured at 3σ. Residues that are in contact with or form hydrogen bonds to NAD+ and OAA are indicated by stick models and dashed lines, respectively.

3.3. Comparison of the substrate-binding sites of MDHs

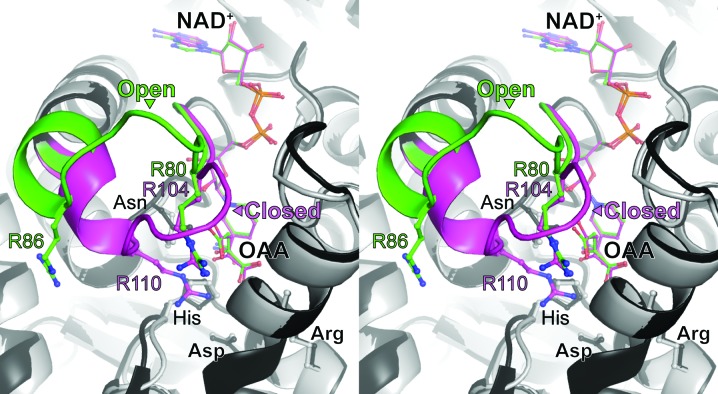

Previous analyses reported that the apparent K m value of MDH3 for OAA is higher than those of MDH1 and MDH2 (Steffan & McAlister-Henn, 1992 ▸). To investigate the structure of the substrate-binding mode of MDH3, we determined the structure of the MDH3–NAD+–OAA ternary complex at a resolution of 2.1 Å (Fig. 3 ▸ d). Electron-density maps for NAD+ and OAA were identified in the active-site cleft (Fig. 4 ▸ b). The active site of MDH3 contained a His–Asp pair (His187 and Asp149) that formed a charge-relay system. The positively charged amino acids Arg80, Arg152 and His187 in the binding site of MDH3 formed hydrogen bonds to OAA (Fig. 4 ▸ b). The residues located in the substrate-binding pocket were well conserved among MDHs (Fig. 2 ▸ and Supplementary Fig. S5). Crystal structures of ternary complexes involving MDH, NAD+ (or its derivatives) and the substrate (OAA or malate) have been reported previously. Open and closed conformations of the active-site loop have been determined in the MDH structures (Hall et al., 1992 ▸; Hall & Banaszak, 1993 ▸; Gleason et al., 1994 ▸; Bell et al., 2001 ▸; Cox et al., 2005 ▸; Zaitseva et al., 2009 ▸). Interactions between malate or a malate analog and the active site induce the closed conformation (PDB entries 4wlo, 4wlu and 2dfd; Y. M. Eo, B. G. Han & H. C. Ahn, unpublished work; Structural Genomics Consortium, unpublished work). While previously reported structures of MDH–substrate complexes show a closed conformation, the active-site loop showed an open conformation in MDH3 (Fig. 5 ▸). The amino-acid sequence of the active-site loop was highly conserved, and the conformation of OAA when bound to yeast MDH3 is similar to that when bound to human mitochondrial MDH (Figs. 2 ▸ and 5 ▸). The mechanism for the open conformation of the MDH3 active-site loop in the presence of the substrate is unclear. The different conformation of the active-site loop may be related to the affinity of MDH3 for OAA.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the open and closed conformations of the active-site loops in NAD+/OAA-bound MDHs. Stereoview of the active sites of human mitochondrial MDH (PDB entry 4wlo, black) and yeast MDH3 (gray). Active-site loops and ligands of human mitochondrial MDH and yeast MDH3 are highlighted in magenta and green, respectively. NAD+, OAA and highly conserved active-site residues are indicated using stick models.

4. Discussion

The functionally important residues in MDHs and lactate dehydrogenases (LDHs) are similar (Goward & Nicholls, 1994 ▸). LDHs reversibly catalyze the oxidation/reduction of lactate/pyruvate in the presence of NAD+/NADH as a coenzyme (Holbrook et al., 1975 ▸). In particular, the charge-relay system formed by the His–Asp pair in the active site is invariant; this suggests that MDHs and LDHs have a similar catalytic mechanism. The structure of LDH with/without a substrate analog revealed two different conformations: open and closed forms of the active-site loop (Piontek et al., 1990 ▸; Wigley et al., 1992 ▸). The movement of the active-site loop is correlated with the rate-limiting step in the reaction for LDH (Waldman et al., 1988 ▸). In MDHs the active-site loop has also been observed to undergo a conformational change to either open or closed depending on the substrate that binds (Hall et al., 1992 ▸; Hall & Banaszak, 1993 ▸; Gleason et al., 1994 ▸; Bell et al., 2001 ▸; Cox et al., 2005 ▸; Zaitseva et al., 2009 ▸); additionally, the sequence of the loop region in MDHs is highly conserved (Fig. 2 ▸). Comparing the MDH3–NAD+–OAA and human mitochondrial MDH–NAD+–OAA structures, the active-site loop formed an open conformation in MDH3 despite substrate binding. Two arginine residues in the active-site loop in human mitochondrial MDH (Arg104 and Arg110), which interact with OAA, and one of two arginines (Arg86) in MDH3 are located in a site opposite to that of OAA (Fig. 5 ▸ and Supplementary Fig. S5). In LDH, the corresponding residue to Arg86 in MDH3 plays a role in stabilizing the substrate transition state (Clarke et al., 1986 ▸). The lack of interaction between Arg86 and OAA may induce different properties that are required for binding to OAA between MDH3 and other yeast MDHs.

In summary, we determined the crystal structures of apo MDH3 and the MDH3–NAD+ and MDH3–NAD+–OAA complexes. Although the overall structure of MDH3 was very similar to those of porcine mitochondrial and cytosolic MDHs, we observed differences in the active-site loops. This work provides a structural basis for the function of MDH3.

5. Related literature

The following references are cited in the Supporting Information for this article: Krissinel & Henrick (2004 ▸) and Wallace et al. (1995 ▸).

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: MDH3, apo form, 5zi3

PDB reference: MDH3 complex with NAD+, 5zi2

PDB reference: MDH3 complex with NAD+ and oxaloacetate, 5zi4

Supplementary Table and Figures.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X18011895/nw5076sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

This work was performed using synchrotron beamline BL44XU at SPring-8 under the Cooperative Research Program of the Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University, Japan. Diffraction data were collected on Osaka University beamline BL44XU at SPring-8, Harima, Japan under proposal Nos. 2016A6643, 2016B6643, 2017A6753 and 2017B6753.

References

- Ashkenazy, H., Erez, E., Martz, E., Pupko, T. & Ben-Tal, N. (2010). Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W529–W533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bell, J. K., Yennawar, H. P., Wright, S. K., Thompson, J. R., Viola, R. E. & Banaszak, L. J. (2001). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31156–31162. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Birktoft, J. J., Rhodes, G. & Banaszak, L. J. (1989). Biochemistry, 28, 6065–6081. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A. R., Wigley, D. B., Chia, W. N., Barstow, D., Atkinson, T. & Holbrook, J. J. (1986). Nature (London), 324, 699–702. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cox, B., Chit, M. M., Weaver, T., Gietl, C., Bailey, J., Bell, E. & Banaszak, L. (2005). FEBS J. 272, 643–654. [DOI] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). PyMOL. http://www.pymol.org.

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gleason, W. B., Fu, Z., Birktoft, J. & Banaszak, L. (1994). Biochemistry, 33, 2078–2088. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gore, S. et al. (2017). Structure, 25, 1916–1927.

- Goward, C. R. & Nicholls, D. J. (1994). Protein Sci. 3, 1883–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hall, M. D. & Banaszak, L. J. (1993). J. Mol. Biol. 232, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hall, M. D., Levitt, D. G. & Banaszak, L. J. (1992). J. Mol. Biol. 226, 867–882. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, J. J., Liljas, A., Steindel, S. J. & Rossmann, M. G. (1975). The Enzymes, 3rd ed., edited by P. D. Boyer, Vol. 11, pp. 191–292. New York: Academic Press.

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2256–2268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J. (2007). Acta Cryst. D63, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Minard, K. I. & McAlister-Henn, L. (1991). Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 370–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Minárik, P., Tomásková, N., Kollárová, M. & Antalík, M. (2002). Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 21, 257–265. [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Piontek, K., Chakrabarti, P., Schär, H. P., Rossmann, M. G. & Zuber, H. (1990). Proteins, 7, 74–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pracharoenwattana, I., Cornah, J. E. & Smith, S. M. (2007). Plant. J. 50, 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Robertson, L. S. (2014). Am. J. Public Health, 104, 2256–2258.

- Roderick, S. L. & Banaszak, L. J. (1986). J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9461–9464. [PubMed]

- Roermund, C. W. van, Elgersma, Y., Singh, N., Wanders, R. J. & Tabak, H. F. (1995). EMBO J. 14, 3480–3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Steffan, J. S. & McAlister-Henn, L. (1992). J. Biol. Chem. 267, 24708–24715. [PubMed]

- Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. (1994). Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Waldman, A. D., Hart, K. W., Clarke, A. R., Wigley, D. B., Barstow, D. A., Atkinson, T., Chia, W. N. & Holbrook, J. J. (1988). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 150, 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wallace, A. C., Laskowski, R. A. & Thornton, J. M. (1995). Protein Eng. 8, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wigley, D. B., Gamblin, S. J., Turkenburg, J. P., Dodson, E. J., Piontek, K., Muirhead, H. & Holbrook, J. J. (1992). J. Mol. Biol. 223, 317–335. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zaitseva, J., Meneely, K. M. & Lamb, A. L. (2009). Acta Cryst. F65, 866–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: MDH3, apo form, 5zi3

PDB reference: MDH3 complex with NAD+, 5zi2

PDB reference: MDH3 complex with NAD+ and oxaloacetate, 5zi4

Supplementary Table and Figures.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X18011895/nw5076sup1.pdf