Abstract

Endometriosis implants are comprised of glandular and stromal elements, macrophages, nerves, and blood vessels and are commonly accompanied by pelvic pain. We propose that activated macrophages are recruited to and infiltrate nascent lesions, where they secrete proinflammatory cytokines, promoting the production of chemokines, neurotrophins, and angiogenic growth factors that sustain an inflammatory microenvironment. Immunohistochemical evaluation of endometriosis lesions reveals in situ colocalization of concentrated macrophages, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and nerve fibers. These observations were coupled with biochemical analyses of primary eutopic endometriosis stromal cell (EESC) cultures, which allowed defining potential pathways leading to the neuroangiogenic phenotype of these lesions. Our findings indicate that IL-1β potently (EC50 = 7 ± 2 ng/mL) stimulates production of EESC BDNF at the mRNA and protein levels in an IL-1 receptor–dependent fashion. Selective kinase inhibitors demonstrate that this IL-1β effect is mediated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), NF-κB, and mechanistic target of rapamycin signal transduction pathways. IL-1β regulation of regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), a prominent EESC chemokine, also relies on JNK and NF-κB. An important clinical implication of the study is that interference with BDNF and RANTES production, by selectively targeting the JNK and NF-κB cascades, may offer a tractable therapeutic strategy to mitigate the pain and inflammation associated with endometriosis.

Endometriosis is a debilitating gynecologic disorder characterized by the growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity, which commonly is accompanied by infertility and pelvic pain. A recent epidemiologic survey indicates that the overall prevalence of endometriosis among reproductive-age women is approximately 11%.1 From data extrapolated from the World Bank, it is estimated that >176 million women are affected globally.2 Careful estimates of annual health care expenses and loss of productivity secondary to endometriosis-associated pain averaged the equivalent of $11,300 in affected women from the United States and nine European nations.3 Endometriotic implants are commonly found on the pelvic peritoneal surface and penetrating the ovarian cortex, but the most symptomatic variant is deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) in which lesions invade the cul-de-sac and rectovaginal septum.4

The pathogenetic mechanisms that link endometriosis and pelvic pain remain unclear, although their association is clinically well established.5, 6 A prevailing immunocentric theory attributes inflammation through the recruitment of macrophages and other activated leukocytes from bone marrow to the endometriotic lesions by chemokines synthesized in situ.7, 8, 9 One of the postulated consequences of immune cell activation in the endometriosis microenvironment is the elaboration of cytokines, growth factors, and eicosanoids that simultaneously stimulate lesion innervation and neovascularization through a coordinated mechanism that was coined neuroangiogenesis.10 Eutopic endometrial tissues from women with endometriosis were found to have significantly higher nerve density than those from unaffected control participants.11, 12 In an agnostic proteomic screen of factors that stimulate nerve growth, endometrial brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression was increased more than eightfold in women with endometriosis.13 Circulating serum BDNF concentrations also are reported to be significantly (1.5-fold) higher in cases than in controls.14 In keeping with the theory of neuroangiogenesis, BDNF is known to be trophic both for nerves and capillaries.15, 16

In the present studies we set out to test the hypothesis that macrophages in the endometriosis microenvironment may contribute to neuroangiogenesis by secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Tissue macrophages, BDNF, and nerve fibers were colocalized in DIE lesions, and a primary cell culture model from subjects with endometriosis-associated pain was used to address the mechanisms by which macrophage-derived cytokines may induce BDNF mRNA and protein expression in eutopic endometriosis stromal cells (EESCs). The findings support the concept that cytokine cross talk among heterogeneous cell types in endometriosis lesions can lead to the recruitment of vessels and nerves, supporting lesion vascularization, survival, invasion, and nociception.

Materials and Methods

Source of Human Tissues

Eight patients undergoing laparoscopy provided written informed consent under study protocols approved by the institutional review boards at Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, and the Health Sciences School, Universidade do Vale do Sapucaí, Pouso Alegre, Minas Gerais, Brazil. All of the patients had regular menstrual cycles, had not received hormonal therapy for at least 3 months before surgery, and were undergoing laparoscopy for evaluation and treatment of pelvic pain. Six of the eight patients were nulligravid and all eight reported dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia. Immediately before laparoscopy, eutopic endometrial biopsies were collected by Pipelle aspiration under sterile conditions in five of the patients, and these were promptly transported to the laboratory on ice in phosphate-buffered saline. At laparoscopy, a thorough visual inspection of the pelvic cavity was performed by experienced gynecologic surgeons familiar with the appearance of typical and atypical endometriotic lesions. Intraoperative excisional biopsies from all eight patients (some of whom had multiple lesion types) confirmed the presence of histopathologic endometriosis (ie, endometrial glands, stroma, and hemosiderocytes). Five of the patients met criteria for DIE, and each had a single, dominant nodular lesion that involved the sigmoid colon, rectovaginal septum, or uterosacral ligament with invasion >5 mm. The clinical characteristics and intraoperative revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine endometriosis staging17 of the participants are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study Participants

| Age, years | Gravity/parity | Phase (d) | rASRM stage | Symptoms | Lesion locations | DIE | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 0/0 | Prolif (8) | IV | Pain/infertility | Sig nodule | Yes | IHC |

| 31 | 1/1 | Prolif (1) | IV | Pain/infertility | Vag nodule | Yes | IHC |

| 33 | 0/0 | Prolif (11) | IV | Pain/infertility | Vag nodule | Yes | IHC |

| 31 | 0/0 | Prolif (9) | IV | Pain/infertility | Sig nodule | Yes | IHC/CX |

| 31 | 2/1 | Prolif (6) | III | Pain | Perit/L ov | No | CX |

| 36 | 0/0 | Prolif (10) | II | Pain | L tube, ov | No | CX |

| 35 | 0/0 | Prolif (8) | IV | Pain/infertility | R ov, vag nodule | Yes | CX |

| 23 | 0/0 | Prolif (5) | II | Pain/infertility | Perit/R ov | No | CX |

CX, cell culture; d, cycle day; DIE, deep infiltrating endometriosis; IHC, immunohistochemistry; L, left; ov, ovary; perit, peritoneal implant; prolif, proliferative phase of menstrual cycle; R, right; rASRM, revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine endometriosis stage; sig, sigmoid; study, protocol; vag, vaginal.

IHC

Paraffin-embedded nodular DIE lesions from each of four participants were sectioned 4- to 5-μm thick and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC) as described previously18, 19 with some modifications. After mounting, the slides were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded concentrations of ethanol, and endogenous hydrogen peroxide was quenched in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Primary antibodies to CD68 (macrophages; catalog number M0876; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), BDNF (neurotrophic factor; catalog number 3160-1; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA), and PGP9.5 (nerve fibers; catalog number Z5116; Dako) were diluted to 1:50, 1:100, and 1:200, respectively, in Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.5% casein as a blocking reagent. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies. For heat-induced epitope retrieval, slides were incubated in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 4 minutes in a pressure cooker. Biotinylated secondary Fc antibody was used as a linking reagent for all antibodies, and alkaline-phosphatase–conjugated streptavidin (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) was applied for labeling. The chromogen was Vector Red Substrate (kit number 1; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), diluted in Tris (pH 8.2 to 8.5), and applied to slides for 5 to 10 minutes at 30°C to 35°C. Mild counterstaining with Mayer's hematoxylin was performed. Negative staining controls were performed by omitting the primary antibody and substituting nonimmune IgG (BioGenex). For positive controls, myenteric plexi from small intestine were evaluated by using the same reagents (data not shown).

EESC Cultures

Eutopic endometrial biopsies for EESC cultures were performed in five of the patients (three without and two with DIE) (Table 1), all undergoing operation during the early–mid-proliferative phase (menstrual days 5 to 10) of the cycle to avoid effects of endogenous luteal progesterone. In our experience, the success of culture establishment and consistency of cell growth rates are menstrual cycle–specific and optimal when proliferative phase biopsies are obtained.20 Tissue fragments were used to prepare EESC cultures, as described.20, 21 Briefly, after collagenase digestion, glandular epithelial cells and debris were separated from EESCs by filtration through 200-μm and 40-μm sieves. EESCs were subcultured at least twice to eliminate contamination by macrophages or other leukocytes and were used before the sixth passage to avoid dedifferentiation. Prior studies from our laboratory confirmed that the EESCs are >95% pure and retain functional estrogen, progesterone, and other nuclear receptors, as well as phenotypic endometrial markers, for at least five passages in vitro. The cells were grown to 60% to 80% confluence in 10-cm dishes with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/Ham's F-12 50:50 Mix media (catalog number 10-092CV; CellGro, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Some cells were incubated with up to 100 ng/mL IL-1β, which corresponds to the EC90 for IL-6 secretion by normal endometrial stromal cells.22 Replicate cultures from each patient were prepared. Representative examples are shown, and the number of experiments performed with EESCs from independent patients is indicated.

Quantification of Cell Shape

EESC morphology was assessed by phase-contrast microscopy to determine cell shape, using a modified calculation of cell roundness23 as described previously,19 whereby an index of 1.0 = round.

IFC

To corroborate and localize the cellular distribution and expression of BDNF and c-Rel (a p65 component of the NF-κB complex), intact EESCs from three patients grown on Lab-Tek chamber slides before and after recombinant IL-1β exposure (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were analyzed. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and cold acetone. Immunofluorescence cytochemistry (IFC) was performed on an EVOS cellular imaging microscope (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Quantification of BDNF from IFC staining intensity was determined by using Image J software version 1.46r (NIH, Bethesda, MD; https://imagej.nih.gov/ij) to assess pixel counts per micrometer squared.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analyses were performed on whole-cell extracts, obtained by using a vortex to mix EESCs in extraction buffer (catalog number FNN0011; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Total proteins (20 to 60 μg per lane, determined with the Thermo Scientific-Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit; catalog number PI-23227; Thermo-Fisher Scientific) were run on NuPAGE Novex 4% to 12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and blocked with 5% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline. BDNF was detected by using mouse monoclonal anti-BDNF antibodies (dilution 1:250; catalog number ab10505; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The BDNF bands were detected after incubation with secondary antibody linked to horseradish peroxidase and visualized by chemiluminescent detection and exposure to enhanced chemiluminescence hyperfilm (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Three dominant bands were observed, corresponding to an N-glycosylated and glycosulfated pro-BDNF precursor (32 kDa), a 28-kDa dimer, and the mature 14-kDa product of BDNF processing.24 When anti-BDNF antibodies were immunoabsorbed with excess recombinant BDNF, the signals of all three isoforms were abrogated, validating antibody specificity. Blots were washed, reprobed with mouse monoclonal anti–β-actin antibodies (dilution 1:1000; catalog number 31430; Sigma-Aldrich), and developed in an identical manner to ensure even loading. Molecular weight standards were used to calibrate the migration of immunopositive bands.

Western blot analyses of EESCs also were evaluated by using antibodies specific for proteins and phospho (p)-peptides corresponding to critical signaling pathways that have previously been characterized for IL-1β signaling in normal endometrial stromal cells.22 p–c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (catalog number 4668), p-SEK1 (catalog number 4514), p-ATF2 (catalog number 5112), p–c-Jun (catalog number 2361), Ras (catalog number 3339), p-mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR; Ser2448) (catalog number 5536), Raptor (catalog number 2280), and Rictor (catalog number 2114) antibodies (all diluted 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) were used to identify the predominant signaling mechanism(s) after IL-1β administration. Films were digitized on a flatbed scanner, and Image J was used to quantify the intensity of each band. Data are presented as the ratio of BDNF or p-peptide density/β-actin density of three cell preparations.

Kinase Inhibitor Experiments

IL-1ra, a natural inhibitor of type I and II IL-1 receptors,25 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and used as described previously.22 NF-κB inhibitory peptides and selective kinase inhibitors were used to validate the signaling pathways activated by IL-1β treatment. SN50 (catalog number 481480; EMD-Millipore, Burlington, MA) blocks translocation of NF-κB. The inert (mutated) analogue SN50M was used as a negative control. PD98059 [extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) inhibitor)], SB203580 [p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor], and SP600125 (JNK inhibitor) were from Sigma-Aldrich (catalog numbers P215, S8307, and S5567, respectively); rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (catalog number 9904). In all of the experiments that used various kinase and NF-κB inhibitors, the inhibitory peptides or compounds were added to the cultures 1 hour before the addition of IL-1β; the latter was allowed to incubate for up to 24 hours before termination of the studies.

RNA Isolation and qPCR

Three independent endometriosis-derived EESC preparations were evaluated by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR). EESCs were incubated without or with IL-1β for 24 hours as described in the section above. Total RNA was isolated from the cells by using TRI-reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol and frozen at –80°C until analyzed. cDNA was synthesized from mRNA samples and subsequently used as template for qPCR assays.

For qPCR, the SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix reagent (catalog number 1725271; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) was used, the vendor guidelines were followed with some modifications, and BDNF primers were validated. A total reaction volume of 20 μL contained 10 μL of SYBR Green, primer mix 2 μL, 1 μL of 50 mmol/L MgCl2, 2 μL of H2O, and 5 μL of cDNA. The PCR was set for 40 cycles in a CFX real-time thermocycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories). These data were analyzed after normalization with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels, using the formula 2ΔΔct, where ct is the cycle threshold.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted [RANTES; or chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5], a prominent monocyte chemokine in endometriosis,26 was measured with the use of a specific and sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems) that was previously validated for EESC culture supernatants.27, 28

Statistical Analysis

The IHC, IFC, and Western blot images are from representative specimens and cell preparations, and each result was replicated in tissues or cells from a minimum of three independent patients. The sample size was estimated from previous empirical studies with the use of cell cultures derived from endometriosis patients.21 BDNF pixel counts were determined in five high-power fields from three independent cell cultures by IFC in EESCs grown on chamber slides. BDNF protein levels in EESC lysates on Western blot analyses were normalized to β-actin digitized band densities from three independent cell preparations. These data were normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), and results are presented as means ± SEM. Comparisons were determined with the use of paired t-tests. Dose responses to IL-1β of BDNF mRNA levels normalized to GAPDH mRNA were determined from 2ΔΔct calculations and were compared by analysis of variance. Statistical significance for all of the analyses was accepted when two-tailed tests yielded P < 0.05 between the treatment groups.

Results

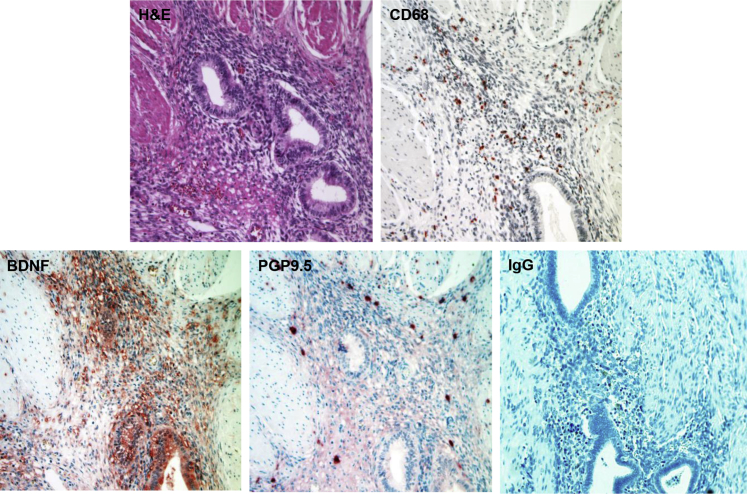

IHC Colocalization of Macrophages, BDNF, and Nerve Fibers in DIE in Situ

To document the coordinated spatiotemporal coincidence of macrophages, neurotrophins (NTs), and nerve fibers, a series of IHC experiments were performed on nodular DIE lesions. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section is provided for orientation (Figure 1) that revealed a focus of DIE invading striated muscle of the pelvic floor and rectovaginal septum. Tissue macrophages were identified by IHC for the low-density lipoprotein scavenger receptor CD68, whose antibodies revealed CD68+ macrophages scattered throughout the endometriosis stroma, being relatively spared in the endometriotic epithelial compartments and the investing rectovaginal muscularis (Figure 1). Specific BDNF immunostaining was identified in adjacent sections, predominantly localized in the glandular and stromal compartments of the DIE lesion, but not in the surrounding muscle tissue (Figure 1). PGP9.5+ nerve fibers were seen coursing through the stroma of the DIE lesion. Most of these fibers were viewed en face relative to the orientation of this DIE implant (Figure 1). Nonimmune IgG was used as a negative control (Figure 1). Similar distributions of CD68+, BDNF+, and PGP9.5+ cells were observed in DIE biopsies from all four independent patients evaluated by IHC. The histologic findings supported the concept that macrophage–stromal cell cross talk within endometriosis lesions could result in the elaboration of neurotrophic signals and recruitment of nociceptive nerves. A well-established, primary EESC culture model20, 21, 27 was used to test this hypothetical mechanism.

Figure 1.

Histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) lesion. Biopsies of DIE lesions were collected as described and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), CD68 (anti-macrophage), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; anti-neurotrophin), PGP9.5 (anti-nerve fibers) antibodies, or nonimmune IgG as a negative control. Note that nerve fibers in the bottom middle panel are mostly viewed en face relative to the orientation of the DIE implant. Similar IHC findings were observed in all four patients with dominant DIE nodules. Original magnification, ×200.

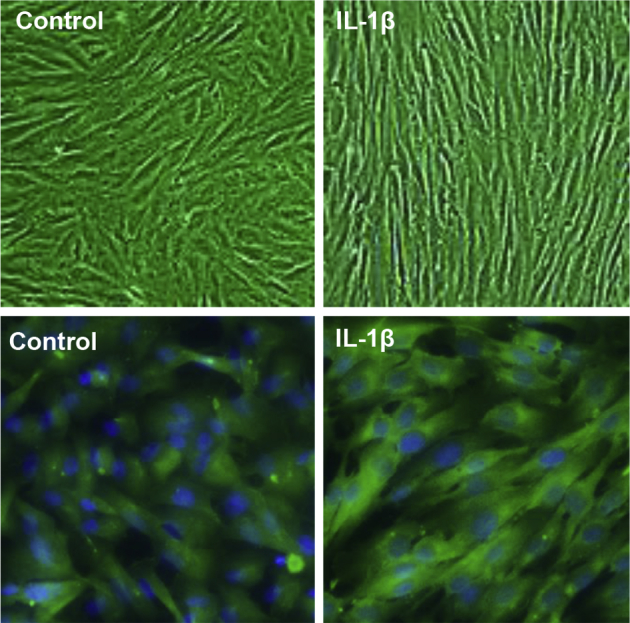

IL-1β Induces Morphologic Changes and Stimulates BDNF Production in Primary EESC Cultures

IL-1β is a potent proinflammatory cytokine synthesized by macrophages, whose concentration and activity were reported to be excessive in endometriosis.29, 30 Tissue macrophages infiltrating the endometrial stroma22 and peritoneal macrophages31 were rich sources of IL-1β, and EESCs were particularly sensitive to IL-1β.30, 32 In the present study it was noted that 24-hour treatment with 10 ng/mL recombinant IL-1β induced a compact fibroblastic morphology in EESCs derived from endometriosis patients. Under phase-contrast microscopy the IL-1β–treated cells revealed a tight, bipolar shape with parallel orientation compared with untreated EESCs (Figure 2). The cell shape index, calculated in three independent cell preparations, was significantly reduced (from 0.29 ± 0.06 to 0.10 ± 0.02) after IL-1β treatment (P < 0.02). Moreover, incubation with IL-1β up-regulated the expression of cytoplasmic BDNF by threefold as assessed by IFC pixel counts (from 220 ± 10 to 661 ± 23 pixels/μm2; P < 0.01; n = 3) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

IL-1β–induced changes in endometriosis stromal cell (ESC) morphology and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression. Eutopic endometriosis stromal cells (EESCs) were cultured in complete medium without (control) or with recombinant 10 ng/mL IL-1β for 48 hours (+IL-1β) and visualized under phase-contrast microscopy. Cell shape indices measured as described in the text revealed that IL-1β treatment significantly reduced cell roundness. EESCs grown under identical conditions on chamber slides were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and cold acetone and stained by immunofluorescence cytochemistry with anti-BDNF antibodies (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). BDNF pixel counts were significantly reduced in IL-1β–exposed EESCs. n = 4 for cell shape; n = 3 IL-1β–exposed EESCs. Original magnification, ×400.

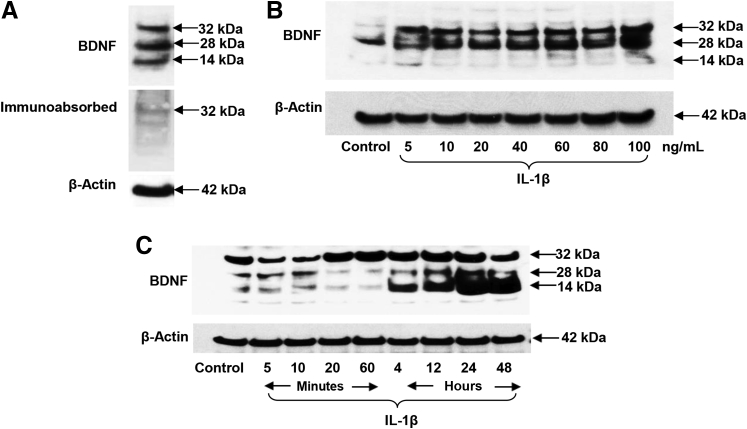

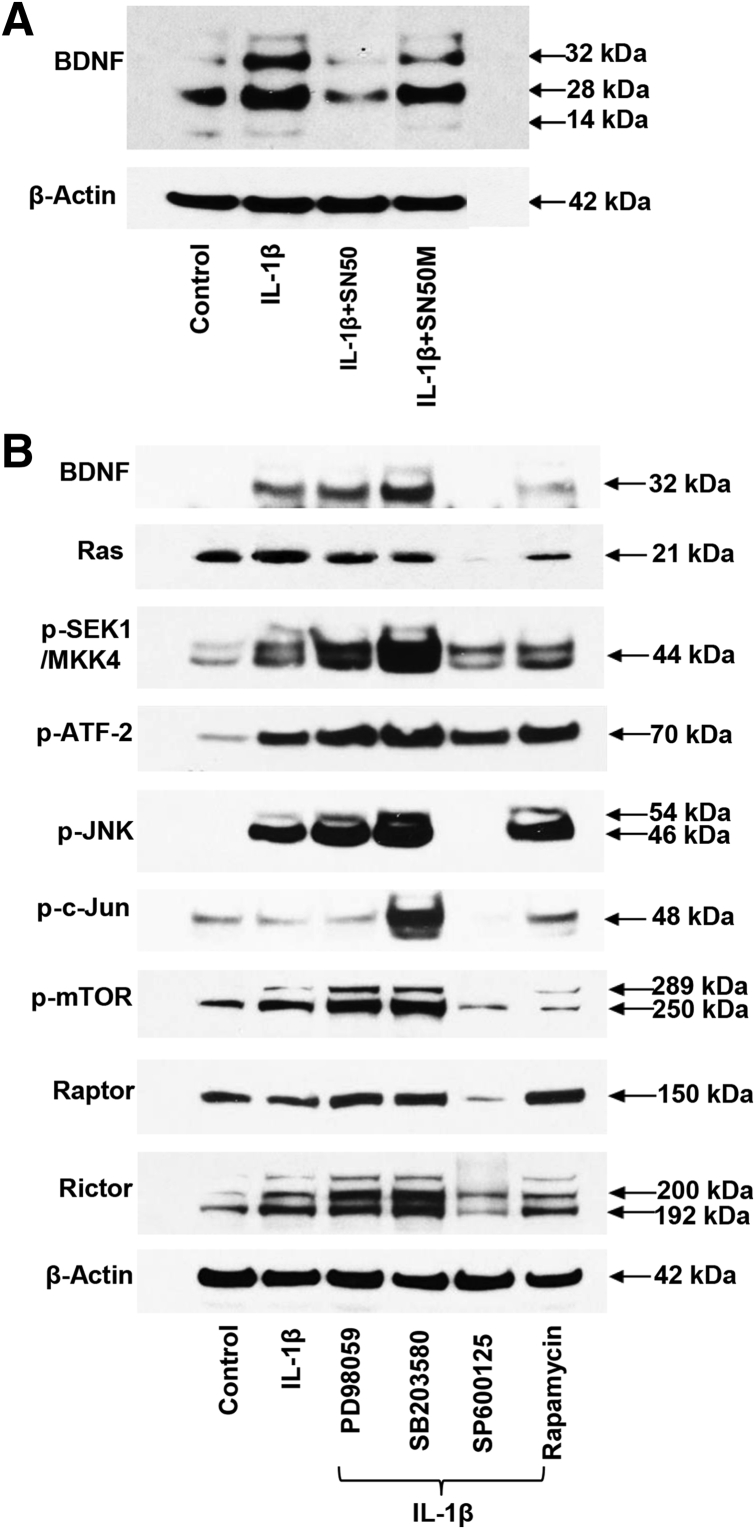

Western Blot Analysis Reveals Multiple Molecular Forms of BDNF in EESC Lysates

BDNF molecular species of 32, 28, and 14 kDa were resolved in Western blot analyses of EESC lysates by using a specific mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog number 10505; Abcam) and immunoabsorption of the antibody with excess recombinant BDNF antigen validated that all three bands are bona fide isoforms representing a precursor (32 kDa), dimer (28 kDa), and the full-length, mature BDNF protein (14 kDa) (Figure 3A). Dose–response experiments were performed after incubation with 0 to 100 ng/mL IL-1β for 24 hours. BDNF precursor isoforms were predominate and nearly maximal stimulation was achieved with 10 ng/mL IL-1β (Figure 3B). Time–course experiments indicated that synthesis and processing to the mature 14-kDa BDNF was temporally dependent, increasing progressively from 5 minutes to 48 hours after incubation with 10 ng/mL IL-1β (Figure 3C). Levels of β-actin (42 kDa) were evaluated as an internal control, and these remained stable under the dose–response and time–course conditions. Some interindividual EESC variability was noted in terms of differential BDNF isoform predominance, but to assess reproducibility among independent experiments with the use of cells from three different endometriosis patients, laser densitometry quantification of the combined 32-, 28-, and 14-kDa bands, normalized to β-actin, was used. The results indicated that 10 ng/mL IL-1β for 24 hours increased BDNF isoforms 6.4- ± 1.8-fold over untreated EESCs, respectively [P = 0.04 (t-test); n = 3].

Figure 3.

Western blot analyses revealed multiple isoforms and IL-1β–induced changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein expression in eutopic endometriosis stromal cells (EESCs). A: Immunoblotting of EESC lysates with anti-BDNF antibodies revealed three prominent bands (32, 28, and 14 kDa), each of which was dramatically reduced when the antisera was preabsorbed with an excess of recombinant BDNF. B and C: Dose–response (B) and time–course (C) experiments indicate that BDNF precursors (32 kDa, 28 kDa) and processed (14 kDa) species were responsive to IL-1β treatment. In independent EESC experiments, normalized to β-actin as an internal constitutive control, IL-1β for 24 hours induced a 6.4-fold increase in BDNF. n = 3 independent EESC experiments.

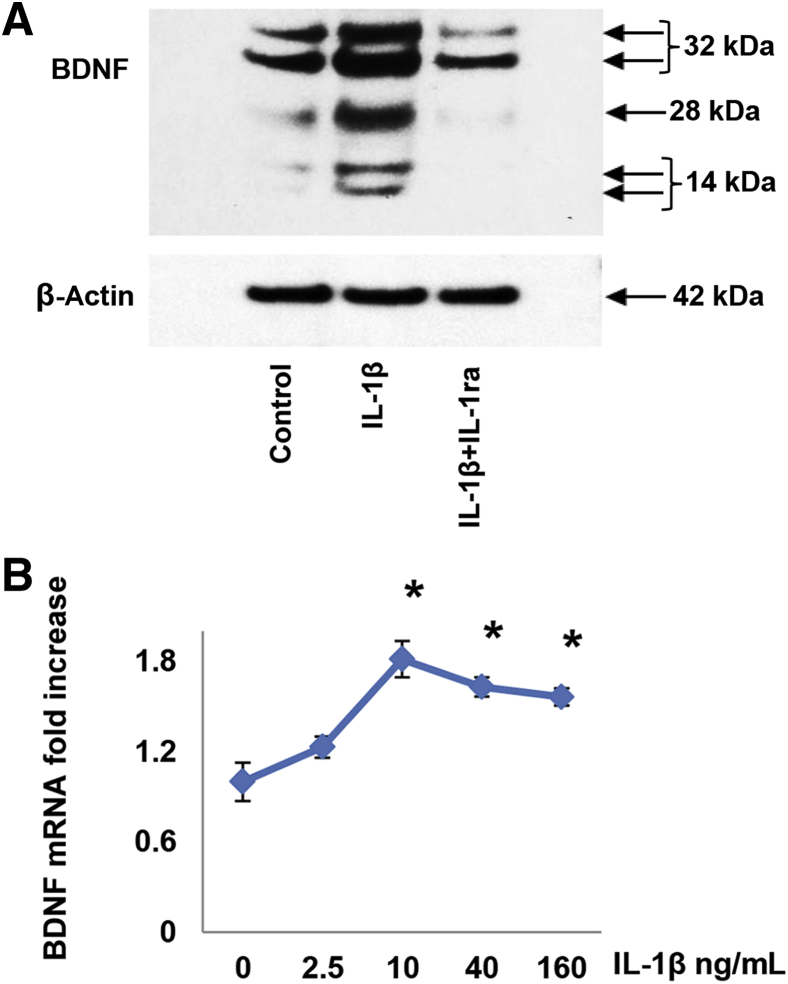

IL-1β Effects on BDNF in EESCs Are Mediated by IL-1 Receptor

To characterize the mechanism of IL-1β on BDNF production and to verify that the effect was receptor mediated, experiments were performed in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of recombinant IL-1ra, an endogenous inhibitor of IL-1 type I and II receptors.25, 33 Although IL-1ra alone had no effect on basal BDNF levels (data not shown), IL-1ra neutralized the IL-1β–mediated stimulation of all three major isoforms of BDNF (Figure 4A). β-Actin levels were not altered (Figure 4A). Preincubation with IL-1ra also prevented the fibroblastic morphology induced by IL-1β and completely inhibited up-regulation of RANTES as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (IL-1β Regulates RANTES in EESCs by IL-1 Receptor, NF-κB, and JNK Pathways). When the gels were over-run, resolution of the 32- and 14-kDa bands into doublets was noted (Figure 4A). Similar findings were obtained in three independent EESC preparations.

Figure 4.

IL-1β–induced changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were mediated through the IL-1 receptor and occurred, in part, at the level of mRNA expression (real-time quantitative PCR). Eutopic endometriosis stromal cells (EESCs) were preincubated with 1 μg/mL IL-1ra for 1 hour before stimulation with 10 ng/mL IL-1β. A: IL-1ra neutralized the stimulation of BDNF by IL-1β. When the gels were over-run, resolution of the 32- and 14-kDa bands into doublets was noted. All three major isoforms were affected. β-Actin levels were not altered. Similar findings were noted in independent EESC preparations. B: Triplicate EESC cultures were incubated for 24 hours in the presence of 0 to 160 ng/mL recombinant IL-1β. Total RNA extracted from the cultures was reverse transcribed and subjected to quantitative PCR amplification. The BDNF data were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA levels, using the formula 2ΔΔct. Similar findings were noted in independent EESC preparations. n = 3 independent EESC preparations (A and B). ∗P < 0.05 versus control (analysis of variance with Scheffé’s post hoc test).

Regulation of BDNF Production by IL-1β Is Mediated, in Part, at the Level of mRNA Accumulation

To understand the molecular mechanisms by which IL-1β regulated BDNF synthesis, qPCR was used to analyze steady-state BDNF mRNA concentrations in the EESC cultures. A representative dose–response experiment is shown in Figure 4B, corroborating the concentration optimum of 10 ng/mL IL-1β, with a 1.6- to 1.8-fold increase in BDNF mRNA levels over untreated EESCs (P < 0.05, analysis of variance). Comparable results were observed in repeated experiments with the use of cells derived from two additional patients. The three independent cell preparations yielded an EC50 of 7 ± 2 ng/mL (means ± SEM) for IL-1β on BDNF mRNA accumulation.

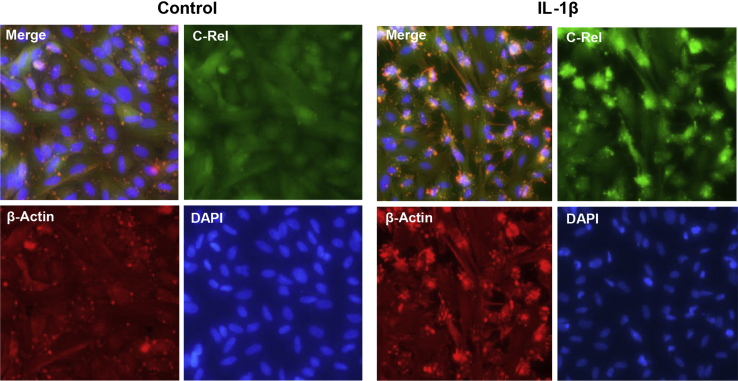

NF-κB and JNK Signaling Pathways Transduce IL-1β Action on BDNF in EESCs

The classic and most widely appreciated signal transduction mechanism of IL-1β was mediated by the NF-κB pathway. A tripartite complex of proteins (IκB, c-Rel, and p50) were typically sequestered as inactive cytoplasmic trimers. IL-1β stimulation of the type I IL-1 receptor resulted in rapid IκB phosphorylation, ubquitination, and proteasomal degradation, allowing c-Rel/p50 dimers to be translocated into the nucleus where they activated inflammatory genes by cis-acting activator protein-1 transcriptional elements,34 as well as several other canonical signaling cascades.22 IFC with antibodies specific for c-Rel demonstrated that within 20 minutes of IL-1β exposure, this protein was shuttled from the EESC cytoplasm to the nucleus (Figure 5). The concomitant rearrangement of β-actin (Figure 5) was associated with the phase-contrast morphologic changes noted in Figure 2. Distribution of cell nuclei was visualized by DAPI staining (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence cytochemistry (IFC) confirmed nuclear translocation of c-Rel after IL-1β treatment. IFC in eutopic endometriosis stromal cell (EESC) monolayers showed diffuse cytoplasmic localization of c-Rel under control conditions (green signal). Twenty minutes after IL-1β exposure, c-Rel became associated with the cell nuclei. DAPI (blue signal) was used to highlight cell nuclei. Similar findings were noted in independent EESC preparations. n = 3 independent EESC preparations. Original magnification, ×400.

In Western blot analyses, the stimulatory effect of IL-1β treatment on BDNF precursors was completely blocked by co-incubation with the NF-κB inhibitor peptide SN50, but much less so by the mutated (inactive) peptide SN50M (Figure 6A). These data supported the NF-κB pathway as playing a role in IL-1β–induced BDNF synthesis.

Figure 6.

IL-1β–induced increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein expression was attenuated by SN50 and by selective kinase inhibitors. A: Eutopic endometriosis stromal cells (EESCs) cultured for 24 hours with IL-1β showed an up-regulation of 32- and 28-kDa BDNF isoforms (lane 2) that was blocked by preincubation with the NF-κB inhibitory peptide SN50 (lane 3). The inert, mutant peptide SN50M has minimal effect on IL-1β–induced increase in BDNF (lane 4). Similar findings were noted in independent EESC preparations. B: EESC lysates treated with IL-1β revealed an increase in pro-BDNF (32 kDa) that was accompanied by increased phospho (p)-SEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MKK)4, p–activating transcription factor (ATF)-2, p–c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p–mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), and Rictor. No effects on Ras, p–c-Jun, Raptor, or β-actin levels were noted. Among the selective kinase inhibitors co-incubated with IL-1β, the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, and to some extent the mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) most profoundly blocked the IL-1β effects. The p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, enhanced BDNF and particularly p-SEK/MKK4, p-JNK, and p–c-Jun expression, possibly by shunting IL-1β into the JNK or mTOR pathways. β-Actin levels were unchanged. Similar findings were observed in independent EESC preparations. Overall, kinase inhibitors suppressed IL-1β–induced BDNF by 34% ± 5% (P < 0.02). n = 2 independent EESC preparations (A); n = 4 independent EESC preparations (B).

In addition to NF-κB, IL-1β can use four alternative signal transduction pathways: ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, JNK, and mTOR.22 With the use of selective inhibitors to each of these four cascades (PD98059, SB203580, SP600125, and rapamycin, respectively) it was tested which, if any, alternate pathway(s) also might be downstream of IL-1β action on BDNF expression in EESCs. Western blot analyses revealed that IL-1β–induced up-regulation of BDNF precursor was profoundly inhibited by SP600125 and to a lesser extent by rapamycin (Figure 6B). The JNK inhibitor also reduced expression of p-JNK, p–c-Jun, and the mTOR complex–associated proteins Raptor and Rictor (Figure 6B). β-Actin levels were not affected (Figure 6B). Overall, these kinase inhibitors suppressed IL-1β–stimulated BDNF expression by 34% ± 5% (P < 0.02; n = 4 independent experiments). The findings demonstrated that the JNK and mTOR pathways also contributed to the IL-1β–mediated increase in BDNF precursor expression. Curiously, the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 appeared to augment BDNF, p-SEK1, p–c-Jun, and Rictor levels, possibly by shunting IL-1β action away from MAPK and down the JNK pathway (Figure 6B). Future studies are needed to understand the latter effect.

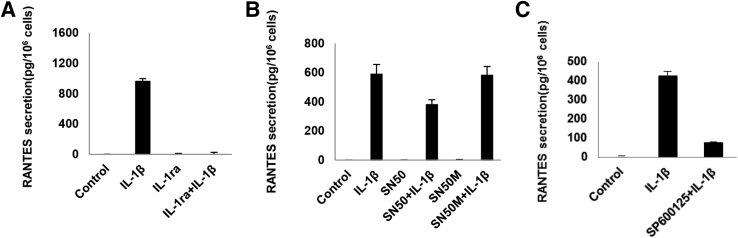

IL-1β Regulates RANTES in EESCs by IL-1 Receptor, NF-κB, and JNK Pathways

As a validation of these findings, another established downstream effect of IL-1β, the induction of chemokine secretion, was investigated. An exemplar β-chemokine that was characterized extensively in EESCs was RANTES [chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5].35, 36 This protein was involved in the recruitment and activation of macrophages and participated in a feed-back loop regulating the inflammatory microenvironment in endometriosis.29, 37 Preincubation with a 100-fold molar excess of IL-1ra completely prevented RANTES secretion after IL-1β treatment (Figure 7A), verifying that this response was an IL-1 receptor–mediated effect. A 34% suppression of IL-1β–induced RANTES was observed with the NF-κB inhibitor SN50, but there was no inhibition (<2%) with the inert peptide SN50M (Figure 7B). SP600125 inhibited the IL-1β–induced effects on RANTES by 79%, indicating that the JNK pathway may be the most critical regulator of the effect of IL-1β on this inflammatory EESC chemokine (Figure 7C). These findings were corroborated in three independent cell cultures.

Figure 7.

IL-1β–induced changes in regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted [RANTES; chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5] secretion. Triplicate eutopic endometriosis stromal cell (EESC) cultures were incubated for 24 hours without (control) or with IL-1β. A: Preincubation with a 100-fold molar excess of IL-1ra completely prevented IL-1β–induced RANTES secretion. B: Preincubation with the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 afforded a 34% suppression of IL-1β–induced RANTES, but there was no inhibition (<2%) with the inert peptide SN50M. The c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) blocker, SP600125, inhibited IL-1β–induced effects on RANTES by 79% [P < 0.05, analysis of variance with Scheffé’s post hoc test (all conditions were different from IL-1β except SN50M + IL-1β)] (C). Similar findings were noted in independent EESC preparations. n = 3 independent EESC preparations (C).

Discussion

In one of its earliest descriptions in the English literature, pain was recognized as a dominant symptomatic feature of endometriosis.38 According to the original report by Sampson,38 among the first 17 surgical cases, 12 had intolerable pelvic pain. The next year, Meigs39 identified extravasating endothelial leukocytes in microscopic analyses of endometriosis lesions, documenting for the first time that endometriosis is an inflammatory disorder. Gradually, observations of macrophage accumulation,40 chemokines in peritoneal fluid and lesions,27 and ultimately networks of interacting immune regulators discovered through the lens of systems biology have served to elucidate the pathogenesis of endometriosis.37 Increasingly, molecular and cellular studies reveal that innate immunocytes are critical modulators of multicellular endometriosis lesions. Current studies of selective macrophage polarization in endometriosis9 promise to provide an even more sophisticated understanding of immune cell function as a modulator of pain sensation in endometriosis.

In 2005, Berkley et al41 published a provocative article that described the growth of efferent sympathetic and afferent sensory nerves into surgically induced ectopic implants of a rat endometriosis model. Peripheral pain sensation and central sensitization are becoming recognized as pathophysiological mechanisms of clinical endometriosis-associated pain.5, 42 Microscopic studies have documented nerve fibers in human endometriotic peritoneal implants11 and particularly in DIE lesions,43, 44 which provide a plausible explanation for the pain symptoms that accompany endometriosis.12, 45

Limited studies of neurogenesis in endometriosis have been performed, but nerve growth factor (the first identified and most widely studied NT46), NT-3, NT-4/5, and BDNF mRNA were all identified in ovarian endometriomas of women with advanced stage endometriosis and pain.47 With the use of an unbiased clinical proteomics and immunoassay approach, it was observed that BDNF was the predominant endometrial NT, and its concentrations in eutopic biopsies among subjects with endometriosis were more than eightfold higher than in endometriosis-free controls.13 The endometrium of women with endometriosis also expresses elevated levels of the tyrosine receptor kinase B receptor,48 which preferentially binds NT-4/5 and BDNF, and circulating serum BDNF concentrations were found to be significantly (1.5-fold) greater in endometriosis subjects14 and correlate with pelvic pain severity in some studies.49

The present studies were undertaken to test the hypothesis that proinflammatory factors within the endometriosis tissue microenvironment contribute to the neuroangiogenic milieu by promoting neuroinflammation. IL-1β, a macrophage-derived cytokine known to be prevalent in endometriosis that manifests an array of biological activities long associated with endometriosis pathology,50, 51 including nociception,52 was studied. The salient findings in this article are that IL-1β exerts dose-dependent and temporal effects on EESCs from subjects with endometriosis, including an aggressive inflammatory, fibroblastic morphology in vitro, and up-regulation of BDNF mRNA and protein expression. These effects are mediated through the IL-1 receptor, because preincubation with an excess of IL-1ra blocks the response.

IL-1β inhibits cell differentiation and gap junction formation predominantly through activation of ERK1/2.22 Similar findings by Guzeloglu-Kayisli et al53 explained the repression of progesterone receptor mRNA and protein by IL-1β in human decidual cells. By contrast, in the endometriosis-derived EESCs, BDNF precursors, dimers, and mature proteins all are up-regulated by IL-1β, acting through a combination of JNK, NF-κB, and mTOR signaling pathways. Like BDNF, the chemokine RANTES, which also is downstream of IL-1β action in EESCs, appears to be primarily responsive to its JNK and NF-κB signaling cascades. These same pathways were recently highlighted in the unsupervised multivariate analysis of cytokine profiles by Beste et al.37

The role of NF-κB in the regulation of RANTES in ectopic lesions and eutopic endometrium has been well established in cases of endometriosis.54, 55, 56 The 34% inhibition of IL-1β–induced RANTES by SN50 noted in Figure 7B is consistent with previous findings that sulindac suppressed IL-1β–induced RANTES by 61%.57 The latter inhibitor may be more potent than SN50 because it targets prostaglandin synthesis and β-catenin in addition to its ability to interfere with NF-κB signaling.58, 59 Because it suppressed BDNF, the JNK inhibitor SP600125 also strongly inhibits IL-1β–induced RANTES secretion, supporting the concept that genes corresponding to these NT and chemokine proteins are coordinately regulated as a network of inflammatory responses, including macrophage recruitment and NT production, which lead to local implant innervation. In keeping with this finding, a prior study reported that 60-day treatment with the JNK inhibitor bentamapimod significantly reduced lesion surface area and volume relative to placebo controls in a surgically induced baboon model of endometriosis. The investigators noted that animals treated with JNK inhibitor showed more remodeling of red lesions to typical or fibrotic implants.60 The latter observation is consistent with a therapeutic suppression of neuroangiogenesis, providing in vivo support of our in vitro findings.

An important clinical implication of the present observations is that interference with BDNF production represents a tractable therapeutic strategy, but one that might necessitate selective blockade of signaling pathways. Our findings on the role of IL-1β might lead to the conclusion that direct targeting of the IL-1 receptor may prove efficacious to mitigate pain and inflammation associated with endometriosis. However, IL-1β critically facilitates the physiological combat of infectious organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus,61 and injudicious suppression of IL-1 receptor signaling could risk susceptibility to overwhelming infection. Thus, the targeting of specific signaling pathways is an attractive therapeutic goal, but its practical implementation may be challenging. In normal endometrial stromal cells five distinct IL-1β signal transduction cascades were identified,22 and others likely exist. These preclinical studies suggest that selective antagonism of NF-κB and JNK pathways, acting downstream of IL-1β, might be beneficial. Development of such inhibitors should be a committed focus of the pharmaceutical industry, with a goal to provide nonhormonal medication options that effectively interrupt endometriosis-associated pain.

Some strengths and limitations of the present investigation are worth noting. The focus on IL-1β is consistent with an extensive body of literature confirming this cytokine to be a critical pathophysiological mediator in endometriosis.62 An advantage of our approach is that it uses a validated, dynamic human EESC model that recapitulates neuroangiogenic responses to proinflammatory cytokines observed in eutopic and ectopic endometrial tissues in vivo. However, limitations of this model include i) these EESC are maintained on polystyrene as opposed to being organized in three-dimensions within an extracellular matrix as they exist in vivo; ii) specific contributions of epithelial and vascular cells that also are components of the lesions in vivo have not been modeled; and iii) the effects of ovarian steroid hormones or retinoids, which are known to influence endometriosis implant growth and clinical symptoms,63 have not been addressed. It also should be noted that analyses of the IL-1β–NF-κB/JNK-BDNF pathways are amenable to adaptation in murine models of endometriosis, and the latter should be developed for functional proof-of-concept experiments to move hypotheses closer to potential pharmacologic interventions for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

Acknowledgments

We thank the operating room and nursing staffs of Wake Forest Baptist Hospital (Winston-Salem, NC) and the Samuel Libanio Hospital (Pouso Alegre, Brazil) who contributed to the protocol and the generous participation of the study subjects. We thank the late Hermina Borgerink for expert assistance with immunohistochemistry in these studies.

J.Y., A.M.C.F., and R.N.T. conceived the study; J.Y., A.M.C.F., J.M.C., and E.Z. acquired data; J.Y., A.M.C.F., J.M.C., S.L.B., and R.N.T. analyzed the data; A.M.C.F., B.G.P., S.L.B., and R.N.T. provided clinical samples; J.Y., A.M.C.F., B.G.P., J.M.C., S.L.B., and R.N.T. wrote the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript; R.N.T. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, has full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and accuracy.

Footnotes

Supported by the NIH Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R21 HD78818 (R.N.T.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Current address of R.N.T., University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.06.011.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Buck Louis G.M., Hediger M.L., Peterson C.M., Croughan M., Sundaram R., Stanford J., Chen Z., Fujimoto V.Y., Varner M.W., Trumble A., Giudice L.C., ENDO Study Working Group Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson G.D., Kennedy S.H., Hummelshoj L. Creating solutions in endometriosis: global collaboration through the World Endometriosis Research Foundation. J Endometriosis. 2010;2:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simoens S., Dunselman G., Dirksen C., Hummelshoj L., Bokor A., Brandes I., Brodszky V., Canis M., Colombo G.L., DeLeire T., Falcone T., Graham B., Halis G., Horne A., Kanj O., Kjer J.J., Kristensen J., Lebovic D., Mueller M., Vigano P., Wullschleger M., D'Hooghe T. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1292–1299. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koninckx P.R., Ussia A., Adamyan L., Wattiez A., Donnez J. Deep endometriosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morotti M., Vincent K., Becker C.M. Mechanisms of pain in endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;209:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.07.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker C.M., Gattrell W.T., Gude K., Singh S.S. Reevaluating response and failure of medical treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor R.N., Hummelshoj L., Stratton P., Vercellini P. Pain and endometriosis: etiology, impact, and therapeutics. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2012;17:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor R.N., Lebovic D.I. Endometriosis. In: Strauss J.F., Barbieri R.L., editors. Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology. ed 7. Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2014. pp. 565–585. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J., Xie H., Yao S., Liang Y. Macrophage and nerve interaction in endometriosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:53. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0828-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asante A., Taylor R.N. Endometriosis: the role of neuroangiogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:163–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tokushige N., Markham R., Russell P., Fraser I.S. Nerve fibres in peritoneal endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3001–3007. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bokor A., Kyama C.M., Vercruysse L., Fassbender A., Gevaert O., Vodolazkaia A., De Moor B., Fulop V., D'Hooghe T. Density of small diameter sensory nerve fibres in endometrium: a semi-invasive diagnostic test for minimal to mild endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:3025–3032. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browne A.S., Yu J., Huang R.P., Francisco A.M., Sidell N., Taylor R.N. Proteomic identification of neurotrophins in the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wessels J.M., Kay V.R., Leyland N.A., Agarwal S.K., Foster W.G. Assessing brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a novel clinical marker of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichardt L.F. Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:1545–1564. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuda S., Fujita T., Kajiya M., Takeda K., Shiba H., Kawaguchi H., Kurihara H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces migration of endothelial cells through a TrkB-ERK-integrin alphaVbeta3-FAK cascade. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2123–2129. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817–821. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood C.E., Borgerink H., Register T.C., Scott L., Cline J.M. Cervical and vaginal epithelial neoplasms in cynomolgus monkeys. Vet Pathol. 2004;41:108–115. doi: 10.1354/vp.41-2-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J., Berga S.L., Johnston-MacAnanny E.B., Sidell N., Bagchi I.C., Bagchi M.K., Taylor R.N. Endometrial stromal decidualization responds reversibly to hormone stimulation and withdrawal. Endocrinology. 2016;157:2432–2446. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan I.P., Schriock E.D., Taylor R.N. Isolation, characterization, and comparison of human endometrial and endometriosis cells in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:642–649. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.3.8126136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J., Boicea A., Barrett K.L., James C.O., Bagchi I.C., Bagchi M.K., Nezhat C., Sidell N., Taylor R.N. Reduced connexin 43 in eutopic endometrium and cultured endometrial stromal cells from subjects with endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:260–270. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J., Berga S.L., Zou W., Yook D.G., Pan J.C., Andrade A.A., Zhao L., Sidell N., Bagchi I.C., Bagchi M.K., Taylor R.N. IL-1beta inhibits connexin 43 and disrupts decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells through ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinase. Endocrinology. 2017;158:4270–4285. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malek A.M., Izumo S. Mechanism of endothelial cell shape change and cytoskeletal remodeling in response to fluid shear stress. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:713–726. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mowla S.J., Farhadi H.F., Pareek S., Atwal J.K., Morris S.J., Seidah N.G., Murphy R.A. Biosynthesis and post-translational processing of the precursor to brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12660–12666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arend W.P. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:167–227. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reis F.M., Petraglia F., Taylor R.N. Endometriosis: hormone regulation and clinical consequences of chemotaxis and apoptosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:406–418. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hornung D., Ryan I.P., Chao V.A., Vigne J.L., Schriock E.D., Taylor R.N. Immunolocalization and regulation of the chemokine RANTES in human endometrial and endometriosis tissues and cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1621–1628. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.5.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J., Wu J., Bagchi I.C., Bagchi M.K., Sidell N., Taylor R.N. Disruption of gap junctions reduces biomarkers of decidualization and angiogenesis and increases inflammatory mediators in human endometrial stromal cell cultures. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;344:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akoum A., Lawson C., Herrmann-Lavoie C., Maheux R. Imbalance in the expression of the activating type I and the inhibitory type II interleukin 1 receptors in endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1464–1473. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lebovic D.I., Bentzien F., Chao V.A., Garrett E.N., Meng Y.G., Taylor R.N. Induction of an angiogenic phenotype in endometriotic stromal cell cultures by interleukin-1beta. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:269–275. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebovic D.I., Chao V.A., Taylor R.N. Peritoneal macrophages induce RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) chemokine gene transcription in endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1397–1401. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng J.F., Ryan I.P., Milam T.D., Murai J.T., Schriock E.D., Landers D.V., Taylor R.N. Interleukin-6 secretion in vitro is up-regulated in ectopic and eutopic endometrial stromal cells from women with endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1118–1122. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber A., Wasiliew P., Kracht M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci Signal. 2010;3:cm1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3105cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokoo T., Kitamura M. Antioxidant PDTC induces stromelysin expression in mesangial cells via a tyrosine kinase-AP-1 pathway. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:F806–F811. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.5.F806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hornung D., Klingel K., Dohrn K., Kandolf R., Wallwiener D., Taylor R.N. Regulated on activation, normal T-cell-expressed and -secreted mRNA expression in normal endometrium and endometriotic implants: assessment of autocrine/paracrine regulation by in situ hybridization. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1949–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64664-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lebovic D.I., Chao V.A., Martini J.F., Taylor R.N. IL-1beta induction of RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) chemokine gene expression in endometriotic stromal cells depends on a nuclear factor-kappaB site in the proximal promoter. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4759–4764. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beste M.T., Pfaffle-Doyle N., Prentice E.A., Morris S.N., Lauffenburger D.A., Isaacson K.B., Griffith L.G. Molecular network analysis of endometriosis reveals a role for c-Jun-regulated macrophage activation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:222ra16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampson J.A. Perforating hemorrhagic (chocolate) cysts of the ovary: their importance and especially their relation to pelvic adenomyomas of endometrial type. Arch Surg. 1921;3:245–323. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meigs J.V. Endometrial hematomas of the ovary. Boston Med Surg J. 1922;187:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haney A.F., Muscato J.J., Weinberg J.B. Peritoneal fluid cell populations in infertility patients. Fertil Steril. 1981;35:696–698. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)45567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berkley K.J., Rapkin A.J., Papka R.E. The pains of endometriosis. Science. 2005;308:1587–1589. doi: 10.1126/science.1111445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.As-Sanie S., Kim J., Schmidt-Wilcke T., Sundgren P.C., Clauw D.J., Napadow V., Harris R.E. Functional connectivity is associated with altered brain chemistry in women with endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain. J Pain. 2016;17:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anaf V., El Nakadi I., De Moor V., Chapron C., Pistofidis G., Noel J.C. Increased nerve density in deep infiltrating endometriotic nodules. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71:112–117. doi: 10.1159/000320750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang G., Tokushige N., Markham R., Fraser I.S. Rich innervation of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:827–834. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medina M.G., Lebovic D.I. Endometriosis-associated nerve fibers and pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:968–975. doi: 10.1080/00016340903176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levi-Montalcini R., Dal Toso R., della Valle F., Skaper S.D., Leon A. Update of the NGF saga. J Neurol Sci. 1995;130:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00007-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borghese B., Vaiman D., Mondon F., Mbaye M., Anaf V., Noel J.C., de Ziegler D., Chapron C. Neurotrophins and pain in endometriosisFrench Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2010;38:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anger D.L., Zhang B., Boutross-Tadross O., Foster W.G. Tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB) protein expression in the human endometrium. Endocrine. 2007;31:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s12020-007-0025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rocha A.L., Vieira E.L., Ferreira M.C., Maia L.M., Teixeira A.L., Reis F.M. Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor in women with pelvic pain: a potential biomarker for endometriosis? Biomark Med. 2017;11:313–317. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2016-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bondza P.K., Maheux R., Akoum A. Insights into endometriosis-associated endometrial dysfunctions: a review. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2009;1:415–428. doi: 10.2741/E38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu J., Berga S.L., Zou W., Sun H.Y., Johnston-MacAnanny E., Yalcinkaya T., Sidell N., Bagchi I.C., Bagchi M.K., Taylor R.N. Gap junction blockade induces apoptosis in human endometrial stromal cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81:666–675. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ross J.L., Queme L.F., Lamb J.E., Green K.J., Ford Z.K., Jankowski M.P. Interleukin 1beta inhibition contributes to the antinociceptive effects of voluntary exercise on ischemia/reperfusion-induced hypersensitivity. Pain. 2018;159:380–392. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guzeloglu-Kayisli O., Kayisli U.A., Semerci N., Basar M., Buchwalder L.F., Buhimschi C.S., Buhimschi I.A., Arcuri F., Larsen K., Huang J.S., Schatz F., Lockwood C.J. Mechanisms of chorioamnionitis-associated preterm birth: interleukin-1beta inhibits progesterone receptor expression in decidual cells. J Pathol. 2015;237:423–434. doi: 10.1002/path.4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kishimoto T., Akira S., Taga T. Interleukin-6 and its receptor: a paradigm for cytokines. Science. 1992;258:593–597. doi: 10.1126/science.1411569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao D., Lebovic D.I., Taylor R.N. Long-term progestin treatment inhibits RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted) gene expression in human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2514–2519. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ponce C., Torres M., Galleguillos C., Sovino H., Boric M.A., Fuentes A., Johnson M.C. Nuclear factor kappaB pathway and interleukin-6 are affected in eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. Reproduction. 2009;137:727–737. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wieser F., Vigne J.L., Ryan I., Hornung D., Djalali S., Taylor R.N. Sulindac suppresses nuclear factor-kappaB activation and RANTES gene and protein expression in endometrial stromal cells from women with endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6441–6447. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boon E.M., Keller J.J., Wormhoudt T.A., Giardiello F.M., Offerhaus G.J., van der Neut R., Pals S.T. Sulindac targets nuclear beta-catenin accumulation and Wnt signalling in adenomas of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:224–229. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamamoto Y., Yin M.J., Lin K.M., Gaynor R.B. Sulindac inhibits activation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27307–27314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hussein M., Chai D.C., Kyama C.M., Mwenda J.M., Palmer S.S., Gotteland J.P., D'Hooghe T.M. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase inhibitor bentamapimod reduces induced endometriosis in baboons: an assessor-blind placebo-controlled randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:815–824. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller L.S., Cho J.S. Immunity against Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kyama C.M., Mihalyi A., Simsa P., Falconer H., Fulop V., Mwenda J.M., Peeraer K., Tomassetti C., Meuleman C., D'Hooghe T.M. Role of cytokines in the endometrial-peritoneal cross-talk and development of endometriosis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2009;1:444–454. doi: 10.2741/e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor R.N., Kane M.A., Sidell N. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: roles of retinoids and inflammatory pathways. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33:246–256. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1554920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.