Abstract

Bee sting has been identified as among causative agents of nephrotoxic acute tubular necrosis which may lead to acute kidney injury. Bee envenomation has medicinal properties but when a higher dose is inoculated may cause severe anaphylaxis with very poor prognosis. We report a 12-year-old boy with acute kidney injury following multiple bee stings who recovered well after hemodialysis.

INTRODUCTION

In the world we live in, insect stings by Hymenoptera are common, data indicates that, 56.6–94.5% of the general population has been stung at least once in their life time [1]. The stinging insects of order hymenoptera, of medical importance are bees, wasps, hornets, yellow jackets and ants [2, 3]. African bees (Alpis mellifera scutella, Alpis mellifera monticola) are extremely aggressive and attack victim in swarm [4]. The complication of the stings ranges from local reaction (skin reaction) to anaphylaxis and multiple organ failure(systemic sting reaction). Evenomation by bee sting of >500 are sufficient to cause significant damage and even death [2, 4, 5]. Bee sting triggers immediate allergic reaction mediated by Immunoglobin E with large local reaction such as urticaria, flushing and angioedema while hypotension, dyspnea and dizziness can progress to loss of consciousness, shock and even cardiopulmonary arrest. These manifestations are moderate to severe reactions [1]. Severe reaction cause multiorgan damage like acute kidney injury (AKI) and myocardial infarction [2–4, 6, 7]. AKI in children following multiple bee stings is uncommon complication in Africa and there is limited literature, especially in children. Also there is no treatment protocol that can be initiated promptly at all levels of health care services [8, 9]. In this case report, we will describe a case of AKI following multiple bee stings in peadiatric and resource-limited setting.

CASE REPORT

We present a 12-year-old Tanzanian male who was stung by numerous (around 500 stings) African bee while he was walking back home from school in Kilimanjaro region, Northern Tanzania. He was stung mainly on the face, upper limbs and trunk (Fig. 1). He was admitted to a local hospital within an hour of bee stings, where he was given IV fluids, hydrocortisone and diclofenac IM for pain, respectively.

Figure1:

Facial and trunk location of bee stings.

After 28 h of hospital stay, his condition was deteriorating; facial edema was progressive and developed decrease in urine output, therefore, he was given furosemide (2 mg/kg) a stat dose. His vitals were BP 100/70 mmHg, HR 68 beat/min, RR 35 breath/min. He was then referred to our tertiary hospital due to suspicion of kidney injury.

On arrival at the center, he was conscious, could not see well although his voice and tongue were unaltered. He had facial swelling and peri-orbital edema. He had erythema stings marks on his face, trunk and upper limbs. His vitals were normal, saturating in room air at 97%, RR 28 breath/min, HR 94 beat/min strong and regular and BP 118/70 mmHg (90th percentile). He was treated with broad spectrum antibiotic (ceftriaxone) and fluid restriction.

The initial laboratory investigations included creatinine and urea which were 116 and 15.4 mmol/l, respectively. Serum electrolytes revealed hyperkalemia of 6.9 mmol/l which was managed by administration of D10% plus Insulin and calcium gluconate. had hyponatremia 128mmo/l. A catheter was inserted, urine for dipstick showed RBC+++ and microscopy examination revealed muddy brown cast. CBC had leucocytosis of 25 predominant of neutrophils 89.7%, hemoglobin of 13.8 g/dl, normocytic normochromic, platelet count of 269. After correction control electrolytes were K 5.15 mmol/l and Na 128 mmol/l.

Within 24 h of arrival, his urine output was 200 ml of amber colored urine for 18 h (0.35 ml/kg/h). His creatinine and urea had risen to 248 and 22.52mmo/l. The next 12 h of restricting fluid input to 700 ml (a third of maintenance), close monitoring of the input and output, he produced only 100 ml of urine (0.26 ml/kg/h), the creatinine and urea were 402 and 29.83 mmol/l, respectively, while his potassium was 5.4 mmol/l and sodium of 127 mmol/l. He was transferred to pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), hemodialysis was considered inevitable due to worsening metabolic and fluid retention. At initiationm potassium was 5.99 mmol/l, creatinine of 462 mmol/l and urea of 34.65 mmol/l (24 h after admission in PICU) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Main clinical parameters and laboratory investigations during admission

| Hours from admission | 0 | 18 h | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Day 8 | Day 9 | Day 11 | Day 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before dialysis | During dialysis | After dialysis | ||||||||||

| Fluid input 24 h (ml) | 1500 | 700 | 700 | 750 | 800 | 700 | 700 | 700 | ||||

| Urine output (ml) | 200 | 100 | 100 | 300 | 410 | 1150 | 1950 | 1150 | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.8 | |||||||||||

| Hematocrit % | 43.7 | |||||||||||

| MCV (fl) | 85.8 | |||||||||||

| MCH (pg) | 27.1 | |||||||||||

| MCHC (g/dl) | 31.6 | |||||||||||

| Leukocyte (×109 cells/ml) | 25 | |||||||||||

| Neutrophils (%) | 89.7 | |||||||||||

| Lymphocytes (%) | 5.3 | |||||||||||

| Monocytes (%) | 2.7 | |||||||||||

| Eosinophils (%) | 2.1 | |||||||||||

| Basophils (%) | 0.2 | |||||||||||

| Platelet (×109/ml) | 550 | |||||||||||

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | 116 | 248 | 402 | 462 | 606 | 669 | 569 | 631 | 781 | 759 | 375 | 172 |

| BUN (mmol/l) | 15.4 | 22.52 | 29.83 | 34.65 | 44.13 | 36.11 | 29.23 | 31 | 33 | 25 | 14 | 11 |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 128.45 | 125.9 | 127.02 | 125.58 | 128 | 126.18 | 128.03 | 124 | 124 | 131 | 137 | 138 |

| Potassium (mmol/l) | 6.9 | 5.15 | 5.46 | 5.99 | 4.65 | 6.08 | 5.05 | 4.95 | 5.99 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Calcium (mmol/l) | 1.99 | 2.14 | ||||||||||

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Negative | |||||||||||

| Hepatitis C antigen | Negative | |||||||||||

| Blood cultures (central and peripheral) | No bacterial growth | |||||||||||

Reference ranges: serum creatinine (60–120 μmol/l), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (2.1–7.1 mmol/l), sodium (136–148 mmol/l), potassium (3.8–5 mmol/l), calcium (2.15–2.65 mmol/l), leukocyte count (3.5–9.0 × 109/l).

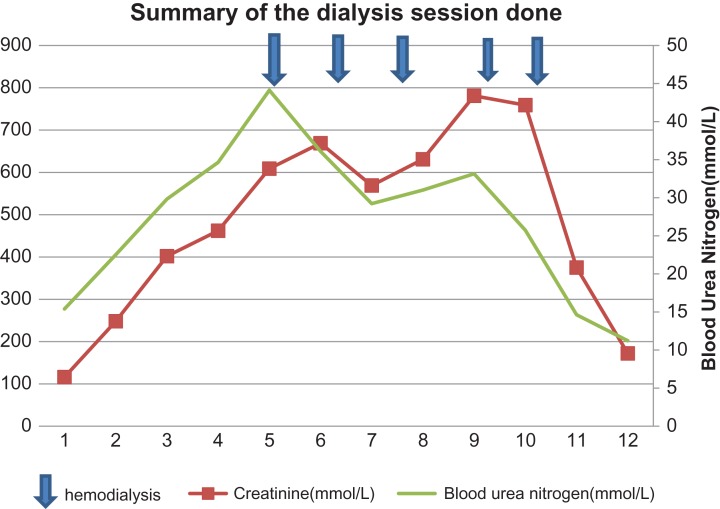

He had five sessions as shown in Chart 1. During the fifth session he developed a high grade fever 38.6°C. Blood cultures from the central line and peripheral were collected. He was kept on vancomycin every third day for 1 month. The cultures were all negative on Day 7.

Chart. 1:

Summary of the dialysis session and trends of serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen.

After the sessions, urine output raised to 1.8 ml/kg/h, before discharge his creatinine was 172 mmol/l and urea of 11 mmol/l. The electrolytes were normal, K+ 4.6 mmol/l, Na+ 138mmo/l. He had a 2-week hospital stay.

One week follow-up after discharge; his biochemistry was back to normal, creatinine of 52 mmol/l, urea 2.96 mmol/l. Electrolytes were normal.

DISCUSSION

Bee sting is a common encounter in our region, although there are limited medical reports on bee sting and AKI.

It has been reported that up to 30 bee stings in children is enough to cause significant multiorgan damage. AKI in children after bee sting has been reported elsewhere [8]. Bee sting leaves stings behind which release venom amounting to 50–140 µg/sting which is a large dose enough to cause systemic damage [2, 9].

AKI is a result of multiple factors like hypotension, direct toxicity of the venom components to the renal tubules, intravascular hemolysis and rhabdomyolysis. Bee sting can cause severe anaphylaxis reaction and arterial hypotension which might lead to significant damage and even death. This is a major component that cause AKI due to ischemia of the renal tubules [5]. The protein components in bee venom, phospholipase A2, hyaluronic acid, melittin and apamin are culprits. A neurotoxin with motor action, apamin, specifically causes profound vasodilatation which lead to decrease in blood pressure and increase of heart rate. This consequently leads to hypoperfusion.

The other mechanism is when there is rhabdomyolysis, the myoglobin are toxic to the renal tubule [5, 6, 10, 11]. Bee sting venom is thought to cause non traumatic rhabdomyolysis. Acute cellular injury is caused by tubular myoglobin accumulation, lipid peroxidation within the tubular cells and vasoconstriction [6, 10]. It is possible that the cause of AKI was related to acute tubular necrosis (ATN), and there was no indication for percutaneous renal biopsy in this patient. His urine analysis revealed microscopic hematuria and muddy brown casts which does not favors the presence of ATN more than pre-renal causes of increased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Rhabdomyolysis and pigment tubulopathy could not be ruled out, the muscular enzymes were not determined, and the patient had no spleenomegaly. ATN is a histological end result of these pathogenesis and acute tubular interstitial nephritis could have occurred in combination.

The stings in the skin cause inflammation and can end up with skin and soft tissue necrosis due to allergic vasculitis. Our patient on arrival had erythema on the skin and some stings, which were removed. He did not require analgesics or topical antiseptic/antibiotics. Skin healed leaving behind black spots (Fig. 1).

Facial edema was progressive increasing due to worsening of the renal function in our patient. He had blood in urine and his creatinine was increasing with decreased urine out. This is due to acute insult to the kidney. After dialysis, the facial swelling disappeared, his creatinine and urine output recovered to normal.

Early management of anaphylaxis with IM epinephrine (adrenaline), significantly reduces the complications, as they appear 48–72 h after the attack [2–4,6, 7, 12].

Both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis have been used to treat AKI following multiple bee sting effectively with good outcomes [2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11]. Although dialysis does not clear the bee venom, maintenance of good hydration and urine output are necessary in management of bee sting venom.

Our medical communities need to be alert on the prompt identification of anaphylaxis in children and administration of IM epinephrine. In this case we have described epinephrine was not given at any point, he was given hydrocortisone instead. The hydrocortisone is only useful in reduction or prevention of biphasic or late phase reaction [2]. Guideline on venom immunotherapy is available. The recommendation is that, children with local large reaction can receive venom immunotherapy to reduce subsequent severe systemic reaction [1]. This service in our region is almost inexistence despite having abundancy of the most aggressive bees. We encourage rapid transfer of patients with multiple bee stings to tertiary hospitals as renal lesions might occur. Dialysis should be initiated as needed to achieve better outcomes in patients with AKI following bee sting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors express their gratitude to all the members of the Pediatric Intensive care unit and Dialysis unit of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center who were involved in care of the patient though out his treatment. Also we appreciate the readiness of the patient and his parents who provided consent.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

This work was not financially supported.

CONSENT

The patient provided ascent and parents provided informed consent to publish this case report.

GUARANTOR

All authors stated in the article accept full responsibility for the work, had access to the patient’s information, and controlled the decision to publish.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sturm GJ, Varga EM, Roberts G, Mosbech H, Bilò MB, Akdis CA, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy 2018;73:744–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dongol Y, Shrestha RK, Aryal G, Lakkappa B. Hymenoptera stings and the acute kidney injury. Eur Med J Nephrol 2013;1:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumar V, Nada R, Kumar S, Ramachandran R, Rathi M, Kohli HS, et al. Acute kidney injury due to acute cortical necrosis following a single wasp sting. Ren Fail 2013;35:170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bridi RA, Balbi AL, Neves PM, Ponce D. Acute kidney injury after massive attack of Africanised bees. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silva GBD Jr, Vasconcelos AG Jr, Rocha AMT, Vasconcelos VR, Neto BJ, Fujishima JS, et al. Acute kidney injury complicating bee stings—a review. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2017;59:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mingomataj EÇ, Bakiri AH, Ibranji A, Sturm GJ. Unusual reactions to hymenoptera stings: what should we keep in mind? Clin Rev Immunol 2014;47:91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nisahan B, Selvaratnam G, Kumanan T. Myocardial injury following multiple bee stings. Trop Doct 2015;44:233–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ayaovi D, Akolly E, Guedenon KM, Tsolenyanu E, Bessi LK. Massive envenomation by bees sting in a child in Togo. Open J Pediatr 2016;6:232–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jimoh AO, Akuse RM, Bugaje MA, Mayaki S. A call for sting treatment protocol: case report of a 3 year old with massive bee sting resulting in acute kidney injury. Niger J Paediatr 2016;43:231–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ling Z, Yan K, Ping F, Yu C, Yunying S, Fang L, et al. Myoglobin clearance by continuous venous-venous haemofiltration in rhabdomyolysis with acute kidney injury: a case series. Inj Int J Care Inj 2012;43:619–23. 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nair BT, Sanjeev RK, Saurabh K. Acute kidney injury following multiple bee stings. Ann Afr Med 2016;15:41–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gabriel DP, Rodriques AGJ, Barsante RC, Silva V, dos S, Caramori JT, et al. Severe acute renal failure after massive attack of Africanized bees. Nephrol Dial Transpl 2004;19:2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]