Abstract

The current treatment strategies for osteoporosis (OP) involve promoting osteogenic differentiation and inhibiting adipogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). According to a theory of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the kidneys contain an “essence” that regulate bone metabolism and generate marrow. Kidney disorders are therefore considered to be a major cause of OP as per the principles of TCM, which recommends kidney-tonifying treatments for OP. The Zuogui pill (ZGP) is a classic kidney-tonifying medication that effectively improves OP symptoms. Studies have shown that ZGP can promote the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, providing scientific evidence for the TCM theory linking kidneys with bone metabolism. In this review, we have provided an overview of recent studies that examined the underlying mechanisms of ZGP mediated regulation of BMSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation.

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a common metabolic bone disease characterized by decreased bone mass and density and abnormal microstructure, all of which result in increased bone fragility. OP is broadly divided into primary and secondary OP, and the former is further classified into postmenopausal, senile, and idiopathic forms [1, 2]. The incidence of OP is increasing annually with the aging of the global population [2]. A steady-state imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation is the pathological basis of OP [1]. As the mechanism of osteoclast differentiation became clearer, several anti-bone resorption medications such as bisphosphonates began to emerge as promising therapies for OP. However, long-term use of osteoclast inhibitors can inhibit bone remodeling and result in various side-effects [3], including mandibular necrosis [4]. Therefore, greater attention has now been directed towards understanding the mechanisms involved in promoting bone formation.

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were identified nearly half a century ago and have since been extensively studied. BMSCs can differentiate under specific conditions into multiple cells, including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, cardiomyocyte-like cells, vascular endothelial cells, neurons, hepatocytes, and adipocytes [5]. As a result of their multipotent differentiation and self-renewal capabilities, the ease of their isolation and in vitro expansion, and low risk of immune rejection, BMSCs are highly promising in stem cell based therapies [6]. Several studies have found that reduced osteogenic differentiation and increased adipogenic differentiation of BMSCs are the key pathogenic drivers of OP [7–9]. Therefore, blocking the adipogenic differentiation and promoting osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs is a potential strategy to restore the imbalanced bone metabolism in OP [9–11].

According to TCM theories, a kidney “essence” controls bone metabolism and generates marrow; if this essence is sufficient, bone marrow will be engorged, and the bone will be healthy and strong. The deficiency of this essence is the major pathological cause of OP as per TCM principles. Previous studies have demonstrated that kidney essence deficiency is closely associated with OP [12], whose onset is most pronounced in patients with kidney disorders [13]. In addition, studies on the quality of life and TCM syndrome of postmenopausal OP patients showed that kidney deficiency occurred in up to 84.7% of the patients [14]. Kidney-tonifying herbal medicines improved bone structure in OP rats by increasing serum estradiol level and bone density [15]. A clinical study by Liu et al. also showed that a kidney-tonifying herbal medicine can increase bone density, lower bone turnover rate, alleviate OP-induced osteopathic pain, and improve the quality of life of patients [16]. These findings all demonstrate that kidney deficiency is closely associated with OP and that kidney-tonifying therapy can alleviate OP [17].

BMSCs are pluripotent adult stem cells that are mainly found in the human bone marrow. They can undergo osteogenesis under certain conditions and are part of the essence and marrow described in TCM. Studies have found that the mechanisms of BMSC proliferation, differentiation, and development are very similar to the role that the kidney essence plays in the growth, development, and aging of an individual [18]. In fact, the primary functions of kidney essence are reflected in the proliferation and differentiation of BMSCs [19]. Recent studies have shown that BMSCs differentiation is a complex process that can be influenced by the synergistic action of multiple factors, including intracellular and extracellular signal transduction, physical and chemical factors, epigenetic modification, transcriptional regulation, and posttranscriptional regulation. However, whether BMSCs differentiation is determined by specific molecules or pathways is currently unclear. On the other hand, kidney-tonifying Chinese herbal medicines have demonstrated multipathway, multifunctional, and multitarget modulatory effects in the prevention and treatment of OP. Therefore, understanding the effect of these medicines on the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs will provide new insights into the scientific basis of the TCM theory of kidney essence in bone metabolism and OP. The overall effects of classic Chinese kidney-tonifying recipes on BMSC differentiation are currently ill-defined as the previous studies were largely focused on the effect of a single herbal medicine or monomer, which can neither fully reflect the “kidney-tonifying, essence-generating, and marrow-benefiting” properties of these TCM recipes nor the compatibility of these formulations. Although a single herbal medicine is composed of only its chemical constituents or active ingredients, the same medicine will have different pharmacodynamics in different recipes and, under different pathological states, and the resulting effective substance it releases will also be different [20]. At present, Zuogui pill (ZGP) is the best known kidney-tonifying recipe that has been shown to regulate BMSC osteogenic differentiation. In this review, we have provided an overview of current findings on ZGP-induced BMSC osteogenic differentiation and its application in the treatment of OP.

2. Signal Transduction Pathways That Regulate BMSCs Differentiation

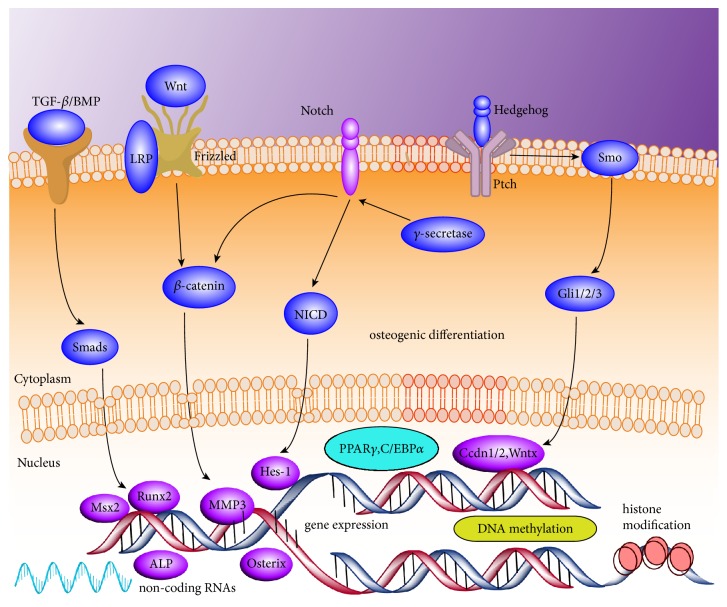

Several signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of BMSC mediated osteogenesis and adipogenesis, and their mechanisms have been previously reported in numerous reviews [21–24]. These pathways include those of bone morphogenic protein (BMP)/Smad, Wnt, Hedgehog, Notch and fibroblast growth factor signaling, in addition to epigenetic regulation (Figure 1). It is apparent that BMSC differentiation is a multistep, multitarget, and multifactorial process, but whether this process is regulated by specific key molecules or pathways is currently unclear. Therefore, finding specific targets is the top concern for the treatment of OP.

Figure 1.

Signal transduction pathways that regulate BMSCs differentiation. TGF-β/BMP, Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of BMSC mediated osteogenesis. DNA methylation, histone modification, and noncoding RNAs regulation play a significant role in gene expression associated with osteogenic differentiation of BMSC.

3. Role of ZGP in the Regulation of BMSCs Osteogenic Differentiation

ZGP is a well-known classic kidney-tonifying recipe that originated from “The Complete Works of Jing-yue” by Zhang Jingyue in Ming dynasty. This formulation consists of processed rehmannia root, Rhizome dioscoreae, goji, Cyathula officinalis, Cornus officinalis, Cuscuta chinensis, deer horn gelatin, and tortoise plastron gelatin and generates the kidney essence which benefits marrow and strengthens the muscles and bones. ZGP has been clinically proven to significantly increase the bone density of primary OP patients [25]. Animal studies have also demonstrated that ZGP and Yougui pill (YGP) can prevent and treat bone loss in the ovariectomized rat model of OP by increasing bone density and trabecular bone surface area, restoring serum levels of bone metabolism markers, and improving bone metabolism [26–28]. Analysis of ZGP constituents by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS) revealed indole acetaldehyde, retinylester, and alpha-CEHE as the potential active ingredients, strongly suggesting that the anti-OP mechanisms of ZGP may be associated with the tryptophan and retinol metabolism pathways [29]. Indole acetaldehyde can reversibly convert to tryptophan, and the latter is a precursor of 5-hydroxytrptamine which is closely associated with bone formation and resorption [30]. Similarly, retinyl ester can reversibly convert to vitamin A [31], and the latter is present in osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Excessive levels of vitamin A can inhibit osteoblast activity and enhance osteoclast activity [32]. Alpha-CEHE is a metabolite of vitamin E [33], and vitamin E level is closely associated with osteoclast activity [34] and pathogenesis of OP [35].

The morphology and the proliferative and differentiation capabilities of BMSCs decline with age [36]. Senile BMSCs are larger and more flattened and have enlarged nuclei and fewer mitochondria that often appear swollen, expanded endoplasmic reticulum and lipofuscin deposition. Furthermore, the proportion of polygonal and star-shaped BMSCs increases with age while that of fibrous spindle-like BMSCs decreases [37]. Therefore, enhancing the proliferative capability and improving the senile morphology of BMSCs can induce their osteogenic differentiation [38]. Studies have shown that ZGP can reduce ultrastructural damage and maintain the normal spindle-like morphology of BMSCs in aged rats [39, 40], promote proliferation [41], and inhibit apoptosis as indicated by elevated caspase-3 and decreased Bcl-2 levels [42, 43].

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is an early marker of osteoblast differentiation. ALP levels begin to increase during matrix synthesis and peak at the calcification phase [44]. It is also a marker for osteoblast maturation and can reflect the ability of osteoblast to synthesize type I collagen and form the bone matrix [45]. Therefore, ALP can be used as a key indicator of the functional status of osteoblasts to assess the degree of osteogenic differentiation [46]. OP patients not only have decreased BMSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation capability, but also increased adipogenesis, reduced levels of type I collagen, and reduced calcified nodule formation, all of which culminate in decreased number of osteoblasts and increased number of osteoclasts [36]. Calcified nodules are the products of the calcium salts secreted by osteoblasts and are one of the key markers of osteoblast differentiation and maturation [47]. One study reported that ZGP-containing serum (ZGP serum) could significantly promote the formation of mineralized nodules [48] and increase the expression of ALP and type I collagen [49, 50], thereby inducing the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs [51, 52]. In addition, ZGP serum can inhibit BMSC adipogenic differentiation in ovariectomized rats by inhibiting the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), lipoprotein lipase (LPL), and fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) [53], which are key regulators of adipogenesis [54].

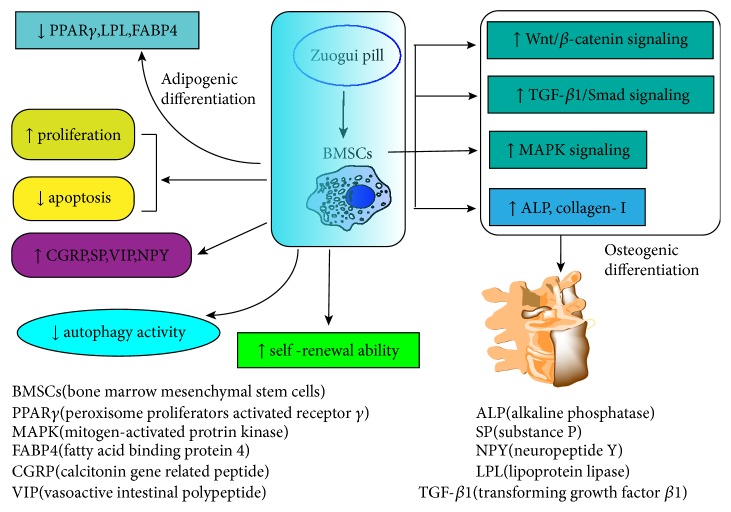

Further studies have shown that the osteogenic differentiation-promoting effect of ZGP serum on BMSCs is associated with the upregulation of β-catenin and LRP-5 protein levels [55]. In the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, binding of Wnt to its receptor Frizzled and related receptor LRP5/6 leads to cytosolic accumulation of β-catenin. Upon nuclear translocation, β-catenin acts on the transcription factors Tcf/Lef to activate several downstream genes including matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3), which subsequently promote BMSC osteogenic differentiation and inhibit their adipogenic differentiation [56]. A reduction in LRP-5 activity results in OP [57]. On the other hand, the p38 MAPK signaling [58] and TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathways [29, 59, 60] are also involved in ZGP serum-induced BMSC osteogenic differentiation. In addition, ZGP serum can also upregulate the levels of neuropeptides and neurotrophic factors, such as CGRP, SP, VIP, and NPY in BMSCs and bone tissues of ovariectomized OP rats, demonstrating that ZGP serum regulates bone metabolism via the neuroendocrine axis [61].

Chinese medicine compounds consist of complex ingredients that can act on multiple targets and achieve systemic modulatory effects. Therefore, focusing on only a few key genes or proteins may not fully reveal the therapeutic mechanisms of these compounds. Studies using high-throughput gene expression profiling and bioinformatics mining techniques have revealed that Ttpa, Sema3d, Lrp2, Slc22a5, and Plac1 are the direct target genes of ZGP in postmenopausal OP [62]. These genes are involved in the regulation of vitamin E metabolism [63], osteoblast and osteoclast activity [64, 65], and estrogen receptor activity [66], which altogether can affect bone metabolism. Furthermore, ZGP induces a different temporal gene expression profile in BMSCs of ovariectomized rats, primarily characterized by an early downregulation of Ppig, Rb1cc1, and IL-6. ZGP in fact regulates more genes compared to estradiol valerate [67]. Ppig encodes peptidylprolyl isomerase G that catalyzes the cis-trans isomerization of peptidylprolyl and is primarily involved in the regulation of cell cycle and cell proliferation [68]. Rb1cc1 encodes the RB1-inducible coiled-coil protein 1 that regulates lysosomal formation [69]. Finally, IL-6 promotes osteoclast activity and enhances bone resorption via the RANKL-RANK-OPGA pathway [70]. These findings demonstrate that ZGP can influence cell proliferation, autophagy, signal transduction, and cell differentiation to extensively regulate BMSCs gene expression and ultimately reduce bone loss.

In summary, the proosteogenic effects of kidney-tonifying ZGP on BMSCs are mediated through multiple targets and pathways (Figure 2). These results provide scientific evidence for the “kidney dominates bone” theory of TCM and the clinical application of kidney-tonifying recipe for the prevention and treatment of OP.

Figure 2.

The proosteogenic effects of kidney-tonifying ZGP on BMSCs are mediated through multiple signaling transduction pathways, including upregulation of MAPK, Wnt/β-catenin, and TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathways. ZGP can also decrease autophagy activity, promote proliferation, and inhibit apoptosis of BMSCs, strengthening the self-renewal capabilities. ↑: upregulate; ↓: downregulate.

4. Future Directions?

BMSCs have been the main focus of OP pathogenesis and treatment research in recent years. Given that the kidney essence described by TCM shares many similarities with the origin and functions of BMSCs, it is hypothesized that regulation of BMSC osteogenic differentiation may partly be the scientific basis of the kidney-tonifying recipes used in OP treatment. Studies have shown that BMSC differentiation is a complex process and controlled at different stages by various key factors during OP pathogenesis. Therefore, precise regulation of BMSCs will be the next step in OP prevention and treatment. ZGP is a representative kidney-tonifying compound that promotes BMSC proliferation and differentiation into osteoblasts. However, whether the effect of ZGP depends on the stage of BMSC differentiation and whether that would influence the outcome of osteogenic differentiation is still unclear. Therefore, understanding the time and dose effects of ZGP on BMSC osteogenic differentiation will be clinically relevant in the treatment of OP. Although the effect of classic kidney-tonifying compounds on BMSC osteogenic differentiation is still poorly understood, a few preparations such as six-ingredient rehmannia pill, sexoton pill [71, 72], Erxian decoction [73], and Qing'e pill [74] have been shown to promote osteogenic differentiation and inhibit angiogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Therefore, it is important to compare the effects of the different kidney-tonifying compounds on BMSC osteogenic differentiation vis-à-vis OP treatment.

In addition, classic kidney-tonifying formulations can be further classified into the yin or yang promoting compounds; whether these different formulations have different mechanisms and whether that influence osteogenic differentiation will need to be further studied. Most existing studies on kidney-tonifying compounds focus on their osteogenic differentiation-promoting effects, but their effects on BMSC migration, homing, and adipogenic differentiation are less well understood. In fact, enhancement of BMSC migration and homing and the inhibition of BMSC adipogenic differentiation may also be one of the mechanisms by which kidney-tonifying compounds prevent and treat OP. What is more, osteoporosis is closely related to the balance of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Current studies are mainly focused on the effects of ZGP on proosteogenic effects; effects on osteoclast involved in bone resorption are less understood. Several studies indicated that mechanisms of ZGP in inhibiting osteoclast bioactivity are associated with upregulating estrogen levels, decreasing inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-17 that correlated with osteoclast activity [75], and downregulating NFAT2 expression [76]. More focus should be given on the regulation of ZGP on osteoclasts in future studies. Since epigenetic modification plays an important regulatory role in stem cell differentiation, understanding the epigenetics of kidney-tonifying preparations in the induction of BMSC osteogenic differentiation will help further elucidate the scientific basis of these compounds in OP treatment. In addition, serum pharmacology-based metabolomics will also help us elucidate the effective constituents of kidney-tonifying compounds that are involved in the regulation of BMSC osteogenic differentiation.

Acknowledgments

This study was granted by Development Center for Medical Science and Technology National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China (No. W2013ZT120); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81472103)

Contributor Information

Chaochao Yu, Email: kiterunner2@163.com.

Fang You, Email: pretender5@163.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper of this study and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' Contributions

Aofei Yang drafted the manuscript and illustrated the figures, Chaochao Yu contributed to the conception, Fang You revised the manuscript, and Chengjian He and Zhanghua Li provided instructions on osteoporosis and BMSCs issues.

References

- 1.Lane N. E. Epidemiology, etiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;194(2):S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuiling K. D., Robinia K., Nye R. Osteoporosis Update. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2011;56(6):615–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizzoli R., Reginster J.-Y. Adverse drug reactions to osteoporosis treatments. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 2011;4(5):593–604. doi: 10.1586/ecp.11.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner B., Drudge-Coates L., Ali S., et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients receiving bone-targeted therapies: an overview--part I. Urologic Nursing Journal. 2016;36(3):111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Q., Shou P., Zheng C., et al. Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death & Differentiation. 2016;23(7):1128–1139. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X., Wang Y., Gou W., Lu Q., Peng J., Lu S. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in bone regeneration and fracture repair: a review. International Orthopaedics. 2013;37(12):2491–2498. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J., Ko J. A novel PPARγ 2 modulator sLZIP controls the balance between adipogenesis and osteogenesis during mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2014;21(10):1642–1655. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J., Zhao L., Xing L., Chen D. MicroRNA-204 regulates Runx2 protein expression and mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2010;28(2):357–364. doi: 10.1002/stem.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao L., Yang X., Su X., et al. Redundant miR-3077-5p and miR-705 mediate the shift of mesenchymal stem cell lineage commitment to adipocyte in osteoporosis bone marrow. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4(4, article e600) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An Q., Wu D., Ma Y., Zhou B., Liu Q. Suppression of Evi1 promotes the osteogenic differentiation and inhibits the adipogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2015;36(6):1615–1622. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C., Meng H., Wang X., Zhao C., Peng J., Wang Y. Differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in osteoblasts and adipocytes and its role in treatment of osteoporosis. Medical Science Monitor. 2016;22:226–233. doi: 10.12659/MSM.897044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ju D., Liu M., Zhao H., Wang J. Mechanisms of ‘kidney governing bones’ theory in traditional Chinese medicine. Frontiers of Medicine in China. 2014;8(3):389–393. doi: 10.1007/s11684-014-0362-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Y. M., Zhu Y. Y., Ge J. R. Study on the TCM general syndrome of Osteoporosis based on the clinical epidemiological investigation. Shi Jie Ke Xue Ji ShuZhong Yi Yao Xian Dai Hua. 2007;09(02):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao M., Zhuang H., Song W. Z. The surival quality in postmenopausal osteoporosis and its TCM synodromes typing: A primary study. Zhong Yi Zheng Gu. 2000;12(05):9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S., Bi C. C., Sun W. M. Effects of ‘kidney-tonifying’ formulas on bone biomechanics, bone microstructure and bone metabolism in ovariectomized rats. Liao Ning Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2016;43(10):2192–2194. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu W., Zhang L., Wu Y. H. Effects of tonifying kidney and invigorating blood therapy in treating 100 senile osteoporosis patients:a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2015;56(09):769–772. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shu B., Shi Q., Wang Y.-J. Shen (Kidney)-tonifying principle for primary osteoporosis: to treat both the disease and the Chinese medicine syndrome. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2015;21(9):656–661. doi: 10.1007/s11655-015-2306-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker N., Boyette L. B., Tuan R. S. Characterization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in aging. Bone. 2015;70:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ming X., Yu J. E., Li G., Zhang X. G., Wang Y. Discussion on the action mechanism of tonifying kidney medicine in the treatment of asthma: based on the correlation between the Chinese Medical Theory of ‘Kidney Essence’ and mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;57(16):1358–1362. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X.-J. Methodology for systematic analysis of in vivo efficacy material base of traditional Chinese medicine--Chinmedomics. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2015;40(1):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao H.-T., Chen C. T. Osteogenic potential: comparison between bone marrow and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. World Journal of Stem Cells. 2014;6(3):288–295. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i3.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Im G.-I. Bone marrow-derived stem/stromal cells and adipose tissue-derived stem/stromal cells: Their comparative efficacies and synergistic effects. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2017;105(9):2640–2648. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X., Su J. C. New focus on osteoporosis: differentiation fate of bone marrow-derived mesenehymal stem cells. Di Er Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2017;38(04):397–404. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu G., Ren A., Qiu Y., Zhang Y. Epigenetic regulation of osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2016;11(3):235–246. doi: 10.2174/1574888X10666150528153313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H. H., Pan G. C., Cao Y. H. Evaluation of Zuogui Wan efficacy in the 2-years seasonal treatment for primary osteoporosis. Liao Ning Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao. 2015;17(07):160–162. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv H. B., Ren Y. L., Wang Y., Zhao J. R., Liu L. P., Ma X. D. Experimental research of the preventive and therapeutic effect of Zuogui Pill on ovariectomized rats. Zhongguo Gu Zhi Shu Song Za Zhi. 2010;16(11):847–850. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu M. J., Lv G. H., Zhou J., et al. Effects of Zuoguiwan on osteocalcin level in vitro. Zhongguo Zhong Yi Ji Chu Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;13(08):581–582. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qu N. N., Ren Y. L., Sun Y. J., Meng Y. Experimental study of Zuogui pill treatment in ovariectomized rat model of osteoporosis bone loss. Shizhen Guo Yi Guo Yao. 2016;27(02):257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu N. N. Study on The Mechanisms and Material Basis of Zuogui Pill for Osteoporosis in Ovariectomized Rats. Liao Ning University of Chinese Medicine; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warden S. J., Robling A. G., Haney E. M., Turner C. H., Bliziotes M. M. The emerging role of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) in the skeleton and its mediation of the skeletal effects of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) Bone. 2010;46(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henning P., Conaway H. H., Lerner U. H. Retinoid receptors in bone and their role in bone remodeling. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2015;6, article 31 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green A. C., Martin T. J., Purton L. E. The role of vitamin A and retinoic acid receptor signaling in post-natal maintenance of bone. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2016;155:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pope S. A. S., Burtin G. E., Clayton P. T., Madge D. J., Muller D. P. R. Synthesis and analysis of conjugates of the major vitamin E metabolite, α-CEHC. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2002;33(6):807–817. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00974-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujita K., Iwasaki M., Ochi H., et al. Vitamin E decreases bone mass by stimulating osteoclast fusion. Nature Medicine. 2012;18(9):589–594. doi: 10.1038/nm.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mata-Granados J. M., Cuenca-Acebedo R., Luque De Castro M. D., Quesada Gómez J. M. Lower vitamin e serum levels are associated with osteoporosis in early postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2013;31(4):455–460. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bidwell J. P., Alvarez M. B., Hood M., Jr., Childress P. Functional impairment of bone formation in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis: The bone marrow regenerative competence. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2013;11(2):117–125. doi: 10.1007/s11914-013-0139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baxter M. A., Wynn R. F., Jowitt S. N., Wraith J. E., Fairbairn L. J., Bellantuono I. Study of telomere length reveals rapid aging of human marrow stromal cells following in vitro expansion. Stem Cells. 2004;22(5):675–682. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C., Wei G., Gu Q., et al. Donor age and cell passage affect osteogenic ability of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2015;72(2):543–549. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding F. P., Huang J., Zhang J., Xu X. W. Effects of Zuogui Pill on aging rat MSC Morphology. Shizhen Guo Yi Guo Yao. 2011;26(05):1062–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhan F., Zhang C., Huang J. Effect of Zuogui Pill on aging rat MSC Morphology. Shizhen Guo Yi Guo Yao. 2015;26(03):513–515. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhan F., Xu Z. W., Huang J., et al. Effects of Zuogui Pill on proliferation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in aging rat. Zhonghua Zhong Yi Yao Za Zhi. 2015;30(07):2518–2521. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song N., He W. Z., Wang Z. M., Ren Y. L. Effects of serum containing Zuigui pill, Yougui pill and their disassembled prescriptions on the cell cycle and cell apoptosis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in osteogenic differentiation. Zhonghua Zhong Yi Yao Za Zhi. 2013;28(05):1520–1524. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Q. H., Ren Y. L., Wu Q., Ge X. C. Effects of Zuogui Pills and Yougui Pills on Caspase-3/Bcl-2 of BMSCs in ovariectomized rats after osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. Zhong Cheng Yao. 2017;39(10):2004–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kihara T., Oshima A., Hirose M., Ohgushi H. Three-dimensional visualization analysis of in vitro cultured bone fabricated by rat marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;316(3):943–948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin H.-T., Tarng Y.-W., Chen Y.-C., et al. Using human plasma supplemented medium to cultivate human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell and evaluation of its multiple-lineage potential. Transplantation Proceedings. 2005;37(10):4504–4505. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prins H.-J., Braat A. K., Gawlitta D., et al. In vitro induction of alkaline phosphatase levels predicts in vivo bone forming capacity of human bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cell Research. 2014;12(2):428–440. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osathanon T., Manokawinchoke J., Nowwarote N., Aguilar P., Palaga T., Pavasant P. Notch signaling is involved in neurogenic commitment of human periodontal ligament-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells and Development. 2013;22(8):1220–1231. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan C. L., Li S. H., Zhou M. W., Yao Z. Y. An experimental study of the osteoblast differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells by Zuogui pill induction. Zhongguo Gu Zhi Shu Song Za Zhi. 2014;20(10):1154–1158. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu L. X., Gao J., Zhang Q. D. Effect of Zuogui pill medicated serum on level of alkaline phosphatase during differentiation from rat marrow mesenchymal stem cells to osteoblasts. Zhongguo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi. 2011;17(07):149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li L. H., Ding D. F., Du G. Q., Song Y., Shi Y. Y., Zhan H. S. Comparison of Zuogui Pill and Yougui Pill on proliferation and expression of Type I Collagen of rat osteoblasts. Zhongguo Zhong yi gu shang ke za zhi. 2013;21(10):p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li L. H., Zhan H. S., Ding D. F., Du G. Q., Song Y. Effects of Zuogui pill and Yougui pill containing serum on osteogenic differentiation of rat adipose stem cells. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2013;54(22):1941–1944. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang J., Xu Z. W., Zhan F., et al. Efect of Zuogui Pills on osteogenic diferentiation and adipogenic diferentiation of aging rat mesenchymal stem cells. hong Yao Xin Yao Yu Lin Chuang Yao Li. 2015;26(01):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ge X. C., Xu Y., Wu Q., Sun Q. H., Ren Y. L. Effect of Zuogui Wan and Yougui Wan and their disassembled prescriptions on adipogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in ovariectomized rat. Zhongguo Gu Zhi Shu Song Za Zhi. 2016;22(10):1324–1328. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dai R., Wang Z., Samanipour R., Koo K.-I., Kim K. Adipose-derived stem cells for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Stem Cells International. 2016;2016:19. doi: 10.1155/2016/6737345.6737345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu M., Li Y., Pan J., et al. Effects of zuogui pill (see text) on Wnt singal transduction in rats with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2011;31(2):98–102. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6272(11)60020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y., Li Y.-P., Paulson C., et al. Wnt and the Wnt signaling pathway in bone development and disease. Frontiers in Bioscience - Landmark. 2014;19(3):379–407. doi: 10.2741/4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Little R. D., Recker R. R., Johnson M. L., et al. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(12):943–944. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200209193471216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qu N. N., He L. J., He W. Z., Ren Y. L. Effects of serum containing Zuogui Pill, Yougui Pill and their disassembled prescriptions on osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs through p38 pathway. Zhonghua Zhong Yi Yao Xue Kan. 2016;34(06):1326–1329. [Google Scholar]

- 59.He L. J., Song N., He W. Z., Sun Y. J., Chu J., Ren Y. L. The effect of ZuoGuiWan and YouGuiWan induce bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to osteoblast through TGF-β1 /Smad4 signaling pathway. Zhongguo Lao Nian Xue Za Zhi. 2014;34(22):6382–6384. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun Y.-J., Song N., He W.-Z., He L.-J., Ren Y.-L. Effect of Zuoguiwan and Youguiwan on transforming growth factor beta1 and its signal transduction protein Smad2/3 in osteogenic induction of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research. 2014;18(10):1496–1501. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang F., Yang L. X., Li X. Q., Li Y. M. Effect of Zuogui and Yougui pills on neuropeptide CGRP, SP, VIP, and NPY in osteoporotic rats after ovariectomy. Zhongguo Gu Zhi Shu Song Za Zhi. 2016;22(06):761–765. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao X., Hao C. Z., Xu J. W., Yang R. X., Lu F. F. Multi-temporal gene co-expression network analysis in bone mesenchymal stem cells in Zuogui Pill treated ovariectomized rats. Zhong Yao Xin Yao Yu Lin Chuang Yao Li. 2014;30(06):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meier R., Tomizaki T., Schulze-Briese C., Baumann U., Stocker A. The molecular basis of vitamin E retention: structure of human α-tocopherol transfer protein. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;331(3):725–734. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00724-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hughes A., Kleine-Albers J., Helfrich M. H., Ralston S. H., Rogers M. J. A Class III semaphorin (Sema3e) inhibits mouse osteoblast migration and decreases osteoclast formation in vitro. Calcified Tissue International. 2012;90(2):151–162. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9560-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu G.-Y., Qiu Yo., Mao H.-J. Common polymorphism in the LRP5 gene may increase the risk of bone fracture and osteoporosis. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:13. doi: 10.1155/2014/290531.290531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hadji P. The evolution of selective estrogen receptor modulators in osteoporosis therapy. Climacteric. 2012;15(6):513–523. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.688079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao X., Hao C. Z., Yang R. X., Xu J. W. Effect of Zuogui pill on the time sequence of gene expression profile of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in ovariectomized rats. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2015;55(16):1414–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin C., Li H., Lee Y., et al. Landscape of Pin1 in the cell cycle. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2015;240(3):403–408. doi: 10.1177/1535370215570829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DeSelm C. J., Miller B. C., Zou W., et al. Autophagy proteins regulate the secretory component of osteoclastic bone resorption. Developmental Cell. 2011;21(5):966–974. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steeve K. T., Marc P., Sandrine T., Dominique H., Yannick F. IL-6, RANKL, TNF-alpha/IL-1: interrelations in bone resorption pathophysiology. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2004;15(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ge J., Xie L., Chen J., et al. Liuwei Dihuang pill treats postmenopausal osteoporosis with shen (Kidney) Yin deficiency via janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signal pathway by up-regulating cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1 expression. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2018;24(6):415–422. doi: 10.1007/s11655-016-2744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wei J. A., Han L., Cheng Z. A., Sun J., Duan X. D. The effect of Liuweidihuang Wan, Jinkuishenqi Wan and Jianguerxian Wan differentiation-related genes expression in the process of rat BMSCs adipogenic differentiation. Zhong Yao Xin Yao Yu Lin Chuang Yao Li. 2012;28(04):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu S., Huang J., Wang J., et al. Er-Xian Decoction stimulates osteoblastic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells in ovariectomized mice and its gene profile analysis. Stem Cells International. 2016;2016:10. doi: 10.1155/2016/4079210.4079210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shuai B., Shen L., Zhu R., Zhou P. Q. Effect of Qing'e formula on the in vitro differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from proximal femurs of postmenopausal osteoporotic mice. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;15, article 250 doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0777-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li L. P. X. F., Jiang B., Zhang L. C., Huang H., Li R. Effects of Bushen Tianjing recipe on cytokines and osteoclasts activity in Ovariectom ized rats. Liao Ning Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2017;44(09):1982–1984. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu L. P., Li R., Li X. F., Zhang L. C., Zhang L. D. Efect of Bushen Tianjing recipe on the protein expression of NFAT2 in SAMP6 mice. Shizhen Guo Yi Guo Yao. 2017;28(09):2085–2087. [Google Scholar]