Abstract

Increasing rates of burnout—with accompanying stress and lack of engagement—among faculty, residents, students, and practicing physicians have caused alarm in academic medicine. Central to the debate among academic medicine’s stakeholders are oft-competing issues of social accountability; cost containment; effectiveness of academic medicine’s institutions; faculty recruitment, retention, and satisfaction; increasing expectations for faculty; and mission-based productivity.

The authors propose that understanding and fostering what contributes to faculty and institutional vitality is central to preventing burnout during times of change. They first look at faculty vitality and how it is threatened by burnout, to provide a framework for a greater understanding of faculty well-being. Then they draw on higher education literature to determine how vitality is defined in academic settings and what factors affect faculty vitality within the context of academic medicine. Next, they propose a model to explain and examine faculty vitality in academic medicine, followed by a discussion of the need for a greater understanding of faculty vitality. Finally, the authors offer conclusions and propose future directions to promote faculty vitality.

The authors encourage institutional decision makers and other stakeholders to focus particular attention on the evolving expectations for faculty, the risk of extensive faculty burnout, and the opportunity to reduce burnout by improving the vitality and resilience of these talented and crucial contributors. Faculty vitality, as defined by the institution, has a critical role in ensuring future institutional successes and the capacity for faculty to thrive in a complex health care economy.

Increasing rates of burnout—with accompanying stress and lack of engagement—among faculty, residents, students, and practicing physicians have caused alarm in academia and clinical medicine. One of the definitions of burnout1 offers a succinct and insightful picture of faculty burnout in academic medicine:

Exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, usually as a result of prolonged stress or frustration.

An early appearance of the term burnout was in the 1970s in the writings of the American psychologist Herbert Freudenberger.2 He is said to have used that term to describe

the consequences of severe stress and high ideals in “helping” professions. Physicians and nurses, for example, who sacrifice themselves for others, would often end up “burned out”—exhausted, listless, and unable to cope.3

A main contributor to burnout in physicians—and undoubtedly others—is overwork:

Preliminary evidence suggests that excessive workloads … and subsequent difficulties contribute to burnout in physicians.4

There are three main indicators that are thought to be signs of burnout: exhaustion, alienation, and reduced performance.3 Simply stated, when burnout overtakes a faculty member, it effectively saps that individual’s cognitive, emotional, and physical strength.5

We propose that actions that serve to prevent burnout are, wherever feasible, the best individual, leadership, and institutional strategies to embrace. Without prevention, the means to address burnout, once it has taken hold, are likely to require much more intensive resources. We also propose that individual and institutional actions supporting vitality are factors that can help prevent burnout. (We define vitality in a later section.)

In this Perspective, we examine restoring faculty vitality as one of the strategies to reduce burnout. We first look at faculty vitality and how it is threatened by burnout, to provide a framework for a greater conceptual understanding of faculty well-being. Then we draw on higher education literature to determine how vitality is defined in academic settings and what factors affect faculty vitality within the context of academic medicine. Next, we propose a model to explain and examine faculty vitality in academic medicine. This is followed by a discussion of the need for a greater understanding of faculty vitality. Finally, we offer conclusions and propose future directions to promote faculty vitality. We hope this Perspective can serve as a resource for leaders of academic medicine’s institutions to help them foster faculty vitality as a strategy to combat faculty burnout.

Faculty Vitality and Faculty Burnout

Academic medicine’s institutions rely on vibrant, engaged, and motivated faculty for their success. In other words, faculty vitality is crucial for the success of these institutions. From a conceptual standpoint, there are two main factors that contribute to faculty vitality: contextual factors and personal factors. Contextual factors concern the satisfaction of basic psychological needs in the workplace (e.g., degree of autonomy, sense of competence and relatedness). Personal factors include basic needs satisfaction, motivation, and self-efficacy.6,7 These factors are theoretically distinct yet overlap.

Challenging faculty vitality is another force: professional burnout.4 Academic medicine faculty face an enduring battle to function effectively and successfully within an environment of constant and rapid change. Although the faculty role can be incredibly fulfilling, it is a role fraught with tremendous responsibility and an exceptional amount of stress.8 Three factors contributing to this stress, and described below, are changes in health care delivery and financing, increased competition for a declining pool of funds for research and scholarly work, and new models for future physicians, scientists, and other health professions students.

First, health care financing is catalyzing innovations in delivery systems while also introducing changes in reimbursement, thereby having an impact on compensation plans and physician practice incentives.9 New reimbursement models reduce payment rates and require greater productivity for faculty in clinical roles.

Second, medical center mergers, acquisitions, and affiliations are reshaping traditional “ivory tower” academic clinician roles and adding new or different types of academic practice locations. Faculty who engage in research, whether clinical, basic, or translational, face the challenges of an increasingly competitive funding environment, and institutions shoulder greater needs for stewardship and/or oversight to manage potential conflicts of interest associated with private-sector research sponsors.10

Finally, innovations in educational methodology, growing numbers of learners at all levels, increased attention to learners’ mastery of explicit competencies, and the added expectation of developing interprofessional learning opportunities augment pressures on the already-overextended faculty in academic medicine’s institutions and challenge them to continuously adopt new practices. This constant state of change contributes to the reported high levels of professional stress and burnout.11

Defining Vitality in the Academic Setting

Etymology

The etymology of the word vitality is the Latin word vitalis, which in turn is based on the Latin vita, “life.” Some of the definitions of vitality are “exuberant physical strength or mental vigor”; “capacity for survival or for the continuation of a meaningful or purposeful existence”; and “the power to live or grow.”12 A related word, vital, means “essential” and “necessary,” which are important connotations of vitality. Vitality captures the feeling of being alive—a spirit of enthusiasm, energy, and activation.13

Definitions in the academic literature

Late-20th-century higher education researchers credit John W. Gardner14 for the concept of vitality in academia; he postulated conditions necessary for the self-renewal of individuals in society and for the morale of individuals within organizations. In higher education literature, Gardner14 described “vital” faculty as those individuals who actively participate in the governance and intellectual life of their academic institutions and are meaningfully involved in their professional disciplines. Furthermore, vital faculty are curious and intellectually engaged and continue to grow personally and professionally throughout their academic careers. They energetically pursue fresh interests and acquire new skills and knowledge.

In the early eighties, the pivotal work of Clark and Corcoran15 at research-oriented universities revealed that highly active faculty are distinguished from their peers by the finding that these “vital” faculty demonstrate continued productivity in their teaching, research, and professional service activities. Faculty themselves may define vitality differently, based on the context of their experiences.16,17

Faculty vitality applies not only to individual faculty members but also to “the faculty”—that is, the faculty as a group. Evidence of the vitality of an institution’s faculty is rarely demonstrated in isolation. Rather, evidence of a vital faculty body is typically represented through a dynamic interplay with other factors within the institutional environment such as engagement, productivity, and stability.18 The vital institution provides its members with an appropriate level of security and respect to stimulate sustained engagement and academic productivity.19

Ebben and Maher20 defined the vital college as possessing a clearly defined, shared, and accepted mission with attainable, proximate goals; programs to enable fulfillment of the mission; and a climate that empowers individuals to be participants in the fulfillment of the mission. Thus, faculty of vital institutions have a sense of engagement in and contributing to a well-aligned and productive work environment. Institutional vitality21 is the capacity of a college or university to incorporate organizational strategies that support the enduring investment of energy by faculty and staff both in their careers and in the realization of the institution’s mission.

Scholars22–25 have wrestled with the meaning of vitality as it applies to academic medicine’s faculty and institutions. Selected definitions of vitality, as a freestanding concept, as applied to faculty, and as applied to institutions, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of Vitality as a Freestanding Concept and as Applied to Faculty and Institutionsa

| First authorref, year of publication | Term defined | Central idea |

|---|---|---|

| Collins English Dictionary,12 2014 | Vitality | Exuberant physical strength or mental vigor; capacity for survival or for the continuation of a meaningful or purposeful existence; the power to live or grow |

| Gardner,14 1963 | Vitality, renewal, regeneration | Individuals, institutions, and societies that have the capacity for adaptation and change |

| Peterson,25 1967 | Institutional vitality | A multidimensional and dynamic definition, including individual vitality and allowing for institutional differences |

| Smith,24 1978 | Faculty vitality | Interaction of faculty and institutional vitality |

| Ebben,20 1979 | Institutional vitality | Interaction of mission, goals, programs, and institutional climate |

| Clark,15 1985 | Faculty vitality | Sustained productivity in teaching, research, and service activities with focus on faculty as a collective |

| Maher,18 1982 | Institutional vitality | The capacity of a college or university to incorporate organizational strategies that support the investment of energy by faculty and staff in their own careers and the realization of the institution’s mission |

| Clark,19 1985 | Faculty vitality | Individual and organizational variables that distinguish vital faculty from their peers at other institutions |

| Bland,22 1988 | Faculty vitality | A stimulating intellectual environment, the opportunity to be curious and to engage in lifelong learning, is what attracts bright, talented people to academe |

| Baldwin,17 1990 | Faculty vitality | Concept that discriminates among professors in meaningful ways; expanding faculty career development options is key |

| Bland,34 2002 | Faculty vitality | An interplay of faculty qualities and institutional factors |

| Dankoski,35 2012 | Faculty vitality | Synergy between high levels of satisfaction, productivity, and engagement that enables faculty to maximize professional success and achieve goals in concert with institutional goals. Predicted by both individual and institutional factors |

| Pololi,36 2015 | Faculty vitality | Professional fulfillment, motivation, and commitment to ongoing intellectual and personal growth, full professional engagement, enthusiasm and positive feelings of aliveness, energy, and excitement |

Factors influencing faculty vitality

Many of the factors influencing faculty vitality are traceable to the conditions of academic work life and the academic reward system. Schuster26 described the following tangible and intangible correlates that have an impact on the vitality of an institution’s faculty.

Tangible correlates.

Tangible, or direct, correlates are the most concrete factors directly affecting an individual’s immediate work life and work environment. Examples include compensation, academic reward system (promotion and tenure), workload, teaching support, research support, and opportunities for professional development. Each of these direct correlates costs money and may evolve over time. For example, changes in the promotion and tenure processes may occur because concepts of scholarship and academic roles may evolve as the institution repositions and adapts to changes in the higher education, research, and health care industries. Other direct, tangible factors of faculty vitality include investment in faculty career development, measures of faculty satisfaction, and the role of faculty in governance activities.

Intangible correlates.

Intangible, or indirect, correlates are, by comparison, less obvious and include an individual’s perceptions of institutional culture and environment, such as a sense of community, recognition, and being appreciated and valued. Intangible correlates are not monetary and do not have a direct cost but, instead, reflect an individual’s prevailing attitudes and insights about his or her institutional culture.

An equation.

Schuster’s research led to development of an equation,26 shown below, that postulates that faculty vitality results from the combination of the following specific factors:

In this equation, Schuster states that ACP = an administration that cares about faculty, positively communicates that care, and provides purpose and clear direction for the institution;

F1 = a faculty member who is recruited to be lively, to be intellectually acute, and to value colleagueship;

SC = a student body comprising challenging and highly motivated students;

AR1…..n = adequate resources available and accessible to provide a supportive environment (e.g., one that has sabbatical leaves and state-of-the-art technology); and FV = faculty vitality.

The degree or intensity of faculty vitality is affected by the degree or intensity of each of the specific factors. Furthermore, these correlates are dynamic and may change over time even within the same institution. During a time of rapid change in academia, a supportive, collaborative institutional culture and an environment that values the contributions of faculty could become more critical than would be necessary during a time of stability.

Contextual factors that influence faculty vitality

Clark et al19 suggest that faculty vitality is a qualitative, contextual phenomenon that varies in different institutional and disciplinary settings. Contextual indicators of faculty vitality may be institutional or individual. Commonly cited institutional contextual factors of faculty vitality are institutional mission21; work environment27,28; opportunities for growth, advancement,17 leadership, and colleagueship; and customs and rituals.23 Individual contextual factors that have an impact on faculty vitality are closely related to the individual faculty member’s characteristics, attributes, and disposition. Judge et al29 maintain that factors such as motivation, self-esteem, self-efficacy, emotional stability, and the locus and dimensions of core self-evaluation increase an individual’s level of commitment.29 Core self-evaluation— the degree to which an individual feels effective and capable—is particularly important as part of the individual context of faculty vitality.30

The actions of institutional leaders affect direct and indirect factors related to faculty vitality.31 Inconsistencies in these actions can cause disconnect and distress for faculty. For example, in an institution where the mission statement clearly indicates that teaching is one of the school’s highest priorities, but departmental leadership rewards clinical activity and penalizes teaching, faculty are left confused and misdirected, which has a great and corrosive effect on faculty vitality. It is up to the school leadership to establish the proper guidelines for faculty time allocation and to ensure that the guidelines are reflected in all interactions, even on the departmental level. In addition, Shanafelt et al32 further observed that leaders who “inform, engage, and inspire” positively influence faculty vitality. Encouragement from leadership by providing recognition, showing appreciation, and promoting faculty self-esteem is critical in creating, supporting, and maintaining faculty vitality.

Contextual framework for faculty vitality in academic medicine’s institutions

The various institutions in academic medicine—for example, medical schools and teaching hospitals—are not identical. Distinctive characteristics include mission, structure, student body, surrounding community, funding sources, resources, and leadership structure and governance. These institutions also change over time, so that what was true of an institution in the past may not be true in the present. The literature on the culture of academic medicine suggests that faculty often experience a lack of alignment between their own values and perceived institutional values.33 In addition, there is a misalignment between the institutional values that are stated and how well those values play out in reality.

For example, faculty in academic medicine work in one or more of the following areas, each of which requires task-specific resources and coordination: patient care, education, research, and administration. Each area is independently valuable; however, they usually function without significant interdependence.

This “silo effect” accounts for much tension between administrators and faculty. The administrators try to coordinate toward institutional goals, but the faculty sometimes see the administrators’ efforts as bureaucratic constraints hindering their performance and professional goals and reducing autonomy. This kind of conflict damages faculty and institutional vitality. Vitality is more likely to thrive when the institution’s various functions are more integrated and there is an institutionwide understanding and commitment to the academic mission. Vitality also is encouraged when faculty are offered specific resources and commitments when they are recruited, and their institution delivers on those offers and does its best to eliminate obstacles to productivity and professional growth.

Career progression conversations are one suggested method for negotiating alignment with regard to the expectations of faculty and their institution. The career progression conversation is one that can and should evolve over time as conditions and expectations change. By its nature, such a conversation demonstrates interest, suggests partnership, and identifies areas of legitimate shared decision making regarding how faculty talent will be developed and deployed.

The presence or absence of faculty vitality depends on the kind of interplay that exists between faculty, both as a body and as individuals, and institutional factors. Affecting the vitality of faculty life requires identifying those factors and nurturing their best interaction. Self-renewal, morale, and alignment between faculty (both the body and individuals) and institutional interests are the multicontextual dimensions of faculty vitality. Leaders of academic medicine’s institutions would be well advised to integrate these components into faculty recruitment, work assignments, professional development opportunities, and proactive faculty retention initiatives.

A Model to Explain Faculty

Vitality in Academic Medicine

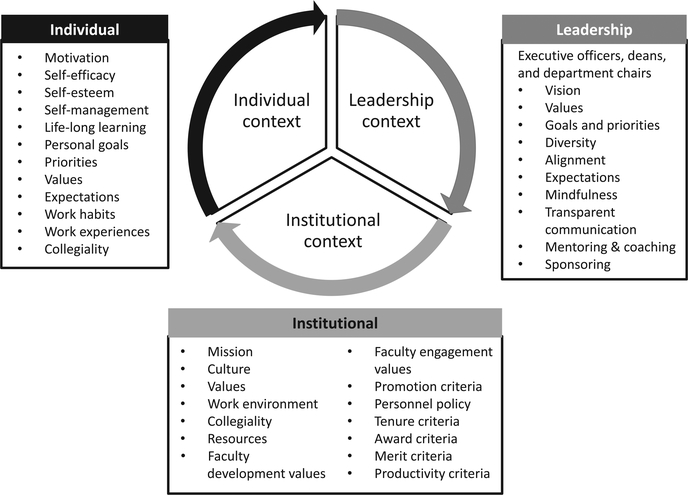

Building on the vitality literature, we propose a model to explain and examine faculty vitality in academic medicine. As depicted in Figure 1, this model consists of three sets of equally important contextual factors of faculty vitality: those centering (1) on the individual faculty member, (2) on the faculty member’s institution, and (3) on institutional leadership. Strong faculty vitality may be found in the institution where all three factors actively align to make intentional, continual progress toward vital faculty and a fulfilled mission. These interrelationships must be consistent over time to ensure sustained institutional and faculty vitality. Of particular note, the relationship among the factors should be fostered and managed more vigorously during a time of change, as maintaining the clarity of mission, congruence of institutional culture, and faculty expectation could become more critical at that time.

Figure 1.

Contextual factors of faculty vitality in academic medicine. In this model, there are three sets of equally important contextual factors: those centering on the individual faculty member, on the faculty member’s institution, and on institutional leadership. Strong faculty vitality may be found in the institution when all three factors actively align to make intentional, continual progress toward vital faculty and a fulfilled mission. Of particular note, the relationship among the factors should be fostered and managed more vigorously during a time of change, as maintaining the clarity of mission, congruence of institutional culture, and faculty expectation could become more critical than would be necessary during a time of stability.

Individual factors

Individual faculty members act on their own behalf based on selecting a place of work that is expected to broadly engage them. Individuals appointed to leadership positions ideally exhibit attributes of motivating, empowering, and influencing others. Individual factors, such as expectations, goal setting, collegiality, and mentoring can be taught and strengthened through faculty development programs.

Institutional factors

Institutional factors encompass the purpose, mission, and values of the organization; the expectations for faculty performance; and how the missions of teaching, research, and patient care are weighed in the reward system. Faculty compensation, workload, and criteria for promotion are tangible correlates that support the institutional mission. Ideal types of faculty vitality and performance emphasis will differ according to institutional type and mission. Situational and contextual aspects must be considered to facilitate faculty members’ commitment and ability to achieve both their individual goals and their institution’s goals. Thus, systematic, multidimensional, individualized approaches to faculty development programs are recommended to replace standardized approaches.

Leadership factors

Complementing and completing both institutional and individual contexts is leadership, which is intricately woven into the fiber of faculty vitality. Leaders at every level, including division and department chairs, deans, and chief executive officers, influence faculty vitality. Although the titles of these roles vary, the characteristics and behaviors expected from individuals in these roles are of great importance. New strategies must be used to identify potential leaders and prepare them for future roles in fostering vital organizations.

Need for a Greater Understanding of Faculty Vitality

Faculty vitality has been examined in the settings of research universities17 and teaching colleges,21 yet few studies have documented the process or metrics necessary to identify, measure, or achieve faculty vitality in academic medicine’s institutions.34–37

Although the existing literature defines faculty vitality broadly, the same literature does not sufficiently cover important phenomena relevant to the interaction between an individual faculty member and the organization. Measures of vitality in higher education do not reflect concern for important qualitative values, including longitudinal perspectives on careers within the organization, development of job-related skills, and relationship building that facilitates a sense of community in shaping the direction of the institution.31,38 In addition, researchers postulate that generalizations based on national data sets do not help individual institutions assess the local factors that may enhance or detract from institutional faculty vitality.22 Given that organizations’ contextual circumstances change, generalizations about institutions and interventions may be informative but not directly transferable or applicable.

Conclusion and Future Direction

The emerging body of scholarship on faculty vitality and its relevance convince us that more assertive institutional initiatives are required to integrate individual, institutional, and leadership contextual factors to enhance faculty vitality. Academic life in academic medicine’s institutions is specialized and unique. Solutions are difficult, but one place to start is making sure that services are adequate and efficient (such as support in clinics, labs, information technology, and core resources), which would make it possible for faculty to be more efficient in all domains. This would allow more time for faculty to balance their activities (e.g., give more time for teaching and scholarly activities) while still generating the necessary clinical revenue. However, in many institutions, support resources are being cut while revenue expectations are the same.

There is no formulaic approach that will guarantee a dynamic and productive career for every faculty member. However, we propose that systematic and mindful use of known contextual factors, intentional periodic examination of individual expectations, and alignment of individual and organizational goals by institutional leadership can positively influence academic, individual, and institutional life. These positive influences on academic life will, in turn, positively influence the career trajectories of faculty and shift the climate toward conditions that create and sustain faculty vitality.

Systematic research is needed to hypothesize further and examine the extent to which faculty vitality is the product of specific intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Such research would serve to clarify the circumstances in which academic medicine’s institutions can effectively nurture faculty vitality through direct intervention. In addition to traditional faculty, there are a growing number of volunteer and part-time faculty who are being called on to serve in educational roles. Very little is known about the specific issues related to the vitality of this important subgroup. This knowledge will be critical in maintaining a strong workforce of community-based educators in the future.

Ultimately, more extensive institution-specific research is needed. Developing a clear understanding of the contextual indicators of vitality may provide useful insight into recruitment, hiring, retention, promotion, and professional development decisions. The future of academic medicine’s institutions is dependent on the future of faculty who provide the talent to carry out the mission-critical work. We encourage institutional decision makers and other stakeholders to focus particular attention on the evolving expectations for faculty, the risk of extensive burnout in this population, and the opportunity to improve the vitality and resilience of these talented and crucial contributors.

Faculty vitality, as defined by the institution, has a critical role in ensuring future institutional successes and the capacity for faculty to thrive in a complex health care economy.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: None reported.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Contributor Information

Darshana T. Shah, Office of Faculty Affairs and Professional Development, Marshall University Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Huntington, West Virginia. She is past chair (2016–2018), Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Faculty Affairs..

Valerie N. Williams, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. She is former associate dean for faculty affairs, University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. She is past chair (2007–2008), Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Faculty Affairs..

Luanne E. Thorndyke, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts. She is past chair (2012–2013), Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Faculty Affairs..

E. Eugene Marsh, Department of Educational Affairs, Penn State College of Medicine, University Park Regional Campus, State College, Pennsylvania. He is a steering committee member, Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Faculty Affairs..

Roberta E. Sonnino, Department of Surgery, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan. She is past chair (2014–2015), Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Faculty Affairs..

Steven M. Block, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He is past chair (2013–2014), Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Faculty Affairs..

Thomas R. Viggiano, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. He is the founding chair (2006–2007), Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Faculty Affairs..

References

- 1.Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Burnout. https://www.merriam-webster.com/ dictionary/burnout. Accessed September 5, 2017.

- 2.Freudenberger H Staff burnout. J Soc Issues. 1974;30:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Depression: What is burnout syndrome? PubMed Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0072470/. Updated January 12, 2017. Accessed September 5, 2017.

- 4.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: A potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA. 2011;305:2009–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lackritz JR. Exploring burnout among university faculty: Incidence, performance, and demographic issues. Teach Teach Educ. 2004;20:713–729. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domain. Can Psychol. 2008;49:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Springer; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvandi Z, Emami A, Zarghi N, Alavinia SM, Shirazi M, Parikh SV. Linking medical faculty stress/burnout to willingness to implement medical school curriculum change: A preliminary investigation. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mijakoski D, Karadzinska-Bislimovska J, Basarovska V, Stoleski S, Minov J. Burnout and work demands predict reduced job satisfaction in health professionals working in a surgery clinic. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3:166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padilla MA,Thompson JN. Burning out faculty at doctoral research universities. Stress and health. J Int Soc Investig Stress. 2016;32:551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller MM, Chang ML, Becker ES, Goetz T, Frenzel AC. Teachers’ emotional experiences and exhaustion as predictors of emotional labor in the classroom: An experience sampling study. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins English Dictionary. Vitality. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/vitality?s=t. Accessed September 5, 2017.

- 13.Deci EL, Connell JP, Ryan RN. Selfdetermination in work organization. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74:580–590. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardner JW. Self-Renewal. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark SM, Corcoran M. Individual and organizational contributions to faculty vitality: An institutional case study In: Faculty Vitality and Institutional Productivity: Critical Perspectives for Higher Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 1985:112–138. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan SS, Burton J. Faculty vitality in the comprehensive university: Changing context and concerns. Res High Educ. 1995;36:219–234. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldwin R Faculty vitality beyond the research university: Extending a contextual concept. J High Educ. 1990;61:160–180. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maher TH. Institutional vitality in higher education. AAHE-ERIC/higher education research currents. AAHE Bulletin. June 1982. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED216668.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark SM, Boyer CM, Corcoran M. Faculty and institutional vitality in higher education In: Faculty Vitality and Institutional Productivity: Critical Perspectives on Higher Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 1985:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebben J, Maher TH. Capturing institutional vitality. Paper presented at: Annual Forum of the Association for Institutional Research; May 1979; San Diego, California. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice RE, Austin AE. High faculty morale: What exemplary colleges do right. Change. 1988;20:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bland C, Schmitz CC. Faculty vitality on review: Retrospect and prospect. J High Educ. 1988;59:190–224. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark SM, Boyer CM, Corcoran M. Faculty and institutional vitality In: Faculty Vitality and Institutional Productivity: Critical Perspectives for Higher Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 1985:7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith DK. Faculty vitality and management of university personnel policies. New Dir Inst Res. 1978;5:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson RE, Loye DE. Conversation Towards a Definition of Institutional Vitality. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuster JH. Faculty vitality: Observations from the field. New Dir High Educ. 1985;51:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalivoda P, Sorrell GR, Simpson RD. Nurturing faculty vitality by matching institutional interventions with career-stage needs. Innov Higher Educ. 1994;18:255–272. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanter RM. Changing the shape of work: Reform in academe. Current Issues in Higher Education. 1979;1:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Judge TA, Locke EA, Durham CC. The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: A core evaluations approach. Res Organ Behav. 1997;19:151–188. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall DT, Nougaim K. An examination of Maslow’s need hierarchy in an organizational setting. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 1968;3:12–35. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanafelt T, Swensen S. Leadership and physician burnout: Using the annual review to reduce burnout and promote engagement. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32:563–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, et al. The impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pololi L, Kern DE, Carr P, Conrad P, Knight S. The culture of academic medicine: Faculty perceptions of the lack of alignment between individual and institutional values. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1289–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bland CJ, Seaquist E, Pacala JT, Center B, Finstad D. One school’s strategy to assess and improve the vitality of its faculty. Acad Med. 2002;77:368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dankoski ME, Palmer MM, Nelson Laird TF, Ribera AK, Bogdewic SP. An expanded model of faculty vitality in academic medicine. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17:633–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pololi LH, Evans AT, Civian JT, et al. Faculty vitality—Surviving the challenges facing academic health centers: A national survey of medical faculty. Acad Med. 2015;90:930–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pololi LH, Dennis K, Winn GM, Mitchell J. A needs assessment of medical school faculty: Caring for the caretakers. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23:21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldwin RG, Blackburn RT. The academic career as a developmental process: Implications for higher education. J High Educ. 1981;52:598–614. [Google Scholar]