Abstract

Comparing West Germany and the United States, we analyze the association between equity - in terms of the relative gender division of paid and unpaid work hours – and the risk of marriage dissolution. Our aim is to identify under what conditions equity influences couple stability. We apply event-history analysis to marriage histories using data from the German Socio-Economic Panel for Western Germany and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics for the United States for the period 1986 to 2009. For the United States, we find that deviation from equity is particularly destabilizing when the wife under-benefits, and when both partners’ paid work hours are similar. In West Germany, equity is less salient. Instead we find that the male breadwinner model remains the single most stable arrangement.

Keywords: equity, norms, couple arrangements, divorce

The ideals and values underpinning marriage have undergone many transformations over the past century. As marriage becomes ever more deinstitutionalized, the conventional obligations that reinforced binding commitments have given way to a gender contract founded more on reciprocity and symmetric roles (Amato, 2004; Cherlin, 2004). Among the principles that govern marital life, the embrace of an equitable division of duties (and leisure) has gained in importance.

Research in psychology and sociology has devoted substantial attention to the impact of conjugal equity on marital quality. Equity theorists (Walster, Berscheid & Walster, 1973), stressing the importance of proportionality between contribution (input) and compensation (outcome) in partners’ exchange, argue that fairness exerts a direct beneficial effect on couple relationships. Some studies confirm this, showing that inequities in the partners’ work contribution foster marital frustration and emotional dissatisfaction (e.g. Hatfield, Rapson & Aumer-Ryan, 2008).

Scholars within the distributive justice approach (Suitor, 1991; Thompson, 1991), suggest that partners’ fairness evaluation may be driven by other justice principles than just proportionality. Here the notion of conjugal justice mirrors underlying normative beliefs regarding how resources should be allocated (Hochschild & Machung, 1989; Greenstein, 1996). Symbolic meanings attached to the division of paid and unpaid work are expected to influence partners’ fairness evaluation (Hegtvedt & Markovsky, 1995). In line with this conceptualization, empirical evidence consistently shows that it is when individuals perceive their relationship as inequitable that they experience a decrease of marital quality (Hatfield, Traupmann, Sprecher, Utne, & Hay, 1985; Sprecher, 1986; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990).

Even if comparative studies show that societal beliefs shape partners’ fairness principles regarding work (Fuwa, 2004; Geist, 2005; Hook, 2006), only few examine how the normative context moderates the way that spousal work allocation affects marital outcomes. Exceptions are Braun, Lewin-Espstein, Stier and Baumgärtner (2008) and Ruppanner (2010; 2012), whose cross-national studies demonstrate that women embedded in a more gender egalitarian context report higher levels of marital conflict when the partners’ division of work is unfair than do those who live in more traditional environment. These studies provide valuable insights into cross-country variation in marital dissatisfaction as result of a disproportional allocation of partners’ work; but they do not explore the extent to which it also may provoke more severe responses, such as divorce.

Our aim is to fill these gaps in two ways. Firstly, we opt for a comparison of two societies, West Germany and the United States, which differ greatly in terms of the norms that underpin the allocation of work within partnerships. They represent contrasting patterns as regards both female employment and the diffusion of gender egalitarianism, two contextual factors which are likely to exert a decisive influence on fairness principles in intimate relationships (Geist, 2005; Hook, 2006; Knudsen & Wærness, 2008). This cross-national contrast emerges clearly from trends in gender attitudes based on the World Value Survey and European Value Study of the 1990s. As illustrated in Figure 1, attitudes towards gender roles are very dissimilar in the two countries: more than 50% of West German respondents, compared to only 25% in the US, did not recognize the importance of sharing household chores in marriage; about two third of Western Germans, but less than one third in the US, agreed that “being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for pay”; and, again, slightly less than 80% of Western German respondents but only 45% of the US believed that “a pre-school child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works” (our elaborations).

Figure 1. West German and American attitudes toward gender roles.

Note: Based on 1990s EVS and WVS data, reflecting mean country scores on the questions ranging from 1, strongly agree, to 5, strongly disagree.

Secondly, by using longitudinal data we are able to focus on a marital outcome, namely divorce, which is rarely examined in the literature related to equity theory. In this way we can better identify the dynamics which produce marital dissolution, expanding the limited research on the impact of couple inequities on marital instability.

We address these issues applying event history analysis for the period 1986–2009 in West Germany and between 1986 and 2010 in the United States. We utilize the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP, 2009) and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID, 2016). Both report information on the partners’ paid and unpaid work hours.

The paper is structured as follows. We begin with a review of theories addressing the link between equity and marital instability. Here we focus on equity theory and the distributive justice approach. We then formulate our research hypotheses, and describe our data, methodology and the variables we include. We subsequently present our empirical analyses and, finally, we conclude.

Equity as Proportionality: Does it Matter for Marital Stability?

According to the proportionality principle of justice, as defined by Walster and colleagues (1973), equity is structured around the principle of fair exchange; that is, the outcomes of all parties involved in an exchange are proportional to their inputs.

Applied to intimate relationships, a fair exchange implies that each partner receives rewards that are commensurate to his or her contribution (Walster et al., 1973). In this version of equity theory, hereafter simply referred to equity theory, equity rules require that more benefits will be allocated to the partner whose inputs are greater (the contribution rule). The distribution of time and tasks is a key element in partners’ exchange (Thompson, 1991; Mikula, 1998).1 The relative time they dedicate to paid and unpaid tasks represents the benchmark for their evaluation of fairness (Berger, Zelditch, Anderson, & Cohen, 1972; Kalmijn & Monden, 2012). The member who contributes more to paid work is accordingly entitled to devote proportionally less time to unpaid work.2

In this framework, an equitable allocation of outputs according to inputs is seen as essential for marital harmony and marital satisfaction.3 A long research tradition, focused primarily on the United States, has confirmed that proportionality in the division of duties can generate positive marital outcomes, such as wellbeing and marital satisfaction (e.g. Glass & Fujimoto, 1994; Bird, 1999; Gager, 2008). Accordingly, when individual expectations of proportionality are unfilled, a partner may experience a sense of injustice which, in turn, can provoke marital conflicts (Stafford & Canary, 2006; DeMaris, 2007, 2010). Following this reasoning, inequitable relationships may also face a higher risk of divorce.

A corollary of this theory is that the proportionality principle is universally recognized and embraced (Cook and Hegtvedt 1983): equity is a normative rule of thumb that guides social behavior.4 Hence, if a relationship suffers from imbalances between partners’ contributions and rewards, the couple’s members will see it as inequitable independently of the groups, organization or social contexts to which they belong.5

The equity-as-proportionality perspective would lead us to expect that couples’ divorce risk increases with the degree of inequity. This association should not vary across societies (Hypothesis 1).

The Role of Cultural Norms

Equity theory-as-proportionality tends to neglect the partners’ lives are socially embedded (Adams, 1963, 1965; Homans, 1974, 1976). The distributive justice model, going beyond the conceptualization of equity of Walster et al (1973), argues that the principle of proportionality does not represent the only criterion for assessing equity in couple allocation (Thompson 1991; for a critical review of Walster et al [1973], see Sampson 1975). Thompson’s distributive justice model (1991), hereafter referred to as the distributive justice model, stresses that the identification of alternative distribution parameters is necessary to understand partners’ fairness evaluations.

The multidimensional approach of the distributive justice model makes the role of normative rules explicit, emphasizing that evaluations of justice are also driven by symbolic meaning (Thompson, 1991). According to Thompson (1991), a full understanding of partners’ sense of fairness requires therefore an analysis of different dimensions, such as the referents the partners use, the kinds of contributions they consider, and how they rate contributions.

Let us begin with a focus on the first element, the comparison referent. In Walster et al’s (1973) equity theory it is a priori assumed that the spouse constitutes the comparison referent to evaluate whether the division of work is fair (Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990). Distributive justice scholars, in contrast, argue that partners’ comparison referents are socially derived (Thompson, 1991; Kluwer & Mikula, 2003). Partners’ cultural context exerts a profound impact on their choice of comparison (Greenstein, 2000).

Conventional sex-role views typically produce a gendered allocation of time (Bittman. England, Sayer, Folbre, & Matheson, 2003): the wife is seen as the primary caregiver and the husband as the main breadwinner (Hood, 1983). In this context, the female partner will be less inclined to judge outcomes based on a comparison with the male partner and, instead, will be more likely to compare herself with other women (and their husband with other men). This implies that wives may perceive a division of work as fair even if their total work contribution exceeds that of their spouse (female under-benefiting).6

In this framework, women may identify housework as a positive outcome per se. Caring for loved ones may symbolically represent an intrinsically positive value (Hochschild & Machung, 1989) that leads wives to affirmative feelings such as familial approval, domestic peacefulness, and self-satisfaction (Mikula, 1998). In fact, studies have shown that women who take the responsibility for housework and child-care, either as housewife or as employed, are likely to experience an improvement of marital quality (Molm & Cook, 1995; Cherlin, 2000; Bittman et al., 2003). Consequently, a female over-performance in domestic work in such a context can be expected to be beneficial for marital stability, while the opposite is expected in the case of non-normative behavior - e.g. a similarity in the partners’ division of paid an unpaid work.

Recent studies have documented cross-culture variation in the degree of support for gendered role attitudes (Hatfield et al., 2008). In some societies, such as West Germany, the normative legitimacy of a traditional gender-based division of work persists (Breen & Cooke, 2005); in others, such as the U.S., it has eroded (Schwartz & Han, 2014). Indeed, research focusing on the U.S. suggests that societal support for the conventional gendered division of housework has weakened (Cotter, Hermsen, & Vanneman, 2011). In parallel, a significant rise in the adoption of gender egalitarian attitudes has been experienced (Schwartz & Han, 2014).

The diffusion of new values is likely to change the way women evaluate and judge fairness in the allocation of housework (Berger et al., 1972). In the US, the new model of reciprocal partnerships based on an active involvement of both partners in the various responsibilities of married life is becoming dominant (Cooke, 2006). This implies that partners will alter their comparison referent in favour of a more gender-symmetric division of work. In other words, women in the U.S. are likely to re-define the comparison referent, and to increasingly compare their work burden with that of their male partner rather than with other women (Gager & Hohmann-Marriott, 2006).

There is some evidence for the US that partners who adopt a symmetric model of marriage are more likely to share similar workloads and responsibilities; this, in turn, is associated with greater marital intimacy and emotional work (Amato, Johnson, Booth & Rogers, 2003; Dush & Taylor, 2012). And this should enhance couple stability.

In both countries considered, male over-performance in the division of the couple’s combined workload is seen as non-normative. As a consequence, female over-benefiting should induce higher divorce risks also in the U.S.

This leads us to Hypothesis 2: We expect that in West Germany the more the female partner under-benefits (contributing more than receiving), the lower the risk of divorce. This should not be the case for US, where we expect that female under-benefiting will heighten marital instability. In both countries we should expect higher divorce risks when the wife over-benefits.

In sum, for the US (but not for West Germany) we expect that an equitable division of paid and unpaid work is the best insurance against divorce.

Paid Work, Equity, and Divorce in Their Cultural Context

As we have already reported, the multidimensional approach of distributive justice stresses that, apart from comparison referent, partners’ sense of fairness requires an analysis of other dimensions that the partners assess, outcome values and justifications.

While equity theorists assume a priori that unpaid work is valued (and preferred) as much as paid work by both partners, distributive justice scholars suggest that, under certain circumstances, this equivalence is not given (Gager, 1998). Where domestic work continues to be defined as the proper female domain, one should expect that – for women – paid work will be valued less than their unpaid work (Thompson, 1991; DeMaris & Longmore, 1996).

Even if women’s gainful employment is now broadly accepted, research has shown that in more gender-traditional societies (e.g. West Germany) women demonstrate grater affection for home and children – also in the case they are employed (Hochschild & Machung, 1989; Heimer & Staffen, 1998). In this context women, employed or not, may value domestic activities more because these are perceived as socially desirable (Mikula, 1998). This may result in a mismatch between the value assigned to female paid (less valued) and unpaid work (more valued). As a consequence, working wives are likely to perceive their disproportionately large input into domestic or caring work as fair (Thompson, 1991).

In the gender traditional context it may indeed be viewed negatively if a couple adopts a symmetric division of unpaid and paid work (Wilcox & Nock, 2006). Under such conditions, full-time employed women may accept inequity since domestic work is perceived as the most valued female responsibility. And this, in turn, should help stabilize the marriage (Molm & Cook, 1995; Cherlin, 2000; Bittman et al., 2003).

In gender egalitarian nations where female full-time employment is more normative, as in the US (Cooke et al., 2013), women are expected to value their time dedicated to paid work at least as highly as their time dedicated to unpaid work (Ruppanner, 2008). In this normative context we should also expect that husbands’ contribution to household tasks will be assigned a value similar to that of wives’ (Gager & Hohmann-Marriott, 2006; Gager, 2008). This logic emerges from recent US studies which show that employed women, especially if full-timers, express dissatisfaction when the husband contributes little to housework since a higher baseline of male partner’s household participation is expected (Van Willingen & Drentea, 2001; Cherlin, 2000, 2004; Yodanis, 2010; Ruppanner, 2010).

Consequently, where gender-egalitarianism reigns, employed women will be less satisfied with family life when they experience a lack of fairness in the conjugal division of paid and unpaid work (Amato et al., 2003). And this may induce the female partner to exit the relationship (Olah & Gahler, 2014).

This leads us to Hypothesis 3: in West Germany we expect a lower risk of divorce in couples where employed women under-benefit (contributing more than receiving); this should especially be the case for couples where both spouses dedicate similar hours to paid work. In contrast, we expect a stability premium for US couples that share equally both paid and unpaid works.

Data, Methods and Variables

Analytical Sample and Data

Both the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) are representative surveys that contain annual information on marital history, partners’ employment, the division of paid and unpaid work, as well as a number of socio-demographic characteristics. Weekly (PSID) or daily (GSOEP) data for the amount of paid and unpaid work hours for each member are collected for all the waves in both datasets. However, there are some measurement differences. In the GSOEP, time dedication data is provided by each partner; in the PSID, it is the head of the household who responds on behalf of the spouse (in a vast majority of cases, the head is the husband). Moreover, the PSID does not report information on parental childcare.7 As a consequence, our comparisons focus only on domestic work.

The GSOEP began in 1984 with a representative sample (interviewed annually).8 We exclude Eastern Germany since it only entered into the GSOEP after 1990.9 The PSID started in 1968.10 Interviews were collected on an annual basis until 1997 and biennially thereafter. In order to obtain a comparable time frame, we analyze the years 1986–2010 for the PSID and the years 1986–2009 for the GSOEP.

We examine only married heterosexual couples with respondents older than 18 and younger than 50 years, so as to capture a period in marital life when the division of paid and unpaid work is likely to be more determinant for marital quality (Higgins, Duxbury, & Lee, 1994; Jacob & Gerson, 2004; Van der Lippe, 2007). We identify marital histories by combining retrospective and panel information. The start of the relationship can occur before the first year of our observational window: a balanced sample (composed only of couples followed from the first year of marriage) would reduce the sample size to few couples. For this reason, the onset of risk can range from the first to the twentieth couple-year. When the start of the partnership does not correspond to the actual first year of observation (left-truncated), we report the duration using the actual marriage starting date. Marriage episodes are right-censored at any of the following events: age 50, 20 years of marriage duration, or last available interview (due to separation or death). The dependent variable takes the value of 1 for the year in which a marital separation occurs and zero otherwise.11

These restrictions produce a final sample of 5220 couples for the GSOEP, and 6581 for the PSID (an analytical sample of, respectively, 30432 and 46920 couple-years). We observe 387 episodes of marital dissolution in West Germany, and 1201 in the United States.

Explanatory Variables

Inequity

Our key explanatory variable is the degree of objective inequity in spousal time allocation to paid and unpaid work taken simultaneously. To identify the degree of objective inequity, we identify the spousal allocation of time calculating the relative measures of paid and unpaid work as follow.12

To measure the relative distribution of couples’ paid work, we use the percentage of time (0–100) that the male dedicates to the total weekly paid work of both partners.

As above, we use the male’s share of unpaid work relative to the weekly total of the couple to measure the relative distribution of couples’ unpaid work. In the PSID, the housework hours are measured at the time of the survey by asking the respondent how many weekly hours, on average, does each spouse dedicate to housework.13

Objective inequity is measured on the basis of the sum of the partners’ relative paid and unpaid work hours. The measure captures the proportionality principle, i.e. the ratio of outcome to input should be the same for each partner. This has been employed in prior research (DeMaris, 2010; Esping-Andersen, Boertien, Bonke, & Gracia, 2013).

If Ph represents the husband’s paid hours, Pw the wife’s paid hours, Dh the husband’s domestic work hours and Dw the wife’s domestic work hours, we define objective inequity as follows

The objective inequity measure is continuous and ranges from 0, (in the case where the husband’s relative contribution to paid work is equal to wife’s relative contribution to unpaid work) to 1, in the case where one member’s relative contribution to paid and unpaid work is zero. Considering the realities of daily life (like arriving late because of traffic jams), we allow for a (+/−) .10 deviation from perfect proportionality (that corresponds to the value of 0) – as did Nock (2001) and Esping-Andersen et al. (2013). We term this equity space. The greater is the distance away from the equity space, the higher is the inequity value.

Figure 2 illustrates this graphically. Since couples are (objectively) equitable when the male share of paid work corresponds to the female share of unpaid work hours, this means that equitable couples will fall on a declining diagonal slope of 45 degrees with regard to paid working hours. The equity space is identified in blue. To give some examples: an equitable couple is one where the husband accounts for 80% of all paid work hours, and the wife for 80% of all unpaid work hours (see the diamond-shaped marker in Figure 2); here the inequity variable takes the value of 0. A couple is considered inequitable if, instead, the proportions were, respectively, 40% and 60% (see the circle-shaped marker in Figure 2); in this case the inequity variable would take the value of 0.2.

Figure 2.

Representation of the equity space.

Female over- and under-benefiting

If a couple is located above the ‘equity space’ we are observing a case of female over-benefiting: the sum of the husband’s share of paid and unpaid work hours exceeds hers. If, instead, a couple falls below the equity space, the female is under-benefiting: the sum of the husband’s work shares is lower than hers.

To identify the gendered effects of inequity on divorce, we use a spline-regression to distinguish the objective equity variable between couples where the wife is over-benefiting from where she is under-benefiting14. The spline-regression allows us to estimate distinct coefficients for different ranges of the equity variable.

The Over- and under-benefiting variables are continuous measures and are constructed as follows: the wife’s under-benefiting is equal to the inequity measure (|(Ph/Ph+Pw)+(Dh/Dh+Dw)-1|) when her relative contribution is greater than .1 deviation from the husband’s, and takes the value of zero otherwise. The wife’s over-benefiting is equal to the inequity measure (|(Ph/Ph+Pw) + (Dh/Dh+Dw)-1|) when his relative contribution is higher than .1 deviation of the wife’s, taking the value of zero otherwise.

The partners’ contribution to paid work

To identify the division of paid work, we construct a continuous variable. As before, if Ph represents the husband’s paid hours, Pw the wife’s paid hours, we define the degree of specialization as [Ph/(Ph+ Pw)]. The specialization variable takes the value of 1 when the husband is the sole breadwinner and 0 when the wife is the sole breadwinner.

Controls

We include the standard control variables used in divorce studies (see Lyngstad & Jalovaara, 2010): whether the current marriage is the first, years of marriage and its squared term, the wife’s age at marriage and its squared term, and the age difference between the partners (whether he is older less than or equal to 5 years, whether she is older, and whether he is older more than 5 years).

We also include both partners’ level of education. We use the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), and distinguish three categories: lower secondary education or less (ISCED 1 and 2), upper secondary education or post-secondary non tertiary education (ISCED 3 and 4), and completed tertiary education (ISCED 5 and 6). The West German variable in GSOEP is already coded with ISCED. Applying ISCED to PSID for the United States, the corresponding levels are: less or equal to 9th grade, between 10th grade and 15th grade (which corresponds to some high-school and some college or a two-year college degree), and 16 years or more (four-year college degree or more).

In the US models only, we also control for race, distinguishing white, Afro-Americans, and ‘other’ (Hispanics, Asians and other ethnicities). The PSID has begun to distinguish ethnicity from race, but to ensure consistency we use the original classification. Unfortunately, we do not have any corresponding ethnicity variable in the German data. As a consequence, we omit the race variable in the models that pool both countries.

We control also for the couple’s total paid and unpaid hours since this is standard practice in the divorce literature. Finally, we control for the number of children. Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive statistics for the main variables for the two countries.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for West Germany

| West Germany | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inequity level | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Wife is under-benefitted | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Wife is over-benefitted | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Husband’s share of paid work | 0.75 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Log of marriage duration | 2.07 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Couple’s total hours of paid work | 59.10 | 21.49 | 1.00 | 238.00 |

| Couple’s total hours of housework | 31.01 | 18.03 | 1.00 | 190.00 |

| First marriage | 0.98 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Wife’s age at marriage | 23.79 | 4.93 | 16.00 | 40.00 |

| Marriage year (0 = 1970) | 20.01 | 7.77 | 0.00 | 39.00 |

| Number of children in the household | 1.51 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 10.00 |

|

| ||||

| Age difference (ref. Same age) | ||||

| Wife is older | 11.98 | |||

| Wife is younger | 22.92 | |||

| Wife’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | ||||

| ISCED 3–4 | 58.20 | |||

| ISCED 5–6 | 21.43 | |||

| Husband’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | ||||

| ISCED 3–4 | 53.04 | |||

| ISCED 5–6 | 31.38 | |||

Note: SD = Standard deviation.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the United States

| United States | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inequity level | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Wife is under-benefitted | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Wife is over-benefitted | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Husband’s share of paid work | 0.64 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Log of marriage duration | 2.01 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Couple’s total hours of paid work | 73.44 | 23.38 | 1.00 | 201.00 |

| Couple’s total hours of housework | 27.08 | 17.66 | 1.00 | 200.00 |

| First marriage | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Wife’s age at marriage | 24.70 | 4.93 | 13.00 | 40.00 |

| Marriage year (0 = 1970) | 18.99 | 8.53 | 0.00 | 40.00 |

| Number of children in the household | 1.61 | 1.20 | 0.00 | 10.00 |

|

| ||||

| Age difference (ref. Same age) | ||||

| Wife is older | 19.81 | |||

| Wife is younger | 14.96 | |||

| Wife’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | ||||

| ISCED 3–4 | 66.50 | |||

| ISCED 5–6 | 30.29 | |||

| Husband’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | ||||

| ISCED 3–4 | 67.20 | |||

| ISCED 5–6 | 28.53 | |||

| Wife’s race (ref. White) | ||||

| African-American | 20.68 | |||

| Other | 8.09 | |||

Note: SD = Standard deviation.

To illustrate nation differences, we present the relative distribution of couple-years according to the combined shares of domestic and paid hours, and how they cluster around the ‘equity space’ (Figure 3 and 4). These are heat maps which graphically depict the husband’s relative participation in paid work and the wife’s relative contribution to housework. Each cell represents the percentage of couples in terms of how they divide paid and unpaid work. In Figure 2, for example, the bottom right corner cell shows that 8.83% of West German couple-years represent a division of paid and housework hours where the husband accounts for 90–100% of paid work, a nd the wife for 90–100% of housework. The colour of the cell indicates the density of each couple arrangement – measured as the percentage over all couple arrangements in the country; the darker, the greater is the incidence.

Figure 3. The distribution of couple-years according to the combined shares of housework and paid work hours. West Germany.

Note: dark grey squared represents higher density of couples, while light grey squared represents lower density.

Figure 4. The distribution of couple-years according to the combined shares of housework and paid work hours. United States.

Note: dark grey squared represents higher density of couples, while light grey squared represents lower density.

We observe that couples in both countries tend to concentrate in the right half of the quadrant: i.e. female dominance in the labor market and male dominance in the housework are uncommon in both cases. But honing in on the details, we see noticeable differences with regard to paid work. Firstly, German wives’ relative participation in the labor market is significantly lower than the US ones: a larger share of German couples concentrates in the bottom right corner. To illustrate, the husband’s share of paid work is over 60% in the majority (70.8%) of German couple-years; in comparison it accounts for only 42.5% in the US. In the US, the distribution of couple-years is biased towards dual-earner couples: the share of couples where the husband accounts for 40–60% of all paid work is 50.8%, compared to only 25% in West Germany.

Estimation

We apply discrete-time event history analysis using logistic regression (for a review, see Allison, 1982). We favour this over continuous-time estimation for several reasons. First, the divorce dates are recorded to the nearest month or year. Second, all the explanatory variables are measured annually. Discrete-time is the logical choice also because it allows us to include our time-varying covariates in a simple way and to account for the fact that divorce dates are measured discretely.

The discrete-time divorce hazard function can be defined as the probability pti that an individual i experiences an event during the year t, given that no event occurred before the start of year t. We can think of the divorce hazard function as an approximation of the continuous hazard function. The models are estimated using logistic regression to fit the binary response model: yti = log(pti / (1-pti)) = αDti+ βXti, where Dti measures the cumulative duration function and Xti is a set of covariates. We specify the time-dependency of the hazard by defining Dti as the logarithmic function of the duration. This functional form was chosen so as to best fit the data. Finally, because our models include repeated events, we cluster the errors around the couple unit.

We divide the empirical part into three sections. In the first, we will test the association between inequity and divorce (Hypothesis 1). We will then present results related to Hypothesis 2, i.e. whether a more inequity in the case of female under-benefiting (over-benefiting) reduces (increases) the likelihood of divorce (Hypothesis 2). Finally, we will examine whether there are differences related to the degree of female under-benefiting within different couple arrangements (Hypothesis 3).

For dual earner couples with similar paid workloads in the US, we expect to find that the divorce risk increases the more that the female is under-benefiting. For West German couples whose members have similar paid workloads, we expect the opposite. Here the risk of divorce should be lower when the employed woman contributes disproportionally to housework – and in a sense, the acid test here pertains to couples with similar levels of spousal paid work hours.

We present estimates for West Germany in Model 1 and for the US in Model 2. We subsequently estimate a pooled model that includes an interaction between country and our main explanatory variable(s) (Tables 3, 4 and 5).

Table 3.

Inequity level and divorce risks in West Germany and in the United States

| West Germany | United States | Pooled | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | Robust SE | eβ | β | Robust SE | eβ | β | Robust SE | eβ | |

| Objective Equity | −0.017 | [0.271] | 0.983 | 0.579 | [0.146]*** | 1.784 | 0.700 | [0.145]*** | 2.014 |

| West Germany (ref. US) | −0.434 | [0.096]*** | 0.648 | ||||||

| West Germany × Inequity | −0.824 | [0.304]** | 0.439 | ||||||

| Log of marriage duration | −0.018 | [0.076] | 0.982 | −0.147 | [0.043]*** | 0.863 | −0.141 | [0.037]*** | 0.868 |

| Couple’s total hours of paid work | 0.006 | [0.002]** | 1.006 | −0.001 | [0.001] | 0.999 | 0.001 | [0.001] | 1.001 |

| Couple’s total hours of housework | −0.001 | [0.003] | 0.999 | −0.009 | [0.002]*** | 0.991 | −0.008 | [0.002]*** | 0.992 |

| First marriage | −0.584 | [0.312] | 0.558 | −0.520 | [0.091]*** | 0.595 | −0.387 | [0.084]*** | 0.679 |

| Wife’s age at marriage | −0.079 | [0.088] | 0.924 | −0.254 | [0.051]*** | 0.776 | −0.184 | [0.044]*** | 0.832 |

| Wife’s age at marriage sq. | 0.001 | [0.002] | 1.001 | 0.003 | [0.001]*** | 1.003 | 0.003 | [0.001]** | 1.003 |

| Marriage year (0 = 1970) | 0.103 | [0.033]** | 1.108 | 0.086 | [0.017]*** | 1.090 | 0.083 | [0.015]*** | 1.087 |

| Marriage year sq. | −0.002 | [0.001]* | 0.998 | −0.002 | [0.000]*** | 0.998 | −0.001 | [0.000]*** | 0.999 |

| Age difference (ref. Same age) | |||||||||

| Wife is older | 0.398 | [0.155]* | 1.489 | 0.210 | [0.080]** | 1.234 | 0.225 | [0.071]** | 1.252 |

| Wife is younger | 0.084 | [0.126] | 1.088 | 0.185 | [0.081]* | 1.203 | 0.123 | [0.067] | 1.131 |

| Wife’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | |||||||||

| ISCED 3–4 | −0.114 | [0.135] | 0.892 | 0.714 | [0.237]** | 2.042 | 0.264 | [0.111]* | 1.302 |

| ISCED 5–6 | −0.039 | [0.183] | 0.962 | 0.456 | [0.252] | 1.578 | 0.040 | [0.133] | 1.041 |

| Husband’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | |||||||||

| ISCED 3–4 | −0.026 | [0.145] | 0.974 | 0.061 | [0.168] | 1.063 | 0.090 | [0.107] | 1.094 |

| ISCED 5–6 | −0.484 | [0.186]** | 0.616 | −0.521 | [0.189]** | 0.594 | −0.495 | [0.127]*** | 0.610 |

| Number of children in the household | 0.009 | [0.056] | 1.009 | 0.104 | [0.026]*** | 1.110 | 0.107 | [0.023]*** | 1.113 |

| Constant | −3.901 | [1.194]** | 0.020 | −0.607 | [0.721] | 0.545 | −1.440 | [0.593]* | 0.237 |

|

| |||||||||

| Person-years | 30,432 | 46,920 | 77,352 | ||||||

| Couples | 5,220 | 6,581 | 11,801 | ||||||

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Model 2 includes race as a control variable. SE = Standard error.

Table 4.

Inequity direction in West Germany and in the United States

| West Germany | United States | Pooled | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | Robust SE | eβ | β | Robust SE | eβ | β | Robust SE | eβ | |

| Wife is under-benefitted | 0.050 | [0.373] | 1.051 | 0.735 | [0.147]*** | 2.085 | 0.849 | [0.147]*** | 2.337 |

| Wife is over-benefitted | −0.072 | [0.327] | 0.931 | −0.145 | [0.256] | 0.865 | 0.029 | [0.250] | 1.029 |

| West Germany (ref. US) | −0.461 | [0.096]*** | 0.631 | ||||||

| WG × Wife is under-benefitted | −0.381 | [0.390] | 0.683 | ||||||

| WG × Wife is over-benefitted | −0.718 | [0.367] | 0.488 | ||||||

| Log of marriage duration | −0.020 | [0.076] | 0.980 | −0.161 | [0.043]*** | 0.851 | −0.152 | [0.037]*** | 0.859 |

| Couple’s total hours of paid work | 0.006 | [0.002]* | 1.006 | −0.003 | [0.001] | 0.997 | −0.001 | [0.001] | 0.999 |

| Couple’s total hours of housework | −0.001 | [0.003] | 0.999 | −0.009 | [0.002]*** | 0.991 | −0.008 | [0.002]*** | 0.992 |

| First marriage | −0.581 | [0.313] | 0.559 | −0.520 | [0.091]*** | 0.595 | −0.387 | [0.084]*** | 0.679 |

| Wife’s age at marriage | −0.079 | [0.088] | 0.924 | −0.258 | [0.051]*** | 0.773 | −0.187 | [0.044]*** | 0.829 |

| Wife’s age at marriage sq. | 0.001 | [0.002] | 1.001 | 0.004 | [0.001]*** | 1.004 | 0.003 | [0.001]** | 1.003 |

| Marriage year (0 = 1970) | 0.103 | [0.034]** | 1.108 | 0.087 | [0.017]*** | 1.091 | 0.084 | [0.015]*** | 1.088 |

| Marriage year sq. | −0.002 | [0.001]* | 0.998 | −0.002 | [0.000]*** | 0.998 | −0.001 | [0.000]*** | 0.999 |

| Age difference (ref. Same age) | |||||||||

| Wife is older | 0.399 | [0.155]* | 1.490 | 0.210 | [0.080]** | 1.234 | 0.225 | [0.071]** | 1.252 |

| Wife is younger | 0.083 | [0.126] | 1.087 | 0.181 | [0.081]* | 1.198 | 0.120 | [0.068] | 1.127 |

| Wife’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | |||||||||

| ISCED 3–4 | −0.112 | [0.135] | 0.894 | 0.706 | [0.237]** | 2.026 | 0.267 | [0.111]* | 1.306 |

| ISCED 5–6 | −0.037 | [0.184] | 0.964 | 0.449 | [0.251] | 1.567 | 0.045 | [0.133] | 1.046 |

| Husband’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | |||||||||

| ISCED 3–4 | −0.025 | [0.145] | 0.975 | 0.074 | [0.168] | 1.077 | 0.099 | [0.107] | 1.104 |

| ISCED 5–6 | −0.481 | [0.186]** | 0.618 | −0.485 | [0.189]* | 0.616 | −0.469 | [0.128]*** | 0.626 |

| Number of children in the household | 0.012 | [0.056] | 1.012 | 0.103 | [0.026]*** | 1.108 | 0.107 | [0.023]*** | 1.113 |

| Constant | −3.912 | [1.194]** | 0.020 | −0.412 | [0.727] | 0.662 | −1.308 | [0.597]* | 0.270 |

|

| |||||||||

| Person-years | 30,432 | 46,920 | 77,352 | ||||||

| Couples | 5,220 | 6,581 | 11,801 | ||||||

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Model 2 includes race as a control variable. SE = Standard error.

Table 5.

Inequities and divorce risks in West Germany and in the United States

| West Germany | United States | Pooled | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | Robust SE | eβ | β | Robust SE | eβ | β | Robust SE | eβ | |

| Wife is under-benefitted | −0.497 | [0.576] | 0.608 | −0.424 | [0.414] | −0.386 | [0.414] | 0.680 | |

| Husband’s share of paid work | −1.025 | [0.295]*** | 0.359 | −3.513 | [0.872]*** | −3.556 | [0.856]*** | 0.029 | |

| Husband’s share of paid work sq. | 4.718 | [1.984]* | 2.694 | [0.640]*** | 14.791 | ||||

| W under × H share of paid | −0.192 | [1.253] | 0.825 | 2.753 | [0.663]*** | 4.938 | [1.951]* | 139.491 | |

| W under × H share of paid sq. | −4.208 | [3.178] | −4.318 | [3.106] | 0.013 | ||||

| West Germany (ref. US) | −1.046 | [0.509]* | 0.351 | ||||||

| WG × Wife is under-benefitted | 0.274 | [0.812] | 1.315 | ||||||

| WG × H’s share of paid work | 3.936 | [1.517]** | 51.213 | ||||||

| WG × W under × H share of paid | −3.817 | [1.071]*** | 0.022 | ||||||

| WG × W under × H share of paid sq. | −5.544 | [4.626] | 0.004 | ||||||

| WG × H’s share of paid work sq. | 2.890 | [7.396] | 17.993 | ||||||

| Wife is over-benefitted | 0.320 | [0.341] | 1.377 | −0.340 | [0.281] | 0.712 | −0.022 | [0.214] | 0.978 |

| Log of marriage duration | −0.045 | [0.076] | 0.956 | −0.157 | [0.043]*** | 0.855 | −0.152 | [0.037]*** | 0.859 |

| Couple’s total hours of paid work | 0.004 | [0.003] | 1.004 | 0.001 | [0.002] | 1.001 | 0.001 | [0.002] | 1.001 |

| Couple’s total hours of housework | −0.003 | [0.004] | 0.997 | −0.010 | [0.002]*** | 0.990 | −0.008 | [0.002]*** | 0.992 |

| First marriage | −0.582 | [0.312] | 0.559 | −0.509 | [0.091]*** | 0.601 | −0.384 | [0.084]*** | 0.681 |

| Wife’s age at marriage | −0.082 | [0.088] | 0.921 | −0.251 | [0.051]*** | 0.778 | −0.187 | [0.044]*** | 0.829 |

| Wife’s age at marriage sq. | 0.001 | [0.002] | 1.001 | 0.003 | [0.001]*** | 1.003 | 0.003 | [0.001]** | 1.003 |

| Marriage year (0 = 1967) | 0.101 | [0.034]** | 1.106 | 0.086 | [0.017]*** | 1.090 | 0.084 | [0.015]*** | 1.088 |

| Marriage year sq. | −0.002 | [0.001]* | 0.998 | −0.001 | [0.000]*** | 0.999 | −0.002 | [0.000]*** | 0.998 |

| Age difference (ref. Same age) | |||||||||

| Wife is older | 0.397 | [0.155]* | 1.487 | 0.206 | [0.080]** | 1.229 | 0.223 | [0.071]** | 1.250 |

| Wife is younger | 0.076 | [0.126] | 1.079 | 0.176 | [0.081]* | 1.192 | 0.113 | [0.068] | 1.120 |

| Person-years | 77,352 | 77,352 | 77,352 | ||||||

| Couples | 11,801 | 11,801 | 11,801 | ||||||

| Wife’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | |||||||||

| ISCED 3–4 | −0.119 | [0.135] | 0.888 | 0.729 | [0.236]** | 2.073 | 0.236 | [0.111]* | 1.266 |

| ISCED 5–6 | −0.083 | [0.184] | 0.920 | 0.469 | [0.251] | 1.598 | 0.009 | [0.131] | 1.009 |

| Husband’s education (ref. ISCED 1–2) | |||||||||

| ISCED 3–4 | −0.013 | [0.145] | 0.987 | 0.086 | [0.168] | 1.090 | 0.111 | [0.107] | 1.117 |

| ISCED 5–6 | −0.446 | [0.186]* | 0.640 | −0.477 | [0.188]* | 0.621 | −0.450 | [0.128]*** | 0.638 |

| Number of children in the household | 0.051 | [0.057] | 1.052 | 0.099 | [0.026]*** | 1.104 | 0.113 | [0.023]*** | 1.120 |

| Constant | −2.873 | [1.223]* | 0.057 | 0.209 | [0.770] | 1.232 | −0.366 | [0.648] | 0.694 |

|

| |||||||||

| Person-years | 77,352 | 77,352 | 77,352 | ||||||

| Couples | 11,801 | 11,801 | 11,801 | ||||||

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Model 2 includes race as a control variable. SE = Standard error.

Empirical Results

Inequity and Divorce

Models 1–3 in Table 3 summarize our main results for the first Hypothesis – whether the degree of inequity per se increases divorce risks. All the results are presented as log-odds with robust and clustered standard errors as well as the corresponding odds-ratio.

The impact of inequity on the risk of divorce differs in the two countries. In West Germany it is nil since the coefficient is insignificant and near zero. In the United States, the degree of inequity has a positive and statistically significant effect on marital dissolution (<0.001 in the model) - the higher the level of inequity the higher the risk of divorce. The country-differences are clear. This is additionally so in the pooled model (Model 3).

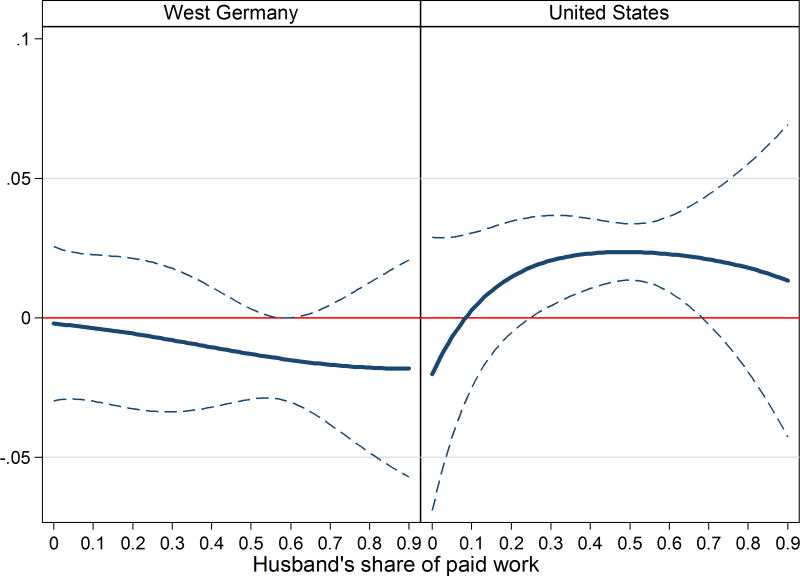

To facilitate interpretation, we present (in Figure 5) the average marginal effects of an increase in the degree of inequity for West German and US couples. These are computed from Model 3 in Table 3. Here we see that higher levels of inequity do not increase the risk of divorce in West Germany. In the United States, however, a one unit increase in inequity (a one unit deviation from the equity space) is associated with a 1.7 percentage-point increase in the probability of divorce. Since there is no overlap between the confidence intervals for Germany and the US, we conclude that the average marginal country effects are statistically different. This is also confirmed by the statistically significant interaction between West Germany and the equity variable in Model 3 in Table 3.

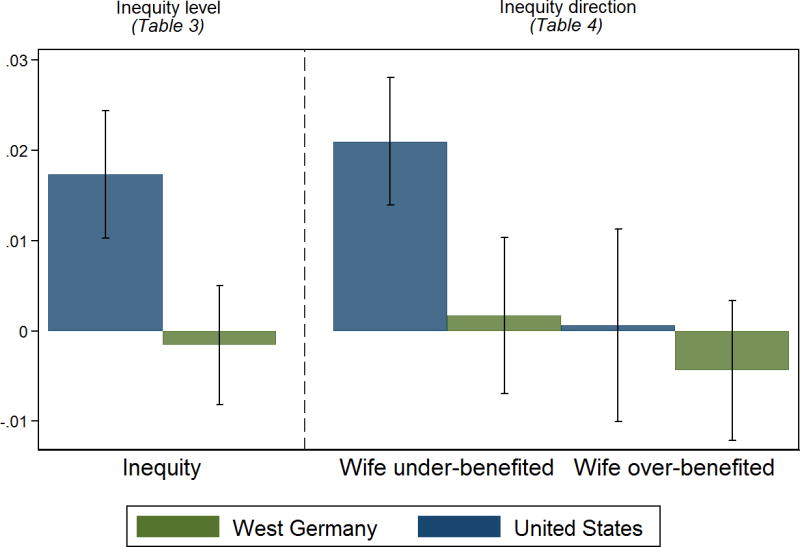

Figure 5. Average marginal effects on predicted divorce risk with 95% confidence intervals: Inequity level and inequity direction.

Note: The average marginal effects are based on the pooled models presented in Table 3 for inequity level and in Table 4 for the inequity direction.

All told, equity influences American but not German couple behaviour. In other words, Hypothesis 1 receives mixed support since the marital stability premium of equity is limited to the US. We now turn to an exploration of whether this country difference can be explained by heterogeneous effects of equity conditional on gender and couple arrangement.

Equity and Under- and Over -Benefited Wives

Does the association between objective equity and divorce vary by gender? To answer this question we include a “spline version” of the objective equity measure. This helps distinguish couples where the wife is under-benefited from those where she over-benefits15. The variable female under-benefiting takes the value of zero in case of equity and of female over-benefiting, and the variable female over-benefiting takes value zero in case of equity and of female under-benefiting, respectively. Our Hypothesis 2 predicted decreasing divorce risks among German wives the more they under-benefit; for the US, we predicted heightened divorce propensities. In both countries, however, we expect that an increase in the level of female over-benefiting is associated with an increase in the propensity of divorce.

The results are shown in Table 4. In Model 1, we present results for West Germany, and in Model 2 for the United States. Model 3 reports estimations from a pooled model of the two countries. For West Germany, we do not observe any statistically significant relationship between the level of female over- or under- benefiting and the risk of divorce. This finding is in line with the first model, where we observed that the degree of inequity was not associated with divorce in West German couples.

In the US, however, we find a positive and statistically significant association between the level of female under-benefiting and marital dissolution. When the wife dedicates an increasingly disproportionate time to unpaid work, U.S. couples experience greater marital instability. No significant association is observed between the degree of female over-benefiting and marital dissolution. For the US, it appears that the significant effect of inequity reported in Table 3 is primarily driven by female under-benefiting.

To facilitate comparison across the countries, we present (in Figure 5) the average marginal effects of an increase in wives’ being under- vs. over-benefited. For German couples we observe that the level of over- or under-benefiting has no statistically significant impact on the risk of divorce.

In the US, however, the likelihood of divorce increases significantly when the wife contributes disproportionally to housework, given her relative contribution to paid work. On average, a one unit increase in female under-benefiting is associated with a 2.1 percentage-point increase in divorce risk.

Hypothesis 2 is therefore only partly confirmed. Although the results are not fully in line with the expectations of the distributive justice framework (as in Thompson 1991), we do find that the country-differences in terms of the effects of under-benefiting on divorce are statistically significant (in Figure 5, the confidence intervals for the average marginal effects of under-benefiting do not overlap, suggesting that the averages are statistically different).

Contrary to expectations, the level of female over-benefiting is not positively associated with marital dissolution in either country. In Figure 5, we see that the German average marginal effects are negative but with large confidence intervals. In the United States, the size effect is positive and very small with very large confidence intervals as well. The average marginal effects for female over-benefiting is not different across the two countries.

Equity and Couple Arrangements

To test Hypothesis 3, we estimate the effects of female under-benefitting at different levels of specialization by adding an interaction term for female under-benefiting combined with the husbands’ relative contribution to paid work.

The aim is to test whether the degree of female under-benefiting has a different impact given the couple’s paid work arrangements. For both countries, we include the husband’s share of paid work first linearly and subsequently with a second-order polynomial16. Because the relationship is linear in West Germany and quadratic in the United States, we allow for a quadratic specification in the pooled model. In Table 5, we present three models for, respectively, West Germany, the United States, and a pooled model. In all models we present the log-odds and standard errors as well as the corresponding odds-ratio.

In West Germany, the larger the husband’s share of paid work, the lower the risk of divorce; here the male breadwinner arrangement represents the single most stable type of partnership. In contrast, the relationship between the husband’s share of paid work and divorce is non-linear in the US. The risk of divorce declines, reaching a minimum for dual-earner couples and it plateaus for traditional breadwinner couples. While this finding is not central to our study, it does give us a better understanding of the cross-country differences we have uncovered.

We now turn to the interaction between the degree of female under-benefiting and the husband’s share of paid work. For West Germany, the results in Model 1 suggest that the association between the level of female under-benefiting and divorce is not modified by the couple’s division of paid work. Overall, the interaction is negative and not statistically significant. In the United States, the interaction between the linear term for specialization and the wife under-benefiting is positive and statistically significant.

In logistic estimation it is difficult to interpret interactions between continuous variables. We therefore present the results with marginal effects estimation. Figure 6 presents the average marginal effects of an increase in female under-benefiting for values of his share of paid work ranging from 0 to 90%17. The average marginal effects of divorce are based on Model 3 in Table 5 for the United States.

Figure 6. Average marginal effects on predicted divorce risk with 95% confidence intervals: Inequity level and traditionalism.

Note: The average marginal effects are based on the pooled model presented in Table 5.

Figure 6 suggests that the average marginal effect of female under-benefiting at different values of the share of paid work do not follow the same pattern in the two countries. In West Germany, the association between the degree of female under-benefiting and marital instability is overall negative. The average marginal effects are only statistically significant when the husband contributes between 50% and 60% to paid work – i.e. when there is partner-similarity in paid work. In other words, when German wives do more than their fair share of housework, dual-earner couples experience diminished divorce risks. Nevertheless, considering the size of the confidence intervals, this result should be interpreted with some caution.

Here again, the US exhibits a very different logic. Reflecting the non-linear nature of the relationship between the division of paid work and divorce, the average marginal effects follow an inverse u-shaped relationship. In dual earner couples, a less equal division of paid and unpaid work, with the wife under-benefiting, increases the divorce risk. In Figure 6, we observe that the positive average marginal effect of an increase in female under-benefiting on divorce is statistically significant when her share of paid work falls between 30% and 65%.

These findings reveal noticeable differences in the relationship between paid and unpaid work in the two countries. In line with Hypothesis 3, we find that that the effect of female under-benefiting on divorce is distinctly different. In West Germany, adherence to traditional gender roles diminishes the risk of divorce within dual earner couples when partners contribute similarly to paid work. And in West Germany it is still the conventional male breadwinner model that best guarantees marital stability. Partnership dynamics are clearly different in the United States, where marital instability increases when (employed) wives do more than their fair share of the housework.

As a final step, we explore in more detail the association between female over-benefiting and the risk of divorce according to the male share of paid work (estimations not reported here).18 Not surprisingly, we observe that the coefficient related to the degree of female over-benefiting is positive and significant for US dual earner couples, but this is not the case for sole male or female breadwinner couples. For West Germany, we find no significant effects at all.

Conclusion and discussion

We have examined the link between equity and divorce, focusing on West German and US couples over the past three decades. Our approach differs from previous studies on several key points. Firstly, we focus on the impact on marital dissolution of the allocation of paid and unpaid work simultaneously, rather than the more common focus on marital satisfaction. Secondly, we test the impact of equity, comparing two countries which differ regarding proper gender norms.

We examined whether the degree of inequity in couples’ allocation of paid and unpaid work influences marital stability – as the equity-as-proportionality theory predicts. We found that this holds only for the US; for West Germany, the degree of inequity has no effect at all. This suggests, firstly, that the impact of objective inequity on divorce varies across cultural contexts; it may be determinant for marital dissolution in some countries (e.g. the US) but not in others (e.g. in West Germany). Secondly, this puts into question the universality of the proportionality principle as a guide to predicting couple dynamics.

We additionally sought to identify the impact of inequity depending on whether the wife is under- or over-benefited. The distributive justice approach (as in Thompson 1991) would predict greater marital stability the more that the female under-benefits – within a gender-traditional context. Indeed, this is precisely what we found for West German couples. But in the United States, the opposite occurs: the more that the wife under-benefits, the less stable is the partnership. Again, inequities do not have the same impact on marital stability in the two countries. Estimating female over-benefiting with a linear specification, we found no significant effect in either country.

Finally, we tested for the moderating influence of the couple’s paid work arrangements on divorce risks in couples where the female is under-benefiting. In this case our focus was on dual earner couples. For the US, there is clear evidence that the more that the female under-benefits in dual earner partnerships, the higher is the risk of divorce. Again, the exact opposite is the case in West Germany, especially for couples where partners divide similarly their paid work amount. Further analyses suggested that an increase of female over-benefiting in dual earner couples is associated with a greater probability of divorce in the United States – but not in Western Germany.

The key to an interpretation of these findings lies in how inequity combines with a type of partnership which conforms to, or deviates from, socially sanctioned arrangements. In a nutshell, the importance of adopting equitable marital practices is salient in the U.S. In West Germany, the conventional male breadwinner model is still the arrangement that ensures marital stability the most. When couples move from the male breadwinner model to dual partnership, female under-benefiting exerts a stabilizing influence, especially for partners that contribute similarly to paid work. Our findings for the United States are basically orthogonal to the German. Here marital stability is greater in couples where both partners are employed and where they divide fairly their domestic responsibilities.

It would appear that Germany is still positioned at the early stages of gender role change, a stage in which the adoption of equity remains negatively sanctioned. The US, in contrast, appears to have moved decisively towards a new normative equilibrium, one in which it is broadly accepted (and expected) that wives pursue a lifelong career, and that husbands should adapt to women’s new roles. This suggests that gender egalitarian norms have become pervasive throughout American society. An interesting next step would be to estimate these kinds of models on a country, like Denmark or Sweden, which has progressed even further towards gender egalitarianism.

On a final note, our study does have limitations. First of all, due to the lack of data on child-care, it was impossible to build a complete measure of equity. Since previous studies have shown a strong correlation between participation in domestic work and time spent on childcare (e.g. Cooke, 2006), this limitation may not have influenced our findings greatly.

Also, we could not consider other kinds of activities performed by the spouses (e.g. emotional work). This exclusion may have biased our estimates (see De Maris, 2010). And due to data limitations, we could not include cohabiting couples. The latter may behave in a more gender egalitarian way; and it is well-established that they are less stable than their married counterparts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Gøsta Esping Andersen’s European Research Council Advanced Grant FP7-IDEAS-ERC/269387 (‘Family Polarization’). Léa Pessin gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the Population Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University for Population Research Infrastructure (P2CHD04102) and Family Demography Training (T-32HD007514). The collection of the data for the United States (Panel Study of Income Dynamics) used in this study was partly supported by the National Institute of Health under the grant number R01HD069609 and the National Science Foundation under the award number 1157698. No direct support was received from grants NIH R01HD069609 and NSF 1157698 for this analysis.

Footnotes

Research suggests that also other inputs may be considered by partners when evaluating proportionality (e.g. Gergen, 1980).

The principle of proportionality justice is based on reciprocity, not mutual advantage, with a motive to return benefits because of benefits received.

The male partner is the comparison referent for wives.

In this sense, subjective equity corresponds to objective equity.

We follow the approach of Gager (1998, 2006) according to which the division of work cannot be understood without considering paid and unpaid labor jointly. Accordingly, objective equity corresponds to a fair allocation when it is evaluated rationally - contributions to unpaid work are proportional to contributions to paid work. Subjective equity represents the sense of fairness that individuals perceive according to normative rules about what is just. Subjective and objective equity may overlap.

Here, subjective equity does not overlap with objective equity.

Notwithstanding such limitations, they were used in many studies to analyze the division of work between partners and its impact on marital outcomes in the US (Brines, 1994; Gupta, 1999; Cooke, 2006). Cooke (2006, page 457, line number 25) argues that even if the time use data in the PSID are not as precise as are time diary data, results obtained using only domestic work hours “are remarkably consistent in terms of the extent of equity or compensatory behaviour made evident with them”.

We exclude the first two waves because of changes in the definition of key variables.

Also, East Germany represented a qualitatively different model of female participation and family life (Cooke, 2004).

In 2000 the GSOEP added a major new refresher sample that significantly increased the sample size (Wagner, 2009).

In the PSID, when we have both the marital separation and divorce dates, we use the earliest of the two.

Relative measures have conceptual and empirical advantages, especially because they are more likely to capture the distributive justice aspects of the division of work within a couple (Greenstein, 2000; Cooke, 2006).

In the Technical Appendix, we explain how we handle missing information in the off-years after 1997.

Kalmijn and Monden (2012) use a similar technique to study the effects of inequity on depressive symptoms.

Because these measures are relative within couples, we can also interpret the wife under-benefited as the husband being over-benefited and the wife over-benefited as the husband being under-benefited.

The inclusion of a second-order polynomial was motivated by the lack of association between the share of paid work and divorce risk in the linear model for the United States. Since this contradicts the existing literature, we included a quadratic term for the United States.

We do not extend to values higher than 0.9 because under-benefitting cannot occur beyond these values (see Figure 1 for a visual explanation).

We replicated the models for Hypothesis 3 using a categorical variable instead of the husband’s share of paid work. The categorical variable takes values of 1 when husband’s relative contribution is higher than .1 deviation of the wife’s, taking the value of zero otherwise.

References

- Adams JS. Towards an understanding of inequity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1963;67:422–436. doi: 10.1037/h0040968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JS. Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1965;2:267–299. doi: 10.12691/ajap-1-1-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:61–98. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Tension between institutional and individual views of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:959–965. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Johnson DR, Booth A, Rogers SJ. Continuity and change in marital quality between 1980 and 2000. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00001.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J, Zelditch M, Anderson B, Cohen BP. Structural aspects of distributive justice: A status value formulation. Sociological Theories in Progress. 1972;2:119–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bird CE. Gender, household labor, and psychological distress: the impact of the amount and division of housework. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour. 1999;40:32–45. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2676377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittman M, England P, Sayer L, Folbre N, Matheson G. When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;109:186–214. doi: 10.1086/378341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Lewin-Epstein N, Stier H, Baumgärtner MK. Perceived equity in the gendered division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1145–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R, Cooke LP. The persistence of the gendered division of domestic labour. European Sociological Review. 2005;21:43–57. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brines J. Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home. American Journal of Sociology. 1994;100:652–688. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Toward a new home socioeconomics of union formation. In: Waite LJ, editor. The ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000. pp. 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:848–861. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KS, Hegtvedt KA. Distributive justice, equity, and equality. Annual review of sociology. 1983;9(1):217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke LP. The gender division of labor and family outcomes in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:1246–59. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00090.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke LP. Doing gender in context: household bargaining and risk of divorce in Germany and the United States. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;112:442–472. doi: 10.1086/506417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke LP, Erola J, Evertsson M, Gähler M, Härkönen J, Hewitt B, Trappe H. Labor and love: Wives’ employment and divorce risk in its socio-political context. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society. 2013;20:482–509. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxt016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter D, Hermsen JM, Vanneman R. The end of the gender revolution? Gender role attitudes from 1977 to 2008. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;117:259–89. doi: 10.1086/658853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong JDJ. Levi-Strauss’s theory on kinship and marriage. 10th. Leideen: Brill; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A, Longmore MA. Ideology, power, and equity: Testing competing explanations for the perception of fairness in household labor. Social Forces. 1996;74:1043–1071. doi: 10.1093/sf/74.3.1043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A. The role of relationship inequity in marital disruption. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:177–195. doi: 10.1177/0265407507075409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A. The 20-year trajectory of marital quality in enduring marriages: does equity matter? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:449–471. doi: 10.1177/0265407510363428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dush KCM, Taylor MG. Trajectories of marital conflict across the life course: predictors and interactions with marital happiness trajectories. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:341–368. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11409684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G, Boertien D, Bonke J, Gracia P. Couple specialization in multiple equilibria. European Sociological Review. 2013;29:1280–95. doi: 10.1093/esr/jct004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuwa M. Macro-level gender inequality and the division of household labor in 22 countries. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:751–767. doi: 10.1177/000312240406900601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT. The role of valued outcomes, justifications, and comparison referents in perceptions of fairness among dual-earner couples. Journal of Family Issues. 1998;19:622–648. doi: 10.1177/019251398019005007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT, Hohmann-Marriott B. Distributive justice in the household: A comparison of alternative theoretical models. Marriage and Family Review. 2006;40:5–42. doi: 10.1300/J002v40n02_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT. What’s fair is fair? Role of justice in family labor allocation decisions. Marriage & Family Review. 2008;44:511–545. doi: 10.1080/01494920802454116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geist C. The welfare state and the home: Regime differences in the domestic division of labour. European Sociological Review. 2005;21:23–41. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen KJ. Social exchange. Springer US; 1980. Exchange Theory; pp. 261–280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- German Socio-Economic Panel. data for years 1984–2009. SOEP; 2009. (version 26). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, Fujimoto T. Housework, paid work, and depression among husbands and wives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994:179–191. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2137364. [PubMed]

- Greenstein TN. Husbands’ participation in domestic labor: Interactive effects of wives’ and husbands’ gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:585–595. doi: 10.2307/353719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein TN. Economic dependence, gender, and the division of labor in the home: A replication and extension. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:322–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00322.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. The effects of transitions in marital status on men’s performance of housework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:700–711. doi: 10.2307/353571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Traupmann J, Sprecher S, Utne M, Hay J. Compatible and incompatible relationships. New York: Springer; 1985. Equity and intimate relations: Recent research; pp. 91–117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Rapson RL, Aumer-Ryan K. Social justice in love relationships: Recent developments. Social Justice Research. 2008;21:413–431. doi: 10.1007/s11211-008-0080-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hegtvedt KA, Markovsky BN. Justice and injustice. In: Cook K, Fine G, House JS, editors. Sociological perspectives in social psychology. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1995. pp. 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Heimer CA, Staffen LR. For the sake of the children: The social organization of responsibility in the hospital and the home. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins C, Duxbury L, Lee C. Impact of life-cycle stage and gender on the ability to balance work and family responsibilities. Family Relations. 1994;2:144–150. doi: 10.2307/585316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR, Machung A. The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Homans A. Social behavior: Its elementary forms. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Homans GC. Fundamental processes of social exchange. In: Hollander EP, Hunt RJ, editors. Current perspectives in social psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1976. pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hood JC. Becoming a two-job family. New York: Praeger Publishers; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hook JL. Care in context: Men’s unpaid work in 20 countries 1965–2003. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:639–660. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30039013. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JA, Gerson K. The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, Monden CWS. The division of labor and depressive symptoms at the couple level: Effects of equity or specialization? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2012;29:358–374. doi: 10.1177/0265407511431182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kluwer E, Mikula G. Gender-related inequalities in the division of family work in close relationships: A social psychological perspective. European Review of Social Psychology. 2003;13:185–216. doi: 10.20180/10463280240000064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen K, Wærness K. National context and spouses’ housework in 34 countries. European Sociological Review. 2008;24:97–113. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcm037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyngstad TH, Jalovaara M. A review of the antecedents of union dissolution. Demographic Research. 2010;23:257–292. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikula G. Division of household labor and perceived justice: A growing field of research. Social Justice Research. 1998;11(3):215–241. doi: 10.1023/A:1023282615718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molm LD, Cook KS. Social exchange and exchange networks. In: Cook KS, Fine GA, House JS, editors. Sociological Perspectives on Social Psychology. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1995. pp. 209–235. [Google Scholar]

- Nock SL. The marriages of equally dependent spouses. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22:755–775. doi: 10.1177/019251301022006005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oláh LS, Gähler M. Gender equality perceptions, division of paid and unpaid work, and partnership dissolution in Sweden. Social Forces. 2014;93:571–594. doi: 10.1093/sf/sou066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics public use dataset. Produced and distributed by the Survey Research Center. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppanner L. Fairness and housework: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2008:509–526. Retrieved from jstor.org/stable/41604243.

- Ruppanner L. Conflict and housework: Does country context matter? European Sociological Review. 2010;26:557–570. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcp038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppanner L. Housework conflict and divorce: a multi-level analysis. Work, Employment & Society. 2012;26:638–656. doi: 10.1177/0950017012445106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson EE. On justice as equality. Journal of social Issues. 1975;31(3):45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CR, Han H. The reversal of the gender gap in education and trends in marital dissolution. American Sociological Review. 2014;79:605–629. doi: 10.1177/0003122414539682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. The relation between inequity and emotions in close relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1986:309–321. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2786770.

- Stafford L, Canary DJ. Equity and interdependence as predictors of relational maintenance strategies. The Journal of Family Communication. 2006;6:227–254. doi: 10.1207/s15327698jfc0604_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ. Marital quality and satisfaction with the division of household labor across the family life cycle. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;1:221–230. doi: 10.2307/353146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. Family work: Women’s sense of fairness. Journal of Family Issues. 1991;12:181–196. doi:0.1177/019251391012002003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Lippe T. Dutch workers and time pressure: Household and workplace characteristics. Work, Employment & Society. 2007;21:693–711. doi: 10.1177/0950017007082877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Yperen NW, Buunk BP. A longitudinal study of equity and satisfaction in intimate relationships. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;20(4):287–309. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420200403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Willigen M, Drentea P. Benefits of equitable relationships: The impact of sense of fairness, household division of labor, and decision making power on perceived social support. Sex Roles. 2001;44:571–597. doi: 10.1023/A:1012243125641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GG. The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) in the Nineties: an example of incremental innovations in an ongoing longitudinal study. SOEP papers. 2009:257. [Google Scholar]

- Walster E, Berscheid E, Walster GW. New directions in equity research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;25:151. doi:org/10.1037/h0033967. [Google Scholar]

- Walster EG, Walster W, Berscheid E. Equity: Theory and research. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB, Nock SL. What’s love got to do with it? Equality, equity, commitment and women’s marital quality. Social Forces. 2006;84:1321–1345. doi: 10.1353/sof.2006.0076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yodanis C. The institution of marriage. In: Treasand J, Drobnic S, editors. Dividing the domestic: Men, women and housework in cross-national perspective. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.