Abstract

We synthesized and evaluated new zwitterionic inhibitors against glycoside hydrolase-like phosphorylase Streptomyces coeticotor (Sco) GlgEI-V279S which plays a role in α-glucan biosynthesis. Sco GlgEI-V279S serves as a model enzyme for validated anti-tuberculosis (TB) target Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) GlgE. Pyrrolidine inhibitors 5 and 6 were designed based on transition state considerations and incorporate a phosphonate on the pyrrolidine moiety to expand the interaction network between the inhibitor and the enzyme active site. Compounds 5 and 6 inhibited Sco GlgEI-V279S with Ki = 45 ± 4 μM and 95 ± 16 μM, respectively, and crystal structures of Sco GlgE-V279S-5 and Sco GlgE-V279S-6 were obtained at a 3.2 Å and 2.5 Å resolution, respectively.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). TB kills more people every year than any other infectious disease. The World Health Organization reported that in 2015 about 10.4 million individuals fell ill and 1.4 million deaths resulted from TB.1 In order to eradicate TB there is a need to identify new compounds and drug targets which act faster and show activity in drug resistant Mtb strains.2,3

Kalscheuer et al. have reported a four-step pathway in Mtb that involves conversion of trehalose to α-1,6-branched-α-1,4-glucan.4–7 The third step is catalyzed by GigE which is an α-maltose 1-phosphate (M1P):(1 → 4)-α-d-glucan 4-α-d-maltosyltransferase (EC2.4.99.16)4,5 and is a member of the CAZy glycoside hydrolase (GH)-like phosphorylase GH13_3 family.8 Deletion of GlgE leads to rapid buildup of toxic levels of M1P which elicits pleiotropic stress in the cell leading to cell death in a matter of two weeks.4 This data combined with the fact that there is no equivalent enzyme in the human proteome suggests GlgE may be an advantageous anti-TB drug target.9 Streptomyces coelicolor GlgE isoform I (Sco GlgEI) is a close structural homologue of Mtb GlgE possessing 53% sequence identity with the Mtb H37Rv GlgE.10–12 Through creation of the Sco GlgEI-V279S variant, there is 100% identity in the active site residues of these two homologues, and crystals of the Sco GlgEI-V279S variant diffract to higher resolution in comparison to Mtb GlgE.11,12 Therefore, we have used Sco GlgEI-V279S to evaluate substrate analogues13,14 and transition state-like inhibitors.15

Sco GlgEI is a phosphorylase that catalyzes a reversible glycosyl transfer from a saccharide donor substrate to phosphate.16,17 The mechanism is a double displacement mechanism consisting of two inverting steps with an intermediate β-glycosyl enzyme intermediate.10,18 During the first glycosylation step, the acid/base E423 side chain protonates the glycosidic oxygen. Protonation facilitates phosphate leaving group departure and, at the same time, the nucleophile D394 attacks at the anomeric carbon leading to the formation of a covalent β-glycosyl-enzyme intermediate.11 In the second step, the acid/base residue deprotonates a nucleophile to attack at the anomeric carbon with positive charge build up on the anomeric carbon and endocyclic oxygen. The D394 nucleophile has been unambiguously assigned by trapping studies.10 The release of phosphate in the mechanism is facilitated by E423, which acts as an acid/base residue and subsequently deprotonates the incoming acceptor α-1,4-glucan.10

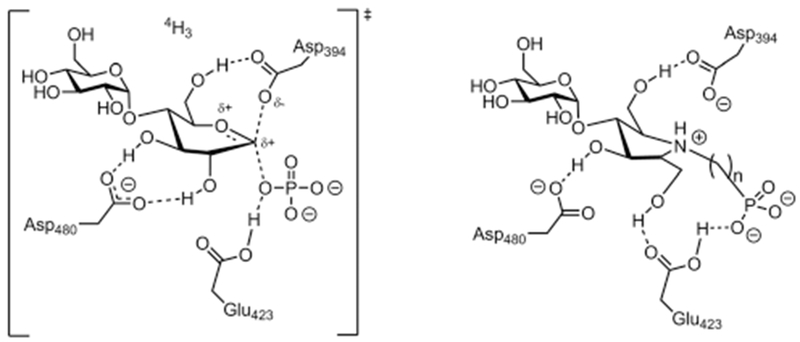

In the first step of the reaction, the transition-state involves protonation and charge accumulation on the anomeric exocyclic oxygen. At the same time, the nucleophile attacks the anomeric carbon causing the atom to undergo different levels of sp2 and sp3 characteristics, and also induce double bond characteristics between the anomeric carbon and endocyclic oxygen. These geometric requirements distort the pyranose ring from a ground state chair conformation to a strained 4H3 half chair conformation.10,19 The GH13 family also has a second conserved aspartate residue (D480 for GlgEI). This residue is postulated to form hydrogen bonds with the C-2 and C-3 hydroxyl groups in the transition state.20–22 The proposed interactions, charges and conformations for the first transition state are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed transition-state for the first step in the mechanism of GH-like phosphorylase Sco GlgEI (left). Designed zwitterionic pyrrolidine-phosphonates based on transition state considerations (right). n = 1 or 2.

Design of the inhibitors: introduction of a departing negative charge near the anomeric center

It has been postulated that GHs bind transition states with extraordinary affinity23,24 and there is now an extensive body of literature on inhibitors that are suggested to mimic GH transition states.25–28 In these studies, we prepared iminosugars that are protonated at physiological pH and mimic the positive charge that develops on the anomeric carbon and endocyclic oxygen expected for a late transition state. This is in contrast to early transition state GH inhibitors which mimic the initial protonation of the leaving group oxygen.29 The 6-membered polyhydroxylated piperidine iminosugars, represented by nojirimycin 130 and 1-deoxynojirimycin 231 are classical GH inhibitors.32–34 These compounds mimic the ring size of the substrate and the charge that develops in a late transition state that is stabilized by the nucleophile in the active site. Polyhydroxylated pyrrolidines also show potent GH inhibitory activity. Fleet et al. prepared 1,4-dideoxy-l,4-imino-d-mannitol (DIM) 3 in 1984, which is the first example of this type of inhibitor.35 This initial work has been followed by many related examples.36–41 The pyrrolidines mimic both the shape and charge of the half-chair transition state (Fig. 1). Previously, we designed 2,5-dideoxy-3-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl-2,5-imino-d-mannitol (4) as a transition state mimic of Sco GlgEI-V279S based on this knowledge.15 The pyrrolidine 4 had moderate inhibitory activity, which afforded the X-ray crystallographic studies with 4 bound in the catalytic site of Sco GlgEI-V279S and showing the nitrogen atom within hydrogen bonding distance of the D394 carboxylate.12 In the current studies, we explore introduction of a phosphonate on the nitrogen of compounds (5–6) to mimic the ring charge, ring geometry, departing phosphate charge and enzyme stabilizing contacts that can develop in the transition state. The spacing between the nitrogen and phosphate was varied to explore optimal charge separation. The work is also relevant to N-phosphonate analogues which have shown activity against bacterial transglycosylases.42 In addition, we compare our results to the X-ray structure of Sco GlgEI-V279S bound to MCP (Fig. 2) which was designed as a non-hydrolyzable mimic of M1P.12,13

Fig. 2.

Natural and designed inhibitors for glycoside hydrolases (1–3) and designed inhibitors of Sco GlgEI-V279S (MCP, 4–6).

Synthesis of the polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine-phosphonates

The plan for the synthesis of pyrrolidine-based phosphonates 5 and 6 was to start with previously prepared polyhydroxlyated pyrrolidine (4), shown in Fig. 2. We envisioned subjecting pyrrolidine 415 to a Kabachnik–Fields reaction43 to access the one carbon phosphonate. We also considered the use of an aza-Micheal reaction44 with compound 10 or possibly a reductive amination42 with compound 15 to access the two carbon homologues (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of zwitterionic pyrrolidine-phosphonates. Reagents and conditions: (a) TMSBr, CH2Cl2; (b) oxalyl chloride, cat. DMF, 6 h, DCM; (c) pyridine, BnOH, THF (over all 53%); (d) ozonolysis, DCM; (e) HP(O)(OBn)2, CH2O, 60 °C (56%); (f) 10% Pd(OH)2 on carbon, MeOH, quantitative; (g) Et3N, H2O; (h) MeOH, NaCNBH3 (56%).

To prepare the required phosphonate building blocks, available diethyl vinylphosphonate (7) and available phosphonate 11 were deprotected with TMSBr to afford the phosphonic acid 8 and the phosphonic acid 12, respectively (Scheme 1). Both 8 and 12 were converted to the chloride derivative and subjected to benzylation with benzyl alcohol to afford dibenzyl vinylphosphonate (10) and dibenzyl allylphosphonate (14),45 respectively. The functional group manipulation provided benzyl protected phosphonates for a planned single step global deprotection. Ozonolysis of alkene 14 provided aldehyde 15, which could be used directly without any further purification.

Thus, compound 4 was subjected to Kabachnik–Fields reaction43 by aqueous formaldehyde treatment followed by addition of dibenzyl phosphite at reflux to yield 16 as shown in Scheme 1.42 Compound 16 was globally debenzylated by treating with 10% Pd(OH)2/C–H2 in methanol to afford the target molecule 5. Odinets et al. have reported the synthesis of β-aminophosphonates by an aza-Micheal reaction.44 While our attempts to synthesize 6 using this approach in combination with vinylphosphonate 10 were unsuccessful, subjecting molecule 4 to NaCNBH3 in the presence of aldehyde 15 yielded alkylated amine 17 in 56% yield,42 which was cleanly debenzylated using 10% Pd(OH)2/C–H2 in methanol.

Discussion of the inhibitory activity

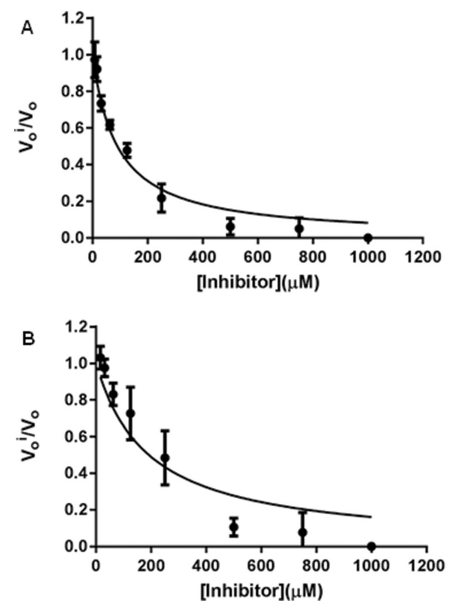

Inhibition studies on Sco GlgEI-V279S were performed by coupling GlgEI phosphorylase activity on M1P to a purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) activity as previously described.13,46 Using this assay (Fig. 3), we determined the Ki for compound 5 and 6 against Sco GlgEI-V279S to be Ki = 45 ± 4 μM and Ki = 95 ± 16 μM, respectively. Thus, the one carbon phosphonate 5 was 2-fold more potent than the two carbon phosphonate 6. The one carbon phosphonate 5 was also 2-fold more potent than our previously reported transition state-like inhibitor 4 Ki = 102 ± 7 μM.15 In spite of this improvement, we conclude both of the new targets are suboptimal transition state mimics based on μM affinity.

Fig. 3.

A. Ki determination of 5 with Sco GlgEI-V279S. B. Ki determination of 6 with Sco GlgEI-V279S. are steady-state rates with and without inhibitor. Error bars are calculated from the result of reactions performed in triplicate.

X-ray structural studies

Compounds 5 and 6 were co-crystallized with Sco GlgEI-V279S and X-ray diffraction studies produced structures to 3.2 Å and 2.5 Å resolution, respectively (ESI, Table S1†). Despite being resolved at a 3.2 Å resolution, the Fo–Fc omit map of inhibitor 5 indicated the presence of the compound in the active site (Fig. 4A). The Fo–Fc omit map of inhibitor 6, however, lacks strong density for the ethyl linker resulting in poor resolution of the phosphonate moiety (Fig. 4B). The high B factors of the ethyl phosphonate moiety reflects this and, taken together, suggest only weak interactions between the ethyl phosphonate moiety and the enzyme active site. An ordered water molecule, however, is observed in both structures at the same position, leading to the entrance of the active site and 3.3 Å and 4.0 Å away from the phosphonate moiety of the inhibitors in Sco GlgEI-V279S-5 and Sco GlgEI-V279S-6 complexes, respectively.

Fig. 4.

(A) Sco GlgEI-V279S in complex with 5. Fo–Fc omit map calculated while omitting 5 is contoured at 3σ with 5 bound in the enzyme active site. (B) Sco GlgEI-V279S in complex with 6. Fo–Fc omit map calculated while omitting 6 is contoured at 3σ with 6 bound in the enzyme active site. The red spheres represent water molecules.

Looking at the interactions between the enzyme and the compounds, all the interactions previously seen in the −2 subsite are conserved in both structures.12 Despite a slight shift of inhibitor 5, all five hydrogen bonded interactions previously reported in the −1 subsite between maltose-C-phosphate and the enzyme are retained.12 The shift resulted, however, in a weakened ionic interaction between the nitrogen of the pyrrolidine ring and the nucleophile D394 (Fig. 5A and B). Comparatively, the complex Sco GlgEI-V279S-6 features a shift in the 5-hydroxymethyl of the pyrrolidine ring toward the D480 resulting in a strong bidentate interaction between the side chain of D480 and the pyrrolidine ring (Fig. 5C and D), an interaction that has been reported to be characteristic of GH13 family proteins.20–22 The shift also allowed for the ionic interaction between the nitrogen of the pyrrolidine ring and the nucleophile D394 to be retained. Additionally, the ethyl linker displaced the phosphonate moiety resulting in a loss of interactions between it and the side chains of N395 and E423 allowing for the formation of a new ionic interaction between the carbonyl of N395 and the nitrogen of the pyrrolidine ring. E423 further stabilizes this new interaction by formation a hydrogen bonded network between its side chain and N395 side chain and backbone nitrogen. The loss of these two hydrogen bonded interactions with the phosphonate confirms its destabilization, further highlighted by the lack of density of the side chains of E423, Y357 and K355 with distances of 2.9 Å and 3.7 Å between the phosphonate and Y357 and K355, respectively, versus 2.6 Å and 3.4 Å in the Sco GlgEI-V279S-5 complex.

Fig. 5.

(A) Interactions between Sco GlgEI-V279S and the pyrrolidine ring of 5. (B) Interactions between Sco GlgEI-V279S and the phosphonate moiety of 5. (C) Interactions between Sco GlgEI-V279S and the pyrrolidine ring of 6. (D) Interactions between Sco GlgE-V279S and the phosphonate moiety of 6. Both red spheres in panel B and D represent water molecules.

When comparing Sco GlgEI-V279S-4 and Sco GlgEI-V279S-5 (Fig. 6A) and Sco GlgEI-V279S-6 and Sco GlgEI-V279S-MCP (Fig. 6B), a shift of the side chains of N352, Y357 and K355 can be observed. Similarly, N352 displayed complete lack of density at 1σ in Sco GlgEI-V279S-5 allowing us to believe that N352 assumes the withdrawn position it takes in both Sco GlgEI-V279S-6 and Sco GlgEI-E423A-maltoheptaose (PDB: 5CVS) to accommodate without interacting with either phosphonate or acceptor molecule.49 Additionally, the presence of maltoheptaose unraveled the need of the glucose in the −1 and −2 subsite to be shifted up toward the entrance of the active site, which resulted in Y357, N395 and K355 also shifting (Fig. 6C and D). This way, Y357 is displaced by 1 Å to interact with both the endocyclic and hydroxymethyl oxygens of the glucose molecule bound in the +1 subsite instead of the phosphonate in Sco GlgEI-V279S-5 and Sco GlgEI-V279S-6 or the bridging oxygen between the −1 and +1 subsite. Finally, the side chain of N395, while interacting with the phosphonate moiety of 5 and the nitrogen of the pyrrolidine ring of 6, is rotated 180° as to allow its carbonyl group to interact with the O3’ of the glucose located in the +1 subsite and its amine with the endocyclic oxygen of the glucose in the −1 subsite. Also of interest, the water molecule consistently observed guarding the entrance of the active site is positioned at the same place as the methylhydroxyl of the glucose positioned in the +2 subsite. It has been shown that, when designing an oxocarbenium intermediate inhibitor, extending it further out of the active site to block the entrance, results in more potent inhibitors.47

Fig. 6.

(A) Superimposed active site of Sco GlgEI-V279S in complex with 4 (PDB: 4U2Y) and 5. (B) Superimposed active site of Sco GlgEI-V279S in complex with MCP (PDB: 4U31) and 6. (C) Superimposed active site of Sco GlgEI-V279S-5 and Sco GlgEI-E423A-maltoheptaose (PDB: 5CVS). (B) Superimposed active site of Sco GlgEI-V279S-6 and Sco GlgEI-E423A-maltoheptaose (PDB: 5CVS). The red spheres in panel (C) and (D) are water molecules.

Discussion

We previously synthesized a pyrrolidine-based inhibitor 4 that mimics the oxocarbenium transition state and the half-chair conformation with its 5-membered ring and positively charged nitrogen. Compound 4 had a Ki = 102 ± 7 μM.15 To improve the affinity of our inhibitor the active site, a phosphonate moiety was added to emulate the first transition state of the SN2 mechanism previously proposed by the literature or an early dissociative SN-like transition state. The transition state was mimicked using a methyl linker between 4 and the amended phosphonate moiety. The Ki dropped to 45 ± 4 μM, which is a 2-fold improvement over 4. Despite the modest resolution, 3.2 Å, of the determined X-ray crystal structure, inhibitor 5 was clearly resolved in the active site (Fig. 4A) and all hydrogen bonded interactions previously observed in both the −2 and −1 subsite of Sco GlgEI-V279S-4 were conserved with a weakened ionic interaction between E394 and the pyrrolidine ring. (Fig. 5A and B). The additional interactions between the enzyme and phosphonate of 5 are thought to be responsible for the improvement in the Ki. It is noteworthy to mention that out of all 5 hydrogen bonded interactions observed, three side chains, K355, N352 and Y357 exhibit poor density at 1σ, which suggests that despite the presence of the phosphonate moiety, the entrance in the active site remains dynamic, likely to accommodate the incoming α-glucan acceptor molecule.

Sco GlgE-V279S-6 complex showed a complete lack of density for the ethyl linker between the phosphonate and pyrolidine ring (Fig. 4B), suggesting a high dynamicity of it, resulting in poor density of the phosphonate. When looking at the interactions between 6 and the active site, all interactions between 4 and the active site were conserved, including the strong ionic interaction between D394 and the pyrrolidine ring (Fig. 5C). However, only two weak interactions were observed between the phosphonate and the side chains of K355 and Y357, which exhibit no density at 1σ. The high dynamicity and little interactions between the enzyme and the phosphonate are likely the reason for the higher Ki of 95 ± 16 μM, showing little to no improvement compared to the Ki of our previous inhibitor, 4. These results may suggest that the enzyme is not stabilizing the phosphate as it dissociates and leaves the active site. Since the side chains of K355 and Y357 showed high dynamicity in these structures, these residues are suggested to guide the acceptor molecule into the active site allowing for E423 to act as nucleophile. The presence of a water molecule positioned consistently at the entrance of the active site and where the hydroxymethyl of the glucose positioned in the +2 subsite of Sco GlgE-E423A-maltoheptaose strengthens this hypothesis (Fig. 6C and D). The side chain of K355 consistently showing no density in all the previously mentioned complexes, we postulate that it is guiding substrate, acceptor molecule and product in and out of the active site, alternatively opening and capping the active site. Using these new data, the next generation of our inhibitors could exploit newly observed hydrogen bonding interactions in the complexes made with 5, 6 and the maltoheptaose aiming for tighter binding, especially since, expanding out of the active site has been shown to improve affinity and selectivity.47 Exploiting the interactions between the consistently observed water molecule as well as the maltoheptaose and the enzyme could be used to improve upon our inhibitors. Another option would be to investigate the array of sp2 and sp3 hybridization alterations that the anomeric carbon undergoes during the reaction29 as well as the protonation of the exocyclic oxygen during the first step of the reaction by using a six-membered ring possessing a substituted nitrogen in place of the exocyclic oxygen.

Conclusions

Our initial inhibitor, compound 4, inhibited the enzyme with a Ki of 102 ± 7 μM. Based on our previously reported crystal structure, the synthesized zwitterionic pyrrolidine-phosphonates inhibitors were designed to better fill the available space between the nitrogen atom of the inhibitor and E423. Firstly, the tertiary ammonium moiety was anticipated to be protonated at physiologic pH, hence mimicking the partial positive charge that can develop at the anomeric carbon in either of the two transition states. Secondly, the phosphonate moiety provided additional enzyme interactions that could be present in the first transition state, without allowing for nucleophilic attack due to lack of an acceptable leaving group. The coupled effect of stabilized charge, by D394, at the anomeric site and the additional hydrogenbonded interactions with the phosphonate moiety made target molecule 5 a 2-fold better inhibitor when compared to previously reported inhibitors. The data from these ongoing studies provides valuable insight into the development of even more potent phosphorylase inhibitors.

Experimental section

General methods

All fine chemicals such as 10% palladium on activated carbon, diethyl allyl phosphonate, diethyl vinyl phosphonate, bromo trimethylsilane, benzyl alocohol, pyridine, 37% formaldehyde in water, dibenzyl phosphite, benzoyl cyanide, N-iodosuccinamide, silver trifluoromethane sulfonate and anhydrous solvents such as anhydrous methanol and N,N-dimethylformamide were purchased and used without purification. TLCs (silica gel 60, f254) were visualized under UV light or by charring (5% H2SO4–MeOH). Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel (230–400 mesh) using solvents as received. 1H NMR were recorded either on 600 MHz spectrometer in CDCl3 using residual CHCl3 as internal references, respectively. 13C NMR were recorded on the 150 MHz in CDCl3 using the triplet centered at δ 77.27 as internal reference. GCOSY method was used to confirm the NMR peak assignment. High resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed on a micro mass Q-TOF2 instrument. EnzChek® Phosphate Assay Kit was purchased for use in the Sco GlgEI-V279S inhibition assay.

Dibenzyl vinylphosphonate (10).48

To a stirred solution of 7 (1.60 g, 9.74 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 mL) was added bromotrimethyl silane (5.3 mL, 40 mmol) at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 9 h at the same temperature and then concentrated to give a residue. To an ice-cooled, stirred solution of this residue in dichloromethane (20 mL) was slowly added oxalyl chloride (3.0 mL, 35 mmol) and DMF (a few drops). After being stirred for 6 h at room temperature, the mixture was concentrated to give a residue. To a stirred solution of this residue in tetrahydrofuran (30 mL) was added benzyl alcohol (2.3 mL, 22 mmol) and pyridine (1.8 mL, 22 mmol) at −21 °C. After the mixture was stirred for 30 min at the same temperature, stirring was continued for 6 h at room temperature. The mixture was poured into saturated aqueous potassium bisulfate and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined extracts were washed with brine and dried over magnesium sulfate. Removal of the solvent gave a residue, which was purified by flash column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate = 10 : 1–1 : 1) to give 10 as pale yellow oil; yield: 53% (1.5 g); silica gel TLC Rf = 0.3 (1: 1 ethyl acetate–hexanes); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 4.95 (m, 4H, –CH2Ph), 5.97–6.25 (m, 3H, Alkene H′s), 7.23–7.26 (m, 10H, Aromatic H′s); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 67.4, 67.4, 124.9, 126.1, 127.9, 128.4, 128.6, 136.0, 136.1, 136.2 ppm; 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ 19.3 ppm. Mass spectrum (ESI-MS), m/z = 311.2 (M + Na)+, C16H17NaO3P requires 311.27. Data matches reference.

Dibenzyl allylphosphonate (14).45

To a stirred solution of 11 (1.60 g, 10 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 mL) was added bromotrimethylsilane (5.3 mL, 40 mmol) at room temperature. The solution was stirred for 9 h and concentrated to afford a residue. The residue was taken up in dichloromethane (20 mL) and cooled on ice. To the cold solution oxalyl chloride (3.0 mL, 35 mmol) and DMF (a few drops) was slowly added. The solution was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 6 h. The solution was concentrated to dryness and taken up in tetrahydrofuran (30 mL), cooled at −21 °C, and benzyl alcohol (2.3 mL, 22 mmol) and pyridine (1.8 mL, 22 mmol) were added. The solution was maintained at this temperature for 30 min, allowed to warm to room temperature, and stirred an additional 6 h. The mixture was poured into saturated aqueous potassium bisulfate and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined extracts were washed with brine and dried over magnesium sulfate. Removal of the solvent afforded a residue, which was purified by flash column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate = 10 : 1–1 : 1) to give 14; yield: 50% (1.52 g); silica gel TLC Rf = 0.45 (1 : 1 ethyl acetate–hexanes); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 2.55 (dd, J = 7.3, 22.0 Hz, 2H, –CH2), 4.90–5.11 (m, 6H, ═CH2, –CH2Ph), 5.70 (m, 1H, ═CH), 7.22–7.27 (m, 10H, Aromatic H′s); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 31.6, 32.5, 67.4, 67.4, 77.0, 77.2, 77.4, 120.2, 120.4, 127.0, 127.9, 128.5, 136.3 ppm; 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ 29.2 ppm. Mass spectrum (ESI-MS), m/z = 325.20 (M + Na)+, C17H19NaO3P requires 325.30. Data matches reference.

Dibenzyl ((3-hydroxy-2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)-(3-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)phosphonate (16).

2,5-Dideoxy-3-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl-2,5-imino-d-mannitol 4 (45 mg, 0.138 mmol) was added to aqueous formaldehyde (2 mL, 37% CH2O in water) and dibenzylphosphite (30 μL, 0.138 mmol). The solution was heated to 60 °C for 3 h and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in a minimal amount of water and loaded on a C18 column. The column was eluted with a solution of H2O–MeOH (1 : 1). The purified product was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain 16 as a viscous oil; yield: 56% (46 mg); = −14.0° (c = 1, H2O); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 3.23–3.34 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 3.35–3.78 (m, 11H, H-a, H-b, H-c, H-d, H-2′, H-3′, H-4′, H-5′, H-6,6′, H-4), 3.83 (dd, 1H, J = 3.6, 19.8 Hz, H-e, H-f), 3.57 (t, 1H, J = 9.6 Hz, H-6a’), 3.67 (m, 1H, H-4′), 3.86 (dd, 2H, J = 9.0, 29.0 Hz, Ha, Hb), 5.02–5.08 (m, 5H, H-1′, –CH2Ph), 7.31–7.34 (m, 10H, Aromatic H′s); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 55.3, 56.4, 59.5, 61.2, 67.8, 67.8, 70.2, 72.7, 73.5, 75.6, 83.9, 98.3, 127.3, 127.7, 128.2, 128.3, 136.2 ppm; 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ 26.4 ppm. Mass spectrum (HRMS), m/z = 600.2231 (M + H)+, C27H38NO12P requires 600.2210.

((3-Hydroxy-2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)-(3-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl) pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)phosphonic acid (5).

Palladium (10%) on carbon (catalytic amount) was added to a solution of compound 16 (45.0 mg, 0.07 mmol) in methanol (0.5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under hydrogen atmosphere for 24 h. The mixture was filtered through Celite® followed by rinsing the Celite® with methanol. The filtrate was concentrated and the residue purified by gel permeation column chromatography on Sephadex LH-20 (H2O) to obtain pure compound 5 as a white solid; yield: quantitative (29 mg); yield: 76% (0.35 g); = −14.0° (c = 1, CHCl3); silica gel TLC Rf = 0.45 (3 : 7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 3.41–3.68 (m, 4H, H-1, H-4, H-e, H-f), 3.76–3.97 (m, 8H, H-a, H-b, H-c, H-d, H-5′, H-2′, H-6,6′), 4.25 (t, 1H, J = 5.7 Hz, H-3′), 4.35 (t, 1H, J = 5.6 Hz, H-4′), 5.21 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H, H-1′); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 57.1, 58.3, 60.3, 62.1, 63.2, 65.6, 69.3, 70.9, 72.4, 72.6, 73.6, 80.5, 98.1 ppm; 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.3 ppm. Mass spectrum (HRMS), m/z = 418.1124 (M – H)−, C13H26NO12P requires 418.1114.

Dibenzyl ((3-hydroxy-2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)-(3-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethyl)phosphonate (17).

To a solution of 14 (0.15 g, 0.49 mmol) in dichloromethane (1.0 mL) was passed ozone at −78 °C until the solution turned light blue. The reaction was quenched with dimethyl sulfide (91 μL, 1.2 mmol). The resulting solution was poured into water and extracted multiple times with dichloromethane. The combined extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated to afford a colorless oil of crude dibenzyl (2-oxoethyl) phosphonate (15) which was in the next step without further purification. 2,5-Dideoxy-3-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl-2,5-imino-d-mannitol 4 (45 mg, 0.138 mmol) was taken up in methanol (1 mL). This solution was added to aldehyde 15 and stirred 10 min at room temperature. To the solution was added sodium cyanoborohydride (17.34 mg, 0.276 mmol) in one portion followed by overnight stirring (~16 h). The solution was concentrated to dryness and dissolved in a minimal amount of water and loaded on a C18 column. The column was eluted with a solution of H2O-MeOH (1 : 1). The purified product was evaporated under reduced pressure to obtain 17 as colorless solid; yield: 56% (47 mg); = −14.0° (c = 1, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 2.14–2.26 (m, 2H, H-g, H-h), 3.03–3.43 (m, 4H, H-1, H-4, H-e, H-f), 3.62 (m, 10H, H-a, H-b, H-c, H-d, H-2′, H-3′, H-4′, H-5′, H-6a′, H-6b′), 5.01–5.14 (m, 5H, –CH2Ph, H-1′), 7.36–7.42 (m, 10H, Aromatic H′s); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 23.9, 24.8, 39.8, 47.1, 47.3, 47.4, 47.6, 47.8, 48.0, 58.7, 59.2, 61.3, 61.30, 66.6, 67.1, 67.4, 67.6, 68.7, 70.3, 71.9, 72.8, 73.6, 75.8, 84.3, 98.1, 127.7, 127.8, 127.9, 128.2, 136.2 ppm; 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ 29.1 ppm. Mass spectrum (HRMS), m/z = 614.2359 (M + H)+, C28H40NO12P requires 614.2366.

((3-Hydroxy-2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)-(3-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl) pyrrolidin-1-yl)ethyl)phosphonic acid (6).

Palladium (10%) on carbon (catalytic amount) was added to a solution of compound 17 (47.0 mg, 0.07 mmol) in methanol (0.5 mL). The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature under hydrogen atmosphere for 24 h. The mixture was filtered through Celite® followed by rinsing the Celite® with methanol. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue purified by gel permeation column chromatography on Sephadex LH-20 (H2O) to obtain compound 6 as a colorless solid; yield: quantitative (32 mg); = −14.0° (c = 1, CHCl3); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 1.94–2.16 (m, 2H, H-g, H-h), 3.32–4.08 (m, 14H, H-1, H-4, H-e, H-f, H-a, H-b, H-c, H-d, H-2′, H-3′, H-4′, H-5′, H-6a′, H-6b′), 5.15 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, H-1′); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 55.8, 56.5, 58.8, 60.4, 69.3, 70.8, 72.5, 72.6, 72.7, 73.4, 79.6, 80.9, 97.7 ppm; 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ 18.8 ppm. Mass spectrum (HRMS), m/z = 434.1433 (M + H)+, C14H28NO12P requires 434.1427.

Sco GlgEI-V279S inhibition studies

The Kis for inhibitors against Sco GlgEI-V279S were determined using EnzChek® Phosphate Assay Kit (Molecular Probes) as part of a coupled enzyme assay as previously described.15 Using this assay, we determined a Ki for compound 5 and 6 against Sco GlgEI-V279S. Assays were performed at 22 °C in a 96 well format on a Spectra max 340PC (Molecular Devices). Inhibition was determined by comparing the relative rate of the reaction performed with inhibitor against a reaction that contained no inhibitor (), where and Vo are steady-state rates with and without inhibitor, respectively. The equilibrium dissociation constants (Ki) for inhibitor 5 and 6 for Sco GlgE found to be 45.03 ± 4.01 μM and 95.98 ± 16.02 μM respectively. Ki was obtained by fitting the data into eqn (1) using Prism.

| (1) |

KM is the Michaelis–Menten constant for M1P; [S] and [I] are the concentrations of M1P and inhibitor, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work was support by a grant from National Institution of Health (Grant No. AI105084) to S. J. S. and D. R. R.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Experimental details, 1H and 13C NMR spectra for new compounds (10, 15, 16, 17, 5 and 6), enzyme inhibition, data collection and refinement statistics (PDF). See DOI: 10.1039/c7ob00388a

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Organization WH, Global tuberculosis report 2016, World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaitonde V and Sucheck SJ, Carbohydrate Chemistry: State of the Art and Challenges for Drug Development: An Overview on Structure, Biological Roles, Synthetic Methods and Application as Therapeutics, 2015, p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thanna S and Sucheck SJ, MedChemComm, 2016, 7, 69–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalscheuer R, Syson K, Veeraraghavan U, Weinrick B, Biermann KE, Liu Z, Sacchettini JC, Besra G, Bornemann S and Jacobs WR, Nat. Chem. Biol, 2010, 6, 376–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbein AD, Pastuszak I, Tackett AJ, Wilson T and Pan YT, J. Biol. Chem, 2010, 285, 9803–9812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra G, Chater KF and Bornemann S, Microbiology, 2011, 157, 1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bornemann S, Biochem. Soc. Trans, 2016, 44, 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, Coutinho PM and Henrissat B, Nucleic Acids Res, 2014, 42, D490–D495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalscheuer R and Jacobs WR, Drug News Perspect, 2010, 23, 619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syson K, Stevenson CEM, Rashid AM, Saalbach G, Tang MH, Tuukkanen A, Svergun DI, Withers SG, Lawson DM and Bornemann S, Biochemistry, 2014, 53, 2494–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syson K, Stevenson CEM, Rejzek M, Fairhurst SA, Nair A, Bruton CJ, Field RA, Chater KF, Lawson DM and Bornemann S, J. Biol. Chem, 2011, 286, 38298–38310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindenberger JJ, Veleti SK, Wilson BN, Sucheck SJ and Ronning DR, Sci. Rep, 2015, 5, 12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veleti SK, Lindenberger JJ, Ronning DR and Sucheck SJ, Bioorg. Med. Chem, 2014, 22, 1404–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thanna S, Lindenberger JJ, Gaitonde VV, Ronning DR and Sucheck SJ, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2015, 13, 7542–7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veleti SK, Lindenberger JJ, Thanna S, Ronning DR and Sucheck SJ, J. Org. Chem, 2014, 79, 9444–9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitaoka M and Hayashi K, Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol, 2002, 14, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lairson LL and Withers SG, Chem. Commun, 2004, 2243–2248, DOI: 10.1039/b406490a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voet JG and Abeles RH, J. Biol. Chem, 1970, 245, 1020–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies GJ, Ducros VMA, Varrot A and Zechel DL, Biochem. Soc. Trans, 2003, 31, 523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macgregor EA, Janecek S and Svensson B, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2001, 1546, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen JE and Borchert TV, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2000, 1543, 253–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller M and Nidetzky B, FEBS Lett, 2007, 581, 1403–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfenden R, Lu XD and Young G, J. Am. Chem. Soc,1998, 120, 6814–6815. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfenden R and Snider MJ, Acc. Chem. Res, 2001, 34, 938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gloster TM and Davies GJ, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2010, 8, 305–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vocadlo DJ and Davies GJ, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 2008, 12, 539–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasella A, Davies GJ and Bohm M, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 2002, 6, 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rye CS and Withers SG, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 2000, 4, 573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lillelund VH, Jensen HH, Liang XF and Bols M, Chem. Rev. , 2002, 102, 515–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishida N, Kumagai K, Niida T, Tsuruoka T and Yumoto H, J. Antibiot, 1967, 20, 66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inouye S, Tsuruoka T, Ito T and Niida T, Tetrahedron, 1968, 24, 2125–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Legler G, Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem, 1990, 48, 319–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajimoto T, Liu KKC, Pederson RL, Zhong ZY, Ichikawa Y, Porco JA and Wong CH, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1991, 113, 6187–6196. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dharuman S, Wang YC and Crich D, Carbohydr. Res, 2016, 419, 29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleet GWJ, Smith PW, Evans SV and Fellows LE, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun, 1984, 1240–1241, DOI: 10.1039/c39840001240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis BG, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2009, 20, 652–671. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu KKC, Kajimoto T, Chen LR, Zhong ZY, Ichikawa Y and Wong CH, J. Org. Chem, 1991, 56, 6280–6289. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provencher L, Steensma DH and Wong CH, Bioorg. Med. Chem, 1994, 2, 1179–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Behr JB, Chevrier C, Defoin A, Tarnus C and Streith J, Tetrahedron, 2003, 59, 543–553. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JH, Curtis-long MJ, Seo WD, Lee JH, Lee BW, Yoon YJ, Kang KY and Park KH, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2005, 15, 4282–4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alam MA, Kumar A and Vankar YD, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2008, 4972–4980, DOI: 10.1002/ejoc.200800649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shih H-W, Chen K-T, Chen S-K, Huang C-Y, Cheng T-JR, Ma C, Wong C-H and Cheng W-C, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2010, 8, 2586–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vanek V, Budesinsky M, Rinnova M and Rosenberg I, Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 862–876. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matveeva EV, Petrovskii PV and Odinets IL, Tetrahedron Lett, 2008, 49, 6129–6133. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamagishi T, Fujii K, Shibuya S and Yokomatsu T, Tetrahedron, 2006, 62, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Webb MR, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 1992, 89, 4884–4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longshaw AI, Adanitsch F, Gutierrez JA, Evans GB, Tyler PC and Schramm VI, J. Med. Chem, 2010, 53, 6730–6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Julina R and Vasella A, Helv. Chim. Acta, 1985, 68, 819–830. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syson K, Stevenson CEM, Miah F, Barclay JE, Tang M, Gorelik A, Rashid AM, Lawson DM and Bornemann S, J. Biol. Chem, 2016, 291, 21531–21540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.