Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is a multifactorial disease caused by a complex interaction of environmental and genetic factors. Some diabetes mellitus cases, however, are caused by a limited number of mutant genes. Chromosome 13q deletion syndrome, an extremely rare genetic disorder, is caused by structural and functional monosomy of the 13q chromosomal region. We report the case of a 38-year-old Japanese man with Chr13q deletion (a mosaic pattern with heterozygous ring Chr13q) who developed diabetes mellitus. Early-onset diabetes mellitus developed in this patient because of insulin resistance and a lack of adequate insulin secretion. Microarray analysis identified a 4.8-Mb deletion of distal Chr13q, leading to a copy number loss of 40 genes. Among those genes, the insulin receptor substrate 2 gene (IRS2) was the most likely causative candidate for the development of diabetes mellitus in this patient, based on the model of IRS2 knockout mice, which have abnormal glucose and insulin homeostasis closely resembling the human diabetes phenotype. These data provide important information regarding the contribution of a microdeletion of Chr13q, including in IRS2, to the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus in humans.

Keywords: array CGH, chromosome 13 deletion, insulin receptor substrate 2, ring chromosome

Chromosome 13q deletion (Chr13q−) syndrome, an extremely rare genetic disorder, is characterized by partial deletions of one of the long arms of Chr13 [1, 2]. One subtype of Chr13q− syndrome, a ring Chr13, exhibits breakage and reunion at breakage points on Chr13p and Chr13q, resulting in ring formation. This subtype involves deletions of the distal chromosome region from breakage points. Although clinical findings correlate with the amount of missing genetic material, the phenotype-genotype correlation has not been clarified, because of the low frequency of the disorder [1]. In addition, most previous cases have been reported as diseases of infants and young children, and the phenotypes of the disease in adulthood have not been clarified to date. Here, we describe a 38-year-old man determined to have Chr13q− syndrome with a microdeletion in Chr13q34qter who developed early-onset diabetes mellitus and other phenotypes. We discuss the relationship between these phenotypes and the genes harbored on Chr13q34qter. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and his parent.

1. Case Description

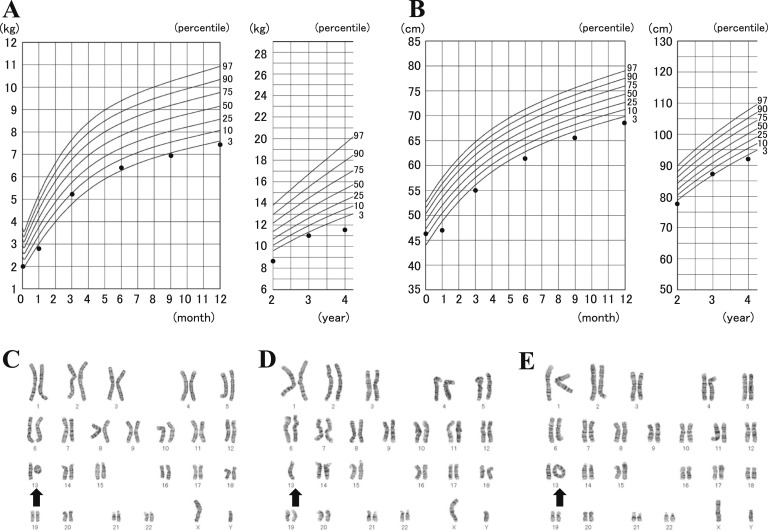

The patient is a 38-year-old Japanese man. He was born after an uneventful 40-week gestation with a birth weight of 2,000 g (less than the third percentile relative to the Japanese population), length of 46.5 cm (10th to 25th percentile), chest circumference of 28.5 cm (less than the third percentile), and head circumference of 28.0 cm (less than the third percentile). The patient’s mother, a 29-year-old woman, and her 30-year-old husband were healthy, nonconsanguineous, and had no family history of genetic disorders or congenital malformations. The patient had normal tonus and no feeding difficulties, but all developmental milestones, such as motor skills, language, and cognitive development, were delayed. At more advanced ages, growth retardation and developmental disability became apparent (Fig. 1A and 1B). At the age of 6 years, he was diagnosed with ring Chr13 syndrome. Electroencephalography and brain computed tomography indicated no brain abnormalities. The karyotypes of his parents and younger brother were normal. He attended special classes for handicapped children after elementary school. After that, he had no severe medical illness until age 20 years.

Figure 1.

(A, B) Growth course from birth to 4 years of age in case patient: (A) body weight and (B) height. These data were obtained from a mother and baby notebook for medical and welfare records. The lines represent the standard growth curves of the Japanese population obtained from the website of Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (Japan) (http://www.mhlw.go.jp). (C–E) G-banding analysis was performed using phyto-hemoagglutinin–activated 72-hour cultures. A mosaic pattern comprised three distinct clonal cell populations. (C) Heterozygous ring Chr13, (D) Chr13 monosomy, and (E) heterozygous dicentric ring Chr13 were detected in 70%, 23%, and 7% of the analyzed cells, respectively. The arrow shows Chr13.

At the age of 21 years, glycosuria was noted in a medical checkup. He was not obese, height was 158.0 cm, weight was 54.0 kg, and body mass index was 21.6 (measured as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Soon after this medical checkup, he received a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. His fasting glucose and insulin levels were 127 mg/dL and 16 μU/mL, respectively, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance was 5.0 (reference value, <2.0). His HbA1c was 7.1%. Subsequently, at age 25 years, he was treated with per os medications (gliclazide 120 mg/d and metformin 750 mg/d). At age 26 years, he was admitted to our hospital and was changed to insulin therapy because of poor glucose control (HbA1c, 10.9%). After the hospitalization, he was diagnosed with having a prolonged prothrombin time and with Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome.

At 38 years old, the patient is not obese, height is 158.6 cm, weight is 57.7 kg, and body mass index is 22.9. He has no diabetic complications and no acanthosis nigricans. Anti-islet autoantibodies (specifically, GAD antibody and IA-2 antibody) were negative. Serum C-peptide levels at fasting and after injection of glucagon were 1.05 ng/mL and 1.95 ng/mL, respectively. The insulinogenic index was 0.1. The K index of the insulin tolerance test (using regular insulin, 0.1 U/kg body weight), an indicator of insulin resistance, was 1.70 (reference value, 5.65% ± 0.35%/min) [3], demonstrating severe insulin resistance with insufficient compensation by insulin secretion. Computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen demonstrated no abnormalities.

The patient received insulin therapy (32 units daily of rapid-acting insulin, namely, insulin aspart; and 14 units daily of long-acting insulin, namely, insulin degludec). After carrying out genome-wide microarray analysis, his medication was changed. A thiazolidine derivative (30 mg/d), which has been reported to augment IRS-2 expression [4], was added to his insulin therapy, resulting in a marked decrease in the amount of insulin required daily (lowering insulin aspart to 20 units/d and degludec to 7 units/d) and the improvement of glycemic control (his HbA1c level dropped from 8.5% to 7.4%).

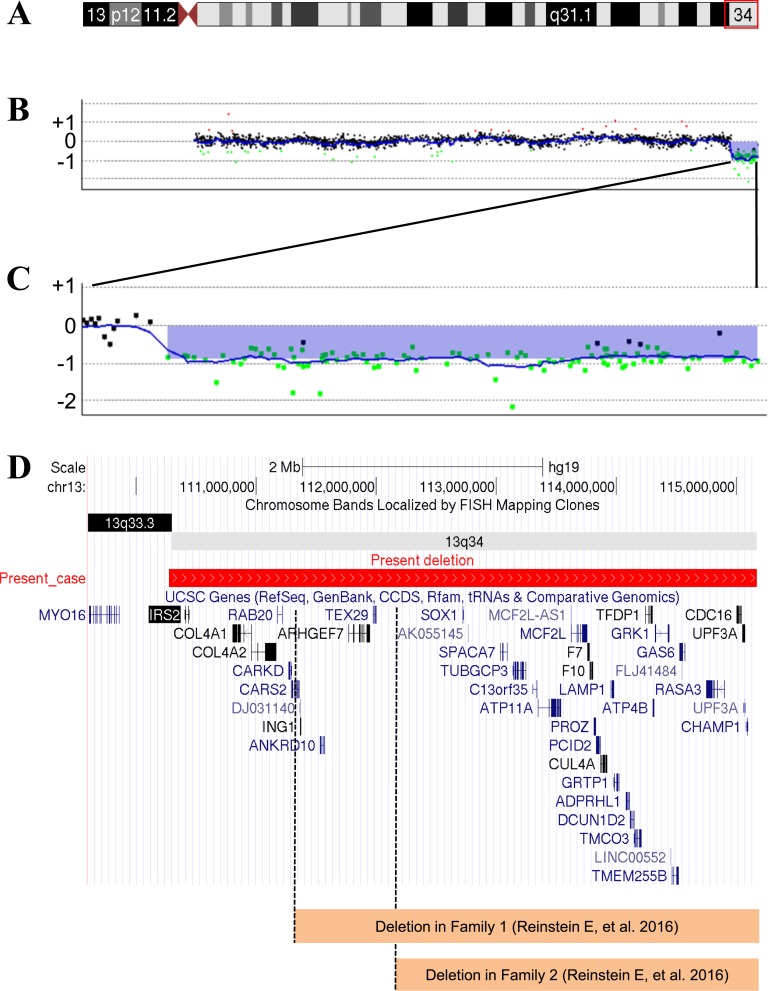

G-banding analysis demonstrated that no normal Chr13 was observed in 30 peripheral blood lymphocytes. The karyotype was a mosaic pattern (Fig. 1C–1E). The microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization analysis (Fig. 2) showed a 4.8-Mb region of hemizygous loss in Chr13q34qter containing 40 genes (Table 1). The analysis showed no other structural genomic imbalances apart from the Chr13q loss.

Figure 2.

(A) Chromosome ideogram. The impaired chromosomal region is highlighted. (B) Microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis in Chr13. The aCGH analysis was performed using the Agilent Oligo Microarray Kits 60K (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as described previously [10]. A 4.8-Mb region of hemizygous loss in Chr13q34qter (Chr13: 110,276,126–115,059,020). (C) Magnification of the hemizygous loss region. (D) Forty genes located in the hemizygous loss region of Chr13q34qter. The deleted regions in two families reported by Reinstein et al. [8] are shown. The differences in the hemizygous loss region between our patient and those families include IRS2, COL4A1, COL4A2, RAB20, CARKD, and CARS2. FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Table 1.

Summary of the Genes Listed in the Deletion Region

| Gene Symbol (MIM Number for Genes) | Description | Position in Chromosome 13 | Phenotype (MIM Number for Phenotype, Inheritance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRS2 (600797) | Insulin receptor substrate 2 | 110,406,184–110,438,914 | Diabetes mellitus, noninsulin-dependent (125853, AD) |

| COL4A1 (120130) | Collagen, type IV, α 1 | 110,801,310–110,959,496 | Retinal arteries, tortuosity of (180000, AD) |

| Angiopathy, hereditary, with nephropathy, aneurysms, and muscle cramps (611773, AD) | |||

| Brain small-vessel disease with or without ocular anomalies (607595, AD) | |||

| Porencephaly 1 (175780, AD) | |||

| COL4A2 (120090) | Collagen, type IV, α 2 | 110,959,631–111,165,373 | Porencephaly 2 (614483, AD) |

| Hemorrhage, intracerebral, susceptibility to (614519) | |||

| RAB20 | RAB20, member RAS oncogene family | 111,175,413–111,214,071 | |

| CARKD (615910) | Carbohydrate kinase domain containing | 111,267,931–111,292,342 | |

| CARS2 (612800) | Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (putative) | 111,293,757–111,358,480 | Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 27 (616672, AR) |

| DJ031140 | cDNA clone IMAGE:4905026 | 111,363,576–111,365,814 | |

| ING1 (601566) | Inhibitor of growth family, member 1 | 111,367,359–111,373,421 | Squamous cell carcinoma, head and neck, somatic (275355) |

| ANKRD10 | Ankyrin repeat domain 10 | 111,530,887–111,567,416 | |

| ARHGEF7 (605477) | Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 7 | 111,767,624–111,947,542 | |

| TEX29 | Testis expressed 29 | 111,973,015–111,996,594 | |

| SOX1 (602148) | SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 1 | 112,721,913–112,726,020 | |

| AK055145 | cDNA FLJ30583 fis, clone BRAWH2007406 | 112,762,364–112,764,886 | |

| SPACA7 | Sperm acrosome associated 7 | 113,030,651–113,089,009 | |

| TUBGCP3 | Tubulin, γ complex associated protein 3 | 113,139,328–113,242,481 | |

| C13orf35 | Chromosome 13 open reading frame 35 | 113,301,358–113,338,811 | |

| ATP11A | ATPase, class VI, type 11A | 113,344,643–113,541,482 | |

| MCF2L-AS1 | MCF2L antisense RNA 1 | 113,621,798–113,622,952 | |

| MCF2L (609499) | MCF.2 cell line derived transforming sequence-like | 113,623,535–113,754,053 | |

| F7 (613878) | Coagulation factor VII (serum prothrombin conversion accelerator) | 113,760,102–113,774,995 | Factor VII deficiency (227500) |

| Myocardial infarction, decreased susceptibility to (608446, AR) | |||

| F10 (613872) | Coagulation factor X | 113,777,113–113,803,843 | Factor X deficiency (227600, AR) |

| PROZ (176895) | Protein Z, vitamin K–dependent plasma glycoprotein | 113,812,968–113,826,698 | Protein Z deficiency (614024) |

| PCID2 | PCI domain containing 2 | 113,831,853–113,863,029 | |

| CUL4A (603137) | Cullin 4A | 113,863,931–113,919,392 | |

| LAMP1 (153330) | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) | 113,951,469–113,977,741 | |

| GRTP1 | Growth hormone–regulated TBC protein 1 | 113,978,505–114,018,463 | |

| ADPRHL1 (610620) | ADP-ribosylhydrolase like 1 | 114,076,260–114,107,839 | |

| DCUN1D2 | DCN1, defective in cullin neddylation 1, domain containing 2 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | 114,110,134–114,145,023 | |

| TMCO3 (617134) | Transmembrane and coiled-coil domains 3 | 114,145,308–114,204,544 | |

| TFDP1 (189902) | Transcription factor Dp-1 | 114,239,056–114,295,788 | |

| ATP4B (137217) | ATPase, H+/K+ exchanging, β polypeptide | 114,303,122–114,312,513 | |

| GRK1 (180381) | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 1 | 114,321,597–114,438,637 | Oguchi disease-2 (613411) |

| LINC00552 | Long intergenic nonprotein coding RNA 552 | 114,451,484–114,454,062 | |

| TMEM255B | Transmembrane protein 255B | 114,462,216–114,514,899 | |

| GAS6 (600441) | Growth arrest–specific 6 | 114,523,522–114,567,046 | |

| FLJ41484 | cDNA FLJ35543 fis, clone SPLEN2002957 | 114,545,293–114,548,541 | |

| RASA3 (605182) | RAS p21 protein activator 3 | 114,747,194–114,898,095 | |

| CDC16 (603461) | Cell division cycle 16 | 115,000,362–115,038,150 | |

| UPF3A (605530) | UPF3 regulator of nonsense transcripts homolog A (yeast) | 115,047,059–115,071,291 | |

| CHAMP1 (616327) | Chromosome alignment maintaining phosphoprotein 1 | 115,079,965–115,092,803 | Mental retardation, autosomal dominant 40 (616579, AD) |

This table was created based on information from GRCh37/hg19 (https://genome-asia.ucsc.edu/index.html).

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; MIM, Mendelian Inheritance in Man.

2. Discussion

The common characteristics of patients with ring Chr13 include microcephaly, mental retardation, growth retardation, dysmorphic facies, and autism [5]. The clinical characteristics and severity depend on the size of the deleted region, likely due to differences in the number of absent genes. The patient in this report with ring Chr13 has relatively mild symptoms compared with previous reports of Chr13q34 deletions [1, 2], suggesting a mild decrease of gene dosage, because of this patient’s mosaicism. It is noteworthy that diabetes mellitus developed in this patient; this was described in only one case previously [6], to our knowledge. In that report, diabetes mellitus was noted to have developed when that patient was 12 years old; treatment was insulin [6]. No other information was available in the report. Therefore, the case reported here provides new information about diabetes mellitus in Chr13q− syndrome.

To identify the genes that are potentially affected by the deletion of Chr13q34qter that lead to abnormal glucose homeostasis due to gene dosage alteration, we retrieved information from an online database (https://genome-asia.ucsc.edu/index.html). Among the 40 genes located in the hemizygous loss region of Chr13q34qter, insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2) may be a causative candidate gene that explains the phenotype of diabetes mellitus in our patient. Dysfunction of IRS2 contributes to insulin resistance, as evidenced by the progressive deterioration of glucose homeostasis observed in Irs2 knockout mice [7].

Reinstein et al. [8] reported on two families with heterozygous microdeletions of Chr13q34 in which an intellectual disability developed. Their phenotypes were mild compared with previous reports of Chr13q34 deletions [1, 2] and equal to that of our patient, except for the development of diabetes mellitus. Those patients were all older than 20 years (range, 22 to 57 years), had intellectual disabilities, and were overweight, with no additional medical illness. As shown in Fig. 2D, the region of Chr13q34 deletion in our case is different from those in previous cases [8], leading to gene dosage defects in an additional six genes: IRS2, COL4A1, COL4A2, RAB20, CARKD, and CARS2. Because diabetes did not develop in anyone in the two families and none of them had an IRS2 defect, it is reasonable to speculate that the IRS2 defect caused diabetes mellitus in our patient. Needless to say, the other genes except for IRS2 may also contribute to the development of diabetes.

Besides diabetes mellitus, our patient’s clinical picture included a prolonged prothrombin time and WPW syndrome. The prolonged prothrombin time may be caused the by defect in F7, F10, or PROZ, and similar cases have been reported [9]. The relationship between WPW syndrome and the deletion of Chr13q34 is currently unknown because no candidate genes are located in the deleted region and, to our knowledge, no other case with WPW syndrome has been reported.

3. Conclusion

The patient in the current report, who has ring Chr13, has an apparently unique phenotype of delayed growth, mental retardation, and the development of early-onset diabetes mellitus. Microarray analysis detected a 4.8-Mb deletion of Chr13q34 encompassing 40 genes. The region contains a candidate gene for diabetes, IRS2. These data provide important information regarding the contribution of the microdeletion, including in IRS2, to the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus in humans. Additional studies, including the accumulation of additional case reports, are needed to clarify these findings in humans.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan, to N.B.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Chr13q-

chromosome 13q deletion

- IRS-2

insulin receptor substrate 2

- WPW

Wolff-Parkinson-White

References and Notes

- 1. Quélin C, Bendavid C, Dubourg C, de la Rochebrochard C, Lucas J, Henry C, Jaillard S, Loget P, Loeuillet L, Lacombe D, Rival JM, David V, Odent S, Pasquier L. Twelve new patients with 13q deletion syndrome: genotype-phenotype analyses in progress. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52(1):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walczak-Sztulpa J, Wisniewska M, Latos-Bielenska A, Linné M, Kelbova C, Belitz B, Pfeiffer L, Kalscheuer V, Erdogan F, Kuss AW, Ropers HH, Ullmann R, Tzschach A. Chromosome deletions in 13q33-34: report of four patients and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(3):337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonora E, Moghetti P, Zancanaro C, Cigolini M, Querena M, Cacciatori V, Corgnati A, Muggeo M. Estimates of in vivo insulin action in man: comparison of insulin tolerance tests with euglycemic and hyperglycemic glucose clamp studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68(2):374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hirukawa H, Kaneto H, Shimoda M, Kimura T, Okauchi S, Obata A, Kohara K, Hamamoto S, Tawaramoto K, Hashiramoto M, Kaku K. Combination of DPP-4 inhibitor and PPARγ agonist exerts protective effects on pancreatic β-cells in diabetic db/db mice through the augmentation of IRS-2 expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;413:49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charalsawadi C, Maisrikhaw W, Praphanphoj V, Wirojanan J, Hansakunachai T, Roongpraiwan R, Sombuntham T, Ruangdaraganon N, Limprasert P. A case with a ring chromosome 13 in a cohort of 203 children with non-syndromic autism and review of the cytogenetic literature. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2014;144(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lagergren M, Börjeson M, Mitelman F. Prophase analysis of ring chromosome 13--an attempt at phenotype-karyotype correlation. Hereditas. 1980;93(2):231–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kubota T, Kubota N, Kadowaki T. Imbalanced insulin actions in obesity and type 2 diabetes: key mouse models of insulin signaling pathway. Cell Metab. 2017;25(4):797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reinstein E, Liberman M, Feingold-Zadok M, Tenne T, Graham JM Jr. Terminal microdeletions of 13q34 chromosome region in patients with intellectual disability: delineation of an emerging new microdeletion syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;118(1):60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurosawa H, Suzumura H, Okuya M, Fukushima K, Sugita K, Fujiwara T, Morishita E, Yoshioka A, Takamiya O, Arisaka O. Haemostatic management of surgery for imperforate anus in a patient with 13q deletion syndrome with combined deficiency of factors VII and X. Haemophilia. 2009;15(1):398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamamoto T, Shimojima K, Ondo Y, Shimakawa S, Okamoto N. MED13L haploinsufficiency syndrome: a de novo frameshift and recurrent intragenic deletions due to parental mosaicism. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(5):1264–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]