SUMMARY

Aim:

Quantify imaging abnormalities in a retrospective case series of patients with leptomeningeal metastasis (LM).

Methods:

A total of 240 adult patients with LM (125 nonbrain solid tumor patients with positive cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] cytology; 40 nonbrain solid tumor patients with negative CSF cytology and positive MRI; and 50 lymphoma and 25 leukemia patients with positive CSF-flow cytometry) underwent brain and entire spine MRI and radioisotope CSF-flow studies prior to treatment.

Results:

MRI was more often abnormal in solid tumors (40 CSF defined and 100% in MRI defined) compared with hematologic cancers (16–20%; p = 0.03). Similarly, CSF-flow studies was more often abnormal in solid tumors (25–28%) compared with hematologic cancers (10–20%; p = 0.04). MRI and flow-study abnormalities altered therapy in a third of solid tumors and 15% of hematologic cancers.

Conclusion:

Although imaging abnormalities are less often seen in hematologic cancers compared with solid tumor LM, imaging abnormalities frequently result in treatment alteration.

Practice Points.

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) is common and is seen in 2–5% of all patients with cancer.

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with LM is based on expert opinion and consensus recommends the use of neuraxis (brain and spine) MRI and radioisotope cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow studies prior to consideration of LM-directed treatment.

This retrospective study is unique in that 240 adult patients with LM considered for LM-directed treatment underwent pretreatment CNS imaging, including brain and spine MRI and radioisotope CSF-flow studies.

MRI abnormalities (brain or spine) were seen in 40% of patients with solid tumors and positive CSF cytology. CSF-flow abnormalities were seen in 28% of these patients.

MRI abnormalities (brain or spine) were seen in 20% of patients with lymphomatous meningitis and 16% of patients with leukemic meningitis. CSF-flow abnormalities were seen in 10 and 20% of these patients, respectively.

A total of 32% of all patients with solid tumors and 15% of all patients with hematologic cancer-related LM had their treatment modified based upon demonstration of abnormalities by neuraxis imaging.

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) is the third most common CNS metastatic complication of cancer, occurring in 3–5% of all patients with solid tumor cancers [1–3]. Hematological cancers (leukemia and lymphoma) have higher rates of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-disseminated disease (leukemic and lymphomatous meningitis, respectively) that are determined, in part, by the disease profile. Nonetheless, there are limited evidence-based guidelines regarding the diagnostic and evaluative neuroradiographic management of LM [4–15]. There is, however, general agreement, for example, articulated in the CNS tumor section of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, that CSF should be interrogated for tumors and CNS-directed neuroimaging should be performed prior to commencing therapy. At present, however, there is no large study (prospective or retrospective) that evaluates both brain and spine imaging utilizing contrast-enhanced MRI as well as radioisotope CSF-flow studies prior to treatment in patients with LM [4–15]. This retrospective case series of 240 patients with both an extracranial solid tumor and hematological cancer-related LM, characterizes brain and spine MRI findings as well as radioisotope CSF-flow study findings prior to treatment.

Methods

▪ Patient population

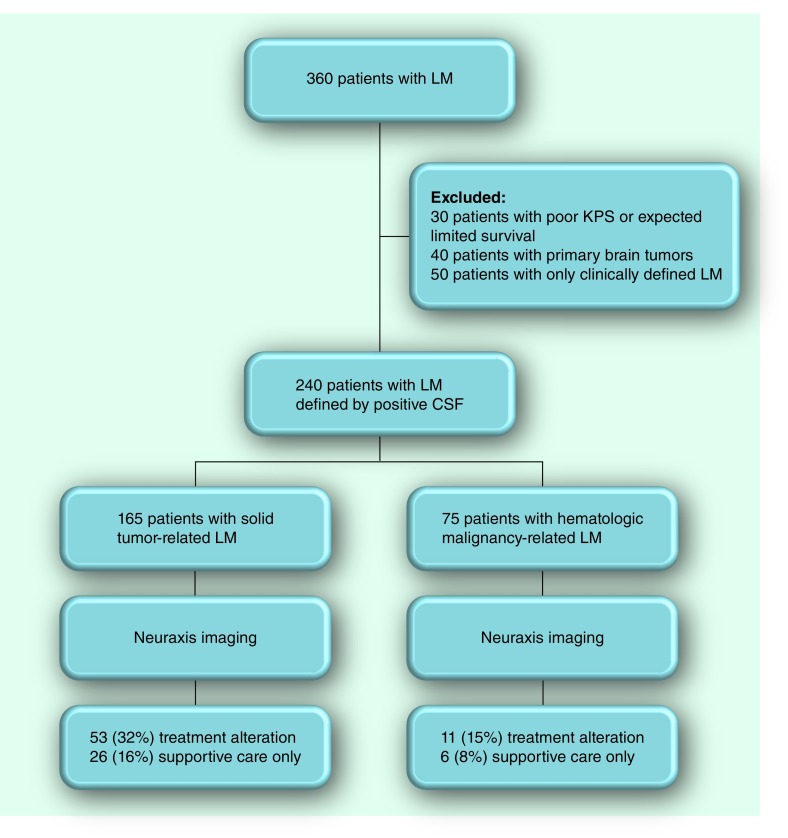

The retrospective analysis (collected from five institutions) used data from January 1987 to December 2011. A total of 240 adult patients (median age of 58 years; range: 20–86 years) with LM defined by CSF positive for cancer (defined as positive or suspicious by the cytopathologist; atypical was considered negative) with one patient group exception (solid cancers with negative CSF cytology; see below) were evaluated and considered for LM-directed treatment (Table 1). Patients with LM defined clinically, negative CSF cytology or flow cytometry, normal neuraxis imaging and patients with primary brain tumors were not included in this retrospective imaging analysis (Figure 1). Approximately two-thirds of these patients have previously been reported in other contexts, not, however, specifically addressing pretreatment neuroimaging findings [12,14–23]. In addition to excluding patients with negative CSF cytology or flow as well as normal neuraxis MRI, patients not considered candidates for LM-directed treatment (defined by a Karnofsky performance status <60%, or competing and progressive systemic disease) were not evaluated in this analysis (Figure 1). One category of solid tumor-related LM considered in this analysis was defined by a LM-compatible clinical syndrome, negative CSF cytology and neuraxis imaging demonstrating radiographic abnormalities consistent with LM. All but 25 patients (eight solid tumors and 17 hematologic malignancies) were symptomatic with signs and symptoms of LM.

Table 1. . Characteristics of the patient population.

| Patient characteristic | Solid tumor | Lymphoma | Leukemia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytology negative (n = 40) | Cytology positive (n = 125) | Flow cytometry positive (n = 50) | Flow cytometry positive (n = 25) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Median | 56 | 58 | 60 | 62 | |||

| Range | 20–71 | 32–78 | 30–86 | 31–82 | |||

| Gender (%) | |||||||

| Male | 52 | 60 | 50 | 56 | |||

| Female | 48 | 40 | 50 | 44 | |||

| Karnofsky performance status (%) | |||||||

| Median | 80 | 70 | 80 | 80 | |||

| Range | 50–100 | 50–100 | 50–100 | 50–100 | |||

| Symptomatic; % (n) | |||||||

| No | 18 (7) | 0 | 5 (3) | 15 (4) | |||

| Yes | 72 (33) | 100 (125) | 95 (47) | 85 (21) | |||

| Tumor histology; % (n) | |||||||

| Breast | 45 (18) | 45 (56) | |||||

| NSCLC | 27.5 (11) | 35 (44) | |||||

| Melanoma | 15 (6) | 10 (13) | |||||

| SCLC | 5 (2) | 5 (6) | |||||

| Other | 7.5 (3) | 5 (6) | |||||

| DLBCL | 80 (39) | ||||||

| Follicular lymphoma | 10 (5) | ||||||

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 5 (3) | ||||||

| Burkitt's lymphoma | 5 (3) | ||||||

| AML | 64 (16) | ||||||

| ALL | 20 (5) | ||||||

| CLL | 8 (2) | ||||||

| CML | 8 (2) | ||||||

ALL: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: Acute myelogenous leukemia; CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML: Chronic myelogenous leukemia; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; NSCLC: Non-small-cell lung cancer; SCLC: Small-cell lung cancer.

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram.

CFS: Cerebrospinal fluid; LM: Leptomeningeal metastasis; KPS: Karnofsky performance status.

All patients underwent a similar pretreatment LM evaluation including CSF assessment (cytology for solid tumors or flow cytometry and cytology for hematological cancers), contrast-enhanced brain and spine MRI, and a radioisotope 111In CSF-flow study as previously reported [12,14–23]. LM was confirmed in all patients (except for a group of 40 patients with solid tumors and radiographic-only LM) by either positive CSF cytology (in instances of solid tumors and hematologic cancers) or flow cytometry (in hematologic cancers).

The primary tumor histology in patients with solid tumor-related LM (n = 165; 69% of all patients in the analysis) was breast (45%), non-small-cell lung cancer (34%), melanoma (11%), small-cell lung cancer (5%) and others (6%). No primary brain tumors were considered in this retrospective study (Table 1). Hematologic cancers (n = 75; 31% of all patients in the analysis) were comprised of lymphoma (n = 50; 66% of all patients with hematologic cancer of which 80% were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) and leukemia (n = 25; 33% of all patients with hematologic cancer of which 64% were acute myelogenous leukemia). Karnofsky performance status ranged from 60–100 with a median of 80.

▪ Standard protocol approvals, registration & patient consents

Imaging

Data regarding CNS evaluation (brain and spine MRI, and CSF-flow studies) obtained before any LM-directed treatment and details of patients with LM was retrospectively collected and entered into a database. Institutional review board approval was obtained for data collection as well as patient consent for all data collection. No institutional or corporate funding was provided for this analysis.

MRI

All patients underwent complete neuraxis MRI (brain and complete spine) using standard sequences (T1-weighted, T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) and pre- and post-contrast imaging, as previously described [15,17–25]. All MRI was performed on either a 1.5 or 3.0 Tesla MRI scanner. Hydrocephalus was noted as present or absent to permit coding of radiographic abnormalities. Contrast-enhancing nodules were characterized as subarachnoid (defined as nodules in the CSF-containing subarachnoid space), ventricular or parenchymal (defined as nodules within brain parenchyma), and as present or absent. Pial enhancement was defined as focal, diffuse or none. Other abnormalities characterized and tabulated were ependymal, sulci, folia, cranial nerve or spinal root enhancement as either present or absent.

Radioisotope CSF-flow studies

All patients underwent either lumbar or ventricular administered 111In-diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid CSF-flow studies prior to treatment and as previously described [15,16,19–23]. Failure of radioisotope movement was defined as complete obstruction or blockage of CSF-flow and the site of CSF flow interruption was identified as either in the brain (ventricular, skull base or convexity) or spine (cervical, thoracic or lumbar). Partial CSF-flow obstruction was not considered as constituting a CSF-flow block.

Results

Four categories of patients with LM were retrospectively analyzed: solid tumor-related LM with (n = 125) or without (n = 40) positive CSF cytology; lymphoma (n = 50); and leukemia (n = 25) (Tables 2 & 3). Both categories of hematologic cancers (lymphoma and leukemia) were positive by CSF-flow cytometry and 40% were also positive by CSF cytology. In four patients (5% of all patients with hematologic cancers) with hematologic malignancies CSF-flow cytometry was negative and LM was determined by CSF cytology.

Table 2. . Contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain and spine in leptomeningeal metastasis.

| Region | Solid tumor† | Lymphoma† | Leukemia† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytology negative (n = 40); % (n) | Cytology positive (n = 125); % (n) | Flow cytometry positive (n = 50); % (n) | Flow cytometry positive (n = 25); % (n) | ||||

| Brain | |||||||

| Total | 75 (30) | 40 (50) | 15 (8) | 16 (4) | |||

| Hydrocephalus | 10 (4) | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 4 (1) | |||

| Nodules | 50 (20) | 35 (44) | 15 (8) | 8 (2) | |||

| ▪ Subarachnoid | 25 (10) | 10 (12) | 3 (2) | 0 | |||

| ▪ Ventricular | 10 (4) | 5 (6) | 3 (2) | 0 | |||

| ▪ Parenchymal | 50 (20) | 32 (40) | 12 (6) | 8 (2) | |||

| Pial enhancement | 50 (20) | 15 (19) | 6 (3) | 8 (2) | |||

| ▪ Focal | 40 (16) | 10 (12) | 3 (2) | 8 (2) | |||

| ▪ Diffuse | 10 (4) | 5 (6) | 3 (2) | 0 | |||

| Ependymal enhancement | 10 (4) | 5 (6) | 6 (3) | 4 (1) | |||

| Sulci enhancement | 10 (4) | 5 (6) | 3 (2) | 8 (2) | |||

| Folia enhancement | 10 (4) | 10 (12) | 3 (2) | 4 (1) | |||

| Cranial nerve enhancement | 10 (4) | 5 (6) | 3 (2) | 4 (1) | |||

| Spine | |||||||

| Total | 35 (14) | 15 (19) | 20 (10) | 12 (3) | |||

| Nodules | 25 (10) | 10 (13) | 6 (3) | 4 (1) | |||

| ▪ Subarachnoid | 20 (8) | 8 (10) | 6 (3) | 4 (1) | |||

| ▪ Parenchymal | 5 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Pial enhancement | 20 (8) | 10 (13) | 15 (8) | 8 (2) | |||

| ▪ Focal | 15 (6) | 8 (10) | 12 (6) | 4 (1) | |||

| ▪ Diffuse | 5 (2) | 2 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (1) | |||

| Nerve root enhancement | 10 (4) | 10 (13) | 12 (6) | 8 (2) | |||

| Normal | |||||||

| Total | 0 | 60 (75) | 80 (40) | 84 (21) | |||

Patients with multiple metastases are counted in every subcategory.

†As shown on MRI study.

Table 3. . Radioisotope cerebrospinal fluid-flow study in leptomeningeal metastasis.

| Site of obstruction | Solid tumor† | Lymphoma† | Leukemia† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytology negative (n = 40); % (n) | Cytology positive (n = 125); % (n) | Flow cytometry positive (n = 50); % (n) | Flow cytometry positive (n = 25); % (n) | ||||

| Brain | |||||||

| Total | 10 (4) | 9 (11) | 4 (2) | 8 (2) | |||

| Ventricular | 2.5 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Skull base | 2.5 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Convexity | 5 (2) | 5 (7) | 4 (2) | 8 (2) | |||

| Spine | |||||||

| Total | 15 (6) | 19 (24) | 6 (3) | 12 (3) | |||

| Cervical | 2.5 (1) | 4 (6) | 0 | 4 (1) | |||

| Thoracic | 2.5 (1) | 5 (6) | 2 (1) | 0 | |||

| Lumbar | 10 (4) | 10 (12) | 4 (2) | 8 (2) | |||

| Normal | |||||||

| Total | 75 (30) | 72 (90) | 90 (45) | 80 (20) | |||

†As shown on cerebrospinal fluid-flow study.

Abnormalities found by brain MRI were more common in cytology-negative solid tumor patients versus cytology-positive solid tumor patients (80 vs 40%; p = 0.03). Correspondingly normal brain MRI was more common in hematologic malignancies versus solid tumors (80–84% vs 60%; p = 0.05) (Table 2). Spine MRI demonstrated a relatively low incidence of magnetic resonance (MR) abnormalities (range: 12–35%, depending on the LM category) versus brain MRI (range: 15–75%, depending on the LM category). Nodular disease (either subarachnoid or parenchymal) constituted the most common MR abnormality followed by pial enhancement. Parenchymal metastases, either the brain or spine, were seen more often in solid tumor-related LM (nearly 50%) compared with hematological cancers (∼10%) (Table 2). The incidence of both nodular and pial enhancement was twice as frequent in the intracranial compared with the intraspinal compartment (p = 0.02) (Table 2). No difference was seen in either brain or spine MRI abnormalities when comparing symptomatic (n = 25) to asymptomatic patients (n = 215) with LM (p = 0.18). Among the three most common solid tumors (breast, non-small-cell lung cancer and melanoma), melanoma had a slight but insignificant increased frequency of spine and brain LM-related MRI abnormalities compared with breast and non-small-cell lung cancer (65 vs 56%; p = 0.08).

Radioisotope CSF-flow abnormalities were relatively uncommon (range: 10–28% dependent upon LM category) (Table 3). Similar to MRI, CSF-flow studies were more commonly abnormal in solid tumor compared with hematologic cancers (25–28 vs 10–20%; p = 0.04). The spine was slightly more common (∼1.5-times) than the brain as the site of CSF obstruction (p = 0.05). CSF obstruction was only seen by MRI in instances of hydrocephalus (Table 2), all other sites of CSF block were defined by radioisotope flow studies (Table 3). Consequently no correlation was seen between these imaging modalities when determining the site of CSF-flow obstruction.

As a consequence of abnormalities demonstrated by neuraxis imaging, 32% of patients with a solid tumor and 15% of patients with hematologic cancer-related LM required treatment alteration (Figure 1). Treatment alterations included a recommendation for no further treatment, administration of radiotherapy to sites of CSF-flow obstruction or radiographically identified nodular disease, coadministration of systemic chemotherapy for nodular disease not otherwise treated by radiotherapy and implantation of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for remediation of LM-related hydrocephalus. CSF-flow obstruction was identified by MRI only in patients with evidence of hydrocephalus (5–10% of patients with solid tumor-related LM and 3–4% of patients with hematologic malignancies). All other instances of CSF block were defined by radioisotope CSF-flow studies (25–28% in solid tumors and 10–20% in hematologic cancers). Identified radioisotope CSF-flow blocks necessitated a treatment modification that included CSF diversion by placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, site-directed radiotherapy or supportive care only (Table 3). Similarly, nodular disease in the spine (identified in 10–25% of patients with solid tumors and 4–6% of patients with hematologic cancer) altered therapy by suggesting no further therapy, administration of systemic chemotherapy or site-specific radiotherapy (Figure 1 & Table 2).

Discussion

Several aspects of this study warrant comment. First, this is the largest study (n = 240) of patients with LM reported in which pretreatment complete neuraxis imaging (brain and spine MRI and radioisotope CSF-flow studies) was performed. Notwithstanding the retrospective nature of the study, all patients underwent a similar imaging protocol. In addition, the study compares comparatively large categories of patients with LM, including patients with solid tumors with (n = 125) and without (n = 40) positive CSF cytology as well as hematologic cancers including both lymphoma (n = 50) and leukemia (n = 25). Excluded from this retrospective study were patients not considered a priori for treatment (due to a low performance status and limited survival based upon systemic disease) and patients with only clinical evidence of LM (defined by negative CSF cytology or flow cytometry and normal neuraxis MRI). There is scant literature describing neuraxis imaging in hematologic cancer-related LM [3,6,8,20,21,23]. What is unclear in the literature and notwithstanding recommendations from expert panels, for example, the National Cancer Consortium Network CNS malignancy guideline, is the utility of complete neuraxis imaging in patients with LM [4].

This retrospective study confirms the high yield of both neuraxis MRI and radioisotope CSF-flow studies in patients with either solid tumors or hematologic cancer-related LM. Notwithstanding the low frequency of spine MR abnormalities overall, up to a third of patients (range: 12–35% depending upon primary tumor) demonstrate radiographic abnormalities that impact LM-directed treatment (e.g., the administration of radiotherapy or utilization of systemic chemotherapy). The current findings corroborate previous suggestions regarding the utility of complete spine MR in LM, given the frequency of abnormalities and the impact on subsequent LM-directed therapy. Brain MRI findings were more common in solid tumors (40%) compared with hematologic cancers (20%), but of sufficient frequency in both cancer groups to warrant routine use in patients with suspected LM. Not unexpectedly the category of LM patients with solid tumors and negative CSF cytology had a higher incidence of brain radiographic abnormalities compared with CSF cytology positive solid tumors (80 vs 40%), in large part related to the manner in which this category of patients was defined. MRI abnormalities overall are more common in solid tumors, which is likely to be in part related to the increased adhesion inherent in solid tumors compared with hematologic cancers [2,3,6,9]. Notwithstanding this difference in biology, hematologic malignancy-related LM frequently manifests in both brain and spine MR abnormalities (16–20%) suggesting the utility of complete neuraxis imaging in lymphoma- and leukemia-related LM.

Similar to MRI, radioisotope CSF-flow studies were useful in all categories of LM, although again, abnormalities were less common in hematologic cancers versus solid tumors. The performance of CSF-flow studies in patients with LM has been controversial and most often the least frequently utilized imaging modality in assessing patients with LM. This controversy persists notwithstanding corroboration of the utility of CSF-flow studies by four independent investigators [10,11,13]. Determining CSF obstructions by CSF-flow studies are relevant for predicting disease outcome (as determined in previously [10–14]) and determining whether intra-CSF chemotherapy can access all sites of disease within the CSF compartment. This retrospective study again corroborates the usefulness of identifying sites of CSF-flow obstruction by radioisotope CSF-flow studies in both solid tumors and for the first time in a large cohort of hematologic cancers with LM. There is previous data to suggest that noncorrectable CSF-flow obstruction impacts survival; however, survival as a function of CSF abnormalities was not addressed in the current study [25]. Rather this study suggests that CSF-flow obstruction is common and impacts delivery of intra-CSF chemotherapy treatment. In patients not otherwise considered for intra-CSF chemotherapy, CSF-flow abnormalities may represent a prognostic marker of disease without necessarily changing therapy.

Conclusion & future perspective

Based upon the results of this retrospective study, complete neuraxis imaging using both MR and radioisotope CSF-flow in patients with either solid or hematologic cancer-related LM is useful to identify disease, in other words, to assist in diagnosis and determine disease volume and sites of disease that may impact LM-directed therapy. By way of example, patients with radiographically large volume disease and nonremediable CSF-flow obstruction identified by either MR or radioisotope flow imaging are poor candidates for treatment and are best served by supportive care only. By contrast, patients with parenchymal or subarachnoid nodules identified by neuraxis MRI often require adjunct treatment, for example, radiotherapy or systemic chemotherapy as intra-CSF chemotherapy inadequately treats solid tumor nodules [24]. In the current study, 32% of all patients with solid tumor- and 15% of all patients with hematologic cancer-related LM had treatment modified based upon demonstration of neuraxis imaging. Corroboration of the current retrospective study findings would best be accomplished in the context of a prospective study to provide evidence-based recommendations regarding the diagnostic work-up and potential treatment of patients with LM.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: ▪ of interest ▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Chamberlain MC. Leptomeningeal metastasis. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2010;22(6):627–635. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833de986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪ Contemporary review of leptomeningeal metastasis that discusses diagnosis and treatment.

- 2.Glantz MJ, Jaeckle KA, Chamberlain MC, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing intrathecal sustained-release cytarabine (DepoCyt) to intrathecal methotrexate in patients with neoplastic meningitis from solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5(11):3394–3402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪▪ One of two randomized clinical trials comparing sustained-release liposomal cytarabine to methotrexate in patients with carcinomatous meningitis.

- 3.Glantz MJ, LaFollette S, Jaeckle KA, et al. Randomized trial of a slow release vs. a standard formulation of cytarabine for the intrathecal treatment of lymphomatous meningitis. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17:3110–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪▪ One of two randomized clinical trials comparing sustained-release liposomal cytarabine to methotrexate in patients with lymphomatous meningitis.

- 4.Brem SS, Bierman PJ, Black P, et al. Central nervous system cancers: clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 2005;3(5):644–690. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2005.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain MC, Glantz M, Groves MD, Wilson WH. Diagnostic tools for neoplastic meningitis: detecting disease, identifying patient risk, and determining benefit of treatment. Semin. Oncol. 2009;36(4 Suppl. 2):S35–S45. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke JL, Perez HR, Jacks LM, Panageas KS, DeAngelis LM. Leptomeningeal metastases in the MRI era. Neurology. 2010;74(18):1449–1454. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dc1a69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪ Retrospective study using selected MRI in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis.

- 7.Collie DA, Brush JP, Lammie GA, et al. Imaging features of leptomeningeal metastases. Clin. Radiol. 1999;54(11):765–771. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(99)91181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straathof CS, de Bruin HG, Dippel DW, Vecht CJ. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and cerebrospinal fluid cytology in leptomeningeal metastasis. J. Neurol. 1999;246(9):810–814. doi: 10.1007/s004150050459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freilich RJ, Krol G, DeAngelis LM. Neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid cytology in the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis. Ann. Neurol. 1995;38(1):51–57. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman SA, Trump CL, Chen DCP, Thompson G, Camargo E. Cerebrospinal flow abnormalities in patients with neoplastic meningitis. Am. J. Med. 1982;73:641–647. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ▪ First article to highlight cerebrospinal fluid flow abnormalities defined by nuclear imaging in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis.

- 11.Glantz MJ, Hall WA, Cole BF, et al. Diagnosis, management, and survival of patients with leptomeningeal cancer based on cerebrospinal fluid-flow status. Cancer. 1995;75(12):2919–2931. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2919::aid-cncr2820751220>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamberlain MC, Corey-Bloom J. Leptomeningeal metastasis: Indium-DTPA CSF flow studies. Neurology. 1991;41:1765–1769. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.11.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason WP, Yeh SD, De Angelis LM. 111Indium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid cerebrospinal fluid flow studies predict distribution of intrathecally administered chemotherapy and outcome in patients with leptomeningeal metastases. Neurology. 1998;50(2):438–444. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain MC. Spinal 111Indium-DTPA CSF flow studies in leptomeningeal metastasis. J. Neurooncol. 1995;25:135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01057757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamberlain MC. Comparative spine imaging in leptomeningeal metastases. J. Neurooncol. 1995;23:233–238. doi: 10.1007/BF01059954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamberlain MC, Glantz M. Utility of CSF radioisotope flow studies in leptomeningeal metastases: a review. J. Nucl. Med. 2002;5(3):2101–2112. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamberlain MC, Sandy A, Press GA. Leptomeningeal metastasis: a comparison of gadolinium-enhanced MR and contrast-enhanced CT of the brain. Neurology. 1990;40:435–438. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.3_part_1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamberlain MC, Kormanik P. Leptomeningeal metastases due to melanoma: combined modality therapy. Int. J. Oncol. 1996;9(3):505–510. doi: 10.3892/ijo.9.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamberlain MC, Kormanik PA. Carcinomatous meningitis secondary to non-small cell lung cancer: combined modality therapy. Arch. Neurol. 1998;55:506–512. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chamberlain MC, Kormanik PA. Non-AIDS related lymphomatous meningitis: combined modality therapy. Neurology. 1997;49:1728–1731. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamberlain MC, Kormanik P, Glantz M. Recurrent primary central nervous system lymphoma complicated by lymphomatous meningitis. Oncol. Rep. 1998;5:521–523. doi: 10.3892/or.5.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chamberlain MC. Combined modality treatment of leptomeningeal gliomatosis. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:324–330. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000043929.31608.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamberlain M, Glantz MJ. Myelomatous meningitis: multimodal therapy. Cancer. 2008;112:1562–1567. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegal T. Leptomeningeal metastases: rationale for systemic chemotherapy or what is the role of intra-CF chemotherapy? J. Neurooncol. 1998;38(2–3):151–157. doi: 10.1023/a:1005999228846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamberlain MC, Kormanik P. Prognostic significance of 111Indium-DTPA CSF flow studies. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1674–1677. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]