Abstract

Introduction

Devolution reforms in Indonesia and Kenya have brought extensive changes to governance structures and mechanisms for financing and delivering healthcare. Community health approaches can contribute towards attaining many of devolution’s objectives, including community participation, responsiveness, accountability and improved equity. We set out to examine governance in two countries at different stages in the devolution journey: Indonesia at 15 years postdevolution and Kenya at 3 years.

Methods

We collected qualitative data across multiple levels of the health system in one district in Indonesia and ten counties in Kenya, through 80 interviews and six focus group discussions (FGD) in Indonesia and 269 interviews and 14 FGDs in Kenya. Qualitative data were digitally recorded, transcribed and coded before thematic framework analysis. Common themes between contexts were identified inductively and deductively, and similarities and differences critically analysed during an inter-country analysis workshop.

Results

Following devolution both Indonesia and Kenya experienced similar challenges ensuring good governance for health. Devolution reforms transformed power relationships, increasing responsibilities at subnational levels and introducing opportunities for citizen participation. In both contexts, the impact of these mechanisms has been undermined by insufficiently clear guidance; failure to address pre-existing negative contextual norms and practices varied decision-maker values, limited priority-setting capacity and limited genuine community accountability. As a consequence, priorities in both contexts are too often placed on curative rather than preventive health services.

Conclusion

We recommend consideration of increased intersectoral actions that address social determinants of health, challenge negative norms and practices and place emphasis on community-based primary health services.

Keywords: health systems, health policy

Key questions.

What is already known?

Decentralisation is a dynamic process; transfer of powers for decision making have governance implications.

Few studies have examined the implications of devolution for strengthening community governance and accountability.

What are the new findings?

Despite a 15-year difference in time frame, Indonesia and Kenya experience many similar governance challenges, which threaten the success of devolution reforms.

Limited technical capacity and community engagement, with weak accountability structures, can mean priorities may be distorted from attaining universal health coverage.

What do the new findings imply?

Well-supported and empowered community health workers are potentially key actors to promote genuine community engagement with decision-making processes following health reforms.

Introduction

Decentralisation is a dynamic process that transfers authorities or powers for decision making, planning and management of public services from national to subnational levels.1 Decentralisation reforms also have implications for governance, due to the reallocation of authority and resources, affecting internal power relationships and access of actors to the decision-making process and state resources.2 Reforms may be classified as four main types: deconcentration occurs when authority for administrative functions shifts to subnational offices within the Ministry of Health; delegation occurs when semiautonomous agencies are granted new powers (typically still administrative); devolution occurs when administrative, political and fiscal responsibilities shift to the subnational level of locally elected government and privatisation occurs when ownership is granted to private bodies.3 4

Governance is widely recognised as central to improving health sector performance and achieving universal health coverage (UHC).5 However, it is political, the result of interactions, coordination and decision-making among different actors in the face of multiple views and interests.6 7 In this paper, we define governance as being ‘a process whereby societies or organizations make their important decisions, determine whom they involve in the process and how they render account’ (p. 1).8 Decentralisation that enables responsiveness to local needs and values has been identified as a key governance mechanism for influencing health outcomes.9 Reforms, such as devolution bring expectations for improved service delivery, increased responsiveness to community demands, increased accountability and greater efficiency, equity and expansion of UHC.3 4 10–13 Yet, past experiences with devolution teach us it is a complex process, outcomes can be unpredictable and it may lead to widening disparities and mixed implications for accountability processes.13–15 There is need to think through the governance mechanisms and accountability implications of reforms, ensuring clear knowledge of roles, responsibilities and process within priority-setting, with strong capacity and accountability.11 13 16–21 This requires awareness of how political, social, economic and cultural context and norms, values held by actors and changing power balance create the ‘de facto’ decision space, which may differ from the ‘de jure’ decision space described in formal laws and regulations.19 22 23

Community health services have an important role to play in attaining UHC by involving and empowering communities to improve knowledge, change health-related beliefs, behaviours and improve access and uptake of health services.24 Empowerment of diverse stakeholders in decision making, community engagement and enhanced social capital, along with decentralisation, form the four main mechanisms for governance.9 Community health services could therefore be expected to form the backbone for health service provision and community engagement following devolution, given the overlap with the commonly identified objectives for devolution. The role of community health services following devolution reforms was a key emerging theme in recent community health context analyses conducted in both Kenya and Indonesia.25–27 In Kenya, a study carried out in the months surrounding the introduction of devolution’s reforms highlighted widespread recognition of the need for more holistic care at community level with support for incorporation of home-based testing and counselling for HIV within existing community health activities.28 Historically, however, subnational authorities have often emphasised investment in curative over preventive services after decentralisation reforms, with resultant neglect of public health in the Philippines and Indonesia.4 29 30

In both Indonesia and Kenya, administrative, political and fiscal responsibilities were transferred from central government to subnational authorities following the introduction of nationwide ‘big-bang’ devolution reforms (see table 1). With rapid, politically motivated decentralisation reforms of this nature, there are often initially increased discretionary powers at the new subnational levels, with accountability measures following later.13 Successful devolution depends on successful identification of priorities and strong governance principles applied at national, subnational and local levels. Governance may depend on guidance set at national level, but it is operationalised at lower levels and so analysis should recognise the importance of actors at lower health systems levels.7 9 We set out to examine governance across health systems levels with implications for community health services, identifying similarities and differences in two countries at different stages in the devolution journey for healthcare.

Table 1.

Comparison between Kenya and Indonesia35 37 44 46 57 59 66–74

| Indonesia | Kenya | |

| Context and informal practices, norms and structures | 255.18 million people, lower middle-income country. Gained independence in 1945. Former centralised government. Wide geographic, socioeconomic and disease burden disparities across the country (17 000 islands). Wide health service coverage and outcome disparities. International pressure to devolve. Little authority or autonomy prior to devolution. President desired a rapid reform and transfer of responsibilities to district level to avoid provincial level unrest (following previous violence at this level). |

46 million people, lower middle-income country. Gained independence in 1963. Former centralised government. Wide geographic, socioeconomic and disease burden disparities across the country (single land mass). Wide health service coverage and outcome disparities. International pressure to devolve. Former deconcentration of administrative functions. Rapid reforms and transfer of responsibilities to county level, following pressure from county level actors, although structures not yet established and capacity not in place to manage devolved functions at that time. |

| Content of formal devolution reforms |

Political

Started in 2001 with rapid roll out. Three-tier government (national, provincial and district). 32 provinces and 440 districts. |

Political

Started in 2013 with rapid roll out. Two-tier government (national and county). 47 counties. |

|

Fiscal

National level retain control of the greatest share of revenue. Funding at subnational levels from three possible sources:

|

Fiscal

Minimum of 15% of revenue is to be shared with counties. Funding at subnational county level from five possible sources:

|

|

|

Administrative (health).

Provincial level – coordinate functions among districts; draft policies that should then be implemented by all districts within the province; supervision of districts. District level – make decisions on priorities; deliver public goods and services, including health. |

Administrative (health).

County government holds responsibility for planning, management and budgeting. County level – make decisions on priorities by drafting county integrated development plan; annual planning and budgeting; service delivery for public health, disease surveillance, community health services, primary health services, ambulance, county hospital services; recruitment and human resource management (includes facility and community health workers); and partner coordination. |

Methodology

Methods and approach

We used qualitative methods as these allowed the inductive generation of rich data by seeking to understand the ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions about devolution and community health services within specific contexts.31 32 We selected Indonesia and Kenya from among the six countries involved in the REACHOUTi consortium’s work on the equity and effectiveness of community health workers because devolution had been highlighted as a contextual issue affecting community health worker programmes within these countries.25–27

Mixed qualitative methods including key informant interviews, in-depth interviews with close-to-communityii (CTC) providers and their supervisors and focus group discussions with community members were applied separately in each country. In Indonesia, questions probing governance and devolution were added within the topic guide used for studies conducted before and after a quality improvement intervention (studies carried out in 2014 and 2015). Meanwhile, in Kenya, a separate substudy was conducted to explore priority-setting for community health and equity following devolution (April 2015–April 2016), and these data were analysed along with data collected for the mixed methods REACHOUT quality improvement baseline (March–April 2015). The topic guides used in both countries included similar issues but different questions and probes. Other findings from the study carried out in Kenya, which explore the implications of changing priority-setting processes for community health and equity, have been published elsewhere.33

In Indonesia, all data were collected by Indonesian nationals working as part of the REACHOUT consortium in Bahasa Indonesia. Meanwhile, in Kenya national, county and some health worker level interviews were carried out by a foreign researcher (PhD student) in English language (RM). Community and some health facility level respondents in Kenya were interviewed by trained research assistants working with REACHOUT consortium in Kiswahili or Kamba (depending on respondents’ preference). All researchers were trained and experienced in using qualitative methods. None of the researchers had prior relationship with any of the research participants.

Country context

Both countries have histories of highly centralised and hierarchical government, which had created expectations of national accountability and had left a legacy of patronage and mismanagement of funds.34 35 At the time of the study, both Indonesia and Kenya were lower middle-income economies, with wide income inequalities and uneven access to health services between population groups36 37 (see box 1 and table 1).

Box 1. Country context.

Indonesia devolved administrative and operational functions to 32 provinces and 440 districts in 2001, with districts responsible for managerial and financial responsibilities for public health30 (see table 1). Indonesia has a three-tier devolved government with national, provincial and district authorities. In Indonesia, reforms were driven in response to economic crisis, the fall of the Suharto regime and strong international pressure.30 Indonesia’s devolution reforms aim to improve quality and reduce costs for public services, including health.30

Following the financial crisis in 1997, there has been an increasing transition towards privatisation contributing to reduced spending for preventive health alongside an increasing role for private insurance companies.44 Previous studies have reported that in the eagerness to reform following devolution, socioeconomic conditions (wide differences in the ability of districts to generate revenue and up to 50-fold variation in income per capita between districts) have been overlooked, with variation in ability to pay for services and hence in access to healthcare.30

Kenya has a shorter history with devolution, having adopted a two-tier devolved government (with national and county level authorities), transferring planning, management and budgeting responsibilities for a range of services, including health, from central government to 47 new subnational governments, (now known as counties) in 2013 (see table 1). Kenya’s reforms were driven by increasing frustration with inefficiencies and inequities associated with the former centralised government process and in response to growing local and international pressure following the postelection violence of 2007–2008.41 Devolution aims in Kenya seek to strengthen democracy and accountability, enhance national unity, increase community participation, improve efficiency and reduce inequities.59

Kenya’s central government have sought to address historic inequities through transfer of the equitable share funding from central government to county governments, determined by the commission for revenue allocation formula,66 which takes into account each county’s poverty level, along with the equalisation fund for formerly marginalised counties.59 Formerly marginalised counties now benefit from higher levels of funding, along with the decision space to invest in health. At the county level, there is no formal guidance to clarify how county budget should be allocated, as a result contextual factors, power dynamics and values play key roles in determining how the budget is allocated.

Site and respondent selection

Study sites were selected purposively. In Indonesia, selection was based on high maternal mortality (since this was the focal research area within REACHOUT study), and in Kenya, selection ensured representation of agrarian, pastoralist and urban with varied poverty levels and coverage with maternal health as well as other key health indicators (to provide diverse range of counties studied). In both contexts, participants were selected purposively, in order to identify those who could contribute valuable information (see table 2). More information about the repsondents interviewed in Kenya have been presented elsewhere (see table 4, McCollum et al).33 Respondents were contacted in advance by via telephone or introduction by a known contact, such as their supervisor or Community Health Worker (CHW). Interviews and discussions were carried out at a location convenient for the respondents, often at their place of work for health workers or at an easily accessible community meeting point. Topic guides were used to explore local politics, support from local government for community and/or maternal health, equity of health services and CTC service delivery across both countries. Interviews and FGDs typically lasted between 30 min and 90 min.

Table 2.

Respondent demographics in Indonesia

| QIC1 (baseline and endline) | Male | Female | # of respondents |

| District level semistructured interviews | |||

| Health system officer (MCH of DHO) | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total county-level health respondents | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Subdistrict-level semistructured interviews | |||

| Health system manager* | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Non-health system stakeholder | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| NGO | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total respondents | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Community health semistructured interviews | |||

| Community health volunteer (kader Posyandu) | 6 | 19 | 25 |

| Village midwife | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Head of village | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Mother | 0 | 29 | 29 |

| Total SSI respondents | 8 | 64 | 72 |

| Total participants | 11 | 69 | 80 |

| FGDs | |||

| Community health volunteer (kader Posyandu) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| TBA | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Men in the village | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Mother | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total FGD | 2 | 4 | 6 |

*The health system manager is the person with the highest authority at the subdistrict level. He or she is the head of the Puskesmas and is typically a physician or dentist, or someone with a public health background.

DHO, District Health Office; FGD, focus group discussion; TBA, traditional birth attendant; NGO, Non Governmental Organisation; MCH, Maternal Child Health; QIC1, Quality Improvement Cycle 1

Indonesia primary data

Semistructured interviews with 80 participants and 6 focus group respondents were conducted in one district in West Java Province (see table 2). Purposive sampling was used to identify respondents for in-depth interviews with health stakeholders (Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat (puskesmas) (community health centre) and District Health Office officials); non-health stakeholders (subdistrict and village officials); healthcare providers (village midwives, kaderiii and traditional birth attendants) and community members (including women who were pregnant in the past 2 years and men).

Kenya primary data

Interviews with 86 CTC providers and their supervisors and 14 focus group discussions with a further 146 community members were carried out in two counties as part of the REACHOUT quality improvement baseline study. A further 183 interviews were conducted as part of the substudy. These included 14 key informant interviews with national-level respondents and in-depth interviews with 120 county-level decision makers (technical, political, treasury, gender and children’s representatives) across 10 diverse counties. In three of these counties, data from interviews with 49 health workers (health facility and community level) were included.

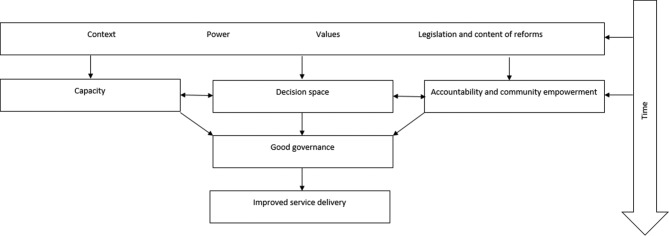

Data analysis

This paper will present findings from a secondary analysis of qualitative data from Indonesia and Kenya. It will provide an overview of similarities and differences between governance mechanisms since devolution and potential implications for community health. Data from both countries were digitally recorded, transcribed and coded using NVivo 10, before framework analysis was conducted. Common governance themes were identified both inductively and deductively, allowing meaning to emerge from the data32 through data familiarisation by reading and rereading narratives drafted from governance-related themes between REACHOUT data collected in both countries and the Kenyan substudy (see figure 1 which presents the common themes across both contexts and their inter-relationship). A data analysis workshop involving researchers from both contexts was held, during which thematic framework analysis was carried out with data compared across and between countries to search for similarities and differences in order to refine themes for further analysis. Emerging from this workshop, we identified three main themes: contextual norms, politics and power dynamics; the influence of power, leadership capacity and values on priority-setting and decision making; and community accountability and empowerment.

Figure 1.

Common themes from Indonesia and Kenya.

Quality assurance and ethics

Discussions and interviews conducted in Bahasa Indonesia, Kiswahili or Kikamba were translated to English, with a selection (approximately 10%) back-translated for quality checking. Data collection continued until saturation was reached, and data were triangulated between sources to minimise bias. All respondents gave written informed consent, which highlighted the main study objectives. All study findings, including quotations, have been appropriately anonymised, and data collected through this study was safely stored in a password-protected laptop to ensure confidentiality. This study fulfils COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research criteria for qualitative research.38

Results and discussion

Indonesia and Kenya experience many similar challenges to good governance and to attaining improved service delivery, despite differing timeframes with implementing devolution reforms. In both countries, good governance has been hindered to varying degrees, through failure to adequately consider the accountability implications of reforms in light of prior contextual norms, such as patronage; varied values held by decision-making actors, such as the value of visible and politically popular infrastructure over ‘invisible’ community health services; limited capacity for health priority-setting by key decision makers, including politicians and technical actors at the time of introduction of reforms; and limited genuine community empowerment and engagement in accountability for decision-making (see figure 1). We combine our results and discussion, in order to both present and analyse our results, in light of differing devolution timeframes—immediately following introduction of reforms in Kenya and 15 years later in Indonesia, and situate our analyses within the literature on devolution, including the literature about Indonesia’s early experiences.

Contextual norms, politics and power dynamics

Structural forces resulting from colonialism have contributed to wide inequities between regions in both Indonesia and Kenya, yet the policy response to these inequities varied widely (see box 1). Prior to the introduction of devolution reforms, both countries were governed by strong centralised governments, where patronage norms and nepotism were commonplace.34 35 Our findings reveal that in both Indonesia and Kenya, these have continued since devolution, creating a threat to governance mechanisms. We found that nepotism was widely described by almost all respondents in Indonesia, indicating its continuation over time and its embedment since devolution. In Kenya, nepotism was also described, although to a much lesser extent than in Indonesia, highlighting potential opportunity for change. Politicians are often motivated to provide services that will appeal to their electorate, consolidate political support and maximise their voter base in their pursuit of re-election.39 In both countries, the provision of health (and other services) was already politically motivated prior to devolution.40 41 This continued politicisation has in some instances brought positive results towards improving access to health services, with UHC recognised as an ‘electoral asset’ in Indonesia, with popular health schemes felt to contribute towards electoral success.40 Similarly, our findings from Kenya highlight that several years into devolution, some politicians are beginning to appreciate the potential political benefits associated with expanding community health services.

It’s (primary/community health care) also good politically because you have created employment, you have encouraged someone so they show their appreciation where elections come. So politically it’s a bonus. Kenya non-health respondent, male 32

Unfortunately, rather than proving to be the norm, these positive examples appear to have been exceptions. We found that patronage continues to influence the provision of health services since devolution in both Indonesia and Kenya, contributing to varied levels of service provision within a subnational district or county. In Indonesia, a few respondents including health officials, village heads and kaders felt that the level of development within their village varied widely according to whether the community had supported the elected leader in the previous election or not. This is in keeping with previous findings that local governments were perceived to distribute funds unevenly in favour of subdistricts with a high electoral support rate, in order to consolidate power.42 Similarly in Kenya, we found resources were commonly described by community and county technical actors, as having been channelled to the home area for the governor (elected leader in the county) or another powerful politician, with development investment at times provided according to political affiliation, rather than need. As the World Development Report (2004) identifies, poor citizens often have limited influence with politicians about public services. They may be poorly informed about services and may vote along ethnic lines, leaving the provision of public services susceptible to political patronage, with clinics built-in areas where supporters live.17

For example, the current regent, when we asked for support from him, he preferred to give support (financial assistance) to the areas where he got many votes from the previous election. Indonesia village health official, male 04

In a democracy, political parties tend to move towards the position of the median voter in order to secure (re)election, regardless of the efficiency or equity implications of those decisions.39 This is likely to lead to the neglect and further marginalisation of smaller population groups such as people living in hard-to-reach or sparsely populated nomadic areas, while resources are focused on heavily populated areas where there are a lot of votes.43 Within Indonesia, where experiences with devolution are longer, there has been a reported deterioration in public health services, with reduced access among poorer populations.30 44 The picture within Kenya so far appears mixed, with national government having introduced policy for free maternity services around the same time as devolution reforms were introduced, leading to increased utilisation of services.45 However, success of this policy has been complicated by uncertainty created by devolution and poor planning, with health facilities having been inadequately compensated for lost fees, leading health workers to raise revenue from patients, with implications for the most poor.45 Additionally, in Kenya, we found that politicians frequently gave preference to priorities deemed as popular with the electorate, such as construction of new health facilities or purchase of ambulances.33 These were frequently referred to as ‘high vote’ priorities, meanwhile health promotion or disease prevention activities were not viewed as politically favourable. Now is an opportune time for Kenya to reflect on lessons learnt from other countries with longer experiences with devolution, such as Indonesia, in order to ensure that priorities reflect those that will promote public health, as well as curative services, which are often more politically appealing. The recent identification, as UHC as one of the four central pillars for the new government, provides encouraging evidence for this.

The decisions might be subjected to a lot of political interference… They (politicians) make decisions based on votes, will this get me more votes? So they do not tend to see that when we prevent malaria or prevent diarrhoea that you are going to get votes. Kenya county health respondent, male 02

The influence of power, leadership capacity and values on priority-setting and decision making

In both Indonesia and Kenya, in the absence of a clear process and adequate capacity for determining guiding values and priorities, changing power dynamics following devolution became more important, with priorities being selected in line with the degree of ‘power over’ the decision-making process and values held by key decision-making actors. Capacity for setting priorities was widely discussed within Kenya, although it was less commonly described in Indonesia. This may have been as a consequence of the differing timeframes since the introduction of devolution reforms, since earlier study in Indonesia highlighted inequities in capacity between regions.46 A recent study in Kenya highlighted the vital importance of strong leadership capacity following reforms, providing examples of subcounty level managers having innovated and demonstrated flexibility to ensure essential services continue, despite uncertainty during the period immediately following devolution.47 Capacity of local officials has widely been acknowledged as critical to the success of devolution reforms.19 48–50 In Kenya, we observed differences in the levels of capacity for key decision makers between counties.33 Here the key leaders for health are the county executive committee member for health and the chief officer for health who may or may not have public health (or even health) or budgeting experience. Capacity also varied among other actors involved with decision making, including community members and local politicians to understand health comprehensively (including preventive, promotive, rehabilitative and curative services) and their role for setting health priorities. This limited capacity was felt by national-level respondents to impede wise priority-setting.

… the capacity is not there, their priority is wrong sometimes and so decision-making sometimes gets messed up; we are ending up with decisions that will not necessarily address the health issues that we have. Kenya national respondent, female 12

Across both countries, there was wide variation at subnational level in the values held by actors involved with planning and budgeting for health services. The process of priority-setting is inherently complex and value laden.51 As a result of differing values between actors, gaining a common consensus can be problematic,51 and the process for identifying priorities should therefore involve decisions about which values or principles should dominate.23 In literature from Indonesia, differing values contribute to varied priorities. At times, this was felt to cause leaders to prioritise development programmes deemed most profitable to them, which often led to neglect of health and social development programmes.52 From our study findings in Indonesia, respondents described that the priority-setting values of the subnational leaders in the study location did not lead to prioritisation of maternal and child health, which was felt to lead to limited allocation of funding, compared with other priorities. This contrasted with another area that had similarly high maternal mortality rates but had prioritised maternal health in local policy and budget allocation. These findings are in keeping with previous study in Indonesia.53

I know the government would do budget reducing, but they did too much especially in the budget for health sector… The government doesn’t care about the number of maternal and infant deaths. It looks like they just think that the maternal and infant death is a destiny. Indonesia village midwife, female 15

In Kenya, there was no clear guidance surrounding the role of values in priority-setting. Values varied considerably between counties and between actors within a single county, leading to differing health priorities during health planning and budgeting. Politicians tended to prioritise the need for an accountable rights-based approach, typically emphasising the importance of the public participation meetings to validate priorities directly with community members, while technical actors tended to emphasise the need for effective, efficient and equitable priorities.33

In both Indonesia and Kenya, there were positive examples of priority-setting that have prioritised provision of quality, responsive health services. In Indonesia, published examples of positive deviant cases highlight innovation by district leaders to deliver services responsive to local needs, or which seek to improve both the quality and quantity of services provided.40 54 Meanwhile, in Kenya, selected counties are placing high value on community health services, leading to allocation of county government funding, with one positive deviant county having sought to educate and empower actors across all levels (including community, political and technical actors) to understand health holistically and to actively participate in priority-setting.33 This was felt to have contributed to community identification of community health services as a priority for inclusion within the county health plan and budget. The varied duration of devolution reforms allows us to identify lessons, such as the need for rigorous evaluation and learning between well-performing and poorly performing districts, which was felt to have been a missed opportunity in Indonesia.40 In Kenya, forums such as the county executive committee forum (a platform for county executive committee members from all counties to meet together) provide scope for informal sharing of best practices and has provided an opportunity for county executive committee members with an interest in community health approaches to promote awareness with their counterparts around community health and other critical health issues.

Community accountability and empowerment

Within Indonesia and Kenya, we found that limited actions have been introduced since devolution to promote citizens’ understanding of health or their decision-making role. Across both Indonesia and Kenya, we found a host of barriers to effective citizen participation. While avenues for citizen participation are described in policy for both countries, in practice, a lack of funding and tokenistic implementation hinder opportunity for genuine involvement of the community in identifying priorities. These findings are in keeping with previous studies in Kenya and in other devolved countries, including Tanzania and Philippines, where genuine community participation in health planning at the health facility level was limited.55–57

In Indonesia, community participation is described in policy through Musyawarah Perencanaan dan Pembangunan, also known as musrengbang. These are multisectoral annual community consultative meetings for planning and development, involving community members, local community and religious leaders and representatives of local organisations. However, these meetings are not implemented as intended in many regions.42 Musrengbang are often only partially effective, as power is still retained by the village elite,58 with limited community knowledge or interest to participate.44 Within our study, the community role in priority-setting was not commonly discussed by respondents in Indonesia. Instead respondents viewed community participation as the responsibility of the kader (who attended monthly village women’s meetings) or the puskesmas, rather than the community themselves. At times, this resulted in the village midwife (who represents the puskesmas) being blamed by the village head for health issues occurring within the catchment community.

If the puskesmas staff gave them all information about the jamkesda (District health Insurance) or Jamkesmas (Community health insurance), the village people would not have the wrong perception about that. Indonesia head of village, male 06

In Kenya, a similar finding emerged in terms of the role for the community in priority-setting described in policy, compared with the meaningfulness of their role in practice. Pre-existing avenues for citizen participation in accountability and decision making include community and health facility management committees that continue with relatively unchanged roles and responsibilities postdevolution. New avenues for engagement of citizens with state actors have been introduced since devolution through public participation fora, whereby county authorities are responsible to facilitate public participation and involvement.59 Barriers to effective citizen participation highlighted through our study include: failure to address barriers to attendance and active participation of hard-to-reach and marginalised groups, such as lack of funding for transport for those in remote areas, dominance of discussion by local ‘elites’, advertisement of meetings at short notice in English language newspapers and a failure to address local patriarchal norms that limit women’s and youth’s active participation in the presence of men/elders. Respondents described that the setting of priorities was often strongly influenced by power plays and local politics, in keeping with previous findings that acknowledged the influence of social hierarchies, social, cultural and religious norms, economic and political divisions and power asymmetries on participation in health facility management committees.60 61 Many of these barriers to citizen participation in selecting priorities have previously been described in Indonesia.42

Illiterate ones are never involved. They will not even know some of these processes [public participation]. Kenya county non-health respondent, male 19

Community health workers, positioned at the interface between the community and the health system, are potentially key actors to promote community empowerment and engagement with the decision-making process as culturally and socially embedded members of their community.62 63 First, however, they themselves must be empowered, since they live, work and experience the same social norms and discriminations as the citizens within their community.64 They will need the support of both their community and the health system in order to perform this unique role.65

Limitations

We used qualitative methods with a selected population making our findings difficult to generalise, quantify and rank in importance; instead our findings provide in-depth insights to the perspectives and experiences of stakeholders at different levels of the health system. There were a number of methodological challenges within our study that we carefully considered during the joint comparative analytical process. First, within Kenya, priority-setting was viewed from a range of respondent perceptions, with a strong emphasis on the subnational county level. Meanwhile in Indonesia respondent perceptions were primarily sought from community and CTC provider levels. Second, the study was carried out within one district in Indonesia, which was purposively selected for its poor maternal health indicators. By contrast, in Kenya, 10 counties were selected purposively to reflect a range of health indicators. Third, the topic guides used in each country were different, although they did explore similar issues. Fourthly, the devolution processes were carried out over different time periods: with Kenya in the immediate period postdevolution, while Indonesia is 15 years postdevolution. This brought challenges to the direct comparative analysis and also enabled us to review the impact of devolution from longer and shorter term analytical lenses. Despite these limitations and differences, what is interesting is the strong commonality between contexts and respondents across both countries.

Conclusions

Devolution reforms in Indonesia and Kenya have transformed power relationships, increasing political, fiscal and administrative responsibilities at subnational levels and introducing opportunities for citizen participation for health system governance. These reforms have created a series of opportunities for health, and we found examples of positive actions to prioritise maternal health in both contexts. Since devolution, governance mechanisms have implications for delivery of community health services, due to capture and distortion of the priority-setting process for political and power interests, leading to an emphasis on tangible curative services over less visible health promotion and disease prevention services.

Analyses across different health systems contexts generate new insights: comparing priority-setting for community health across both countries, at differing points in their journey with devolution, providing opportunity for Kenya to learn from Indonesia’s longer experience with devolution. In Indonesia, we have observed practices and norms that have become entrenched within priority-setting processes, such as failure to adequately address pre-existing negative contextual norms and informal practices such as patronage, manipulation of power by local leaders to direct priorities favourable to them and their voters, varied capacity and values contributing to varied priorities between districts, limited actions to translate policy around community participation into meaningful citizen engagement within decision making. Meanwhile, in Kenya we heard examples of many of these same issues, not yet entrenched but on track to become so unless soon challenged.

Our findings, which highlight the implications of devolution over a longer timeframe from the Indonesia data, combined with the experiences and early findings emerging within Kenya, present timely lessons for consideration within Kenya. First, we find that failure to address negative contextual norms and practices, such as patronage or nepotism, leads to their embedment and continuation at subnational levels, potentially leading to diversion of funds and priorities to more ‘politically influential’ individuals and groups, with neglect of historically marginalised groups. Second, devolution brings with it increasing local power and political influence. Unless the need for and benefit of public health services is understood by community members and politicians, this is likely to lead to continued preference for curative services and neglect of public health interventions, impeding progress towards UHC. Finally, there is the need to establish mechanisms for research and learning early in the devolution process to ensure that challenges identified are addressed, with best practices shared across counties. These recommendations present Kenya with ample opportunity and scope for evolution of Kenya’s devolved priority-setting processes towards achieving objectives for improved equity.

By identifying commonalities and differences between Indonesia and Kenya, including the differences in experiences as a result of the differing timeframes with devolution, our findings have potential to provide learning for other countries planning or implementing devolution reforms. We recommend practical strategies and their implementation to encourage meaningful citizen participation, actual intersectoral collaboration at subnational levels across departments to address the underlying determinants of health and clear monitoring and feedback mechanism that challenge the negative norms and practices.

Footnotes

REACHOUT is an ambitious 5 year international research consortium aiming to generate knowledge to strengthen the performance of CHWs and other close-to-community (CTC) providers in promotional, preventive and curative primary health services in six low- and middle-income countries in rural and urban areas in Africa and Asia, including Indonesia and Kenya. http://www.reachoutconsortium.org/

Close-to- community providers, are health workers forming the first point of contact at community level, having up to 3 years para- professional training, so this group includes auxiliary staff and CHWs.75

Kader is a community health volunteer who carries out primarily maternal and child health services, including family planning at village level.

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: The idea for the study and its design was conceived by all authors. Data coding and preliminary analysis was carried out by RM and RL, with review and discussion with all authors. RM prepared the initial draft of this paper. All authors reviewed the draft manuscript and provided input to preparation of and approval for the final version of the report.

Funding: European Union Seventh Framework Programme ([FP7/2007-2013] [FP7/2007-2011]) under grant agreement number 306090 and was conducted in collaboration with the REACHOUT consortium. REACHOUT is an ambitious 5-year international research consor- tium aiming to generate knowledge to strengthen the performance of CHWs and other close-to-community providers in promotional, preventive and curative primary health services in low- and middle- income countries in rural and urban areas in Africa and Asia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was received from Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Research Protocol 14.007 and Research Protocol 14.044) and in-country ethics from Kenya Medical Research Institute (Non-SSC Protocol 469) and Hasanuddin University, South Sulawesi, Indonesia (No. 02260/H4.8.4.5.31/PP36-KOMETIK/2014).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: PhD thesis for the data collected in Kenya is available online.

References

- 1.Mills A, Vaughan JP, Smith DL, et al. Health system decentralization: concepts, issues and country experience: World Health Organisation, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins C, Green A. Decentralization and primary health care: some negative implications in developing countries. Int J Health Serv 1994;24:459–75. 10.2190/G1XJ-PX06-1LVD-2FXQ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bossert TJ, Beauvais JC. Decentralization of health systems in Ghana, Zambia, Uganda and the Philippines: a comparative analysis of decision space. Health Policy Plan 2002;17:14–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell A, Bossert TJ. Decentralisation, Governance and Health-System Performance: ‘Where You Stand Depends on Where You Sit’. Dev Policy Rev 2010;28:669–91. 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00504.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fryatt R, Bennett S, Soucat A. Health sector governance: should we be investing more? BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000343 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chhotray V, Stoker G. Governance theory and practice. Oxford: Oxford Handbook of Governance, 2009:214–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pyone T, Smith H, van den Broek N. Frameworks to assess health systems governance: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:710–22. 10.1093/heapol/czx007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham BJ, Amos B, Plumptre T, 2003. Principles for Good Governance in the 21st Century: policy. 15:8 http://iog.ca/sites/iog/files/policybrief15_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciccone DK, Vian T, Maurer L, et al. Linking governance mechanisms to health outcomes: a review of the literature in low- and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med 2014;117:86–95. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossert T. Analysing the decentralisation of health systems in developing countries: decision space, innovation and performance. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:147–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheema SG, a RD. From government decentralization to decentralized governance : Decentralizing governance emerging concepts and practices. Cambridge, MA: The Brookings Intitution Press, 2007:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faguet J-P, Pöschl C. Is decentralization good for development? Perspectives from academics and policy makers : Press OU, Is decentralization good for development? Perspectives from academics and policy makers. Oxford, 2014:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yilmaz S, Beris Y, Serrano-Berthet R. Local government discretion and accountability: a diagnostic framework for local Governance. Social development working papers. Washington, DC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton K, Kaiser K, Smoke P. The political economy of decentralization reforms - implications for aid effectiveness. Washington DC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prud’homme R. The dangers of decentralisation. 10: World Bank Obs, 1995:201–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinkerhoff DW, Bossert TJ, 2008. Health Governance: concepts, experience, and programming options: health systems 20/20. http://www.healthsystems2020.org/content/resource/detail/1914/

- 17.World Bank. World Development Report 2004: making services work for poor people. Washington, DC: Banque mondiale, 2004:1–271. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleary SM, Molyneux S, Gilson L. Resources, attitudes and culture: an understanding of the factors that influence the functioning of accountability mechanisms in primary health care settings. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:320 10.1186/1472-6963-13-320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bossert TJ, Mitchell AD. Health sector decentralization and local decision-making: Decision space, institutional capacities and accountability in Pakistan. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:39–48. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khaleghian P. Decentralization and public services: the case of immunization. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:163–83. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyanjom O. Devolution in Kenya’ s new constitution devolution in Kenya’ s new Constitution. Society for international development working paper number 4. Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson D, Leftwich A. From political economy to political analysis. Birmingham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibbald SL, Singer PA, Upshur R, et al. Priority setting: what constitutes success? A conceptual framework for successful priority setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:43 10.1186/1472-6963-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet 2007;369:2121–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60325-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCollum R, Otiso L, Mireku M, et al. Exploring perceptions of community health policy in Kenya and identifying implications for policy change. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:10–20. 10.1093/heapol/czv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mireku M, Kiruki M, Mccollum R, et al. Context analysis: close to community health service providers in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasir S, Ahmed R, Kurniasari M, et al. Context analysis: close-to-community maternal health providers in Southwest Sumba and Cianjur, Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otiso L, McCollum R, Mireku M, et al. Decentralising and integrating HIV services in community-based health systems: a qualitative study of perceptions at macro, meso and micro levels of the health system. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:1–10. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakshminarayanan R. Decentralisation and its implications for reproductive health: the Philippines experience. Reprod Health Matters 2003;11:96–107. 10.1016/S0968-8080(03)02168-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kristiansen S, Santoso P. Surviving decentralisation? Impacts of regional autonomy on health service provision in Indonesia. Health Policy 2006;77:247–59. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:42–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuper A, Reeves S, Levinson W. An introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ 2008;337:404–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCollum R, Theobald S, Otiso L, et al. Priority setting for health in the context of devolution in Kenya: implications for health equity and community-based primary care. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:1–14. 10.1093/heapol/czy043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blunt P, Turner M, Lindroth H. Patronage’s progress in Post-Soeharto Indonesia. Public Adm Dev 2012;32:64–81. 10.1002/pad.617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Arcy M, Cornell A. Devolution and corruption in Kenya: everyone’s turn to eat? Afr Aff 2016;115:246–73. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, ICF Macro. Kenya demographic and health survey. Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik [BPS]), National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN), Indonesia Ministry of Health (Depkes RI), ICF International. Indonesia demographic and health survey 2012. Jakarta, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criterio for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32- item checklist for interviews and focus group. Int J Qual Heal Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goddard M, Hauck K, Smith PC. Priority setting in health - a political economy perspective. Health Econ Policy Law 2006;1(Pt 1):79–90. 10.1017/S1744133105001040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pisani E, Kok MO, Nugroho K. Indonesia’ s road to universal health coverage : a political journey. Heal Policy &Planning Adv Access 2016:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornell A, D’Arcy M. Plus ça change ? County-level politics in Kenya after devolution. J East African Stud 2014;8:173–91. 10.1080/17531055.2013.869073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonschorek G-J, Hornbacher-Schönleber S, Well M. Perception of Indonesia’s Decentralization - The role of performance based grants and participatory in planning public health service delivery. 2014.

- 43.Overseas Development Institute. Leaving no one behind in the health sector: an SDG stocktake in Kenya and Nepal. London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halabi SF. Participation and the right to health: lessons from Indonesia. Health Hum Rights 2009;11:49–59. 10.2307/40285217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pyone T, Smith H, van den Broek N. Implementation of the free maternity services policy and its implications for health system governance in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000249 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darmawan RE. The practices of decentralization in Indonesia and its implication on local competitiveness. Enschede, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilson L, Barasa E, Nxumalo N, et al. Everyday resilience in district health systems: emerging insights from the front lines in Kenya and South Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000224 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frumence G, Nyamhanga T, Mwangu M, et al. Challenges to the implementation of health sector decentralization in Tanzania: experiences from Kongwa district council. Glob Health Action 2013;6:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langran IV. Decentralization, democratization, and health: the Philippine experiment. J Asian Afr Stud 2011;46:361–74. 10.1177/0021909611399730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bossert T, Beauvais J, Bowser D. Decentralization of health systems : preliminary review of four country case studies. Major Appl Res 2000;6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barasa EW, Molyneux S, English M, et al. Setting healthcare priorities at the macro and meso levels: a framework for evaluation. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015;4:719–32. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Utomo B, Sucahya PK, Utami FR. Priorities and realities: addressing the rich-poor gaps in health status and service access in Indonesia. Int J Equity Health 2011;10:47 10.1186/1475-9276-10-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pardosi JF, Parr N, Muhidin S. Local Government and community leaders’ perspectives on child health and mortality and inequity issues in Rural Eastern Indonesia. J Biosoc Sci 2017;49:123–46. 10.1017/S0021932016000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heywood P, Choi Y. Health system performance at the district level in Indonesia after decentralization. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2010;10:1–12. 10.1186/1472-698X-10-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kilewo EG, Frumence G. Factors that hinder community participation in developing and implementing comprehensive council health plans in Manyoni District, Tanzania. Glob Health Action 2015;8:26461 10.3402/gha.v8.26461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramiro LS, Castillo FA, Tan-Torres T, et al. Community participation in local health boards in a decentralized setting: cases from the Philippines. Health Policy Plan 2001;16(Suppl 2):61–9. 10.1093/heapol/16.suppl_2.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsofa B, Molyneux S, Gilson L, et al. How does decentralisation affect health sector planning and financial management? a case study of early effects of devolution in Kilifi County, Kenya. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:151 10.1186/s12939-017-0649-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mantrawan IPW, Noak PA, Erviantono T. Peran Elit Desa dalam Partisipasi di Tingkat Lokal dalam Perumusan Musrembang di Desa Blahbatuh Kabupaten Gianyar. Bali, Indonesia, 2016:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 59.National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General. The constitution of Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCoy DC, Hall JA, Ridge M. A systematic review of the literature for evidence on health facility committees in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:449–66. 10.1093/heapol/czr077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abimbola S, Molemodile SK, Okonkwo OA, et al. The government cannot do it all alone: realist analysis of the minutes of community health committee meetings in Nigeria. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:332–45. 10.1093/heapol/czv066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S, et al. How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1–16. 10.1186/s12889-016-3043-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kok MC, Broerse JEW, Theobald S, et al. Performance of community health workers: situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Hum Resour Health 2017;15:1–7. 10.1186/s12960-017-0234-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kane S, Kok M, Ormel H, et al. Limits and opportunities to community health worker empowerment: A multi-country comparative study. Soc Sci Med 2016;164:27–34. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kok MC, Ormel H, Broerse JEW, et al. Optimising the benefits of community health workers' unique position between communities and the health sector: A comparative analysis of factors shaping relationships in four countries. Glob Public Health 2017;12:1–29. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1174722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Commission on revenue allocation. Brief on the second basis for equitable sharing of revenue among the county Governments: Commission on revenue allocation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lakin J, Kinuthia J. Budget brief 18b fair play: inequality across kenya’s counties and what it means for revenue sharing. 2013.

- 68.Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia, 1999. Indonesia G of. Law No 22/1999 on Local Government (Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia No 22 Tahun 1999 Tentang Pemerintahan Daerah). http://www.dpr.go.id/dokjdih/document/uu/UU_1999_22.pdf

- 69.Government of Indonesia, 1999. Law No 25/1999 on Balance of Financial Authority Between Central and Local Government (Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Tentang Perimbangan Keuangan antara Pemerintah Pusat dan Daerah). http://www.dpr.go.id/dokjdih/document/uu/UU_1999_25.pdf

- 70.Presiden republik indonesia. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 32 Tahun 2004. Indonesia, 2004:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Green K. Decentralization and good governance: the case of Indonesia: Munich Personal RePEc Archive, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook: Kenya. 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ke.html (cited 1 Jun 2016).

- 73.Nyikuri M, Tsofa B, Barasa E, et al. Crises and resilience at the frontline-public health facility managers under devolution in a sub-county on the kenyan coast. PLoS One 2015;10:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nasution A. Government decentralization program in Indonesia: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, et al. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:1–21. 10.1093/heapol/czu126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]