Abstract

Lymphatic filariasis is caused by nematode filariae Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori. It is commonly seen in tropical and subtropical regions of the world and affects the lymphatic system of humans, who are the definitive host while mosquito is the intermediate host. The most common manifestation of the disease is hydrocele followed by lower limb lymphoedema and elephantiasis. Although filariasis is much more common entity in north India, its presentation as retroperitoneal cyst is very rare with reported incidence rate of 1/105 000. We present a case of primary retroperitoneal filariasis in a 52-year-old man, without any classic signsandsymptoms, diagnosed postoperatively after surgical resection following diagnostic uncertaintyandfailure of other medical therapies.

Keywords: tropical medicine (infectious disease), general surgery

Background

Filariasis is a common disease in a country like India. Despite the high incidence rate, it is not one of the differential diagnosis that comes to mind when dealing with a retroperitoneal cyst. After retrospective analysis of the current case as well as other cases reported, we found a common theme of diagnostic uncertainty and clinical presentation. Thus, reaching the conclusion that despite common diagnoses of any clinical presentation, it is important that we keep in mind the common infectious aetiologies affecting the tropics as a differential diagnosis, especially when there is a history of failure of other ‘conventional’ treatments.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old man hailing from rural North India presented to the surgery outpatient department with dull and constant abdominal pain, predominantly in the epigastric region, for the past 6 months. There was a history of intermittent low-grade fever and headache of recent onset. There was no history of jaundice, heartburn, vomiting, constipation or similar episodes. He consumed alcohol socially, limited to maximum three drinks. There was no history of cigarette smoking or substance abuse. Family history was negative for liver disease. He used over-the-counter analgesics and antacids, which failed to bring any improvement. He was prescribed a proton pump inhibitor, which also failed to improve his condition. There was no history of surgical intervention.

On local examination, there was a vague tender mass palpable, predominantly in the right lumbar region. Liver span and texture was normal. Bowel sounds were present. Rest of the systemic examination was within normal limits. There was no evidence of limb oedema, hydrocele or scrotal tenderness.

Complete blood count revealed marginally raised neutrophil and lymphocyte counts and normal eosinophils. Liver function tests, kidney function tests and serum electrolytes (including calcium) were within normal limits. Serum amylase and lipase were normal. Urinalysis was normal.

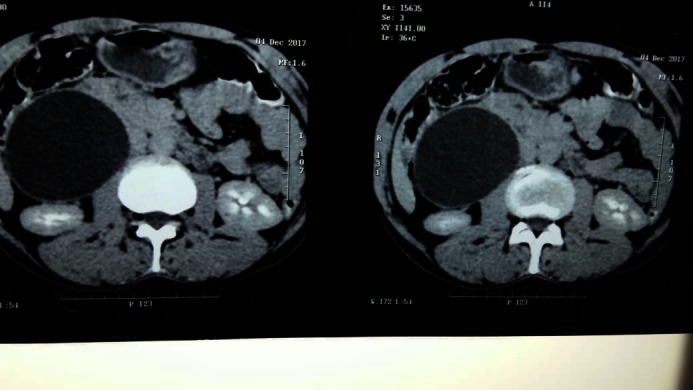

Abdominal ultrasonography (USG) revealed a 9×8 cm cystic structure with coarse internal echoes and small septations in subhepatic region abutting anterior surface of right kidney posteriorly, inferior vena cava (IVC) medially and pancreatic head anteromedially. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen confirmed presence of well-defined retroperitoneal cystic structure. However, the origin could not be defined as there was clear well-defined plane between the cyst and the surrounding structures (figure 1). The differential diagnosis of pancreatic pseudocyst was rejected due to normal appearance of pancreas on CECT and normal serum chemistry.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography abdomen showing well-defined retroperitoneal cyst compressing duodenum and inferior vena cava.

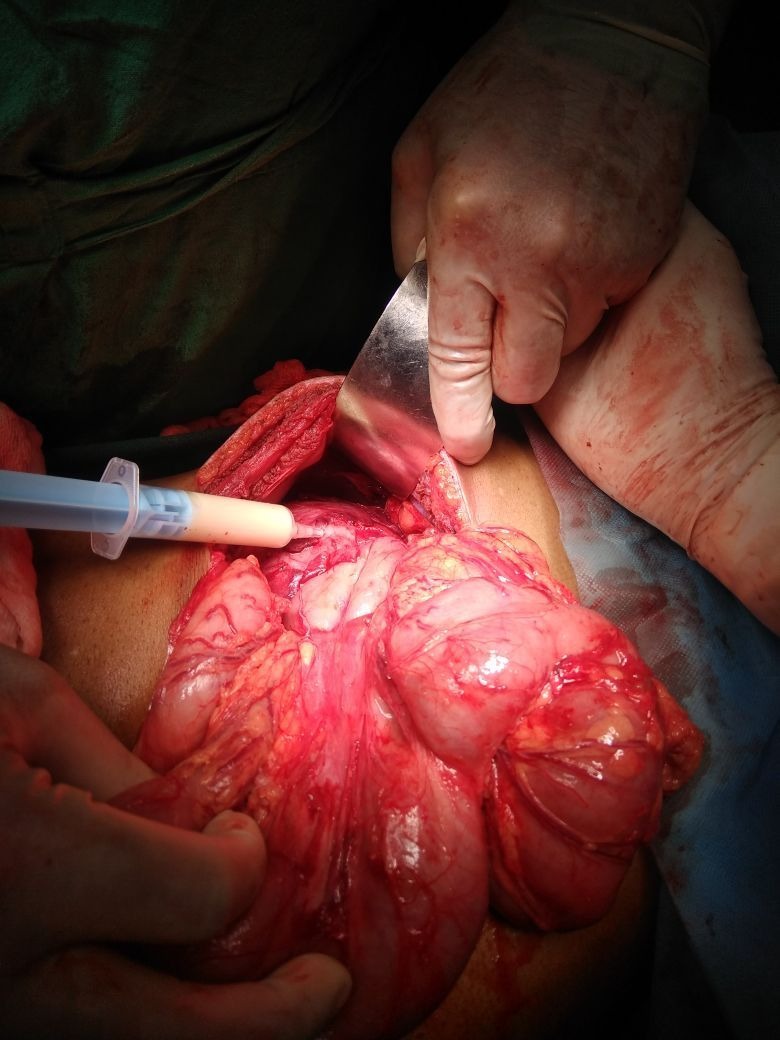

As the patient had already received various non-surgical modalities of treatment without any benefit, decision to perform a surgical resection was taken, after obtaining informed consent from the patient. Surgical exploration was done with right subcostal incision. Kocherisation was done which revealed cyst with thickened walls in the subhepatic region abutting second part of duodenum and IVC. Rest of bowel was normal. Right kidney and ureter were normal. Cyst cavity was aspirated, and pale yellow fluid (figure 2) was obtained and sent for cytology. Cyst wall was excised while taking precaution to avoid spillage of fluid. A small part of the cyst wall was densely adhered to the duodenum and was left as such. Postoperative period was uneventful.

Figure 2.

Cystic fluid aspirate showing pale yellow fluid.

Cytology of the cystic fluid revealed numerous Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae. Culture of the fluid was negative for other infectious agents. Histopathology of the cyst showed inflammatory cell infiltration in the fibrous wall and septa along with presence of few microfilariae. After establishing the diagnosis, the patient was asked for any history of scrotal oedema or pain and he denied any such event. Duplex scan of the scrotum, groin and lower extremity was done to exclude other possible foci of infection and was negative, confirming the diagnosis of primary retroperitoneal filariasis. Blood was drawn nocturnally to reveal the presence of microfilariae in the smear (figure 3). Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) was started following the diagnosis. He recovered successfully and remains disease free with clear USG at 6 months of follow-up.

Figure 3.

Blood smear showing microfilaria of Wuchereria bancrofti.

Differential diagnosis

Retroperitoneal cyst of adrenal origin.

Pancreatic pseudocyst.

Treatment

Surgical excision followed by DEC.

Outcome and follow-up

He recovered successfully and remains disease free with clear USG at 6 months of follow-up.

Discussion

Filariasis is a mosquitoborne disease, commonly seen in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Both sexes are equally affected. W. bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori infect the lymphatic system of humans, who are the definitive host. Following filarial infection, there generates an inflammatory immune response that results in lymphatic obstruction.1 The most common manifestation of the disease is hydrocele followed by lower limb lymphoedema and elephantiasis.2 Although filariasis is much more common entity in north India, its presentation as retroperitoneal cyst is very rare with a reported incidence rate of 1/105 000.3 4

Filariasis presenting as retroperitoneal mass is rare, even in regions where it is endemic. The exact pathogenesis of the lesion remains speculative. Obstructed lymphatic vessels, rupture of lymphatics causing extravasation of chyle and the presence of ectopic lymphatic tissue have been propounded as the possible aetiologies.5 The literature of retroperitoneal filariasis is limited to few case reports1 5–9 with a similar theme of diagnostic uncertainty with clinical presentation as dull abdominal pain with/without accompanying symptoms such as haematuria5 or groin pain7 due to pressure effect. Clinical examination alone is seldom helpful in the evaluation of this abdominal mass, apart from its ability to localise the lesion in some cases,8 especially in absence of classic signs and symptoms, like in our patient. However, presence of a thickened spermatic cord or prior history of scrotal oedema are subtle clues present in many cases.1 6 8 This finding was not present in our case.

Diagnostic imaging helps to localise a well-defined retroperitoneal cyst and rule out other possible diagnosis such as pancreatic pseudocyst, urogenital cysts and so on. Subclinical dilation of scrotal lymphatics, with extension into dilated retroperitoneal lymphatic channels, has been identified in some cases.1 Scrotal collection, if any, reveal the classic filarial dance sign on USG and Doppler.1 7 In our case, imaging was helpful in defining planes to allow for surgical excision. However, imaging rarely helps to clinch the diagnosis. Often the diagnosis is made either by imaging-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or histopathology after excision.6

DEC is the drug of choice for the medical treatment of filariasis. Small retroperitoneal lesions may resolve with antifilarial therapy.8 However, most cases reported,1 6 8 along with our case, opted for a surgical resection owing to diagnostic uncertainty and/or large size of the cyst which causes significant distress to the patient in terms of pain/pressure effect. Additionally, clear well-defined margins allow for resection with ease. Therefore, if confirmed by preoperative investigations such as FNAC, treatment with DEC can be started first and depending on the clinical response, surgical excision may be reserved for persistent symptomatic cysts.6 In our case, our patient was not diagnosed with filariasis preoperatively and received various non-surgical modalities of treatment which failed to bring any improvement, therefore, a decision for surgical exploration was taken in view of long symptomatic period and well-defined planes on CECT.

In conclusion, this case is important as it shows that filarial worm can hide as a nidus in form of cyst in unusual sites of the body like retroperitoneum, which has rich lymphatic network, without exhibiting its classic symptoms and signs affecting groin and limbs. Therefore, patients from endemic areas presenting with clinical and radiological findings of retroperitoneal cyst, especially with a history of failure of conventional treatment or/coupled with diagnostic uncertainty, should be investigated for the possibility of filariasis as one of the differential diagnoses and have treatment instituted as soon as possible.

Patient’s perspective.

I am glad that I finally get a treatment for my disease. It is unbelievable it was due to an insect bite. (Translated from Hindi)

Learning points.

Lymphatic filariasis is caused by nematode filariae, Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori and is commonly seen in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. The most common manifestation of the disease is hydrocele followed by lower limb lymphoedema and elephantiasis.

Filarial worm can hide as a nidus in form of cyst in unusual sites of the body like retroperitoneum, owing to its predilection for areas with rich lymphatic network and can present with/without exhibiting its classic signs and symptoms affecting groin and limbs.

Patients from endemic areas presenting with clinical and radiological findings of retroperitoneal cyst, especially with a history of failure of conventional treatment coupled with diagnostic uncertainty, should be investigated for the possibility of filariasis as one of the differentials and have treatment instituted as soon as possible.

Diethylcarbamazine is the drug of choice for the medical treatment of filariasis. Small retroperitoneal lesions may resolve with antifilarial therapy. Large symptomatic lesions may require surgery.

Footnotes

Contributors: DKD: lead surgeon on the case and editing of manuscript. NW: wrote the manuscript and editing of manuscript. NP: acquisition of data and images. AG: critically reviewed the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bakde A, Disawal A, Taori K, et al. Retroperitoneal cyst: an unusual presentation of filariasis. J Med Sci Health 2016;2:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal VK, Sashindran VK. Lymphatic filariasis in india : problems, challenges and new initiatives. Med J Armed Forces India 2006;62:359–62. 10.1016/S0377-1237(06)80109-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madhavan M, Vanaja SK, Chandra K, et al. “Atypical manifestations of filariasis in Pondycherry,”. Indian Journal of Surgery 1972;34:392–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chittipantulu G, Veerabhadraiah K, Ramana GV, et al. Retroperitoneal cyst of filarial origin. J Assoc Physicians India 1987;35:386–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava A, Agrawal A. Large retroperitoneal filarial lymphangiectasia. Med J Armed Forces India 2016;72:180–2. 10.1016/j.mjafi.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganesan S, Galodha S, Saxena R. Retroperitoneal cyst: an uncommon presentation of filariasis. Case Rep Surg 2015;2015:1–3. 674252 10.1155/2015/674252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metha NN, Dalavi VS, Mehta NP. Filariasis presenting as acute abdominal pain: The role of imaging and image-guided intervention in diagnosis. Radiol Case Rep 2015;10:1125 10.2484/rcr.v10i2.1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapoor AK, Puri SK, Arora A, et al. Case report: Filariasis presenting as an intra-abdominal cyst. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2011;21:18–20. 10.4103/0971-3026.76048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giri A, Kundu AK, Chakraborty M, et al. Microfilarial worms in retroperitoneal mass: A case report. Indian J Urol 2000;17:57–8. [Google Scholar]