Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study is to evaluate the effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in participants suffering from chronic neurological deficits due to traumatic brain injury (TBI) of all severities in the largest cohort evaluated so far with objective cognitive function tests and metabolic brain imaging.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted of 154 patients suffering from chronic neurocognitive damage due to TBI, who had undergone computerised cognitive evaluations pre-HBOT and post-HBOT treatment.

Results

The average age was 42.7±14.6 years, and 58.4% were men. All patients had documented TBI 0.3–33 years (mean 4.6±5.8, median 2.75 years) prior to HBOT. HBOT was associated with significant improvement in all of the cognitive domains, with a mean change in global cognitive scores of 4.6±8.5 (p<0.00001). The most prominent improvements were in memory index and attention, with mean changes of 8.1±16.9 (p<0.00001) and 6.8±16.5 (p<0.0001), respectively. The most striking changes observed in brain single photon emission computed tomography images were in the anterior cingulate and the postcentral cortex, in the prefrontal areas and in the temporal areas.

Conclusions

In the largest published cohort of patients suffering from chronic deficits post-TBI of all severities, HBOT was associated with significant cognitive improvements. The clinical improvements were well correlated with increased activity in the relevant brain areas.

Keywords: TBI, HBOT, traumatic brain injury, hyperbaric oxygen, cognitive

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The major limitation relates to its retrospective methodology, however, this limitation is diminished by the fact that all patients of the study large cohort were treated at late chronic stage.

In regards to strengths, objective cognitive assessments using computerised tests (which are superior to any clinical questionnaire), were performed on each patient both pretreatment and post-treatment.

The study cohort consisted of a civilian population that does not have any potential secondary gain (such as financial compensation by reporting sick).

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the leading causes of death and disability in the general population.1 Following TBI, patients may experience a set of symptoms known as postconcussion syndrome (PCS). PCS symptoms include headaches, dizziness, neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive impairments.2 PCS can continue for weeks or months, and up to 25% of all patients experience prolonged PCS in which the symptoms last for over 6 months.3

In the past years, there is growing clinical evidence regarding the effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) on PCS.4–6 Unfortunately, the clinical data gathered from those studies can be conflicting due to several inherent procedural issues, such as the use of non-objective endpoints, the lack of appropriate brain imaging as part of the inclusion criteria, the inappropriate placebo of a hyperbaric environment and the inclusion of patients that may gain secondary benefits from reporting sick.4 5 The current study represents the largest cohort evaluated until now of civilian participants suffering from PCS treated by HBOT, who had undergone objective metabolic brain imaging and a computerised neurocognitive test battery before and after the treatment.

Pathophysiology of PCS and HBOT

The most common pathological mechanism in TBI is diffuse shearing of axonal pathways and small blood vessels, also known as diffuse axonal injury.7 Secondary pathological mechanisms of TBI include ischaemia, mild oedema and other biochemical and inflammatory processes culminating in impaired regenerative and/or healing processes resulting from increasing tissue hypoxia.8 Due to the diffuse nature of injury, affecting multiple brain areas,9 10 cognitive impairments are usually the predominant symptoms.

Global brain hypoperfusion, and its related tissue ischaemia, detected in patients suffering from TBI, serves as a rate-limiting factor for any regenerative process.11–13 By increasing the oxygen level in blood and body tissues, HBOT can augment the repair mechanisms.5 Various models have strongly suggested that HBOT can induce angiogenesis, improve brain plasticity, enhance neurogenesis and synaptogenesis and foster functional recovery.14 15

Conflicting clinical HBOT data and objective measurements in PCS

Some of the previous studies which evaluated the effect of HBOT on chronic neurological and cognitive impairments due to TBI, mainly used self-assessment questionnaires as their primary endpoints.16–18 Such endpoints have several inherent disadvantages. First, they lack an objective evaluation that is not biased by the patients' perspectives. Second, self-administrated questionnaires are exposed to various confounding variables such as litigation and compensation.19 Unlike the questionnaires, standardised cognitive tests with high test–retest reliability can and should be used as objective evaluations of neurocognitive impairments.20 In addition, novel brain imaging techniques such as single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and perfusion sequences in MRI, which evaluate cerebral blood flow and brain metabolism, can shed new light in PCS diagnosis and in evaluating therapeutic interventions.20 In clinical studies which used objective cognitive assessments, HBOT was found to induce significant improvements in patients suffering from PCS due to mild TBI.5 6 15 21 However, to the best of our knowledge, the objective effect of HBOT on chronic neurocognitive impairments stemming from moderate to severe TBI (in addition to mild) has not been investigated.

In addition to objective evaluations, there are inherent ethical and logistic difficulties in handling the sham control in HBOT trials.4 5 20 22 HBOT includes two active ingredients: pressure and oxygen. Pressure is needed to increase plasma oxygen, but the pressure change alone may also have significant cellular effects.5 Additionally, the greatest effect of pressure is in human tissues that are under tight autoregulation pressure control, such as the brain, where the intracranial pressure is normally 0.0092–0.0197 atm.23 24 To generate a pressure sensation, the chamber pressure must be 1.2 ATA or higher. However, such a change in environmental pressure (from 1 ATA to 1.2 ATA) and subsequent tissue oxygenation (with an increase of tissue oxygenation by at least 50%) has a significant biological effect.25 26 Thus, sham therapy in previous studies using 1.2 ATA on 21% inhaled oxygen (ie, air) cannot be regarded as an inert or sham control but rather as a lower dose of the active ingredient.4 20 In regards to a possible effect of vasoconstriction of the large blood vessels induced by hyperbaric oxygen—it has been well established that the tissues are saturated by hyperoxia and do not suffer from hypoxia, as the vasoconstriction effect is compensated by increased plasma oxygen content and microvascular blood flow.27

Any increase in pressure, even with reduced oxygen percentage, cannot serve as a true placebo, but rather as a low dosage of the active ingredient, further supporting the need for objective data gathered from large cohorts of patients suffering from PCS and treated by HBOT.

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the objective effects of HBOT on patients with TBI suffering from chronic neurological deficits stemming from mild, moderate and severe TBI, in the largest cohort evaluated until now. Since all the patients had metabolic brain imaging and a computerised neurocognitive test battery before and after HBOT, correlations between specific cognitive indexes and their related brain regions activity were also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Participants

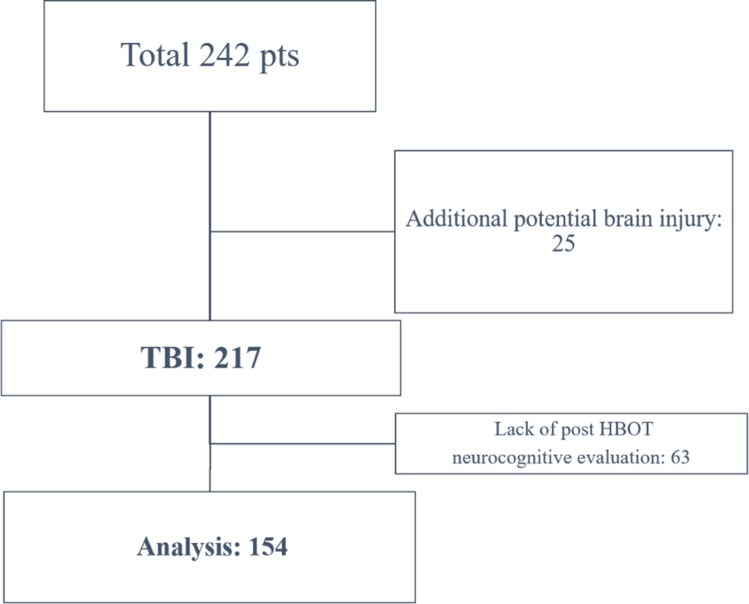

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients suffering from TBI-related chronic neurocognitive damage (more than 3 months from injury), treated by HBOT between January 2008 and January 2017 at the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Research, Assaf Harofeh Medical Center, Israel. Patients were included if they had pre-HBOT and post-HBOT computerised cognitive evaluations. Patients with a history of potential additional brain insults, such as spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage, anoxic brain injury or history of prior cognitive impairment, were excluded (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patients flowchart.TBI, traumatic brain injury; HBOT, hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Patients and public involvement

Patients and public weren’t involved in the study due to its retrospective nature.

TBI severity

TBI severities were rated according to the TBI admission documents. Mild TBI was defined as loss of consciousness (LOC) with duration of 0–30 min, post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) with duration of less than a day and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) grade of 13–15.28 Moderate TBI was defined as LOC with duration of more than 30 min and up to 24 hours, PTA with duration of 1–7 days and GCS grade of 9–12. Severe TBI was defined as LOC with duration of more than 24 hours, PTA with duration of more than 7 days and GCS less than 9. In addition, if there was imaging evidence of an injury such as a haematoma, contusion or haemorrhage, then the TBI was classified as moderate to severe.28

Hyperbaric oxygen treatment

Patients were treated with 40–70 daily hyperbaric sessions, 5 days a week. Each session consisted of 60/90 minutes of exposure to 100% oxygen at 1.5/2 ATA.

Cognitive assessment

The patients' cognitive functions were assessed by NeuroTrax computerised cognitive tests (NeuroTrax).29 The NeuroTrax tests evaluate various aspects of brain functions and include verbal memory (immediate and delayed recognition), non-verbal memory (immediate and delayed recognition), go/no go response inhibition, problem solving, Stroop interference, finger tapping, catch game, staged information processing speed (single digit, two-digit and three-digit arithmetic), verbal function and visual spatial processing. Cognitive index scores were computed from the normalised outcome parameters for memory, executive function, attention, information processing speed, visual spatial, verbal function and motor skills domains.30 A global cognitive score was computed as the average of all index scores for each individual.

After administration, the NeuroTrax data were uploaded to the NeuroTrax central server, and outcome parameters were automatically calculated using software blind to diagnosis or testing site. To account for the well-known effects of age and education on cognitive performance, each outcome parameter was normalised and fit to an IQ-like scale (mean=100, SD=15) according to the patient’s age and education. The normative data used by NeuroTrax consist of test data from cognitively healthy individuals in controlled research studies at more than 10 sites.31

Specifically, the patients were given two different versions of the NeuroTrax test battery before and after HBOT, to allow repeated administrations with minimal learning effects. Test–retest reliability for these versions was evaluated and found to be high, with no significant learning effect.32 33 Regarding the current study cohort, in a previous randomised controlled trial in patients suffering from TBI, the NeuroTrax scores were found to be stable in the retest of the control group.21

Brain SPECT imaging

Brain activity was assessed using SPECT 1–2 weeks prior to and after the HBOT period. The SPECT method was selected for evaluation due to its known normal range and test/retest established validity. The imaging was conducted using 925–1110 MBq (25–30 mCi) of a technetium-99-methyl-cysteinate-dimmer (Tc-99m-ECD) at 40–60 min postinjection, using a dual detector gamma camera (ECAM or Symbia T, Siemens Medical Systems) equipped with high-resolution collimators. Data were acquired in three-degree steps and reconstructed iteratively using the Chang method of attenuation correction (μ=0.12/cm).34

Both pretreatment and post-treatment SPECT images were normalised to the median maximal brain activity in the entire brain and were then reoriented into Talairach space using NeuroGam software (Segami) to identify Brodmann cortical areas and to compute the mean perfusion in each Brodmann area (BA). In addition, volume-rendered brain perfusion images were reconstructed and normalised to the entire brain median maximal activity. All SPECT analyses were done by study team members who were blinded to the laboratory and clinical data. SPECT scans were performed late morning to midday. On the day of the SPECT scan, patients were treated with only their chronic medications and were instructed not to smoke. Changes in perfusion in all Brodmann areas for each subject were determined by calculating the percentage of the difference of the normalised activity values between post-treatment and pretreatment divided by the pretreatment value.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as means±SDs. The normal distribution for all variables was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The mean differences between cognitive index scores before and after HBOT were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Bonferroni tests. Multiple linear regression models and multivariate logistic regression models were performed to control for potential confounders and to determine independent predictors for clinical outcome. The alpha level was set to 0.05. Data were statistically analysed using SPSS software (V.22.0).

Results

Patient profiles

Of the 242 patients suffering from neurocognitive impairment due to TBI treated by HBOT between January 2008 and January 2017, 25 patients had potential additional brain insults and 63 did not have repeat computerised neurocognitive evaluations. Therefore, 154 patients were included in the final analysis, of whom 100 patients completed pre-HBOT and post-HBOT SPECT imaging (figure 1).

The patients' baseline characteristics are summarised in table 1. The average age was 42.7±14.6 years, and 58.4% were men. All patients had documented TBI 3 months to 33 years (mean 4.6±5.8, median 2.75 years) prior to HBOT. Sixty-nine (44.8%) had neurocognitive impairments due to mild TBI, 24 (15.6%) moderate TBI and 61 (39.6%) severe TBI. Most of the patients (86.2%) had cognitive impairment as their main symptom (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Total | Mild TBI | Moderate TBI | Severe TBI | Significance |

| Patients (n) | 154 (100%) | 69 (44.8%) | 24 (15.6%) | 61 (39.6%) | |

| Age (years) | 42.7±14.6 | 48.8±12.0 | 41.7±12.7 | 36.2±15.3 | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 90 (58.4%) | 31 (44.9%) | 13 (54.2%) | 46 (75.4%) | =0.002 |

| Women | 64 (41.6%) | 38 (55.1%) | 11 (45.8%) | 15 (24.6%) | |

| Education (years) | 14.8±3.3 | 14.9±3.6 | 14.9±3.3 | 14.6±3.1 | =0.895 |

| Traumatic event | |||||

| Motor vehicle accident | 116 (75.3%) | 56 (81.2%) | 17 (70.8%) | 43 (70.5%) | =0.048 |

| Fall | 21 (13.6%) | 8 (11.6%) | 1 (4.2%) | 12 (57.1%) | |

| Blow | 12 (7.8%) | 5 (7.2%) | 5 (20.8%) | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Blast | 4 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (4.2%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| Penetrating | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Time from trauma (years) | 4.6±5.8 | 4.4±5.9 | 5.0±5.8 | 4.6±5.7 | =0.923 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Cognitive | 100 (86.2%) | 38 (74.5%) | 19 (90.5%) | 43 (97.7%) | =0.004 |

| Motor | 22 (19.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (4.8%) | 20 (45.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Sensory | 32 (27.6%) | 12 (23.5%) | 7 (33.3%) | 13 (29.5%) | =0.653 |

| Dizziness/vertigo | 17 (14.7%) | 14 (27.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (2.3%) | =0.002 |

| Tinnitus | 30 (25.9%) | 26 (51.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 2 (4.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Headaches | 20 (17.2%) | 12 (23.5%) | 3 (14.3%) | 5 (11.4%) | =0.272 |

| HBO sessions | 52.0±9.9 | 49.4±10.1 | 49.0±10.3 | 56.1±8.2 | =0.0001 |

| HBO protocol (ATA) | |||||

| 1.5 | 106 (69.3%) | 46 (67.6%) | 18 (75.0%) | 42 (68.9%) | =0.795 |

| 2 | 47 (30.7%) | 22 (32.4%) | 6 (25.0%) | 19 (31.1%) | |

| Adverse events | 18 (12.0%) | 10 (15.2%) | 3 (12.5%) | 5 (8.3%) | =0.499 |

HBO, hyperbaric oxygen; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Statisical significance (p<0.05) marked in bold.

Patients were treated with 40–70 (mean 52.0±9.9) sessions of hyperbaric oxygen at 1.5–2 ATA. Eighteen (12%) patients reported adverse events, which included mild barotrauma of the ears and palpitations/dyspnoea, while in the chamber.

Severity of TBI

In our cohort, patients who suffered severe TBI were found to be younger with higher proportion of men than in the mild and moderate TBI groups (p<0.0001 and p=0.002, respectively, table 1). As expected, the severe TBI group had significantly higher proportions of cognitive impairment and motor deficits (p=0.004 and p<0.0001, respectively, table 1). The mild and moderate TBI groups had higher percentages of tinnitus and/or dizziness (p<0.0001 and p=0.002, respectively, table 1).

Severe TBI

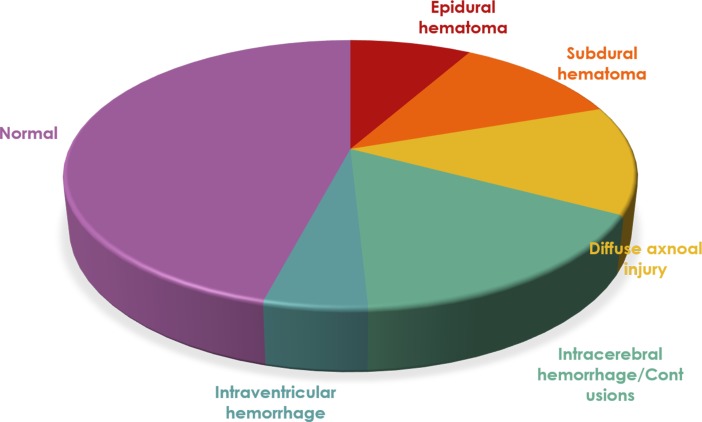

Sixty-one patients had severe TBI. The main imaging findings at their admission are summarised in figure 2. Of those 61 patients, 36 (59%) had surgical intervention during the acute event.

Figure 2.

Imaging findings in the severe traumatic brain injury group.

Neurocognitive evaluation

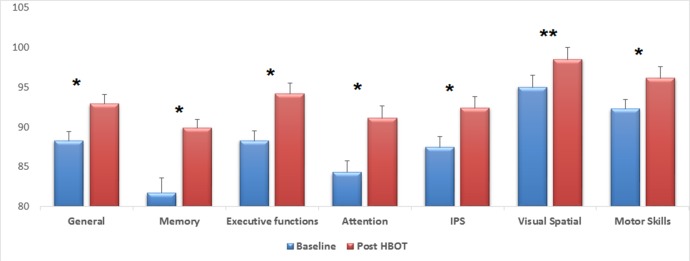

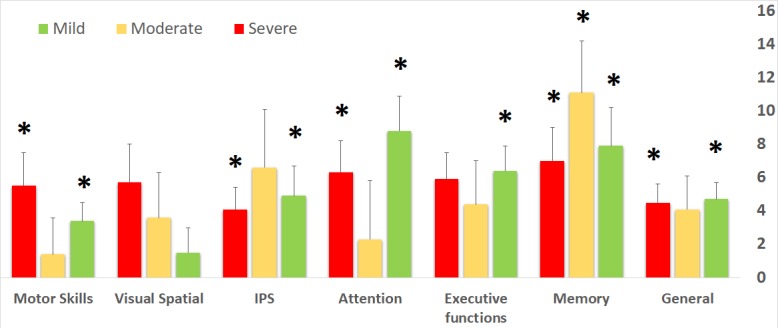

The effect of HBOT on the patients’ cognitive functions, as assessed by the eight cognitive summary scores, is summarised in table 2 and figure 3. As can be seen, HBOT induced significant improvements in all of the cognitive domains with a mean change of 4.6±8.5 (p<0.00001). The most prominent improvement was in the memory index, with 8.1±16.9 (p<0.00001), and in attention, with 6.8±16.5 (p<0.0001) (table 2, figure 3).

Table 2.

Cognitive indices pre-HBOT and post-HBOT of the entire study cohort

| Baseline | Post-HBOT | Mean change | P values | |

| General | 88.3±15.2 | 92.9±14.2 | 4.6±8.5 | <0.0001 |

| Memory | 81.7±23.2 | 89.9±21.9 | 8.1±16.9 | <0.0001 |

| Executive functions | 88.3±16.6 | 94.2±15.1 | 5.9±12.0 | <0.0001 |

| Attention | 84.3±20.5 | 91.1±18.4 | 6.8±16.5 | <0.0001 |

| IPS | 87.5±17.0 | 92.4±15.7 | 4.9±13.1 | <0.0001 |

| VSP | 95.0±18.0 | 98.5±18.0 | 3.4±14.6 | =0.005 |

| Motor skills | 92.3±17.3 | 96.2±14.5 | 3.9±11.7 | <0.0001 |

HBOT, hyperbaric oxygen therapy; IPS, information processing speed; VSP, visual spatial processing.

Figure 3.

Mean changes of post-HBOT compared with pre-HBOT for the entire cohort. After HBOT, all cognitive domains improved significantly, with the most striking changes seen in memory and attention. *P<0.0001, **p=0.005, HBOT, hyperbaric oxygen therapy; IPS, information processing speed.

The mild TBI group had the largest improvement in attention (8.8±2.1), followed by memory (7.9±2.3). Patients in the moderate TBI group had noticeable improvements in memory (11.1±3.1), followed by information processing speed (6.6±3.5). Finally, the severe TBI group had the largest improvement in memory (7.0±2.0), followed by attention (6.3±1.9) (figure 4). Using ANOVA analysis for repeated measures, there were no significant differences in all cognitive domains improvements between the different TBI severity groups.

Figure 4.

Mean changes of post-HBOT compared with pre-HBOT across the different TBI severities. Both patients who suffered mild and severe TBI groups had improvements in general, memory, attention, information processing speed and motor skills scores, whereas patients who suffered moderate TBI had significant improvement in memory. *P<0.05. HBOT, hyperbaric oxygen therapy; IPS, information processing speed; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

The magnitude of the change in a cognitive score has different implications for patients at low or high baseline levels. Therefore, we further inspected the effect of HBOT on the relative changes, that is, the changes relative to the baseline value, in each of the cognitive measured indexes. Marked improvements defined as >10% increase compared with baseline cognitive index were found, with different percentages, in all three study groups as summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Large significant increases (>10% change) in cognitive indices proportions across traumatic brain injury (TBI) groups

| Total | Mild TBI | Moderate TBI | Severe TBI | P values | |

| General | 36 (23.4%) | 15 (21.7%) | 7 (29.2%) | 14 (23.0%) | =0.756 |

| Memory | 64 (41.6%) | 28 (40.6%) | 9 (37.5%) | 27 (44.3%) | =0.830 |

| Executive functions | 51 (33.1%) | 23 (33.3%) | 7 (29.2%) | 21 (34.9%) | =0.897 |

| Attention | 62 (40.3%) | 27 (39.1%) | 8 (33.3%) | 27 (44.3%) | =0.631 |

| Information processing speed | 48 (31.2%) | 23 (33.3%) | 12 (50%) | 13 (21.3%) | =0.032 |

Confounders

Relative change higher than 10% from baseline was considered a significant clinical improvement. Age, gender, education level, TBI severity, the time from injury to HBOT, HBOT protocol and number of sessions had no significant effect on the clinical improvement in the general, memory, attention, information processing speed and executive functions domains (p>0.05).

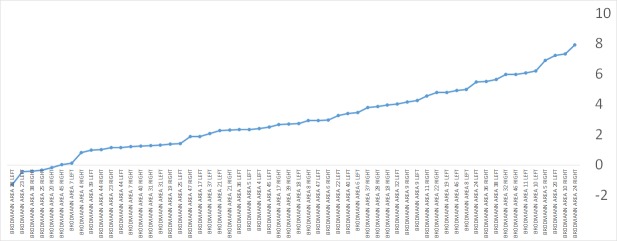

Metabolic imaging of the brain using SPECT

One hundred patients had brain SPECT evaluations before and after HBOT. When calculating the mean relative change in each cortical Brodmann area for the entire cohort, the largest changes were in the anterior temporal tip areas (BA 38, BA 28, BA 20) and in the prefrontal cortex (BA 10) (figure 5). However, these changes were minor, in the range of 3%–4% relative change. Further analysis per TBI severity group revealed several differences in Brodmann areas with involvement of the perirhinal cortex (BA 36) and the primary visual cortex (BA 18), as seen in figure 6.

Figure 5.

The mean relative change in Broadmann areas posthyperbaric oxygen therapy for the entire study cohort.

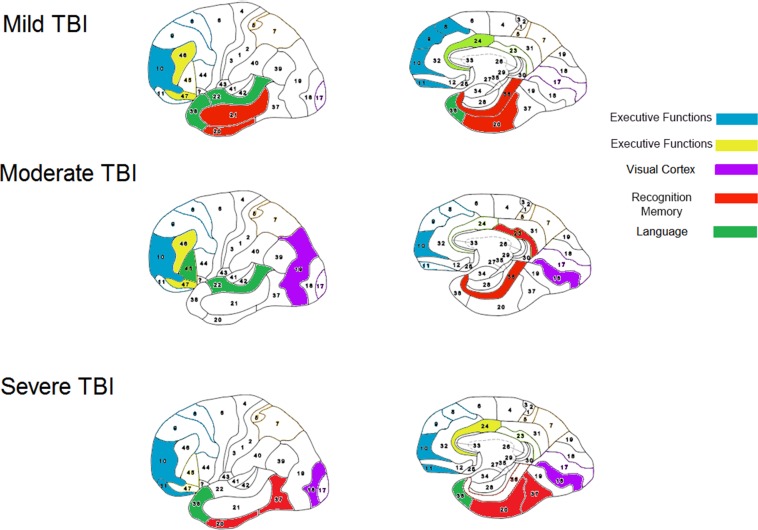

Figure 6.

Cognitive functions correlated with Brodmann areas. Each of the traumatic brain injury (TBI) groups (mild, moderate and severe) had perfusion/metabolism increase in specific Brodmann areas correlated with improved cognitive function.

To correlate SPECT imaging and cognitive changes, analysis was performed on the top 20 patients who had the largest cognitive improvement (>10% relative increase from baseline). There was a significantly larger magnitude of metabolism increase (5%–8%), compared with the entire cohort average increase (2%–4%) (p<0.05). The most striking changes were found in the anterior cingulate (BA 24, (p=0.01)) and the postcentral cortex (BA 5, (p=0.04)), in the prefrontal areas (BA 10 (p=0.04), BA 11 (p=0.07), BA 46 (p=0.07)) and in the temporal areas (BA 20 (p=0.02), BA 38 (p=0.07), BA 36 (p=0.1)).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates the neurotherapeutic effects of HBOT for chronic TBI of all severities. Even though treatment started during the late chronic stage (mean 4.6±5.8 years, median 2.75 years) after the acute insult, HBOT was still found to be effective regardless of the TBI severity. The clinical improvements seen in all cognitive domains were well documented by objective computerised neurocognitive tests. The most significant measurable improvements were in memory, attention and executive function. We found the clinical improvement to be well correlated with increased brain activity in relevant brain areas, with significantly higher increases in patients with better cognitive improvements.

In addition to tissue oxygenation, numerous mechanisms of cellular and vascular repair by HBOT have been suggested in addition to tissue oxygenation.5 35 These include improved mitochondrial function and cellular metabolism, improved blood–brain barrier and inflammatory reactions, reduced apoptosis, alleviation of oxidative stress, increased levels of neurotrophins and nitric oxide and upregulation of axonal guidance agents.5 36 Moreover, the effects of HBOT on neurons can be mediated indirectly by glial cells. HBOT may also promote neurogenesis of endogenous neural stem cells.5 36 The common denominator underlying all these mechanisms is that they are oxygen dependent. HBOT may enable the metabolic change simply by supplying the missing energy/oxygen needed for these regeneration processes.36 The induction of angiogenesis and improved brain metabolism, as demonstrated in this study, may serve as the infrastructure that enables the regenerative process and the preservation of newly generated neuronal functioning.14 35 37

The correlation between specific cognitive function improvements with the metabolic brain imaging changes gives further strength to the study results and serves as an excellent tool for gaining better understanding of brain functionality (figure 6):

The perirhinal cortex activation after HBOT was most prominent in patients who had significant memory improvement. The perirhinal cortex has a critical role in object recognition memory while interacting with the hippocampus.38 Since the memory assessments in the cognitive tests were indeed recognition tasks, this area is expected to be involved.

The prefrontal cortex (BA 10, BA 11) and more specifically, the inferior frontal gyrus (BA 46, BA 47) activations after HBOT were prominent in all patients with significant executive function improvements. The right frontal gyrus is known to mediate a go/no go task,39 which was among the executive function tests used in the present study. The prefrontal gyrus is presumed to act as a filtering system that enhances goal directed activities and inhibits irrelevant activations. This filtering mechanism enables executive control.40

The anterior cingulate gyrus (BA 24) activation after HBOT was seen in the subjects with attention improvement. The anterior cingulate gyrus is presumed to be involved in error detection, especially in a Stroop task,41 which was used in the attention tests. Lesions in this area can cause inattention to akinetic mutism.41

This study has several limitations. The major one relates to its retrospective methodology. This limitation is diminished when considering that this large cohort of patients was treated at late chronic stages. The findings presented here are in agreement and reinforce the findings from previous prospective controlled trials in which the neuroplasticity effects of HBOT were demonstrated in chronic stages of different types of brain injuries.15 21 42 43 Moreover, the correlation between the changes in cognitive function and the metabolic brain imaging gives further strength to the results.

Another important limitation relates to the HBOT protocol which was inconsistent across the cohort. Although significant neurotherapeutic effects were seen with 60 min of 1.5 ATA, the optimal protocol needed to induce maximal neuroplasticity for the specific individual, with minimal side effects has not been investigated.

The strengths of the study are worth mentioning. First, objective cognitive assessments using computerised tests were performed on each patient both pretreatment and post-treatment. Objective measures are significantly superior to PCS questionnaires which are inaccurate, variable and contain various confounders rather than reflect the true PCS state.44 Second, most of the patients in the study underwent an objective ancillary brain SPECT to confirm PCS diagnosis prior to HBOT. This practice is crucial when considering the differential diagnosis following TBI (PTSD, depression, etc).

Moreover, post-treatment brain SPECTs revealed an anatomical–functional correlation in regards to HBOT’s effect in brain neuroplasticity. Third, the study cohort consisted of a civilian population that does not have any potential secondary gain (such as financial compensation) by reporting sick.

Previous studies included patients with PCS who suffered mild TBI injury. Considering its strengths and limitations, the current study implies that the cognitive function of patients with post-TBI, can be improved significantly, irrespectively of whether the primary brain injury was classified as mild, moderate or severe. Although long-term data are still lacking, considering the high safety profile of the treatment, these results are promising and should encourage rehabilitation centres to consider HBOT for patients with chronic neurocognitive deficits following TBI. Future studies should monitor these patients in the long term (6 months, 12 months) as well as their return to activities of daily living.

Conclusions

HBOT was associated with significant cognitive improvements in patients who suffer from chronic neurocognitive deficits due to mild, moderate and severe TBI. Improvement in memory correlated with activation of the perirhinal cortex, improvement of executive functions correlated with activation of the inferior frontal gyrus and improvement in attention correlated with activation of the anterior cingulate gyrus.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AH: concept, data collection, data analysis, manuscript draft and manuscript review. SA: data collection and data analysis. GS, YB: data collection and manuscript review. SE: concept, data analysis, manuscript draft and manuscript review.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Data collected retrospectively were anonymised.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the institutional review board of Assaf Harfoeh Medical Center, Israel.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data are available by emailing amir.had@gmail.com.

Presented at: EUBS 2017, EANS 2017

References

- 1. Coronado VG, Xu L, Basavaraju SV, et al. Surveillance for traumatic brain injury-related deaths--United States, 1997-2007. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bazarian JJ, Wong T, Harris M, et al. Epidemiology and predictors of post-concussive syndrome after minor head injury in an emergency population. Brain Inj 1999;13:173–89. 10.1080/026990599121692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kashluba S, Paniak C, Blake T, et al. A longitudinal, controlled study of patient complaints following treated mild traumatic brain injury. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2004;19:805–16. 10.1016/j.acn.2003.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Figueroa XA, Wright JK. Hyperbaric oxygen: B-level evidence in mild traumatic brain injury clinical trials. Neurology 2016;87:1400–6. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Efrati S, Ben-Jacob E. Reflections on the neurotherapeutic effects of hyperbaric oxygen. Expert Rev Neurother 2014;14:233–6. 10.1586/14737175.2014.884928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tal S, Hadanny A, Sasson E, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy can induce angiogenesis and regeneration of nerve fibers in traumatic brain injury patients. Front Hum Neurosci 2017;11:508 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medana IM, Esiri MM. Axonal damage: a key predictor of outcome in human CNS diseases. Brain 2003;126(Pt 3):515–30. 10.1093/brain/awg061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kochanek PM, Clark RSB, Jenkins LW. TBI: pathobiology : Zasler ND, Katz DI, Zafonte RD, Brain injury medicine. New York: Demos medical publishing, 2007:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kushner D. Mild traumatic brain injury: toward understanding manifestations and treatment. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sohlberg MM, Mateer CA. Cognitive rehabilitation: an integrative neuropsychological approach. New York: The Guilford Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim J, Whyte J, Patel S, et al. Resting cerebral blood flow alterations in chronic traumatic brain injury: an arterial spin labeling perfusion FMRI study. J Neurotrauma 2010;27:1399–411. 10.1089/neu.2009.1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Østergaard L, Engedal TS, Aamand R, et al. Capillary transit time heterogeneity and flow-metabolism coupling after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014;34:1585–98. 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stein SC, Graham DI, Chen XH, et al. Association between intravascular microthrombosis and cerebral ischemia in traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery 2004;54:687–91. discussion 91 10.1227/01.NEU.0000108641.98845.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang Q, Zhang ZG, Ding GL, et al. Investigation of neural progenitor cell induced angiogenesis after embolic stroke in rat using MRI. Neuroimage 2005;28:698–707. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tal S, Hadanny A, Berkovitz N, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen may induce angiogenesis in patients suffering from prolonged post-concussion syndrome due to traumatic brain injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2015;33:943–51. 10.3233/RNN-150585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wolf G, Cifu D, Baugh L, et al. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen on symptoms after mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2012;29:2606–12. 10.1089/neu.2012.2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cifu DX, Hoke KW, Wetzel PA, et al. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on eye tracking abnormalities in males after mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev 2014;51:1047–56. 10.1682/JRRD.2014.01.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller RS, Weaver LK, Bahraini N, et al. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on symptoms and quality of life among service members with persistent postconcussion symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:43–52. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith-Seemiller L, Fow NR, Kant R, et al. Presence of post-concussion syndrome symptoms in patients with chronic pain vs mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2003;17:199–206. 10.1080/0269905021000030823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hadanny A, Efrati S. Treatment of persistent post-concussion syndrome due to mild traumatic brain injury: current status and future directions. Expert Rev Neurother 2016;16:875–87. 10.1080/14737175.2016.1205487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boussi-Gross R, Golan H, Fishlev G, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy can improve post concussion syndrome years after mild traumatic brain injury - randomized prospective trial. PLoS One 2013;8:e79995 10.1371/journal.pone.0079995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Efrati S, Ben-Jacob E. How and why hyperbaric oxygen therapy can bring new hope for children suffering from cerebral palsy--an editorial perspective. Undersea Hyperb Med 2014;41:71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Etzion Y, Grossman Y. Pressure-induced depression of synaptic transmission in the cerebellar parallel fibre synapse involves suppression of presynaptic N-type Ca2+ channels. Eur J Neurosci 2000;12:4007–16. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berman S, Abu Hamad R, Efrati S. Mesangial cells are responsible for orchestrating the renal podocytes injury in the context of malignant hypertension. Nephrology 2013;18:292–8. 10.1111/nep.12043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fujita N, Ono M, Tomioka T, et al. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen at 1.25 atmospheres absolute with normal air on macrophage number and infiltration during rat skeletal muscle regeneration. PLoS One 2014;9:e115685 10.1371/journal.pone.0115685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takemura A, Ishihara A. Mild hyperbaric oxygen inhibits growth-related decrease in muscle oxidative capacity of rats with metabolic syndrome. J Atheroscler Thromb 2017;24:26–38. 10.5551/jat.34686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bhutani S, Vishwanath G. Hyperbaric oxygen and wound healing. Indian J Plast Surg 2012;45:316–24. 10.4103/0970-0358.101309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malec JF, Brown AW, Leibson CL, et al. The mayo classification system for traumatic brain injury severity. J Neurotrauma 2007;24:1417–24. 10.1089/neu.2006.0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dwolatzky T, Whitehead V, Doniger GM, et al. Validity of a novel computerized cognitive battery for mild cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr 2003;3:4 10.1186/1471-2318-3-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zur D, Naftaliev E, Kesler A. Evidence of multidomain mild cognitive impairment in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol 2015;35:26-30 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doniger GM. Guide to normative data 2014. http://www1.neurotrax.com/docs/norms_guide.pdf

- 32. Melton JL. Psychometric evaluation of the Mindstreams neuropsychological screening tool. Panama City: Navy Experimental Diving Unit (US), 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schweiger GMD A, Dwolatzky T, D. Jaffe, E.S. Simon reliability of a novel computerized neuropsychological battery for mild cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropsychologica 2003;1:407–13. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jaszczak RJ, Chang LT, Stein NA, et al. Whole-body single-photon emission computed tomography using dual, large-field-of-view scintillation cameras. Phys Med Biol 1979;24:1123–43. 10.1088/0031-9155/24/6/003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hadanny A, Golan H, Fishlev G, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen can induce neuroplasticity and improve cognitive functions of patients suffering from anoxic brain damage. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2015;33:471–86. 10.3233/RNN-150517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Efrati S, Fishlev G, Bechor Y, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen induces late neuroplasticity in post stroke patients--randomized, prospective trial. PLoS One 2013;8:e53716 10.1371/journal.pone.0053716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen J, Zhang ZG, Li Y, et al. Intravenous administration of human bone marrow stromal cells induces angiogenesis in the ischemic boundary zone after stroke in rats. Circ Res 2003;92:692–9. 10.1161/01.RES.0000063425.51108.8D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brown MW, Aggleton JP. Recognition memory: what are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus? Nat Rev Neurosci 2001;2:51–61. 10.1038/35049064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 2004;8:170–7. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 2001;24:167–202. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 2000;4:215–22. 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01483-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harch PG. Hyperbaric oxygen in chronic traumatic brain injury: oxygen, pressure, and gene therapy. Med Gas Res 2015;5:9 10.1186/s13618-015-0030-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harch PG, Andrews SR, Fogarty EF, et al. A phase I study of low-pressure hyperbaric oxygen therapy for blast-induced post-concussion syndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Neurotrauma 2012;29:168–85. 10.1089/neu.2011.1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Potter S, Leigh E, Wade D, et al. The rivermead post concussion symptoms questionnaire: a confirmatory factor analysis. J Neurol 2006;253:1603–14. 10.1007/s00415-006-0275-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.