Abstract

Objectives

The main aim of this study was to assess the overall tuberculosis (TB) treatment success in Ethiopia and to identify potential factors for poor TB treatment outcome.

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis of published literature was conducted. Original studies were identified through a computerised systematic search using PubMed, Google Scholar and Science Direct databases. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistic. Pooled estimates of treatment success were computed using the random-effects model with 95% CI using Stata V.14 software.

Results

A total of 230 articles were identified in the systematic search. Of these 34 observational studies were eligible for systematic review and meta-analysis. It was found that 117 750 patients reported treatment outcomes. Treatment outcomes were assessed by World Health Organization (WHO) standard definitions of TB treatment outcome. The overall pooled TB treatment success rate in Ethiopia was 86% (with 95% CI 83%_88%). TB treatment success rate for each region showed that, Addis Ababa (93%), Oromia (84%), Amhara (86%), Southern Nations (83%), Tigray (85%) and Afar (86%). Mainly old age, HIV co-infection, retreatment cases and rural residence were the most frequently identified factors associated with poor TB treatment outcome.

Conclusion

The result of this study revealed that the overall TB treatment success rate in Ethiopia was below the threshold suggested by WHO (90%). There was also a discrepancy in TB treatment success rate among different regions of Ethiopia. In addition to these, HIV co-infection, older age, retreatment cases and rural residence were associated with poor treatment outcome. In order to further improve the treatment success rate, it is strategic to give special consideration for regions which had low TB treatment success and patients with TB with HIV co-infection, older age, rural residence and retreatment cases.

Keywords: tuberclosis, treatment outcome, ethiopia, systematic review, meta-analysis, drug-susceptible

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study includes articles from different regions of the country which support the representativeness of the evidence obtained at the country level.

In addition to this, inclusion of more than 30 articles for both quantitative and qualitative synthesis was considered as the major strength of this study.

The variation in the study design used among the included studies and the inclusion of only observational studies were considered as the major drawback of this study.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is a preventable and curable disease mainly transmitted through air from person to person. Majorly, it affects the lungs, but it can also damage other organs in the body.1 Common symptoms of active lung TB are cough with sputum and blood, chest pains, weakness, weight loss, fever and night sweats.1 2

TB is the ninth leading cause of death globally and the leading cause from a single infectious agent, ranking above HIV/AIDS. In 2016, it was responsible for an estimated 1.3 million and 374 000 TB deaths among HIV-negative and HIV-infected people, respectively.3 It is also the number one cause of death among HIV-infected individuals with an estimated two-fifth deaths among HIV-infected individuals being due to TB.1

Ethiopia is among the countries where TB is highly prevalent. WHO prepared three lists of countries based on the burden of TB, TB/HIV co-infection and multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). Accordingly, Ethiopia is among the 14 countries where there is high burden of TB, TB/HIV co-infection and MDR-TB. Even though the incidence of TB decreased by 54% and mortality because of TB decreased by 72% in the country in 2015,4 4000 deaths among HIV-infected individuals and 26 000 deaths among HIV-negative individuals still occurred in 2016.3 The decline in the incidence and mortality could in part be attributed to improvement in the TB detection rate,4 provision of isoniazid preventive therapy for HIV-infected individuals5 and early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART),6 a community-based package involving health extension workers.7

Since the discovery of the first anti-TB drug, streptomycin, in 19438 and the few drugs that followed (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide), drug development for drug-susceptible TB has lagged.8 9 As a result, the same anti-TB drug regimen that was first introduced half a century ago is being used today in the management of active, drug-susceptible TB.10 A 6-month course of four anti-TB drugs is used as a standard treatment for active, drug-susceptible TB disease. Isoniazid and rifampicin serve as the backbone of this regimen, with ethambutol and pyrazinamide given in the first 2 months of treatment.1 3 11 However, treatment success could be compromised by poor adherence mainly due to the long treatment period and the development of drug-resistant TB ultimately from the inadequate treatment of active TB.9 11 In Ethiopia, this four-drug, 6-month and 9–12-month regimen is also recommended as a first-line drug for the treatment of active drug-susceptible pulmonary TB and extrapulmonary TB (EPTB), respectively.12

Currently, the global TB treatment success rates were 83% for drug-susceptible TB, 78% for HIV-associated TB, 54% for MDR-TB and 30% for extensively drug-resistant TB.3 The WHO Global Plan aimed to achieve three 90-(90)−90 TB control program targets at least by 2025, such as; reach 90% of all people who need TB treatment, including 90% of people in key populations, and achieve at least 90% TB treatment success rate.13

According to the WHO report, Ethiopia is among the four countries where treatment outcomes of more than 10% of TB cases were not evaluated and documented.3 Even though there has been a recent systematic review on TB treatment outcome in Ethiopia,14 it doesn’t clearly assess the overall drug-susceptible TB treatment outcome independently and it also emphasis only on limited factors which associated with TB treatment outcome. In addition to this, there have also been several single studies published on TB treatment outcome in Ethiopia. However, there is a paucity of evidence regarding the overall drug-susceptible TB treatment success at the country level. Therefore, we aimed to get stronger evidence from the available literature regarding drug-susceptible TB treatment success and to identify all potential factors reported that are associated with poor TB treatment outcome in Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study design and search strategies

A systematic review and meta-analysis of published observational studies was conducted. Original studies providing information on the treatment outcomes of patients with TB were identified through a computerised systematic search using PubMed, Google Scholar and Science Direct databases. A combination of keywords and phrases like: ‘tuberculosis OR TB’, ‘treatment OR management’, ’Anti-TB’, ‘outcomes’, ‘treatment success’, ’smear-positive’, ‘smear-negative’, ‘Extra-pulmonary-TB’ and ‘Ethiopia’ were used to search articles in the databases (online supplementary file 1). The literature search, review and data extraction were performed from February to September 2017. Articles were retrieved up to 15 March 2017. Only those articles written in English language and conducted in Ethiopia were considered for this review.

bmjopen-2018-022111supp001.pdf (189.8KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

Observational studies fulfilling the following criteria were included in this study: studies reported as original articles; studies done on TB treatment outcomes; studies conducted in Ethiopia and written in English. References from the selected studies were also cross-checked to confirm that no relevant studies were excluded. Outcomes were reported according to the WHO definition of treatment success (cure or treatment completion), failure, default and death.15

Exclusion criteria

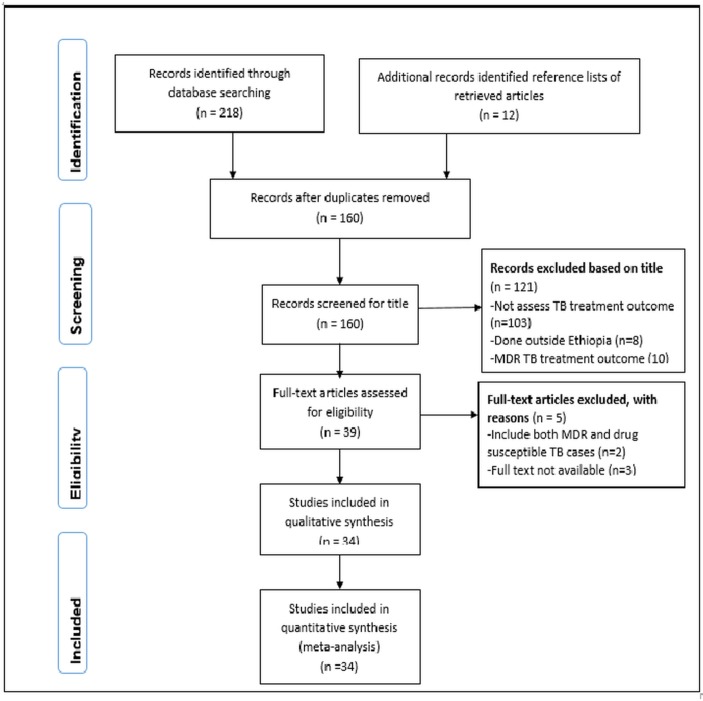

The following articles were excluded from this review: studies that focus on treatment outcome of patients with MDR-TB; studies that focus on both MDR-TB cases and drug-susceptible TB cases together; studies where full articles were no longer accessed and studies done outside Ethiopia. The selection of articles for review was done in three stages: looking at the titles alone, then abstracts and then the full text (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram showing the selection of studies for a systematic review on tuberculosis treatment success in Ethiopia, 2017. MDR, multidrug resistant; TB, tuberculosis.

Definitions of TB treatment outcomes

To classify treatment outcomes of patients with TB, the WHO and National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme (NTLCP) guidelines' standard definitions were used15 16 (table 1).

Table 1.

Tuberculosis (TB) treatment outcomes according to WHO and National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme (NTLCP) guidelines

| Outcome | Definition |

| Cured | A patient with TB with bacteriologically confirmed TB at the beginning of treatment who was smear-negative or culture-negative in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion. |

| Treatment completed | A patient with TB who completed treatment without evidence of failure, but with no record to show that sputum smear or culture results in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion were negative, either because the tests were not done or because results are unavailable. |

| Treatment failed | A patient with TB whose sputum smear or culture is positive at month 5later during treatment. |

| Died | A patient with TB who dies for any reason before starting or during the course of treatment. |

| Defaulter | A patient who has been on treatment for at least 4 weeks and whose treatment was interrupted for eight or more consecutive weeks. |

| Not evaluated | A patient with TB for whom no treatment outcome is assigned. This includes cases ‘transferred out’ to another treatment unit as well as cases for whom the treatment outcome is unknown to the reporting unit. |

| Treatment success | The sum of cured and treatment completed. |

Data extraction and review process

All of the research articles that were identified from searches of the electronic databases were imported into the ENDNOTE software V.X5 (ThomsonThomson Reuters, USA) and duplicates were removed. Before data extraction had begun, full-length articles of the selected studies were read to confirm the fulfilment of the inclusion criteria. Then, data extraction was performed by three authors (MAS, MBA and EAM) independently. The selected studies were reviewed to extract data like: year of publication; author(s); study design; sample size; type of TB (smear-negative pulmonary TB (PTB−), smear-positive pulmonary TB (PTB+) and EPTB); HIV status; TB treatment outcomes; geographical location of the study area, and factors affecting TB-treatment outcome (p value of <0.05). When there was a disagreement in data extraction between the reviewers, it was resolved through discussion and mutual agreement between the investigators.

Methodological quality assessment

All reviewers (MAS, MBA, EAM, EAG and TMA) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).17 18 The studies which have at least five NOS criteria were considered to be high-quality studies (online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2018-022111supp002.pdf (437.7KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis and heterogeneity

Statistical analyses were carried out by using Stata V.14 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA) software19 to estimate the pooled treatment success rate. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic.20 Random-effects meta-analyses were used to combine the results of included studies, and was measured as proportions of treatment outcomes with 95% CIs. The detailed description of the original studies was presented in a table and forest plot.

Patient and public involvement

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis, there were no direct involvement of patients and/or the public in this study.

Ethical consideration

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.21 Since it is a systematic review and meta-analysis, ethics committee or institutional review board permission was not sought.

Results

Literature search results

An electronic search gave a total of 230 articles. Among these 70 were found to be duplicated. Then the titles of 160 articles were checked and 121 were found irrelevant. Five articles were excluded after checking their abstracts. Finally, 34 articles were selected for inclusion in the meta-analysis (figure 1).

Study characteristics

This analysis included studies conducted in different regions of the country published from 2005 to 2017. From a total of 230 articles obtained through electronic search, 34 were found to be eligible and were included in this review. Majority 21 (62%) of the included studies were cross-sectional in nature,22–42 while 12 (35%) of the studies were cohort studies,43–54 and 1 was a case-control study.55 Most of the studies relied on 5 years data (range of 1–15 years) (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors | Year of publication | Study design | Duration in years | Study area | Sample size | HIV (%) |

| Ali et al 22 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 1 | Addis Ababa | 575 | 29.4 |

| Amante et al 55 | 2015 | Case-control study | 5 | Oromia | 976 | 18.3 |

| Asebe et al 44 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 2.5 | SNNPR | 1156 | 24.2 |

| Asres et al 23 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 7 | SNNPR | 846 | 9.1 |

| Balcha T et al 52 | 2015 | Cohort study | 3 | Oromia | 439 | 100 |

| Belayneh et al 45 | 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 5 | Amhara | 403 | 38.5 |

| Belayneh et al 24 | 2015 | Cross-sectional study | 2.7 | Tigray | 342 | 100 |

| Berhe et al 25 | 2012 | Cross-sectional study | 3 | Tigray | 407 | 8.6 |

| Birlie et al 46 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 5 | North-East Ethiopia | 810 | 17.4 |

| Dangisso et al 26 | 2014 | Retrospective trend analysis | 10 | Southern Ethiopia | 37 070 | – |

| Ejeta et al 47 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 5 | Western Ethiopia | 1175 | 17.1 |

| Endris et al 27 | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | Amhara | 417 | 5.8 |

| Gebreegziabher S et al 43 | 2016 | Prospective cohort | 1.7 | Amhara | 706 | 11.6 |

| Gebremariam et al 48 | 2016 | Retrospective cohort study | 6 | Oromia | 1649 | 9.5 |

| Gebrezgabiher et al 28 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 5.4 | SNNPR | 1537 | – |

| Getahun et al 49 | 2013 | Retrospective cohort study | 5 | Addis Ababa | 6450 | – |

| Hailu et al 29 | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | Addis Ababa | 2708 | 12.0 |

| Hamusse et al 50 | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | 15 | Central Ethiopia | 14 221 | 2.0 |

| Ketema et al 51 | 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | 3 | Oromia | 2226 | 9.7 |

| Mekonnen et al 30 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 4 | Amhara | 949 | 23.9 |

| Melese et al 31 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | Amhara | 339 | 12.7 |

| Moges et al 32 | 2015 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | Amhara | 181 | – |

| Mokenen D. et al 33 | 2015 | Cross-sectional study | 4 | Amhara | 990 | 23.8 |

| Munoz-Sellart et al 34 | 2009 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | SNNPR | 851 | – |

| Munoz-Sellart et al 35 | 2010 | Retrospective audit | 5.8 | SNNPR | 6547 | – |

| Shargie et al 36 | 2005 | Retrospective trend analysis | 7 | SNNPR | 19 971 | – |

| Sinshaw et al 37 | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | 5.5 | Amhara | 308 | 100 |

| Tefera et al 38 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | Amhara | 1280 | 20.5 |

| Tesfahuneygn et al 39 | 2015 | Cross-sectional study | 5.5 | North-East Ethiopia | 4275 | 13.7 |

| Tessema et al 40 | 2009 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | Amhara | 4000 | – |

| Tilahun et al 53 | 2016 | Retrospective cohort study | 5 | Addis Ababa | 491 | 16.7 |

| Workneh et al 54 | 2016 | Prospective cohort study | 1.6 | Amhara | 1314 | 19.9 |

| Zenebe T et al 42 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 2 | Afar | 380 | 47.6 |

| Zenebe Y et al 41 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 5 | Amhara | 1761 | 3.5 |

SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region.

Clinical characteristics of patients

A total of 117 750 patients with TB were included in the 34 studies. Of these, 51% (59916) patients with TB had PTB+, 21% (24428) had PTB− and 17.3% (20400) had EPTB. In this review around 5357 patients had TB-HIV co-infection which is reported by 26 studies. The remaining studies did not provide evidence for TB-HIV co-infection. The detailed description of individual study characteristics is mentioned in table 2.

TB treatment outcome in Ethiopia

This review showed that TB treatment success rate varies from 51% to 95%. Table 3 shows the detailed description of cure, treatment completed, defaulted, treatment failure, died and transferred out from individual included studies (table 3).

Table 3.

Description of overall treatment outcome of included studies

| Study Id | Authors | Successful treatment outcome | Unsuccessful treatment outcome | Successful treatment outcome (%) | Cured | Treatment completed | Defaulted | Treatment failure | Died | Transferred out |

| 1. | Ali et al 22 | 526 | 49 | 91.5 | 106 | 420 | 15 | 7 | 27 | 0 |

| 2. | Amante et al 55 | 646 | 330 | 66.2 | NR | NR | 100 | 18 | 212 | 0 |

| 3. | Asebe et al 44 | 814 | 144 | 85 | 262 | 552 | 97 | 4 | 43 | 198 |

| 4. | Asres et al 23 | 695 | 88 | 88.8 | 162 | 533 | 41 | 1 | 46 | 0 |

| 5. | Balcha T et al 52 | 349 | 59 | 85.5 | NR | NR | 32 | 0 | 27 | 31 |

| 6. | Belayneh et al 45 | 318 | 29 | 91.6 | 76 | 242 | 7 | 2 | 20 | 56 |

| 7. | Belayneh et al 24 | 242 | 100 | 70.7 | 43 | 199 | 7 | 5 | 88 | 0 |

| 8. | Berhe et al 25 | 361 | 44 | 89.1 | 343 | 18 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 6 |

| 9. | Birlie et al 46 | 685 | 68 | 91 | 103 | 582 | 2 | 6 | 60 | 57 |

| 10. | Dangisso et al 26 | 30 300 | 4552 | 87 | 14 147 | 16 153 | 3263 | 92 | 1197 | 2087 |

| 11. | Ejeta et al 47 | 832 | 181 | 82 | 170 | 662 | 84 | 2 | 95 | 162 |

| 12. | Endris et al 27 | 379 | 21 | 94.8 | 77 | 302 | 5 | 2 | 14 | 17 |

| 13. | Gebregziabher S et al 43 | 656 | 49 | 93 | 310 | 346 | 11 | 10 | 28 | 0 |

| 14. | Gebremariam et al 48 | 1437 | 94 | 93.9 | 421 | 1016 | 28 | 7 | 59 | 115 |

| 15. | Gebrezgabher et al 28 | 1310 | 227 | 85.2 | 181 | 1129 | 171 | 4 | 52 | 0 |

| 16. | Getahun et al 49 | 5331 | 590 | 90 | 1167 | 4164 | 328 | 26 | 236 | 351 |

| 17. | Hailu et al 29 | 2193 | 188 | 92.1 | 169 | 2024 | 99 | 6 | 83 | 184 |

| 18. | Hamusse et al 50 | 11 888 | 2333 | 83.6 | 9608 | 2280 | 1215 | 70 | 1048 | 0 |

| 19. | Ketema et al 51 | 2043 | 114 | 94.7 | 1906 | 137 | 27 | 24 | 63 | 69 |

| 20. | Mekonnen et al 30 | 853 | 96 | 89.9 | 132 | 721 | 28 | 21 | 47 | 0 |

| 21. | Melese et al 31 | 264 | 39 | 87.1 | 67 | 197 | 8 | 12 | 19 | 36 |

| 22. | Moges et al 32 | 127 | 13 | 90.7 | 36 | 91 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 41 |

| 23. | Mokenen D et al 33 | 853 | 107 | 88.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 30 |

| 24. | Munoz-Sellart et al 34 | 655 | 139 | 82.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 49 | 57 |

| 25. | Munoz-Sellart et al 35 | 4900 | 1095 | 81.7 | NR | NR | 667 | 24 | 404 | 552 |

| 26. | Shargie et al 36 | 8268 | 3708 | 69 | NR | NR | 3152 | 110 | 446 | 2000 |

| 27. | Sinshaw et al 37 | 238 | 70 | 77.3 | 32 | 206 | 37 | 2 | 31 | 0 |

| 28. | Tefera et al 38 | 1016 | 129 | 88.7 | 203 | 813 | 23 | 4 | 102 | 135 |

| 29. | Tesfahuneygn et al 39 | 3853 | 215 | 94.7 | 491 | 3362 | 76 | 13 | 126 | 207 |

| 30. | Tessema et al 40 | 1181 | 1139 | 50.9 | NR | NR | 730 | 6 | 403 | 1680 |

| 31. | Tilahun et al 53 | 420 | 14 | 96.8 | NR | NR | 3 | 2 | 9 | 55 |

| 32. | Workneh et al 54 | 1228 | 86 | 93.5 | 317 | 911 | 14 | 15 | 57 | 0 |

| 33. | Zenebe T et al 42 | 320 | 52 | 86 | 128 | 192 | 34 | 1 | 17 | 8 |

| 34. | Zenebe Y et al 41 | 542 | 129 | 80.8 | NR | NR | 30 | 1 | 98 | 1090 |

NR, not reported.

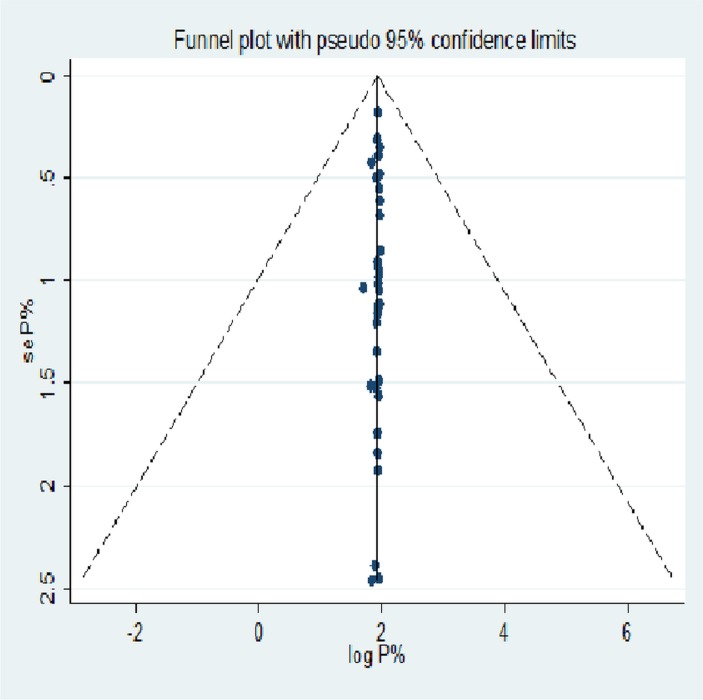

Meta-analysis

The Funnel plot depicted in figure 2 showed that there is symmetry between the studies and no significant publication bias was seen, or small study effect was insignificant. The sensitivity analysis also showed the absence of an excessive influence of individual studies. The point estimates calculated after omission of each study one by one lies within the CI of the ‘combined’ analysis (online supplementary file 3) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of SE by logit event rate.

bmjopen-2018-022111supp003.pdf (212.2KB, pdf)

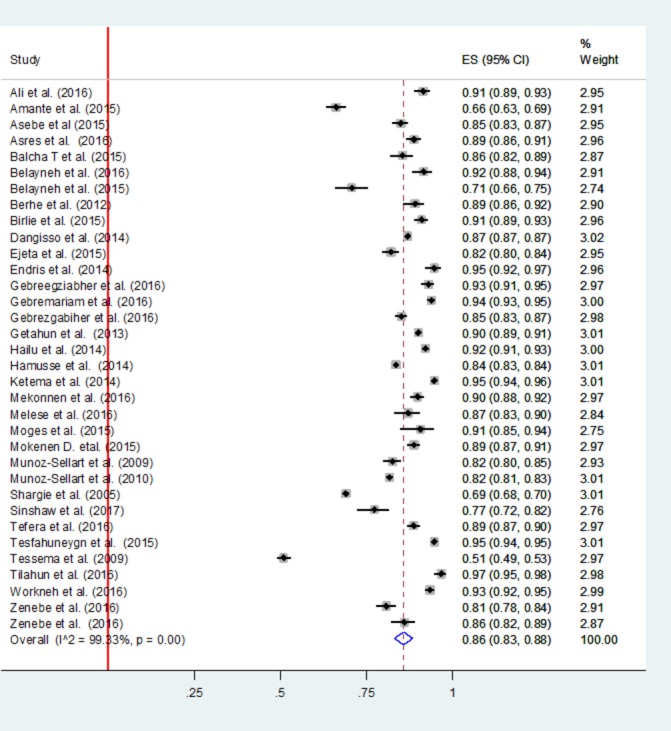

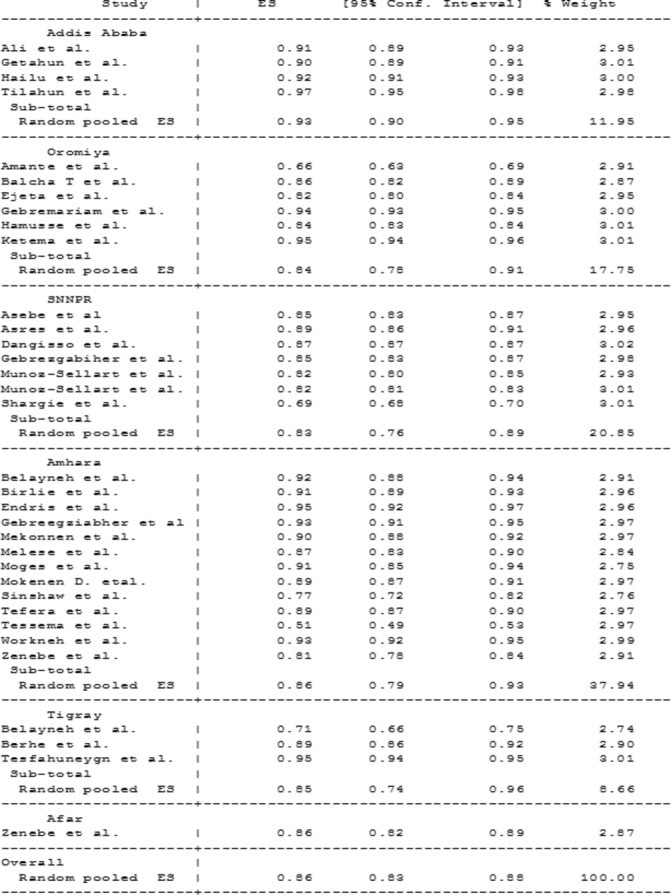

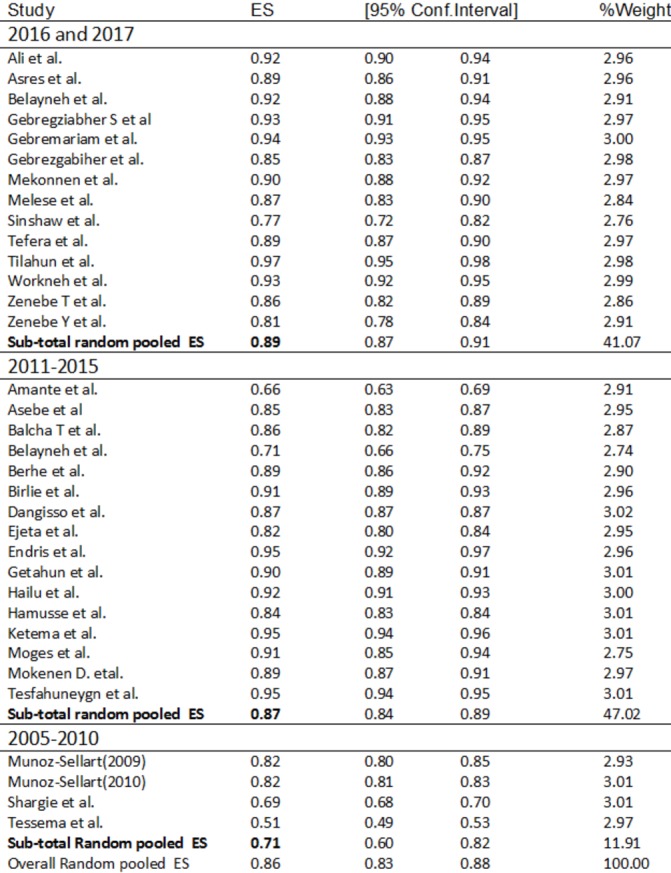

The overall estimate of TB treatment success

As indicated in the following forest plot the overall drug-susceptible TB treatment success rate in Ethiopia is 86% (95 % CI 83% to 88%) (figure 3). Subgroup analysis based on the study area showed that Addis Ababa (93%), Oromia (84%), Amhara (86%), SNNPR (83%), Tigray (85%) and Afar (86%) had TB treatment success rate (figure 4). The finding of this study also showed that TB treatment outcome in Ethiopia was improving over time. The subgroup analysis showed that TB treatment success from 2005 to 2010 was 71%, from 2011 to 2015 it was 87% and from 2016 to 2017 it was 89% (figure 5).

Figure 3.

Main meta-analysis of success of tuberculosis treatment in Ethiopia.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of success of tuberculosis treatment in the different regions of Ethiopia.

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis of success of tuberculosis treatment based on year of publication.

Factors significantly associated with poor treatment outcome

As indicated in table 4, different demographic and clinical characteristics were reported by the reviewed studies as having a significant association with poor TB treatment outcome (p <0.05). Among these the most frequently mentioned were old age, HIV co-infection, retreatment case and rural residence.

Table 4.

Factors which had a significant association with poor tuberculosis treatment outcome

| Authors | Reported factors |

| Ali et al 22 | Age >65 years, PTB+ |

| Amante et al 55 | Lack of person to be contacted at a time of treatment interruption, sputum smear-negative diagnosis, HIV-positive status |

| Asebe et al 44 | The age group 45–64 years had significantly lower treatment success rate |

| Asres et al 23 | Older, rural dwellers and HIV-positive |

| Balcha T et al 52 | Low mean upper arm circumference (MUAC) |

| Belayneh et al 45 | NR |

| Belayneh et al 24 | Having low baseline CD4 count (less than 200 cells/L), to be at WHO stage IV |

| Berhe et al 25 | Older age, family sizes greater than five persons, unemployed and retreatment cases |

| Birlie et al 46 | Old age, of low baseline body weight and in TB/HIV co-infected patients |

| Dangisso et al 26 | PTB− cases, older than 65 years, retreatment cases |

| Ejeta et al 47 | HIV serostatus, smear result follow-up at the second, fifth and seventh months |

| Endris et al 27 | No significantly associated factors |

| Gebreegziabher et al 43 | HIV-positive |

| Gebremariam et al 48 | Patients without known HIV status, HIV-positive patients with TB |

| Gebrezgabiher et al 28 | PTB−, rural residence, EPTB, 55–64 years old |

| Getahun et al 49 | NR |

| Hailu et al 29 | PTB+, HIV co-infection and unknown HIV serostatus |

| Hamusse et al 50 | Patients aged 25–49 years, ≥50 years, retreatment cases and TB/HIV co-infection |

| Ketema et al 51 | HIV-positive patients who remained sputum smear-positive at the end of month 2 and patients who reported missed doses |

| Mekonnen et al 30 | PTB+, HIV-positive |

| Melese et al 31 | Female, rural resident, negative smear result at the second month of treatment |

| Moges et al 32 | NR |

| Mokenen D. et al 33 | NR |

| Munoz-Sellart et al 34 | Age <5 years, living in a rural area, lack of smear conversion in the second month |

| Munoz-Sellart et al 35 | Having a positive smear at the second month of follow-up, PTB−, age >55 years, and being male |

| Shargie et al 36 | Patients on LCC (long-course chemotherapy) |

| Sinshaw et al 37 | Rural residence, baseline weight<43.7 kg, bedridden functional status, treatment side effect. |

| Tefera et al 38 | NR |

| Tesfahuneygn et al 39 | Non-adherence to anti-TB drugs |

| Tessema et al 40 | Rural areas, age group 25–34 years, PTB− |

| Tilahun et al 53 | TB/HIV co-infected patients, age less than 1 years |

| Workneh et al 54 | HIV-positive, diabetes |

| Zenebe T et al 42 | Age, sex, HIV status, associated with treatment outcome |

| Zenebe Y et al 41 | HIV-TB co-infection, young age (15–24 years), rural residence and retreatment of patients |

All the factors included in this table had a p value <0.05 in each study report.

EPTB, extrapulmonary tuberculosis; NR, not reported; PTB, pulmonary tuberculosis; PTB+, smear-positive PTB; PTB−, smear-negative PTB.

Discussion

TB treatment outcome is one of the performance indicators of the effectiveness of TB control programmes.40 This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted mainly to estimate the pooled treatment success rate of patients with drug-susceptible TB in Ethiopia. This review identified 34 studies (from 2005 to 2017) that assessed the treatment outcomes of drug-susceptible TB. All the studies included were observational studies which were conducted in different regions of Ethiopia; Amhara, Addis Ababa, Tigray, Oromia, Afar and Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR). The inclusion of studies conducted in various parts of Ethiopia makes this review representative to figure out the overall TB treatment success rate in the country. We analysed data from these studies which reported on treatment outcomes for a total of 117 750 patients with TB. All the included studies used NTLCP guidelines to define TB treatment outcomes which were adopted from WHO.15 16

The result of this study showed that the pooled estimate of TB treatment success rate of drug-susceptible TB in Ethiopia is 86% (95% CI 83% to 88%). This pooled TB treatment success rate was lower than the Ethiopian National Strategic Plan (2010–2015) treatment success target of 90%56 and WHO 2030 international target of ≥90%.3 This study result is relatively higher compared with a recent review done in Ethiopia which was 83.7%.14 According to the 2017 WHO global TB report, Ethiopia achieved a TB treatment success rate of only 84% for new TB cases when compared with the high TB burden countries reached or exceeded a 90% treatment success rate such as; Cambodia (94%), China (94%), Pakistan (93%), Bangladesh (93%), Vietnam (92%), Philippines (91%) and Korea (90%).3 Even though the treatment success rate was below the target, this systematic review and meta-analysis result was good compared with the WHO report. This might be a clue indicating that Ethiopia is within the track of WHO treatment success target currently. However, a collaborative effort among healthcare providers and policy makers is crucial for achieving both national and international treatment targets.

The success rate of TB treatment in the different regions of Ethiopia was also evaluated in this study. Pooled estimate results showed that the lowest treatment success rate of 83% (95% CI 76% to 89%) was in the SNNPR region of Ethiopia23 26 28 34–36 44 and the highest success rate was in Addis Ababa (capital city of Ethiopia), that is, 93% (95% CI 90% to 95%).22 29 49 53This might be due to the differences in the quality of healthcare facilities, the health-seeking behaviour/awareness/of the population towards TB in each region, the emphasis given by regional governments and policy makers towards TB control programmes, and so on.57 58 Therefore, close supervision of each TB control programme is required to achieve effective nationwide TB control.

There are so many challenges stated as factors that affect TB treatment outcomes.57–59 The results of this review showed that different demographic and clinical characteristics were reported to have significant association with poor TB treatment outcome in Ethiopia.22–31 34–37 39–44 46 47 50–55 Mainly old age, HIV co-infection, retreatment cases and rural residence were most frequently identified factors associated with poor outcome of TB treatment. In the current study around 5357 patients with TB were HIV-positive. Being HIV-positive lowered the chances of successful treatment outcome. Globally, the treatment success rate of HIV-positive new and relapse TB cases was 78%3 and HIV significantly affects the overall TB treatment success rate which is reported by other similar studies done in Ethiopia, Somalia, Uzbekistan and Turkey.14 60–62 Furthermore similar studies done in Ethiopia, Finland and South Korea also reported that older age and retreatment14 were significantly associated with poor TB treatment outcome.57 63

In spite of such imperative findings, this study is not without limitations; all the included studies were observational studies; there were differences in the study design among the studies; and studies included were limited to Addis Ababa, Amhara, Oromia, SNNPR, Tigray and Afar. Therefore, interpretation of the results of this review should take into consideration of these limitations.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the success rate of drug-susceptible TB treatment in Ethiopia is below the WHO global target (90%) and there is also a discrepancy in TB treatment success rate among different regions of Ethiopia. In addition to these, HIV co-infection, older age, retreatment cases and rural residence were factors reported most frequently that had a significant association with poor outcome of TB treatment. The overall TB treatment success rate obtained in this study, which is closer to the WHO target, is an indicator of the good efforts in the country initiated against TB. In order to further improve the success rate of TB treatment, it is necessary to make a strategic plan for improving the treatment outcome in patients with TB with HIV co-infection, older patients, patients residing in rural areas and retreatment cases. Special consideration should also be given to regions that had a lower TB treatment success rate.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MAS and MBA conceptualised the research, developed the protocol, conducted the literature search, assessed potentially relevant studies for inclusion into the review, assessed the methodological quality of the included studies, independently extracted the data, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript, and wrote the final manuscript. EAM extracted the data, EAM, EAG and TMA assessed the methodological quality of the included studies, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data generated and research materials used during this systematic review and meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization, 2017. Tuberculosis, fact sheet http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/ (updated Oct 2017).

- 2. Churchyard G, Kim P, Shah NS, et al. What we know about tuberculosis transmission: an overview. J Infect Dis 2017;216:S629–S635. 10.1093/infdis/jix362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Assefa Y, Damme WV, Williams OD, et al. Successes and challenges of the millennium development goals in Ethiopia: lessons for the sustainable development goals. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000318 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ayele HT, Mourik MS, Debray TP, et al. Isoniazid prophylactic therapy for the prevention of tuberculosis in HIV infected adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142290 10.1371/journal.pone.0142290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abay SM, Deribe K, Reda AA, et al. The effect of early initiation of antiretroviral therapy in TB/HIV-coinfected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2015;14:560–70. 10.1177/2325957415599210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Datiko DG, Yassin MA, Theobald SJ, et al. Health extension workers improve tuberculosis case finding and treatment outcome in Ethiopia: a large-scale implementation study. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000390 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Keshavjee S, Farmer PE. Tuberculosis, drug resistance, and the history of modern medicine. N Engl J Med 2012;367:931–6. 10.1056/NEJMra1205429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tiberi S, Buchanan R, Caminero JA, et al. The challenge of the new tuberculosis drugs. La Presse Médicale 2017;46:e41–51. 10.1016/j.lpm.2017.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vasava MS, Bhoi MN, Rathwa SK, et al. Drug development against tuberculosis: past, present and future. Indian J Tuberc 2017;64:252–75. 10.1016/j.ijtb.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ma Z, Lienhardt C, McIlleron H, et al. Global tuberculosis drug development pipeline: the need and the reality. Lancet 2010;375:2100–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60359-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Food, Medicine and Healthcare Administration and Control Authority of Ethiopia. Standard Treatment Guidelines for General Hospital. 3rd edn Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stop TB Partnership. The paradigm shift, Global Plan to End TB, 2016–2020. Geneva: Switzerland: WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eshetie S, Gizachew M, Alebel A, et al. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes in Ethiopia from 2003 to 2016, and impact of HIV co-infection and prior drug exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194675 10.1371/journal.pone.0194675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis–2013 revision. Geneva, 2016. (updated Dec 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Federal Ministry of Health. Guidelines for clinical and programmatic management of TB, TB/HIV and Leprosy in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa (ON): Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, et al. Are healthcare workers' intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13:154 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. StataCorp L. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14 computer program: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods 2006;11:193–206. 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ali SA, Mavundla TR, Fantu R, et al. Outcomes of TB treatment in HIV co-infected TB patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional analytic study. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:640 10.1186/s12879-016-1967-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Asres A, Jerene D, Deressa W. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes of six and eight month treatment regimens in districts of Southwestern Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:653 10.1186/s12879-016-1917-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Belayneh M, Giday K, Lemma H. Treatment outcome of human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis co-infected patients in public hospitals of eastern and southern zone of Tigray region, Ethiopia. Braz J Infect Dis 2015;19:47–51. 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berhe G, Enquselassie F, Aseffa A. Treatment outcome of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012;12:537 10.1186/1471-2458-12-537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dangisso MH, Datiko DG, Lindtjørn B. Trends of tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes in the Sidama Zone, southern Ethiopia: ten-year retrospective trend analysis in urban-rural settings. PLoS One 2014;9:e114225 10.1371/journal.pone.0114225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Endris M, Moges F, Belyhun Y, et al. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at enfraz health center, northwest ethiopia: a five-year retrospective study. Tuberc Res Treat 2014;2014:1–7. 10.1155/2014/726193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gebrezgabiher G, Romha G, Ejeta E, et al. Treatment Outcome of Tuberculosis Patients under Directly Observed Treatment Short Course and Factors Affecting Outcome in Southern Ethiopia: A Five-Year Retrospective Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150560 10.1371/journal.pone.0150560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hailu D, Abegaz WE, Belay M. Childhood tuberculosis and its treatment outcomes in Addis Ababa: a 5-years retrospective study. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:61 10.1186/1471-2431-14-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mekonnen D, Derbie A, Mekonnen H, et al. Profile and treatment outcomes of patients with tuberculosis in Northeastern Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Afr Health Sci 2016;16:663–70. 10.4314/ahs.v16i3.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Melese A, Zeleke B, Ewnete B. Treatment Outcome and Associated Factors among Tuberculosis Patients in Debre Tabor, Northwestern Ethiopia: A Retrospective Study. Tuberc Res Treat 2016;2016:1–8. 10.1155/2016/1354356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moges B, Amare B, Yismaw G, et al. Prevalence of tuberculosis and treatment outcome among university students in Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:15:15 10.1186/s12889-015-1378-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mekonnen D, Derbie A, Desalegn E. TB/HIV co-infections and associated factors among patients on directly observed treatment short course in Northeastern Ethiopia: a 4 years retrospective study. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:666 10.1186/s13104-015-1664-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muñoz-Sellart M, Yassin MA, Tumato M, et al. Treatment outcome in children with tuberculosis in southern Ethiopia. Scand J Infect Dis 2009;41(6-7):450–5. 10.1080/00365540902865736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Muñoz-Sellart M, Cuevas LE, Tumato M, et al. Factors associated with poor tuberculosis treatment outcome in the Southern Region of Ethiopia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2010;14:973–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shargie EB, Lindtjørn B. DOTS improves treatment outcomes and service coverage for tuberculosis in South Ethiopia: a retrospective trend analysis. BMC Public Health 2005;5:62 10.1186/1471-2458-5-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sinshaw Y, Alemu S, Fekadu A, et al. Successful TB treatment outcome and its associated factors among TB/HIV co-infected patients attending Gondar University Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: an institution based cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:132 10.1186/s12879-017-2238-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tefera F, Dejene T, Tewelde T. Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients at Debre Berhan Hospital, Amhara Region, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2016;26:65–72. 10.4314/ejhs.v26i1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tesfahuneygn G, Medhin G, Legesse M. Adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment and treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients in Alamata District, northeast Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:503 10.1186/s13104-015-1452-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tessema B, Muche A, Bekele A, et al. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at Gondar University Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. A five--year retrospective study. BMC Public Health 2009;9:371 10.1186/1471-2458-9-371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zenebe Y, Adem Y, Mekonnen D, et al. Profile of tuberculosis and its response to anti-TB drugs among tuberculosis patients treated under the TB control programme at Felege-Hiwot Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2016;16:688 10.1186/s12889-016-3362-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zenebe T, Tefera E. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and associated factors among smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Afar, Eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Braz J Infect Dis 2016;20:635–6. 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gebreegziabher SB, Bjune GA, Yimer SA. Total delay is associated with unfavorable treatment outcome among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in west gojjam zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159579 10.1371/journal.pone.0159579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Asebe G, Dissasa H. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at Gambella Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: three-year retrospective study. J Inf Dis Ther 2015;03 10.4172/2332-0877.1000211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Belayneh T, Kassu A, Tigabu D, et al. Characteristics and treatment outcomes of "transfer-out" pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Gondar, Ethiopia. Tuberc Res Treat 2016;2016:1–6. 10.1155/2016/1294876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Birlie A, Tesfaw G, Dejene T, et al. Time to death and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Dangila Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144244 10.1371/journal.pone.0144244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ejeta E, Chala M, Arega G, et al. Outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed short course treatment in western Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Ctries 2015;9:752–9. 10.3855/jidc.5963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gebremariam G, Asmamaw G, Hussen M, et al. Impact of HIV status on treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients registered at Arsi Negele Health Center, Southern Ethiopia: a six year retrospective study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153239 10.1371/journal.pone.0153239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Getahun B, Ameni G, Medhin G, et al. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Braz J Infect Dis 2013;17:521–8. 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamusse SD, Demissie M, Teshome D, et al. Fifteen-year trend in treatment outcomes among patients with pulmonary smear-positive tuberculosis and its determinants in Arsi Zone, Central Ethiopia. Glob Health Action 2014;7:25382 10.3402/gha.v7.25382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ketema KH, Raya J, Workineh T, et al. Does decentralisation of tuberculosis care influence treatment outcomes? The case of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Public Health Action 2014;4(Suppl 3):13–17. 10.5588/pha.14.0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Balcha TT, Skogmar S, Sturegård E, et al. Outcome of tuberculosis treatment in HIV-positive adults diagnosed through active versus passive case-finding. Glob Health Action 2015;8:27048 10.3402/gha.v8.27048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tilahun G, Gebre-Selassie S. Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculosis in Addis Ababa: a five-year retrospective analysis. BMC Public Health 2016;16:612 10.1186/s12889-016-3193-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Workneh MH, Bjune GA, Yimer SA. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality during tuberculosis treatment: a prospective cohort study among tuberculosis patients in South-Eastern Amahra Region, Ethiopia. Infect Dis Poverty 2016;5:22 10.1186/s40249-016-0115-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Amante TD, Ahemed TA. Risk factors for unsuccessful tuberculosis treatment outcome (failure, default and death) in public health institutions, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J 2015;20:247 doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.247.3345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. World Health Organization(WHO). Global tuberculosis report 2014: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vasankari T, Holmström P, Ollgren J, et al. Risk factors for poor tuberculosis treatment outcome in Finland: a cohort study. BMC Public Health 2007;7:291 10.1186/1471-2458-7-291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive resistance to second-line drugs--worldwide, 2000-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55:301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Laserson KF, Wells CD. Reaching the targets for tuberculosis control: the impact of HIV. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:377–81. 10.2471/BLT.06.035329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ali MK, Karanja S, Karama M. Factors associated with tuberculosis treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients attending tuberculosis treatment centres in 2016-2017 in Mogadishu, Somalia. Pan Afr Med J 2017;28 doi:10.11604/pamj.2017.28.197.13439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sengul A, Akturk UA, Aydemir Y, et al. Factors affecting successful treatment outcomes in pulmonary tuberculosis: a single-center experience in Turkey, 2005-2011. J Infect Dev Ctries 2015;9:821–8. 10.3855/jidc.5925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gadoev J, Asadov D, Tillashaykhov M, et al. Factors associated with unfavorable treatment outcomes in new and previously treated tb patients in uzbekistan: a five year countrywide study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0128907 10.1371/journal.pone.0128907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Choi H, Lee M, Chen RY, et al. Predictors of pulmonary tuberculosis treatment outcomes in South Korea: a prospective cohort study, 2005-2012. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:360 10.1186/1471-2334-14-360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022111supp001.pdf (189.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022111supp002.pdf (437.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022111supp003.pdf (212.2KB, pdf)