Abstract

Objectives

The South Korean government has recently implemented policies to prevent suicide. However, there were few studies examining the recent changing trends in suicide rates. This study aims to examine the changing trends in suicide rates by time and age group.

Design

A descriptive study using nationwide mortality rates.

Setting

Data on the nationwide cause of death from 1993 to 2016 were obtained from Statistics Korea.

Participants

People living in South Korea.

Interventions

Implementation of national suicide prevention policies (first: year 2004, second: year 2009).

Primary outcome measures

Suicide was defined as ‘X60-X84’ code according to the ICD-10 code. Age-standardised suicide rates were estimated, and a Joinpoint regression model was applied to describe the trends in suicide rate.

Results

From 2010 to 2016, the suicide rates in South Korea have been decreasing by 5.5% (95% CI −10.3% to −0.5%) annually. In terms of sex, the suicide rate for men had increased by 5.0% (95% CI 3.6% to 6.4%) annually from 1993 to 2010. However, there has been no statistically significant change from 2010 to 2016. For women, the suicide rate had increased by 7.5% (95% CI 6.3% to 8.7%) annually from 1993 to 2009, but since 2009, the suicide rate has been significantly decreasing by 6.1% (95% CI −9.1% to −3.0%) annually until 2016. In terms of the age group, the suicide rates among women of almost all age groups have been decreasing since 2010; however, the suicide rates of men aged between 30 and 49 years showed continuously increasing trends.

Conclusion

Our results showed that there were differences in the changing trends in suicide rate by sex and age groups. Our finding suggests that there was a possible relationship between implementation of second national suicide prevention policies and a decline in suicide rate.

Keywords: mortality, social and political issues, prevention, Republic Of Korea

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our findings show that efforts to reduce suicide at the national level may lead to a decline in suicide rates especially among elderly people through natural experiment.

Another finding of our study is that suicide rates in men in their 30s and 40s are continuing to increase, suggesting that a different suicide prevention strategy may be necessary in South Korea.

Because this study is a descriptive epidemiological study, it is difficult to know exactly which policies have reduced suicide rates in which age group.

Improved accuracy of statistics on the causes of death may affect to changes in suicide rates.

Introduction

Suicide is a major public health issue, with an estimated 788 000 deaths every year according to the WHO statistics.1 The WHO established the Mental Health Action 2013–2020 plan to implement a national, multisectoral promotion and prevention programme for promoting mental health and reducing suicide rates of each country by 10% until 2020.2 Especially, the developed countries in East Asia have relatively high mortality rates due to suicide.3 Among these countries, suicide in South Korea is a serious health problem because the suicide rate in South Korea in 2013 (28.5 per 100 000 person-years) was 2.4 times higher than the average suicide rates of other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and South Korea has been ranked top among the OECD countries in terms of suicide rates in the last 10 years.4 In addition, suicide was the most common cause of death in young people aged between 10 and 39 years, and it was the second-most common cause of death among adults aged 40–59 years in 2016 in South Korea.5

South Korea implemented the national suicide prevention programme in the early 2000s.6 This national suicide prevention programme includes both high-risk group-oriented monitoring and prevention of suicide and suicide prevention programme for general population such as media campaign.7 However, there was a few studies to examine the trends in suicide rates by sex and age group with regard to the national suicide prevention policies in South Korea. Therefore, this study aimed to describe the changing trends in suicide rate by sex and age group in South Korea and exploring the potential effects of implementation of the national suicide prevention policies.

Method

Study participants

The cause of death statistics is a reliable source of data on how the causes of death have changed because of socioeconomic changes and public health developments; it also provides comprehensive information to plan and prioritise healthcare policies. The number of deaths due to suicide and the corresponding midyear population counts from 1993 to 2016 were obtained from Statistic Korea (available from http://kosis.kr/). The Statistic Korea used the estimated population as the denominator for mortality rates before year 1993. After 1993, Statistic Korea used the midyear population based on resident registration number as the denominator for mortality rates. In addition, the cause of death data before 1993 is less accurate, therefore, we selected the suicide rates from 1993 to 2016. The code assigned to the cause of death due to suicide was ‘X60-X84’ according to the ICD-10 code.

Patient and public involvement

We did not contact with patients and our study was not directly associated with patients, because we used the administrative secondary data—the cause of death data from Statistic Korea. There was no role or participation of patients in our study.

National suicide prevention programme

Information regarding the timing and implementation of the national suicide prevention policy in South Korea were obtained from relevant government data and expert consultants. Initially, the timing and details of the national suicide prevention policy were obtained from the national knowledge information system (https://nkis.re.kr:4445/main.do) and publications from Korea Suicide Prevention Centre.7–10 The contents and details obtained from these websites were confirmed after review by the experts and staffs of Korea Suicide Prevention Centre.6–12

Ethics statement

The study protocol was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University (IRB No.KHSIRB-17–086). Our study was exempted from review because it was not an experimental trial, which required contacting the patients, and our study did not include personal identifiable information.

Statistical analysis

To describe the baseline characteristics of people who die due to suicide, the number of deaths was presented for each 6 year period (1993–1998/1999–2004/2005–2010/2011–2016) from 1993 to 2016. The χ2 test was used to test the differences in the distribution of death due to suicide by sex and age groups. To describe the changes in suicide rates by time period, the age-standardised suicide rates of suicide were calculated. The midyear Korean population in 2005 was used as the standard population for age-standardised suicide rates. Age-specific suicide rates were applied to the corresponding 5-year age group of the standard population. The sum of expected deaths for each 5 year age group was calculated, and the age-standardised suicide rates were calculated by dividing the sum of expected deaths by the total number of standard population. We used the Joinpoint regression programme to know whether there were changes in trends in mortality rates. Joinpoint statistical software was developed by the National Cancer Institute in the United States. Joinpoint regression modelling was used to test the trends in age-standardised suicide rates for suicide and detect significant changes over time to fit a better multi-segmented model compared with a simple linear model using a Monte Carlo permutation method.13 Further, it could detect point where significant change in rates over time. The trends in rates were summarised as annual percentage changes (APCs) and their 95% CIs.

P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used SPSS (V.23.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA) and R software (V.3.1.1, Vienna, Austria) and Joinpoint Regression Programme software (V.4.1.1, Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Programme, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The total number of deaths in South Korea from 1993 to 2016 was 6007 678 (table 1). Of these, the total number of deaths due to suicide was 249 085 (4.2%). Of the deaths due to suicide, 169 963 (68.2%) were men and 79 122 (31.8%) were women. In terms of the time period, South Korea had the highest number of deaths from suicide (n=15 906) in 2011 and the highest age-standardised suicide rate from suicide (29.5 per 100 000 person-years) in 2009 (table 2). After 2011, the number of deaths and age-standardised suicide rates due to suicide decreased until 2016. The number of deaths due to suicide in 2011–2016 was 2.5 times higher than that in 1993–1998. According to the age groups, the proportion of deaths due to suicide in children and adolescents aged between 10 years and 19 years had decreased from 1993 to 1998 to 2011–2016, whereas the proportion of elderly aged more than 70 years had increased during the same time period (p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of suicide by sex and age group

| Characteristics | Overall | Year | P values* | |||

| 1993–1998 | 1999–2004 | 2005–2010 | 2011–2016 | |||

| Total number of deaths† | 6007 678 | 1445 819 | 1467 088 | 1479 483 | 1615 288 | |

| Number of deaths due to suicide‡ | 2 49 085 (4.15%) | 34 064 (2.36%) | 51 413 (3.50%) | 78 674 (5.32%) | 84 934 (5.26%) | |

| Sex§ | <0.0001 | |||||

| Men | 169 963 (68.23%) | 23 733 (69.67%) | 35 619 (69.28%) | 51 525 (65.49%) | 59 086 (69.57%) | |

| Women | 79 122 (31.77%) | 10 331 (30.33%) | 15 794 (30.72%) | 27 149 (34.51%) | 25 848 (30.43%) | |

| Age group¶ | <0.0001 | |||||

| 10–19 years | 7712 (3.1%) | 2338 (6.9%) | 1629 (3.2%) | 1936 (2.5%) | 1809 (2.1%) | |

| 20–29 years | 29 988 (12.0%) | 7108 (20.9%) | 6306 (12.3%) | 9097 (11.6%) | 7477 (8.8%) | |

| 30–39 years | 43 015 (17.3%) | 7800 (22.9%) | 9654 (18.8%) | 12 575 (16.0%) | 12 986 (15.3%) | |

| 40–49 years | 47 796 (19.2%) | 5815 (17.1%) | 10 468 (20.4%) | 14 938 (19.0%) | 16 575 (19.5%) | |

| 50–59 years | 41 960 (16.8%) | 4701 (13.8%) | 7705 (15.0%) | 12 593 (16.0%) | 16 961 (20.0%) | |

| 60–69 years | 33 214 (13.3%) | 3259 (9.6%) | 7441 (14.5%) | 11 615 (14.8%) | 10 899 (12.8%) | |

| 70–79 years | 29 654 (11.9%) | 2142 (6.3%) | 5389 (10.5%) | 10 337 (13.1%) | 11 786 (13.9%) | |

| ≥80 years | 15 661 (6.3%) | 873 (2.6%) | 2800 (5.5%) | 5557 (7.1%) | 6431 (7.6%) | |

*The χ2 test was used to test the differences in the number of deaths by sex and age group.

†Total number of deaths present the overall cause of deaths.

‡The denominator for percentage of number of deaths due to suicide was total number of deaths.

§The number and percentage of death due to suicide by sex and age group were presented among people aged ≥10 years.

¶The number and percentage of deaths due to suicide by sex and age group were presented among people aged ≥10 years.

Table 2.

The number of deaths from suicide, suicide rates from 1993 to 2016 in South Korea

| Year | Population | Number of suicide deaths | Age-standardised suicide rate* |

| 1993 | 44 752 157 | 4208 | 10.7 |

| 1994 | 45 208 726 | 4277 | 10.7 |

| 1995 | 45 637 184 | 4930 | 12.1 |

| 1996 | 46 062 143 | 5959 | 14.4 |

| 1997 | 46 475 163 | 6068 | 14.5 |

| 1998 | 46 837 620 | 8622 | 20.4 |

| 1999 | 47 163 425 | 7056 | 16.5 |

| 2000 | 47 534 117 | 6444 | 14.9 |

| 2001 | 47 877 049 | 6911 | 15.7 |

| 2002 | 48 125 745 | 8612 | 19.2 |

| 2003 | 48 308 386 | 10 898 | 23.7 |

| 2004 | 48 485 314 | 11 492 | 24.6 |

| 2005 | 48 683 040 | 12 011 | 25.1 |

| 2006 | 48 887 027 | 10 653 | 21.7 |

| 2007 | 49 130 354 | 12 174 | 24.3 |

| 2008 | 49 404 648 | 12 858 | 25.1 |

| 2009 | 49 656 756 | 15 412 | 29.5 |

| 2010 | 49 879 812 | 15 566 | 29.1 |

| 2011 | 50 111 476 | 15 906 | 29.1 |

| 2012 | 50 345 325 | 14 160 | 25.3 |

| 2013 | 50 558 952 | 14 427 | 25.3 |

| 2014 | 50 763 158 | 13 836 | 24.0 |

| 2015 | 50 951 719 | 13 513 | 22.8 |

| 2016 | 51 112 972 | 13 092 | 21.9 |

Data were obtained from Statistics Korea (available from: http://kosis.kr/)

*Age-standardised rates were expressed per 100 000 people and the Korean midyear population in year 2005 was used for age-standardisation.

Trends in overall suicide rates

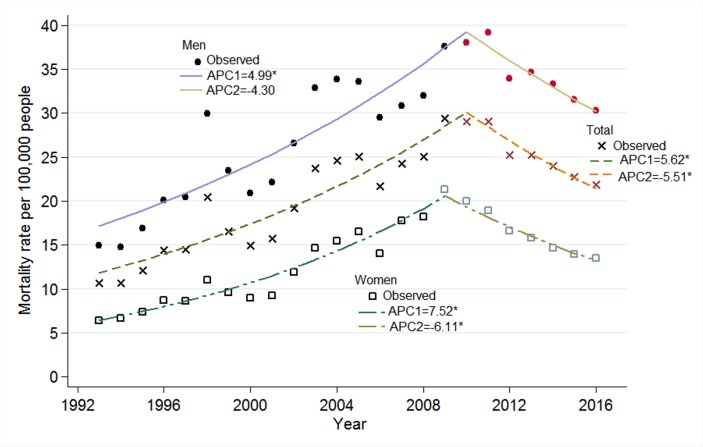

According to the Joinpoint regression model, the mortality rate from suicide had increased by 5.6% (95% CI 4.4% to 6.9%) annually from 1993 to 2010 (figure 1). After 2010, the suicide rate had declined by 5.5% (95% CI −10.3% to −0.5%) annually until 2016. In terms of sex, suicide rate for men had increased by 5.0% (95% CI 3.6% to 6.4%) annually from 1993 to 2010. After 2010, suicide rate for men shown decreasing trends (APC=−4.3%, 95% CI −9.8% to 1.6%), although it was not statistically significant (p=0.14). Similarly, the suicide rates for women had increased by 7.5% (95% CI 6.3% to 8.7%) annually from 1993 to 2009. Following that, suicide rates for women showed a significant decreasing trend (APC=−6.1%, (95% CI −9.1% to −3.0%)).

Figure 1.

Trends in age-standardised suicide rates in South Korea, 1993–2016. APC, annual percentage change The age-standardised suicide rates are presented as suicide death cases per 100 000 people using the Korean midyear population in 2005 as the standard population. Joinpoint regression analysis was used to determine whether there were significant changes in trends in age-standardised suicide rates for the period between 1993 and 2016. *p<0.05.

Trends in suicide rates for men by age group

Joinpoint regression analysis was performed by sex and age group. Suicide rates for men increased with age (table 3). The suicide rate of adolescents aged 10–19 years is relatively low, ranging from 3 to 7 people per 1 00 000 persons. The suicide rate of adolescents aged 10–19 years has been increasing annually by 2.8% since 2001. Although there was no statistically significant change in suicide rate of young adults aged 20–29 years, the rates showed increasing trends from 2006 to 2010, and it has tended to decrease since 2010. The suicide rate of men aged 30–39 years showed a significant annual increase of 3.1% from 1993 to 2016. For men aged 40–49 years, the suicide rate dramatically increased by 15.6% annually from 1993 to 1998. Since 1998, the increasing trend in the suicide rate has attenuated among men aged 40–49 years (APC=1.9% (95% CI 0.9% to 2.9%)). The suicide rate for men aged 50–59 years has increased by 8.0% from 1993 to 2004. However, there has been no significant increase since 2004. For men aged 60–69 years, there was a statistically significant increase in suicide rate by 10.7% increase each year between 1993 and 2005; however, there has been a decreasing trend since 2005. The suicide rate for men aged 70–79 years had increased by 12.9% annually from 1993 to 2004 but has been decreasing by 7.5% annually since 2011. For men aged 80 years and above, the suicide rate had increased by 9.2% annually between 1993 and 2000. There was no significant change in the suicide rate for men from 2000 to 2010. Since 2010, the suicide rate has been decreasing annually by 6.2%.

Table 3.

Joinpoint regression analysis for suicide rates from 1993 to 2016 in Koreans by age group

| Categories | Suicide rate | Trend 1 | Trend 2 | Trend 3 | Trend 4 | |||||

| 1993 | 2016 | Years | APC (95% CI) | Years | APC (95% CI) | Years | APC (95% CI) | Years | APC (95% CI) | |

| Men | ||||||||||

| 10–19 years old | 5.35 | 5.57 | 1993–1998 | 4.8% (−5.2% to 16.0%) | 1998–2001 | −14.7% (−48.4% to 40.9%) | 2001–2016 | 2.8% (0.5% to 5.2%)* | ||

| 20–29 years old | 14.44 | 19.91 | 1993–2006 | 0.5% (−1.6% to 2.7%) | 2006–2010 | 12.1% (−7.3% to 35.6%) | 2010–2016 | −5.8% (−11.7% to 0.5%) | ||

| 30–39 years old | 15.53 | 31.32 | 1993–2016 | 3.0% (2.1% to 4.0%)* | ||||||

| 40–49 years old | 18.39 | 42.34 | 1993–1998 | 15.6% (3.0% to 29.8%)* | 1998–2016 | 1.9% (0.8% to 2.9%)* | ||||

| 50–59 years old | 23.92 | 48.32 | 1993–2004 | 8.0% (4.6% to 11.5%)* | 2004–2016 | −0.2% (−1.9% to 1.6%) | ||||

| 60–69 years old | 26.58 | 55.74 | 1993–2005 | 10.7% (7.8% to 13.7%)* | 2005–2016 | −3.6% (−5.5% to −1.7%)* | ||||

| 70–79 years old | 34.38 | 90.32 | 1993–2004 | 12.9% (9.9% to 16.0%)* | 2004–2011 | 1.2% (−2.2% to 4.7%) | 2011–2016 | −7.5% (−11.2% to −3.5%)* | ||

| ≥80 years old | 41.74 | 150.52 | 1993–2000 | 9.2% (2.3% to 16.7%)* | 2000–2003 | 29.7% (−3.3% to 74.0%) | 2003–2010 | 0.9% (−2.4% to 4.3%) | 2010–2016 | −6.2% (−8.8% to −3.6%)* |

| Women | ||||||||||

| 10–19 years old | 3.01 | 4.15 | 1993–1998 | 14.4% (5.2% to 24.3%)* | 1998–2001 | −21.4% (−47.0% to 16.6%) | 2001–2009 | 8.0% (2.3% to 14.0%)* | 2009–2016 | −5.1% (−10.0% to −0.0%)* |

| 20–29 years old | 6.97 | 12.46 | 1993–1998 | 10.0% (−1.3% to 22.5%) | 1998–2001 | −14.8% (−47.7% to 38.8%) | 2001–2008 | 19.9% (12.0% to 28.5%)* | 2008–2016 | −9.5% (−13.3% to −5.6%)* |

| 30–39 years old | 8.07 | 17.65 | 1993–2006 | 5.0% (3.2% to 6.8%)* | 2006–2009 | 20.8% (−4.4% to 52.5%) | 2009–2016 | −5.9% (−8.9% to −2.8%)* | ||

| 40–49 years old | 7.57 | 16.47 | 1993–2010 | 6.5% (5.4% to 7.7%)* | 2010–2016 | −3.3% (−6.8% to 0.3%) | ||||

| 50–59 years old | 5.47 | 16.35 | 1993–2010 | 6.6% (5.0% to 8.2%)* | 2010–2016 | −5.5% (−8.6% to 0.0%) | ||||

| 60–69 years old | 9.10 | 14.65 | 1993–2005 | 9.4% (7.5% to 11.4%)* | 2005–2010 | 0.7% (−5.4% to 7.3%) | 2010–2016 | −8.7% (−11.9% to −5.5%)* | ||

| 70–79 years old | 12.19 | 26.50 | 1993–2004 | 13.5% (11.0% to 16.1%)* | 2004–2011 | −1.5% (−4.6% to 1.7%) | 2011–2016 | −9.9% (−13.9% to −5.8%)* | ||

| ≥80 years old | 17.21 | 45.73 | 1993–2004 | 18.0% (14.3% to 21.8%)* | 2004–2011 | −1.3% (−5.1% to 2.5%) | 2011–2016 | −11.5% (−15.8% to −6.9%)* | ||

Joinpoint regression model is used to test that age-standardised rates have significantly changed. The trends in suicide mortality rates were summarised as APC.

Age-standardised rates were expressed per 100 000 men and the Korean midyear population in year 2005 was used for age-standardisation.

*P value<0.05

APC, annual percentage change.

Trends in suicide rates for women by age group

Table 3 shows the suicide rate for women by age group. The suicide rate of adolescents aged 10–19 years is relatively low, and the trends of suicide rates are similar to that in the twenties. Suicide rates in women aged 20–29 years had increased by 19.9% annually from 2001 to 2008. Since 2008, suicide rate for women aged 20–29 years has decreased by 9.5% annually. The suicide rate of women aged 30–39 years showed a significant annual increase of 5.0% from 1993 to 2006, whereas the suicide rates tended to decrease by 5.9% annually from 2009 to 2016. For women aged 40–49 years, the suicide rate had increased by 6.5% annually from 1993 to 2010. Since 2010, there was no significant change in the suicide rate. The suicide rate for women aged 50–59 years had increased by 6.6% from 1993 to 2010. After 2010, the suicide rates for women aged 50–59 years showed a decreasing trend (APC=−5.5% (95% CI −8.6% to 0.0%)). For women aged 60–69 years, there was a statistically significant increase in the suicide rate with 9.4% increase each year from 1993 to 2005; however, there has been a significant decreasing trend since 2010 (APC=−8.7% (95% CI −11.9% to −5.5%)). The suicide rate for women aged 70–79 years increased by 13.5% annually from 1993 to 2004 but has decreased significantly by 9.9% annually since 2011. For women aged 80 years and above, the suicide rates had dramatically increased by 18.0% annually from 1993 to 2004. There was no significant change from 2004 to 2011. Since 2011, suicide rate has decreased by 11.5% annually.

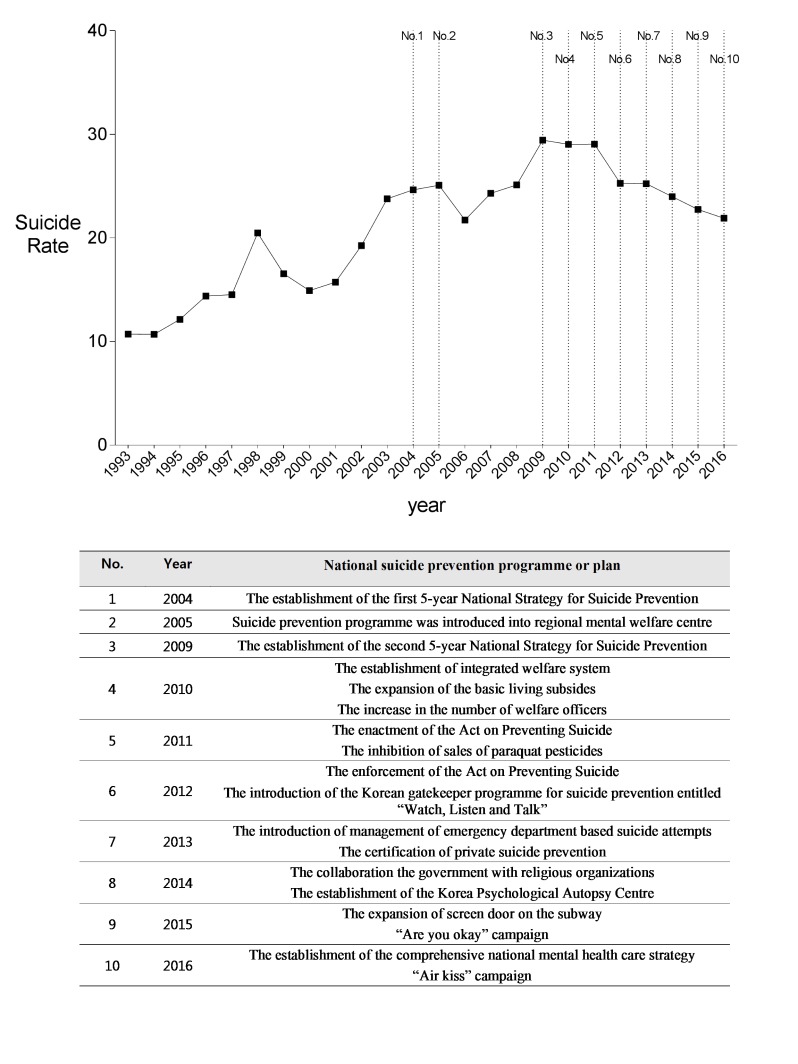

The implementation of the national suicide prevention programme in South Korea

The first step of the national suicide prevention programme was the establishment of the first 5 year National Strategy for Suicide Prevention in 2004 (figure 2). Based on this, a suicide prevention programme was introduced in 2005 at regional mental health centres which were public community infrastructures for mental health. Following this, the second 5-year National Strategy for Suicide Prevention was implemented in 2009. Based on this programme, a separate budget was newly proposed and executed. In 2010, a screen door was expanded to prevent suicide on the subway. In 2011, the Act for the Prevention of Suicide was passed, the Korea Suicide Prevention Centre was established and the sales of paraquat pesticides were prohibited. The Act for the Prevention of Suicide was enforced in 2012, and the Korean gatekeeper training programme for suicide prevention entitled ‘Watch, Listen and Talk’ was introduced to the general population in South Korea. In 2013, an emergency department-based suicide attempt survivor management programme was implemented, and the Korea Suicide Prevention Centre along with Journalists Association of Korea announced the recommendation for media reporting of suicide. In addition, the government authenticated the private suicide prevention programme to disseminate the evidence-based suicide prevention programme. In 2014, the government collaborated with religious organisations to increase the participation rates of general population in the national suicide programme. The Korea Psychological Autopsy Centre was established to understand the causes of suicide deaths better.

Figure 2.

Implementation of the National Suicide Prevention Programme and Plan. The age-standardised suicide rates are presented as a connected line from 1993 to 2016 are presented as a connected line. Each number represents the year in which the major events related to the National Suicide Prevention programme or Plan occurred.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the trends of suicide rate in South Korea by sex and age group and explore these suicide rate changes according to the timing of suicide prevention policies implemented by the Korean government. This study found that the overall suicide rate in South Korea had tended to decline since 2010. However, when analysed by sex and age, the suicide rate trends showed differences according to the sex and age groups. While women’s suicide rate has decreased in all age groups since 2010, the suicide rate of men aged between 30 and 49 years is still on the rise. Our findings were consistent with the study findings of Matsubayashi et al.14 They showed that a national level of suicide prevention intervention was an effective way to reduce suicide rate except for working-age adults in 21 OECD countries.14

Trend in suicide rate between 1993 and 2004/2005

From 1993 to 2016, the suicide rates tended to change at two points in time. The suicide rates of South Korea have increased continuously from 1993 to 2010. According to the study by Kwon et al, the recent increase in suicide during 1986–2005 was mainly attributed to increase in suicide in elderly people.15 The rapid social change such as the increasing tendency of smaller family size may make the elderly feel isolated. In addition, insufficient social security system and economical problem may lead to an increase in suicide rates in the elderly.15 However, suicide rate of young people aged less than 45 years old have also increased significantly.15 The rising economic inequality and increasing unemployment rate due to economic crisis in 1997 of Korea may contribute to the increase in suicide rate among young people. In addition, the fragmentation of social integration may have weakened the social ability to overcome mental problem such as depression.15

Trends in suicide rate after 2004/2005

However, our study found that the suicide rate changed before and after 2004 and 2005. It was revealed that after 2004, an increase in the suicide rate of men and women aged 60 years or older had changed. After 2005, the suicide rate of men in their 60 s decreased by 3.6% each year and that of women in their 60 s, which had risen sharply up until 2005, no longer showed a statistically significant increase from 2005 to 2010.

During this period, Korea’s 1st national suicide prevention initiative was implemented in 2004, which included various programmes such as mental health improvement and suicide prevention, suicide prevention counselling calls, the development of a culture that respects life, treatment and post-suicide attempt management for those who attempt suicide, and suicide prevention research.12 In addition, the Mental Health Welfare Centre, a national mental health system, also implemented a regional suicide prevention programme in 2005, and the Seoul Suicide Prevention Centre was first established.16 Although the 1st suicide prevention initiative was implemented in 2004, the government did not earmark funding for the 1st suicide prevention initiative.17 In other words, this project had just added suicide prevention programme to the existing mental healthcare service without sufficient additional budgets and manpower. In addition, the scope of this policy was mainly focused on the individuals with mental disorder, and there was not sufficient consideration for social and environmental changes. For this reason, it is difficult to find the data that can precisely identify the programmes that were actually implemented among various other programmes. Nonetheless, a suicide prevention programme implemented by the Mental Health Welfare Centre mainly focused on management via phone calls, and it has been applied since 2005 without additional funding. Previous studies reported that interventions and management based on phone calls were effective for the suicide prevention of the elderly,18 19 and in this regard, changes in the suicide rate mostly found among those aged 60 years or older can be attributed to the effect of phone-based interventions.20 These changes in the suicide rate, however, were found to be not a statistically significant decline in the suicide rate overall but a change in the increasing trend of the suicide rate.

Trends in suicide rates among middle-aged people between 2004/2005 and 2010

On the other hands, suicide rates have continuously increased from 2004/2005 to 2010 among men aged 30–49 years old and women aged 40–59 years old. Although we could not explain the exact cause of increase in suicide rates among middle-aged men and women, high economic burden and unemployment rates after the International Monetary Fund (IMF) may have contributed to increase in suicide rates. In the United States, suicide rates among individuals aged 40–64 years old have increased from 2005 to 2010, and the external circumstances such as job, financial, and legal problems were closely associated with increased suicide among these middle-aged people.21 In the England, more suicides were observed both in men and women than expected due to the economic regression between 2008 and 2010. A study by Ben Barr et al found that about 40% of increased suicide among men were attributed to elevated unemployment during this period.22 According to the 2008 National Survey of the National statistics office, the most common causes for suicidal ideation was economic difficulties (36.2%), followed by family trouble (15.6%) and loneliness (14.4%) in South Korea.23 Especially, the proportion of suicidal ideation due to economic difficulties was the highest among people aged 40–59 years old.23

Other factors, such as changes in alcohol consumption and suicide by famous celebrities, may have affected suicide rates among middle-aged people. Indeed, age-standardised alcohol abuse disorder rates have increased from 32.7% in 2005 to 38.8% in 2009.24 In addition, Fu et al analysed the impact of suicide of Korean famous celebrities on the overall suicides rate from 2005 to 2008. After adjusting for seasonal effects, changing trends, and unemployment, significant increase of suicide cases was followed by the suicide of Korean famous celebrities.25

Trends in suicide rate after 2008/2009

Second, the suicide rate began to decline from 2008 to 2011. As of 2008 and 2009, the suicide rate for women aged 10 years to 39 years, which had increased before, began to decrease. As of 2010 and 2011, the suicide rate of women aged 40 years or older also began to decline. Furthermore, the suicide rates of men in their 20 s and those aged 70 years or older tended to decline since 2010 and 2011, respectively. In contrast, the suicide rate of men aged 30–49 years had not decreased significantly from 1993 to 2016; instead, it continued to rise during this period.

To begin with, the second national suicide prevention initiative was enacted in 2009, which consisted of the research and development of suicide prevention policy, development of a culture that respects life, suicide prevention training and nurturing of specialists, on-line counselling and harmful suicide information monitoring, and public-private partnerships for suicide prevention.12 The importance of the second suicide prevention initiative is that the national budget was allocated for suicide prevention unlike the 1st suicide prevention initiative. While this initiative could be effective in reducing the suicide rate of young women in their 10s to 30s, it would be more reasonable to consider that a series of specific events contributed to a surge in the suicide rate of young women in 2008 and 2009. The effect of a celebrity’s suicide on the suicide rate is well-known,26 27 and there were incidents of suicides among very high-profile celebrities in 2008 and 2009 in South Korea, which were reported across the country.7 Furthermore, it was reported that the effect of a celebrity’s suicide in Korea was five times higher among young women.28 Considering these results, it is a reasonable interpretation to view a reduction in the suicide rate of young women after 2009 as a decline in the suicide rate surged previously due to the effect of a series of specific events—celebrity suicides.

Some important national suicide prevention activities were carried out during the second suicide prevention initiative, such as the installation of more screen doors to prevent people from throwing themselves into the subway train29 and and a ban on the sale of paraquat pesticides.30 One of the most effective suicide prevention intervention is to restrict of assessment to lethal methods.31 Such government-led suicide prevention interventions may have contributed to the changes in the suicide rate of men in their 20 s, men aged 70 years or older, and women aged 40 years or older in 2010 and 2011. Moreover, a continuous decrease in the suicide rate since 2011 indicates that the reduction of suicide rates was attributable to the government intervention efforts. After the introduction of the national suicide prevention initiative in 2009, the community mental health centre has endeavoured to register and manage more people with severe mental disorder and people with alcoholism. Indeed, the mental health service utilisation rates among people with alcoholism has increased from 8.1% in 2008 to 12.1% in 2015.32 The registration and management rate for patients with severe mental disorder in the community mental health centre has also increased from 19.2% in 2008 to 26.4% in 2016. In addition, the government implemented an emergency department-based suicide attempt survivor management programme, announced the recommendation for media reporting of suicide in 2013.7 Indeed, the proportion of alcohol abuse and suicidal thoughts of those participated in emergency department-based suicide attempt survivor management programme has decreased by 2.9% p and 6.8% p between the first and fourth contact, respectively.33

Increase in suicide rates of men in their 30s and 40s

Nevertheless, it was found that the suicide rate of men in their 30s and 40s had continued to increase significantly from 1993 to 2016. While there was a slight slowdown in the increase of their suicide rate due to suicide prevention programmes implemented by the government, it did not result in a decrease in the suicide rate. This might suggest that the currently implemented suicide prevention programmes are not effective for men in their 30s and 40s. However, in Korea, suicide prevention policies focused on men in their 30s and 40s have not been implemented until now. In previous studies, men were reported to have a higher risk of suicide due to financial reasons than women do,34 and the risk of suicide among men arising due to the unemployment rate and economic crisis was also shown to be higher.35 36 However, the current suicide prevention policies only included the development of an office worker gatekeeper programme for men in their 30s and 40s.

Strengths and limitations of this study

When interpreting the findings of this study, the following limitations need to be considered. This study did not take account of the individual effect of a suicide prevention programme; it instead interpreted the changes in suicide rates at each point in time when such programmes were implemented. However, we cannot confirm when exactly the effect of policy was seen. This was because the data on the outcome of each individual suicide prevention programme were not available as Korea did not have a monitoring system for each individual programme, even though it implemented suicide prevention programmes quite extensively. In this regard, a monitoring system needs to be established in order to identify the policy effect on the changes in the suicide rate in Korea more accurately, and a follow-up study needs to be conducted using this system. Furthermore, the accuracy of the cause of death statistics had continued to improve, so there is a chance that an increase in the number of deaths due to suicide would have been affected by the improved accuracy of statistics on the causes of death. Despite these limitations, this study has the following strengths. This study presented the trends in the suicide rates in Korea based on statistical analysis of a 24-year period. In addition, it showed that the point in time wherein such changes in the suicide rate occurred coincided with that wherein the government-led suicide prevention programmes were implemented. Accordingly, further government-level investments and interventions should be considered to reduce the suicide rate.

Conclusion

This study showed that the suicide rate among Korean men and women has decreased since 2010, based on the causes of death statistics, which could represent the general population of South Korea. Our findings also showed that there were significant changes in trends of Korea’s suicide rate especially among elderly people after 2010 to 2011. These changes in suicide rate coincided with those when the second suicide prevention initiative enacted in 2009. In this regard, it is considered that government-level suicide prevention interventions had a potential effect on decreasing the suicide rate among elderly people, and national-level efforts are still needed in the future to reduce the increasing suicide rate of men in their 30s and 40s.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and colleagues of Korea Suicide Prevention Center for their advice and help.

Footnotes

Contributors: S-UL obtained and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. J-IP, SL, I-HO and J-MC interpreted the data and contributed to revising the manuscript. C-MO made the research design and revised the manuscript. All authors participated in the design, execution, and analysis of the results and have read and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from Kyung Hee University in 2017 (grant: KHU-20170835).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University (IRB No. KHSIRB-17-086).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data used in this study can be obtained from the homepage of Statistics Korea (http://kosis.kr/eng/).

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. Suicide data. http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide (accessed on 14 Sep 2017).

- 2. World Health Organisation. Mental health action plan 2013−2020. http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/action_plan/en/ (accessed on 14 Sep 2017).

- 3. Hendin H, Phillips MR, Vijayakumar L, et al. . Suicide and suicide prevention in Asia. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD health data 2016. https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/suicide-rates.htm (accessed 14 Sep 2017).

- 5. Statistics Korea. Cause-of-death statistics 2017. http://kosis.kr/en (accessed 14 Sep 2017).

- 6. Paik J-W, Jo S-J, Lee S, et al. . The effect of Korean standardized suicide prevention program on intervention by gatekeepers. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 2014;53:358–63. 10.4306/jknpa.2014.53.6.358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Korea Suicide Prevention Center. Suicide white book. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korea Suicide Prevention Center. Suicide white book. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Korea Suicide Prevention Center. Suicide white book. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korea Suicide Prevention Center. Suicide white book. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang HG. Social welfare delivery reform: achievements and beyond. Health and Welfare Policy Forum 2012;4:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee SY. Policy options for the improvement of suicide prevention programs. Health and Welfare Policy Forum 2015;4:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. . Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19:335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsubayashi T, Ueda M. The effect of national suicide prevention programs on suicide rates in 21 OECD nations. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:1395–400. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kwon J-W, Chun H, Cho S-il. A closer look at the increase in suicide rates in South Korea from 1986–2005. BMC Public Health 2009;9:72–80. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Mental Health and Welfare Commission. Guidelines for mental health services. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park JI, Nam YY, Lee HK, et al. . National suicide prevention plan. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Leo D, Dello Buono M, Dwyer J. Suicide among the elderly: the long-term impact of a telephone support and assessment intervention in northern Italy. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:226–9. 10.1192/bjp.181.3.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. De Leo D, Carollo G, Dello Buono M. Lower suicide rates associated with a Tele-Help/Tele-Check service for the elderly at home. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:632–4. 10.1176/ajp.152.4.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun HJ. Suicide prevention efforts for the elderly in Korea. Perspect Public Health 2016;136:269–70. 10.1177/1757913916658622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hempstead KA, Phillips JA. Rising suicide among adults aged 40-64 years: the role of job and financial circumstances. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:491–500. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A, et al. . Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e5142 10.1136/bmj.e5142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Statistics Korea. Social Survey 2008. http://kosis.kr/en (accessed on 30 Jul 2018).

- 24. Park SH, Kim CH, Kim DJ, et al. . Secular trends in prevalence of alcohol use disorder and its correlates in Korean adults: results from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 and 2009. Subst Abus 2012;33:327–35. 10.1080/08897077.2012.662209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fu KW, Chan CH. A study of the impact of thirteen celebrity suicides on subsequent suicide rates in South Korea from 2005 to 2009. PLoS One 2013;8:e53870 10.1371/journal.pone.0053870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jeong J, Shin SD, Kim H, et al. . The effects of celebrity suicide on copycat suicide attempt: a multi-center observational study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;47:957–65. 10.1007/s00127-011-0403-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Niederkrotenthaler T, Fu KW, Yip PS, et al. . Changes in suicide rates following media reports on celebrity suicide: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:1037–42. 10.1136/jech-2011-200707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ju Ji N, Young Lee W, Seok Noh M, et al. . The impact of indiscriminate media coverage of a celebrity suicide on a society with a high suicide rate: epidemiological findings on copycat suicides from South Korea. J Affect Disord 2014;156:56–61. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chung YW, Kang SJ, Matsubayashi T, et al. . The effectiveness of platform screen doors for the prevention of subway suicides in South Korea. J Affect Disord 2016;194:80–3. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cha ES, Chang SS, Gunnell D, et al. . Impact of paraquat regulation on suicide in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:470–9. 10.1093/ije/dyv304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, et al. . Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:646–59. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Korea Health Promotion Institute. Health plan 2020. http://www.khealth.or.kr/healthplan (accessed 24 Apr 2018).

- 33. Korea Suicide Prevention Center. 2013-2015 Emergency Department based post-suicidal care program report summary. http://www.spckorea.or.kr/ (accessed on 25 Jun 2018).

- 34. Lee SU, Oh IH, Jeon HJ, et al. . Suicide rates across income levels: retrospective cohort data on 1 million participants collected between 2003 and 2013 in South Korea. J Epidemiol 2017;27:258–64. 10.1016/j.je.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chang SS, Gunnell D, Sterne JA, et al. . Was the economic crisis 1997-1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time-trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1322–31. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hawton K, Arensman E, Wasserman D, et al. . Relation between attempted suicide and suicide rates among young people in Europe. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:191–4. 10.1136/jech.52.3.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.