Abstract

Purpose of review

Existential distress is well-documented among patients at end-of-life and increasingly recognized among informal caregivers. However, less is known about existential concerns among healthcare providers working with patients at end-of-life (EOL), and the impact that such concerns may have on professionals.

Recent findings

Recent literature documents five key existential themes for professionals working in EOL care: 1) opportunity for introspection; 2) death anxiety and potential to compromise patient care; 3) risk factors and negative impact of existential distress; 4) positive effects such as enhanced meaning and personal growth; and 5) the importance of interventions and self-care.

Summary

EOL work can be taxing, yet also highly rewarding. It is critical for health care providers to make time for reflection and prioritize self-care in order to effectively cope with the emotional, physical, and existential demands that EOL care precipitates.

Keywords: Health care providers, existential distress, burnout, meaning, self-care

Introduction

Existential distress is a multi-dimensional construct including personal identity, meaninglessness, hopelessness, and fear of death (1). Kissane (2) defined existential distress as the psychological turmoil individuals may experience in the face of imminent death, which threaten individuals on a physical, personal, relational, spiritual, or religious level. In patients, existential distress has been shown to lead to increased levels of depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death (3).

A small but growing body of literature documents existential distress among informal caregivers (i.e., family members, friends), including concerns regarding identity, guilt, and responsibility to care for the self (4). Less is known about the existential challenges experienced by health care providers working with patients at EOL, despite strong evidence for their experience of burden and burnout (5–7*). Maslach et al. (5) describe burnout as a feeling of continuous fatigue and a persistent doubt in one’s competency and professional vocation. For healthcare providers (HCPs) working in settings characterized by frequent death, burnout may inhibit their ability to competently perform job-related responsibilities (6**) and hence, contribute to feelings of demoralization or negative attitudes towards the patients they serve (8*, 9). Indeed, existential distress associated with involvement with patients at EOL has been implicated as a key contributor to burnout (10, 11). Concurrently, however, there is evidence that the meaning HCPs may derive from providing care for patients at EOL can serve as a protective factor and help diminish burnout (6**). For example, one study (7*) found that providing opportunities for HCPs to reflect on their experiences with and attitudes toward death and to engage in the meaning-making process was crucial for personal well-being. In light of the buffering effect of meaning-making (6**, 7*), existential distress among professional caregivers has the potential to be mitigated by early intervention. Such interventions, however, require a greater understanding of the unique existential concerns of professional caregivers. Existing studies of professional caregivers only peripherally attend to the specific existential challenges and themes of meaning that arise in the setting of providing care for patients at EOL. Therefore, the purpose of this comprehensive review was to explore the existential concerns of professional caregivers and highlight their impact on psychosocial outcomes, such as burnout.

Methods

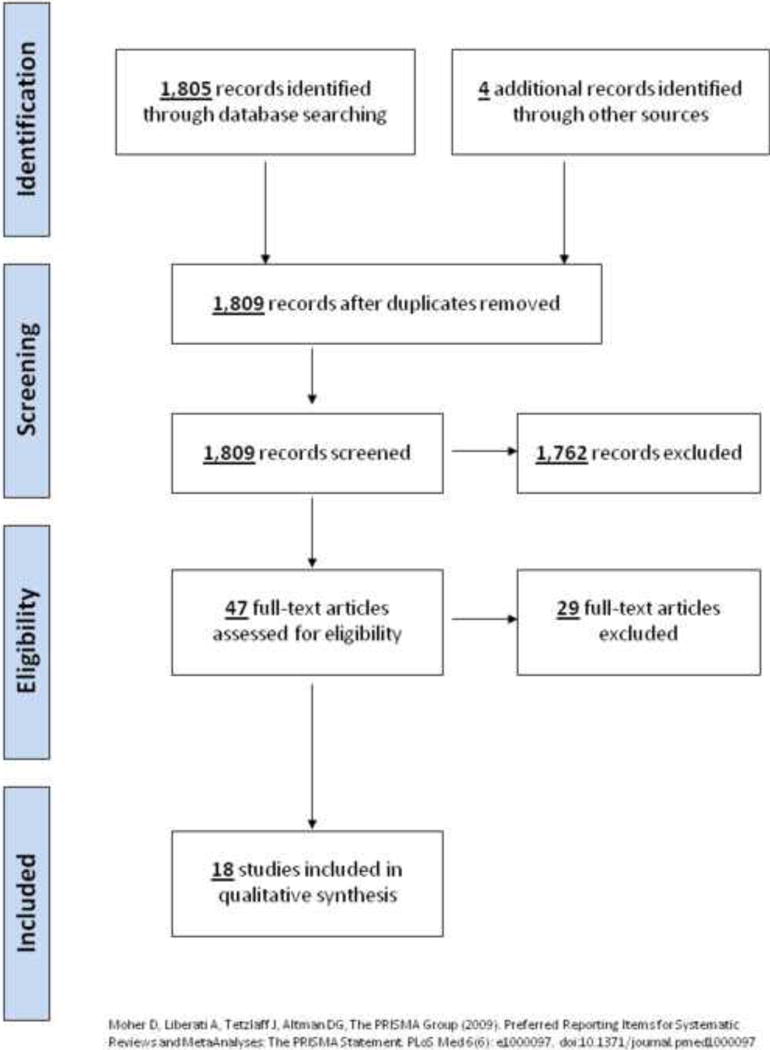

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted (July 23, 2014) in MEDLINE (via PubMed) and PsycINFO (via OVID) for articles written in all languages and published in the past five years (July 2009-July 2014) with no specified sex or publication type included (See Figure 1). Controlled vocabularies were employed and included in the search strategies, respectively. Search results were combined in a bibliographic management tool (EndNote) and duplicates were eliminated both electronically, using the capabilities in EndNote, and manually, to identify duplicates missed by the software.

Figure 1.

Identification of Articles Included for Review

The search strategy had three major components and all concepts were linked together with the AND operator: (1) existential distress and key themes/feeling of existential distress: “existential distress” OR “spiritual distress” OR meaning OR purpose OR anxiety OR alienation OR authenticity OR “religious distress” OR existence OR nothingness OR void OR estrangement OR “Existentialism”[Mesh] OR “Spirituality”[Mesh] OR “Religion”[Mesh] OR “Anxiety”[Mesh] OR “Social Alienation”[Mesh]; (2) health care professionals: professionals OR physicians OR doctors OR nurses OR psychologists OR psychiatrists OR “social workers” OR “research staff” OR “research assistants” OR “professional caregiver” OR “Health Personnel”[Mesh]; and (3) end-of-life patient care: EOL OR “end of life” OR “terminal care” OR “palliative care” OR “Terminal Care”[Mesh] OR “Palliative Care”[Mesh].

Results

Overall, the results suggest that confronting death and working with patients at EOL is a highly provocative experience that evokes existential themes amidst a wide spectrum of HCPs (9, 12). However, providers’ awareness of, reactions to, and processing of these themes are often under-recognized and variable. Failure to cope with existential distress often leads to anxiety, avoidance, burnout, and disengagement, while self-reflection and meaning-making appear to contribute to overall well-being (6–8*, 13). While working in EOL care has the potential to benefit HCPs, such benefits may also be cultivated through intervention (11, 14).

Contemplation of Existential Themes

Consistently, reviewed studies emphasized that work with the dying and bereaved elicits existential concerns and encourages introspection among HCPs (15). For example, when 17 hospice workers from California were asked about their experiences with death and dying, 88% classified their experiences as an opportunity to reflect on one’s own mortality/mortality experiences and on life experiences, as well as to gain new perspectives through introspection (15). Mak et al. (16*) conducted 15 interviews with nurses in Hong Kong and found that nurses’ work influenced how they reflect on the meaning of death and impacted their experiences of death within their own families. In Western Australia, 38 oncology health care professionals participated in semi-structured interviews and reported many emotional demands, including the need for learning to be comfortable with their own mortality (17*). Palliative medicine specialists in Australia also described being constantly reminded of their own mortality by their work (18). Palliative care providers in Canada developed wishes for how they wished to die, demonstrated increased acceptance toward death, and had a greater curiosity about an afterlife (12).

Studies reviewed also indicated that reflections on mortality served as a precursor of reflections on life experiences more generally. For example, clinicians who reflected on their own mortality were motivated to live more in the present life and cultivate a sense of spirituality (12). Furthermore, hospice care nurses who had an opportunity to reflect on their own philosophy of death and meaning in life reported an enhanced ability to have perspective on life and focus on the present (19).

Existential Distress and Death Anxiety

The construct of existential distress includes death anxiety, generally characterized as any detrimental emotions experienced due to the anticipation of being in a state in which the self does not yet exist (20). For some nurses, working with dying patients translates into higher levels of death anxiety, which has been positively correlated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (6**). Indeed, exposure to mortality cues like death and dying in nurses led to more burnout and less work engagement, regardless of the amount of exposure to these cues (21*). Moreover, a literature review of studies of death anxiety among nurses working in hospital settings concluded that attitudes toward death were significantly and inversely correlated to attitudes toward caring for dying patients (8*). Therefore, not only does death anxiety coexist alongside other existential concerns for professional caregivers, but it also has the potential to compromise patient care.

Risk Factors for Existential Distress

Several authors have acknowledged the negative emotional impact of exposure to death, (16*, 18**, 19, 22*), the severity of which is multiply determined. For instance, the closeness of a relationship and perceived responsibility for the death of a patient is linked to greater distress, which fosters emotional reactions such as depersonalization, poor quality of care, and burnout in HCPs (9). Fear of dependence, physical degradation, and not having time for family and meaningful activities, in addition to the use of avoidant coping strategies, has also been strongly correlated with burnout (13). Additionally, lack of preparedness for patient deaths, feelings of helplessness, and depersonalization due to inflexibility in the workplace also emerged as risk factors for burnout (16*).

For example, nurses in Sweden described increased feelings of exhaustion, burden, and emptiness when they perceived the situation was hopeless and especially when they closely identified with a patient or with particularly young patients (22*). Importantly, deaths that were characterized as “good deaths” allowed for meaning-making processes, whereas those characterized as “bad deaths” (described as ugly, a high degree of suffering, or absence of loved ones) were more difficult and likely to result in multiple existential stressors such as helplessness, depersonalization, and retreating from patients, which in turn could exacerbate isolation and a loss of connectedness (12, 16*, 19).

Benefits and Enhancement of Personal Growth

Concurrently, many articles highlighted the positive impact that working with dying patients had on HCPs, including a sense of personal accomplishment and fulfillment, greater meaning in life, an increased capacity to live in the present and appreciate life. In a study comparing burnout in nurses who provided EOL care to other types of care, nurses from palliative care units experienced less emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and reported a higher sense of purpose in life and personal accomplishment, and less burnout (6**). Similarly, a study conducted in Hong Kong found that nurses caring for dying patients reported that their work helped them to adapt an “easy attitude about life,” increased levels of self- and family-care, and a greater value of life (16*).

Analyses of qualitative interviews conducted with seven palliative medicine specialists highlighted coping strategies that served to protect against emotional burnout, including emphasizing the rewards of their work, meaning-making, utilizing themes of a patient’s legacy, personal growth, and living without regret (18**). Similarly, DeArmond (15) found that the majority of hospice workers interviewed described an enhanced sense of personal growth, including a greater sense of interconnectedness in their personal relationships and being part of a larger reality, in addition to decreased death anxiety and increased compassion and peace. In semi-structured interviews with six leaders in palliative care and 24 front line hospice care clinicians, HCPs indicated that working in the setting of death and dying positively influenced participants’ ability to cultivate spirituality and such beliefs into their daily lives (12). These findings were similar to those of palliative care physicians in Canada who reported that caring for the dying shaped their own capacity for self-actualization and impacted their own spirituality (23). Furthermore, in Wu & Volker’s (19) interviews with 14 Taiwanese hospice nurses, the majority reported feelings of competence and satisfaction that afforded them professional fulfillment and the ability to obtain meaning through their work.

Unique Existential Characteristics of End-of-life Health Care Providers

It is noteworthy that HCPs may choose their field because they historically considered EOL work to be meaningful, which may to some degree bias the results of the reviewed studies. When comparing HCPs working in maternity and palliative care wards, those in palliative care endorsed more creativity, spirituality, and experiences in nature as areas that serve as sources of meaning. Those more inclined toward high spirituality/religiosity may be more able to draw meaning from this type of work, and therefore choose the palliative care profession over other divisions of medicine (24*). Furthermore, in a study comparing levels of death anxiety between emergency department nurses and palliative care nurses, although both groups demonstrated moderate death anxiety (53%), emergency room nurses were more likely to exhibit avoidance toward patients at EOL. The authors describe the emergency department culture as one of life preservation, while death and dying is expected in palliative care, which may account for the discrepancy in avoidance between nurses in the two settings (25*). Finally, there may be an underlying reciprocal relationship between the care provision of dying patients and HCPs. In a study in which palliative care physicians were asked about the role of spirituality in their practices, they reported that not only did spirituality influenced practice but practice also influenced spirituality (23).

Impact of Meaning-Making Interventions and Self-Care

Working with patients at EOL is a risk factor for burnout and an opportunity for meaning-making and positive growth. Interventions that foster meaning-making as well as emotion-focused and problem-focused coping may be beneficial (7*, 18**). Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy, an intervention originally developed to address existential distress and suffering among patients at EOL (26, 27) and adapted to address similar concerns among informal cancer caregivers (28) will likely have similar benefits for HCPs. Although it is impossible to reduce the exposure to death in many settings, interventions that target death anxiety in order to reduce the emotional impact may also be helpful (21*).

For example, Fillion and colleagues (11) examined the impact of a Meaning-Centered Intervention (MCI) on existential distress among palliative care nurses. Those who received MCI reported more perceived benefits from working in palliative care, which they attributed to an increased ability to reframe experiences and use meaning-based coping strategies, finding consistency between personal and professional values, and greater spirituality. In a follow-up study with bone marrow transplant nurses who had five sessions of MCI, nurses reported enhanced connections with, and willingness to engage with suffering among, their patients and increased comfort discussing transitions from curative to palliative care. They also reported improved boundaries between professional and personal involvement, enhanced empathy around shared mortality, and elevated hope from linking suffering to meaning (14). Another study of HCPs working with patients at EOL who completed a six-day training that emphasized close personal relationships, living meaningfully, and reflecting on personal fears surrounding death and dying exhibited reduced death anxiety and burnout and increased personal well-being and professional fulfillment (13). Studies of nurses have also emphasized the need for self-care, an existential imperative, through seeking support from colleagues, taking time off from work, or engaging in formal supervision that addresses the larger issues around caring for the dying and their families to buffer distress (16*, 17*). Thus, interventions that attend to existential distress and promote self-care are necessary in assuring that such HCPs working with patients at EOL remain healthy and engaged in the field. A summary of the articles reviewed is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selection process: articles were chosen for review through database searches from the past five years (July 2009-July 2014) and screened based on relevance of article title and abstract to the review topic. Two reviewers examined full-text articles to confirm inclusion for qualitative analysis.

| Author | Design/Sample/Measures | Results | Existential Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gama et al (2014)(6) | A descriptive and correlational study; 360 nurses from the internal medicine, oncology, hematology and palliative care departments of five hospitals in the Lisbon area; socio-demographic and professional questionnaire, Maslach Burnout Inventory, Death Attitude Profile Scale, Purpose in Life Test and Adult Attachment Stale | No significant differences were found between medical departments in burnout scores. However, when compared to palliative care, the palliative care department which showed significant lesser levels of emotional exhaustion (t ¼ 2.71, p< .008) and depersonalization (t ¼ 3.07; p < .003) and higher levels of personal accomplishment |t ¼ 2.24; p < .027). | Palliative care nurses report purpose in life, personal accomplishment; burnout risk |

| Potash et al (2014)(7) | Quasi-experimental design; 69 participants enrolled in a 6-week, 18-hour art-therapy-based supervision group, 63 enrolled in a 3-day. 18-hour standard skills-based supervision group (n= 132) in Hong Kong; Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Death Attitude Profile-Revised | The art-therapy supervision based group saw significant reductions in exhaustion and death anxiety and significant increases in emotional awareness. | Emotion-focused coping; meaning-making through reflection |

| Peters-et el (2013)(8) | A review of 15 quantitative studies between 1990 and 2012 exploring nurses’ attitudes toward death | Three key themes identified were: level of death anxiety among nurses, death anxiety and attitudes towards caring for the dying, and importance of death education for performing such emotional work. Results indicated that the level of death anxiety for nurses working in general, oncology, renal, and hospice care hospitals or in community services was not high. In most cases, attitudes toward death significantly and inversely correlated to attitudes toward caring for dying patients. Younger nurses consistently demonstrated greater fear of death and more negative attitudes towards end-of-life patient care. | Death anxiety, importance of death education |

| Kutner & Kilbourn (2009)(9) | literature review, 103 articles cited | Review explores symptoms of grief in professional caregivers and potential impact of unexamined feelings on physician well-being and patient care. Reactions to patient deaths can lead to depersonalization, poor quality of care, and burnout, or conversely, professional fulfillment. Attention and educational efforts to promote communication skills, coping strategies, and personal reflection may help to address physician reactions to patient deaths. | Grief and emotional demands; burnout; importance of reflection and well-being |

| Fillion et al (2009)(11) | Randomized waiting-list group design; intervention group (n=56), waiting-list group (n=53) nurses in Canada; Job Diagnostic Survey, benefit finding instrument adaptation, Functional Assessment of Chronic illness Therapy, Shortened Profile of Mood States, ERI Questionnaire, Karasek’s Job Content Questionnaire, Nursing stress Scale, Johnson and Hall Scale, Organizational Policy, and Practices Scale, Intervention Satisfaction Questionaire | Nurses in the intervention group perceived more benefits to working in palliative care after the intervention and at follow up than the wait-list control nurses. Nurses reported satisfaction with the intervention content, but requested additional sessions and greater length of training. | Benefits of palliative care, intervention |

| Sinclair (2011)(12) | Semi-structured interviews and participant observation; n=6 leaders in palliative and hospice care, n=24 palliative and hospice care professionals in Canada | Authors found eleven specific themes, organized within three overarching categories (past, present and future). Early life experiences with death were common among participants and influenced their career path. Participants reflected on their own mortality, were motivated to live life moment to moment and cultivated a sense of spirituality. Participants also developed wishes for how they themselves would like to die, reported increased acceptance toward death, and curiosity surrounding an afterlife. | Reflection; living in the present; death acceptance; after life |

| Melo & Oliver (2011)(13) | Mixed methods approach; 150 heath care workers in Portugal who care for the dying enrolled in a six-day training course (n=35 palliative care, n=65 other settings), 26 non-palliative care health care workers used as control group; Maslach Burnout Inventory, Psych Tests Aim Inc, Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory. questions by the author | Findings indicate that the course led to significant reduction in burnout levels and dearth anxiety. Correlations were found between personal sense of well-being and professional fulfillment, and between professional fulfillment and empathy, congruence, and unconditional acceptance of patients. | Burnout risks; importance of self-care, time for reflection, a nd personal well-being |

| Leung et al (2012)(14) | Five session Meaning Centered Intervention (2 groups of n=7 nurses) in Canada; semi-structured interviews pre- and post-intervention, Interpretive phenomenology analysis | Nurses reported greater meaning in dealing with suffering of their patients and were inspired to engage further with patients. Three themes emerged: attention to boundaries between personal and professional involvement, awareness of a shared mortality resulting in enhanced empathy, and ability to link patient suffering to meaning. | Meaning-making, shared mortality, intervention |

| DeArmond (2012)(15) | Psycho-biographical and hermeneutic methods; n =17 hospice workers in California | 88% of participants classified experiences as a chance to reflect and look inward, and demonstrated personal growth. Participants described changes in personality such as less fear of death, more compassion, and peace. | Reflection; newfound life perspective |

| Mak et al (2013)(16) | A qualitative interpretive descriptive methodology; 15 nurses in three acute medical wards in Hong Kong | The nurses experienced great mental and physical strain. Four themes were derived from the findings: lack of prepared ness for patients’ deaths, reflecting on their own nursing roles for dying patients, reflecting on the meaning of death and their personal experiences of the death of their own family members, and coping with caring for dying patients. | Helplessness and depersonalization due to patient deaths; newfound life perspective; importance of self-care |

| Breen et al (2014)(17) | Semi-structured interview; n=38 health care professionals working in cancer and palliative care in Western Australia | A qualitative grounded theory analysis showed four themes: (1) the role health professionals play in supporting people who are experiencing grief and loss issues in the context of cancer, (2) ways of working with cancer patients and their families, (3) loss and grief experiences specific to the cancer context, and (4) the emotional demands of the work and necessary self-care | Emotional demands; importance of self-care |

| Zambrano et al (2014](18) | Qualitative, open-ended interviews; n=7 palliative medicine specialists in Australia | The analysis of participants’ interviews demonstrated three themes: being with the dying, being affected by death and dying, and adjusting to the impact of death and dying. | Emotional demands; rewards of work; meaning-making; importance of self-care |

| Wu & Volker (2009)(19) | Qualitative, hermeneutic, phenomenological approach, interviews were audio taped and analyzed with Colaizzi’s guidelines; n=14 Taiwanese hospice nurses | Four main themes emerged: entering the hospice specialty, managing everyday work, living with the challenges, and reaping the rewards. The greatest distress came when nurses could not attain the goal of care. Most nurses stated they are now more open-minded, better able to put life’s challenges into perspective, and more focused on living in the present since working in hospice. Hospice care gives nurses an opportunity to reflect on their own philosophy of death and meaning in life. | Emotional distress; newfound life perspective; living in the present; reflection on death and personal meaning in life |

| Sliter et al (2014)(21) | Multi-time point survey; final sample consisted of 162 female Registered Nurses in a hospital or acute care setting in the United States; Death and Dying subscale of the Expanded Nurses Stressors Scale. Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure, Utrecht Work Engagement Sale, Revised DA Scale | Trait death anxiety was associated with more burnout and less work engagement. The relationship between mortality cues (eg. dealing with injured and dying patients) and burnout was stronger for those higher in death anxiety. | Death anxiety, burnout risk |

| Strang et al (2014)(22) | Five group reflection sessions were recorded, transcribed and analyzed using qualitative content analysis; n= 98 nurses from hospital, hospice, and homecare teams in Sweden | Three domains emerged: content of existential conversations with patients, process of dealing with these conversations, and meaning of these conversations for nurses. Nurses reported feelings of burden, exhaustion, and feeling empty when the situation was hopeless. Nurses also reported greater appreciation for life and ability to put trivialities into perspective. | Emotional demands; burden; newfound life perspective; meaning in work |

| Seccareccia & Brown (2009)(23) | Qualitative method of phenomenology; n= 10 palliative care physicians in Toronto and Ontario | Participant; reported that spirituality influenced practice and practice influenced their spirituality. Participants described that caring for the dying shaped their own self-actualization and they shared a sense of awe for patients and families. | Spirituality; self-actualization |

| Fegg et al (2014)(24) | Cross-sectional survey; 140 health care professionals (HCPs) working in three palliative care units and three maternity wards in Munich Germany; sociodemographic data, Idler Index of Religiosity, Schwartz Value Survey, The Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation | No differences between the groups were found in overall Meaning in Life satisfaction scores. Palliative are HCPs were significantly more religious than Maternity ward HCPs; they listed spirituality and nature experience more often as areas that give them meaning. Also, hedonism was more important for Palliative care HCPs, and they had higher scores in openness-to-change values (stimulation and self-direction). | Palliative HCPs endorse creativity, experiential, and attitudinal scources of meaning; highly spiritual |

| Peters et all (2013)(25) | Mixed methods design including questionnaire and interview; n=28 emergency dept nurses, n= 28 palliative care nurses in Melbourne, Australia.; demographics data, Death Attitude Profile-Revised Scale, Clinical Coping Skills Questionnaire-Peters | Nurses held low to moderate Fear of Death (44%)r Death Avoidance (34%), Escape Acceptance (47%), Approach Acceptance (59%) and moderate Death Anxiety (53%). Emergency nurses reported higher death avoidance and significantly lower coping stills than palliative care nurses. Both reported high acceptance of the reality of death [Neutral Acceptance 82%), and stated they coped better with a patient who was dying than with the patient’s family. | Death anxiety; lower death avoidance in a culture where death and dying is expected |

Discussion

This review examined the current literature on existential distress in HCPs working with patients at EOL. Specifically, we examined existential distress as a context from which negative outcomes, such as emotional distress or burnout, or positive outcomes, such as meaning-making or personal growth, may arise. Findings revealed a range of themes, including contemplation of existential issues related to one’s own life experiences and ultimate mortality, the link between death anxiety and existential distress, situational risk factors and potential benefits of working with the dying, and the conceivable impact of existentially targeted interventions.

The central finding from this review is that existential distress in HCPs does not necessarily imply negative outcomes. Rather, the coping skills and self-care strategies of those involved in EOL care may mediate the outcomes of existential distress. For example, the review demonstrated that those who experience negative existential distress may face sequelae such as burnout, helplessness, or depersonalization (8*, 13, 16*, 21*, 25*). However, HCPs who turn the challenges of working with death into an opportunity to reflect on one’s own life experiences and mortality or to find meaning and perspective (12, 15, 17*, 18**) may experience more positive outcomes such as reduced fear of death, increased compassion (12, 15), higher self-actualization (23), greater sense of personal accomplishment (6**), or improved quality of life (11).

Another key finding is the notion that EOL health care providers self-select into this role. This idea of choice is vital and may account for differences not only between professional and informal EOL caregivers, but also between HCPs who specialize in EOL and those who do not (6**, 25*). It therefore remains unclear whether personality characteristics such as openness to change (24*), values such as spirituality (23, 24*), or early life experiences (12) precede self-selection into EOL professional caregiving, or if the culture of the profession (25*) impacts the professional over time. In other words, does a predilection to contemplating the existential predispose an individual to become an EOL caregiver, or does the process of caring for dying individuals force caregivers to confront existential themes?

This review has several notable strengths and weaknesses. The inclusion of a wide range of cultures and professions increases the potential generalizability of our findings. Studies were conducted across a vast diversity of countries and cultures, including Australia, Canada, Germany, Hong Kong, Portugal, Sweden, Taiwan, and the USA. Likewise, a variety of professions were examined, including nurses and doctors from various specialties—not just palliative care or oncology—as well as hospice workers, clergy, physical and occupational therapists, psychologists, social workers, hospital volunteers, and more. Furthermore, the diversity of methods included qualitative, descriptive quantitative, longitudinal survey, intervention, and review, all of which increased the richness of the data and ensures a solid, if early-stage, foundation for future research. However, it is also important to acknowledge limitations of this review, most critical of which was the lack of precise definitions of existential constructs such as “reflection,” “perspective,” and “meaning,” or inconsistent definitions between studies. Such amorphous terminology may limit the generalizability of findings. Also, many of the studies had limited samples; in particular, a number of qualitative samples employed particularly small sample sizes, though all studies noted that saturation was reached.

Most importantly, this review revealed substantial gaps in the literature focusing on HCPs, which is expected in a burgeoning field. It also highlights the need for a theoretical model of existential distress in HCPs. Theoretical models of burnout and compassion fatigue exist (29, 30), but a model of existential distress is necessary to examine its role in negative outcomes such as burnout, depersonalization, or depression in HCPs, or positive outcomes such as professional or spiritual growth and resilience. Another area open for future research is the examination of mediators and moderators of distress, including both individual and situation-based characteristics. In terms of applied research, interventions are necessary for HCPs currently working in the field both to ameliorate symptoms of burnout in those who are struggling and to inoculate against negative outcomes in those who are coping effectively. Moreover, future research can help develop evidence-based education for HCPs in training or who make a career change from other fields. Development of evidence-based interventions is vital, as burnout negatively impacts a wide network of the health care professionals, patients, and families, and contributes to the financial costs of the health care system at large.

EOL care is an evolving journey for HCPs that evokes many existential concerns and varies considerably. While fraught with challenges and not without risk, if approached with internal strengths and external support, working with patients at EOL can be an opportunity for newfound meaning and personal growth.

Key Points.

Increased opportunity for reflection on mortality and greater perspective on life

Negative effects include death anxiety and disengagement from patients

Risk factors such as the nature of the death, individual and situational characteristics may predict outcomes

Potential benefits include enhanced sense of meaning in work and personal growth

Interventions and self-care aimed at buffering existential issues are essential to prevent negative impact and enhance potential gains

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Financial Support and Sponsorship: None

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Cherny NI, Coyle N, Foley KM. Suffering in the advanced cancer patient: a definition and taxonomy. Journal of palliative care. 1994;10(2):57–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kissane DW. Psychospiritual and existential distress. The challenge for palliative care. Australian family physician. 2000;29(11):1022–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Kaim M, Funesti-Esch J, Galietta M, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. Jama. 2000;284(22):2907–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applebaum AJ, Farran CJ, Marziliano AM, Pasternak AR, Breitbart W. Preliminary study of themes of meaning and psychosocial service use among informal cancer caregivers. Palliative & supportive care. 2014;12(2):139–48. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maslach CJS, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6**.Gama G, Barbosa F, Vieira M. Personal determinants of nurses’ burnout in end of life care. European journal of oncology nursing: the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2014;18(5):527–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.04.005. This article demonstrates significant differences in burnout risk between palliative care workers and all other medical care professionals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.J SP, Hy Ho A, Chan F, Lu Wang X, Cheng C. Can art therapy reduce death anxiety and burnout in end-of-life care workers? a quasi-experimental study. International journal of palliative nursing. 2014;20(5):233–40. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.5.233. This study highlights the importance of intervention and reflection for health care professionals, specifically meaning-making processes and emotion-focused coping. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8*.Peters L, Cant R, Payne S, O’Connor M, McDermott F, Hood K, et al. How death anxiety impacts nurses’ caring for patients at the end of life: a review of literature. The open nursing journal. 2013;7:14–21. doi: 10.2174/1874434601307010014. This article identifies several risk factors for professionals who encounter death and dying. Authors examine potentially negative outcomes on patient care when death anxiety is left unchecked in healthcare professionals. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kutner JS, Kilbourn KM. Bereavement: addressing challenges faced by advanced cancer patients, their caregivers, and their physicians. Primary care. 2009;36(4):825–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fillion L, Saint-Laurent L, Rousseau N. Les stresseurs liés à la pratique infirmière en soins palliatifs: les points de vue des infirmières. Les cahiers de soins palliatifs. 2003;4(1):5–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fillion L, Duval S, Dumont S, Gagnon P, Tremblay I, Bairati I, et al. Impact of a meaning-centered intervention on job satisfaction and on quality of life among palliative care nurses. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18(12):1300–10. doi: 10.1002/pon.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinclair S. Impact of death and dying on the personal lives and practices of palliative and hospice care professionals. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2011;183(2):180–7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melo CG, Oliver D. Can addressing death anxiety reduce health care workers’ burnout and improve patient care? Journal of palliative care. 2011;27(4):287–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung DFL, Duval S, Brown J, Rodin G, Howell D. Meaning in bone marrow transplant nurses’ work: experiences before and after a “meaning-centered” intervention. Cancer Nursing. 2012;35(5):374–81. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318232e237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeArmond IM. The psychological experience of hospice workers during encounters with death. Omega. 2012;66(4):281–99. doi: 10.2190/om.66.4.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*.Mak YW, Chiang VC, Chui WT. Experiences and perceptions of nurses caring for dying patients and families in the acute medical admission setting. International journal of palliative nursing. 2013;19(9):423–31. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.9.423. This article highlights the importance of reflection for end-of-life workers and the associated benefits. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17*.Breen LJ, O’Connor M, Hewitt LY, Lobb EA. The “specter” of cancer: Exploring secondary trauma for health professionals providing cancer support and counseling [Home Care & Hospice 3375] US: Educational Publishing Foundation US; 2014. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc10&NEWS=N&AN=2013-34607-001 [cited 11 Ablett, J. R., & Jones, R. S. P. (2007). Resilience and well-being in palliative care staff: A qualitative study of hospice nurses’ experience of work. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 733-740. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1130 ]. 1:[ 60-7]. Available from: ]. 1:[ 60-7]. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc10&NEWS=N&AN=2013-34607-001 . This article illustrates the emotionals demands cancer professionals face and stresses the importance of self-care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Zambrano SC, Chur-Hansen A, Crawford GB. The experiences, coping mechanisms, and impact of death and dying on palliative medicine specialists. Palliative & supportive care. 2014;12(4):309–16. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000138. This article reflects the potential benefits and rewards of working in palliative medicine if providers prioritize self-care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu HL, Volker DL. Living with death and dying: the experience of Taiwanese hospice nurses. Oncology nursing forum. 2009;36(5):578–84. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.578-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomer A, Eliason G. Toward a comprehensive model of death anxiety. Death Stud. 1996;20(4):343–65. doi: 10.1080/07481189608252787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Sliter MT, Sinclair RR, Yuan Z, Mohr CD. Don’t fear the reaper: Trait death anxiety, mortality salience, and occupational health [Personality Traits & Processes 3120] US: American Psychological Association US; 2014. [cited 99 Industrial & Organizational Psychology [3600]]. 4:[759-69]. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc11&NEWS=N&AN=2014-03488-001. This article demonstrates the detrimental effects of death anxiety for health care professionals and suggests ways to alleviate such death anxiety. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Strang S, Henoch I, Danielson E, Browall M, Melin-Johansson C. Communication about existential issues with patients close to death–nurses’ reflections on content, process and meaning. Psycho-oncology. 2014;23(5):562–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.3456. This article highlights significant emotional burdens nurses face, yet also the great meaning and newfound life perspectives they derive from working with patients contemplating existential issues. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seccareccia D, Brown JB. Impact of spirituality on palliative care physicians: personally and professionally. Journal of palliative medicine. 2009;12(9):805–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Fegg M, L’Hoste S, Brandstatter M, Borasio GD. Does the Working Environment Influence Health Care Professionals’ Values, Meaning in Life and Religiousness? Palliative Care Units Compared With Maternity Wards. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.009. This article highlights differences and similarities between maternity ward and palliative care providers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Peters L, Cant R, Payne S, O’Connor M, McDermott F, Hood K, et al. Emergency and palliative care nurses’ levels of anxiety about death and coping with death: a questionnaire survey. Australasian emergency nursing journal: AENJ. 2013;16(4):152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2013.08.001. This article examines differences between emergency department nurses and palliative care nurses. The article illustrates palliative care as a unique setting where death and dying is expected. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breitbart W, Poppito S, Rosenfeld B, Vickers AJ, Li Y, Abbey J, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(12):1304–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, Pessin H, Poppito S, Nelson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19(1):21–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Applebaum A, Kulikowski J, Breitbart W. Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Cancer Caregivers (MCP-C): Rationale and Overview. Palliative and Supportive Care. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000450. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. A model of burnout and life satisfaction amongst nurses. Journal of advanced nursing. 2000;32(2):454–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernando AT, 3rd, Consedine NS. Beyond compassion fatigue: the transactional model of physician compassion. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2014;48(2):289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]