Abstract

A number of interesting reports highlight the intricate network of signaling proteins that coordinate formation and maintenance of cell–cell contacts. We have much yet to learn about how the in vitro binding data is translated into protein association inside the cells and whether such interaction modulates the signaling properties of the protein. What emerges from recent studies is the importance to carefully consider small GTPase activation in the context of where its activation occurs, which upstream regulators are involved in the activation/inactivation cycle and the GTPase interacting partners that determine the intracellular niche and extent of signaling. Data discussed here unravel unparalleled cooperation and coordination of functions among GTPases and their regulators in supporting strong adhesion between cells.

The presence of tight cell–cell attachment is a hallmark of different cell types such as epithelial, endothelial, cardiac, or smooth muscle cells, which require strong cohesion for their specialized functions and to sustain mechanical stress. In these cell types, different members of the cadherin family of cell–cell adhesion receptors drive and orchestrate the assembly of additional adhesion complexes, thereby providing spatial signals to organize the cytoskeleton and signaling components at junctions. The relevance of cadherin-dependent adhesion to tissue morphogenesis and function is highlighted in the strong defects in tissue organization and pathologies associated with disruption of junction structure (Macara et al. 2014).

In different cell types, cell–cell junctions are “hot spots” for the localization of signaling molecules such as small GTPases, their regulators and effectors, kinases, phosphatases, and others. In the past decade, exciting studies have mapped the molecular complexes that support and strengthen attachment of cadherin receptors between neighboring cells (Zaidel-Bar 2013; Citi et al. 2014; Zaidel-Bar et al. 2015), the regulation of receptor interaction with the underlying cytoskeleton and how cytoskeletal remodeling is driven by the presence of cell–cell contacts (Huveneers and de Rooij 2013; Ladoux et al. 2015; Strale et al. 2015). In parallel with these advancements, a number of regulators of junction assembly or maintenance have been identified among cytoskeletal or signaling proteins (McCormack et al. 2013; van Buul et al. 2014; Sluysmans et al. 2017).

However, this extensive knowledge requires now a systematic approach to integrate the various regulators in the context of their intracellular compartmentalization, cycles of activation/inactivation, interaction with selected effectors, and precise positioning at cytoskeletal structures and junctional adhesive complexes. From the large number of regulators of cell–cell contacts identified so far, research is moving on to dissect the interplay among key signaling pathways, scaffolding proteins, and the modulation of cellular processes driven by junctions. This perspective discusses recent insights in our understanding of the integration of signaling at cell–cell junctions in epithelial cells. Excellent reviews on Rho GTPase regulators in other cell types (Ngok and Anastasiadis 2013; van Buul et al. 2014) and their specific interaction polarity complexes (Citi et al. 2014; Ngok et al. 2014) can be found elsewhere.

SIGNALING ACTIVATION: WHERE AND HOW

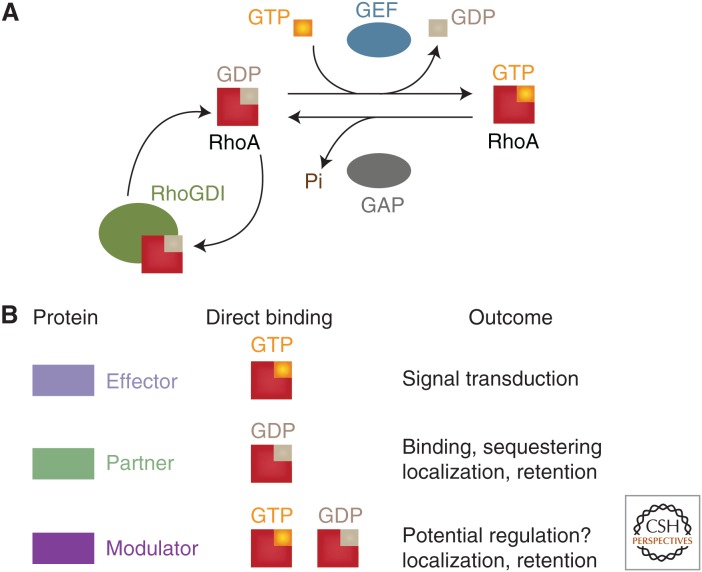

The majority of Rho family of small GTPases (or Rho GTPases, for short) are found in an inactive, GDP-bound form and most likely associated with RhoGDI in the cytoplasm (Cook et al. 2014). The classical view of activation of Rho GTPases at adhesive sites is that it occurs (Fig. 1A) via stimulation of specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEF) or by inactivation of a GTPase activating protein (GAP) (Cook et al. 2014; Schaefer et al. 2014; Hodge and Ridley 2016). Small GTPase activation may occur locally at the adhesion site and membrane regions, where its function is required and then interact with its effectors and modulators (Fig. 1B). Inactive GTPases may be sequestered in the cytoplasm via interaction with RhoGDI (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Classical regulation of Rho GTPases. Rho small GTPases are mostly found in an inactive, GDP-bound form, and is transiently activated when bound to GTP. This cycle is tightly modulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEF), which facilitates replacement of GDP for GTP. GTPase inactivation is facilitated by guanine nucleotide activating protein (GAP), as the latter increases the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis of small GTPases. Inactivated GTPases may be removed from membranes and maintained in the cytoplasm by interaction with RhoGDI. (B) Different proteins are able to interact directly with active or inactive GTPases or both forms. On interaction, different functions and cellular outcomes may occur (see text for more details).

In any case, at steady state, GEFs and GAPs must avoid random interaction with substrate GTPases and indeed they have evolved different mechanisms to do so (Schaefer et al. 2014; Raimondi et al. 2015; Hodge and Ridley 2016). Current data reinforce a potential key function of interacting partners and additional domains of GEFs and GAPs to drive the specificity and localization of GTPase regulation. For example, the catalytic domain of GAPs are found to be nonselective in vitro and additional domains may govern specificity toward GTPase substrates (Amin et al. 2016). These results help to explain the different substrate specificity of in vitro (with purified catalytic domains) and in vivo GAP assays following a specific stimulus.

It becomes clear that the classical regulation of Rho GTPases cannot fully account for a much more complex and wired regulation of GTPase function. Among additional regulatory events of GTPase signaling, there are (Hodge and Ridley 2016): (1) posttranslation modifications such as ubiquitination and sumoylation to potentially regulate GTPase protein levels; (2) phosphorylation, which can modulate binding affinity; and (3) interaction with cytoskeletal proteins (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 1B). Evidently, these additional forms of GTPase regulation may complement and be coordinated with the classical activation and inactivation cycles by GEFs and GAPs. Conceptually, these distinct regulatory events also pose different questions and potential mechanisms of how a given signaling pathway operates at cell–cell contacts.

Table 1.

Selected list of exchange factors (GEF) shown to interact with lipids and cytoskeletal proteins found at epithelial junctions

| GEF | Names | GTPase | Partnera | Effect interactionb | Functional outcome | Additional observations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trio | ARHGEF23 | Rac1 | Tara | Inhibition | Regulates E-cadherin transcriptional levels | Increases Trio binding to E-cadherin tail; Tara binds directly and stabilize F-actin | Seipel et al. 2001; Yano et al. 2011 |

| Filamin A | Recruitment | Reduces RhoA activation induced by junction assembly | Association with cadherin complexes increase with junction formation | Tu and You, 2014 | |||

| Tiam-1 | — | Rac1 | Paracingulin | Recruitment | Paragingulin depletion inactivates Rac1 during junction formation | Depletion paracingulin decreases Tiam1, but not Ect2, at contacts | Guillemot et al. 2008, 2014 |

| Par3 (PDZ2) | ND | Regulates TJ assembly | Par3 depleted cells, Rac1 is constitutively activated | Chen and Macara, 2005; Mertens et al. 2005 | |||

| Par3 | ND | Inactivates and promotes a gradient of Rac1 activity along cell–cell contacts | Mack et al. 2012 | ||||

| β2-syntrophin (PDZ domain) | activation | Restrict Rac1 activation to TJ | Regulates TJ assembly | Mack et al. 2012 | |||

| GEF-H1 | ARHGEF2 | RhoA | Cingulin (amino acids 782–1025) | Inhibition | Mechanism inhibition unknown | Aijaz et al. 2005 | |

| Paracingulin | Recruitment | RhoA activity increases on depletion of paracingulin | Guillemot et al. 2008 | ||||

| PDZ RhoGEF | ARHGEF11 | RhoA | ZO-1 | ND | Regulates myosin activation at junctions | Localizes to primordial contacts and then tight junctions | Itoh et al. 2012 |

| ND | ND | Celsr1 necessary for recrutiment | Restricts RhoA activation apically to induce constriction | Sai et al. 2014 | |||

| p114 RhoGEF | ARHGEF18 | RhoA | LKB1 (amino acids 155–433) | Activation | Maturation of apical junctions | Independent of LKB1 activity | Xu et al. 2013 |

| Cingulin | ND | Regulates junctional RhoA and myosin activation at cell–cell contacts | Cell-type specific interaction | Terry et al. 2012 | |||

| Lulu2 | Activation | Regulation of circumferential actin ring | Interaction modulated by Lulu2 phosphorylation | Nakajima and Tanoue, 2011 | |||

| Tuba | ARHGEF36 | Cdc42 | Tricellulin | Activation | Tension to produce straight junctions | Recruitment to adherens junctions | Oda et al. 2014; Otani et al. 2006 |

| ZO-1 | ND | Recruitment to tight junctions | |||||

| N-WASP | ND | Cooperate in nascent junctions in luminogenesis | N-WASP polyproline domain interacts with Tuba carboxy-terminal | Kovacs et al. 2006 | |||

| TEM4 | ARHGEF17 | RhoA | Cadherin complex | ND | Knockdown generates elongated cells and curved junctions | Association independent of F-actin interaction; coprecipitates with a number of cytoskeletal proteins | Ngok et al. 2013 |

| Ect2 | ARHGEF31 | RhoA | Anillin (772–940) | Stabilizes central spindle microtubules | Interaction with the PH domain Ect2 | Frenette et al. 2012 | |

| Centralspindlin complex | Localization | Localizes ECT2 at adherens junctions, microtubule- dependent | Stabilizes E-cadherin at contact-sites | Ratheesh et al. 2012 | |||

| α-catenin | Retention | Coprecipitation is microtubule-dependent | Ratheesh et al. 2012 | ||||

| Asef | ARHGEF4 | RhoA | PI(3,4,5)P | Recruitment | Overexpression Asef increases E-cadherin at junctions | Muroya et al. 2007 | |

| Vav2 | — | ND | p120CTN | Recrutiment to cadherin tail | Vav2 depletion reduces cadherin levels at junctions | Binding to E-cadherin tail in a p120-dependent manner | Erasmus et al. 2016 |

| Rac1,Cdc42 | p120CTN | ND | ND | Complex does not contain E-cadherin | Noren et al. 2000 | ||

| Rac1 | p120CTN | ND | ND | Binding cytosolic pools of p120CTN, binding stimulated by Wnt 3A treatment | Espejo et al. 2014; Valls et al. 2013 | ||

| β-PIX | ARHGEF7 | Cdc42 | P-cadherin | Recruitment | Activation of Cdc42 to promote collective migration | Also interacts with N- and E-cadherin in C2C12 cells | Plutoni et al. 2016 |

| Solo | ARHGEF40 | RhoA | Keratin 18 | May mediate junction-dependent responses to mechanical stretch | Endothelial cells | Abiko et al. 2015; Fujiwara et al. 2016 |

Listed are the exchange factor two different names, small GTPase showed to be modulated in the particular example, interacting partner, what is the effect of the interaction (if known), and the functional outcome for junctions or other cellular processes. Also shown are additional observations and the references reporting the results.

aPartners listed are those that interact biochemically with the GEF (directly or indirectly); TJ, tight junctions.

bTwo major effects caused by the interaction are reported: modulation of the localization of the GEF (recruitment, retention) at junctions or regulation of the activity status either directly (in vitro via the binding to key domains) or indirectly (via measurement of GTPase activity levels in cellulo). ND, not determined.

Table 2.

Selected list of GTPase activating proteins (GAP) shown to interact with lipids and cytoskeletal proteins found at epithelial junctions

| GAP | Names | GTPase | Partnera | Effect interactionb | Effect on junctions | Additional observations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FILGAP | ARHGAP24 | Rac1 | ND | Activated by ROCK-1 phosphorylation to inactivate Rac1 | Stimulates accumulation of E-cadherin at junctions; GAP activity required | Nakahara et al. 2015 | |

| Rich1 | ARHGAP17 | Rac1, Cdc42 | Amot (coil-coiled domain) | Inhibition of Rich1 activity; release by competitive binding with Merlin | Recruitment to TJ | Wells et al. 2006; Yi et al. 2011 | |

| DLC1 | ARHGAP7 | RhoA | α-catenin (aa 117–161) | Accumulation of α-catenin and DLC1 at membranes and cytosol | Reduces active RhoA levels at membrane; depletion destabilizes E-cadherin at junctions | Tripathi et al. 2012 | |

| DLC2 | ARHGAP37 | Cdc42 | KIF1B (forkhead-associated domain) | ND-complex coprecipitates with p120CTN | ND. DLC2 depletion leads to a mild junction defect. | Elbediwy et al. 2012; Vitiello et al. 2014 | |

| DLC3 | ARHGAP38 | RhoA | Scribble (PDZ3) | Recruitment | Inactivates RhoA at junctions | Via its PDZ ligand motif | Hendrick et al. 2016; Holeiter et al. 2012 |

| p190RhoGAP-A | ARHGAP35 | RhoA | p120CTN (amino acids 820–843) | Subcellular targeting | ND | To endothelial junctions | Zebda et al. 2013 |

| p120CTN | PDGFR-induced transient translocation | N-cadherin contacts regulated by GAP | Wildenberg et al. 2006 | ||||

| p190RhoGAP-B | ARHGAP5 | RhoA | p120CTN | ND | Depletion GAP increases RhoA activity at junctions | Association regulated by matrix compliance | Ponik et al. 2013 |

| RhoA | Active Rac1 | Recruitment to junctions via interaction with active Rac1 levels | Control levels of active RhoA at cadherin contacts | Recruitment dependent on McgRacGAP | Ratheesh et al. 2012 | ||

| myosin IXa | — | RhoA | F-actin | ND | Regulate assembly F-actin to native junctions | Binding via the motor domain; | Omelchenko and Hall, 2012 |

| MgcRacGAP | RACGAP1, Cyk4 | Rac1 | Cingulin, paracingulin | Recruitment, ND | Inhibits Rac1 at newly formed tight junctions | Direct binding | Guillemot et al. 2014 |

| Rac1, RhoA | ND | ND | Perturbs AJ, inhibits RhoA and Rac1 activity at junctions | Xenopus cells | Breznau et al. 2015 | ||

| Rac1 | α-catenin (1–507) | Retention of McgGAP at junctions | Coprecipitation is microtubule-dependent | Ratheesh et al. 2012 | |||

| β2 chimerin | ARHGAP3 | Rac1 | DAG | Recruitment to apical domain of epithelial cysts | Suppresses Rac1 activation at the apical domain | Depletion increases number of cells inside lumen | Yagi et al. 2012a,b |

Listed are the GAP two different names, small GTPase showed to be modulated in the particular report (rather than known in vitro substrates), interacting partner, what is the effect of the interaction (if known), and the functional outcome for junctions or other cellular processes. Also shown are additional observations and the references reporting the results.

aPartners listed are those that interact directly or indirectly with the GEF; TJ, tight junctions.

bTwo major effects caused by the interaction are reported: modulation of the localization of the GAP (recruitment, retention) at junctions or regulation of the activity status either directly (in vitro via the binding to key domains) or indirectly (via measurement of GTPase activity levels in cellulo). ND, not determined.

This review focus on the potential participation of cytoskeletal proteins to fine-tune the action and localization of Rho GTPases signaling. A number of cytoskeletal proteins are known effectors of GTPases, that is, they interact with cytoskeletal filaments and the GTP-bound active form of GTPases to transduce signaling toward a specific cellular outcome. Other proteins interact with the inactive form of GTPases, and are thought to behave as sequesters, similar to RhoGDI. A classic example is p120CTN, protein that interacts with the cadherin tail: p120CTN cytoplasmic pool can interact with RhoA and inactivate this pathway in different cells (Kourtidis et al. 2013; Peglion and Etienne-Manneville 2013). Finally, other cytoskeletal proteins may bind a GTPase independently of its GTP or GDP loading (Lam and Hordijk 2013), and are thus not considered effectors or sequesters. Such activation-independent interaction may serve to either localize the GTPase or to retain the GTPase at junctions (Nola et al. 2011; Reyes et al. 2014). Examples are the F-Bar protein PACSIN (Lam and Hordijk 2013) and the actin bundling and LIM-domain protein Ajuba (see below) (JJ McCormack, S Bruche, ABD Ouadda, et al. in press; Nola et al. 2011).

WHERE TO BE, WHERE TO FUNCTION

A signaling molecule can be found in various intracellular and cortical structures and dispersed in the cytoplasm. Subcellular localization is a recognized mechanism to compartmentalize signaling pathways to control specific cellular processes. The current dogma in interpreting the function of a junction regulator is that it must be detected at cell–cell adhesive sites. In one hand, this rational is clearly applicable to cytoskeletal proteins that support scaffolding structures at junctions or cytoskeletal proteins that are transiently recruited to junctions by different stimuli, such as mechanical stress, growth factor stimulation, etc. (Ladoux et al. 2015). On the other hand, additional points should be considered for enzymatic regulators such as GTPase signaling components such as the control of localization and activation/inactivation status. Below I discuss some considerations on these topics and summarize current evidence.

It is highly likely that the amount of a particular GTPase or regulator detected at junctions by standard microscopy represents an inactive pool. First, rapid activation and inactivation is predicted to be in place to ensure tight GTPase regulation temporally and to avoid over-activation that can be deleterious to junctions (Cook et al. 2014). Second, a specific treatment drives a surge of stimulation; however, only a very small fraction of the GTPase is activated transiently. At steady-state, the fraction of active GTPase or its regulator(s) at junctions may be even smaller, considering the heterogeneity of stimulus at different regions of cell–cell contacts (different receptors, trafficking, mechanical stress, and others).

The lack of correlation between localization and steady-state pathway activation is supported by three sets of data. First, constitutively active or dominant forms of GTPases when expressed in epithelial cells localize at junctions (Takaishi et al. 1997; Braga et al. 2000; Ehrlich et al. 2002; Yamada and Nelson 2007). Second, constitutive activation of GTPases (by locking on a GTP-bound status) or their regulators (truncations or point mutations) have pathological and dire consequences for normal cellular function (Alan and Lundquist 2013; Porter et al. 2016). Although Rac1 is essential for junction stability, activated Rac1 expression strongly disrupt cell–cell contacts (Marei and Malliri 2016). In addition, fast cycling mutations of small GTPases have been identified in tumor samples (Alan and Lundquist 2013; Porter et al. 2016). They behave as constitutively active mutants, as they undergo faster cycles of activation/inactivation and have thus enhanced kinetics of GTP hydrolysis.

Finally, the distribution of the active GTPase pool detected by biosensors (selectively recognize the activated status) forms an essential tool to understand the dynamic behavior of GTPases in space and time and have expanded exponentially our understanding of the mechanisms at play. There are a variety of biosensors for different GTPases (fluorescently tagged for expression in cells or as FRET/FLIM probes) (Schaefer et al. 2014). Differential localization of reporters (fluorescently tagged) and activated GTPases (biosensor FRET/FLIM signal) has been shown at cell–cell contacts (e.g., Priya et al. 2016) and during cell migration (e.g., Machacek et al. 2009).

Collectively, these data indicate that a concentration of predominantly active species of GTPases in a particular subcellular space is not desirable for the maintenance of homeostasis. There should be extensive controls to minimize inappropriate activation of Rho GTPase signaling, by ensuring a strong spatial and temporal modulation of GTPase cycling.

Building from past research of junction stabilization, it is clear that the correlation between localization of a regulator GAP or GEF and its positive role in contact stabilization does not hold true for all examples. Tables 1 and 2 list selected examples of interactions of GTPase regulators with cytoskeletal proteins and lipids that underpin their localization or function at junctions. Of note is that some GTPase regulators are held at the junctions primarily in an inactivated conformation, such as the GEFs Trio and GEF-H1 or the GAPs Rich1, β2 chimerin, and CdGAP (Tables 1 and 2).

For upstream regulators such as GEFs and GAPs, a number of mechanisms are known to mediate their specific distribution or activation (the reader is referred to excellent reviews on these topics, e.g., McCormack et al. 2013; Citi et al. 2014; van Buul et al. 2014; Sluysmans et al. 2017). In terms of their intracellular localization, the low expression levels of GEFs and GAPs in different cell types hinders the investigation of endogenous proteins. Unfortunately, the lack of suitable biosensors for GEF or GAP activation further complicates the precise mapping of where their dynamic regulation occurs. Of note is that higher levels of expression of a regulator in a given cell do not necessarily correlate with its importance on junction stabilization, as argued for endothelial cells (van Buul et al. 2014) and highlighted in Tables 1 and 2. Indeed, such argument is in line with the prediction that a very small pool of an upstream regulator is activated by a specific stimulus at any given time and place, similar to what has been shown for GTPases. Altogether, dynamic studies of upstream regulators lag behind our understanding of how Rho GTPases themselves operate.

Nevertheless, the same principles would operate for both classes of enzymes: steady-state localization of endogenous/expressed proteins may reflect an inactive pool. When required, cycles of activation/inactivation results in a transient activation of small GTPases to perform specific tasks. For example, GEF-H1, a RhoA and Rac1 GEF, is localized in an inactivated status at cell–cell contacts and at microtubule filaments (Krendel et al. 2002; Aijaz et al. 2005). It is feasible that GEF-H1 may be transiently activated to control vesicular trafficking locally (Pathak et al. 2012), and could thus participate in some aspects of adhesive receptor regulation. The Cdc42/Rac1 CdGAP is not essential for junction formation and is found inactivated at cell–cell contacts (McCormack et al., in press). Dysregulation of the mechanisms that maintain CdGAP inactive severely disrupts cell–cell contacts and causes cell retraction.

HOW LOCALIZED ACTIVATION TAKES PLACE?

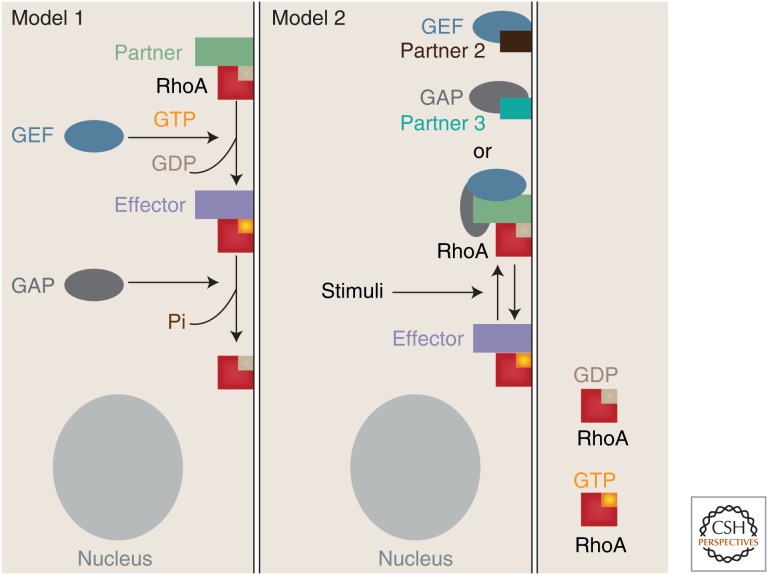

Two models underlying transient GTPase activation have been proposed so far (Fig. 2). The first model involves the transient recruitment to junctions of a GTPase and its regulator(s) to become activated. A variation of this model would have the GTPases already localized in an inactive status and the upstream regulator recruited to activate the Rho protein in situ. Such model would imply a spatial segregation between a GTPase and its regulators at different intracellular regions to prevent unwelcomed and inappropriate activation. The second model proposes a transient stimulation of a pool of regulators/GTPases already present at cell–cell contacts. This second model predicts that regulatory signaling units may already be in place at junctions as inactive complexes, which may or may not contain a given GTPase, its activator, and negative regulator in close proximity. A potential advantage of the latter mechanism is a better flow of information, as activation/inactivation cycles are faster and more efficient, without the need to coordinate independent and timely recruitment of different molecules to cell–cell contacts (see sections below).

Figure 2.

Potential models via which GTPase signaling is modulated at cell–cell contacts. In model 1, Rho GTPases are maintained at cell–cell contacts via association with binding proteins in an inactive, GDP-bound form. On stimulation, the regulator of GTPases (GEF) is translocated to junctions to activate the small GTPase, enabling interaction with effector proteins. The process is reversed via recruitment of a GAP, which help with the hydrolysis of GTP into GDP, releasing phosphate (Pi). In model 2, it is predicted that inactivated Rho proteins are maintained at junctions in a complex with cytoskeletal proteins that may or may not interact with selected GEF or GAP (see also Fig. 3). Alternatively, GEF/GAP may interact with different partners at the membrane and be kept at close proximity to the Rho GTPase. On stimuli, transient activation/inactivation is achieved coordinately in a speedy manner. In both models, Rho GTPase activation may also occur by blocking locally the function of a GAP, enabling a shift to GTP-loaded GTPase (not shown for simplicity). See text and Tables 1 and 2 for more details and references. Diagrams are not drawn to scale.

The two described models are clearly challenging to dissect (Fig. 2). Examples of de novo recruitment of specific GTPases or regulators to junctions following a stimulus have been reported, whereas the presence of inactive pools of GTPase or regulators is also well documented (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, different mechanisms to maintain regulators at junctions may generate distinct outcomes in different cell types. Tiam1, p114RhoGEF, or Tuba are able to associate with multiple cytoskeletal proteins at junctions (Table 1), which restricts their positioning at distinct adhesive sites (i.e., apico-basolateral axis, adherens junctions versus tight junctions) by controlling their recruitment and/or retention at cell–cell contacts.

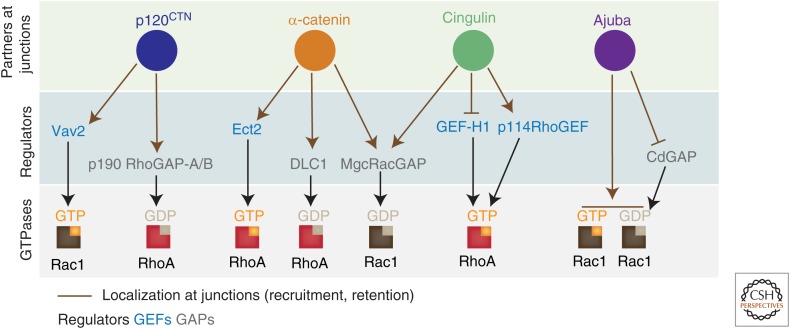

Importantly, such interactions can also modulate the GEF activation status depending on the associated protein. Cingulin, a tight junction protein, has been shown to interact with GEF-H1 and keep it inhibited at junctions (Fig. 3) (Aijaz et al. 2005). Cingulin also binds to p114RhoGEF in a separate complex (Terry et al. 2012), but it is not clear whether this GEF is also inhibited by cingulin interaction. Instead, association of p114RhoGEF with Lulu2, a FERM-containing actin binding protein, leads to GEF activation and modulation of tension at perijunctional actin ring (Nakajima and Tanoue 2011). Another example is the association of P-cadherin with the GEF β-PIX, which recruits a pool of β-PIX to sites of cell–cell contacts in C2C12 cells. Expression of P-cadherin increases the activation of Cdc42 and Rac1 specifically in migrating cells, rather than in confluent cells or isolated migrating cells (Plutoni et al. 2016). Collectively, the data indicate that the precise activation of individual GTPases in specific cellular events is determined by the ability of associated partners and stimuli to recruit distinct regulators.

Figure 3.

Examples of multiple interactions converging on specific proteins resident at junctions. Selected examples of the ability of a cytoskeletal protein or junctional protein to associate with different regulators is depicted here. Such association modulates the activation and localization of regulators (GEF and GAP) by controlling their recruitment or retention at junctions. Each regulator can then modulate the activity of a specific GTPase; shown here is the GTPase that is modified specifically at junctions on modulation of the partner. Ternary complexes among partners and more than one regulator at junctions has not yet been formally shown. Of note is that, in some examples, interactions between partners and regulators can also be found in the cytoplasm in addition to junctions. For more details and references, see text and Tables 1 and 2. Diagrams are not drawn to scale.

The presence of a regulatory signaling unit (GTPase, GAP, and GEF) at junctions is predicted by the second model (Fig. 2). Unsuspected direct interactions among GEFs and GAPs with overlapping specificity for the same GTPase could provide fast, localized activation and inactivation. The existence of such complexes have been shown biochemically; for example, Intersectin (a GEF for Cdc42) and CdGAP (ARHGAP31, a GAP for Rac1 and Cdc42), although their potential function at cell–cell adhesion has not been addressed (Jenna et al. 2002; Primeau et al. 2011).

Alternatively, interactions among distinct regulators may coordinate activities of different GTPases in the local control of a cellular process important for junction stabilization (Fig. 2). There are numerous examples of such cross-talk during cytokinesis (Chircop 2014; Zuo et al. 2014), single cell wounding (Vaughan et al. 2011), or at attachment to extracellular matrices (Devreotes and Horwitz 2015). Similar regulatory complexes are being identified at junctions (Tables 1,2). Paracingulin, a tight junction protein, interacts with GEF-H1 and Tiam1 (a Rac1 GEF) and mediates their localization at junctions (Guillemot et al. 2008). The catenins may also play a prominent role in the coordination of such activities (Fig. 3; Tables 1 and 2): α-catenin associates with DLC1 (a RhoA GAP), Ect2 (RhoA GEF), and MgcRacGAP (a GAP for Rac1), whereas p120CTN binds to p190RhoGAP and Vav2 (a Rac1 GEF) (Ponik et al. 2013; Erasmus et al. 2016). However, ternary complexes among these proteins have not yet been characterized in the same cellular setting. Thus, the relevance of these interactions as a signaling hub still remains to be shown. Further investigation should seek to clarify key elements controlling recruitment or retention of each regulator at epithelial contacts, the site and mechanism of activation and how interacting partners help to modulate these processes. The wealth of information on the cytoskeletal and signaling molecules found at junctions (Bertocchi et al. 2012; Zaidel-Bar 2013; Zaidel-Bar et al. 2015) provides an excellent platform to spring board such studies.

CYTOSKELETAL STRUCTURES AS A PLATFORM FOR SIGNALING COMPLEXES

The organization of the cytoskeleton at different adhesive sites and intracellular regions has been long recognized as an important structure to harbor signaling complexes. Binding of GTPase regulators to cytoskeletal proteins/structures provides localization and retention cues at junctions but also a mechanism to control their activation. The latter may be direct (preferential binding to activated forms) or indirect by coupling distinct regulators in a complex. Below, I discuss examples of modulation of Rho GTPases and regulators by interfering with their association with specific cytoskeletal proteins or filamentous structures.

Modulation of levels of interacting partners indeed alter GTPase activation levels. For example, Ajuba interacts directly with both GDP- and GTP-bound Rac1, and when phosphorylated, has higher affinity for the activated, GTP-bound Rac1, retaining this form at cell–cell contacts (Nola et al. 2011). Depletion of Ajuba interferes with junction-dependent Rac1 activation (Nola et al. 2011). Pulsatile behavior of RhoA activation has been shown at Xenopus cell–cell contacts (Reyes et al. 2014). Depletion of anillin results in a higher frequency of active RhoA flares, but with shorter duration. As anillin interacts preferentially with active RhoA (Piekny and Glotzer 2008), the data is interpreted as a function for anillin to retain RhoA.GTP at cell–cell contacts. However, as shown during cytokinesis, anillin is also able to interact and co-localize with Rho regulators such as Ect2 (Piekny and Glotzer 2008; Frenette et al. 2012), p190RhoGAP-A or MgcRacGAP (D’Avino et al. 2008; Gregory et al. 2008; Manukyan et al. 2015). It will be interesting to address whether such complexes exist also at junctions and may contribute to the changes in RhoA activation observed on anillin depletion.

What becomes clear is that an interaction with cytoskeletal filaments may strongly influence the activation status of different GEFs and GAPs. A large number of GEFs has been shown to interact directly with myosin II assembled onto F-actin filaments in different cell types (Lee et al. 2010). Such association appears to be a general property of GEFs: it occurs via their catalytic domain (dbl domain) and suppresses GEF activation. In fibroblasts, a variety of GEFs localize to stress fibers and on myosin II phosphorylation and activation, their association is transiently decreased (Lee et al. 2010). Among the GEF shown to interact with myosin on contractile F-actin filaments, there are known regulators of cell–cell contacts such as Trio, Tiam1, GEF-H1, or β-PIX (Table 1). It will be interesting to determine whether similar association is found at perijunctional contractile filaments in epithelial cells.

Furthermore, pharmacological disruption of actin filaments releases GEFs, which are predicted to become activated and increase active levels of Rho GTPases. Indeed, treatment with blebbistatin or cytochalasin D leads to higher levels of active RhoA, Cdc42, or Rac1 (Lee et al. 2010). Similarly, mechanical strain or myosin II-driven forces has been shown to release FILGAP, a GAP for Rac1, from filaminA, a cross-linking actin binding protein (Ehrlicher et al. 2011). In this case, FILGAP attachment to filaminA leads to FILGAP activation and suppression of Rac1 activity, thereby enabling cellular responses to mechanical tension (Shifrin et al. 2009).

The microtubule cytoskeleton has been shown to be a repository for ARHGAP21 (Barcellos et al. 2013), DLC2 (Vitiello et al. 2014), and Rho GEFs such as GEF-H1 (Krendel et al. 2002) or Ect2 (Piekny and Glotzer 2008; Su et al. 2011). Whether microtubule binding to ARHGAP21, DLC2, or Ect2 modulates their catalytic activity is not clear. Disruption of microtubules pharmacologically releases and activates GEF-H1 (Chang et al. 2008; Pathak et al. 2012). In contrast, in lung endothelium, stimulation with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) increases the activation of the GEFs Asef and Tiam1, and the former specifically shows higher levels of interaction with peripheral microtubules (Higginbotham et al. 2014). KIF17 is a microtubule motor that interacts with the plus-end microtubule capture machinery at the cell cortex. Expression of KIF17 increases active RhoA and junctional actin levels, thereby stabilizing cell–cell contacts (Acharya et al. 2016). Although the GEF responsible for these effects is not known, these results suggest that modification of microtubule dynamics in more subtle ways also have an impact on RhoA signaling.

Our understanding on the modulation of keratin filaments and desmosomes by Rho GTPase signaling is emerging. Potential interaction of GTPase regulators with keratin filaments is poorly understood in epithelia (Todorovic et al. 2010; Dubash et al. 2013, 2014). An example has been reported in endothelial cells, where ARHGEF40 (SOLO), a RhoA GEF stimulated by mechanical stress, interacts with keratin8/18 filaments and its overexpression induces keratin bundling (Abiko et al. 2015; Fujiwara et al. 2016). It is likely that further studies will unravel similar interactions and regulatory events associated with keratin dynamics in epithelial cells.

Finally, treatment with different drugs that do not specifically target the cytoskeleton can unexpectedly alter the basal activity status of GTPases. To cite a few examples, inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) function (pharmacologically or via RNAi) can activate Rac1 and perturb cell–cell contacts (Betson et al. 2002; Erasmus et al. 2015). In contrast, inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTORC)1 and mTORC2 with rapamycin decreases the activation of both RhoA and Rac1, promotes cell–cell adhesion and reduces cell migration (Gulhati et al. 2011). Treatment with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) induces a transient dissociation of β-PIX from contractile actin filaments and concomitant activation of Rac1 (Lee et al. 2010). Such examples reinforce the complex interplay between structural components and the GEF/GAP signaling machinery and the need to understand GTPase signaling in a broader cellular architecture.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

GEFs, GAPs, and Rho small GTPases are localized to different intracellular spaces and structures via association with lipids, interaction with cytoskeletal proteins, microtubules and microfilaments. Although the key role of these interactions for localization of signaling has long been recognized, it now emerges that cytoskeletal partners provide networking capabilities to concatenate temporal enrolment of distinct signaling molecules in a particular place. Furthermore, direct interaction with cytoskeletal structures and proteins can influence the availability, extent and frequency of activation/inactivation cycles, thereby providing signaling fine-tuning. The intricate relationship between cytoskeletal structures and signaling at junctions provides an exciting platform to build our knowledge on how to integrate cell–cell adhesion with cellular function.

Footnotes

Editors: Carien M. Niessen and Alpha S. Yap

Additional Perspectives on Cell–Cell Junctions available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Abiko H, Fujiwara A, Ohashi K, Hiatari R, Mashiko T, Sakamoto N, Sato M, Mizuno K. 2015. Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors involved in cyclic-stretch-induced reorientation of vascular endothelial cells. J Cell Sci 128: 1683–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya BR, Espenel C, Libanje F, Raingeaud J, Morgan J, Jaulin F, Kreitzer G. 2016. KIF17 regulates RhoA-dependent actin remodeling at epithelial cell–cell adhesions. J Cell Sci 29: 957–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aijaz S, D’Atri F, Citi S, Balda MS, Matter K. 2005. Binding of GEF-H1 to the tight junction-associated adaptor cingulin results in inhibition of Rho signaling and G1/S phase transition. Dev Cell 8: 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alan JK, Lundquist EA. 2013. Mutationally activated Rho GTPases in cancer. Small GTPases 4: 159–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin E, Jaiswal M, Derewenda U, Reis K, Nouri K, Koessmeier KT, Aspenstrom P, Somlyo AV, Dvorsky R, Ahmadian MR. 2016. Deciphering the molecular and functional basis of RHOGAP family proteins: A systematic approach toward selective inactivation of rho family proteins. J Biol Chem 291: 20353–20371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos KS, Bigarella CL, Wagner MV, Vieira KP, Lazarini M, Langford PR, Machado-Neto JA, Call SG, Staley D, Chung JY, et al. 2013. ARHGAP21: A new partner of α-tubulin involved in cell–cell adhesion formation and essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem 288: 2179–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertocchi C, Rao MV, Zaidel-Bar R. 2012. Regulation of adherens junction dynamics by phosphorylation switches. J Signal Transd 2012: 125295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betson M, Lozano E, Zhang J, Braga VMM. 2002. Rac activation upon cell–cell contact formation is dependent on signaling from the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem 277: 36962–36969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga VMM, Betson M, Li X, Lamarche-Vane N. 2000. Activation of the small GTPase Rac is sufficient to disrupt cadherin-dependent cell–cell adhesion in normal human keratinocytes. Mol Biol Cell 11: 3703–3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breznau EB, Semack AC, Higashi T, Miller AL. 2015. MgcRacGAP restricts active RhoA at the cytokinetic furrow and both RhoA and Rac1 at cell–cell junctions in epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 26: 2439–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Nalbant P, Birkenfeld J, Chang ZF, Bokoch GM. 2008. GEF-H1 couples nocodazole-induced microtubule disassembly to cell contractility via RhoA. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2147–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Macara IG. 2005. Par-3 controls tight junction assembly through the Rac exchange factor Tiam1. Nature Cell Biol 7: 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chircop M. 2014. Rho GTPases as regulators of mitosis and cytokinesis in mammalian cells. Small GTPases 5: e29770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citi S, Guerrera D, Spadaro D, Shah J. 2014. Epithelial junctions and Rho family GTPases: The zonular signalosome. Small GTPases 5: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DR, Rossman KL, Der CJ. 2014. Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors: Regulators of Rho GTPase activity in development and disease. Oncogene 33: 4021–4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avino PP, Takeda T, Capalbo L, Zhang W, Lilley KS, Laue ED, Glover DM. 2008. Interaction between Anillin and RacGAP50C connects the actomyosin contractile ring with spindle microtubules at the cell division site. J Cell Sci 121: 1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devreotes P, Horwitz AR. 2015. Signaling networks that regulate cell migration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a005959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubash AD, Koetsier JL, Amargo EV, Najor NA, Harmon EM, Green KJ. 2013. The GEF Bcr activates RhoA/MAL signaling to promote keratinocyte differentiation via desmoglein-1. J Cell Biol 202: 653–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich JS, Hansen MD, Nelson WJ. 2002. Spatio-temporal regulation of Rac1 localization and lamellipodia dynamics during epithelial cell–cell adhesion. Dev Cell 3: 259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlicher AJ, Nakamura F, Hartwig JH, Weitz DA, Stossel TP. 2011. Mechanical strain in actin networks regulates FilGAP and integrin binding to filamin A. Nature 478: 260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbediwy A, Zihni C, Terry SJ, Clark P, Matter K, Balda MS. 2012. Epithelial junction formation requires confinement of Cdc42 activity by a novel SH3BP1 complex. J Cell Biol 198: 677–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus JC, Welsh NJ, Braga VM. 2015. Cooperation of distinct Rac-dependent pathways to stabilise E-cadherin adhesion. Cell Signal 27: 1905–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus JC, Bruche S, Pizarro L, Maimari N, Pogglioli T, Tomlinson C, Lees J, Zalivina I, Wheeler A, Alberts A, et al. 2016. Defining functional interactions during biogenesis of epithelial junctions. Nat Commun 7: 13542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo R, Jeng Y, Paulucci-Holthauzen A, Rengifo-Cam W, Honkus K, Anastasiadis PZ, Sastry SK. 2014. PTP-PEST targets a novel tyrosine site in p120 catenin to control epithelial cell motility and Rho GTPase activity. J Cell Sci 127: 497–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenette P, Haines E, Loloyan M, Kinal M, Pakarian P, Piekny A. 2012. An anillin-Ect2 complex stabilizes central spindle microtubules at the cortex during cytokinesis. PLoS ONE 7: e34888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara S, Ohashi K, Mashiko T, Kondo H, Mizuno K. 2016. Interplay between Solo and keratin filaments is crucial for mechanical force-induced stress fiber reinforcement. Mol Biol Cell 27: 954–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory SL, Ebrahimi S, Milverton J, Jones WM, Bejsovec A, Saint R. 2008. Cell division requires a direct link between microtubule-bound RacGAP and Anillin in the contractile ring. Curr Biol 18: 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot L, Guerrera D, Spadaro D, Tapia R, Jond L, Citi S. 2014. MgcRacGAP interacts with cingulin and paracingulin to regulate Rac1 activation and development of the tight junction barrier during epithelial junction assembly. Mol Biol Cell 25: 1995–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot L, Paschoud S, Jond L, Foglia A, Citi A. 2008. Paracingulin regulates the activity of Rac1 and RhoA GTPases by recruiting Tiam1 and GEF-H1 to epithelial junctions. Mol Biol Cell 19: 4442–4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulhati P, Bowen KA, Liu J, Stevens PD, Rychahou PG, Chen M, Lee EY, Weiss UL, O’Connor KL, Gao T, et al. 2011. mTORC1 and mTORC2 regulate EMT, motility, and metastasis of colorectal cancer via RhoA and Rac1 signaling pathways. Cancer Res 71: 3246–3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick J, Franz-Wachtel M, Moeller Y, Schmid S, Macek B, Olayioye MA. 2016. The polarity protein Scribble positions DLC3 at adherens junctions to regulate Rho signaling. J Cell Sci 129: 3583–3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham K, Tian Y, Gawlak G, Moldobaeva N, Shah A, Birukova AA. 2014. Hepatocyte growth factor triggers distinct mechanisms of Asef and Tiam1 activation to induce endothelial barrier enhancement. Cell Signal 26: 2306–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge RG, Ridley AJ. 2016. Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17: 496–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holeiter G, Bischoff A, Braun AC, Huck B, Erlmann P, Schmid S, Herr R, Brummer T, Olayioye MA. 2012. The RhoGAP protein deleted in liver cancer 3 (DLC3) is essential for adherens junctions integrity. Oncogenesis 1: e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huveneers S, de Rooij J. 2013. Mechanosensitive systems at the cadherin–F-actin interface. J Cell Sci 126: 403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh M, Tsukita S, Yamazaki Y, Sugimoto H. 2012. Rho GTP exchange factor ARHGEF11 regulates the integrity of epithelial junctions by connecting ZO-1 and RhoA-myosin II signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 9905–9910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenna S, Hussain NK, Danek EI, Triki I, Wasiak S, McPherson PS, Lamarche-Vane N. 2002. The activity of the GTPase-activating protein CdGAP is regulated by the endocytic protein intersectin. J Biol Chem 277: 6366–6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourtidis A, Ngok SP, Anastasiadis PZ. 2013. p120 catenin: An essential regulator of cadherin stability, adhesion-induced signaling, and cancer progression. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 116: 409–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs EM, Makar RS, Gertler FB. 2006. Tuba stimulates intracellular N-WASP-dependent actin assembly. J Cell Sci 119: 2715–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krendel M, Zenke FT, Bokosh GM. 2002. Nucleotide exchange factor GEF-H1 mediates crosstalk between microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton. Nat Cell Biol 4: 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladoux B, Nelson WJ, Yan J, Mege RM. 2015. The mechanotransduction machinery at work at adherens junctions. Integr Biol (Camb) 7: 1109–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam BD, Hordijk PL. 2013. The Rac1 hypervariable region in targeting and signaling: A tail of many stories. Small GTPases 4: 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Choi CK, Shin EY, Schwartz MA, Kim EG. 2010. Myosin II directly binds and inhibits Dbl family guanine nucleotide exchange factors: A possible link to Rho family GTPases. J Cell Biol 190: 660–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara IG, Guyer R, Richardson G, Huo Y, Ahmed SM. 2014. Epithelial homeostasis. Curr Biol 24: R815–R825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machacek M, Hodgson L, Welch C, Elliott H, Pertz O, Nalbant P, Abell A, Johnson GL, Hahn KM, Danuser G. 2009. Coordination of Rho GTPase activities during cell protrusion. Nature 461: 99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack NA, Porter AP, Whalley HJ, Schwarz JP, Jones RC, Khaja AS, Bjartell A, Anderson KI, Malliri A. 2012. Beta2-syntrophin and Par-3 promote an apicobasal Rac activity gradient at cell-cell junctions by differentially regulating Tiam1 activity. Nature Cell Biol 14: 1169–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manukyan A, Ludwig K, Sanchez-Manchinelly S, Parsons SJ, Stukenberg PT. 2015. A complex of p190RhoGAP–A and anillin modulates RhoA-GTP and the cytokinetic furrow in human cells. J Cell Sci 128: 50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marei H, Malliri A. 2016. Rac1 in human diseases: The therapeutic potential of targeting Rac1 signaling regulatory mechanisms. Small GTPases. 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J, Welsh NJ, Braga VM. 2013. Cycling around cell–cell adhesion with Rho GTPase regulators. J Cell Sci 126: 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens AEE, Rygiel TP, Olivo C, van der Kammen R, Collard JG. 2005. The Rac activator Tiam1 controls tight junction biogenesis in keratinocytes through binding to and activation of the Par polarity complex. J Cell Biol 170: 1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroya K, Kawasaki Y, Hayashi T, Ohwada S, Akiyama T. 2007. PH domain-mediated membrane targeting of Asef. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 355: 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara S, Tsutsumi K, Zuinen T, Ohta Y. 2015. FilGAP, a Rho-ROCK-regulated GAP for Rac, controls adherens junctions in MDCK cells. J Cell Sci 128: 2047–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Tanoue T. 2011. Lulu2 regulates the circumferential actomyosin tensile system in epithelial cells through p114RhoGEF. J Cell Biol 195: 245–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngok SP, Anastasiadis PZ. 2013. Rho GEFs in endothelial junctions: Effector selectivity and signaling integration determine junctional response. Tissue Barriers 1: e27132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngok SP, Geyer R, Kourtidis A, Mitin N, Feathers R, Der C, Anastasiadis PZ. 2013. TEM4 is a junctional Rho GEF required for cell-cell adhesion, monolayer integrity and barrier function. J Cell Sci 126: 3271–3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngok SP, Lin WH, Anastasiadis PZ. 2014. Establishment of epithelial polarity—GEF who’s minding the GAP? J Cell Sci 127: 3205–3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nola S, Daigaku R, Smolarczyk K, Carstens M, Martin-Martin B, Longmore G, Bailly M, Braga VM. 2011. Ajuba is required for Rac activation and maintenance of E-cadherin adhesion. J Cell Biol 195: 855–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren NK, Liu BP, Burridge K, Kreft B. 2000. p120 catenin regulates the actin cytoskeleton via Rho family GTPases. J Cell Biol 150: 567–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Otani T, Ikenouchi J, Furuse M. 2014. Tricellulin regulates junctional tension of epithelial cells at tricellular contacts through Cdc42. J Cell Sci 127: 4201–4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelchenko T, Hall A. 2012. Myosin-IXA regulates collective epithelial cell migration by targeting RhoGAP activity to cell-cell junctions. Curr Biol 22: 278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani T, Ichii T, Aono S, Takeichi M. 2006. Cdc42 GEF Tuba regulates the junctional configuration of simple epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 175: 135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak R, Delorme-Walker VD, Howell MC, Anselmo AN, White MA, Bokoch GM, Dermardirossian C. 2012. The microtubule-associated Rho activating factor GEF-H1 interacts with exocyst complex to regulate vesicle traffic. Dev Cell 23: 397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peglion F, Etienne-Manneville S. 2013. p120catenin alteration in cancer and its role in tumour invasion. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368: 20130015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekny AJ, Glotzer M. 2008. Anillin is a scaffold protein that links RhoA, actin, and myosin during cytokinesis. Curr Biol 18: 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutoni C, Bazellieres E, Le Borgne-Rochet M, Comunale F, Brugues A, Seveno M, Planchon D, Thuault S, Morin N, Bodin S, et al. 2016. P-cadherin promotes collective cell migration via a Cdc42-mediated increase in mechanical forces. J Cell Biol 212: 199–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponik SM, Trier SM, Wozniak MA, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ. 2013. RhoA is down-regulated at cell–cell contacts via p190RhoGAP-B in response to tensional homeostasis. Mol Biol Cell 24: 1688–1699, S1681–S1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter AP, Papaioannou A, Malliri A. 2016. Deregulation of Rho GTPases in cancer. Small GTPases 7: 123–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primeau M, Ben Djoudi Ouadda A, Lamarche-Vane N. 2011. Cdc42 GTPase-activating protein (CdGAP) interacts with the SH3D domain of Intersectin through a novel basic-rich motif. FEBS Lett 585: 847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya R, Wee K, Budnar S, Gomez GA, Yap AS, Michael M. 2016. Coronin 1B supports RhoA signaling at cell–cell junctions through myosin II. Cell Cycle 15: 3033–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi F, Felline A, Fanelli F. 2015. Catching functional modes and structural communication in Dbl family rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors. J Chem Info Model 55: 1878–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratheesh A, Gomez GA, Priya R, Verma S, Kovacs EM, Jiang K, Brown NH, Akhmanova A, Stehbens SJ, Yap AS. 2012. Centralspindlin and a-catenin regulate Rho signalling at the epithelial zonula adherens. Nature Cell Biol 14: 818–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes CC, Jin M, Breznau EB, Espino R, Delgado-Gonzalo R, Goryachev AB, Miller AL. 2014. Anillin regulates cell–cell junction integrity by organizing junctional accumulation of Rho-GTP and actomyosin. Curr Biol 24: 1263–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai X, Yonemura S, Ladher RK. 2014. Junctionally restricted RhoA activity is necessary for apical constriction during phase 2 inner ear placode invagination. Dev Biol 394: 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, Reinhard MR, Hordijk PL. 2014. Toward understanding RhoGTPase specificity: Structure, function and local activation. Small GTPases 5: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seipel K, O'Brien SP, Iannotti E, Medley QG, Streuli M. 2001. Tara, a novel F-actin binding protein, associates with the Trio guanine nucleotide exchange factor and regulates actin cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Sci 114: 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifrin Y, Arora PD, Ohta Y, Calderwood DA, McCulloch CA. 2009. The role of FilGAP–filamin A interactions in mechanoprotection. Mol Biol Cell 20: 1269–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluysmans S, Vasileva E, Spadaro D, Shah J, Rouaud F, Citi S. 2017. The role of apical cell–cell junctions and associated cytoskeleton in mechanotransduction. Biol Cell 109: 139–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strale PO, Duchesne L, Peyret G, Montel L, Nguyen T, Png E, Tampe R, Troyanovsky S, Henon S, Ladoux B, et al. 2015. The formation of ordered nanoclusters controls cadherin anchoring to actin and cell–cell contact fluidity. J Cell Biol 210: 333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su KC, Takaki T, Petronczki M. 2011. Targeting of the RhoGEF Ect2 to the equatorial membrane controls cleavage furrow formation during cytokinesis. Dev Cell 21: 1104–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaishi K, Sasaki T, Kotani H, Nishioka H, Takai Y. 1997. Regulation of cell–cell adhesion by Rac and Rho small G proteins in MDCK cells. J Cell Biol 139: 1047–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry SJ, Elbediwy A, Zihni C, Harris AR, Bailly M, Charras GT, Balda MS, Matter K. 2012. Stimulation of cortical myosin phosphorylation by p114RhoGEF drives cell migration and tumor cell invasion. PLoS ONE 7: e50188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V, Desai BV, Patterson MJ, Amargo EV, Dubash AD, Yin T, Jones JC, Green KJ. 2010. Plakoglobin regulates cell motility through Rho- and fibronectin-dependent Src signaling. J Cell Sci 123: 3576–3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V, Koetsier JL, Godsel LM, Green KJ. 2014. Plakophilin 3 mediates Rap1-dependent desmosome assembly and adherens junction maturation. Mol Biol Cell 25: 3749–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi V, Popescu NC, Zimonjic DB. 2012. DLC1 interaction with alpha-catenin stabilizes adherens junctions and enhances DLC1 antioncogenic activity. Mol Cell Biol 32: 2145–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu CL, You M. 2014. Obligatory roles of filamin A in E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion in epidermal keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci 73: 142–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valls G, Codina M, Miller RK, Del Valle-Perez B, Vinyoles M, Caelles C, McCrea PD, de Herreros AG, M. Dunach M. 2013. Upon Wnt stimulation, Rac1 activation requires Rac1 and Vav2 binding to p120-catenin. J Cell Sci 125: 5288–52301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buul JD, Geerts D, Huveneers S. 2014. Rho GAPs and GEFs: Controling switches in endothelial cell adhesion. Cell Adh Migr 8: 108–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan EM, Miller AL, Yu HY, Bement WM. 2011. Control of local Rho GTPase crosstalk by Abr. Curr Biol 21: 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello E, Ferreira JG, Maiato H, Balda MS, Matter K. 2014. The tumour suppressor DLC2 ensures mitotic fidelity by coordinating spindle positioning and cell–cell adhesion. Nat Commun 5: 5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells CD, Fawcett JP, Traweger A, Yamanaka Y, Goudreault M, Elder K, Kulkarni S, Gish G, Virag C, Lim K. 2006. A Rich1/Amot complex regulates the Cdc42 GTPase and apical-polarity proteins in epithelial cells. Cell 125: 535–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenberg GA, Dohn MR, Carnahan RH, Davis MA, Lobdell NA, Settleman J, Reynolds AB. 2006. p120-catenin and p190RhoGAP regulate cell-cell adhesion by coordinating antagonism between Rac and Rho. Cell 127: 1027–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Jin D, Durgan J, Hall A. 2013. LKB1 controls human bronchial epithelial morphogenesis through p114RhoGEF–dependent RhoA activation. Mol Cell Biol 33: 2671–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S, Matsuda M, Kiyokawa E. 2012a. Chimaerin suppresses Rac1 activation at the apical membrane to maintain the cyst structure. PLoS One 7: e52258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S, Matsuda M, Kiyokawa E. 2012b. Suppression of Rac1 activity at the apical membrane of MDCK cells is essential for cyst structure maintenance. EMBO Rep 13: 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano T, Yamazaki Y, Adachi YM, Okawa K, Fort P, Uji M, Tsukita S. 2011. Tara up-regulates E-cadherin transcription by binding to the Trio RhoGEF and inhibiting Rac signaling. J Cell Biol 193: 319–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Nelson WJ. 2007. Localized zones of Rho and Rac activities drive initiation and expansion of epithelial cell–cell adhesion. J Cell Biol 178: 517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R. 2013. Cadherin adhesome at a glance. J Cell Sci 126: 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R, Zhenhuan G, Luxenburg C. 2015. The contractome - a systems view of actomyosin contractility in non-muscle cells. J Cell Sci 128: 2209–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebda N, Tian Y, Tian X, Gawlak G, Higginbotham K, Reynolds AB, Birukova AA, Birukov KG. 2013. Interaction of p190RhoGAP with C-terminal domain of p120-catenin modulates endothelial cytoskeleton and permeability. J Biol Chem 288: 18290–18299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y, Oh W, Frost JA. 2014. Controlling the switches: Rho GTPase regulation during animal cell mitosis. Cell Signal 26: 2998–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]