Abstract

Background

Altered gait mechanics following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLr) are commonly reported in the surgical limb 2–3 months post-surgery when normalization of gait is expected clinically. Specifically, deficits in knee extensor moment during loading response of gait are found to persist long-term; however, the mechanisms by which individuals reduce sagittal plane knee loading during gait are not well understood.

Research question

This study investigated between limb asymmetries in knee flexion range of motion, shank angular velocity, and ground reaction forces to determine the strongest predictor of knee extensor moment asymmetries during gait.

Methods

Thirty individuals 108 ± 17 days post-ACLr performed walking gait at a self-selected speed and peak knee extensor moment, peak vertical and posterior ground reaction force, and peak anterior shank angular velocity were identified during loading response. Paired t-tests compared limbs; Pearson’s correlations determined associations between variables in surgical and non-surgical limbs; and stepwise linear regression determined the best predictor of knee extensor moment asymmetries during gait.

Results

Reduced vertical and posterior ground reaction forces and shank angular velocity were strongly associated with reduced knee extensor moment in both limbs (r = 0.499–0.917, p < 0.005). Less knee flexion range of motion was associated with reduced knee moment in the surgical limb (r = 0.358, p < 0.05). Additionally, asymmetries in posterior ground reaction force and knee flexion range of motion predicted asymmetries in knee extensor moment (R2 = 0.473, p < 0.001).Significance: Modulation of kinetics and kinematics contribute to decreases in knee extensor moments during gait and provide direction for targeted interventions to restore gait mechanics.

Keywords: ACL reconstruction, gait impairments, knee extensor moment, shank angular velocity, ground reaction force

1.0. INTRODUCTION

Clinically, restoration of gait mechanics following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLr) is expected by 2–3 months post-surgery [1,2]. However, despite concentrated efforts to normalize gait, biomechanical studies consistently report the presence of altered mechanics in the surgical limb. Decreased knee flexion range of motion (ROM) and extensor moments during loading response of gait are observed throughout rehabilitation [3–7]. Moreover, despite improvements over time, between limb asymmetries in knee extensor moment continue to exceed the minimal clinically important difference 2 years after surgery [8]. These alterations have been attributed to the progression of knee joint osteoarthritis in an already vulnerable population [9,10]. Given the repetitive nature of gait and its importance in daily activities, it is important to ameliorate these impairments in early rehabilitation post-ACLr.

While many studies have quantified deficits in knee mechanics following ACLr, the mechanisms by which individuals reduce sagittal plane knee loading is not well understood. Altered knee mechanics are commonly reported during loading response, a time at which individuals are loading the limb and transitioning to single limb stance [11] At 3–5 months post- ACLr, deficits of up to 4 degrees in knee flexion ROM and up to 50% in knee extensor moment have been reported [4,5,12,13]. Following initial contact, during loading response, rapid knee flexion of 15 degrees and eccentric knee extensor control are required to decelerate and progress the body over the stance limb [11]. This is accomplished using heel rocker mechanics in unimpaired gait and is characterized by rapid forward progression of the shank over the heel immediately after ground contact [11]. The presence of decreased shank angular velocity in the surgical limb along with decreased knee flexion ROM suggests that individuals may alter kinematics during the heel rocker mechanism to reduce extensor loading [7,14]. This is supported in part by a recent study that found that 57.5% of the variance in knee extensor moment deficits in individuals 3 months post-ACLr were explained by shank angular velocity deficits during loading response [7].

In addition to altering joint and segment kinematics, it is conceivable that individuals modulate ground reaction forces (GRFs) to limit sagittal plane knee loading. Sagittal plane joint moment calculations are influenced by GRF magnitude in both vertical and anteroposterior directions [15]. To date, no study has evaluated vertical GRFs during gait in early rehabilitation following ACLr. However, between limb differences in vertical GRFs loading rate in individuals 4 years post-ACLr suggest that individual alter GRFs following surgery [16]. It is not known if these alterations are present during early rehabilitation or if they contribute to reduced knee extensor moments. Following initial contact, the posterior GRF helps to slow forward momentum of the body and allows the stance limb to achieve weight-bearing stability [11]. Posterior GRFs are reflective of braking forces and are resisted by the knee extensors in loading response. As no previous work has investigated anteroposterior GRFs, it is not known if individuals modulate these forces to reduce sagittal plane knee loading following ACLr. While alterations in kinematics that explain decreased sagittal plane loading of the knee are well documented, a critical understanding of how individuals modulate GRFs in early rehabilitation is lacking.

A comprehensive understanding of the mechanical factors that relate to reduce knee loading during gait in individuals following ACLr is needed to develop interventions to target these deficits. Identifying deficits early in rehabilitation and developing targeted interventions is crucial for long-term joint health. The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the mechanics associated with reduced knee extensor moments by determining the strongest predictor of knee extensor moment asymmetries during gait following ACLr from between limb asymmetries in kinematics and ground reaction forces. To do this, we determined if there were differences between limbs in these variables, as well as the relationship of these variables to knee extensor moments in each limb. It was hypothesized that between limb asymmetries in knee range of motion, vertical and posterior ground reaction force, or shank angular velocity would be predictive of between limb asymmetries in knee extensor moment.

2.0. METHODS

Thirty individuals 108 ± 17 days post-ACLr were enrolled (Table 1). Three participants reported previous ACLr to the contralateral (n=l) and ipsilateral knee (n=2) of greater than 4 years. Those with a history of ACLr had returned to pre-surgical levels of physical activity prior to re-injury. Participants were included in the study if they were between the ages of 14–50, 10– 20 weeks status-post ACLr, and currently participating in physical therapy. Participants were excluded if they had a current injury to the contralateral limb that would influence function or a concurrent knee pathology that limited their weight bearing status.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Age (years) | 28 ± 12 |

| Sex | 10 M/20 F |

| Height (cm) | 169.0 ± 9.4 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.5 ± 12.6 |

| Days post-ACLr | 108 ± 17 |

| Graft Type (n) | |

| Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone autograft | 14 |

| Hamstring autograft | 3 |

| Quad tendon autograft | 2 |

| Allograft | 11 |

| IKDC score | 63.2 ± 12.8 |

| Knee pain, VAS score (cm) | 0.41 ± 0.72 |

Note: All values are mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. VAS: visual analog scale

2.1. Procedures

Testing took place at the University of Southern California’s Human Performance Laboratory located at the Competitive Athletes Training Zone (Pasadena, CA). All procedures were explained to each participant and an informed consent was obtained as approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus. Parental consent and youth assent were obtained for participants under the age of 18 years.

Prior to testing, participants warmed-up on a stationary bike for five minutes and completed self-reported measures of knee function (IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form) and knee pain (VAS). Next, reflective markers (25mm spheres) were placed bilaterally over the following anatomical landmarks: 1st and 5th metatarsal heads, the distal end of the second toe, medial and lateral malleoli, medial and lateral femoral epicondyles, greater trochanters, iliac crests, posterior superior iliac spines, and the L5-S1 junction. Additionally, tracking marker clusters, reflective markers secured to rigid plates, were placed bilaterally on the lateral surfaces of the subject’s thigh, shank, and the heel of their shoe. After a static calibration trial, all markers were removed except for tracking marker clusters, pelvis markers, and distal toe markers, which remained on the participant during gait analysis.

Kinematic and GRF data were collected using a 14-camera digital motion capturing system (250 Hz) and force platforms (1000 Hz; BTS Bioengineering Corporation, Brooklyn, NY). Kinematic and kinetic data were collected synchronously using BTS SMART Capture software (version 1.10).

Participants were instructed to walk at a comfortable self-selected speed across a IOmeter path. Walking velocity was determined using laser timing gates placed 5 meters apart centered on either side of the force plates. Participants became familiar with the instrumentation during several practice trials, where self-selected walking speed was determined. Four acceptable trials for each limb were collected. A trial was considered acceptable if full foot contact was made on the force platform and if gait velocity fell within 5% of their self-selected velocity.

2.2. Data Analysis

Three-dimensional marker-coordinates were reconstructed (BTS SMART Tracker) and synchronized with GRF data. Together, they were used to calculate sagittal plane joint kinematics and kinetics (VisuaBD, version 5, C-Motion, Inc., Germantown, MD). Coordinate and GRF data were low-pass filtered using a fourth order zero-lag Butterworth filter with 12-Hz and 40 Hz cut-offs, respectively [17] Local coordinate systems of the body segments were derived from the standing calibration using a joint coordinate system approach [18]. Lower extremity segments were modeled as frustra of cones, and the pelvis was modeled as a cylinder. Six degrees-of-freedom of each segment were calculated by transforming the triad of markers on the marker clusters to the position and orientation of each segment during the standing calibration trial. Body mass was calculated using vertical GRF during the static trial. Average vertical force (5 seconds) was divided by 9.81 N/kg to determine body weight. Kinematics, anthropometrics and GRFs were used in standard inverse dynamics equations to calculate internal knee extensor net joint moment [19]. Net joint moment was normalized to body mass and expressed in Nm/kg.

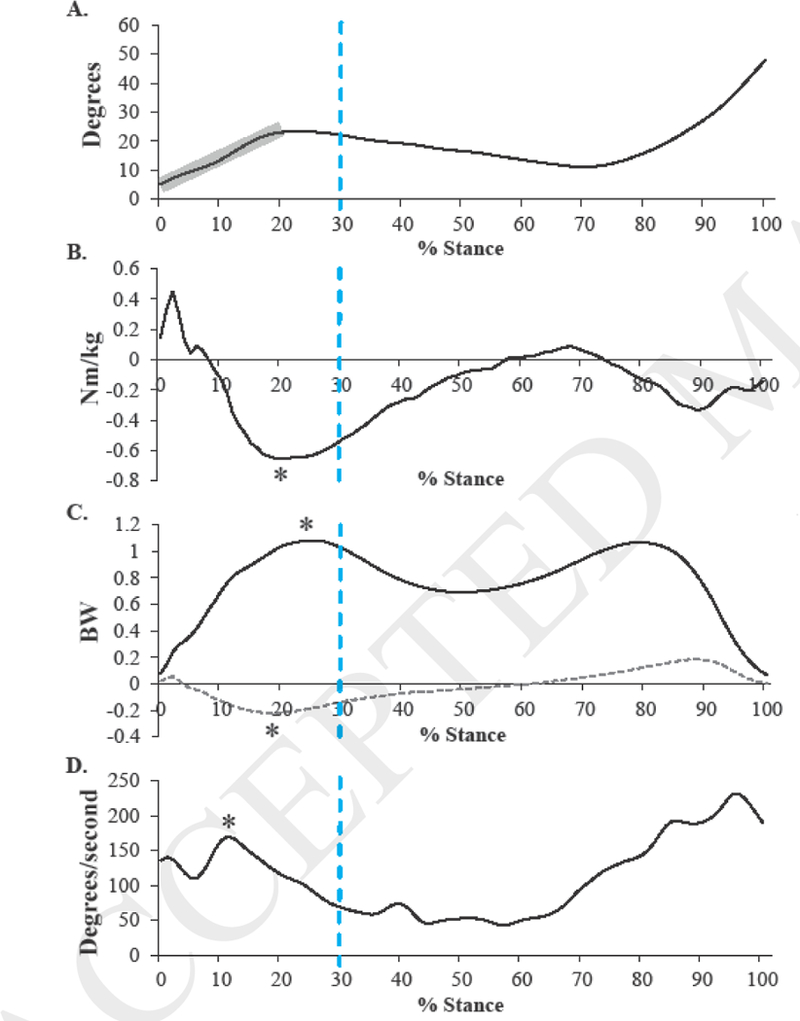

Data were analyzed during the initial loading phase from 0–30% of stance. Initial contact was determined using a threshold of 30N for vertical GRF. GRF data were normalized to body weight and expressed in body weights (BW). Five dependent variables of interest were identified for surgical and non-surgical limbs (Figure 1): peak knee extensor moment, knee flexion ROM, peak vertical GRF, peak posterior GRF, and maximum shank angular velocity. Knee flexion ROM was calculated from initial contact to peak knee flexion. Maximum shank angular velocity was identified after heel strike, where positive angular velocity was anterior rotation of the shank. All dependent variables were identified using a customized MATLAB program (version 2015b, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). The average of four trials for each limb was used for analysis.

Figure 1.

Representative time series plots for (A) knee angle, (B) knee moment, (C) vertical (solid black line) and posterior (dashed gray line) ground reaction force, and (D) shank angular velocity. Vertical dashed line indicates 30% of stance. Shaded area highlights where knee flexion range of motion was calculated. Asterisks indicate peak where each dependent variable was identified.

Between limb ratios were calculated for knee extensor moment, vertical and posterior GRFs, and shank angular velocity using the following equation: ratio = surgical /non-surgical limb, where a ratio less than 1 indicates that the surgical limb is smaller than the non-surgical limb. Between limb differences in knee flexion ROM were calculated, where a negative value indicates that the surgical limb is smaller than the non-surgical limb.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Paired t-tests were used to compare knee extensor moment, knee flexion ROM, vertical and posterior GRFs, and shank angular velocity between limbs. A Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple comparisons, whereby the alpha level was divided by the number of comparisons. Pearson’s product-moment correlations were used to investigate the relationship between knee extensor moment and knee ROM, vertical GRF, posterior GRF, and shank angular velocity separately in the surgical and non-surgical limbs. Moderate and strong correlations were defined as coefficients between 0.3 and 0.5 and 0.5 and 1.0, respectively [5]. Stepwise linear regression was used to determine the best predictor of knee extensor moment ratio from between limb differences in knee ROM, posterior GRF ratio, vertical GRF ratio, and shank angular velocity ratio. Standard assumptions of linear regression were met including: approximately linear relationship between predictor variables and outcome variable, homogeneity of variances, and normal distribution of residuals. Additionally, multicollinearity was checked in the final regression model, as variance inflation factors were less than 4 [20]. Significance level was set at α=0.05 (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL).

3.0. RESULTS

All data were reported as mean (SD). On average, the surgical limb exhibited reduced knee extensor moment (−0.135(0.224) Nm/kg; p=0.003), knee flexion ROM (−4.1(4.1) degrees; p<0.001), posterior GRF (−0.020(0.036) BW; p=0.005), and shank angular velocity (−16.6(30.6) degrees/second; p=0.006) compared to the non-surgical limb (Table 2). Vertical GRF did not differ between limbs (−0.032(0.096) BW; p=0.079).

Table 2.

Mean ± standard deviations and between limb comparisons

| Surgical limb | Non-surgical limb | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knee extensor moment (Nm/kg) | 0.605 ±0.335 | 0.740 ±0.357 | 0.003a |

| Knee flexion ROM (degrees) | 12.84 ± 5.08 | 16.92 ±4.30 | <0.001a |

| Vertical GRF (BW) | 1.056 ± 0.138 | 1.088 ±0.119 | 0.079 |

| Posterior GRF (BW) | 0.206 ±0.057 | 0.226 ±0.053 | 0.005a |

| Shank angular velocity (degrees/second) | 176.28 ±26.18 | 192.85 ±26.23 | 0.006a |

Note: Significant differences between limbs.

In the surgical limb, strong positive correlations were found between knee extensor moment and vertical GRF, posterior GRF, and shank angular velocity (Table 3). A moderate positive correlation was found between knee extensor moment and knee ROM in the surgical limb. In the non-surgical limb, strong positive correlations were observed between knee extensor moment and posterior GRF and vertical GRF (Table 3). A moderate positive correlation was found between knee extensor moment and shank angular velocity in the non-surgical limb. Knee ROM was not significantly correlated with knee extensor moment in the non-surgical limb. Greater posterior and vertical GRF and shank angular velocity were related to greater knee extensor moments in both surgical and non-surgical limbs, while greater knee ROM was related to greater knee extensor moment only in the surgical limb.

Table 3.

Correlations between variables of interest during loading response of gait

| Surgical Limb | Non-surgical Limb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee extensor moment |

Knee flexion ROM |

Vertical GRF |

Posterior GRF |

Knee extensor moment |

Knee flexion ROM |

Vertical GRF |

Posterior GRF |

||

| Knee flexion ROM |

0.358* | Knee flexion ROM |

0.089 | ||||||

| Vertical GRF |

0.833† | 0.393* | Vertical GRF |

0.828† | 0.140 | ||||

| Posterior GRF |

0.831† | 0.280 | 0.874† | Posterior GRF |

0.917† | 0.090 | 0.843† | ||

| Shank angular velocity |

0.698† | 0.455* | 0.801† | 0.841† | Shank angular velocity |

0.499† | 0.426* | 0.494† | 0.588† |

Note: p < 0.05;

p < 0.005

Between limb knee extensor moment ratios were, on average, 0.86±0.37 and ranged from 0.44 to 1.80. When considering predictors of between limb ratios of knee extensor moment, posterior GRF ratio and differences in knee ROM entered the prediction equation (R2=0.473, p<0.001). Posterior GRF ratio was the first to enter the equation (R2=0.363, p<0.001). After controlling for the effects of posterior GRF, differences in knee ROM entered the equation (R2 change=0.11, p=0.025). Vertical GRF ratio (p=0.869) and shank angular velocity ratio (p=0.126) did not enter the regression model.

4.0. DISCUSSION

These data are consistent with the literature during early rehabilitation highlighting deficits in knee extensor loading in the surgical knee during loading response of gait [4,5,7]. Self-reported knee pain during testing and IKDC scores suggest that participants were progressing typically [21]. On average, knee extensor moments were 26% smaller in the surgical compared to the non-surgical limb. Only 7 out of 30 participants exhibited knee extensor moment ratio symmetry between limbs (0.85–1.15), and 21 participants exhibited decreased moments in the surgical limb ranging from 26.7–82.6% of the non-surgical limb.

This study is the first to define the contributions of GRFs and kinematics to knee extensor loading during gait following ACLr. It is not surprising that smaller posterior and vertical GRFs were strongly related to smaller knee extensor moments in both limbs as they are primary inputs to the calculation of moments. In the surgical limb, posterior GRFs were 10% smaller compared to the non-surgical limb. Given the relationship between posterior GRF and knee extensor moment, this between limb deficit suggests that individuals 3 months post-ACLr modulate braking forces to reduce knee extensor loading. No differences were observed between limbs in vertical GRF, suggesting that despite the relationship between vertical GRF and extensor moment, this variable is not modulated in the surgical limb. This may be attributed to the fact that vertical GRFs are modulated by walking velocity which is the same between limbs [11].

On average, knee flexion ROM and shank angular velocity were smaller in the surgical limb than the non-surgical limb and were related to knee extensor moments. Small between limb asymmetries in knee flexion (on average, 4 degrees) were observed. Only 11 participants demonstrated knee flexion differences greater than 5 degrees. Reduced knee flexion ROM was related to smaller knee extensor moments, but only in the surgical limb. Shank angular velocity was decreased by 9% in the surgical limb, which is similar to previous studies [5,7]. Consistent with a previous study [7], reduced shank angular velocity was related to smaller knee extensor moments. This relationship was observed in both surgical and non-surgical limbs, with a stronger relationship observed in the surgical limb. Consistent deficits in sagittal plane kinematics in the surgical limb and their relationship to knee extensor moments supports the notion that alterations in heel rocker kinematics can reduce surgical limb knee loading.

Both kinematic and kinetic variables were found to predict knee extensor moment deficits. Between limb ratios were considered in a regression equation to reflect individual deficits and their contributors. Of the variables considered, posterior GRF ratio and knee ROM asymmetries were the only predictors of knee extensor moment ratio, together explaining 47.3% of the variance. Posterior GRFs alone explained 36% of the variance, supporting the premise that individuals 3 months post-ACLr modulate braking forces to reduce knee extensor loading. Despite the small differences between limbs in knee flexion ROM, they explained an additional 11% of the variance. This highlights the importance of fully restoring kinematics, even when small differences in ROM exist. Vertical GRF ratio and shank angular velocity ratio were not predictive of deficits in knee loading. It is not surprising that vertical GRF ratio did not factor into the prediction equation given the absence of between limb differences. However, Sigward and colleagues [7] previously found that shank angular velocity ratio extracted from inertial sensors was strongly predictive of knee extensor moment ratio, although shank angular velocity was the only variable considered. Consistent with these findings, shank angular velocity was correlated with knee extensor moment in this population; however, the findings from the current study suggest that modulation of kinetics (braking forces) and kinematics (knee flexion) underlie decreases in knee extensor moments during gait.

The long-term persistence of altered knee mechanics and their potential implications for joint degeneration suggests that a greater emphasis on the restoration of gait mechanics in early rehabilitation is needed. Knee extensor moment deficits of greater than 15% were observed in 63% of the participants in this study. These altered mechanics are present at 3 months post- ACLr, a time when clinical normalization of gait is expected. Given the difficulty in detecting small differences in knee flexion ROM during gait clinically, it is not surprising that these deficits persist. The identification of potentially modifiable variables, particularly posterior GRF and knee flexion, will inform gait interventions targeted at restoring gait mechanics during early rehabilitation post-ACLr. Future work is needed to explore mechanisms for targeting deficits in posterior GRF and knee ROM during gait and their efficacy in to improve knee loading.

This study had several limitations. An additional 53% of the variance in knee extensor moment deficits was unexplained. Other potential predictor variables that could account for the remaining variance in knee extensor moment ratio may include alterations in joint level muscle dynamics (timing and/or muscle contraction) or subtle alterations in whole body mechanics. Comparisons between limbs using ratios utilizes the non-surgical limb as a reference and allows for comparisons of variables that may be influenced by other factors including walking velocity, shoe wear or walking surface. The assumption that the non-surgical limb exhibits normal gait mechanics may not be accurate, limiting the interpretation of our results. However, it provides the best frame of reference for within subject comparisons. The participants in this study represent a group of individuals who are in the early stages of rehabilitation but at a time in which their gait was clinically normalized. While individuals with previous ACLr were included, only one participant had reconstructive surgery on the contralateral limb. As the results were similar when considering the analysis without this participant, these data were not removed. Furthermore, without longitudinal data, it is not known how these deficits resolve or persist over time.

5.0. CONCLUSION

This study concurrently highlights between limb differences in sagittal plane knee loading, ROM, posterior GRF, and shank angular velocity at a time when gait is expected to be normalized post-ACLr. Reduced vertical and posterior GRFs and shank angular velocity were strongly associated with reduced knee loading in both limbs. Less knee flexion ROM was associated with reduced knee loading only in the surgical limb. Further, asymmetries in posterior GRF and knee ROM predicted asymmetries in knee extensor moment. These data provide insight into the mechanism by which individuals reduce knee extensor loading in the surgical limb and highlight the importance of restoration of gait mechanics during early rehabilitation.

Highlights.

Deficits in kinematics and kinetics are present during gait 3 months post-ACLr.

GRF, shank angular velocity and knee flexion relate to knee extensor moment in gait.

Asymmetries in posterior GRF and knee flexion predict knee extensor deficits.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by grant # K12 HD0055929 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Health Sciences Campus of the University of Southern California.

The authors would like to acknowledge CATZ Physical Therapy and Sports Performance Center for their support and assistance with this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Paige E. Lin, Human Performance Laboratory, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, University of Southern California, 1540 Alcazar St, CHP 155, Los Angeles, CA, 90089-9006, United States. paigeeli@usc.edu, Tel.: +1-323-442-2948.

Susan M. Sigward, Human Performance Laboratory, Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, University of Southern California, 1540 Alcazar St, CHP 155, Los Angeles, CA, 90089-9006, United States. sigward@usc.edu, Tel.: +1-323-442-2454.

References

- [1].Manal TJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression, Oper. Tech. Orthop. 6 (1996), 190–196. doi: 10.1016/S1048-6666(96)80019-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].van Grinsven S, van Cingel REH, Holla CJM, van Loon CJM, Evidence-based rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction., Knee Surgery, Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc. 18 (2010) 1128–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-1027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Di Stasi SL, Logerstedt D, Gardinier ES, Snyder-Mackler L, Gait patterns differ between ACL-reconstructed athletes who pass return-to-sport criteria and those who fail., Am. J. Sports Med. 41 (2013) 1310–1318. doi: 10.1177/0363546513482718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].DeVita P, Hortobagyi T, Barrier J, Gait biomechanics are not normal after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and accelerated rehabilitation., Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 30(1998) 1481–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sigward SM, Lin P, Pratt K, Knee loading asymmetries during gait and running in early rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A longitudinal study., Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon). 32 (2016) 249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].White K, Logerstedt D, Snyder-Mackler L, Gait asymmetries persist 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction., Orthop. J. Sport. Med. 1 (2013) 1–6. doi: 10.1177/2325967113496967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sigward SM, Chan M-SM, Lin PE, Characterizing knee loading asymmetry in individuals following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using inertial sensors., Gait Posture. 49 (2016) 114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Roewer BD, Di Stasi SL, Snyder-Mackler L, Quadriceps strength and weight acceptance strategies continue to improve two years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction., J. Biomech. 44 (2011) 1948–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chaudhari AMW, Briant PL, Bevill SL, Koo S, Andriacchi TP, Knee kinematics, cartilage morphology, and osteoarthritis after ACL injury., Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 40 (2008) 215–222. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815cbb0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Andriacchi TP, Miindermann A, The role of ambulatory mechanics in the initiation and progression of knee osteoarthritis., Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 18 (2006) 514–518, doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000240365.16842.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Perry J, Burnfield JM, Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function, 2nd ed., SLACK Inc, Thorofare, NJ, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lewek M, Rudolph K, Axe M, Snyder-Mackler L, The effect of insufficient quadriceps strength on gait after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction., Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon). 17 (2002) 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Decker MJ, Torry MR, Noonan TJ, Sterett WI, Steadman JR, Gait retraining after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction., Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 85 (2004) 848–856. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Patterson MR, Delahunt E, Sweeney KT, Caulfield B, An ambulatory method of identifying anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed gait patterns., Sensors. 14 (2014) 887–899. doi: 10.3390/sl40100887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Winter DA, Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement, 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Blackburn JT, Pietrosimone B, Harkey MS, Luc BA, Pamukoff DN, Inter-limb differences in impulsive loading following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in females., J. Biomech. 49 (2016) 3017–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wellsandt E, Gardinier ES, Manal K, Axe MJ, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L, Decreased knee joint loading associated with early knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury., Am. J. Sports Med. 44 (2016) 143–151. doi: 10.1177/0363546515608475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Grood ES, Suntay WJ, A joint coordinate system for the clinical description of three- dimensional motions: Application to the knee, Trans. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 105 (1983) 136–144. doi: 10.1115/1.3138397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bresler B, Frankel JP, The forces and moments in the leg during level walking, Trans. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 72 (1950) 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Barton B, Peat J, Analyses of longitudinal data with the mixed model, in: Med. Stat. A Guid. to SPSS, Data Anal. Crit. Apprais, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, Hoboken, NJ, 2014: pp. 198–248. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chmielewski TL, Jones D, Day T, Tillman SM, Lentz TA, George SZ, The Association of Pain and Fear of Movement/Reinjury With Function During Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Rehabilitation, J. Orthop. Sport. Phys. Ther. 38 (2008) 746–753. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]