Atherosclerosis preferentially develops in areas of disturbed flow. Albarrán-Juárez et al. provide evidence that this depends on at least two different endothelial mechanosignaling pathways, a flow direction-independent pathway involving Piezo1 and Gq/G11, as well as integrin signaling, which is only initiated in response to disturbed flow.

Abstract

The vascular endothelium is constantly exposed to mechanical forces, including fluid shear stress exerted by the flowing blood. Endothelial cells can sense different flow patterns and convert the mechanical signal of laminar flow into atheroprotective signals, including eNOS activation, whereas disturbed flow in atheroprone areas induces inflammatory signaling, including NF-κB activation. How endothelial cells distinguish different flow patterns is poorly understood. Here we show that both laminar and disturbed flow activate the same initial pathway involving the mechanosensitive cation channel Piezo1, the purinergic P2Y2 receptor, and Gq/G11-mediated signaling. However, only disturbed flow leads to Piezo1- and Gq/G11-mediated integrin activation resulting in focal adhesion kinase-dependent NF-κB activation. Mice with induced endothelium-specific deficiency of Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 show reduced integrin activation, inflammatory signaling, and progression of atherosclerosis in atheroprone areas. Our data identify critical steps in endothelial mechanotransduction, which distinguish flow pattern-dependent activation of atheroprotective and atherogenic endothelial signaling and suggest novel therapeutic strategies to treat inflammatory vascular disorders such as atherosclerosis.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disorder of large and medium-sized arteries that predisposes to myocardial infarction and stroke, which are leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators, 2016). It is promoted by various risk factors including high plasma levels of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, inflammatory mediators, diabetes mellitus, obesity, arterial hypertension, and sedentary lifestyle (Herrington et al., 2016). However, in addition to these systemic factors, the local arterial microenvironment strongly influences the development of atherosclerotic lesions. Most strikingly, atherosclerosis develops selectively in curvatures, branching points, and bifurcations of the arterial system where blood flow is disturbed, while areas exposed to high laminar flow are largely resistant to atherosclerosis development (Hahn and Schwartz, 2009; Chiu and Chien, 2011; Tarbell et al., 2014).

Multiple evidence shows that high laminar flow and disturbed flow induce different signal transduction processes in endothelial cells resulting in an anti- or pro-atherogenic phenotype, respectively (Hahn and Schwartz, 2009; Chiu and Chien, 2011; Nigro et al., 2011; Tarbell et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014; Gimbrone and García-Cardeña, 2016; Givens and Tzima, 2016; Yurdagul et al., 2016; Nakajima and Mochizuki, 2017). Disturbed flow promotes inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB activation, resulting in the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules including VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, as well as chemokines including CCL2 (Mohan et al., 1997; Nagel et al., 1999; Feaver et al., 2010). Activation of inflammatory signaling by disturbed flow has been shown to involve a mechanosignaling complex consisting of PECAM-1, VE-cadherin, and VEGFR2 (Tzima et al., 2005), as well as activation of integrins (Finney et al., 2017). The PECAM-1/VE-cadherin/VEGFR2-mechanosignaling complex is also involved in high laminar shear stress-induced activation of anti-atherogenic signaling and, under this condition, regulates AKT to phosphorylate and activate eNOS (Fleming et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2015). Laminar flow-induced activation of this pathway has been shown to be dependent on the cation channel Piezo1, which mediates flow-induced release of ATP from endothelial cells, resulting in the activation of the Gq/G11-coupled purinergic P2Y2 receptor (Wang et al., 2015, 2016). How distinct flow patterns induce different endothelial phenotypes has, however, remained largely unclear.

Different flow patterns have a strong effect on the morphology of endothelial cells in that endothelial cells in areas of high laminar shear elongate and align in the direction of flow, whereas cells under disturbed flow fail to do so (Davies, 2009). In consequence, cells under sustained laminar flow receive flow only in the direction of the cell axis, whereas cells in areas of disturbed flow are randomly oriented and are exposed to flow at many different angles. Recent data suggest that the response of endothelial cells to flow is determined by the direction of flow relative to the morphological and cytoskeletal axis of the endothelial cell (Wang et al., 2013). When endothelial cells that had been preflowed to induce alignment were exposed to laminar flow in the direction of the cell axis, maximal eNOS activation was observed, while eNOS activation was undetectable when the flow direction was perpendicular to the cell axis. In contrast, activation of NF-κB was maximal at 90 degrees and undetectable when cells received flow parallel to the cell axis (Wang et al., 2013). This would explain why disturbed flow promotes inflammatory signaling, whereas sustained laminar flow promotes anti-inflammatory signaling. However, the molecular and cellular mechanisms mediating the activation of pro- and anti-atherogenic signaling depending on the flow direction are unclear.

Here we show that both laminar and disturbed flow activate the same initial mechanosignaling pathway involving Piezo1- and Gq/G11-mediated signaling. However, depending on the flow pattern, endothelial cells read these signaling processes out as either atheroprotective signaling resulting in eNOS activation or as inflammatory signaling resulting in NF-κB activation. This differential cell response to the initial mechanotransduction process depends on the activation of α5 integrin, which is activated only by disturbed flow, but not by sustained laminar flow.

Results

Endothelial inflammation induced by disturbed flow requires Piezo1 and Gq/G11-mediated signaling

We have previously shown that Gq/G11-mediated signaling plays a critical role in mediating laminar flow-induced eNOS activation in endothelial cells by coupling Piezo1-mediated mechanotransduction via the PECAM-1/VE-cadherin/VEGFR2 complex to phosphorylation and activation of eNOS (Wang et al., 2015, 2016). To test the role of Gq/G11-mediated signaling in the activation of inflammatory signaling induced by disturbed flow, we exposed human umbilical artery endothelial cells (HUAECs) to oscillatory flow. As described before (Mohan et al., 1997), disturbed flow induced NF-κB activation as indicated by phosphorylation of p65 at serine 536 (Fig. 1 A). Surprisingly, disturbed flow-induced inflammatory signaling was blocked after knock-down of P2Y2, as well as Gαq and Gα11 (Fig. 1 A and Fig. S1 A). Very similar data were obtained after knock-down of Piezo1 (Fig. 1 A and Fig. S1 A), which has been shown to operate upstream of P2Y2 and Gq/G11 by mediating flow-induced endothelial ATP-release (Wang et al., 2016). We also found that, similar to laminar flow (Bodin et al., 1991; John and Barakat, 2001; Yamamoto et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016), disturbed flow also induces ATP release from endothelial cells in a Piezo1-dependent manner (Fig. 1 B).

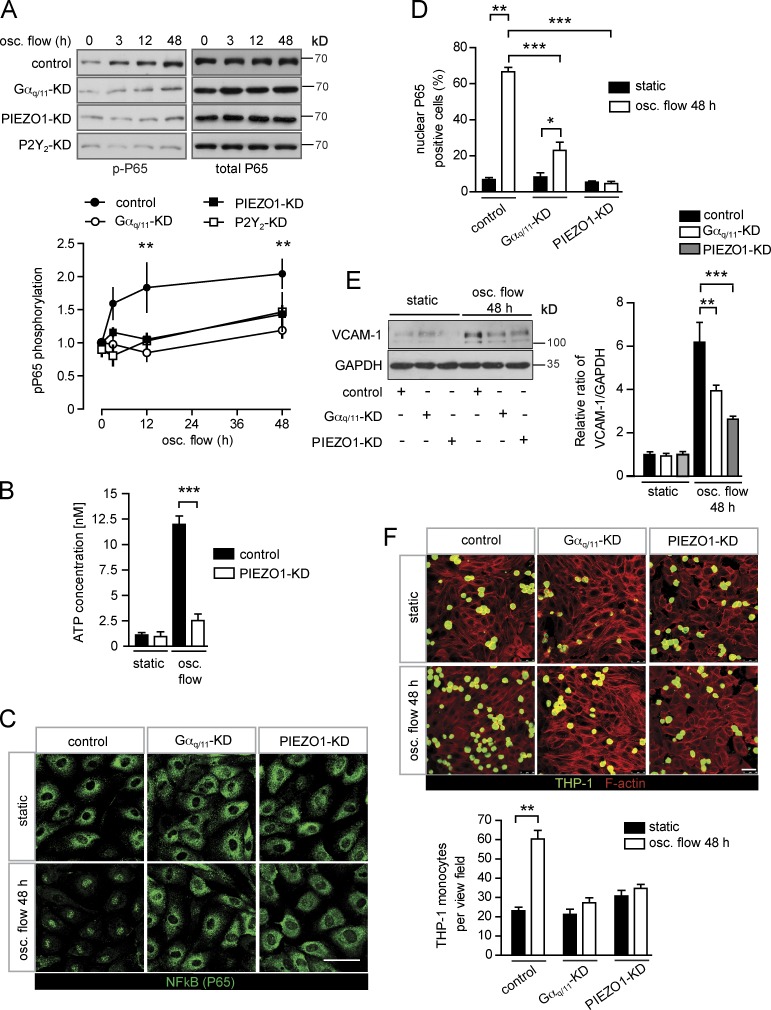

Figure 1.

Endothelial inflammation induced by disturbed flow is mediated by Piezo1 and Gq/G11. (A–F) Confluent HUAECs were transfected with scrambled (control) siRNA, siRNA directed against Piezo1, P2Y2, or Gαq and Gα11. 24 h after second transfection, cells were further grown in the absence of flow (no flow) or were exposed to low and oscillatory (osc.) flow (4 dynes/cm2, 1 Hz) using a flow chamber (A and C–F) or a cone-plate viscometer (B), as described in Materials and methods, for the indicated time periods (A). NF-κB activation was determined by Western blotting for phosphorylated P65 (Ser536). Shown are representative blots. The linear diagram shows the densitometric evaluation of three to five independent experiments normalized to total P65. (B) Concentration of ATP in the supernatant of HUAECs kept under static conditions or under oscillatory flow (data are representative of a least three independent experiments). (C and D) Cellular P65 localization was determined by staining of cells with an anti-P65 antibody. Representative micrographs are shown to quantify nuclear translocation of P65, at least 100 cells were counted per condition for each experiment (data are representative of a least three independent experiments per group). (E) VCAM-1 immunoreactivity was determined by Western blotting (representative blots of four independent experiments). (F) To study monocyte cell adhesion to HUAECs, cells were preexposed to oscillatory flow for 48 h and were incubated with fluorescently labeled THP-1 cells for 30 min at 37°C. (Shown are representative micrographs from three independent experiments). Actin fibers were stained with anti–phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 568 and visualized by confocal microscopy. Bars, 50 µm. Data represent mean values ± SEM; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test [A, D, and E] and two-tailed Student’s t test [B and F]).

Consistent with a role of Piezo1, P2Y2, and Gq/G11 in the activation of endothelial NF-κB in response to disturbed flow, we found that disturbed flow applied for 48 h failed to induce nuclear translocation of p65 in endothelial cells with silenced Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 expression (Fig. 1, C and D). Since activation of NF-κB in endothelial cells has been shown to induce expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules, we tested whether knock-down of Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 affects expression of VCAM-1. When HUAECs were exposed to disturbed flow for 48 h, a strong induction of VCAM-1 immunoreactivity and RNA expression could be observed in control cells (Fig. 1 E and Fig. S1 B). However, this effect was strongly reduced after knock-down of Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 (Fig. 1 E and Fig. S1 B). Similar results were observed for the oscillatory flow-induced up-regulation of other inflammatory genes, such as those encoding CCL2 and PDGFB (Fig. S1, C and D). Consistent with the impaired up-regulation of cell adhesion molecules and chemokines, adhesion of THP-1 monocytes to endothelial cells exposed to disturbed flow for 48 h was strongly reduced after knock-down of Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 (Fig. 1 F). These data show that Piezo1 and Gq/G11 do not only mediate laminar flow-induced anti-atherogenic signaling in endothelial cells, but are also required for induction of inflammatory endothelial activation in response to disturbed flow in vitro.

Endothelial Piezo1 and Gq/G11 deficiency results in reduced endothelial inflammation and progression of atherosclerosis

We next tested whether Piezo1, P2Y2, and Gq/G11 mediate disturbed flow-induced endothelial inflammation also under in vivo conditions using tamoxifen-induced, endothelium-specific Gαq/Gα11-, P2Y2-, or Piezo1-deficient mice (Korhonen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2015, 2016). At the outer curvature of the aortic arch, which is typically exposed to continuous laminar flow, we did not see any obvious differences in the endothelial cell morphology, Vcam-1 expression, or number of Cd68-positive cells in mice with endothelium-specific Piezo1, P2Y2, or Gαq/Gα11 deficiency (Fig. S2, A and B; and Fig. S3, A and C). However, at the inner curvature of the aortic arch, where endothelial cells are naturally exposed to disturbed, atherogenic flow, the increase in endothelial Vcam-1 expression and number of CD68-positive cells were strongly reduced after loss of endothelial Piezo1, P2Y2, or Gαq/Gα11 expression (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S3, B and C). The reduced Vcam-1 in endothelium-specific Gαq/Gα11- and Piezo1-deficient mice was also observed by quantitative PCR analysis (Fig. S4 A), and the reduction in the number of Cd68-positive cells was reflected by a reduced number of Cd11c-positive cells, which have been shown to be present in atheroprone areas of the aorta (Fig. S4 B; Choi et al., 2009).

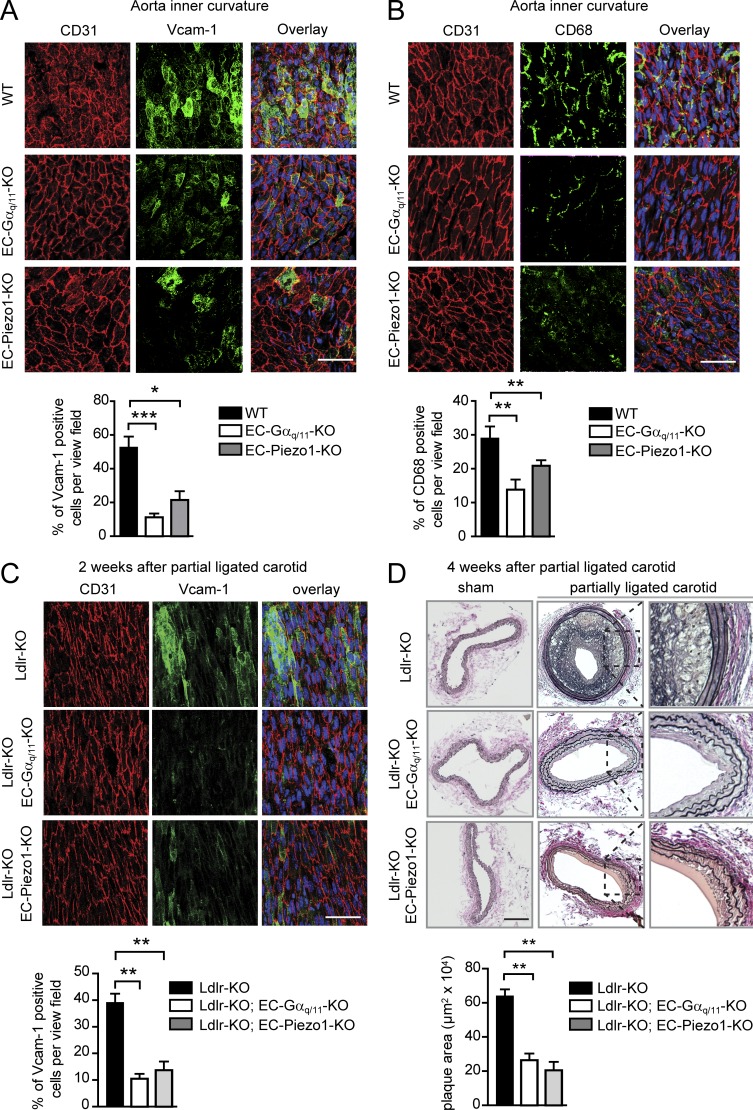

Figure 2.

Endothelial Piezo1 and Gq/G11 deficiency results in decreased endothelial inflammation and reduced progression of atherosclerosis. (A and B) Shown are representative en face immuno-confocal microscopy images of the inner curvature from 12-wk-old wild-type and endothelium-specific Piezo1-KO (EC-Piezo1-KO) and Gαq/Gα11-KO (EC-Gαq/Gα11-KO) mice (n = 6 per genotype per condition). En face aortic arch preparations were triple stained with anti-CD31, anti–Vcam-1 (A) or anti-CD68 antibodies (B) and DAPI. Immunofluorescence staining was quantified as the percentage of Vcam-1–positive cells among CD31-positive cells per view field (A) and as the percentage of CD68-positive cells per view field (B). (C and D) Atherosclerosis-prone Ldlr-KO mice without (Ldlr-KO) or with endothelium-specific Piezo1 (Ldlr-KO; EC-Piezo1-KO) or Gαq/Gα11 deficiency (Ldlr-KO;EC-Gαq/11-KO) were sham operated or underwent partial carotid artery ligation. (C) 14 d after ligation, en face preparations of the left common carotid artery (ligated artery) were stained with DAPI and antibodies against CD31 and Vcam-1. Vcam-1 staining was quantified as percentage of positive cells per view field. (D) 28 d after ligation, carotid arteries were sectioned and stained with elastic stain. Bar graphs show quantification of the intimal plaque area (n = 6 mice per genotype per condition). Bars: 50 µm (A–C) and 100 µm (D). Data represent mean ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test).

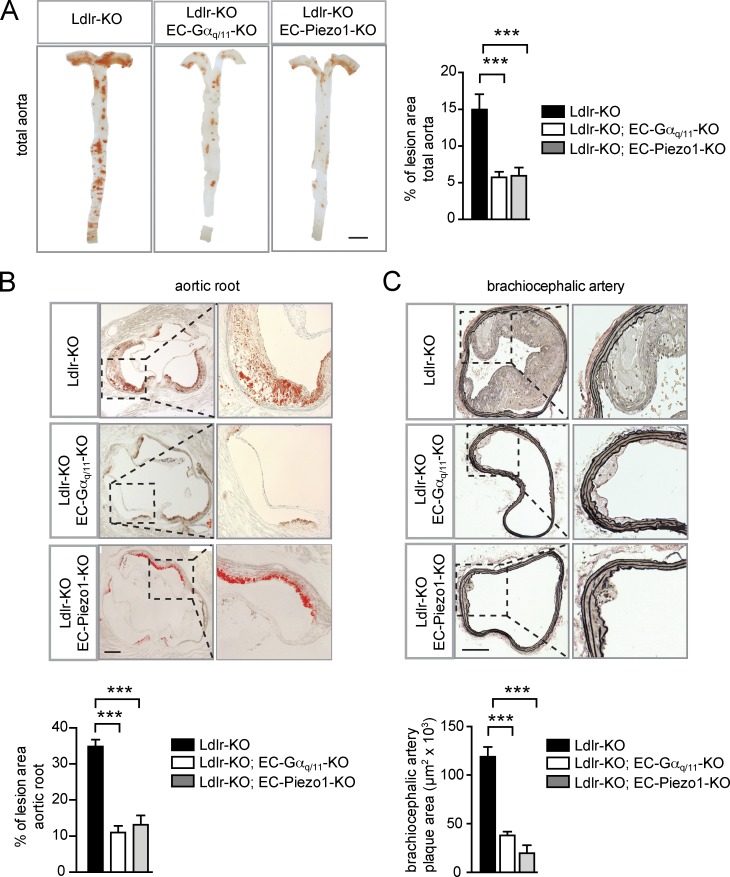

To study the function of endothelial Piezo1, P2Y2, and Gq/G11 in atherogenesis, we performed partial carotid artery ligation, a model for acutely induced disturbed flow leading together with reduced laminar flow to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis (Nam et al., 2010). Induction of endothelium-specific Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 deficiency in mice lacking the LDL-receptor and fed a high-fat diet resulted in a strong reduction of endothelial inflammation indicated by reduced Vcam-1 expression 2 wk after ligation (Fig. 2 C and Fig. S4 C). 4 wk after partial carotid artery ligation, a significant reduction in neointima size was found in LDL-receptor–deficient mice with endothelium-specific Piezo1, P2Y2, or Gαq/Gα11 deficiency (Fig. 2 D and Fig. S3 D). Similar observations were made in a long-term model of atherosclerosis. After 16 wk of feeding mice a high-fat diet, development and progression of atherosclerotic plaques was significantly reduced in the aorta, the aortic root, as well as in the innominate artery of endothelium-specific Piezo1- or Gαq/Gα11-deficient mice lacking the LDL- receptor compared with control LDL-receptor–deficient mice (Fig. 3, A–C; and Fig. S4, C and D).

Figure 3.

Deficiency of endothelial Piezo1 and Gq/G11 reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation. (A–C) Representative atherosclerotic lesions in Ldlr-KO mice without or with induced endothelium-specific Piezo1 deficiency (Tie2-CreER(T2);Piezo1flox/flox (Ldlr-KO;EC-Piezo1-KO)) or endothelium-specific Gαq/Gα11 deficiency (Cdh5-Cre;Gnaqflox/flox;Gna11−/− (Ldlr-KO;EC-Gαq/11-KO)) were fed a high-fat diet for 16 wk (n = 6–10 per genotype). (A) Representative images are shown of whole aortae that were prepared en face and stained with oil-red-O. En face atherosclerotic lesions are shown as percentage of total aorta area. (B) Representative oil-red-O–stained atherosclerotic lesions images in the aortic valve region (n = 6–10 per genotype). Dotted boxes are shown in higher magnifications in right panel. Plaque area was quantified as percentage of total aortic root area per genotype. (C) Representative images of atherosclerotic plaques observed in brachiocephalic arteries (innominate arteries). 5-µm paraffin cross sections were stained with elastic stain for assessment of morphological features. (n = 6–10 animals per genotype). Dotted boxes are shown in higher magnifications in right panel. Shown is the quantification of total plaque area in the brachiocephalic arteries. Data represent mean ± SEM; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test). Bars: 5 mm (A); 250 µm (B); 100 µm (C).

Endothelial Piezo1 and Gq/G11 mediate atheroprotective or atheroprone signaling depending on the flow pattern

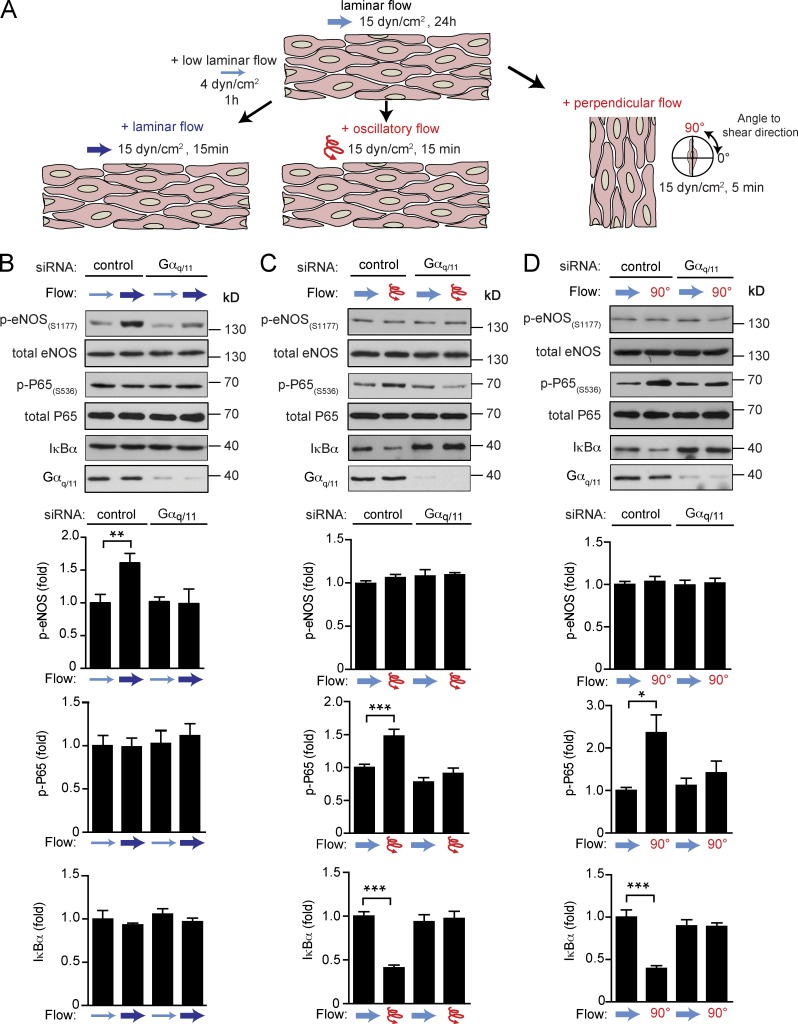

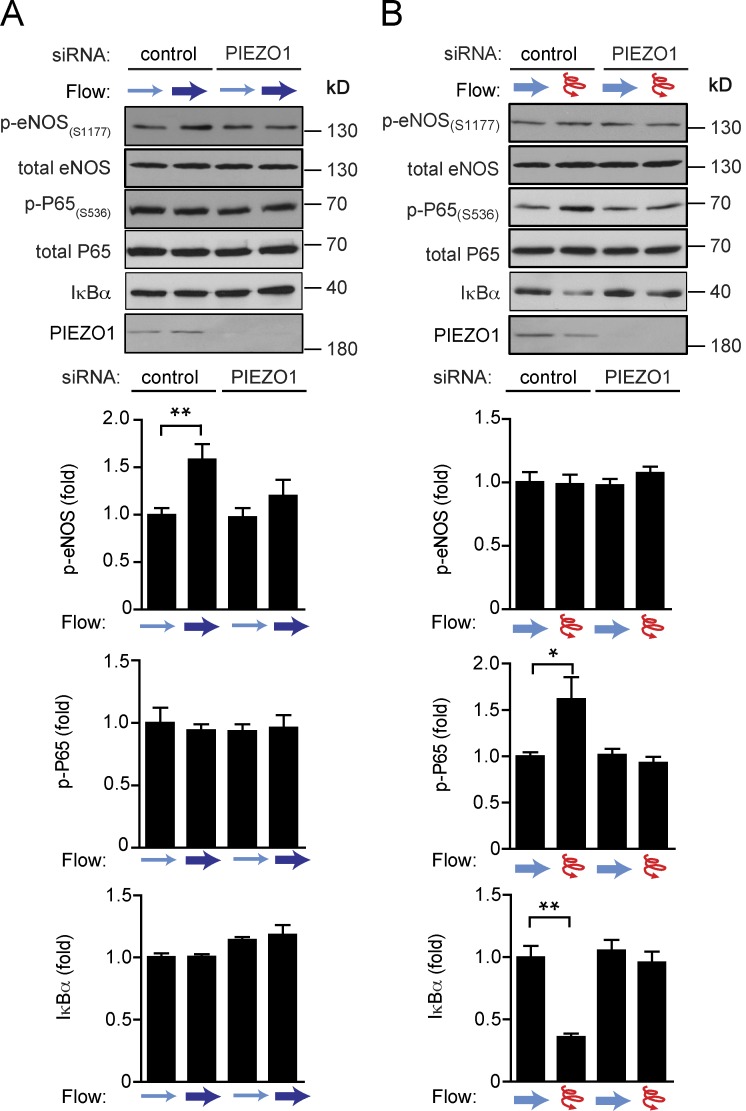

These data indicate that endothelial Piezo1 and Gq/G11 mediate inflammatory endothelial signaling in response to disturbed flow resulting in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, the same upstream mechanosignaling pathway also senses laminar flow and promotes eNOS activation in vitro and in vivo (Wang et al., 2015, 2016). Thus, Piezo1- and Gq/G11-mediated signaling appear to be activated both by laminar and disturbed flow and mediate atheroprotective, as well as pro-atherogenic, signaling. We then wanted to understand how endothelial cells read out Piezo1- and Gq/G11-mediated mechanosignaling depending on the flow pattern either as activation of anti-atherogenic signaling leading to eNOS activation or as an atherogenic stimulus resulting in inflammatory signaling and activation of NF-κB. To be able to clearly distinguish between endothelial responses to laminar and disturbed flow, we first preflowed endothelial cells by exposing them for 24 h to laminar flow, which resulted in alignment of cells in the direction of flow. Thereafter, we reexposed cells to high laminar flow parallel to the cell axis or to disturbed flow. Disturbed flow was induced by high-frequency oscillatory flow or by changing the flow direction by 90 degrees (Fig. 4 A). When preflowed control cells were reexposed to high laminar flow, we observed increased eNOS phosphorylation, whereas no activation of NF-κB indicated by phosphorylation of p65 at serine 536, and degradation of Iκ-Bα was seen (Fig. 4 B). In contrast, in preflowed cells both oscillatory flow and flow perpendicular to the morphological cell axis resulted in strong activation of NF-κB, whereas eNOS phosphorylation was unaffected (Fig. 4, C and D). Knock-down of Gαq/Gα11 blocked not only laminar flow-induced eNOS phosphorylation (Fig. 4 B), but also disturbed flow-induced inflammatory signaling (Fig. 4, C and D), and the same was observed after knock-down of Piezo1 (Fig. 5, A and B). This shows that in preflowed endothelial cells different downstream signaling processes are induced via Piezo1 and Gq/G11, depending on the applied flow pattern.

Figure 4.

Endothelial Gq/G11 mediates atheroprotective or atheroprone signaling upon stimulation by different flow patterns. (A) Diagram of work flow. Endothelial cells were first exposed to laminar flow for 24 h. Thereafter, cells were reexposed to high laminar flow to induce atheroprotective signaling. Alternatively, cells were exposed to either disturbed flow (high frequency oscillatory flow) or flow direction was changed by 90 degrees to induce atherogenic signaling. (B–D) HUAECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (control) or siRNA directed against Gαq and Gα11 (Gαq/11). Thereafter, cells were preflowed for 24 h (15 dynes/cm2) and then subjected to low flow for 1 h (4 dynes/cm2) and/or high flow for 15 min (15 dynes/cm2; B) or to oscillatory flow (15 dynes/cm2, 1 Hz for 15 min; C) or to perpendicular flow (90 degrees) for 5 min (D). Thereafter, cells were lysed and phosphorylated eNOS (Ser1177), phosphorylated P65 (Ser536), and total IκBα, eNOS, P65, and Gαq/Gα11 levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. Shown are representative blots from three to five independent experiments. Bar diagrams show the densitometric evaluation of corresponding immunoblots. Data represent mean ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01 ***, P ≤ 0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

Figure 5.

Endothelial Piezo1 mediates atheroprotective or atheroprone signaling depending on the flow pattern. (A and B) HUAECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (control) or siRNAs directed against Piezo1 (PIEZO1). Thereafter, cells were preflowed for 24 h (15 dynes/cm2) and then reexposed to laminar flow as in Fig. 4 B (A) or to oscillatory flow as in Fig. 4 C (B). Cells were then lysed and phosphorylated eNOS (Ser1177), phosphorylated P65 (Ser536), and total levels of IκBα, eNOS, P65, and Piezo1 were analyzed by immunoblotting. Shown are representative blots from three to five independent experiments. Bar diagrams show the densitometric evaluation of corresponding immunoblots. Data represent mean ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

Integrins are differentially activated by different flow patterns via Piezo1 and Gq/G11

Since flow-induced endothelial NF-κB activation has been shown to be mediated by integrin α5β1 or αvβ3 and to require focal adhesion kinase (FAK) downstream of integrins (Bhullar et al., 1998; Petzold et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016; Yun et al., 2016), we tested the effect of laminar and disturbed flow on FAK phosphorylation in preflowed endothelial cells. As shown in Fig. 6 (A–E), only disturbed flow was able to induce FAK activation, whereas laminar flow had no effect or rather reduced FAK activity. The FAK activation by disturbed flow was absent in cells after knock-down of Gαq and Gα11 (Fig. 6, B and C) and Piezo1 (Fig. 6 E). Immunohistochemical analysis of the aortic arch of LDL-receptor–deficient mice showed strongly increased phosphorylation of FAK in endothelial cells of the inner curvature compared with the outer curvature (Fig. 6, F and G). Interestingly, in LDL-receptor–deficient mice lacking Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 in an endothelium-specific manner, this increased endothelial phosphorylation of FAK at the inner aortic curvature was abrogated (Fig. 6, F and G).

Figure 6.

FAK is differentially activated by different flow patterns via Piezo1 and Gq/G11. (A–E) HUAECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (control) or siRNA directed against Gαq and Gα11 (Gαq/11; A–C) or against Piezo1 (D and E) and exposed to laminar or disturbed flow as described in Fig. 4 A. Activation of integrin signaling was determined by immunoblotting for phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (pFAK, Y397). Bar diagrams show densitometric evaluation of immunoblots (quantification of three to five independent experiments). (F and G) Ldlr-KO mice without or with endothelium-specific Gαq/Gα11 deficiency (Ldlr-KO;EC-Gαq/11-KO; F) or endothelium-specific Piezo1 deficiency (Ldlr-KO;EC-Piezo1-KO) were fed a high-fat diet for 4 wk (n = 4–6 mice per genotype). Cross sections of the inner and outer curvatures of aortic arches were stained with antibodies against phosphorylated FAK (Y397, green) and against the endothelial marker CD31 (red) and with DAPI (blue). Data are representative of six to eight microscope field areas per animal. Bar diagrams show percentage of area stained by anti-pFAK antibody of total endothelial cell area defined by staining by anti-CD31 antibody (based on analysis of at least five sections each from at least four different animals). Bars, 50 µm. Data represent mean ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

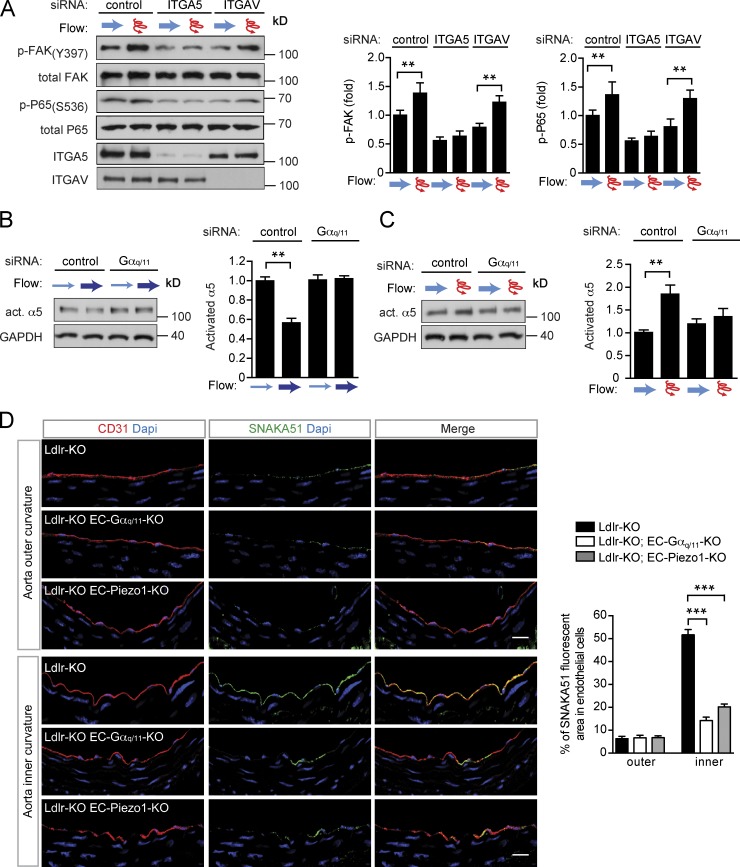

To discriminate between an involvement of integrin α5 and integrin αv, we knocked down expression of either integrin α-subunit. As shown in Fig. 7 A, only knock-down of integrin α5 inhibited disturbed flow-induced FAK and NF-κB activation, whereas knock-down of integrin αv was without effect. Similarly, blockade of α5β1 integrin with ATN-161, but not of αvβ3 integrin with S247, inhibited flow-induced phosphorylation of FAK and P65 (Fig. S5 A). To study flow pattern–dependent integrin activation more directly, we used antibodies recognizing the activated form of integrin α5 (Sun et al., 2016). We found that integrin α5 became activated upon disturbed flow, but not in response to laminar flow (Fig. 7, B and C), and knock-down of Gαq/Gα11 blocked integrin activation in response to disturbed flow (Fig. 7 C). Staining of sections from the aortic arch of LDL-receptor–deficient mice with antibody SNAKA51 directed against active integrin α5 (Clark et al., 2005), which also recognizes activated murine integrin α5 (Fig. S5, B–E), showed increased integrin activation in endothelial cells of the inner curvature compared with those of the outer curvature (Fig. 7 D). In LDL-receptor–deficient mice with induced endothelium-specific Piezo1- or Gαq/Gα11-deficiency, the increased endothelial integrin activation at the inner aortic curvature was strongly reduced (Fig. 7 D). These data indicate that in preflowed endothelial cells, only disturbed flow induces integrin activation and that also under in vivo conditions endothelial cells in areas of disturbed flow show Piezo1- and Gq/G11-dependent increases in integrin activation and FAK phosphorylation.

Figure 7.

Integrins are differentially activated by different flow patterns via Piezo1 and Gq/G11. (A–C) HUAECs were transfected with scrambled siRNA (control) or siRNA directed against ITGA5 and ITGAV (A) or against Gαq and Gα11 (Gαq/11; B and C) and were exposed to laminar or disturbed flow as described in Fig. 4 A. Activation of integrin signaling was determined by immunoblotting for phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (pFAK, Y397; A) or by immunoprecipitation of activated α5 integrin (B and C). P65 activation was determined by anti–phospho-P65 (S536) antibodies (A). Bar diagrams show densitometric evaluation of immunoblots (quantification of three to five independent experiments). (D) Ldlr-KO mice without or with endothelium-specific Gαq/Gα11 deficiency (Ldlr-KO;EC-Gαq/11-KO) endothelium-specific Piezo1-deficiency (Ldlr-KO;EC-Piezo1-KO) were fed a high-fat diet for 4 wk (n = 4–6 mice per genotype). Cross sections of the inner and outer curvatures of aortic arches were immunostained with antibodies against activated α5 integrin (SNAKA51; green), against the endothelial marker CD31 (red) or with DAPI (blue). Bar diagrams show percentage of area stained by anti-activated α5 integrin antibody of total endothelial cell area defined by staining by anti-CD31 antibody (based on analysis of at least five sections each from at least four different animals). Bars, 25 µm. Data represent mean ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

Discussion

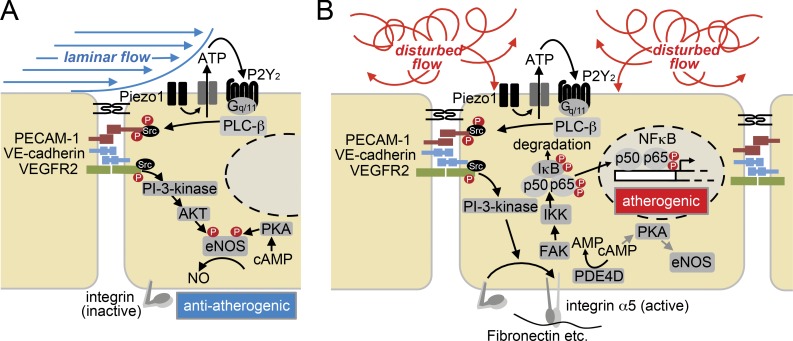

Laminar flow and disturbed flow profoundly differ in their effects on endothelial cell morphology and function. While continuous high laminar flow induces endothelial cell elongation and alignment in the direction of flow, failure of endothelial cells to elongate and to align under disturbed flow is a hallmark of atheroprone vessel areas (Davies, 2009). It has been suggested that exposure of endothelial cells to unidirectional flow results in adaptation by altering the mechanotransduction of endothelial cells (Davies et al., 1997; Hahn and Schwartz, 2008). This is consistent with the observation that endothelial cells grown in vitro initially respond to laminar flow with both atherogenic, inflammatory, and atheroprotective, anti-inflammatory signaling. However, once cells have been exposed to laminar flow for a while, they align and show down-regulation of atherogenic, inflammatory signaling, whereas inflammatory signaling remains activated under disturbed flow (Mohan et al., 1997; Hahn and Schwartz, 2009). While the effect of fluid shear stress on endothelial cell function and signaling has been extensively studied, the majority of studies have been performed with endothelial cells, which have not been exposed to flow before the experiment. However, under in vivo conditions, endothelial cells are constantly under the influence of flow, and recent evidence indicates that the flow angle is a very critical determinant of the cellular responses to flow (Wang et al., 2013). Flow in the direction of the cell axis in prealigned cells stimulates activation of eNOS, whereas off-axis flow results in the activation of inflammatory signaling, including NF-κB activation (Wang et al., 2013). By combining in vivo experiments and in vitro studies on preflowed endothelial cell cultures, we show that atheroprotective and atherogenic signaling induced by laminar and disturbed flow, respectively, both involve Piezo1-, P2Y2-, and Gq/G11-mediated signaling. When this signaling cascade is activated by laminar flow, which does not induce integrin activation, it promotes atheroprotective downstream signaling such as eNOS activation. However, when activated by disturbed flow, which also induces integrin activation, pro-inflammatory signaling processes including NF-κB activation are induced (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Model of the role of Piezo1 and Gq/G11 proteins in endothelial response to different flow patterns. (A and B) Laminar flow (A) and disturbed flow (B) activate the same initial signaling processes involving the mechanosensitive cation channel Piezo1 and the purinergic receptor P2Y2, as well as Gq/G11-mediated signaling and activation of the mechanosignaling complex consisting of PECAM-1, VE-cadherin, and VEGFR2. In cells exposed to laminar flow, integrins are not activated and this initial signal transduction pathway promotes atheroprotective signaling including activation of eNOS through PI-3-kinase and AKT. Through incompletely understood pathways, eNOS is also activated by cAMP acting through protein kinase A (PKA). In cells exposed to disturbed flow, activation of the initial signaling pathway results in integrin activation, which promotes via focal adhesion kinase (FAK) NF-κB activation and atherogenic signaling, as well as reduced eNOS activation by promoting cAMP degradation via activation of phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D).

Consistent with a role of Piezo1-, P2Y2-, and Gq/G11-mediated mechanotransduction in inflammatory signaling via NF-κB in atheroprone vascular areas, we found that endothelium-specific loss of Piezo1, P2Y2, and Gαq/Gα11 strongly reduced progression of atherosclerosis, and similar results were independently reported for endothelium-specific P2Y2-deficient mice (Chen et al., 2017). On the other hand, we previously showed that loss of endothelial Piezo1, P2Y2, and Gαq/Gα11 reduces flow-induced eNOS activation resulting in an increase in arterial blood pressure (Wang et al., 2015, 2016). Similar phenotypes have been observed in mice lacking PECAM-1, another component of the flow-induced signaling cascade. PECAM-1–deficient animals show reduced progression of atherosclerosis (Harry et al., 2008), while PECAM-1 has also been shown to mediate flow-induced eNOS activation (Fleming et al., 2005), and mice lacking PECAM-1 show reduced flow-induced nitric oxide (NO) formation and vasodilation (Bagi et al., 2005). While a concurrent involvement of Piezo1- and Gq/G11-mediated mechanotransduction in flow-induced eNOS activation, as well as in promotion of atherosclerosis may appear counterintuitive, it is fully consistent with a role of this mechanosignaling pathway as an upstream mediator of endothelial cell responses to flow in general, irrespective of the flow pattern.

How different flow patterns direct Piezo1- and Gq/G11-mediated signaling in the anti- and pro-inflammatory direction is not clear. However, we show that only disturbed flow induces integrin activation, which has been shown to mediate flow-induced NF-κB activation through FAK (Bhullar et al., 1998; Tzima et al., 2002; Orr et al., 2005, 2006). This is consistent with earlier data showing that flow induces inflammatory signaling by PECAM-1/VE-cadherin/VEGFR2- and PI-3-kinase–dependent inside-out activation of integrins, resulting in FAK-dependent NF-κB activation (Tzima et al., 2005). In contrast, under laminar flow, when integrins are not activated, the upstream signaling via Gq/G11 preferentially activates AKT, resulting in eNOS phosphorylation and activation (Wang et al., 2015). Activation of integrins in addition results in inhibition of cAMP signaling through activation of PDE4D (Yun et al., 2016), which would reduce eNOS activation through cAMP-dependent kinase (PKA; Boo et al., 2002; Dixit et al., 2005). However, other, so far unknown mechanisms might contribute to loss of eNOS activation in response to disturbed flow. Under in vivo conditions, activation of integrin α5β1 by disturbed flow is expected to be further promoted by the deposition of RGD-containing extracellular matrix proteins, such as fibronectin, within the endothelial cell matrix in atheroprone areas exposed to disturbed flow (Orr et al., 2005; Feaver et al., 2010).

Our observation that disturbed flow induces inflammatory signaling in prealigned endothelial cells through integrin α5 is consistent with recent reports providing evidence for a central role of integrin α5 in mediating flow-induced endothelial inflammatory signaling in vitro and in vivo (Sun et al., 2016; Yun et al., 2016; Budatha et al., 2018). However, earlier evidence suggested that also integrin αvβ3 is involved in flow-induced pro-inflammatory endothelial signaling (Bhullar et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2015). The exact mechanisms underlying the selective activation of integrins by disturbed flow, but not by laminar flow are unclear; however, similar observations have recently been made (Sun et al., 2016) and could be correlated with the ability of oscillatory shear stress to promote translocation of integrin α5 into lipid rafts, whereas pulsatile laminar shear stress caused integrin α5 to reside largely outside lipid rafts (Sun et al., 2016). How oscillatory flow, but not laminar flow, induces translocation of integrin α5 into lipid rafts is, however, unclear.

The ability of cells to sense not only the magnitude of a physical stimulus, but also its direction, has been observed in different contexts and appears to involve integrins (Swaminathan et al., 2017a). Even though the molecular mechanism underlying the ability to sense the direction of mechanical cues remains rather obscure, recent data show that the interaction of vinculin and actin downstream of integrins occurs by forming a force-dependent catch bond that strongly depends on the direction of the applied force, and computational modeling suggests that the vinculin-actin catch bond might represent a mechanism for cellular responses to directional forces (Huang et al., 2017). Alternatively, integrins might sense force direction by molecular ordering. Recent studies indicate that integrins can be aligned and oriented by forces (Nordenfelt et al., 2017; Swaminathan et al., 2017b). Such directional orientation of integrins and associated molecules, including talin (Liu et al., 2015), might be a basis for direction-dependent mechanosensing. This would also be supported by earlier data showing that exposure of endothelial cells to uni-directional flow results in a remodeling of focal adhesions in the direction of flow (Davies et al., 1994, 1997). It remains to be tested whether endothelial integrins and downstream protein complexes align and orient themselves under the influence of directional flow. It is conceivable that such molecular orientation could affect integrin downstream signaling in response to particular flow patterns in a way that, e.g., laminar flow results in an adaptation, which suppresses integrin signaling in response to continuous flow in one direction, but still allows for integrin signaling in response to flow coming from different angles.

Our data indicate that Piezo1 and Gq/G11 play a central role in sensing disturbed flow to induce pro-inflammatory signaling. This leads to the question how Piezo1 is activated by disturbed flow, which induces endothelial fluid shear stress of different degrees and in different directions. Endothelial fluid shear stress has been proposed to result in lateral membrane tension independent of the flow direction (Fung and Liu, 1993; White and Frangos, 2007). Since Piezo1 has been described to be in particular sensitive to membrane bilayer tension (Lewis and Grandl, 2015; Cox et al., 2016), this is consistent with a role of Piezo1 in direct endothelial flow sensing independently of the flow direction.

Collectively, our data indicate that Piezo1 and Gq/G11-mediated downstream signaling processes are involved in endothelial mechanosignaling by primarily sensing flow intensity independently of the flow direction. In cells exposed to disturbed flow coming from different directions, cells do not align, and integrins are activated in a Gq/G11-dependent manner, resulting in FAK-mediated NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory effects. In contrast, if cells are exposed to sustained laminar flow, integrins appear to be resistant to Gq/G11-mediated activation, and Piezo1- and Gq/G11-dependent signaling primarily promotes atheroprotective signaling, including activation of eNOS. This explains why constant high laminar shear stress induces activation of eNOS and production of NO in athero-resistant areas, whereas failure of parallel endothelial cell alignment due to disturbed flow promotes inflammatory signaling through, e.g., NF-κB in atheroprone areas (Baeyens et al., 2014; Baeyens and Schwartz, 2016). We also uncovered a key role of Piezo1/Gq/G11-mediated mechanotransduction in the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Despite the elevation of systemic blood pressure, which we previously observed, the net effect of an endothelium-specific inactivation of Piezo1 or Gαq/Gα11 is clearly a strong reduction of atherosclerotic lesions, underscoring the direct atherogenic function of Piezo1/Gq/G11-mediated mechanotransduction. However, inhibition of the flow-sensor pathway involving Piezo1 and Gq/G11 is not a good therapeutic strategy to reduce atherosclerosis progression since it may lead to increased vascular tone and blood pressure. Signaling via integrins or downstream of integrins appear to be a more promising approach to promote atheroprotection without altering vascular tone.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HUAECs were purchased from Provitro AG and cultured in endothelial growth medium (EGM-2; Lonza), supplemented with 5% FBS; 2MV BulletKit; Lonza). Only confluent cells at passage ≤4 were used in experiments. THP-1 monocyte cells were obtained from Sigma (88081201), cultured in RPMI 1641 medium (Invitrogen), and supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and 10% FBS.

siRNA-mediated knock-down

HUAECs at 70% confluence were transfected with control siRNA (AllStars Negative siRNA, Qiagen, 1027280) and siRNAs against Piezo1, Gαq, Gα11, P2Y2, ITGA5, and ITGAV (all from Qiagen) by using Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher) and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) for 6 h on two consecutive days as described (Wang et al., 2015). The targeted sequences of human siRNAs directed against RNAs encoding Piezo1, Gαq, Gα11, P2Y2, ITGA5, and ITGAV were Piezo1: 5′-CCAAGTACTGGATCTATGT-3′, 5′-GCAAGTTCGTGCGCGGATT-3′, and 5′-AGAAGAAGATCGTCAAGTA-3′; GNAQ: 5′-CAGGACACATCGTTCGATTTA-3′ and 5′-CAGGAATGCTATGATAGACGA-3′; GNA11: 5′-AGCGACAAGATCATCTACTCA-3′ and 5′-AACGTGACATCCATCATGTTT-3′; P2RY2: 5′-CCCTTCAGCACGGTGCTCT-3′, 5′-CTGCCTAGGGCCAAGCGCA-3′, and 5′-GCTCGTACGCTTTGCCCGA-3′; ITGA5: 5′-AATCCTTAATGGCTCAGACAT-3′ and 5′-CAGGGTCTACGTCTACCTGCA-3′; and ITGAV: 5′-GAGTGCAATCTTGTACGTAAA-3′ and 5′-CAGGCAATAGAGATTATGCCA-3′.

Shear-stress experiments

HUAECs were seeded in µ-slide I0.4 Luer ibiTreat chambers (Ibidi, 80176) and unidirectional laminar or oscillatory flow was applied on confluent monolayers using the Ibidi pump system (Ibidi, 10902). Unidirectional constant laminar flow was used to mimic blood flow profile in atheroprotected areas of the vasculature. Oscillatory flow or perpendicular flow (90 degrees with respect to cell axis orientation) was used to mimic disturbed blood flow in atheroprone areas of the vasculature. After cells were adapted to laminar flow (15 dynes/cm2) for 24 h, cells were subjected to (1) low laminar flow 4 dynes/cm2 for 1 h and then 15 dynes/cm2 for 15 min (unidirectional flow protocol) or (2) oscillatory flow 15 dynes/cm2 for 15 min 1 Hz (oscillatory flow protocol). For long term disturbed flow experiments, HUAECs were exposed to 0, 3, 12, and 48 h of oscillatory low flow (4 dynes/cm2 with a frequency of 1 Hz). To modify the cell axis orientation during flow stimulation we used a custom-made parallel-flow chamber as previously described (Wang et al., 2012). In brief, cells were seeded onto round glass slides (Schott; diameter, 40 mm), which had been coated with 50 µg/ml fibronectin for 1 h. Then, slides with a confluent monolayer of HUAECs were mounted onto the bottom of the chamber (dimensions, 104 × 50 mm). Laminar flow of 15 dynes/cm2 for 24 h was imposed on the cells by perfusing culture medium through the channel between the endothelial cell–containing glass slide and an acrylic plate in the flow chamber. Cells were then exposed to a change in the flow direction of 90 degrees for 5 min. During the experiments, flow units were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in a tissue culture incubator. After the experiment, cells were immediately lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors and placed at −80°C for subsequent Western blotting analysis.

For experiments to determine ATP levels, the BioTech-Flow System cone-plate viscosimeter (MOS Technologies) was used to expose cells to fluid shear stress. The cone of this system has an angle of 2.5 degrees and rotates on top of a 33-cm2 cell culture dish containing 3 ml of medium. Shear stress was calculated with the following formula (assuming a Reynolds number of <1): τ = η × 2π × n/0.044 (τ: shear stress; η: viscosity; n: rotational speed; Buschmann et al., 2005).

Determination of ATP concentration

ATP concentration was determined as described (Wang et al., 2016). In brief, HUAECs were seeded in a flow chamber of the BioTech-Flow system (MOS Technologies). 24 h after the second siRNA transfection, cells were starved in serum-free medium for 4 h and were then kept under static conditions or were exposed to oscillatory flow at 4 dynes/cm2 (at a rotation speed of 28 rpm, 40 amplitude, and 1 Hz) for 5 min. ATP concentration in the supernatant was determined using a bioluminescence assay (Molecular Probes, A22066) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each siRNA condition, three biological replicates were performed and evaluated. To inhibit ectonucleotidases, 30 µM of ARL67156 (Tocris) was added to the extracellular solution 20 min before the experiment. Luminescence intensity was measured with a Flexstation-3 (Molecular Devices), and ATP amounts were calculated using a calibration curve with ATP standards.

Western blot analysis, immunoprecipitation

Total protein was extracted from HUAECs using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (10 mg/ml of leupeptin, pepstatin A, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzensulfonylfluorid and aprotinin), and phosphatase inhibitors (PhosSTOP, Roche). Total cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking (5% BSA at room temperature for 1 h), the membranes were incubated with gentle agitation overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti–phospho-eNOS (Ser1177, 9571), anti–phospho-P65 (Ser536 [93H1], 3033), anti–phospho-FAK (Tyr397, 3283), anti–integrin α V (4711), anti-FAK (D2R2E, 13009), anti–NF-κB P65 (C22B4, 4764), anti-GAPDH (14C10, 2118), and anti-IκBα (44D4, 4812), all from Cell Signaling. Total anti-eNOS antibody was from BD Biosciences (610296). Anti-Gαq/Gα11 (sc-392) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-Piezo1 (15939-1-AP) was from Proteintech. Anti-integrin α5 (EPR7854, ab150361) and anti–VCAM-1 (EPR5047, ab134047) were from Abcam. The membranes were then washed three times for 5 min each with TBST and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling, dilution 1:3,000) followed by chemiluminescence detection using ECL substrate (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Band intensities from immunoblotting were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (Abramoff et al., 2004).

For immunoprecipitation, protein lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4°C for 10 min, and supernatants were incubated with antibodies recognizing activated integrin α5 (GeneTex, GTX86905) overnight at 4°C with rocking. Supernatants were subsequently incubated with protein A/G PLUS-agarose (Santa Cru; 1 µg of antibody per 100 µg protein and 20 µl beads in 50 µl lysis buffer) for 4 h at 4°C. Then, the beads were collected by centrifugation (10,000 g at 4°C for 1 min) and washed three times with RIPA lysis buffer with protease inhibitors. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotting was performed with anti-integrin α5 antibodies.

Monocyte adhesion assay

HUAECs transfected with siRNAs were grown in the absence of flow (static) or were exposed to oscillatory flow (4 dynes/cm2, with changes in flow direction every 2 s for 48 h) in µ-slides I0.4 Luer (Ibidi). Monocytic THP-1 cells (Sigma) were labeled with 0.5 µM Calcein AM (Thermo Fisher) for 30 min at 37°C, washed with PBS, and resuspended at a concentration of 106 cells in endothelial cell medium. Labeled THP-1 cells were then perfused over the HUAECs with a flow rate of 1 ml/min and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Non-adherent cells were removed by perfusing cells with endothelial cell medium for 3 min with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Cells were fixed in flow chambers for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), washed three times with PBS, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 phalloidin (1 U/ml; Thermo Fisher, A12380) to visualize actin fibers. Endothelial cells and adherent THP-1 cells were then analyzed by confocal microscopy. Two to four objective fields were randomly selected to count adherent THP-1 cells in each slide, and three independent experiments were performed.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

HUAECs transfected with siRNAs were exposed to 0, 3, 24, and 48 h of oscillatory low flow (4 dynes/cm2, 1 Hz) in µ-slides I0.4 Luer (Ibidi). Total RNA was isolated from endothelial cell monolayers using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA synthesis was performed using the ProtoScript II Reverse Transcription kit (New England BioLabs, M0368S). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using primers designed with the online tool provided by Roche and the Light-Cycler 480 Probe Master System (Roche). Each reaction was run in triplicates, and relative gene expression levels were normalized to human β-actin (ACTB). Relative expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences used were GNAQ: forward 5′-GACTACTTCCCAGAATATGATGGAC-3′, reverse 5′-GGTTCAGGTCCACGAACATC-3′; GNA11: forward 5′-GATCCTCTACAAGTACGAGCAGAAC-3′, reverse 5′- ACTGATGCTCGAAGGTGGTC-3′; ACTB: forward 5′-GCTACGAGCTGCCTGACG-3′, reverse 5′-GGCTGGAAGAGTGCCTCA-3′; Piezo1: forward 5′-TCGCTGGTCTACCTGCTCTT-3′, reverse 5′-GGCCTGTGTGACCTTGGA-3′; VCAM-1: forward 5′-GAAGTTTAACACTTGATGTTCAAGGA-3′, reverse 5′-AGGATGCAAAATAGAGCACGA-3′; CCL2 (MCP-1): forward 5′-AGTCTCTGCCGCCCTTCT-3′, reverse 5′-GTGACTGGGGCATTGATTG-3′; PDGFb: forward 5′-TGATCTCCAACGCCTGCT-3′, reverse 5′-CCTTCCATCGGATCTCGTAA-3′; and P2YR2: forward 5′-TAACCTGCCACGACACCTC-3, reverse 5′-CTGAGCTGTAGGCCACGAA-3.

Genetic mouse models

All mice were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background for a minimum of eight generations. Experiments were performed with littermates as controls. Male and female animals at an age of 8–12 wk were used if not stated otherwise. Mice were housed under a 12-h light–dark cycle with free access to food and water and under specific pathogen–free conditions. The generation of inducible endothelium-specific Gαq/Gα11-deficient mice (Tie2-CreERT2;Gnaqf/f;Gna11−/− [EC-q/11-KO]), inducible endothelium-specific P2Y2-deficient mice (Tie2-CreERT2;P2ry2f/f [EC-P2Y2-KO]), and inducible endothelium-specific Piezo1-deficient mice (Tie2-CreERT2;Piezo1f/f [EC-Piezo1-KO]) was described previously (Korhonen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2015, 2016). For atherosclerosis studies, Gαq/Gα11-deficient mice were bred also on the constitutive Cadherin-5-Cre (Alva et al., 2006) together with the low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout (Ldlr-KO; Ishibashi et al., 1993) background. All animal experiments were performed according to the animal ethics committees of the Regierungspräsidia Karlsruhe and Darmstadt.

For atherosclerosis analysis, Cre recombinase was activated in male Ldlr-KO mice at 6–8 wk of age by intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648; 1 mg per animal/day on five consecutive days). 5 d after the last tamoxifen injection, mice were fed a high-fat diet for 16 wk to induce development of atherosclerotic lesions. Diet contained 21% butterfat and 1.5% cholesterol (Ssniff, TD88137). Thereafter, animals were sacrificed, and atherosclerotic lesions were analyzed as described below.

Partial carotid ligation

Partial carotid ligation was performed as described before (Nam et al., 2009). In brief, mice at 12 wk of age were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (120 mg/kg, Pfizer) and xylazine (16 mg/kg, Bayer) and placed on a heated surgical pad. After hair removal, a midline cervical incision was made, and the left internal and external carotid arteries were exposed and partially ligated with 6.0 silk sutures (Serag-Wiessner), leaving the superior thyroid artery intact. Skin was sutured with absorbable 6.0 silk suture (CatGut) and animals were monitored until recovery in a chamber on a heating pad after the surgery. Animals were fed a high-fat diet for 2 or 4 wk (Ssniff, TD88137), at which time their carotid arteries were harvested. To determine atherosclerotic lesions, left (partially ligated) and right (sham) carotid arteries were removed and fixed in 4% PFA overnight. Fixed vessels were embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (5 µm) were made through the entire carotid arteries and stained with accustain elastic stain (Sigma) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Plaque area was calculated by subtracting the lumen area from the area circumscribed by the internal elastic lamina.

Determination of P65 nuclear translocation

HUAECs were transfected with scrambled (control) siRNA or siRNA directed against Piezo1 or Gαq and Gα11 in µ-slide I0.4 Luer slides (Ibidi). 24 h after the second siRNA transfection, cells were grown in the absence of flow (static) or were exposed to oscillatory flow for 48 h. Cells were fixed in flow chambers for 10 min in 4% PFA followed by permeabilization and blocking (0.2% Triton X-100 and 2 mg/ml BSA in 1× PBS at room temperature for 1 h). Cells were then incubated in flow chambers with primary antibody directed against P65 (C22B4, 4764; Cell Signaling), overnight at 4°C (dilution 1:100). After gentle washing with PBS (three times), cells were incubated with corresponding Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Invitrogen) together with DAPI for detection of nuclei (1 ng/ml) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Stained monolayers were analyzed by using a confocal microscope (SP5 Leica).

Histology and immunostaining

For en face immunofluorescence staining, animals were perfused via the left ventricle with 15 ml saline containing heparin (40 units/ml), followed by 15 ml of 4% PFA in PBS. The aorta was removed and opened along the ventral midline. Mouse aortae were fixed with 4% PFA for 45 min at room temperature. Tissue permeabilization and blocking was performed by incubation with 0.2% TritonX-100 (in PBS) and 1% BSA for 1 h in PBS at room temperature under rocking. Atheroprotected and atheroprone areas from the outer and inner curvature of the aorta were dissected. Vessels were incubated at 4°C overnight in PBS containing primary antibodies (dilution 1:100) directed against CD31 (Abcam, ab24590), Vcam-1 (BD Pharmingen, Clone 429, 550547), and CD68 (Serotec, MCA1957). After washing three times in PBS, aortae were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488– and Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200; Invitrogen) together with DAPI (1 ng/ml; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. After washing three times with PBS, tissues were mounted en face with FluoroMount (Sigma, F4680) for confocal imaging. For en face oil-red-O staining of atherosclerotic plaques, aortae were fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C after perfusion (4% PFA, 20 mM EDTA, 5% sucrose in 15 ml PBS). Thereafter, connective tissue and the adventitia were removed, and vessels were cut, opened and pinned en face onto a glass plate coated with silicon. After rinsing with distillated water for 10 min and subsequently with 60% isopropanol, vessels were stained en face with oil-red-O for 30 min with gentle shaking, and were rinsed again in 60% isopropanol and then in tap water for 10 min. Samples were mounted on the coverslips with the endothelial surface facing upwards with glycerol gelatin aqueous mounting media (Sigma).

For morphological analysis of atherosclerotic plaques, the innominate artery and the aortic sinus area attached to the heart were dissected and embedded in optimal cutting temperature medium (Tissue-TekR). Frozen innominate arteries were mounted in a cryotome, and a defined segment 500 to 1,000 µm distal from the origin of the innominate artery was sectioned (10 µm). Sections were then stained with accustain elastic stain kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Frozen aortic outflow tracts were sectioned (10 µm) and stained with oil-red-O for 30 min and mounted with glycerol gelatin. Photoshop CS5 extended software (Adobe), was used to measure atherosclerotic plaque sizes and luminal cross-sectional areas.

To analyze the endothelial layer of the inner and outer aortic curvature, control LDL-receptor–deficient mice or animals with endothelium-specific Gαq/Gα11 deficiency (Ldlr-KO;EC-Gαq/11-KO) were fed a high-fat diet for 4 wk. Aortic arches were cryosectioned (10 µm) and fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min. Optimal cutting temperature tissue-freezing medium (Sakura) was removed by washing with PBS three times for 5 min each, and sections were immunostained with antibodies against phosphorylated FAK (Y397, 1:100 dilution; Cell Signaling, 3283), CD31 (1:100 dilution; BD Biosciences, 550274), or against activated integrin α5 (SNAKA51; Novus Biologicals, NBP2-50146) overnight at 4°C. After washing three times with PBS, bound primary antibodies were detected using Alexa Fluor 488– or 594–conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher, 1:200). DAPI (1 ng/ml; Invitrogen) was used to label cell nuclei. Sections were viewed with a confocal microscope (Leica, SP5). For quantification of pFAK and activated integrin α5 staining at the inner and outer curvature, the endothelial cell area was defined by CD31 staining using ImageJ software, and the fluorescent signal indicating pFAK and integrin α5 was then calculated as percentage of total endothelial cell area.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation

Mouse blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding into EDTA treated tubes (Microvette, NC0973120). The whole blood volume (∼1 ml per mouse) was then diluted with 1× Dulbecco’s PBS without calcium and magnesium (ratio, 1:1). The diluted samples were subjected to density gradient separation on Ficoll Paque PREMIUM 1.084 (GE Healthcare, GE17-5446-02). After centrifugation, the PBMC layer was collected and washed with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma, R7757) to remove remaining red blood cells. PBMC were then washed in 1× PBS and stained for flow cytometric analysis with fluorescently labeled anti–CD45-FITC (eBioscience, clone 30-F11), anti-CD11b-eFluor450 (eBioscience, clone M1/70), anti–Ly6c-PE-Cy7 (Biolegend, clone HK1.4), and anti-Ter119-APC (eBioscience, Ter119) antibodies (at a concentration of 0.2–0.4 µg per 106 cells). Samples were analyzed using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences).

Aortic single cell preparation and flow cytometric analysis

For FACS analysis, animals were anesthetized and their vasculature was perfused by cardiac puncture with 1× PBS containing 20 U/ml of heparin to remove blood from all vessels. Under a dissection microscope, whole aortae were excised and carefully cleaned of all perivascular fat and the adventitia layer was removed in a Petri dish containing 1× PBS. Using micro-scissors, aortic arch segments were opened and inner curvature area was identified. The inner curvature areas from four mice were pooled and analyzed. Inner curvature segments were cut into very small pieces and digested by incubation with an enzyme mixture containing 450 U/ml collagenase I (Sigma, SCR103), 60 U/ml DNase1 (New England Biolabs, M0303), and 312.5 U/ml collagenase II (Worthington, LS004177) in DMEM without serum (Gibco) at 37°C for 30 min with shaking. Single cell suspensions were prepared by passing the digested aorta segments through a 70-µm cell strainer followed by a 40-µm cell strainer (Falcon). Cells were incubated with 7AAD dye (BD Biosciences, 559925) and fluorescently labeled antibodies against CD11c-FITC (BD Biosciences, clone HL3) for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Samples were analyzed using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences).

Intimal RNA isolation from murine aortic curvature

Aortic inner and outer curvature intimal mRNA isolation was performed as previously described (Jongstra-Bilen et al., 2006; Nam et al., 2009) with some minor modifications. In brief, mice were anesthetized and their vasculature was perfused by cardiac puncture with 1× PBS containing 20 U/ml of heparin to remove blood from all vessels. Under a dissection microscope, ascending aorta, aortic arch, and a portion of descending aorta were excised from each mouse. Then aortae were carefully cleaned of all perivascular fat, and the adventitia layer was removed in a Petri dish containing RNA-later reagent (RNA-later, Qiagen). Using micro-scissors, aortic arch segments were opened and inner and outer curvature areas were isolated. Intimal cells from these regions were gently scraped with a 26-G needle, flushed with 150 µl QIAzol lysis reagent (Qiagen), and the eluate was collected in a microfuge tube. RNA isolation was performed using an miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For each experiment, intimal cells were pooled from two aortae. Data were normalized to the housekeeping gene Hprt. Murine primer sequences are as follows: Hprt: forward 5′-GTCAACGGGGGACATAAAAG-3′, reverse 5′-CAACAATCAAGACATTCTTTCCA-3′; and Vcam-1: forward 5′-CCGGTCACGGTCAAGTGT-3′, reverse 5′-CAGATCAATCTCCAGCCTGTAA-3′.

SNAKA51 staining in murine lung endothelial cells (MLECs)

C57BL/6 mouse primary lung endothelial cells (Pelobiotech, C57-6011) were plated in µ-slide I0.4 Luer ibiTreat chambers (Ibidi, 80176) and transfected with scrambled (control) siRNA or siRNA directed against Itga5. The targeted sequences of mouse siRNAs directed against RNAs encoding Itga5 were 5′-ACCATTCAATTTGACAGCAAA-3′, 5′-CAGATCCATGGAAGTCAGAAA-3′, and 5′-AGCGGGAATACCAGCCATTTA-3′. 24 h after the second siRNA transfection, cells were grown in the absence of flow (static) or were exposed to oscillatory flow for 24 h. Cells were fixed in flow chambers for 10 min in 4% PFA followed by permeabilization and blocking (0.2% Triton X-100 and 2 mg/ml BSA in 1× PBS at room temperature for 1 h). Cells were then incubated in flow chambers with primary antibody directed against activated integrin α5, SNAKA51 (Novus Biologicals, NBP2-50146), overnight at 4°C (1:100 dilution). After gentle washing with PBS (three times), cells were incubated with corresponding Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibody (1:200, Invitrogen) together with DAPI for detection of nuclei (1 ng/ml) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Stained monolayers were analyzed by using a confocal microscope (SP5 Leica).

Pharmacological inhibition of integrin signaling

HUAECs were seeded in µ-slide I0.4 Luer ibiTreat chambers (80176, Ibidi) and unidirectional laminar or oscillatory flow was applied as described above. After cells were adapted to laminar flow for 24 h, confluent monolayers were treated with 50 μmol/L of the α5β1 integrin inhibitor ATN-161 (Tocris, 6058) or with 1 μmol/L of the αv integrin inhibitor S247 (Tocris, 5870), for 10 min and shear stress-induced signaling was assessed.

Total cholesterol assay

Following a 4-h fast, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and retro-orbital blood was obtained via EDTA-coated microcapillary tubes (Microvette, NC0973120). Cholesterol levels from mouse plasma (dilution 1:400) were quantified using a cholesterol fluorometric assay kit (Cayman, 10007640) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analysis is included in every figure and described in detail on the respective figure legends. The exact P values and number of cells analyzed per condition (n) are stated in the figures and figure legends. All experiments were repeated three times (independent replicates); n represents a pool across these experimental replicates. Trial experiments or experiments done previously were used to determine sample size with adequate statistical power. Samples were excluded in cases where RNA/cDNA quality or tissue quality after processing was poor (below commonly accepted standards). Data are presented as means ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad). A level of P < 0.05 was considered significant and reported to the graphs. Comparisons between two groups were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test and multiple group comparisons at different time points were performed by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the knock-down efficiency of Piezo1, P2RY2, Gαq, and Gα11 in HUAECs, as well as the effect of Gαq/Gα11- and Piezo1 knock-down on oscillatory flow-induced expression of VCAM-1, CCL2, and PDGFB in HUAECs. Fig. S2 shows Vcam-1 expression and presence of CD68-positive cells in the endothelium and subendothelium of the aortic outer curvature of wild-type and EC- Gαq/11-KO and EC-Piezo1-KO animals. Fig. S3 shows Vcam-1 expression in the endothelium of the inner and outer curvature of the aorta from EC-P2Y2-KO mice, as well as the plaque/neointima area of Ldlr-KO;EC-P2Y2-KO mice after partial carotid artery ligation. Fig. S4 shows Vcam-1 mRNA levels in the inner and outer aortic curvature of wild-type, EC-Gαq/11-KO, and EC-Piezo1-KO mice, presence of CD11c+-cells in the inner curvature of wild-type, EC-Gαq/11-KO, and EC-Piezo1-KO mice, and the total cholesterol plasma levels and levels of Ly6c-positive cells in the blood of Ldlr-KO, Ldlr-KO;EC-Gαq/11-KO, and Ldlr-KO;EC-Piezo1-KO mice. Fig. S5 shows the effect of the integrin α5 and αv blockers ATN-161 and S247 on disturbed flow-induced phosphorylation of FAK and P65 in HUAECs, as well as data indicating that the monoclonal anti-integrin α5 antibody SNAKA51 can recognize activated mouse integrin α5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Karin Jäcklein, Ulrike Krüger, and Claudia Ullmann for their expert technical assistance and Svea Hümmer for excellent secretarial help. The authors wish to thank Reinhard Fässler for helpful discussions.

Part of the work was supported by the German Research Foundation's Transregional Collaborative Research Center 23 (SFB/TR23) and the Collaborative Research Center 834 (SFB834).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: J. Albarrán-Juárez performed most of the in vitro and in vivo experiments, analyzed and discussed data, and contributed to writing of the manuscript; T.F. Althoff performed initial in vitro and in vivo experiments, initiated the study, analyzed and discussed data, and contributed to writing of the manuscript; A. Iring, S. Wang, S. Joseph, M. Grimm, and B. Strilic helped with ATP measurements, generation and analysis of Piezo1-deficent mice, analysis of atherosclerosis, and immunofluorescence imaging; N. Wettschureck initiated and supervised study, discussed data, and commented on the manuscript; S. Offermanns initiated and supervised study, discussed data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Abramoff M.D., Magalhaes P.J., and Ram S.J.. 2004. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophoton. Int. 11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Alva J.A., Zovein A.C., Monvoisin A., Murphy T., Salazar A., Harvey N.L., Carmeliet P., and Iruela-Arispe M.L.. 2006. VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev. Dyn. 235:759–767. 10.1002/dvdy.20643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeyens N., and Schwartz M.A.. 2016. Biomechanics of vascular mechanosensation and remodeling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 27:7–11. 10.1091/mbc.e14-11-1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeyens N., Mulligan-Kehoe M.J., Corti F., Simon D.D., Ross T.D., Rhodes J.M., Wang T.Z., Mejean C.O., Simons M., Humphrey J., and Schwartz M.A.. 2014. Syndecan 4 is required for endothelial alignment in flow and atheroprotective signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:17308–17313. 10.1073/pnas.1413725111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagi Z., Frangos J.A., Yeh J.C., White C.R., Kaley G., and Koller A.. 2005. PECAM-1 mediates NO-dependent dilation of arterioles to high temporal gradients of shear stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25:1590–1595. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000170136.71970.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhullar I.S., Li Y.S., Miao H., Zandi E., Kim M., Shyy J.Y., and Chien S.. 1998. Fluid shear stress activation of IkappaB kinase is integrin-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30544–30549. 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodin P., Bailey D., and Burnstock G.. 1991. Increased flow-induced ATP release from isolated vascular endothelial cells but not smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 103:1203–1205. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12324.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boo Y.C., Hwang J., Sykes M., Michell B.J., Kemp B.E., Lum H., and Jo H.. 2002. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser(635) by a protein kinase A-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 283:H1819–H1828. 10.1152/ajpheart.00214.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budatha M., Zhang J., Zhuang Z.W., Yun S., Dahlman J.E., Anderson D.G., and Schwartz M.A.. 2018. Inhibiting Integrin α5 Cytoplasmic Domain Signaling Reduces Atherosclerosis and Promotes Arteriogenesis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7:e007501 10.1161/JAHA.117.007501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann M.H., Dieterich P., Adams N.A., and Schnittler H.J.. 2005. Analysis of flow in a cone-and-plate apparatus with respect to spatial and temporal effects on endothelial cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 89:493–502. 10.1002/bit.20165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Green J., Yurdagul A. Jr., Albert P., McInnis M.C., and Orr A.W.. 2015. αvβ3 Integrins Mediate Flow-Induced NF-κB Activation, Proinflammatory Gene Expression, and Early Atherogenic Inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 185:2575–2589. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Qian S., Hoggatt A., Tang H., Hacker T.A., Obukhov A.G., Herring P.B., and Seye C.I.. 2017. Endothelial Cell-Specific Deletion of P2Y2 Receptor Promotes Plaque Stability in Atherosclerosis-Susceptible ApoE-Null Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37:75–83. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu J.J., and Chien S.. 2011. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol. Rev. 91:327–387. 10.1152/physrev.00047.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.H., Do Y., Cheong C., Koh H., Boscardin S.B., Oh Y.S., Bozzacco L., Trumpfheller C., Park C.G., and Steinman R.M.. 2009. Identification of antigen-presenting dendritic cells in mouse aorta and cardiac valves. J. Exp. Med. 206:497–505. 10.1084/jem.20082129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K., Pankov R., Travis M.A., Askari J.A., Mould A.P., Craig S.E., Newham P., Yamada K.M., and Humphries M.J.. 2005. A specific alpha5beta1-integrin conformation promotes directional integrin translocation and fibronectin matrix formation. J. Cell Sci. 118:291–300. 10.1242/jcs.01623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C.D., Bae C., Ziegler L., Hartley S., Nikolova-Krstevski V., Rohde P.R., Ng C.A., Sachs F., Gottlieb P.A., and Martinac B.. 2016. Removal of the mechanoprotective influence of the cytoskeleton reveals PIEZO1 is gated by bilayer tension. Nat. Commun. 7:10366 10.1038/ncomms10366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P.F. 2009. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 6:16–26. 10.1038/ncpcardio1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P.F., Robotewskyj A., and Griem M.L.. 1994. Quantitative studies of endothelial cell adhesion. Directional remodeling of focal adhesion sites in response to flow forces. J. Clin. Invest. 93:2031–2038. 10.1172/JCI117197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P.F., Barbee K.A., Volin M.V., Robotewskyj A., Chen J., Joseph L., Griem M.L., Wernick M.N., Jacobs E., Polacek D.C., et al. 1997. Spatial relationships in early signaling events of flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59:527–549. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit M., Loot A.E., Mohamed A., Fisslthaler B., Boulanger C.M., Ceacareanu B., Hassid A., Busse R., and Fleming I.. 2005. Gab1, SHP2, and protein kinase A are crucial for the activation of the endothelial NO synthase by fluid shear stress. Circ. Res. 97:1236–1244. 10.1161/01.RES.0000195611.59811.ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaver R.E., Gelfand B.D., Wang C., Schwartz M.A., and Blackman B.R.. 2010. Atheroprone hemodynamics regulate fibronectin deposition to create positive feedback that sustains endothelial inflammation. Circ. Res. 106:1703–1711. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney A.C., Stokes K.Y., Pattillo C.B., and Orr A.W.. 2017. Integrin signaling in atherosclerosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74:2263–2282. 10.1007/s00018-017-2490-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I., Fisslthaler B., Dixit M., and Busse R.. 2005. Role of PECAM-1 in the shear-stress-induced activation of Akt and the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 118:4103–4111. 10.1242/jcs.02541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung Y.C., and Liu S.Q.. 1993. Elementary mechanics of the endothelium of blood vessels. J. Biomech. Eng. 115:1–12. 10.1115/1.2895465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 388:1459–1544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbrone M.A. Jr., and García-Cardeña G.. 2016. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 118:620–636. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens C., and Tzima E.. 2016. Endothelial Mechanosignaling: Does One Sensor Fit All? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 25:373–388. 10.1089/ars.2015.6493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C., and Schwartz M.A.. 2008. The role of cellular adaptation to mechanical forces in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28:2101–2107. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C., and Schwartz M.A.. 2009. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:53–62. 10.1038/nrm2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry B.L., Sanders J.M., Feaver R.E., Lansey M., Deem T.L., Zarbock A., Bruce A.C., Pryor A.W., Gelfand B.D., Blackman B.R., et al. 2008. Endothelial cell PECAM-1 promotes atherosclerotic lesions in areas of disturbed flow in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28:2003–2008. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.164707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington W., Lacey B., Sherliker P., Armitage J., and Lewington S.. 2016. Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease. Circ. Res. 118:535–546. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.L., Bax N.A., Buckley C.D., Weis W.I., and Dunn A.R.. 2017. Vinculin forms a directionally asymmetric catch bond with F-actin. Science. 357:703–706. 10.1126/science.aan2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi S., Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L., Gerard R.D., Hammer R.E., and Herz J.. 1993. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J. Clin. Invest. 92:883–893. 10.1172/JCI116663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John K., and Barakat A.I.. 2001. Modulation of ATP/ADP concentration at the endothelial surface by shear stress: effect of flow-induced ATP release. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 29:740–751. 10.1114/1.1397792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongstra-Bilen J., Haidari M., Zhu S.N., Chen M., Guha D., and Cybulsky M.I.. 2006. Low-grade chronic inflammation in regions of the normal mouse arterial intima predisposed to atherosclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 203:2073–2083. 10.1084/jem.20060245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen H., Fisslthaler B., Moers A., Wirth A., Habermehl D., Wieland T., Schütz G., Wettschureck N., Fleming I., and Offermanns S.. 2009. Anaphylactic shock depends on endothelial Gq/G11. J. Exp. Med. 206:411–420. 10.1084/jem.20082150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A.H., and Grandl J.. 2015. Mechanical sensitivity of Piezo1 ion channels can be tuned by cellular membrane tension. eLife. 4:e12088 10.7554/eLife.12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wang Y., Goh W.I., Goh H., Baird M.A., Ruehland S., Teo S., Bate N., Critchley D.R., Davidson M.W., and Kanchanawong P.. 2015. Talin determines the nanoscale architecture of focal adhesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112:E4864–E4873. 10.1073/pnas.1512025112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan S., Mohan N., and Sprague E.A.. 1997. Differential activation of NF-kappa B in human aortic endothelial cells conditioned to specific flow environments. Am. J. Physiol. 273:C572–C578. 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel T., Resnick N., Dewey C.F. Jr., and Gimbrone M.A. Jr. 1999. Vascular endothelial cells respond to spatial gradients in fluid shear stress by enhanced activation of transcription factors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19:1825–1834. 10.1161/01.ATV.19.8.1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H., and Mochizuki N.. 2017. Flow pattern-dependent endothelial cell responses through transcriptional regulation. Cell Cycle. 16:1893–1901. 10.1080/15384101.2017.1364324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam D., Ni C.W., Rezvan A., Suo J., Budzyn K., Llanos A., Harrison D., Giddens D., and Jo H.. 2009. Partial carotid ligation is a model of acutely induced disturbed flow, leading to rapid endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297:H1535–H1543. 10.1152/ajpheart.00510.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam D., Ni C.W., Rezvan A., Suo J., Budzyn K., Llanos A., Harrison D.G., Giddens D.P., and Jo H.. 2010. A model of disturbed flow-induced atherosclerosis in mouse carotid artery by partial ligation and a simple method of RNA isolation from carotid endothelium. J. Vis. Exp. (40):1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro P., Abe J., and Berk B.C.. 2011. Flow shear stress and atherosclerosis: a matter of site specificity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15:1405–1414. 10.1089/ars.2010.3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordenfelt P., Moore T.I., Mehta S.B., Kalappurakkal J.M., Swaminathan V., Koga N., Lambert T.J., Baker D., Waters J.C., Oldenbourg R., et al. 2017. Direction of actin flow dictates integrin LFA-1 orientation during leukocyte migration. Nat. Commun. 8:2047 10.1038/s41467-017-01848-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr A.W., Sanders J.M., Bevard M., Coleman E., Sarembock I.J., and Schwartz M.A.. 2005. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates NF-kappaB activation by flow: a potential role in atherosclerosis. J. Cell Biol. 169:191–202. 10.1083/jcb.200410073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr A.W., Ginsberg M.H., Shattil S.J., Deckmyn H., and Schwartz M.A.. 2006. Matrix-specific suppression of integrin activation in shear stress signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:4686–4697. 10.1091/mbc.e06-04-0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold T., Orr A.W., Hahn C., Jhaveri K.A., Parsons J.T., and Schwartz M.A.. 2009. Focal adhesion kinase modulates activation of NF-kappaB by flow in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297:C814–C822. 10.1152/ajpcell.00226.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Fu Y., Gu M., Zhang L., Li D., Li H., Chien S., Shyy J.Y., and Zhu Y.. 2016. Activation of integrin α5 mediated by flow requires its translocation to membrane lipid rafts in vascular endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113:769–774. 10.1073/pnas.1524523113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan V., Alushin G.M., and Waterman C.M.. 2017a Mechanosensation: A Catch Bond That Only Hooks One Way. Curr. Biol. 27:R1158–R1160. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan V., Kalappurakkal J.M., Mehta S.B., Nordenfelt P., Moore T.I., Koga N., Baker D.A., Oldenbourg R., Tani T., Mayor S., et al. 2017b Actin retrograde flow actively aligns and orients ligand-engaged integrins in focal adhesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114:10648–10653. 10.1073/pnas.1701136114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbell J.M., Shi Z.D., Dunn J., and Jo H.. 2014. Fluid Mechanics, Arterial Disease, and Gene Expression. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 46:591–614. 10.1146/annurev-fluid-010313-141309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]