Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a worldwide health concern which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Both viral and host factors have a significant effect on infection, replication and pathogenesis of HBV. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of CYP2E1 and CYP1A1 genetic variants on susceptibility to HBV. 143 individuals including 54 chronic HBV patients and 89 healthy controls were enrolled in the genotyping procedure. rs2031920 and rs3813867 at CYP2E1 as well as rs4646421 and rs2198843 at CYP1A1 loci were studied in all subjects using PCR–RFLP (restriction fragment length polymorphism) analysis. Both variants at CYP2E1 locus were monomorphic in all studied subjects. Genotype frequency of rs4646421 was significantly different between chronic HBV patients and healthy blood donors (P = 0.04, OR 4.31; 95% CI 1.04–17.7). Furthermore, individuals carrying at least one C allele (CC or CT genotypes) for rs4646421 seemed to have a decrease risk of hepatitis in comparison with TT genotype (P = 0.039). Our results showed a relationship between rs4646421 TT genotype (rare genotype) and the risk for developing chronic HBV infection (four times higher). Further studies are needed to examine the role of CYP1A1 polymorphism in susceptibility to chronic HBV infection.

Keywords: Hepatitis, Cytochrome P450, CYP2E1, CYP1A1, RFLP

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is an important global health problem which may lead to significant morbidity and mortality especially in developing countries [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 2 billion people have been infected worldwide with HBV, among which more than 350 million are chronically infected [2] with the highest prevalence being observed in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Greenland [3]. The infection can cause acute and chronic liver diseases, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [4]. It has been well documented that both viral and host factors have a significant effect on infection, replication and pathogenesis of HBV [5–7]. The host factors for HBV pathogenesis include environmental factors (alcohol and aflotoxin) and genetic factors. Therefore, some host genes may act as strong contributors to disease outcome [8]. Genes controlling drugs and metabolism such as cytochrome P450 (CYP 450) may exert an important effect on disease development. Cytochrome P4502E1 (CYP2E1) enzyme is a member of the CYP 450 superfamily which is important for the metabolic activation of many toxic materials [9, 10]. Also, many drugs or small molecules are inducers of CYP P450 enzymes [11]. CYP2E1 which is primarily expressed in the liver, represents a major CYP isoform in the liver [12]. The CYP2E1 gene could play an important role in human susceptibility to liver cancer [13]. CYP2E1 has several variants and its functional variants are associated with increased or decreased susceptibility to many cancer types, including esophageal, lung, colorectal and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [14, 15]. The CYP1A1 enzyme is essential for the catalysis of the first step of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) metabolism, and therefore has been considered as a primary candidate in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) susceptibility [16]. Two genetic variants of CYP1A1 have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of HCC in smokers, but the association was not replicated in subsequent studies [13]. The aim of this study was to investigate for the first time the association between CYP2E1 and CYP1A1 variants with susceptibility to HBV infection in a population of North Iran.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This study included 54 patients (38 male, 16 female) aged between 18 and 68 years who were referred to Razi hospital in Ghaemshahr, Iran, and 89 healthy controls that were referred to Valiasr hospital in Ghaemshahr, Iran. Participants gave their consent to be included in the study. The diagnosis of acute or chronic HBV infection was based on serology for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs Ag) and the presence of HBV DNA which was investigated by real-time PCR assay. Demographic and serological features of the HBV infected patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the HBV infected patients

| HBV infected patients (n = 54) | |

|---|---|

| Age range (years) | 16–68 |

| Gender [n (%)] | |

| Female | 38 (70) |

| Male | 16 (30) |

| Serum HBs Ag | |

| Positive [n (%)] | 54 (100) |

| Negative [n (%)] | 0 (0) |

| HBV DNA | |

| Positive [n (%)] | 54 (100) |

| Negative [n (%)] | 0 (0) |

DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA of HBV infected patients was extracted from 200 μl of whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kits (Qiagen Inc., USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Healthy controls’ genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using salting out method as previously described [17].

PCR–RFLP Analysis of CYP2E1 and CYP1A1 Variants

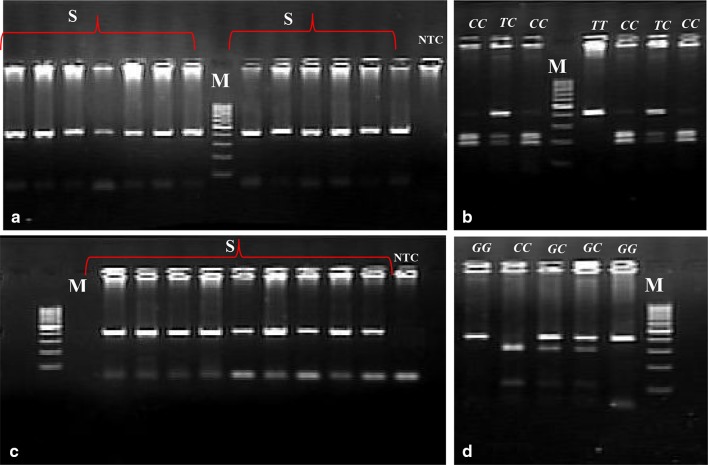

After DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) was used to examine the genetic variants (rs3813867 and rs2031920) of CYP2E1, and (rs4646421and rs2198843) CYP1A1 as previously described [17]. Briefly, the PCR was carried out using the specific primers for each variant followed by digestion with appropriate restriction enzymes. For CYP2E1 variants (rs3813867 and rs2031920), the PCR products were digested with RsaI and PstI, and classified into three types according to the digestion pattern, as follows: a predominant homozygous (RsaI+/PstI−), a heterozygous (RsaI+/PstI+), and a rare homozygous (RsaI−/PstI+) genotype (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

RFLP analysis of CYP2E1 gene. a Undigested PCR products (413 bp); b PCR products digested with RsaI and PstI. Lanes M: Molecular Weight Marker (50-bp ladder); lanes S: samples

The PCR products of CYP1A1 variants (rs4646421 and rs2198843) were subjected to digestion by NspI or PstI restriction enzymes, respectively. The expected sizes of the products after digestion with NspI were 417 bp for the G allele (no cutting), 231 and 138 bp for the C allele (Fig. 2c). Digestion with PstI showed 105 bp and 299 bp fragments for the C allele, while the G allele remained uncut with 404 bp size (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Electrophoresis pattern of PCR–RFLP for detection of CYP1A1 variants. a, c Undigested PCR products for rs4646421 and rs2198843, respectively; b, d PCR products digested with NspI and PstI, respectively. Lanes M: Molecular Weight Marker (100-bp ladder); lanes S: samples

Results

Patients Characterization

Chronic HBV infection was defined as individuals who tested positive for HBs Ag and HBV DNA for more than 6 months. Among the HBV infected patients all individuals showed positive level of HBs Ag and HBV DNA, whereas all healthy controls were negative for HBs Ag and HBV DNA.

Alleles and Genotypes Frequencies of rs2031920 and rs3813867 at CYP2E1 Locus

Genotype frequencies of both single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were monomorphic in HBV infected patients and healthy controls (predominant homozygous RsaI+/PstI− genotype). Therefore, there was no difference in genotype frequencies between HBV infected patients and healthy controls.

Alleles and Genotypes Frequencies of rs4646421 and rs2198843 at CYP1A1 Locus

The distributions of the genotypes and alleles of rs4646421 and rs2198843 are summarized in Table 2. The frequency of C and T alleles for rs4646421 were 0.82 and 0.17, respectively among the healthy controls, compared to 0.76 and 0.24, respectively in HBV infected patients. As shown in Table 2, 61.1% of patients and 68.5% of controls had the CC genotype. The distribution of CT and TT genotypes in HBV infected patients was 25.9 and 12.9%, respectively compared to 28.09 and 3.3% in healthy controls. Therefore, TT genotype was significantly more prevalent in HBV infected patients [P = 0.04, OR 4.31 (1.04–17.7)] in comparison with healthy controls. The G and C allele frequencies for rs2198843 were found to be 0.704 and 0.296, respectively among healthy controls, compared to 0.76 and 0.24, respectively among HBV infected patients. The homozygous wild type genotype (GG) frequency was 52.8% in normal and 48.18% in HBV infected patients whereas the heterozygous genotype (GC) frequency was 35.9% in healthy controls and 42.59% in HBV infected patients. Moreover, 11.2% of healthy controls carried the mutant homozygous allele (CC genotype) while this genotype was found in 9.25% of the HBV infected patients. However, there was no statistical difference in genotype frequencies among the two groups. Genotype frequencies of both variants were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Haplotype data for CYP1A1 locus is shown in Table 3. Four haplotypes were identified in HBV infected patients as well as healthy controls. The haplotype [C; G] was predominant in HBV infected patients (61%) and healthy controls (58.6%). In this study, [T; G] haplotype was rare in both studied groups.

Table 2.

Distribution of cytochrome P450 1A1 genotypes and alleles frequencies in HBV infected patients compared to healthy controls for rs4646421 and rs2198843

| SNP | Genotype/allele | Healthy controls n |

HBV infected patients n |

OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4646421 | CC | 61 (68.5%) | 33 (61.1%) | 1 | |

| CT | 25 (28.09%) | 14 (25.9%) | 1.03 (0.47–2.2) | 0.93 | |

| TT | 3 (3.3%) | 7 (12.9%) | 4.31 (1.04–17.7) | 0.04 | |

| C | 0.82 | 0.74 | |||

| T | 0.17 | 0.26 | |||

| rs2198843 | GG | 47 (52. 8%) | 26 (48.18%) | 1 | |

| GC | 32 (35.9%) | 23 (42.59%) | 1.29 (0.63–2.6) | 0.47 | |

| CC | 10 (11.2%) | 5 (9.25%) | 1.1 (0.34–3.5) | 0.86 | |

| G | 0.704 | 0.768 | |||

| C | 0.296 | 0.232 |

Table 3.

Association between [rs3813867; rs2031920] haplotypes of CYP1A1

| Haplotype | Normal na |

Hepatitis na |

OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 109 (58.6%) | 61 (61%) | 1.00 | |

| CC | 24 (12.9%) | 6 (6%) | 0.4467 (0.17–1.15) | 0.0957 |

| TG | 3 (1.62%) | 6 (6%) | 3.5738 (0.86–14.79) | 0.0789 |

| TC | 10 (5.38%) | 9 (9%) | 1.6082 (0.61–4.17) | 0.3288 |

a For 17.9% of the analyzed healthy controls and 24% of HBV infected patients, haplotype assignment was not possible due to heterozygosity in both loci

Discussion

Several studies showed that hepatitis replication is highly dependent on host cell factors [18–21]. Although the role of CYPs genetic variants is clear in dealing with development of HCC, there is limited data about their association with susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B infection. A number of studies demonstrated that the hepatic CYPs are important in pathogenesis of several liver diseases. Li et al. [22] showed that chronic HBV infection down-regulates the expression of hepatic CYP3A4. Furthermore, Iizuka et al. [23] showed that the expression level of 28 CYPs were significantly changed in HBV- and/or HCV-infected livers compared with normal livers. However, there is no information about the impact of CYP2E1 and CYP1A1 genetic variants on HBV pathogenesis. In this study, polymorphisms in CYP2E1 and CYP1A1 genes were studied in 89 healthy controls and 54 HBV infected patients. According to the results of the present study, genotypes and alleles frequency analyzes for rs2031920 and rs3813867 showed that both HBV infected patients and healthy controls had only homozygous wild type genotype, indicating that these variants are monomorphic in the studied population. These data are in line with another study performed in Iran [24]. The genotype distribution in Iranian population is similar to Indian, Turkish, and some European populations such as German, British and French [25–29], but is different from Japanese and Chinese, and also from Italians [30–32]. Some studies showed that CYP2E1 variants were associated with HCC risk. Tian et al. [13] in a meta-analysis showed that the c2 allele of CYP2E1 may be a protective factor for HCC among East Asians, especially among China populations. Allele frequency study for rs2198843 showed that allelic distribution was approximately similar in both healthy controls and HBV infected patients. There was no significant difference in genotypes and allele frequencies among the HBV infected patients and healthy controls. In the present study, genotype analysis for rs4646421 showed that the frequency of TT genotype was higher in HBV infected patients compared with healthy controls. A significant association was observed between healthy controls and HBV infected patients (P = 0.04), and hepatitis development risk was approximately four times greater in individuals with TT genotype than individuals with CC genotype. Nakai et al. [33] showed that the development of early stages of chronic hepatitis C infection was associated with drug metabolism enzymes such as CYP1A2, CYP2E1 and CYP3A4. Makpol et al. [34] indicated a significant relationship between CYP1A1 genetic variants and HCC risk in Malaysian population. In another study, Yu et al. [35] showed that CYP1A1 variants play an important role in hepatocarcinogenic effect of PAHs. Li et al. [16] demonstrated that rs2198843 and rs4646421 variants carriers have an increased HCC risk. In conclusion, individuals who have had TT genotype at rs4646421 locus were more susceptible to HBV infection development. It can also be concluded that the prevalence of HBV infection is higher in subjects with [T; G] and [T; C] haplotypes than in subjects with [C; G] and [C; C] haplotypes.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge all people who consented to participate to this study.

Contributor Information

Sadegh Fattahi, Email: Fattahi_pgs@yahoo.com.

Mohsen Asouri, Email: Mohsen.asouri@yahoo.com.

Maryam Lotfi, Email: Lotfi2545@yahoo.com.

Galia Amirbozorgi, Email: galia1926@yahoo.com.

Haleh Akhavan-Niaki, Phone: +989111255920, Email: halehakhavan@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Hou J, Liu Z, Gu F. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. Int J Med Sci. 2005;2(1):50. doi: 10.7150/ijms.2.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aspinall E, Hawkins G, Fraser A, Hutchinson S, Goldberg D. Hepatitis B prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care: a review. Occup Med. 2011;61(8):531–540. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiollais P, Pourcel C, Dejean A. The hepatitis B virus. 1985;317:489–495. doi: 10.1038/317489a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu M-W, Chen C-J. Hepatitis B and C viruses in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1994;17(2):71–91. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw YF. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and long-term outcome under treatment. Liver Int. 2009;29(Suppl 1):100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaefer S. Hepatitis B virus: significance of genotypes. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12(2):111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thursz M. Genetic susceptibility in infectious diseases. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2000;17:253–264. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2000.10647994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mafi Golchin M, Heidari L, Ghaderian SM, Akhavan-Niaki H. Osteoporosis: a silent disease with complex genetic contribution. J Genet Genomics. 2016;43(2):49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai L, Zheng Z-L, Zhang Z-F. Cytochrome p450 2E1 polymorphisms and the risk of gastric cardia cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(12):1867–1871. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun JY, Park BL, Cheong HS, Kim JY, Park TJ, Lee JS, et al. Identification of polymorphisms in CYP2E1 gene and association analysis among chronic HBV patients. Genomics Inform. 2009;7(4):187–194. doi: 10.5808/GI.2009.7.4.187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch T, Price A. The effect of cytochrome P450 metabolism on drug response, interactions, and adverse effects. Am Fam Phys. 2007;76(3):391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin H-L, Roberts ES, Hollenberg PF. Heterologous expression of rat P450 2E1 in a mammalian cell line: in situ metabolism and cytotoxicity of N-nitrosodimethylamine. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(2):321–329. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian Z, Li Y-L, Zhao L, Zhang C-L. CYP2E1 RsaI/PstI polymorphism and liver cancer risk among east Asians: a HuGE review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:4915–4921. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.10.4915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su X, Bin B, Cui H, Ran M. Cytochrome P450 2E1 RsaI/PstI and DraI polymorphisms are risk factors for lung cancer in Mongolian and Han population in inner Mongolia. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23(2):107–111. doi: 10.1007/s11670-011-0107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvestri L, Sonzogni L, De Silvestri A, Gritti C, Foti L, Zavaglia C, et al. CYP enzyme polymorphisms and susceptibility to HCV-related chronic liver disease and liver cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(3):310–317. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li R, Shugart YY, Zhou W, An Y, Yang Y, Zhou Y, et al. Common genetic variations of the cytochrome P450 1A1 gene and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese population. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fattahi S, Yousefi GA, Amirbozorgi G, Lotfi M, Naeiji A, Asouri M, et al. Lack of association of CYP2E1 and CYP1A1 polymorphisms with osteoporosis in postmenauposal women. Int Biol Biomed J. 2015;1(2):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang FS. Current status and prospects of studies on human genetic alleles associated with hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(4):641–644. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i4.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Wu XP, Zhang W, Zhu DH, Wang Y, Li YP, et al. Evaluation of genetic susceptibility loci for chronic hepatitis B in Chinese: two independent case-control studies. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He YL, Zhao YR, Zhang SL, Lin SM. Host susceptibility to persistent hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(30):4788–4793. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i30.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yano Y, Seo Y, Azuma T, Hayashi Y. Hepatitis B virus and host factors. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2013;2(2):121. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2012.10.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S, Hu Z, Miao X. Effects of chronic HBV infection on human hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;86(38):2703–2706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iizuka N, Oka M, Hamamoto Y, Mori N, Tamesa T, Tangoku A, et al. Altered levels of cytochrome P450 genes in hepatitis B or C virus-infected liver identified by oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2004;1(1):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahriary GM, Galehdari H, Jalali A, Zanganeh F, Alavi S, Aghanoori MR. CYP2E1* 5B, CYP2E1* 6, CYP2E1* 7B, CYP2E1* 2, and CYP2E1* 3 allele frequencies in Iranian populations. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:6505–6510. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.12.6505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang B, O’Reilly DA, Demaine AG, Kingsnorth AN. Study of polymorphisms in the CYP2E1 gene in patients with alcoholic pancreatitis. Alcohol. 2001;23(2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/S0741-8329(00)00135-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuhaus T, Ko YD, Lorenzen K, Fronhoffs S, Harth V, Brode P, et al. Association of cytochrome P450 2E1 polymorphisms and head and neck squamous cell cancer. Toxicol Lett. 2004;151(1):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouchardy C, Hirvonen A, Coutelle C, Ward PJ, Dayer P, Benhamou S. Role of alcohol dehydrogenase 3 and cytochrome P-4502E1 genotypes in susceptibility to cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Int J Cancer. 2000;87(5):734–740. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000901)87:5<734::AID-IJC17>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konstandi M, Cheng J, Gonzalez FJ. Sex steroid hormones regulate constitutive expression of Cyp2e1 in female mouse liver. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304(10):E1118–E1128. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00585.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ulusoy G, Arinc E, Adali O. Genotype and allele frequencies of polymorphic CYP2E1 in the Turkish population. Arch Toxicol. 2007;81(10):711–718. doi: 10.1007/s00204-007-0200-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boccia S, Cadoni G, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Volante M, Arzani D, De Lauretis A, et al. CYP1A1, CYP2E1, GSTM1, GSTT1, EPHX1 exons 3 and 4, and NAT2 polymorphisms, smoking, consumption of alcohol and fruit and vegetables and risk of head and neck cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(1):93–100. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinones L, Lucas D, Godoy J, Caceres D, Berthou F, Varela N, et al. CYP1A1, CYP2E1 and GSTM1 genetic polymorphisms. The effect of single and combined genotypes on lung cancer susceptibility in Chilean people. Cancer Lett. 2001;174(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00686-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sangrajrang S, Jedpiyawongse A, Srivatanakul P. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2E1 and GSTM1 in a Thai population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7(3):415–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakai K, Tanaka H, Hanada K, Ogata H, Suzuki F, Kumada H, et al. Decreased expression of cytochromes P450 1A2, 2E1, and 3A4 and drug transporters Na+-taurocholate-cotransporting polypeptide, organic cation transporter 1, and organic anion-transporting peptide-C correlates with the progression of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(9):1786–1793. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.020073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makpol S, Mamat S, Ahmad Z, Ngah WZW. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP1A1 (m1),(m2),(m4) and CYP2A6 and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma in a Malaysian study population. Malays J Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;12(1):31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu MW, Chiu YH, Yang SY, Santella RM, Chern HD, Liaw YF, et al. Cytochrome P450 1A1 genetic polymorphisms and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among chronic hepatitis B carriers. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(3–4):598–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]