Abstract

This study examined the biological functions of the butanol extracts of green pine cones (GPCs) that had not ripened completely. The butanol extracts of GPC showed 78.22% DPPH-scavenging activity, 53.55% TEAC and 71.50% hyaluronidase (HAase) inhibition activity. They also exhibited inhibition activity against food poisoning microorganisms. The contents of total phenolic compounds and total flavonoids were 296.75 and 26.07 mg/g, respectively. Biologically active compounds were analyzed and separated using HPLC related to the DPPH-scavenging and HAase inhibition activities. Gallotannin was the primary biologically active compound with DPPH-scavenging and HAase inhibition activities in the GPC butanol extracts.

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, HAase inhibition activity, Antimicrobial activity, Green pine cone

Introduction

An inflammatory response can occur as reaction to any type of injured tissue, pathogen or damaged cell that is accompanied by swelling, release of blood vessels, and fluid extravasation (Ferrero-Miliani et al., 2007). This process is self-limiting under normal conditions. On the other hand, some chronic inflammatory diseases can sustain the inflammatory process. Hyaluronan, which is bound to proteoglycans, is a common polymer in the tissue. Initiating the host responses to a tissue injury, a hyaluronan fragment is produced by a non-enzymatic reaction, and hyaluronidase (HAase), which depolymerizes polymeric hyaluronic acid (HA) in the extracellular matrix to produce HA oligosaccharides, is associated with the biological properties, such as wound healing, cancer metastasis, and inflammation (Bertolami and Donoff, 1978; Borchard et al., 2010; Laurent and Fraser, 1992; Meyer, 1947).

As the average life expectancy has increased, diverse diseases in adults, such as cancer and ageing, have attracted considerable research attention in recent years. One of causes of these diseases is ‘free radicals’, such as reactive oxygen species, from the cellular metabolism (Devasagayam et al., 2004). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radicals, and singlet oxygen, have high chemical activity. They are produced naturally in the body and are utilized in the protective mechanism of the signaling pathways in the cellular function (Muller et al., 2007). On the other hand, the accumulation of ROS causes damage to proteins, lipid oxidation, and mitochondrial DNA associated with the cell structure. Some studies have reported that free radicals are associated with cancer, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, and diabetes (Allan, 2002; Chopra et al., 1996; Kovacic and Jacintho, 2001; Lipinski, 2001).

Pinus densiflora belongs to the Pinaceae family, which is a wild indeciduate conifer that is widespread in Manju, Japan and Korea. This species is called the Korean red pine because of its red trunk (Korea National Arboretum). All parts of P. densiflora, such as pine needles, pine pollen, resin, bark, and pine cone, have been used in Chinese and traditional medicine. Pine cones consist of terpenes, such as α-pinene and β-pinene, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds (Jang et al., 2016; Kuk et al., 1997). These compounds have been reported to primarily show antioxidant activity, inhibitory effects on oxidative DNA damage, and anti-melanogenic activity from the organic solvent fraction (Jang et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016). In addition, the anti-bacterial effects of the essential oils in pine cone, and the purified aqueous extract of the immature cones of P. densiflora have been studied (Jeong et al., 2014; Kalemba and Kunicka, 2003).

This study examined the biological functions of green pine cones (GPCs) which were unripened pine cones with the spindle-shaped dimension (5.87 × 3.04 cm; average of 7 GPC) and were collected in July and August. The bioactive compounds were analyzed to determine the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

The green pine cones (GPCs) used in this experiment were obtained from Mount Muchuk, Gimhae, Korea in July and August. The gathered GPC were washed with tap water and cut in half. The GPCs were then freeze-dried and stored at − 18 °C until further analysis.

Organic solvent fractions

The freeze-dried GPC (10 g) was ground to a powder with a size of 100 mesh. The methanol (MeOH) extracts of GPC were prepared with 200 mL of 80% MeOH (v/v) for 12 h (repeated three times) in a shaking incubator (VS-8480; Vision Scientific, Bucheon, Korea) at 200 rpm. After filtration using Whatman No. 2 filter paper (Whatman, Brentford, UK), the filtrate was evaporated at 35 °C under reduced pressure. The material was then freeze-dried. The MeOH extracts (10 g) were dissolved in distilled water (200 mL) and partitioned sequentially with hexane, ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and n-butanol (BuOH), three times each. The all fractions were stored at − 18 °C until needed.

Strains and culture condition of microorganism

The Bacillus cereus (KCTC 1012), Staphylococcus aureus (KCTC 1928), Escherichia coli (KCTC 2593), Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (KCTC 1925; S. Typhimurium hereafter) microorganisms were purchased from Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC) for the antibacterial test. To cultivate the bacteria, a medium was prepared under suitable culture conditions using an incubator (Jisico Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). Nutrient broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich) and agar powder (Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were prepared. While cultivating the liquid culture medium in a shaking incubator, 14 mL of polypropylene round-bottomed tubes (BD Biosicences, San Joes, CA, USA) was used.

DPPH-scavenging activity

The 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay of the organic solvent extracts of GPC was performed using a slight modification of the method reported by Blois (1958). A series of the dilutions of each extract in DMSO was dissolved in water. A 60 μM DPPH solution was prepared in 95% ethanol and filtered through filter paper (Whatman No. 2). A mixture of 100 µL of the 60 μM DPPH solution and 100 µL of the diluted sample solution was incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark and shaken before measuring the decrease in absorbance at 540 nm. The inhibition ratio was calculated by the percentage of the absorbance values of the control and samples.

Trolox equivalent antioxidant activity (TEAC)

The total antioxidant activity was measured by the Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity, i.e., an ABTS (2,2′-azono-bis-3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonate) decolorization assay (Roberata et al., 1999). An ABTS radical cation solution was prepared from a reaction of 7 mM ABTS dissolved in distilled water with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate at room temperature for 12 h in the dark. The solution was diluted with 5 mM PBS (pH 7.4) and adjusted to an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. Mixtures of 990 µL of a dilution solution and 10 µL of a sample reacted for 6 min was measured at 734 nm. The ability to scavenging the ABTS radical was calculated as a percentage of the absorbance of the control and samples.

Total phenolic compounds

The total polyphenol contents were conducted using the modified Folin–Ciocalteu method (Kumaran and Karunakaran, 2007). A 50 µL sample was mixed with 500 µL of distilled water and 100 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent and left to stand for 3 min in the dark. Subsequently, 100 µL of 10% NaNO3 and 350 µL of distilled water was added with mixtures of the sample and allowed to stand at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. The absorbance at 725 nm was measured. A standard curve was produced to measure the different concentrations of caffeic acid (CAE) to obtain the total polyphenol contents.

Total flavonoid contents

The total flavonoid contents were measured using the modified Davis method (Xu et al., 2010). A 100 µL sample was mixed with 1000 µL of 90% diethylene glycol with strong vortex motion. Subsequently, a 1 N sodium hydroxide solution was added to each sample tube and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The absorbance at 420 nm was measured. A standard curve was prepared to measure the different concentrations of naringin (NAE), which represents the flavonoid compounds.

Hyaluronidase (HAase) inhibition assay

The hyaluronidase (HAase) inhibition activity was measured using the Morgan–Elson method (Elson and Morgan, 1933) through a colorimetric method measuring the quantity of N-acetylglucosamine generated from sodium hyaluronate. Each solvent extract dissolved in DMSO (100 mg/mL) was used and diluted with 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.5) for the test. A 12 µL sample diluted with 0.1 M sodium acetate and 12 µL of HAase (10 mg/mL) was mixed and incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 20 min. To activate the HAase, 12 µL of 12.5 mM calcium chloride was added and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Subsequently, 24 µL of sodium hyaluronate (6 mg/mL) was reacted with a mixture of the sample at 37 °C for 40 min. Both HAase and sodium hyaluronate are soluble in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer. After incubation, 12 µL of 0.4 N potassium tetraborate and 0.4 N NaOH were added to quench the HAase reactions.

To completely terminate the HAase activity, they were placed in boiling water for 3 min and on ice. Finally, 360 µL of a DMAB solution (0.4 g of p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde reagent in 35 mL of glacial acetic acid and 5 mL of 10 N HCl) was added to the reaction mixture with a vortex, placed in an incubating water bath of 37 °C for 20 min. All the tubes in the test were measured using a microplate reader (Tecan Sunrise, Tecan, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland) at 540 nm after the centrifugal steps for a few seconds. The percentage of the HAase inhibition activity was determined using the following equation:

Disc diffusion test

The antimicrobial activity was measured using the paper disc-agar plate method (De Beer and Sherwood, 1945). The paper-disc agar-plate method was used to assay the antibiotic substances. Microorganisms that had been subcultured three times were incubated for 12–24 h in the selected liquid broth. The number of microorganisms adjusted to a measured absorbance of 0.1 at 600 nm was spread evenly over the plates. Autoclaved paper discs, approximately 8 mm in diameter (ADVANTEC Toyo Roshi Kaisha., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), were placed on the agar plates and 50 µL of the sample dissolved in DMSO was loaded on the disc. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and the diameter of each clear zone was observed.

HPLC coupled with PDA

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to separate and identify the functional compounds in the GPC extracts. A HPLC system (iLC3000, Interface Engineering Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) with a photodiode array detector (PDA) was used. Chromatographic separation was carried out using a YMC-Triart C18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm) column from YMC (YMC Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (Solvent A) and acetonitrile (Solvent B). To analyze the BuOH fraction, gradient conditions were as follows: 0–20 min 10 → 20% B, 20–40 min 20 → 100% B, 40–60 min 100% B, and total run time 60 min. The column was equilibrated for 10 min prior to analysis at room temperature. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min and 20 µL of the sample was injected. The compounds separated by chromatography was detected by PDA (S 3210, BMS Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). Data acquisition and preprocessing was performed using Clarity™ chromatography software (DataApex, Prague, The Czech Republic). Extracts of the analysis were dissolved in MeOH and filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter.

Isolation of active compounds of preparative HPLC

Multiple preparative HPLC (LC-forte/R, YMC Co., Kyoto, Japan) was used to fraction the functional compounds in the BuOH fraction. This was carried out using a YMC-Triart Prep C18-S (250 × 10.0 mm, 10 μm; YMC Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (Solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in water (Solvent B). The gradient conditions of the BuOH fraction were as follows: 0–15 min 10 → 20% A, 15–25 min 20 → 30% A, 25–40 min 30% A, and 40–50 min 30 → 100% A. In the case of EtOAC fraction, the gradient conditions were as follows: 0–10 min 20% A, 10–30 min 20 → 40% A, 30–40 min 40 → 100% A, and 40–60 min 100% A. The column was equilibrated for 10 min before each analysis at room temperature. The flow rate was 4.7 mL/min and 100 µL of the sample was injected.

LC–MS analysis

Liquid chromatograph was carried out using ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 µm) column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Mass spectrometric detection was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany), which was coupled to a hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer (TripleTOF 4600; AB Sciex Pte. Ltd., Framingham, MA, USA). Source parameters were gas temperature 300 °C, gas flow 9 L/min, nebulizer pressure 45 psig, sheath gas temperature 350 °C, sheath gas flow 11 L/min, and negative mode ([M–H]− ions). Scan Source parameters were VCap 4000 V and fragmentor voltage 175 V.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed statistically by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of SPSS for Windows ver. 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean ± standard deviation (SD) was measured using a Duncan’s multiple range test, and p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and discussion

Green pine cone (GPC) extracts

Organic solvent extraction was introduced to examine the various biological activities of GPC. Initially, 80% MeOH extracts were partitioned sequentially in hexane, EtOAC, BuOH, and water fractions. This allowed the separation of hydrophobic compounds and hydrophilic compounds. The yields of the 80% MeOH extract was 38–65%. The extraction yields of hexane, EtOAc, BuOH, and water were 8.30, 11.28, 27.18, and 33.70%, respectively. The extraction yield of GPC was higher in the hydrophilic compounds than the hydrophobic compounds.

Biological activities of GPC

Antioxidant activity

An antioxidant is a free radical scavenger that indicates the antioxidant activity in plants and human aging. The antioxidant activities of GPC were measured using the DPPH radical scavenging activity and the TEAC. As shown in Table 1, the hexane, EtOAc, BuOH, and water extracts showed 43.34, 70.19, 78.22, and 42.07% DPPH radical scavenging activity. The BuOH extracts had the highest radical scavenging activity, which was similar to the results for Rubus coreanus Miquel and Suaeda japonica (Cho et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2009). The TEAC is measured by suppressing or eliminating the ABTS radical and is applicable to measurements of lipophilic or hydrophilic antioxidant compounds (Roberata et al., 1999). Similarly, the results of DPPH-scavenging, and BuOH fractions also showed significantly higher antioxidant activity than the other extracts under a concentration of 10 µg/mL.

Table 1.

Antioxidant activity and hyaluronidase inhibition of the organic solvent extracts of green pine cone (GPC)

| Extracts | DPPH scavenging activity (%)1 | Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC; %)2 | Hyaluronidase inhibition (%)3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80% MeOH | 43.34 ± 2.85c | 41.50 ± 0.67c | 45.15 ± 1.85c |

| Hexane | 20.30 ± 2.56d | 2.38 ± 0.61e | 20.68 ± 0.47d |

| EtOAc | 70.19 ± 4.11b | 49.27 ± 0.23b | 49.81 ± 1.59b |

| BuOH | 78.22 ± 0.60a | 53.55 ± 1.12a | 71.50 ± 1.25a |

| Water | 42.07 ± 4.15c | 24.94 ± 0.38d | 8.45 ± 1.72e |

| l-Ascorbic acid | 70.93 ± 0.85 |

Values are mean ± SD

1100 μg/mL of sample was used

210 μg/mL of sample was used

31 mg/mL of sample was used

a–eValues with different extracts are significantly different according to the equal variances assumed from a Duncan’s multiple test (p < 0.05)

Hyaluronidase (HAase) inhibition assay

The HAase inhibition activity of the organic solvent extracts of GPC were evaluated at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. As listed in Table 1, the BuOH extracts of GPC showed the highest HAase inhibition, 71.50%, whereas the water extracts of GPC showed the lowest HAase inhibition, 8.45%. HAase is involved in inflammation, cancer metastasis, and permeability of the vascular system. Therefore, modulation of HAase inhibition will be useful for maintaining the normal homeostasis in the body (Girish and Kemparaju, 2007; Vincent and Lenormand, 2009). Accordingly, an evaluation of HAase inhibition could be considered a useful method for identifying the anti-inflammatory activity during the screening of biological active compounds.

Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial effects of organic solvent extracts were examined using the paper disc diffusion test. The BuOH extracts were more effective in indicating the clear zones than the other organic solvent extracts (Table 2). The maximal inhibitory zones for B. cereus of the BuOH, water, 80% MeOH extracts, EtOAc, and hexane fractions were 15.7, 13.0, 13.2, 11.7, and 9.8 mm at 10 mg/disc, respectively. Growth inhibitions against Staphylococcus aureus as the same gram (+) bacteria of the BuOH, EtOAc, 80% MeOH, water, and hexane fractions were 14.1, 13.7, 13.2, 10.3, and 9.5 mm at 10 mg/disc, respectively. In the gram (−) bacteria, the maximal inhibitory zones for S. Typhimurium of the BuOH, 80% MeOH, water, EtOAc, and hexane fractions were 21.3, 17.8, 17.2, and 15.8 mm at 10 mg/disc, respectively. The BuOH fraction had significantly different activity from the other fractions, but the hexane fraction with a lower growth inhibitor was evaluated by the numerical values. In the case of E. coli, the BuOH fraction also showed higher effectiveness, followed by the water and 80% MeOH extracts: 16.8, 12.1, and 11.3 mm at 10 mg/disc, respectively. This could be explained by the association with hydrophilic compounds, which have potential antimicrobial activities.

Table 2.

The results of disc diffusion test for antimicrobial activity of food poisoning microorganism

| Gram | Strains | mg/disc | 80% MeOH | Hexane | EtOAc | BuOH | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (+) | KCTC 1012* | 5 | 11.7 ± 0.2b | 9.3 ± 0.2d | 10.8 ± 0.2c | 14.2 ± 0.2a | 10.5 ± 0.4c |

| 10 | 13.2 ± 0.2b | 9.8 ± 0.2d | 11.7 ± 0.2c | 15.7 ± 0.5a | 13.0 ± 0.0b | ||

| KCTC 1928 | 5 | 11.8 ± 0.2a | 10.3 ± 0.2b | 12.1 ± 0.2a | 10.8 ± 0.2b | ND | |

| 10 | 13.2 ± 0.2c | 9.5 ± 0.0e | 13.7 ± 0.2b | 14.1 ± 0.2a | 10.3 ± 0.2d | ||

| (−) | KCTC 1925 | 5 | 14.7 ± 0.9b | ND | 14.8 ± 0.6b | 17.8 ± 0.6a | 14.5 ± 0.4b |

| 10 | 17.8 ± 0.9b | 13.5 ± 0.9c | 15.8 ± 0.6b | 21.3 ± 1.3a | 17.2 ± 1.0b | ||

| KCTC 2593 | 5 | ND1 | ND | ND | 11.8 ± 0.2 | ND | |

| 10 | 11.3 ± 0.2b | ND | ND | 16.8 ± 0.9a | 12.1 ± 0.8b |

Values are mean ± SD

1Not detected

a–eValues with different extracts are significantly different by equal variances assumed Ducan’s multiple test (p < 0.05)

*KCTC 1012 (Bacillus cereus), KCTC 1928 (Staphylococcus aureus), KCTC 1925 (Salmonella typhimurium), KCTC 2593 (Escherichia coli)

Total phenolic compounds and flavonoid contents

The BuOH and EtOAc extracts of GPC showed higher biological activities, such antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities, among the organic solvents extracts. In these situations, phenolic and/or flavonoid compounds could be candidates for the biological activity of GPC. As shown in Table 3, the total phenolic compounds in the BuOH extract had higher contents of 296.75 mg/g CAE than the other extracts, showing 237.86 and 222.86 mg/g CAE in the hexane and EtOAc extracts, respectively. In the case of the total flavonoid contents, the EtOAc fraction had a higher NAE content of 44.32 mg/g. The 80% MeOH, BuOH, and water extracts were 30.98, 26.07, and 17.12 mg/g NAE, respectively. On the other hand, flavonoid compounds were not detected in the hexane extract. The phenolic compounds and flavonoids of the fruit, vegetables and plant extracts were reported to have free radical scavenging activity (Kähkönen et al., 1999; Paganga et al., 1999; Saint-Cricq et al., 1999). Various tree materials are notable sources (Strack et al., 1989). In this experiment, the phenolic compounds of the BuOH extract accounted for approximately 30% of the entire GPC BuOH extract and significantly affect the antioxidant activity, such as DPPH scavenging and TEAC.

Table 3.

Total phenolic compound and flavonoid contents of organic solvent extracts of green pine cone (GPC)

| Content (mg/g) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic compound1 | Total flavonoid compound2 | |

| 80% MeOH | 234.8 ± 10.68b | 30.98 ± 3.23b |

| Hexane | 237.86 ± 3.75b | ND3 |

| EtOAc | 222.86 ± 1.96c | 44.32 ± 0.66a |

| BuOH | 296.75 ± 1.57a | 26.07 ± 0.86c |

| Water | 153.14 ± 0.68d | 17.12 ± 0.43d |

Values are mean ± SD

1Caffeic acid was used as a standard

2Naringin was used as a standard

3Not detected

a–dValues with different extracts are significantly different by equal variances assumed Ducan’s multiple test (p < 0.05)

Isolation and identification of functional compounds

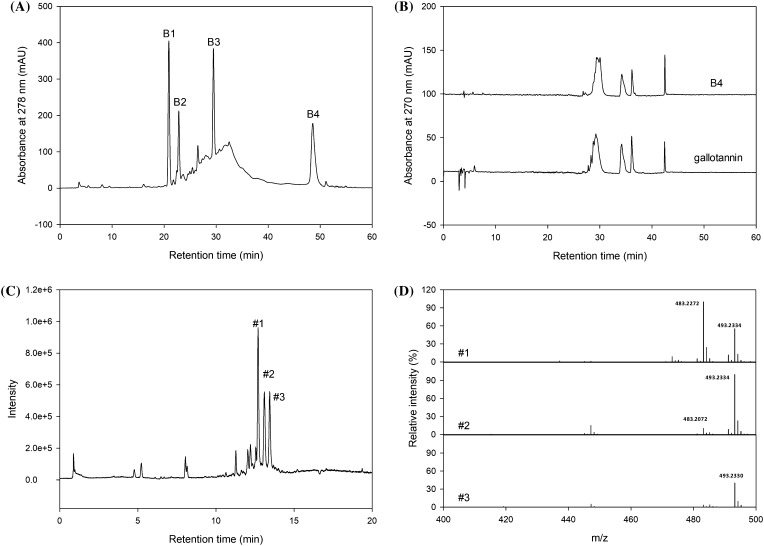

To separate the bioactive compounds, preparative HPLC was introduced to the GPC BuOH extract [Fig. 1(A)]. Four major fractions were separated and their biological activities were analyzed. The HAase inhibition activity of the B3 and B4 fractions among the four fractions (B1–B4) showed 95.95 and 90.56%, and 83.75 and 70.75% inhibition, respectively, at 1 and 0.5 mg/mL (Table 4). In the case of the DPPH radical scavenging activity, the antioxidant activity of the fractions were in the order of B4, B3, B2, and B1: 94.38, 58.43, 29.78, and 8.15%, respectively (Table 4). The B4 fraction showed the highest biological properties, such as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity among the four fractions. As shown in Fig. 1(B), B4 fraction showed similar absorption pattern and retention time with gallotannin standard. In addition, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of the B4 fraction corresponded to gallotannin, as shown in Table 4. According to LC–MS analysis, three peaks were observed in B4 fraction and their MS spectra showed major ion peaks at m/z 483.2 and 493.2 [Fig. 1(C, D)]. These ion peaks were were identified as digalloyl hexose and caffeoyl-O-hexo-galloyl moiety which could be found in fragmentation pathway of gallotannin (Sobeh et al., 2016). The most common condensed tannins occurring in plant tissues are procyanidins, which are derived from catechin or epicatechin and may contain gallic acid esters (Kähkönen et al., 1999). Condensed tannins can interact with biological systems through the induction of some physiological effects, such as antioxidant, anti-allergy, anti-hypertensive, and antimicrobial activities (Karonen et al., 2004). These compounds are enriched in pine bark, Pinus koraiensis pinecones, and grape seed extracts (Romani et al., 2006; Santos-Buelga and Scalbert, 2000). Based on the above results, the BuOH extract from green pine cone of Pinus densiflora possess various biological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activity for the functional compounds of interest. In addition, the major candidate for these interests could be tannin-related compounds.

Fig. 1.

(A) Preparative HPLC chromatogram of the GPC BuOH extracts, (B) HPLC chromatogram of the B4 fraction from GPC BuOH extracts and gallotannin, (C) LC–MS chromatographic profile of B4 fraction (C), and LC–MS spectra of three main peaks from B4 fraction (D)

Table 4.

Anti-inflammatory and DPPH scavenging activities of isolated fractions from GPC BuOH extract using preparative HPLC

| Hyaluronidase inhibition (%)2 | DPPH scavenging activity4 | |

|---|---|---|

| B1 | 7.42 ± 0.41e | 8.15 ± 0.69d |

| B2 | 65.94 ± 0.48d | 29.78 ± 0.40c |

| B3 | 95.95 ± 1.49a (64.66 ± 0.50c)3 | 58.43 ± 1.05b |

| B4 | 90.56 ± 0.24b (83.75 ± 0.25a)3 | 94.38 ± 2.87a |

| Gallotannin1 | 87.99 ± 0.25c (70.50 ± 0.25b)3 | 100 ± 1.19 |

Values are mean ± SD

1Positive control

21 mg/mL of sample was used

30.5 mg/mL of sample was used

410 µg/mL of sample was used

a–dValues with different extracts are significantly different by equal variances assumed Ducan’s multiple test (p < 0.05)

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Allan Butterfield D. Amyloid β-peptide (1-42)-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease brain. A review. Free Radical Res. 2002;36:1307–1313. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000049890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolami CN, Donoff RB. Hyaluronidase activity during open wound healing in rabbits: a preliminary report. J. Surg. Res. 1978;25:256–259. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(78)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181:1199–1200. doi: 10.1038/1811199a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borchard K, Puy R, Nixon R. Hyaluronidase allergy: a rare cause of periorbital inflammation. Australas J. Dermatol. 2010;51:49–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho WG, Han SK, Sin JH, Lee JW. Antioxidant of heating pork and antioxidative activities of Rubus coreanus Miq. extracts. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008;37:820–825. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2008.37.7.820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JI, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Song BS, Yoon YH, Byun MW, Lee JW. Antioxidant activities of the extract fractions from Suaeda japonica. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009;38:131–135. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2009.38.2.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra M., McLoone U., O'Neill M., Williams N., Thurnham D.I. Natural Antioxidants and Food Quality in Atherosclerosis and Cancer Prevention. 1996. FRUIT AND VEGETABLE SUPPLEMENTATION - EFFECT ON EX VIVO LDL OXIDATION IN HUMANS; pp. 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- De Beer EJ, Sherwood MB. The paper-disc agar-plate method for the assay of antibiotic substances. J. bacteriol. 1945;50:459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devasagayam TPA, Tilak JC, Boloor KK, Sane KS, Ghaskadbi SS, Lele RD. Free radicals and antioxidants in human health: current status and future prospects. J. Assoc. Physicians India. 2004;52:794–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson LA, Morgan WTJ. A colorimetric method for the determination of glucosamine and chondrosamine. Biochem. J. 1933;27:1824. doi: 10.1042/bj0271824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero-Miliani L, Nielsen OH, Andersen PS, Girardin SE. Chronic inflammation: importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in interleukin-1β generation. Clinic. Exp. Immunol. 2007;147:227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girish KS, Kemparaju K. The magic glue hyaluronan and its eraser hyaluronidase: a biological overview. Life Sci. 2007;80:1921–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang TW, Nam SH, Park JH. Antioxidant activity and inhibitory effect on oxidative DNA damage of ethyl acetate fractions extracted from cone of red pine (Pinus densiflora) Korean J. Plant Resour. 2016;29:163–170. doi: 10.7732/kjpr.2016.29.2.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong KH, Hwang IS, Kim JE, Lee YJ, Kwak MH, Lee YH, Jung YJ. Anti-bacterial effects of aqueous extract purified from the immature cone of red pine (Pinus densiflora) Textile Color. Finish. 2014;26:45–52. doi: 10.5764/TCF.2014.26.1.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kähkönen MP, Hopia AI, Vuorela HJ, Rauha JP, Pihlaja K, Kujala TS, Heinonen M. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1999;47:3954–3962. doi: 10.1021/jf990146l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalemba DAAK, Kunicka A. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of essential oils. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:813–829. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karonen M, Loponen J, Ossipov V, Pihlasja K. Analysis of procyanidins in pine bark with reversed-phase and normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometr. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2004;522:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2004.06.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic P, Jacintho JD. Mechanisms of carcinogenesis focus on oxidative stress and electron transfer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001;8:773–796. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk JH, Ma SJ, Park KH. Isolation and characterization of benzoic acid with antimicrobial activity from needle of Pinus densiflora. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 1997;29:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran A, Karunakaran RJ. In vitro antioxidant activities of methanol extracts of five Phyllanthus species from India. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007;40:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2005.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent TC, Fraser JR. Hyaluronan. FASEB J. 1992;6:2397–2404. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.7.1563592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AR, Roh SS, Lee ES, Min YH. Anti-oxidant and anti-melanogenic activity of the methanol extract of pine cone. Asian J. Beauty Cosmetol. 2016;14:301–308. doi: 10.20402/ajbc.2016.0055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski B. Pathophysiology of oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes. Complicat. 2001;15:203–210. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(01)00143-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. The biological significance of hyaluronic acid and hyaluronidase. Physiol. Rev. 1947;27:335–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1947.27.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller FL, Lustgarten MS, Jang Y, Richardson A, Van Remmen H. Trends in oxidative aging theories. Free Radical Bio. Med. 2007;43:477–503. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganga G, Miller N, Rice-Evans CA. The polyphenolic content of fruit and vegetables and their antioxidant activities. What does a serving constitute? Free Radical. Res. 1999;30:153–162. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberata RE, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free radical Bio. Med. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A, Ieri F, Turchetti B, Mulinacci N, Vincieri FF, Buzzini P. Analysis of condensed and hydrolysable tannins from commercial plant extracts. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006;41:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Cricq, Provost C, Vivas N. Comparative study of polyphenol scavenging activities assessed by different methods. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1999;47:425–431. doi: 10.1021/jf980700b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Buelga C, Scalbert A. Optimization of Purification, Identification and Evaluation of the in Vitro Antitumor Activity of Polyphenols from Pinus koraiensis pinecones. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000;80:1094–1117. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(20000515)80:7<1094::AID-JSFA569>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobeh M, ElHawary E, Peixoto H, Labib R, Handoussa H, Swilam N, El-Khatib AH, Sharapov F, Mohamed T, Krstin S, Linscheid MW, Singab AN, Wink M, Ayoub N. Identification of phenolic secondary metabolites from Schotia brachypetala Sond. (Fabaceae) and demonstration of their antioxidant activities in Caenorhabditis elegans. Peer J. 4: e2404 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Strack D, Heilemann J, Wray V, Dirks H. Structures and accumulation patterns of soluble and insoluble phenolics from Norway spruce needles. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:2071–2078. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97922-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JC, Lenormand H. How hyaluronan-protein complexes modulate the hyaluronidase activity: the model. Biophys. Chem. 2009;145:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ML, Hu JH, Wang L, Kim HS, Jin CW, Cho DH. Antioxidant and anti-diabetes activity of extracts from Machilus thunbergii S. et Z. Korean J. Med. Crop Sci. 2010;18:34–39. [Google Scholar]