Abstract

This study evaluated the pH effect on the lipid oxidation and polyphenols of the emulsions consisting of soybean oil, citric acid buffer (pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0), and peppermint (Mentha piperita) extract (400 mg/kg), with/without FeSO4. The emulsions in tightly-sealed bottles were placed at 25 °C in the dark, and lipid oxidation and polyphenol contents and composition were determined. The lipid oxidation was high in the emulsions at pH 4.0 in the absence of iron, however, iron addition made them more stable than the emulsions at pH 2.6 or 6.0. Total polyphenols were remained at the lowest content during oxidation in the emulsions at pH 4.0, and iron reduced and decelerated polyphenol degradation. The results strongly suggest that polyphenols contributed to decreased lipid oxidation of the emulsion via radical scavenging and iron-chelation, and rosmarinic acid along with catechin, caffeic acid, and luteolin were key polyphenols as radical scavengers in the extract.

Keywords: Emulsion lipid, Peppermint extract, Iron, Polyphenol, pH

Introduction

Salad dressing is an emulsion food in which the oil and vinegar maintain a stable system by an emulsifier such as egg yolk. Some prooxidative metals such as iron can be present in egg yolk, however, antioxidative food materials such as herbs are often added to the salad dressing. Peppermint (Mentha piperita) is a perennial herb that has excellent taste and flavor, and its ethanol extract reduced the iron-catalyzed lipid oxidation of oil-in-water emulsions due to high content of polyphenols [1, 2]. In a strictly chemical sense, polyphenols should have at least two independent phenolic moieties. However, monophenolics such as caffeic acid are often the biogenetic precursors of polyphenols, and thus monophenolics are usually included in polyphenols when evaluating the antioxidant activity of herbs in the emulsion [3].

Polyphenols can decrease lipid oxidation by engaging in reactions such as ionization, oxidations, aromatic transformations, and formation of metal complexes, depending on the structure [4, 5]. On the other hand, they can reduce Fe3+ to more active prooxidant Fe2+ which decomposes peroxides into free radicals [6]. This may partly explain the reason why different herbs whose polyphenol composition differs show different antioxidant activity. In addition, the stability of polyphenols may be dependent on the pH, although it was not still settled yet. Zoric et al. [7] reported lower stability of rosmarinic acid at pH 7.5 than at pH 2.5, however, the opposite result was also reported [8]. The antioxidant activity of the ethanol extracts of mint leaves (Mentha spicata) and carrot tuber (Daucus carota) was higher at pH 9 than pH 4, while that of drumstick (Moringa oleifera) extract remained the same under both pH conditions [9]. Among olive polyphenols, oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol accelerated the Fe3+-induced lipid oxidation of olive oil-in-water emulsion at pH 3.5 and 5.5 but not at pH 7.4. The 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol-elenolic acid reduced the prooxidant effect of Fe3+ at pH 3.5, 5.5, and 7.4 [10]. These studies suggest that herb extracts with different polyphenol composition show different pH-dependence in their antioxidant activity.

This study was performed to evaluate the pH effect on the lipid oxidation and polyphenol contents and composition in soybean oil-in-water emulsion with added peppermint extract during oxidation in the absence and presence of iron.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

Refined, bleached, and deodorized (RBD) soybean oil was generously provided by Samyang Corp. (Seoul, Korea), and fresh peppermint (M. piperita) was purchased from the Hwanamnongsan (Greenfarm) (Seoul, Korea). The egg yolk lecithin was purchased from Goshen Biotech (Namyangju, Korea), and the HPLC grade n-hexane, water, and methanol were purchased from Samchun Chemical Co. (Seoul, Korea). Isopropanol and ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) were purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker Co. (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) and Junsei Co. (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Folin–Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, cumene hydroperoxide (CuOOH), p-anisidine, xanthan gum, ammonium thiocyanate, and standard polyphenols (danshensu, rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, catechin, luteolin, luteolin-rutinoside, salvianolic acid B, and isosalvianolic acid A) were purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Saint Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Preparation of peppermint extract

Fresh peppermint was freeze-dried at − 50 °C and 5 mtorr for 24 h using a TFD5505 freeze dryer (Ilshinbiobase, Dongducheon, Korea), and ground in an Essence HR 2084 blender (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands). It was then mixed with 75% ethanol (1:10, w/v) at 25 °C and 120 rpm for 12 h. The mixture was filtered through a Whatmann #42 paper (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK), and the solvent was evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator at 65 °C (N–N series; Eyela, Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of emulsions and oxidation

Before preparation of emulsions, RBD soybean oil was purified to remove all of the tocopherols, pigments, and metals by passing it through a glass column packed with silicic acid and aluminum oxide (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) [2]. The oil-in-water emulsion was prepared with purified soybean oil (40 g), citrate buffer solution at pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0 (60 g), xanthan gum (0.35 g), and egg yolk lecithin (0.35 mg) [2]. The peppermint extract was added to the buffer solution to have a concentration of 400 mg/kg emulsion, and ferrous sulfate (5 mg/kg) was added to some of samples. Soybean oil and egg yolk lecithin were slowly added to the water-soluble ingredients, and then homogenized using an Ultra-Turrax T25 homogenizer (IKA Instruments, Staufen, Germany) at 10,000 rpm for 6 min.

The emulsion (7 g) was transferred into 20 mL serum bottles, which were then tightly capped with Teflon-coated septa (Cronus, Glocester, England) and aluminum caps. All samples were placed in an LBI-250 incubator (Daihan Labtech Co., Seoul, Korea) at 25 °C for 6 days in the dark. Light was excluded throughout the experiment for all experiments.

Analysis of polyphenols in peppermint extract and the emulsion

Total contents of polyphenols in the peppermint extract and the emulsions were determined by Folin–Ciocalteu method [2]. In the case of emulsions, the emulsion was dissolved in hexane and then mixed with methanol–water mixture (3:2, v/v), followed by centrifugation (Avanti J; Beckman Co.) at 4 °C and 11,872×g for 20 min. The Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was added to aqueous layer and the absorbance was read at 725 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2700, Shimadzu Corp.). Total polyphenol content was expressed as a rosmarinic acid equivalent with a calibration curve (r2 = 0.9914). Polyphenol composition was determined using a YL 9100 HPLC (Younglin Instrument Co., Ltd., Anyang, Korea) equipped with a UV detector (280 nm), YL 9150 autosampler, and symmetric C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm; Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). The mobile phase was a mixture of 2.5% formic acid and methanol in a gradient system of 5% (0 min), 30% (15 min), 40% (40 min), 50% (60 min), 55% (65 min), and 100% (90–95 min) on methanol basis at 0.8 mL/min [2]. Each compound was identified by comparing retention times with those of standard polyphenols and quantified with peak areas in electronic unit (eu).

Analysis of lipid oxidation of the emulsions

Lipid oxidation of the emulsion was evaluated based on the hydroperoxide and p-anisidine values. The hydroperoxide content of the emulsion was determined using the ferric thiocyanate method [2]. The emulsion was mixed with a solution of isooctane and 2-propanol (3:1, v/v), followed by centrifugation (Combi 514R; Hanil Science Industrial, Incheon, Korea) at 1000×g for 2 min. A mixture of methanol and chloroform (2:1, v/v), 3.94 M ammonium thiocyanate solution, and 0.132 M BaCl2 and 0.144 M FeSO4 solution were subsequently added to the organic layer. After 20 min, the absorbance was read at 510 nm using an HP8453 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2700, Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) and the hydroperoxide content was expressed as CuOOH using a calibration curve (r2 = 0.9988). To determine the p-anisidine value, the emulsion was dissolved in isooctane, followed by centrifugation (Avanti J; Beckman Co., Fullerton, CA, USA) at 11,949×g and 4 °C for 20 min. The anisidine reagent was mixed with the organic layer, followed by absorbance reading at 350 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2700, Shimadzu Corp.) [11].

Statistical analysis

All samples were prepared in duplicates, and each sample was measured twice. Data were statistically analyzed using SAS/PC (SAS 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) including regression analyses and Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of 5% as well as determination of means and standard deviations.

Results and discussion

Polyphenol content and composition of peppermint extract

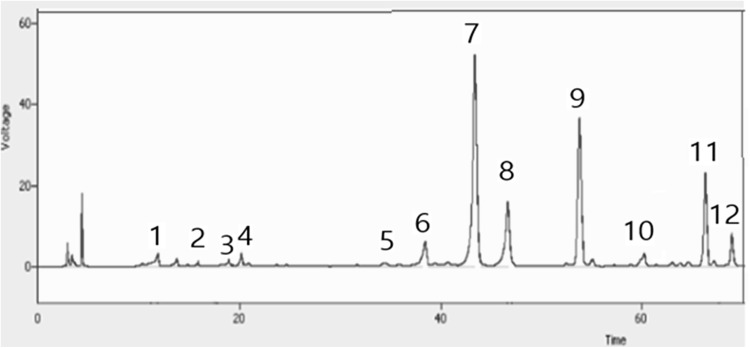

The yield of peppermint extract from freeze-dried peppermint was 17.31 ± 0.26%. Total content of polyphenols in the peppermint extract, determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method, was 168.98 ± 3.44 g/kg. Among polyphenols identified, rosmarinic acid (35.94%), isosalvianolic acid A (24.21%), and salvianolic acid B (11.92%) were predominant, and danshensu, catechin, caffeic acid, luteolin-rutinoside, and luteolin were also detected at < 5% (Fig. 1). Peppermint (M. piperita) has been reported to contain phenolic acids such as rosmarinic and caffeic acid and flavonoids such as luteolin with their derivatives [12, 13], and polyphenol composition of herbs was largely dependent on the extracting solvent [14].

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatogram of polyphenols of 75% ethanol extract of peppermint (1; danshensu, 2; catechin, 3; unidentified, 4: caffeic acid, 5; luteolin-rutinoside, 6; unidentified, 7; rosmarinic acid, 8; salvianolic acid B, 9; isosalvianolic acid A, 10; luteolin, 11, 12; unidentified)

Lipid oxidation of emulsions

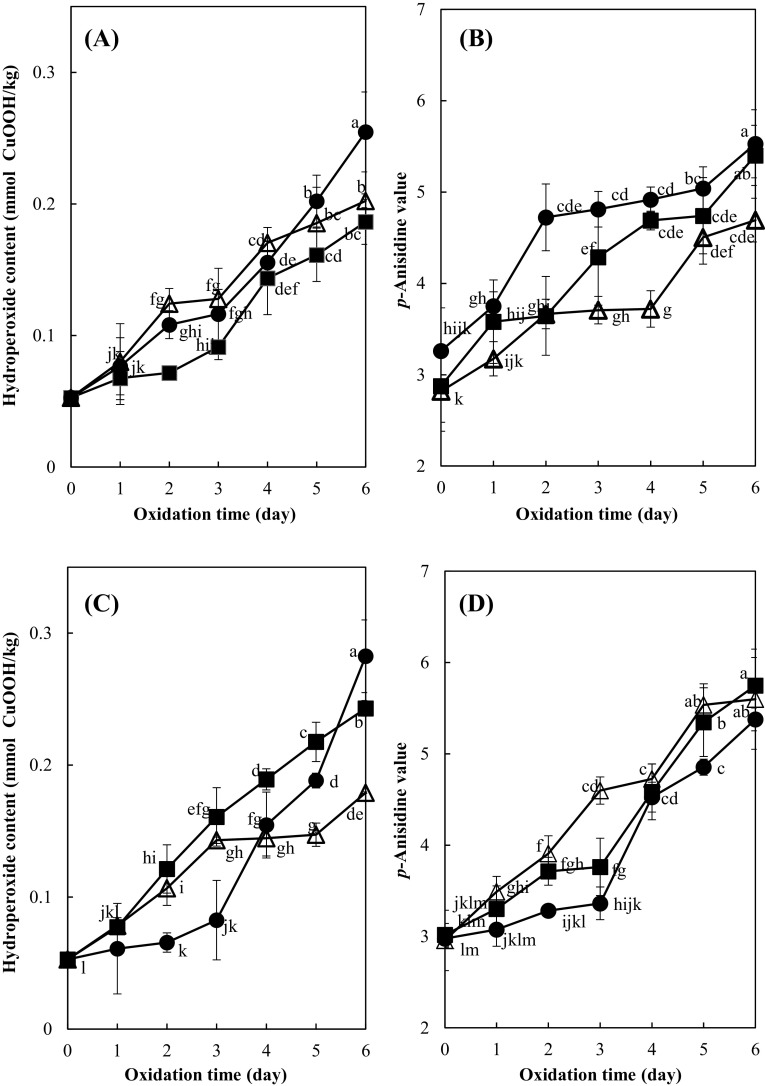

Degree of lipid oxidation, based on the hydroperoxide contents and p-anisidine values, of the soybean oil-in-water emulsion at the pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0 with added peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) without iron during oxidation at 25 °C in the dark is shown in Fig. 2(A), (B). The hydroperoxide content of the emulsions at pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0 without iron but with added peppermint extract were 0.05 mmol/kg before oxidation and significantly increased during oxidation due to hydroperoxide production (p < 0.05); 0.19, 0.25, and 0.20 mmol/kg, respectively, after 6 days. The emulsions at pH 2.6 tended to show lower hydroperoxide contents than the emulsions at pH 4.0 and 6.0 which showed no significant differences each other (p > 0.05). The p-anisidine values of the emulsions at pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0 without iron but with added peppermint extract were also significantly increased during oxidation (p < 0.05) due to aldehyde production upon hydroperoxide decomposition. The p-anisidine values tended to be higher in the emulsions at pH 4.0 than at pH 2.6 or 6.0. The results indicated that the lipid oxidation of the peppermint extract-added emulsion was dependent on the pH. Overall, there was a tendency that the emulsions at pH 4.0 showed higher hydroperoxide production and decomposition. This could be related to the pH effect on the polyphenols of the peppermint extract added to the emulsions. It was reported that apple polyphenols were stable at pH 5.0 [15]. The antioxidant activity of antioxidants is affected by hydrogen-donating ability, relative stability, and distribution in emulsions which were dependent on the pH; α-tocopherol and trolox in Tween 20 solutions were the most stable at pH 3 and the least stable at pH 7 [16]. Free forms of catechin were more stable at pH 4.0–5.0 than pH 6.0 [17].

Fig. 2.

Effect of pH on the lipid oxidation of soybean oil-in-water emulsion (4:6, w/w) with added peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) during oxidation at 25 °C in the dark (A), (B); No iron (C), (D); with iron (filled square; pH 2.6, filled circle; pH 4.0, triangle; pH 6.0). Different letters on the line are significantly different values among samples by Duncan’s multiple range test at 5%

The hydroperoxide and p-anisidine values of the soybean oil-in-water emulsions with added both iron (5 mg/kg) and peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) during oxidation at 25 °C for 6 days in the dark showed a very similar pattern with time to those of the emulsions without iron [Fig. 2(C), (D)]. The hydroperoxide content of the emulsions with added both iron and peppermint extract were significantly increased from 0.05 mmol/kg to 0.24, 0.28, and 0.18 mmol/kg after 6 days at pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0, respectively (p < 0.05). It is interesting that hydroperoxide contents were significantly lower in the emulsions at pH 4.0 (p < 0.05) than the emulsions at pH 2.6 or 6.0 up to 3 days in the presence of iron, however, they were more rapidly increased with time after 3 days. There was a tendency of higher hydroperoxide production in the emulsions at pH 2.6 than pH 4.0 or 6.0 in the presence of iron, meaning that the iron-catalyzed lipid oxidation was higher in the highly acidic emulsion. This could be due to higher solubility of Fe2+ [18] and its lower degree of oxidation to less prooxidative Fe3+ at low pH [19], resulting in higher lipid oxidation at pH 2.6. It was reported that the antioxidant activity of the mint leaves (Mentha spicata) in the iron-induced oxidation of linoleic acid was higher at pH 9.0 than at pH 4.0 [9]. The emulsions at pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0 with added both iron and peppermint extract showed a significant increase in p-anisidine values with time (p < 0.05); 5.75, 5.38, and 5.60, respectively, after 6 days. The p-anisidine values tended to be lower in the emulsions at pH 4.0 than in the emulsions at pH 2.6 and 6.0 which were not significanlty different (p > 0.05). This indicates that the lipid was more stable at pH 4.0 than pH 2.6 or 6.0 in the emulsions containing iron (II). The overall results suggest that the pH dependence of the lipid oxidation in the emulsion was affected by the iron presence. Further study on the detailed interaction among pH, polyphenols, and iron is required.

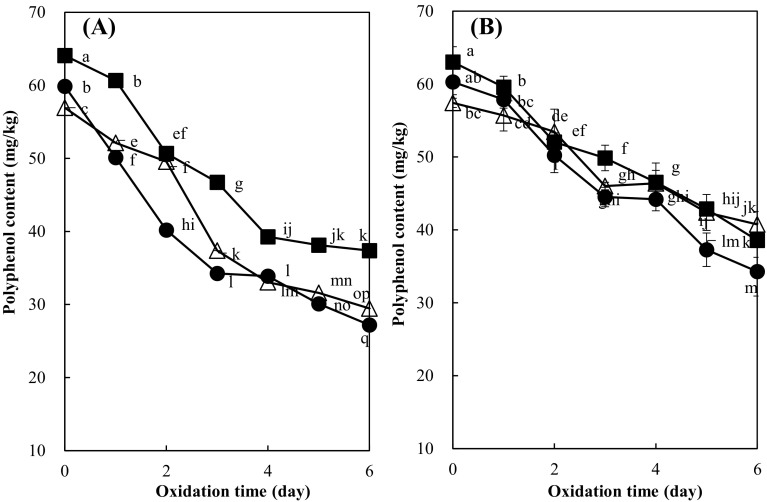

Polyphenol contents of emulsions

Polyphenols in the emulsions were derived from the peppermint extract since soybean oil and other ingredients did not contain any polyphenols (data not shown). Polyphenol content of the emulsions at pH 2.6, 4.0, or 6.0 without iron but only with added peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) was 64.10, 59.87, and 56.93 mg/kg, respectively, before oxidation and 6 days oxidation significantly decreased (p < 0.05) the content to 37.39, 27.20, and 29.47 mg/kg which was 58.33, 45.43, and 51.77% of the initial level, respectively [Fig. 3(A)]. These results clearly indicate degradation of polyphenols during the emulsion oxidation. Polyphenols were remained at lower level in the emulsions without iron addition at pH 4.0 than at pH 2.6 or 6.0, which was a similar pH dependence of hydroperoxide production and decomposition. This result suggests that higher lipid oxidation in the emulsions at pH 4.0 could be resulted from significantly lower level of polyphenols in the emulsions than at pH 2.6 or 6.0 in the absence of iron (p < 0.05). In the emulsions with added both iron and peppermint extract, polyphenol content decreased to 61.20% (38.58 mg/kg), 56.86% (34.28 mg/kg), and 70.99% (40.76 mg/kg) of the initial level after 6 days at pH 2.6, 4.0, and 6.0, respectively [Fig. 3(B)]. It is interesting that iron addition reduced polyphenol degradation in the emulsion. This provides a possibility that polyphenols act as antioxidant less chemically in the presence of iron than in its absence. Polyphenols scavenge radicals by donation of phenolic hydrogens to the radicals, resulting in their degradation to quinones [20]. When polyphenols form a complex with iron without their oxidation, radical production is reduced and their degradation can be subsequently decreased. The hydroxyl and carboxyl oxygen in polyphenols confer good metal-chelating properties [21]. The effectiveness of metal chelation by polyphenols in emulsions is dependent on the steric relationship of the hydroxyl groups and their arrangement on the ring(s), as well as lipid/hydrophilic phase partitioning; polyphenols with an ortho-dihydroxy substituted arrangement are the most effective in binding metals [22]. Although total polyphenol content of the emulsions at pH 2.6 was significantly higher than at pH 4.0 (p < 0.05), there was no significant difference in total polyphenol contents between the emulsions at pH 2.6 and 6.0 or between pH 6.0 and 4.0. These results suggest that polyphenol degradatin was less affected by the pH in the iron presence than in its absence.

Fig. 3.

Effect of pH on the polyphenol content of soybean oil-in-water emulsion (4:6, w/w) with added peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) during oxidation at 25 °C in the dark (A) without or (B) with added iron at 5 mg/kg (filled square; pH 2.6, filled circle; pH 4.0, triangle; pH 6.0). Different letters on the line are significantly different values among samples by Duncan’s multiple range test at 5%

Polyphenol degradation during 6 day oxidation of the emulsion showed high correlations with time (r2 > 0.90) as shown in Table 1. The rate of polyphenol degradation in the emulsions without iron but only with added peppermint extract at pH 2.6, 4.0, and 6.0 was 4.882, 5.155, and 4.998 mg/kg/day, respectively, and the rates were not significantly different (p > 0.05). Considering the antioxidant mechanism by peppermint extract in the emulsion without iron, the results indicate that the rate of radical scavenging by the peppermint extract, specifically polyphenols, was not dependent on the pH of the emulsion without iron. On the other hand, addition of iron to the emulsion significantly (p < 0.05) decreased or tended to decrease the polyphenol degradation rate to 4.009, 4.475, and 2.988 mg/kg/day at pH 2.6, 4.0, and 6.0, respectively. These results indicate that the iron decelerated polyphenol degradation, and suggest that the polyphenols in the peppermint extract might be less participating in radical scavenging than iron chelation in decreasing lipid oxidation of the emulsion containing iron (Fe2+). When polyphenols are bound to iron, they lower its reduction potential for the oxidation; Fe2+-polyphenol complex is rapidly autooxidized to Fe3+-polyphenol complex in the presence of oxygen via stabilization of electron from Fe2+ or electron transfer to oxygen generating less reactive superoxide radicals [23]. Thus iron-binding by polyphenols could reduce polyphenol degradation and lipid oxidation in this soybean oil-in-water emulsion containing iron (Fe2+). The emulsions with added iron also showed significantly slower degradation of polyphenols at pH 6.0 than at pH 2.6 or 4.0 (p < 0.05). The Fe2+ is less soluble at pH 6.0 than at pH 3.0 with less effect on radical production and polyphenols [18], and thus polyphenols in this study could be more slowly degraded at pH 6.0 than at pH 2.6 or 4.0. Moreover, decreasing the pH causes a decrease in iron binding to polyphenols [24], and thus less Fe2+ could be chelated to polyphenols in the emulsions at pH 2.6 or 4.0 than at pH 6.0, resulting in higher polyphenol degradation by radicals.

Table 1.

Effect of pH on the regression analysis between time and polyphenol content of soybean oil-in-water emulsion (4:6, w/w) with added peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) during oxidation at 25 °C for 6 days in the dark without or with added iron (5 mg/kg)

| pH | Without iron | With added iron | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | r 2 | a | b | r 2 | |

| 2.6 | 4.882a(1)A(2) | 62.79 | 0.933 | 4.009aB | 62.38 | 0.983 |

| 4.0 | 5.155aA | 54.84 | 0.900 | 4.475aA | 60.38 | 0.973 |

| 6.0 | 4.998aA | 56.44 | 0.936 | 2.988bB | 57.84 | 0.951 |

(1)Polyphenol content (mg/kg) = a x oxidation time (days) + b, r2 = determination coefficient

(2)Different superscript means significantly different values among samples in the same column (a, b, c) or in the same row (A, B) by dummy regression analysis at 5%

Polyphenol composition of emulsions

Rosmarinic acid was the richest polyphenol present in the emulsion with added peppermint extract, followed by caffeic acid. Catechin, luteolin-rutinoside, salvianolic acid B, isosalvianolic acid A, and luteolin were also detected. Total peak areas of polyphenols of the emulsions with added peppermint extract but without iron addition were decreased with time, confirming polyphenol degradation during the emulsion oxdation (Table 2). Among identified polyphenols in the emulsions at pH 2.6 without iron addition but with added peppermint extract, rosmarinic acid and luteolin showed significantly reduced peak areas (p < 0.05) after 6 day oxidation, and there was no significant change in peak areas of catechin, caffeic acid, salvianolic acid B, and isosalvianolic acid A (p > 0.05). In the emulsions at pH 4.0 without iron addition, there were decreases in peak areas of catechin, caffeic acid, luteolin-rutinoside, rosmarinic acid, and salvianolic acid B after 6 days (p < 0.05), while isosalvianolic acid A and luteolin did not show significantly changed peak areas (p > 0.05). The oxidation of the emulsions at pH 6.0 without iron addition showed significantly decreased peak areas of catechin, caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, isosalvianolic acid A, and luteolin (p < 0.05). Degradation of polyphenols is related to their antioxidant action in lipid-containing foods [25], and thus significant degradation of rosmarinic acid at all pHs during oxidation of the emulsions without iron addition suggests their role as radical scavenger in reducing lipid oxidation. Thus our results on the polyphenol composition suggest that rosmarinic acid play an important role in radical-scavenging to decrease lipid oxidation in the emulsion containing peppermint extract without iron, with lower contribution of catechin, caffeic acid, and luteolin. It was reported that the DPPH radical scavenging activity of rosmarinic acid derived from the aqueous acetone extract of peppermint leaves was higher than caffeic acid [26].

Table 2.

Polyphenol compounds of emulsion of soybean oil-in-water emulsion (4:6, w/w) with added peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) without iron during oxidation at 25 °C in the dark

| pH | Day | Peak area in electronic units(1) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catechin | Unidentified 1 | Caffeic acid | Luteolin-rutinoside | Unidentified 2 | Rosmarinic acid | Salvianolic acid B | Isosalvianolic acid A | Luteolin | Unidentified 3 | Total | ||

| 2.6 | 0 | 66.56 ± 2.16 | 49.25 ± 4.30 | 105.48 ± 0.51 | 37.21 ± 0.07bc | 288.67 ± 7.37a | 348.41 ± 1.50a | 18.92 ± 1.80 | 43.89 ± 0.74 | 56.83 ± 4.29a | 45.71 ± 0.64 | 1060.94 ± 6.73 |

| 3 | 59.31 ± 4.03 | 38.96 ± 3.50 | 107.89 ± 6.42 | 28.42 ± 1.18c | 267.24 ± 2.72a | 298.19 ± 9.26b | 17.66 ± 0.64 | 39.10 ± 2.88 | 47.39 ± 1.65ab | 34.85 ± 2.76 | 939.01 ± 24.08 | |

| 6 | 54.31 ± 2.74 | 35.97 ± 0.53 | 117.17 ± 0.28 | 54.13 ± 0.67a | 253.42 ± 4.82b | 231.18 ± 8.41c | 13.17 ± 0.77 | 39.28 ± 1.01 | 46.52 ± 2.84b | 20.36 ± 1.41 | 865.52 ± 13.84 | |

| 4.0 | 0 | 62.39 ± 13.98a | 34.29 ± 1.24 | 89.59 ± 8.83a | 31.52 ± 6.82a | 253.80 ± 13.56a | 354.23 ± 11.78a | 19.06 ± 0.65a | 37.67 ± 6.39 | 51.53 ± 8.83 | 42.25 ± 5.40 | 976.34 ± 57.33 |

| 3 | 31.38 ± 0.41b | 26.09 ± 0.03 | 38.38 ± 6.65b | 24.81 ± 2.59ab | 211.92 ± 12.08b | 320.08 ± 8.92b | 12.79 ± 3.73ab | 36.52 ± 0.35 | 50.75 ± 7.94 | 37.80 ± 0.15 | 790.53 ± 36.67 | |

| 6 | 25.78 ± 4.81b | 25.57 ± 0.84 | 35.18 ± 0.01b | 22.77 ± 1.44b | 187.80 ± 11.36b | 251.60 ± 5.32c | 11.45 ± 3.73b | 36.20 ± 0.62 | 43.89 ± 4.04 | 22.58 ± 0.21 | 662.81 ± 29.50 | |

| 6.0 | 0 | 72.18 ± 4.47a | 32.35 ± 1.15 | 92.19 ± 4.20a | 30.31 ± 2.53 | 180.61 ± 8.83a | 301.40 ± 14.67a | 10.27 ± 2.25 | 41.22 ± 1.67a | 43.96 ± 1.14a | n.d(2) | 804.49 ± 15.90 |

| 3 | 52.64 ± 6.58b | 8.99 ± 0.60 | 70.19 ± 13.09b | 25.66 ± 3.85 | 157.14 ± 3.40ab | 209.96 ± 1.95b | 10.74 ± 2.21 | 32.33 ± 3.04ab | 36.79 ± 2.25b | n.d | 604.43 ± 20.57 | |

| 6 | 28.36 ± 3.56c | 9.91 ± 1.00 | 36.37 ± 0.07c | 22.61 ± 4.05 | 137.54 ± 10.63b | 171.35 ± 4.47c | 8.49 ± 0.09 | 26.27 ± 5.60b | 26.55 ± 6.01c | n.d | 467.44 ± 5.96 | |

(1)Different superscript means significantly different values among samples at the same pH in each polyphenol by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05)

(2)Not detected

The emulsions with addition of both peppermint extract and iron showed similar trend of polyphenol contents and composition to those of the emulsions without iron but with peppermint extract during oxidation (Table 3). The emulsions at pH 4.0 showed significant decrease in peak areas of catechin, luteolin-rutinoside, rosmarinic acid, and salvianolic acid B during the oxidation in the iron presence (p < 0.05), however, there was no significant change in peak areas of isosalvianolic acid A and luteolin (p > 0.05). It is interesting that caffeic acid content was increased in the emulsions at pH 6.0 during oxidation. Structurally, rosmarinic acid is an ester of caffeic acid with 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl lactic acid, and formation of caffeic acid from rosmarinic acid in oil-in water emulsions via an oxidative breakdown of rosmarinate quinone was reported [27]. However, the pH effect on the formation of caffeic acid from rosmarinic acid and metal-chelation of polyphenols with plant extract has not been yet reported, and further study is needed.

Table 3.

Polyphenol compounds of emulsion of soybean oil-in-water emulsion (4:6, w/w) with added peppermint extract (400 mg/kg) and iron (5 mg/kg) during oxidation at 25 °C in the dark

| pH | Day | Peak area in electronic units(1) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catechin | Unidentified 1 | Caffeic acid | Luteolin-rutinoside | Unidentified 2 | Rosmarinic acid | Salvianolic acid B | Isosalvianolic acid A | Luteolin | Unidentified 3 | Total | ||

| 2.6 | 0 | 85.99 ± 8.82 | 16.43 ± 5.56 | 129.89 ± 6.51 | 98.02 ± 8.94 | 458.43 ± 33.27a | 150.47 ± 43.74a | 25.15 ± 5.06a | 62.32 ± 4.61 | 67.68 ± 6.64a | 28.23 ± 1.74 | 1122.61 ± 40.72 |

| 3 | 87.56 ± 2.23 | 10.39 ± 3.17 | 126.56 ± 4.35 | 95.58 ± 10.26 | 425.61 ± 39.39b | 41.99 ± 9.40b | 15.32 ± 3.56b | 60.15 ± 0.45 | 55.61 ± 0.88b | n.d(2) | 918.77 ± 12.21 | |

| 6 | 85.67 ± 1.50 | 9.41 ± 1.71 | 118.32 ± 3.74 | 92.07 ± 3.07 | 335.61 ± 30.55c | 24.85 ± 6.33b | n.d | 60.20 ± 2.69 | 49.97 ± 1.29b | n.d | 776.11 ± 18.61 | |

| 4.0 | 0 | 35.48 ± 5.50ab | 27.90 ± 2.67 | 77.82 ± 6.45b | 59.30 ± 0.31a | 244.97 ± 1.25 | 291.42 ± 8.68a | 19.21 ± 4.51a | 38.62 ± 2.78 | 51.47 ± 2.28 | 38.30 ± 6.52 | 884.48 ± 38.44 |

| 3 | 39.26 ± 0.17a | 26.64 ± 2.46 | 108.11 ± 11.48a | 51.41 ± 5.92ab | 236.87 ± 1.77 | 272.10 ± 5.18ab | 17.82 ± 4.85ab | 34.76 ± 3.71 | 49.51 ± 3.07 | 34.78 ± 5.01 | 871.25 ± 12.22 | |

| 6 | 3.89 ± 2.35c | 9.45 ± 1.40 | 33.57 ± 9.79c | 45.42 ± 1.05b | 233.56 ± 6.48 | 214.96 ± 10.44b | 12.79 ± 0.19b | 33.28 ± 6.02 | 48.11 ± 6.21 | 31.38 ± 0.16 | 666.42 ± 39.02 | |

| 6.0 | 0 | 63.29 ± 1.29a | 28.45 ± 0.52 | 91.78 ± 0.75b | 43.58 ± 7.42a | 152.53 ± 5.66a | 346.85 ± 18.99a | 8.73 ± 0.86 | 39.58 ± 2.36a | 52.38 ± 4.05a | 10.20 ± 0.67 | 837.36 ± 8.48 |

| 3 | 20.43 ± 3.00b | 12.42 ± 1.78 | 94.84 ± 2.89b | 23.68 ± 3.10b | 137.47 ± 5.65ab | 146.57 ± 18.98b | 9.24 ± 2.83 | 38.87 ± 1.98a | 38.65 ± 4.20b | n.d | 522.18 ± 32.63 | |

| 6 | 8.40 ± 0.97c | 12.03 ± 0.79 | 167.67 ± 6.24a | 10.40 ± 3.96c | 114.78 ± 15.95b | 166.64 ± 1.69b | 9.90 ± 4.39 | 24.51 ± 2.51b | 33.42 ± 1.90b | n.d | 547.76 ± 7.16 | |

(1)Different superscript means significantly different values among samples at the same pH in each polyphenol by Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05)

(2)Not detected

In conclusion, the pH significantly affected the lipid oxidation of soybean oil-in-water emulsion (4:6, w/w) with added peppermint extract, depending on iron presence; the overall lipid oxidation was low in the emulsions at pH 4.0 in the absence of iron, however, it was more stable at pH 4.0 than at pH 2.6 or 6.0 in the presence of iron. Polyphenols derived from peppermint extract contributed to decreased lipid oxidation of the emulsion via radical scavenging and iron-chelation, and rosmarinic acid was an important radical scavenger to decrease the lipid oxidation with lower contribution of catechin, caffeic acid, and luteolin.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2015R1C1A2A01053245).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Abdalla AE, Roozen JP. Effect of plant extracts on the oxidative stability of sunflower oil and emulsion. Food Chem. 1999;64:323–329. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Choe E. Effects of selected herb extracts on iron-catalyzed lipid oxidation in soybean oil-in-water emulsion. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016;25:1017–1022. doi: 10.1007/s10068-016-0164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quideau S. Why bother with polyphenols? (2011). Groupe Polyphenols. http://www.groupepolyphenols.com/the-society/why-bother-with-polyphenols/accessed(retrieved) on July 01, 2017.

- 4.Haslam E, Cai Y. Plant polyphenols (vegetable tannins): Gallic acid metabolism. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1994;11:41–66. doi: 10.1039/np9941100041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drynan JW, Clifford MN, Obuchowicz J, Kuhnert N. The chemistry of low molecular weight black tea polyphenols. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:417–462. doi: 10.1039/b912523j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hider RC, Liu ZD, Khodr HH. Metal chelation of polyphenols. Methods Enzymol. 2001;335:190–203. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(01)35243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorić Z, Markić J, Pedisić S, Bučević-Popović V, Generalić-Mekinić I, Grebenar K, Kulišić-Bilušić T. Stability of rosmarinic acid in aqueous extracts from different Lamiaceae species after in vitro digestion with human gastrointestinal enzymes. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2016;54:97–102. doi: 10.17113/ftb.54.01.16.4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinis PC, Falé PL, Amorim Madeira PJ, Floręncio MH, Serralheiro ML. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of infusions of Mentha species. European J. Med. Plants. 2013;3:381–393. doi: 10.9734/EJMP/2013/3430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arabshahi DS, Devi DV, Urooj A. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of some plant extracts and their heat, pH and storage stability. Food Chem. 2007;100:1100–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paiva-Martins F, Gordon MH. Effects of pH and ferric ions on the antioxidant activity of olive polyphenols in oil-in-water emulsions. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2002;79:571–576. doi: 10.1007/s11746-002-0524-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AOCS. Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society. 4th ed. Method Cd 18-90. AOCS Press, Champaign, IL, USA (2006)

- 12.Guedon DJ, Pasquier BP. Analysis and distribution of flavonoid glycosides and rosmarinic acid in 40 Mentha piperita clones. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994;42:679–684. doi: 10.1021/jf00039a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadjmohammadi M, Karimiyan H, Sharifi V. Hollow fibre-based liquid phase microextraction combined with high-performance liquid chromatography for the analysis of flavonoids in Echinophora platyloba DC and Mentha piperita. Food Chem. 2013;141:731–735. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.02.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dent M, Dragovic-Uzelac V, Penic M, Brncic M, Bosiljkov T, Levaj B. The effect of extraction solvents, temperature and time on the composition and mass fraction of polyphenols in dalmatian wild sage (Salvia officinalis L.) extracts. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2013;51:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Sun H, Wang Y, Wang Sn, Tao X, Sun A. Stability of apple polyphenols as a function of temperature and pH. Intern. J. Food Prop. 2014;17:1742–1749. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2012.678531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S-W, Frankel EN, Schwarz K, German JB. Effect of pH on antioxidant activity of α-tocopherol and trolox in oil-in-water emulsions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996;44:2496–2502. doi: 10.1021/jf960262d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li N, Taylor LS, Ferruzzi MG, Mauer LJ. Kinetic study of catechin stability: Effects of pH, concentration, and temperature. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:12531–12539. doi: 10.1021/jf304116s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Casal MN, Layrisse M. The effect of change in pH on the solubility of iron bis-glycinate chelate and other iron compounds. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2001;51(Suppl 1):35–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan B, Lahav O. The effect of pH on the kinetics of spontaneous Fe(II) oxidation by O2 in aqueous solution – basic principles and a simple heuristic description. Chemosphere. 2007;68:2080–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choe E, Min DB. Mechanisms of antioxidants in the oxidation of foods. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2009;8:345–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2009.00085.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Psotová J, Lasovsky J, Vicar J. Metal-chelating properties, electrochemical behavior, scavenging and cytoprotective activities of six natural phenolics. Biomed. Papers. 2003;147:147–153. doi: 10.5507/bp.2003.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer MS. Natural antioxidants: sources, compounds, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011;10:221–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00156.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perron NR, Brumaghim JL. A review of the antioxidant mechanisms of polyphenol compounds related to iron binding. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2009;53:75–100. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perron NR, Wang HC, DeGuire SN, Jenkins M, Lawson M, Brumaghim JL. Kinetics of iron oxidation upon polyphenol binding. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:9982–9987. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00752h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Choe E. Improvement of the lipid oxidative stability of soybean oil-in water emulsion by addition of daraesoon (shoot of Actinidia arguta) and samnamul (shoot of Aruncus dioicus) extract. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017;26:113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0015-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sroka Z, Fecka I, Cisowski W. Antiradical and anti-H2O2 properties of polyphenolic compounds from an aqueous peppermint extract. Z. Naturforsch C. 2005;60:826–832. doi: 10.1515/znc-2005-11-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panya A, Kittipongpittaya K, Laguerre M, Bayrasy C, Lecomte J, Villeneuve P, McClements DJ, Decker EA. Interactions between α-tocopherol and rosmarinic acid and its alkyl esters in emulsions: synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effect? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:10320–10330. doi: 10.1021/jf302673j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]