Abstract

Resveratrol has been extracted from grape leaves by ultrasound-assisted extraction with aqueous ethanol and further concentrated on a column of mesoporous carbon. The ethanol concentration, extraction temperature, solid/liquid ratio, and extraction time have been investigated, and the extraction kinetics has been studied. After one treatment run with mesoporous carbon, the resveratrol purity was improved from 2.1 to 20.6%. The antioxidant activities of grape leaf extracts before and after concentration have been analyzed. Mesoporous carbon has been applied in the purification of resveratrol from grape leaves for the first time, and it is shown to offer a promising procedure in this field. Grape leaf is a promising material for the extraction of resveratrol, which shows antioxidant properties.

Keywords: Mesoporous carbon, Grape leaf, Resveratrol, Extraction, Purification

Introduction

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-stilbene) is a major polyphenol with many biological effects, such as combating cardiovascular disease (Szkudelska and Szkudelski, 2010), preventing cancers (Ginkel et al., 2007; Jang et al., 1997), and treating diabetes mellitus (Thirunavukkarasu et al., 2007). It can be extracted from several plants, such as Arachis hypogaea (peanut) (Xiong et al., 2014), Fallopia japonica (Japanese knotweed) (Zhang et al., 2009), and Vitis vinifera (grape) (Pascual-Martí et al., 2001). Grape is an everyday plant in China and widely known for its edible fruit. There have been numerous reports on the extraction of polyphenolic antioxidants from grape fruit, seeds, and skin (Beres et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2008; Li et al., 2011; Pascual-Martí et al., 2001; Sant’Anna et al., 2012). While these parts of the grape have been intensively examined, there have been few reports on the use of grape leaves, which are usually discarded. Making use of grape leaves would be resource-saving.

Various techniques, such as organic solvent extraction (Wang et al., 2013), ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) (Khan et al., 2010), microwave-assisted extraction (Upadhyay et al., 2012), supercritical fluid extraction (Fathordoobady et al., 2016), and high-pressure processes (Park et al., 2016), have been used to recover bioactive compounds from plant materials. Among these techniques, UAE is a common operation applied in many industrial processes. UAE shows obvious advantages in terms of high efficiency and short duration compared to the conventional solvent-extraction method.

There are many impurities in crude extracts. Purification of phenolic compounds on adsorbents is widely carried out (Kang et al., 2014). Carbon materials, including mesoporous and microporous carbons, are widely used adsorbents in the fields of environmental science, chemistry, and food (Vinu et al., 2007; Xiaoming et al., 2015). However, carbon adsorption separation has rarely been used in the purification of phenolic compounds. As the adsorption and desorption effect is partly dependent on the pore size of the adsorbent (Newcombe et al., 1997), mesoporous carbon has a better adsorption capacity towards phenolic compounds than microporous carbon. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no report on the use of mesoporous carbon to separate and recover resveratrol from grape leaves.

In this study, we have employed ethanol as a solvent to extract resveratrol from grape leaves based on UAE. The resveratrol was then recovered in high purity by work-up on a column of mesoporous carbon. The results demonstrate that grape leaves can be a good and inexpensive source of resveratrol, which shows antioxidant properties. This study may pave the way for the development of a preparative method for the separation and purification of resveratrol from grape leaf extract.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

Grape leaves were collected from Huailai (Hebei, China). Resveratrol was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Stable 2,2,-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) was procured from Alfa Aesar (Shanghai, China). Acetonitrile of chromatographic grade was purchased from Beijing Bailingwei Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Ethanol was obtained from Beijing Lanyi Chemical Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Deionized water was purified on a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Boston, USA).

Extraction of resveratrol from grape leaves

The collected fresh grape leaves were carefully washed to remove impurities. The leaves were left to dry under natural conditions, and then ground using a high-speed crusher (Beijing Yongguangming Medical Instrument Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The powder was sifted through 50 mesh and stored at − 22 °C in a freezer. The prepared grape leaf powder was extracted using aqueous ethanol solutions by UAE. Different conditions, including ethanol concentration, extraction temperature, solid/liquid ratio, and extraction time, were investigated in detail to find the optimal extraction conditions. Each process was performed in an ultrasonic bath (40 kHz, 100 W, Crest Ultrasonics Plant, Beijing, China). The slurries obtained were centrifuged (Sigma Laborzentrifugen GmbH, Osterode-am-Harz, Germany) at 4000×g for 15 min. The supernatants were stored in sealed dark bottles at 0–4 °C prior to analysis.

The resveratrol concentration was quantitatively determined by UV spectrophotometric analysis (Shanghai Mapada Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at a wavelength of 305 nm and room temperature (Lee et al., 2012).The resveratrol concentration (mg L−1) was calculated from a standard curve.

Purification of resveratrol on a column of mesoporous carbon

The resveratrol extract was purified on a column of mesoporous carbon in order to obtain a product with a high concentration of resveratrol. This process was performed on laboratory-scale glass columns (7.5 mm × 400 mm) packed with mesoporous carbon. The packed length was 100 mm. A resveratrol extract of 2 mg mL−1 was passed through the glass column at a flow rate of 2 BV h−1. Subsequently, the adsorbate-laden adsorbent in the column was washed with deionized water and then eluted with aqueous ethanol. The samples before and after purification were lyophilized in a freeze dryer (Beijing Sihuan Scientific Instrument Factory, Beijing, China) under reduced pressure and then subjected to HPLC analysis, antioxidant activity analysis, and purity analysis to investigate the purification effect.

HPLC analysis

HPLC analysis was carried out on a Waters HPLC system (Waters Co., USA). A COSMOSIL C18-PAQ packed column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 µm) was employed, and the mobile phase was acetonitrile/water (3:7, v/v). The mobile phase was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane prior to injection.

Free radical scavenging activity

Stable 2,2,-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) was used to determine the antioxidant activity (Mi et al., 2017) of the extracts. Ethanol served as a blank. A DPPH solution with no test sample (3.5 mL of DPPH plus 0.5 mL of ethanol) served as a control. DPPH solutions with various sample solutions (3.5 mL of DPPH plus 0.5 mL of sample solution) were used for the tests. The absorbance at 515 nm was measured by means of a UV spectrophotometer at room temperature. The inhibition (%) of DPPH was calculated as follows:

| 1 |

where Acontrol is the absorbance of the control, and Atest is the absorbance of the test sample.

Results and discussion

Optimization of extraction conditions

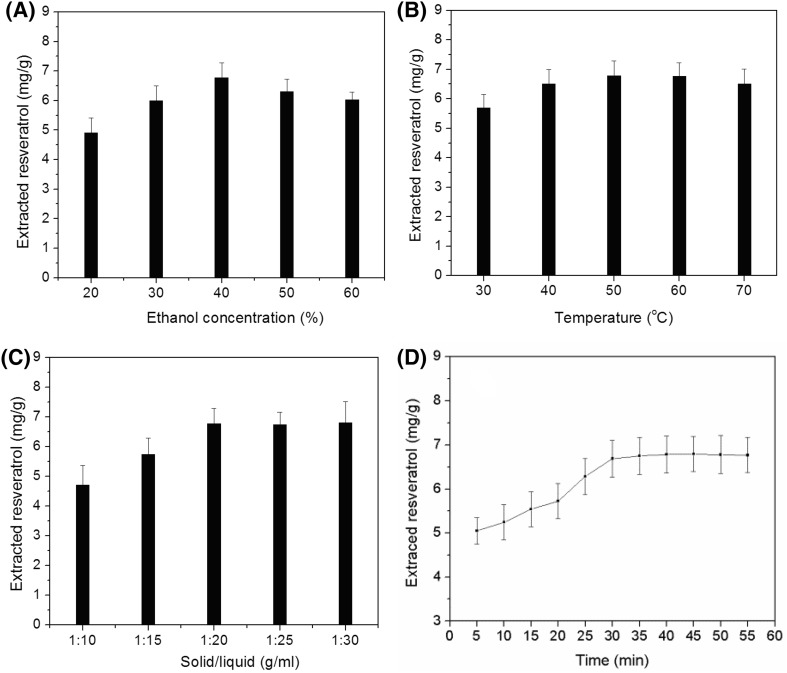

Ethanol was used as the solvent for resveratrol extraction due to its low toxicity. The amounts of resveratrol obtained under different extraction conditions [ethanol concentration, extraction temperature, solid/liquid ratio (m/v), and extraction time] were investigated. As shown in Fig. 1(A), increasing ethanol concentration led to better extraction, and 40% ethanol gave the maximum resveratrol yield. A higher ethanol concentration beyond 40% did not favor more resveratrol extraction. Therefore, 40% ethanol was identified as the optimum ethanol concentration. The extraction temperature also affects the amount of material recovered. The amounts of resveratrol obtained at different extraction temperatures are shown in Fig. 1(B). Increasing the extraction temperature increased the amount of resveratrol and the extraction yield was maximized at 50 °C. A higher temperature may result in higher solubility of resveratrol and its faster diffusion from the interior to the exterior of the leaf (Cacace and Mazza, 2003a; 2003b). The extraction yield decreased when the temperature exceeded 50 °C due to the degradation of resveratrol at higher temperatures. Figure 1(C) shows the effect of solid/liquid (m/v) ratio. The yield increased up to 1:20, but thereafter there was no significant change. Thus, 1:20 was selected as the optimum value. The effect of extraction time on the amount recovered was also investigated, and the results are shown in Fig. 1(D). When the extraction time was increased from 5 min to 30 min, the yield increased steadily. Thereafter, the yield showed little difference when the extraction time was increased to 55 min.

Fig. 1.

Resveratrol obtained at different ethanol concentrations (A), extraction temperatures (B), solid/liquid ratios (m/v) (C), and extraction times (D)

The extraction kinetics was evaluated using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models.

Pseudo-first-order model: (Trivedi et al., 1973)

| 2 |

Pseudo-second-order model: (Ho and Mckay, 1999)

| 3 |

where k1 is the rate constant of the pseudo-first-order-model, k2 is the rate constant of the pseudo-second-order-model, qt is the amount of extracted resveratrol at time t, and qe is the extracted resveratrol at equilibrium.

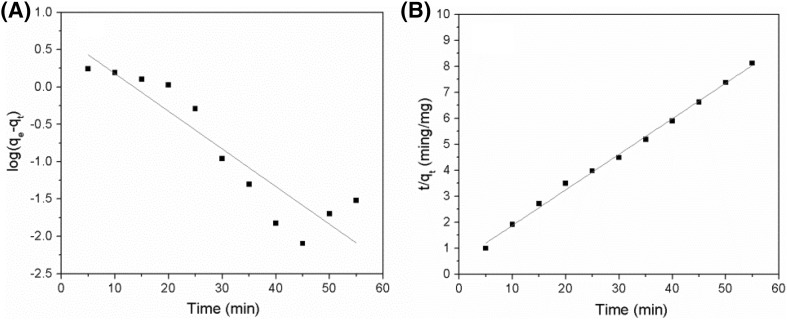

Plots of versus t and t/qt versus t are shown in Fig. 2(A) and (B), respectively. The fitting parameters for resveratrol extraction based on pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetics are listed in Table 1. A plot of versus t did not show a linear relationship, suggesting that resveratrol extraction could not be described by a pseudo-first-order kinetic model. However, a plot of t/qt versus t showed a linear relationship with R2 > 0.99. Moreover, the amount of resveratrol extracted based on experimental data (6.792 mg g−1) was close to that determined from a simulated experiment (7.353 mg g−1), further demonstrating that resveratrol extraction follows pseudo-second-order kinetics.

Fig. 2.

Simulation of resveratrol extraction using a pseudo-first-order kinetic model (A) and a pseudo-second-order kinetic model (B)

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for resveratrol extraction

|

q

e

exp (mgg−1) |

Pseudo-first-order model | Pseudo-second-order model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

k

1

(min−1) |

q

e

(mgg−1) |

R 2 |

k

2

(gmg−1min−1) |

q

e

(mgg−1) |

R 2 | |

| 6.792 | 0.116 | 4.807 | 0.926 | 0.036 | 7.353 | 0.998 |

Purification of the resveratrol extract

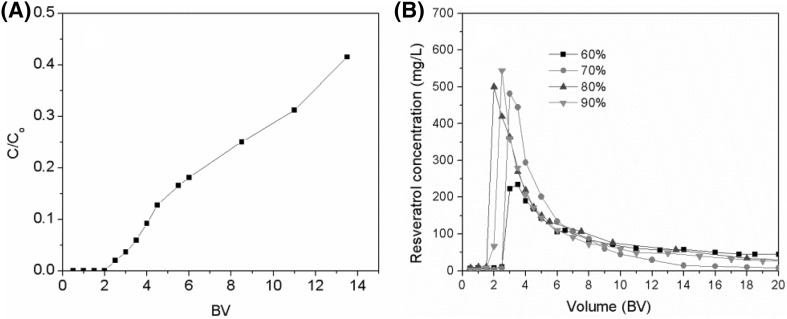

Purification of the resveratrol extract was studied on a column of mesoporous carbon. The dynamic leakage curve for resveratrol was obtained, as presented in Fig. 3(A). There was no resveratrol leakage before 2 BV. The leakage point is defined as that at which the leakage concentration is 5% of the original concentration, and here it was determined as 3.4 BV.

Fig. 3.

Dynamic leakage (A) and desorption curves (B) for resveratrol on a column of mesoporous carbon, eluting with different ethanol/water mixtures

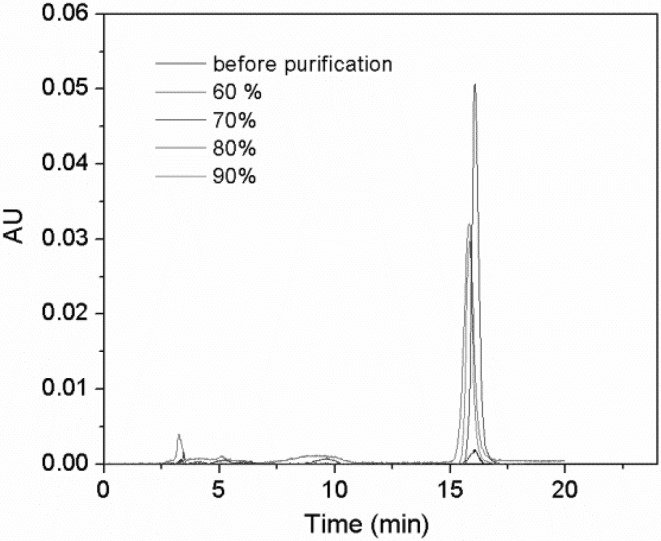

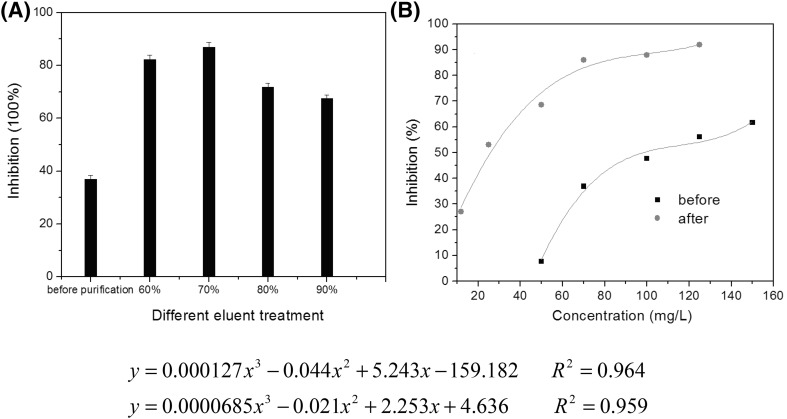

For the desorption process, 60–90% solutions of ethanol in water were applied as eluents at a flow rate of 3 BV h−1. As shown in Fig. 3(B), the concentration of resveratrol desorbed was improved when the ethanol concentration was increased from 60 to 70%. There was no further obvious increase when the concentration was increased from 70 to 90%. The degree of desorption of resveratrol was the highest with 70% ethanol. Furthermore, elution with 70% ethanol in water resulted in the lowest amount of impurities (Fig. 4) and the highest antioxidant activity [Fig. 5(A)]. Hence, 70% ethanol was identified as the optimum desorption solution.

Fig. 4.

HPLC traces of resveratrol extracts before and after purification using different ethanol/water mixtures as eluents

Fig. 5.

Radical-scavenging properties of different extracts before and after purification by elution with different ethanol/water mixtures (A) and the antioxidant activities of extracts before and after purification with 70% ethanol in water as eluent (B)

HPLC analysis

In order to validate the purification efficiencies of mesoporous carbon with different ethanol/water mixtures as eluents more directly, samples before and after purification were characterized by HPLC, and the results are shown in Fig. 4. It can be seen that the purification process removed impurities from the extracts, and therefore the relative peak areas of resveratrol increased significantly. The purity of the sample before purification was 2.1%, and this increased to 20.6% after purification with 70% ethanol as the eluent. This result is comparable with the reported value from macroporous resin (Xiong et al., 2014). Therefore, the mesoporous carbon is a promising stationary phase for the preliminary purification of resveratrol extract from grape leaves.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activities of resveratrol extracts before and after purification were determined by DPPH radical-scavenging assay. The resveratrol concentration of the samples was 80 mg L−1. As shown in Fig. 5(A), antioxidant activity increased after purification. Inhibition of DPPH was 36.9% for a sample before purification. For samples eluted with 60, 70, 80, and 90% ethanol, the corresponding inhibitions were 82.2, 87, 71.8, and 71.8%, respectively. Thus, the sample desorbed with 70% ethanol as eluent showed the highest DPPH radical scavenging.

IC50 is defined as the concentration of the antioxidant that decreases the initial amount of DPPH by 50%. Low IC50 represents a high radical-scavenging ability. IC50 was determined for grape leaf extracts based on plotted graphs of DPPH radical-scavenging activity against the concentrations of the samples [Fig. 5(B)]. The eluent was 70% ethanol. It was found that the DPPH inhibition effect of sample extracts showed a polynomial relationship to the concentration of the samples. IC50 for the sample before purification was calculated as 100 mg L−1, much higher than the value of 25 mg L−1 after purification. This indicated that the antioxidant capacity increased after purification.

In conclusion, an integrated method for the extraction and purification of resveratrol from grape leaves has been developed. Firstly, grape leaves were subjected to UAE with aqueous ethanol solutions. The maximum amount of resveratrol was obtained when the extraction was performed with 40% aqueous ethanol at 50 °C for more than 30 min. The extraction kinetics was fitted by a second-order model. A mesoporous carbon column chromatography method was then used to purify the resveratrol extract. After concentration on mesoporous carbon, eluting with 70% ethanol gave an extract in which the resveratrol purity had improved from 2.1 to 20.6%. Concomitantly, the IC50 decreased from 100 to 25 mg L−1. The results showed that grape leaf is a promising material for the extraction of resveratrol.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51772031).

References

- Beres C, Gns C, Cabezudo I, Da SJN, Asc T, Apg C, Mellinger-Silva C, Tonon RV, Lmc C, Freitas SP. Towards integral utilization of grape pomace from winemaking process: a review. Waste Manag. 2017;68:581–594. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacace JE, Mazza G. Mass transfer process during extraction of phenolic compounds from milled berries. J. Food Eng. 2003;59:379–389. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(02)00497-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacace JE, Mazza G. Optimization of extraction of anthocyanins from black currants with aqueous ethanol. J. Food Sci. 2003;68:240–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb14146.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan E, Zhang K, Jiang S, Yan C, Bai Y. Analysis of trans-resveratrol in grapes by micro-high performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Sci. 2008;24:1019–1023. doi: 10.2116/analsci.24.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathordoobady F, Mirhosseini H, Selamat J, Manap MY. Effect of solvent type and ratio on betacyanins and antioxidant activity of extracts from Hylocereus polyrhizus flesh and peel by supercritical fluid extraction and solvent extraction. Food Chem. 2016;202:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginkel PRV, Sareen D, Subramanian L, Walker Q, Darjatmoko SR, Lindstrom MJ, Kulkarni A, Albert DM, Polans AS. Resveratrol inhibits tumor growth of human neuroblastoma and mediates apoptosis by directly targeting mitochondria. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2007;13:5162–5169. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho YS, Mckay G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochemistry. 1999;34:451–465. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CWW, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997;275:218–220. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ, Jung SW, Lee SJ. An optimal extraction solvent and purification adsorbent to produce anthocyanins from black rice (Oryza sativa cv. Heugjinjubyeo) Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2014;23:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s10068-014-0013-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MK, Abert-Vian M, Fabiano-Tixier AS, Dangles O, Chemat F. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols (flavanone glycosides) from orange (Citrus sinensis L.) peel. Food Chem. 2010;119:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.08.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Thomas JL, Wang HY, Chang CC, Lin CC, Lin HY. Extraction of resveratrol from polygonum cuspidatum with magnetic orcinol-imprinted poly(ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol) composite particles and their in vitro suppression of human osteogenic sarcoma (HOS) cell line. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:24644–24651. doi: 10.1039/c2jm34244h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Skouroumounis GK, Elsey GM, Taylor DK. Microwave-assistance provides very rapid and efficient extraction of grape seed polyphenols. Food Chem. 2011;129:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi J, Lee YC, Hong HD, Rhee YK, Lim TG, Kim KT, Chen F, Kim HJ, Cho CW. Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activities of devil’s club (Oplopanax horridus) leaves. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017;26:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe G, Drikas M, Hayes R. Influence of characterised natural organic material on activated carbon adsorption: II. Effect on pore volume distribution and adsorption of 2-methylisoborneol. Water Res. 1997;31:1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(96)00325-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park CY, Kim S, Lee D, Dong JP, Imm JY. Enzyme and high pressure assisted extraction of tricin from rice hull and biological activities of rice hull extract. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016;25:159–164. doi: 10.1007/s10068-016-0024-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Martí MC, Salvador A, Chafer A, Berna A. Supercritical fluid extraction of resveratrol from grape skin of Vitis vinifera and determination by HPLC. Talanta. 2001;54:735–740. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(01)00319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant’Anna V, Brandelli A, Marczak LDF, Tessaro IC. Kinetic modeling of total polyphenol extraction from grape marc and characterization of the extracts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012;100:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2012.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudelska K, Szkudelski T. Resveratrol, obesity and diabetes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;635:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukkarasu M, Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Juhasz B, Zhan L, Otani H, Bagchi D, Das DK, Maulik N. Resveratrol alleviates cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes: role of nitric oxide, thioredoxin, and heme oxygenase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43:720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi HC, Patel VM, Patel RD. Adsorption of cellulose triacetate on calcium silicate. Eur. Polym. J. 1973;9:525–531. doi: 10.1016/0014-3057(73)90036-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay R, Ramalakshmi K, Rao LJM. Microwave-assisted extraction of chlorogenic acids from green coffee beans. Food Chem. 2012;130:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.06.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vinu A, Hossian KZ, Srinivasu P, Miyahara M, Anandan S, Gokulakrishnan N, Mori T, Ariga K. Carboxy-mesoporous carbon and its excellent adsorption capability for proteins. J. Mater. Chem. 2007;17:1819–1825. doi: 10.1039/b613899c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Guo J, Qi W, Su R, He Z. An effective and green method for the extraction and purification of aglycone isoflavones from soybean. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2013;22:705–712. doi: 10.1007/s10068-013-0135-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoming P, Fengping H, Frank L-YL, Yajun W, Zhanmeng L, Hongling D. Adsorption behavior and mechanisms of ciprofloxacin from aqueous solution by ordered mesoporous carbon and bamboo-based carbon. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;460:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Q, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Shi Y, Jiang C, Shi X. Preliminary separation and purification of resveratrol from extract of peanut (Arachis hypogaea) sprouts by macroporous adsorption resins. Food Chem. 2014;145:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Li X, Hao D, Li G, Xu B, Ma G, Su Z. Systematic purification of polydatin, resveratrol and anthraglycoside B from Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009;66:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2008.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]