Abstract

1,2:5,6-Dianhydrogalactitol (DAG) is a bifunctional DNA-targeting agent causing N7-guanine alkylation and inter-strand DNA crosslinks currently in clinical trial for treatment of glioblastoma. While preclinical studies and clinical trials have demonstrated antitumor activity of DAG in a variety of malignancies, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying DAG-induced cytotoxicity is essential for proper clinical qualification. Using non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) as a model system, we show that DAG-induced cytotoxicity materializes when cells enter S phase with unrepaired N7-guanine DNA crosslinks. In S phase, DAG-mediated DNA crosslink lesions translated into replication-dependent DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) that subsequently triggered irreversible cell cycle arrest and loss of viability. DAG-treated NSCLC cells attempt to repair the DSBs by homologous recombination (HR) and inhibition of the HR repair pathway sensitized NSCLC cells to DAG-induced DNA damage. Accordingly, our work describes a molecular mechanism behind N7-guanine crosslink-induced cytotoxicity in cancer cells and provides a rationale for using DAG analogs to treat HR-deficient tumors.

Introduction

Historical data from preclinical studies and clinical trials support anti-neoplastic effects of 1,2:5,6-dianhydrogalactitol (DAG) analogs in a variety of cancer types, including leukemia, brain, cervical, ovarian, and lung cancers1–6. In China, DAG is approved for the treatment of lung cancer7. Worldwide, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. The 5-year relative survival rate for lung cancer is 15% for men and 21% for women. There are two major types of lung cancer, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC accounts for 80–85% of all lung cancer and approximately 57% of newly diagnosed NSCLC patients present with stage IV metastatic disease. The median overall survival for patients with stage IV NSCLC is 4 months, and the 5-year survival rate is only 4%8–10. Brain metastases occur frequently in NSCLC patients, contributing to the poor prognosis of this disease11. Currently, the mainstay treatments of primary and metastatic NSCLC include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies with monoclonal antibodies or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in patients exhibiting epidermal growth factor receptor mutations12–15. However, the outcome of NSCLC patients remains poor mainly due to acquired platinum-based chemotherapy and TKI treatment resistance16.

DAG is a small water-soluble molecule that readily crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and accumulates in primary and secondary brain tumors4,17. Perhaps for that reason, DAG displays strong activity in animal models of metastatic NSCLC, including TKI-resistant NSCLC18. Informed by preclinical studies, DAG may have a therapeutic advantage as compared to other DNA crosslinking agents3,5.

Due to its ability to cross the BBB, DAG is currently being tested in patients with temozolomide (TMZ) refractory glioblastoma multiforme (GBM)19,20. A recently completed phase I/II clinical trial in adult refractory GBM patients established a well-tolerated dosing regimen of DAG and confirmed myelosuppression as the dose-limiting toxicity with complete reversion upon treatment termination21. However, despite encouraging preclinical and clinical data in NSCLC and GBM, timely advancement of DAG analogs toward the clinical arena is hampered by inadequate understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for DAG-mediated cytotoxicity in cancer cells. We therefore used NSCLC as a model system to investigate the mechanisms of cytotoxicity imposed by the clinical-grade DAG analog VAL-08322.

Results

Loss of lung cancer cell viability after DAG treatment

To investigate the effects of DAG on lung cancer cells, we evaluated the cytotoxic activities of VAL-083 in a panel of NSCLC cell lines. Treatment of A549, H2122, and H1792 cells with 10 μM VAL-083 for 72 h resulted in dramatic morphological changes such as swelling and cell detachment (Fig. 1a). To further characterize the effect of DAG on tumor cells, we treated H1792, H2122, H23, and A549 NSCLC cell lines with different concentrations of VAL-083 for 72 h and subsequently determined viability of each cell line. The analysis showed a concentration-dependent loss of viability in all VAL-083-treated cell lines with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values in the low µM concentration range (Fig. 1b). In summary, these data demonstrate cytotoxic effects of DAG on NSCLC cells.

Fig. 1. Cytotoxicity of DAG in NSCLC cell lines.

a Bright-field images of A549, H2122, and H1792 cells cultured in 10 % FBS DMEM or RPMI 1640 medium for 72 h with or without 10 μM VAL-083 were shown. The scale bar represents 100 μm. b Four NSCLC cell lines A549, H23, H1792, and H2122 cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates and treated with different concentrations of VAL-083 (0, 100 nM, 500 nM, 1 μM, 2.5 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM, 25 μM, 50 μM, and 100 μM) for 72 h. Following the treatment, crystal violet assay was performed to detect the absorbance at 560 nm wavelength. The IC50 value of VAL-083 was determined by fitting a sigmoidal dose-response curve to the data using GraphPad Prism 6. The data on the curve are presented as mean ± standard error. Each cell line was tested in three to four individual experiments

DAG induces persistent DNA damage in lung cancer cells

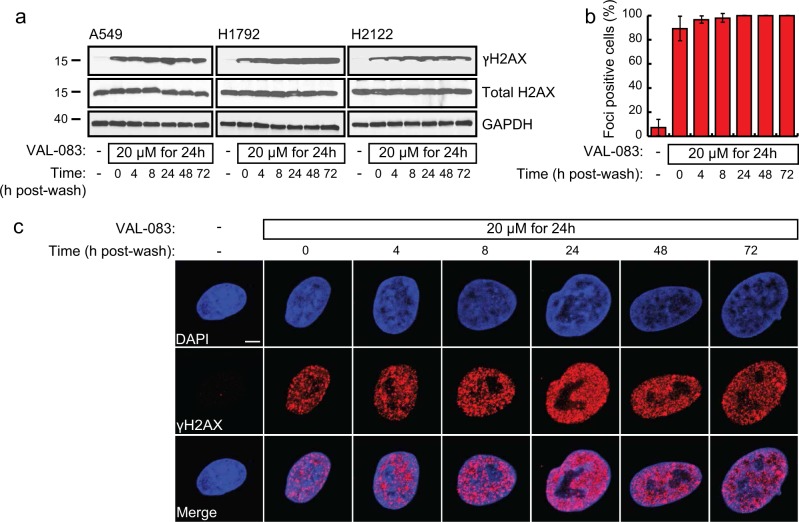

Many chemotherapeutic drugs work by inducing different types of DNA damage in rapid-dividing cancer cells. DAG has been reported to have bifunctional DNA-targeting activity leading to the formation of N7-monoalkylguanine and inter-strand DNA crosslinks22. To investigate the effects of DAG on DNA integrity, we examined VAL-083-treated NSCLC cells for phosphorylated histone variant H2AX (ɣH2AX), an extensively used surrogate marker of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs)23,24. Biochemical assessment of A549, H1792, and H2122 cells treated with VAL-083 for 24 h followed by removal of the drug showed strong ɣH2AX expression that persisted for 72 h after drug removal (Fig. 2a). This was supported by an immunofluorescence (IF) imaging analysis showing sustained ɣH2AX foci formation in 90–100 % of the cells (Fig. 2b) over a similar time frame (Fig. 2c). These data suggest that DAG induces DNA DSBs in NSCLC cells that cannot be repaired within a 72 h recovery period. In addition, VAL-083 induced strong ɣH2AX expression with at least 10 h incubation time (Supplementary Fig. S1a) and showed dose-dependent pattern (Supplementary Fig. S1b).

Fig. 2. DAG induces DNA damage in NSCLC cells.

a A549, H1792, and H2122 cells were treated with 20 μM VAL-083 for 24 h followed by washing and replacing with complete medium in culture for various periods of time (0, 4, 8, 24, 48, or 72 h). Then, cells were collected for protein extraction, and 50 μg was analyzed for phosphorylated and total H2AX expression by western blot using specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies as described under “Materials and methods”. Representative images are shown for the time-course effect of VAL-083 on ɣH2AX expression. Total H2AX and GAPDH served as loading controls. b Cultured A549 cells were treated with 20 μM VAL-083 for 24 h. After that, cells were washed and replaced with complete medium for an additional incubation time of 0, 4, 8, 24, 48, or 72 h. Then, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained with anti-ɣH2AX antibody. Quantification of ɣH2AX foci (cells with >10 foci were considered as “foci-positive”) from 40 to 50 cells per sample was shown. c Representative confocal images from each experimental conditions in b were shown with ɣH2AX in red. The scale bar represents 5 μm

Replication-dependent DNA damage of NSCLC cells upon DAG treatment

We next investigated the effect of DAG on cell cycle progression using flow cytometric analysis of propidium iodide (PI)-stained NSCLC cells. VAL-083 treatment induced a strong dose-dependent S/G2-phase cell cycle arrest in A549 (Fig. 3a) and H1792 (Fig. 3b) NSCLC cells. This result suggests that DAG-mediated cytotoxicity likely depends on replication. To further determine the role of replication for DAG-induced cytotoxicity, we synchronized the majority of A549 cells in G0/G1 phase by serum starvation for 24 h (Fig. 3c). Cells were then released from the cell cycle arrest by addition of serum with or without 5 μM VAL-083 and followed by flow cytometry. While untreated cells rapidly assumed a normal cell cycle profile after serum addition, cells subjected to VAL-083 displayed a time-dependent S/G2 phase arrest visual at and after 19 h in complete medium (Fig. 3c). Notably, this concentration of VAL-083 treatment did not increase the sub-G1 population of cells (DNA content <2 N reflects cellular debris and apoptotic cells) indicating that the time-dependent decrease in G0/G1 was not due to increased cell death (Fig. 3c). In parallel western blot analysis of cleaved caspase 3 expression confirmed the lack of apoptosis in VAL-083-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 3. DAG-induced DNA damage occurs in S phase of the cell cycle.

a A549 cells were treated with 5 or 25 μM VAL-083 for 24 h. After that, cells were collected for cell cycle analysis using PI staining by flow cytometry. b After treatment with different concentrations of VAL-083 (1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM) in H1792 cells for 48 h, cell cycle analysis with PI staining was performed using flow cytometry. c A549 cells were synchronized by serum starvation (ST) for 24 h before treatment with or without 5 μM VAL-083 for the indicated time periods (1, 4, 19, 24, 44, or 49 h). Cells were then collected, fixed, and subsequently stained with PI for cell cycle distribution analysis by flow cytometry. For additional experimental details, see “Materials and methods”. The representative flow cytometric plots from two individual experiments are shown. d Flow chart outlining the experimental conditions used in e. e A549 cells (synchronized by 24 h serum starvation) were treated with 50 μM VAL-083 for 1 h and replaced with complete medium for another 24 h incubation. Then, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained with anti-cyclin A2 and anti-ɣH2AX antibodies. Representative IF images are shown with cyclin A2 in green and ɣH2AX in red. The scale bar represents 10 μm. f In all, 100–120 cells were examined from each treatment condition as in e. The percentages of two categories (cyclin A2−/ɣH2AX− and cyclin A2+/ɣH2AX+) of A549 cells are shown with corresponding statistical analysis (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; Student’s t test). g A549 cells were seeded with either serum-deprived or complete medium in 96-well culture plates. After 24 h incubation, cells were treated with 0, 100 nM, 500 nM, 1 μM, 2.5 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM, 25 μM, 50 μM, or 100 μM VAL-083 for 72 h. Following the treatment, the percentage of survival cells compared to the untreated condition was determined by crystal violet assay. The data are presented as mean ± standard error. H1792 and H2122 cells were also tested in the same experimental condition

Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are key regulators of eukaryotic cell cycle progression. Activation of cyclin B-Cdc2 kinase complexes trigger M-phase entry, whereas cyclin A-Cdk2 complexes control the progression through S phase25–27. Accordingly, cyclin expression is tightly regulated throughout the cell cycle where cyclin A is expressed exclusively in S phase plateauing in G2 phase28. Using cyclin A as a marker of S phase entry, we performed IF staining for cyclin A2 and ɣH2AX on A549 cells with or without VAL-083 pulse treatment (50 μM VAL-083 for 1 h) (Fig. 3d). The analysis showed that synchronized A549 cells displayed a dramatic accumulation of cyclin A2 (green) and ɣH2AX (red) expression after pulse treatment with VAL-083 followed by 24 h in complete medium (Fig. 3e). Importantly, the population of cells double-positive for cyclin A2+/ɣH2AX+ were significantly increased after VAL-083 pulse treatment for 1 h followed by washout for 24 h (VAL 1 h + WO 24 h) while double-negative cyclin A2−/ɣH2AX− cells decreased (Fig. 3f). This indicates that VAL-083-induced DNA N7-guanine crosslinks translate into DSBs in S/G2 phase of the cell cycle. To further validate the observed replication-dependent cytotoxicity of VAL-083 in NSCLC cell lines, we compared survival rates of cells cultured in complete medium with cells cultured in serum-deprived medium, challenged with increasing concentrations of VAL-083. Indeed, A549, H1792, and H2122 cells prohibited from entering S phase due to serum deprivation all showed resistance to VAL-083-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 3g). Combined, these data suggest that DAG-induced cytotoxicity materializes as NSCLC cells progress into S phase of the cell cycle with unrepaired N7-guanine DNA crosslink lesions.

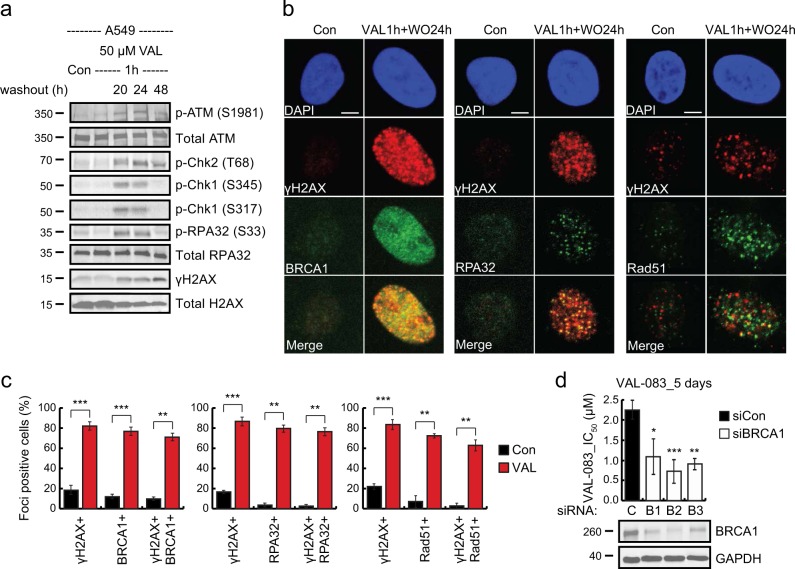

DAG-induced DNA damage is preferentially repaired by homologous recombination

As DAG induces DNA DSBs in S phase, cytotoxicity in cancer cells likely depends at least partially on their ability to repair DNA in S/G2 phase of the cell cycle. DNA DSBs can be repaired by either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR). While NHEJ can occur throughout the cell cycle, HR is restricted to the S and G2 phases where sister chromatids are available as templates for sequence homology-guided repair29. Since DAG-induced DNA DSBs materialized specifically in S/G2, we hypothesized that NSCLC cells would repair these lesions by HR. To test this hypothesis, we monitored DNA DSB sensors and effectors involved in the HR pathway in NSCLC cells after VAL-083 treatment. VAL-083 pulse treatment followed by 20–48 h incubation in complete medium without VAL-083 triggered the activation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase in A549, H1792, and H2122 cells (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S3). This was associated with threonine 68 phosphorylation of S phase checkpoint kinase Chk2 and the presence of ɣH2AX. Upon activation of HR repair, the DNA surrounding the DSBs is processed in an enzymatic step that depends on CtIP and hepatoma-derived growth factor family co-factors to create a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) template for homology pairing30–33. The resected ssDNA is subsequently occupied by ssDNA-binding replication protein A (RPA32) that is phosphorylated on serine 33 by the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) kinase in response to ssDNA exposure34. This event triggers the final step in the HR pathway where homology repair is completed in a Rad51-dependent manner35. Indeed, VAL-083 treatment induced phosphorylation of RPA32 as well as the Chk1 kinase, a well-known phospho-target of ATR (Fig. 4a). In aggregate, these data suggest that NSCLC cells repair DAG-induced DSBs by HR. To further substantiate this finding, we analyzed the recruitment of key HR repair proteins to ɣH2AX foci in NSCLC cells treated with VAL-083 by confocal microscopy. The analysis showed that HR repair proteins BRCA1, RPA32, and Rad5135 co-localized with ɣH2AX foci induced by VAL-083 (Fig. 4b) and these co-localizations were statistically significant (Fig. 4c). Combined, these data demonstrate that NSCLC cells repair DAG-induced DSBs by HR repair.

Fig. 4. DAG-induced DNA damage is repaired by homologous recombination.

a A549 cells were synchronized with 24 h serum starvation. After that, cells were incubated in complete medium with treatment of 50 μM VAL-083 for 1 h. Then, cells were washed and replaced with complete medium for an additional incubation time of 20, 24, or 48 h. Cell lysates were then extracted for western blot analysis of the sensors and effectors involved in the HR DNA damage response pathway using the following antibodies: phospho-ATM (Ser1981), phospho-Chk2 (Thr68), phospho-Chk1 (Ser345 and Ser317), phospho-RPA32 (Ser33), and ɣH2AX. Representative images are shown from three to four independent experiments. b A549 cells were synchronized with 24 h serum starvation. After that, cells were incubated in complete medium with treatment of 50 μM VAL-083 for 1 h. Then, cells were washed and replaced with complete medium for an additional incubation time of 24 h. Representative confocal images of indicated proteins (BRCA1, RPA32, Rad51, and ɣH2AX) were shown. The scale bar represents 5 μm. c Quantification of foci-positive A549 cells presented in b from 60–80 cells per condition were shown. Statistical analyses were obtained from three independent experiments (**p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; Student’s t test). d A549 cells were transfected with either negative control (C) or three BRCA1-targeting siRNAs (B1, siBRCA1-2; B2, siBRCA1-15; or B3, siBRCA1-17) for 24 h. Cells were then seeded in 96-well culture plates and treated with different concentrations of VAL-083 (0, 100 nM, 500 nM, 1 μM, 1.5 μM, 2.5 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM, 25 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, and 200 μM) for 5 days. Following the treatment, crystal violet assay was performed to detect the absorbance at 560 nm wavelength. The IC50 value of VAL-083 was determined by fitting a sigmoidal dose-response curve to the data using GraphPad Prism 6. The IC50 values of VAL-083 in control or BRCA1-knockdown cells are presented as mean ± standard error (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; Student’s t test). Cell lysates from the control or BRCA1-knockdown cells were analyzed by western blot with antibody against BRCA1, and GAPDH was used as a loading control. The representative images are shown from three independent experiments

Our data entertain a prediction that cancer cells deficient in HR repair would have increased sensitivity to DAG. To confirm this prediction, we knocked down the essential HR repair protein BRCA136,37 in NSCLC cells using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) before treatment with VAL-083. Indeed, knockdown of BRCA1 using three non-overlapping siRNAs significantly sensitized A549 cells to VAL-083 (Fig. 4d). These data confirm the prediction that cancer cells deficient in HR repair are unable to resolve DAG-induced DSBs.

Discussion

DNA crosslinking agents are widely used as chemotherapy in a variety of cancers38. While they all target DNA, there are small differences that distinguishes these agents from each other. For example, most agents have more than one function and it is often difficult to uncouple these functions in terms of mechanism of action. DAG is a bifunctional DNA-targeting agent causing N7-monoalkylguanine and inter-strand DNA crosslinks22, but it has also been reported to inhibit angiogenesis7. DAG has been shown to interact with DNA yielding 7-(1-deoxygalactit-1-yl)guanine, 7-(1-deoxyanhydrogalactit-1-yl)guanine, and 1,6-di(guanin-7-yl)-1,6-dideoxygalactitol, of which the last product indicates inter- or intra-strand crosslink formation39. Up to this date, more than 40 NCI-sponsored phase I and II clinical trials involving DAG has been conducted in the United States. Preclinical and clinical trial data suggest antitumor activity of DAG in several malignancies including lung cancer, brain tumors, leukemia, cervical cancer, and ovarian cancer1–6. Also, an open-label post-market clinical trial in China investigates the activity of VAL-083 in relapsed or refractory NSCLC patients40.

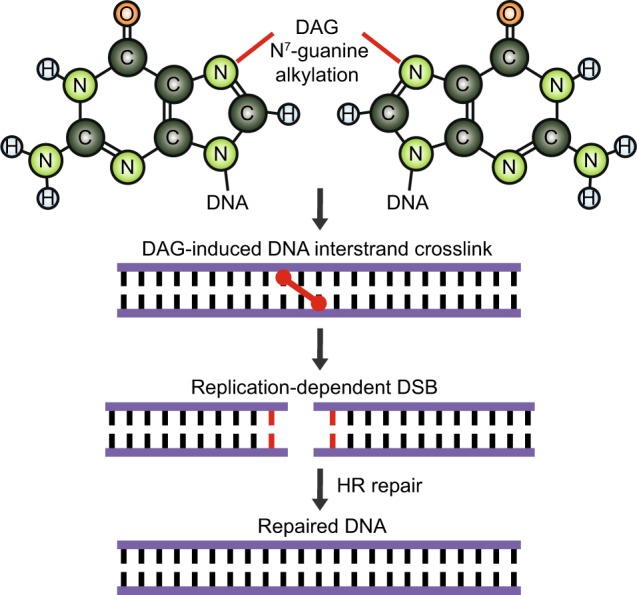

TMZ is a DNA alkylating agent targeting N7 and O6 positions of guanine and is currently used as first-line treatment of GBM41. Interestingly, while TMZ and DAG have at least partially overlapping properties in terms of DNA interactions, mechanisms of cytotoxicity appear to be different. For example, GBM cells resistant to TMZ still show sensitivity to DAG42, indicating non-overlapping functions between the two agents. Precise knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor cell cytotoxicity is essential for optimal positioning of chemotherapeutic drugs in a clinical context. For that reason, we decided to dissect and describe the cytotoxic mechanisms of DAG using NSCLC as our model system. We found that VAL-083, a good manufacturing practice-produced clinical-grade DAG, is well-tolerated by cells as long as they are in G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cells have several systems in place that can resolve DNA crosslinks and methylations such as nucleotide excision repair (intra-strand) and the Fanconi anemia system (inter-strand)38,43. Repair of DNA crosslinks in G1 phase is supported by the G1/S phase checkpoint machinery that keeps cells in G1 until repair has been completed44. However, the G1/S phase checkpoint is often compromised in cancer cells and in this scenario, cells may enter S phase with unrepaired DNA lesions45. When the replication forks collide with the DNA lesions, replication is blocked exposing stretches of ssDNA that will subsequently be bound by RPA. The violent collision between the DNA lesion and the replication machinery will often result in DNA DSBs, which are catastrophic for the cells46. Indeed, we found the cytotoxic effect of DAG on NSCLC cells to develop in S phase indicating that these cells progress from G1 to S phase with unrepaired DNA lesions. In S phase, DAG-treated cells display a profound ɣH2AX response indicative of DNA DSBs. We furthermore found that these DAG-induced DSBs activated the HR pathway and inhibition of HR dramatically sensitized NSCLC cells to DAG. As such, our data suggest that DAG-induced DNA lesions translate into replication-dependent DNA DSBs in S phase that are subsequently repaired by HR (Fig. 5). Importantly, our work provides a clinical rationale for positioning DAG-based chemotherapy in cancers deficient in HR repair.

Fig. 5. Model of the mechanism of action of DAG in lung cancer cells.

DAG treatment induces inter-strand DNA crosslinks through N7-guanine alkylation, leading to replication-dependent DNA double-strand breaks (DSB). Lung cancer cells respond to the DAG-induced DNA DSB through activation of HR DNA repair

Materials and methods

Reagents and cell culture

VAL-083 was obtained from DelMar Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Vancouver, Canada and Menlo Park, CA, USA). PI solution (1 mg/ml) and glutaraldehyde solution (grade I, 50% in H2O) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Canada). Sorenson’s solution was prepared with 9 mg trisodium citrate, 195 ml 0.1 N HCl, 500 ml 90% ethanol, and 305 ml distilled water. All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. A549 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. H2122, H1792, and H23 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Crystal violet cell proliferation assay

Following 72 h of different concentrations of VAL-083 treatment, cells were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde solution for 5 min. After rinsing with distilled water, cells were incubated with 0.1% crystal violet solution dye for 10 min. Cells were then gently washed with distilled water and air-dried. The crystals on the plate were dissolved in Sorenson’s solution before reading absorbance at 560 nm wavelength with a microplate reader. Survival cells were expressed as the percentage compared to untreated cells.

Cell cycle analysis using PI staining

Cell cycle distribution was evaluated based on DNA content using PI staining. Serum starvation (24 h)-synchronized cells were treated with 5 μM VAL-083 for 1, 4, 19, 24, 44, and 49 h. Cells were then trypsinized, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Cell pellets were fixed in 70% ethanol at least overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with 500 μl PI solution in PBS containing 50 μg/ml PI, 100 μg/ml RNase A, and 0.05% Triton X-100 for 40 min at 37 °C in the dark. Thereafter, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. DNA content were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS Canto II), and histograms and quantitative analyses of the proportions of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases were made using FlowJo software. Untreated cells were included as control.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in EBC buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor and protease inhibitor (Roche, Mississauga, Canada). Cellular proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. After incubation with blocking buffer for 1 h, the membrane was incubated with designated primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Then, membrane was washed three times for 10 min with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) for 1–2 h. Membrane was washed with TBST three times and developed with Pierce ECL substrate system (ThermoFisher Scientific, Burlington, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting: ɣH2AX (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA, 2577); H2AX (Abcam, Toronto, Canada, ab11175); phospho-ATM (Ser1981) (Rockland Antibodies and Assays, Limerick, PA, USA, 200-301-400); ATM (Cell Signaling Technology, 2873); GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, 5174); phospho-RPA32 (Ser33) (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA, A300-246A); phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) (Cell Signaling Technology, 2348); phospho-Chk1 (Ser317) (Cell Signaling Technology, 12302); phospho-Chk2 (Thr68) (Cell Signaling Technology, 2661); RPA32 (Abcam, ab2175); BRCA1 (Novus Biologicals, Oakville, Canada, NB 100-404); and cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9661). Representative blotting images were shown from three to four independent experiments.

IF and microscope

Cells were grown on glass coverslips for at least 16 h before serum starvation for 24 h. Synchronized cells were treated with 50 μM VAL-083 for 1 h followed by washout and incubation with complete medium for another 24 h. Subsequently, cells were washed once with PBS and fixed for 30 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature. For DNA damage foci detection, cells were pre-extracted with cytoskeletal buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM MgCl2, 300 mM sucrose, and 0.5% Triton X-100) for 5 min at 4 °C before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde solution. Fixed cells were washed three times with PBS and permeabilized for 20 min with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. After washing with PBS for three times and blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with corresponding primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution. The next day, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with appropriate fluorophore-labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS for three times, the coverslips were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Images were acquired using Zeiss AxioObserver microscope and confocal LSM-780 microscope. The LSM-ZEN software was used for analyzing the images. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used in IF staining: ɣH2AX (Cell Signaling Technology, 2577); cyclin A2 (Abcam, ab16726); ɣH2AX (EMD Millipore, Etobicoke, Canada, 05-636); BRCA1 (Abcam, ab16780); Rad51 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, H8349); RPA32 (Abcam, ab2175); donkey anti-rabbit Alexa-Fluor 594 (ThermoFisher Scientific, A21207); donkey anti-rabbit Alexa-Fluor 488 (ThermoFisher Scientific, A21206); donkey anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 594 (ThermoFisher Scientific, A21203); and donkey anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 488 (ThermoFisher Scientific, A21202). Representative images were shown from three independent experiments.

siRNA transfection

A549 cells were transfected with either a control siRNA or siRNAs targeting BRCA1 using RNAiMAX transfection reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After 24 h of transfection, A549 cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates and treated with different concentrations of VAL-083 for 5 days followed by crystal violet assay. In parallel cell lysates were collected for western blot verification of BRCA1 knockdown. The siRNAs used in this study were as follows: C, siCon (negative control medium GC duplex, Invitrogen, 462001); B1, siBRCA1-2 (Qiagen, Toronto, Canada, SI00096313); B2, siBRCA1-15 (Qiagen, SI02664368); and B3, siBRCA1-17 (Qiagen, SI03103975).

Statistical analysis

Where indicated, p-values were calculated using Student’s t test. Data were presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank DelMar Pharmaceuticals for kindly providing us with VAL-083. This work was supported by National Research Council Industrial Research Assistance Program [IT06135]; Mitacs [F15-03171]; DelMar Pharmaceuticals, Inc. [F14-03316]; and the Vancouver Prostate Centre. Funding for open access charge: National Research Council Industrial Research Assistance Program.

Conflict of interest

A.S., J.B., and D.B. are employees of DelMar Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by I. Amelio

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-018-1069-9).

References

- 1.Nemeth L, et al. Pharmacologic and antitumor effects of 1,2:5,6-dianhydrogalactitol (NSC-132313) Cancer Chemother. Rep. 1972;56:593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas CD, Stephens RL, Hollister M, Hoogstraten B. Phase I evaluation of dianhydrogalactitol (NSC-132313) Cancer Treat. Rep. 1976;60:611–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eagan RT, et al. Platinum-based polychemotherapy versus dianhydrogalactitol in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1977;61:1339–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eagan RT, et al. Dianhydrogalactitol and radiation therapy. Treatment of supratentorial glioma. JAMA. 1979;241:2046–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.1979.03290450044023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagan RT, et al. Phase II study of the combination of dianhydrogalactitol, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (DAP) in patients with advanced squamous cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1981;65:517–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas CD, Baker L, Thigpen T. Phase II evaluation of dianhydrogalactitol in lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1981;65:115–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang X, et al. Dianhydrogalactitol, a potential multitarget agent, inhibits glioblastoma migration, invasion, and angiogenesis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;91:1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2017.html (2017).

- 9.Cetin K, Ettinger DS, Hei YJ, O’Malley CD. Survival by histologic subtype in stage IV nonsmall cell lung cancer based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;3:139–148. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S17191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howlader, N. et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/ (2016).

- 11.Barnholtz-Sloan JS, et al. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:2865–2872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfister DG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:330–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pisters KM, et al. Cancer Care Ontario and American Society of Clinical Oncology adjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant radiation therapy for stages I-IIIA resectable non small-cell lung cancer guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:5506–5518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:6251–6266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minari R, Bordi P, Tiseo M. Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer: review on emerged mechanisms of resistance. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5:695–708. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang A. Chemotherapy, chemoresistance and the changing treatment landscape for NSCLC. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckhardt S, et al. Uptake of labeled dianhydrogalactitol into human gliomas and nervous tissue. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1977;61:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steino A, et al. In vivo efficacy of VAL-083 in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:824. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2014-824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fouse SD, et al. Dianhydrogalactitol inhibits the growth of glioma stem and non-stem cultures, including temozolomide-resistant cell lines, in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2562. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2015-2562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih KC, et al. Phase I/II study of VAL-083 in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2063. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.2063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ClinicalTrials.govNCT01478178. Safety study of VAL-083 in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01478178. (2011–2016).

- 22.Institoris E, Szikla K, Otvos L, Gal F. Absence of cross-resistance between two alkylating agents: BCNU vs bifunctional galactitol. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1989;24:311–313. doi: 10.1007/BF00304764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo LJ, Yang LX. Gamma-H2AX—a novel biomarker for DNA double-strand breaks. Vivo. 2008;22:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podhorecka, M., Skladanowski, A. & Bozko, P. H2AX phosphorylation: its role in dna damage response and cancer therapy. J. Nucleic Acids2010, Article ID 920161 (2010) (PMID: 20811597). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Heichman KA, Roberts JM. Rules to replicate by. Cell. 1994;79:557–562. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90541-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King RW, Jackson PK, Kirschner MW. Mitosis in transition. Cell. 1994;79:563–571. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yam CH, Fung TK, Poon RY. Cyclin A in cell cycle control and cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:1317–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8510-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman JR, Taylor MR, Boulton SJ. Playing the end game: DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sartori AA, et al. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.You Z, et al. CtIP links DNA double-strand break sensing to resection. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:954–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daugaard M, et al. LEDGF (p75) promotes DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:803–810. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baude A, et al. Hepatoma-derived growth factor-related protein 2 promotes DNA repair by homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:2214–2226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S, et al. Distinct roles for DNA-PK, ATM and ATR in RPA phosphorylation and checkpoint activation in response to replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10780–10794. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng L, Fong KW, Wang J, Wang W, Chen J. RIF1 counteracts BRCA1-mediated end resection during DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:11135–11143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.457440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jasin M. Homologous repair of DNA damage and tumorigenesis: the BRCA connection. Oncogene. 2002;21:8981–8993. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konstantinopoulos PA, Ceccaldi R, Shapiro GI, D’Andrea AD. Homologous recombination deficiency: exploiting the fundamental vulnerability of ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1137–1154. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institoris E. In vivo study on alkylation site in DNA by the bifunctional dianhydrogalactitol. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1981;35:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(81)90144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steino, A. et al. Post-market clinical trial of dianhydrogalactitol in the treatment of relapsed or refractory non-small cell lung cancer. https://library.iaslc.org/search-speaker?search_speaker=29999 (2015).

- 41.Fan CH, et al. O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase as a promising target for the treatment of temozolomide-resistant gliomas. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e876. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steino A, et al. The unique mechanism of action of VAL-083 may provide a new treatment option for some chemo-resistant cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;12:B252. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.TARG-13-B252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ceccaldi R, Sarangi P, D’Andrea AD. The Fanconi anaemia pathway: new players and new functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:337–349. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abraham RT. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2177–2196. doi: 10.1101/gad.914401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson SP. Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:687–696. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.