Abstract

A mechanistic link between trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and atherogenesis has been reported. TMAO is generated enzymatically in the liver by the oxidation of trimethylamine (TMA), which is produced from dietary choline, carnitine and betaine by gut bacteria. It is known that certain members of methanogenic archaea (MA) could use methylated amines such as trimethylamine as growth substrates in culture. Therefore, we investigated the efficacy of gut colonization with MA on lowering plasma TMAO concentrations. Initially, we screened for the colonization potential and TMAO lowering efficacy of five MA species in C57BL/6 mice fed with high choline/TMA supplemented diet, and found out that all five species could colonize and lover plasma TMAO levels, although with different efficacies. The top performing MA, Methanobrevibacter smithii, Methanosarcina mazei, and Methanomicrococcus blatticola, were transplanted into Apoe−/− mice fed with high choline/TMA supplemented diet. Similar to C57BL/6 mice, following initial provision of the MA, there was progressive attrition of MA within fecal microbial communities post-transplantation during the initial 3 weeks of the study. In general, plasma TMAO concentrations decreased significantly in proportion to the level of MA colonization. In a subsequent experiment, use of antibiotics and repeated transplantation of Apoe−/− mice with M. smithii, led to high engraftment levels during the 9 weeks of the study, resulting in a sustained and significantly lower average plasma TMAO concentrations (18.2 ± 19.6 μM) compared to that in mock-transplanted control mice (120.8 ± 13.0 μM, p < 0.001). Compared to control Apoe−/− mice, M. smithii-colonized mice also had a 44% decrease in aortic plaque area (8,570 μm [95% CI 19587–151821] vs. 15,369 μm [95% CI [70058–237321], p = 0.34), and 52% reduction in the fat content in the atherosclerotic plaques (14,283 μm [95% CI 4,957–23,608] vs. 29,870 μm [95% CI 18,074–41,666], p = 0.10), although these differences did not reach significance. Gut colonization with M. smithii leads to a significant reduction in plasma TMAO levels, with a tendency for attenuation of atherosclerosis burden in Apoe−/− mice. The anti-atherogenic potential of MA should be further tested in adequately powered experiments.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic vascular disease is the leading cause of death in the US1. The gut microbiome is now recognized as a mediator of numerous host physiological processes. Changes in the gut microbiome have been causally linked to several metabolic, inflammatory, and cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis2,3. Systemic concentrations of the gut microbe-derived metabolite, trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), is associated with atherosclerosis and major adverse cardiovascular events4–6. Choline diet dependent enhancement in atherosclerosis could be prevented by either gut microbiota suppression with broad spectrum antibiotics6, or in more recent studies, administration of an inhibitor of microbial choline trimethylamine (TMA) lyase activity and therefore TMAO generation (4,4-dimethyl-1-butanol)7, indicating a causal link between TMAO and atherosclerosis. In this study, we tested a novel microbiota-based approach to reduce systemic exposure of TMAO.

Gut microbes generate TMA from ingested precursors, including choline6, carnitine4, phosphatidylcholine5, betaine8, and trimethyllysine9. TMA is converted to TMAO by the host hepatic flavin monooxygenase 3 (FMO3)10. Multiple phylogenetically distinct bacteria are involved in TMA production11. There are many microbial families, genus, and species which possess microbial enzymes that can make TMA. There have been three microbial enzyme genes/sources of TMA thus far identified; the cutC/D11, the cntA/B gene12, and the YeaW/Z gene13.

In humans, FMO3 gene mutations cause the inherited disorder primary trimethylaminuria (TMAU)14, also known as the fish odor syndrome, which severely reduces the ability to convert TMA to TMAO. Consequently, the affected individuals excrete large amounts of odorous TMA in their urine, sweat, and breath15. Although the disorder is not known to affect patient health, it can have profound social and psychological consequences. Development of a probiotic that can catalytically consume TMA could also serve as a therapeutic approach for treating this genetic disorder.

Methanogenic archaea (MA) represents a distinct group of anaerobic archaea that produce methane as the end-product of their anaerobic respiration. The abundance and diversity of gut MA in humans is highly variable and limited to a few species16–18. Methanobrevibacter smithii is the dominant methanogen in the human gut, detected in 95.7% of individuals, whereas Methaomassiliicoccus luminyensis is detected only in 4% of individuals19. Certain MA such as Methanosarcina species are known to use methylated amines as growth substrates20,21. A catabolic microbe that literally consumes TMA preventing/intercepting TMA prior to when it can be absorbed and converted into TMAO, would serve as a therapeutic intervention. However, up until now this potential has largely remained a theoretical concept. However, up until now this potential has largely remained a theoretical concept. In this study, we tested the effect of MA colonization on blood TMAO level and atherosclerosis burden in the atherosclerosis prone Apoe−/− mouse model.

Materials and Methods

All methods were performed in accordance to guidelines and regulations, and under approval of the Institutional Biosafety Committee of The George Washington University.

Methanogenic archaea (MA)

Selected species of known human gut and non-gut MA including: (a) Methanobrevibacter smithii, strain PS (DSM-86), (b) Methaomassiliicoccus luminyensis, strain B10 (DSM-25720), (c) Methanosarcina mazei, strain S-6 (DSM-2053), (d) Methanoimicrococcus blatticola, strain PA (DSM-13328) and (e) Methanohalophilus portucalensis, strain FDF-1 (DSM-7471) were obtained from DSMZ (Germany). M. smithii and M. luminyensis were selected because these are indigenous human gut MA22. For comparison, we selected M. blatticola (isolated from the hindgut of cockroach Periplaneta americana)23, M. mazei (isolated from a laboratory digester)24, and M. portucalensis (isolated from sediments at a saline lake)25.

Animal Studies

All animal studies were performed under approval of the Animal Research Committee of The George Washington University. To test the efficacy of MA to colonize gut and metabolize TMA, 4-week-old female C57BL6J (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were randomly selected for transplantation with one of the MA or sham, and placed on high TMA/choline diet. Because of the small sample size (n = 3/group), considering that the male mice have lower plasma TMAO levels, we used only female mice in this pilot study6,10. Prior to transplantations, endogenous gut microbiota were suppressed using an oral cocktail of poorly absorbed antibiotics previously reported to suppress TMA and TMAO levels6 (0.5 g/L vancomycin, 1 g/L neomycin sulfate, 1 g/L metronidazole, 1 g/L ampicillin) administered in drinking water ad lib for three weeks, refreshed 3 times per week. Each mouse was inoculated with a single gavage of 108 MA 24 hours after the antibiotic treatment was completed. The test groups (n = 3/group) received a 0.1 ml gavage of corresponding MA in liquid growth media. The control groups (n = 3 each) received a 0.1 ml gavage of liquid growth media. Following transplantations, mice were supplemented with choline (1.0%, Sigma Aldrich) and TMA (0.12%, Sigma Aldrich) in drinking water ad lib, refreshed 3 times per week. The negative control group (NC) received untreated water. Both choline and TMA were given to animals since antibiotic treatment depletes most of the TMA-generating bacteria. All animals received standard chow diet for the entire study. Blood plasma and fresh stool samples were collected from the mice on days 2, 10, and 30 post-transplantation and stored at −80 °C, until processed. In a second study, 4-week-old female C57BL6J mice with Apoe−/− background (n = 5/group) (Jackson Laboratory) were treated with antibiotics, transplanted with M. smithii, M. mazei, and M. blatticola and fed with high TMA/choline diet as described above to determine the impact of MA on TAMO concentration. In a third study, we examined the effect of sustained high colonization with M. smithii on TMAO in Apoe−/− mice (n = 5/group). The experiment was performed as described above, except that M. smithii transplantation was repeated every three weeks, until the end of the study. One group of mice (n = 5) was maintained throughout the study on an antibiotic regimen (0.5 g/L vancomycin and 1 g/L ampicillin) to which MA are resistant, in order to chronically suppress the endogenous gut microbiota and enhance MA colonization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Animal experiments study design.

| Mouse experiment | Mouse model | Archaea species studied | #of mice/group (N) | Duration of study (weeks) | Transplant frequency | Antibiotic treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C57BL/6 | MS, MM, MB, ML, MP | 3 | 4 | Once | Pre-transplant |

| 2 | Apoe −/− | MS, MM, MB | 5 | 4 | Once | Pre-transplant |

| 3 | Apoe −/− | MS | 5 | 12 | Every 3 weeks | Pre- and post-transplant |

MS, M. smithii; MM, M. mazei; MB, M. blatticola; ML, M. luminyensis; MP, M. portucalensis.

Quantification of MA

Gut colonization by the MA was determined using quantitative real-time PCR (q-PCR). Briefly, microbial DNA was extracted from stool samples using the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil kit. The stool specimens were tested for the levels of engraftment by q-PCR as previously described26. Arch344f (ACGGGGYGCAGCAGGCGCGA)26 and Arch806r (GGACTACCCGGGTATCTAAT)27 primers were used to target the archaea 16 S rRNA gene present in MA. Q-PCR was performed for detection and quantification of microbes using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems)28. PCR products amplified from the bacterial and archaeal 16 s rRNA genes were cloned and grown in transformed E. coli to establish a standard curve, as described previously29. The accuracy of the q-PCR assay was confirmed through melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. Calibration curves were obtained using 10-fold serial dilutions of known concentrations of cloned DNA samples that were prepared in the laboratory.

16S rRNA-based taxonomic survey

The V4 region of the 16 S rRNA gene was PCR amplified using barcoded primers30 essentially as previously described31. Briefly, for each reaction, 2 μL of extracted DNA was combined with 12.5 μL 2X Phusion Hot Start II High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 100 nM each of forward and reverse primers. The primers were designed containing the Illumina linker adaptor, a unique index sequence, followed immediately by a variable sequence spacer (0–6 bases) and 16 S rRNA gene primers (Table 2). The PCR was carried out in a 25 µl reaction in a Thermal Cycler (Applied BioSystem GeneAmp PCR system 9700) with the following parameters: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min., followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 50 °C for 60 s, and 72 °C for 90 s with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR was performed in triplicates with two PCR controls, a negative water control and a positive Mock Community control (M.G. Serrano, unpublished). All amplicons were quantified using Picogreen (Invitrogen/Thermo Scientific) and a spectrofluorimeter (Biotek). Amplicons were combined in equal volumes, followed by removal of unincorporated primers, salts and enzymes using Agencourt AMpure XP beads as described by the manufacturer. The DNA concentration of this concentrated pool was confirmed by qPCR using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina platform. The library pool was diluted and denatured as described in the Illumina MiSeq library preparation guide. The sequencing run was conducted on the Illumina MiSeq using 600 cycles reagent kit (version 3) and 2 × 300 b paired end sequencing. Demultiplexing of sequence reads was performed using an in-house Python script. Raw paired-end sequence data was merged and quality-filtering using the MeFiT software32 which invokes CASPER33 for merging paired-end sequences and quality filters them using a meep-score (maximum expected error rate) cutoff of 1.0. Non-overlapping high quality paired end reads were retained for downstream analysis by linking them artificially with 15 Ns. High-quality sequences were taxonomically assigned using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Naïve Bayesian Classifier (version 2.9)34 with a bootstrap cutoff of 80%. PICRUSt (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States)35 was used to infer the abundance of metabolic pathways from 16 S rRNA gene sequencing data. The predicted functions (KOs) were collapsed into hierarchical KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathways using the categorize_by_function step provided in the PICRUSt pipeline.

Table 2.

PCR primers for amplification of V4 region of 16 S rRNA gene.

| v4L_BT517 | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTACGACGTGGTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA |

| v4L_13_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGGACTTCCAGCTGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_14_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCTCACAACCGTGGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_15_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCTGCTATTCCTCGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_16_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATATGTCACCGCTGGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_17_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTGTAACGCCGATGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_18_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATAGCAGAACATCTGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_19_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTGGAGTAGGTGGGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_20_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTTGGCTCTATTCGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_21_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGATCCCACGTACGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_22_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTACCGCTTCTTCGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_23_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTGTGCGATAACAGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

| v4L_24_R | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGATTATCGACGAGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT |

Plasma TMAO measurement

Ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) was used to measure plasma TMAO concentrations as described previously with minor modification36. Briefly, the UHPLC-MS/MS system consisted of an Acquity UPLC I-class sample mannager (Waters, Milford, MA), Acquity UPLC I-class binary solvent mannager, and a TSQ Quantum Ultra triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose, CA). For protein precipitation, plasma (50 µL) was combined with an internal standard (200 µL of d9-TMAO 0.5 µg/mL) in methanol. After centrifugation, 20 µL of supernatant was diluted with 100 µL of 75:25 acetonitrile:methanol and 5.0 µL of this mixture was injected onto the UPLC-MS/MS system. The standard curve ranged from 0.010–5.00 µg/mL (0.13–66.6 µM). The within-run and between-run precision (percent coefficient of variation) was <15%.

Assessment of atherosclerosis

At the end of each study, mice were euthanized, and the heart was removed just proximal to the aortic arch. The heart was cut transversely at the level of the atria and placed ventricle down into a tissue mold in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT compound) and stored at −20 °C until sectioning. Multiple cryosections at 10 μ thickness were taken of the aortic sinus and aortic root and stained for fat content with Oil-Red-O (ORO). Six sections from each heart were selected for image analysis, including the first section that contained the three leaflets of the aortic valve and the next 5 sections at 40 μ intervals along the aortic root distal to the valve over a total distance of 200 μ. The area of the plaque and the content of ORO was quantified by image analysis (ImageJ software) and calculated as an average of the area of plaque found in each of the 6 individual aortic valve sections taken for analysis37. Two animals from the negative control group and one of the transplanted animals died prior to obtaining samples for atherosclerosis evaluation.

Statistical Analyses

We used analysis of variance and Student’s t test to compare mean plaque size between groups. A random effects mixed model was used to examine the species main effect (with levels M. smithii, M. mazei, and M. blatticola, M. luminyensis, M. portucalensis, and control), the time main effect (day 2, 10, 30), and the species x time interaction Values are presented as mean ± SD, and those with a value of P < 0.05 were considered significant. Data analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

MA can colonize normal C57BL/6 mice guts and lower their plasma TMAO concentrations

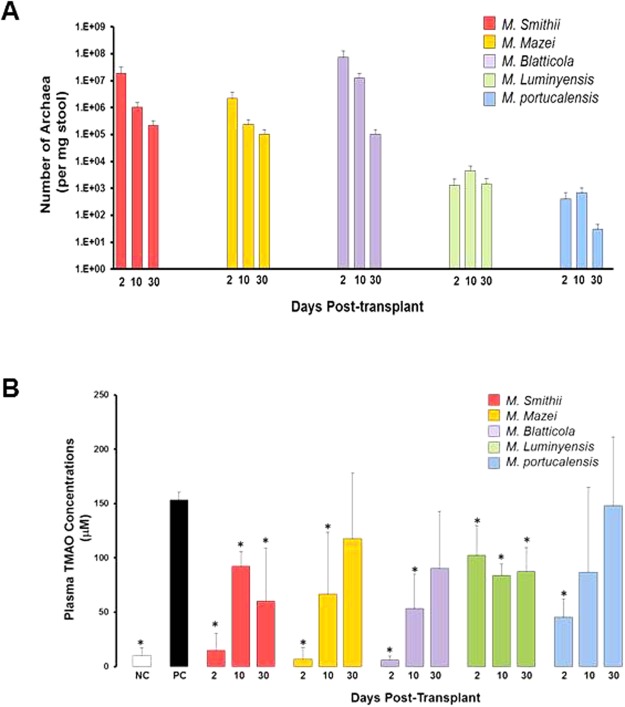

In an initial experiment, we screened five MA for colonization efficacy and TMAO lowering potential using C57BL/6 mice. M. smithii, M. mazei, and M. blatticola had the highest engraftment levels ranging from 1.9 × 107 to 7.4 × 107 copies/mg stool on day 2 post-transplant, which gradually decreased (1.0 × 105 to 2.2 × 105 copies/mg stool) on day 30 post-transplant (Fig. 1A). M. luminyensis and M. portucalensis had the lowest engraftment levels ranging from 0.4 × 103 to 1.3 × 103 copies/mg stool on day 2 post-transplant, which also decreased on the 30th day.

Figure 1.

MA can colonize normal C57BL/6 mice guts and lower their plasma TMAO concentrations. (A) Q-PCR analysis of fecal samples from C57BL/6 mice transplanted with one of five different representative gut- and non-gut MA, namely: M. smithii, M. mazei, M. blatticola, M. luminyensis, and M. portucalensis. Stool samples were collected at days 2, 10, and 30 post-transplantation. (B) Plasma TMAO concentrations in mock- and MA-transplanted C57BL/6 J mice collected at days 2, 10 and 30 post-transplantation. Mock-transplanted negative control mice (NC) only received regular water, whereas mock-transplanted positive control mice (PC) received high choline/TMA water, similar to MA-transplanted mice.

The plasma TMAO concentration was markedly elevated in the group of mice that were on the choline/TMA-supplemented water (positive control) compared to the negative control mice fed with regular water (153.6 ± 2.8 vs. 10.1 ± 7.0 μM, p < 0.001). On day 2 post-transplant, plasma TMAO concentrations were significantly lower in mice colonized with M. smithii (14.8 ± 15.7 μM, p = 0.003), M.mazei (6.9 ± 10.6 μM, p < 0.001), M. blatticola (5.9 ± 3.8 μM, p < 0.001), M. luminyensis (102.3 ± 27.3 μM, p = 0.03), and M. portucalensis (45.57 ± 16.8 μM, p < 0.01), compared to the positive control mice (Fig. 1B). TMAO concentrations showed a rebound increase from day 10 post-transplantation, which paralleled the decline in MA colonization levels.

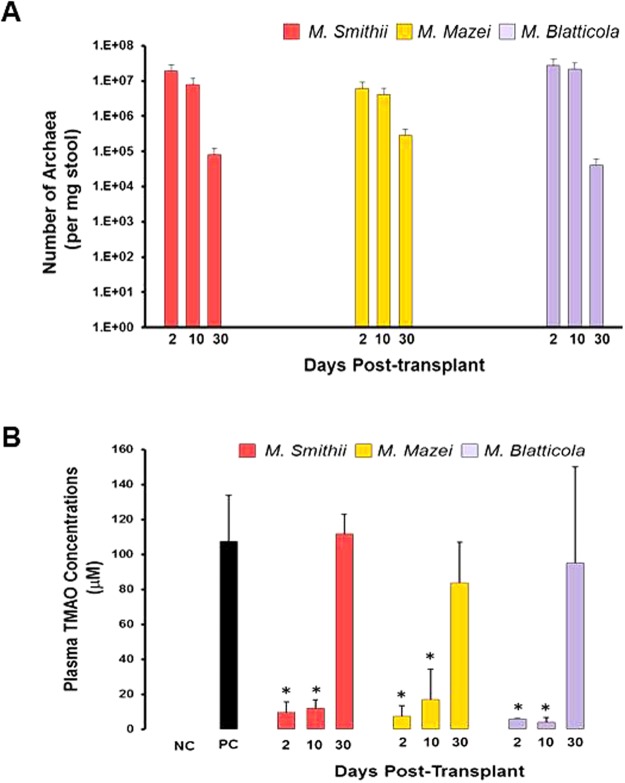

MA can colonize Apoe−/− mice guts and lower their plasma TMAO concentrations

Based on their performance in C57BL/6 mice, three of the best performing MA, M. smithii, M. mazei, and M. blatticola, were selected and tested in Apoe−/− mice. In general, engraftment of the 3 transplanted MA in Apoe−/− mice were similar to that obtained in C57BL/6 mice, ranging from 0.6 0 × 107 to 3.0 × 107 copies/mg stool on day 2 post-transplant (Fig. 2A). TMAO concentrations in mice colonized with M. smithii (9.5 ± 5.9 μM), M. mazei (7.4 ± 6.1 μM) and M. blatticola (5.8 ± 0.6 μM) were significantly lower on day 2 compared to positive control mice (98.5 ± 26.5 μM) (Fig. 2B). The plasma TMAO concentrations remained low up to 10 days post-transplantation. The group x time interaction was significant (p = 0.004), indicating that the pattern of TMAO across time differed by species.

Figure 2.

MA can colonize Apoe−/− mice guts and lower their plasma TMAO concentrations. (A) Q-PCR analysis of fecal samples from Apoe−/− mice transplanted with one of the 3 different MA, namely: M. smithii, M. mazei, and M. blatticola. Stool samples were collected at days 2, 10, and 30 post-transplantation. (B) Plasma TMAO concentrations in mock- and MA-transplanted Apoe−/− mice collected at days 2, 10 and 30 post-transplantation. Mock-transplanted negative control mice (NC) only received regular water, whereas mock-transplanted positive control mice (PC) received high choline/TMA water, similar to MA-transplanted mice.

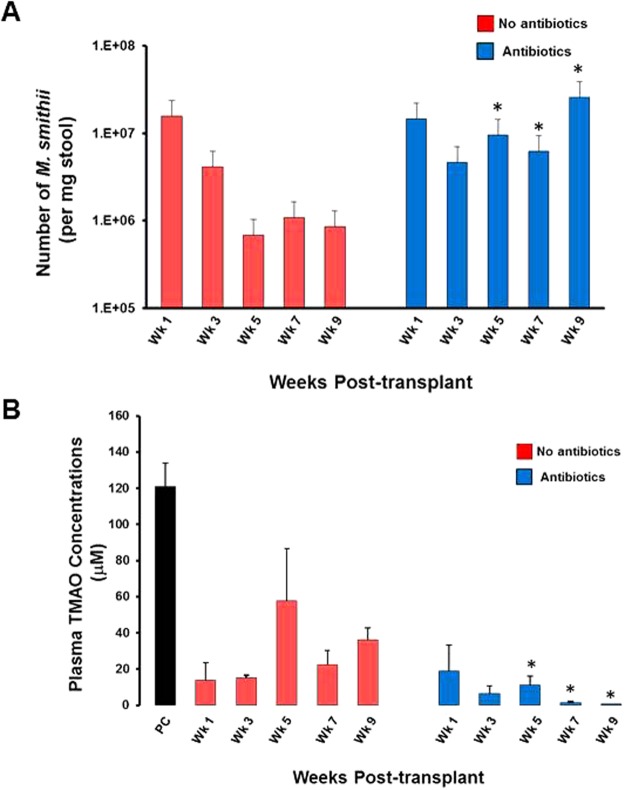

Repeated transplantation of Apoe−/− mice with M. smithii in presence of antibiotics leads to stable and high level gut colonization and diminishes the plasma TMAO concentrations

In order to improve gut colonization efficacies, we tested whether repeated transplantation with M. smithii leads to sustained high colonization level and persistent reduction in TMA concentration in Apoe−/− mice. In one group of repeatedly transplanted mice (n = 5/group) we also examined whether chronic suppressive antibiotic therapy further enhances colonization with M. smithii. As shown in Fig. 3A, repeated transplantation of M. smithii led to high engraftment levels throughout the study period. High and stable gut colonization with M. smithii led to lower average plasma TMAO concentrations (18.2 ± 19.6 μM) throughout the study period compared to that in positive control mice (120.8 ± 13.0 μM, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). The group of mice which were maintained on antibiotics, in addition to repeated transplantations, had a higher MA engraftment level compared to the mice not receiving antibiotics (1.3 ± 7.7 × 107 vs. 4.5 ± 6.4 × 106 average copies/mg stool) and lower average TMA concentrations (7.41 ± 9.38 vs. 29.1 ± 31.2 μM, p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Repeated transplantation of Apoe−/− mice with M. smithii in presence of antibiotics leads to stable and high level gut colonization and diminishes the plasma TMAO concentrations. (A) To maintain a high level of gut colonization with the MA, M. smithii, transplantation was repeated every 3 weeks for the duration of the study. A second group of mice (+Antibiotics) was also maintained on vancomycin and ampicillin, in addition to receiving repeated transplantations. Weekly blood and stool samples were collected from the mice for 9 weeks. Stool samples were analyzed by q-PCR for MA engraftment levels. (B) Plasma TMAO concentrations in mock- and M. smithii-transplanted Apoe−/− mice (±antibiotics) collected weekly for 9 weeks post-transplantation. Mock-transplanted positive control mice (PC) received high choline/TMA water, similar to M. smithii-transplanted mice, but not antibiotics.

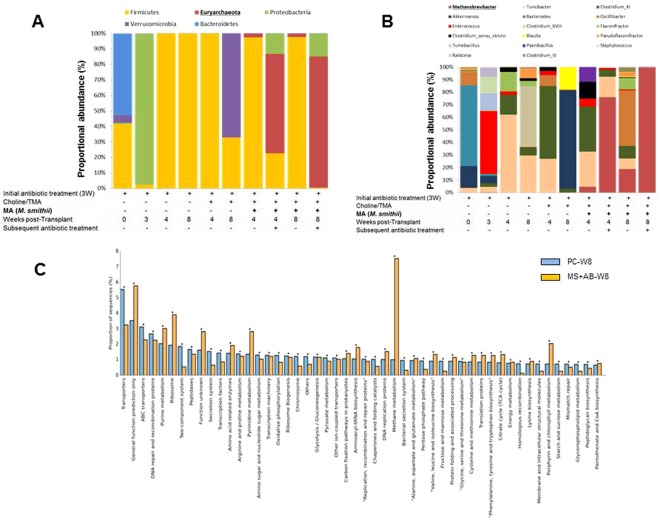

Antibiotic depletion of Firmicutes enhances gut colonization by M. smithii

16 S gut microbiome analysis of the stool samples from mice in the last experiment demonstrated that the baseline and pre-antibiotic microbiome profile of the mice consist of 53% Bacterioidetes, 43% Firmicutes, and 4.9% Verrucomicrobia (Fig. 4A). However, following the 3-week antibiotic treatment, the Bacterioidetes, Firmicutes and Verrucomicrobia levels decreased to 2.4%, 0.2%, and 0.1%, respectively, and Proteobacteria constituted the majority of the remaining bacteria that colonized in the gut (97.1%). In the negative control group, after stopping antibiotics, within 4 weeks, the Firmicutes returned and constituted the main surviving phylum (100%). Mice that were fed with Choline/TMA also showed 100% colonization by Firmicutes on week-4, but during the next 4 weeks, the level decreased to 32.8% with the return of Verrucomicorbia, which constituted 67.2% of the gut bacteria. Gut colonization levels with M. smithii were 2.4% and 2.2% in weeks 4 and 8, respectively in mice that were not on antibiotics, and 64% and 84% in weeks 4 and 8, respectively, in mice that received antibiotics.

Figure 4.

Antibiotic depletion of Firmicutes enhances gut colonization by M. smithii. Apoe−/− mouse gut microbiome characterization based on 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. Shown is the histogram of proportional changes in gut microbiota OTU abundance at the (A) phylum and (B) genus levels as measured for the different groups (NC, PC, No-antibiotics, antibiotic). (C) Metabolic potential of M. smithii-colonized mice compared to un-transplanted mice.

At the genus level, the untreated mouse microbiome was dominated by Bacteroides at the baseline, while Clostridium and Turicibacter trended higher among the remaining bacteria in antibiotic-treated mice (Fig. 4B). Choline/TMA supplemented mouse microbiome was dominated by Akkermansia, which was replaced by Clostridium and Turicibacter in M. smithii-colonized mice. There was a significant difference in the colonization levels of M. smithii between the antibiotic treated and untreated mice, and the proportional distribution of classes of bacteria varied significantly. Functional analysis using PICRUSt35 showed that purine and pyrimidine metabolism, methane metabolism, and “phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis pathways were active. (Fig. 4C).

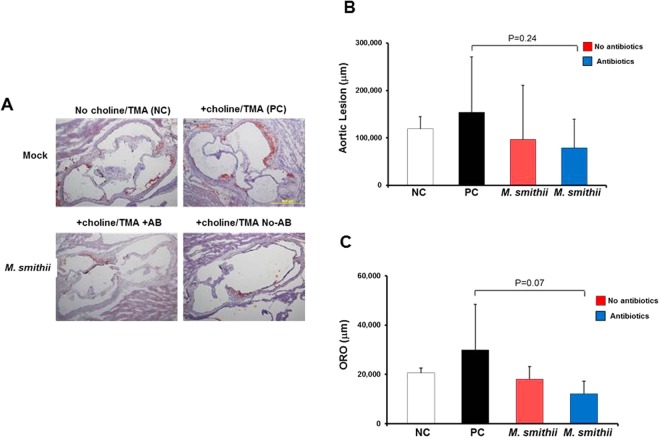

Stable M. smithii gut colonization trends towards attenuation of choline/TMA-enhanced atherosclerosis

When examined for aortic root plaque size by histology, M. smithii colonized mice trended to lower plaque burden (85,704 μm [95% CI 19,587–151,821]) than the positive control mice (153,690 μm [95% CI [70,058–237,321]), but the differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.34) (Fig. 5). We also noted a 52.2% mean reduction in ORO staining area in M. smithii colonized mice (14,283 μm [95% CI 4957–23,608]) compared to that of the positive control mice (29,870 μm [95% CI 18,074–41,666]), which was also not statistically significant (p = 0.10).

Figure 5.

Stable M. smithii gut colonization trends towards attenuation of choline/TMA-enhanced atherosclerosis. (A) Representative Oil-Red-O (ORO)/hematoxylin staining of aortic root sections from 19-week-old female Apoe−/− mice that were fed chemically defined chow (0.07% total choline), in the presence versus absence of choline/TMA (1.0% total choline; 1.2% TMA) provided in the drinking water, and either mock- or M. smithii-transplanted, as described in the Experimental Procedures. Scale bars, 500 μm. The AB-POS group was maintained on antibiotics in their drinking water for the duration of the experiment following transplantation. (B) Aortic root lesion plaque area and (C) ORO staining in the plaque area were quantified in 19-week-old female Apoe−/− mice from the indicated diet and M. smithii transplanted groups. Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the in vivo TMA-metabolizing efficacy of several gut and not-gut associated methyl-trophic methanoarchaea of the genera Methanomicrococcus (Methanomicrococcus blatticola); Methanosarcina (Methanosarcina mazei), Methanohalophilus (Methanohalophilus portucalensis), and Methanomassiliicoccus (Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis). The ability of all of these species to grow on TMA in culture has been previously demonstrated23,25,38,39. Also included in this study, was M. smithii, a member of Methanobrevibacter genus which is the most predominant methanoarchaea in the human gut. Unlike the other methanoarchaea used in this study, M. smithii is not known to grow on TMA in culture. However, a recent study demonstrated that many essential genes involved in methanogenesis, including methyltransferases are present and significantly up-regulated in vivo when M. smithii was co-colonized with a prominent human gut symbiont40.

We show that gut colonization with MA, consistently and significantly reduces plasma TMAO concentrations in two different mouse models that were maintained on a high choline and TMA diet. The reduction in plasma TMAO concentrations, in general paralleled the abundance of MA in the gut. We initially screened five species of MA isolated from gut and non-gut environments and noted that the colonization efficacy and the TMAO lowering efficacy is highest with M. smithii, a normal inhabitant of the human gut. Unlike M. smithii, the other indigenous human gut methanoarchaea, M. luminyensis, was very poor at gut colonization in mice and lowering blood TMAO levels. This observation is however, in accordance with the reports on low prevalence of M. luminyensis which is detected only in 4% of individuals, compared to that of M. smithii which has a high prevalence of nearly 96%19.

16 s rRNA sequencing showed that antibiotics, choline/TMA and M. smithii colonization led to distinct change in microbiome profile and functional changes in gene expression. Compared to Apoe−/− mice fed with high choline/TMA diet, mice colonized with M. smithii had 44.2% lower atherosclerotic burden and 52.2% reduced fat content in the atherosclerotic plaques, but these differences did not reach statistical significance possibly due to the small sample size.

Increased systemic exposure of TMAO is associated with atherosclerosis and major adverse cardiovascular events4–6. TMAO originates from the microbiota-dependent breakdown of dietary phosphatidylcholine to TMA. Functional studies have shown that TMAO decreases expression of bile acid transporters in the liver and reduces synthesis of bile acids from cholesterol4. TMAO also inhibits reverse cholesterol transport and promotes accumulation of cholesterol in macrophages through increasing cell surface expression of proatherogenic scavenger receptors CD36 and Scavenger Receptor A6, thus, creating foam cells that subsequently accumulate in the endothelial wall causing inflammation and plaque formation. Another mechanism related to atherosclerosis is the increase in thrombosis mediated by TMAO41.

It is therefore, not surprising that there is considerable interest in treatments designed to lower TMAO concentrations7. Targeting gut microbial production of TMA using a structural analog of choline, 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol, inhibits TMA formation and lowers TMAO concentrations in mice fed a high-choline or L-carnitine diet7. 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol inhibited choline diet-enhanced endogenous macrophage foam cell formation and atherosclerotic lesion development in Apoe−/− mice7. In this study, we took a different approach and aimed at depleting TMA as it is being formed by MA. In vitro studies have shown that certain MA can utilize TMA as a substrate for growth38. However, this is the first in vivo study that examines the utility of MA in decreasing plasma TMAO concentrations.

We used a logical step-wise approach including screening, discovery and validation. For our initial screening, we chose normal C57/BL6 mice to evaluate the gut colonization capability and TMAO lowering efficacy of five selected species of MA. Subsequently, we tested the TMAO lowering efficacy of the three top performing MA in Apoe−/− mice. In the final experiment, we examined the effect of repeated transplantation with M. Smithii, and chronic suppression of endogenous bacteria by antibiotics, on colonization efficacy, TMAO concentrations and atherosclerosis level in Apoe−/− mice.

Our initial study in C57BL/6 mice showed that all MA tested were able to colonized the gut and reduce TMAO concentrations irrespective of their original habitat, but with large inter-individual variations. Efficient gut colonization by M. smithii was evident, but the colonization level of the other human gut MA, M. luminyensis, was poor. In the second experiment, a significant reduction in plasma TMAO concentrations were also observed in Apoe−/− mice transplanted with M. smithii (90.4%), M. mazei (92.5%), and M. blatticola (94%) on the 2nd day, compared to non-transplanted control animals fed with high choline/TMA diet. Our initial experiments in both C57BL/6 and Apoe−/− mice revealed that, even after a 3-week-long antibiotic depletion of the gut bacteria, colonization was only transient with a single dose of MA. In a 3rd experiment, we show that repeated transplantations significantly improved the gut colonization levels, which was further improved by antibiotic suppression of endogenous gut bacteria. There was a corresponding sustained reduction in TMAO concentrations. 16 S sequencing analysis confirmed that maintaining the transplanted mice on antibiotics greatly enhances M. smithii engraftment, but depleted Firmicutes and enriched Proteobacteria.

We chose to test M. smithii because it is known to be the most predominant MA in the human gut. M. smithii thrives in the distal intestine through its versatility in consuming the fermentation products made by saccharolytic bacteria, and by its ability to produce surface glycans and adhesion-like proteins40. M. luminyensis also colonizes human gut, although at much lower levels compared to M. smithii19. In human gut, TMA-metabolizing MA depend on the gut microbiota for converting choline to TMA which serves as a carbon-source for MA. In return, MA facilitates the continuation of bacterial fermentation process in the gut by metabolizing and removing H2.

On a chow diet, Apoe−/− mice demonstrate a total cholesterol level >500 mg/dL, with fatty streaks first observed in the proximal aorta at 12 weeks of age, and fibrous plaques appearing at 20 weeks of age42. A Western diet43, or a choline-rich diet6, induce a marked increase in plaque size and aggressive plaque morphology. We found that gut colonization with M. smithii resulted in a tendency for reduced atherosclerosis burden in Apoe−/− mice fed with high choline/TMA diet. The results were not statistically significant, possibly due to small number of animals studied. In addition, we cannot exclude the possibility that factors other than TMAO contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, which were unmodified by this intervention44.

Since our data on the lowering of plaque characteristics were not statistically significant, either this study needs to be repeated in a much larger cohort of animals, or it could be concluded that lowering TMAO (as significant as our study demonstrates), does not lower TMAO-induced atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice.

We acknowledge that this is a pilot study in small number of animals and that the study could have benefited from measurement of TMA and choline concentrations; however, the study has a number of strengths. Strengths include: (a) first study to explore the utility of gut colonization by MA to lower plasma TMAO concentrations; (b) the evaluation of several candidate gut and non-gut MA in two mouse models; (c) the examination of single vs. repeated transplantation effect of MA; and, (d) the determination of MA engraftment efficiency after suppression of the endogenous gut microbiome.

While we do not know and did not investigate the factors that support increased engraftment level of MA in mice maintained on antibiotics, we speculate that there may be other bacteria and/or bacteria-derived factors that would either compete with or inhibit MA gut colonization. Clearly, the use of antibiotic in this study was to enhance gut colonization in our mouse model and facilitate the study of MA impact on blood TMAO levels, and not a recommended method to enhance the MA gut colonization in human. Future studies are needed to identify the exact mechanism and factors that support or compete with MA engraftment in human gut, and the consequence of increased MA abundance on the human host physiology and health.

To date, the impact of methanogens on human physiology and health is poorly understood. Association between MA and inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancers and obesity has been reported, however, there is no convincing evidence supporting the pathogenic properties of the MA, beyond occasional reports of constipation45,46. M. smithii has been shown to enhance energy retrieval by another sacharolytic bacterial species when co-transplanted into germ-free mice47. A study of fecal DNA extracts from patients with colorectal cancer, polypectomised, irritable bowel syndrome and control subjects found no significant association between these diseases and the presence of MA48. There is also no conclusive evidence that MA is associated with colon cancer49,50.

To summarize, our study shows that gut colonization with certain MA reduces plasma concentrations of TMAO. Among the MA tested, M. smithii, an endogenous human gut MA, was most effective in lowering plasma TMAO levels in Apoe−/− mice fed with high choline/TMA, and showed a tendency to attenuate atherosclerosis. The anti-atherogenic potential of the MA should be confirmed in studies using larger number of animals. The field of microbiome research is still nascent, but is evolving rapidly. Therapeutic use of specific toxin-degrading gut commensal microbes as probiotics to lower the levels of uremic toxins such as TMAO is a novel concept, but if proven effective, it will have a significant impact on cardiovascular disease and progression of chronic kidney disease. Safety of MA should be tested in pilot studies prior to launching efficacy studies in human subjects.

Acknowledgements

A.R. is a recipient of the Joseph M. Krainin, MD, Memorial Young Investigator Award from the National Kidney Foundation. D.S.R. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants 1U01DK099924-01, and 1U01DK099914-01. This publication was supported in part by Award Number UL1TR001876 from the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Sequencing and microbiome analysis was performed in the Nucleic Acids Research Facilities at Virginia Commonwealth University. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Stanly L. Hazen for reviewing this manuscript, assistance with experimental design and measuring TMAO concentration. We thank Ms. Rose Webb and The George Washington University Research Pathology Core Lab for assistance with tissue processing and histology.

Author Contributions

All authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. A.R and T.D.N. contributed equally to this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ali Ramezani and Thomas D. Nolin contributed equally.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jie Z, et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:845–857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slingerland AE, Schwabkey Z, Wiesnoski DH, Jenq RR. Clinical Evidence for the Microbiome in Inflammatory Diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:400–415. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koeth RA, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013;19:576–585. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang WH, et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1575–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, et al. Non-lethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine Production for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Cell. 2015;163:1585–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, et al. Prognostic value of choline and betaine depends on intestinal microbiota-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:904–910. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li XS, et al. Untargeted metabolomics identifies trimethyllysine, a TMAO-producing nutrient precursor, as a predictor of incident cardiovascular disease risk. JCI. Insight. 2018;3:1–18. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett BJ, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab. 2013;17:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craciun S, Balskus EP. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:21307–21312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215689109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu Y, et al. Carnitine metabolism to trimethylamine by an unusual Rieske-type oxygenase from human microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:4268–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316569111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koeth RA, et al. gamma-Butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab. 2014;20:799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolphin CT, Janmohamed A, Smith RL, Shephard EA, Phillips IR. Missense mutation in flavin-containing mono-oxygenase 3 gene, FMO3, underlies fish-odour syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:491–494. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayesh R, Mitchell SC, Zhang A, Smith RL. The fish odour syndrome: biochemical, familial, and clinical aspects. BMJ. 1993;307:655–657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6905.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dridi B, Henry M, Richet H, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Age-related prevalence of Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis in the human gut microbiome. APMIS. 2012;120:773–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2012.02899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Oufir L, et al. Relations between transit time, fermentation products, and hydrogen consuming flora in healthy humans. Gut. 1996;38:870–877. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.6.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pochart P, Dore J, Lemann F, Goderel I, Rambaud JC. Interrelations between populations of methanogenic archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in the human colon. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1992;77:225–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dridi B, Henry M, El KA, Raoult D, Drancourt M. High prevalence of Methanobrevibacter smithii and Methanosphaera stadtmanae detected in the human gut using an improved DNA detection protocol. PLoS. One. 2009;4:e7063–e7069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stams AJ. Metabolic interactions between anaerobic bacteria in methanogenic environments. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:271–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00871644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sowers KR, Ferry JG. Isolation and Characterization of a Methylotrophic Marine Methanogen, Methanococcoides methylutens gen. nov., sp. nov. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 1983;45:684–690. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.2.684-690.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahakian AB, Jee SR, Pimentel M. Methane and the gastrointestinal tract. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010;55:2135–2143. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sprenger WW, van Belzen MC, Rosenberg J, Hackstein JH, Keltjens JT. Methanomicrococcus blatticola gen. nov., sp. nov., a methanol- and methylamine-reducing methanogen from the hindgut of the cockroach Periplaneta americana. Int J Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000;50(Pt 6):1989–1999. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-6-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mah Robert A. Isolation and characterization ofMethanococcus mazei. Current Microbiology. 1980;3(6):321–326. doi: 10.1007/BF02601895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boone D, et al. Isolation and Characterization of Methanohalophilus portucalensis sp. nov. and DNA Reassociation Study of the Genus Methanohalophilus. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1993;43:430–437. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-3-430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casamayor EO, et al. Changes in archaeal, bacterial and eukaryal assemblages along a salinity gradient by comparison of genetic fingerprinting methods in a multipond solar saltern. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;4:338–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takai K, Horikoshi K. Rapid detection and quantification of members of the archaeal community by quantitative PCR using fluorogenic probes. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:5066–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.5066-5072.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muralidharan J, et al. Extracellular microRNA signature in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;312:F982–F991. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00569.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart JA, Chadwick VS, Murray A. Carriage, quantification, and predominance of methanogens and sulfate-reducing bacteria in faecal samples. Lett. Appl Microbiol. 2006;43:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caporaso JG, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fettweis JM, et al. Species-level classification of the vaginal microbiome. BMC. Genomics. 2012;13(Suppl 8):S17–S26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S8-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parikh HI, Koparde VN, Bradley SP, Buck GA, Sheth NU. MeFiT: merging and filtering tool for illumina paired-end reads for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. BMC. Bioinformatics. 2016;17:491–497. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1358-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon S, Lee B, Yoon S. CASPER: context-aware scheme for paired-end reads from high-throughput amplicon sequencing. BMC. Bioinformatics. 2014;15(Suppl 9):S10–S21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-S9-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langille MG, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ocque AJ, Stubbs JR, Nolin TD. Development and validation of a simple UHPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of trimethylamine N-oxide, choline, and betaine in human plasma and urine. J Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015;109:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Y, et al. Practical assessment of the quantification of atherosclerotic lesions in apoE(−)/(−) mice. Mol. Med Rep. 2015;12:5298–5306. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brugere JF, et al. Archaebiotics: proposed therapeutic use of archaea to prevent trimethylaminuria and cardiovascular disease. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:5–10. doi: 10.4161/gmic.26749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xun L, Boone DR, Mah RA. Control of the Life Cycle of Methanosarcina mazei S-6 by Manipulation of Growth Conditions. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 1988;54:2064–2068. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2064-2068.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samuel BS, et al. Genomic and metabolic adaptations of Methanobrevibacter smithii to the human gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10643–10648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704189104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu W, et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell. 2016;165:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddick RL, Zhang SH, Maeda N. Atherosclerosis in mice lacking apo E. Evaluation of lesional development and progression. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1994;14:141–147. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan YK, et al. High fat diet induced atherosclerosis is accompanied with low colonic bacterial diversity and altered abundances that correlates with plaque size, plasma A-FABP and cholesterol: a pilot study of high fat diet and its intervention with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) or telmisartan in ApoE−/− mice. BMC. Microbiol. 2016;16:264–277. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0883-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velasquez MT, Ramezani A, Manal A, Raj DS. Trimethylamine N-Oxide: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Toxins. 2016;8:326–337. doi: 10.3390/toxins8110326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aminov RI. Role of archaea in human disease. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2013;3:42–46. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di SM, Corazza GR. Methanogenic flora and constipation: many doubts for a pathogenetic link. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2304–2305. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samuel BS, Gordon JI. A humanized gnotobiotic mouse model of host-archaeal-bacterial mutualism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10011–10016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602187103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scanlan PD, Shanahan F, Marchesi JR. Human methanogen diversity and incidence in healthy and diseased colonic groups using mcrA gene analysis. BMC. Microbiol. 2008;8:79–87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Keefe SJ, et al. Why do African Americans get more colon cancer than Native Africans? J Nutr. 2007;137:175S–182S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.175S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nava GM, et al. Hydrogenotrophic microbiota distinguish native Africans from African and European Americans. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012;4:307–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]