Abstract

Biliary tracts cancers (BTCs) are a diverse group of aggressive malignancies with an overall poor prognosis. Genomic characterization has uncovered many putative clinically actionable aberrations that can also facilitate the prognostication of patients. As such, comprehensive genomic profiling is playing a growing role in the clinical management of BTCs. Currently however, there is only one precision medicine approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of BTCs. Herein, we highlight the prevalence and prognostic, diagnostic, and predictive significance of recurrent mutations and other genomic aberrations with current clinical implications or emerging relevance to clinical practice. Some ongoing clinical trials, as well as future areas of exploration for precision oncology in BTCs are highlighted.

Introduction

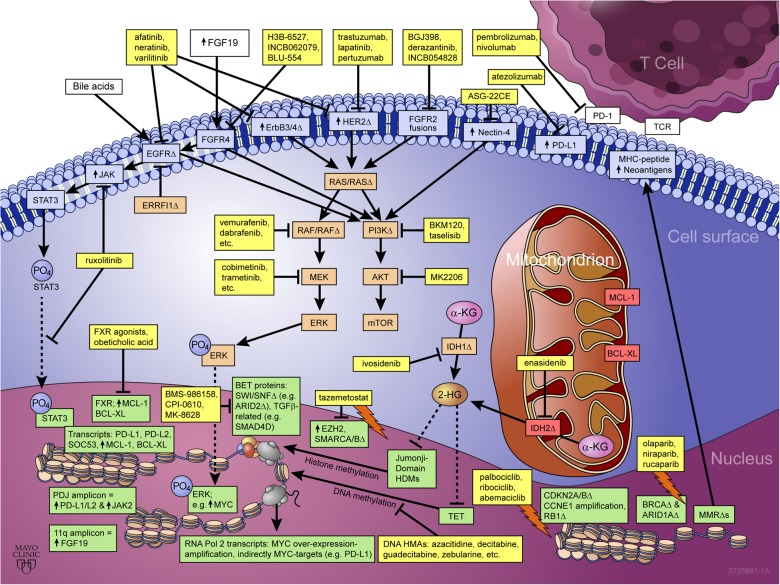

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) are a heterogeneous group of epithelial cell malignancies arising from distinct anatomical locations of the biliary tree (intrahepatic, perihilar, distal bile ducts or the gallbladder). BTCs are generally subtyped as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA), extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (eCCA), and gallbladder carcinoma (GBC). Although surgery remains the only curative treatment option for BTCs, 5-year survival rates remain low, largely due to the advanced nature of these cancers at diagnosis and their aggressive underlying pathogenesis.1 Gemcitabine combined with cisplatin has emerged as a standard-of-care regimen for patients with inoperable disease.2 In recent years, a growing number of genomic studies have begun to uncover the molecular underpinnings of BTCs and suggest many potential treatments (Fig. 1). However, it should be noted that due to the relatively low incidence of BTCs, many essential reports thus far have investigated small-to-moderate cohorts associated with inherent sampling size and other biases. Thus, caution is necessary in interpreting these studies and formulating broader conclusions. Nonetheless, genomic studies of BTCs are ushering in a new era of precision therapy, already playing an emerging role in the treatment and prognostication of BTCs.

Fig. 1.

Emerging role of precision medicine in biliary tract cancers. Yellow boxes highlight US FDA-approved drugs and drugs undergoing clinical investigation as reviewed, with arrows indicating pathway/target activation and blocked lines indicating pathway/target inhibition. BTC targets/pathways discussed are shown in color-coded boxes according to subcellular localization, blue = cell surface, orange = cytsolic, red = mitochondrial, and green = nuclear. “↑” denotes over-expression, “Δ” denotes copy number abbreation and/or point mutation, a lighting bolt symbol denotes a synthetic lethal interaction between drug(s) and target(s) listed

Biomarkers of response to PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors

Microsatellite-instability (MSI) is a hypermutation phenotype that occurs in cells with defective mismatch repair (MMR), resulting in a significant increase in non-silent mutations per genome and concomitant increase in neoantigen presentation. The MSI/MMR phenotype arises via germline (Lynch Syndrome3) or somatic mutations of MMR genes (MLH1, MLH3, MSH2, MSH3, MSH6, PMS1, PMS2, POLD1, or POLE),4 silencing of MLH1 gene expression through promoter hypermethylation,5 epigenetic inactivation of MSH2,6 mutations in the promoter of PMS2,7 or downregulation of MMR genes by microRNAs.8 As the most high-profile testament of the potential of biomarker-guided clinical trials in oncology to date, a series of five uncontrolled, single-arm, multi-center clinical trials investigating pembrolizumab, an anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor monoclonal antibody, in MMR-deficient (dMMR)/MSI-high (MSI-H) advanced solid tumors (N = 149) has recently led to the first “tissue/tumor-agnostic” treatment approved by the U.S. FDA.9 Eleven of the 149 patients enrolled in these studies had BTCs. This small subset of BTCs showed a 27% overall response rate (ORR) as defined by RECIST v1.1, with a duration of response ranging from 11.6 to 19.6+ months.9 The ORR for this entire cohort of dMMR/MSI-H cases across all solid tumor types (90 colorectal and 59 non-colorectal) was 40%. dMMR/MSI occurs across all BTC subtypes, most frequently in iCCA with a prevalence of 10, and 5% prevalence for eCCA and GBC.10 Although there is currently no FDA-approved diagnostic test for this indication (indicated independently of PD-L1 expression), approval is based upon use of an MSI or MMR biomarker. MSI and MMR tests have been used in clinical practice for decades as a prognostic test for colorectal cancer.11 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based measurement of the “Bethesda markers,” which include two monocucleotide and three dinucleotide repeats, is the “gold-standard” for MSI detection,12 and while immunohistochemistry for MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, PMS2, and MSH6) shows high concordance with PCR-based testing, cases of MSI with only missense mutations cannot be detected by immunohistochemistry. Tumor microdissection by a pathologist is critical for ensuring assessment of high tumor cellularity, as MSI diagnostics are insensitive below a purity of 20% tumor cells.

Beyond dMMR/MSI-H, tumor mutational burden (TMB) is emerging as a predictive biomarker for PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Higher TMB increases neoantigen presentation which promotes lymphocyte infiltration at the tumor periphery and microenvironment.13 Thus high TMB is associated with a higher likelihood of response to PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. A retrospective analysis of 151 solid tumor patients (primarily melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer) treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy reported that 42% (16/38) of solid tumor patients with high TMB [defined as >20 mutations/megabase (Mb) determined by sequencing 1.2 Mb (~0.04% of the genome) and extrapolating to the whole genome] had an objective response, while 31% (21/67) of solid tumor patients with intermediate TMB (defined as 6–19Δ/Mb) had an objective response, and 2/46 patients with low TMB (defined as 1–5Δ/Mb) had an objective response.14 Prevalence of hypermutation varies by cancer type, and a study of 239 paired tumor/normal BTCs (137 iCCA, 74 eCCA and 28 GBCs) showed that 6% (14/239) were defined as high TMB using a threshold of >11.13Δ/Mb, which corresponded to a median 641 non-silent mutations in this subset of hypermutated BTCs.15 10 of the 14 high TMB cases identified in this study were iCCAs (7%; 10/137), while two cases were eCCA (3%; 2/74) and two were GBCs (7%; 2/28). The remaining 94% of cases were defined by a significantly lower TMB <7.03 Δ/Mb and corresponded to a median number of non-silent mutations of 39, 35 and 64 for iCCA, eCCA and GBC, respectively.

The prevalence of PD-L1-positivity across BTCs is much higher than that of dMMR/MSI-H tumors, with clinically-actionable positively estimated to be at least 30–46%.16,17 Lower estimates of prevalence have likely emerged due to application of more stringent thresholds to define positivity, and the multiple assays used to define PD-L1 positivity, while none have been adopted as standard clinical practice. Multiple clinical trials investigating PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors specifically in BTCs are now ongoing including monotherapy trials (nivolumab, NCT02829918), and chemotherapy combinations evaluating gemcitabine and cisplatin (pembrolizumab, NCT03260712; nivolumab, NCT03101566) (Table 1). In the fully-enrolled but ongoing KEYNOTE-028 study of monotherapy pembrolizumab (NCT02054806), 42% (37/89) of the BTC patients screened were defined as PD-L1-positive tumors utilizing a threshold of ≥1% of tumors cells or infiltrating lymphocytes expressing PD-L1. The preliminary ORR for the 24 BTC patients enrolled was reported at 17% (all durable PRs with treatment ongoing 40–42+ weeks at the time of reporting), with a disease control rate (DCR) of 33% (8/24).18

Table 1.

Highlighted ongoing clinical trials evaluating biliary tract cancers

| Target(s) | Investigated drug(s)/arm(s) | Enrollment criteria | National Clinical Trial (NCT) identifier | Putative precision oncology application for BTCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1 | nivolumab monotherapy | PD-L1-positive BTCs | NCT02829918 | PD-L1-positive BTCs, LELCC |

| PD-1 + cytotoxic chemo | (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) with gemcitabine + cisplatin | PD-L1-positive BTCs | NCT03101566, NCT03260712, | PD-L1-positive BTCs, LELCC |

| pan-FGFR1/2/3 | INCB054828 monotherapy | FGFR2 translocations | NCT02924376 | FGFR2 translocations |

| pan-FRFR1/2/3 | ARQ087/derazantinib monotherapy | iCCA or combined HCC/CCA with FGFR2 translocations | NCT03230318 | FGFR2 translocations |

| FGFR4 | H3B-6527 or INCB062079 monotherapy | Unselected CCA | NCT02834780, NCT03144661 | FGF19 amplification |

| IDH1 | ivosidenib monotherapy versus placebo | IDH1-mutant CCA | NCT02989857 | IDH1-mutant CCA |

| HER2 | trastuzumab + pertuzumab | BTCs with HER2 amplifications, over-expression, or activating mutations | NCT02091141 (one arm of “My Pathway” Study) | BTCs with HER2 amplifications, over-expression, or activating mutations |

| pan-HER + /- SERD or cytotoxic chemo | niratinib monotherapy, niratinib + fulvestrant or niratinib + paclitaxol | HER2, ERBB3, EGFR-mutated or EGFR-amplified BTCs | NCT01953926 | HER2, ERBB3, EGFR-mutated or EGFR-amplified BTCs |

| pan-HER + cytotoxic chemo | afatinib + capecitabine | Unselected BTCs | NCT02451553 | ERBB3- and ERBB4-alterations |

| pan-HER | ASLAN001/varlitinib montherapy | Unselected BTCs | NCT02609958 | ERBB3- and ERBB4-alterations |

| pan-HER + cytotoxic chemo | ASLAN001/varlitinib with gemcitabine + cisplatin | Unselected BTCs | NCT02992340 | ERBB3- and ERBB4-alterations |

| pan-HER + cytotoxic chemo | ASLAN001/varlitinib + capecitabine versus capecitbine | Unselected BTCs | NCT03093870 | ERBB3- and ERBB4-alterations |

| Bromodomain/BET Proteins | BMS-986158 | Multiple advanced solid tumors, unselected | NCT02419417 | MYC activation and/or amplification |

| Nectin-4 | ASG-22CE | Nectin-4 expressing solid tumors | NCT02091999 | GBCs evaluated for Nectin-4 expression, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mutated BTCs |

AKT proto-onogene C-Akt, BET bromo- and extra-terminal domain faimly, BTCs biliary tract cancers, CCA cholangiocarcinoma, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, ERBB3 human epidermal growth factor receptor 3, ERBB4 human epidermal growth factor receptor 3, FGF19 fibroblast growth factor 19, FGFR1/2/3/4 fibroblast growth factor receptor 1/2/3/4, GBCs gallbladder cancers, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, iCCA intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, IDH1 isocitrate dehydrogenase 1, LELCC lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, MYC proto-oncogene C-Myc, PD-1/PD-L1 programmed cell death protein/ligand 1, PI3K phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, SERD selective estrogen receptor downregulator

A subset of lymphomas, triple-negative breast cancers, and Epstein Barr Virus-positive gastric cancers are associated with genomic amplifications of a region of chromosome 9 containing PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2 loci termed the PDJ amplicon.19–21 These malignancies harboring the PDJ amplicon exhibit increased levels of PD-1 ligand and JAK2, while JAK2 inhibition was shown to decrease PD-1 ligand expression. A rare BTC subtype known as intrahepatic lymphoepithelial-like cholangioncarcinoma (LELCC), frequently associated with Epstein Barr Virus infection, and a higher prevalence in Asia, is reported to express high levels of PD-L1.22 It is compelling to speculate that LELCC cases may also harbor the PDJ amplicon. PD-L1-positive BTCs are clear candidates for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy, although a role for JAK2 inhibition in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy is also intriguing to consider for this subset of BTCs. A phase 1 study exploring this concept with combined pembrolizumab and JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib in triple-negative breast cancer has been initiated (NCT03012230).

FGF signaling aberrations

FGFR2 aberrations are almost exclusively observed in iCCA, and occur at a frequency of approximately 15% with the vast majority of FGFR2 aberrations being fusions and thus also amenable to clinical detection by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) break-apart assays.23 FGFR2 rearrangements are associated with increased overall survival (OS) in the post-resection setting (median 123 months vs. 37 months for cases without FGFR2 rearrangements).24 Patients with FGFR aberrations may have superior OS with FGFR-targeted therapy as compared to standard regimens.25 FGFR2 fusions activate MAPK signaling and typically do not co-occur with KRAS/BRAF mutations.23,26 BGJ398, a pan-FGFR small molecule inhibitor with 0.9, 1.4, and 1.0 nM potency for FGFR1/2/3 respectively in cell-free assays and >40-fold selectivity over FGFR4,27 has been studied in a phase 2 trial in advanced CCA patients resistant to frontline gemcitabine-based therapies.28 In 61 patients (N = 48 FGFR2 fusions, N = 8 FGFR2 mutations, N = 3 FGFR2 amplifications; with >1 type of FGFR2 aberration detected in 3 patients) the ORR, all partial responses (PRs), was 15%, with 75% of patients experiencing some disease control and a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 5.8 months. Four patients carried FGFR3 amplifications but none responded to BGJ398. Dose modifications were required for many patients, although AEs were mostly reversible. The most common AE was hyperphosphatemia (72%), with 25% of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 hyperphosphatemia.29 Hyperphosphatemia may be an on-target effect related to FGF23-regualted phosphate homeostasis.30,31 INCB054828, a pan-FGFR1/2/3 inhibitor with half-maximal activity of 3–50 nM in FGFR-dependent cell viability assays with >30-fold selectivity over FGFR-independent cell lines, has reported preliminary clinical activity in a small cohort of CCA patients,32 and has now progressed into phase 2 development (NCT02924376). ARQ087 (derazantinib) is a pan-FGFR inhibitor which inhibits FGFR2 most potently, with 4.5, 1.8, 4.5, and 34 nM potency for FGFR1/2/3/4, respectively in cell-free assays.33 A phase 1/2 study of ARQ087 (derazantinib) in advanced solid tumors reported only 5% grade 1 hyperphosphatemia.34 An expanded FGFR2-abberrant CCA cohort (N = 35) from this study reported a PR rate of 20% (6/35) and 49% stable disease (17/35). Abnormal LFTs and asthenia were observed in 20% of this cohort with 6% being grade 3/4.35 Based on this preliminary clinical activity, a single-arm phase 3 study of derazantinib in refractory iCCA with FGFR2 fusions is ongoing (NCT03230318).

Development of FGFR2 therapies is currently challenged by primary resistance and often limited response durability. Acquired resistance to FGFR2-targeted therapy via concordant evolution has been reported to manifest as mutations in the kinase domain of FGFR2 affecting drug binding.36 Using a liquid biopsy approach to assess circulating cell-free DNA,37 three FGFR2 fusion iCCA patients responding to BGJ398 acquired a V564F mutation at the time of progression, although two patients also acquired several additional polyclonal FGFR2 mutations exclusive to progression. Subsequent use of alternative FGFR2 inhibitors may lead to responses after progression, analogous to EGFR or ALK inhibitors in lung cancer.36 Additionally, divergent evolution mechanisms, such as PTEN aberrations, may also play a role in acquired resistance to FGFR2-targeted therapies.36 Thus, therapeutic combination strategies targeting FGFR2 and PTEN/PI3K/AKT may be speculatively intriguing to increase response duration, and/or overcome primary resistance in some FGFR2 fusion cases with co-occurring PTEN/PI3K alterations.

Amplicons of chromosome 11q containing of FGF19, an exclusive ligand of FGFR4 activating MAPK and JNK signaling in hepatocytes,38,39 have been reported in CCA.40 FGF19 amplification has been proposed as a predictive biomarker for sorafenib response in hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC),41 despite a lack of relevant FGFR inhibition by sorafenib, suggesting relevance of downstream sorafenib inhibition of RAF1/BRAF in this context. Sorafenib monotherapy has shown limited activity in advanced iCCA with PFS of 2.3–3.2 months,42,43 although fourth line sorafenib treatment of a single CCA case was reported to yield OS >4 years,44 suggesting the possibility that a rare underlying genomic context of CCA might benefit from sorafenib. Several FGFR4 inhibitors are now being evaluated clinically. H3B-6527 and INCB062079 are being investigated in phase 1 trials including CCAs (NCT02834780 and NCT03144661, respectively), while BLU-554 is being investigated in a phase 1 evaluating HCC only (NCT02508467).

Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations

IDH point mutations result in high-level accumulation of the oncometabolite 2-hydroxygluterate which inhibits enzymes that utilize alpha-ketogluterate as a cofactor, such as DNA methyltransferase TET2 and Jumonji C domain containing histone demethylases, leading to DNA and histone hypermethylation, respectively, and resultant dysregulation of gene expression.45,46 IDH mutations occur mostly in iCCA at ~20% frequency.47,48 IDH1 mutations occur primarily at the R132 codon and are most frequent, although IDH2 mutations at the R172 codon occur at ~half the frequency of IDH1R132Δ point mutations. Conflicting results have been reported for the prognostic significance of IDH mutations.48–50 The initial target population for clinical trials of IDH inhibitors is unresectable and/or metastatic disease, and prognostic significance may vary based on the precise clinical setting. In addition to disease presentation considerations, we speculate that the pathogenesis and prognostic impact of IDH mutations is likely modulated by co-occurring driver mutations. AG-221 (enasidenib) is now approved for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with IDH2 mutations, although enasidenib has not yet been tested in CCA. AG-120 (ivosidenib) showed somewhat promising clinical activity in preliminary studies with an ORR 6% and DCR of 62%. A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial with PFS as the primary endpoint is currently investigating ivosidenib in IDH1-mutant BTCs (NCT02989857). Hypomethylating agents (HMAs) such as azacitidine are de facto standard-of-care therapies for elderly AML unfit for induction therapy, and a clinical trial evaluating azacitidine in combination with enasidenib or ivosidenib in IDH-mutant AML is ongoing (NCT02677922). An HMA and IDH inhibitor combination may have utility in CCA based on analogous scientific rationale that HMAs will universally synergize with IDH inhibitors in reversing pre-established aberrant DNA methylation.

ErbB/HER pathway alterations

Multiple aberrations within the ErbB/HER signaling pathway have been described in BTCs, including ERBB1/EGFR mutations and amplifications, ERRFI1 mutations, ERBB2/HER2, ERBB3, and ERBB4 amplifications and mutations, while HER signaling is the most frequently mutated pathway in GBC. EGFR amplifications occur in 19–31% of iCCA/eCCA and are associated with poor prognosis,51,52 while somatic EGFR mutations were reported in 4% (3/51) of GBC.53 A phase 3 study of erlotinib added to gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in advanced BTCs unselected for ErbB/HER pathway aberrations failed to show an improvement in PFS over the control arm.54 A mutation in ERRFI1 (E384X), a direct inhibitor of EGFR, was identified in an iCCA case which responded rapidly to erlotinib.55 ERRFI1 has not been broadly evaluated, thus incidence and prognostic significance are unknown. HER2 gene amplifications and mutations are most prevalent in GBC and eCCA (10–15%), and are less common in iCCA.25,56 Prognosis for HER2 aberrations are unknown for BTCs, but are well known to have aggressive phenotypes in breast and gastric cancers. Currently, only one case series has been published for HER2-targeted therapy (trastuzumab, lapatinib, or pertuzumab) in BTCs (N = 9 GBCs; N = 5 iCCAs).53 Amongst the GBCs with HER2 aberrations evaluated, responses included one complete response, four PRs, and three stable disease, with a median duration of response of 40 weeks (8+ to 168 weeks, with three patients continuing to respond at the time of this report), while there were no radiological responses amongst the 5 iCCAs with HER2 aberrations evaluated. The multi-arm, biomarker-driven “My Pathway” study (NCT02091141) includes a trastuzumab plus pertuzumab arm evaluating BTCs with HER2 amplifications, over-expression, or activating mutations. ERBB3 mutations occurred in 12% (6/51) of BTCs, while ERBB4 mutations occurred in 4% (2/51).53 Pan-HER inhibitors such as afatinib, neratinib and varlitinib may play a role in ERBB3 and ERBB4 altered BTCs where more selective EGFR or HER2 inhibitors are not applicable. Afatinib is being assessed in an unselected phase 1 trial (NCT02451553). The investigational pan-HER inhibitor ASLAN001 (varlitinib) is being evaluated in a single-arm monotherapy study (NCT02609958), in a gemcitabine and cisplatin single-arm combination study (NCT02992340), and in a randomized phase 3 comparing varlitnib plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone (NCT03093870), all actively enrolling BTCs specifically without HER biomarker selection. Neratinib is being investigated as monotherapy and combined with fulvestrant or paclitaxel in an open-label efficacy study of HER2, ERBB3, or EGFR-mutated/-amplified solid tumors including BTCs (NCT01953926).

MAPK signaling

ErbB family receptors often operate through MAPK signaling, while mutations in MAPK signaling also occur in BTCs. KRAS mutations are the most common mutations in iCCA with a prevalence of ~19% but also occur across all BTC subtypes,57 and are associated with a poor prognosis.58 Targeting KRAS directly has proven difficult, thus strategies for targeting KRAS-mutant BTCs require further efforts. BRAF mutations occur in 3–5% of iCCA cases, although no clinical trial has assessed a BRAF inhibitor in CCA. MEK inhibitors have shown some limited single-agent clinical activity in BTCs.59 Several clinical trials are evaluating PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in combination with BRAF/MEK inhibitors in solid tumors such as colorectal and melanoma (NCT02788279, NCT02902029, NCT02858921, NCT01988896) based on data demonstrating MEK inhibition increases antigen presentation,60 with preliminary safety and activity reported.61 Based on the aforementioned single-agent PD-L1 responses in BTCs, relevance of MAPK signaling, activity of single-agent BRAF and MEK inhibitors, and demonstrated safety of the triplet combination in solid tumors, such combination(s) are logical to investigate in PD-L1-positive BTCs. Preclinical data suggests that PI3K-axis signaling inhibition with an AKT inhibitor can overcome acquired resistance to MEK inhibition in CCA.62 Thus, MEK and AKT inhibitor combinations in BRAF-mutant iCCA, and MEK, AKT, and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor triplet combinations in PD-L1-positive BTCs can be envisioned.

MET

High c-Met expression was observed in 12% of iCCA and 16% of eCCA and portends a poor prognosis, while MET amplifications are observed in 2–7% BTCs.63 Cabozantinib, a multi-kinase small molecule inhibitor that potently inhibits MET64 and is FDA-approved for advanced renal cell carcinoma and thyroid cancer, showed limited activity and significant toxicity in a study of unselected CCA, and response did not correlate with MET expression.65 However, MET amplification may be a more potent driver than MET expression.

PI3K/AKT/mTOR

Mutations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway frequently occur in eCCA (40%) and iCCA (25%), including FBXW7, PI3KCA, PTEN, NF1, NF2, PIK3R1, STK11, TSC1, and TSC2, and are associated with a worse prognosis.58,66 Mutations in PIK3CA are frequent in GBC (8–13%).57,67 PI3K/AKT/mTOR often signals downstream of ErbB/HER and preclinical studies suggest activity of PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibition in BTCs,68,69 although clinical studies are scarce. PI3K inhibitors in clinical development such as BKM-120 and taselisib may be relevant to BTCs. A clinical study of AKT inhibitor MK2206 was terminated due to futility.70 While PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitor monotherapy may have clinical utility for a subset of BTCs with pathway alterations, further development of PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors will require biomarker selection of patients, and combination strategies that consider co-occurring drivers (e.g., IDH mutations frequently occur with PIK3CA mutations), as well as acquired resistance (e.g., combination with MEK inhibitors in BTCs cases with aberrant MAPK signaling were acquired resistance may emerge via PTEN/PI3K62). Nectin-4, a cell adhesion molecule with diverse functions, was over-expressed in 63% (43/68) of GBC cases, while activation of PI3K/AKT was involved in the oncogenic function of Nectin-4 and PI3K inhibitors impaired Nectin-4-mediated GBC proliferation and motility.71 Thus, evaluation of Nectin-4 expression in PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mutated cases could be considered. A phase 1 study of a Nectin-4 antibody drug conjugate ASG-22CE72 is enrolling solid tumor patients with confirmed Nectin-4 expression (NCT02091999).

Rb-cell cycle dysregulation

CDKN2A/B genes are frequently mutated or amplified in iCCA (7–27%),25,73 eCCAs (17–47%)25,26 and GBC (19–26%),25,74 while silencing via promoter methylation is also observed in BTCs.74,75 In unresectable BTCs, the joint status of CDKN2A and p53 has been associated with a poor prognosis.76 CCND1/3 mutations are observed across all BTCs (4–14%), as well CCNE1 mutations/amplifications (4–5% in eCCA/GBC) and RB1 mutations (1–7%).15 CDKN2A is a well-known inhibitor of CDK4/6 and MDM2. Three CDK4/6 inhibitors are now FDA-approved for use in breast cancer treatment (palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib) that could be considered for BTCs.

Genome stability/DNA repair

Mutations of p53 are common across all BTCs (18–43%) and portend a poor prognosis.58,73,77 p53 mutations should be evaluated with precisely defined recurrent co-mutations using unbiased functional studies to identify potential therapeutic strategies. MDM2 mutations occur across all BTCs at 5–7%.15 BRCA1/2 mutations occur at 1–7% across BTCs (most frequently BRCA2 in GBC) and are candidates for PARP inhibition, which is synthetic lethal with BRCA mutations (olaparib, niraparib and rucaparib are FDA-approved for ovarian and breast cancer indications). A study reporting on 18 BRCA1/2-mutated CCAs found that 28% (5/18) carried germline mutations.78 Sustained responses to PARP inhibitors have been reported for BTCs.78,79 Additionally, commonly-occurring ARID1A mutations (see subsequent section on chromatin modifiers) are also reported to be synthetic lethal with PARP inhibition.80

Chromatin modifiers

In addition to the aforementioned IDH mutations, additional chromatin-modifying enzymes are recurrently mutated or altered by copy number aberrations in BTCs (alterations in epigenetic regulators occur in about one-third of BTCs), including ARID1A (11–36% in all BTCs; most frequently iCCA), ARID1B (5%; eCCA), ARID2 (4–18%; all BTCs, most frequently GBC), KDM4A (7%; GBC), KDM5D/-6A/-6B and UTY (1–4%; iCCA/eCCA), TET1/2/3 (5–11%; iCCA/GBC), PBRM1 (7–21%; iCCA/GBC), SMARCAD1/A2/A4 (1–3% each; iCCA/eCCA) and KMT2D/MLL2 and KMT2C/MLL3 (2–11%; all BTCs, most frequently GBCs-), ASXL1 (2–3%; iCCA/eCCA), as well as the deubiquitinating enzyme BAP1 (8–32%; iCCA, less frequently in eCCA), which while not a direct chromatin modifier is associated with a DNA hypermethylation phenotype in iCCA and other tumor types.15,26,58,73,81,82 Promoter DNA methylation of at least one tumor suppressor gene occurs in 85% of CCA cases.83 Additionally, novel non-coding promoter mutations have been reported to be associated with histone methylation (H3K27me3) modulation of CCA.84 Using a novel method named FIREFLY, for finding regulatory mutations in gene sets with functional dysregulation, to identify and define gene sets with altered transcription factor binding due to promoter mutations, researchers identified four gene sets in CCA, two of which contained subsets of target genes epigenetically silenced by the PRC2 complex via H3K27me3 in specific contexts. CCA was also defined by two distinct DNA hypermethylation phenotypes, with one subgroup showing concurrent down-regulation of DNA demethylation enzyme TET1 and upregulation of histone methyltransferase EZH2 suggesting an epigenetic role in establishing the DNA hypermethylation phenotype of this subgroup, while the other subgroup had IDH and/or BAP1 mutations.84 EZH2 inhibitors are now in clinical development (e.g., tazemetostat for some EZH2, SMARCB1, or SMARCA4-mutated cancers, NCT03213665) and could be considered for the EZH2/TET1 hypermethylated subgroup, or for SMARCA/B-mutated BTCs. DNA hypermethylation alone is not typically a sufficient driver or vulnerability of BTCs in and of itself, although it is compelling to speculate that HMAs could form the backbone of combination therapies for hypermethylated CCAs. For example, in a study of 260 Japanese BTC cases, BAP1 mutations most commonly occurred with FGFR2 fusions,15 thus FGFR2-targeted therapy could be investigated in combination with a HMA in patients with these co-occurring mutations. Recurrent mutations in SWI/SNF chromatin modifying complex components (ARID1A/B, ARID2, PBRM1, and SMARCA2/A4/AD1), as well as mutations in TGFβ-related genes [most frequently SMAD4 (4–10% across BTCs), but also less frequent mutations in TGFBR1/2, ACVR2A and FBXW7], are known to upregulate MYC, and MYC amplification in BTC appears to be mostly mutually exclusive with alterations in TGF-β and SWI/SNF signaling components, suggesting synonymous function(s).15 Thus, BET inhibitors, which block MYC transcription by preventing chromatin-dependent signal transduction to RNA polymerase 2,85 represent a compelling monotherapy strategy to target BTCs with activated/amplified MYC, and could speculatively form the backbone of combination strategies for BTCs with MYC activation and/or amplification. MYC regulates expression of PD-L1, while BET inhibitors were reported to down-regulate PD-L1 expression, which may have implications as immunotherapy or for immunotherapy-based combinations.86 There are several BET inhibitors currently being investigated in clinical trials, e.g., BMS-986158 in advanced solid tumors (NCT02419417), CPI-0610 in various myeloid malignancies (NCT02158858), and MK-8628 in hematological malignancies (NCT02698189).

Apoptosis

Anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-XL and MCL-1 are both thought to have underlying biological relevance in BTCs, while BCL-2 was not expressed in normal or malignant biliary epithelium.87 MCL-1 is frequently amplified in iCCAs (16–21%),58,73 and is also overexpressed via epigenetic silencing of the SOCS3 promoter by DNA hypermethylation,88 and upregulated by bile acids downstream of EGFR.89 SOCS3 levels are inversely correlated with STAT3 phosphorylation levels via a feedback loop regulated by Janus kinases that control expression of both MCL-1 and BCL-XL. In another preclinical study, FXR agonists were shown to have the capacity to down-regulate BCL-XL via inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation,90 and would therefore also have the capacity to down-regulate MCL-1. Thus HMAs, JAK inhibitors and FXR agonists all represent compelling therapeutic strategies in cases of MCL-1 over-expression, possibly including amplifications, as well as in apoptosis-targeting combination therapies. There are several HMAs and JAK inhibitors FDA-approved for other indications (and several additional candidates in clinical testing), while FXR agonist obeticholic acid is FDA-approved for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis, and several FXR agonists are also undergoing clinical investigation for primary scelerosing cholangitis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Consideration of co-mutations/comprehensive genomic-epigenomic landscapes

It will be absolutely critical to move beyond targeting individual mutations to advance precision oncology in BTCs, especially for more indolent drivers such as FGFR2 fusions and IDH mutations that co-operate with additional mutations, copy number aberrations, or epigenomic alterations. In BTCs, mutations in epigenetic regulators often occur with growth-promoting alterations, such as the aforementioned example of FGFR2 aberrations with BAP1 mutations, and KRAS, EGFR, or PIK3CA with IDH mutations.15 Thus therapeutic strategies that target both drivers, such as combination of an HMA with an FGFR2 inhibitor, or RAF, EGFR, AKT inhibitors with IDH inhibitors are compelling in these contexts, respectively. In one study, all 22 KRAS-mutant CCAs evaluated co-occurred with CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation, suggesting that a MAPK pathway inhibitor with a CDK4/6 inhibitor is a compelling combination strategy for KRAS-mutant CCA with epigenetically silenced CDKN2A.91 As highlighted herein, iCCA, eCCA, and GBC show unique prevalence for specific mutations, although the basis for this is unknown. Some researchers have proposed that differences in mutational prevalence are related to differences in embryonic origin, and it has also been proposed that micro-environmental exposure based on differences in tissue function may also contribute to prevalence differences. Thus, combinations should also be considered and designed in a tissue/BTC-subtype-specific manner.

Liquid biopsy/circulating cell-free DNA detection in diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and surveillance

As exemplified by the aforementioned study detecting FGFR2 mutations,36 liquid biopsy represents a powerful approach for discovering mechanism(s) of drug resistance, and monitoring tumor evolution analogous to what is currently performed for EGFR mutations in lung cancer.92 Liquid biopsy is suitable for identifying clinically-actionable alterations, and there is a high concordance between tissue and plasma measurements.93 Liquid biopsy is easy to implement and non-invasive, and thus it will be used more and more in the precision oncology setting. Intrapatient tumor sample heterogeneity has necessitated multi-region sequencing previously, although liquid biopsy yields a uniform, quantitative plasma signal which represents an advantage in detecting intrapatient tumor heterogeneity as well. Physicians and patients will not, and often cannot, extensively/serially biopsy, thus liquid biopsy will be a critical precision oncology tool by facilitating serial sample collection for biomarker discovery, treatment monitoring, and disease surveillance in BTCs.

Preclinical models

Beyond consideration of individual clinically actionable mutations, further progress will be largely dependent on developing treatment strategies to address recurrent co-mutations and ultimately global genome profiles. Preclinical models for investigating co-mutations, and potentially even more complex precisely-defined genomic context(s), such as comprehensive inclusion of mutations with clinically-observed gene expression changes (e.g., HER2Δ or MET overexpression) and/or broader epigenetic dysregulation (e.g., BAP1), will be critical in facilitating clinical-translational progress of the rapidly emerging genomic knowledge of BTCs. Serial sampling studies utilizing liquid biopsy will be powerful in constructing preclinical models of acquired drug resistance. Organoid models can facilitate the culture of primary samples with preservation of in vivo tumor characteristics, correlating well with clinical characteristics. Importantly organoid models can facilitate the efficient and cost-effective preclinical characterization of targeted therapies and combinations thereof.94 In addition to testing logically-deduced drug selection, unbiased functional studies, such as Genome-Scale CRISPR-Cas9 Knock-Out screening,95 will be powerful preclinical tools to advance precision medicine in more complex models where known genomic alterations may be currently “undruggable,” and where the best targeting strategies may not be obvious, e.g., p53-mutated or KRAS-mutated context(s). Where adequate resources are available, and where preclinical data justify, patient samples can also be assessed in patient-derived xenograft and/or transgenic animal models used.

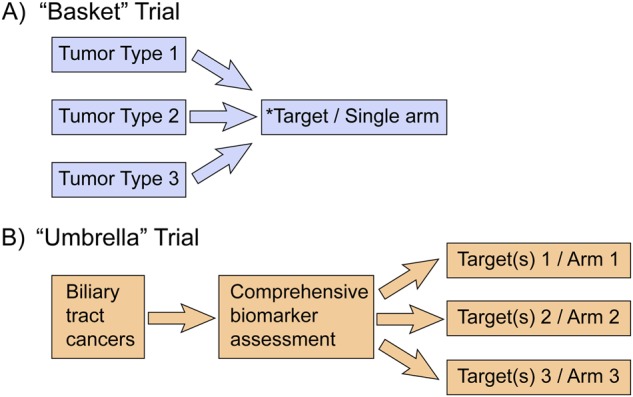

Clinical trial design for BTCs in the era of precision medicine

In terms of clinical investigation, there is a tension in the BTC field between pursuing empirical approaches versus knowledge-based approaches, which represents a huge problem particularly in the adjuvant setting as compared to the advanced setting. The BILCAP study is the first study in the adjuvant setting to enroll a sufficient number of BTC patients to demonstrate that chemotherapy can significantly improve OS. Capecitabine improved OS by 15 months over surgery alone (53 vs. 36 months).96 Single-drug, single-trial, company-driven trials currently predominate the clinical trial landscape. This clinical trial design is sub-optimal for BTC patients, as well as the progress of precision oncology. A single, continuous “umbrella” trial, that can be used for registration studies, conducted using a single comprehensive assay that can identify all known biomarkers and facilitate assignment of patients to multiple corresponding treatment arms (arms which can be dynamically added or terminated as necessary) represents a much more appropriate patient-centric approach, as compared to antiquated sponsor-centric approaches (Fig. 2). A French trial called ONCOBIL is genotyping patients with malignant biliary stricture as compared to patients treated for benign biliary diseases (N = 50 each, NCT02893085), but does not feature assignment to corresponding treatment arms. For very low prevalence alterations such as NTRK or ROS1 fusions97,98 a more relevant design may be the “basket” or tumor-agnostic trial where approval is based on the target and not by the disease, as exemplified by PD-1 inhibitors for MSI/MMR, and likely forthcoming approvals for LOXO-101 (larotrectinib99) and RXDX-101 (entrectinib100) based on NTRK and NTRK/ROS1 fusions. However, not all mutations will be amendable to tumor-agnostic monotherapy development approaches, as many mutations will undoubtedly have distinct underlying biology and thus distinct outcomes may be observed in different tumors, as exemplified by MEK and BRAF inhibitor development.

Fig. 2.

Clinical trial design for biliary tract cancers in the era of precision medicine. a “Basket” trial design vs. b “umbrella” trial design. *Preferable for BTC targets occurring at low prevalence (<5%)

Conclusions

While treatment of MSI-H/dMMR tumors with pembrolizumab is currently the only targeted, biomarker-based therapy FDA-approved for BTCs, there are many potentially actionable aberrations in BTCs, and comprehensive genomic profiling is highly recommended in the management of BTCs. Additional biomarker-based treatments such as NTRK/ROS1-targeted therapies, albeit very low prevalence in BTCs, and FGFR-targeted therapies, are likely candidates for near-term regulatory approvals. There are several targeted therapies FDA-approved for other indications (e.g., HER2-targeted agents) with potential relevance for precision oncology application in BTCs that could possibly be considered for off-label use on a case-by-case basis. Importantly, there are also several biomarker-driven and unselected clinical trials for many of these FDA-approved agents to expand into BTCs, as well as for novel targeted therapies, that should be watched and considered for enrollment. Biomarker-driven umbrella or basket trials will be of high interest to BTC research efforts, as well as facilitating the development of novel targeted agents and combinations thereof. Many of the mutations/aberrations observed in BTCs are often indolent drivers alone (e.g., IDH or FGFR2), and even where such drivers may be significantly beneficial to target as monotherapy, combination therapy targeting two or more drivers is likely to yield deeper and more durable responses. Well-designed preclinical models, that recapitulate in vivo properties and thus can accurately interrogate precise genomic contexts to derive and test such combination therapies, will be paramount in moving beyond empirical therapy into a new era of precision therapy for BTCs.

Author contributions

All authors made contributions in preparing this review article, and read/approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

J.M.B. owns purchased stock of Array BioPharma, Arqule Inc., Clovis Oncology, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, and Seattle Genetics. M.J.B. owns purchased stock of Intercept Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Razumilava N, Gores GJ. Building a staircase to precision medicine for biliary tract cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:967. doi: 10.1038/ng.3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valle J, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendriks YM, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma): a guide for clinicians. Cancer J. Clin. 2006;56:213–225. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes-Ciriano I, Lee S, Park WY, Kim TM, Park PJ. A molecular portrait of microsatellite instability across multiple cancers. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15180. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herman JG, et al. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6870–6875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ligtenberg MJ, et al. Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3′ exons of TACSTD1. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:112–117. doi: 10.1038/ng.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalmers ZR, et al. Analysis of tumor mutation burden (TMB) in >51,000 clinical cancer patients to identify novel non-coding PMS2 promoter mutations associated with increased TMB. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:9572–9572. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volinia S, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemery S, Keegan P, Pazdur R. First FDA approval agnostic of cancer site—when a biomarker defines the indication. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1409–1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1709968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva VW, et al. Biliary carcinomas: pathology and the role of DNA mismatch repair deficiency. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2016;5:62. doi: 10.21037/cco.2016.10.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buecher B, et al. Role of microsatellite instability in the management of colorectal cancers. Dig. Liver Dis. 2013;45:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umar A, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261–268. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman AM, et al. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017;16:2598–2608. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura H, et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/ng.3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabbatino F, et al. PD-L1 and HLA Class I antigen expression and clinical course of the disease in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:470–478. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fontugne J, et al. PD-L1 expression in perihilar and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:24644–24651. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bang, Y. J. et al. 525 Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in patients (pts) with advanced biliary tract cancer: interim results of KEYNOTE-028. Eur. J. Cancer51, S112.

- 19.Barrett MT, et al. Genomic amplification of 9p24.1 targeting JAK2, PD-L1, and PD-L2 is enriched in high-risk triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26483–26493. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green MR, et al. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:3268–3277. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 is upregulated in intrahepatic lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69749–69759. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arai Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 tyrosine kinase fusions define a unique molecular subtype of cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;59:1427–1434. doi: 10.1002/hep.26890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham RP, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 translocations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2014;45:1630–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javle M, et al. Biliary cancer: utility of next-generation sequencing for clinical management. Cancer. 2016;122:3838–3847. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farshidfar F, et al. Integrative genomic analysis of cholangiocarcinoma identifies distinct IDH-mutant molecular profiles. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2878–2880. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guagnano V, et al. Discovery of 3-(2,6-dichloro-3,5-dimethoxy-phenyl)-1-{6-[4-(4-ethyl-piperazin-1-yl)-phenylamin o]-pyrimidin-4-yl}-1-methyl-urea (NVP-BGJ398), a potent and selective inhibitor of the fibroblast growth factor receptor family of receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:7066–7083. doi: 10.1021/jm2006222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javle, M. et al. Phase II Study of BGJ398 in patients with FGFR-altered advanced cholangiocarcinoma. (2017). J Clin Oncol. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.5009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gilbert, J. A. BGJ398 for FGFR-altered advanced cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30902-6 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Perwad F, Zhang MY, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Fibroblast growth factor 23 impairs phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism in vivo and suppresses 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1alpha-hydroxylase expression in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2007;293:F1577–F1583. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00463.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gattineni J, et al. FGF23 decreases renal NaPi-2a and NaPi-2c expression and induces hypophosphatemia in vivo predominantly via FGF receptor 1. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2009;297:F282–F291. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90742.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saleh M, et al. Abstract CT111: preliminary results from a phase 1/2 study of INCB054828, a highly selective fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor, in patients with advanced malignancies. Cancer Res. 2017;77:CT111–CT111. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-CT111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall TG, et al. Preclinical activity of ARQ 087, a novel inhibitor targeting FGFR dysregulation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papadopoulos KP, et al. A Phase 1 study of ARQ 087, an oral pan-FGFR inhibitor in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer. 2017;117:1592–1599. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzaferro V, et al. ARQ 087, an oral pan-fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor, in patients (pts) with advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) with FGFR2 genetic aberrations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:4017–4017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goyal L, et al. Polyclonal secondary FGFR2 mutations drive acquired resistance to FGFR inhibition in patients with FGFR2 fusion-positive cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:252–263. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim ST, et al. Prospective blinded study of somatic mutation detection in cell-free DNA utilizing a targeted 54-gene next generation sequencing panel in metastatic solid tumor patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6:40360–40369. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song KH, Li T, Owsley E, Strom S, Chiang JY. Bile acids activate fibroblast growth factor 19 signaling in human hepatocytes to inhibit cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene expression. Hepatology. 2009;49:297–305. doi: 10.1002/hep.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holt JA, et al. Definition of a novel growth factor-dependent signal cascade for the suppression of bile acid biosynthesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1581–1591. doi: 10.1101/gad.1083503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnold A, et al. Genome wide DNA copy number analysis in cholangiocarcinoma using high resolution molecular inversion probe single nucleotide polymorphism assay. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2015;99:344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaibori M, et al. Increased FGF19 copy number is frequently detected in hepatocellular carcinoma with a complete response after sorafenib treatment. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49091–49098. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bengala C, et al. Sorafenib in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a phase II trial. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;102:68–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo X, et al. Effectiveness and safety of sorafenib in the treatment of unresectable and advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a pilot study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:17246–17257. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakunta HR, Sunderkrishnan R, Kaplan MA, Mostofi R. Cholangiocarcinoma: treatment with sorafenib extended life expectancy to greater than four years. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2013;4:E30–E32. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2013.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsukada Y, et al. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu W, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borger DR, et al. Frequent mutation of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1 and IDH2 in cholangiocarcinoma identified through broad-based tumor genotyping. Oncologist. 2012;17:72–79. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiao Y, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1470–1473. doi: 10.1038/ng.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang P, et al. Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 occur frequently in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas and share hypermethylation targets with glioblastomas. Oncogene. 2013;32:3091–3100. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu AX, et al. Genomic profiling of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: refining prognosis and identifying therapeutic targets. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014;21:3827–3834. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3828-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshikawa D, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of EGFR, VEGF, and HER2 expression in cholangiocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;98:418–425. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang X, et al. Characterization of EGFR family gene aberrations in cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2014;32:700–708. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Javle M, et al. HER2/neu-directed therapy for biliary tract cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015;8:58. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J, et al. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with or without erlotinib in advanced biliary-tract cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:181–188. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borad MJ, et al. Integrated genomic characterization reveals novel, therapeutically relevant drug targets in FGFR and EGFR pathways in sporadic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li M, et al. Whole-exome and targeted gene sequencing of gallbladder carcinoma identifies recurrent mutations in the ErbB pathway. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:872–876. doi: 10.1038/ng.3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deshpande V, et al. Mutational profiling reveals PIK3CA mutations in gallbladder carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Churi CR, et al. Mutation profiling in cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic and therapeutic implications. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bekaii-Saab T, et al. Multi-institutional phase II study of selumetinib in patients with metastatic biliary cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2357–2363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brea EJ, et al. Kinase regulation of human MHC class I molecule expression on cancer cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016;4:936–947. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sullivan RJ, et al. Atezolizumab (A) + cobimetinib (C) + vemurafenib (V) in BRAFV600-mutant metastatic melanoma (mel): updated safety and clinical activity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:3063–3063. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ewald F, et al. Dual Inhibition of PI3K-AKT-mTOR- and RAF-MEK-ERK-signaling is synergistic in cholangiocarcinoma and reverses acquired resistance to MEK-inhibitors. Invest. New Drugs. 2014;32:1144–1154. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyamoto M, et al. Prognostic significance of overexpression of c-Met oncoprotein in cholangiocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2011;105:131–138. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yakes FM, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2298–2308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goyal L, et al. A phase 2 and biomarker study of cabozantinib in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer. 2017;123:1979–1988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riener MO, Bawohl M, Clavien PA, Jochum W. Rare PIK3CA hotspot mutations in carcinomas of the biliary tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:363–367. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shigematsu H, Takahashi T, Minna JD, Gazdar AF, Wistuba II. PIK3CA mutations in gallbladder cancers. Cancer Res. 2006;66:50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yeung Y, et al. K-Ras mutation and amplification status is predictive of resistance and high basal pAKT is predictive of sensitivity to everolimus in biliary tract cancer cell lines. Mol. Oncol. 2017;11:1130–1142. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin L, et al. Anti-tumor effects of NVP-BKM120 alone or in combination with MEK162 in biliary tract cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;411:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ahn DH, et al. Results of an abbreviated phase-II study with the Akt inhibitor MK-2206 in patients with advanced biliary cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12122. doi: 10.1038/srep12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y, et al. A novel PI3K/AKT signaling axis mediates Nectin-4-induced gallbladder cancer cell proliferation, metastasis and tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2016;375:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Challita-Eid PM, et al. Enfortumab vedotin antibody-drug conjugate targeting nectin-4 is a highly potent therapeutic agent in multiple preclinical cancer models. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3003–3013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ross JS, et al. New routes to targeted therapy of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas revealed by next-generation sequencing. Oncologist. 2014;19:235–242. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tadokoro H, Shigihara T, Ikeda T, Takase M, Suyama M. Two distinct pathways of p16 gene inactivation in gallbladder cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6396–6403. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kagohara LT, et al. Global and gene-specific DNA methylation pattern discriminates cholecystitis from gallbladder cancer patients in Chile. Future Oncol. 2015;11:233–249. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahn DH, et al. Next-generation sequencing survey of biliary tract cancer reveals the association between tumor somatic variants and chemotherapy resistance. Cancer. 2016;122:3657–3666. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simbolo M, et al. Multigene mutational profiling of cholangiocarcinomas identifies actionable molecular subgroups. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2839–2852. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Golan T, et al. Overall survival and clinical characteristics of BRCA-associated cholangiocarcinoma: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Oncologist. 2017;22:804–810. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xie Y, et al. Response of BRCA1-mutated gallbladder cancer to olaparib: a case report. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10254–10259. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i46.10254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shen J, et al. ARID1A deficiency impairs the DNA damage checkpoint and sensitizes cells to PARP inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:752–767. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Robertson AG, et al. Integrative analysis identifies four molecular and clinical subsets in uveal melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:204–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dalmasso C, et al. Patterns of chromosomal copy-number alterations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:126. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang B, House MG, Guo M, Herman JG, Clark DP. Promoter methylation profiles of tumor suppressor genes in intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2004;18:412. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jusakul A, et al. Whole-genome and epigenomic landscapes of etiologically distinct subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1116–1135. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Delmore JE, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146:904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhu H, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition promotes antitumor immunity by suppressing PD-L1 expression. Cell Rep. 2016;16:2829–2837. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Okaro AC, Deery AR, Hutchins RR, Davidson BR. The expression of antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L), and Mcl-1 in benign, dysplastic, and malignant biliary epithelium. J. Clin. Pathol. 2001;54:927–932. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.12.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Isomoto H, et al. Sustained IL-6/STAT-3 signaling in cholangiocarcinoma cells due to SOCS-3 epigenetic silencing. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:384–396. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoon JH, et al. Bile acids inhibit Mcl-1 protein turnover via an epidermal growth factor receptor/Raf-1-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6500–6505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang W, et al. FXR agonists enhance the sensitivity of biliary tract cancer cells to cisplatin via SHP dependent inhibition of Bcl-xL expression. Oncotarget. 2016;7:34617–34629. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tannapfel A, et al. Frequency ofp16(INK4A) alterations and K-ras mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver. Gut. 2000;47:721–727. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Imamura F, et al. Monitoring of treatment responses and clonal evolution of tumor cells by circulating tumor DNA of heterogeneous mutant EGFR genes in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2016;94:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zill OA, et al. Cell-Free DNA next-generation sequencing in pancreatobiliary carcinomas. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1040–1048. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sato T, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shalem O, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Primrose JN, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for biliary tract cancer: the BILCAP randomized study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:4006–4006. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gu TL, et al. Survey of tyrosine kinase signaling reveals ROS kinase fusions in human cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee KH, et al. Clinical and pathological significance of ROS1 expression in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:721. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1737-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hyman DM, et al. The efficacy of larotrectinib (LOXO-101), a selective tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) inhibitor, in adult and pediatric TRK fusion cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:LBA2501–LBA2501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.18_suppl.LBA2501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Drilon A, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of the multitargeted Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor entrectinib: combined results from two phase ITrials (ALKA-372-001 and STARTRK-1) Cancer Discov. 2017;7:400–409. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]