Abstract

Cytoplasmic dynein is a minus-end-directed microtubule-based motor that acts at diverse subcellular sites. During mitosis, dynein localizes simultaneously to the mitotic spindle, spindle poles, kinetochores and the cell cortex. However, it is unclear what controls the relative targeting of dynein to these locations. As dynein is heavily post-translationally modified, we sought to test a role for these modifications in regulating dynein localization. We find that dynein rapidly and strongly accumulates at mitotic spindle poles following treatment with NSC697923, a small molecule that inhibits the ubiquitin E2 enzyme, Ubc13, or treatment with PYR-41, a ubiquitin E1 inhibitor. Subsets of dynein regulators such as Lis1, ZW10 and Spindly accumulate at the spindle poles, whereas others do not, suggesting that NSC697923 differentially affects specific dynein populations. We additionally find that dynein relocalization induced by NSC697923 or PYR-41 can be suppressed by simultaneous treatment with the non-selective deubiquitinase inhibitor, PR-619. However, we did not observe altered dynein localization following treatment with the selective E1 inhibitor, TAK-243. Although it is possible that off-target effects of NSC697923 and PYR-41 are responsible for the observed changes in dynein localization, the rapid relocalization upon drug treatment highlights the highly dynamic nature of dynein regulation during mitosis.

Keywords: dynein, ubiquitin, NSC697923, PYR-41, mitosis, microtubules

1. Introduction

Dynein is a AAA+ ATPase that uses the energy from ATP hydrolysis to walk along a microtubule [1]. Dynein localizes to diverse sites within the cell, including the mitotic spindle, the centrosomes, the nuclear envelope, the kinetochores and the cell cortex, where it performs numerous roles in interphase and mitosis [2]. This subcellular targeting is accomplished in part by the association of the dynein complex with various regulatory and adaptor proteins, including the dynactin complex, NuMA, Spindly, Bicaudal D2, Nde1 (also known as NudE) and others [3].

Dynein is also heavily post-translationally modified [4], suggesting the presence of additional mechanisms for regulating its localization and function. For example, multiple sites within dynein are modified by ubiquitin [4–11]. The most well-characterized function of ubiquitination is to target a substrate for degradation by the 26S proteasome [12], but ubiquitination also plays non-degradative roles in regulating diverse processes such as endocytosis and DNA repair [13,14]. Additionally, protein–protein interactions and localization can be regulated by ubiquitination [15]. Prior work has identified several ubiquitination sites within the dynein complex or dynein regulatory proteins that do not increase in abundance upon proteasome inhibition [6], and therefore may alter dynein function through non-degradative mechanisms. Indeed, evidence suggests that the dynein–NuMA interaction is enhanced by non-degradative ubiquitination [16], and a role for non-degradative ubiquitination has also been implicated in indirectly targeting dynein to the cell cortex [17].

Ubiquitination is mediated by the sequential actions of an E1 activating enzyme, an E2 conjugating enzyme and an E3 ligase. Polyubiquitin chains can be built from any of seven internal lysines or the N-terminal methionine of ubiquitin [12]. The type of linkage used in building the polyubiquitin chain helps to determine the downstream effect on the ubiquitinated substrate [12]. For example, proteasome targeting is typically directed by the synthesis of a lysine 48-linked polyubiquitin chain [12], whereas a K63-linked chain is the most abundant non-degradative ubiquitination event [18]. The E2 enzymes typically specify the type of linkage generated, with Ubc13 acting as the primary ubiquitin E2 enzyme involved in K63-linked non-degradative chain formation [13]. However, the cellular processes regulated by non-degradative ubiquitination remain incompletely understood.

Here, we use a small molecule inhibitor of Ubc13, as well as inhibitors targeting other components of the ubiquitin conjugation machinery to reveal the highly dynamic nature of dynein localization in mitotic cells.

2. Results

2.1. Dynein rapidly accumulates at the spindle poles following Ubc13 inhibition by NSC697923 treatment

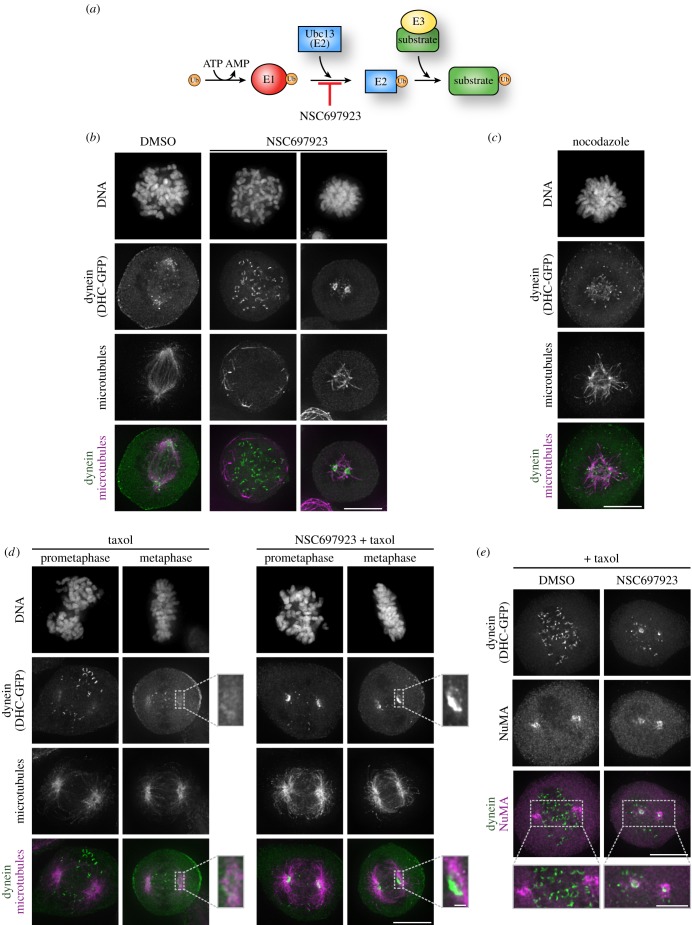

We hypothesized that post-translational modifications may play a critical role in controlling the subcellular localization of the cytoplasmic dynein complex. We therefore sought to identify perturbations that alter dynein localization. To begin, we treated HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-tagged dynein heavy chain (DHC-GFP) with inhibitors of mitotic kinases and phosphatases to perturb cellular phosphorylation. We did not observe any obvious changes in the mitotic localization of dynein following transient inhibition of Aurora kinases (ZM447439/VX680), cyclin-dependent kinase (flavopiridol), Mps1 (AZ3146), Plk1 (BI2536), PP1 or PP2A (okadaic acid) (data not shown). We next tested for a contribution from ubiquitination to dynein localization by treating with the Ubc13 inhibitor, NSC697923 (figure 1a) [19]. After only 15 min of treatment, NSC697923 caused a nearly complete disassembly of the mitotic spindle in 23 of 100 mitotic cells analysed (figure 1b). Strikingly, in the majority of cells with spindle microtubules remaining, we observed a dramatic accumulation of dynein at two foci that correspond to the spindle poles (figure 1b). Treatment with a low dose of nocodazole resulted in a similar disruption of the mitotic spindle, but did not induce dynein accumulation at the spindle poles, suggesting that the NSC697923-induced effects on dynein localization are independent of its effects on the mitotic spindle (figure 1c). To further test this, we stabilized the mitotic spindle by treating cells with the microtubule-stabilizing drug taxol. Taxol treatment alone did not alter the localization of dynein (figure 1d). We next simultaneously treated cells with NSC697923 and taxol. Under these conditions, the mitotic spindle was largely preserved and we again observed strong dynein relocalization to the spindle poles in 79 ± 6% of cells in either prometaphase or metaphase, compared with only 1 ± 2% of cells treated with taxol alone (figure 1d; see also figure 6). Line scan analyses confirmed an increase in dynein intensity at the spindle poles following NSC697923 treatment (electronic supplementary material, figure S1A). This suggests that the change in dynein localization is not a secondary consequence of disrupting the structure of the mitotic spindle. Co-staining for NuMA, one of the outermost proteins at the spindle pole [20], revealed that NuMA localization is unaffected by NSC697923 treatment (figure 1e; electronic supplementary material, figure S1B) and that the spindle pole-localized dynein was slightly internal to the localization of NuMA (figure 1e). Together, our data demonstrate a rapid accumulation of dynein at the spindle poles following the addition of the small molecule inhibitor, NSC697923.

Figure 1.

NSC697923 induces accumulation of dynein at the mitotic spindle poles. (a) Cartoon of the ubiquitin conjugation pathway. NSC697923 is a small molecule inhibitor of the ubiquitin E2 enzyme, Ubc13. (b–d) Immunofluorescence images of DNA (Hoechst), stably expressed dynein heavy chain-GFP (DHC-GFP), and microtubules (DM1A) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bars, 10 µm; 1 µm in the magnified panel. (e) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed dynein heavy chain-GFP (DHC-GFP) and NuMA after treatment for 15 min with NSC697923 and taxol. Scale bar, 10 µm; 5 µm in the magnified panel.

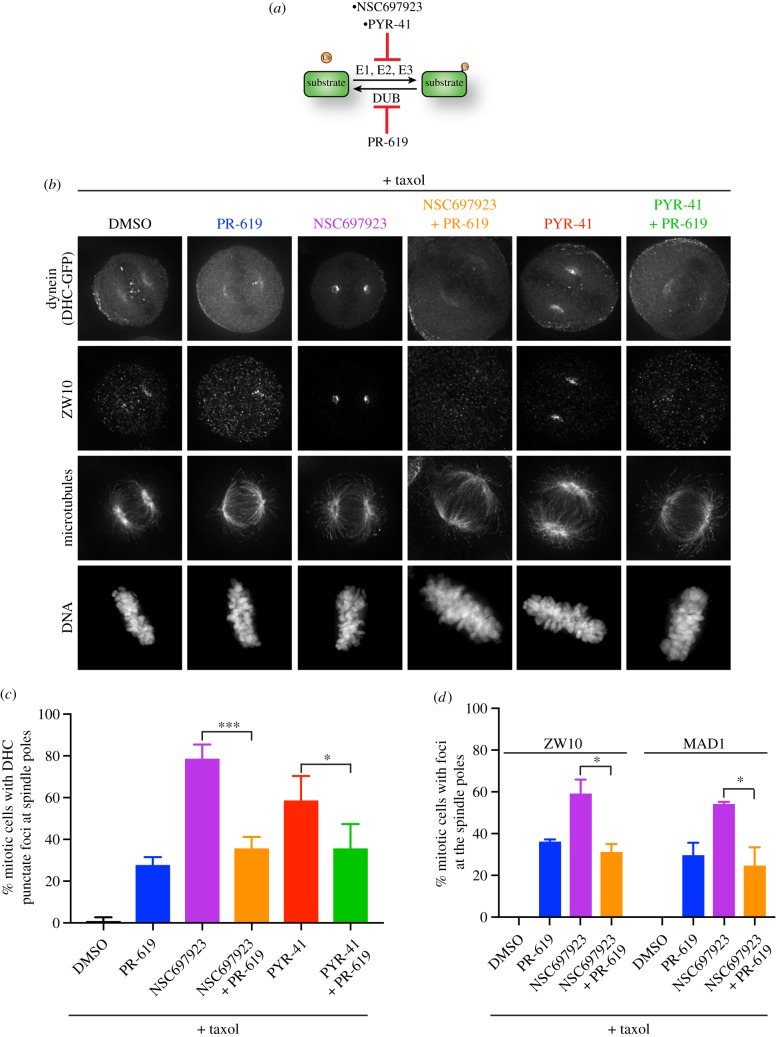

Figure 6.

PR-619 suppresses the relocalization of dynein induced by NSC697923 and PYR-41. (a) Cartoon illustrating the competing actions of the ubiquitinating enzymes with the deubiquitinases. PR-619 is a non-selective deubiquitinase inhibitor. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed dynein heavy chain-GFP (DHC-GFP), ZW10, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (c) Quantification of the percentage of mitotic cells with punctate foci of dynein heavy chain on the spindle poles for the indicated conditions. The data represent the replicate mean ± s.d. Each replicate included 100 cells. Three to four replicates were analysed for all conditions. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. ***p ≤ 0.001; *p ≤ 0.05. (d) Quantification of the percentage of mitotic cells with either ZW10 or MAD1 on the spindle poles for the indicated conditions. ZW10 and MAD1 were co-stained in the cells analysed here (and distinct from the cells used to quantify DHC relocalization in panel c above). We note that all cells with spindle pole-localized MAD1 also had ZW10 on the spindle poles. A few cells with weak ZW10 signal did not display detectable MAD1 localization. The data represent the replicate mean ± s.d. Each replicate included 100 cells. Two replicates were analysed for each condition. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. *p ≤ 0.05.

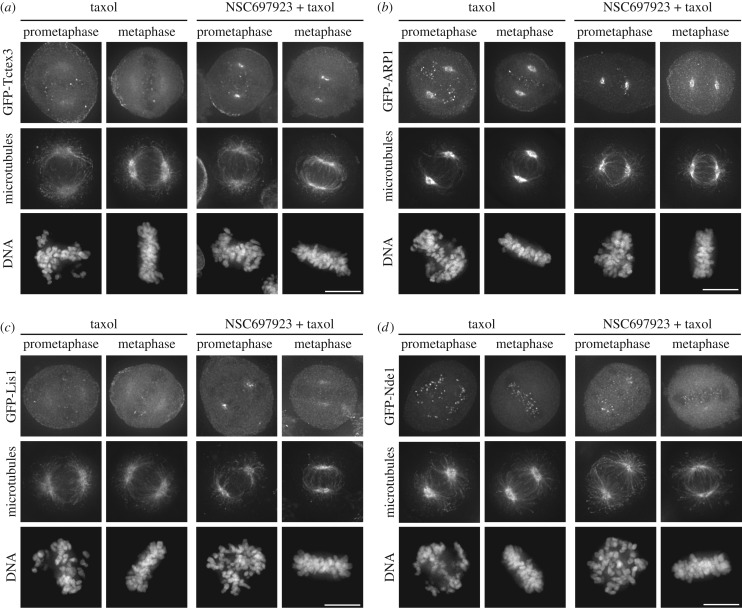

2.2. A subset of dynein-associated factors accumulate at spindle poles after NSC697923 treatment

Dynein heavy chain associates with numerous proteins, including other subunits of the dynein complex, as well as various adaptor proteins [3]. We therefore sought to determine which other proteins accumulate with dynein heavy chain at the spindle poles after NSC697923 treatment. As expected, another subunit of the dynein complex, the dynein light chain Tctex-type 3, also accumulated at the mitotic spindle poles following NSC697923 addition (figure 2a). By contrast, ARP1, a subunit of the dynactin complex and a key regulator of dynein, strongly localizes to mitotic spindle poles in untreated cells, with no obvious alteration in localization following NSC697923 treatment (figure 2b). Next, we examined Lis1 and Nde1, proteins that coordinately regulate diverse functions of dynein [3,21]. Lis1 strongly accumulated at the spindle poles following NSC697923 treatment during prometaphase (figure 2c), whereas the localization of Nde1 was comparatively unaffected in both prometaphase and metaphase (figure 2d). Because only a subset of dynein-interacting proteins relocalize to the spindle poles after NSC697923 treatment, these data suggest that NSC697923 differentially affects specific dynein complexes.

Figure 2.

NSC697923 induces accumulation of a subset of dynein regulators at the mitotic spindle poles. (a) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed GFP-Tctex-type 3, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed GFP-ARP1, microtubules (DM1A), and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (c) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed GFP-Lis1, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (d) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed GFP-Nde1, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm.

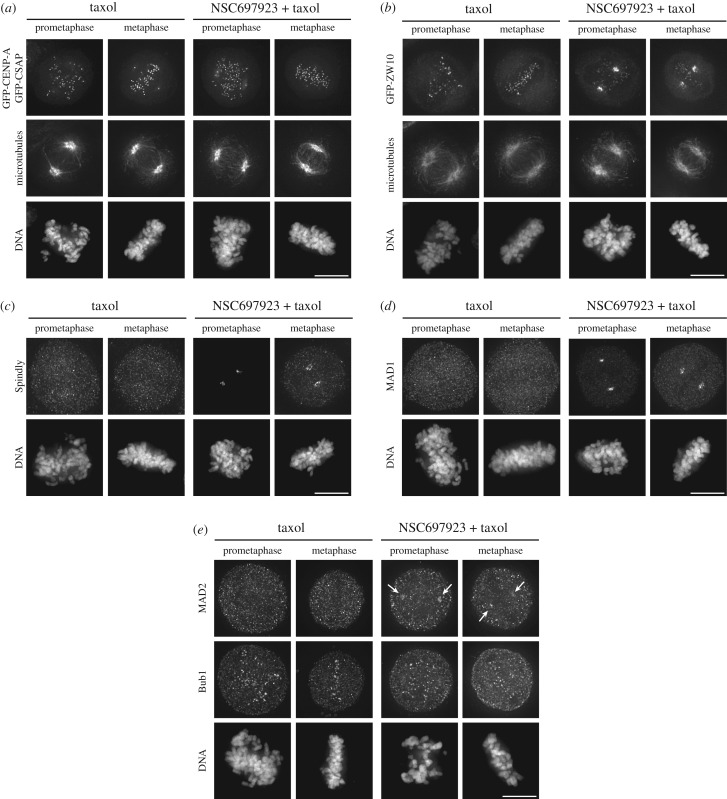

We next sought to test the localization of diverse mitotic proteins following NSC697923 treatment. In addition to the spindle pole-localized protein NuMA (figure 1e), we found that the centriole and spindle-localized protein CSAP [22] appeared unaffected by treatment with NSC697923 (figure 3a). The centromere-localized protein, CENP-A, was similarly unaffected by NSC697923 treatment (figure 3a). Thus, NSC697923 does not globally disrupt mitotic protein function.

Figure 3.

NSC697923 induces accumulation of a subset of dynein interactors at the mitotic spindle poles. (a) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed GFP-CENP-A and GFP-CSAP, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed GFP-ZW10, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (c) Representative immunofluorescence images of Spindly and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (d) Representative immunofluorescence images of MAD1 and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (e) Representative immunofluorescence images of MAD2, Bub1 and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Arrows indicate weak, but detectable localization of MAD2 at the spindle poles. Scale bar, 10 µm.

The Rod/Zwilch/ZW10 (RZZ) complex and Spindly are involved in targeting dynein to mitotic kinetochores [3] and have been proposed to be cargo of the dynein complex [23]. In agreement with this, we found that ZW10 and Spindly accumulated at the spindle poles after treatment with NSC697923 (figure 3b,c). The RZZ complex also plays a key role in targeting the spindle assembly checkpoint proteins, MAD1 and MAD2, to mitotic kinetochores [24–26]. We found that MAD1 clearly accumulates at the spindle poles following NSC697923 treatment (figure 3d). The behaviour of MAD2 was more variable, but we typically saw some localization of MAD2 at the spindle poles in NSC697923-treated cells that we did not observe in control cells (figure 3e). By contrast, the localization of Bub1, a key protein involved in targeting the RZZ complex to mitotic kinetochores [24,27], appeared unaffected by NSC697923 treatment (figure 3e). Together, these data define a subset of dynein-interacting proteins that show altered localization following treatment with NSC697923.

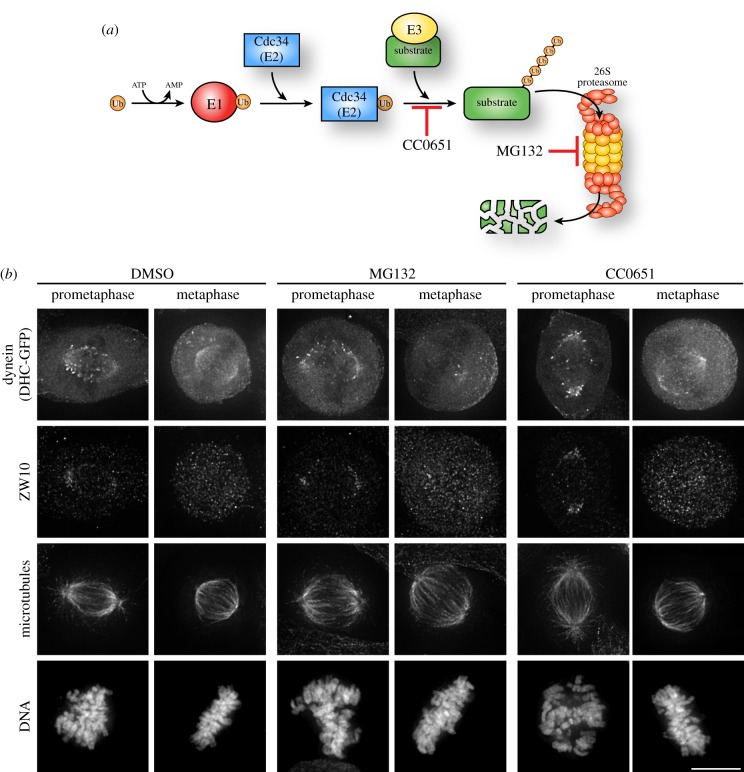

2.3. Proteasome inhibition does not alter dynein localization in mitosis

Although K63-linked polyubiquitination is not a canonical signal for degradation, K63 chains can still alter substrate stability [12]. To test whether the relocalization of dynein following NSC697923 treatment was due to altered protein stability, we assessed dynein localization following inhibition of the proteasome with MG132 (figure 4a). In contrast to the relocalization induced by NSC697923 treatment, proteasome inhibition did not induce an accumulation of dynein at spindle poles (figure 4b). We also visualized endogenous ZW10 in these cells by immunofluorescence and did not observe signal that noticeably differed from DMSO-treated cells (figure 4b). Proteasomal targeting is frequently accomplished by K48-linked polyubiquitin chains, and Cdc34 is a key E2 enzyme involved in K48-linked polyubiquitin chain formation [28]. We therefore also used CC0651 [29], an inhibitor of Cdc34, and again did not observe a change in dynein or ZW10 localization (figure 4b). Collectively, these results suggest that the mitotic localization of dynein is not regulated by a degradative ubiquitination event.

Figure 4.

Dynein localization is not controlled by degradative ubiquitination. (a) Cartoon of the ubiquitin conjugation pathway illustrating the ubiquitin E2 enzyme, Cdc34, and the targeting of substrates for degradation by the 26S proteasome. CC0651 inhibits Cdc34 and MG132 inhibits the proteasome. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed dynein heavy chain-GFP (DHC-GFP), ZW10, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm.

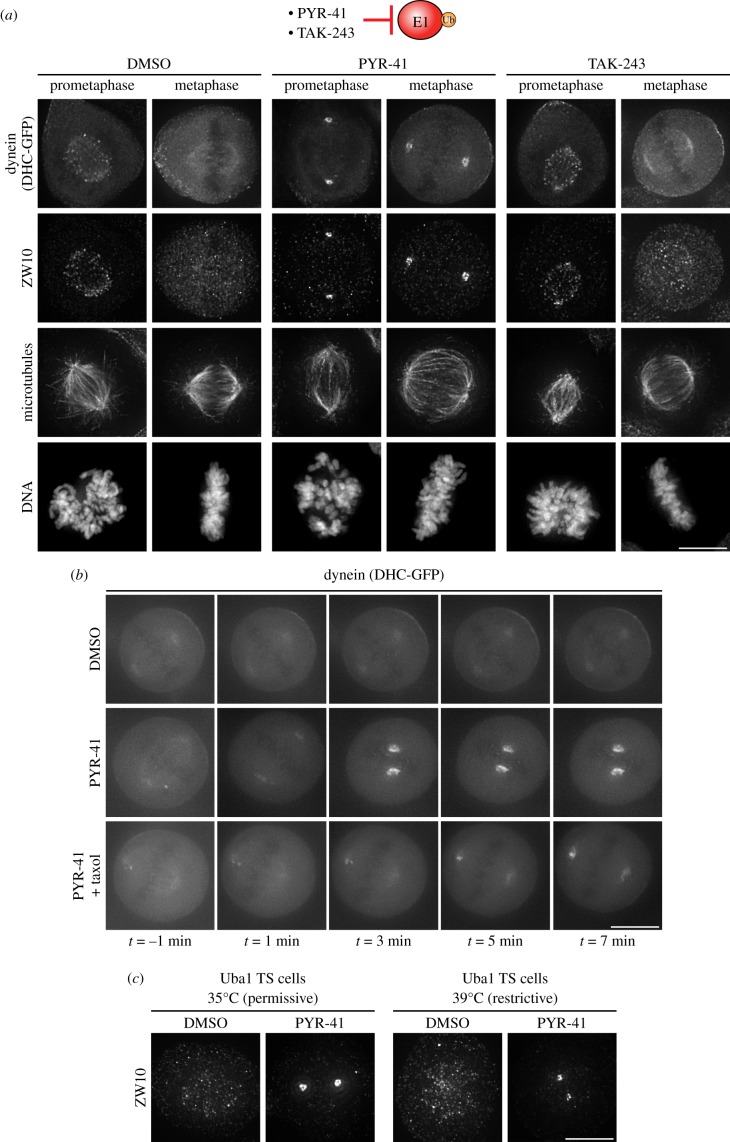

2.4. Ubiquitin E1 inhibitors have differential effects on dynein localization in mitosis

Ubiquitination requires the sequential activities of three distinct enzymes. The E2 enzymes, such as Ubc13, rely on an upstream ubiquitin activation step performed by a ubiquitin E1 enzyme. We therefore sought to further test whether the relocalization of dynein induced by NSC697923 treatment is due to inhibition of ubiquitination by treating cells with PYR-41 [30] or TAK-243 [31], small molecule inhibitors that target the E1 enzyme. As we observed for NSC697923 treatment, PYR-41 rapidly induced the accumulation of dynein and ZW10 at spindle poles (figure 5a). Indeed, by live-cell imaging, increased dynein levels were observed at poles within 5 min of addition of PYR-41 in both the absence and presence of taxol to stabilize the mitotic spindle (figure 5b). However, the recently developed E1 inhibitor, TAK-243, did not affect dynein localization (figure 5a). TAK-243 is a potent inhibitor of both Uba1 and the other human ubiquitin E1 enzyme, Uba6 [31]. Thus, the lack of dynein relocalization following TAK-243 treatment suggests that the NSC697923 and PYR-41-induced spindle pole accumulation of dynein could be due to off-target effects. To test this possibility, we used the TS20 cell line that contains temperature-sensitive mutations in Uba1 [32,33], the primary ubiquitin E1 enzyme. At the restrictive temperature, Uba1 levels should be significantly reduced, yet we did not observe an accumulation of ZW10 at the spindle poles (figure 5c). Additionally, in the absence of Uba1, the cells should be insensitive to any on-target effects of PYR-41. However, we found that PYR-41 still induced ZW10 accumulation at the spindle poles at the restrictive temperature (figure 5c). We were also unable to validate the specificity of PYR-41 using a CRISPR/Cas9-based system [34] to eliminate Uba1 from HeLa cells (data not shown). Therefore, it is possible that the relocalization of dynein induced by PYR-41 and NSC697923 is not due to directly interfering with ubiquitination, but instead is caused by off-target effects.

Figure 5.

Dynein accumulation at the spindle poles is induced by PYR-41. (a) Top: Cartoon illustrating inhibition of the ubiquitin E1 enzyme by PYR-41 and TAK-243. Bottom: Representative immunofluorescence images of stably expressed dynein heavy chain-GFP (DHC-GFP), ZW10, microtubules (DM1A) and DNA (Hoechst) after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) Representative images of live cells stably expressing dynein heavy chain-GFP (DHC-GFP) before and after addition of the indicated drugs at t = 0. Scale bar, 10 µm. (c) Representative immunofluorescence images of ZW10 in TS20 cells after treating the cells for 15 min with the indicated compounds. Scale bar, 10 µm.

2.5. NSC697923- and PYR-41-induced dynein relocalization is suppressed by simultaneous treatment with the deubiquitinase inhibitor PR-619

If the PYR-41- and NSC697923-mediated effects on dynein localization are due to inhibition of ubiquitination, we reasoned that inhibiting the deubiquitinases might also perturb the localization of dynein due to the dynamic balance of ubiquitin conjugation. To test this premise, we assessed the consequences of treating cells with the non-selective deubiquitinase inhibitor, PR-619 (figure 6a). Addition of PR-619 induced dynein accumulation at the spindle poles in a smaller percentage of cells relative to NSC697923 or PYR-41 treatment (figure 6b,c). However, when PR-619 was simultaneously added to cells with either NSC697923 or PYR-41, the percentage of cells exhibiting accumulated dynein was reduced relative to NSC697923 or PYR-41 treatment alone (figure 6b,c). Thus, PR-619 treatment appeared to suppress the effects of NSC697923 and PYR-41 on dynein localization. Similar trends were also observed for the relocalization of ZW10 and MAD1 (figure 6d). If the effects of these compounds are on-target, these results suggest that ubiquitination dynamics may be critical for controlling dynein localization during mitosis. Inhibiting ubiquitination by NSC697923 or PYR-41 treatment may allow the counteracting deubiquitinases to dominate, thereby resulting in rapid removal of ubiquitin from the substrate and ultimately causing dynein to accumulate at the spindle poles.

Together, our observations that the mitotic localization of dynein can be rapidly altered highlight the highly dynamic nature of dynein regulation within the cell.

3. Discussion

As the primary minus-end-directed microtubule motor, dynein is required for numerous cellular processes. Thus, the localization and function of dynein must be precisely regulated. For example, dynamic regulation of dynein localization during mitosis is required for proper positioning of the mitotic spindle within the cell during both metaphase and anaphase [35,36]. Our work highlights that the localization of dynein can be rapidly altered, as we observe a dramatic change in the subcellular distribution of dynein within minutes of drug addition. The ability to quickly retarget dynein to specific sites may allow the cell to dynamically respond to changing needs in force generation or cargo transport.

NSC697923 and PYR-41 could alter dynein localization by several possible mechanisms. First, as dynein is a minus-end-directed motor and the microtubule minus ends are located at the spindle poles, these inhibitors could stimulate dynein motility. In support of this model, dynein relocalization is not observed when the microtubules have been depolymerized (figure 1c). A second, non-mutually exclusive mechanism entails an enhanced interaction between dynein and a spindle pole-localized protein due to modification of dynein, a dynein regulator or a spindle-pole protein. This altered interaction could recruit dynein complexes from the cytoplasm, or it could trap dynein complexes that have arrived at the spindle pole after walking along a microtubule. In fact, prior work found that ATP depletion or NDGA treatment prevents the release of dynein from spindle poles and thereby causes a similar accumulation at the poles [23,37–40], albeit with slower kinetics than what we observed here.

Inhibitors targeting both ubiquitin E1 and E2 enzymes cause an increase in dynein signal at spindle poles, suggesting that dynein localization is regulated by ubiquitination. Indeed, another inhibitor of Ubc13, BAY 11–7082 [41], similarly relocalized dynein (data not shown). However, recent in vitro studies demonstrated that BAY 11-7082 additionally inhibits the ubiquitin E1 enzyme [42]. As BAY 11-7082 shares structural similarity with NSC697923, it is plausible that dynein relocalization induced by NSC697923 is actually also due to inhibition of the ubiquitin E1 enzyme. Alternatively, our observation that TAK-243, a more potent [30,31] and presumably more specific ubiquitin E1 inhibitor, does not cause the same alteration in dynein localization suggests that there may be another cellular target shared by both NSC697923 and PYR-41. Both PYR-41 and NSC697923 are known to have off-target effects. PYR-41 has been shown to non-specifically cross-link proteins [43] and NSC697923 inhibits the activity of several deubiquitinases in vitro [44]. Additionally, it is important to note that TAK-243 treatment does not obviously affect the mitotic spindle on the time scales analysed here. By contrast, PYR-41 treatment causes the spindle poles to move inwards towards the DNA (figure 5b). As an inhibitor of the most upstream step in the ubiquitination pathway, PYR-41 should inhibit almost all cellular ubiquitination. Thus, it is particularly surprising that NSC697923 treatment, which should only inhibit the subset of ubiquitination events catalysed by Ubc13, results in potent disassembly of the mitotic spindle (figure 1b). Therefore, the distinct microtubule phenotypes we observe after PYR-41 or NSC697923 treatment may be further evidence of off-target effects of one or both compounds.

Regardless of the precise mechanism used, the rapid relocalization of dynein following the addition of NSC697923 and PYR-41 indicates a highly dynamic and precise regulatory network controlling dynein function.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Molecular biology

GFP-tagged constructs for expression in human cells were generated by cloning the human cDNA into a pBABEblast vector containing an N-terminal LAP tag (GFP-TEV-S) as described previously [45].

4.2. Cell culture and cell line generation

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare), 100 units ml−1 penicillin, 100 units ml–1 streptomycin and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C with 5% CO2. TS20 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare), 2 mM l-glutamine and MEM Non-essential amino acids at 35°C with 5% CO2.

HeLa cells expressing mouse DHC–GFP were obtained from MitoCheck [46]. HeLa cells expressing GFP-tagged Tctex-type3, ARP1, Lis1, Nde1, CENP-A and CSAP were generated by retroviral infection followed by Blasticidin selection and single-cell sorting. HeLa cells expressing GFP-ZW10 were a gift from Geert Kops (Hubrecht Institute). TS20 cells are a BALB/3T3 cell line containing a temperature-sensitive mutation in the ubiquitin E1 enzyme, Uba1, and were a gift from Nianli Sang (Drexel University). For experiments at the restrictive temperature, TS20 cells were cultured at 39°C for 8 h before treating with PYR-41 for 15 min and then fixing for immunofluorescence.

4.3. Chemicals

All chemicals were resuspended in DMSO. NSC697923 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 20 µM. Nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 50 nM. MG132 (EMD Biosciences) was used at 10 µM. CC0651 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used at 50 µM. Taxol (Life Technologies) was used at 1 µM. PYR-41 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used at 20 µM. TAK-243 (formerly MLN7243) was a gift from Hidde Ploegh (Whitehead Institute) and used at 25 µM. PR-619 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 100 µM. ZM447439 (R&D Systems) was used at 2 µM. VX680 (LC Laboratories) was used at 2.5 µM. Flavopiridol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used at 5 µM. AZ3146 (Tocris) was used at 2 µM. BI2536 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used at 10 µM. Okadaic acid (VWR) was used at 1 µM. To dose cells, drugs were diluted in fresh media and then added to the cells. For immunofluorescence, cells were dosed for 15 min before fixation.

4.4. Immunofluorescence

Cells were plated on glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PHEM buffer (60 mM PIPES, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA and 4 mM MgSO4, pH 7) for 10 min. Blocking and all antibody dilutions were performed using AbDil (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 3% BSA and 0.1% NaN3, pH 7.5). PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS-TX) was used for washes. GFP-Booster (Chromotek; 1 : 200 dilution) was used to amplify the fluorescence of the GFP-tagged transgenes. DM1A was used to stain the microtubules (Sigma-Aldrich; 1 : 3000 dilution). For staining of NuMA, ab36999 (Abcam) was used at a 1 : 500 dilution. For staining of Spindly, rabbit anti-Spindly [47] (a gift from Erich Nigg and Anna Santamaria, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry) was used at a 1 : 1000 dilution. For staining of MAD1, ab5783 (Abcam) was used at a 1 : 1000 dilution. For staining of MAD2, A300-301A (Bethyl Laboratories) was used at 1 µg ml−1. For staining of Bub1, ab54893 (Abcam) was used at a 1 : 500 dilution. For staining of ZW10, ab21582 (Abcam) was used at 1 µg ml−1. Cy3- and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used at a 1 : 300 dilution. DNA was visualized by incubating cells in 1 µg ml−1 Hoechst-33342 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS-TX for 10 min. Coverslips were mounted using PPDM (0.5% p-phenylenediamine and 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.8, in 90% glycerol).

4.5. Fluorescence microscopy

Images were acquired on a DeltaVision Core microscope (Applied Precision) equipped with a CoolSnap HQ2 CCD camera (Photometrics). A 100×, 1.4 NA U-PlanApo objective (Olympus) was used to image fixed cells, and a 60×, 1.42 NA Plan Apo N objective (Olympus) was used for live-cell imaging. Images were deconvolved and maximally projected. The fluorescence is not scaled equivalently in each panel to clearly demonstrate the qualitative localization of each protein.

To quantify the spindle pole accumulation frequency of dynein heavy chain, each replicate included 100 cells for each condition. The percentage of mitotic cells with clear, strong foci of the dynein-GFP signal on the spindle poles was denoted. 3-4 biological replicates were analysed for each condition and the mean percentage of cells (±s.d.) with strong dynein signal for those replicates was plotted. For ZW10 and MAD1, 2 biological replicates were analysed for each condition and the mean percentage of cells (±s.d.) with spindle pole-localized signal for those replicates was plotted.

Line scans were generated through the ‘Plot profile’ function in ImageJ, using maximally projected, but not deconvolved, images.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Chelsea Backer, Tomomi Kiyomitsu, Geert Kops, Erich Nigg, Hidde Ploegh, Nianli Sang, Anna Santamaria and Kuan-Chung Su for reagents. We thank the members of the Cheeseman lab for discussions and input on the manuscript.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

J.K.M. carried out all experiments and analyses. Both authors conceived of and designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from The Harold G. & Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation and the NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM088313, GM108718 and R35GM126930) to I.M.C., and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant no. (1122374) to J.K.M.

References

- 1.Neuwald AF, Aravind L, Spouge JL, Koonin EV. 1999. AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 9, 27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts AJ, Kon T, Knight PJ, Sutoh K, Burgess SA. 2013. Functions and mechanics of dynein motor proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 713–726. ( 10.1038/nrm3667) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kardon JR, Vale RD. 2009. Regulators of the cytoplasmic dynein motor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 854–865. ( 10.1038/nrm2804) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hornbeck PV, Zhang B, Murray B, Kornhauser JM, Latham V, Skrzypek E. 2015. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D512-D520. ( 10.1093/nar/gku1267) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danielsen JM, Sylvestersen KB, Bekker-Jensen S, Szklarczyk D, Poulsen JW, Horn H, Jensen LJ, Mailand N, Nielsen ML. 2011. Mass spectrometric analysis of lysine ubiquitylation reveals promiscuity at site level. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M110 003590 ( 10.1074/mcp.M110.003590) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim W, et al. 2011. Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol. Cell. 44, 325–340. ( 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumpkin RJ, Gu H, Zhu Y, Leonard M, Ahmad AS, Clauser KR, Meyer JG, Bennett EJ, Komives EA. 2017. Site-specific identification and quantitation of endogenous SUMO modifications under native conditions. Nat. Commun. 8, 1171 ( 10.1038/s41467-017-01271-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertins P, et al. 2013. Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat. Methods. 10, 634–637. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2518) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Udeshi ND, Svinkina T, Mertins P, Kuhn E, Mani DR, Qiao JW, Carr SA. 2013. Refined preparation and use of anti-diglycine remnant (K-epsilon-GG) antibody enables routine quantification of 10,000s of ubiquitination sites in single proteomics experiments. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 825–831. ( 10.1074/mcp.O112.027094) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner SA, Beli P, Weinert BT, Nielsen ML, Cox J, Mann M, Choudhary C. 2011. A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M111 013284 ( 10.1074/mcp.M111.013284) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner SA, et al. 2012. Proteomic analyses reveal divergent ubiquitylation site patterns in murine tissues. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 1578–1585. ( 10.1074/mcp.M112.017905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon YT, Ciechanover A. 2017. The ubiquitin code in the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 42, 873–886. ( 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erpapazoglou Z, Walker O, Haguenauer-Tsapis R. 2014. Versatile roles of k63-linked ubiquitin chains in trafficking. Cells 3, 1027–1088. ( 10.3390/cells3041027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann RM, Pickart CM. 1999. Noncanonical MMS2-encoded ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme functions in assembly of novel polyubiquitin chains for DNA repair. Cell 96, 645–653. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80575-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komander D, Rape M. 2012. The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229. ( 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan K, et al. 2015. The deubiquitinating enzyme complex BRISC is required for proper mitotic spindle assembly in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 210, 209–224. ( 10.1083/jcb.201503039) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Liu M, Li D, Ran J, Gao J, Suo S, Sun SC, Zhou J. 2014. CYLD regulates spindle orientation by stabilizing astral microtubules and promoting dishevelled-NuMA-dynein/dynactin complex formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 2158–2163. ( 10.1073/pnas.1319341111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickart CM, Fushman D. 2004. Polyubiquitin chains: polymeric protein signals. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 8, 610–616. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.09.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulvino M, Liang Y, Oleksyn D, DeRan M, Van Pelt E, Shapiro J, Sanz I, Chen L, Zhao J. 2012. Inhibition of proliferation and survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by a small-molecule inhibitor of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13-Uev1A. Blood 120, 1668–1677. ( 10.1182/blood-2012-02-406074) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dionne MA, Howard L, Compton DA. 1999. NuMA is a component of an insoluble matrix at mitotic spindle poles. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 42, 189–203. ( 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)42:3%3C189::AID-CM3%3E3.0.CO;2-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monda JK, Cheeseman IM. In press. Nde1 promotes diverse dynein functions through differential interactions and exhibits an isoform-specific proteasome association. Mol. Biol. Cell. mbcE18070418 ( 10.1091/mbc.E18-07-0418) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Backer CB, Gutzman JH, Pearson CG, Cheeseman IM. 2012. CSAP localizes to polyglutamylated microtubules and promotes proper cilia function and zebrafish development. Mol. Biol. Cell. 23, 2122–2130. ( 10.1091/mbc.E11-11-0931) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Famulski JK, Vos LJ, Rattner JB, Chan GK. 2011. Dynein/Dynactin-mediated transport of kinetochore components off kinetochores and onto spindle poles induced by nordihydroguaiaretic acid. PLoS ONE 6, e16494 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0016494) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang G, Lischetti T, Hayward DG, Nilsson J. 2015. Distinct domains in Bub1 localize RZZ and BubR1 to kinetochores to regulate the checkpoint. Nat. Commun. 6, 7162 ( 10.1038/ncomms8162) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buffin E, Lefebvre C, Huang J, Gagou ME, Karess RE. 2005. Recruitment of Mad2 to the kinetochore requires the Rod/Zw10 complex. Curr. Biol. 15, 856–861. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.052) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silio V, McAinsh AD, Millar JB. 2015. KNL1-Bubs and RZZ provide two separable pathways for checkpoint activation at human kinetochores. Dev. Cell. 35, 600–613. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caldas GV, Lynch TR, Anderson R, Afreen S, Varma D, DeLuca JG. 2015. The RZZ complex requires the N-terminus of KNL1 to mediate optimal Mad1 kinetochore localization in human cells. Open Biol. 5, 150160 ( 10.1098/rsob.150160) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lydeard JR, Schulman BA, Harper JW. 2013. Building and remodelling Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases. EMBO Rep. 14, 1050–1061. ( 10.1038/embor.2013.173) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceccarelli DF, et al. 2011. An allosteric inhibitor of the human Cdc34 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Cell 145, 1075–1087. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, et al. 2007. Inhibitors of ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), a new class of potential cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 67, 9472–9481. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0568) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyer ML, et al. 2018. A small-molecule inhibitor of the ubiquitin activating enzyme for cancer treatment. Nat. Med. 24, 186–193. ( 10.1038/nm.4474) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chowdary DR, Dermody JJ, Jha KK, Ozer HL. 1994. Accumulation of p53 in a mutant cell line defective in the ubiquitin pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 1997–2003. ( 10.1128/MCB.14.3.1997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lao T, Chen S, Sang N. 2012. Two mutations impair the stability and function of ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1). J. Cell. Physiol. 227, 1561–1568. ( 10.1002/jcp.22870) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKinley KL, Sekulic N, Guo LY, Tsinman T, Black BE, Cheeseman IM. 2015. The CENP-L-N complex forms a critical node in an integrated meshwork of interactions at the centromere–kinetochore interface. Mol. Cell. 60, 886–898. ( 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiyomitsu T, Cheeseman IM. 2012. Chromosome- and spindle-pole-derived signals generate an intrinsic code for spindle position and orientation. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 311–317. ( 10.1038/ncb2440) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiyomitsu T, Cheeseman IM. 2013. Cortical dynein and asymmetric membrane elongation coordinately position the spindle in anaphase. Cell. 154, 391–402. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arasaki K, Tani K, Yoshimori T, Stephens DJ, Tagaya M. 2007. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid affects multiple dynein-dynactin functions in interphase and mitotic cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 454–460. ( 10.1124/mol.106.029611) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howell BJ, McEwen BF, Canman JC, Hoffman DB, Farrar EM, Rieder CL, Salmon ED. 2001. Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin drives kinetochore protein transport to the spindle poles and has a role in mitotic spindle checkpoint inactivation. J. Cell Biol. 155, 1159–1172. ( 10.1083/jcb.200105093) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan X, Li F, Liang Y, Shen Y, Zhao X, Huang Q, Zhu X. 2003. Human Nudel and NudE as regulators of cytoplasmic dynein in poleward protein transport along the mitotic spindle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1239–1250. ( 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1239-1250.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang ZY, Guo J, Li N, Qian M, Wang SN, Zhu XL. 2003. Mitosin/CENP-F is a conserved kinetochore protein subjected to cytoplasmic dynein-mediated poleward transport. Cell Res. 13, 275–283. ( 10.1038/sj.cr.7290172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strickson S, Campbell DG, Emmerich CH, Knebel A, Plater L, Ritorto MS, Shpiro N, Cohen P. 2013. The anti-inflammatory drug BAY 11–7082 suppresses the MyD88-dependent signalling network by targeting the ubiquitin system. Biochem. J. 451, 427–437. ( 10.1042/BJ20121651) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koszela J, et al. 2018. Real-time tracking of complex ubiquitination cascades using a fluorescent confocal on-bead assay. BMC Biol. 16, 88 ( 10.1186/s12915-018-0554-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapuria V, Peterson LF, Showalter HD, Kirchhoff PD, Talpaz M, Donato NJ. 2011. Protein cross-linking as a novel mechanism of action of a ubiquitin-activating enzyme inhibitor with anti-tumor activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82, 341–349. ( 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritorto MS, et al. 2014. Screening of DUB activity and specificity by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 5, 4763 ( 10.1038/ncomms5763) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheeseman IM, Desai A. 2005. A combined approach for the localization and tandem affinity purification of protein complexes from metazoans. Science's STKE 2005, pl1 ( 10.1126/stke.2662005pl1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutchins JR, et al. 2010. Systematic analysis of human protein complexes identifies chromosome segregation proteins. Science 328, 593–599. ( 10.1126/science.1181348) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan YW, Fava LL, Uldschmid A, Schmitz MH, Gerlich DW, Nigg EA, Santamaria A. 2009. Mitotic control of kinetochore-associated dynein and spindle orientation by human Spindly. J. Cell Biol. 185, 859–874. ( 10.1083/jcb.200812167) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.