Abstract

Background

IL-17 plays a pathogenic role in asthma. ST2− iILC2s (inflammatory group 2 innate lymphoid cells) driven by IL-25 can produce IL-17, while ST2+nILC2s (natural ILC2s) produce few IL-17.

Objective

We characterized the ST2+IL-17+ILC2s during lung inflammation and determined the pathogenesis and molecular regulation of ST2+IL-17+ILC2s.

Methods

Lung inflammation was induced by papain or IL-33. IL-17 production by lung ILC2s from wild-type, Rag1− /−, Rorcgfp/gfp and Ahr−/− mice was examined by flow cytometry. Bone marrow transfer experiment was performed to evaluate hematopoietic MyD88 signaling in regulating IL-17 production by ILC2s. mRNA expression of IL-17 was analyzed in purified naïve ILC2s treated with IL-33, leukotrienes and inhibitors for NFAT, p38, JNK or NF-κB. The pathogenesis of IL-17+ILC2s was determined by transferring wild-type or Il17−/−ILC2s to Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice which were further induced lung inflammation. Finally, the expression of 106 ILC2 signature genes was compared between ST2+IL-17+ILC2s and ST2+IL-17−ILC2s.

Results

Papain or IL-33 treatment boosted IL-17 production from ST2+ILC2s (referred to by us as ILC217s), but not ST2−ILC2s. Ahr, but not RORγt, facilitated the production of IL-17 by ILC217s. Hematopoietic compartment of MyD88 signaling is essential for the induction of ILC217s. IL-33 works in synergy with leukotrienes, which signal through NFAT activation, to promote IL-17 in ILC217s. Il17−/− ILC2s were less pathogenic in lung inflammation. ILC217s concomitantly expressed IL-5 and IL-13 but expressed few GM-CSF.

Conclusion

During lung inflammation, IL-33 and leukotrienes synergistically induce ILC217s. ILC217s are highly pathogenic and unexpected source for IL-17 in lung inflammation.

Keywords: asthma, group 2 innate lymphoid cells, IL-17

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common inflammatory diseases of the airways. The initiation and progression of asthma is driven by various pro-inflammatory cytokines, which induce recruitment of eosinophils, neutrophils and macrophages to the airways. The inflammation storm further stimulates lung structural cells including epithelial cells to produce chemokines and mucins, which results in tissue remodeling and airway hyperresponsiveness 1–3 .

Type 2 cytokines, typically IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, have been indicated to be key factors associated with the pathology of asthma 3, 4. IL-5 has been shown to be crucial for development, maturation and survival of eosinophils 5–7. IL-13 induces airway hyperresponsiveness, stimulates the chemokine production by epithelial cells and promotes tissue remodeling 2, 8, 9. Th2 cells, one of the T helper cell subsets, are well known to be the source for type 2 cytokines 10. Recently, more and more research has proved group 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2), a population of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), plays fundamental roles in type 2 immune responses in anti-helminth infections and allergic diseases 11–17.

The development, maintenance and expansion of ILC2s are supported by a group of cytokines including IL-2, IL-7, TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33 11, 12, 18–20. Receptors for IL-33 and IL-25 are ST2 and IL-17RB respectively. IL-33 and IL-25 accumulate two distinct populations of ILC2s 21–23. IL-25 initially boosts iILC2s (inflammatory ILC2, Lin−IL-17RBhighKLRG1highST2−) in the lung, while IL-33 expands nILC2s (natural ILC2, Lin−IL-17RBlowKLRG1intST2+)21. Compared to nILC2s, iILC2s produce IL-17 and express higher levels of retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan receptor-γt (RORγt), which is a master regulator for IL-17 transcription in many types of immune cells 21, 23.

CysLTs (cysteinyl leukotrienes), composed of LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4, have been found to be increased in different provoked asthmatic responses by promoting chemotaxis of leukocytes and smooth muscle contraction 24–26. It has been reported recently that cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (Cysltr1), the best characterized receptor for CysLTs, is expressed on ILC2s at a higher level than Th2 cells and eosinophils 27, 28. And both LTC4 and LTD4 rapidly and potently stimulate the production of type 2 cytokines by ILC2 synergistically with IL-33 through NFAT signaling pathway 27–29.

Besides IL-5 and IL-13, IL-17 has been indicated to a pathogenic factor in asthma 30. IL-17 can be detected in the lungs, sputum and BALF (bronchoalveolar lavage fluids) of asthmatic patients 31, 32. And the level of IL-17 is associated with the severity of disease 32. Previous study has identified a population of memory/effector IL-17+Th2 cells, which were found to be increased in peripheral blood of patients with atopic asthma 33. The IL-17+Th2 cells are GATA3+RORγt+ cells that concomitantly produce IL-5 and IL-13 33. Notably, IL-17+Th2 cells induced more severe asthma than classical Th2 and Th17 cells, suggesting the IL-17+Th2 cells are more pathogenic 33. One of the mechanisms could be the combinatorial effect of IL-17 and type 2 cytokines in enhancing chemokine production by lung epithelial cells 33. Another study has shown exogenous IL-17 exacerbates IL-33-induced asthma by inducing neutrophilic inflammation through CXCR2 signaling 34. Therefore, it is important to investigate source for IL-17 in the lung and determine molecular regulation of IL-17 production during asthma.

In this study, we have found papain or IL-33 treatment boosted IL-17 production from ST2+ILC2s (referred to by us as ILC217s), but not ST2− ILC2s. ILC217s are the major source for IL-17 in IL-33-induced lung inflammation. ILC217s are induced in mucosal tissues independently of the adaptive immune system. The induction of ILC217s is independent of RORγt. And we have proved aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) facilitates the production of IL-17 by ILC217s. IL-33 works with leukotrienes synergistically to promote mRNA expression of IL-17. IL-17-deficient ILC2s are less pathogenic than wild-type ILC2s in recruiting leukocyte infiltration to the airways in IL-33-induced lung inflammation in Rag2−/− IL2rg−/− mice. Characterization of ILC217s with ILC2 signature markers reveals ILC217s are IL-5+IL-13+ cells but express few GM-CSF. Our finding highlights ILC217 to be a previously unappreciated source for IL-17, and contribute to the progression of asthma.

Methods

Mice

Wild-type mice and Rag1−/− mice were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Thy1.1 mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory. Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice were purchased from Taconics. Il17e−/− (B6; 129S5-Il25tm1Lex/Orl) mice were purchased from EMMA. Rorcgfp/gfp 50 , MyD88−/− 56 and Ahr−/− mice 57 and IL-17A-GFP reporter mice 58 were generated previously. IL-17-deficient mouse was kindly provided by Dr. Hong Tang (Institute Pasteur of Shanghai, Chinese Academy of Science). All mice used in this study are on C57BL/6 background and maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions. All mice used in the experiments were 6–10 weeks old. Gender-matched male and female mice were used in the study. In IL-33-induced lung inflammation, in which BALF (bronchoalveolar lavage fluids) cells were analyzed, littermate female mice were used. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the institutional biomedical research ethics committee of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Induction of lung inflammation using IL-33 and papain

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 500ng recombinant murine IL-33 (BioLegend) or PBS for 4 consecutive days. In the “resting” protocol, the IL-33-treated mice were set for 12 days before analysis. In the “re-challenged” protocol, “rested” mice were injected with 500ng IL-33 for 2 days before analysis. For protease allergen papain model, mice were anesthetized by 1% sodium pentobarbital, followed by intranasal administration of papain (30ug, Calbiochem) in 30uL of PBS for 3 days in IL-17 blockade experiment in Rag1−/− mice and for 5 days in all the other experiments. .

Isolation of Lung lymphocytes

The lungs were dissected. After fat tissues and bronchus were removed, lungs were cut into pieces and digested in RPMI1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing DNase I (Sigma) (50U/ml) and collagenase VIII (Sigma) (250U/ml) at 37 oC for 30 min. The digested tissues were homogenized by vigorous shaking and passed through a 100 um cell strainer. Mononuclear cells were then harvested from the interphase of an 80% and 40% Percoll gradient after a spin at 2,500 rpm for 20 min at room temperature (RT).

Isolation of Large Intestinal Lamina Proprial Lymphocytes (LPLs)

The isolation of large intestinal lamina proprial lymphocytes was done as previously described 59. Briefly, large intestines were dissected. Fat tissues were removed. Intestines were cut open longitudinally and washed in PBS. Intestines were then cut into 3 pieces, washed and shaken in PBS containing 1 mM DTT for 10 min at RT. Intestines were incubated with shaking in PBS containing 30 mM EDTA and 10 mM HEPES at 37°C for 10 min for two cycles. The tissues were then digested in RPMI1640 medium (Invitrogen) containing DNase I (Sigma) (150 ug/ml) and collagenase VIII (Sigma) (150 U/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator for 1.5 hr. The digested tissues were homogenized by vigorous shaking and passed through 100um cell strainer. Mononuclear cells were then harvested from the interphase of an 80% and 40% Percoll gradient after a spin at 2500 rpm for 20 min at room temperature.

Flow Cytometry

Anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody was used to block the non-specific binding to Fc receptors before all surface stainings. Antibodies used for regular flow cytometry were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (eBioscience), except for anti-GATA3 (BD Biosciences), ant-Siglec-F (BD Biosciences) and anti-ST2 (MD Biosciences). For nuclear stainings, cells were fixed and permeabilized using a Mouse Regulatory T Cell Staining Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Antibodies used for 11 colors flow cytometry was purchased from BD Bioscience. For cytokine stainings, cells were stimulated by PMA (Sigma) (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (Sigma) (500 ng/ml) for 4 h. Brefeldin A (Sigma) (2μg/ml) was added for the last 2 h before cells were harvested for analysis. Dead cells were stained with live and dead violet viability kit (Invitrogen) and were gated out in analysis. Flow cytometry data were collected using the Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman) or BD FACSymphonyTM AS and analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.). Lineage markers (Lin) for Figures 1C–1D, 1F–1G, 2H–2I, 2M, 4G–I, S2, S6B-6E were CD3, B220, CD11b, CD11c, Gr-1, NK1.1 and FcεRI. “Lin” was CD3, B220, CD11b and CD11c for other figures unless otherwise described.

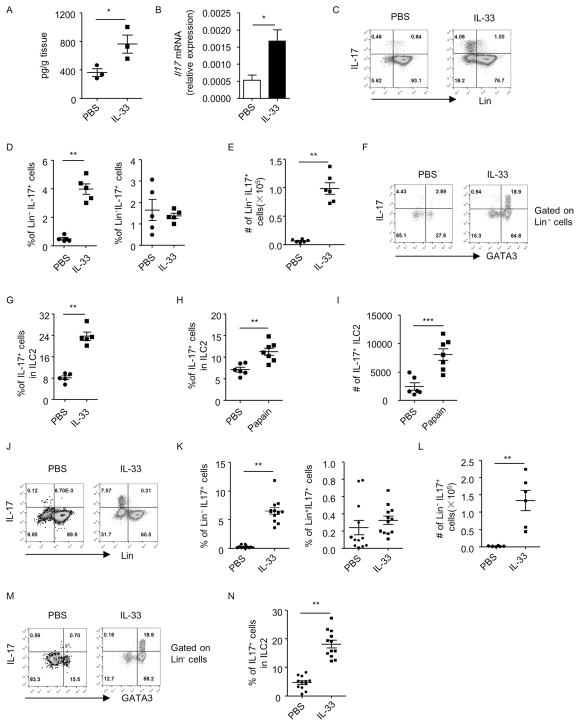

Figure 1. Lung inflammation induces IL-17 production by lung ILC2s independently of the adaptive immune system.

Lung inflammation was induced by IL-33 (A–G and J–N) or papain (H and I) in wild-type (A–I) or Rag1−/− (J–N) mice. Lung lymphocytes were isolated for analysis. (A) Cells were cultured in medium for 48h and supernatants were collected. Level of IL-17 was measured by ELISA and the amount of IL-17 normalized to the weight of the tissue was shown. (B) mRNA expression of IL-17 in lung lymphocytes was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. (C and J) The expression of lineage markers (Lin) and IL-17 gated on live lymphocytes from indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (D and K) The percentages of Lin− IL-17+ cells and Lin+IL-17+ cells gated on live lymphocytes were shown. Data are means±SEM. Cell numbers of Lin− IL-17+ cells (E and L) and IL-17+ILC2s (I) from the lung of individual mouse were shown. Data are means±SEM. (F and M) The expression of GATA3 and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (G, H and N) Percentages of IL-17+ cells in Lin− GATA3+ (ILC2) were shown. Data are means±SEM.

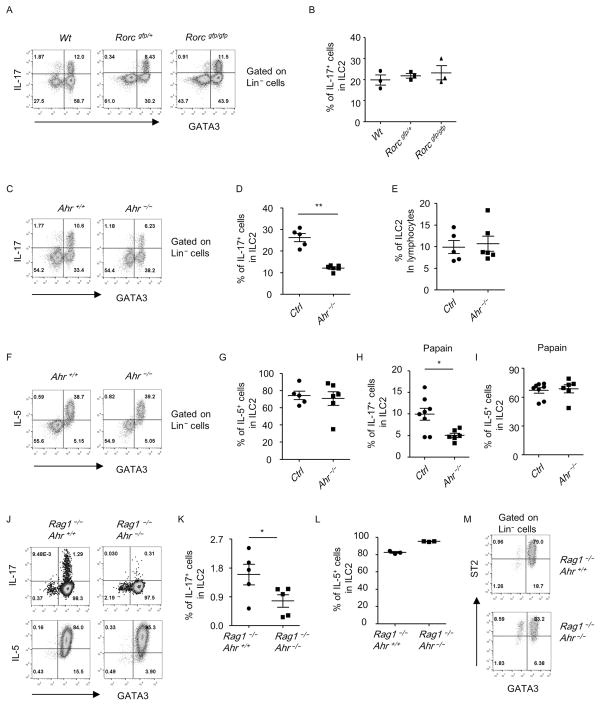

Figure 2. Ahr but not RORγt facilitates the induction of IL-17+ILC2s by IL-33.

(A–G) Mice with indicated genotypes were treated with IL-33 or papain (H and I). (A–I) Lung lymphocytes were isolated for analysis. (J to M) Lin− ST2+CD25+ ILC2s were purified and cultured with IL-7 and IL-33 for 7 days. (A, C, F, J and M) The expression of GATA3, ST2, IL-5, and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells of live lung lymphocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentages of IL-17+ (B, D, H and K) or IL-5+ (G, I and L) cells in Lin− GATA3+ (ILC2) from mice with indicated genotypes were calculated and shown. (E) The percentages of ILC2 in lymphocytes were shown. Ctrl included 2 Ahr+/− mice and 3 Ahr+/+ mice. (H and I) Ctrl includes 3 Ahr+/− mice and 5 Ahr+/+ mice. Error bars represent SEM. (A–M) Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

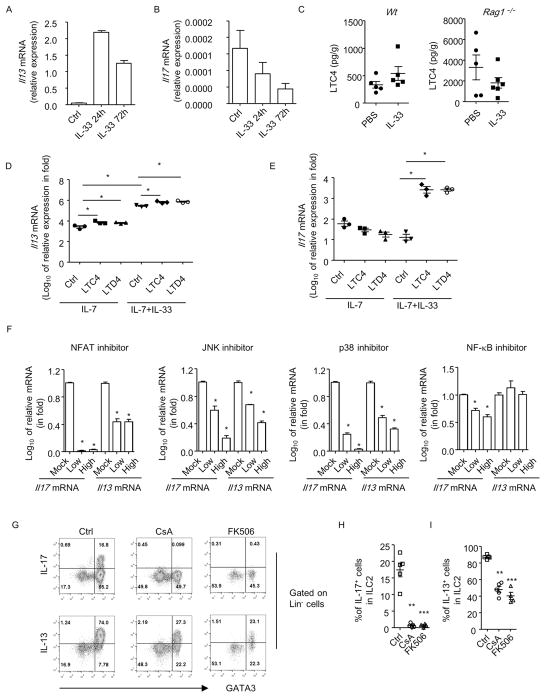

Figure 4. IL-33 and leukotrienes synergistically promote the mRNA expression of IL-17 in ILC2.

(A and B) ILC2s from naïve wild-type mice and cultured in the presence of IL-7 for 24 h. Cells were stimulated without or with IL-33 for another 24 h or 72 h before collected for analysis. (C) Levels of LTC4 in lung tissues were analyzed by ELISA. Level of LTC4 normalized to weight of lung tissue was shown. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (D and E) ILC2s were purified from naïve wild-type mice and cultured with IL-7 for 24 h. Cells were then treated with or without IL-33 for 24 hr. In some groups, LTC4 (100nM) or LTD4 (100nM) was added for the last 4 h before cells were collected for analysis. (F) Cells were treated with IL-7, IL-33 and LTC4 in the presence or absence of inhibitors for NFAT, JNK, p38 and NF-κB. The expressions of IL-17 or IL-13 mRNA were normalized to control group (Mock) respectively. Relative IL-17 and IL-13 mRNA expression in fold compared to control group was shown. (D–F) Data are means+SEM. Data are representative of triplicates from one experiment. Experiments have been repeated for 3 times. (G) Mice were treated with CsA or FK506 before and during IL-33 injection. Expression of IL-17, IL-13, GATA3 gated on Lin− cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (H and I) Percentages of IL-13+ and IL-17+ cells gated on ILC2s were shown. Data are means±SEM. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

In vitro culture of ILC2s

In vitro culturing of ILC2s was performed according to previous study 27. Lin− ST2+CD25+ ILC2s were purified from the lung and colon of naïve mice. Cells were cultured in 96-well plate in the presence of IL-7 (10ng/ml) for 24h. Cells were then treated with IL-33 (10ng/ml) for 24h or 72h. For treatment with inhibitors, p38 inhibitor SB203580 (Selleckchem, low, 10uM; high, 30uM), NF-κB inhibitor Bay11-7085 (Selleckchem, low, 0.06uM; high 0.1uM), JNK inhibitor SP600125 (Selleckchem, low, 10uM; high, 30uM) and NFAT inhibitor CsA (Abcam, low, 0.03uM; high, 0.6uM) was added together with IL-33 for 24h before analysis. In experiments with leukotrienes, LTC4 (100nM, Cayman) and LTD4 (100nM, Cayman) was added for the last 4h before analysis.

In vivo treatments with CsA or FK506

Mice were subcutaneously treated with 50ul of CsA (80mg/kg) or FK506 (8mg/kg) dissolved in 50% DMSO and 50% olive oil for 7 days before and during 500ng of IL-33 was injected i. p. for another 4 days.

Detection of LTC4 and IL-17 by ELISA

For measurement of LTC4, lung tissues were homogenized in 1ml PBS. The extract was centrifuged, and the LTC4 in the supernatant was measured by LTC4 ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Mouse IL-17A ELISA was developed using capture antibody (eBio17CK15A5, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and detection antibody (eBio17B7, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm was analyzed with a spectrophotometer (Biotek).

Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow cells were harvested from Thy1.2 wild-type and littermate MyD88−/−mice. Thy1.1 recipient mice were irradiated with 550rad twice with 5h interval. In parallel experiments, Thy1.1 wild-type mice were used as donor. Thy1.2 wild-type and littermate MyD88−/−mice were used as recipients. Recipient mice were intravenously injected with 5×106 bone marrow cells immediately after irradiation. 8 weeks later, mice were treated with PBS or IL-33 and sacrificed for analysis.

In vivo blockade of IL-17 or IL-25

Female mice were intraperitoneally treated with 500ng IL-33 for 4 consecutive days or intranasally treated with 30ug papain for 3 days to induce lung inflammation. Mice were sacrified for analysis 24h after the last dose of IL-33 or papain treatment. For in vivo blockade of IL-17, mice were injected i.p. with 250ug α-IL-17 antibody (BioXcell, BE0173-5MG) or rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at day 0 and day 2 of IL-33 or papain treatment. For in vivo neutralization of IL-25, a dose of 200ug α-IL-25 antibody (Biolegend, 35B) or rat IgG (Sangon Biotech) was used following the same protocol as above.

Induction of lung inflammation in Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice

Wild-type or Il17−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500ng IL-33 for 4 consecutive days and ILC2s (Lin−ST2+CD25+) from the lung and colon were sorted by flow cytometry (purity >98%). Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice were intravenously injected with 2 × 105 ILC2s purified from wild-type or Il17−/− mice and subsequently treated intraperitoneally with 500ng IL-33 on 4 consecutive days.

Analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF)

Mice were sacrificed, and a gavage needle connected to a 1-ml syringe containing 1 ml cold PBS was inserted into the exposed trachea. The PBS was injected, aspirated back into the syringe, and set aside on ice. The process was repeated once. BALF was then centrifuged at 4602 RCF for 3 min. Cells were re-suspended in 100ul PBS. A 5ul aliquot of BALF was used for the determination of total cell numbers and the rest was used for flow cytometric analysis.

Histological analyses

Tissues from left lung of mice were dissected and immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissues were then embedded in paraffin and sectioned longitudinally at 7 um. Sections were then processed for periodic acid-schiff (PAS) staining to evaluate mucin production using light microscope (Zeiss). Number of PAS+ bronchioles/bronchi structures on each section was quantified. Percentages of PAS+ bronchioles/bronchi structures among total bronchioles/bronchi structures were calculated.

PAS+ area in each analyzed bronchiole/bronchi structure was analyzed by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD USA). And the percentages of PAS+ area in total area of each analyzed bronchiole/bronchi structure were calculated. All the PAS+ bronchiole/bronchi structures on the section were analyzed in order to get an average percentage of PAS+ area per bronchiole/bronchi structure.

Measurement of Airway Responsiveness to Methacholine

ILC2s were purified from IL-33-treated wild-type or Il17−/− mice and expanded in vitro with IL-7 (10ng/ml) and IL-33 (10ng/ml) for 7 days. Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice were intravenously injected with 2 × 105 wild-type or Il17−/− ILC2s. Lung inflammation was then induced by 3 injections 500ng IL-33 daily and 1 injection of 30ug of papain intranasally. Methacholine challenge was performed 24 h after the last injection of papain. Lung resistance (RL) was measured through a computer-controlled FinePointe RC system (Buxco Electronics, Wilmington, NC) as described previously 60. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 60mg/kg pentobarbital i.p., and the trachea was cannulated with an 18-gauge metal needle connected to the RC system. Mice were ventilated mechanically at a frequency of 140 breaths/min with a tidal volume of 0.2 ml. Aerosolized methacholine was administered in 30 seconds in increasing concentrations (6.25, 12.5, 25 mg/ml of methacholine). RL was continuously computed by fitting flow, volume and pressure to an equation of motion.

Detection of mRNA by Real-time RT-PCR

RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was synthesized using GoScript™ Reverse Transcription kit (Promega). Real-time PCR was performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche). Reactions were run with the QuantStudio 7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The results were displayed as relative expression values normalized to β-actin. Primers used in this study were shown in Table S1.

Analyzing the expression of ILC2 signature genes by real-time RT-PCR

IL-17-GFP reporter mice were treated with 500ng IL-33 for 4 consecutive days. Lung lymphocytes were isolated and stimulated with PMA (Sigma) (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (Sigma) (500 ng/ml) for 4h. ILC217s (Lin−ST2+GFP+) and IL-17−ILC2s (Lin−ST2+GFP−) were sorted by flow cytometry. Each biological sample was pooled from 2–3 mice. RNA was extracted and the expression of ILC2 signature genes was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Relative expression of genes was analyzed by normalization to β-actin. Genes consistently differentially expressed with more than 1.5 folds was confirmed with another 2 biological repeats by real-time RT-PCR.

Statistical Methods

Unless otherwise noted, statistical analysis was performed with the unpaired Mann Whitney U-test on individual biological samples using GraphPad Prism 5.0 program. Data from such experiments are presented as mean values ± SEM; *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant;**p<0.01;***p<0.001.

Results

IL-33 induces IL-17-producing ILC2 independently of the adaptive immune system

When mice were treated with IL-33 in vivo, we observed an increased production of IL-17 from lymphocytes in the lung (Figure 1A). Consistently, mRNA expression of IL-17 in lung lymphocytes was significantly higher in IL-33-treated mice than control (Figure 1B). Using flow cytometry analysis, we found the majority of IL-17 was produced from Lineage− (Lin−) cells (Figure 1C). Both the percentage and cell number of Lin− IL-17+ cells were increased upon IL-33 treatment (Figures 1D and 1E), while the percentage of Lin+IL-17+ lymphocytes was similar compared to control group. Intriguingly, we found most IL-17+ cells were Lin− GATA3+ cells (Figure 1F), which match the identity of ILC2s known to be expanded by IL-33. The Lin− GATA3+IL-17+ cells highly expressed markers for ILC2s including Thy1, CD127, Sca-1, CD25, KLRG1 and PD-1 35, 36, compared to Lin− GATA3− non-ILC2s (Figure S1). This suggests IL-33-induced Lin− GATA3+IL-17+ cells are indeed ILC2s. Notably, ILC2s produced limited amount of IL-17 under the steady-state, but acquired the ability to produce significantly higher amount of IL-17 after challenged with IL-33 (Figures 1F and 1G). The above data suggest IL-33 promotes IL-17 production from ILC2s, which are the major source for IL-17 among lung lymphocytes after IL-33 injection. In papain-induced lung inflammation, we also observed induction of IL-17 expression from ILC2s (Figures 1H and 1I), although in a lesser degree compared to IL-33-injected mice (Figure 1G).

In order to determine if the induction of IL-17-producing-ILC2s by IL-33 is dependent on the adaptive immune system, we injected IL-33 to Rag1−/− mice. We similarly observed an increased percentage and total cell number of Lin− IL-17+ cells in lung lymphocytes of IL-33-treated Rag1−/− mice (Figures 1J, 1K and 1L). No enhancement in the percentage of Lin+IL-17+ cells was found (Figure 1K). And IL-17 was mainly produced by Lin− GATA3+ILC2s upon IL-33 injection (Figure 1M). The IL-17 production gated on ILC2s from IL-33-injected mice was significantly increased compared with PBS-treated group, which has barely any IL-17+ILC2s (Figures 1M and 1N). The above data suggest IL-33 enhances IL-17 production from ILC2s independently of the adaptive immune system.

In addition to the lung, systemic administration of IL-33 to mice induced IL-17 production from Lin− cells in the large intestine but not in bone marrow or mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) despite an expansion of ST2+ILC2s in all analyzed organs (Figures S2A–S2C). IL-17 production within ILC2s in the large intestine showed a trend of enhancement in wild-type mice, and this was significant in Rag1−/− mice, with a smaller extent than the lung (Figures 1N, S2D–S2F). We therefore focused on the biology of IL-33-induced IL-17+ILC2s in the lung. The above data imply a tissue-specific feature for the induction of IL-17+ILC2s by IL-33.

The induction of IL-17-producing-ST2+ILC2s is independent of RORγt

RORγt has been known to be a master regulator for IL-17 expression in various types of immune cells 37−39. And ST2− iILC2s expanded by IL-25 express RORγt and secrete IL-17 21. We observed IL-33 specifically expanded ST2+IL-17+ cells but not ST2− IL-17+ cells in the lung (Figures S3A and S3B). Besides, IL-17 derived from Lin− ST2− cells was significantly less than IL-17 derived from Lin− ST2+ cells (Figures S3A and S3B). And neither ST2+IL-17+ nor ST2− IL-17+ driven by IL-33 expressed RORγt (Figures S3C and S3D). We also confirmed that in papain-induced lung inflammation, IL-17 expression was induced in ST2+ILC2 but not ST2− ILC2 (Figures S3E and S3F).

To further determine if RORγt was required for the induction of ST2+IL-17+ILC2s by IL-33, we injected IL-33 to Rorcgfp/gfp (Rorγt-deficient) mice and control Rorcgfp/+or wild-type mice. We observed no defective IL-17 induction from ILC2s by IL-33 in the lung of Rorcgfp/gfp compared to Rorcgfp/+or wild-type mice (Figures 2A and 2B). And the IL-17+ILC2s in Rorcgfp/+ and Rorcgfp/gfp mice were ST2+ (Figure S3G). The above data suggest the IL-33-induced IL-17+ILC2s are independent of RORγt and distinct from iILC2s. In order to describe the IL-33-induced ST2+IL-17+ILC2 more briefly, we name these cells as ILC217 in this study.

Ahr facilitates IL-17 production by ILC217s

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) is highly expressed by Th17 cells and has been demonstrated to promote transcription of Th17 cytokines in many types of immune cells by directly binding to the promoter of IL-17 or through interaction with RORγt 40−43. We thus investigated if Ahr affected the induction of ILC217s by IL-33. We treated Ahr-deficient mice or littermate wild-type or Ahr+/− mice with IL-33. Strikingly, the induction of IL-17 from ILC2s by IL-33 in the lung of Ahr−/− mice was significantly reduced compared to control mice (Figures 2C and 2D). The IL-17+ILC2s in Ahr+/− and Ahr−/− mice were ST2+ (Figure S3H). This suggests Ahr facilitates the induction of ILC217s by IL-33. The percentage of ILC2s in the lung, as well as IL-5 production by ILC2s was comparable between Ahr−/− mice and control group (Figures 2E–2G), indicating Ahr has no impact on expansion of ILC2s or expression of type 2 cytokines by ILC2s in response to IL-33. The reliance of IL-17 but not IL-5 production by ILC2s on Ahr was similarly observed in papain-induced lung inflammation (Figures 2H and 2I).

We then investigated if Ahr regulated IL-17 production from ST2+ILC2s in the absence of other immune or non-immune cells. We purified ST2+ILC2s from naïve Rag1−/−Ahr−/− mice or Rag1−/− mice, and treated the cells with IL-7 and IL-33 in vitro. In this culture system, we avoided the effect of non-ILC2s which may indirectly affect IL-17 production from ILC2s. After 7 days of culture, IL-17 was readily detectable from ILC2s in the control group (Figure 2J). Notably, IL-17 expression from Ahr-deficient ILC2s was significantly less than control group (Figures 2J and 2K). Nevertheless, Ahr-deficient ILC2s exhibited no defective IL-5 expression compared to control ILC2s (Figures 2J and 2L). ILC2s maintained ST2 expression during in vitro expansion (Figure 2M). The above data indicate Ahr regulates the induction of ILC217s by IL-33 independently of other types of cells.

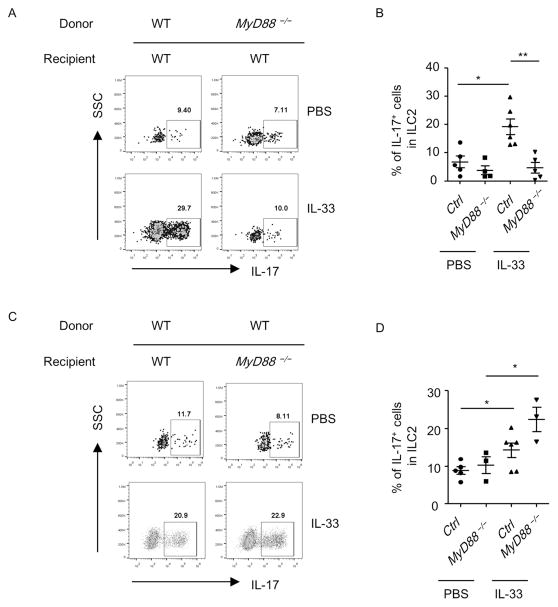

MyD88 signaling from the hematopoietic compartment is essential for the induction of ILC217

MyD88 signaling has been known to be the key molecule mediating downstream signals of IL-33 44. We utilized MyD88-deficient mouse to perform bone marrow transfer experiment to determine if hematopoietic or non-hematopoietic system was essential for the induction of ILC217s by IL-33.

Under the steady-state, IL-17 production from ILC2s was comparably low in wild-type and MyD88-deficient mice gated on ILC2s from the donor origin (Figures 3A and 3B). After IL-33 treatment, ILC2s from MyD88-deficient donors exhibited defective induction of IL-17 compared to ILC2s from wild-type donors (Figures 3A and 3B), suggesting MyD88 signaling from the hematopoietic cells is essential for the induction of ILC217s in the lung. In contrast, the expression of IL-17 from wild-type ILC2 donor cells was similarly induced by IL-33 in wild-type and MyD88-deficient recipients (Figures 3C and 3D), suggesting MyD88-signaling from non-hematopoietic cells is dispensable for the induction of ILC217s in the lung by IL-33.

Figure 3. MyD88 from the hematopoietic compartment is required for the induction of ILC217s.

The expression of IL-17 gated on Thy1.2+Lin− GATA3+ (ILC2) (A) or Thy1.1+ILC2 (C) of the donor origin was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B and D) Percentages of IL-17 gated on ILC2 of the donor origin were shown. Data are means±SEM. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Sustained IL-33 signal is essential for the maintenance of ILC217s

IL-33 challenged ILC2 has been reported to sustain in the lung for up to 60 days without continuous supplement of endogenous or exogenous IL-33 45. We therefore questioned if ILC217s would retain in the lung after we stopped IL-33 treatment for a period of time. We designed a “resting” protocol in which we injected wild-type mice with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days and analyzed cytokine production from ILC2s 12 days later. We found the percentage of IL-17 expression from ILC2s significantly declined in “rested” mice compared to mice freshly challenged with IL-33 (Figures S4A and S4B). And the induction of IL-17 from ILC2s could be achieved again when we re-challenged rested mice with IL-33 (Figures S4A and S4B). The above data suggest continuous signal of IL-33 is required for the maintenance of ILC217s.

Leukotrienes and IL-33 synergistically induce the mRNA expression of IL-17 in ILC2

The reliance of ILC217 on IL-33 signaling led us to question that IL-33 could directly drive the mRNA expression of IL-17 in ILC2s. To test this, we purified ILC2s from naïve wild-type mice and stimulate them with or without IL-33 in vitro in the presence of IL-7 to maintain the survival of ILC2s. Intriguingly, while IL-33 efficiently induced mRNA expression of IL-13 (Figure 4A), no enhancement of IL-17 mRNA in ILC2s was observed with either short (24h) or long term (72h) stimulation with IL-33 (Figure 4B). This suggests IL-33 alone doesn’t induce mRNA expression of IL-17 in ILC2s.

Leukotrienes have been shown to stimulate production of type 2 cytokines by ILC2s through inducing calcium influx and activating NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells) 27. We thus determined if leukotrienes could induce the mRNA expression of IL-17 in ILC2s. Consistently, LTC4 could be detected in lung tissues of both wild-type and Rag1−/−mice, although injection of IL-33 didn’t significantly alter the level of LTC4 (Figure 4C).

We found both LTC4 and LTD4 efficiently enhanced mRNA level of IL-13 in ILC2s purified from naïve mice, which was consistent with previous reports (Figure 4D). Surprisingly, no induction of IL-17 mRNA was observed with LTC4 or LTD4 treatment (Figure 4E), suggesting leukotriene alone doesn’t drive the mRNA expression of IL-17 in ILC2s. However, in the presence of IL-33, both LTC4 and LTD4 greatly enhanced mRNA level of IL-17 in ILC2s (Figure 4E), with more than 100 fold compared to IL-33 alone or leukotriene alone (Figure 4E). This synergistic effect of leukotrienes and IL-33 was also obvious for the induction of IL-13 mRNA expression in ILC2s (Figure 4D). Nevertheless, the combinatorial effect of the two to induce IL-13 production by ILC2s was not so striking compared to IL-33 alone, which is already a strong inducer for IL-13 expression (Figure 4D). However, both leukotrienes and IL-33 are essentially required for the induction of IL-17 mRNA expression in ST2+ILC2s.

Cysltr1 (cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1) has been reported to signal through NFAT and PKC (protein kinase C) 27, 46. And IL-33 activates multiple pro-inflammatory cascades including MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) 47. We then treated ILC2s with inhibitors for key signaling molecules in the presence of LTC4 and IL-33. We found cyclosporine A (CsA), an inhibitor of NFAT signaling, dramatically abolished the induction of IL-17 in ILC2s (Figure 4F). CsA also significantly inhibited the mRNA expression of IL-13 in ILC2s, but to a lesser degree compared to the inhibitory effect on IL-17, consistent with a milder effect of leukotrienes to boost IL-13 in the presence of abundant IL-33 (Figure 4F). Similarly, in vivo blockade of NFAT signaling with CsA or FK506 profoundly diminished the induction of ILC217s, while IL-13 expression by ILC2s was affected at a lesser extent (Figures 4G–4I) 48. Inhibitors for p38 and JNK suppressed mRNA expression of both IL-17 and IL-13 in a dose dependent manner (Figure 4F). While inhibitor for NF-κB slightly but significantly inhibited IL-17 expression in ILC2s, it had no impact on expression of IL-13 at the same dose (Figure 4F). The above data suggest NFAT signaling is essential for the induction of ILC217s. And multiple signaling cascades downstream of IL-33, including NF-κB, JNK and p38, are collectively supportive for IL-17 mRNA expression in ILC2s.

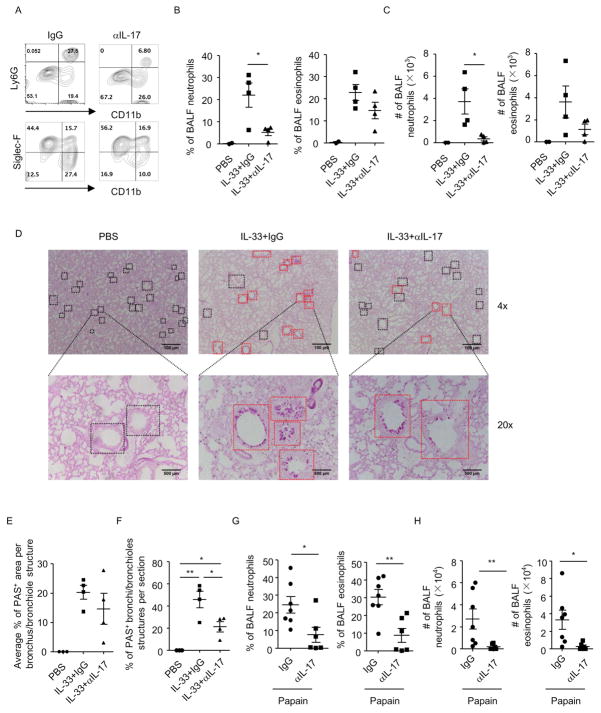

ILC217s play a pathogenic role in IL-33-induced lung inflammation

Our finding suggests ILC2s expanded by IL-33 serve as an endogenous source for IL-17. We thus evaluated the pathogenicity of the ILC217s in IL-33-induced lung inflammation in Rag1−/−mice, in which we could limit the role of IL-33 more stringently to ILC2s. We found depletion of IL-17 by neutralization antibody significantly reduced the percentage and cell number of neutrophils in the BALF (Figures 5A–5C). Percentage and cell number of eosinophils in the BALF showed a trend of downregulation after depletion of IL-17, but the change was not significant compared to IgG-treated group (Figures 5A–5C). We then evaluated mucin production in lung epithelial cells by periodic acid-schiff (PAS) staining. Although no difference was found in the percentage of PAS+ area at a per-bronchus/bronchiole level (Figures 5D and 5E), number of PAS+ bronchi/bronchioles was significantly lower in IL-17-depleted mice than IgG group in IL-33-treated mice (Figures 5D and 5F). This suggests mucin-producing lung epithelial cells are less disseminated in IL-17-depleted mice than control after IL-33 treatment, indicating a restriction of the pathology after IL-17 neutralization. Notably, blockade of IL-17 in Rag1−/− mice similarly prohibited the infiltration of neutrophils and eosinophils to the airways in papain-induced lung inflammation (Figures 5G–5H). Therefore, we conclude endogenous IL-17 plays a pathogenic role in lung inflammation by promoting recruitment of inflammatory cells to the airways and enhancing mucus production by lung epithelial cells.

Figure 5. IL-33-driven IL-17 production plays a pathogenic role in lung inflammation.

Lung inflammation was induced in Rag1−/− mice by IL-33 or papain. Mice were injected with anti-IL-17 antibody or control IgG during induction of lung inflammation. BALF cells were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A–C and G–H) Expression of CD11b, Ly6G and Siglec-F in BALF cells gated on CD45+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B and G) Percentages of BALF neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) and eosinophils (CD11b+SiglecF+) gated on CD45+ cells from indicated groups were shown. (C and H) Cell numbers of BALF neutrophils and eosinophils were shown. (D) Paraffin-embedded lung sections from indicated groups were stained with periodic acid-schiff (PAS). Magnifications are 4× and 20× respectively. Black squares indicated bronchi/bronchioles structures. Red squares indicated PAS+ bronchi/bronchioles structures. (E) Average percentages of PAS+ area in individually analyzed bronchioles/bronchi from indicated groups were shown. (F) Percentages of PAS+ bronchioles/bronchi among all bronchioles/bronchi per section from indicated groups were shown. (B, C, E–H) Data are means±SEM.

Although ILC2s are locally the dominant cell population that secretes IL-17 in IL-33-induced lung inflammation, it is possible that systemic IL-17 derived from ILC3s and neutrophils play a role in the disease 49. Therefore, we induced disease and neutralized IL-17 in Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/gfp mice which are deficient for ILC3 and neutrophil-derived IL-17 49, 50. We found percentage and cell number of neutrophils and eosinophils in the BALF were comparable between Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/gfp mice compared to littermate Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/+ mice in IL-33-induced lung inflammation, suggesting RORγt is less likely to be a pathogenic factor in IL-33-induced lung inflammation (Figures S5A–S5C). Furthermore, depletion of IL-17 was similarly effective in ameliorating the disease in Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/gfp mice indicated by reduced percentage and cell number of neutrophils in BALF, although percentage and cell number of BALF eosinophils was not affected (Figures S5A–S5C). The above data indicate IL-33-induced IL-17 exacerbates lung inflammation independently of RORγt, implying the critical role of ILC2-derived IL-17 in the disease.

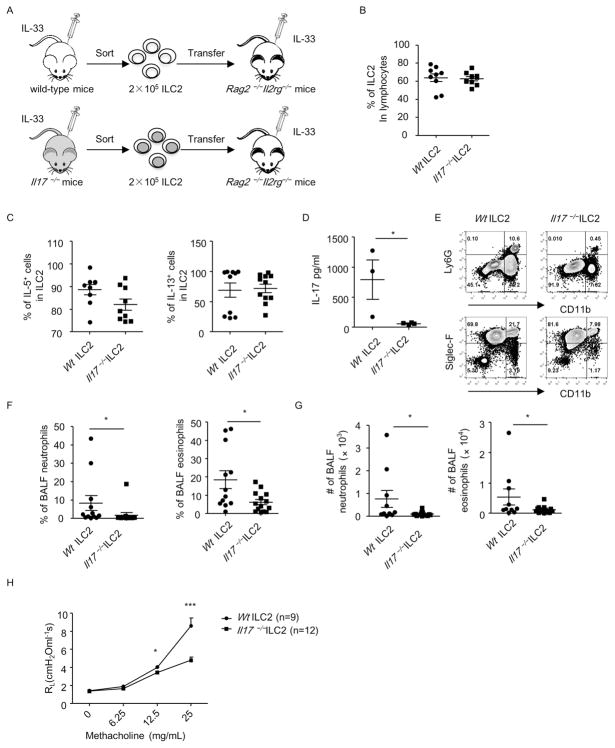

To further elaborate the pathogenic role of ILC217, we adoptively transferred IL-33-expanded ILC2s purified from IL-17-deficient mice or wild-type mice to Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice, which were lack of ILCs. We then induced lung inflammation in Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice by injecting IL-33 (Figure 6A). ILC2s from Il17−/− mice and wild-type mice expanded equally in Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice after IL-33 treatment (Figure 6B). Besides, Il17−/− ILC2s had no defective IL-5 or IL-13 production compared to wild-type mice (Figure 6C). And lymphocytes isolated from IL-33-treated Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice receiving Il17−/− ILC2s had barely detectable IL-17 production compared to mice receiving wild-type ILC2s (Figure 6D), further indicating ILC2s being the major source for IL-17 in this disease. Consistently, we observed significant reduction in percentages and total cell numbers of both neutrophils and eosinophils in the BALF of Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− − mice receiving Il17−/− ILC2s compared to mice transferred with wild-type ILC2s (Figures 6E–6G). The above data suggest Il17−/− ILC2s are less potent in recruiting inflammatory cells to the airways. Strikingly, in lung inflammation induced with IL-33 together with intranasal administration of papain, airway hyperresponsiveness was significantly lower in Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− − mice transferred with Il17−/− ILC2s than wild-type ILC2s (Figure 6H). This supports the notion that ILC217s are highly pathogenic in lung inflammation.

Figure 6. Il17−/− ILC2s had reduced function in recruiting leukocytes to the airways in IL-33-induced lung inflammation in Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice.

(A) The protocol of ILC2 transfer and induction of lung inflammation. (B–D) Lung lymphocytes were isolated from Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice. The expression of lineage markers, GATA3, IL-5, IL-13 and IL-17 were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Percentages of ILC2 (Lin− GATA3+) gated on live lymphocytes were shown. (C) Percentages of IL-5+ and IL-13+ cells in ILC2 (Lin− GATA3+) were shown. (D) Cells were cultured in medium for 48h. The level of IL-17 in the supernatants collected was analyzed by ELISA. (E–G) BALF cells were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) The expression of CD11b, Ly6G and Siglec-F gated on CD45+ leukocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) Percentages of BALF neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) and eosinophils (CD11b+SiglecF+) gated on CD45+ cells were shown. (G) Cell numbers of BALF neutrophils and eosinophils were shown. (B, C, D, F and G) Data are means±SEM. (H) RL (Lung resistance) of indicated groups was measured and shown. “N” indicates numbers of mice used in each group. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

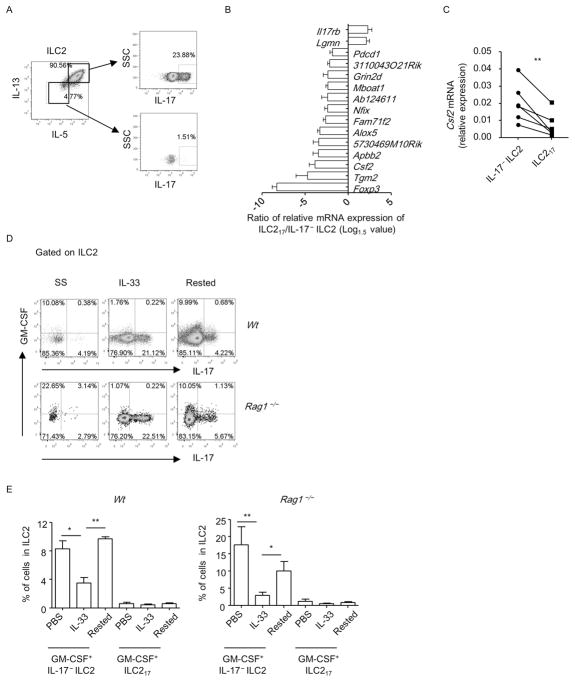

ILC217s concomitantly express IL-5 and IL-13 but few GM-CSF

ILC217s concomitantly expressed IL-5 and IL-13 (Figure 7A). Thus, the ILC217s phenotypically mirror the previously described IL-17+Th2 cells, which are IL-5+IL-13+IL-17+ cells.

Figure 7. ILC217s concomitantly express IL-5 and IL-13 but express few GM-CSF.

(A) Lung lymphocytes were isolated from wild-type mice treated with IL-33. (D and E) Lung lymphocytes were isolated from wild-type and Rag1−/− mice at the steady-state (SS), after treated with IL-33 for 4 days(IL-33) or the “rested” state (Rested). (A, D and E) The expression of IL-5, IL-13, GM-CSF and IL-17 gated on ILC2 (Lin− GATA3+) was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Genes with differential expression from ILC217 (Lin−ST2+GFP+) and IL-17− ILC2 (Lin−ST2+GFP−) with more than 1.5 folds in all 4 biological repeats were shown. Ratio of gene expression level of ILC217/IL-17− ILC2 was calculated and the Log1.5 value of the ratio was shown. (C) mRNA expression of GM-CSF was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Each line connected one pair of ILC217 and IL-17− ILC2 from one biological repeat. Statistical analysis was performed using paired Student’s t test. (E) Percentages of GM-CSF+ILC217 (upper right quadrant in D) and GM-CSF+IL17− ILC2 (upper left quadrant in D) in ILC2 from indicated groups were shown. Data are means+SEM. (A to E) Data are representative of two independent experiments.

We further compared the expression of previously characterized 106 ILC2 signature genes in lung ILC217s (Lin−ST2+GFP+) and IL-17−ILC2s (Lin−ST2+GFP−) using real-time RT-PCR by taking the advantage of IL-17-GFP reporter mouse (Table S1) 51. Although the majority of ILC2 signature genes were expressed at similar levels between ILC217 and IL-17− ILC2, including ST2, GATA3 and IL-13 (Figure S6A), 15 genes were found to be differentially expressed by ILC217 than IL-17− ILC2 for more than 1.5 fold (Figure 7B and Table S2). Though IL-17RB was expressed at a higher level in IL-17+ILC2s compared to IL-17− ILC2s, blockade of IL-25 with neutralizing antibody or genetic ablation of IL-25 in mice didn’t impair the induction of ILC217s (Figures 1G, S6B–S6E). This suggests IL-33 induces ILC217s through an IL-25-independent mechanism. Notably, the mRNA expression of GM-CSF was significantly lower in ILC217s than IL-17− ILC2s (Figures 7B and 7C). Since GM-CSF production by ILC2 has been well established and GM-CSF plays an essential role in lung inflammation 11, 52, 53, we analyzed the expression of GM-CSF at protein level in ILC217s by flow cytometry (Figure 7D). Surprisingly, in the lung of IL-33-treated wild-type or Rag1−/− mice, both ILC217s and IL-17− ILC2s expressed limited amount of GM-CSF (Figures 7D and 7E). Slightly more GM-CSF was derived from IL-17− ILC2s compared with ILC217s, consistent with lower level of Csf2 mRNA in ILC217s (Figure 7D). Intriguingly, we found GM-CSF expression in naïve and “rested” ILC2s (as described in Figure S4), predominantly by IL-17− ILC2s, was significantly higher than the expression in IL-33-challenged ILC2s (Figures 7D and 7E). Therefore, IL-33 treatment results in different kinetics of GM-CSF and IL-17 production by ILC2s.

Discussion

IL-17 has been known to play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of asthma 30. Increased level of IL-17 in lungs of asthmatic patients has been associated with the severity and heterogeneous forms of the diseases 32, 54. Previous study has shown memory/effector IL-17+Th2 cells are highly pathogenic in asthma than classical Th2 and Th17 cells in terms of recruiting leukocytes infiltration to the airways and promoting mucin production by lung epithelial cells 33. In this study, we have identified papain or IL-33-induced ST2+ILC2s, subset of the ILCs, to be a previously unappreciated source for IL-17. We name this cell population as ILC217. ILC217s concomitantly produce IL-5 and IL-13, making them phenotypically mirroring the memory/effector IL-17+Th2 cells. Neutralization of IL-17 in IL-33-induced lung inflammation ameliorated the disease, and genetic deletion of IL-17 in ILC2s reduced the pathogenicity of ILC2s to recruit inflammatory cells to the BALF in IL-33-induced lung inflammation, confirming the detrimental role of ILC217s in the disease. Our data have for the first time revealed ILC217 to be a highly pathogenic population in lung inflammation.

Previous report has shown that ST2+nILC2s (natural ILC2) express few IL-17 under the steady-state, while iILC2s (inflammatory ILC2s) driven by IL-25 can produce high amount of IL-17 21. Similar to IL-17+Th2 cells, iILC2s co-express GATA3 and RORγt, implying the production of IL-17 by IL-17+Th2 cells and iILC2s is supported by RORγt 21. In contrast, ILC217s didn’t express RORγt and their production of IL-17 was independent of RORγt. Consistently, the severity of IL-33-induced lung inflammation was comparable in RORγt-deficient mice compared to control mice, suggesting RORγt was dispensable for the pathogenicity of ILC217s.

Ahr has been shown to regulate the expression of Th17 cytokines in various immune cells 40, 43, 55. We found Ahr-deficient mice had defective induction of ILC217s compared to littermate control mice, with no defect of expansion of ILC2 by IL-33 or production of type 2 cytokines. In vitro culturing of ILC2s from naïve Ahr-deficient mice with IL-33 had reduced expression of IL-17, indicating Ahr facilitates the induction of ILC217s in an “ILC2-only” system.

We have further shown the induction of IL-17 mRNA expression requires cooperative effect of IL-33 and leukotrienes, the receptor of which is highly expressed by ILC2s 27. The accumulation of IL-17 mRNA in IL-33 treated lung lymphocytes is likely due to a combinatorial effect on ILC2 by IL-33 and leukotrienes, which could be detected in the lung tissue.

The synergistic effect of IL-33 and leukotrienes in promoting type 2 cytokines has been proved in previous study 27. Here we show that leukotrienes and IL-33 work together to induce the mRNA expression of IL-17. Importantly, we found leukotriene or IL-33 alone was not potent enough to induce IL-17 expression, while the induction of IL-13 could be achieved with each one of them. Considering IL-17 is typically not a signature cytokine for ILC2s, we reasoned the induction of IL-17 expression required multiple factors. Consistently, both NFAT downstream of leukotriene signaling and NF-κB/p38/JNK downstream of IL-33 signaling were important for IL-17 expression by ILC217s. In contrast, expression of IL-13 by ILC2s was less dependent on NFAT than expression of IL-17. Therefore, when there is abundant IL-33, a further promotion of type 2 cytokine production by leukotrienes may be mild. In contrast, expression of IL-17 by ILC2s is highly sensitive to the presence of leukotrienes. This finding broadens our understanding on the pathogenicity of leukotrienes in asthma by promoting ILC217s.

The pathogenicity of ILC217s was further addressed by adoptively transferring Il17−/−ILC2s or wild-type ILC2s to Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice, which were treated with IL-33 to induce lung inflammation. In this system, the differential severity of the disease between two groups could be exclusively attributed to IL-17 production by ILC2. Strikingly, wild-type ILC2s were more pathogenic than Il17−/− ILC2s in recruiting inflammatory cells to the airways. Thus, ILC217s are highly pathogenic in IL-33 induced lung inflammation. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that ILC217s concomitantly produced IL-5 and IL-13. In parallel with the IL-17+Th2 cells, ILC217s represent the innate compartment of the highly pathogenic IL-5+IL-13+IL-17+ cells. It remains to be explored whether there is cooperation between ILC217s and IL-17+Th2 cells to exacerbate antigen-specific allergic responses.

It is intriguing that ILC217s express few GM-CSF, an ILC2 signature cytokine which plays an important role in lung inflammation 11, 52, 53. In fact, we found ILC2s produced decent level of GM-CSF under the steady-state. However, GM-CSF production in ILC2s was reduced upon IL-33 injection and recovered after withdrawing IL-33, which was opposite to the kinetics of IL-17 expression by ILC2s in response to IL-33. The above data indicate IL-33 plays an inhibitory role on GM-CSF production by ILC2s. Considering ILC2 can be maintained in vivo for a long time independently of IL-33, IL-17 and GM-CSF could in turn participate in the progression of lung inflammation after an initial challenge with IL-33. The significance of opposite effect of IL-33 on GM-CSF and IL-17 production by ILC2s needs to be further investigated in animal models and clinical studies. Together, our finding highlights the pathogenicity of ILC217s in lung inflammation. Elimination or functional blockade of ILC217s may be a promising strategy for the treatment of allergic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 Gating strategy for characterization of IL-33-induced IL-17+ILC2s

Wildtype mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days and lung lymphocytes were isolated. Histogram of Thy1.2, CD127, Sca-1, CD25, KLRG1 and PD-1 expression gated on Lin−(CD3, B220, CD5, Gr-1)Live/dead stain−GATA3+IL-17+ cells were overlaid with the expression of above markers in Lin−Live/dead stain−GATA3− cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure S2 IL-33 induces IL-17+ILC2s in the large intestine of Rag1−/− mouse

Wildtype (A-E) or Rag1−/−(F) mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days. Lymphocytes from BM (bone marrow), MLN (mesenteric lymph nodes) and LI (large intestinal lamina propria) were isolated for analysis. (A) The expression of lineage markers and IL-17 gated on live cells from indicated organs was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Percentages of IL-17 gated on Lin− cells from indicated organs were shown. (C and D) The expression of GATA3, ST2 and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells from indicated organs was analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of IL-17+ cells in Lin−GATA3+ (ILC2) from wildtype (E) or Rag1−/− (F) mice were shown. (B, E and F) Data are means±SEM. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure S3 Lung inflammation promotes IL-17 production from ST2+RORγt− ILC2s

Lung inflammation was induced in Rag1−/− mice with IL-33 (A to D) or in wild-type mice with papain (E and F). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A) The expression of ST2 and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells from indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) The percentages of ST2+IL17+ cells and ST2−IL-17+ cells gated on Lin− cells were shown. (C and D) The expression of RORγt and IL-17 gated on Lin−ST2+ cells and Lin−ST2− cells from indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) The expression of ST2 and IL-17 gated on ILC2 (Lin−GATA3+) was analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) The percentages of ST2+IL17+ cells and ST2−IL-17+ cells gated on ILC2 were shown. (B and F) Data are means±SEM. (G and H) Histogram of ST2 expression in IL-17+ILC2s (Lin−GATA3+IL-17+) from indicated genotypes were shown. Lin−GATA3−non ILC2s in each group were overlaid as negative controls.

Figure S4 Sustained signal of IL-33 is required for the maintenance of ILC217s

Rag1−/− mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days (freshly challenged). In the “rested” protocol, Rag1−/− mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days and sacrificed 12 days later for analysis. In the re-challenged protocol, “rested” mice were injected with 500ng IL-33 for 2 consecutive days. Lung lymphocytes were isolated and stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4h before analyzed with flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A) The expression of IL-17 and GATA3 gated on Lin− cells from lung lymphocytes of indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Percentages of IL-17+ cells in ILC2 (Lin−GATA3+) from indicated groups were calculated and shown. Data are means±SEM.

Figure S5 Endogenous IL-17 triggered by IL-33 exacerbates lung inflammation independently of RORγt

Littermate Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/+ and Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/gfp mice were treated with IL-33 to induce lung inflammation. IgG or anti-IL-17 was injected to mice during IL-33 treatment. BALF cells were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A) The expression of CD11b, Ly6G and Siglec-F gated on CD45+ leukocytes from indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Percentages of BALF neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) and eosinophils (CD11b+SiglecF+) gated on CD45+ cells from indicated groups were shown. Data are means±SEM. (C) Cell numbers of BALF neutrophils and eosinophils from indicated groups were shown. Data are means±SEM.

Figure S6 Gene expression in ILC217s compared to IL-17−ILC2s and independency of induction of ILC217 on IL-25

(A) mRNA expression of ILC217 (Lin−ST2+GFP+) and IL-17−ILC2 (Lin−ST2+GFP−) purified from IL-33-treated IL-17-GFP reporter mice was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. mRNA expression of ST2, GATA3 and IL-13 in ILC217 and IL-17−ILC2 was shown. Each line connected one pair of ILC217 and IL-17−ILC2 from one biological repeat. Statistical analysis was performed using paired Student’s t test. (B and C) Wild-type mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days, and α-IL-25 or IgG were injected to mice on day 0 and day 2. (D and E) Il25−/− mice were treated with PBS or IL-33 for 4 consecutive days. (B-E) Lung lymphocytes were isolated. (B and D) The expression of GATA3 and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C and E) Percentages of IL-17+ cells in Lin−GATA3+ cells (ILC2s) were shown. Data are means+SEM. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Key messages.

IL-17-producing ST2+ILC2s are highly pathogenic in lung inflammation.

Ahr but not RORγt facilitates the IL-17 production from ST2+ILC2s.

IL-33 and leukotrienes synergistically induce IL-17 expression from ST2+ILC2s.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Fernandez-Salguero P and the National Cancer Institute for sharing Ahr−/− mice. We are grateful to Dr. Bing Su for providing IL-17A-GFP reporter mice. We thank Dr. Lie Wang, Dr. Linrong Lu and Dr. Hong Tang for experimental support. We thank the entire J.Q. laboratory for their help and suggestions. This study was supported by grants 2015CB943400 and 2014CB943300 from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, grant XDB19000000 from the “Strategic priority research program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences”, grants 91542102 and 31570887 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and China's Youth 1000-Talent Program to J. Q.; grant 16ZR1449900 from the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai and grant 2017323 from the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences to Y. J. The work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK105562 and R01AI132391 to L. Z.), and by a Cancer Research Institute Investigator Award (LZ). Liang Zhou is a Pew Scholar in Biomedical Sciences, supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts, and an Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease, supported by Burroughs Wellcome Fund. The work was also supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 81571533 (to L.S.) and China’s Youth 1000-Talent Program (to L.S.).

Abbreviations

- ILCs

innate lymphoid cells

- ILC2s

group 2 innate lymphoid cells

- iILC2s

inflammatory group 2 innate lymphoid cells

- nILC2s

natural group 2 innate lymphoid cells

- RORγt

retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan receptor-γt

- CysLTs

cysteinyl leukotrienes

- Cysltr1

cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluids

- Ahr

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- MLNs

mesenteric lymph nodes

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- PKC

protein kinase C

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- PAS

periodic acid-schiff

- RL

lung resistance

- LPLs

lamina propria lymphocytes

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3546–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI36130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holgate ST, Polosa R. Treatment strategies for allergy and asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:218–30. doi: 10.1038/nri2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locksley RM. Asthma and allergic inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:777–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson DS, Hamid Q, Ying S, Tsicopoulos A, Barkans J, Bentley AM, et al. Predominant TH2-like bronchoalveolar T–lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:298–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menzies-Gow AN, Flood-Page PT, Robinson DS, Kay AB. Effect of inhaled interleukin-5 on eosinophil progenitors in the bronchi and bone marrow of asthmatic and non-asthmatic volunteers. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1023–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. The eosinophil. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:147–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi Y, Suda T, Suda J, Eguchi M, Miura Y, Harada N, et al. Purified interleukin 5 supports the terminal differentiation and proliferation of murine eosinophilic precursors. J Exp Med. 1988;167:43–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wills-Karp M. Interleukin-13 in asthma pathogenesis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004;4:123–31. doi: 10.1007/s11882-004-0057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Muhsen S, Johnson JR, Hamid Q. Remodeling in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:451–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.047. quiz 63–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:225–35. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–70. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, et al. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, et al. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:191–8. e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Kephart GM, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL-33-responsive lineage- CD25+ CD44(hi) lymphoid cells mediate innate type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation in the lungs. J Immunol. 2012;188:1503–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein Wolterink RG, Kleinjan A, van Nimwegen M, Bergen I, de Bruijn M, Levani Y, et al. Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine models of allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1106–16. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Dyken SJ, Mohapatra A, Nussbaum JC, Molofsky AB, Thornton EE, Ziegler SF, et al. Chitin activates parallel immune modules that direct distinct inflammatory responses via innate lymphoid type 2 and gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 2014;40:414–24. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roediger B, Kyle R, Yip KH, Sumaria N, Guy TV, Kim BS, et al. Cutaneous immunosurveillance and regulation of inflammation by group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:564–73. doi: 10.1038/ni.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim BS, Siracusa MC, Saenz SA, Noti M, Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, et al. TSLP elicits IL-33-independent innate lymphoid cell responses to promote skin inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:170ra16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vonarbourg C, Diefenbach A. Multifaceted roles of interleukin-7 signaling for the development and function of innate lymphoid cells. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Guo L, Qiu J, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Siebenlist U, et al. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential 'inflammatory' type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:161–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y, Paul WE. Inflammatory group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Int Immunol. 2016;28:23–8. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang K, Xu X, Pasha MA, Siebel CW, Costello A, Haczku A, et al. Cutting Edge: Notch Signaling Promotes the Plasticity of Group-2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. J Immunol. 2017;198:1798–803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuelsson B. Leukotrienes: mediators of immediate hypersensitivity reactions and inflammation. Science. 1983;220:568–75. doi: 10.1126/science.6301011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–5. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drazen JM, Israel E, O'Byrne PM. Treatment of asthma with drugs modifying the leukotriene pathway. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:197–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Moltke J, O'Leary CE, Barrett NA, Kanaoka Y, Austen KF, Locksley RM. Leukotrienes provide an NFAT-dependent signal that synergizes with IL–33 to activate ILC2s. J Exp Med. 2017;214:27–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doherty TA, Khorram N, Lund S, Mehta AK, Croft M, Broide DH. Lung type 2 innate lymphoid cells express cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1, which regulates TH2 cytokine production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lund SJ, Portillo A, Cavagnero K, Baum RE, Naji LH, Badrani JH, et al. Leukotriene C4 Potentiates IL-33-Induced Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Activation and Lung Inflammation. J Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolls JK, Kanaly ST, Ramsay AJ. Interleukin-17: an emerging role in lung inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:9–11. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0255PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molet S, Hamid Q, Davoine F, Nutku E, Taha R, Page N, et al. IL-17 is increased in asthmatic airways and induces human bronchial fibroblasts to produce cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:430–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakir J, Shannon J, Molet S, Fukakusa M, Elias J, Laviolette M, et al. Airway remodeling-associated mediators in moderate to severe asthma: effect of steroids on TGF-beta, IL-11, IL-17, and type I and type III collagen expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1293–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang YH, Voo KS, Liu B, Chen CY, Uygungil B, Spoede W, et al. A novel subset of CD4(+) T(H)2 memory/effector cells that produce inflammatory IL-17 cytokine and promote the exacerbation of chronic allergic asthma. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2479–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizutani N, Nabe T, Yoshino S. IL-17A promotes the exacerbation of IL-33-induced airway hyperresponsiveness by enhancing neutrophilic inflammation via CXCR2 signaling in mice. J Immunol. 2014;192:1372–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halim TY, MacLaren A, Romanish MT, Gold MJ, McNagny KM, Takei F. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:463–74. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor S, Huang Y, Mallett G, Stathopoulou C, Felizardo TC, Sun MA, et al. PD-1 regulates KLRG1(+) group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J Exp Med. 2017;214:1663–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanai T, Mikami Y, Sujino T, Hisamatsu T, Hibi T. RORgammat-dependent IL-17A-producing cells in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:240–7. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eberl G. RORgammat, a multitask nuclear receptor at mucosal surfaces. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:27–34. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature. 2008;453:106–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura A, Naka T, Nohara K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kishimoto T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates Stat1 activation and participates in the development of Th17 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9721–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804231105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui G, Qin X, Wu L, Zhang Y, Sheng X, Yu Q, et al. Liver X receptor (LXR) mediates negative regulation of mouse and human Th17 differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:658–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI42974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu J, Heller JJ, Guo X, Chen ZM, Fish K, Fu YX, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates gut immunity through modulation of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;36:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin MU. Special aspects of interleukin-33 and the IL-33 receptor complex. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez-Gonzalez I, Matha L, Steer CA, Ghaedi M, Poon GF, Takei F. Allergen-Experienced Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Acquire Memory-like Properties and Enhance Allergic Lung Inflammation. Immunity. 2016;45:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peres CM, Aronoff DM, Serezani CH, Flamand N, Faccioli LH, Peters-Golden M. Specific leukotriene receptors couple to distinct G proteins to effect stimulation of alveolar macrophage host defense functions. J Immunol. 2007;179:5454–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crabtree GR, Schreiber SL. SnapShot: Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Cell. 2009;138:210, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor PR, Roy S, Leal SM, Jr, Sun Y, Howell SJ, Cobb BA, et al. Activation of neutrophils by autocrine IL-17A-IL-17RC interactions during fungal infection is regulated by IL-6, IL-23, RORgammat and dectin-2. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:143–51. doi: 10.1038/ni.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eberl G, Marmon S, Sunshine MJ, Rennert PD, Choi Y, Littman DR. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinette ML, Fuchs A, Cortez VS, Lee JS, Wang Y, Durum SK, et al. Transcriptional programs define molecular characteristics of innate lymphoid cell classes and subsets. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:306–17. doi: 10.1038/ni.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mjosberg J, Bernink J, Golebski K, Karrich JJ, Peters CP, Blom B, et al. The transcription factor GATA3 is essential for the function of human type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;37:649–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohta K, Yamashita N, Tajima M, Miyasaka T, Nakano J, Nakajima M, et al. Diesel exhaust particulate induces airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model: essential role of GM-CSF. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:1024–30. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson GP. Endotyping asthma: new insights into key pathogenic mechanisms in a complex, heterogeneous disease. Lancet. 2008;372:1107–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61452-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin B, Hirota K, Cua DJ, Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity. 2009;31:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song X, Gao H, Lin Y, Yao Y, Zhu S, Wang J, et al. Alterations in the microbiota drive interleukin-17C production from intestinal epithelial cells to promote tumorigenesis. Immunity. 2014;40:140–52. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez-Salguero P, Pineau T, Hilbert DM, McPhail T, Lee SS, Kimura S, et al. Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science. 1995;268:722–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7732381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Esplugues E, Huber S, Gagliani N, Hauser AE, Town T, Wan YY, et al. Control of TH17 cells occurs in the small intestine. Nature. 2011;475:514–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiu J, Guo X, Chen ZM, He L, Sonnenberg GF, Artis D, et al. Group 3 innate lymphoid cells inhibit T-cell-mediated intestinal inflammation through aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling and regulation of microflora. Immunity. 2013;39:386–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim HY, Chang YJ, Chuang YT, Lee HH, Kasahara DI, Martin T, et al. T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 deficiency eliminates airway hyperreactivity triggered by the recognition of airway cell death. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:414–25. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Gating strategy for characterization of IL-33-induced IL-17+ILC2s

Wildtype mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days and lung lymphocytes were isolated. Histogram of Thy1.2, CD127, Sca-1, CD25, KLRG1 and PD-1 expression gated on Lin−(CD3, B220, CD5, Gr-1)Live/dead stain−GATA3+IL-17+ cells were overlaid with the expression of above markers in Lin−Live/dead stain−GATA3− cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure S2 IL-33 induces IL-17+ILC2s in the large intestine of Rag1−/− mouse

Wildtype (A-E) or Rag1−/−(F) mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days. Lymphocytes from BM (bone marrow), MLN (mesenteric lymph nodes) and LI (large intestinal lamina propria) were isolated for analysis. (A) The expression of lineage markers and IL-17 gated on live cells from indicated organs was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Percentages of IL-17 gated on Lin− cells from indicated organs were shown. (C and D) The expression of GATA3, ST2 and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells from indicated organs was analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of IL-17+ cells in Lin−GATA3+ (ILC2) from wildtype (E) or Rag1−/− (F) mice were shown. (B, E and F) Data are means±SEM. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure S3 Lung inflammation promotes IL-17 production from ST2+RORγt− ILC2s

Lung inflammation was induced in Rag1−/− mice with IL-33 (A to D) or in wild-type mice with papain (E and F). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A) The expression of ST2 and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells from indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) The percentages of ST2+IL17+ cells and ST2−IL-17+ cells gated on Lin− cells were shown. (C and D) The expression of RORγt and IL-17 gated on Lin−ST2+ cells and Lin−ST2− cells from indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) The expression of ST2 and IL-17 gated on ILC2 (Lin−GATA3+) was analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) The percentages of ST2+IL17+ cells and ST2−IL-17+ cells gated on ILC2 were shown. (B and F) Data are means±SEM. (G and H) Histogram of ST2 expression in IL-17+ILC2s (Lin−GATA3+IL-17+) from indicated genotypes were shown. Lin−GATA3−non ILC2s in each group were overlaid as negative controls.

Figure S4 Sustained signal of IL-33 is required for the maintenance of ILC217s

Rag1−/− mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days (freshly challenged). In the “rested” protocol, Rag1−/− mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days and sacrificed 12 days later for analysis. In the re-challenged protocol, “rested” mice were injected with 500ng IL-33 for 2 consecutive days. Lung lymphocytes were isolated and stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4h before analyzed with flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A) The expression of IL-17 and GATA3 gated on Lin− cells from lung lymphocytes of indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Percentages of IL-17+ cells in ILC2 (Lin−GATA3+) from indicated groups were calculated and shown. Data are means±SEM.

Figure S5 Endogenous IL-17 triggered by IL-33 exacerbates lung inflammation independently of RORγt

Littermate Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/+ and Rag1−/−Rorcgfp/gfp mice were treated with IL-33 to induce lung inflammation. IgG or anti-IL-17 was injected to mice during IL-33 treatment. BALF cells were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (A) The expression of CD11b, Ly6G and Siglec-F gated on CD45+ leukocytes from indicated groups was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Percentages of BALF neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) and eosinophils (CD11b+SiglecF+) gated on CD45+ cells from indicated groups were shown. Data are means±SEM. (C) Cell numbers of BALF neutrophils and eosinophils from indicated groups were shown. Data are means±SEM.

Figure S6 Gene expression in ILC217s compared to IL-17−ILC2s and independency of induction of ILC217 on IL-25

(A) mRNA expression of ILC217 (Lin−ST2+GFP+) and IL-17−ILC2 (Lin−ST2+GFP−) purified from IL-33-treated IL-17-GFP reporter mice was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. mRNA expression of ST2, GATA3 and IL-13 in ILC217 and IL-17−ILC2 was shown. Each line connected one pair of ILC217 and IL-17−ILC2 from one biological repeat. Statistical analysis was performed using paired Student’s t test. (B and C) Wild-type mice were treated with IL-33 for 4 consecutive days, and α-IL-25 or IgG were injected to mice on day 0 and day 2. (D and E) Il25−/− mice were treated with PBS or IL-33 for 4 consecutive days. (B-E) Lung lymphocytes were isolated. (B and D) The expression of GATA3 and IL-17 gated on Lin− cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C and E) Percentages of IL-17+ cells in Lin−GATA3+ cells (ILC2s) were shown. Data are means+SEM. Data are representative of two independent experiments.